Abstract

Cancer arises from a deregulation of both intracellular and intercellular networks that maintain system homeostasis. Identifying the architecture of these networks and how they are changed in cancer is a pre-requisite for designing drugs to restore homeostasis. Since intercellular networks only appear in intact systems, it is difficult to identify how these networks become altered in human cancer using many of the common experimental models. To overcome this, we used the diversity in normal and malignant human tissue samples from the Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database of human breast cancer to identify the topology associated with intercellular networks in vivo. To improve the underlying biological signals, we constructed Bayesian networks using metagene constructs, which represented groups of genes that are concomitantly associated with different immune and cancer states. We also used bootstrap resampling to establish the significance associated with the inferred networks. In short, we found opposing relationships between cell proliferation and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transformation (EMT) with regards to macrophage polarization. These results were consistent across multiple carcinomas in that proliferation was associated with a type 1 cell-mediated anti-tumor immune response and EMT was associated with a pro-tumor anti-inflammatory response. To address the identifiability of these networks from other datasets, we could identify the relationship between EMT and macrophage polarization with fewer samples when the Bayesian network was generated from malignant samples alone. However, the relationship between proliferation and macrophage polarization was identified with fewer samples when the samples were taken from a combination of the normal and malignant samples.

Keywords: TCGA, Bayesian Networks, Intercellular networks, Oncogenesis

Introduction

Tissues are dynamic structures constructed from a variety of different cell types that each have a shorter lifespan than the organism and each contribute a specific function necessary for host survival. The dynamic maintenance of an optimal state of existence of cells and tissues that constitute the organism is a central concept in physiology called Homeostasis. Homeostasis is maintained by regulatory networks that are encoded within the system at different levels of biological organization and that restore the system following a perturbation. For instance, p53 is part of an intracellular regulatory network that restores the integrity of the genetic information of a cell following DNA damage.1 Adherens junctions link an intracellular network to an extracellular network that restores the integrity of an epithelial barrier upon disruption.2,3 Innate and adaptive immunity comprise an extracellular regulatory network that restores the composition of cells within a tissue upon infection by a foreign pathogen.4 While many of the components that constitute these regulatory networks are known, identifying how information is passed within these regulatory networks to maintain homeostasis, expressed in terms of the topology of the network, remains a challenge.5 This challenge stems from the fact that identifying the network topology requires an integrated system and that the roles that individual components play in the network depend on the state of the system, as it is perturbed from homeostasis.

These regulatory networks influence the fate of cells within a biological system but can also become rewired in disease. Cells that are unable to repair DNA damage undergo programmed cell death. Disruption of an epithelial barrier promotes the migration and proliferation of cells to restore the barrier.2 Innate and adaptive immunity kills cells that have been infected by a pathogen. Oncogenesis, in many ways, represents a subversion of the regulatory networks that act to maintain homeostasis in the tissue microenvironment.6,7 These subversions include rewiring of the internal circuitry of a cell that changes how a cell responds to biochemical cues present within the environment or rewiring of extracellular networks that changes how different cells communicate to organize tissue function.8–10 Moreover the subversion of these regulatory networks occur through a pseudo-random process of DNA damage and repair.11 The presence of these regulatory networks that select the fate of a cell within the tissue coupled with the random nature of DNA damage and repair suggests that cancer can be viewed as an evolutionary process.12 While much effort has focused on how intracellular networks change during oncogenesis, the clinical emergence of immunotherapies for cancer highlights the importance of extracellular networks in maintaining tissue homeostasis.13 Given the distributed nature of the immune system, we hypothesized that oncogenesis is associated with altering extracellular networks in similar ways despite the fact that cancers may arise in different anatomical locations. In support of this hypothesis, comparing secretomes derived from a collection of breast cancer cell lines suggests that malignant cells that arise in the same anatomical location but different individuals alter extracellular networks in similar ways.14 However to test this hypothesis more directly, we first need to be able to identify relevant extracellular networks in intact systems.

The recent increases in size and information content of genomic datasets have enabled using probabilistic inference methods to identify relationships out of the data that could not be observed using simpler statistical techniques.15 However to infer regulatory networks, we need to be able to identify the direction of information flow within the network, that is the causal relationships between interacting components. One of the methods that can be used to identify the topology of a causal network in an unbiased way is through the use of algorithms that identify Bayesian networks.16 Bayesian networks are a type of directed acyclic graphs (DAG), where each node represents a random variable and each edge represents a causal relationship between two nodes. Algorithms for reconstructing Bayesian networks have previously been used to model signaling pathways within cells17, to identify known DNA repair networks in E. coli using microarray data7 and to identify simple phosphorylation cascades in T lymphocytes using flow cytometry data.18,19

The goal of our study was two fold. First, we asked whether Bayesian inference algorithms could be used to identify changes in the extracellular regulatory network associated with tissue homeostasis that occur in conjunction with oncogenesis, a process that occurs over months or years, and that is reflected in changes in cell populations within a tissue and cellular developmental processes. Second, we tested whether these networks are similar or different in cancers that arise in different anatomical locations. In particular, we looked at the interplay of cellular proliferation, epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), and immune surveillance, which are processes commonly associated with oncogenesis. To gain insight into oncogenesis in humans, we used gene expression data from homogenized tissue samples that were obtained from malignant and matched normal tissue acquired as part of the Cancer Genome Atlas study. We reasoned that homogenized tissue samples, in addition to informing the genetic landscape in malignant cells, can also provide insight into cellular composition within a tissue. To improve the computational tractability of Bayesian network inference6, we inferred networks using metagene constructs, which represent an aggregation of the genes associated with the processes of interest, instead of individual genes. Since Bayesian networks are conventionally inferred from data acquired as a function of time and longitudinal data were not available, we used data from multiple patient samples to mimic temporal data, assuming that cross-sectional data represent random samples from a common disease progression. In short, we found that cellular proliferation and EMT had opposing relationships with macrophage polarization in invasive breast cancer, with increased proliferation being associated with classically activated macrophages (M1) and EMT being associated with alternatively activated macrophages (M2). We found that sample size and complexity affected the resulting Bayesian networks, with smaller sample sizes resulting in less complex networks, while changes in the composition of the sample influenced the relationships that were seen. When we expanded this study to other forms of cancer, we inferred similar networks in lung squamous cell carcinoma and colon adenocarcinoma, but not in glioblastoma multiform, after controlling for the relative size and diversity of the underlying datasets.

Methods

Data Acquisition

Gene expression values in normal and malignant tissues were obtained as part of the Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA)20. In short, homogenized samples taken from primary tumors after diagnosis but before treatment or from matched normal tissue samples were analyzed using on the Agilent G4502A 07 microarray chip. Gene expression was determined, and genes were normalized to a log2 scale using the RMA (Robust Multichip Average) method21, and were normalized across the cohort sample to generate z-scores for each gene. Level 3 tissue microarray data were downloaded for the invasive breast carcinoma samples (BC, tumors = 599, normals = 65), glioblastoma multiform (GBM, tumors = 482, normals = 10), lung squamous cell carcinoma (LUSC, tumors = 155, normals = 0), and colon adenocarcinoma (COAD, tumors = 174, normals = 9) samples. In this case, normals represent microarray data from normal, non-cancerous tissue. Genes of interest were identified, and samples missing any of the genes were eliminated from the study.

Metagene calculations

We used metagene constructs to infer changes in cellular infiltration and biological processes associated with oncogenesis in biopsy samples. A metagene is the expression and aggregation of individual genes observed by microarray data, and can represent either cell infiltration, cell polarization, or a cellular process. The collection of genes associated with each metagene is defined a priori by genes that are either known to be uniquely upregulated or downregulated during a cellular process or during cell differentiation. These metagene constructs serve two purposes in this study. First, it simplifies the data, bringing it together in such a way that it can more easily understood. A DAG containing fourteen nodes is much easier to make sense of then a DAG containing nearly three hundred nodes and is much more computationally tractable.6 The reduced computational expense enables one to test hypothesis related to network topology via simulations, for instance, the statistically significance of an edge can be obtained by comparing how often an edge is inferred from the TCGA data relative to a dataset that has no information, which is the null hypothesis. Secondly, it serves as a means of helping to eliminate error. Microarray data is noisy, with the result given being the summation of both the true gene expression as well the noise inherit to the assay (i.e., lab variability, experimenter skill, sensitivity of the machine, and batch of reagents used).7 The metagene helps eliminate this error as it averages across several genes. The genes that make up each metagene are identified in Table S1.

The presence of T cells, Natural Killer cells, and macrophages in the tumor microenvironment were represented by immune infiltrate metagenes.22–25 Similarly, the EMT26 and proliferation27 metagenes were intended to represent the extent of activation of these biological processes associated with cancer. The values for an immune infiltrate, the EMT, and the proliferation metagenes were calculated based on the average z-score, a centered and variance normalized value for gene expression.

In addition to cell recruitment, various immune cells can assume different phenotypes based on the biochemical cues present within the tissue microenvironment. Specifically, we represented the polarization of T helper cells into one of four subsets and of macrophages into one of two subsets.24,28 The metagene expression “signal” associated with changes in cell polarization were calculated based on an approximate Bayesian calculation of the probability for polarization state i (Mi)25,

| (1) |

where m represents the total number of possible polarization states. In equation 1, P(Y|Mi) is the likelihood that a pattern of mutually exclusive gene expression associated with polarization state i is observed and defined by:

| (2) |

where yj, ȳj, and σy equal the observed expression, mean value, and standard deviation of the jth gene in the polarization metagene Mi. The second term is the corresponding product for genes not associated with a given polarization metagene, denoted as M̄i. The prior probability that polarization state Mi exists, denoted as P (Mi), was specified as 1/m. Products were used as we assumed the expression of the genes to be mutually inclusive, with a polarization only being considered when all of the genes for it were upregulated when compared to the gene expression of the alternative polarizations. All calculations were performed in R software version 2.14.1 (http://www.r-project.org29), which are described in a Supplemental Sweave document (Supplement.Rnw).

Inference of Bayesian networks

Bayesian networks can be used to infer causality among a sequence of events that are ordered in time. To infer causality associated with oncogenesis using the cross-sectional The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) study, we assumed that the normal and tumor tissue samples represent random samples in time derived from a single dynamic disease progression that occurs in a defined anatomical location. Bayesian networks were generated from “signals” derived from the metagene constructs using an Incremental Associated Markov Blanket (IAMB) as described by Tsamardinos30 and implemented in R. In short, IAMB is made up of two phases - a forward stage where a network is generated in such a way that it maximizes the conditional independence of the nodes, and a backwards phase where it is removes any remaining conditionally independent connections. Confidence for the node edges was calculated using a bootstrap resampling method that included 100,000 replications31. For each replicate, patient data were randomly sampled with replacement n times, where n is the starting number of patient samples in the dataset, and a network was generated from the new dataset. Lines were only included if they had a p-value of less than 0.01. Bayesian networks were generated for all cancer sets. To assess how the complexity of the TCGA study samples influenced network generation, we also generated networks for smaller subsets of in data, including the tumor samples only or a percentage of the entire dataset (75%, 50%, 25%). These percentage subsets were generated by sampling without replacement from the entire cohort. Model generation and averaging were performed in R using the boot.strength() and the average.network() methods from the bnlearn package. Since longitudinal data were not available, we used patient-matched normal and malignant tissue samples obtained from a large cohort of patients to simulate temporal data. We assume these cross-sectional samples from normal and diseased tissue represents random samples from a common temporal trajectory associated with oncogenesis.

Statistics

Patient samples and genes were clustered using the Ward method. Principal component analysis was performed on the data using the prcomp() function, with scale set to false, and rotational data for the genes were returned. Differences in node connectivity and average Markov blanket size were compared using two way ANOVA’s. Distributions between cancer group 1 and cancer group 2 were compared using the Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxon test. P-values for the Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxon test that were less than 0.01 were considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Identification of patient sample subtypes and metagenes

While the genes we used to identify the different metagenes were created using human data, we wanted to verify their usefulness to distinguish between patient samples and to see if the genes did, in fact, vary together. To test if the genes selected could distinguish patient samples obtained from cancer and non-cancer tissue, hierarchical clustering was performed on the genes used in the metagenes (Fig S1), and the patient samples were divided into three groups. The patient samples, with a couple of exceptions, associated with one of three groups, one normal group and two cancer groups. This suggests that the patient samples, at least, can be separated by the genes chosen for the metagenes, with normal samples being separated from the tumor samples, and the tumor samples being split into two groups.

In order to better understand how the different metagenes explained the variance samples observed, Principal component analysis was performed. It was found that 54% of the variance was explained in the first four principal components (Fig S2). It should be noted that there are several genes that cluster near the origin in all 4 principal components. These genes could potentially be removed, as they are uninformative with regards to the breast cancer, but were not excluded in this case as they could be informative in other cancers.

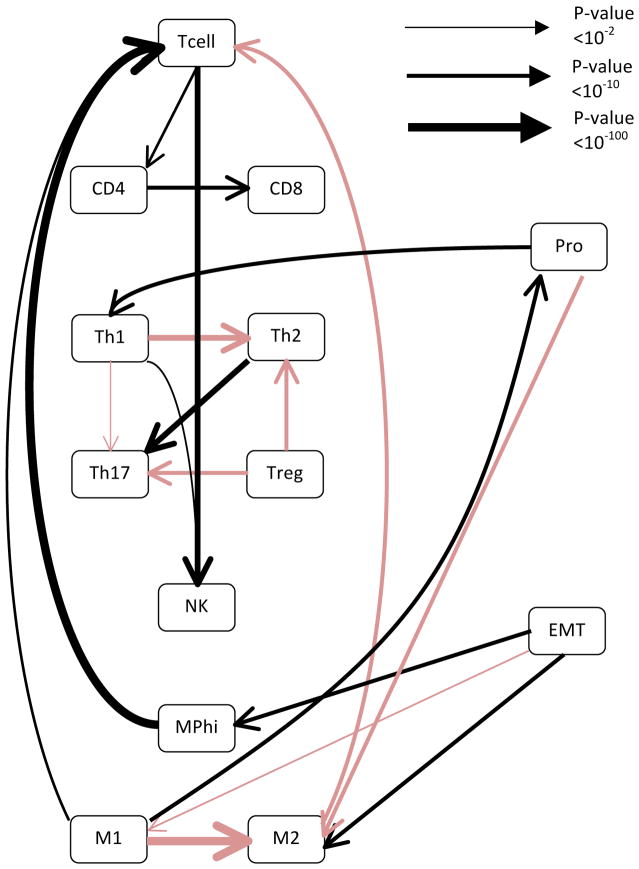

Use of Bayesian networking as a means to identify topology of extracellular control networks

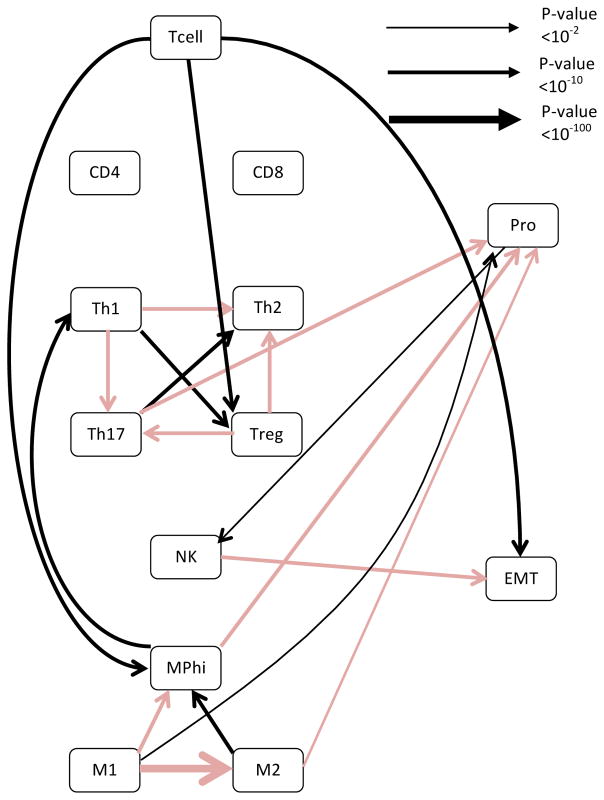

After confirming that the genes naturally cluster into the different metagenes, we asked whether we could observe evidence of crosstalk between the cancer and immune metagenes. To accomplish this, a Bayesian network of the metagenes was generated using an IAMB algorithm. Although Bayesian networks can be used to identify causal relationships between data points, causality can only be inferred if there is either temporal data, or the direction of the edges are known a priori. Since longitudinal cancer biopsies were not available, we used the whole dataset along with the samples obtained from matched normal tissue as a means to simulate temporal disease progression.32 The generated network represented the averaging of 100,000 generated networks, a process that had previously been shown to be a fairly conservative method of identifying edges.31 When the analysis was performed on the whole data set of invasive breast cancer, it was observed that the EMT metagene and the proliferation metagene had reciprocal effects on macrophage polarization, with EMT seemingly being associated with increases in macrophage type 2 polarization (M2) and proliferation being associated with macrophage type 1 polarization (M1) (see Fig 1 and Table S2). This is interesting as macrophage polarizations are thought to play opposing roles in cancer immunosurveillance. The M1 polarization is the classical macrophage, which serves to scavenge cell debris and is generally pro-inflammatory.33 In contrast, the M2 polarization is associated with wound healing, suppression of inflammation, and is considered to promote tumor growth.34,35 These relationships are captured in the generated network, with an M1 polarization also being associated with an increase in overall T cell infiltration and M2 being associated with a decrease in T cell infiltration. When the analysis was repeated using only gene expression values derived from tumor samples of invasive breast cancer cohort, the relationships between EMT and macrophage polarization, as well as the relationship between macrophage polarization and T cell infiltration persisted (Fig S3). However, the relationship between macrophage polarization and proliferation was lost. This implies that the relationship between macrophage polarization and proliferation was mostly informed by the change from normal to cancer. It is also worth noting that not all relationships with proliferation were lost with the change from using all samples to only using cancer samples. For instance, the relationship between proliferation and the T helper Type 1 cells (Th1) polarization was maintained, and the confidence was, in fact, increased (p-value < 2E-20 vs. p-value < 1E-14). This suggests that the relationship between the Th1 polarization and proliferation is a relationship inherent to invasive breast cancer, and not simply representing a change from normal to cancer.

Figure 1. Bayesian networks reveal cross-talk among polarized immune subsets and inverse relationships between the proliferation and EMT metagene with regards to macrophage polarization.

Bayesian networks were generated using the entire breast cancer dataset. The network was generated using an IAMB algorithm, with the network representing the average of 100,000 generated Bayesian networks. Black lines represent positive relationships while red lines represent negative relationships. The line thickness is proportional to the negative log of the confidence in the connection, with thicker lines representing a higher confidence. Confidence p values are for each of the edges are listed in Table S2.

Since EMT and proliferation played opposing roles in the Bayesian networks with regards to macrophage polarization, we next wanted to see whether their overall distribution was different in the two cancer groups. It was found that the two groups did differ significantly with regards to their average EMT metagene expression, with group 1 having a higher average expression (p-value < 0.001, Mann-Whitney Wilcox, see Fig S4 panel i). Surprisingly, though the means were much closer together, the difference between the two groups in the average proliferation metagene expression was statistically significant, with group 2 having a higher expression (p-value < 3e-7, see Fig S4 panel j). As would be expected from the Bayesian network, it was found that the two groups did differ significantly with regards to their macrophage polarization, with group 2 having higher levels of M1 polarized macrophages (p-value < 1e-14, Fig S4 panel h). As would be expected with the changes in macrophage polarization, group 1 also had a statistically significant increase in Th2 and Treg polarizations, with Treg being anti-inflammatory and Th2 being commonly opposed to Th1, and Th1 polarization being higher in group 2. These interactions, however, did not appear to be direct effects as indicated by the Bayesian network inference results.

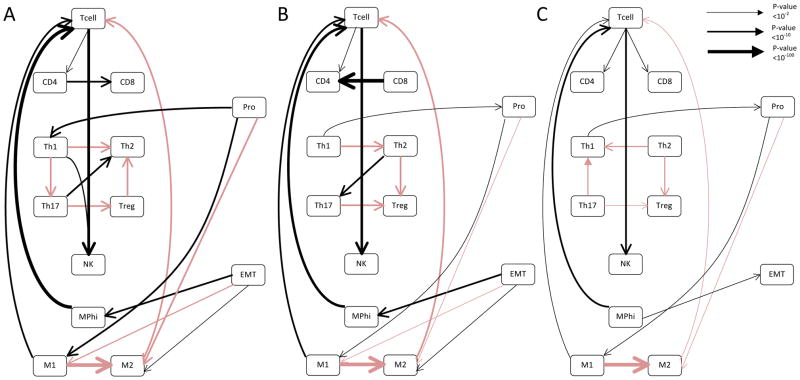

The sample size and diversity of a data set influences network generation and verification of metagene constructs

We next determined the overall effect of sample size and diversity of the TCGA dataset with regards to the generated networks to assess how this approach could be generalized. To accomplish this, we generated mock datasets that represented 75% (see Fig 2a and Table S3), 50% (see Fig 2b and Table S4), or 25% (see Fig 2c and Table S5) of the dataset by drawing randomly without replacement from the whole invasive breast cancer data set. As one would expect, the network appeared to be become progressively less complex as the dataset became smaller. It also appeared that the overall confidence levels associated with the edges fell. Interestingly, when the dataset was reduced to 25%, the relationship between EMT and macrophage polarization was lost, although the relationship between proliferation and macrophage polarization endured. This is consistent with our findings that the relationship between EMT and macrophage polarization was more subtle, and also implies this relationship might not be identifiable with a smaller dataset.

Figure 2. The inferred relationship between EMT and macrophage polarization in the TCGA breast cancer dataset appears to be subtle, and is lost when the network is generated from subsamples of the dataset.

Bayesian networks were generated using random sampling without replacement of the whole data set, with subsamples representing 75% (a), 50% (b), or 25% (c) of the whole breast cancer dataset. In all cases the network was generated using an IAMB algorithm, with the network representing the average of 100,000 generated Bayesian networks. Black lines represent positive relationships while red lines represent negative relationships. The line thickness is proportional to the log of the confidence in the connection, with thicker lines representing a higher confidence. Confidence p values associated with each edge are given in Tables S6, S7 and S8.

The relationship between proliferation and macrophage polarization is interesting, as it was lost with the removal of the normal breast tissue samples but persisted in the 75% and 50% subsets. To better examine the impact of the inclusion of normal samples, we repeated the experiment using only cancer samples (Fig S5). In this case, the relationship between EMT and macrophage polarization was maintained through all datasets. While the relationship between proliferation and macrophage polarization was lost in all subsets, the relationship between proliferation and Th1 polarization was also maintained. This suggests that the inclusion of data from normal tissues was required for the identification of the relationship between proliferation and macrophage polarization. In contrast, the exclusion of data from normal tissue samples allowed us to identify the relationship between EMT and macrophage polarization with a smaller sample size.

In order to get a better idea of the overall effects of changing the complexity and size of the dataset analyzed, 10 replicates of the earlier studies were performed, each containing 100,000 bootstrap samples, and the resulting complexity of the inferred networks was quantified by their average node connectivity and Markov blanket size (Table 1). In this particular case, the amount of samples drawn from either the cancer + normal or cancer only datasets were equal and set based on the percentage of cancer only samples, since we didn’t want differing sample sizes to be a confounding variable. Generally, we made two observations. First, the average Markov blanket did not change between using the entire dataset versus using a smaller size dataset. Although there is a limit as the average Markov blanket size and node connectivity was decreased when comparing the smallest dataset (25%) to the largest dataset (75%, p-value < 0.01). Second, the average Markov blanket was less complex when analyzing cancer only data compared to cancer + normal data (p-value < 0.01). However, confidence decreased with smaller samples sizes due to an increase in the variability.

Table 1. Average connectivity and Markov blanket size of invasive breast cancer subsets.

Mean and standard deviation of average node connections and Markov blanket size were calculated for the whole invasive breast cancer dataset and cancer only invasive breast cancer dataset. Percentages were based on the size of the cancer only datasets. 2-way ANOVA was performed on the data.

| % of Dataset | Cancer + Normal Average node connection | Cancer only Average node connection** | Cancer + Normal Markov blanket size | Cancer only Markov blanket size** |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whole dataset | 2.92 | 2.46 | 3.69 | 3.07 |

| 75% (n = 399) | 2.95 ± 0.06 | 2.61 ± 0.10 | 3.67 ± 0.20 | 3.23 ± 0.17 |

| 50% (n = 266) | 2.87 ± 0.13 | 2.43 ± 0.15 | 3.56 ± 0.18 | 3.21 ± 0.49 |

| 25% (n = 133)* | 2.28 ± 0.12 | 2.15 ± 0.25 | 2.71 ± 0.25 | 2.84 ± 0.64 |

signifies a significant difference between that row and the 75% row.

signifies a significant difference between the cancer only column and the corresponding cancer + normal column. A p-value < 0.01 was considered significant.

One potential concern of the model that we are using is that while certain metagenes are defined independently of each other (for example, immune cell infiltration, proliferation, and EMT), other metagenes, such as immune polarization, are defined as mutually exclusive. For instance, M1 macrophage polarization is defined both by the increased expression of M1 associated genes and by a decrease in M2 associated genes. To test our inference approach, we tested whether the immune polarization networks were informed by the data or constrained by the particular model formulations. In order to test this, we focused on the T helper cell polarizations, and compared the connections generated from real data to the connections derived from metagenes generated from random genes. To accomplish this, we scrambled the genes associated with each polarization subset and repeated the analysis. What we found was a redirection in relationships (specifically Th1 no longer having connections to T helper type 17 (Th17) and T helper type 2 cells) (Fig S6). Furthermore, in the repeated analysis, there was an ambiguity in the nature of the relationship between Th1 and Treg, both positive and negative relationships being identified. However, the overall shape of the graph was consistent across all three gene reshufflings, which suggests that the data plays at least some role in determining the final relationships. Also, the resulting datasets fit with prior studies, which had identified a reciprocal role for Th1 and Th17 in human tumor infiltrates.36

Similar Bayesian networks are identified in other cancers

One of the advantages of using the TCGA study is that it spans many different cancers and samples are processed similarly. We wanted to determine if the relationships we observed were specific to breast cancer, or if similar relationships could be observed in other cancers. In order to do this, we downloaded complete datasets from the lung squamous cell carcinoma, colon adenocarcinoma, and glioblastoma multiform arms of the TCGA study. While glioblastoma technically is not a carcinoma, it had been reported that it does undergo a shift towards a mesenchymal state, resulting in an increase in expression of EMT genes.37

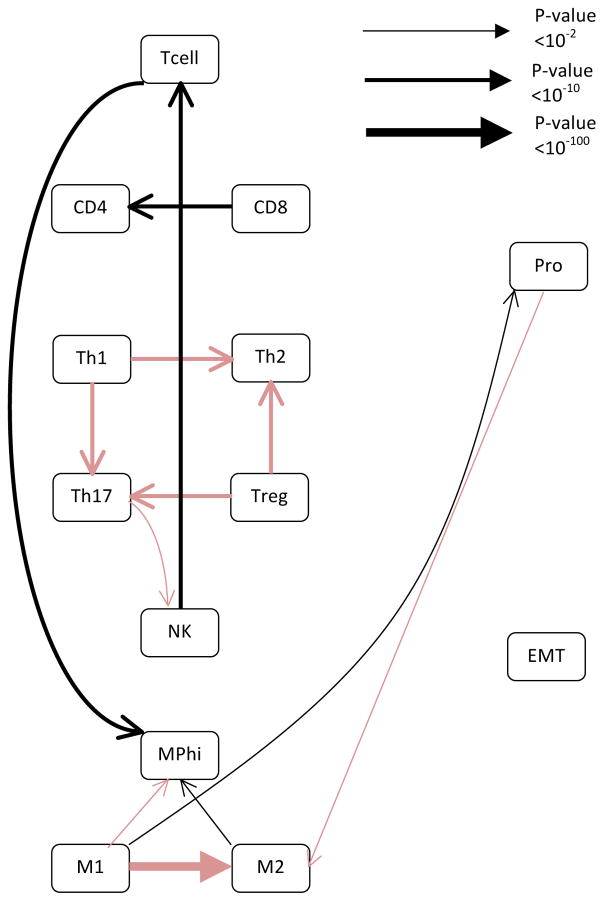

When the Bayesian network is generated using the colon adenocarcinoma dataset, we see the same relationship between proliferation and macrophage polarization (see Fig 3 and Table S6). However, the EMT node is orphaned, having no connections, and the M2 macrophages are associated with an increase in macrophage infiltration, which was not seen in the breast cancer datasets. Overall, the network generated from the colon adenocarcinoma dataset most closely resembled that seen in the smallest generated combined breast cancer dataset. These relationships would be expected, given the size and complexity of the colon adenocarcinoma dataset, which included a few matched normal samples (Table 2).

Figure 3. The network inferred from the TCGA colon adenocarcinoma dataset most closely resembles the smallest sub-sampling of the entire breast cancer dataset.

The network was generated using the same algorithm as Figure 1. Black lines represent positive relationships while red lines represent negative relationships. The line thickness is proportional to the log of the confidence in the connection, with thicker lines representing a higher confidence. Confidence p-values associated with each edge are given in Table S3.

Table 2. Node connectivity and Markov blanket size of all cancer data sets used in study.

Values represent the mean node connectivity and Markov blanket size for the networks generated using the invasive breast cancer, glioblastoma multiform, lung squamous cell carcinoma, and colon adenocarcinoma datasets. The total numbers of tumor and normal samples used in the analysis are also provided.

| Cancer Type | Average node connectivity | Average Markov blanket size | Number of tumor samples | Number of normal samples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Invasive breast carcinoma | 2.77 | 3.69 | 532 | 65 |

| Glioblastoma Multiform | 2.92 | 4.00 | 467 | 10 |

| Lung squamous cell carcinoma | 1.85 | 2.40 | 154 | 0 |

| Colon adenocarcinoma | 2.31 | 2.46 | 154 | 19 |

The network generated from the lung squamous cell carcinoma (see Fig 4 and Table S7) contained the relationship between EMT and macrophage polarization seen in the breast cancer dataset, but did not include the relationship with proliferation. Also, the relationship between proliferation and Th1 polarization was negative, which was the only time this relationship was observed. Despite that, the network closely resembles the one generated from the smallest subsampling we performed of the breast cancer data, which contained only cancer samples and closely mimics the composition of the lung cancer dataset (Table 2).

Figure 4. The network inferred from the TCGA lung squamous cell carcinoma dataset most closely resembles the smallest sub-sampling of the breast cancer dataset using only malignant samples.

The network was generated using the same algorithm as Figure 1. Black lines represent positive relationships while red lines represent negative relationships. The line thickness is proportional to the log of the confidence in the connection, with thicker lines representing a higher confidence. Specific p-values associated with each edge are provided in Table S4.

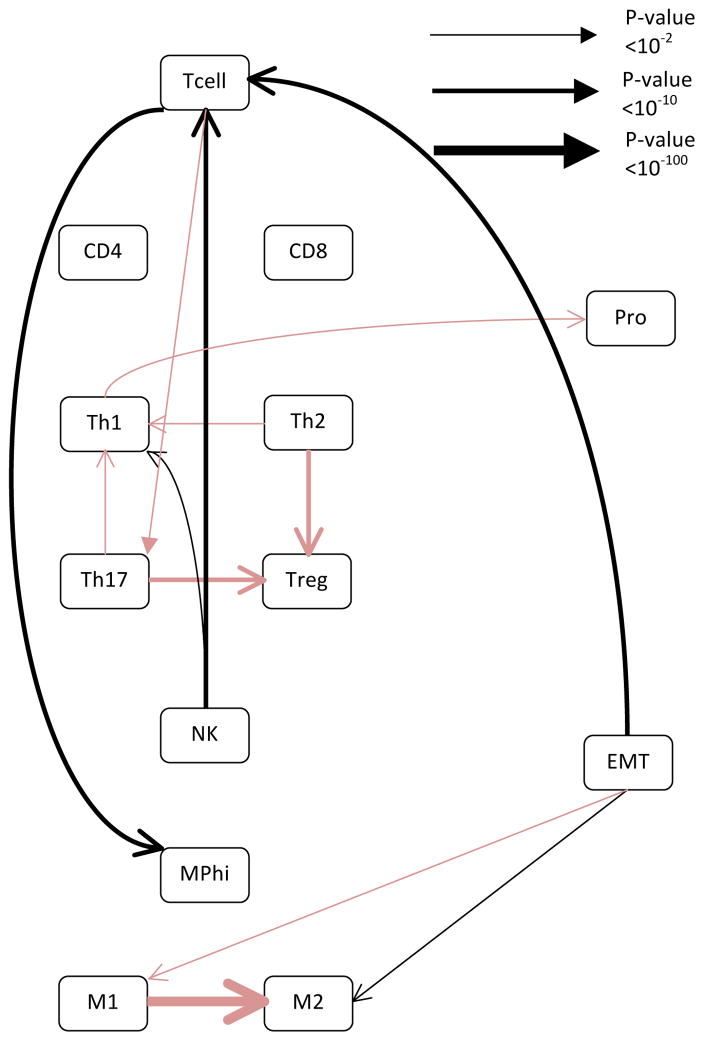

The glioblastoma multiform network is interesting as it was the most complex and contained more connection than the other cancer networks (see Fig 5 and Table S8). It contains the relationship between proliferation and macrophage polarization, but is the only network to have EMT be related to NK infiltration. However, if the network is generated using only the cancer samples, the relationship between EMT and macrophage polarization reemerged. These differences may be due to the fact that glioblastoma multiform, unlike the other cancers analyzed, arises in an immune privileged area.38

Figure 5. The network inferred from the TCGA glioblastoma multiform dataset does not closely resemble any of the breast cancer datasets.

The network was generated using the same algorithm as Figure 1. Black lines represent positive relationships while red lines represent negative relationships. The line thickness is proportional to the log of the confidence in the connection, with thicker lines representing a higher confidence. Specific p-values associated with each edge are provided in Table S4.

Discussion and Conclusion

Given that host immunity is a distributed extracellular network and is important for maintaining tissue homeostasis, we hypothesized that oncogenesis is associated with altering host immunity in similar ways despite the fact that cancers may arise in different anatomical locations. To test this, we first asked whether Bayesian inference algorithms could be used to identify changes in the extracellular regulatory network associated with host immunity that occur in conjunction with oncogenesis, namely an increase in cell proliferation and EMT. Our approach used gene expression data obtained from tumor and normal tissue samples in conjunction with defined gene signatures, called metagenes, to infer relationships among these processes via Bayesian network inference. The metagenes quantified infiltration of immune cells, immune polarization, the extent of EMT, and cell proliferation. We used data from the invasive breast cancer arm of the TCGA to generate directed acyclic graphs and used model averaging and bootstrap resampling methods to establish confidence in the network topology. Next, we asked whether these networks are similar or different in cancers that arise in different anatomical locations. As a form of external validation, we found that similar network structures were observed in other cancers in a manner consistent with the size and diversity of the underlying datasets. In summary, we have outlined a method for identifying areas of local crosstalk between different cells associated with host immunity within the tumor microenvironment using microarray data and prior knowledge of gene signatures.

Identifying the topology of networks is an important first step in understanding how the flow of information is organized within biological systems.39 In cancer, this is an important question, as oncogenesis is associated with rewiring of networks.8,9 Identifying oncogenic changes in networks can then be used to inform therapy.40,41 In cancer biology, the focus heretofore has been on identifying oncogenic changes associated with intracellular networks, which can be performed with (e.g.,42,43) or without (e.g.,44,45) prior information about the network. In contrast, identifying cellular changes in extracellular networks is aided by prior information about different cell subsets, as the presence or absence of a particular cell type within a heterogenous sample induces a distinct gene expression signature. A number of studies have focused on identifying unique gene expression sets associated with distinct cell subsets. These gene expression signatures have been used to deconvolute the cellular composition in heterogeneous samples.46 However these approaches are applied to analyze gene sets derived from relatively pure populations, such as identifying immune cell subsets within the blood. Here our objective was to example more complicated tissues, like solid tumors.

As the overall objective was to identify relationships among biological processes associated with tissue homeostasis and immune-mediated control of multicellular tissues, the inferred networks identified some interesting crosstalk among these processes. In particular, we found that an increase in proliferation tended to coincide with increases in cell-mediated immune responses that promote cancer destruction while EMT increases tended to coincide with increases in cell-mediated immune responses that either did not kill the cancer or which would help promote tumor tolerance. For example, in the breast cancer and glioblastoma multiform datasets increased proliferation led to increases in M1 polarized macrophages, while the same relationship, but in the opposite direction, was identified in the colorectal adenocarcinoma dataset. Proliferation was also found to be associated with increases in Th1 cells in colorectal and breast cancer data sets and with increases in natural killer cell infiltration in glioblastoma multiform. A type I cell-mediated immune response is generally considered to have a positive overall impact on cancer survival36, as it uses Th1 polarized CD4 T lymphocytes, CD8 T lymphocytes47 and natural killer48 cells as effector cells to help eliminate malignant cells. At the same time, increased EMT activity was associated with an increase in M2 polarization in the lung and breast cancer and appeared to be driven by decrease in natural killer cells in glioblastoma multiform. Of all the cancers analyzed, glioblastoma multiform was the most different from the other analyzed cancers, irrespective of the size and diversity of the underlying datasets. This difference could be due to the fact that these interactions occur in an immune-privileged area, with the underlying immune processes being different that what would be observed in a non-privileged area.

These networks provided a topology and directionality of the intracellular networks at work in a tumor microenvironment. However, certain aspects of the directionality remain uncertain. For instance, the directionality with regards to macrophage polarization and EMT was reversed if the analysis was performed with just the malignant samples relative to the whole breast cancer dataset. These results may reflect the possibility that the inferred networks change during cancer progression, that is progression is not a linear process. This observation also raises the question as to which network model most closely reflects what occurs within the patient. To address this question, a similar analysis of temporal data obtained from spontaneous mouse models may be informative. While the relationship between macrophage polarization and EMT had not been reported before in breast cancer, similar relationships have been observed in other forms of cancer, for instance, M2 macrophages are the most common polarization for cancer associated macrophages49 and promote EMT in vitro.50 In melanoma, tumor cells induce immune-suppression when they undergo EMT.51 Alternatively, M2 polarized macrophages have been shown to induce EMT in certain forms of pancreatic cancer.52 Also, feedback loops are a common network motif in biological systems (e.g.,3), but are necessarily removed in the directed acyclic graphs used in our analysis. This can generate overly simplistic models; for example, a positive feedback loop would be interpreted as a straight forward causal relationship.

It is also important to remember the assumptions that are used in these analyses. One of the major assumptions was that we can replicate temporal cancer progression using samples obtained from different patients diagnosed with a specific cancer and that cancer follows a single course of disease progression within a given anatomical location. The temporal aspect of the data is limited partially by the fact the tissue samples are all taken at diagnosis before treatments has begun. As such, we have included information from more advanced tumors at the primary site (see Table S9) and we have included data from tumor tissue and matched normal tissue. Due to the low number of samples from metastatic sites (n = 8, Table S9), the inferred networks focus on interactions that occur at the primary site.

Despite these limitations, these networks do give us an understanding of what relationships are occurring in human cancer progression. Moreover, the approach appears promising to help identify and verify model systems that more closely mimic human disease progression, resulting in the selection of more relevant models. For example, longitudinal studies using mouse models that mimic the metagene signatures associated with oncogenesis may help inform ambiguities in our causal networks as well as serve as a relevant model for testing new treatments. Furthermore, these models can be used to identify instances of feedback loops. As the amount of available data increases, it may become possible to identify unique networks associated with different cancer subsets. Different networks would suggest that a different regulatory mechanism has been altered during oncogenesis, which would help in selecting appropriate mechanism-based therapies to restore tissue homeostasis. Moreover this information could help in drug development to select pre-clinical models that better represent oncogenesis in these individuals.

Supplementary Material

Table S1. Gene list of metagenes.

Table S2. Directionality and confidence of invasive breast cancer network.

Table S3. Directionality and confidence of network inferred from 75% of invasive breast cancer dataset.

Table S4. Directionality and confidence of network inferred from 50% of invasive breast cancer dataset.

Table S5. Directionality and confidence of network inferred from 25% of invasive breast cancer dataset.

Table S6. Directionality and confidence of colon adenocarcinoma network.

Table S7. Directionality and confidence of lung squamous cell carcinoma network.

Table S8. Directionality and confidence of glioblastoma multiform network.

Table S9. Patient characteristics from group diagnosed with invasive breast cancer.

Fig. S1. Hierarchical clustering of breast cancer patient data separates the samples into cancer and non-cancer tissue samples.

Fig. S2. Most of the variability in the gene data can be captured by the first four principal components.

Fig. S3. Bayesian networks reveal cross-talk among polarized immune subsets and inverse relationships between the proliferation and but not the EMT metagene with regards to macrophage polarization when generated using just malignant samples.

Fig. S4. The cancer sample groups differ in their expression of the EMT metagene, proliferation metagene, and macrophage polarization.

Fig. S5. The relationship between EMT and macrophage polarization is maintained when bootstrapped subsamples are taken of only the data obtained from cancer tissue samples.

Fig. S6. Schematic diagram illustrating the analysis data flow.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Science Foundation (CAREER 1053490) and the National Cancer Institute (NCI) R15CA123123 and R01CA193473. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NCI, the National Institutes of Health, or the National Science Foundation. JLK, CLB, and DJK declare that they have no potential financial conflicts of interest.

Literature Cited

- 1.Hollstein M, Sidransky D, Vogelstein B, Harris CC. p53 mutations in human cancers. Science. 1991 Jul;253(5015):49–53. doi: 10.1126/science.1905840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vermeer PD, Einwalter LA, Moninger TO, Rokhlina T, Kern JA, Zabner J, Welsh MJ. Segregation of receptor and ligand regulates activation of epithelial growth factor receptor. Nature. 2003 Mar;422(6929):322–326. doi: 10.1038/nature01440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Klinke DJ, Horvath N, Cuppett V, Wu Y, Deng W, Kanj R. Interlocked positive and negative feedback network motifs regulate β-catenin activity in the adherens junction pathway. Mol Biol Cell. 2015 Nov;26(22):4135–4148. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E15-02-0083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klinke DJ. An evolutionary perspective on anti-tumor immunity. Front Oncology. 2012;2:202. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2012.00202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Purvis JE, Lahav G. Encoding and decoding cellular information through signaling dynamics. Cell. 2013 Feb;152(5):945–956. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zou M, Conzen SD. A new dynamic bayesian network (DBN) approach for identifying gene regulatory networks from time course microarray data. Bioinformatics. 2005 Jan;21(1):71–79. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Perrin B-E, Ralaivola L, Mazurie A, Bottani S, Mallet J, d’Alche-Buc F. Gene networks inference using dynamic bayesian networks. Bioinformatics. 2003 Sep;19(suppl 2):ii138–ii148. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pawson T, Warner N. Oncogenic re-wiring of cellular signaling pathways. Oncogene. 2007;26:1268–1275. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klinke DJ. Signal transduction networks in cancer: Quantitative parameters influence network topology. Cancer Res. 2010;70(5):1773–1782. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: The next generation. Cell. 2011 Mar;144(5):646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jia P, Pao W, Zhao Z. Patterns and processes of somatic mutations in nine major cancers. BMC Med Genomics. 2014;7:11. doi: 10.1186/1755-8794-7-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Merlo LMF, Pepper JW, Reid BJ, Maley CC. Cancer as an evolutionary and ecological process. Nature Rev Cancer. 2006 Dec;6(12):924–935. doi: 10.1038/nrc2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klinke DJ. Enhancing the discovery and development of immunotherapies for cancer using quantitative and systems pharmacology: Interleukin-12 as a case study. J Immunother Cancer. 2015;3:27. doi: 10.1186/s40425-015-0069-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Klinke DJ, Kulkarni YM, Wu Y, Byrne-Hoffman C. Inferring alterations in cell-to-cell communication in HER2+ breast cancer using secretome profiling of three cell models. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2014 Sep;111(9):1853–1863. doi: 10.1002/bit.25238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Friedman N. Inferring cellular networks using probabilistic graphical models. Science. 2004 Feb;303(5659):799–805. doi: 10.1126/science.1094068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sieberts Solveig K, Schadt Eric E. Moving toward a system genetics view of disease. Mammalian Genome. 2007 Jul;18(6–7):389–401. doi: 10.1007/s00335-007-9040-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sachs K, Gifford D, Jaakkola T, Sorger P, Lauffenburger DA. Bayesian network approach to cell signaling pathway modeling. Sci Signal. 2002 Sep;2002(148):pe38. doi: 10.1126/stke.2002.148.pe38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sachs K, Perez O, Pe’er D, Lauffenburger DA, Nolan GP. Causal protein-signaling networks derived from multiparameter single-cell data. Science. 2005 Apr;308(5721):523–529. doi: 10.1126/science.1105809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sachs K, Itani S, Carlisle J, Nolan GP, Pe’er D, Lauffenburger DA. Learning signaling network structures with sparsely distributed data. J Comp Biology. 2009 Feb;16(2):201–212. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2008.07TT. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cancer Genome Atlas Network. Comprehensive molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature. 2012 Oct;490(7418):61–70. doi: 10.1038/nature11412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bolstad BM, Irizarry RA, Östrand M, Speed TP. A comparison of normalization methods for high density oligonucleotide array data based on variance and bias. Bioinformatics. 2003 Jan;19(2):185–193. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/19.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.BioCarta. [Accessed 2015-11–15]; http://cgap.nci.nih.gov/Pathways/BioCarta_Pathways.

- 23.Plougastel B, Trowsdale J. Sequence analysis of a 62-kb region overlapping the human KLRC cluster of genes. Genomics. 1998 Apr;49(2):193–199. doi: 10.1006/geno.1997.5197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Movahedi K, Laoui D, Gysemans C, Baeten M, Stange G, Van den Bossche J, Mack M, Pipeleers D, In’t Veld P, De Baetselier P, Van Ginderachter JA. Different tumor microenvironments contain functionally distinct subsets of macrophages derived from Ly6C(high) monocytes. Cancer Res. 2010 Jul;70(14):5728–5739. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-4672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Klinke DJ. Induction of Wnt-inducible signaling protein-1 correlates with invasive breast cancer oncogenesis and reduced type 1 cell-mediated cytotoxic immunity: a retrospective study. PLoS Comput Biol. 2014 Jan;10(1):e1003409. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cheng W-Yi, Kandel JJ, Yamashiro DJ, Canoll P, Anastassiou D. A multi-cancer mesenchymal transition gene expression signature is associated with prolonged time to recurrence in glioblastoma. PLoS ONE. 2012 Apr;7(4):e34705. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Palmer NP, Schmid PR, Berger B, Kohane IS. A gene expression profile of stem cell pluripotentiality and differentiation is conserved across diverse solid and hematopoietic cancers. Genome Biology. 2012 Aug;13(8):R71. doi: 10.1186/gb-2012-13-8-r71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wei G, Wei L, Zhu J, Zang C, Hu-Li J, Yao Z, Cui K, Kanno Y, Roh T-Y, Watford WT, Schones DE, Peng W, Sun H-w, Paul WE, O’Shea JJ, Zhao K. Global mapping of H3K4me3 and H3K27me3 reveals specificity and plasticity in lineage fate determination of differentiating CD4+ t cells. Immunity. 2009 Jan;30(1):155–167. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna, Austria: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tsamardinos I, Aliferis C, Statnikov A, Statnikov E. Algorithms for large scale markov blanket discovery. The 16th International FLAIRS Conference, St; AAAI Press; 2003. pp. 376–380. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Friedman N, Goldszmidt M, Wyner A. Data analysis with bayesian networks: A bootstrap approach. Proceedings Uncertainty in Artificial Intelligence; Morgan Kaufmann Pub Inc; 1999. pp. 196–205. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bar-Joseph Z, Gitter A, Simon I. Studying and modelling dynamic biological processes using time-series gene expression data. Nature Rev Genetics. 2012 Aug;13(8):552–564. doi: 10.1038/nrg3244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ohri CM, Shikotra A, Green RH, Waller DA, Bradding P. Macrophages within NSCLC tumour islets are predominantly of a cytotoxic m1 phenotype associated with extended survival. Eur Respiratory J. 2009 Jan;33(1):118–126. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00065708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Savage NDL, de Boer T, Walburg KV, Joosten SA, van Meijgaarden K, Geluk A, Ottenhoff THM. Human anti-inflammatory macrophages induce Foxp3+GITR+CD25+ regulatory t cells, which suppress via membrane-bound TGFβ-1. J Immunology. 2008 Aug;181(3):2220–2226. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.3.2220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Heusinkveld M, van der Burg SH. Identification and manipulation of tumor associated macrophages in human cancers. J Translational Med. 2011 Dec;9(1):216. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-9-216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tosolini M, Kirilovsky A, Mlecnik B, Fredriksen T, Mauger S, Bindea G, Berger A, Bruneval P, Fridman WH, Pages F, Galon J. Clinical impact of different classes of infiltrating t cytotoxic and helper cells (Th1, Th2, Treg, Th17) in patients with colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 2011 Feb;71(4):1263–1271. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zarkoob H, Taube JH, Singh SK, Mani SA, Kohandel M. Investigating the link between molecular subtypes of glioblastoma, epithelial-mesenchymal transition, and CD133 cell surface protein. PLoS ONE. 2013 May;8(5):e64169. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weller M, Weinstock C, Will C, Wagenknecht B, Dichgans J, Lang F, Gulbins E. CD95-Dependent t-cell killing by glioma cells expressing CD95 ligand: More on tumor immune escape, the CD95 counterattack, and the immune privilege of the brain. Cellular Physiology and Biochemistry. 1997;7(5):282–288. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Barabasi AL, Oltvai ZN. Network biology: understanding the cell’s functional organization. Nat Rev Genet. 2004 Feb;5(2):101–113. doi: 10.1038/nrg1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Azmi AS, Wang Z, Philip PA, Mohammad RM, Sarkar FH. Proof of concept: network and systems biology approaches aid in the discovery of potent anticancer drug combinations. Mol Cancer Ther. 2010 Dec;9(12):3137–3144. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-10-0642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Meric-Bernstam F, Johnson A, Holla V, Bailey AM, Brusco L, Chen K, Routbort M, Patel KP, Zeng J, Kopetz S, Davies MA, Piha-Paul SA, Hong DS, Eterovic AK, Tsimberidou AM, Broaddus R, Bernstam EV, Shaw KR, Mendelsohn J, Mills GB. A decision support framework for genomically informed investigational cancer therapy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015 Jul;107(7) doi: 10.1093/jnci/djv098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vallat L, Kemper CA, Jung N, Maumy-Bertrand M, Bertrand F, Meyer N, Pocheville A, Fisher JW, Gribben JG, Bahram S. Reverse-engineering the genetic circuitry of a cancer cell with predicted intervention in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013 Jan;110(2):459–464. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1211130110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hill SM, Lu Y, Molina J, Heiser LM, Spellman PT, Speed TP, Gray JW, Mills GB, Mukherjee S. Bayesian inference of signaling network topology in a cancer cell line. Bioinformatics. 2012 Nov;28(21):2804–2810. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.AlQuraishi M, Koytiger G, Jenney A, MacBeath G, Sorger PK. A multiscale statistical mechanical framework integrates biophysical and genomic data to assemble cancer networks. Nat Genet. 2014 Dec;46(12):1363–1371. doi: 10.1038/ng.3138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen JC, Alvarez MJ, Talos F, Dhruv H, Rieckhof GE, Iyer A, Diefes KL, Aldape K, Berens M, Shen MM, Califano A. Identification of causal genetic drivers of human disease through systems-level analysis of regulatory networks. Cell. 2014 Oct;159(2):402–414. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.09.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Newman AM, Liu CL, Green MR, Gentles AJ, Feng W, Xu Y, Hoang CD, Diehn M, Alizadeh AA. Robust enumeration of cell subsets from tissue expression profiles. Nat Methods. 2015 May;12(5):453–457. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mahmoud SMA, Paish EC, Powe DG, Macmillan RD, Grainge MJ, Lee AHS, Ellis IO, Green AR. Tumor-infiltrating CD8+ lymphocytes predict clinical outcome in breast cancer. J Clinical Oncology. 2011 May;29(15):1949–1955. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.30.5037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zamai L, Ponti C, Mirandola P, Gobbi G, Papa S, Galeotti L, Cocco L, Vitale M. NK cells and cancer. J Immunology. 2007 Apr;178(7):4011–4016. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.7.4011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sica A, Schioppa T, Mantovani A, Allavena P. Tumour-associated macrophages are a distinct m2 polarised population promoting tumour progression: Potential targets of anti-cancer therapy. Eur J Cancer. 2006 Apr;42(6):717–727. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2006.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bonde A-K, Tischler V, Kumar S, Soltermann A, Schwendener RA. Intra-tumoral macrophages contribute to epithelial-mesenchymal transition in solid tumors. BMC Cancer. 2012 Jan;12:35. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-12-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kudo-Saito C, Shirako H, Takeuchi T, Kawakami Y. Cancer metastasis is accelerated through immunosuppression during snail-induced EMT of cancer cells. Cancer Cell. 2009 Mar;15(3):195–206. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ying Liu C, Xu J-Y, Shi X-Y, Huang W, Ruan T-Y, Xie P, Ding J-L. M2-polarized tumor-associated macrophages promoted epithelial-mesenchymal transition in pancreatic cancer cells, partially through TLR4/IL-10 signaling pathway. Lab Invest. 2013 Jul;93(7):844–854. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2013.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Gene list of metagenes.

Table S2. Directionality and confidence of invasive breast cancer network.

Table S3. Directionality and confidence of network inferred from 75% of invasive breast cancer dataset.

Table S4. Directionality and confidence of network inferred from 50% of invasive breast cancer dataset.

Table S5. Directionality and confidence of network inferred from 25% of invasive breast cancer dataset.

Table S6. Directionality and confidence of colon adenocarcinoma network.

Table S7. Directionality and confidence of lung squamous cell carcinoma network.

Table S8. Directionality and confidence of glioblastoma multiform network.

Table S9. Patient characteristics from group diagnosed with invasive breast cancer.

Fig. S1. Hierarchical clustering of breast cancer patient data separates the samples into cancer and non-cancer tissue samples.

Fig. S2. Most of the variability in the gene data can be captured by the first four principal components.

Fig. S3. Bayesian networks reveal cross-talk among polarized immune subsets and inverse relationships between the proliferation and but not the EMT metagene with regards to macrophage polarization when generated using just malignant samples.

Fig. S4. The cancer sample groups differ in their expression of the EMT metagene, proliferation metagene, and macrophage polarization.

Fig. S5. The relationship between EMT and macrophage polarization is maintained when bootstrapped subsamples are taken of only the data obtained from cancer tissue samples.

Fig. S6. Schematic diagram illustrating the analysis data flow.