This work uses a new approach that directly extracts important biophysical parameters from alpha function-evoked synaptic potentials. Two of these parameters are the cell membrane capacitance (Cm) and rate at any time point of the synaptic waveform. The use of such methodology shows that cocaine sensitization reduces Cm and increases the speed of synaptic signaling. Paradoxically, although synaptic potentials show a faster decay under cocaine their temporal summation is substantially elevated.

Keywords: capacitance, cocaine, EPSP, h-current, temporal summation

Abstract

The progressive escalation of psychomotor responses that results from repeated cocaine administration is termed sensitization. This phenomenon alters the intrinsic properties of dopamine (DA) neurons from the ventral tegmental area (VTA), leading to enhanced dopaminergic transmission in the mesocorticolimbic network. The mechanisms underlying this augmented excitation are nonetheless poorly understood. DA neurons display the hyperpolarization-activated, nonselective cation current, dubbed Ih. We recently demonstrated that Ih and membrane capacitance are substantially reduced in VTA DA cells from cocaine-sensitized rats. The present study shows that 7 days of cocaine withdrawal did not normalize Ih and capacitance. In cells from cocaine-sensitized animals, the amplitude of excitatory synaptic potentials, at −70 mV, was ∼39% larger in contrast to controls. Raise and decay phases of the synaptic signal were faster under cocaine, a result associated with a reduced membrane time constant. Synaptic summation was paradoxically elevated by cocaine exposure, as it consisted of a significantly reduced summation indexed but a considerably increased depolarization. These effects are at least a consequence of the reduced capacitance. Ih attenuation is unlikely to explain such observations, since at −70 mV, no statistical differences exist in Ih or input resistance. The neuronal shrinkage associated with a diminished capacitance may help to understand two fundamental elements of drug addiction: incentive sensitization and negative emotional states. A reduced cell size may lead to substantial enhancement of cue-triggered bursting, which underlies drug craving and reward anticipation, whereas it could also result in DA depletion, as smaller neurons might express low levels of tyrosine hydroxylase.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY This work uses a new approach that directly extracts important biophysical parameters from alpha function-evoked synaptic potentials. Two of these parameters are the cell membrane capacitance (Cm) and rate at any time point of the synaptic waveform. The use of such methodology shows that cocaine sensitization reduces Cm and increases the speed of synaptic signaling. Paradoxically, although synaptic potentials show a faster decay under cocaine their temporal summation is substantially elevated.

repeated cocaine exposure results in a progressive enhancement in the drug's locomotor effects. This phenomenon, termed sensitization, forms part of the basic pathological mechanisms involved in drug addiction and is thought to reflect adaptations in neural circuits that determine the motivational value of external cues (Robinson and Berridge 2003). The most notable feature of sensitization is that it can persist for months to years after drug treatment is discontinued (Steketee and Kalivas, 2011).

Chronic cocaine use is associated with dopamine (DA) depletion, which may underlie drug craving and relapse following periods of abstinence (Dackis and Gold 1985; Shalev et al. 2002; Willuhn et al. 2014). Intense behavioral therapies designed to manage cocaine dependence may therefore result in longer abstinence periods when combined with the DA precursor levodopa (Schmitz et al. 2008). Advances in our understanding of sensitization are likely to improve the efficacy of such DA-based therapeutic strategies. Sensitization experiments, for example, revealed a diminished glutamate neurotransmission in the nucleus accumbens, which led to studies demonstrating that restoration of glutamate levels in this brain region could minimize relapse in animal models and humans (Baker et al. 2003; Knackstedt et al. 2009, 2010; Mardikian et al. 2007; Sari et al. 2009; Zhou and Kalivas 2008). Consequently, the interpretation of the underlying neurobiology of sensitization may prove to be beneficial for the treatment of addiction.

Mesencephalic DA projections from the ventral tegmental area (VTA) to the nucleus accumbens and other limbic structures play a central role in the development of addiction to cocaine and other drugs of abuse (Wolf et al. 2004). One of the electrophysiological properties that characterize these neurons is the presence of the hyperpolarization-activated, nonselective cation current, named Ih or h-current. A major task of Ih in non-DA nerve cells is to dampen the summation of trains of synaptic inputs (Magee 1998; Stuart and Spruston 1998; Williams and Stuart 2003). Such a role of Ih in DA cells has recently been confirmed in mice (Masi et al. 2015) and rats (Engel and Seutin 2015). Therefore, in DA cells, Ih inhibition is likely to enhance the burst signal (Mrejeru et al. 2011).

Frequent exposure to drugs of abuse results in significant biophysical and morphological changes of midbrain DA cells. For instance, repeated ethanol administration is known to attenuate Ih amplitude severely in VTA DA neurons of rats and mice (Hopf et al. 2007; Okamoto et al. 2006). Our laboratory has recently reported that in the VTA of cocaine-sensitized rats, dopaminergic h-current and cell membrane capacitance (Cm) are dramatically reduced, indicating this latter finding of a diminished neuronal size (Arencibia-Albite et al. 2012). Likewise, chronic morphine consumption also induces a significant reduction in the size of these cells (Russo et al. 2007), as well as prolonged cannabinoid administration (Spiga et al. 2010). These neuroadaptations are remarkable; however, their connection to the excitability of DA cells is currently unknown.

The present study shows that the cocaine-induced Cm and h-current reduction persist after 7 days of drug withdrawal. These adaptations are associated with a significant increment in the dynamics and summation of excitatory synaptic potentials. Therefore, cocaine sensitization results in the augmentation of VTA DA neuron excitation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals and sensitization protocol.

Procedures involving experimental animals were performed according to the U.S. Public Health Service publication, Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, and were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Puerto Rico Medical Sciences Campus.

All experiments were performed with male Sprague-Dawley rats (42–58 days postnatal). Animals were housed in pairs and maintained at constant temperature and humidity with a 12-h light/dark cycle. Water and food was provided at all times.

Motor activity was analyzed with VersaMax (AccuScan Instruments, Omnitech Electronics, Columbus, OH). Animal cages are made from clear plastic (42 × 42 × 30 cm), with 16 evenly spaced (2.5 cm) infrared beams, set at 2 cm from the floor. Horizontal locomotion was defined as the sequential breaking of different beams. Data were displayed and stored in a personal computer using the VersaMax software VersaDat. Before the commencement of all experiments (day 0), the animals were adapted to cages and injection treatments. On day 1, animals were habituated for 15 min, after which, animals were treated with 15 mg/kg ip cocaine (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) or isovolumetric saline (0.9%) injections. Subsequent to injections, locomotion activity was measured for 1 h, once/day for 7 days. At the end of each recording session, animals were returned to their home cages.

Electrophysiology.

Brain slices (220 μm) were obtained from male Sprague-Dawley rats, as formerly described (Arencibia-Albite et al. 2007). Whole-cell recordings were done in visually identified VTA neurons using an infrared microscope equipped with differential interference contrast (BX51WI; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). Putative DA neurons were identified by the presence of Ih and were located lateral to the fasciculus retroflexus and medial to the medial terminal nucleus of the accessory optic tract (Paxinos and Watson 2009). Every cell that expresses tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) also coexpresses Ih, and so every VTA DA cell displays the h-conductance (or Ih) (Margolis et al. 2006a, b). The presence of Ih, in contrast, does not guarantee that recordings are being made in DA neurons (Margolis et al. 2006b). However, we recorded medial to the medial terminal nucleus, where Ih and TH are colocalized in ∼75% of cells (Hopf et al. 2007). Hence, the contribution of non-DA cells to the data shown here is relatively minor. Patch micropipettes (borosilicate glass: outside diameter, 1.5 mm; inside diameter, 1.0 mm; World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL) had a resistance of 3–5 MΩ when filled with internal recording solution containing the following (in mM): 115 KCH3SO4, 20 KCl, 1.5 MgCl2, 5 HEPES, 1 EGTA, 2 ATP, 0.2 GTP, 10 creatine phosphate, pH = 7.25, 290 mosM. (Na) GTP, (Mg) ATP, and (Na) creatine phosphate were added fresh daily. Artificial cerebrospinal fluid contained the following (in mM): 127 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 25 NaHCO3, 2 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 25 D(+)-glucose, bubbled with 95% O2-5% CO2 at 35°C. Data were collected through an Axopatch 200B amplifier (Axon Instruments; Molecular Devices, Sunnydale, CA), digitized at 5 kHz, filtered at 1 kHz, and stored in a personal computer using pCLAMP 9 (Axon Instruments; Molecular Devices). Series resistance was monitored during the entire recording, and experiments in which the series resistance was >30 MΩ were discarded. Whole-cell Ih nonstationary fluctuations, Ih voltage dependence, DA cell spontaneous activity, and Cm were analyzed, as previously described (Arencibia-Albite et al. 2012). Alpha-excitatory postsynaptic currents (αEPSCs) were generated by the following function: .

In this expression, the value of α indicates the time (t) to reach maximum current (Imax), since αEPSC (α) = Imax. The measured response evoked by the αEPSC is termed the αEPSP. For all recordings, α was set to t = 5 ms, whereas Imax = 50 pA. Thus each αEPSC always injects the same amount of electric charge, . The αEPSP waveform modeled the following equation (see derivation below)

| (1) |

In this expression, V represents the deviation of the membrane potential (Vm) with respect to the holding level (Vhold); i.e., V = Vm − Vhold, and RN is the neuron's input resistance. Integration of Eq. 1 gives

| (2) |

The αEPSP rate (dV/dt) was analyzed using the first derivative of Eq. 2

| (3) |

The temporal summation was quantified by the temporal summation index (TSI)

That is, TSI represents the relative change of the fifth αEPSP (αEPSP5) with respect to the first αEPSP (αEPSP1). The mean or average membrane depolarization (ΔVavg) that corresponds to a cell expressing a TSI > 0 is defined as

where ΔVm is the change in Vm relative to the Vhold, and T represents the elapsed time between the peak values of αEPSP1 and αEPSP5.

Derivation of Eq. 1.

For small deviations in the Vhold (e.g., V ≤ 5), the nonlinear membrane elements are well approximated by linear ones (Rall and Agmon-Snir 1998). Thus in the derivation that follows, resistances are ohmic.

The somatically applied αEPSC(t) will spread into the soma, dendrites, and axon, so

Here, CS is the soma capacitance; RS is the soma input resistance; V(t), VD,j(0,t), and VA(0,t) are the somatic, dendritic, and axonic deviations from resting level, respectively; and ri,j or ri,A represents the intracellular resistance/unit of length of the jth dendrite or axon, respectively. At the soma-dendrite and soma-axon boundaries, we have the conditions (Rall and Agmon-Snir 1998)

where RN,j is the input resistance of the jth dendrite, whereas RA is the axon input resistance. With the combination of the previous equations

where represents the neuron's input conductance at the particular holding level.

If the αEPSC(t) current density is nearly uniform across the soma, dendrites, and axon membranes, then we can replace CS for Cm, and thus we can write

Consequently, under conditions of nearly homogeneous αEPSC(t) current spread, the initial value problem that approximates the αEPSP temporal development is Eq. 1.

In DA cells, this assumption seems reasonable for two reasons. First, in dopaminergic cells, the EPSP waveform attenuation that results from the dendrosomatic propagation of the synaptic signal is barely discernible (Engel and Seutin 2015). Second, in computational models of these neurons that incorporate realistic morphology, the back-propagating action potential also reaches distal dendrites with minimal decay in amplitude (Vetter et al. 2001). Therefore, Eq. 1 is a tolerable approximation of the subthreshold Vm time course for the purpose of this study.

Drugs.

All drugs were purchased from Tocris Bioscience (Ellisville, MO) or Sigma and were prepared as needed on the day of experimentation.

Statistics.

Summary data are presented as means ± SE, and statistical analysis was made with Prism (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). Locomotor sensitization procedures were analyzed using one-way ANOVA, followed by Newman-Keuls multiple comparison test or unpaired t-tests as appropriate. Electrophysiological experiments were analyzed using unpaired t-tests. Results were considered significant if P < 0.05.

RESULTS

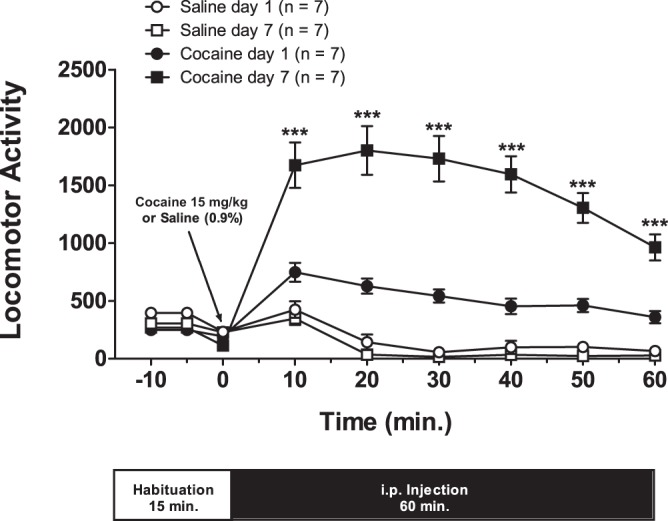

This work reports effects of cocaine locomotor sensitization as induced by a single daily injection (15 mg/kg ip) for 7 consecutive days. After 7 days of withdrawal, one or two cells were analyzed per rat with whole-cell recordings in midbrain slices. All cocaine-treated animals used in this study were successfully sensitized (see Fig. 1 for details).

Fig. 1.

Seven days of cocaine administration leads to the development of locomotor sensitization. All cocaine-treated rats used in this study expressed locomotor sensitization after a 7-day intraperitoneal injection (15 mg/kg) protocol. For each day, rats were first habituated to recording cages for 15 min, and data (means ± SE) were sampled every 5 min. Immediately after the conclusion of the habituation period, animals were injected either with saline solution (0.9%) or cocaine, and motor activity was recorded at 10 min intervals for 60 min. The motor activity measured at each time interval equals the sum of horizontal plus stereotype activities. Asterisks are for the comparison between days 1 and 7 of cocaine-treated rats: one-way ANOVA: F(3,24) = 79.14, ***P < 0.0001; post hoc comparison: Newman-Keuls multiple comparison test.

The cocaine-evoked reduction in Ih and Cm persists after 7 days of drug withdrawal.

In putative VTA DA neurons of rats, we previously reported that 24 h after the last cocaine injection of a 7-day-long locomotor-sensitization protocol, Ih amplitude and Cm were significantly diminished (Arencibia-Albite et al. 2012). Several of the early drug-induced cellular events that led to the acquisition of sensitization disappeared ∼1 wk after ending repeated drug treatment (Ackerman and White 1990; Henry et al. 1989; Kalivas and Duffy 1993). Consequently, it is natural to ask if 7 days of cocaine withdrawal are able to restore the normal values of h-current and capacitance in putative VTA DA neurons of cocaine-sensitized rats.

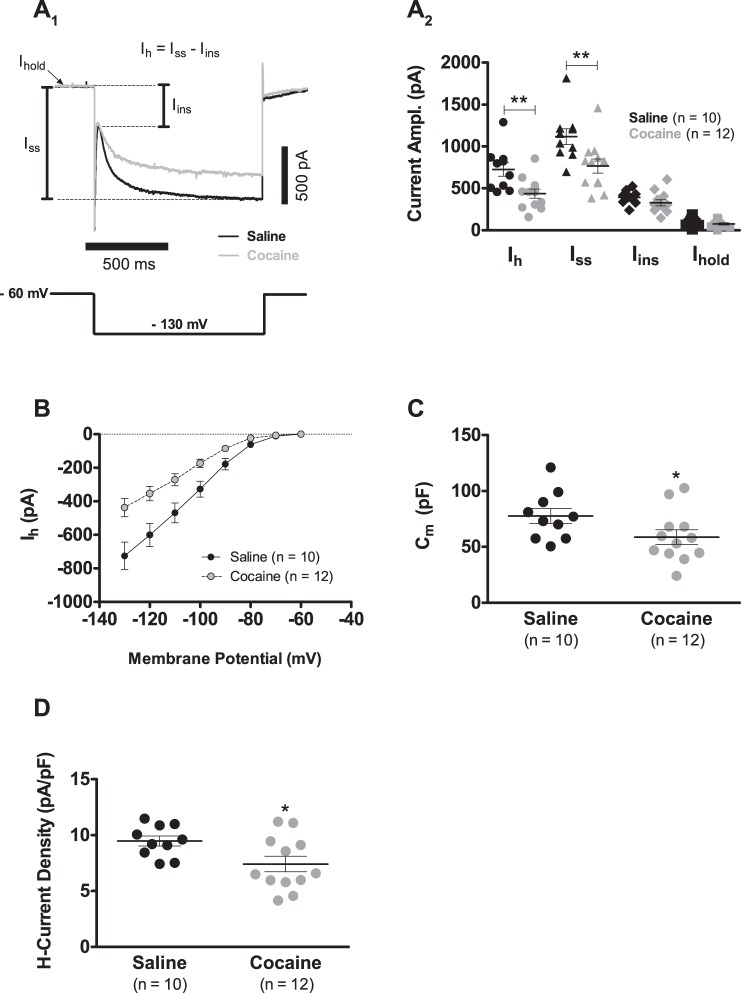

The present study shows that after 7 days of withdrawal, Ih amplitude and Cm continue to be significantly reduced. At day 7, for instance, when cells from cocaine-sensitized rats were voltage clamped at −130 mV, putative DA neurons presented an ∼40% reduction in Ih amplitude, in contrast to controls (Fig. 2, A1 and A2; 725.1 ± 81.2 pA, n = 10, saline vs. 437.2 ± 54.4 pA, n = 12, cocaine; P < 0.01). In Fig. 2A1, Ih amplitude is defined as the difference between the steady-state current (Iss) and the instantaneous current (Iins): Ih = Iss − Iins. Thus Ih amplitude reduction occurs by specific alterations in the magnitude of Iss and Iins. Experiments indicate that Iins was not affected (Fig. 2A2; 391.8 ± 25.3 pA, n = 10, saline vs. 328.5 ± 35.8 pA, n = 12, cocaine; P > 0.05), whereas Iss was significantly reduced (Fig. 2A2; 1,116.9 ± 94.0 pA, n = 10, saline vs. 765.8 ± 84.4 pA, n = 12, cocaine; P < 0.01). In addition, the holding current at −60 mV was similar between groups (Fig. 2A2; 92.2 ± 14.2 pA, n = 10, saline vs. 76.4 ± 12.5 pA, n = 12, cocaine; P > 0.05). Furthermore, Ih inward rectification still clearly diminished after 7 days of cocaine withdrawal (Fig. 2B). The biophysical mechanism explaining the above-described Ih attenuation was, as formerly reported (Arencibia-Albite et al. 2012), a decrease in the number of voltage-gated channels that carry the Ih (h-channels), with no change in single-channel conductance, open probability, and voltage dependence (data not shown). In the case of capacitance, a significant difference was still seen between groups of putative DA neurons with that of cocaine-injected animals being ∼24% smaller than that of saline-treated rats (Fig. 2C; 77.6 ± 6.7 pF, n = 10, saline vs. 58.7 ± 6.5 pF, n = 12, cocaine; P < 0.05). The combined reductions in capacitance and Ih produced a significant diminution in Ih current density in cocaine-exposed cells compared with saline control cells (Fig. 2D; 9.4 ± 0.4 pA/pF, n = 10, saline vs. 7.4 ± 0.7 pA/pF, n = 12, cocaine; P < 0.05). Finally, no significant differences were found in the spontaneous firing frequency, action potential waveform, and rebound spiking after the 7 days of drug withdrawal (data not shown). As a result, following the establishment of locomotor sensitization, cocaine withdrawal does not appear to reverse the drug-induced alterations in h-current amplitude and Cm.

Fig. 2.

The cocaine-evoked reduction in Ih and Cm persists after 7 days of drug withdrawal. A1: representative voltage-clamp traces showing the effects of cocaine sensitization onto Ih of VTA DA neurons following 7 days of drug withdrawal. As seen in the figure, Ih amplitude is defined as the difference between the steady-state current (Iss) and the instantaneous current (Iins). Ihold, holding current. A2: summary graph of the records presented in A1 showing that Ih amplitude reduction persists after 7 days of cocaine withdrawal. The direction of all depicted current amplitudes (Ampl.) is inward. B: Ih current inward rectification continues to be clearly depressed subsequent to 7 days of cocaine withdrawal. C: DA Cm continues to be significantly reduced after 7 days of cocaine withdrawal. Cm was determined in the Ih experiments summarized in B using the voltage step from −60 to −70 mV. The first 40 ms of the initial capacitive transient was fitted with a sum of 2 exponential functions, and the time constant of the fastest exponential term (τfast) was used to estimate Cm, according to the following expression: Cm = τfast(1/RS + 1/RN), where RS is the series resistance, and RN is the input resistance. D: summary graph illustrating that Ih current density is significantly reduced, 7 days after ending a cocaine-sensitization injection protocol. Current density was computed as the ratio of maximal Ih current (Vhold = −130 mV) to Cm. In summary plots A2, C, and D, horizontal black segments with error bars represent means ± SE; unpaired t-test: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

Analysis of the effects of cocaine sensitization on putative VTA DA cell subthreshold synaptic potentials.

Putative VTA DA cell subthreshold excitatory potentials were analyzed through the injection of a theoretical representation of a synaptic input: the αEPSC (see materials and methods). Such current was applied either as a single pulse or train of five pulses. The use of the αEPSC removes unwanted contributions of presynaptic mechanisms that may obstruct the analysis of how postsynaptic cell properties affect the amplitude and dynamics of the synaptic signal (Brager and Johnston 2007; Lewis et al. 2011). Inhibitory postsynaptic potentials were not analyzed as part of this study.

αEPSCs were always injected into the soma of putative VTA DA neurons of cocaine-sensitized rats or saline-treated animals after both groups had completed a 7-day withdrawal period from their corresponding treatment protocols.

The αEPSPs of cocaine-sensitized rats are larger compared with those of saline controls.

By definition, Cm is the quotient of the separated electric charge Q across the membrane to the cell's potential (Vm) necessary to hold such charge; i.e., Cm = Q/Vm. This signifies that Cm and Vm are inversely related variables. It is possible, therefore, that in putative VTA DA neurons, the cocaine-evoked capacitance reduction may result in synaptic potentials of greater amplitude when cells are probed with a fixed αEPSC input. This matter is investigated next.

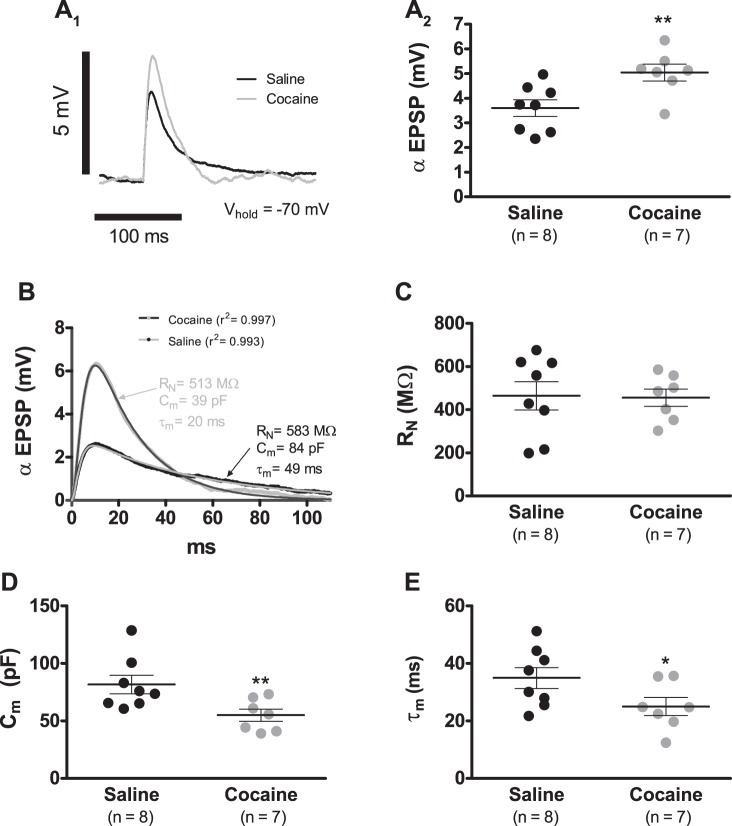

On average, when cells were current clamped at −70 mV, cocaine sensitization resulted in an ∼39% increase in the αEPSP amplitude (Fig. 3, A1 and A2; 3.6 ± 0.3 mV, n = 8, saline vs. 5.0 ± 0.3 mV, n = 7, cocaine; P < 0.01). As shown in materials and methods, in all tested cells, the αEPSC always injects the same amount of ionic charge (∼680 fC), and thus the shape of the αEPSP trace is only a reflection of the underlying membrane biophysics that drives the recorded response. To expose these hidden membrane characteristics, it is necessary to link explicitly the αEPSP voltage curve to the cell's properties that affect its amplitude and dynamics: the cell RN, Cm, and membrane time constant (τ). A heuristic approach to this issue is to use a mathematical model that provides a precise account of the αEPSP time course with only a few empirically tractable unknown parameters. Accordingly, Eq. 2 might satisfactorily account for the αEPSP waveform (see materials and methods).

Fig. 3.

Cocaine sensitization augments the αEPSP amplitude. A1: representative αEPSP recordings of VTA DA neurons from cocaine (gray trace)- and saline (black trace)-treated animals after a 7-day withdrawal period. αEPSPs were generated by the somatic injection of αEPSCs with α = 5 ms and Imax = 50 pA. Each record shown in the figure is the average of 10 consecutive sweeps. A2: summary plot showing that cocaine sensitization leads to a significant increase in αEPSP amplitude. B: examples of least square fits of Eq. 2 to αEPSP recordings of cells from cocaine (gray trace with dark-gray-fitted curve)- and saline (black trace with gray-fitted curve)-treated animals. The use of the fitted coefficients allowed the estimation of RN, Cm, and τ (τm; values for each shown in gray for cocaine and black for saline). C: summary graph showing that cocaine sensitization did not alter RN at −70 mV. D: summary graph showing that cocaine sensitization resulted in a significant reduction in Cm. E: summary graph showing that cocaine sensitization resulted in a significant reduction in τm. In summary graphs A2, C, D, and E, horizontal black segments with error bars represent means ± SE; unpaired t-test: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

Equation 2 was least square fitted to all αEPSP traces, and the results were remarkable. For example, the mean value for the coefficient of determination was 0.992 ± 0.003 (n = 7) in the cocaine-sensitized animals, whereas it was 0.992 ± 0.002 (n = 8) in saline controls (P > 0.05; Fig. 3B). By applying this curve-fitting procedure to αEPSP recordings, we estimated RN, Cm, and τ for each probed neuron. For RN, this analysis showed no significant differences between groups (Fig. 3C; 464.1 ± 65.4 MΩ, n = 8, saline vs. 455.4 ± 40.1 MΩ, n = 7, cocaine; P > 0.05). In the case of capacitance, nonetheless, neurons from cocaine-treated animals manifested a mean value that was ∼33% smaller than the one observed in cells from saline-injected rats (Fig. 3D; 81.2 ± 8.0 pF, n = 8, saline vs. 55.0 ± 5.2 pF, n = 7, cocaine; P < 0.01). Likewise, τ was ∼29% smaller under cocaine treatment than in saline controls (Fig. 3E; 34.9 ± 3.6 ms, n = 8, saline vs. 25.0 ± 3.1 ms, n = 7, cocaine; P < 0.05). As a result, it appears that the increased αEPSP amplitude is at least a consequence of the reduced Cm.

The αEPSPs of cocaine-sensitized rats express a faster rate of temporal development than that of saline controls.

In general and exemplified by Eq. 3, Cm and dV/dt are inversely related quantities. Consequently, the cocaine-evoked reduction in Cm could result in the augmentation of the αEPSP rate of temporal development. Before presenting the results that analyze this hypothesis, we introduce some definitions that will facilitate the interpretation of the shown data.

Each αEPSP can be divided into two distinct phases: a depolarizing upstroke that peaks rapidly (dV/dt ≥ 0 for all t in this period) and the slow, repolarizing decay that follows immediately after maximal amplitude is reached (dV/dt ≤ 0 for all t in this period). At t = 0 and at peak amplitude, dV/dt = 0, which implies that at some time point within the depolarizing phase, the absolute value of dV/dt has attained a maximum size that we termed maximal depolarization rate (MDR). Similarly, at the start and end of the repolarizing phase, dV/dt = 0, and thus at some point during this time interval, the absolute value of dV/dt has also achieved a maximum that we named maximal repolarization rate (MRR).

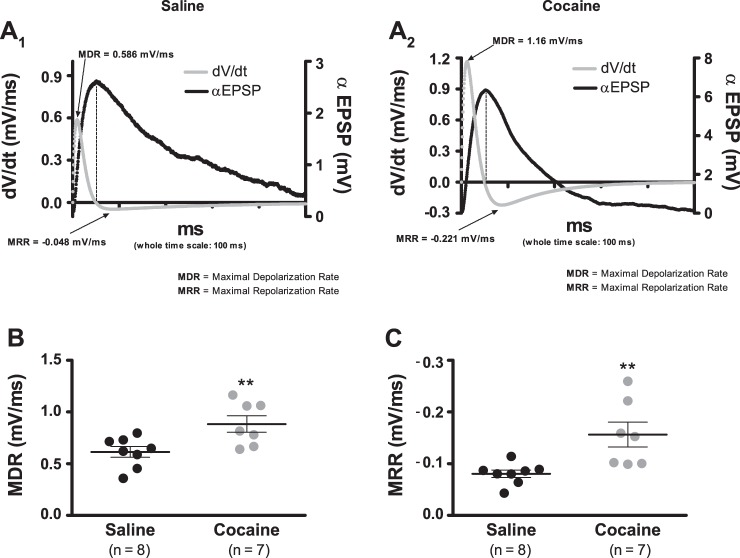

In view of the evidence that shows that the coefficients of determination for all fits of Eq. 2 were, on average, 0.992, differences in rate were analyzed by using the first derivative of this equation (Eq. 3). Notice that Eq. 3 provides a precise calculation of the whole time course of the dV/dt, and thus it also allows an accurate approximation of the MDR and MRR that corresponds to the αEPSP trace under examination (Fig. 4, A1 and A2). Figure 4B shows that cells from cocaine-sensitized animals expressed an average MDR that was ∼44% greater compared with cells from saline controls (0.614 ± 0.052 mV/ms, n = 8, saline vs. 0.884 ± 0.079 mV/ms, n = 7, cocaine; P < 0.01). Similarly, Fig. 4C shows that under sensitization, the mean MRR was ∼95% larger, as contrasted to the saline reference (0.080 ± 0.007 mV/ms, n = 8, saline vs. 0.156 ± 0.024 mV/ms, n = 7, cocaine; P < 0.01). Consequently, the increased dV/dt is at least caused by the reduced Cm.

Fig. 4.

Cocaine sensitization augments the αEPSP rate (dV/dt). A1 and A2: representative examples illustrating the calculations of the temporal development of the dV/dt. Computations were performed with Eq. 3. Each αEPSP used in this analysis is the average of 10 consecutive sweeps. Dashed lines indicate that the peak αEPSP value happens exactly when dV/dt = 0. B: summary plot showing that cocaine sensitization leads to a significant augmentation of the MDR. C: summary plot showing that cocaine sensitization leads to a significant augmentation of the MRR. In summary plots B and C, horizontal black segments with error bars represent means ± SE; unpaired t-test: **P < 0.01.

Cocaine sensitization increases temporal summation at depolarized potentials.

So far, experimental measurements show that cocaine sensitization augments the αEPSP amplitude and dV/dt but leaves unanswered how these same alterations shape the process of synaptic integration. This question is addressed next.

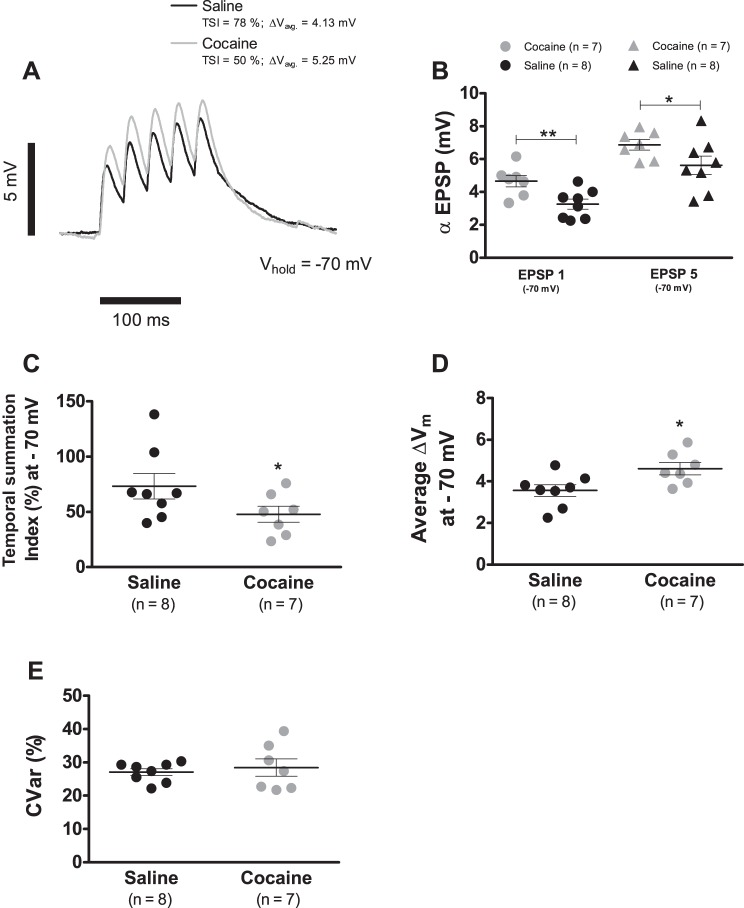

To analyze the effects of cocaine sensitization on synaptic integration, a 33-Hz train of 5αEPSCs (α = 5 ms; Imax = 50 pA) was injected into the soma of putative VTA DA neurons. The temporal summation evoked by this input was quantified by the TSI (see materials and methods). The TSI is a standard measurement for quantifying the process of temporal summation and is typically, positively correlated with membrane depolarization; i.e., a large TSI indicates a large depolarization (Angelo et al. 2007; Brager and Johnston 2007; Carr et al. 2007; Lewis et al. 2011).

Figure 5A shows examples of temporal summation recordings performed at −70 mV. The mean value of αEPSP1 in cells from saline-treated rats was 3.3 ± 0.3 mV (n = 8), whereas that of the cocaine group was 4.7 ± 0.3 mV (n = 7; P < 0.01; Fig. 5B). Similarly, the αEPSP5 was 5.6 ± 0.6 mV (n = 8) for saline controls and 6.9 ± 0.3 mV (n = 7; P < 0.05; Fig. 5B) in the cells from cocaine-injected animals. These findings resulted in a TSI of 73.2 ± 11.5% (n = 8) in control neurons but just of 47.8 ± 7.2% (n = 7; P < 0.05; Fig. 5C) in cells of cocaine-administered rats. According to the prevalent interpretation of the TSI (Angelo et al. 2007; Brager and Johnston 2007; Carr et al. 2007; Lewis et al. 2011), this cocaine-evoked reduction in the summation index is expected to express a diminished depolarization. However, the mean depolarization (see materials and methods) was significantly larger under cocaine than in the saline case (Fig. 5D; 3.6 ± 0.3 mV, n = 8, saline vs. 4.6 ± 0.3 mV, n = 7, cocaine; P < 0.05).

Fig. 5.

Cocaine sensitization increases temporal summation at −70 mV. A: representative temporal summation recordings evoked by the somatic injection of a train of 5αEPSCs (α = 5 ms; Ipeak = 50 pA) at 33 Hz (period: 30 ms) of VTA DA neurons from cocaine (gray trace)- and saline (black trace)-treated animals after a 7-day withdrawal period. Each record is the average of 10 consecutive sweeps. B: summary plot showing that cocaine sensitization leads to a significant augmentation of the first and fifth αEPSP at −70 mV. C: summary plot showing that cocaine sensitization leads to a significant reduction of the TSI at −70 mV. D: summary plot showing that cocaine sensitization leads to a significant augmentation of the mean depolarization endured during temporal summation at −70 mV. E: summary plot showing that cocaine sensitization did not alter the variability around the mean depolarization measure in D. In summary plots B, C, D, and E, horizontal black segments with error bars represent means ± SE; unpaired t-test: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. CVar, coefficient of variation.

Finally, the variability around the mean depolarization was not affected by cocaine exposure [Fig. 5E; coefficient of variation (CVar) = 27.0 ± 1.0%, n = 8, saline vs. CVar = 28.4 ± 2.6%, n = 7, cocaine; P > 0.05]. Therefore, it can be concluded that cocaine sensitization increases temporal summation at −70 mV, even when TSI measurements suggest the opposite. The cocaine-evoked Ih reduction is unlikely to explain the elevated synaptic summation, as in our whole-cell recordings, the h-conductance is not significantly active at −70 mV, plus no statistical difference exists in Ih amplitude at this potential between cocaine-exposed cells and controls (see Fig. 2B).

Cocaine sensitization increases temporal summation at hyperpolarized potentials.

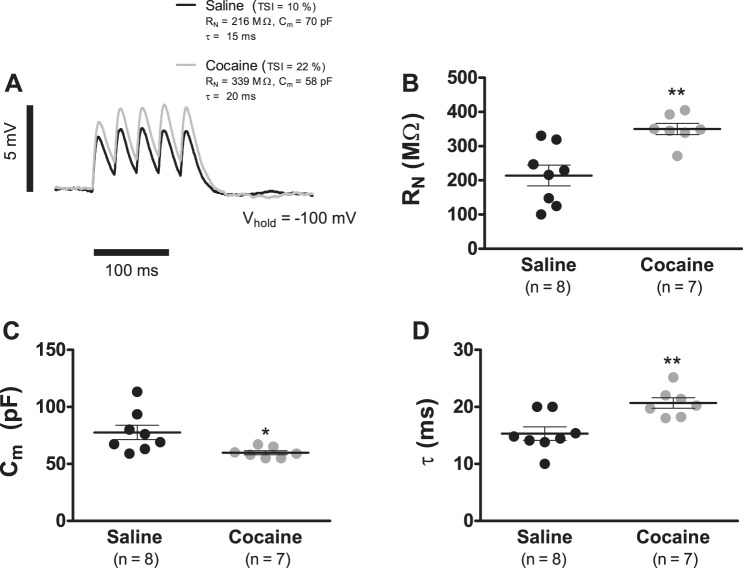

In our experimental preparation, Ih becomes a significant proportion of the membrane conductance only for potentials hyperpolarized to −70 mV (see Fig. 2B). Therefore, the ∼40% cocaine-induced Ih reduction increases the likelihood that during considerable hyperpolarization (Vm ≪ −70 mV), the τ of putative VTA DA neurons will be augmented. To determine if the cocaine-induced Ih reduction resulted in an increased τ during significant hyperpolarization, we repeated the experiments in Fig. 5 but with cells held at −100 mV (Fig. 6). The first αEPSP of each temporal summation trace was fitted with Eq. 2 to estimate RN, Cm, and τ (Fig. 6A). This analysis showed that at −100 mV, VTA DA cells of cocaine-treated rats manifested a significantly larger RN in combination with a reduced Cm. For example, the average RN for cells from cocaine-treated rats was 349.9 ± 24.1 MΩ (n = 7), whereas only 214.1 ± 29.2 MΩ (n = 8; P < 0.01; Fig. 6B) for cells from saline-injected animals. Similarly, the mean Cm at −100 mV in putative DA cells from cocaine-treated animals was 59.8 ± 1.7 pF (n = 7), whereas 77.6 ± 9.3 pF (n = 8; P < 0.05; Fig. 6C) for saline controls. As expected, this resulted in an augmented τ at −100 mV with a value of 20.6 ± 0.9 ms (n = 7) for neurons in the cocaine-sensitization group vs. 15.3 ± 1.1 ms (n = 8; P < 0.01; Fig. 6D) in cells from the saline treatment.

Fig. 6.

Cocaine sensitization increases the membrane time constant of VTA DA cells at −100 mV. A: representative temporal summation recordings generated by the somatic injection of a train of 5αEPSC (α = 5 ms; Ipeak = 50 pA) at 33 Hz of VTA DA neurons from cocaine (gray trace)- and saline (black trace)-treated animals after a 7-day withdrawal period. Each record is the average of 10 consecutive sweeps. The first αEPSP was least square fitted with Eq. 2. Cocaine: gray trace with black-fitted first αEPSP; saline: black trace with gray-fitted first αEPSP. B: summary graph showing that cocaine sensitization caused a significant augmentation of RN at −100 mV. C: summary graph showing that cocaine sensitization resulted in a significant reduction in Cm at −100 mV. D: summary graph showing that cocaine sensitization resulted in a significant augmentation in τ at −100 mV. In summary graphs B, C, and D, horizontal black segments with error bars represent means ± SE; unpaired t-test: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

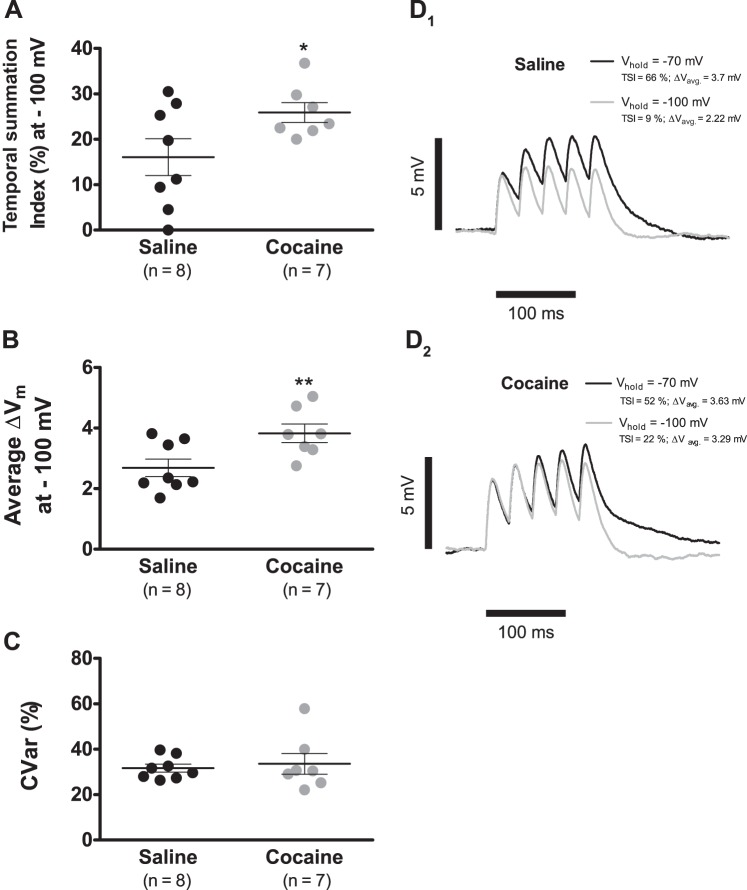

Fig. 7A shows that the TSI at −100 mV has a magnitude of 25.9 ± 2.1% (n = 7) in putative VTA DA neurons of cocaine-injected rats but in saline-exposed controls, is significantly smaller, with a value of 16.0 ± 4.0% (n = 8; P < 0.05). The mean depolarization, on the other hand, was significantly augmented in cells from cocaine-treated animals when contrasted against the saline reference (Fig. 7B; 2.7 ± 0.3 mV, n = 8, saline vs. 3.8 ± 0.3 mV, n = 7, cocaine; P < 0.01). As before, the variability about the mean depolarization was not altered by cocaine exposure (Fig. 7C; CVar = 31.6 ± 1.7%, n = 8, saline vs. CVar = 33.6 ± 4.5%, n = 7, cocaine; P > 0.05). Therefore, cocaine sensitization increases temporal summation at −100 mV (Fig. 7, D1 and D2).

Fig. 7.

Cocaine sensitization increases temporal summation at −100 mV. A: summary plot showing that cocaine sensitization leads to a significant augmentation of the TSI at −100 mV. B: summary plot showing that cocaine sensitization leads to a significant augmentation of the mean depolarization endured during temporal summation at −100 mV. C: summary plot showing that cocaine sensitization did not alter the variability around the mean depolarization measure in B. D1 and D2: overlay of representative temporal summation recordings of the same cell held at −70 and −100 mV. Each record is the average of 10 consecutive sweeps. Observe that cells from cocaine-sensitized rats, in contrast to saline controls, manifest and increase temporal summation at −100 mV. In summary plots A, B, and C, horizontal black segments with error bars represent means ± SE; unpaired t-test: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. CVar, coefficient of variation.

DISCUSSION

Concomitant to the development of cocaine sensitization, Ih and Cm are significantly reduced in putative VTA DA neurons (Arencibia-Albite et al. 2012). The present study shows that such alterations persist after 7 days of drug withdrawal. Therefore, the cocaine-induced Ih and capacitance attenuation represent enduring adaptations that possibly underlie the expression of sensitization after reinstatement of drug treatment.

This work adds to the evidence that substantiates that DA cell size and Ih are neuronal attributes relevant to the development of addiction. Chronic ethanol, for instance, attenuates Ih amplitude in VTA DA neurons (Hopf et al. 2007; Okamoto et al. 2006). Meanwhile, repeated morphine (Mazei-Robinson et al. 2011) and cannabis (Spiga et al. 2010) administration also evokes significant reduction in the size of DA neurons. As the chronic exposure to most of these drugs correlates with enhanced dopaminergic activity (Hopf et al. 2007; Mazei-Robinson et al. 2011; Saal et al. 2003), it can be argued that a reduction in Ih and capacitance could be augmenting DA cell excitation. Indeed, here, we showed that together, reduced Ih and capacitance increase the ability of DA neurons to integrate trains of EPSPs, and thus these adaptations may enhance input-dependent cell firing.

Long-term opiate administration is known to reduce the size of VTA DA neurons in rodents and in human addicts (Mazei-Robinson et al. 2011). This adaptation appears to be a consequence of the downregulation of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) signaling (Mazei-Robinson et al. 2011). Similarly, cocaine sensitization may also depress BDNF expression within the VTA, explaining the decreased capacitance after extended withdrawal. Nonetheless, this seems unlikely, as prolonged cocaine withdrawal elevates BDNF activity in the VTA (Grimm et al. 2003), whereas heterozygous BDNF knockout mice manifest less cocaine sensitization and a diminished cocaine-condition place preference (Hall et al. 2003). Another mechanism that might explain the reduced morphology is the cocaine-induced increased excitability. Repeated cocaine administration is positively correlated with enhanced DA cell excitation (Marinelli and White 2000; Saal et al. 2003). Mazie-Robison et al. (2011) had shown that a sufficient condition for the appearance of a reduced size is a substantial increase in the DA cell-firing rate. These researchers demonstrated that overexpression of a dominant-negative K+-channel subunit provokes a considerable increment in the spike rate, leading to the diminution of neuronal morphology. Therefore, it is possible that cocaine sensitization evokes a smaller cell size by improving DA neurotransmission.

A molecular adaptation that could underlie a diminished neuronal size and improved excitation is a cocaine-evoked epigenetic depression of the circadian locomotor output cycles kaput (CLOCK) gene. Mice lacking a functional form of this gene express an increased cocaine reward and augmented tonic and burst firing in VTA DA cells (McClung et al. 2005). Furthermore, in mice, deletion of exon 19 in the CLOCK gene results in the manifestation of manic-depressive behaviors that correlate with increased excitation and reduced VTA DA cell size (Coque et al. 2011). Remarkably, as mice were treated with lithium chloride (600 mg/l) in their drinking water for a period of 10 days, DA neurons normalize their size and level of excitation, plus manic-like behaviors were stabilized (Coque et al. 2011). Likewise, in rats, the initiation of cocaine-induced locomotor sensitization is blocked by lithium (100 mg/kg ip) (Xu et al. 2009). Therefore, it is plausible that cocaine sensitization by reprogramming the CLOCK gene-expression pattern is leading to a structurally compact and more excitable DA neuron. Further experiments should corroborate this hypothesis.

Recent evidence in DA cells of mice (Masi et al. 2015) and rats (Engel and Seutin 2015) shows that the inhibition of Ih evokes a minor enhancement in EPSP amplitude and slows down the decay rate of the synaptic signal, resulting in an augmented TSI with improved depolarization, as seen in other brain regions (Magee 1998; Stuart and Spruston 1998; Williams and Stuart 2003). Here, in contrast, at −70 mV, the EPSP amplitude and decay rate were dramatically augmented, whereas the TSI was significantly reduced, yet the membrane depolarization endured during synaptic summation was substantially elevated. It is unlikely, therefore, that in the VTA of rats, the cocaine-evoked Ih reduction contributes in any way to the observed synaptic response measured at depolarized potentials, since the altered single-EPSP and EPSP summation do not express the characteristic transformations ascribed to Ih blockade. In effect, at −70 mV, Ih amplitude is extremely small, and we found no significant differences in terms of Ih or input resistance between cocaine and control groups. This apparent lack of involvement of Ih in the transformation of the EPSP is not surprising, since in the VTA of mice, Ih voltage sag is not as pronounced as that measured in the neighboring substantia nigra pars compacta (SNc) (Masi et al. 2015), whereas in the VTA of rats, the inhibition of dopaminergic Ih has no effect on pacemaker firing or bursting (Hopf et al. 2007). Yet, in SNc of mice, the h-channel blockade may terminate spontaneous spiking (Gambardella et al. 2012), whereas in the SNc of rats, bath application of the Ih blocker ZD 7288, at −70 mV, hyperpolarizes the cell membrane and increases the neuron's input resistance (Engel and Seutin 2015). Consequently, the potentiated synaptic excitation under cocaine is at least caused by the reduced capacitance, which implies a diminished neuronal size. However, at −100 mV, where a significant difference in Ih amplitude exists between cells from cocaine-sensitized animals and controls, the observed increment in synaptic activity is consistent with that seen in mice (Masi et al. 2015) and rats (Engel and Seutin 2015). In light of the above data, it might be tempting to conclude that in VTA DA cells of rats, Ih has no synaptic role, since its contribution to the pacemaker subthreshold potential appears to be inconsequential (Hopf et al. 2007). Nevertheless, in the VTA of rats, acute cocaine may activate alpha-1 adrenergic receptors, increasing intrinsic cell firing through a mechanism that partly involves Ih amplitude augmentation (Goertz et al. 2015). Therefore, it is possible that under such conditions, the cocaine-evoked Ih attenuation may simultaneously slow down spontaneous activity and increase synaptic summation, leading to enhancement of the signal-to-noise ratio of afferent-triggered burst of spikes.

After our first report (Arencibia-Albite et al. 2012) on the cocaine-evoked capacitance attenuation, Mazei-Robinson et al. (2014) published data showing that the soma size of VTA DA neurons is not altered in rats that self administered cocaine (0.5 mg/kg/infusion), either for short-access (1 h/10 days) or long-access (6 h per 10 days) periods. In a neuron, where size is fixed, the shape of the αEPSP waveform is strictly a function of the ion channel kinetics underlying the synaptic signal, and so modifications in the membrane conductance are the only mechanisms that result in αEPSP trace transformation. Hence, if the apparent cocaine-diminished Cm is a space-clamp artifact, then it is possible that cocaine effects onto the αEPSP are entirely given by modifications in membrane conductance, with capacitance having no contribution in the observed change. The empirical measurements shown here suggest nonetheless that such a situation is highly unlikely, since at −70 mV, we did not observe differences in Ih amplitude or input resistance. Additionally, as explained before, the cocaine-evoked EPSP amplitude augmentation and improved summation at −70 mV are more likely to be a consequence of the reduced capacitance, since such enhancement in synaptic activity is inconsistent with Ih inhibition. Furthermore, our finding of diminished capacitance is in agreement with evidence that shows that lithium administration blocks the initiation of cocaine locomotor sensitization in rats (Xu et al. 2009) and is known to rescue normal VTA DA cell size in mice that manifest manic-depressive behaviors, partly as a consequence of a diminished DA neuron morphology (Coque et al. 2011). The difference between the present study and that of Mazei-Robinson et al. (2014) may be, at least, a result of dissimilar cocaine-treatment protocols.

In this study, Cm estimates were obtained from somatic recordings. If axial resistivity is substantially large, then most of the micropipette current leaks across the somatic membrane, with minor leakage through proximal dendritic or axonic membranes. This indicates that under such conditions, capacitance measurements are mainly detecting alterations of soma size and not changes in dendrite growth or spine proliferation. If this is the case for our study, then nearly all of the cocaine-induced capacitance reduction is due to the shrinkage of the cell soma. This hypothesis seems reasonable for two reasons. First, neurons are rarely isopotential when current clamped to a particular holding level, increasing the likelihood that measurements primarily reflect somatic capacitance. Second, a single exposure to cocaine may increase spine densities (Sarti et al. 2007), a result that should mitigate the overall change in capacitance if recorded cells are space clamped well.

The cocaine-evoked capacitance reduction reflects a decrease in neuronal size, which may help to understand two fundamental aspects of drug addiction: incentive sensitization and negative emotional states, e.g., anhedonia. The incentive sensitization theory postulates that in some individuals, repeated drug use renders the brain-reward circuit hypersensitive to drug-associated stimuli, resulting in a pathological motivation for drug seeking (Robinson and Berridge 2008). In cocaine addiction, the repeated paring of the drug with neutral stimuli, which typically does not elicit DA release, eventually increases DA secretion in the reward circuit when drug-dependent subjects are exposed to such neutral signals in the absence of cocaine (Volkow et al. 2006). This, in turn, may cause drug craving in a nearly proportional manner to the rise in DA concentration, i.e., the larger the signal-induced DA surge, the stronger the craving (Volkow et al. 2006). At the neuron level, the latter manifests as a fast burst of stimuli-driven action potentials that lead to the reinforcement of behaviors that predict and anticipate reward (Schultz 2007). Therefore, it is possible that the cocaine-evoked cell-size reduction may elevate the sensitivity of this cue-triggered DA release, as a smaller neuron tends to exhibit a higher level of excitability (Mazie-Robison et al. 2011). Accordingly, here, we show that a reduced capacitance enhances the temporal summation of synaptic inputs, and thus a reduced size may facilitate burst activity, which ultimately amplifies the anticipation of a reward that motivates cocaine-seeking behaviors (Schultz 2007). On the other hand, the negative emotional states that characterize addiction appear to follow from the DA depletion that emerges from chronic drug use (Dackis and Gold 1985; Shalev et al. 2002; Willuhn et al. 2014). This attenuated DA signaling partly explains why persons with addiction no longer experience as much pleasure from a drug as they did when they first used it. It also explicates why they often feel less motivated to engage in daily activities, previously found to be rewarding (Volkow et al. 2016). Consequently, it is possible that the cocaine-evoked DA cell-size reduction results in substantially low levels of TH, which explains the state of DA depletion and hence, the appearance of anhedonia and other negative emotions.

In conclusion, cocaine sensitization reduces Ih and capacitance in VTA DA neurons of rats. These adaptations outlasted 7 days of withdrawal and augmented EPSP amplitude and integration. Thus these cocaine-induced effects represent enduring neuronal modifications that may underlie the expression of sensitization subsequent to reinstatement of drug treatment.

GRANTS

Financial support was provided by grants from the National Institute of General Medical Science (GM-08224 and GM-084854) and the National Science Foundation (NSF-OISE-1545803; both to C. A. Jiménez-Rivera). The authors also acknowledge the National Center for Research Resources (2G12-RR003051) and National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (8G12-MD007600).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

F.A-A. and R.V-T. performed experiments; F.A-A., R.V-T., and C.A.J-R. analyzed data; F.A-A. and C.A.J-R. interpreted results of experiments; F.A-A. and R.V-T. prepared figures; F.A-A. and C.A.J-R. drafted manuscript; F.A-A., R.V-T., and C.A.J-R. edited and revised manuscript; F.A-A., R.V-T., and C.A.J-R. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work is part of the doctoral dissertation of F. Arencibia-Albite, submitted at the Department of Physiology, University of Puerto Rico Medical Sciences Campus.

REFERENCES

- Ackerman JM, White FJ. A10 somatodendritic dopamine autoreceptor sensitivity following withdrawal from repeated cocaine treatment. Neurosci Lett 117: 181–187, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angelo K, London M, Christensen SR, Häusser M. Local and global effects of I(h) distribution in dendrites of mammalian neurons. J Neurosci 27: 8643–8653, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arencibia-Albite F, Paladini C, Williams JT, Jiménez-Rivera CA. Noradrenergic modulation of the hyperpolarization-activated cation current (Ih) in dopamine neurons of the ventral tegmental area. Neuroscience 149: 303–314, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arencibia-Albite F, Vázquez R, Velásquez-Martinez MC, Jiménez-Rivera CA. Cocaine sensitization inhibits the hyperpolarization-activated cation current Ih and reduces cell size in dopamine neurons of the ventral tegmental area. J Neurophysiol 107: 2271–2282, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker DA, McFarland K, Lake RW, Shen H, Tang XC, Toda S, Kalivas PW. Neuroadaptations in cystine-glutamate exchange underlie cocaine relapse. Nat Neurosci 6: 743–749, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brager DH, Johnston D. Plasticity of intrinsic excitability during long-term depression is mediated through mGluR-dependent changes in I(h) in hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons. J Neurosci 27: 13926–13937, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr DB, Andrews GD, Glen WB, Lavin A. alpha2-Noradrenergic receptors activation enhances excitability and synaptic integration in rat prefrontal cortex pyramidal neurons via inhibition of HCN current. J Physiol 584: 437–450, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coque L, Mukherjee S, Cao JL, Spencer S, Marvin M, Falcon E, Sidor MM, Birnbaum SG, Graham A, Neve RL, Gordon E, Ozburn AR, Goldberg MS, Han MH, Cooper DC, McClung CA. Specific role of VTA dopamine neuronal firing rates and morphology in the reversal of anxiety-related, but not depression-related behavior in the ClockΔ19 mouse model of mania. Neuropsychopharmacology 36: 1478–1488, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dackis CA, Gold MS. New concepts in cocaine addiction: the dopamine depletion hypothesis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 9: 469–477, 1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel D, Seutin V. High dendritic expression of Ih in the proximity of the axon origin controls the integrative properties of nigral dopamine neurons. J Physiol 593: 4905–4922, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gambardella C, Pignatelli A, Belluzzi O. The h-current in the substantia nigra pars compacta neurons: a re-examination. PLoS One 7: e52329, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goertz RB, Wanat MJ, Gomez JA, Brown ZJ, Phillips PE, Paladini CA. Cocaine increases dopaminergic neuron and motor activity via midbrain a1 adrenergic signaling. Neuropsychopharmacology 40: 1151–1162, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimm JW, Lu L, Hayashi T, Hope BT, Su TP, Shaham Y. Time dependent increases in brain-derived neurotrophic factor protein levels within the mesolimbic dopamine system after withdrawal from cocaine: implications for incubation of cocaine craving. J Neurosci 23: 742–747, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall FS, Drgonova J, Goeb M, Uhl GR. Reduced behavioral effects of cocaine in heterozygous brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) knockout mice. Neuropsychopharmacology 28: 1485–1490, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry DJ, Greene MA, White FJ. Electrophysiological effects of cocaine in the mesoaccumbens dopamine system: repeated administration. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 251: 833–839, 1989. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopf FW, Martin M, Chen BT, Bowers MS, Mohamedi MM, Bonci A. Withdrawal from intermittent ethanol exposure increases probability of burst firing in VTA neurons in vitro. J Neurophysiol 98: 2297–2310, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalivas PW, Duffy P. Time course of extracellular dopamine and behavioral sensitization to cocaine. II. Dopamine perikarya. J Neurosci 13: 276–284, 1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knackstedt LA, LaRowe S, Mardikian P, Malcolm R, Upadhyaya H, Hedden S, Markou A, Kalivas PW. The role of cystine-glutamate exchange in nicotine dependence in rats and humans. Biol Psychiatry 65: 841–845, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knackstedt LA, Melendez RI, Kalivas PW. Ceftriaxone restores glutamate homeostasis and prevents relapse to cocaine seeking. Biol Psychiatry 67: 81–84, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis AS, Vaidya SP, Blaiss CA, Liu Z, Stoub TR, Brager DH, Chen X, Bender RA, Estep CM, Popov AB, Kang CE, Van Veldhoven PP, Bayliss DA, Nicholson DA, Powell CM, Johnston D, Chetkovich DM. Deletion of the hyperpolarization-activated cyclic nucleotide-gated channel auxiliary subunit TRIP8b impairs hippocampal Ih localization and function and promotes antidepressant behavior in mice. J Neurosci 31: 7424–7440, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magee JC. Dendritic hyperpolarization-activated currents modify the integrative properties of hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons. J Neurosci 18: 7613–7624, 1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mardikian PN, LaRowe SD, Hedden S, Kalivas PW, Malcolm RJ. An open-label trial of N-acetylcysteine for the treatment of cocaine dependence: a pilot study. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 31: 389–394, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margolis EB, Lock H, Chefer VI, Shippenberg TS, Hjelmstad GO, Fields HL. Kappa opioids selectively control dopaminergic neurons projecting to the prefrontal cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 2938–2942, 2006a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margolis EB, Lock H, Hjelmstad GO, Fields HL. The ventral tegmental area revisited: is there an electrophysiological marker for dopaminergic neurons? J Physiol 577: 907–924, 2006b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marinelli M, White FJ. Enhanced vulnerability to cocaine self-administration is associated with elevated impulse activity of midbrain dopamine neurons. J Neurosci 20: 8876–8885, 2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masi A, Narducci R, Resta F, Carbone C, Kobayashi K, Mannaioni G. Differential contribution of Ih to the integration of excitatory synaptic inputs in substantia nigra pars compacta and ventral tegmental area dopaminergic neurons. Eur J Neurosci 42: 2699–2706, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazei-Robison MS, Appasani R, Edwards S, Wee S, Taylor SR, Picciotto MR, Koob GF, Nestler EJ. Self-administration of ethanol, cocaine, or nicotine does not decrease the soma size of ventral tegmental area dopamine neurons. PLoS One 9: e95962, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazei-Robison MS, Koo JW, Friedman AK, Lansink CS, Robison AJ, Vinish M, Krishnan V, Kim S, Siuta MA, Galli A, Niswender KD, Appasani R, Horvath MC, Neve RL, Worley PF, Snyder SH, Hurd YL, Cheer JF, Han MH, Russo SJ, Nestler EJ. Role for mTOR signaling and neuronal activity in morphine-induced adaptations in ventral tegmental area dopamine neurons. Neuron 72: 977–990, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClung CA, Sidiropoulou K, Vitaterna M, Takahashi JS, White FJ, Cooper DC, Nestler EJ. Regulation of dopaminergic transmission and cocaine reward by the Clock gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 9377–9381, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mrejeru A, Wei A, Ramirez JM. Calcium-activated non-selective cation currents are involved in generation of tonic and bursting activity in dopamine neurons of the substantia nigra pars compacta. J Physiol 589: 2497–2514, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto T, Harnett MT, Morikawa H. Hyperpolarization-activated cation current (Ih) is an ethanol target in midbrain dopamine neurons of mice. J Neurophysiol 95: 619–626, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson C. The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. San Diego: Academic, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Rall W, Agmon-Snir H. Cable theory for dendritic neurons. In: Methods in Neuronal Modeling: from Ions to Networks, edited by Koch C and Segev I. Cambridge, MA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson TE, Berridge KC. Addiction. Annu Rev Psychol 54: 25–53, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson TE, Berridge KC. Review. The incentive sensitization theory of addiction: some current issues. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 363: 3137–3146, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russo SJ, Bolanos CA, Theobald DE, Decarolis NA, Renthal W, Kumar A, Winstanley CA, Renthal NE, Wiley MD, Self DW, Russell DS, Neve RL, Eisch AJ, Nestler EJ. RS2-Akt pathway in midbrain dopamine neurons regulates behavioral and cellular responses to opiates. Nat Neurosci 10, 93–99, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saal D, Dong Y, Bonci A, Malenka RC. Drugs of abuse and stress trigger a common synaptic adaptation in dopamine neurons. Neuron 37: 577–582, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sari Y, Smith KD, Ali PK, Rebec GV. Upregulation of GLT1 attenuates cue-induced reinstatement of cocaine-seeking behavior in rats. J Neurosci 29: 9239–9243, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarti F, Borgland SL, Kharazia VN, Bonci A. Acute exposure alerts spine density and long-term potentiation in ventral tegmental area. Eur J Neurosci 26: 749–756, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz JM, Mooney ME, Moeller FG, Stotts AL, Green C, Grabowski J. Levodopa pharmacotherapy for cocaine dependence: choosing the optimal behavioral therapy platform. Drug Alcohol Depend 94: 142–150, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz W. Multiple dopamine functions at different time courses. Annu Rev Neurosci 30: 259–288, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shalev U, Grimm JW, Shaham Y. Neurobiology of relapse to heroin and cocaine seeking: a review. Pharmacol Rev 54: 1–42, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiga S, Lintas A, Migliore M, Diana M. Altered architecture and functional consequences of the mesolimbic dopamine system in cannabis dependence. Addict Biol 15: 266–276, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steketee JD, Kalivas PW. Drug wanting: behavioral sensitization and relapse to drug-seeking behavior. Pharmacol Rev 63: 348–365, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuart G, Spruston N. Determinants of voltage attenuation in neocortical pyramidal neuron dendrites. J Neurosci 18: 3501–3510, 1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vetter P, Roth A, Hausser M. Propagation of action potentials in dendrites depends on dendritic morphology. J Neurophysiol 85: 926–937, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Koob GF, McLellan AT. Neurobiologic advances from the brain disease model of addiction. N Engl J Med 374: 363–371, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Telang F, Fowler JS, Logan J, Childress AR, Jayne M, Ma Y, Wong C. Cocaine cues and dopamine in dorsal striatum: mechanism of craving in cocaine addiction. J Neurosci 26: 6583–6588, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams SR, Stuart GJ. Voltage- and site-dependent control of the somatic impact of dendritic IPSPs. J Neurosci 23: 7358–7367, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willuhn I, Burgeno LM, Groblewski PA, Phillips PE. Excessive cocaine use results from decreased phasic dopamine signaling in the striatum. Nat Neurosci 17: 704–709, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf ME, Sun X, Mangiavacchi S, Chao SZ. Psychomotor stimulants and neuronal plasticity. Neuropharmacology 47, Suppl 1: 61–79, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu CM, Wang J, Wu P, Zhu WL, Li QQ, Xue YX, Zhai HF, Shi J, Lu L. Glycogen synthase kinase 3beta in the nucleus accumbens core mediates cocaine-induced behavioral sensitization. J Neurochem 111: 1357–1368, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou W, Kalivas PW. N-acetylcysteine reduces extinction responding and induces enduring reductions in cue- and heroin-induced drug-seeking. Biol Psychiatry 63: 338–340, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]