Abstract

Background

Minority groups are affected by significant disparities in kidney transplantation (KT) in Veterans Affairs (VA) and non-VA transplant centers. But, prior VA studies have been limited to retrospective, secondary database analyses that focused on multiple stages of the KT process simultaneously. Our goal was to determine whether disparities during the evaluation period for KT exist in the VA as has been found in non-VA settings.

Methods

We conducted a multi-center longitudinal cohort study of 602 patients undergoing initial evaluation for KT at 4 National VA KT Centers. Participants completed a telephone interview to determine whether, after controlling for medical factors, differences in time to acceptance for transplant were explained by patients' demographic, cultural, psychosocial, or transplant knowledge factors.

Results

There were no significant racial disparities in the time to acceptance for KT [Log-Rank χ2 =1.04; p=0.594]. Younger age (HR 0.98; 95% CI 0.97–0.99), fewer comorbidities (HR 0.89; 95% CI 0.84–0.95), being married (HR 0.81; 95% CI 0.66–0.99), having private and public insurance (HR 1.29; 95% CI 1.03–1.51), and moderate or greater levels of depression (HR 1.87; 95% CI 1.03–3.29) predicted a shorter time to acceptance. The influence of preference for type of KT (deceased or living donor) and transplant center location on days to acceptance varied over time.

Conclusions

Our results indicate that the VA National Transplant System did not exhibit the racial disparities in evaluation for KT as have been found in non-VA transplant centers.

Introduction

With an incidence of 357 cases per million population each year,1 End-Stage Kidney Disease (ESKD) results in significant morbidity and mortality in the United States. It disproportionately affects racial/ethnic minority populations, with an incidence rate of 3.4 and 1.5 times greater in the African-American (AA) and Hispanic populations, respectively, compared to nonHispanic Whites.1 However, minority populations are substantially less likely to undergo kidney transplantation (KT), the optimal treatment for ESKD.2,3 Prior research in Veterans and nonVeterans demonstrated that AA and other minority (OM) groups experience longer time periods between dialysis initiation and waitlisting for KT4,5 and longer time to complete the medical evaluation for KT6,7 among other disparities in KT.2,3,8–10 These disparities persist despite controlling for medical factors such as the etiology of ESKD, comorbidities, and dialysis type/duration.7,11,12 These findings suggest that nonmedical factors, such as demographics,13,14 culturally related factors,15,16 transplant education,17–19 and psychosocial characteristics20,21 may contribute to disparities.

The existing literature examining the influence of nonmedical factors on disparities has limitations. The majority of studies are retrospective, which limits their ability to assess whether nonmedical factors predict (rather than are simply associated with) the identified racial disparities. Many of these studies focus on assessing the influence of 1 or a few nonmedical factors (eg health literacy22, geographic factors14) on transplantation, rather than concurrently assessing several factors. Examining several factors simultaneously allows the testing of multiple hypotheses, while controlling for the influence of the other assessed factors.

Data regarding the impact that nonmedical factors have on racial disparities experienced by patients served by the United States (US) Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) are limited to just 2 studies.3,9 Both utilized data from the US Renal Data System database, which contains only limited information on nonmedical factors. Because these studies assessed disparities across multiple stages of the KT process simultaneously (ie referral, evaluation, waitlisting), they have a limited ability to identify the processes which contribute most to the observed disparities. Determining the underlying factors which predict disparities at a specific stage is crucial to inform potential interventions to address those disparities. We hypothesized that the transplant evaluation stage is particularly important because the target population consists of patients who have overcome barriers to transplantation investigated by others (eg, specialty care, referral for transplant), yet disparities persist.

Thus, the focus of our study was to examine VA patients of diverse racial/ethnic backgrounds with ESKD who were undergoing the evaluation process for KT. Specifically, we examined whether VA ESKD patients undergoing KT evaluation varied: (1) across demographic characteristics, culturally-related factors, psychosocial characteristics, and transplant knowledge; and, (2) in the likelihood of acceptance for KT when controlling for medical and nonmedical factors.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

This multi-center longitudinal study was approved by the IRB at all participating VA KT Centers. Participants completed a semi-structured telephone interview 1 – 3 weeks after their first transplant clinic appointment (Time 1). The ~70 minute interview comprised questions derived from existing valid measures.6 Time 2 data collection included medical record review after participants completed the evaluation process and were accepted or rejected for KT.

Description of VA Transplant Evaluation Process

During the study period (2010–2014), there were 4 VA kidney transplant centers nationally. To obtain an initial clinic appointment at a VA KT center and be considered for a transplant, VA patients first must complete a battery of tests [a standardized “checklist” specified by the VA National Transplant Office (VANTO)] coordinated by their primary care physician or nephrologist at their home VA medical center. The referring physician collects and submits this material to VANTO, who selects a transplant center for the patient based on geographic proximity. Then, a transplant physician from the selected transplant center reviews the referral packet and determines if the patient is a candidate for further evaluation. If the patient is accepted for evaluation, the VA KT center contacts the patient for an initial clinic appointment. Although the list of tests is standardized, each VA transplant center has its own acceptance criteria.

Study Sample

Participants were recruited from 4 National VA KT Centers during their initial transplant evaluation appointment. Inclusion criteria were: (1) referral for KT; (2) no previous history of KT; and (3) age 18 or older. A total of 648 patients met these criteria and 617 were enrolled in the study (recruitment rate = 95%). Of those enrolled, 15 never completed the first interview, yielding a total sample of 602 (92% response rate). Recruited participants were evaluated for transplant between April 2010 and December 2012. Data collection continued until September 2014.

Interview Procedures and Measures

Study variables were assessed with standard measures administered by semi-structured telephone interviews and medical record review. The interviews were conducted by research interviewers at the University of Pittsburgh independent from any transplant service. All interview data were entered directly into the interview software using a computer aided telephone interview system. A brief outline of the measures is presented below and expanded detail on the predictor variables (including ranges and psychometric properties) is available in the Supplemental Digital Content available online (SDC 1).

Outcome Variables

Time to Acceptance for Transplant

The primary outcome variable, the time from evaluation at the VA KT center to the time that a patient was accepted for transplant listing, was determined by medical chart review.

Predictor Variables

Demographics

We assessed race, gender, age, marital status, education, income, insurance status, and occupation using respondents’ self-report during the first interview. Participants were classified as NonHispanic African-American (AA), NonHispanic White (WH) or other minorities (OM) for the purpose of analysis.

Medical Factors

We assessed participants’ health history including their reason for seeking KT, dialysis type, and perceived burden of kidney disease by self-report. The network of potential living donors (LDs) available for evaluation was determined by asking participants to indicate how many living relatives and friends they had aged 18–70 years, the age range of living kidney donors.23 Actual LDs were individuals who were undergoing, had already undergone, or were planning to undergo evaluation for living donation to a specific patient. Finally, we determined participants’ Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) scores via medical record review.24,25

Culturally-Related Factors

We assessed perceived discrimination with an adapted version of the Perceived Discrimination in Health Care measure.26–28 We measured perceived racism in health care with 4 items based on the work of LaViest and colleagues29,30 We assessed medical mistrust with 18 items adapted from LaVeist’s medical mistrust index.29–31 We assessed trust in physicians using the 11 item Trust in Physician Scale.32 We assessed family influence with the 16-item Bardis Familism scale.33 Religious preference was self-reported. We assessed religious objections to LDKT using a revised subscale of the Organ Donation Attitude Survey.34 We have used all of these adapted measures in our previous work.15,35

Psychosocial Characteristics

Emotional distress was measured with the anxiety and depression subscales of the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI).36 Social support was measured with a 12-item version of the Interpersonal Support Evaluation List (ISEL-12). Self-esteem was measured using the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale.37 Participants’ sense of mastery was assessed using the Sense of Mastery Scale38. Locus of control was assessed with the Multidimensional Health Locus of Control (MHLC) scales, Form C.39

Transplant Knowledge, Concerns, and Preference

Transplant knowledge was assessed with items adapted from the KT Knowledge Survey40 and the KT Questionnaire.18,19 Participants’ engagement in transplant learning activities was assessed by self-report. Participants reported the type of educational activity and the time spent on each activity. Transplant concerns were assessed using 30 items adapted from the KT Questionnaire.18,19 We assessed transplant preference by asking participants whether they preferred a LDKT or deceased donor (DDKT), and if they had a potential LD being evaluated.15

Statistical Analysis

We dichotomized some ordinal covariates (ie, education, occupation, household income, anxiety, depression, perceived racism) because they had small sample sizes for certain race groups. All variables were compared for race differences using chi-squared (or Fisher’s exact) tests for categorical variables and the Kruskal-Wallis test for continuous variables (due to nonnormal distributions). Kaplan-Meier survival curves were constructed to depict race/ethnicity differences in the time to acceptance for transplant, with censoring at the point of either rejection for transplant, death before evaluation completion, or failure to complete the evaluation before the end of the study. We performed a time-to-event analysis instead of an analysis focusing on simple completion of the evaluation (yes/no) so that we could account for censoring. This approach allows us to correctly estimate risk of outcome using all available data. Log-rank tests were used to assess the difference between these survival functions.

For the Cox proportional hazards model, covariates were examined for adequacy of the functional form and the proportional hazards assumption. Bivariate analysis was performed for potential predictors; any variable associated with the outcome at p<0.10 was then included in a multivariable Cox proportional hazards model. This procedure ensured that only the variables that had the strongest association with time to acceptance for transplant would be included in the final model, and would limit Type 1 error. These predictors were assessed for multicolinearity, and no significant concerns were identified. The proportional hazards assumption was assessed at p<0.05 using Gray’s test for each potential predictor.41,42 Because some of the predictor variables violated this assumption, we used Gray’s Cox regression model for the multivariable analyses.

Results

Race/Ethnicity Comparisons on Demographic, Medical, Cultural and Psychosocial Factors

We found that WH in our sample were older, more likely to be married, and less likely to be on dialysis (thus more likely to be preemptively evaluated) than AA and OM. AA and OM reported more experiences of discrimination, perceived racism, medical mistrust, family loyalty, and religious objection to LDKT than did WH. Further, AA and OM reported a higher external locus of control, and lower transplant knowledge than did WH (p-value range ≤0.001 to <0.05; see Table 1). Although AA and OM had larger networks of potential living donors than WH, there were no differences in the proportion of patients with an actual living donor. Further, there were no differences in the degree of concern about undergoing KT, in the preferred type of transplant (living, deceased, no preference), or in the willingness to accept a volunteer living donor. Finally, AA were more willing to ask others to be a living donor than were WH or OM.

Table 1.

Characteristics of kidney transplant candidates by race/ethnicity

| Total (n=602) |

NonHispanic African American (n=199) |

NonHispanic White (n=271) |

Other Minorities (n=132) |

Test Statistic‡ |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic Characteristics | ||||||

| Gender (male) - % (N) | 96.7 (582) | 94.5 (188) | 97.8 (265) | 97.7 (129) | χ2 =4.50 | 0.11 |

| Age – m (sd)a | 59.6 (9.1) | 57.4 (9.6) | 61.3 (8.5) | 59.2 (9.1) | K=22.56 | 0.00 |

| Education (< high school) - % (N) | 31.9 (192) | 30.2 (60) | 35.8 (97) | 26.5 (35) | χ2 =3.93 | 0.14 |

| Household income (< $50,000)b- % (N) | 73.2 (434) | 72.1 (142) | 71.9 (192) | 77.5 (100) | χ2 =1.58 | 0.45 |

| Insurance (public only)c- % (N) | 73.5 (442) | 73.4 (146) | 73.7 (199) | 73.5 (97) | χ2 =7.18 | 0.13 |

| Occupation (≥ skilled manual worker)d,e- % (N) | 47.0 (281) | 45.7 (90) | 46.7 (126) | 49.6 (65) | χ2 =0.51 | 0.78 |

| Marital Status (not married) - % (N) | 40.5 (244) | 44.7 (89) | 35.1 (95) | 45.5 (60) | χ2 =6.15 | 0.05 |

| Study Location - % (N) | χ2 =71.45 | 0.00 | ||||

| Site A | 20.1 (121) | 27.1 (54) | 16.2 (44) | 17.4 (23) | ||

| Site B | 19.1 (115) | 18.1 (36) | 22.1 (60) | 14.4 (19) | ||

| Site C | 35.7 (215) | 46.2 (92) | 35.1 (95) | 21.2 (28) | ||

| Site D | 25.1 (151) | 8.5 (17) | 26.6 (72) | 47.0 (62) | ||

| Medical Factors | ||||||

| Charlson Comorbidity Index – m(sd)f,g | 4.5 (1.7) | 4.4 (1.9) | 4.5 (1.7) | 4.5 (1.6) | K=0.94 | 0.63 |

| Type of Dialysis - % (N) | ||||||

| Hemodialysis** | 61.1 (368) | 66.3 (132) | 53.1 (144) | 69.7 (92) | χ2 =14.97 | 0.00 |

| Peritoneal Dialysis | 10.5 (63) | 11.6 (23) | 9.2 (25) | 11.4 (15) | χ2 =1.53 | 0.67 |

| Burden of Kidney Disease – m(sd)h | 3.6 (1.1) | 3.6 (1.1) | 3.6 (1.1) | 3.6 (1.1) | K=0.29 | 0.87 |

| Network of Potential Donors - m(sd)i | 24.3 (24.1) | 26.8 (21.3) | 20.0 (18.0) | 29.5 (35.1) | K=22.33 | 0.00 |

| Have a Living Donor at T1 (yes)j - % (N) | 41.1 (241) | 40.2 (78) | 41.9 (111) | 40.6 (52) | χ2 =0.14 | 0.93 |

| Cultural Factors | ||||||

| Experience of Discrimination (any) - %(N)k | 36.8 (221) | 59.6 (118) | 19.9 (54) | 37.4 (49) | χ2 =77.41 | 0.00 |

| Perceived Racisml - m(sd) | 2.3 (0.7) | 2.6 (0.7) | 2.2 (0.7) | 2.4 (0.8) | K=46.86 | 0.00 |

| Medical Mistrustm - m(sd) | 2.5 (0.5) | 2.6 (0.5) | 2.4 (0.5) | 2.5 (0.5) | K=23.68 | 0.00 |

| Trust in Physiciann - m(sd) | 2.3 (0.5) | 2.3 (0.5) | 2.2 (0.4) | 2.3 (0.5) | K=7.56 | 0.02 |

| Family Loyaltyo - m(sd) | 50.9 (9.1) | 51.6 (9.6) | 49.4 (7.8) | 52.8 (10.0) | K=17.87 | 0.00 |

| Religious Objectionp,q - m(sd) | 2.0 (0.5) | 2.0 (0.5) | 1.9 (0.5) | 2.0 (0.5) | K=6.40 | 0.04 |

| Psychosocial Characteristics - m(sd) | ||||||

| Social supportr | 40.7 (9.2) | 41.1 (8.7) | 40.2 (9.6) | 40.9 (9.1) | K=0.89 | 0.64 |

| Self-esteems | 3.1 (0.6) | 3.1 (0.6) | 3.0 (0.6) | 3.1 (0.6) | K=4.63 | 0.10 |

| Masteryt | 3.0 (0.5) | 3.0 (0.5) | 2.9 (0.5) | 3.0 (0.6) | K=4.08 | 0.13 |

| Locus of Control | ||||||

| Internalj,u | 4.2 (1.1) | 4.2 (1.1) | 4.1(1.0) | 4.3 (1.1) | K=2.46 | 0.29 |

| Externalc,v | 3.5 (0.8) | 3.6 (0.8) | 3.4 (0.8) | 3.5 (0.8) | K=11.37 | 0.00 |

| Anxiety (≥ moderate) - % (N) | 1.5 (9) | 1.0 (2) | 1.5 (4) | 2.3 (3) | χ2 =0.87 | 0.57 |

| Depression (≥ moderate) - % (N) | 2.8 (17) | 1.5 (3) | 4.1 (11) | 2.3 (3) | χ2 =2.91 | 0.24 |

| Transplant Knowledge and Education - m(sd) | ||||||

| Transplant Knowledgew | 21.7 (2.5) | 21.4 (2.7) | 22.2 (2.2) | 21.1(2.6) | K=20.32 | 0.00 |

| Number of learning activitiesx | 4.5 (1.6) | 4.4 (1.7) | 4.6 (1.5) | 4.7 (1.5) | K=1.22 | 0.54 |

| Total hours of learning activitiesk,y | 23.2 (24.9) | 23.6 (26.9) | 21.9 (22.4) | 25.1 (26.9) | K=1.77 | 0.41 |

| Transplant Concernsz - m(sd) | 10.6 (4.7) | 10.3 (4.5) | 10.3 (4.5) | 11.4 (5.3) | K=3.78 | 0.15 |

| Donor Preference - % (N) | χ2 =4.14 | 0.39 | ||||

| Deceased donor | 11.6 (70) | 8.0 (16) | 14.0 (38) | 12.1(16) | ||

| Living donor | 74.8 (450) | 78.4 (156) | 72.3 (196) | 74.2 (98) | ||

| No preference | 13.6 (82) | 13.6 (27) | 13.7 (37) | 13.6 (18) | ||

| Living Donor Recruitment- % (N) | ||||||

| Willing to accept volunteer (yes)b | 89.0 (528) | 90.3 (177) | 90.7 (243) | 83.7 (108) | χ2 =4.79 | 0.09 |

| Willing to ask for donation (yes)zz | 58.0 (342) | 68.0 (132) | 52.6 (140) | 53.8 (70) | χ2 =12.09 | 0.00 |

Notes:

chi-squared (χ2) test was performed for categorical variables and Kruskal-Wallis (K) was performed for continuous variables.

Range = 27.0–87.0;

Based on n=593 due to missing data on this variable;

Based on n=601 due to missing data on this variable;

Based on the Hollingshead Occupational Scale;

Based on n=598 due to missing data on this variable;

Based on n=595 due to missing data on this variable;

Range = 2.0–13.0;

Range = 1.0–5.0;

Range = 2.0–214.0;

Based on n=587 due to missing data on this variable;

Based on n=600 due to missing data on this variable;

Range = 1.0–4.7);

Range = 1.0–4.1;

Range = 1.0–4.1;

Range = 16.0–76.0;

Based on n=596 due to missing data on this variable;

Range = 1.0–3.5;

Range = 11.0–48.0;

Range = 1.0–4.1;

Range = 1.0–5.3;

Range = 1.0–6.0;

Range = 1.0–5.6;

Range = 8.0–27.0;

Range = 0.0–8.0;

Range = 0.0–101.0;

Range = 0.0–25.0;

Based on n=590 due to missing data on this variable.

Race/Ethnicity Comparison of Time to Acceptance

For this analysis, 29.7% of the observations were censored. Of these, 18.1% were censored due to being rejected for transplant, 2.0% due to death before evaluation completion, and 9.6% due to not completing the evaluation before the end of the study. The censored observations did not differ by race (27.6% AA, 32.1% WH, and 28.0% OM; (Pearson χ2 =1.33; p=0.514). There was no significant association between reason for censoring and race (Fisher’s Exact Test =3.63; p=0.463).

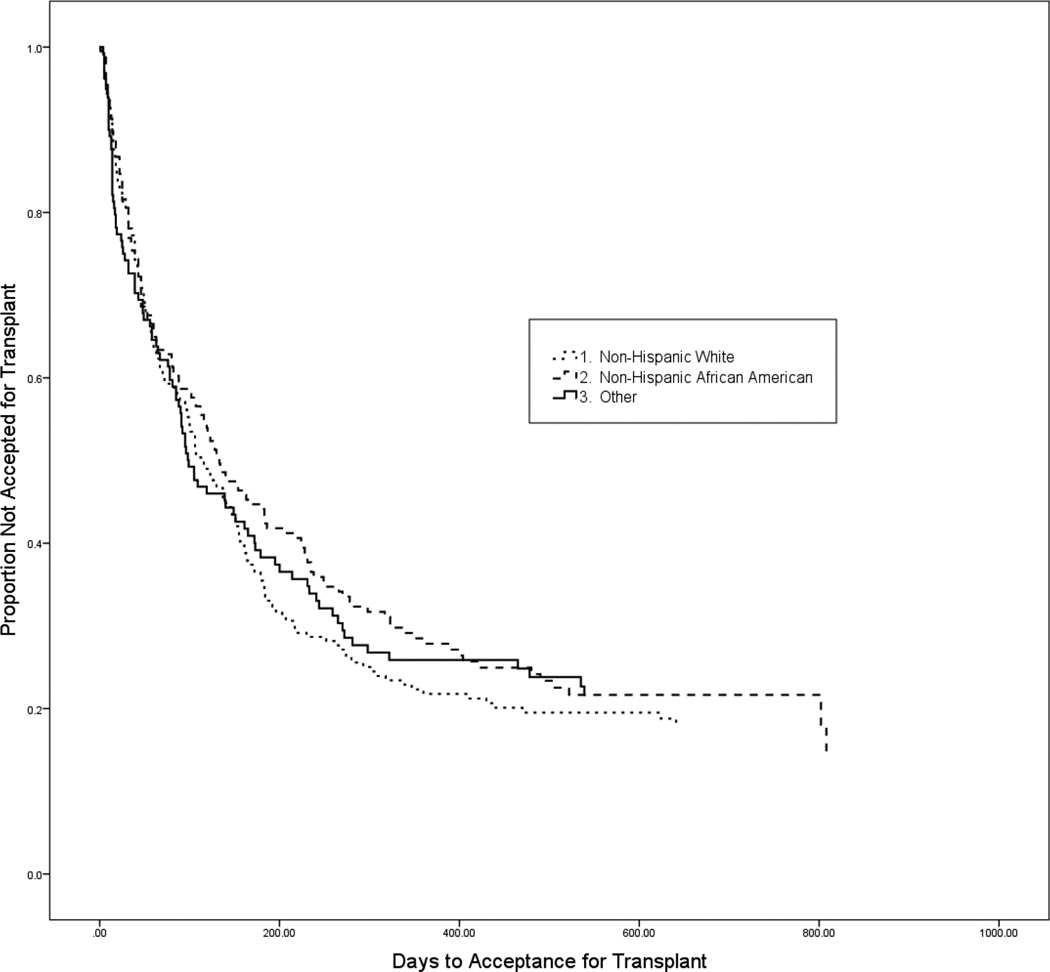

Figure 1 shows the Kaplan-Meier survival curves for the number of days until acceptance for KT by race. There were no significant race differences in the time to acceptance for a KT [Log-Rank χ2 =1.04; p=0.594; median days (IQR): AA=133(39,421), WH=116(39,301), OM=99(28,465)].

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves for comparison of time to be accepted for a kidney transplant by race (Log-Rank χ2 =1.040; p=0.594).

Predictors of Acceptance for a Kidney Transplant

We found that neither race nor many of the other assessed medical, cultural, and psychosocial factors predicted acceptance for transplant. Only younger age, less co-morbidity, having private insurance in addition to public insurance, being married, and those with moderate or greater levels of depression were associated with increased likelihood of being accepted for transplant (all p-values <0.05; see Table 2).

Table 2.

Predictors of time to be accepted for kidney transplant

| Variables | Hazard Ratio (HR)1 | 95% Confidence Interval1 |

HR min2 | HR max2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Race | ||||

| NonHispanic White | Ref. | Ref. | --- | --- |

| NonHispanic African-American | 0.89 | (0.70,1.12) | --- | --- |

| Other Minorities | 1.02 | (0.79,1.33) | --- | --- |

| Age (in years)* | 0.98 | (0.97,0.99) | --- | --- |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index* | 0.89 | (0.84,0.95) | --- | --- |

| Insurance Status | ||||

| Public only | Ref. | Ref. | --- | --- |

| Private only | 0.99 | (0.31,3.15) | --- | --- |

| Public and Private* | 1.29 | (1.03,1.61) | --- | --- |

| Marital Status | ||||

| Married | Ref. | Ref. | --- | --- |

| Not Married | 0.81 | (0.66,0.99) | --- | --- |

| Study Location* | ||||

| Site A | Ref. | Ref. | --- | --- |

| Site B | --- | --- | 0.79 | 2.49 |

| Site C | --- | --- | 0.85 | 3.14 |

| Site D | 1.39 | (1.01,1.90) | --- | --- |

| Religious Objection | 0.89 | (0.72,1.09) | --- | --- |

| Depression (≥ moderate)* | 1.87 | (1.03,3.29) | --- | --- |

| Transplant Knowledge | 1.02 | (0.98,1.07) | --- | --- |

| Donor Preference | ||||

| Deceased Donor | Ref. | Ref. | --- | --- |

| Living Donor | 0.81 | (0.60,1.10) | --- | --- |

| No Preference | --- | --- | 0.27 | 0.84 |

Notes: A hazard ratio less than 1.0 indicates decreased acceptance for kidney transplant for a given point in time. All variables included in Gray’s Cox multivariable regression model are included in this table.

Only shown for covariates which met the proportional hazards assumption.

Only shown for covariates which did not meet the proportional hazards assumption.

p<0.05

Ref. = Reference category.

Additional information (ie, plot of smoothed log(HR) function with 95% confidence bands) for the covariates not meeting the proportional hazards assumption is reflected in Supplementary Figures 1–3 (available online).

We used Gray’s multivariable Cox regression model because transplant type preference and study site violated the proportional hazards assumption. Because site was a fixed rather than a random effect, dummy coding was required. Thus, we chose Site A as our reference site, because patients at that center had both the longest median and mean time until acceptance for transplant. In comparison to Site A, participants from Site D were significantly more likely to be accepted for transplant throughout the evaluation period. Similarly, participants in Site C (compared to Site A) had a higher likelihood of acceptance almost immediately at the outset, and this increased likelihood was sustained over time. In contrast, participants at Site B (relative to Site A) were had a higher likelihood of being accepted in the first 30 days after evaluation initiation, but this effect dissipated by 90 days. Also, we found that participants with no preference for LDKT or DDKT were much less likely to be accepted early in the evaluation period, but by 90 days after the initiation of the transplant evaluation this effect dissipated (see SDC Figures 1–3).

Discussion

Our study offers the most comprehensive prospective examination to date of the impact of medical and nonmedical factors on the kidney transplant evaluation process in ESKD patients served by the VA medical system. It was conducted at all VA transplant centers, which serve all geographic regions of the US. Thus, our results are more representative of the Veteran population than other studies because we assessed almost the entire population of patients that are evaluated for KT within the VA system.

The most critical finding of our work was that there were no significant race/ethnicity differences in the likelihood of acceptance for KT in VA patients. This finding is remarkable given the known racial/ethnic disparities in other stages of the transplantation process found in VA and non-VA settings,3,7,9,15 and findings from our previous work demonstrating disparities in a mostly non-VA population.6 Although the time duration between the development of ESKD and undergoing KT may be impacted by a number of medical factors, the time that elapses during the KT evaluation process is most under the direct control of transplant centers. Thus, efforts to analyze and optimize the KT evaluation process play an important role in allowing individual programs to reduce KT disparities. This approach is in contrast to broad social, cultural, economic, psychological and systemic contributors to disparities in other aspects of ESKD and KT care, which, while vitally important, may require equally sweeping solutions. Although such interventions are possible, such as the recent OPTN change to assign waiting time based on the initiation of dialysis rather than at the time of listing for KT, they are beyond the control of any individual institution to implement and may not address all aspects of KT disparities. The credit for dialysis waiting time can only benefit those who complete the evaluation process. Thus, our approach contributes to this effort as well.

VA KT centers are successfully bringing ESKD patients through the evaluation process without race disparities at a time when non-VA transplant centers are unable to do so,7,15,43,44 and are doing so while achieving a median time to complete evaluation similar to other published rates in non-VA settings.7 This finding suggests that specific characteristics of the VA healthcare system or Veterans may play a role in mitigating disparities. VA medical care is offered free of charge to individuals who qualify, which may explain why we did not identify income as a predictor of acceptance for KT, in contrast to studies performed in other systems.4,13 The VA offers considerable support to transplant candidates including travel and lodging to attend the transplant center for the candidate and support person.45,46 Finally, unlike in non-VA settings, the process for referral and evaluation is standardized across VA transplant centers. Although our study was not designed to assess whether these specific variables affected the tendency to be accepted for KT, the influence of these differences in VA and non-VA settings should be examined as potential interventions to reduce racial disparities across the broader US health system.

It is noteworthy that a lack of race disparities was found despite numerous differences identified between the race/ethnicity groups, including age, marital status, study location, hemodialysis, experience of discrimination, perceived racism, medical mistrust, family loyalty, religious objections to LDKT, external locus of control, and transplant knowledge. These results are not surprising, as they demonstrate many of the known differences in the lived experience of various racial and ethnic groups within the US. It is also noteworthy that many of the factors we studied, when included in the multivariable analysis, had no clear influence on time to acceptance for KT in the VA population, despite being identified as predictors of KT in the broader US population.13–21 These findings may reflect differences in the VA population or process; or, the fact that our study is 1 of the first to examine these factors in aggregate, which allowed us to perform a robust analysis to avoid the pitfall of identifying “predictors” which are in fact collinear with other measures.

Another important finding was our identification of several predictors of time to acceptance. Younger candidates experienced a higher likelihood of acceptance for KT, consistent with prior studies.13,47 Prior research showed that older age was strongly associated with overall higher morbidity and mortality, and the reduced rates of acceptance and longer evaluation times are thought to reflect this increased morbidity.48 Patients with a higher burden of medical comorbidity, as assessed by the CCI, had a lower likelihood of acceptance for KT than those with a lower CCI. For each unit increase in the CCI, the risk of not being accepted for KT increased by approximately 11%. Although studies specifically examining the association between medical burden and the likelihood of acceptance for KT are lacking, there are numerous studies that demonstrate a decrease in acceptance in the presence of specific comorbidities included within the CCI, such as diabetes13,49 and coronary artery disease.47 Furthermore, the CCI predicts morbidity and mortality in the post-transplant setting,50,51 and denial of KT,52 which is consistent with our results. This may not be the only factor, however. Monson et al53 demonstrated that the rate of KT evaluation completion decreased precipitously as the number of required tests increased. Because the need for more testing often reflects increased disease burden, it is not surprising that a patient with substantial comorbidities has a more complicated evaluation process with a reduced likelihood of acceptance for KT.

Participants with private insurance in addition to public coverage had a higher likelihood of acceptance for KT than those with public insurance alone. Although this finding is consistent with prior work by Gill et al3, the reason for this disparity is unclear. One possible explanation is that having private insurance allowed patients to complete some required testing outside the VA system, although no data on such practices were obtained during this study. It is also possible that the possession of private insurance is a marker for another demographic characteristic, such as increased employment compensation for either the patient or the patient’s partner, which may be independently associated with a decreased time to complete evaluation.

Married participants were also more likely to be accepted for KT than unmarried ones. This finding is consistent with prior work54–56 that showed better outcomes in married patients with ESKD. Prior studies of chronic illness have demonstrated that married individuals are more adherent to treatment regimens.57–59 Although the availability of a donor spouse may contribute to the disparity in transplant rates between married and un-married patients,54 we found no evidence that either the number of potential donors or having a specific donor candidate identified at the start of the evaluation process was related to acceptance for KT.

Our finding that participants with moderate or greater depression had a higher likelihood of acceptance for KT is particularly important given previous work demonstrating that severe depression is linked to poor outcomes in both the pre- and post-KT settings,20,60,61 and other transplant populations.62 This information suggests a need for pretransplant intervention to address depression to maximize outcomes posttransplant.

Patients without a preference for either DDKT or LDKT had a lower likelihood of acceptance for transplant early in the evaluation process, but the influence of this preference dissipated with time. It is possible that a lack of preference is a sign of ambivalence or a more passive attitude to KT. Thus, patients may be delaying the testing needed to complete evaluation which lowers the likelihood of rapid evaluation completion.

Finally, we note the impact that transplant center had on the likelihood of acceptance for KT with some centers demonstrating a greater likelihood, either throughout the evaluation period or during certain times in each patient’s evaluation period. Although the distribution by race varied across transplant centers (Table 1) the center effect did not disadvantage any racial/ethnic group. This finding suggests that despite unified initial VA screening criteria, the patients, providers, practices, and systems of individual transplant centers continue to have profound impact on the transplant evaluation process. Variation in transplant acceptance patterns has also been documented in the non-VA hospital system.63 These variations should be examined more closely in order to facilitate standardization of evaluation and acceptance practices to minimize geographic disparities in the transplant process, and to allow for the widespread adoption of optimized processes of transplant evaluation.

Our study had limitations. Gill et al3 demonstrated racial disparities in the time it took VA patients to proceed from ESKD to KT, with AA patients having a rate of transplantation less than half that of white patients. Their finding raises the possibility that racial disparities continue to exist before the initiation of the KT evaluation or after waitlisting has occurred. By focusing exclusively on those patients who presented for evaluation at a designated VA KT center, we were unable to evaluate the important issues of disparities in referral for transplantation or the initial preevaluation performed by centralized chart review. Indeed, as we described in the VA referral process (see Methods) there may be referral pattern variability from1 patient’s home VA medical center to another’s. Further, we cannot definitively determine that the differences between our findings and other published reports are not an inherent result of the population served by the VA rather than the VA system itself. It is important to note that some of our patients were censored because they did not complete their evaluation by the end of our study. Finally, although our study investigated many potential predictors of the time to complete KT evaluation, there are predictors, such as time from ESKD diagnosis to referral, or county of residence,64,65 which we did not measure. Future research should examine these factors as well.

In sum, although it is heartening that we identified no racial disparities in the VA during the evaluation process for KT, this should not be taken as a claim that racial disparities in KT do not exist within the VA system. Unfortunately, these disparities have proven to be a pernicious problem which have persisted in the KT process in VA and non-VA settings. Nevertheless, the VA’s success in reducing disparities at least during the KT evaluation process is noteworthy, not only for the 8.76 million US Veterans it serves,66 but also as a case-study and potential model as to how to achieve that equality in other health systems.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the transplant teams and support staff at each study site and the site research coordinators who helped recruit participants and run the study: Malia Reed, Natalie Suiter and Jackie Walczyk. We are especially grateful to our Veteran participants and their family members who made this project possible.

Funding: Work on this project was funded in part by a grant from the VA Health Services Research and Development Department (IIR 06-220), and a grant from the National Institute of Diabetes Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK, R01DK081325).

Abbreviations

- AA

African American

- CCI

Charlson Comorbidity Index

- DD

deceased donor

- DDKT

deceased donor kidney transplantation

- ESKD

end-stage kidney disease

- HR

hazard ratio

- IQR

inter-quartile range

- KT

kidney transplant

- LD

living donor

- LDKT

living donor kidney transplantation

- OM

other minority

- US United States VA

Veterans Affairs

- WH

white.

Footnotes

The contents do not represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government.

Authorship

Michael A Freeman MD - Data Analysis and Interpretation, Draft of Manuscript, Manuscript Approval

John R Pleis MS - Data Analysis (Primary Statistician), Critical Revisions, Manuscript Approval

Kellee Bornemann MPH - Data Acquisition and Analysis, Critical Revisions, Manuscript Approval

Emilee Kohan BA - Data Acquisition and Analysis, Critical Revisions, Manuscript Approval

Mary Amanda Dew PhD - Study Conception and Design, Data Interpretation, Critical Revisions, Manuscript Approval

Chung-Chou H Chang PhD - Study Conception and Design, Data Analysis, Critical Revisions, Manuscript Approval

Galen E Switzer PhD - Study Conception and Design, Data Interpretation, Critical Revisions, Manuscript Approval

Anthony Langone MD - Critical Revisions, Manuscript Approval

Anuja Mittalhenkle MD MPH - Critical Revisions, Manuscript Approval

Somnath Saha MD MPH - Critical Revisions, Manuscript Approval

Mohan Ramkumar MBBS - Study Conception and Design, Critical Revisions, Manuscript Approval

Jareen Adams Flohr RN - Study Conception and Design, Critical Revisions, Manuscript Approval

Christie P Thomas MBBS - Study Conception and Design, Critical Revisions, Manuscript Approval

Larissa Myaskovsky PhD - Study Conception and Design, Data Analysis and Interpretation, Draft of Manuscript and Critical revisions, Manuscript Approval

Disclosures: The authors declare no conflicts of interest

Supporting Information

- Supplemental detail of demographics, medical information, culturally-related factors, psychosocial charactersitics, and transplant knowledge/concerns/preference.

- The plots of smoothed log(HR) functions with 95% confidence bands for the multivariable Cox regression model of transplant center and type of transplant preference.

References

- 1.U.S. Renal Data System. USRDS 2013 Annual Data Report: Atlas of Chronic Kidney Disease and End-Stage Renal Disease in the United States. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fan PY, Ashby VB, Fuller DS, et al. Access and outcomes among minority transplant patients, 1999–2008, with a focus on determinants of kidney graft survival. Am J Transplant. 2010;10(4 Pt 2):1090–1107. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.03009.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gill JS, Hussain S, Rose C, Hariharan S, Tonelli M. Access to kidney transplantation among patients insured by the United States Department of Veterans Affairs. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18(9):2592–2599. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007010050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Joshi S, Gaynor JJ, Bayers S, et al. Disparities among Blacks, Hispanics, and Whites in time from starting dialysis to kidney transplant waitlisting. Transplantation. 2013;95(2):309–318. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31827191d4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johansen KL, Zhang R, Huang Y, Patzer RE, Kutner NG. Association of race and insurance type with delayed assessment for kidney transplantation among patients initiating dialysis in the United States. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;7(9):1490–1497. doi: 10.2215/CJN.13151211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Myaskovsky L, Doebler D, Posluszny D, et al. Perceived discrimination predicts longer time to be accepted for kidney transplant. Transplantation. 2012;93(4):423–429. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e318241d0cd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weng FL, Joffe MM, Feldman HI, Mange KC. Rates of completion of the medical evaluation for renal transplantation. Am J Kidney Dis. 2005;46(4):734–745. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2005.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Purnell TS, Xu P, Leca N, Hall YN. Racial differences in determinants of live donor kidney transplantation in the United States. Am J Transplant. 2013;13(6):1557–1565. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chakkera HA, O'Hare AM, Johansen KL, et al. Influence of race on kidney transplant outcomes within and outside the Department of Veterans Affairs. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16(1):269–277. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2004040333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Young CJ, Kew C. Health disparities in transplantation: focus on the complexity and challenge of renal transplantation in African Americans. Med Clin North Am. 2005;89(5):1003–1031. ix. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2005.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Keith D, Ashby VB, Port FK, Leichtman AB. Insurance type and minority status associated with large disparities in prelisting dialysis among candidates for kidney transplantation. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3(2):463–470. doi: 10.2215/CJN.02220507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ayanian JZ, Cleary PD, Keogh JH, Noonan SJ, David-Kasdan JA, Epstein AM. Physicians' beliefs about racial differences in referral for renal transplantation. Am J Kidney Dis. 2004;43(2):350–357. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2003.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schold JD, Gregg JA, Harman JS, Hall AG, Patton PR, Meier-Kriesche HU. Barriers to evaluation and wait listing for kidney transplantation. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6(7):1760–1767. doi: 10.2215/CJN.08620910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Axelrod DA, Dzebisashvili N, Schnitzler MA, et al. The interplay of socioeconomic status, distance to center, and interdonor service area travel on kidney transplant access and outcomes. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5(12):2276–2288. doi: 10.2215/CJN.04940610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Myaskovsky L, Almario Doebler D, Posluszny DM, et al. Perceived discrimination predicts longer time to be accepted for kidney transplant. Transplantation. 2012;93(4):423–429. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e318241d0cd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Prieto LR, Miller DS, Gayowski T, Marino IR. Multicultural issues in organ transplantation: the influence of patients' cultural perspectives on compliance with treatment. Clin Transplant. 1997;11(6):529–535. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rodrigue JR, Cornell DL, Kaplan B, Howard RJ. A randomized trial of a home-based educational approach to increase live donor kidney transplantation: effects in blacks and whites. Am J Kidney Dis. 2008;51(4):663–670. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2007.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Waterman AD, Barrett AC, Stanley SL. Optimal transplant education for recipients to increase pursuit of living donation. Prog Transplant. 2008;18(1):55–62. doi: 10.1177/152692480801800111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Waterman AD, Stanley SL, Covelli T, Hazel E, Hong BA, Brennan DC. Living donation decision making: recipients' concerns and educational needs. Prog Transplant. 2006;16(1):17–23. doi: 10.1177/152692480601600105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chilcot J, Spencer BW, Maple H, Mamode N. Depression and kidney transplantation. Transplantation. 2014;97(7):717–721. doi: 10.1097/01.TP.0000438212.72960.ae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Noohi S, Khaghani-Zadeh M, Javadipour M, et al. Anxiety and depression are correlated with higher morbidity after kidney transplantation; Paper presented at: Transplantation proceedings; 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grubbs V, Gregorich SE, Perez-Stable EJ, Hsu C-y. Health literacy and access to kidney transplantation. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4(1):195–200. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03290708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Delmonico F Council of the Transplantation Society. A report of the Amsterdam Forum on the care of the live kidney donor: Data and medical guidelines. Transplantation. 2005;79(2S):S53–S66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Charlson M, Pompei P, Ales K, Mackenzie C. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jassal SV, Schaubel DE, Fenton SSA. Baseline comorbidity in kidney transplant recipients: A comparison of comorbidity indices. Transplantation. 2005;46(1):136–142. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2005.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bird ST, Bogart LM. Perceived race-based and socioeconomic status (SES)-based discrimination in interactions with health care providers. Ethn Dis. 2001;11:554–563. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bird ST, Bogart LM. Birth control conspiracy beliefs, perceived discrimination, and contraception among African Americans: An exploratory study. J Health Psychol. 2003;8(2):263–276. doi: 10.1177/1359105303008002669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Williams DR, Yu Y, Jackson JS, Anderson N. Racial differences in physical and mental health: Socio-economic status, stress, and discrimination. J Health Psychol. 1997;2(3):335–351. doi: 10.1177/135910539700200305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.LaVeist TA, Nickerson KJ, Bowie JV. Attitudes about racism, medical mistrust, and satisfaction with care among African-American and White cardiac patients. Med Care Res Rev. 2000;57(Suppl 1):146–161. doi: 10.1177/1077558700057001S07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boulware LE, Ratner LE, Ness PM, et al. The contribution of sociodemographic, medical, and attitudinal factors to blood donation among the general public. Transfusion. 2002;42:669–678. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.2002.00120.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.LaVeist TA, Isaac LA, Williams KP. Mistrust of Health Care Organizations Is Associated with Underutilization of Health Services. Health Serv Res. 2009;44(6):2093–2105. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2009.01017.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Anderson LA, Dedrick RF. Development of the Trust in Physician Scale: A measure to assess interpersonal trust in patient-physician relationships. Psychol Rep. 1990;67:1091–1100. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1990.67.3f.1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bardis P. A familism scale. J Marriage Fam. 1959;21:340–341. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rumsey S, Hurford DP, Cole AK. Influence of knowledge and religiousness on attitudes toward organ donation. Transplant Proc. 2003;35:2845–2850. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2003.10.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Myaskovsky L, Burkitt KH, Lichy AM, et al. The association of race, cultural factors, and health-related quality of life in persons with spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2011;92(3):441–448. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2010.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Derogatis L, Spencer P. Clinical Psychometric Research. Baltimore, MD: 1975. The Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI): Administration, Scoring, and Procedures Manual. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rosenberg M. Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pearlin L, Schooler C. The structure of coping. J Health Soc Behav. 1978;19:2–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wallston KA, Stein MJ, Smith CA. Form C of the MHLC Scales: A Condition-Specific Measure of Locus of Control. J Pers Assess. 1994;63(3):534–553. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa6303_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Murray LR, Conrad NE, Bayley E. Perceptions of kidney transplant by persons with end stage renal disease. Anna Journal. 1999;26(5):479–483. 500. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gray RJ. A class of K-sample tests for comparing the cumulative incidence of a competing risk. Ann Stat. 1988;16(3):1141–1154. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ren Y, Chang C-CH, Zenarosa GL, et al. Gray’s Time-Varying Coefficients Model for Posttransplant Survival of Pediatric Liver Transplant Recipients with a Diagnosis of Cancer. Comput Math Methods Med. 2013 doi: 10.1155/2013/719389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Patzer R, Perryman J, Pastan S, et al. Impact of a patient education program on disparities in kidney transplant evaluation. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;7(4):648–655. doi: 10.2215/CJN.10071011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Waterman A, Peipert J, Hyland S, McCabe M, Schenk E, Liu J. Modifiable patient characteristics and racial disparities in evaluation completion and living donor transplant. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;8:995–1002. doi: 10.2215/CJN.08880812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Clark CR, Hicks LS, Keogh JH, Epstein AM, Ayanian JZ. Promoting access to renal transplantation: the role of social support networks in completing pre-transplant evaluations. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(8):1187–1193. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0628-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chisholm-Burns MA, Spivey CA, Wilks SE. Social support and immunosuppressant therapy adherence among adult renal transplant recipients. Clin Transplant. 2010;24(3):312–320. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0012.2009.01060.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lenihan CR, Hurley MP, Tan JC. Comorbidities and kidney transplant evaluation in the elderly. Am J Nephrol. 2013;38(3):204–211. doi: 10.1159/000354483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yang W, Xie D, Anderson AH, et al. Association of kidney disease outcomes with risk factors for CKD: findings from the Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2014;63(2):236–243. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2013.08.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Alexander GC, Sehgal AR. Why hemodialysis patients fail to complete the transplantation process. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2001;37(2):321–328. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2001.21297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wu C, Evans I, Joseph R, et al. Comorbid Conditions in Kidney Transplantation: Association with Graft and Patient Survival. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16(11):3437–3444. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005040439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Grosso G, Corona D, Mistretta A, et al. Predictive Value of the Charlson Comorbidity Index in Kidney Transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2012;44(7):1859–1863. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2012.06.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kiberd B, Boudreault J, Bhan V, Panek R. Access to the Kidney Transplant Wait List. American Journal of Transplantation. 2006;6(11):2714–2720. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01523.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Monson RS, Kemerley P, Walczak D, Benedetti E, Oberholzer J, Danielson KK. Disparities in completion rates of the medical prerenal transplant evaluation by race or ethnicity and gender. Transplantation. 2015;99(1):236–242. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000000271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Khattak MW, Sandhu GS, Woodward R, Stoff JS, Goldfarb-Rumyantzev AS. Association of marital status with access to renal transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2010;10(12):2624–2631. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2010.03318.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tanno K, Ohsawa M, Itai K, et al. Associations of marital status with mortality from all causes and mortality from cardiovascular disease in Japanese haemodialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2013;28(4):1013–1020. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfs547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Naiman N, Baird BC, Isaacs RB, et al. Role of pre-transplant marital status in renal transplant outcome. Clin Transplant. 2007;21(1):38–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0012.2006.00575.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wu JR, Lennie TA, Chung ML, et al. Medication adherence mediates the relationship between marital status and cardiac event-free survival in patients with heart failure. Heart Lung. 2012;41(2):107–114. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2011.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kugler C, Maeding I, Russell CL. Non-adherence in patients on chronic hemodialysis: an international comparison study. J Nephrol. 2011;24(3):366–375. doi: 10.5301/JN.2010.5823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Trivedi R, Ayotte B, Edelman D, Bosworth H. The association of emotional well-being and marital status with treatment adherence among patients with hypertension. J Behav Med. 2008;31(6):489–497. doi: 10.1007/s10865-008-9173-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Palmer SC, Vecchio M, Craig JC, et al. Association between depression and death in people with CKD: a meta-analysis of cohort studies. Am J Kidney Dis. 2013;62(3):493–505. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2013.02.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zelle DM, Dorland HF, Rosmalen JG, et al. Impact of depression on long-term outcome after renal transplantation: a prospective cohort study. Transplantation. 2012;94(10):1033–1040. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31826bc3c8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dew MA, Rosenberger EM, Myaskovsky L, et al. Depression and anxiety as risk factors for morbidity and mortality after organ transplantation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Transplantation. 2015;100(5):988–1003. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000000901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Axelrod DA, Lentine KL, Xiao H, et al. Accountability for end-stage organ care: implications of geographic variation in access to kidney transplantation. Surgery. 2014;155(5):734–742. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2013.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Schold J, Heaphy E, Buccini L, et al. Prominent impact of community risk factors on kidney transplant candidate processes and outcomes. Am J Transplant. 2013;13(9):2374–2383. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Myaskovsky L, Pleis J, Ramkumar M, Langone A, Saha S, Thomas C. Fewer race disparities in the National VA Kidney Transplant Program. Am J Transplant. 2014;14(S3):827. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Veterans Health Administration. VA. [Updated 2015. Accessed 3/16/16]; http://www.va.gov/health/

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.