Abstract

Cellular senescence is a fundamental mechanism by which cells remain metabolically active yet cease dividing and undergo distinct phenotypic alterations, including upregulation of p16Ink4a, profound secretome changes, telomere shortening, and decondensation of pericentromeric satellite DNA. Because senescent cells accumulate in multiple tissues with aging, these cells and the dysfunctional factors they secrete, termed the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP), are increasingly recognized as promising therapeutic targets to prevent age-related degenerative pathologies, including osteoporosis. However, the cell type(s) within the bone microenvironment that undergoes senescence with aging in vivo has remained poorly understood, largely because previous studies have focused on senescence in cultured cells. Thus in young (age 6 months) and old (age 24 months) mice, we measured senescence and SASP markers in vivo in highly enriched cell populations, all rapidly isolated from bone/marrow without in vitro culture. In both females and males, p16Ink4a expression by real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (rt-qPCR) was significantly higher with aging in B cells, T cells, myeloid cells, osteoblast progenitors, osteoblasts, and osteocytes. Further, in vivo quantification of senescence-associated distension of satellites (SADS), ie, large-scale unraveling of pericentromeric satellite DNA, revealed significantly more senescent osteocytes in old compared with young bone cortices (11% versus 2%, p < 0.001). In addition, primary osteocytes from old mice had sixfold more (p < 0.001) telomere dysfunction-induced foci (TIFs) than osteocytes from young mice. Corresponding with the age-associated accumulation of senescent osteocytes was significantly higher expression of multiple SASP markers in osteocytes from old versus young mice, several of which also showed dramatic age-associated upregulation in myeloid cells. These data show that with aging, a subset of cells of various lineages within the bone microenvironment become senescent, although senescent myeloid cells and senescent osteocytes predominantly develop the SASP. Given the critical roles of osteocytes in orchestrating bone remodeling, our findings suggest that senescent osteocytes and their SASP may contribute to age-related bone loss.

Keywords: AGING, OSTEOCYTES, CELL/TISSUE SIGNALING, ANIMAL MODELS

Introduction

Advanced age is the key risk factor for most chronic diseases,(1) contributing to enormous costs that will only worsen with our growing older population. Thus there is a critical need to develop interventions that can prevent or reverse age-related diseases as a group and thereby maximize healthy life span in humans.(2) This may be feasible by targeting a fundamental aging mechanism–cellular senescence.

Senescence is a stress response that halts the proliferation of dysfunctional cells, causing them to enter a state of irreversible growth arrest even in the presence of growth stimuli and oncogenic insults.(2–4) Senescent cells are distinct from quiescent and terminally differentiated cells in that they develop a unique phenotypic signature, characterized by profound chromatin and secretome changes typically induced by nuclear DNA damage and mitochondrial dysfunction.(5–7) Despite their dysfunctional internal environment, senescent cells remain metabolically active and have heightened survival, making them highly viable and resistant to apoptosis.(8) Senescent cells can also secrete proinflammatory cytokines, chemokines, and extracellular matrix proteins, which together create a toxic microenvironment termed the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP).(9–11) By spreading toxic factors to neighboring bystander cells, the SASP likely contributes to additional senescent cell accumulation and further tissue dysfunction.(12)

With advancing age, senescent cells accumulate in multiple tissues where they alter homeostasis and potentially promote the development of age-related degenerative diseases.(2–4) Thus, even though senescent cell abundance with aging is relatively low (eg, achieving a maximum of 15% of nucleated cells in very old primates(13)), senescent cells and their SASP are increasingly recognized as promising therapeutic targets to prevent age-related diseases as a group.(2) The causal link between senescence and age-related tissue dysfunction has been shown in genetically modified progeroid mice, and more recently in normal chronologically aged mice expressing a “suicide” transgene, INK-ATTAC, which permits inducible elimination of senescent cells upon administration of a drug (AP20187).(14,15) Despite clearing only approximately 30% of senescent cells, this approach significantly enhanced both life span and health span by delaying the onset of aging pathologies in multiple tissues, including adipose, eye, heart, kidney, and muscle.(14,15) Moreover, periodic administration of “senolytics”, small molecules that selectively ablate senescent cells, has been shown to extend health span in progeroid mice by delaying age-related symptoms of frailty and pathology, including osteoporosis.(16)

To date, in vivo age-related senescence effects in bone are poorly understood, although the adverse effects of senescence that cause dysfunction in other tissues(2–4) appear to also occur in bone where they may contribute to impaired osteoblast progenitor cell function, defective bone formation, and increased osteoclastogenesis.(17–19) However, the mechanisms by which senescent cells and the SASP potentially alter bone remodeling are incompletely understood, leaving a significant gap in knowledge. In addition, the cell type(s) within the bone microenvironment that undergo senescence with aging in vivo have remained elusive, largely because previous studies have predominantly focused on senescence in cultured cells.

Chronic senescence is a gradual response to the age-related accumulation of cellular and molecular damage, including telomere erosion, decondensation of pericentromeric satellite DNA, increased reactive oxygen species (ROS), DNA damage, and both epigenetic and proteotoxic stress.(2–5) Although a universal or exclusive marker expressed only in senescent cells has not been identified, most chronic senescent cells express the cell cycle inhibitor p16Ink4a, a principal effector of senescence,(2–4) which increases with age in several rodent and human tissues.(20–22) Other probable effectors of chronic senescence include p21 and p53, which are induced with aging in some tissues under certain types of stress.(23,24) In addition, chronic senescent cells are characterized by persistent DNA damage, a greater number of telomere dysfunction-induced foci (TIFs), and striking decondensation of pericentromeric satellite heterochromatin termed senescence-associated distension of satellites (SADS).(4,5) Given that targeted elimination of senescent cells and/or inhibition of their detrimental effects may represent a viable approach to prevent bone loss, we sought to identify the cell type(s) within the bone microenvironment that undergo senescence with aging in vivo, as well as those that develop the SASP.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Six months of age (young) and 24 months of age (old) C57BL/6 wild-type (WT) female and male mice were obtained from the National Institute on Aging (NIA). Mice were housed in ventilated cages within an accredited facility under a 12-hour light/dark cycle with constant temperature (23°C), and had access to water and food ad libitum. All animal protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) before study initiation, and all experiments were performed in accordance with IACUC guidelines.

Tissue collection and bone marrow isolation

Mice were euthanized in the morning and tissues immediately dissected for further phenotyping. Muscle and connective tissues were removed from harvested vertebrae, femurs, tibias, and humeri. Vertebrae were used for isolation of osteoblast-enriched cells and one of the osteocyte-enriched populations (see below). The proximal and distal metaphyses of the femurs, tibias, and humeri were cut and the bone marrow was flushed from the diaphyses with FACS buffer. The flushed long-bone diaphyses were further subjected to serial collagenase digestion to obtain a cortical osteocyte-enriched population that was immediately homogenized (Tissue Tearor; Cole Parmer, Court Vernon Hills, IL, USA) in lysis buffer (QIAzol; Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) and subsequently stored at −80°C for later extraction of RNA, as detailed below. Flushed bone marrow cells were pooled and treated with 1 × red blood cell (RBC) lysis buffer solution (eBioscience, San Diego, CA, USA) for 5 min at room temperature. Following a brief centrifugation and resuspension in FACS buffer, the resulting bone marrow mononuclear cells (BMMNCs) were further processed, as described below, using magnetic-activated cell sorting (MACS, autoMACS-Pro magnetic cell sorter; Miltenyi Biotec, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) to obtain highly enriched fractions of osteoblast progenitors, myeloid cells, B cells, and T cells (all without in vitro culture).

Isolation of osteoblast progenitors

The hematopoietic lineage negative (Lin−) population, an enriched osteoblast progenitor fraction,(25) was isolated using MACS as previously discussed.(26) Following RBC lysis, BMMNCs were magnetically labeled with a mouse lineage cell depletion kit (Miltenyi Biotec GmbH, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany) containing antibodies to CD5, CD45R (B220), CD11b, Gr-1 (Ly-6G/C), 7–4, and Ter-119 for depletion of mature hematopoietic cells, monocytes/macrophages, granulocytes, erythrocytes, and their committed precursors. After a single wash, Lin− cells were sorted using MACS and then magnetically labeled with a goat-anti-Leptin receptor (Lepr)-biotin antibody (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA). MACS were then used to isolate the Lin−/Lepr+ population because the Morrison laboratory(27) recently showed that this population contains virtually all of the bone marrow–derived osteoblast progenitors and that these cells are responsible for bone formation in adult life.

Isolation of osteoblast- and osteocyte-enriched cells

For isolation of the osteoblast- and osteocyte-enriched cells, vertebrae were stripped of muscle and connective tissues and minced into small pieces. The osteoblast isolation protocol involved two sequential 30-min collagenase digests (Liberase; Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany) followed by MACS to deplete hematopoietic/endothelial cells (by removal of CD31-, CD34-, CD45-, and CD54-expressing cells; Miltenyi Biotec GmbH). Then a second MACS step was performed to enrich for alkaline phosphatase (AP; R&D Systems)-expressing cells. These methods provide highly enriched populations of osteoblasts (AP+/CD31/34/45/54 cells) and osteocytes (collagenase-digested vertebrae or diaphyses) within approximately 2 to 3 hours, as summarized in Supplementary Fig. 1 and previously shown by our group for osteoblasts(28) and for osteocytes by the Bonewald laboratory.(29) The same collagenase protocol used for the vertebrae was used to obtain osteocyte-enriched cells from the long-bone diaphyses.

Isolation of myeloid cells, B cells, and T cells

Analogous MACS-based approaches were used for isolating highly enriched populations of myeloid cells, B cells, and T cells from bone marrow. Following RBC lysis, BMMNCs were incubated with CD14-biotin antibody. Antibiotin microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec, Inc.) were added per the manufacturer’s instructions and the CD14+ (myeloid-enriched) population was isolated using MACS. The remaining CD14− fraction was split in half for isolations of B cells and T cells, respectively. To isolate B cells, the first CD14− fraction was depleted for T-cell (CD3ε) and neutrophil (CD15) markers using biotin-labeled antibodies and MACS (as described above), followed by incubation of the CD14−/CD3ε−/CD15− fraction with CD19 antibody to isolate the CD19+ (B-cell–enriched) population. By contrast, to isolate T cells, the other CD14− fraction was depleted for B-cell (CD19) and neutrophil (CD15) markers and the CD14−/CD19−/CD15− cells were incubated with CD3ε antibody to isolate the CD3ε+ (T-cell–enriched) population. All cell sorts were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions and all antibodies were purchased from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA, USA). These methods provided highly enriched populations of myeloid cells, B cells, and T cells (without in vitro culture), as summarized in Supplementary Fig. 2.

Validation of bone microenvironment cell sorting techniques

As noted earlier, the Morrison laboratory recently showed that bone marrow Lin−/Lepr+ cells are the main source of bone formed by bone marrow–derived osteoblast progenitors.(27) Consistent with the observation that Lin− cells mineralize in vitro and form bone in vivo,(25) Lepr expression was significantly enriched (2.7-fold) in Lin− cells as compared with Lin+ cells. Furthermore, following MACS to isolate the Lin−/Lepr+ cells, we found that Lepr expression levels were 8.7-fold higher in the Lin−/Lepr+ cells as compared with the Lin−/Lepr− cells, and that the Lin−/Lepr+ population represented approximately 0.34% of BMMNCs, which agrees well with the Morrison group.(27)

Our osteoblast and osteocyte isolation protocols have previously been described(28,29); for further validation, we first showed that cells from the first (30 min) collagenase digest failed to mineralize (Alizarin Red staining), but that the second (30 min) digest cells exhibited robust mineralization (Supplementary Fig. 3A), showing that the osteoblast population resides in the second digest fraction. Following hematopoietic/endothelial cell depletion and enrichment for alkaline phosphatase (AP)-expressing cells by MACS, we showed that the resulting cell population (AP+/CD31/34/45/54−) was both highly enriched for osteoblast markers (Supplementary Fig. 3B) and greatly depleted for CD31/34/45/54 hematopoietic markers (Supplementary Fig. 3C) versus the second digest cells. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 3D, the remaining osteocyte-enriched cells expressed high levels of osteocyte markers, whereas the AP+/CD31/34/45/54− osteoblast-enriched cells expressed very low levels of these markers, showing that AP+/CD31/34/45/54− cells do not include osteocytes. We further performed Western blotting analysis (Supplementary Fig. 3E) for AP protein, showing much higher AP expression in the AP+/CD31/34/45/54− cells as compared with either the Lin−/Lepr+ cells or the osteocyte-enriched cells. Finally, in each respective hematopoietic lineage-enriched cell population (myeloid cells, B cells, and T cells), we showed enrichment for key CD markers: myeloid cells (CD14, Supplementary Fig. 3F), B cells (CD19, Supplementary Fig. 3G), and T cells (CD3ε, Supplementary Fig. 3H). Although acknowledging that none of the isolated bone microenvironment cell populations are entirely pure, for purposes of reporting we refer to the enriched-cell populations as: B cells, T cells, myeloid cells, osteoblast progenitors, osteoblasts, and osteocytes, respectively. The cell yields for each of these populations are summarized in Supplementary Tables 1A–B for females and males, separately.

Analysis of senescent osteocytes in vivo

Recent work has shown that pericentromeric satellite heterochromatin undergoes decondensation in cell senescence, and that this large-scale unraveling of pericentromeric satellite DNA, termed SADS, is a robust marker of cell senescence in vivo.(5) Detailed procedures for the SADS assay are described in the Supplementary Methods.

Isolation of primary osteocytes for culture

Comprehensive approaches for the isolation of primary osteocytes for culture are discussed in the Supplementary Methods.

Telomere dysfunction-induced foci assay

Detailed processes for the TIF assay are explained in the Supplementary Methods.

Real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction

Detailed methods for the rt-qPCR analyses are described in the Supplementary Methods. Supplementary Tables 2A and 2B provide all of the primer sequences used in this study.

Western blotting analyses

Particulars for the Western blotting analyses are provided in the Supplementary Methods.

Obtaining and processing human needle biopsies of bone

As described previously,(30) we obtained small needle bone biopsies from the posterior iliac crest of young (mean age ± SD, 27 ± 3 years; range 23 to 30 years) and old (78±5 years; range 72 to 87 years) healthy female volunteers using an 8G needle under local anesthesia (1% lidocaine) and monitored intravenous sedation. All protocols were approved by Mayo Clinic’s Institutional Review Board (IRB), and informed written consent was obtained from all subjects. Detailed methods for obtaining and processing the human bone biopsies appear in the Supplementary Methods.

Statistical analysis

All comparisons were performed using the two-sample t test (or rank sum test, as appropriate). A p value < 0.05 was considered significant. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad software (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) (www.graphpad.com). Gene expression data were also analyzed using Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA)(31,32) (http://software.broadinstitute.org/gsea/index.jsp) to assess if changes in gene expression occurred in a predefined cluster of 36 established SASP genes.(9–11) Heat maps were created using GSEA software.

Results

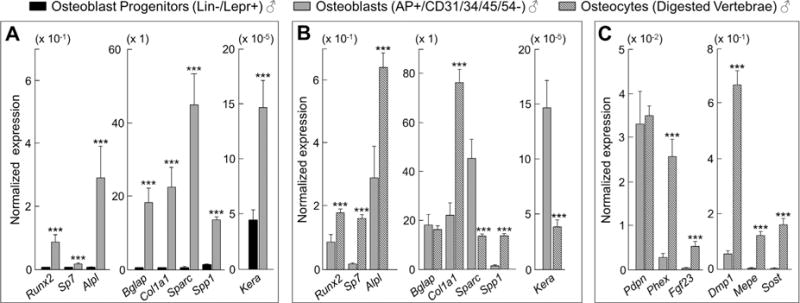

To further validate our MACS-based approach for rapidly isolating highly enriched populations of osteoblast progenitors, osteoblasts, and osteocytes without in vitro culture (as described in Materials and Methods), we performed rt-qPCR analyses in each of these populations. Our data show that expression levels of the key osteoblast lineage markers (ie, Run×2, Sp7, Alpl, Bglap, Col1a1, Kera, Sparc, Spp1) were all significantly (p < 0.001) higher in osteoblasts versus osteoblast progenitors (Fig. 1A). We also compared osteoblast markers in the osteoblasts versus osteocytes (Fig. 1B) and although keratocan expression was, consistent with previous work,(33) significantly higher in the osteoblasts (p < 0.001; Fig. 1B), several osteoblast-related mRNAs (eg, Alpl, Col1a1) were expressed at higher levels in the osteocyte-enriched cells as compared with the osteoblasts; this is similar to recent findings from Nioi et al.(34) who used laser-capture dissection to isolate osteoblasts and osteocytes from rat bones and found similar (or somewhat higher) expression of Col1a1 in osteocytes as compared with osteoblasts. Of note, at least for Alpl, Western blotting analysis (Supplementary Fig. 3E) showed that despite the higher Alpl mRNA levels in osteocytes, AP protein expression was 6.1-fold higher in osteoblasts. As such, it is possible that some osteoblast-related mRNAs are transcribed at higher levels in osteocytes, but this does not result in increased protein expression. Finally, as expected, expression levels of several of the key osteocyte markers (ie, Dmp1, Phex, Mepe, Sost, Fgf23) were significantly (p < 0.001) elevated in osteocytes versus osteoblasts (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1.

Comparisons of key osteoblast lineage markers among osteoblast progenitors, osteoblasts, and osteocytes. (A) The normalized mRNA expression of osteoblast genes is significantly higher in osteoblasts (AP+/CD31/34/45/54− cells) as compared with osteoblast progenitors (Lin−/Lepr+ cells). (B) Comparisons of normalized mRNA expression between osteoblasts (AP+/CD31/34/45/54− cells) and osteocytes (digested vertebrae). (C) The normalized mRNA expression of osteocyte genes is significantly higher in osteocytes (digested vertebrae) as compared with osteoblasts (AP+/CD31/34/45/54− cells). All three cell populations were derived from young (age 6 months) male mice (n = 12). Data are presented as mean ± SE. ***p < 0.001.

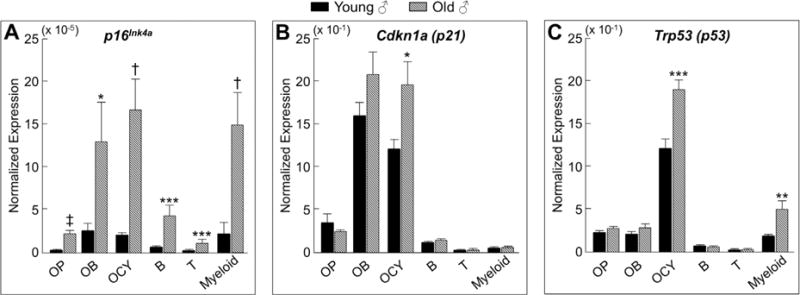

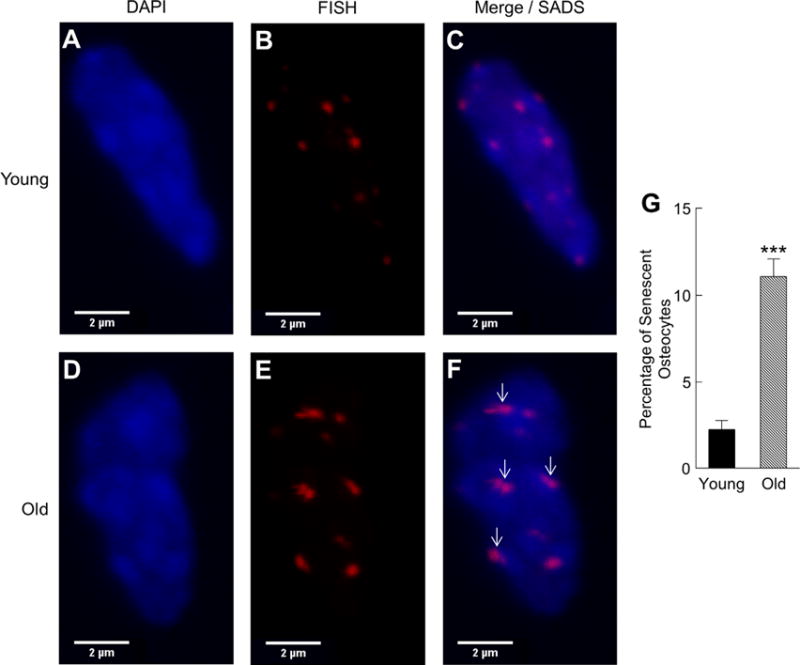

Next, in young (age 6 months) and old (age 24 months) mice, we measured the expression of chronic senescence effectors (p16Ink4a, p21, and p53) in vivo by rt-qPCR in each of the isolated cell populations. In males, p16Ink4a expression (Fig. 2A) was markedly higher with aging in osteoblast progenitors (5.4-fold, p < 0.00001), osteoblasts (4.8-fold, p < 0.05), osteocytes (9.9-fold, p < 0.0001), B cells (6.7-fold, p < 0.001), T cells (5.3-fold, p < 0.001), and myeloid cells (6.1-fold, p < 0.0001). In addition, p21 expression was significantly higher in osteocytes (Fig. 2B), and p53 expression was significantly higher in osteocytes and myeloid cells (Fig. 2C) in old versus young male mice. Importantly, virtually identical findings were observed for p16Ink4a expression in the same respective bone microenvironment cell populations obtained from young versus old female mice (Supplementary Fig. 4A–C). Furthermore, p16Ink4a expression was also higher in the digested long-bone diaphyses from old mice (19.0-fold, p < 0.00001), as was p21 (p < 0.05), and p53 (p < 0.001) expression (Supplementary Fig. 5A–C). Taken together, these data indicate that the senescence biomarker, p16Ink4a, is expressed at higher levels with aging in a variety of bone microenvironment cell types rapidly isolated from both males and females, including osteocyte populations from both trabecular and cortical skeletal sites. To further validate these findings, we measured SADS in vivo and found significantly more senescent osteocytes in old as compared to young bone cortices (11% versus 2%, p < 0.001; Fig. 3A–G).

Fig. 2.

Cells in the bone microenvironment from old mice express higher levels of the senescence biomarker p16Ink4a. In vivo age-associated changes in normalized mRNA expression of senescence effectors (A) p16Ink4a, (B) p21, and (C) p53 are shown for OP (osteoblast progenitors; Lin−/Lepr+ cells), OB (osteoblasts; AP+/CD31/34/45/54− cells), OCY (osteocytes; digested vertebrae), B (B cells; CD19+/CD14/15/3ε− cells), T (T cells; CD3ε+/CD14/15/19− cells), and myeloid (myeloid cells; CD14+ cells), all rapidly isolated from young (age 6 months; n = 12) and old (age 24 months; n = 10) male mice (without in vitro culture). Data are presented as mean ± SE. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; †p < 0.0001; ‡p < 0.00001.

Fig. 3.

A subset of osteocytes from old mice display marked distension of pericentromeric satellite DNA in vivo. Senescence-associated distension of satellites (SADS, see arrows [in F]) in osteocytes from young (age 6 months; A–C) versus old (age 24 months; D–F) male cortical bone diaphyses (n = 4 per group; magnification ×100). (G) Quantification of the percentage of senescent osteocytes in young versus old male mice based on a cut-off of ≥4 SADS per cell (see Supplementary Methods for determination of this cut-off). ***p < 0.001.

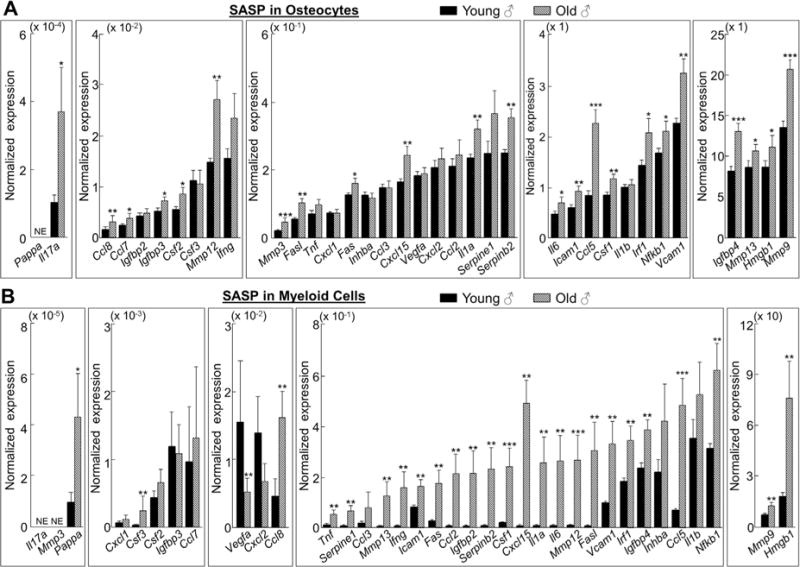

To determine which of the bone microenvironment cell types develop the SASP, we used rt-qPCR to measure the expression of a panel of 36 established SASP genes(9–11) in each of the respective male cell populations. We found that relatively few SASP factors were altered significantly with aging in osteoblast progenitors and osteoblasts (Supplementary Fig. 6A, B, GSEA p values > 0.05, respectively). In contrast, corresponding with the age-associated accumulation of senescent osteocytes were significantly higher levels of 23 of the 36 SASP genes analyzed in old versus young osteocytes (Fig. 4A [upper panels], GSEA p value < 0.001). We next analyzed the same panel of SASP genes in the hematopoietic linage cell populations and found relatively few significant changes in the expression of these genes with aging in B cells and T cells (Supplementary Fig. 7, GSEA p values > 0.05, respectively). However, several of the same SASP factors that were higher with age in osteocytes were also significantly (p < 0.05) upregulated in old as compared to young myeloid cells (26 of the 36 genes analyzed; Fig. 4B [lower panels], GSEA p value < 0.001). Heat maps are shown summarizing the age-associated fold changes of the SASP factors analyzed in osteocytes (Supplementary Fig. 8A) and myeloid cells (Supplementary Fig. 8B).

Fig. 4.

Osteocytes and myeloid cells from old chronologically aged mice develop the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP). (A) Osteocytes and (B) myeloid cells were rapidly isolated from young (age 6 months; n = 12) and old (age 24 months; n = 10) male mice (without in vitro culture). In vivo age-associated changes in normalized mRNA expression of 36 established SASP components are shown. Results are expressed as mean ± SE. NE = not expressed (Cycle threshold [Ct] values >35 in both young and old samples). *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

Because recent studies have demonstrated that autophagy plays a critical role in the prevention of DNA damage and cell senescence,(35,36) we also measured the expression of Atg7 and Map1lc3a (commonly known as LC3), two well-established markers of autophagy,(37,38) by rt-qPCR in each of the male cell populations isolated from the bone microenvironment. With aging, Atg7 (Supplementary Fig. 9A) and LC3 (Supplementary Fig. 9B) levels did not change in B cells, T cells, osteoblast progenitors, and osteoblasts. By contrast, levels of both Atg7 and LC3 were significantly lower in both myeloid cells and osteocytes from old versus young mice (Supplementary Fig. 9A, B).

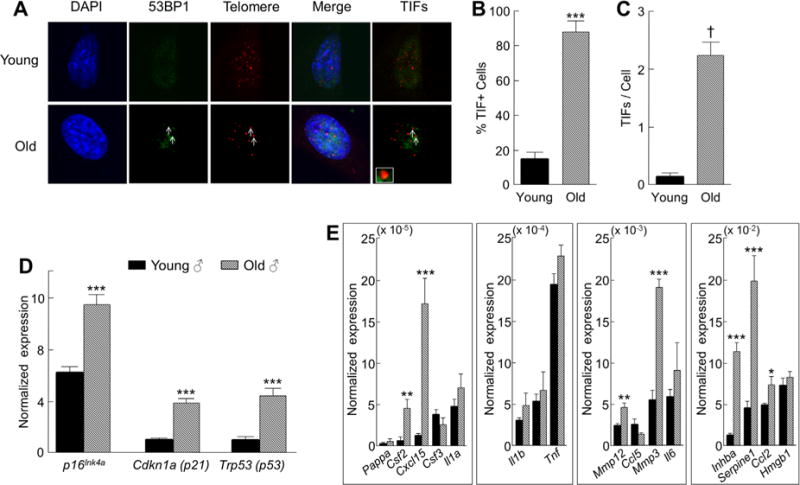

To establish whether our in vivo findings of higher senescence and SASP markers in osteocytes from old mice extend to primary osteocytes when put into culture, we isolated and cultured primary osteocytes from young (age 6 months) and old (age 24 months) male mice (n = 3 per group) using methods developed by the Bonewald laboratory.(39) We first evaluated primary osteocytes for the presence of TIFs, another marker of cell senescence associated with telomere dysfunction resulting from impaired DNA damage repair mechanisms.(40) This revealed that primary osteocytes from old mice had markedly higher TIFs, ie, sixfold (p < 0.001) more than those observed in primary osteocytes from young mice (Fig. 5A, B). Indeed, on average, primary osteocytes from old mice had more than two TIFs per cell (mean ± SE, 2.23 ± 0.25), compared with only 0.15 (±0.06) TIFs per cell in primary osteocytes from young mice (Fig. 5C; p < 0.0001). In addition, similar to the in vivo findings, cultured primary osteocytes from old mice expressed much higher levels of p16Ink4a, p21, and p53 (Fig. 5D) as well as multiple SASP markers (Fig. 5E). Taken together with our in vivo gene expression and confocal microscopy results, these data show that at least a subset of osteocytes clearly become senescent with aging and maintain their senescent phenotype when put into culture.

Fig. 5.

Primary osteocytes from old chronologically aged mice have dysfunctional telomeres and maintain their senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) when put into culture. (A) Telomere dysfunction-induced foci (TIFs), co-localization of 53BP1 (a DNA damage protein), and telomeric DNA are shown for primary osteocytes (arrows) from old (age 24 months) male mice; inset shows magnification of representative TIF (magnification× 630). (B) Percentage of TIF+ cells and (C) TIFs per cell in primary cultured osteocytes from old (age 24 months; n = 3) versus young (age 4 months; n = 3) male mice. In vivo age-associated changes in normalized mRNA expression of (D) senescence effectors and (E) SASP factors in male primary osteocytes after 7 days in culture. Data are presented as mean ± SE. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; †p < 0.0001.

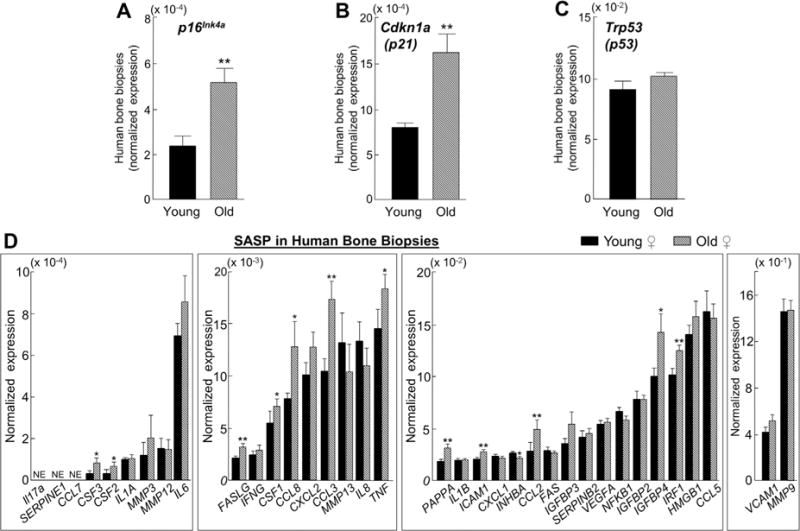

To determine whether our findings in mice extend to humans, we obtained needle biopsies of bone from young and old healthy female volunteers and measured the in vivo expression of chronic senescence effectors and SASP markers by rt-qPCR. Consistent with our data in mice, p16Ink4a expression was significantly higher (2.2-fold, p < 0.01; Fig. 6A) in the bone biopsies from the old versus young women, as was the expression of p21 (1.5-fold, p < 0.01; Fig. 6B) but not p53 (Fig. 6C). We next analyzed the same panel of 36 established SASP factors described above, which as a group tended to be higher in the bone biopsies from the old women, although this change did not reach statistical significance (GSEA p value = 0.219). Nevertheless, despite the heterogeneous nature of the bone biopsies that contain multiple cell populations including both bone and marrow elements, we found that 12 SASP factors were significantly (p < 0.05) higher in the bone biopsies from old compared with young subjects (Fig. 6D), although given the lack of statistical significance by GSEA, these findings should be considered preliminary and thus need further confirmation.

Fig. 6.

Expression levels of senescence effectors and senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) markers are higher with aging in human bone biopsies. Small needle bone biopsies were obtained from the posterior iliac crest of 10 young (mean ± SD; 27 ± 3 years) and 10 old (mean ± SD; 78 ± 6 years) healthy female volunteers and the normalized expression of (A–C) senescence and (D) SASP genes was measured in vivo using rt-qPCR. Data are presented as mean ± SE. NE = not expressed (Cycle threshold [Ct] values >35 in both young and old samples). *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01.

Discussion

The degenerative pathologies of aging are at least partly linked by the fundamental biological mechanism of cellular senescence.(2–4) Although senescent cell abundance in tissues is relatively low, even in advanced age,(13) these cells can have profound negative effects on tissue function through their SASP, which is widely recognized as the probable link between senescence and age-related tissue dysfunction.(2–4) Thus the notion that eliminating senescent cells and/or blunting their SASP could prevent or delay age-related diseases as a group, rather than treating each condition separately, has considerable potential as a novel clinical therapy. The feasibility of this concept is supported by recent studies in mice showing that selective elimination of senescent cells using both transgenic(14,15) and pharmacological(16) approaches extends health span by delaying age-related symptoms of frailty and pathology, including osteoporosis. However, the mechanisms by which senescent cells and the SASP alter bone remodeling remain unclear, thus leaving a significant gap in knowledge.

To begin to establish the role of senescence in age-related bone loss, we first asked: Which cell type(s) in the bone microenvironment become senescent in vivo with normal chronological aging? Here we present novel methods to rapidly isolate highly enriched populations of B cells, T cells, myeloid cells, osteoblast progenitors, osteoblasts, and osteocytes directly from mouse bones/marrow of young (age 6 months) and old (age 24 months) mice without the need for an intermediate cell culture step that can significantly alter gene expression. These approaches represent important technical advances because they utilize freshly isolated cells, in contrast to studies using cells following extensive in vitro manipulation. We then coupled these techniques to analytical tools for measuring expression of senescence and SASP markers in vivo via rt-qPCR in each of the freshly isolated cell populations. Our data, in mice and in humans, indicate that with normal chronological aging, a variety of bone microenvironment cell types become senescent; although based on our findings in mice, senescent myeloid cells and senescent osteocytes appear to be the main sources of the SASP in the bone marrow and in bone itself. In addition, we found that osteocytes from old mice have satellite distension as well as dysfunctional telomeres that are hallmarks of age-related chronic senescence.(2–5) Further, according to our in vivo SADS data, approximately 11% of osteocytes in old mice were senescent, which is consistent with the proportion of senescent fibroblasts (reaching a maximum of approximately 15%) found in the skin of very old primates.(13)

Because senescence involves the loss of proliferation capacity, it was thought for many years that this phenomenon only occurred in mitotic (ie, proliferation-competent) cells. However, mounting evidence has challenged this presumption. Because most mammalian cells are postmitotic, there is great interest in establishing whether nondividing cells, like mitotic cells, can become senescent with aging. Recent studies have shown that neurons,(41) hepatocytes,(42) and adipocytes(43) can exhibit several key senescence properties, including elevated levels of p16Ink4a and high senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SA-β-gal) activity, along with increased DNA damage and telomere dysfunction. These findings are consistent with our data showing that osteocytes can become senescent with normal chronological aging, and also produce a strong SASP signal that potentially has negative effects on neighboring bystander cells in the bone microenvironment.

Given the critical role of osteocytes in regulating bone remodeling,(44) targeted elimination of dysfunctional senescent osteocytes could potentially reverse the SASP, enhance bone formation, and prevent age-related bone loss. Interestingly, as noted earlier, even though senescent cell abundance in tissues with aging is relatively low, clearance of only 30% of senescent cells using the INK-ATTAC transgenic mouse model described previously had a profound effect on preventing tissue dysfunction and the onset of multiple age-related pathologies.(14,15) Moreover, because osteocytes are long-lived cells that constitute more than 95% of all bone cells,(44) they represent a logical and attractive therapeutic target. Therefore, eliminating or reducing the burden of a relatively small proportion of senescent osteocytes could represent a viable therapeutic approach to prevent age-related bone loss.

Our data point to senescent myeloid lineage cells and senescent osteocytes as the main sources of the age-related SASP in the bone microenvironment. The SASP has been shown to be initiated by NF-κB(45) and maintained in an autocrine loop, at least in part, by IL-1α.(12) Interestingly, we found that the expression levels of both NF-κB and IL-1α were elevated with aging in myeloid cells and osteocytes. Furthermore, we found that expression levels of several additional major SASP components,(9–11) including IL-6 (Il6), IL-8 (Cxcl15), MCP-1 (Ccl2), RANTES (Ccl5), M-CSF (Csf1), GM-CSF (Csf2), G-CSF (Csf3), HMG-1 (Hmgb1), PAI-1 (Serpine1), PAI-2 (Serpinb2), TNFα (Tnf), and multiple matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), were significantly elevated in myeloid cells and osteocytes with aging.

Given the accumulating evidence showing osteocyte control of myeloid lineage cells (eg, osteocyte RANKL production leading to osteoclast development from myeloid progenitors(46,47)), it is tempting to speculate that with aging, a subset of osteocytes become senescent and produce a SASP signal that is communicated to neighboring myeloid lineage cells. These myeloid lineage cells may, in turn, become senescent and amplify this signal, resulting in excessive production and secretion of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines, thereby creating a toxic local microenvironment that may not only lead to senescence of neighboring cells (eg, B cells, T cells, osteoblast progenitors, and osteoblasts), but also contribute to age-related bone loss. Future studies are needed to test this hypothesis.

We also found in chronologically aged mice that key markers of autophagy (Atg7 and LC3), the lysosomal-mediated process for degradation of damaged organelles and long-lived proteins, were lower in both myeloid cells and osteocytes from old versus young mice. These observations are intriguing given that genetic deletion of Atg7 in osteocytes, using the dentin matrix protein 1 (DMP1)-cyclic recombinase (Cre) transgenic mouse,(48) results in low bone remodeling and a phenotype that mimics skeletal aging.(49) Thus, because impaired autophagy has been shown to induce senescence in nonskeletal tissues,(35,36) it will be particularly relevant for future research to establish whether approaches that restore autophagy are effective in preventing or reversing the age-related accumulation of senescent cells in bone. Moreover, in contrast to our findings in myeloid cells and osteocytes from old mice, we found no age-related differences in autophagy markers in cell populations that produced comparatively weak SASP signals, suggesting that impaired autophagy may play a role in activation of the SASP program in senescent cells, although additional studies are needed to test this possibility.

As noted earlier, we acknowledge that the cell populations we isolated were not entirely pure, but rather highly enriched for each of the respective bone microenvironment cell populations as shown by our cell sorting validation data. Further, we acknowledge that the age-related increases we observed in SASP factors could be caused in part by other nonsenescent cells because not all age-related inflammation comes from senescent cells. In addition, we did not use LC3-based assays or other approaches for monitoring autophagy in vivo.

Finally, it should be noted that in this study we did not establish causality between senescence and bone loss or use tools to eliminate senescent cells to test the effects of senescence (direct or indirect) on bone remodeling. More work is needed to establish whether senescence plays a causal role in age-related bone loss. However, given the causal role of senescent cells in the development of age-related pathologies in nonskeletal tissues,(14,15) in combination with our data, it seems reasonable to hypothesize that accumulation of senescent cells in the bone microenvironment, particularly those cells that develop the SASP, is one potential mechanism driving age-related bone loss. This hypothesis is supported by data in progeroid mice from our group, which was the first to provide evidence that periodic administration of senolytic drugs, which selectively ablate senescent cells, delays age-related bone loss.(16) Nevertheless, because progeroid syndromes do not completely recapitulate the complex pathological changes of aging, our findings need to be confirmed in normal chronologically aged animals.

In summary, by using novel techniques to rapidly isolate highly enriched populations of bone- and hematopoieticlineage cells from mouse bones/marrow and studying these cell populations without in vitro culture, our study demonstrates that with normal chronological aging, a variety of cell types within the bone microenvironment become senescent, and that senescent myeloid cells and senescent osteocytes are predominantly responsible for developing the SASP. Given the critical role of osteocytes in orchestrating bone remodeling, our findings further suggest that senescent osteocytes and their SASP may contribute to age-related bone loss and that eliminating senescent osteocytes represents an attractive therapeutic approach to prevent or delay osteoporosis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH Grants P01 AG004875 and AG048792 (SK), UL1 TR000135 (Mayo Center for Clinical and Translational Science), P01 AG039355 (LFB), R01 AG028873 (RJP) from the National Institute on Aging, and both a high-risk pilot award (JNF, SK) and a career development award (JNF) from the Mayo Clinic Robert and Arlene Kogod Center on Aging. MBO was funded by a training grant from Newcastle University Institute for Ageing. We thank Ms. Jennifer Onken and Ms. Brittany Negley for technical assistance and data collection, as well as James Peterson for assistance with data analysis.

Authors’ roles: Study concept and design: JNF, RJP, and SK. Provision of study materials: KJ and LFB. Data collection: JNF, HW, and RJP. Data analysis: JNF, HW, MBO, LFB, and RJP. Data interpretation: JNF, HW, MBO, LFB, RJP, and SK. Experiments conducted: JNF, DGF, HW, and DGM. First draft of manuscript: JNF. Manuscript writing: LFB, RJP, and SK. Revised manuscript content: MTD and DGM. Approved final version of manuscript: All authors.

Footnotes

Disclosures

All authors state that they have no conflicts of interest.

For a Commentary on this article, please see Sims (J Bone Miner Res. 2016;31(11):1917–1919. DOI: 10.1002/jbmr.2994).

Additional Supplementary Information may be found in the online version of this article.

References

- 1.Goldman DP, Cutler D, Rowe JW, et al. Substantial health and economic returns from delayed aging may warrant a new focus for medical research. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013;32(10):1698–1705. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tchkonia T, Zhu Y, Van Deuersen J, Campisi J, Kirkland JL. Cellular senescence and the senescent secretory phenotype: therapeutic opportunities. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:966–72. doi: 10.1172/JCI64098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van Deursen JM. The role of senescent cells in ageing. Nature. 2014;509:439–46. doi: 10.1038/nature13193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Childs BG, Durik M, Baker DJ, van Deursen JM. Cellular senescence in aging and age-related disease: from mechanisms to therapy. Nat Med. 2015;21(12):1424–35. doi: 10.1038/nm.4000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Swanson EC, Manning B, Zhang H, Lawrence JB. Higher-order unfolding of satellite heterochromatin is a consistent and early event in cell senescence. J Cell Biol. 2013;203(6):929–42. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201306073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.von Zglinicki T, Saretzki G, Ladhoff J, d’Adda di Fagagna F, Jackson SP. Human cell senescence as a DNA damage response. Mech Ageing Dev. 2005;126(1):111–17. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2004.09.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ziegler DV, Wiley CD, Velarde MC. Mitochondrial effectors of cellular senescence: beyond the free radical theory of aging. Aging Cell. 2015;14(1):1–7. doi: 10.1111/acel.12287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang E. Senescent human fibroblasts resist programmed cell death, and failure to suppress bcl2 is involved. Cancer Res. 1995;55(11):2284–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coppé JP, Patil CK, Rodier F, et al. Senescence-associated secretory phenotypes reveal cell-nonautonomous functions of oncogenic RAS and the p53 tumor suppressor. PLoS Biol. 2008;6(12):2853–68. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Acosta JC, Banito A, Wuestefeld T, et al. A complex secretory program orchestrated by the inflammasomes controls paracrine senescence. Nat Cell Biol. 2013;15(8):978–90. doi: 10.1038/ncb2784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coppé JP, Desprez PY, Krtolica A, Campisi J. The senescence-associated secretory phenotype: the dark side of tumor suppression. Annu Rev Pathol. 2010;5:99–118. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-121808-102144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nelson G, Wordsworth J, Wang C, et al. A senescent cell bystander effect: senescence-induced senescence. Aging Cell. 2012;11(2):345–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2012.00795.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Herbig U, Ferreira M, Condel L, Carey D, Sedivy JM. Cellular senescence in aging primates. Science. 2006;311:1257. doi: 10.1126/science.1122446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baker DJ, Wijshake T, Tchkonia T, et al. Clearance of p16Ink4a-positive senescent cells delay aging-associated disorders. Nature. 2011;479(7372):232–36. doi: 10.1038/nature10600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baker DJ, Childs BG, Durik M, et al. Naturally occurring p16Ink4a-positive cells shorten healthy lifespan. Nature. 2016 Feb 11;530(7589):184–9. doi: 10.1038/nature16932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhu Y, Tchkonia T, Pirtskhalava T, et al. The Achilles’ heel of senescent cells: from transcriptome to senolytic drugs. Aging Cell. 2015;14(4):644–58. doi: 10.1111/acel.12344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kassem M, Marie PJ. Senescence-associated intrinsic mechanisms of osteoblast dysfunctions. Aging Cell. 2011;10(2):191–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2011.00669.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marie PJ. Bone cell senescence: mechanisms and perspectives. J Bone Miner Res. 2014;29(6):1311–21. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen Q, Liu K, Robinson AR, et al. DNA damage drives accelerated bone aging via an NF-kB-dependent mechanism. J Bone Miner Res. 2013;28:1214–28. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krishnamurthy J, Torrice C, Ramsey MR, et al. Ink4a/Arf expression is a biomarker of aging. J Clin Invest. 2004;114(9):1299–1307. doi: 10.1172/JCI22475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Burd CE, Sorrentino JA, Clark KS, et al. Monitoring tumorigenesis and senescence in vivo with a p16(INK4a) luciferase model. Cell. 2013;152(1–2):340–51. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Waaijer ME, Parish WE, Strongitharm BH, et al. The number of p16INK4a positive cells in human skin reflects biological age. Aging Cell. 2012;11(4):722–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2012.00837.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beauséjour CM, Krtolica A, Galimi F, et al. Reversal of human cellular senescence: roles of the p53 and p16 pathways. EMBO J. 2003;22(16):4212–22. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baker DJ, Weaver RL, van Deursen JM. p21 both attenuates and drives senescence and aging in BubR1 progeroid mice. Cell Rep. 2013;3(4):1164–74. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.03.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Itoh S, Aubin JE. A novel purification method for multipotential skeletal stem cells. J Cell Biochem. 2009;108:368–77. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Syed FA, Modder UI, Roforth M, et al. Effects of chronic estrogen treatment on modulating age-related bone loss in female mice. J Bone Miner Res. 2010;25(11):2438–46. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhou BO, Yue R, Murphy MM, Peyer JG, Morrison SJ. Leptin-receptor-expressing mesenchymal stromal cells represent the main source of bone formed by adult bone marrow. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;15:154–68. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fujita K, Roforth MM, Atkinson EJ, et al. Isolation and characterization of human osteoblasts from needle biopsies without in vitro culture. Osteoporos Int. 2014;25:887–95. doi: 10.1007/s00198-013-2529-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Qing H, Ardeshirpour L, Pajevic PD, et al. Demonstration of osteocytic perilacunar/canalicular remodeling in mice during lactation. J Bone Miner Res. 2012;27(5):1018–29. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Farr JN, Roforth MM, Fujita K, et al. Effects of age and estrogen on skeletal gene expression in humans as assessed by RNA sequencing. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0138347. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0138347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Subramanian A, Tamayo P, Mootha VK, et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide experssion profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(43):15545–50. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506580102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Efron B, Tibshirani R. On testing the significance of sets of genes. Ann Appl Statist. 2007;1(1):107–29. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Paic F, Igwe JC, Nori R, et al. Identification of differentially expressed genes between osteoblasts and osteocytes. Bone. 2009;45(4):682–92. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2009.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nioi P, Taylor S, Hu R, et al. Transcriptional profiling of laser capture microdissected subpopulations of the osteoblast lineage provides insight into the early response to sclerostin antibody in rats. J Bone Miner Res. 2015;30(8):1457–67. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kang C, Xu Q, Martin TD, et al. The DNA damage response induces inflammation and senescence by inhibiting autophagy of GATA4. Science. 2015;349(6255):aaa5612. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa5612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Garcia-Prat L, Martinez-Vicente M, Perdiguero E, et al. Autophagy maintains stemness by preventing senescence. Nature. 2016;529(7584):37–42. doi: 10.1038/nature16187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Komatsu M, Waguri S, Ueno T, et al. Impairment of starvation-induced and constitutive autophagy in Atg7-deficient mice. J Cell Biol. 2005;169(3):425–34. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200412022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kabeya Y, Mizushima N, Ueno T, et al. LC3, a mammalian homologue of yeast Apg8p, is localized in autophagosome membranes after processing. EMBO J. 2000;19(21):5720–28. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.21.5720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stern AR, Stern MM, Van Dyke ME, Jahn K, Prideaux M, Bonewald LF. Isolation and culture of primary osteocytes from the long bones of skeletally mature and aged mice. Biotechniques. 2012;52(6):361–73. doi: 10.2144/0000113876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kenyon J, Gerson SL. The role of DNA damage repair in aging of adult stem cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35(22):7557–65. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm1064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jurk D, Wang C, Miwa S, et al. Postmitotic neurons develop a p21-dependent senescence-like phenotype driven by a DNA damage response. Aging Cell. 2012;11(6):996–1004. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2012.00870.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jurk D, Wilson C, Passos JF, et al. Chronic inflammation induces telomere dysfunction and accelerates ageing in mice. Nat Commun. 2014;2:4172. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Minamino T, Orimo M, Shimizu I, et al. A crucial role for adipose tissue p53 in the regulation of insulin resistance. Nat Med. 2009;15(9):1082–87. doi: 10.1038/nm.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dallas SL, Prideaux M, Bonewald LF. The osteocyte: an endocrine cell… and more. Endocr Rev. 2013;34:658–90. doi: 10.1210/er.2012-1026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Salminen A, Kauppinen A, Kaarniranta K. Emerging role of NF-kappaB signaling in the induction of senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) Cell Signal. 2012;24(4):835–45. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2011.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nakashima T, Hayashi M, Fukunaga T, et al. Evidence for osteocyte regulation of bone homeostasis through RANKL expression. Nat Med. 2011;17(10):1231–34. doi: 10.1038/nm.2452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Xiong J, Onal M, Jilka RL, Weinstein RS, Manolagas SC, O’Brien CA. Matrix-embedded cells control osteoclast formation. Nat Med. 2011;17(10):1235–41. doi: 10.1038/nm.2448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lu Y, Xie Y, Zhang S, Dusevich V, Bonewald LF, Feng JQ. DMP1-targeted Cre expression in odontoblasts and osteocytes. J Dent Res. 2007;86(4):320–25. doi: 10.1177/154405910708600404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Onal M, Piemontese M, Xiong J, et al. Suppression of autophagy in osteocytes mimics skeletal aging. J Biol Chem. 2013;288(24):17432–40. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.444190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.