Abstract

Introduction:

Paget’s disease of bone (PDB) is a disease of elderly characterized by disorganized bone remodeling. Development of secondary neoplasm in PDB is a known but rare phenomenon. Development of giant cell tumor in PDB (GCT-PDB) is extremely rare, and little is known about its etiopathogenesis and management. We present a case report of such a development with a review of the literature and the role of various new modalities of treatment available in the management of this rare condition.

Case Report:

A 40-year-old gentleman presented with back pain and on evaluation was diagnosed as a case of polyostotic PDB. He was treated with intravenous bisphosphonates, calcium, and vitamin D supplements. After an asymptomatic period of 3-year, he presented with a gluteal mass involving ilium and sacrum which was confirmed as GCT on biopsy. Serial angioembolization was attempted but mass progressed, so surgery performed with excision and curettage of the lesion. He presented with a local recurrence 2 years later with a large soft tissue component. He was started on denosumab, RANKL inhibitor, with the aim to downstage the lesion. The patient showed a good response after 6 doses with reduction in soft tissue mass followed by which he underwent surgery with partial T-1 internal hemipelvectomy and curettage of sacrum. Currently, the patient is asymptomatic at a follow-up of 15 months.

Conclusion:

GCT-PDB is a rare phenomenon occurring mainly in polyostotic PDB and is associated with more severe manifestations of the disease. The management is challenging and requires multimodality management. Pharmacological agents include use of bisphosphonates and RANK ligand inhibitor - denosumab. Although surgery is the mainstay of treatment for GCT, other modalities of treatment such as RANK ligand inhibitors (denosumab), selective arterial embolization, or radiation therapy has to be used for inoperable cases or where surgery would be functionally too morbid, especially in cases of GCT-PDB where the disease affects more commonly the axial skeleton.

Keywords: Giant cell tumor, Paget’s disease, denosumab

What to Learn from this Article?

Recent advances in the management of GCT developing in Paget’s disease of bone.

Introduction

Paget’s disease is a disease of elderly seen commonly after the fifth decade of life characterized by remodeling of bone in a disorganized manner. Development of primary bone neoplasm is a rare but is known complication of Paget’s disease of bone (PDB). Long-term evolution of Paget’s disease increases the risk of various malignant tumors such as osteosarcoma, fibrosarcoma, chondrosarcoma, malignant fibrous histiocytoma, and very rarely locally aggressive tumor-like giant cell tumor (GCT) [1]. The reported cases of GCT complicating Paget’s occur mainly in polyostotic disease [2]. In view of its rarity, there is only modest information available about the etiology and management of GCT-PDB. In addition, newer developments in the management of both these disorders have enabled new avenues for combined multimodal management in this rare coexistence. We present a case of GCT developing in the background of polyostotic PDB. We also discuss the mechanism of development and multimodality treatment available for the management in such an uncommon situation.

Case Report

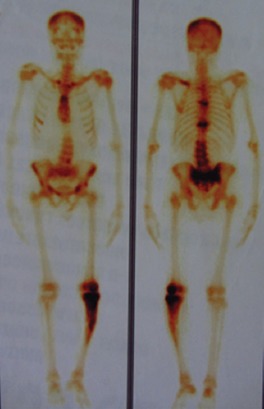

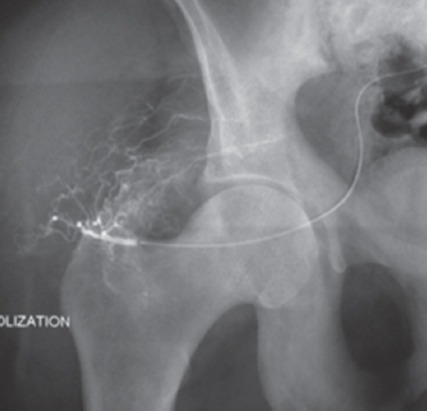

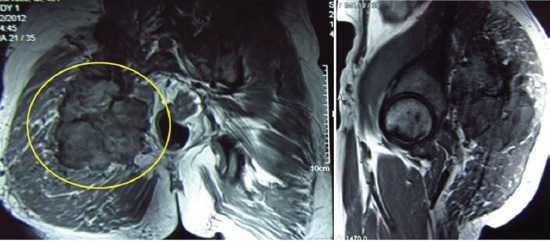

A 40-year-old gentleman presented with low backache of 5 years duration. He was evaluated clinically and radiologically. A diagnosis of PDB was made. Bone scan revealed multiple site involvement (skull, sternum, dorsal and lumbar, pelvis, ribs, femur, and tibia) (Fig. 1, 2, 3, 4). Bone biopsy from the iliac region revealed numerous multinucleated giant cells with the haphazard new bone formation and diagnosis of polyostotic Paget’s disease was confirmed. The patient was treated with intravenous (IV) bisphosphonate every 3 weeks (pamidronate 60 mg IV infusion) with vitamin D and calcium supplement at another institution. He was apparently alright for 3 years when he noticed a lump in the right gluteal region. It was associated with dull aching localized pain. Radiographs revealed a lytic lesion in right posterior ilium and a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the pelvis showed a large lesion with an extraosseous soft tissue component involving the iliac bone and adjacent sacral ala. Blood investigations showed an elevated serum alkaline phosphatase. Computed tomography-guided trucut biopsy from gluteal mass was diagnosed as GCT. Serial angioembolizations (Fig. 5) were attempted with intent to control the disease without surgery owing to the complex anatomy and associated morbidity of surgery, but the mass progressed in size. A decision for surgical excision was taken. Excision of soft tissue mass with curettage and cementation of the right sacroiliac component of the lesion was done. The final histopathology report confirmed GCT in case of PDB. 2 years after the surgery, he presented with a large local recurrence involving the posterior ilium and sacral ala. The recurrence was confirmed with a repeat biopsy. He was started on denosumab, a monoclonal RANK ligand inhibitor in an attempt to downstage the lesion and thus reduce the morbidity of surgery. Denosumab was administered at a dose of 120 mg subcutaneously at monthly intervals with loading doses at day 1, 8, and 15. A repeat MRI evaluation, after 6 injections of denosumab, revealed a good response with shrinkage of the soft tissue mass. He then underwent partial Type-1 internal hemipelvectomy and curettage of the sacral lesion (Fig. 6, 7, 8, 9, 10). At a 15 months follow-up, the patient is asymptomatic and disease-free.

Figure 1.

Polyostotic Paget’s disease involving spine.

Figure 2.

Tibia involved.

Figure 3.

Pelvis.

Figure 4.

Bone scan showing multiple bony involvement in Paget’s disease of bone.

Figure 5.

Angioembolization.

Figure 6.

Giant cell tumor with soft tissue component (predenosumab).

Figure 7.

Post denosumab shows shrinkage of soft tissue mass.

Figure 8.

Recurrence post curettage with cement in situ.

Figure 9.

T-1 internal hemipelvectomy and curettage.

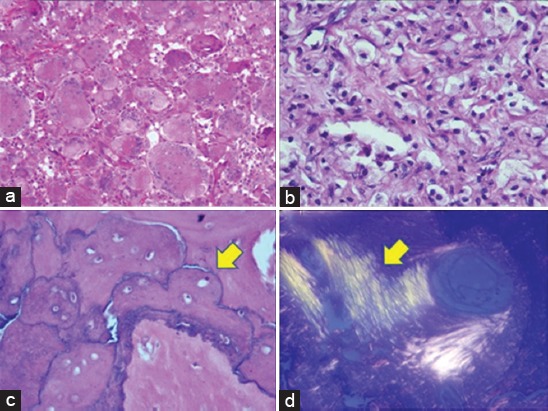

Figure 10.

Histopathology. (a) Initial biopsy showing classical features of a giant cell tumor, including uniform sprinkling of osteoclast-like giant cells with intervening mononuclear stromal cells. Hematoxylin and eosin (H and E) staining ×200, (b) sections from post denosumab-treated specimen displaying replacement by foamy histiocytes and lymphocytes. H and E staining ×400, (c) section from host bone displaying “jigsaw puzzle”- like or mosaic pattern of lamellar bone, pathognomonic of Paget’s disease. One of the several thickened mosaic cement lines marked with arrowhead. H and E staining ×200, (d) disorganized collagen fibers arranged in several directions rather than uniform (arrowhead), seen under polarized light. H and E, ×200.

Discussion

Inspite of a reported increased incidence of GCT of bone in the Asian population, most of the cases of GCT-PBD have been reported in Caucasians. This may be explained by the fact that the incidence of PDB is higher in western population as compared to Asians. Available data also suggested a significant prevalence of familial GCT occurring in PDB in Italy region. A systematic review [3] was conducted to identify cases of CGT occurring in PDB patients (PROSPERO database registration number: CRD42014007030). The analysis revealed some unique characteristic of GCT developing in Paget’s disease. The majority of ethnicity in this study was Caucasians of European ancestry 82% and around 8% were Asian.

| Characteristics | PDB with GCT | PDB | GCT |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male: Female | 2.1 | 1.2 | F>M |

| Age of onset | >50 | >60 | 20 |

| Prevalence of polyostotic disease | 93% | 63% | Rare |

| Cardiovascular complications | More | Less | NA |

| Average number of affected sites | 6.1±2.9 | 2.34±1.6 | Single location in epiphysis of mature skeleton |

| Mortality rate (5 years) | 50% | 0-5% | Rarely due to disease |

| Response to antiresorptive therapy (bisphosphonates) | Poor | Good | Surgery is standard of treatment |

| Alkaline phosphatase | Elevated in almost 100% suggestive of active PDB | Elevated in active PDB | Normal |

PDB: Paget’s disease of bone, GCT: Giant cell tumor

GCT in PDB more commonly involves the craniofacial bones followed by pelvis and spine as compared to GCT which commonly occurs at an epiphyseal location.

The understanding of genetics and pathophysiology of GCT has considerably increased since the discovery of RANK/RANK-L (receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappa B ligand) pathway which is an important osteoclastic differentiating factor. Osteoblasts and stromal stem cells express RANKL, which binds to its receptor RANK, on the surface of osteoclasts and their precursors. This regulates the differentiation of precursors into multinucleated osteoclasts. Studies have shown that RANKL is overexpressed by stromal cells in GCT tissue. These stromal cells are the neoplastic mononuclear cells in GCT, and it is postulated that the molecular signals from these stromal cells promote the formation of multinucleated osteoclast-like cells. The multinucleated giant cells cause the osteolysis. The pathogenesis of PDB involves mutations/polymorphisms identified in genes TNFRSF11A encoding RANK, TNFRSF11B encoding osteoprotegerin, Valosin-containing protein encoding p97, and SQSTM1 encoding p62 play a role in the RANK-NFKB signaling pathway [4, 5].

Thus, RANK/RANKL pathway seems to be an interlinking pathway in the development of GCT in Paget’s disease. However, how GCT may develop in PDB is not yet clearly established.

Multimodality management in GCT-PDB

GCT-PDB cases should be treated on the same principles as that of GCT. A thorough clinical and hematological evaluation is must understand both the pathologies. Surgery is the standard of treatment in GCT, which may be either function preserving curettage or more morbid procedure like resection. Traditionally, bisphosphonates have been used in the management of surgically nonresectable GCT either alone or in combination with angioembolization. This leads to induction of osteoclasts apoptosis leading to decreased bone restoration and bone healing. Similarly, bisphosphonates have also been used as a drug of choice for the management of and are also the treatment of choice in PDB.

Introduction of newer agents such as denosumab [6, 7], a human monoclonal antibody, has shown early promising results in managing the GCT at difficult sites. Denosumab inhibits the development of osteoclasts and their activity thereby reducing bone resorption and increase bone density and shrinks the tumor mass. Although its use has been popularized in reducing the skeletal-related events in some carcinomas such as breast and prostrate carcinoma, it is proving to be effective in controlling the growth of axial GCT where resection may be really morbid [8]. Literature search has shown cases where denosumab is used as a therapeutic agent targeting the pathophysiology in PDB [9]. Although currently not included as a standard of care in PDB, expected to become one of the potential therapeutic agents in the future. The duration of denosumab therapy is still a matter of debate, but complete cessation of therapy has seen resurgence of disease in most of the cases. Histopathological studies have shown complete apoptosis of multinucleate giant cells, but stromal cells do show resistance to its treatment and are considered responsible for the recurrence of the disease. This modality may be combined with arterial embolization [10] to have effective disease control at axial sites. For refractive cases, radiotherapy [11] can be tried in carefully selected cases.

Conclusion

GCT developing in the background of Paget’s disease is a rare occurrence which is commonly seen in polyostotic PDB. GCT-PDB is associated with more severe manifestations of the disease with reduced life expectancy. Various modalities of treatment can be used depending on the individual case. Pharmacological agents include the use of bisphosphonates and RANK ligand inhibitors. Although surgery is the mainstay of treatment for GCT, denosumab, selective arterial embolization, or radiation therapy has to be used for inoperable cases or where surgery would be functionally too morbid, especially in cases of GCT-PDB where the disease affects more commonly the axial skeleton.

Clinical Message.

Management of GCT-PDB is challenging and requires multimodality management. Surgery is the mainstay of treatment, but one should be aware of all the armamentarium available like bisphosphonates, RANK ligand inhibitor, angioembolization, and radiation therapy to downstage the lesion facilitating surgery or as a definitive modality of treatment in inoperable cases. The recent advances have led to successful cure and lesser morbidity in the treatment of this rare condition.

Biography

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: Nil

Source of Support: None

References

- 1.Roodman GD. Studies in Paget’s disease and their relevance to oncology. Semin Oncol. 2001;28(4 Suppl 11):15–21. doi: 10.1016/s0093-7754(01)90227-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoch B, Hermann G, Klein MJ, Abdelwahab IF, Springfield D. Giant cell tumor complicating Paget disease of long bone. Skeletal Radiol. 2007;36(10):973–978. doi: 10.1007/s00256-007-0310-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rendina D, De Filippo G, Ralston SH, Merlotti D, Gianfrancesco F, Esposito T, et al. Clinical characteristics and evolution of giant cell tumor occurring in Paget’s disease of bone. J Bone Miner Res. 2015;30(2):257–263. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kanis JA. Pathophysiology and Treatment of Paget’s Disease of Bone. 2nd ed. London, United Kingdom: Martin Dunitz; 1998. p. 310. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boyce BF, Xing L. The RANKL/RANK/OPG pathway. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2007;5(3):98–104. doi: 10.1007/s11914-007-0024-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Branstetter DG, Nelson SD, Manivel JC, Blay JY, Chawla S, Thomas DM, et al. Denosumab induces tumor reduction and bone formation in patients with giant-cell tumor of bone. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18(16):4415–4424. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-0578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rutkowski P, Ferrari S, Grimer RJ, Stalley PD, Dijkstra SP, Pienkowski A, et al. Surgical downstaging in an open-label phase II trial of denosumab in patients with giant cell tumor of bone. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22(9):2860–2868. doi: 10.1245/s10434-015-4634-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mattei TA, Ramos E, Rehman AA, Shaw A, Patel SR, Mendel E. Sustained long-term complete regression of a giant cell tumor of the spine after treatment with denosumab. Spine J. 2014;14(7):e15–e21. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2014.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hirao M, Hashimoto J. Denosumab as the potent therapeutic agent against Paget’s disease of bone. Clin Calcium. 2011;21(8):1231–1238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hosalkar HS, Jones KJ, King JJ, Lackman RD. Serial arterial embolization for large sacral giant-cell tumors:Mid- to long-term results. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2007;32(10):1107–1115. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000261558.94247.8d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feigenberg SJ, Marcus RB, Jr, Zlotecki RA, Scarborough MT, Berrey BH, Enneking WF. Radiation therapy for giant cell tumors of bone. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2003;411:207–216. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000069890.31220.b4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]