Abstract

Sepsis remains a major clinical problem with high morbidity and mortality. As new inflammatory mediators are characterized, it is important to understand their roles in sepsis. Interleukin 33 (IL-33) is a recently described member of the IL-1 family that is widely expressed in cells of barrier tissues. Upon tissue damage, IL-33 is released as an alarmin and activates various types of cells of both the innate and adaptive immune system through binding to the ST2/IL-1 receptor accessory protein complex. IL-33 has apparent pleiotropic functions in many disease models, with its actions strongly shaped by the local microenvironment. Recent studies have established a role for the IL-33-ST2 axis in the initiation and perpetuation of inflammation during endotoxemia, but its roles in sepsis appear to be organism and model dependent. In this review, we focus on the recent advances in understanding the role of the IL-33/ST2 axis in sepsis.

Keywords: Sepsis, Interleukin-33; ST2

Background

Sepsis remains a leading cause of mortality in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) [1]. Accumulating evidence indicates that the IL-33-ST2 axis is involved in the initiation and progression of inflammatory diseases, including sepsis [2–5]. In this review, we provide an update on recent advances on IL-33-mediated immunoregulation in sepsis.

Definition and epidemiology of sepsis

Sepsis is generally viewed as a condition of overwhelming systemic inflammation in response to an infection that can lead to multiple organ dysfunction [1]. Sepsis is now defined as life-threatening organ dysfunction caused by a dysregulated host response to infection [6], which replaces the term “severe sepsis” [7]. Septic shock occurs when sepsis is complicated by profound circulatory, cellular, and metabolic abnormalities, with a greater risk of mortality than with sepsis alone [6]. The number of cases of severe sepsis is on the rise and now comprises approximately 10–14% of admissions in intensive care units [8–10]. In the United States, the average annual age-adjusted incidence of sepsis is estimated to range between 300 and 1000 cases per 100,000 persons [11].

Sepsis is a leading cause of mortality in the ICU worldwide [1, 12]. Although significant advances in intensive care treatment and organ support have improved outcomes [13, 14], severe sepsis (previous definition) remains associated with mortality rates of 25–30% that increase to 40–50% when septic shock is present [15]. Mortality rates are directly related to the number of organs failing and contributory factors include disseminated intravascular coagulation, derangements of endocrine systems and/or energy metabolism [16]. The prognosis is worse in the elderly, immunocompromised, and critically ill patients [16].

Pathophysiology of sepsis

Sepsis develops when the host inflammatory response to an infection is exaggerated and subsequently dysregulated [16, 17]. Proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory responses comprise two parallel and overlapping responses during sepsis progression. Excessive inflammation, or sustained immune suppression, is highly correlated to sepsis outcomes [8, 16].

The host response to pathogens is mediated through both innate and adaptive immune systems [7]. The innate immune response functions as the “first line of defense” by immediately responding to invading pathogens in the initiation of sepsis, while the adaptive immune system is comprised of highly specialized cells that respond in a more focused fashion to foreign antigens and are able to develop immunological memory to microbial antigens [7, 16, 18]. Engagement of pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) on both immune and non-immune cells is recognized as the fundamental molecular mechanism of sepsis pathophysiology [8, 16]. Upon pathogen invasion, Toll-like receptors (TLRs) and other PRRs initiate the immune response after the recognition of conserved motifs expressed by pathogens, named pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS), lipopeptides, lipoteichoic acid, flagellin, and bacterial DNA [16, 19–21]. TLRs also are triggered by endogenous danger signals, termed danger-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), which are released from the damaged host tissue after trauma or stress. Identified DAMPs include high mobility group box 1 (HMGB-1), mitochondrial DNA, and S100a proteins [8, 19, 22]. LPS, also known as endotoxin, is among the most potent of all the PAMP molecules [19]. The LPS-dependent TLR4 and caspase-11 (caspase-4/5 in humans) cascades leads to the upregulation of pro-inflammatory/anti-inflammatory mediator production, pyroptotic cell death, and immune dysfunction [16, 23–25].

It has been proposed that the initial hyperactivation of the immune response is followed or overlapped by a prolonged state of immunosuppression, which renders the host susceptible to nosocomial infections [7, 16]. These infections often involve multidrug-resistant bacterial, viral and fungal pathogens [16, 19] and are thought to play a dominant role in the pathogenesis of sepsis-induced multiple organ failure and death [7, 16, 19]. Sepsis-associated immune suppression is thought to result from immune effector cell apoptosis, endotoxin reprogramming, suppressed antigen presentation, increased expression of negative costimulatory molecules and the production of anti-inflammatory cytokines, including type 2 cytokines [16, 19].

A variety of immune cells function differently as sepsis progresses. Macrophages and other cells of the innate immune system release proinflammatory mediators such as IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α, IFN-γ and monocyte chemoattractant protein (MCP)-1 [7, 26–28]. Neutrophils become activated and release the proinflammatory mediators myeloperoxidase (MPO) and proteases [29]. Host cells can also undergo pyroptosis and release large quantities of IL-1α, HMGB-1, and eicosanoids [30–32]. Neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) released by polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMNs) are important for anti-microbial defenses but may also propagate inflammatory responses [33]. Th17 cells augment the proinflammatory responses by producing IL-17A, which promotes the production of IL-1β, TNF-α and IL-6 [34]. Macrophages and neutrophils also play immuno-regulatory roles by producing IL-10 and TGF-β [35]. The early upregulation of Th1 responses (characterized by TNF-α, IFN-γ and IL-12 production) gives way to a Th2-dominated response (characterized by IL-4, IL-5, IL-10 and IL-13 production). A shift in the balance from Th1 to Th2 cytokines can cause immune suppression as sepsis progresses [7, 36]. A small subset of CD4+ CD25+ Foxp3+ T cells, referred to as regulatory T cells (Tregs), are upregulated and release IL-10 and TGF-β, favoring Th2 cell proliferation, activation, and differentiation [37]. These cells, along with the upregulation of myeloid-derived suppressor cells and massive immune cell death, are also thought to contribute to the immunosuppressed state [38, 39].

However, our understanding of how inflammatory pathways are modulated to culminate in immune dysfunction during sepsis is far from complete. Likewise, the roles of more recently described immune mediators need to be incorporated into this evolving paradigm. One such mediator is interleukin-33 (IL-33) and its receptor ST2. In this review, we will discuss the current understanding of the role of IL-33 and its regulatory targets in the host response during sepsis.

Immunobiology of IL-33 and ST2

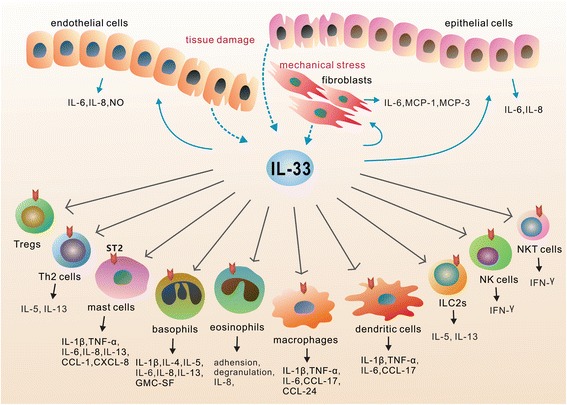

IL-33 was first discovered in 2003 as a nuclear factor from high endothelial venules [40]. In 2005, Schmitz et al. [41] identified IL-33 as a member of the IL-1 family and a ligand for the orphan receptor ST2 (also known as IL-1RL1). IL-33 is mainly produced by structural and lining cells, such as endothelial cells, epithelial cells and fibroblasts, that constitute the first line of host defense against pathogens (Fig. 1) [2, 42–44]. Rodent immune cells, such as macrophages and dendritic cells have been shown to produce IL-33 during allergic inflammation and infection [45–47]. Under homeostatic conditions, endogenous IL-33 is constitutively expressed in the nucleus of cells and can associate with chromatin by binding histones H2A/H2B, though its nuclear roles remain obscure [47, 48]. Full length IL-33 is bioactive, although it can also be processed by proteases (cathepsin G, elastase) into shorter hyperactive forms [47]. Upon tissue damage (necrotic cell death, cell stress) and/or mechanical injury, IL-33 expression increases and it is released into the extracellular space [47]. After release, IL-33 “sounds the alarm” in the immune system by targeting various immune cell types, including T cells, basophils, eosinophils, mast cells, innate lymphoid cells, dendritic cells and macrophages (Fig. 1) [2, 3, 49, 50]. IL-33 was thus proposed to act as an alarmin to sense damage and alert neighboring cells and tissues following infection or trauma and therefore has the potential to influence a broad range of diseases [3–5, 51].

Fig. 1.

Cellular sources and cellular targets of IL-33. IL-33 is released from endothelial cells, epithelial cells and fibroblasts in response to tissue damage and/or mechanical stress (indicated as dotted arrow). After release, IL-33 functions as an alarmin and activates various types of cells (indicated as solid arrow), including Th2 cells, Tregs, basophils, mast cells, eosinophils, macrophages, dendritic cells, innate lymphoid cells (ILC2s), NK cells and NKT cells. These cells respond to IL-33/ST2 signaling by producing both pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory mediators depending on the immune context in different tissues and diseases

The IL-33 receptor ST2, first identified in 1989, is a member of the IL-1 receptor (IL-1R) family [52]. Through alternative splicing, the ST2 gene encodes two major protein isoforms, a transmembrane full-length form ST2 (ST2 or ST2L) and a soluble, secreted form ST2 (sST2) [3, 50]. sST2 lacks transmembrane and intracellular domains and acts as a decoy receptor for IL-33 [3, 53]. With a nearly undetectable level in normal conditions, the serum concentration of sST2 is increased in patients with pathogenic inflammation, such as asthma [54], autoimmune diseases [55], idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis [56], heart failure [57], and transplant rejection [58]. Membrane-bound ST2 is the functional component for IL-33 signaling [3, 50]. It can be expressed on human and mice CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, group 2 innate lymphoid cells (ILC2s), mast cells, basophilic and eosinophilic granulocytes, monocytes, dendritic cells, NKT cells and mice NK cells [3, 59]. Recently, it was also reported to be expressed by endothelial cells [60, 61], epithelial cells [62] and fibroblasts [63], thus pointing to the potential importance of IL-33/ST2 signaling in various types of tissues during the pathophysiology of numerous diseases (Fig. 1).

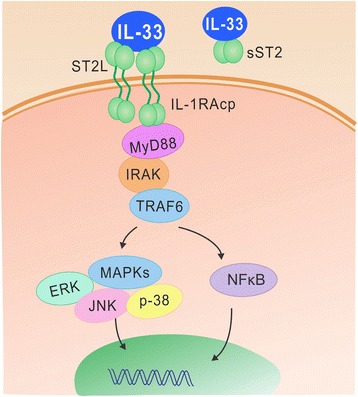

IL-33/ST2 signaling

IL-33 binds a heterodimeric receptor complex consisting of ST2 and IL-1R accessory protein (IL-1RAP) and induces the recruitment of myeloid differentiation primary response protein 88 (MyD88), IL-1R-associated kinase (IRAK)-1 and IRAK-4 to the receptor domain in the cytoplasmic region of ST2 (Fig. 2), leading to the activation of downstream signaling, including nuclear factor-kappaB (NF-κB) and MAP kinases (ERK, p38 and JNK) [3, 50]. This subsequently induces the production of various pro- or anti-inflammatory mediators such as IL-6, TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-5 and IL-13 (see below in detail) [3, 50]. IL-33 was proposed to be a multifunctional protein, with reported roles in driving both Th1 and Th2 immune responses depending on type of cells activated, the specific microenvironment and the immune context in different diseases [3, 4].

Fig. 2.

IL-33/ST2 signaling. The binding of IL-33 to ST2 results in the activation of IL-33 bioactivities via intracellular pathways, while sST2 acts as a decoy receptor for IL-33

Cellular targets of IL-33

Th1 and Th2 CD4+ T cells

The role of IL-33 was first reported in T cells [41]. Naive T cells respond to IL-33 by producing Th2-associated cytokines IL-4, IL-5 and IL-13 in vivo, leading to histopathological changes in the lungs and gastrointestinal tract [41]. IL-33 polarizes murine and human naive CD4+ T cells to produce IL-5, and promotes airway inflammation independent of IL-4 [64]. Recently, Villarreal et al. [65, 66] challenged the prevailing opinion that IL-33 strictly targets Th2 CD4+ T cells, as they show that IL-33 also has the potential to effect Th1 cell-mediated T cells. Both isoforms of IL-33 (proIL-33 and mtrIL-33) can function as immunoadjuvants to induce profound Th1 CD4+ and CD8+ T cell responses [65, 66].

Tregs

Tregs express ST2 and respond to IL-33 by the profound expansion in a ST2-dependent manner [67–69]. IL-33 mediates the Treg-dependent promotion of cardiac allograft survival [69]. IL-33-expanded Tregs protect recipients from acute graft-versus-host disease by controlling macrophage activation and preventing effector T cell accumulation [70]. The protective effects of IL-33-mediated Treg responses were also reported in muscle regeneration [71], hepatitis [72] and colitis [73, 74].

Mast cells, basophils and eosinophils

IL-33 is a potent inducer of pro-inflammatory mediators by mast cells [75–77]. IL-33 stimulates the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines (IL-6, IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-8, IL-13, CCL1 and CXCL8) from human mast cells [78], and synergizes with IgE to promote cytokine production [79, 80]. IL-2 production by IL-33-stimulated mast cells promotes Treg expansion, thus suppressing papain-induced airway eosinophilia [81].

Human basophils express high levels of ST2 receptor and respond to IL-33 with increased production of IL-1β, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-8, IL-13 and granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GMC-SF) [82]. IL-33 synergistically enhances IgE-mediated basophil degranulation [83, 84]. IL-33 potently induces eosinophil degranulation and production of IL-8 and superoxide anion [85], and also enhances eosinophil adhesion and increases eosinophil survival [85, 86].

Macrophages and dendritic cells

IL-33 enhances the LPS-induced secretion of TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β by mouse macrophages [87]. In the setting of allergic airway inflammation, IL-33 amplifies the IL-13-mediated polarization of alternatively activated macrophages and enhances their production of CCL17 and CCL24 [88]. Dendritic cells (DCs) are activated by IL-33 and drive a Th2-type response in allergic lung inflammation [89]. IL-33-activated DCs promote IL-5 and IL-13 production from naive lymphocytes [89, 90]. IL-33 can also activate DCs to produce IL-6, IL-1β, TNF, CCL17 [89] and to express increased levels of CD40, CD80, OX40L, CCR7, MHC-II and CD86 [90]. DCs secrete IL-2 in response to IL-33 stimulation and are required for IL-33-mediated in vitro and in vivo Treg expansion [91].

Group 2 innate lymphoid cells

Group 2 innate lymphoid cells (ILC2s, previously named natural helper cells, nuocytes, or Ih2 cells) were recently described as members of the ILC family, characterized by the expression of lymphoid markers and type 2 cytokines production, linking the innate and adaptive responses in type 2 immunity in various diseases [92, 93]. ILC2s constitutively express ST2 and respond rapidly to IL-33 with increased proliferation and cytokine production after an allergen challenge or helminth infection [94–97]. IL-33/ST2 signaling is required for IL-5 and IL-13 production from lung ILC2s and airway eosinophilia independent of adaptive immunity [98]. IL-33-dependent IL-5 and IL-13 production from ILC2s can also promote cutaneous wound healing, acting as an important link between the cutaneous epithelium and the immune system [99]. IL-33 protects against experimental cerebral malaria by driving the expansion of ILC2s and their production of IL-4, IL-5 and IL-13 [100] and is required for ILC2-derived IL-13- but not IL-4-driven Type 2 responses during hookworm infection [101]. It also mediates influenza-induced airway hyper-reactivity via an IL-33-ILC2-IL-13 axis [97].

CD8+ T cells, NK and NKT cells

Cytotoxic CD8+ T cells can also express ST2 and respond to IL-33. IL-33 synergizes with TCR and IL-12 to augment IFN-γ production from effecter CD8+ T cells [102]. IL-33 enhances the production of IFN-γ by both iNKT and NK cells via cooperation with IL-12 [103].

Endothelial cells, epithelial cells and fibroblasts

IL-33 regulates the activity of many nonimmune cells. Both epithelial cells and endothelial cells produce IL-6 and IL-8 in response to IL-33 [62]. IL-33 promotes nitric oxide production from endothelial cells via the ST2/TNF receptor-associated factor 6 (TRAF6)-Akt-eNOS signaling pathway, leading to enhanced angiogenesis and vascular permeability [61]. Murine fibroblasts respond to IL-33 by producing MCP-1, MCP-3 and IL-6 in a TRAF6-dependent manner [63].

The role of IL-33/ST2 in sepsis

Clinical data — serum sST2 levels in sepsis patients

Several studies have shown that IL-33 or sST2 levels are elevated in the circulation of patients with sepsis. Children have significantly higher serum levels of IL-33 and sST2 on the first day of sepsis, raising the possibility that sST2 levels may be useful in the diagnosis of childhood sepsis [104]. On admission [105] and within 24-48 hours of the diagnosis of sepsis [106], adults have significantly higher serum sST2 levels than healthy controls and demonstrate sustained increases in serum sST2 levels during the clinical course of sepsis [106]. Serum sST2 levels correlate with cardiac dysfunction [107], sepsis severity and mortality [106, 107]. In-hospital mortality was higher among patients with elevated serum concentrations of sST2 (above 35 ng/ml) [107]. Parenica et al. [108] concluded that sST2 levels are not a suitable prognostic marker for patients with sepsis shock because ST2 levels failed to predict three-month mortality following sepsis. However, serum concentrations of sST2 are significantly higher in patients with septic shock compared with cardiogenic shock at admission, suggesting the sST2 levels may be useful in identifying patients with sepsis as the etiology of shock in the early phases [108].

Experimental studies — role of IL-33/ST2 in endotoxemia

The role of the IL-33-ST2 axis has been extensively studied in experimental endotoxemia. Even before the identification of IL-33, it was demonstrated that the ST2 receptor functions as a negative regulator of TLR4 signaling and maintains LPS tolerance [109]. In these studies, ST2-deficient mice did not develop endotoxin tolerance [109]. Specifically, Liu et al. [110] found that ST2 also negatively regulates TLR2 signaling but is not required for bacterial lipoprotein-induced tolerance. A plausible explanation for these differences may lie in the unique signaling transduction and molecular mechanisms of TLR4-mediated tolerance (LPS tolerance) vs TLR2-mediated tolerance (BLP tolerance). Despite the implicated roles of ST2 in endotoxin tolerance, IL-33 triggering of ST2 failed to induce LPS desensitization but instead enhanced the LPS-induced proinflammatory cytokine production (IL-6, TNF-α and IL-1β) in mouse macrophages [111]. This effect is ST2 dependent, as it was not observed in ST2 knockout mice [111]. IL-33 treatment increases macrophage expression of the MD2/TLR-4 components of the LPS receptor as well as levels of the soluble form of CD14, and preferentially affects the MyD88-dependent pathway downstream of TLR-4 and TLR-2, which may explain the enhanced LPS responses of macrophages [111]. These conflicting results indicate distinct roles for IL-33 and ST2 in the pathogenesis of LPS responses. Oboki et al. [112] also found different immune responses between ST2-deficient mice and soluble ST2-Fc fusion protein-treated mice. Taken together, these studies show that the IL-33/ST2 pathway is activated during endotoxemia and plays regulatory roles at the level of endotoxin sensing and signaling. However, more work is required to understand the full range of IL-33 and ST2 actions as regulators or effectors during PAMP exposure.

Apart from the enhanced macrophage responses to LPS as mentioned above, other researchers also reported important roles for IL-33 in macrophage activation for host defenses and proinflammatory responses [113, 114]. IL-33 directly activated bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) by increasing their expression of MHC class I, MHC class II, CD80/CD86, and inducible NO synthase (iNOS) in a dose-dependent manner and augmented the LPS-induced expression of proinflammatory mediators (e.g., iNOS, IL-6 and TNF-α) in macrophages [113]. Ohno et al. [114] produced results in support of this concept by reporting that exogenous IL-33 potentiated LPS-induced IL-6 production by macrophages and that this effect was suppressed by the blockade of endogenous IL-33 by anti-IL-33 neutralizing antibodies.

In light of the role of IL-33 in LPS-induced proinflammatory responses, researchers have also explored the immunomodulatory functions of sST2, the decoy receptor of IL-33, in LPS-mediated inflammation [115–117]. sST2 treatment inhibited the production of LPS-induced proinflammatory cytokines (IL-6, IL-12 and TNF-α) from BMMs and negatively regulated the expression of TLR-4 and TLR-1 [115]. Consistent results were obtained in vivo after LPS challenge; sST2 administration significantly reduced LPS-mediated mortality and serum levels of IL-6, IL-12, and TNF-α [115]. sST2 down-regulates LPS-induced IL-6 production from a human monocytic leukemia cell line via the suppression of NF-κB binding to the IL-6 promoter [116], and sST2 can be internalized into dendritic cells and suppresses LPS signaling and cytokine production in human monocyte-derived dendritic cells without attenuating the LPS-induced dendritic cell maturation [117]. Conversely, the inhibition of endogenous ST2 through the administration of anti-ST2 antibody aggravated the toxic effects of LPS [115], suggesting distinct roles for IL-33 and ST2 signaling in LPS-induced responses.

The production of IL-33 in the lung was reported in airway inflammation [118] and virus infection [119]. In a mouse model of LPS-induced acute lung injury, the administration of engineered human adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells (hASCs) overexpressing murine sST2 led to the local suppression of IL-33 signaling and the reduced expression of IL-1β and IFN-γ in the lungs. This was associated with a substantial decrease in lung airspace inflammation, inflammatory cell infiltration and vascular leakage [120]. Yin et al. [121] found that sST2 reduces inflammatory cell infiltration and alveolar hemorrhage in the alveolar airspace and remarkably suppresses proinflammatory cytokine production (TNF-α, IL-6) and TLR-4 gene expression in lung tissues. Taken together, these in vivo studies show that IL-33 signaling can be proinflammatory in the lung during endotoxemia.

Experimental research — the role of IL-33/ST2 in infection models

Our understanding of the contributions of IL-33 and ST2 during infections is advancing; however, the roles appear to be time, tissue, and model dependent. For example, the effects of ST2 in sepsis were different depending on the model and study design. It was proposed that ST2 contributes to immune suppression during sepsis [122]. In a murine model of cecal ligation and puncture (CLP)-induced sepsis, ST2 deletion leads to improved survival and more efficient bacterial clearance in mice challenged with secondary pneumonia [122]. In contrast, ST2-deficient mice showed increased susceptibility to CLP-induced polymicrobial sepsis with increased mortality, impaired bacterial clearance and increased production of proinflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-6), when compared with their wild-type littermates [123]. This was associated with impaired bacterial uptake, phagocytosis, and killing by ST2-deficient phagocytes, which displayed defects in phagosome maturation, NADPH oxidase 2 (NOX2) activity and superoxide anion production in response to bacterial challenge [123]. When exposed to Streptococcus pneumoniae or Klebsiella pneumoniae, ST2-deficient blood leukocytes and splenocytes produced lower levels of cytokines and chemokines than wild-type cells [124]. ST2-deficient mice challenged with Streptococcus pneumoniae have lower bacterial loads in their spleens compared with their wide-type littermates [124].

Exogenous IL-33 was shown to be protective in murine models of CLP-induced sepsis. IL-33 treatment enhanced the neutrophil influx to the site of infection and thus led to more efficient bacterial clearance and reduced mortality in CLP-induced septic mice [125]. This effect was mediated by preserving CXCR2 expression on neutrophils. The chemokine receptor, CXCR2 has a central role in the recruitment of neutrophils and was down-regulated by TLR4 activation during sepsis. IL-33 reversed the down-regulation of CXCR2 and promoted neutrophil recruitment by repressing G protein-coupled receptor kinase-2 (GRK2) expression [125]. The administration of recombinant IL-33 1 h and 6 h after CLP enhanced bacterial clearance and improved the survival of septic mice [126]. At 24 h after CLP, IL-33 attenuated the severity of organ damage and decreased the serum levels of IL-6, IL-10, TNF-α and IFN-γ, the effect of which was likely to be the consequence of improved bacterial clearance [126]. In an acute Staphylococcus aureus peritoneal infection model, IL-33 administration facilitated neutrophil recruitment and bacterial clearance, with higher CXCL2 levels in the peritoneum than untreated mice [127]. Thus, one role for IL-33 appears to be supporting PMN-mediated bacterial clearance in the early phases of bacterial sepsis. There is also some suggestion that IL-33/ST2 may drive the delayed immunosuppression of sepsis. However, more studies are needed to draw this conclusion. We have recently shown that IL-33 can drive ILC2 activation and early IL-5-mediated PMN recruitment in the lung in the CLP model (manuscript submitted). This leads to enhanced early lung injury. Therefore, the cost of enhanced PMN infiltration mediated by IL-33 appears to be secondary, remote lung injury.

Conclusion

Similar to many immuno-regulatory pathways, the IL-33-ST2 axis plays diverse and context specific roles in sepsis (Table 1). These diverse roles arise, at least in part, through the variety of immune cells that can express ST2 and respond to IL-33. Much remains to be elucidated regarding the precise functions and underlying mechanism of the IL-33-ST2 signaling pathway in sepsis. As our understanding advances, it may be possible to target this pathway to promote antimicrobial defenses or to reduce secondary organ damage.

Table 1.

Roles of IL-33/ST2 in sepsis models

| Disease | Role of IL-33/ST2 | Referenced |

|---|---|---|

| Sepsis | Sepsis patients have higher levels of serum IL-33 and sST2 | [104–108] |

| Endotoxemia | ST2 negatively regulates TLR4 signaling and maintains LPS tolerance | [109] |

| Endotoxemia | ST2 negatively regulates TLR2 signaling, but is not required for BLP tolerance | [110] |

| Endotoxemia | IL-33 enhances LPS-induced proinflammatory mediators in mouse macrophages in a ST2-dependent manner | [111, 113, 114] |

| Endotoxemia | sST2 reduces LPS-mediated mortality and inhibits LPS-induced proinflammatory cytokines | [115–117] |

| Endotoxemia | sST2 reduces inflammatory cell infiltration and vascular leakage, and suppresses proinflammatory cytokine production in lung tissues | [120, 121] |

| Abdominal sepsis | ST2 deletion protects mice challenged with secondary pneumonia | [122] |

| Abdominal sepsis | ST2 deficiency increases the susceptibility to sepsis | [123] |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae infection | ST2 deficiency protects mice challenged with S. pneumonia | [124] |

| Abdominal sepsis | IL-33 enhances neutrophil recruitment and protects mice with more efficient bacterial clearance and improved survival | [125, 126] |

| Abdominal sepsis | IL-33 administration attenuates organ damage in the late phase of sepsis | [126] |

| Staphylococcus aureus infection | IL-33 administration facilitates neutrophil recruitment and bacterial clearance | [127] |

Acknowledgments

Funding

National Institutes of Health RO1-GM 044100.

National Institutes of Health RO1-GM 050441.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Authors’ contributions

HX performed the literature search and was a major contributor in the writing of the manuscript. TB, RH and HT provided suggestions and edited the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- BMDMs

Bone marrow-derived macrophages

- CLP

Cecal ligation and puncture

- DAMPs

Danger-associated molecular patterns

- DCs

Dendritic cells

- GMC-SF

Granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor

- GRK2

G protein-coupled receptor kinase-2

- hASCs

Human adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells

- HMGB-1

High mobility group box 1

- ICU

Intensive care unit

- IL-1R

IL-1 receptor

- IL-1RAP

IL-1R accessory protein

- IL-33

Interleukin-33

- ILC2s

Group 2 innate lymphoid cells

- iNOS

Inducible NO synthase

- IRAK

IL-1R-associated kinase

- LPS

Lipopolysaccharide

- MCP

Monocyte chemoattractant protein

- MPO

Myeloperoxidase

- MyD88

Myeloid differentiation primary response protein 88

- NETs

Neutrophil extracellular traps

- NF-κB

Nuclear factor-kappaB

- NOX2

NADPH oxidase 2

- PAMPs

Pathogen-associated molecular patterns

- PMNs

Polymorphonuclear neutrophils

- PRRs

Pattern recognition receptors

- TLRs

Toll-like receptors

- TRAF6

TNF receptor-associated factor 6

- Tregs

Regulatory T cells

Contributor Information

Hui Xu, Email: zybbda@126.com.

Heth R. Turnquist, Email: turnquisthr@upmc.edu

Rosemary Hoffman, Email: hoffmanr3@upmc.edu.

Timothy R. Billiar, Email: billiartr@upmc.edu

References

- 1.Lakshmikanth CL, Jacob SP, Chaithra VH, de Castro-Faria-Neto HC, Marathe GK. Sepsis: in search of cure. Inflamm Res. 2016;65:587–602. doi: 10.1007/s00011-016-0937-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liew FY, Pitman NI, McInnes IB. Disease-associated functions of IL-33: the new kid in the IL-1 family. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10:103–10. doi: 10.1038/nri2692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Milovanovic M, Volarevic V, Radosavljevic G, Jovanovic I, Pejnovic N, Arsenijevic N, et al. IL-33/ST2 axis in inflammation and immunopathology. Immunol Res. 2012;52:89–99. doi: 10.1007/s12026-012-8283-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kurowska-Stolarska M, Hueber A, Stolarski B, McInnes IB. Interleukin-33: a novel mediator with a role in distinct disease pathologies. J Intern Med. 2011;269:29–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2010.02316.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Palmer G, Gabay C. Interleukin-33 biology with potential insights into human diseases. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2011;7:321–9. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2011.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, Shankar-Hari M, Annane D, Bauer M, et al. The third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (Sepsis-3) JAMA. 2016;315:801–10. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.0287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Angus DC, van der Poll T. Severe sepsis and septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:840–51. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1208623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wiersinga WJ, Leopold SJ, Cranendonk DR, van der Poll T. Host innate immune responses to sepsis. Virulence. 2014;5:36–44. doi: 10.4161/viru.25436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gaieski DF, Edwards JM, Kallan MJ, Carr BG. Benchmarking the incidence and mortality of severe sepsis in the United States. Crit Care Med. 2013;41:1167–74. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31827c09f8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lagu T, Rothberg MB, Shieh MS, Pekow PS, Steingrub JS, Lindenauer PK. Hospitalizations, costs, and outcomes of severe sepsis in the United States 2003 to 2007. Crit Care Med. 2012;40:754–61. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318232db65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kempker JA. Martin GS2. The changing epidemiology and definitions of sepsis. Clin Chest Med. 2016;37:165–79. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2016.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cohen J, Vincent JL, Adhikari NK, Machado FR, Angus DC, Calandra T, et al. Sepsis: a roadmap for future research. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015;15:581–614. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)70112-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Seeley EJ, Bernard GR. Therapeutic targets in sepsis: past, present, and future. Clin Chest Med. 2016;37:181–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2016.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaukonen KM, Bailey M, Suzuki S, Pilcher D, Bellomo R. Mortality related to severe sepsis and septic shock among critically ill patients in Australia and New Zealand, 2000-2012. JAMA. 2014;311:1308–16. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.2637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vincent JL, Marshall JC, Namendys-Silva SA, François B, Martin-Loeches I, Lipman J, et al. Assessment of the worldwide burden of critical illness: the intensive care over nations (ICON) audit. Lancet Respir Med. 2014;2:380–6. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(14)70061-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schulte W, Bernhagen J, Bucala R. Cytokines in sepsis: potent immunoregulators and potential therapeutic targets--an updated view. Mediators Inflamm. 2013;2013:165974. doi: 10.1155/2013/165974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cohen J. The immunopathogenesis of sepsis. Nature. 2002;420:885–91. doi: 10.1038/nature01326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oberholzer A, Oberholzer C, Moldawer L. Sepsis syndromes: understanding the role of innate and acquired immunity. Shock. 2001;16:83–96. doi: 10.1097/00024382-200116020-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Opal SM. New perspectives on immunomodulatory therapy for bacteraemia and sepsis. Int J Antimicrob Ag. 2010;36(Suppl 2):S70–3. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2010.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van der Poll T, Opal SM. Host-pathogen interactions in sepsis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2008;8:32–43. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(07)70265-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kawai T, Akira S. The role of pattern-recognition receptors in innate immunity: update on Toll-like receptors. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:373–84. doi: 10.1038/ni.1863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Opal SM. The host response to endotoxin, anti-LPS strategies and the management of severe sepsis. Int J Med Microbiol. 2007;297:365–77. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2007.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stowe I, Lee B, Kayagaki N. Caspase-11: arming the guards against bacterial infection. Immunol Rev. 2015;265:75–84. doi: 10.1111/imr.12292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Akira S, Takeda K. Toll-like receptor signaling. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:499–511. doi: 10.1038/nri1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O'Neill LA. A critical role for citrate metabolism in LPS signalling. Biochem J. 2011;438:5–6. doi: 10.1042/BJ20111386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Opal SM, Huber CE. Bench-to-bedside review: Toll-like receptors and their role in septic shock. Crit Care. 2002;6:1–12. doi: 10.1186/cc1471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lakhani SA, Bogue CW. Toll-like receptor signaling in sepsis. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2003;15:278–82. doi: 10.1097/00008480-200306000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ramnath RD, Weing S, He M, Sun J, Zhang H, Bara MS, et al. Inflammatory mediators in sepsis: cytokines, chemokines, adhesion molecules and gases. J Organ Dysfunct. 2009;2:80–92. doi: 10.1080/17471060500435662. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hoesel LM, Neff TA, Neff SB, Younger JG, Olle EW, Gao H, et al. Harmful and protective roles of neutrophils in sepsis. Shock. 2005;24:40–7. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000170353.80318.d5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Laban-Guceva N, Bogoev M, Antova M. Serum concentrations of interleukin (IL-)1alpha, 1beta, 6 and tumor necrosis factor (TNF-) alpha in patients with thyroid eye disease (TED) Med Arh. 2007;61:203–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xu J, Jiang Y, Wang J, Shi X, Liu Q, Liu Z, et al. Macrophage endocytosis of high-mobility group box 1 triggers pyroptosis. Cell Death Differ. 2014;21:1229–39. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2014.40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.von Moltke J, Trinidad NJ, Moayeri M, Kintzer AF, Wang SB, van Rooijen N, et al. Rapid induction of inflammatory lipid mediators by the inflammasome in vivo. Nature. 2012;490:107–11. doi: 10.1038/nature11351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Meng W, Paunel-Görgülü A, Flohé S, Hoffmann A, Witte I, MacKenzie C, et al. Depletion of neutrophil extracellular traps in vivo results in hypersusceptibility to polymicrobial sepsis in mice. Crit Care. 2012;16:R137. doi: 10.1186/cc11442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weaver CT, Hatton RD, Mangan PR, Harrington LE. IL-17 family cytokines and the expanding diversity of effector T-cell lineages. Annu Rev Immunol. 2007;25:821–52. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Opal SM, DePalo VA. Anti-inflammatory cytokines. Chest. 2000;117:1162–72. doi: 10.1378/chest.117.4.1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rittirsch D, Flierl MA, Ward PA. Harmful molecular mechanisms in sepsis. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:776–87. doi: 10.1038/nri2402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Venet F, Chung CS, Monneret G, Huang X, Horner B, Garber M, et al. Regulatory T cell populations in sepsis and trauma. J Leukoc Biol. 2008;83:523–35. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0607371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cuenca AG, Delano MJ, Kelly-Scumpia KM, Moreno C, Scumpia PO, Laface DM, et al. A paradoxical role for myeloid-derived suppressor cells in sepsis and trauma. Mol Med. 2011;17:281–92. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2010.00178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hotchkiss RS, Nicholson DW. Apoptosis and caspases regulate death and inflammation in sepsis. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:813–22. doi: 10.1038/nri1943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Baekkevold ES, Roussigné M, Yamanaka T, Johansen FE, Jahnsen FL, Amalric F, et al. Molecular characterization of NF-HEV, a nuclear factor preferentially expressed in human high endothelial venules. Am J Pathol. 2003;163:69–79. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63631-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schmitz J, Owyang A, Oldham E, Song Y, Murphy E, McClanahan TK, et al. IL-33, an interleukin-1-like cytokine that signals via the IL-1 receptor-related protein ST2 and induces T helper type 2-associated cytokines. Immunity. 2005;23:479–90. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sanada S, Hakuno D, Higgins LJ, Schreiter ER, McKenzie AN, Lee RT. IL-33 and ST2 comprise a critical biomechanically induced and cardioprotective signaling system. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:1538–49. doi: 10.1172/JCI30634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Moussion C, Ortega N, Girard JP. The IL-1-like cytokine IL-33 is constitutively expressed in the nucleus of endothelial cells and epithelial cells in vivo: a novel ‘alarmin’? PLoS One. 2008;3:e3331. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Miller AM, Xu D, Asquith DL, Denby L, Li Y, Sattar N, et al. IL-33 reduces the development of atherosclerosis. J Exp Med. 2008;205:339–46. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tjota MY, Williams JW, Lu T, Clay BS, Byrd T, Hrusch CL, et al. IL-33-dependent induction of allergic lung inflammation by FcgammaRIII signaling. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:2287–97. doi: 10.1172/JCI63802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hardman CS, Panova V, McKenzie AN. IL-33 citrine reporter mice reveal the temporal and spatial expression of IL-33 during allergic lung inflammation. Eur J Immunol. 2013;43:488–98. doi: 10.1002/eji.201242863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cayrol C, Girard JP. IL-33: an alarmin cytokine with crucial roles in innate immunity, inflammation and allergy. Curr Opin Immunol. 2014;31:31–7. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2014.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Roussel L, Erard M, Cayrol C, Girard JP. Molecular mimicry between IL-33 and KSHV for attachment to chromatin through the H2A-H2B acidic pocket. EMBO Rep. 2008;9:1006–12. doi: 10.1038/embor.2008.145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mirchandani AS, Salmond RJ, Liew FY. Interleukin-33 and the function of innate lymphoid cells. Trends Immunol. 2012;33:389–96. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2012.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Oboki K, Nakae S, Matsumoto K, Saito H. IL-33 and airway inflammation. Allergy, Asthma Immunol Res. 2011;3:81–8. doi: 10.4168/aair.2011.3.2.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pei C, Barbour M, Fairlie-Clarke KJ, Allan D, Mu R, Jiang HR. Emerging role of interleukin-33 in autoimmune diseases. Immunology. 2014;141:9–17. doi: 10.1111/imm.12174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tominaga S. A putative protein of a growth specific cDNA from BALB/c-3T3 cells is highly similar to the extracellular portion of mouse interleukin 1 receptor. FEBS Lett. 1989;258:301–4. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(89)81679-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Oshikawa K, Yanagisawa K, Tominaga S, Sugiyama Y. Expression and function of the ST2 gene in a murine model of allergic airway inflammation. Clin Exp Allergy. 2002;32:1520–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2745.2002.01494.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Oshikawa K, Kuroiwa K, Tago K, Iwahana H, Yanagisawa K, Ohno S, et al. Elevated soluble ST2 protein levels in sera of patients with asthma with an acute exacerbation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164:277–81. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.2.2008120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kuroiwa K, Arai T, Okazaki H, Minota S, Tominaga S. Identification of human ST2 protein in the sera of patients with auto- immune diseases. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;284:1104–8. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tajima S, Oshikawa K, Tominaga S, Sugiyama Y. The increase in serum soluble ST2 protein upon acute exacerbation of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Chest. 2003;124:1206–14. doi: 10.1378/chest.124.4.1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Weinberg EO, Shimpo M, Hurwitz S, Tominaga S, Rouleau JL, Lee RT. Identification of serum soluble ST2 receptor as a novel heart failure biomarker. Circulation. 2003;107:721–6. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000047274.66749.FE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mathews LR, Lott JM, Isse K, Lesniak A, Landsittel D, Demetris AJ, et al. Elevated ST2 distinguishes incidences of pediatric heart and small bowel transplant rejection. Am J Transplant. 2016;16:938–50. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Seidelin JB, Rogler G, Nielsen OH. A role for interleukin-33 in TH2-polarized intestinal inflammation? Mucosal Immunol. 2011;4:496–502. doi: 10.1038/mi.2011.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Aoki S, Hayakawa M, Ozaki H, Takezako N, Obata H, Ibaraki N, et al. ST2 gene expression is proliferation-dependent and its ligand, IL-33, induces inflammatory reaction in endothelial cells. Mol Cell Biochem. 2010;335:75–81. doi: 10.1007/s11010-009-0244-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Choi YS, Choi HJ, Min JK, Pyun BJ, Maeng YS, Park H, et al. Interleukin-33 induces angiogenesis and vascular permeability through ST2/TRAF6-mediated endothelial nitric oxide production. Blood. 2009;114:3117–26. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-02-203372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yagami A, Orihara K, Morita H, Futamura K, Hashimoto N, Matsumoto K, et al. IL-33 mediates inflammatory responses in human lung tissue cells. J Immunol. 2010;185:5743–50. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Funakoshi-Tago M, Tago K, Hayakawa M, Tominaga S, Ohshio T, Sonoda Y, et al. TRAF6 is a critical signal transducer in IL-33 signaling pathway. Cell Signal. 2008;20:1679–86. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2008.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kurowska-Stolarska M, Kewin P, Murphy G, Russo RC, Stolarski B, Garcia CC, et al. IL-33 induces antigen-specific IL-5+ T cells and promotes allergic-induced airway inflammation independent of IL-4. J Immunol. 2008;181:4780–90. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.7.4780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Villarreal DO, Wise MC, Walters JN, Reuschel E, Choi MJ, Obeng-Adjei N, et al. Alarmin IL-33 acts as an immunoadjuvant to enhance antigen-specific tumor immunity. Cancer Res. 2014;74:1789–800. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-2729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Villarreal DO, Weiner DB. Interleukin 33: a switch-hitting cytokine. Curr Opin Immunol. 2014;28:102–6. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2014.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Matta BM, Turnquist HR. Expansion of regulatory T cells in vitro and in vivo by IL-33. Methods Mol Biol. 2016;1371:29–41. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-3139-2_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Liew FY, Girard JP, Turnquist HR. Interleukin-33 in health and disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2016;16:676–89. doi: 10.1038/nri.2016.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Turnquist HR, Zhao Z, Rosborough BR, Liu Q, Castellaneta A, Isse K, et al. IL-33 expands suppressive CD11b + Gr-1(int) and regulatory T cells, including ST2L+Foxp3+ cells, and mediates regulatory T cell-dependent promotion of cardiac allograft survival. J Immunol. 2011;187:4598–610. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Matta BM, Reichenbach DK, Zhang X, Mathews L, Koehn BH, Dwyer GK, et al. Peri-alloHCT IL-33 administration expands recipient T-regulatory cells that protect mice against acute GVHD. Blood. 2016;128:427–39. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-12-684142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kuswanto W, Burzyn D, Panduro M, Wang KK, Jang YC, Wagers AJ, et al. Poor repair of skeletal muscle in aging mice reflects a defect in local, interleukin-33-dependent accumulation of regulatory T cells. Immunity. 2016;44:355–67. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Noel G, Arshad MI, Filliol A, Genet V, Rauch M, Lucas-Clerc C, et al. Ablation of interaction between IL-33 and ST2+ regulatory T cells increases immune cell-mediated hepatitis and activated NK cell liver infiltration. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2016;311:G313–23. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00097.2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Duan L, Chen J, Zhang H, Yang H, Zhu P, Xiong A, et al. Interleukin-33 ameliorates experimental colitis through promoting Th2/Foxp3+regulatory T-cell responses in mice. Mol Med. 2012;18:753–61. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2011.00428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Schiering C, Krausgruber T, Chomka A, Fröhlich A, Adelmann K, Wohlfert EA, et al. The alarmin IL-33 promotes regulatory T-cell function in the intestine. Nature. 2014;513:564–8. doi: 10.1038/nature13577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Moulin D, Donzé O, Talabot-Ayer D, Mézin F, Palmer G, Gabay C. Interleukin (IL)-33 induces the release of pro-inflammatory mediators by mast cells. Cytokine. 2007;40:216–25. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2007.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ali S, Huber M, Kollewe C, Bischoff SC, Falk W, Martin MU. IL-1 receptor accessory protein is essential for IL-33-induced activation of T lymphocytes and mast cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:18660–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705939104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Iikura M, Suto H, Kajiwara N, Oboki K, Ohno T, Okayama Y, et al. IL-33 can promote survival adhesion and cytokine production in human mast cells. Lab Invest. 2007;87:971–8. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Allakhverdi Z, Smith DE, Comeau MR, Delespesse G. Cutting edge: the ST2 ligand IL-33 potently activates and drives maturation of human mast cells. J Immunol. 2007;179:2051–4. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.4.2051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Andrade MV, Iwaki S, Ropert C, Gazzinelli RT, Cunha-Melo JR, Beaven MA. Amplification of cytokine production through synergistic activation of NFAT and AP-1 following stimulation ofmast cells with antigen and IL-33. Eur J Immunol. 2011;41:760–72. doi: 10.1002/eji.201040718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Silver MR, Margulis A, Wood N, Goldman SJ, Kasaian M, Chaudhary D. IL-33 synergizes with IgE-dependent and IgE-independent agents to promote mast cell and basophil activation. Inflamm Res. 2010;59:207–18. doi: 10.1007/s00011-009-0088-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Morita H, Arae K, Unno H, Miyauchi K, Toyama S, Nambu A, et al. An interleukin-33-mast cell-interleukin-2 axis suppresses papain-induced allergic inflammation by promoting regulatory T cell numbers. Immunity. 2015;43:175–86. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.06.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Smithgall MD, Comeau MR, Yoon BR, Kaufman D, Armitage R, Smith DE. IL-33 amplifies both Th1- and Th2-type responses through its activity on human basophils, allergen-reactive Th2 cells, iNKT and NK cells. Int Immunol. 2008;20:1019–30. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxn060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Pecaric-Petkovic T, Didichenko SA, Kaempfer S, Spiegl N, Dahinden CA. Human basophils and eosinophils are the direct target leukocytes of the novel IL-1 family member IL-33. Blood. 2009;113:1526–34. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-05-157818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Suzukawa M, Iikura M, Koketsu R, Nagase H, Tamura C, Komiya A, et al. An IL-1 cytokine member, IL-33, induces human basophil activation via its ST2 receptor. J Immunol. 2008;181:5981–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.9.5981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Suzukawa M, Koketsu R, Iikura M, Nakae S, Matsumoto K, Nagase H. Interleukin-33 enhances adhesion, CD11b expression and survival in human eosinophils. Lab Invest. 2008;88:1245–53. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2008.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Cherry WB, Yoon J, Bartemes KR, Iijima K, Kita H. A novel IL-1 family cytokine, IL-33, potently activates human eosinophils. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;121:1484–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ohno T, Morita H, Arae K, Matsumoto K, Nakae S. Interleukin-33 in allergy. Allergy. 2012;67:1203–14. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 88.Kurowska-Stolarska M, Stolarski B, Kewin P, Murphy G, Corrigan CJ, Ying S, et al. IL-33 amplifies the polarization of alternatively activated macrophages that contribute to airway inflammation. J Immunol. 2009;183:6469–77. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Besnard AG, Togbe D, Guillou N, Erard F, Quesniaux V, Ryffel B. IL-33-activated dendritic cells are critical for allergic airway inflammation. Eur J Immunol. 2011;41:1675–86. doi: 10.1002/eji.201041033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Rank MA, Kobayashi T, Kozaki H, Bartemes KR, Squillace DL, Kita H. IL-33-activated dendritic cells induce an atypical TH2-type response. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;123:1047–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.02.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Matta BM, Lott JM, Mathews LR, Liu Q, Rosborough BR, Blazar BR, et al. IL-33 is an unconventional alarmin that stimulates IL-2 secretion by dendritic cells to selectively expand IL-33R/ST2+ regulatory T cells. J Immunol. 2014;193:4010–20. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1400481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Martinez-Gonzalez I, Steer CA, Takei F. Lung ILC2s link innate and adaptive responses in allergic inflammation. Trends Immunol. 2015;36:189–95. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2015.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Halim TY, Steer CA, Mathä L, Gold MJ, Martinez-Gonzalez I, McNagny KM, et al. Group 2 innate lymphoid cells are critical for the initiation of adaptive T helper 2 cell-mediated allergic lung inflammation. Immunity. 2014;40:425–35. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Barlow JL, McKenzie AN. Nuocytes: expanding the innate cell repertoire in type-2 immunity. J Leukoc Biol. 2011;90:867–74. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0311160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Neill DR, Wong SH, Bellosi A, Flynn RJ, Daly M, Langford TK. Nuocytes represent a new innate effector leukocyte that mediates type-2 immunity. Nature. 2010;464:1367–70. doi: 10.1038/nature08900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Barlow JL, Bellosi A, Hardman CS, Drynan LF, Wong SH, Cruickshank JP, et al. Innate IL-13-producing nuocytes arise during allergic lung inflammation and contribute to airways hyperreactivity. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129:191-8–e1-4. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.09.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Chang YJ, Kim HY, Albacker LA, Baumgarth N, McKenzie AN, Smith DE, et al. Innate lymphoid cells mediate influenza-induced airway hyper-reactivity independently of adaptive immunity. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:631–8. doi: 10.1038/ni.2045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Bartemes KR, Iijima K, Kobayashi T, Kephart GM, McKenzie AN, Kita H. IL-33-responsive lineage− CD25+ CD44(hi) lymphoid cells mediate innate type 2 immunity and allergic inflammation in the lungs. J Immunol. 2012;188:1503–13. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1102832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Rak GD, Osborne LC, Siracusa MC, Kim BS, Wang K, Bayat A, et al. IL-33-dependent group 2 innate lymphoid cells promote cutaneous wound healing. J Invest Dermatol. 2016;136:487–96. doi: 10.1038/JID.2015.406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Besnard AG, Guabiraba R, Niedbala W, Palomo J, Reverchon F, Shaw TN, et al. IL-33-mediated protection against experimental cerebral malaria is linked to induction of type 2 innate lymphoid cells, M2 macrophages and regulatory T cells. PLoS Pathog. 2015;11:e1004607. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Hung LY, Lewkowich IP, Dawson LA, Downey J, Yang Y, Smith DE, et al. IL-33 drives biphasic IL-13 production for noncanonical type 2 immunity against hookworms. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:282–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1206587110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Yang Q, Li G, Zhu Y, Liu L, Chen E, Turnquist H. IL-33 synergizes with TCR and IL-12 signaling to promote the effector function of CD8+ T cells. Eur J Immunol. 2011;41:3351–60. doi: 10.1002/eji.201141629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Bourgeois E, Van LP, Samson M, Diem S, Barra A, Roga S, et al. The pro-Th2 cytokine IL-33 directly interacts with invariant NKT and NK cells to induce IFN-gamma production. Eur J Immunol. 2009;39:1046–55. doi: 10.1002/eji.200838575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Çekmez F, Fidanci MK, Ayar G, Saldir M, Karaoglu A, Gündüz RC, et al. Diagnostic value of upar, IL-33, and ST2 levels in childhood sepsis. Clin Lab. 2016;62:751–5. doi: 10.7754/clin.lab.2014.141013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Brunner M, Krenn C, Roth G, Moser B, Dworschak M, Jensen-Jarolim E, et al. Increased levels of soluble ST2 protein and IgG1 production in patients with sepsis and trauma. Intensive Care Med. 2004;30:1468–73. doi: 10.1007/s00134-004-2184-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Hoogerwerf JJ, Tanck MW, van Zoelen MA, Wittebole X, Laterre PF, van der Poll T. Soluble ST2 plasma concentrations predict mortality in severe sepsis. Intensive Care Med. 2010;36:630–7. doi: 10.1007/s00134-010-1773-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Hur M, Kim H, Kim HJ, Yang HS, Magrini L, Marino R, et al. Soluble ST2 has a prognostic role in patients with suspected sepsis. Ann Lab Med. 2015;35:570–7. doi: 10.3343/alm.2015.35.6.570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Parenica J, Malaska J, Jarkovsky J, Lipkova J, Dastych M, Helanova K, et al. Soluble ST2 levels in patients with cardiogenic and septic shock are not predictors of mortality. Exp Clin Cardiol. 2012;17:205–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Brint EK, Xu D, Liu H, Dunne A, McKenzie AN, O’Neill LA, et al. ST2 is an inhibitor of interleukin 1 receptor and Toll-like receptor 4 signaling and maintains endotoxin tolerance. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:373–9. doi: 10.1038/ni1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Liu J, Buckley JM, Redmond HP, Wang JH. ST2 negatively regulates TLR2 signaling, but is not required for bacterial lipoprotein- induced tolerance. J Immunol. 2010;184:5802–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0904127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Espinassous Q, Garcia-de-Paco E, Garcia-Verdugo I, Synguelakis M, von Aulock S, Sallenave JM, et al. IL-33 enhances lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammatory cytokine production from mouse macrophages by regulating lipopolysaccharide receptor complex. J Immunol. 2009;183:1446–55. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Oboki K, Ohno T, Kajiwara N, Saito H, Nakae S. IL-33 and IL-33 receptors in host defense and diseases. Allergol Int. 2010;59:143–60. doi: 10.2332/allergolint.10-RAI-0186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Xiang Y, Eyers F, Herbert C, Tay HL, Foster PS, Yang M. MicroRNA-487b is a negative regulator of macrophage activation by targeting IL-33 production. J Immunol. 2016;196:3421–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1502081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Ohno T, Oboki K, Morita H, Kajiwara N, Arae K, Tanaka S, et al. Paracrine IL-33 stimulation enhances lipopolysaccharide-mediated macrophage activation. PLoS One. 2011;6:e18404. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Sweet MJ, Leung BP, Kang D, Sogaard M, Schulz K, Trajkovic V, et al. A novel pathway regulating lipopolysaccharide-induced shock by ST2/T1 via inhibition of Toll-like receptor 4 expression. J Immunol. 2001;166:6633–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.11.6633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Takezako N, Hayakawa M, Hayakawa H, Aoki S, Yanagisawa K, Endo H, et al. ST2 suppresses IL-6 production via the inhibition of IkappaB degradation induced by the LPS signal in THP-1 cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;341:425–32. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.12.206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Nagata A, Takezako N, Tamemoto H, Ohto-Ozaki H, Ohta S, Tominaga S, et al. Soluble ST2 protein inhibits LPS stimulation on monocyte-derived dendritic cells. Cell Mol Immunol. 2012;9:399–409. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2012.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Nabe T, Wakamori H, Yano C, Nishiguchi A, Yuasa R, Kido H, et al. Production of interleukin (IL)-33 in the lungs during multiple antigen challenge-induced airway inflammation in mice, and its modulation by a glucocorticoid. Eur J Pharmacol. 2015;757:34–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2015.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Stier MT, Goleniewska K, Peebles RS. Respiratory syncytial virus induces IL-25 and IL-33 production in the lungs. J Allergy Clin Immun. 2014;133:AB53. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.12.214. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Martínez-González I, Roca O, Masclans JR, Moreno R, Salcedo MT, Baekelandt V, et al. Human mesenchymal stem cells overexpressing the IL-33 antagonist soluble IL-1 receptor-like-1 attenuate endotoxin-induced acute lung injury. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2013;49:552–62. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2012-0406OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Yin H, Li XY, Yuan BH, Zhang BB, Hu SL, Gu HB, et al. Adenovirus-mediated overexpression of soluble ST2 provides a protective effect on lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury in mice. Clin Exp Immunol. 2011;164:248–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2011.04326.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Hoogerwerf JJ, Leendertse M, Wieland CW, de Vos AF, de Boer JD, Florquin S, et al. Loss of suppression of tumorigenicity 2 (ST2) gene reverses sepsis-induced inhibition of lung host defense in mice. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:932–40. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201006-0934OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Buckley JM, Liu JH, Li CH, Blankson S, Wu QD, Jiang Y, et al. Increased susceptibility of ST2-deficient mice to polymicrobial sepsis is associated with an impaired bactericidal function. J Immunol. 2011;187:4293–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Blok DC, de Vos AF, Florquin S, van der Poll T. Role of interleukin 1 receptor like 1 (ST2) in gram-negative and gram-positive sepsis in mice. Shock. 2013;40:290–6. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e3182a35f02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Alves-Filho JC, Sonego F, Souto FO, Freitas A, Verri WA, Jr, Auxili-Adora-Martins M, et al. Interleukin-33 attenuates sepsis by enhancing neutrophil influx to the site of infection. Nat Med. 2010;16:708–12. doi: 10.1038/nm.2156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Li S, Zhu FX, Zhao XJ, An YZ. The immunoprotective activity of interleukin-33 in mouse model of cecal ligation and puncture-induced sepsis. Immunol Lett. 2016;169:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2015.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Lan F, Yuan B, Liu T, Luo X, Huang P, Liu Y, et al. Interleukin-33 facilitates neutrophil recruitment and bacterial clearance in S. aureus-caused peritonitis. Mol Immunol. 2016;72:74–80. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2016.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.