Abstract

We examined the clinical response of fludarabine-refractory CLL patients treated with high-dose methylprednisolone (HDMP) and rituximab. Fourteen patients were treated with three cycles of rituximab (375mg/m2 weekly for 4 weeks) in combination with HDMP (1gm/m2 daily for 5 days). All patients were refractory to fludarabine and 86% had high-risk disease by the modified Rai classification. In all, 79% of the patients had CLL cells that expressed ZAP-70 and three patients had poor prognostic cytogenetics. The overall response rate was 93% and the complete remission rate was 36%. The median time-to-progression was 15 months and the median time-to-next treatment was 22 months. Median survival has not been reached after a median follow up of 40 months. Four patients have died of progressive disease. Patients tolerated the treatment well and serious adverse events were rare. This allowed patients to receive all planned treatments on schedule with no dose modifications. All but one patient responded to treatment and the overall survival and time-to-progression were superior to those of other published salvage regimens.

Keywords: chronic lymphocytic leukemia, rituximab, methylprednisolone

Introduction

Despite recent progress using chemoimmunotherapy combinations for the treatment of patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), an effective cure for this disease has not been identified.

Combination regimens such as those using fludarabine and rituximab (FR), FR plus cyclophosphamide (FCR) or fludarabine, cyclophosphamide and mitoxantrone (FCM) can achieve overall and complete response rates that are higher than those observed with single-agent therapy. However, the risk of adverse events can be high, particularly in patients with compromised marrow function. Moreover, many patients cannot tolerate treatment, requiring dosage reduction or delay in therapy primarily because of myelosuppression.1–3

Alemtuzumab (Campath-1H), a monoclonal antibody that binds CD52, is the only drug approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of patients with CLL refractory or intolerant to fludarabine. The overall response rate to alemtuzumab is approximately 33%.4,5 Nevertheless, the majority of these responses are partial and complete responses are infrequent, particularly in patients with bulky lymphadenopathy, splenomegaly, or extensive tumor burden. Adverse events caused by infections and lack of activity in bulky disease often precludes continued use of alemtuzumab.6

Rituximab is a genetically engineered chimeric murine/human monoclonal antibody directed against the CD20 antigen and it is approved by the FDA for treatment of patients with low-grade or follicular CD20-positive, B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma; diffuse large B-cell CD20-positive non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and rheumatoid arthritis in combination with methotrexate. Rituximab has activity in CLL, particularly at higher doses than those commonly used for treatment of follicular lymphoma.7,8 In addition, high dose methylprednisolone (HDMP) also has anti-leukemia activity.9 However, use of either agent alone typically yields partial remission rates of less than 40%, and complete remissions are rare.

We observed that rituximab may have synergistic activity with glucocorticoids inducing apoptosis of leukemia cells cultured with ‘nurse-like cells’, which can protect CLL cells from spontaneous or drug-induced apoptosis in vitro and presumably in vivo.10,11 Because of this we evaluated the activity of HDMP-Rituximab in patients with fludarabine-refractory disease.

Patients and methods

Patient group

Fourteen patients with CLL were enrolled and treated on this protocol. All patients provided informed consent according to our institutional guidelines. Patients were required to have an indication for treatment based on the National Cancer Institute Working Group Guidelines (NCIWG-96).12 Also, all patients were required to be refractory to fludarabine defined as, patients who had received at least one earlier treatment containing fludarabine and failed to achieve either a partial or a complete remission (PR or CR) after at least two cycles, had disease progression during treatment or showed disease progression within 6 months of treatment or presented intolerance to fludarabine-based treatment.12 Patients were required to have an ECOG performance status of ≤2 and normal renal and hepatic function. We excluded patients who had prior intolerance to glucocorticoids or prior history of gastrointestinal bleeding. Pretreatment evaluation consisted of medical history and physical examination; laboratory studies including complete blood count, serum electrolytes, renal and hepatic function tests, and serum β 2-microglobulin (β2M). In addition, cells were evaluated for Inmunoglobulin heavy chain mutational status, ZAP-70 and CD38 expression by flow cytometry, using methods that have been described earlier.13,14 Patients underwent marrow biopsy and aspiration with immunophenotyping and either metaphase karyotype analysis and/or fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) analysis using commercial hybridizing probes for del17(p13.1), del13(q14.3), del11(q22.3), and trisomy 12—Vysis Inc. (Des Plains, IL, USA).15,16

Treatment and monitoring

Patients received the planned treatment as an outpatient infusion. HDMP was administered at 1 gm/m2 intravenously over 90 min daily for five consecutive days. Rituximab was provided by Genentech Inc. (San Francisco, CA, USA) and was administered at a dose of 375mg/m2 on days 1, 3, 5, 8, 17 and 22 during the first course of treatment and on days 1, 7, 14 and 21 during courses 2 and 3. To decrease the incidence of initial infusion reaction, patients received the first dose of rituximab divided in 2 days (for example, 100 mg on day 1 and the remainder of the 375mg/m2 dose on day 2). Patients received a new course of treatment every 28 days for a total of three courses.

The patients were pre-medicated before HDMP with intravenous cimetidine at 300 mg, oral acetaminophen 650 mg, and oral diphenhydramine 50 mg before receiving rituximab. In addition, all patients received prophylaxis for Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia with trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole or equivalent, prophylaxis for herpes virus with acyclovir 400 mg b.i.d. daily, and antifungal prophylaxis with fluconazole 100 mg daily. These prophylactic medications were used throughout the treatment period until 2 months after the completion of therapy. A physician evaluated the patients promptly if they had fever or progressive symptoms.

Cycles of treatment were administered every 4 weeks as permitted. Laboratory evaluations performed on the patients during therapy included CBC with differential, platelets, complete chemistry panel with uric acid and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), performed on days 1–5 of each cycle and on days of rituximab infusions (8, 15 and 22). Patients with fasting blood glucose of ≥200 mg/dl on the days of treatment with HDMP received treatment with regular insulin following a sliding scale. We treated patients with persistent hyperglycemia above 400 mg/dl with oral hypoglycemic agents and/or insulin as required. There were no dose adjustments for rituximab or HDMP. Patients underwent a full physical examination with particular emphasis on the assessment of the sizes of lymph nodes (bidimentional), spleen and liver at the beginning of each course of treatment, at two months after completion of the last course of treatment. All patients underwent a marrow biopsy 2 months after completing treatment to assess for residual disease.

Non-hematologic toxicity was graded accordingly with the National Cancer Institutes Common Toxicity Criteria (http://ctep.cancer.gov/reporting/ctc.html). Hematological toxicity was graded according to the NCIWG-96.12

Response criteria

Patients were evaluated for response using the NCIWG-96 criteria.12

Statistical considerations

The primary goal of this study was to evaluate the safety and efficacy of the combination treatment of rituximab and HDMP in patients with CLL who were refractory to fludarabine and had relapse with indications of treatment by the NCIWG-96 guidelines.12 A total of 14 evaluable patients were accrued using a two-stage Simon design.17 The following statistical model was used for the sample calculation: An average overall response (CR + PR) rate of 45% for either agent alone (P0 = 0.5),7–9,15 a desired response rate with combined treatment of 80% (P1 = 0.8), an α = 0.05 and β = 0.2 (power = 80%).

Clinical and laboratory end points were obtained to evaluate safety and efficacy following the NCIWG-96 guidelines for response assessment of patients with CLL.12 Demographics and baseline characteristics, time-to-response, response duration, time-to-progression, time-to-next treatment, and overall survival, were recorded and evaluated.

Descriptive statistics (mean±s.d.) were used to analyze change in lymphocyte count, lymph node size (using the sum lymph-node area from the largest lymph nodes), spleen size, hemoglobin, and platelet counts.

The distribution of time-to-progression and survival were estimated by the Kaplan–Meier method18 The Kaplan–Meier curves for the categorical variables were plotted for disease-free and overall survival. The P-values for testing the differences between subgroups were calculated by the log-rank test.19 Time intervals were measured from the first day of treatment until progression, relapse, time-to-next treatment, or death. Deaths from all causes were included.

Patients were followed until progression, death, or need to treatment. The analysis was performed on an intention-to-treat basis.

Results

Patient demographics and characteristics

Among the enrolled patients there were three females and 11 males, 85% of patients were high risk and the mean age was 59 years. All patients met inclusion criteria for having CLL that was refractory to fludarabine-base therapy12 (Table 1). In addition, 21% had previously received rituximab therapy, either alone or in combination with other antineoplasics. The median number of earlier treatments was two (one to four). Eight patients (57%) had CLL cells that expressed unmutated Ig variable region of the heavy chain (IgVH), 11 patients (78%) had CLL cells that expressed ZAP-70 by flow cytometry, and nine patients (64%) had leukemia cells with high-level of CD38 expression (> 30%). We performed metaphase karyotype and FISH analysis15,16 on the marrow aspirate of most patients and found chromosomal aberrations associated with high-risk disease in three patients, including 11q deletion in two patients and one with 17p deletion.

Table 1.

Patient demographics and characteristics

| Patientsa | VH homology | % ZAP-70 | % CD38 | Age | Prior Tx. | Sex | Cytogenetics | FISH | ECOG-PS | RAI stage | B2 MG | Response to Tx |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CLL-1 | NA | 23.2 | 95.6 | 72 | GT, F, Chl, FC | M | 46,XY | del11q | 1 | IV | 5,2 | PR |

| CLL-2 | 97.2 | 62.4 | 65.5 | 48 | F | F | 46,XX | Normal | 1 | II | 2,7 | CR |

| CLL-3 | 93.3 | 6.4 | 0.6 | 55 | F | F | 46,XX | del13q14.3 | 0 | IV | 2,3 | CR |

| CLL-4 | 100 | 21.4 | 99 | 63 | C, F | M | NA | NA | 0 | IV | 2,2 | CR |

| CLL-5 | 100 | 39 | 28.9 | 63 | F | M | 46,XY | Normal | 0 | IV | 4,4 | PR |

| CLL-6 | 99.6 | 62.2 | 6 | 47 | F, FR | M | 46,XY | del2q, abnormal Chr 7(q11.2) | 0 | III | 1,9 | CR |

| CLL-7 | NA | 6.8 | 44.4 | 70 | Chl+P, CVD, F and FR | M | NA | del11q, del13q14.3 | 0 | IV | 4,4 | PR |

| CLL-8 | 96.4 | 59.3 | 71.2 | 57 | F, FR | M | 46,XY | Normal | 0 | IV | 4 | PR |

| CLL-9 | 100 | 63.3 | 94.4 | 39 | F | M | 46,XY | Normal | 0 | IV | 3,5 | NPR |

| CLL-10 | 99.6 | 29.1 | 43.6 | 61 | GT, F | F | 46,XX | Normal | 0 | IV | 5,7 | PR |

| CLL-11 | 100 | 67.1 | 30.5 | 65 | F, CHOP | M | NA | NA | 1 | IV | 5,7 | PD |

| CLL-12 | NA | NA | 8.4 | 76 | F | M | NA | NA | 0 | IV | 5,6 | CR |

| CLL-13 | 99.6 | 62.8 | 46.3 | 63 | F | M | 46,XY | Trisomy12,del17p | 0 | III | 7 | NPR |

| CLL-14 | 100 | 85.7 | 10.2 | 50 | F | M | NA | NA | 0 | II | 3,4 | PR |

Abbreviations: Chl, chlorambucil; CHOP, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vivcristine and prednisolone; CR, complete remission; CVD, cyclophosphamide, vincristine and dexametasone; F, fludarabine; GT, gene therapy (CD154); NA, not available; NPR, nodular partial remission; PD, progressive disease; PR, partial remission; P, prednisolone; R, rituximab.

All patients presented criteria that indicated refractoriness to fludarabine-based therapy.12

Response to treatment

All patients, except one, responded to treatment (overall response rate 93%). The non-responding patient developed progressive disease 6 months after completion of this treatment and had a clinical suspicion of Richter’s transformation that was not confirmed with biopsy. Five patients achieved a CR (36%), six patients a PR (43%), and two patients had a nodular partial remission (nPR) (14%).

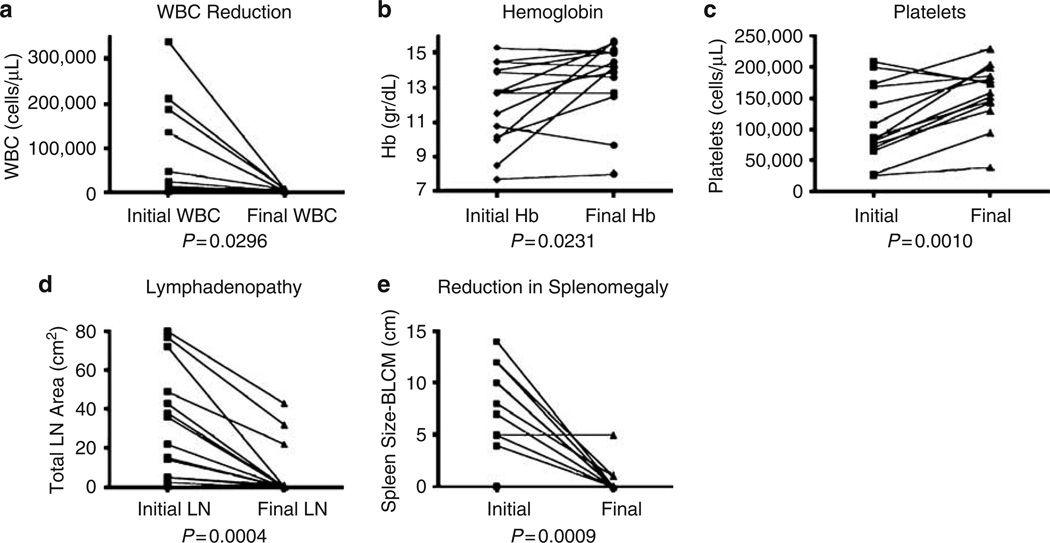

We observed a statistically significant decrease in white blood cell counts, increases in hemoglobin and platelet counts, and a dramatic reduction in lymphadenopathy and splenomegaly (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Comparison of clinical and laboratory parameters before treatment and at the end of the follow up period. (a) White blood cells count (WBC); (b) Hemoglobin values; (c) Platelet counts. (d) Lymph node area; sum of the large lymph nodes from each anatomic area; (e) Spleen size measured in centimeters below the left costal margin (BLCM). Statistical analysis was performed using paired t-test, two tailed P-values.

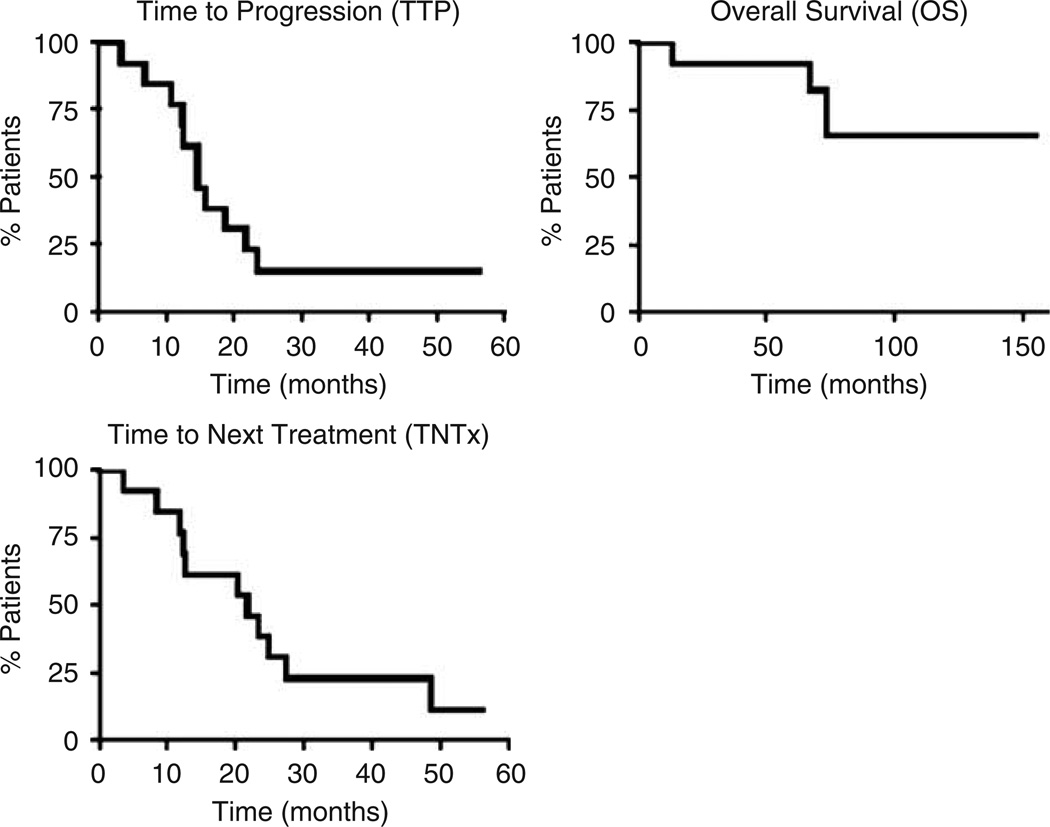

Disease progression and survival

The current median follow-up time for all patients is 40 months (range, 4–65 months), and for surviving patients is 45 months (range, 28–65 months). The Kaplan–Meier estimates of time-to-progression, time-to-next treatment and overall survival for all patients are shown in Figure 2. The median time-to-progression was 15 months (range, 3.2–23 months). Moreover, the median time-to-progression for patients achieving CR, PR, or PD was 23.4, 12.5, and 3.23 months, respectively. Two patients are still in complete remission with a median follow up of 48 months (CLL-2, CLL-4).

Figure 2.

Survival curves for each of the indicated outcomes. The analysis was created using the product limit method of Kaplan–Meier. Median time-to-progression (TTP)-15 months. Median time-to-survival (OS) has not been reached (median follow up 40 months after treatment and 78 months after diagnosis). Median time to next treatment (TNTx) 22 months.

The median duration of response to treatment measured by the time that took to next treatment was 22 months (49, 12.5, and 3.5 months for CR, PR and PD patients, respectively). The median survival for the 14 patients treated has not been reached after a median follow up of 40 months after treatment and 78 months after diagnosis (range, 13–155 months). The only patient who had progressive disease had a median survival of 13 months. Four patients died of disease progression.

Adverse events

All treated patients were able to complete the three courses of treatment without requiring delays or dosage reductions. The most common adverse event was fluid retention, which occurred in most cases, particularly in the lower extremities (six patients–43%) (Table 2). Five patients (36%) had marrow suppression with neutropenia and thrombocytopenia (four cases of Grade III–IV). These patients experienced improvements in their blood counts within 14 days after the initiation of therapy and could tolerate continued therapy without dose reduction or delays. Interestingly, worsening anemia was not observed. We observed gastro-esophageal reflux disease/dyspepsia, fatigue, hyperglycemia, or cough in three patients (21%). Other less common adverse events are listed in Table 2. Only one patient had infection-related complications (grade III pneumonia) following therapy. There were no cases of secondary leukemia or myelodysplastic syndrome.

Table 2.

Adverse events

| Adverse event | Grade I–II |

Grade III–IV |

Total no. of patients/(%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fluid retention | 6 | 6/43 | |

| BM suppression | 1 | 4 | 5/36 |

| Neutropenia | 2 | ||

| Thrombocytopenia | 2 | ||

| Anemia | 1 | ||

| GERD/dyspepsia | 3 | 3/21 | |

| Fatigue | 3 | 3/21 | |

| Hyperglycemia | 3 | 3/21 | |

| Cough | 3 | 3/21 | |

| Fever | 2 | 2/14 | |

| Mood changes | 2 | 2/14 | |

| Sore throat | 2 | 2/14 | |

| Nausea/vomiting | 2 | 2/14 | |

| Myalgias | 2 | 2/14 | |

| Flushing | 1 | 1/7 | |

| Insomnia | 1 | 1/7 | |

| Pneumonia | 1 | 1/7 | |

| Electrolyte disorder | 1 | 1/7 | |

| Leg pain | 1 | 1/7 | |

| Photophobia | 1 | 1/7 | |

| Anxiety | 1 | 1/7 | |

| Rigors/chills | 1 | 1/7 | |

| Hiccups | 1 | 1/7 | |

| Visual hallucinations | 1 | 1/7 |

Discussion

Despite recent advances in the treatment of CLL this disease remains incurable and younger patients almost invariably die of their disease.20 Patients who fail initial treatment and in particular fludarabine, have a poor prognosis with an estimated overall survival of 2 years or less.21,22 There is therefore a need for improved treatment strategies.

Historically CR and OR rates achieved with fludarabine as a salvage treatment were 5–10 and 40–60%, respectively. The median time-to-progression was 12–13 months, and median survival was 20–25 months.23,24 The combination of FC produced CR and OR rates of 10–15 and 60–70%, respectively, with a median response duration of 20–25 months in previously treated patients.22,25 More recently, the combination of FCR has been reported to induce OR rates of 73% and CR rates of 25% in this patient population.1 However, because of the presence of adverse events, approximately 50% of refractory patients treated with fludarabine combination regimens need to have dose reductions, skip courses of treatment, or have delays in administration of therapy because of myelosuppression.1,2,26

Alemtuzumab is effective in relapsed or refractory CLL and in patients with high-risk disease, but induces mostly partial responses (30%). Unfortunately, life-threatening complications and lack of activity in patients with bulky disease limit the use of this monoclonal antibody.6

The demographic characteristics of the patients treated with HDMP-Rituximab in this clinical study are similar to those of patients treated with salvage fludarabine-containing regimens. 1,2,22 Moreover, most of our patients had high-risk disease by the modified Rai classification and all were refractory to fludarabine. It is interesting to note that 78% (11/14) of patients had leukemia cells that expressed high-levels of ZAP-70, 57% (8/14) had CLL cells that express unmutated Ig variable region of the heavy chain (IgVH), 64% (9/14) had leukemia cells that expressed high-levels of CD38, and 14% (3/14) patients had cytogenetic abnormalities associated with poor prognosis (for example, deletions in 11q and 17p).

The CR (36%) and OR (93%) rates reported here with HDMP-Rituximab are higher than those reported for each agent alone in patients with relapsed/refractory disease,7–9,27 and higher than those reported for FC, FCR or Fludarabine, Cyclophosphamide and Mitoxantrone.1,2,22 In addition, the response rates observed for HDMP-Rituximab are higher than those noted for alemtuzumab in patients with fludarabine refractory disease, for which OR rates are approximately 30% and CRs are uncommon (for example, ≤2%).4,5

The median time from completion of therapy-to-progression for responding patients was 15 months. Two patients remain in CR more than 40 months after therapy (patients CLL-2 and CLL-4, Table 1). The median survival has not been achieved and 64% of the patients remain alive after a median follow up of 40 months. These results are highly encouraging as the highest overall survival reported for this group of patients has been 42 months following treatment with FCR.1 Interestingly, the three patients with poor prognostic cytogenetic/FISH abnormalities (patients CLL-1, CLL-7 with 11q deletion and 17p deletion in patient CLL-13. Table 1) responded to treatment.

The small sample size of this study makes it difficult to identify factors associated with a favorable response to therapy with HDMP-Rituximab. Nonetheless, the majority of patients in this study had high-risk factors, including criteria for fludarabine refractoriness, high expression of ZAP-70, high-expression of CD38, and/or cytogenetic-FISH abnormalities associated with adverse prognosis. The findings reported here, suggest that HDMP-Rituximab may be an effective regimen for this high-risk group of patients including those with lack of functional p53, as has been reported previously for HDMP alone.27

Myelosuppression, and in particular neutropenia, is one of the most frequent toxicities found in 60–90% of patients treated with salvage regimens for patients with relapsed and refractory CLL.1,2,22 Contrary to this, the HDMP-Rituximab regimen had a much lower incidence of grade 3 or 4 neutropenia (14%) or thrombocytopenia (14%). In addition, patients treated with this regimen did not experience myelosuppression that required dose adjustments, hospitalizations, or treatment delays.

All our patients received prophylactic antibiotics, which could decrease the incidence of life-threatening infectious adverse events in CLL patients undergoing treatment.28 The rate of infections in patients treated with HDMP-Rituximab was very low (1 out of 14 patients with one episode of pneumonia), compared with patients treated with fludarabine-based combinations or those with alemtuzumab, in which the incidence of infections remain ≥ 25%.1,2,4,5,20

Overall, our data suggest that the HDMP-Rituximab combination is an effective non-myelotoxic regimen for the treatment of patients with fludarabine-refractory disease. This regimen induces response rates that are comparable or even higher to those observed with fludarabine-based combination treatments. More importantly, HDMP-Rituximab showed a favorable safety profile, potentially allowing treatment of patients who are refractory to fludarabine and have marrow suppression, advanced age or additional high-risk features.

Acknowledgments

We thank Robier Aguillon and Oliver Loria for assistance with data collection. This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grant PO1-CA081534 (TJK) and from the National Institutes of Health Grant K08-CA106 605-01 (JEC).

References

- 1.Wierda W, O’Brien S, Wen S, Faderl S, Garcia-Manero G, Thomas D, et al. Chemoimmunotherapy with fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab for relapsed and refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:4070–4078. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.12.516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bosch F, Ferrer A, Lopez-Guillermo A, Gine E, Bellosillo B, Villamor N, et al. Fludarabine, cyclophosphamide and mitoxantrone in the treatment of resistant or relapsed chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Br J Haematol. 2002;119:976–984. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2002.03959.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cheson BD. Monoclonal antibody therapy of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2006;55:188–196. doi: 10.1007/s00262-005-0010-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Keating MJ, Flinn I, Jain V, Binet JL, Hillmen P, Byrd J, et al. Therapeutic role of alemtuzumab (Campath-1H) in patients who have failed fludarabine: results of a large International Study. Blood. 2002;99:3554–3561. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.10.3554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rai KR, Freter CE, Mercier RJ, Cooper MR, Mitchell BS, Stadtmauer EA, et al. Alemtuzumab in previously treated chronic lymphocytic leukemia patients who also had received fludarabine. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:3891–3897. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.06.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rai KR. Novel therapeutic strategies with alemtuzumab for chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Semin Oncol. 2006;33(2 Suppl 5):S15–S22. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2006.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Byrd JC, Murphy T, Howard RS, Lucas MS, Goodrich A, Park K, et al. Rituximab using a thrice weekly dosing schedule in B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia and small lymphocytic lymphoma demonstrates clinical activity and acceptable toxicity. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:2153–2164. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.8.2153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.O’Brien SM, Kantarjian H, Thomas DA, Giles FJ, Freireich EJ, Cortes J, et al. Rituximab dose-escalation trial in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:2165–2170. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.8.2165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thornton PD, Hamblin M, Treleaven JG, Matutes E, Lakhani AK, Catovsky D. High dose methyl prednisolone in refractory chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Leuk Lymphoma. 1999;34:167–170. doi: 10.3109/10428199909083393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tsukada N, Burger JA, Zvaifler NJ, Kipps TJ. Distinctive features of ‘nurselike’ cells that differentiate in the context of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2002;99:1030–1037. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.3.1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tsukada N, Kitada S, Reed JC, Kipps TJ. Combination rituximab and methylprednosolone mitigate the protective activity of nurse-like cells on leukemia cell viability in vitro. Blood. 2001;98:3767a. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cheson BD, Bennett JM, Grever M, Kay N, Keating MJ, O’Brien S, et al. National Cancer Institute-sponsored Working Group guidelines for chronic lymphocytic leukemia: revised guidelines for diagnosis and treatment. Blood. 1996;87:4990–4997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rassenti LZ, Huynh L, Toy TL, Chen L, Keating MJ, Gribben JG, et al. ZAP-70 compared with immunoglobulin heavy-chain gene mutation status as a predictor of disease progression in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:893–901. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Del Poeta G, Maurillo L, Venditti A, Buccisano F, Epiceno AM, Capelli G, et al. Clinical significance of CD38 expression in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2001;98:2633–2639. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.9.2633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dohner H, Stilgenbauer S, Benner A, Leupolt E, Krober A, Bullinger L, et al. Genomic aberrations and survival in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1910–1916. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200012283432602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Watson MS, editor. American College of Medical Genetics, Standards and Guidelines for Clinical Genetics Laboratories. Bethesda, MD: American College of Medical Genetics; 1999. pp. 22–36. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Simon R. Optimal two-stage designs for phase II clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1989;10:1–10. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(89)90015-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaplan EL, Meier P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc. 1958;53:457–481. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peto R, Pike MC, Armitage P, Breslow NE, Cox DR, Howard SV, et al. Design and analysis of randomized clinical trials requiring prolonged observation of each patient. II. analysis and examples. Br J Cancer. 1977;35:1–39. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1977.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kipps TJ. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia and related diseases. In: Beutler E, Lichtman MA, Coller BS, Kipps TJ, Seligsohn U, editors. Williams Hematology. 6th. New York: McGraw-Hill, Inc.; 2001. pp. 1163–1194. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Seymour JF, Robertson LE, O’Brien S, Lerner S, Keating MJ. Survival of young patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia failing fludarabine therapy: a basis for the use of myeloablative therapies. Leuk Lymphoma. 1995;18:493–496. doi: 10.3109/10428199509059650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.O’Brien SM, Kantarjian HM, Cortes J, Beran M, Koller CA, Giles FJ, et al. Results of the fludarabine and cyclophosphamide combination regimen in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:1414–1420. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.5.1414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.O’Brien S, Kantarjian H, Beran M, Smith T, Koller C, Estey E, et al. Results of fludarabine and prednisone therapy in 264 patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia with multivariate analysis-derived prognostic model for response to treatment. Blood. 1993;82:1695–1700. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Keating MJ, Kantarjian H, Talpaz M, Redman J, Koller C, Barlogie B, et al. Fludarabine: a new agent with major activity against chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 1989;74:19–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hallek M, Schmitt B, Wilhelm M, Busch R, Krober A, Fostitsch HP, et al. Fludarabine plus cyclophosphamide is an efficient treatment for advanced chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL): results of a phase II study of the German CLL Study Group. Br J Haematol. 2001;114:342–348. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2001.02959.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Byrd JC, Peterson BL, Morrison VA, Park K, Jacobson R, Hoke E, et al. Randomized phase 2 study of fludarabine with concurrent versus sequential treatment with rituximab in symptomatic, untreated patients with B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia: results from Cancer and Leukemia Group B 9712 (CALGB 9712) Blood. 2003;101:6–14. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-04-1258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thornton PD, Matutes E, Bosanquet AG, Lakhani AK, Grech H, Ropner JE, et al. High dose methylprednisolone can induce remissions in CLL patients with p53 abnormalities. Ann Hematol. 2003;82:759–765. doi: 10.1007/s00277-003-0710-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ravandi F, O’Brien S. Immune defects in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2006;55:197–209. doi: 10.1007/s00262-005-0015-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]