Abstract

We describe the series of iterative steps used to develop a smoking relapse-prevention intervention customized to the needs of cancer patients. Informed by relevant literature and a series of preliminary studies, an educational tool (DVD) was developed to target the unique smoking relapse risk factors among cancer patients. Learner verification interviews were conducted with 10 cancer patients who recently quit smoking to elicit feedback and inform the development of the DVD. The DVD was then refined using iterative processes and feedback from the learner verification interviews. Major changes focused on visual appeal, and the inclusion of additional testimonials and graphics to increase comprehension of key points and further emphasize the message that the patient is in control of their ability to maintain their smoking abstinence. Together, these steps resulted in the creation of a DVD titled Surviving Smokefree®, which represents the first smoking relapse-prevention intervention for cancer patients. If found effective, the Surviving Smokefree® DVD is an easily disseminable and low-cost portable intervention which can assist cancer patients in maintaining smoking abstinence.

Introduction

A growing body of research has demonstrated that for individuals diagnosed with cancer, continued smoking is associated with several adverse health outcomes including a reduction in cancer treatment efficacy, increased risk of developing a second primary cancer, decreased quality of life, and poorer survival [1, 2]. In 2014, the Surgeon General’s report concluded that sufficient evidence exists to demonstrate a causal link between continued smoking and poor cancer outcomes for patients and survivors [3]. Given the numerous potential negative outcomes, cancer patients can benefit significantly from abstaining from smoking both during and after treatment. Many patients who smoke will make a quit attempt when first diagnosed, yet smoking relapse rates among cancer patients range from 13% to 60% across studies [4, 5]. Hence, the development of smoking relapse-prevention interventions is critical to support cancer patients with maintaining smoking abstinence to optimize treatment outcomes.

Brandon and colleagues [6, 7] previously conducted two randomized controlled trials demonstrating the efficacy of a low-cost, self-help smoking relapse-prevention intervention for ex-smokers (i.e., a booklet series entitled, Forever Free®). Specifically, these Forever Free® booklets significantly reduced smoking relapse through two years of follow-up among individuals who had recently quit smoking. The content of the 8-booklet, Forever Free® series covers essential topics in maintaining abstinence such as how to cope with smoking urges, understanding nicotine dependence, the link between smoking, stress, and mood, and tips for maintaining a life without cigarettes. Although the content of the booklets is relevant for both healthy populations and cancer patients, additional unique challenges exist for cancer patients that must be considered [8-10]. Examples include: delayed smoking relapse rates, pain and fatigue related to cancer treatment, cancer-specific risks of continued smoking (immediate and long-term), and cancer-relevant benefits of quitting (e.g., improved respiratory functioning). Thus, building on this prior research, and to address an educational gap, we developed a DVD (titled Surviving Smokefree®) specifically targeted to cancer patients who have recently quit smoking. Based on findings from our formative work with cancer patients, [11] and the advantages of audio-visual education as opposed to solely text based education [12], the DVD modality was selected as the ideal method to address and communicate these unique factors. Importantly, this multimodal smoking relapse-prevention intervention offers a low cost, highly disseminable, and potentially scalable intervention.

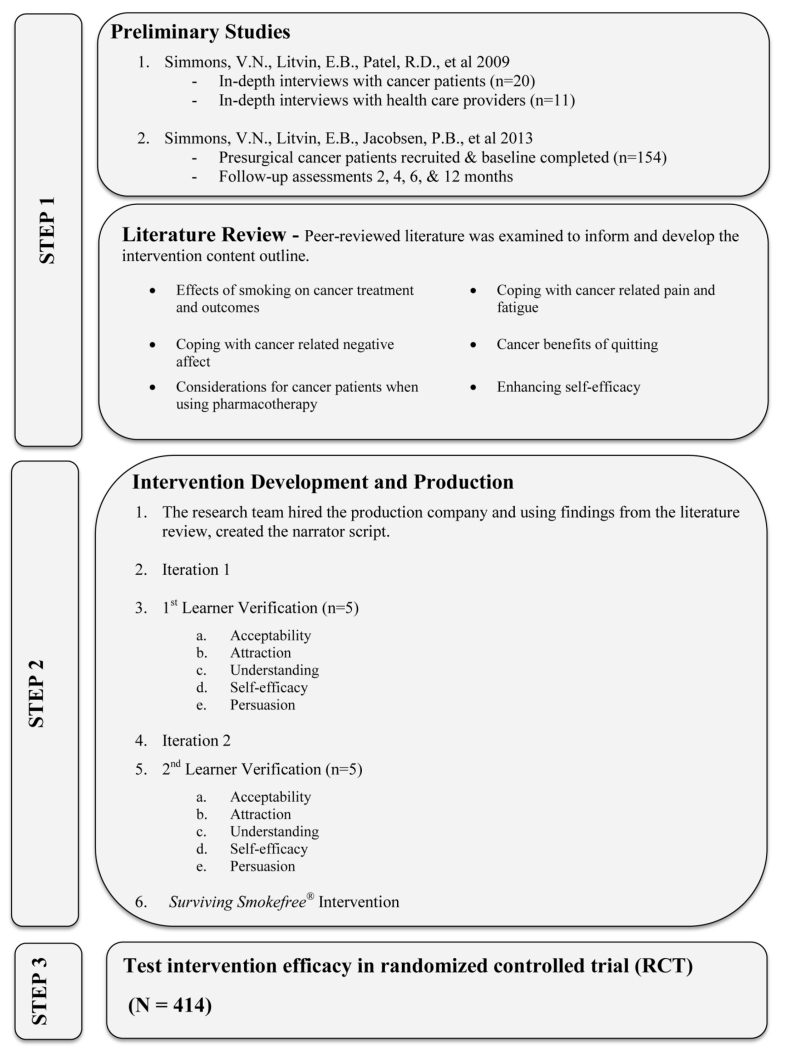

Our overarching goal was to provide cancer patients who had recently quit smoking with a set of useful educational tools to help them maintain tobacco abstinence. The purpose of this paper is to describe the series of iterative steps leading to the development of the targeted DVD (Figure 1). First, we summarize Step I which involved a review of the existing literature, as well as building on our series of preliminary studies. Next, Step II (learner verification interviews) informed the production of the targeted smoking relapse-prevention intervention. In Step III, the final educational product (DVD) is currently being evaluated in a randomized controlled trial (RCT).

Figure 1.

Methods

Step I – Preliminary Studies

We first conducted a qualitative study [11] to examine cancer patient-provider communication regarding tobacco use, smoking cessation, and relapse within the oncology setting. In-depth interviews were conducted with 20 current and former smokers who had recently been diagnosed with thoracic cancer or head and neck cancers, as well as 11 health care providers (e.g., oncology nurses, head/neck and thoracic surgeons, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants) from a large NCI designated cancer center in the Southeast. The interviews sought to explore: 1) patients’ motivation, reasons, and support for quitting, 2) openness to and use of cessation treatments, 3) patient and provider perspectives on stigma and guilt, and 4) barriers to communication regarding relapse prevention. Findings from patient interviews revealed a strong preference for messages that highlight the benefits of cessation (vs. the risks of continued smoking), as well as a lack of awareness regarding the cancer-specific, short-term benefits of smoking cessation. Other key findings suggest that most patients do not ask for assistance to quit smoking due to the stigma of smoking and cancer, and patients felt that the message received regarding cessation was not strong. Further, patients were often reluctant to disclose to their provider if they had resumed smoking. Finally, patients were also asked to provide feedback on the existing Forever Free® booklets, as well as discuss an optimal relapse prevention intervention modality (i.e., booklets, DVD, in-person). Patients reported that the Forever Free® booklets were appealing in both content and visual appearance, and also expressed high preference for visual materials in addition to printed materials.

Findings from the health care provider interviews suggested that, although most providers were comfortable discussing and providing smoking-related information to their patients, providers vary in their awareness and understanding to relapsed patients’ feelings. Although providers reported asking all patients about current smoking status and advising current smokers to quit, only a few providers mentioned the risks of continued smoking on cancer treatment to their patients. Further, provider involvement in cessation assistance and relapse-prevention was limited [11]. Our findings, along with others [14,15], demonstrated that the large majority of cancer patients who are smoking at the time of diagnosis make an attempt to quit smoking, thus making this a “teachable and optimal moment” for delivering a smoking relapse-prevention intervention.

A subsequent longitudinal study [8] was completed with 154 cancer patients who recently quit smoking and were scheduled to undergo surgical cancer treatment. Smoking status was collected pre-surgery (i.e., baseline) and at each follow-up time point (2, 4, 6, and 12 months). High rates of relapse were found among patients post-treatment, supporting the need for smoking relapse-prevention interventions to promote higher rates of long-term abstinence. Importantly, several modifiable variables such as high depression proneness, lower self-efficacy for quitting, greater fears about cancer recurrence, and low risk perceptions related to continued smoking were identified as predictors of relapse and potential content areas to target in future interventions.

In addition to the preliminary work described above, our research team conducted an extensive review of the literature to gain a better understanding of the factors associated with smoking relapse among the cancer patient population. Findings from this review were compiled and used to generate a list of key content areas (Table 1), and subsequently draft the intervention content outline.

Table 1.

DVD Implementation of Key Content

| RELAPSE-PREVENTION INTERVENTION CONTENT | METHOD USED TO CONVEY CONTENT IN DVD |

|---|---|

| Coping with Cancer related Negative Affect |

|

| Cognitive Behavioral Coping Skills for Smoking urges |

|

| Cancer Specific smoking-risks: Immediate Risks Cancer treatment effectiveness Wound healing Treatment side effects Future Risks Secondary malignancies Cancer recurrence |

|

| Cancer benefits of quitting, (e.g. QOL) |

|

| Coping skills for with cancer pain and fatigue |

|

| Enhancing Self-Efficacy |

|

| Patient Testimonials from those successful at maintaining abstinence |

|

| Important considerations for cancer patients using pharmacotherapy |

|

| Eliciting social support |

|

Step II - Intervention Development and Production

Development of the Surviving Smokefree® DVD was guided by NCI’s Health Communication Model, a framework that offers a continuous loop of planning, implementation, and improvement. Further, Doak and colleagues [13] encourage the use of learner verification to evaluate educational messages delivered in modalities such as a pamphlet or DVD. This methodology allows investigators to assess the suitability of the educational materials (attraction, cultural acceptability, understanding (literacy), efficacy, and persuasion) among the intended audience to reduce miscommunication of messages [14-16]. In this case, we wanted the smoking relapse message to resonate with cancer patients who were trying to stay quit. As such, learner verification was utilized as the DVD moved from concept to the final product to improve the overall effectiveness and utility.

An interdisciplinary team was assembled to guide the development of the Surviving Smokefree® DVD. The team consisted of faculty and staff from Moffitt Cancer Center (MCC), as well as two collaborators from partnering NCI-designated comprehensive cancer centers. Within the team, there were seven faculty members with significant expertise in the fields of smoking cessation, health communication, patient education, and oncology. The research team sought to examine and select the best strategies to convey the key content areas throughout the DVD to improve understanding, increase credibility, and aid patients in making health related decisions (Table 1). For example, patient role modeling was selected to visually demonstrate coping skills that could be used to alleviate cancer related pain and fatigue [17]. A video production plan was established which included all aspects of the DVD development including but not limited to: development of a creative brief and script, and plans for recruitment of patients, providers, and smoking cessation and medical experts for interviews and testimonials.

An integral part of this project was our partnership with the video production company that assisted with the creative development process. As we interviewed companies, a key requirement was their understanding of the iterative process needed to garner feedback from patients, consultants, and key physician stakeholders. The ultimate goal was to create an educational product that was visually interesting, crisp, and engaging. Together, the team collaborated to develop an initial DVD script based on the creative brief. Content areas include topics such as: coping with cancer related negative affect, enhancing self-efficacy, pharmacotherapy, and social support as identified from the literature [18]. Unique factors experienced by cancer patients included cancer-specific smoking risks (immediate and long term), cancer-related benefits of quitting, and coping skills for cancer pain and fatigue. Further, prior research [19], along with our previous qualitative findings [11], demonstrated that patients had a preference for positive health message framing. Thus, as the script developed, an effort was made to communicate messages positively (e.g. discussing the benefits staying smoke free as compared to the consequences of relapsing and returning to smoking), which is often more persuasive and effective [19]. This approach has been found to be effective at communicating health related topics such as quitting smoking [20].

Patient Testimonials

An integral aspect of our DVD was the use of patient testimonials (narrative communication). Previous research demonstrated that using narrative communication can have indirect and direct effects on engagement, cognition, cognitive rehearsal, recall, affect, and behavioral correlates [17]. Specifically, first person narrative has been found to have a persuasive effect when used to aid patients in making health-related decisions. [21]. Thus, we sought to include cancer survivor testimonials in which former smokers could offer their perspectives about the benefits of staying smoke free upon cancer treatment and outcome, describe ways to overcome the emotional and physical challenges related to cancer diagnosis, and offer specific strategies to combat urges to smoke.

The team sought to identify a diverse group of patients with respect to age, ethnicity, and cancer type. Patients were first identified via medical record screening, and then contacted by phone to confirm smoking status. Abstinent patients were then invited to take part in the DVD production by participating in an interview regarding their smoking history, quit attempt, and cancer diagnosis. The testimonial interviews were approximately 45 minutes in length and were guided by a set of questions aimed to capture patient perspectives regarding smoking cessation strategies and relevant smoking relapse-prevention topics. Example quotations included in the video are provided below.

Patients relayed the benefits of quitting smoking:

“I don’t cough anymore. I can breathe. Before I can’t even walk past my block, around the block without stopping, gasping for breath.”

“If you stop smoking, you will feel better. You breathe better. You will see your energy level go up and that’s all it takes, you know. It’s really true. ”

Patients described the mental and behavioral coping skills they used to help cope with urges to smoke:

“Every time I have any type of desire now, which is very few and far between, I think of being wrapped up in a mask which was worn for me during radiation treatment. They covered my face, my whole chest and I was literally bolted to a table.”

“You know, whether a hobby, you have to do something to keep entertained and keep it off your mind, because if you’re lying around and just all you’re thinking about is, you know, I’m sick, or you know, I’m bored or there’s nothing, you know you’re probably going to pick up a cigarette.”

“It’s a mental thing. It’s something that you have to continually fight and mentally and physically you just have to take charge of yourself. And stay away from it. And it’s hard. It’s a bad habit. It’s a bad habit, but you just have to make up your mind that I’m in charge of my body and I’m going to take control.”

Expert Testimonial Tapings

Prior research has supported the potential impact of using high-credibility sources such as physicians and/or scientific experts for the delivery of health related messages [22, 23]. Thus, interviews were conducted with health care professionals from MCC. Physician interviews included in the DVD focused on the importance of achieving smoking abstinence and the possible effects continued smoking can have on one’s cancer treatment and outcomes, such as decreased survival rates, increased risk of cancer recurrence, and greater risk of developing a second cancer.

“So, for instance, in people that have had an early stage lung cancer and we recommend them having some post-operative chemotherapy to increase their odds of being cured, if they continue to smoke they may be blocking the effects of chemotherapy. So they get the toxicity of the chemotherapy but they don’t get the benefit.”

Additionally, the smoking cessation expert described behavioral as well as cognitive coping skills that have shown to be highly effective when dealing with urges to smoke (e.g., taking deep breaths, going for a walk, telling yourself smoking is not an option).

“Behavioral coping responses, on the other hand, are things that you can physically do to distract yourself from that craving; going for a walk, taking a drink of water, taking deep breaths, calling a friend, fiddling with a pencil, chewing gum. Almost anything can be a behavioral coping response.”

Learner Verification and Revision

As the DVD advanced, two rounds of one-on-one, semi-structured interviews were conducted with patients who fit the inclusion criteria for the planned RCT (i.e., patients receiving treatment at MCC who had recently quit smoking). A sample of 10 participants is generally considered sufficient when conducting learner verification; therefore 5 participants were recruited for each of the two iterations [14]. All eligible patients completed informed consent and viewed an initial draft of the DVD. Interviews lasted approximately 30-45 minutes and patients were compensated $25 for their participation. Each interview was audio recorded and transcribed by a member of the research team.

An interview guide was developed to assess the key elements of learner verification: attraction, acceptability, understanding, self-efficacy, and persuasion. [13]. More specifically, interview questions aimed to: 1) evaluate if the patients found the DVD appealing, 2) gauge the patients’ comprehension of the DVD’s key messages, 3) evaluate if the main message persuaded the patients to take action, and 4) assess if the patient testimonials were relatable and acceptable. For example, participants were asked such questions as: “What do you think is the main message here?”; “Was there anything about the material that bothered you?”; Do you feel the suggestions given in this video are realistic and doable?”. Interviews were audio-recorded and data was tabulated and summarized to direct modifications and revisions for the next draft. Feedback was reviewed by the research team and revisions were agreed upon through consensus. During the revision process, additional B-roll (i.e., alternative footage intercut with the main shot) was filmed to assist and enhance the delivery of the DVD’s key messages. During the second round of interviews, revisions made after the first iteration were assessed for acceptability. Feedback from the patient interviews and expert reviews were incorporated to produce the final version of the DVD.

Learner Verification Results

Participant Characteristics

Participants (N=10) were primarily white (90%) and female (60%). The mean age of the participants was 59.0 years (SD=12.3; range 43-82). With respect to previous smoking history, participants smoked an average of 25.0 (SD=11.2) cigarettes per day (CPD), and average lifetime years smoked was 37.0 (SD=14.5). Six participants had various cancer types (i.e. multiple myeloma, colon cancer, pancreatic cancer, Hodgkin’s lymphoma, and chronic lymphocytic leukemia), whereas the remaining sample consisted of 2 participants with lung cancer and 2 participants with head and neck cancer.

Appeal of the DVD

A number of visual and audio elements were evaluated. The majority of participants preferred a female narrator over a host in the video. Overall, most participants felt that the music selected for the DVD should be cheerful and upbeat, unlike “elevator” music. When viewing an early version of the DVD, one participant said the music “needs to change to something less sleepy; it’s too mellow.” A more uplifting tune was selected and deemed acceptable during the next round of interviews. Additionally, all of the participants preferred having a visual prompt (i.e., text) appear on the screen to highlight take home messages, but emphasized the importance of not displaying too much text at one time. Duration of the DVD (14 minutes) was also assessed and found to be acceptable to the majority of the participants. In addition, the team garnered feedback on multiple versions of a DVD case to ensure appeal of the final product. When shown samples, mixed opinions were received and it was suggested to display images of “the actual survivors” on the cover. As a result, a revised DVD case was designed to incorporate images of the survivors who appeared throughout the DVD.

Comprehension of Key Messages

After viewing the DVD, participants were asked to provide examples of the key content areas to ensure messages were being communicated effectively. These included coping methods, health benefits related to their cancer diagnosis, risks of continued smoking, and quit smoking aids. Overall, the majority of participants were able to provide examples for each content area. A few participants suggested the use of visual images to better explain behavioral and mental coping skills. For example, participants initially had difficulty recalling the strategies suggested for coping with pain and fatigue. One participant stated, “I would like to see more images [of coping strategies].” To address this concern, a graphic was created of a prescription notepad to slowly display the suggestions one-by-one, providing the patients with a visual list of the recommended strategies. Additionally, the research team filmed and incorporated footage of patients demonstrating behavioral and mental coping methods (e.g., walking through the park, spending time with friends, exercising). Several patients expressed difficulty understanding the explanation of nicotine withdrawal and its impact on stress and smoking urges. Originally, this concept was explained verbally by the smoking cessation expert. To improve participants’ understanding, the research team worked together with the video production company to create a simple, animated graph explaining this relationship. After this revision, patients were better able to understand the process of nicotine withdrawal and its impact on stress and smoking urges.

Does the Main Message Persuade You to Remain Smoke Free?

During the first round of interviews, participants had mixed opinions about whether the DVD motivated them to take action (i.e., remain smoke free). One participant believed maintaining abstinence would only come from an “inner power.” Another participant did not believe his smoking was related to his cancer and, therefore, was not motivated to maintain his smoking abstinence. However, the majority of participants found the DVD motivating. One participant said, “[the DVD] brings more confidence that I’ll be able to do this.” In response to this feedback, the research team sought to increase motivation by emphasizing the message that the patients are in control of their smoking behavior and their ability to achieve and maintain a smoke-free life. This was accomplished by including additional patient testimonial footage (expressing their belief that their ability to remain smoke-free was “in their control”), and by including onscreen text to visually relay the message “you are in control.” These additions were received positively by participants and viewed as motivational.

Relatability and Acceptability of Patient Testimonials

The vast majority of participants felt they were easily able to relate to the patients in the video. Participants reported relating to both receiving a cancer diagnosis and struggling to quit smoking. Patients also expressed interest in the inclusion of additional patient testimonials to convey the difficulty of staying smoke-free. Based on these suggestions, additional footage from the testimonials was incorporated.

Discussion

Smoking abstinence among cancer patients is essential to improve cancer treatment outcomes and reduce recurrence, thus warranting the need for improved, effective treatment approaches. Recently, the American Association for Cancer Research (AACR), the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) all recommended that cancer patients who smoke be provided with evidence-based tobacco cessation assistance [24, 25]. Consistent with these priorities, our intervention seeks to provide an evidence-based relapse-prevention educational tool for this vulnerable population of smokers.

Our development process involved a series of iterative steps and included numerous stakeholders (physicians, scientific experts, and cancer survivors) to ensure that the content, format, and overall approach was consistent with learning characteristics and information needs of the intended audience. Central to this project was drawing upon existing literature, our prior smoking relapse research with cancer patients [8, 11], and integrating findings from the learner verification interviews. Feedback from the learner verification interviews (Table 1) were used to make numerous adjustments including incorporating additional testimonials and graphics to improve comprehension and modifying visual and auditory elements of the DVD to enhance appeal (e.g., using uplifting music, slowing narration speed, adding text graphics)

Findings from the learner verification interviews highlight the utility of this process to obtain valuable feedback from the intended audience. Although prior research has also successfully utilized the learner verification process to develop educational materials [14, 15], this method has not been used widely across research studies. The use of learner verification in the current study supports its ability to target and assess specific elements of educational materials such as the design, language, relevance, and message comprehension. Further, it demonstrates the value in obtaining the opinions of the target audience throughout the development process.

The intervention was only produced in an English version; however the team is planning future studies that involve transcreation of the intervention for Spanish-language populations. The current project utilized a DVD modality, which could be delivered on the internet and mobile devices allowing the intervention to be used in clinic settings (e.g., inpatient hospital rooms, clinic waiting rooms).

Step III is to test the efficacy of this multimodal empirically-based, targeted smoking-relapse prevention intervention for cancer patients in an ongoing clinical RCT with follow-up through 12 months. Recently diagnosed cancer patients, that had quit smoking within the past 90 days (N=414), are recruited and randomized to one of two arms; Usual Care (UC) and Smoking Relapse Prevention (SRP). The UC group receives standard of care (i.e. a brief clinical smoking intervention provided by the institution’s Tobacco Treatment Specialist), while the SRP group will receive standard of care, the Surviving Smokefree® DVD, and Forever Free® booklets. If this multimodal intervention is shown to be effective, the focus will shift to dissemination and implementation.

Conclusion

The Surviving Smokefree® DVD was developed utilizing an iterative process, guided by formative research and a learner verification approach, in which patients, providers, and scientific experts uniquely contributed to the development of the relapse prevention intervention. The formative data collected from the participants played a significant role in the development process, thus enabling us to create a patient-centered intervention that was deemed acceptable for the intended audience.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01CA154596-02 ).

References

- [1].Ostroff JS, Jacobsen PB, Moadel AB, Spiro RH, Shah JP, Strong EW, et al. Prevalence and predictors of continued tobacco use after treatment of patients with head and neck cancer. Cancer. 1995;75:569–76. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19950115)75:2<569::aid-cncr2820750221>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Schnoll RA, James C, Malstrom M, Rothman RL, Wang H, Babb J, et al. Longitudinal predictors of continued tobacco use among patients diagnosed with cancer. Ann Behav Med. 2003;25:214–22. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2503_07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].U.S. Department of Health and Human Services . The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- [4].Dresler CM, Bailey M, Roper CR, Patterson GA, Cooper JD. Smoking cessation and lung cancer resection. Chest. 1996;110:1199–202. doi: 10.1378/chest.110.5.1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Walker MS, Larsen RJ, Zona DM, Govindan R, Fisher EB. Smoking urges and relapse among lung cancer patients: findings from a preliminary retrospective study. Prev Med. 2004;39:449–57. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.04.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Brandon TH, Collins BN, Juliano LM, Lazev AB. Preventing relapse among former smokers: a comparison of minimal interventions through telephone and mail. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;68:103–13. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.1.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Brandon TH, Meade CD, Herzog TA, Chirikos TN, Webb MS, Cantor AB. Efficacy and cost-effectiveness of a minimal intervention to prevent smoking relapse: dismantling the effects of amount of content versus contact. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2004;72:797–808. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.5.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Simmons VN, Litvin EB, Jacobsen PB, Patel RD, McCaffrey JC, Oliver JA, et al. Predictors of smoking relapse in patients with thoracic cancer or head and neck cancer. Cancer. 2013;119:1420–7. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Ditre JW, Gonzalez BD, Simmons VN, Faul LA, Brandon TH, Jacobsen PB. Associations between pain and current smoking status among cancer patients. Pain. 2011;152:60–5. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Egestad H, Emaus N. Changes in health related quality of life in women and men undergoing radiation treatment for head and neck cancer and the impact of smoking status in the radiation treatment period. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2014;18:339–46. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2014.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Simmons VN, Litvin EB, Patel RD, Jacobsen PB, McCaffrey JC, Bepler G, et al. Patient–provider communication and perspectives on smoking cessation and relapse in the oncology setting. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;77:398–403. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.09.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Stellefson M, Chaney BH, Chaney JD. Examining the efficacy of DVD technology compared to print-based material in COPD self-management education of rural patients. Calif J Health Promot. 2009;7:26–42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Doak CCDL, Root JHT. Teaching Patients with Low Literacy Skills. 2nd ed. JB Lipponcott Co.; Philadelphia, PA: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- [14].Doak LG, Doak CC, Meade CD. Strategies to improve cancer education materials. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1996;23:1305–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Hunter J, Kelly PJ. Imagined anatomy and other lessons from learner verification interviews with Mexican immigrant women. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2012;41:E1–E12. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2012.01410.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Weston C, LeMaistre C, McAlpine L, Bordonaro T. The influence of participants in formative evaluation on the improvement of learning from written instructional materials. Instructional Science. 1997;25:369–86. [Google Scholar]

- [17].McQueen A, Kreuter MW, Kalesan B, Alcaraz KI. Understanding narrative effects: the impact of breast cancer survivor stories on message processing, attitudes, and beliefs among African American women. Health Psychol. 2011;30:674–82. doi: 10.1037/a0025395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Fiore MCJC, Baker TB, et al. Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence: 2008 Update. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Public Health Service; Rockville, MD: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- [19].Shamaskin AM, Mikels JA, Reed AE. Getting the message across: age differences in the positive and negative framing of health care messages. Psychol Aging. 2010;25:746–51. doi: 10.1037/a0018431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Rothman AJ, Salovey PG, Antone C, Keough K, Martin CD. The influence of message framing on intentions to perform health behaviors. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology and Aging. 1993;29:408–33. [Google Scholar]

- [21].Ubel PA, Jepson C, Baron J. The inclusion of patient testimonials in decision aids: effects on treatment choices. Med Decis Making. 2001;21:60–8. doi: 10.1177/0272989X0102100108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Katz ML, Heaner S, Reiter P, van Putten J, Murray L, McDougle L, et al. Development Of An Educational Video To Improve Patient Knowledge And Communication With Their Healthcare Providers About Colorectal Cancer Screening. Am J Health Educ. 2009;40:220–8. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2009.40-220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Knobloch-Westerwick S, Johnson BK, Westerwick A. To Your Health: Self-Regulation of Health Behavior Through Selective Exposure to Online Health Messages. J Commun Disord. 2013;63:807–29. [Google Scholar]

- [24].Hanna N, Mulshine J, Wollins DS, Tyne C, Dresler C. Tobacco cessation and control a decade later: American society of clinical oncology policy statement update. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:3147–57. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.48.8932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Toll BA, Brandon TH, Gritz ER, Warren GW, Herbst RS, Tobacco ASo, et al. Assessing tobacco use by cancer patients and facilitating cessation: an American Association for Cancer Research policy statement. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:1941–8. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-0666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]