Abstract

This study examined whether the association of quality of life (QoL) with perceived neighbourhood problems is stronger in older adults with osteoarthritis (OA) than in those without OA. Of all 294 participants, 23.8% had OA. More perceived neighbourhood problems were associated with a stronger decrease in QoL over time in participants with OA (B=-0.018; p=0.02) than in those without OA (B=-0.004; p=0.39). Physical activity did not mediate this relationship. Older adults with OA may be less able to deal with more challenging environments.

Keywords: Neighbourhood problems, Older population, Osteoarthritis, Physical activity, Quality of life

Introduction

The importance of the neighbourhood environment for quality of life (QoL) has been recognized (Iwarsson et al., 2007; Lawton, 1986; Lawton and Nahemow, 1973; Rantakokko et al., 2010), but the association between specific features of the neighbourhood environment and QoL in older community-dwelling adults has not been studied extensively. In particular, research on the relationship between QoL and environmental barriers in older adults with disabilities is limited (Levasseur et al., 2015). Osteoarthritis (OA) is associated with significant pain and disability in older adults (Brooks, 2012; Jinks et al., 2002; Peat et al., 2001). Pain and disability caused by OA have a negative impact on physical activity, the use of neighbourhood resources, and QoL (De Groot et al., 2008; Van der Pas et al., 2016; Salaffi et al., 2005). Knowledge on the relationships between perceived neighbourhood problems, physical activity (PA) and QoL in older adults with and without OA is needed when planning environments that promote PA and well-being in healthy and functionally-impaired older persons.

It has been suggested that the less competent the individual, the greater the impact of environmental factors on that individual and that a fit between personal competencies and environmental demands leads to better well-being (Lawton, 1986; Lawton and Nahemow, 1973). Older adults with OA might be less competent compared to older persons without the condition and may experience more difficulties in overcoming perceived problems/barriers towards outdoor PA, which may result in poor QoL (Forsyth et al., 2009; Iwarsson, 2005; Shumway-Cook et al., 2003). Little is known about the association between specific neighbourhood problems and QoL in older community-dwelling persons (Rantakokko et al., 2010). A study by Puts et al. showed that older frail and non-frail community-dwelling persons report that perceived neighbourhood problems, such as noise and crime, lead to a lower QoL. Furthermore, it was found that the health of frail older persons limited the amount and scope of activities that they performed, resulting in a lower QoL (Puts et al., 2007). A study by Levasseur et al. showed that fewer barriers in the physical outdoor environment predicted good QoL in older adults with physical disabilities (Levasseur et al., 2008). Rantakokko et al. showed that perceived barriers in the outdoor environment, such as traffic and poor street conditions, reduce QoL in older community-dwelling people. It was found that older persons who had more chronic conditions and slower walking speed reported more barriers in their outdoor environment and had lower QoL than those who were healthier. Furthermore, Rantakokko et al. showed that fear of moving outdoors and unmet PA needs, considered to be the feeling that one’s level of PA is inadequate, mediate the association between perceived environmental barriers and QoL in older adults (Rantakokko et al., 2010). So far, the impact of environmental barriers on PA and QoL has never been studied in older adults with OA. To promote PA and improve QoL of individuals with OA, more knowledge is needed on the relationships between perceived neighbourhood problems, outdoor PA and QoL in this specific population.

This population-based study examines the association between QoL and perceived neighbourhood problems in older adults and assesses whether this relationship is stronger in those with OA. In addition, this study examines whether the association between perceived neighbourhood problems and QoL is mediated by actual outdoor PA. It is hypothesized that more perceived neighbourhood problems are cross-sectionally associated with poor QoL and are related to a decrease in QoL over time. It is expected that these relationships are stronger in older adults with OA than in those without the condition. Furthermore, it is hypothesized that PA plays a mediating role in the relationship between perceived neighbourhood problems and QoL. It is expected that more perceived neighbourhood problems reduce outdoor PA in older adults, which in turn reduces QoL.

Methods

Design and study sample

The study sample comprised men and women who participated in the United Kingdom (UK) component of the European Project on OSteoArthritis (EPOSA) and who originally participated in the Hertfordshire Cohort Study (HCS). The HCS and the EPOSA study have been described in detail previously (Syddall et al., 2005; Van der Pas et al., 2013). In summary, the HCS is a large, prospective, population-based study of the life course origins of adult disease among men and women born in Hertfordshire between 1931-1939 and still living in the county between 1998-2004. In 2010, a total of 592 surviving participants from the HCS were invited by letter to participate in the EPOSA study. The EPOSA study focuses on the personal and societal burden of OA and its determinants in older persons in six European countries. In total, 444 (75.0%) persons from HCS agreed to participate in the EPOSA baseline study. Of these participants, 410 (92.3%) persons agreed to participate in the EPOSA follow-up study in 2011. Reasons for non-response at follow-up were death (n=8), refusal (n=7), ineligible (n=9), and not contacted (n=4). For six persons, the reason for non-response at follow-up was unknown. The data on perceived neighbourhood problems was collected in 2008 using a postal survey. Based on previous research (Hertfordshire County Council, 2016), it is assumed that perceptions of neighbourhood problems remained stable between the postal survey and the EPOSA measurements. The participants who moved between the postal survey and the follow-up EPOSA measurement were excluded from the data analyses. Moreover, the participants who had no data available on perceived neighbourhood problems and/or the presence of OA were omitted. The analyses for this study are based on 294 older persons having data available at baseline on the presence of OA, perceived neighbourhood problems, QoL, and PA. The study was approved by the Hertfordshire Research Ethics Committee.

Quality of life

At baseline (2010) and follow-up (2011), QoL was measured using the EQ-5D. The EQ-5D is a generic instrument and it consists of 5 questions (Brooks et al., 2003). The 5 items are related to the following domains: 1) Mobility, 2) Self-care, 3) Usual activities, 4) Pain/discomfort, and 5) anxiety/depression. The answer categories differ between the 5 items, but can roughly be divided into: no problems (score 1), some problems (score 2) and extreme problems (score 3). The 5 domains can be converted into a single index score, which summarizes the health state of a participant. The time trade-off method was used to derive valuations for health states, which were subsequently modelled to predict the remaining index scores (Dolan, 1997). An index score of 0 represents death, and an index score of 1 represents perfect health.

Change in QoL over time was measured by using two methods. The first measure of change in QoL over time includes a continuous measure. This measure was calculated by subtracting the index score at follow-up from the index score at baseline (Grandy and Fox, 2012).

The second measure of change in QoL over time includes a dichotomous measure and was calculated by using the Edwards-Nunnally index. The Edwards-Nunnally index calculates individual significant change based on the reliability of the measurement instrument, the confidence interval (CI), and the population mean (Speer and Greenbaum, 1995). This index has been developed to determine pre/posttest recovery. It classifies change as improved or deteriorated using the confidence interval. If the posttest lies outside of this CI, it is considered to be significantly different from the pretest score. The pre/posttest change is adjusted for regression to the mean. In this study, a 95% CI was used for QoL. The scores were dichotomized into no decline (0) and decline (1).

Perceived neighbourhood problems

In the postal survey (2008), perceptions of neighbourhood problems were assessed by asking participants to consider a list of eight problems that people often have with the area where they live and indicate whether each one was not a problem (score 1), a small problem (score 2) or a big problem (score 3) for them. These and similar items have been widely used in UK government social surveys, such as the General Household Survey (Ali et al., 2009). The eight problems were: (1) vandalism, (2) litter and rubbish, (3) smells and fumes, (4) assaults and muggings, (5) burglaries, (6) disturbance by children or youngsters, (7) traffic, and (8) noise. An overall score was calculated by summing the scores for each item. The sumindex ranged from 8 to 24, with higher scores indicating more neighbourhood problems. Furthermore, the 8 individual neighbourhood problem items were dichotomized into no problem (0) and small/big problem (1).

Potential effect modifier

A potential effect modifier was clinical OA. In the EPOSA study (2010), the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) classification criteria (Altman, 1991) were used to diagnose OA in knee, hand and hip in older people. An algorithm was specified for non-specific OA (OA versus no-OA). An extensive description of the diagnosis of OA in knee, hand and hip is described elsewhere (Van der Pas et al., 2013).

Potential mediator

A potential mediator was outdoor PA. Physical activity was measured using the LASA Physical Activity Questionnaire (LAPAQ) (Stel et al., 2004). The LAPAQ covers frequency and duration of different activities during the previous two weeks. Activities covered in the LAPAQ include walking outside, cycling, gardening, light and heavy household work and a maximum of two sports. In order to calculate average daily outdoor PA in minutes, the frequency and duration of walking, cycling and gardening were multiplied and divided by 14 days. Sport activities were not included in this outdoor PA measure, because certain sports could be performed indoors as well as outdoors.

Potential confounders

We considered the following potential confounders: age, sex (0=men, 1=women), partner status (0=no partner, 1=partner), educational level (0<secondary education, 1≥secondary education), anxiety, depression, general cognitive functioning, and comorbidity.

Anxiety and depressive symptoms were examined by the Hospital Anxiety Depression Scales (HADS) (Zigmond and Snaith, 1983). The HADS is a self-report questionnaire comprising 14 four-point Likert scaled items, 7 for anxiety (HADS-A) and 7 for depression (HADS-D). Both scales have a range from 0 to 21. HADS-A and HADS-D were used as categorical variables with cut-off level of 8 or more for presence of anxiety and depression.

General cognitive functioning was measured by using the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) (Folstein et al., 1975; Tombaugh and McIntyre, 1992). The MMSE is a 23-item global cognitive function test, which includes questions on orientation in time and place, attention, language, memory and visual construction. The test was designed as a screening instrument for cognitive impairment and dementia. Scores range from 0 to 30, with a higher score indicating better performance. The MMSE-scores were dichotomized (0= no cognitive impairment (MMSE-score≥23), 1= cognitive impairment (MMSE-score<23)) (Tombaugh and McIntyre, 1992).

Comorbidity was measured through self-reported presence of the following chronic diseases or symptoms that lasted for at least three months or diseases for which the participant had been treated or monitored by a physician: chronic non-specific lung disease, cardiovascular diseases, peripheral artery diseases, stroke, diabetes, cancer, and osteoporosis. The number of chronic diseases other than OA was categorized and dummy-coded into 0 chronic diseases (0=no, 1=yes), 1 chronic disease (0=no, 1=yes), and 2 or more chronic diseases (0=no, 1=yes). The first category (0 chronic diseases) was used as reference category. This approach provides a balanced distribution across the categories and corresponds to earlier studies (Van Schoor et al., 2016; Visser et al., 2014).

Statistical analyses

Differences in means were tested using Independent Sample T-Tests for normally distributed variables. Differences in medians were tested using Mann Whitney U Tests for skewed continuous variables and differences in percentages were tested using Pearson Chi-square tests for categorical variables.

Multiple linear regression analyses were used to examine the cross-sectional association between QoL and perceived neighbourhood problems (sum index and individual items) at baseline and at follow-up, and the association between change in QoL over time (continuous measure) and perceived neighbourhood problems (sum index and individual items). Logistic regression analyses were used to examine the association of change in QoL over time (dichotomous measure) and perceived neighbourhood problems (sum index and individual items).

Osteoarthritis was assessed for potential effect modification by examining the interaction effect between OA and perceived neighbourhood problems on QoL in fully adjusted models. In case of a significant interaction effect (p<0.10) (Aiken and West, 1991), group-specific associations between QoL and perceived neighbourhood problems were presented. In case the interaction effect was not significant, a pooled analysis (also adjusted for OA) was performed. The association of (change in) QoL with perceived neighbourhood problems were examined in fully adjusted models. In all models, the p-value was set to 0.05. The above analyses were performed in IBM SPSS Statistics (version 20.0).

It was tested whether the cross-sectional association between QoL and perceived neighbourhood problems was mediated by PA, by applying the conditions described by Baron and Kenny (Baron and Kenny, 1986). According to them, a variable can be considered to be a mediator when: (a) the predictor is significantly associated with the hypothesized mediator, (b) the predictor is significantly associated with the dependent variable, (c) the mediator is significantly associated with the dependent variable, and (d) the impact of the predictor on the dependent variable is less after controlling for the mediator. These conditions were tested with linear regression analyses.

Results

The mean age of all 294 participants at baseline was 75.3 (SD=2.5) years at with an age-range of 71-80 years. Of all participants, 150 (51.0%) were female. Seventy (23.8%) persons fulfilled the ACR classification criteria for knee, hand, and/or hip OA. The baseline characteristics of the participants with and without OA are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Characteristics of the study sample at baseline stratified for osteoarthritis. a.

| All participants (n=294) |

Participants with OA (n=70) |

Participants without OA (n=224) |

p-value b | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | n | n | |||||

| Characteristics | |||||||

| Age in years (Mean (SD)) | 294 | 75.3 (2.5) | 70 | 74.5 (2.5) | 224 | 75.5 (2.4) | 0.01 |

| Sex (female) (n (%)) | 294 | 150 (51.0) | 70 | 36 (51.4) | 224 | 114 (50.9) | 0.94 |

| Partner status (yes) (n (%)) | 294 | 208 (70.7) | 70 | 60 (85.7) | 224 | 148 (66.1) | <0.01 |

| Education (≥ secondary education) (n (%)) | 294 | 237 (80.6) | 70 | 57 (81.4) | 224 | 180 (80.4) | 0.84 |

| Number of chronic diseases (n (%)) | 294 | 70 | 224 | 0.20 | |||

| 0 | 128 (43.6) | 36 (51.4) | 92 (41.1) | ||||

| 1 | 110 (37.4) | 25 (35.7) | 85 (37.9) | ||||

| ≥2 | 56 (19.0) | 9 (12.9) | 47 (21.0) | ||||

| Anxiety (HADS-A≥8) (n (%)) | 294 | 47 (16.0) | 70 | 19 (32.2) | 224 | 24 (11.2) | <0.001 |

| Depression (HADS-D≥8) (n (%)) | 290 | 33 (11.4) | 68 | 16 (23.5) | 222 | 17 (7.7) | <0.01 |

| General cognitive functioning (MMSE<23) (n (%)) | 294 | 13 (4.4) | 70 | 3 (4.3) | 224 | 10 (4.5) | 0.95 |

| Outdoor physical activity (Median (IQR) | 294 | 68.6 (34.3-141.4) | 70 | 64.6 (32.1-127.0) | 224 | 73.9 (35.2-148.6) | 0.24 |

Abbreviations: HADS-A= Hospital Anxiety Depression Scales – Anxiety; HADS-D= Hospital Anxiety Depression Scales – Depression; IQR= Interquartile range; MMSE= Mini-Mental State Examination; n= Number; OA= Osteoarthritis; SD= Standard deviation.

p-value of observed differences between groups with and without OA. Differences in means were tested using Independent Sample T-Tests for normally distributed variables. Differences in medians were tested using Mann Whitney U Tests for skewed continuous variables and differences in percentages were tested using Pearson Chi-square tests for categorical variables.

Quality of life

In the full sample, the QoL index score was 0.80 (IQR=0.73-1.00) and 0.85 (IQR=0.73-1.00) at baseline and at follow-up respectively. At baseline, participants with and without OA did not differ significantly in terms of the QoL index score (Table 2). At follow-up, participants with and without the condition did also not differ significantly in QoL (data not shown). Data on QoL at baseline as well as follow-up were available for 276 participants. In this group, the change in QoL between baseline and follow-up, on average, was 0.02 (SD=0.16). The change in QoL over time did not significantly differ between participants with and without OA (OA: Mean=0.02, SD=0.15 versus non-OA: Mean=0.02, SD=0.16; p=0.76).

Table 2. Quality of life in older adults with and without osteoarthritis at baseline. a.

| All participants (n=294) |

Participants with OA (n=70) |

Participants without OA (n=224) |

p-value b | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| QoL index score (0-1) (Median (IQR)) | 0.80 (0.73-1.00) | 0.80 (0.73-1.00) | 0.80 (0.73-1.00) | 0.63 |

| Mobility (n (%)) | 0.27 | |||

| No problem | 216 (73.5) | 55 (78.6) | 161 (71.9) | |

| Some problem | 78 (26.5) | 15 (21.4) | 63 (28.1) | |

| Confined to bed | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Self-care (n (%)) | 0.90 | |||

| No problem | 272 (92.5) | 65 (92.9) | 207 (92.4) | |

| Some problem | 22 (7.5) | 5 (7.1) | 17 (7.6) | |

| Unable to perform | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Usual activities (n (%)) | 0.40 | |||

| No problem | 228 (77.6) | 57 (81.4) | 171 (76.3) | |

| Some problem | 64 (21.8) | 12 (17.1) | 52 (23.2) | |

| Unable to perform | 2 (0.7) | 1 (1.4) | 1 (0.4) | |

| Pain/discomfort (n (%)) | 0.84 | |||

| No | 128 (43.5) | 32 (45.7) | 96 (42.9) | |

| Moderate | 163 (55.4) | 37 (52.9) | 126 (56.3) | |

| Extreme | 3 (1.0) | 1 (1.4) | 2 (0.9) | |

| Anxiety/depression (n (%)) | 0.37 | |||

| No | 219 (74.5) | 55 (78.6) | 164 (73.2) | |

| Moderate | 75 (25.5) | 15 (21.4) | 60 (26.8) | |

| Extreme | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

Abbreviations: IQR= Interquartile range; n=Number; OA= Osteoarthritis; QoL= Quality of life.

p-value of observed differences between groups with and without OA. For these analyses, Pearson Chi-square tests were used.

Analyses regarding the Edwards-Nunnally Index showed that the majority of participants (77.5%) did not significantly change in terms of QoL between baseline and follow-up. Quality of life did significantly decline and improve over time in 19 (6.9%) and 43 (15.6%) participants respectively. The proportion of persons with a decline in QoL between baseline and follow-up did not differ between the OA-group (8.3%) and the non-OA group (6.5%) (p=0.62).

Perceived neighbourhood problems

On average, the perceived neighbourhood problem index score was 11.1 (SD=2.6) in the full sample. Participants with OA did not perceive significantly more neighbourhood problems compared to their counterparts without OA (OA: Mean=11.1 SD=2.6 versus non-OA: Mean=11.1, SD=2.7; p=0.97). Participants with OA did not report a specific neighbourhood problem more than participants without OA (data not shown).

Quality of life and perceived neighbourhood problems

The cross-sectional associations of QoL with perceived neighbourhood problems at baseline and at follow-up were not statistically significant in the full sample (Bbaseline=-0.003; p=0.37 and Bfollow-up=-0.004; p=0.35) and did not differ between older adults with and without OA.

In the full sample, QoL was not significantly associated with one specific perceived neighbourhood problem. The perception of assaults and muggings and traffic as neighbourhood problems was significantly associated with lower QoL at baseline in older adults with OA (Bassaults/muggings=-0.153; p=0.03 and Btraffic=-0.091; p<0.05). In older adults without OA, these associations were less strong and were not statistically significant (Bassaults/muggings=-0.021; p=0.44 and Btraffic=0.003; p=0.91).

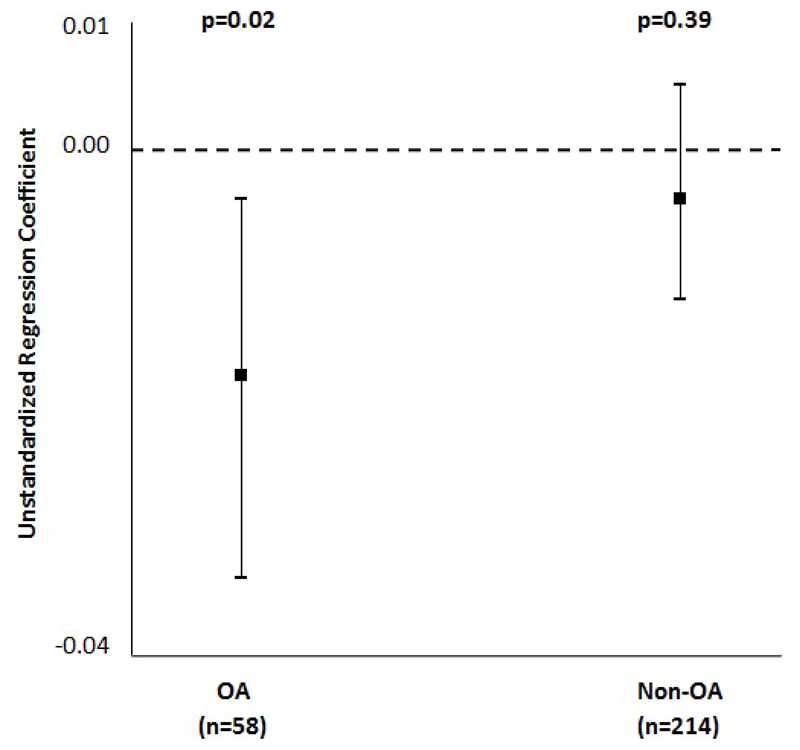

A trend for a negative association between change in QoL over time (continuous measure) and perceived neighbourhood problems was found in the full sample (B=-0.01; p=0.08). A significant OA by perceived neighbourhood problem interaction effect on the change in QoL over time was observed (p=0.09). The perception of more neighbourhood problems was associated with a stronger decrease in QoL over time in participants with OA (B=-0.018; p=0.02) than in those without the condition (B=-0.004; p=0.39) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The association of change in quality of life over time (continuous measure) with perceived neighbourhood problems stratified for osteoarthritis. a-c.

a Abbreviations: n= Number; OA= Osteoarthritis; p= p-value.

b This figure shows the results of two multiple linear regression analyses in which the association of change in quality of life over time (continuous measure) with perceived neighbourhood problems was assessed in older adults with and without osteoarthritis. The unstandardized regression coefficient of perceived neighbourhood problems is presented. Error bars represent 95%-confidence intervals.

c The associations are adjusted for age, sex (reference category: men), partner status (reference category: no partner), educational level (reference category: not better educated than secondary education), number of chronic diseases (reference category: no chronic diseases other than osteoarthritis), anxiety (reference category: not anxious), depression (reference category: not depressed), and general cognitive functioning (reference category: no cognitive impairment).

In the full sample, none of the specific perceived neighbourhood problems was significantly associated with change in QoL over time (continuous measure). The perception of traffic as a neighbourhood problem was significantly associated with a decrease in QoL over time in participants with OA (B=-0.087; p=0.03). This relationship was positive and not statistically significant in older adults without the condition (B=0.008; p=0.73).

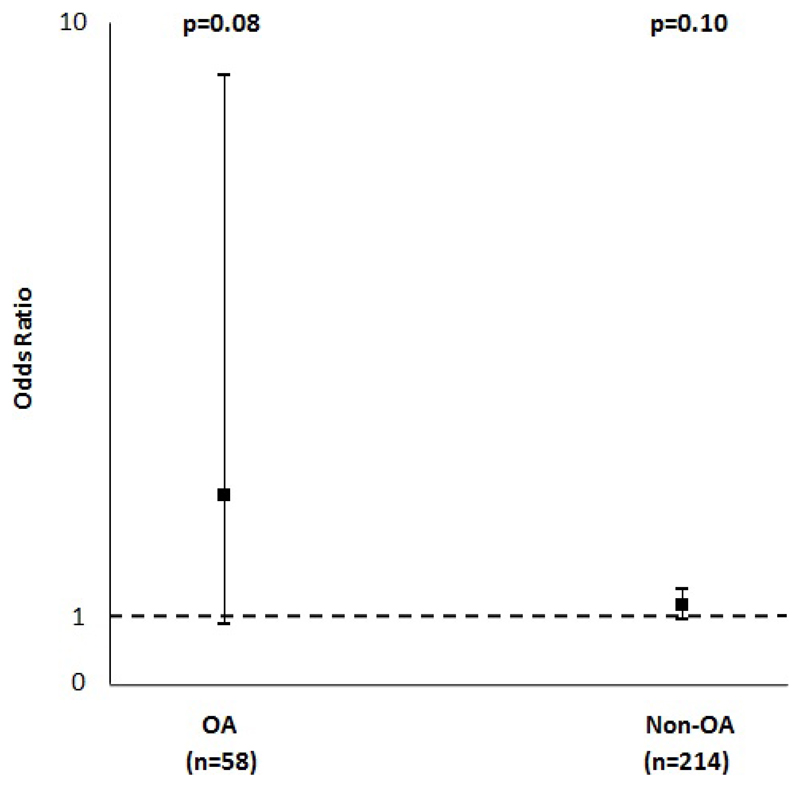

Logistic regression analyses showed that participants who perceive more neighbourhood problems are more likely to have a significant decline in QoL between baseline and follow-up, as indicated by the Edward-Nunnally Index, than those who perceive less neighbourhood problems (OR=1.29, 95% CI=1.10-1.52). There was a trend for an association between change in QoL over time (dichotomous measure) and perceived neighbourhood problems in older adults with OA (OR=2.84; 95% CI=0.88-9.20). This association was less strong and not statistically significant in older adults without OA (OR=1.17, 95% CI=0.97-1.42) (Figure 2). Compared to participants without OA, participants with OA were more likely to have a significant decline in QoL over time, when they perceive more neighourhood problems.

Figure 2. The association of change in quality of life over time (dichotomous measure) with perceived neighbourhood problems stratified for osteoarthritis. a-c.

a Abbreviations: n= Number; OA= Osteoarthritis; p= p-value.

b This figure shows the results of two logistic regression analyses in which the association of change in quality of life over time (dichotomous measure) with perceived neighbourhood problems was assessed in older adults with and without osteoarthritis. The odds ratio of perceived neighbourhood problems is presented. Error bars represent 95%-confidence intervals.

c The associations are adjusted for age, sex (reference category: men), partner status (reference category: no partner), educational level (reference category: not better educated than secondary education), number of chronic diseases (reference category: no chronic diseases other than osteoarthritis), anxiety (reference category: not anxious), depression (reference category: not depressed), and general cognitive functioning (reference category: no cognitive impairment).

Participants who perceived smells and fumes (OR=3.42, 95% CI=1.03-11.41), disturbance by children or youngsters (OR=3.70; 95% CI=1.19-11.46), and noise (OR=3.52, 95% CI=1.19-10.42) were more likely to have a significant decline in QoL between baseline and follow-up. The associations of change in QoL over time (dichotomous measure) and specific perceived neighbourhood problems did not differ between participants with and without OA.

Mediating role of outdoor physical activity

Analyses did not show a mediation effect of outdoor PA in the relationship between QoL and perceived neighbourhood problems in the full sample at baseline and at follow-up. Only condition (c) of Baron and Kenny [30] was fulfilled (see “Statistical analyses”) at baseline as well as follow-up. Analyses also showed that outdoor PA did not mediate the association of QoL with perceived neighbourhood problems in both the OA-group as well as the non-OA group.

Discussion

This study examined the association of QoL with perceived neighbourhood problems in older adults with and without OA, and assessed whether this relationship was stronger in those with OA. The results showed that the cross-sectional association of QoL with perceived neighbourhood problems did not differ between older adults with and without OA. The findings showed that the perception of more perceived neighbourhood problems was associated with a stronger decrease in QoL over time in older adults with OA than in those without the condition.

The current study provides some supportive evidence for the environmental docility hypothesis, which states that the less competent the individual, the greater the impact of environmental factors on that individual (Lawton, 1986; Lawton and Nahemow, 1973). Due to the experience of more pain, disability and functional limitations, older adults with OA might be more vulnerable to environmental demands and might be less able to overcome neighbourhood problems than those without the condition. The results suggest that older adults with OA are less able to deal with perceived neighbourhood problems in comparison to their counterparts without OA and, as a consequence, their QoL decreases more. A possible explanation could be that older adults with OA experience more difficulties with regard to moving outdoors and participating in outdoor PA when they perceive more neighbourhood problems, and that this results in poor QoL (Forsyth et al., 2009; Iwarsson, 2005; Shumway-Cook et al., 2003). However, this study showed that outdoor PA did not mediate the relationship between QoL and perceived neighbourhood problems in older adults with OA as well as in older persons without the condition. Contrary to other studies (for a review, see Van Cauwenberg et al., 2011), the perception of neighbourhood problems was not significantly associated with PA in our study. The perceived neighbourhood problems in our study were mainly related to safety issues, and were not only physical barriers. Physical environmental barriers, such as hilly terrain, lack of resting places, and poor street conditions, are often found to be barriers for PA in older adults with and without disabilities (Dawson et al., 2007; Rosenberg et al., 2013; Strath et al.,2007). It could be that the association of QoL and neighbourhood problems is rather mediated by fear of moving outdoors and unmet PA needs (Rantakokko et al., 2010), than by the self-reported quantity of outdoor PA.

Osteoarthritis is the most prevalent joint disease in older adults (Brooks, 2012; Jinks et al., 2002; Vos et al., 2012). It is the fastest increasing musculoskeletal condition worldwide and increases in life expectancy and aging populations are expected to make OA the fourth leading cause of disability by the year 2020 (Brooks, 2012; Woolf and Pleger, 2003). Knowledge on the relationships between the neighbourhood environment, PA and QoL in older adults with OA is needed to anticipate this development and to plan environments that promote PA and QoL of these individuals. To our knowledge, this is the first study that examines the relationships between perceived neighbourhood problems, outdoor PA, and QoL in older adults with and without OA in the general population. The current study did not only focus on cross-sectional associations between perceived neighbourhood problems, outdoor PA and QoL, but also considered the influence of perceived neighbourhood problems on change in QoL over time. This study has several strengths, including extensive phenotyping of study participants according to strict study protocols, and by a highly trained research team.

Some limitations has to be acknowledged as well. First, the sample size in the current study was fairly small, which resulted in low statistical power. Second, the perception of neighbourhood problems was assessed in 2008 using a postal survey, whereas OA, outdoor PA, QoL and the covariates were assessed on later occasions. Based on previous research (Hertfordshire County Council, 2016), it has been assumed that the perception of neighbourhood problems remained stable between the postal survey and the EPOSA measurements, but this time-gap and the small sample size might have made it harder to gauge the true size of the associations between perceived neighbourhood, outdoor PA and QoL in older adults with and without OA. Finally, another limitation is related to the geographical distribution of the study sample. The study sample is drawn from a single county and the participants in this study cannot be considered entirely typical of all men and women of this age in the UK, because they have continued to live in the county of their birth (Syddall et al., 2005). However, participants of the HCS have been shown to be very similar to those in the nationally representative Health Survey for England on a range of characteristics (Syddall et al., 2005).

In this study, the associations between perceived neighbourhood problems, self-reported outdoor PA and QoL were examined. Future research should also focus on associations between QoL, objectively measured PA, and objectively measured neighbourhood problems. For example, future studies could make use of accelerometers and Global Position System devices to objectively measure outdoor PA in the neighbourhood. Neighbourhood problems could be objectively measured by using official crime reports, noise exposure measures, and traffic data. The study sample in our study was drawn from a small geographical area, which is characterized by high levels of perceived area satisfaction and low levels of area deprivation compared to other parts of the UK (Hertfordshire County Council, 2016; Hertfordshire Local Information System (HertsLIS), 2016; McLennan et al., 2011; Noble et al., 2008). The associations between QoL and perceived neighbourhood problems might be stronger in less affluent and satisfied areas. Future studies in different geographical areas are needed to examine this.

In conclusion, this study shows that the perception of more neighbourhood problems was associated with a stronger decrease in QoL over time in older adults with OA than in those without OA. Older adults were more likely to have a significant decline in QoL over time than those without the condition, when they perceive more neighbourhood problems. Older adults with OA may be less able to deal with perceived neighbourhood problems and a more challenging environment in comparison to their counterparts without OA and, as a consequence, their QoL decreases more over time. In order to improve QoL of healthy and functionally-impaired older adults, such as those with OA, it is important that policymakers and city planners are in close contact with the residents of a neighbourhood to monitor and to address their perceived neighbourhood problems.

Acknowledgements

The Hertfordshire Cohort Study is funded by the Medical Research Council of Great Britain, Arthritis Research UK, the British Heart Foundation and the International Osteoporosis Foundation.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions. SAGE Publications, Inc; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Ali R, Binmore R, Dunstan S, et al. General Household Survey 2007. Office for National Statistics; Newport: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Altman RD. Classification of Disease: Osteoarthriti. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1991;20:40–47. doi: 10.1016/0049-0172(91)90026-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks PM. Impact of osteoarthritis on individuals and society: how much disability? Social consequences and health economic implication. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2012;14:573–577. doi: 10.1097/00002281-200209000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks R, Rabin R, de Charro F. The measurement and valuation of health status using EQ-5D: a European perspective. Kluwer Academic Publishers; Dordrecht: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Dawson J, Hillsdon M, Boller I, et al. Perceived barriers to walking in the neighbourhood environment and change in physical activity over 12 months. Br J Sports Med. 2007;41:562–568. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2006.033340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Groot IB, Bussmann JB, Stam HJ, et al. Actual everyday physical activity with end-stage hip or knee osteoarthritis compared with healthy controls. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2008;16:436–442. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2007.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolan P. Modeling valuations for EuroQol health states. Med Care. 1997;35:1095–1108. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199711000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. ‘Minimental state’: A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsyth A, Oakes JM, Lee B, et al. The built environment, walking, and physical activity: is the environment more important to some people than others? Transportation Research Part D. 2009;14:42–49. [Google Scholar]

- Grandy S, Fox KM, SHIELD Study Group Changes in health status (EQ-5D) over 5 years among individuals with and without type 2 diabestes mellitus in the SHIELD longitudinal study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2012;10:99. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-10-99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hertfordshire County Council. Hertfordshire Resident’s Survey Council and democracy – Working for you – Open data – Your views – Views of local area – Autumn 2015. Hertfordshire County Council; [Accessed: September, 2016]. http://www.hertfordshire.gov.uk/your-council/work/opendata/yrviews/ [Google Scholar]

- Hertfordshire Local Information System (HertsLIS) People and Place – Deprivation – Indices 2010. Hertfordshire Local Information System (HertsLIS); [Accessed: September, 2016]. Indices of deprivation 2010. http://www.hertslis.org/peoppla/depriv/iod2010/ [Google Scholar]

- Iwarsson S. A long-term perspective on person-environment fit and ADL dependence among older Swedish adults. Gerontologist. 2005;45:327–336. doi: 10.1093/geront/45.3.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwarsson S, Wahl H-W, Nygren C, et al. Importance of the home environment for Healthy Aging: Conceptual and methodological background of the European ENABLE-AGE Project. Gerontologist. 2007;47:78–84. doi: 10.1093/geront/47.1.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jinks C, Jordan K, Croft P. Measuring the population impact of knee pain and disability with the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) Pain. 2002;100:55–64. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(02)00239-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawton MP. Environment and aging. Center for the Study of Aging; Albany, NY: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Lawton MP, Nahemow L. Ecology and the aging process. In: Eisendorfer C, Lawton MP, editors. The psychology of adult development and aging. American Psychiatry Association; Washington, DC: 1973. pp. 619–674. [Google Scholar]

- Levasseur M, Desrosiers J, St-Cyr Tribble D. Subjective quality of life predictors for older adults with physical disabilities. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2008;87:830–841. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0b013e318186b5bd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levasseur M, Généreuz M, Bruneau JF, et al. Importance of proximity to resources, social support, transportation and neighbourhood security for mobility and social participation in older adults: results from a scoping study. BMC Public Health. 2015;23:503. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-1824-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLennan D, Barnes H, Noble M, et al. The English Indices of Deprivation 2010. Department for Communities and Local Government; London: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Noble M, McLennan D, Wilkinson D, et al. The English Indices of Deprivation 2007. Department for Communities and Local Government; London: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Peat G, McCarney R, Croft P. Knee pain and osteoarthritis in older adults: a review of community burden and current use of primary health care. Ann Rheum Dis. 2001;60:91–97. doi: 10.1136/ard.60.2.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puts MTE, Shekary N, Widdershoven G, et al. What does quality of life mean to older frail and non-frail community-dwelling adults in the Netherlands? Qual Life Res. 2007;16:263–277. doi: 10.1007/s11136-006-9121-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rantakokko M, Iwarsson S, Kauppinen M, et al. Quality of Life and Barriers in the Urban Outdoor Environment in Old Age. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58:2154–2159. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03143.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg DE, Huang DL, Simonovich SD, et al. Outdoor built environment barriers and facilitators to activity among midlife and older adults with mobility disabilities. Gerontologist. 2013;53:268–279. doi: 10.1093/geront/gns119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salaffi F, Carotti M, Stancati A, et al. Health-related quality of life in older adults with symptomatic hip and knee osteoarthritis: a comparison with matched healthy controls. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2005;17:225–263. doi: 10.1007/BF03324607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shumway-Cook A, Patla A, Stewart A, et al. Environmental components of mobility disability in community-living older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51:393–398. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speer DC, Greenbaum PE. Five methods to for computing significant individual client change and improvement rates: Support for an individual growth curve approach. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1995;63:1044–1048. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.63.6.1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stel VS, Smit JH, Pluijm SM, et al. Comparison of the LASA Physical Activity Questionnaire with a 7-day diary and pedometer. J Clin Epidemiol. 2004;57:252–258. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2003.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strath S, Isaacs R, Greenwald MJ. Operationalizing environmental indicators for physical activity in older adults. J Aging Phys Act. 2010;15:412–424. doi: 10.1123/japa.15.4.412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syddall HE, Sayer AA, Dennison EM, et al. Cohort profile: The Hertfordshire Cohort Study. Int J Epidemiol. 2005;34:1234–1242. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyi127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tombaugh TN, McIntyre NL. The mini mental state examination: a comprehensive review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1992;40:922–935. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1992.tb01992.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Cauwenberg J, De Bourdeaudhuij I, De Meester F, et al. Relationship between the physical environment and physical activity in older adults: A systematic review. Health Place. 2011;17:458–469. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2010.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Pas S, Castell MV, Cooper C, et al. European project on osteoarthritis: design of a six-cohort study on the personal and societal burden of osteoarthritis in an older European population. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2013;14:138. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-14-138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Pas S, Schaap LA, Castell MV, et al. Availability and use of neighbourhood resources by older people with osteoarthritis: Results from the European Project on OSteoArthritis. Health Place. 2016;37:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2015.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Schoor NM, Zambon S, Castell MV, et al. Impact of clinical osteoarthritis of the hip, knee and hand on self-reported health in six European countries: the European Project on OSteoArthritis. Qual Life Res. 2016;25:1423–1432. doi: 10.1007/s11136-015-1171-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visser M, Brychta RJ, Chen KY, et al. Self-reported adherence to the physical activity recommendation and determinants of misperception in older adults. J Aging Phys Act. 2014;22:226–234. doi: 10.1123/japa.2012-0219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vos T, Flaxman AD, Naghavi M, et al. Years lived with disability (YLDs) for 1160 sequelae of 289 diseases and injuries 1990-2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380:2163–2196. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61729-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolf AD, Pfleger B. Burden on major musculoskeletal conditions. Bull World Health Organ. 2003;81:646–656. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zigmond A, Snaith R. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:361–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]