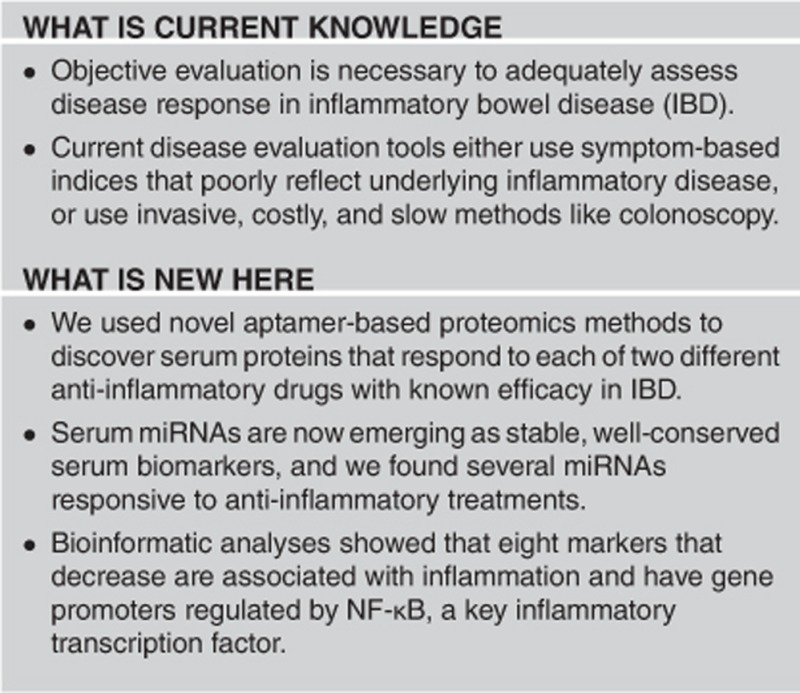

Abstract

Objective:

Serum biomarkers may serve to predict early response to therapy, identify relapse, and facilitate drug development in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Biomarkers are particularly important in children, in whom achieving early remission and minimizing procedures are especially beneficial.

Methods:

We profiled protein and micro RNA (miRNA) in serum from patients pre- and post-therapy, to identify molecular markers of pharmacodynamic effect. Serum was obtained from children with IBD before and after treatment with either corticosteroids (prednisone; n=12) or anti-tumor necrosis factor-α biologic (infliximab; n=7). Over 1,100 serum proteins were assayed using aptamer-based SOMAscan proteomics, and 22 miRNAs analyzed by quantitative real time PCR. Concordance of longitudinal changes between the groups was used to identify markers responsive to treatment. Bioinformatic analysis was used to build insight into mechanisms of changes in response to treatment.

Results:

We identified 18 proteins and three miRNAs responsive to both prednisone and infliximab. Eight markers that decreased are associated with inflammation and have gene promoters regulated by nuclear factor (NF)-κB. Several that increased are associated with resolving inflammation and tissue damage. We also identified six markers that appear to be steroid-specific, three of which have glucocorticoid receptor binding elements in their promoter region.

Conclusions:

Serum markers regulated by the inflammatory transcription factor NF-κB are potential candidates for pharmacodynamic biomarkers that, if correlated with later outcomes like endoscopic or histologic healing, could be used to monitor treatment, optimize dosing, and enhance drug development. The pharmacodynamic biomarkers identified here hold potential to improve both clinical care and drug development. Further studies are warranted to investigate these markers as early predictors of response, or possibly surrogate outcomes.

Introduction

The onset, symptoms, and progression of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) are highly variable and unpredictable. A variety of phenotypes exist; extra-intestinal inflammation may manifest as uveitis, arthritis, or growth failure in children. Therapies for IBD are focused on the induction and maintenance of remission, and the prevention of longer-term complications of chronic inflammation, such as relapsing disease, steroid-dependence, malnutrition, growth-stunting in children, and colorectal cancer. There is a disconnect between patient symptoms and mucosal inflammation, and increasing evidence in adults with IBD shows that long-term clinical outcomes are not improved by treating to symptom remission, but are improved by directly targeting mucosal inflammation.1, 2 Practically, using ileocolonoscopy and imaging to monitor disease response requires waiting 3–6 months for cycles of repair to occur, followed by re-assessment of healing by endoscopy or imaging, adjusting therapy based on these results, and then repeating the evaluation again.3 Though this may currently be the optimal approach available, acceptance of repeated colonoscopy as a widespread clinical practice or as a clinical trial endpoint may be limited by patient discomfort, procedural risk, anesthesia, and high cost. This is a particularly important issue in pediatric clinical care, and a barrier to recruitment in pediatric clinical trials.4

There is a need for biomarkers to predict response to therapy and optimize treatment regimens to improve quality of life. Such biomarkers are particularly important in children.5 Facing a long or lifetime duration of disease encompassing important stages of development, the disease manifestations, side-effects of current therapies, and exposure to repeated invasive procedures may have greater negative impacts on children and their families. In addition to treatment decisions, serum biomarkers may inform earlier dosing, safety, and efficacy decisions in pediatric clinical trials. Currently, a small number of clinically-utilized biomarkers of disease response are available to the IBD clinician, as recently reviewed in Sands et al.6

New candidates have been identified as potential blood-based biomarkers in IBD, but the effect of specific treatments on the prospective change of these biomarkers has not been investigated. These include proteins, as well as micro RNAs (miRNAs), which are emerging as promising treatment-responsive biomarkers. Recently, serum SERPINA1 (α-1-antitrypsin) was shown to differentiate between mild and more severe forms of adult ulcerative colitis (UC), and appears to be superior to C-reactive protein in this regard.7, 8 In two recent studies, circulating miRNAs were measured in patients with Crohn's disease (CD) and/or UC. One study found 24 serum miRNAs differentially expressed in children with CD.9 The other study found three sets of peripheral blood miRNAs that distinguish between active CD, UC, and healthy adult patients.10 Bridging specific biomarkers to drug response (for example, pharmacodynamic biomarkers) will be a necessary step in establishing a biomarker as a treatment monitoring tool or as an outcome measure in clinical trials. In this exploratory study, our goal was to carry out a broad discovery of pharmacodynamic biomarkers that show response to corticosteroid and anti-tumor necrosis factor-α (TNFα) biologic treatment of pediatric IBD. Our hypothesis was that serum inflammatory proteins and miRNAs that lie in the pathway of drug effect, and that change in the same direction after treatment with both classes of drugs, are candidates for further study as potential surrogate outcome measures.

Methods

Ethics statement

All work was conducted according to relevant national and international guidelines, reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Children's National Health System.

Patients, treatment, and serum collection

Patients ranged in age from 9 to 19 years, and were all cared for at Children's National Health System, a quaternary-care, free-standing children's hospital in Washington, DC, USA that serves ~400 IBD patients. Patients with IBD were randomly recruited for this study, which was designed for the collection of serum samples pre- and post-treatment to evaluate longitudinal changes in proteins and miRNAs. Demographics and clinical characteristics of the two patient groups are provided in Table 1. All were outpatients, treated as indicated per their gastroenterologist; follow-up serum samples were drawn at the time of a clinically indicated lab-draw. There were no entry disease scores or criteria. Most patients were evaluated by ileocolonoscopy or magnetic resonance enterography prior to starting therapy. Two patients were started on infliximab to treat perianal disease. One child was started on infliximab for growth failure. Two patients reported no symptoms, but therapy was escalated to infliximab because of elevated serum inflammatory markers and endoscopic inflammation. For this study, we selected patients treated with infliximab who were not recently exposed to corticosteroids or immunomodulators.

Table 1. Patient clinical characteristics, treatment dosing and schedule, clinical scores, and serum inflammatory markers.

| Study description | Prednisone cohort | Infliximab cohort |

|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 12 | 7 |

| Age (years) | 12.2±2.4 | 15.7±1.8 |

| Males:females | 6 M:6 F | 4 M:3 F |

| Patient diagnoses | 10 CD:2 UC | 7 CD |

| Disease years | 11 newly dx'd | |

| 1 CD 4.1 yrs* | 2.1±1.6 | |

| Paris classification disease location53 | ||

| L1 (distal 1/3 ileum) | 1 | |

| L1,L4b (distal 1/3 ileum, upper GI distal to ligament of Treitz | 1 | |

| L2 (colonic) | 2 | 1 |

| L2, p (colonic, perianal disease) | 1 | |

| L3 (ileocolonic) | 4 | 1 |

| L3,p (ileocolonic, perianal disease) | 1 | 4 |

| L3,L4a (ileocolonic, upper GI proximal to the ligmant of Treitz | 1 | |

| Treatment time (weeks) | 9.4±4.4 | 6.1±0.3 |

| Treatment regimen | Daily prednisone | Two infusions, 5 mg/kg |

| Dose range | 0.6–1 mg/kg | 2 weeks apart |

| CRP levels (mg/dl, normal 0.06–0.79) | ||

| Pre-treatment | 3.7±3.1 | 1.1±1.0 |

| Post-treatment | 0.5±0.8 | 0.6±0.5 |

| P-value | 0.003 | 0.2 |

| ESR (mm/h, normal 0–20) | ||

| Pre-treatment | 44.4±32.0 | 31.0±19.7 |

| Post-treatment | 22.5±14.9 | 12.3±6.5 |

| P-value | 0.06 | 0.07 |

| PCDAI | ||

| Pre-treatment | 36.5±16.4 | 16.4±11.4 |

| Post-treatment | 11.0±7.8 | 9.6±12.1 |

| P-value | 0.06 | 0.07 |

| PUCAI (2 UC patients treated with prednisone) | ||

| Pre-treatment | 70, 85** | |

| Post-treatment | 15, 40** |

CD, Crohn's disease; CRP, C-reactive protein; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; GI, gastrointestinal; PCDAI, Patient Crohn's Disease Activity Index; UC, ulcerative colitis. (*patient received 5-ASA prior to study; values are mean±s.d.; paired t-test). (**two patient scores).

Corticosteroid-treated patients received daily oral prednisone at standard 1 mg/kg dosing up to a maximum of 40 mg daily. All but one steroid-treated patient was newly diagnosed, without baseline exposure to other medications. The one previously diagnosed patient with CD had only been exposed to mesalamine at diagnosis. None of the infliximab-treated patients were treated with concurrent steroids or immunomodulators, and received standard induction dosing of infliximab (5 mg/kg/dose) at time 0 and week 2.

As our goal was to identify pharmacodynamic effects of therapy, we chose a longitudinal approach. We focused, in this initial discovery study, on obtaining an early read-out of physiologic biomarker change after administration of therapy. We chose not to wait for a longer period to fully assess clinical or endoscopic response or remission (typically 12–52 weeks of treatment), as this would have the potential to introduce more variability and dilute a pharmacological effect. Two blood samples were obtained from each patient, one before treatment (baseline control), and one after treatment with either prednisone or infliximab (paired sample for longitudinal analysis). Duration of steroid treatment ranged from 3 to 18 weeks. For infliximab, post-drug samples were drawn at 6 weeks after treatment initiation, just prior to the third induction dose. Pediatric Crohn's Disease Activity Index and Pediatric Ulcerative Colitis Activity Index were recorded at both pre- and post-treatment time points, as were C-reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate.

Proteomic profiling

Proteins were profiled using a SOMAscan assay (SomaLogic; Boulder, CO, USA) that analyzed either 1,120 unique proteins (prednisone group; 1st-generation panel), or 1,300 proteins (infliximab group; 2nd-generation panel), as previously described.11, 12 In total, 70 μl of serum per patient was used to measure all proteins in a multiplex manner. Each aptamer targets a specific protein and is tagged with a unique DNA sequence permitting its quantification. Protein-aptamer levels were quantified on Agilent hybridization arrays in relative fluorescent units and analyzed using SomaSuite version 1.0 (SomaLogic). Protein levels were log transformed and tested to verify normality. Eleven patients were included in the prednisone group (nine CD, two UC) and seven patients in the infliximab group (seven Crohn's). The two treatment groups were analyzed separately using paired t-tests, comparing baseline to post-treatment values. A P-value of 0.05 was set as the significance threshold, without adjustment for multiple comparisons. To reduce false-positive discovery in this setting, we used an evidence-based approach where results from the two groups were cross-referenced. Proteins that significantly changed in the same direction in each of the two separate groups were considered candidate biomarkers.

miRNA profiling

RNA was isolated using TRIzol with overnight isopropanol precipitation. The same patient samples were analyzed for miRNA, with the addition of one more CD patient in the prednisone group. A total of 12 patients were included in the prednisone group (10 CD and 2 UC) and 7 in the infliximab group (7 CD). We used separate aliquots of the same patient serum samples used for SOMAscan, plus one additional prednisone-treated patient. We performed targeted quantification of 24 miRNAs selected for their prior detection in either inflammation or steroid-responses (primer/probe sets in Supplementary Table S1).13 Complementary DNA was synthesized using multiplexed RT primers, preamplified using TaqMan PreAmp Master Mix (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA), and miRNAs quantified using individual TaqMan assays on an ABI 7900HT.14 miRNAs were normalized to the geometric mean of multiple control genes, followed by statistical comparison of baseline to post-treatment values by paired t-test.15, 16 Control miRNAs (hsa-miR-342-3p and hsa-miR-150-5p) were previously identified as stable control reference miRNAs in IBD patient serum.9

Bioinformatics

We examined regulation of gene promoters for each biomarker candidate to gain insight into mechanisms of their response to treatment. Promoter binding by the inflammatory transcription factor nuclear factor (NF)-κB or the glucocorticoid receptor (GR) steroidal transcription factor was examined using chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing (ChIP-seq) data from ENCODE. ChIP-seq data from ENCODE and Factorbook was used to query physical binding of candidate gene promoters.17, 18 Data/images were produced using UCSC Genome Browser Release 4 with alignment to human reference genome GRCh37/hg19.17, 19 Within ChIP-seq peaks, sequences were downloaded and analyzed using UCSC and/or JASPAR version 5.0a.20 ChIP-seq data sets were obtained from TNFα-induced human immune cells (RelA), and dexamethasone-induced human lung, liver and endometrial cell lines (NR3C1). Heat maps were generated with Hierarchical Clustering Explorer Version 3.5 (Human Computer Interaction Laboratory; University of Maryland, College Park, MD, USA). To examine interactions between the identified molecular markers, we performed gene pathway analysis using Ingenuity Pathway Analysis, IPA Version 26127183 (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany).

Results

Proteomic responses to treatment

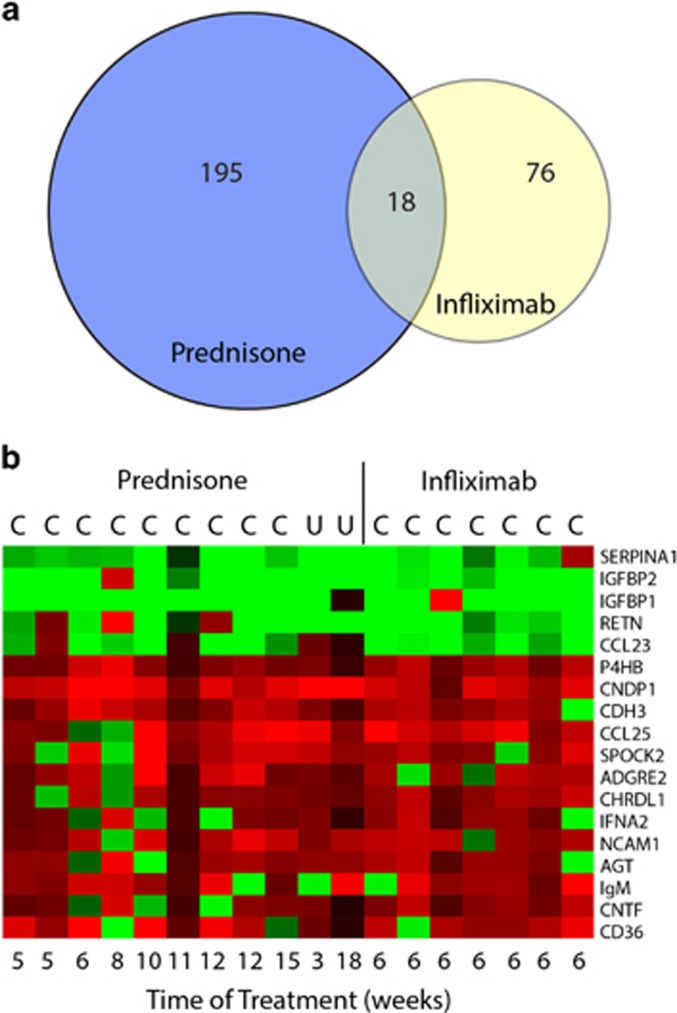

Aptamer-based proteomics was used to profile serum protein levels pre- and post-treatment (Figure 1). For prednisone-treated children, 213 proteins showed significant changes (Supplementary Table S2). For infliximab-treated children, 94 proteins showed significantly different levels after treatment (Supplementary Table S3). Eighteen proteins showed a significant change in the same direction for both prednisone and infliximab therapy (Table 2). Of these, five proteins showed a significant decrease in response to treatment. These proteins have known functions associated with inflammation, including α-1-antitrypsin (SERPINA1), insulin-like growth factor binding protein 1 and 2 (IGFBP1 and IGFBP2), resistin (RETN), and C-C motif chemokine 23 (CCL23).

Figure 1.

Summary of serum protein changes. (a) Venn diagram of proteomics results analyzing serum changes of proteins in the Prednisone and Infliximab treatment groups. (b) Heat map visualization of the fold changes of the 16 overlapping protein markers within each patient. (red=increased, green=decreased).

Table 2. Differential expression of serum proteins by both treatment groups (prednisone and infliximab), indicating the direction of change, and a description of the general protein function.

|

Glucocorticoid cohort |

Infliximab cohort |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene | ↑ or ↓ | P-value | Pre (RFU)a | Post (RFU)a | P-value | Pre (RFU)a | Post (RFU)a | Description |

| SERPINA1 | ↓ | <0.001 | 6.90±0.26 | 6.52±0.17 | 0.017 | 6.77±0.15 | 6.65±0.07 | Increased in inflammation |

| IGFBP2 | ↓ | 0.003 | 10.88±0.47 | 10.17±0.34 | 0.006 | 6.90±0.40 | 6.40±0.48 | Increased in inflammation |

| IGFBP1 | ↓ | 0.006 | 8.34±0.65 | 7.01±0.82 | 0.025 | 7.92±0.86 | 6.92±0.87 | Increased in inflammation |

| RETN | ↓ | 0.025 | 8.49±0.53 | 8.13±0.43 | 0.004 | 8.31±0.45 | 8.06±0.36 | Increases cytokines |

| CCL23 | ↓ | 0.030 | 8.23±0.31 | 7.97±0.21 | 0.020 | 7.93±0.37 | 7.66±0.37 | Chemotactic for monocytes |

| P4HB | ↑ | <0.001 | 6.02±0.05 | 6.14±0.07 | 0.001 | 6.10±0.09 | 6.22±0.09 | Integrin binding |

| CNDP1 | ↑ | <0.001 | 9.02±0.35 | 9.61±0.40 | 0.005 | 8.26±0.44 | 8.55±0.50 | Improved cancer prognosis |

| CDH3 | ↑ | <0.001 | 9.76±0.20 | 10.01±0.17 | 0.044 | 10.34±0.16 | 10.47±0.15 | Cell adhesion |

| CCL25 | ↑ | 0.006 | 7.53±0.51 | 7.92±0.68 | 0.005 | 7.86±0.55 | 8.21±0.57 | Protective in colitis |

| SPOCK2 | ↑ | 0.011 | 6.48±0.29 | 6.81±0.16 | 0.018 | 6.71±0.24 | 6.84±0.19 | ECM binding |

| ADGRE2 | ↑ | 0.021 | 5.90±0.25 | 6.15±0.32 | 0.036 | 6.62±0.23 | 6.79±0.16 | Promotes cytokine release |

| CHRDL1 | ↑ | 0.021 | 7.69±0.14 | 7.81±0.12 | 0.010 | 7.84±0.16 | 7.98±0.14 | BMP4 antagonist |

| IFNA2 | ↑ | 0.024 | 5.27±0.12 | 5.33±0.09 | 0.023 | 4.98±0.09 | 5.04±0.10 | JAK/STAT signaling |

| NCAM1 | ↑ | 0.026 | 8.89±0.31 | 9.11±0.21 | 0.030 | 9.10±0.23 | 9.26±0.20 | Cell adhesion |

| AGT | ↑ | 0.033 | 8.67±0.21 | 8.84±0.20 | 0.022 | 8.86±0.14 | 8.98±0.20 | Vasoconstriction |

| IgM | ↑ | 0.034 | 7.45±0.39 | 7.64±0.50 | 0.036 | 7.94±0.28 | 8.10±0.16 | B-cell antibody |

| CNTF | ↑ | 0.042 | 6.47±0.13 | 6.53±0.12 | 0.004 | 5.73±0.08 | 5.79±0.11 | Protective in inflammation |

| CD36 | ↑ | 0.046 | 8.05±0.33 | 8.33±0.44 | 0.039 | 8.76±0.32 | 8.96±0.28 | Pro-resolution M2 |

BMP4, bone morphogenetic protein 4; ECM, extracellular matrix; JAK/STAT, Janus kinase and a Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription; M2, M2 macrophage; RFU, relative fluorescent units.

Values are log transformed mean±s.d.

The specific SOMAscan panels utilized for the two groups were slightly different, in that the prednisone-treated group was tested using a 1,120 protein panel, whereas the infliximab-treated group was tested with a newer 1,300 protein panel. Thus, ~180 additional proteins were assayed in the infliximab group. Eleven of these significantly changed with infliximab, but were not able to be cross-referenced in the prednisone-treated data set (Supplementary Table S4). These include CD177 antigen (CD177), chitinase-3-like protein 1 (CHI3L1), protein S100A12 (S100A12), and C-X-C motif chemokine 9 (CXCL9), which are inflammatory proteins that decreased with infliximab.

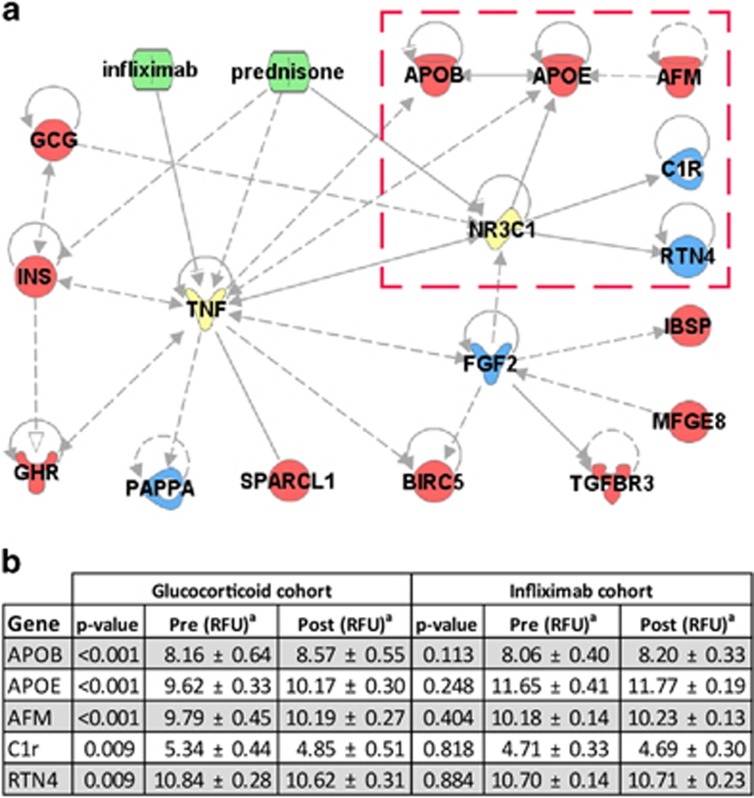

To identify potential steroid-specific responses, we used bioinformatics to screen differentially expressed proteins for established interactions with either the GR or TNFα. We found that the genes encoding three of these proteins were direct targets of the GR (Figure 2). These include apolipoprotein E, complement subcomponent C1r, and reticulon 4. An additional two, apolipoprotein B and afamin, were direct targets of apolipoprotein E. Other markers were more indirectly connected to the GR or were regulated by TNFα as well. Because they changed exclusively in response to prednisone, and are known to be regulated by the GR, these five proteins may represent steroid-specific biomarkers.

Figure 2.

Potential steroid-specific protein markers. To identify potential steroid-specific biomarkers, we used Ingenuity Pathway Analysis to screen proteins significantly altered by prednisone but not by infliximab. (a) Three proteins were found to be directly regulated by the glucocorticoid receptor (GR, or NR3C1) but not by TNF. An additional two were found to be regulated by one of its direct targets, but not by TNF. These five proteins (marked by a red box) were selected as potential steroid-specific markers. (b) Proteomic expression data for these five targets demonstrates that these were affected by prednisone treatment but not by infliximab treatment. (aValues are log transformed mean±s.d.; red=increased, blue=decreased, green=drug, yellow=direct drug targets, NR3C1=glucocorticoid receptor).

We did not aim to correlate biomarkers with established clinical or biochemical response following this rather short-treatment period. However, we did note that a majority of patients in both groups did show expected improvement in clinical and biochemical measures following treatment. Prednisone treatment (n=12) resulted in a significant improvement in C-related protein (P<0.005) and pediatric Crohn's disease index (P<0.001, n=10 Crohn's patients), along with a trend of improvement in erythrocyte sedimentation rate (P=0.06). Infliximab treatment (n=7) led to a trend of improvement in each of these three measures (C-related protein, P=0.2; Pediatric Crohn's Disease Activity Index, P=0.09; erythrocyte sedimentation rate, P=0.07). Non-statistically significant trends also likely reflect our small sample size.

miRNA responses to treatment

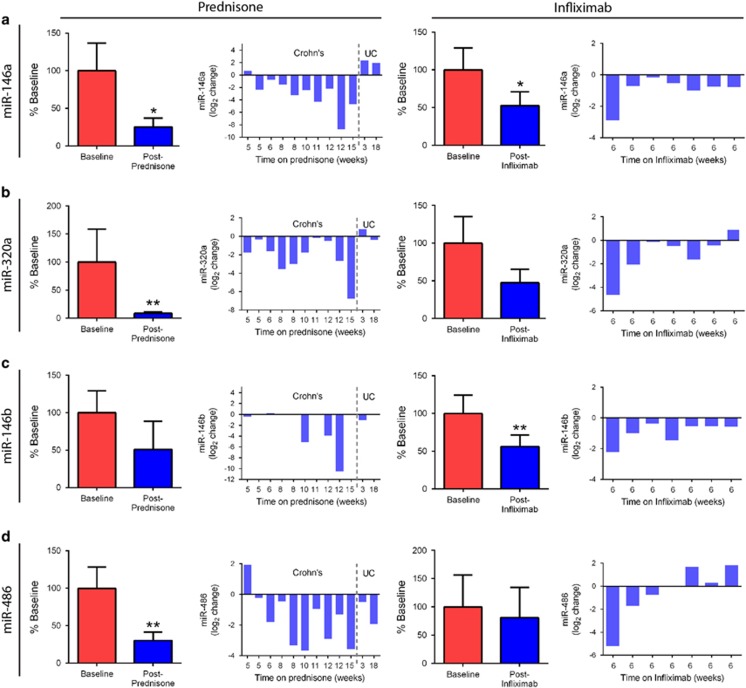

We identified four miRNAs that responded to treatment using quantitative real time PCR (Figure 3). Of these, three decreased with both prednisone and infliximab: miR-146a, miR-320a, and miR-146b. These miRNAs have been associated with inflammation. Notably, in individual patients, it appeared there may be a relationship between the size of effect and the duration of prednisone treatment. In addition, the two UC patients appeared to show a different pattern of miRNA response to treatment. Interestingly, other groups have found differences in serum miRNAs between Crohn's and UC, which may be consistent with our observations.10 A fourth miRNA, miRNA-486, showed a significant change in response to prednisone (P<0.01), but not to infliximab. These data provide a panel of miRNAs that are responsive to two anti-inflammatory drugs with different mechanisms of action.

Figure 3.

Serum microRNA levels change with prednisone or infliximab treatment. Levels of miRNAs were assayed by qRT-PCR. Bar graphs of the percent baseline levels for each treatment group, as well as change in expression for each individual patient, are provided for each miRNA. (a) miR-146a in response to prednisone (a) and infliximab (a'). miR-320a in response to prednisone (b) and infliximab (b'). miR-146b in response to prednisone (c) and infliximab (c'), note; four post-treatment and two baseline samples had miR-146b levels below detection threshold. (d) miR-486 in response to prednisone (d) and infliximab (d'). (*P<0.05, **P<0.01; paired t-test).

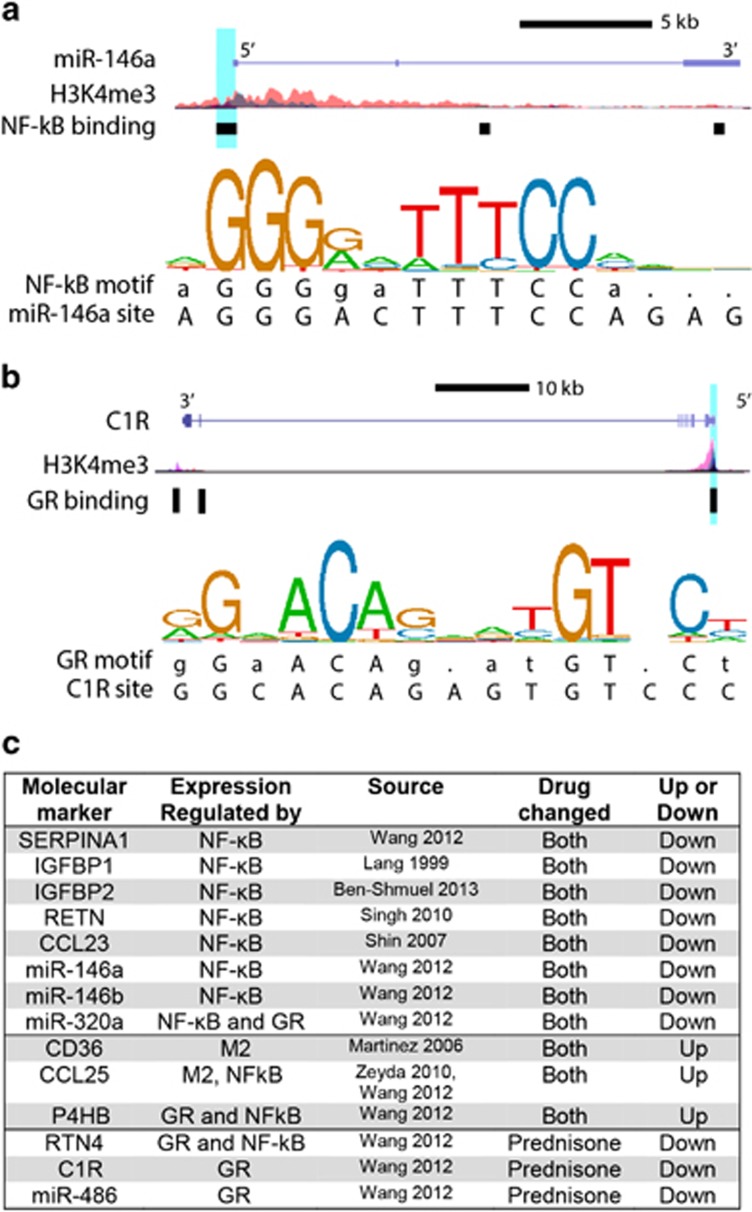

Bioinformatic analysis of gene regulation pathways

We found in ChIP-seq data and established literature that the majority of markers, which decreased with both drugs have gene promoters directly bound by NF-κB (Figure 4).18, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26 This includes the protein SERPINA1, which is known to be elevated in IBD, and three miRNAs (miR-146a, 146b, and 320a). When we assessed steroid receptor binding, we found genes for three of the steroid-specific markers possess promoter elements directly bound by the GR, including complement subcomponent C1r and miR-486 (Figure 4). Together, this indicates that gene expression regulation for these markers is consistent with their response to treatment.

Figure 4.

Promoter analysis of serum markers. (a) Schematic of the gene locus for miR-146a, illustrating the binding site and sequence of a promoter element bound by NF-κB. (b) Schematic of the gene locus for C1R, illustrating the binding site and sequence of a promoter element bound by GR. (c) Summary of promoter analysis and literature data indicating the marker and known elements associated with its regulation. (H3K4me3=histone modification associated with active gene promoters, Blue highlight=site of promoter bound by transcription factor, with relevant sequence provided below consensus motif sequence logo, M2=expressed by pro-resolution M2 macrophages).

We found that 11 of the identified proteins are established to have connections to each other through interactions with NF-κB, TNFα, and/or the GR (Figure 5). This further establishes these molecular changes as part of a systemic network response to effective anti-inflammatory treatment.

Figure 5.

Pathway analysis of serum markers that change in response to treatment. Gene pathways of serum markers that responded to treatment were analyzed using Ingenuity Pathway Analysis. Established gene network connections were present between 11 of the 18 drug-responsive protein markers and NF-κB, NR3C1, or TNF. (red=increased, blue=decreased, green=drug, yellow=direct drug targets, NR3C1=glucocorticoid receptor).

Discussion

We have identified 18 proteins and 3 miRNAs that are responsive to both prednisone and infliximab treatment. Both of these drugs target inflammatory TNFα and NF-κB signaling, but they do so via distinctly different mechanisms. Infliximab is an antibody that specifically binds to and inactivates the TNFα cytokine (ligand), blocking its NF-κB-mediated antiapoptotic effects.27 In contrast, prednisone is a corticosteroid that binds to and activates the GR. Activated GR then binds to NF-κB complexes to inhibit downstream TNFα-mediated inflammation.28 However, prednisone-activated GR shows many additional activities outside of NF-κB transrepression, as it also binds directly to hundreds of DNA elements that affect additional gene expression pathways.29 By overlaying molecular changes in serum from patients treated with these partially overlapping drug mechanisms, we have identified ~20 serum-based pharmacodynamic markers of anti-inflammatory therapies.

All five of the NF-κB-regulated proteins that decrease with treatment have roles in inflammation. The first is α-1-antitrypsin, or SERPINA1, a serine protease inhibitor that induces T-regulatory cell expansion.30, 31, 32 Notably, serum SERPINA1 already shows potential as a diagnostic biomarker in IBD.7, 8 A second protein, CCL23, is a chemokine known to be elevated in both IBD and rheumatoid arthritis.33, 34 NF-κB regulates CCL23, which then increases expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines, chemokines and adhesion molecules.35 Another protein marker, resistin, or RETN, is an adipocytokine that shows species-specific tissue expression and is induced by TNFα in human macrophages.25, 36 Corticosteroids are known to affect RETN, though these effects may be time-specific.37, 38 Finally, both IGFBP1 and IGFBP2 decrease with prednisone and infliximab. The IGF-binding proteins regulate endocrine actions of insulin-like growth factors, and IGFBP1 is primarily produced by the liver during states of inflammation. IGFBP2 and IGFBP3 have been shown to decrease after high-dose corticosteroids in Crohn's disease and UC.39 Our results suggest these effects on IGFBP proteins may not be steroid-specific.

Twelve proteins increased with treatment of IBD by both drugs. Many of these have a role in resolving tissue damage. CNTF is a polypeptide hormone, which acts as a growth and survival factor to reduce inflammatory tissue destruction in a variety of injury types.40, 41 Cadherin 3, or p-cadherin, is involved with cell adhesion in epithelial tissues and may be involved in wound repair.42 CCL25 and CD36 are particularly interesting as potential efficacy markers in IBD. Both are expressed by M2 macrophages associated with resolving inflammation. CCL25 is required for protection against chronic colitis in animal models.43 CD36 is required, together with lipolysis, for activation of M2 pro-resolution macrophages.44 Together, these markers may reflect the repair of intestinal tissue damage in IBD.

We identified three miRNAs that are responsive to both drugs and are known to be induced by inflammatory signaling. Notable among these is miR-146a, which is elevated in several inflammatory diseases and is induced by NF-κB in immune and muscle cells.13, 45, 46, 47 Interestingly, miR-146a (on chromosome 5) has both acute anti-inflammatory affects45 and chronic pro-inflammatory effects,48 and it is proposed that these contrasting effects may help in the staging of the inflammation/resolution process.49 The miR-146 family also includes miR-146b (on chromosome 10), which we find is affected by both treatments as well. These two miRNAs have shared gene targets, although timing of their expression may differ. A treatment response of this miR-146 family is consistent with studies in muscular dystrophy, where we find both prednisone and a novel dissociative steroid (VBP15) reduce TNFα-mediated induction of miR-146b and miR-146a.13, 50 Though less studied, miR-320a is linked to inflammatory disease as well. In colon biopsies from adults with UC, reduced miR-320a is associated with reduced inflammation.51 Together, measuring levels of these miRNAs could help assess inflammatory disease, as well as therapeutic response.

The pharmacodynamic biomarkers identified here hold potential for improving clinical care, and for streamlining development of new treatments. However, there are several limitations to our study. This is an exploratory, proof-of-concept study with limited patient numbers, variable sample timing, and heterogeneous patient populations. Because our statistical approach did not adjust for multiple comparisons, there is potential for type II error and false discovery. Further studies are necessary to replicate these findings, and to develop these markers as surrogate outcome measures. Summary data have been included in the Supplementary Data section.

Moving forward, a prospective study with more acute and less-variable blood sampling, hours or days after treatment, will define which biomarkers show the earliest responses to treatment, as well as validate biomarker discovery. Acutely responsive biomarkers should then be bridged to objective measures of intestinal inflammation and downstream clinical outcomes, with larger numbers of pediatric IBD patients followed out over a longer-term outcome period. This subset of biomarkers could then be used as outcome measures in drug development for dose finding studies (Phase 2a), and as surrogate biochemical outcome measures to support efficacy (Phase 2b or Phase 3 studies). In addition to biologics and small molecule inhibitors for IBD therapy, novel anti-inflammatory drugs with improved safety profiles are in development for IBD and other chronic inflammatory disorders.50, 52 Based on the successes of this pilot and feasibility study, drug-specific responses to treatment can be measured using specific serum biomarkers. Unanswered questions about the most clinically appropriate biomarkers to track various components of a complex disease like IBD (for example, the type and degree of the inflammatory process, and the state and activity of the healing process) remain. The time-line of the responses, the sensitivity and specificity of response over time compared to established (invasive) clinical measures, cost, and other issues must be addressed.

Study Highlights

Guarantor of the article: Laurie S. Conklin, MD.

Specific author contributions: Heier, Conklin, Hathout, Fiorillo, Damsker, and Hoffman contributed to the study concept and design. Heier, Chaisson, Hathout, and Conklin acquired the data. Gordish-Dressman performed statistical analysis. Heier and Conklin drafted the manuscript. Hoffman and Fiorillo offered critical revision for intellectual content. Funding was obtained by Conklin, Damsker, Heier, and Hoffman.

Financial support: This work was supported by the following National Institution of Health grants: National Center for Rehabilitation Medicine pilot grant R24HD050846, Research Program Projects and Centers P50AR060836, U54HD071601 Small Business Technology Transfer (STTR) Grant 1R41DK102235, Clinical and Translational Science Institute at Children's National UL1TR000075, NIH Award Number UL1RR031988, and the NIH Pathway to Independence Award K99HL130035. Work was also supported by a Sheikh Zayed Institute for Surgical Innovation pilot grant, and The Clark Charitable Foundation.

Potential competing interests: None.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on the Clinical and Translational Gastroenterology website (http://www.nature.com/ctg)

Supplementary Material

References

- Shah SC, Colombel JF, Sands BE et al. Mucosal healing is associated with improved long-term outcomes of patients with ulcerative colitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016; 14: 1245–1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah SC, Colombel JF, Sands BE et al. Systematic review with meta-analysis: mucosal healing is associated with improved long-term outcomes in Crohn's disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2016; 43: 317–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peyrin-Biroulet L, Sandborn W, Sands BE et al. Selecting therapeutic targets in inflammatory bowel disease (STRIDE): determining therapeutic goals for treat-to-target. Am J Gastroenterol 2015; 110: 1324–1338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner D, Levine A, Walters TD et al. Which PCDAI version best reflects intestinal inflammation in pediatric Crohn's disease? J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2016. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hathout Y, Conklin LS, Seol H et al. Serum pharmacodynamic biomarkers for chronic corticosteroid treatment of children. Sci Rep 2016; 6: 31727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sands BE. Biomarkers of inflammation in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology 2015; 149: 1275–1285 e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matalon S, Elad H, Brazowski E et al. Serum alpha-1 antitrypsin: a noninvasive marker of pouchitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2015; 21: 589–595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soendergaard C, Nielsen OH, Seidelin JB et al. Alpha-1 antitrypsin and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor as serum biomarkers of disease severity in ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2015; 21: 1077–1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahm AM, Thayu M, Hand NJ et al. Circulating microRNA is a biomarker of pediatric Crohn disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2011; 53: 26–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu F, Guo NJ, Tian H et al. Peripheral blood microRNAs distinguish active ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2011; 17: 241–250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold L, Walker JJ, Wilcox SK et al. Advances in human proteomics at high scale with the SOMAscan proteomics platform. Nat Biotechnol 2012; 29: 543–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hathout Y, Brody E, Clemens PR et al. Large-scale serum protein biomarker discovery in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2015; 112: 7153–7158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiorillo AA, Heier CR, Novak JS et al. TNF-alpha-induced microRNAs control dystrophin expression in Becker muscular dystrophy. Cell Rep 2015; 12: 1678–1690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C, Ridzon DA, Broomer AJ et al. Real-time quantification of microRNAs by stem-loop RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res 2005; 33: e179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandesompele J, De Preter K, Pattyn F et al. Accurate normalization of real-time quantitative RT-PCR data by geometric averaging of multiple internal control genes. Genome Biol 2002; 3: RESEARCH0034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rieu I, Powers SJ. Real-time quantitative RT-PCR: design, calculations, and statistics. Plant Cell 2009; 21: 1031–1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent WJ, Sugnet CW, Furey TS et al. The human genome browser at UCSC. Genome Res 2002; 12: 996–1006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Zhuang J, Iyer S et al. Sequence features and chromatin structure around the genomic regions bound by 119 human transcription factors. Genome Res 2012; 22: 1798–1812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbloom KR, Armstrong J, Barber GP et al. The UCSC Genome Browser database: 2015 update. Nucleic Acids Res 2015; 43: D670–D681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathelier A, Zhao X, Zhang AW et al. JASPAR 2014: an extensively expanded and updated open-access database of transcription factor binding profiles. Nucleic Acids Res 2014; 42: D142–D147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Shmuel A, Shvab A, Gavert N et al. Global analysis of L1-transcriptomes identified IGFBP-2 as a target of ezrin and NF-kappaB signaling that promotes colon cancer progression. Oncogene 2013; 32: 3220–3230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang CH, Nystrom GJ, Frost RA. Regulation of IGF binding protein-1 in hep G2 cells by cytokines and reactive oxygen species. Am J Physiol 1999; 276: G719–G727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez FO, Gordon S, Locati M et al. Transcriptional profiling of the human monocyte-to-macrophage differentiation and polarization: new molecules and patterns of gene expression. J Immunol 2006; 177: 7303–7311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin YH, Lee GW, Son KN et al. Promoter analysis of human CC chemokine CCL23 gene in U937 monocytoid cells. Biochim Biophys Acta 2007; 1769: 204–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh AK, Battu A, Mohareer K et al. Transcription of human resistin gene involves an interaction of Sp1 with peroxisome proliferator-activating receptor gamma (PPARgamma). PLoS One 2010; 5: e9912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeyda M, Gollinger K, Kriehuber E et al. Newly identified adipose tissue macrophage populations in obesity with distinct chemokine and chemokine receptor expression. Int J Obes (Lond) 2010; 34: 1684–1694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin AD, Wildenberg ME, van den Brink GR. Mechanism of action of Anti-TNF therapy in inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis 2016; 10: 989–997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Burg B, Liden J, Okret S et al. Nuclear factor-kappa B repression in antiinflammation and immunosuppression by glucocorticoids. Trends Endocrinol Metab 1997; 8: 152–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truss M, Beato M. Steroid hormone receptors: interaction with deoxyribonucleic acid and transcription factors. Endocr Rev 1993; 14: 459–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergin DA, Reeves EP, Meleady P et al. alpha-1 Antitrypsin regulates human neutrophil chemotaxis induced by soluble immune complexes and IL-8. J Clin Invest 2010; 120: 4236–4250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozeri E, Mizrahi M, Shahaf G et al. alpha-1 antitrypsin promotes semimature, IL-10-producing and readily migrating tolerogenic dendritic cells. J Immunol 2012; 189: 146–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray A, Gao X, Ray BK. Role of a distal enhancer containing a functional NF-kappa B-binding site in lipopolysaccharide-induced expression of a novel alpha 1-antitrypsin gene. J Biol Chem 1995; 270: 29201–29208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rioja I, Hughes FJ, Sharp CH et al. Potential novel biomarkers of disease activity in rheumatoid arthritis patients: CXCL13, CCL23, transforming growth factor alpha, tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily member 9, and macrophage colony-stimulating factor. Arthritis Rheum 2008; 58: 2257–2267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh UP, Singh NP, Murphy EA et al. Chemokine and cytokine levels in inflammatory bowel disease patients. Cytokine 2016; 77: 44–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Kim YS, Ko J. CK beta 8/CCL23 induces cell migration via the Gi/Go protein/PLC/PKC delta/NF-kappa B and is involved in inflammatory responses. Life Sci 2010; 86: 300–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaser S, Kaser A, Sandhofer A et al. Resistin messenger-RNA expression is increased by proinflammatory cytokines in vitro. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2003; 309: 286–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasayama D, Hori H, Nakamura S et al. Increased protein and mRNA expression of resistin after dexamethasone administration. Horm Metab Res 2015; 47: 433–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka N, Kusunoki N, Kusunoki Y et al. Resistin is associated with the inflammation process in patients with systemic autoimmune diseases undergoing glucocorticoid therapy: comparison with leptin and adiponectin. Mod Rheumatol 2013; 23: 8–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eivindson M, Gronbaek H, Flyvbjerg A et al. The insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-system in active ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease: relations to disease activity and corticosteroid treatment. Growth Horm IGF Res 2007; 17: 33–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linker RA, Maurer M, Gaupp S et al. CNTF is a major protective factor in demyelinating CNS disease: a neurotrophic cytokine as modulator in neuroinflammation. Nat Med 2002; 8: 620–624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sendtner M, Schmalbruch H, Stockli KA et al. Ciliary neurotrophic factor prevents degeneration of motor neurons in mouse mutant progressive motor neuronopathy. Nature 1992; 358: 502–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tinkle CL, Lechler T, Pasolli HA et al. Conditional targeting of E-cadherin in skin: insights into hyperproliferative and degenerative responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2004; 101: 552–557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wurbel MA, Le Bras S, Ibourk M et al. CCL25/CCR9 interactions are not essential for colitis development but are required for innate immune cell protection from chronic experimental murine colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2014; 20: 1165–1176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang SC, Everts B, Ivanova Y et al. Cell-intrinsic lysosomal lipolysis is essential for alternative activation of macrophages. Nat Immunol 2014; 15: 846–855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taganov KD, Boldin MP, Chang KJ et al. NF-kappaB-dependent induction of microRNA miR-146, an inhibitor targeted to signaling proteins of innate immune responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2006; 103: 12481–12486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg I, Alexander MS, Kunkel LM. miRNAS in normal and diseased skeletal muscle. J Cell Mol Med 2009; 13: 2–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olivieri F, Lazzarini R, Recchioni R et al. MiR-146a as marker of senescence-associated pro-inflammatory status in cells involved in vascular remodelling. Age (Dordr) 2013; 35: 1157–1172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghorpade DS, Sinha AY, Holla S et al. NOD2-nitric oxide-responsive microRNA-146a activates Sonic hedgehog signaling to orchestrate inflammatory responses in murine model of inflammatory bowel disease. J Biol Chem 2013; 288: 33037–33048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao JL, Rao DS, Boldin MP et al. NF-kappaB dysregulation in microRNA-146a-deficient mice drives the development of myeloid malignancies. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2011; 108: 9184–9189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heier CR, Damsker JM, Yu Q et al. VBP15, a novel anti-inflammatory and membrane-stabilizer, improves muscular dystrophy without side effects. EMBO Mol Med 2013; 5: 1569–1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fasseu M, Treton X, Guichard C et al. Identification of restricted subsets of mature microRNA abnormally expressed in inactive colonic mucosa of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. PLoS One 2010; 5: pii: e13160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damsker JM, Conklin LS, Sadri S et al. VBP15, a novel dissociative steroid compound, reduces NFκB-induced expression of inflammatory cytokines in vitro and symptoms of murine trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid-induced colitis. Inflamm Res 2016; 65: 737–743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine A, Griffiths A, Markowitz J et al. Pediatric modification of the Montreal classification for inflammatory bowel disease: the Paris classification. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2011; 17: 1314–1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.