Introduction

The natural history of gout includes 4 progressive stages (asymptomatic hyperuricemia, acute arthritic attacks, intercritical gout, and chronic gouty arthritis).1 Asymptomatic hyperuricemia is characterized by elevated serum urate. Deposition of monosodium urate (MSU) crystals in articular and periarticular tissues then instigates acute arthritic attacks. Intercritical gout eventually results in chronic gouty arthritis with no pain-free intervals.

Tophi, MSU crystal aggregates, are primarily associated with chronic gout. Common locations for tophus development include the helix of the ear, olecranon bursa, hands, knees, feet, and fingers.2, 3 There are few reports of tophaceous deposits on the fingertips. Finger pad tophi have been reported in individuals without prior acute gouty arthritis. Finger pad tophi represent a dermatologic presenting feature of gout and an indication for prompt initiation of urate-lowering therapy (ULT) to prevent sequelae of chronic hyperuricemia.3

We describe a case of finger pad tophi in the context of chronic Raynaud phenomenon and suggest a potential role for the Raynaud phenomenon in the process of tophus formation.

Report of case

A 93-year-old woman with a 6-month history of yellow-white fingertip lesions was referred to our clinic to rule out calcinosis cutis. She had a history of cerebrovascular accident, chronic renal failure, atrial fibrillation, and hypothyroidism. She acknowledged a history of chronic Raynaud phenomenon described as complete and painful whitening of her fingers that occurred mostly in the winter. She denied symptoms of inflammatory arthritis. Medication use included levothyroxine, 25 μg daily, furosemide, 20 mg daily, atenolol, 25 mg daily, hydrochlorothiazide, 37.5 mg daily, and spironolactone, 37.5 mg daily. She had been started on colchicine, 0.6 mg twice daily, 1 month before our assessment for presumptive treatment of either calcinosis cutis or gout.

Blood pressure was 110/80 mm Hg. Dermatologic examination found grouped and distributed white-to-yellow milialike papules measuring 2 to 3mm in diameter on the distal finger pads of the index and long fingers, which were tender to palpation (Fig 1). Examination of the proximal nail folds found a normal capillary pattern. There was no cutaneous sclerosis or tapering of the digits.

Fig 1.

Tophaceous gout. Grouped white-to-yellow papules on the finger pads.

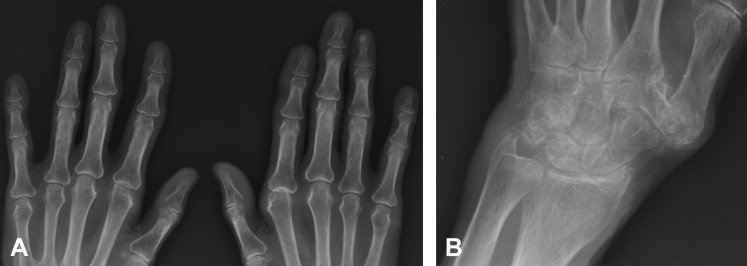

Radiograph of the hands showed periarticular calcifications at both first carpometacarpal joints and adjacent to the ulnar styloid process, evidence of distal osteoarthritis, and soft tissue swelling of the finger pads without digital calcification (Fig 2). Serum creatinine level was 147 μmol/L, estimated glomerular filtration rate was 26 μmol/L, blood urea nitrogen level was 15.6 mmol/L, and serum urate concentration was 695 μmol/L (normal, 140–360). Calcium (2.52 mmol/L) and phosphate (0.9 mmol/L) levels were normal. The presentation was consistent with finger pad tophaceous gout. Diagnosis was confirmed by a skin biopsy (Fig 3).

Fig 2.

Radiograph of the hands. A, Soft tissue swelling along with periarticular calcifications at both 1st carpometacarpal joints. There is no digital calcification. B, Calcification in the region of the triangular cartilage on the left and adjacent to the triquetrum and ulnar styloid process of the left hand.

Fig 3.

Tophaceous gout. Amorphous eosinophilic deposits in dermis show characteristic clefting. Original magnifications: A, ×10 and B, ×20.

Amlodipine, 2.5 mg daily, was started for treatment of Raynaud phenomenon. ULT using allopurinol was initiated.

Discussion

The differential diagnosis of white papules or nodules on the finger pads includes gout, calcinosis cutis, chondrocalcinosis (pseudogout), pyogenic pustules, and oxalosis. Calcinosis cutis involving the digits is noted in patients with systemic sclerosis. These patients have evidence of capillary dropout along the proximal nail folds, sclerosis or tapering of the digits, and pitted scars on the fingertips.4 Patients with pseudogout or oxalosis may rarely present with tumoral calcifications of the digits but not with punctuate white deposits. Any of these conditions would result in radiographic calcifications.

Diagnosis is confirmed by biopsy and histopathologic examination. Gout tophi manifest as a dermal or subcutaneous granulomatous reaction with macrophages and foreign body giant cells.5 Samples must be preserved in alcohol to visualize brown needle-shaped crystals, as crystals will dissolve in formalin leaving amorphous eosinophilic deposits with characteristic clefts (Fig 3).5 Alternatively, needle aspirate of tophi can be examined with polarizing microscopy3; gout crystals will demonstrate negative birefringence. Dual-energy computed tomography represents a newer diagnostic tool with excellent sensitivity for detection of MSU crystal deposits in tophaceous gout6: Compositions of tissues are determined by analyzing the difference in attenuation of materials simultaneously exposed to 2 different x-ray spectra, allowing the direct identification and visualization of MSU crystals. Pertinent investigations include radiography (peri- or intra-articular soft tissue masses and/or erosions7), serum uric acid (hyperuricemia), blood urea nitrogen, serum creatinine, and estimated glomerular filtration rate (renal dysfunction2).

Tophaceous gout is uncommon in patients with established gout and is particularly rare in the absence of prior acute gouty arthritis.3 Retrospective studies show a progressive decline in tophi in newly diagnosed gout despite a steady number of gout diagnoses.7 There are less than 20 reported cases of finger pad tophi in the dermatologic and rheumatologic literature (Table I),8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13 suggesting finger pad tophi are unusual. However, 30.5% of patients with chronic tophaceous gout had finger pad tophi on prospective examination.2 Thus, finger pad tophi may be underreported because of lack of recognition rather than low prevalence. The typical clinical presentation of finger pad tophaceous gout is in an elderly patient with renal dysfunction taking diuretics.3

Table I.

Summary of published finger pad tophi cases.

| Case | Reference | Patient age, sex | UAL (μmol/L) | SCr (μmol/L) | Diuretic |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Shmerling et al3 | 81, F | 773.24 | 159.12 | Furosemide |

| 2 | Shmerling et al3 | 80, F | 493.6 | 185.64 | HCTZ |

| 3 | Shmerling et al3 | 76, F | 481.7 | 150.28 | HCTZ |

| 4 | Shmerling et al3 | 86, F | 642.3 | 176.8 | HCTZ |

| 5 | Chopra et al8 | 57, M | 606.7 | 309.47 | Furosemide |

| 6 | Zheng and Han9 | 62, M | 513.31 | 103.45 | None |

| 7 | Eng et al10 | 64, M | 430 | 80 | Furosemide, spironolactone |

| 8 | Kurita et al15 | 37, F | 678.07 | 424.42 | Furosemide |

| 9 | Hollingworth et al11 | 69, M | 590 | N/R | N/R |

| 10 | Hollingworth et al11 | 70, M | 550 | N/R | Furosemide |

| 11 | Hollingworth et al11 | 75, M | 510 | N/R | Bendrofluazide |

| 12 | Hollingworth et al11 | 72, F | 580 | N/R | N/R |

| 13 | Fam et al12 | 34, M | 550 | 384 | Yes (type not specified) |

| 14 | Fam et al12 | 73, M | 601 | 134 | Yes (type not specified) |

| 15 | Fam et al12 | 66, M | 531 | 282 | Yes (type not specified) |

| 16 | Fam et al12 | 77, F | 496 | 186 | Yes (type not specified) |

| 17 | Richette et al13 | 56, F | 600 | N/R | N/R |

Note. Finger pad tophi have most commonly been reported in elderly patients (average age, 66.8 years) with renal dysfunction (average serum creatinine, 214.6 μmol/L), on diuretics (≥76.5% of cases), and with hyperuricemia (average uric acid level, 566.29 μmol/L).

F, Female; HCTZ, hydrochlorothiazide; M, male; N/R, not reported; SCr, serum creatinine; UAL, uric acid level.

Low tissue temperature may play a role in tophus development.3, 14 This finding may explain why tophi develop in colder areas such as the helix of the ear, the metatarsophalangeal joints,3 and the finger pads. Interestingly, finger pad gout has been described in a patient with concomitant systemic lupus erythematosus,15 a condition associated with Raynaud phenomenon. We propose a possible role of Raynaud phenomenon as a contributor to the development of finger pad tophi.

Tophi are an indication for ULT initiation, with a goal of lowering serum urate to less than 6 mg/dL.16 First-line agents include xanthine oxidase inhibitors such as allopurinol or febuxostat. Uricosuric therapy such as probenecid may be added if serum urate target is not achieved or used as monotherapy if xanthine oxidase inhibitors are not tolerated. Pegloticase is available for severe gout refractory or intolerant to appropriately dosed ULT.16 Additional recommendations include a low-purine diet, discontinuation of nonessential medications contributing to hyperuricemia, and lifestyle recommendations such as alcohol abstinence, exercise, hydration, and smoking cessation.16

This case highlights the need to consider tophaceous gout in patients with fingertip papules or nodules. Recognition of finger pad tophi as a presenting feature of hyperuricemia facilitates prompt initiation of ULT,3 limiting future gouty arthritic attacks and other sequelae including hypertension, insulin resistance/diabetes, cardiovascular disorders, and nephropathy.14

Footnotes

Funding sources: None.

Conflicts of interest: None decarled.

References

- 1.Falasca G.F. Metabolic diseases: gout. Clin Dermatol. 2006;24(6):498–508. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2006.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Holland N.W., Jost D., Beutler A. Finger pad tophi in gout. J Rheumatol. 1996;23:690–692. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shmerling R.H., Stern S.H., Gravallese E.M. Tophaceous deposition in the finger pads without gouty arthritis. Arch Intern Med. 1988;148:1830–1832. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hinchcliff M., Varga J. Systemic sclerosis/scleroderma: a treatable multisystem disease. Am Fam Physician. 2008;78:961–968. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnston R.B. Cutaneous Deposits. In: Johnston R.B., editor. Weedon's Skin Pathology Essentials. 2nd ed. Elsevier Ltd; London: 2017. pp. 279–298. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baer A.N., Kurano T., Thakur U.J. Dual-energy computed tomography has limited sensitivity for non-tophaceous gout: a comparison study with tophaceous gout. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2016;17:1. doi: 10.1186/s12891-016-0943-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.O'Duffy J.D., Hunder G.G., Kelly P.J. Decreasing prevalence of tophaceous gout. Mayo Clin Proc. 1975;50:227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chopra K.F., Schneiderman P., Grossman M.E. Finger pad tophi. Cutis. 1999;64:233–236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zheng L.Q., Han X.C. Cream-yellow and firm nodule in finger pad. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2012;78:522. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.98107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eng A.M., Schmidt K., Bansal V. Finger pad deposits. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:1438. doi: 10.1001/archderm.130.11.1435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hollingworth P., Scott J.T., Burry H.C. Nonarticular gout: hyperuricemia and tophus formation without gouty arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 1983;26:98–101. doi: 10.1002/art.1780260117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fam A.G., Assaad D. Intradermal urate tophi. J Rheumatol. 1997;24:1126–1131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Richette P., Bardin T. Successful treatment with rasburicase of a tophaceous gout in a patient allergic to allopurinol. Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol. 2006;2:338–342. doi: 10.1038/ncprheum0214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Choi H.K., Mount D.B., Reginato A.M. Pathogenesis of gout. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143:499–516. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-143-7-200510040-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kurita Y., Tsuboi R., Numata K. A case of multiple urate deposition,without gouty attacks, in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus. Cutis. 1989;43:273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khanna D., Fitzgerald J.D., Khanna P.P. 2012 American College of Rheumatology guidelines for management of gout. Part 1: systematic nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic therapeutic approaches to hyperuricemia. Arthritis Care Res. 2012;64:1431–1446. doi: 10.1002/acr.21772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]