Abstract

Objective. Identify behaviors that can compose a measure of organizational citizenship by pharmacy faculty.

Methods. A four-round, modified Delphi procedure using open-ended questions (Round 1) was conducted with 13 panelists from pharmacy academia. The items generated were evaluated and refined for inclusion in subsequent rounds. A consensus was reached after completing four rounds.

Results. The panel produced a set of 26 items indicative of extra-role behaviors by faculty colleagues considered to compose a measure of citizenship, which is an expressed manifestation of collegiality.

Conclusions. The items generated require testing for validation and reliability in a large sample to create a measure of organizational citizenship. Even prior to doing so, the list of items can serve as a resource for mentorship of junior and senior faculty alike.

Keywords: organizational citizenship, citizenship behaviors, organizational culture, organizational climate

INTRODUCTION

In recent years, academia has seen a renewed focus in the literature on organizational citizenship behaviors, particularly within institutions of higher learning. Organ originally defined the term organizational citizenship behavior (OCB) as “individual behavior that is discretionary, not directly or explicitly recognized by the formal reward system, and that in the aggregate promotes the effective functioning of the organization.”1(p4) Prior to this formal definition, Katz described what he called innovative and spontaneous behaviors by employees in an organization.2 Since most employees know the major requirements and primary benchmarks for performance of their job, spontaneous, or extra-role behaviors were described as “actions not specified by role prescriptions which nevertheless facilitate the accomplishment of organizational goals.”2(p132) He further argued that “an organization which depends solely upon its blueprints of prescribed behavior is a very fragile social system.”2

The degree to which employees see their behavior as either in-role or extra-role may vary considerably across persons and situations.3 Organ refined his original definition of OCB to reflect this, later defining OCBs as “contributions to the maintenance and enhancement of the social and psychological context that supports task performance.”4(p91) The revised definition by Organ was a move towards a similar construct of contextual performance, or “those contributions that sustain an ethos of cooperation and interpersonal supportiveness of the group,” in which the definition does not specify just extra-role or non-rewarded behaviors.5(p31) As such, the definition of OCBs should include tasks other than routine functions of the job that contribute in some way to the effective organizational functioning and recognize discretion, variance, and volition in employee behavior.5

Empirical evidence suggests that OCBs may facilitate organizational performance.6-9 Bolino and colleagues proffered a theoretical framework supporting this link.10 Specifically, they suggested a framework in which OCBs lead to greater social capital for employees, which in turn enhances organizational performance.10 The relationship between organizational investments in social capital and employee organizational citizenship has been studied in employees from several different industries.11 Organizational investments in social capital have a positive relationship with OCB.11 Further, OCBs directed at individuals are positively associated with social support.12 These relationships support Organ’s redefinition which emphasized the social and psychological context of OCBs.4

Citizenship behaviors not only enhance organizational effectiveness, but also facilitate greater reward recommendations from managers.6,7,13-19 Elements of OCB have been implicated on both performance output (quantity) and quality by individuals in an organization.6 In addition, employees’ demonstration of OCBs also may enhance their manager’s (in academia, the chair’s) personal productivity, success, and evaluation of others.7

Organizational citizenship behaviors have a positive impact on managerial evaluations of performance and might be as important as in-role behaviors in this regard.13-15 This relationship has been found to be mediated by how much the manager likes the employee and by the manager’s perception of the employee’s affective commitment.19 To that end, OCBs may impact managerial evaluations and resultant reward allocation decision recommendations.15,18 The affinity a manager has for an employee has been found to mediate the relationship between OCBs and reward recommendations.19

Organ proposed 5 factors of OCB: altruism (ie, behaviors affecting a specific person in a work-related task), conscientiousness (ie, behaviors that go way beyond the role requirements), sportsmanship (ie, ability to tolerate less than ideal circumstances without complaining), civic virtue (ie, behaviors that indicate an employee participates, is involved, or is concerned about the organization), and courtesy (ie, behavior aimed at preventing problems from occurring).1 Although many researchers have cited Organ’s conceptual definition of OCB, there does not appear to be consensus on one single means of measuring OCB or on its operational definition. Smith and colleagues were probably the first to develop a scale for OCB.20 They identified 2 domains from a factor analytic procedure: altruism behaviors directed at individuals and generalized compliance behaviors that contribute in a more general fashion.20 Podsakoff and colleagues developed a 5-factor OCB scale more closely reflecting the dimensions proffered by Organ.21

Graham derived a measure of OCB comprised of 4 dimensions: interpersonal helping, individual initiative, personal industry, and loyal boosterism.22 Additionally, Moorman and Blakely developed a measure that included items from the 5 dimensions proffered by Organ with Graham’s 4-dimension measure.23 Van Dyne and colleagues reconceptualized OCB based on a political philosophy framework, suggesting that citizenship is multidimensional and is made up of obedience, loyalty, and participation behaviors.24 Williams and Anderson suggested that categories of OCB be based on the target of the citizenship behavior: those that benefit the organization (organizational citizenship behavior of organizations or OCBOs) and others that benefit other individuals (organizational citizenship behavior of individuals or OCBIs).25 Meta-analytic findings support the idea that OCBOs are distinguishable from OCBIs.15 A considerable amount of research also has reflected the idea that OCBs are directed toward different groups.15,25-31

Because of the organization-specific nature of OCBs, several researchers have developed their own instruments to measure citizenship behaviors in environments such as unions,32,33 schools,29,34-37 and universities.28,30 The Organizational Citizenship Behavior in School Scale, which was adapted from Smith and colleagues, supported a single dimension factor.35 This is reflective of Lepine and colleagues, who argued against the need to investigate different dimensions of OCB.38

Research on OCB initially was conducted by organizational behaviorists. It was examined primarily in nonautonomous jobs where the difference between in-role and extra-role performance was very distinct.39 Since then, OCB research has expanded to several other fields, such as the military and healthcare service industry.39 As the information age promotes the era of knowledge workers whose jobs are becoming more autonomous in nature,40 the distinction between in-role and extra-role citizenship behaviors may be more blurred.39

Faculty positions in postsecondary education are typically autonomous by nature. Although there has been a measure devised to study OCBs for teachers in secondary education,34 the role of a teacher in these settings differs from that of most faculty members in postsecondary education. In academia, certain objective criteria are listed for tenure and promotion; however, “routine” in-role performance is less objective. Deckop and colleagues were among the first to study OCBs in a postsecondary education setting.30 In studying OCBs, they adapted a measure by Smith and colleagues.30 They found that 3 main factors emerged: OCB-teaching, OCB-faculty, and OCB-university; however, their study was conducted in a unionized environment, which may have considerable impact on citizenship antecedents and outcomes.30

Latham and Skarlicki developed an instrument to measure OCBs among faculty members using a critical incident approach, from which 2 dimensions similar to those of Williams and Anderson emerged: behaviors directed toward the university and behaviors directed at individuals inside the organization.28 Nearly 2 decades have passed since Latham and Skarlicki developed their OCB measure, and since that time, academia has changed considerably. Among the changes is increased pressure from internal and external stakeholders for greater accountability even in the face of shrinking budgets, in addition to the continued proliferation of academic specialization, resulting in changes in department and reporting structures.41

Additionally, the measure employed by Latham and Skarlicki was developed using a critical incident approach, which may inherently limit the composing universe of items and domains in the measure; and finally, their measure was created from and used for assessing faculty members from basic fields of study.28 Professional programs such as medicine, law, and pharmacy are multidisciplinary in nature, with departmental and divisional lines often drawn across relatively disparate fields with divergent views on the preparation of students and benchmarks for scholarly productivity, but which must be reconciled for the purposes of program accreditation. As such, the need to examine the antecedents and ramifications of citizenship behaviors is especially salient. The study of OCBs in such an environment requires the creation of an appropriate measure as a key first step. The objectives of this study were to describe the unique components of the perceptions of OCBs by faculty members at colleges and schools of pharmacy and to inform the creation of a measure for OCBs in a health profession academic environment.

METHODS

The institutional review board of Touro University California reviewed and approved the study as being under exempt status from full review. A four-iteration (four round) Delphi procedure was conducted in 2010 and 2011 to induct items potentially comprising a measure of pharmacy faculty member’s perceived OCBs. A Delphi technique is a systematic procedure for arriving at a reasoned consensus.42 It elicits opinions from a group with the aim of generating a consensus response.43 The Delphi procedure has three primary features: anonymity, iteration, and controlled feedback, and provides a statistical group response.44 There have been numerous applications of the Delphi technique, with one of the main uses concerning the formation of items to compose measures used in subsequent studies.45-47 The Delphi was chosen over other face-to-face techniques (eg, a focus group) to minimize the bias of dominating individuals, group think, and irrelevant communications.44 Delphi procedures tend to yield more accurate group estimates because of the controlled, anonymous feedback they acquire.44 Moreover, a Delphi procedure is efficient for gathering the opinions of experts in disparate locations.

The success of any Delphi procedure hinges upon the characteristics of its composite panel members. Panel members should be willing and able to take part in an iterative process and have the potential to submit valuable contributions to the process.48 Purposive sampling often is used to gather an appropriate sample of persons with diversity in certain characteristics, such as gender, age, experience, rank, etc. As such, their representativeness does not imply such in a statistical sense, but rather, “the inclusion of a range of relevant interests and perspectives.”48(p175) A common method of choosing panel “experts” is typically from a pool of candidates from an informal network of possibilities.48 Typically, a Delphi panel is composed of eight to 12 members.49 While Delphi procedures have been conducted with a higher number of panel members, this is not typical, and it is important not to confuse the Delphi method with a conventional quantitative survey.49

The authors of the study created a list of possible faculty candidates. Candidates were identified not necessarily because of specific expertise in OCBs, but due to their track record of leadership in academic pharmacy, publication of papers related to faculty quality of work life, and/or holding positions or titles indicative of interest in or concern with academic governance. Potential candidates were chosen in a manner which ensured representation of public and private, as well as research-intensive and teaching-intensive, institutions. They also were selected to include representation from the basic, clinical, and social/administrative sciences of pharmacy. Academic rank was a consideration, as the researchers invited assistant, associate, full professors, as well as a limited number of faculty members in administrative roles, such as deans and department chairs.

All identified participants (n=22) were sent a letter of invitation via email. The email explained the Delphi procedure and asked for consent to participate. After receiving consent (n=13), an email with the attached questionnaire was distributed to participants. The round 1 questionnaire included 6 open-ended questions asking participants about various aspects of OCBs. The round 1 questionnaire and directions as well as subsequent rounds can be found in Appendices 1-3. The participants were provided a brief definition of the organizational citizenship construct based on Organ’s definition4; however, the investigators believed that the round 1 questionnaire should be devoid to the extent possible of any information that could be leading. To that end, the participants were provided with a relatively “blank slate.”

The responses from round 1 were reviewed for clarity and redundancy, reordered, and tabulated.50 This list of items served as the basis for the second round questionnaire. Participants were asked to rate each of the items on a Likert-type scale of importance ranging from 1 to 4 (1=not important at all, 2=slightly important, 3=important, 4=extremely important) for its potential contribution to a measure, or appropriate component of OCBs in pharmacy faculty members. We emphasized to participants not to evaluate the items based on what they had experienced or exhibited personally, but instead on the importance of that item toward contribution of organizational citizenship behavior in general.

Round 3 consisted of a slightly altered list of the items from round 2. Items were excluded from further consideration in the study if their responses from round 2 were below a median of 2.5.50 Aggregate quartile ranges and individualized responses from round 2 were also included in the round 3 questionnaire. Respondents were asked to review their responses in light of the aggregate results from their peers. Those respondents who chose to remain outside the quartile range were asked to provide an explanation. Round 4, which only included the additional items added to round 3, was conducted with the same structure as round 3.

After observing and calculating responses in rounds 3 and 4, we concluded that little variation in responses among participants remained, thus evidencing the formation of a consensus opinion and obviating subsequent rounds.49

RESULTS

The 13 Delphi participants consisted of five assistant professors, three associate professors, and five full professors. Four were from the basic pharmaceutical sciences (eg, medicinal chemistry, pharmacology, pharmaceutics), six represented the clinical practice sciences, and three were from the social and administrative pharmaceutical sciences (eg, pharmacy management, pharmacy law, pharmaceutical economics). Eight participants were from public institutions and five were from private universities. Usable responses were obtained from 12 faculty members, resulting in a 92.3% response rate for round 1. One basic sciences associate professor from a public institution failed to return the round 1 survey and discontinued participation in the project. The responses from round 1 culminated in the generation of 30 items (Table 1). Some of the participants made unique contributions, while the majority of participants provided answers that were similar. The task for the researchers then was to eliminate redundancy and refine answers from round 1 into putative items to be judged in round 2. Appendix 4 provides several direct responses from round 1, which ultimately informed subsequent rounds.

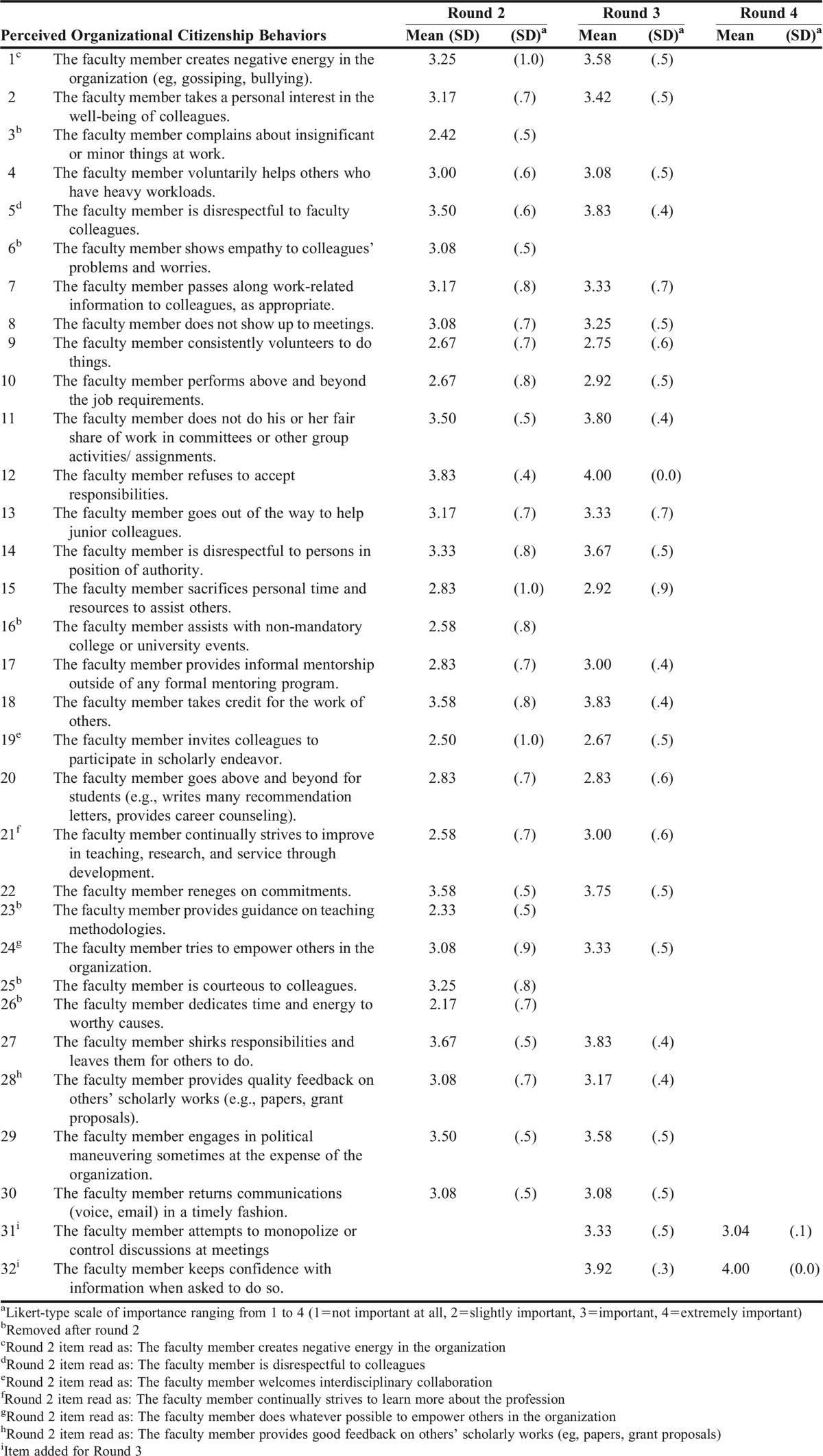

Table 1.

Participant Responses to Items in Rounds 2, 3, and 4 of a Delphi Procedure

Based on comments and suggestions from the participants in round 2, six items were omitted from the round 3 questionnaire, two items were added, and five items were modified. Four of the 6 items removed failed to meet an a priori criterion with a median importance rating of at least 2.5. The remaining two items (items 6 and 25) were removed because of participants’ comments regarding the strong similarity between them. Another item more appropriately worded and in accordance with participant feedback was substituted for these two items. Based upon additional feedback, item 31, “The faculty member attempts to monopolize or control discussion at meetings,” and item 32, “The faculty member keeps confidence with information when asked to do so,” were added to the round 3 questionnaire.

Five of the items from round 2 were modified in respect to participants’ comments. Item 1, “The faculty member creates negative energy in the organization,” was modified by incorporating the additional explanation of gossiping and bullying. Item 5, “The faculty member is disrespectful to colleagues, was made more specific by including faculty as an adjective. Item 19 was altered based on feedback that “interdisciplinary” may have been too specific, and “scholarly endeavor” would be more appropriate to incorporate all types of research, especially collaborations within the college or school of pharmacy itself. Item 21 was modified to be more inclusive of the academic triad rather than just the pharmacy profession itself. Finally, item 28 was altered to include other scholarly work, such as grant proposals, rather than only manuscripts.

Mean ratings for 19 items from round 2 were higher than 3.0, and mean ratings were equal to or exceeded 3.5 on seven of the items (Table 1). Panel experts rated all of the 26 items from round 3 with at least a mean of 2.7. Mean ratings of 21 items were higher than 3.0, and mean ratings were equal to or exceeded 3.5 on 10 of the items. Mean ratings of only 5 of the items remained below 3.0.

The results from round 3 evidenced formation of a consensus (n=12 respondents), or convergence of opinion, as the participants changed a number of their ratings to be in agreement with their peers. The standard deviation narrowed on all other items, further evidencing opinion convergence.49 Round 4 (n=11 respondents) was used only for evaluation of items generated in the middle of the process, and likewise, evidence of consensus was prevalent. All retained items had a final standard deviation of less than or equal to 0.9; 13 items had a standard deviation of less than 0.5. The final 26 OCB items are found in Table 2.

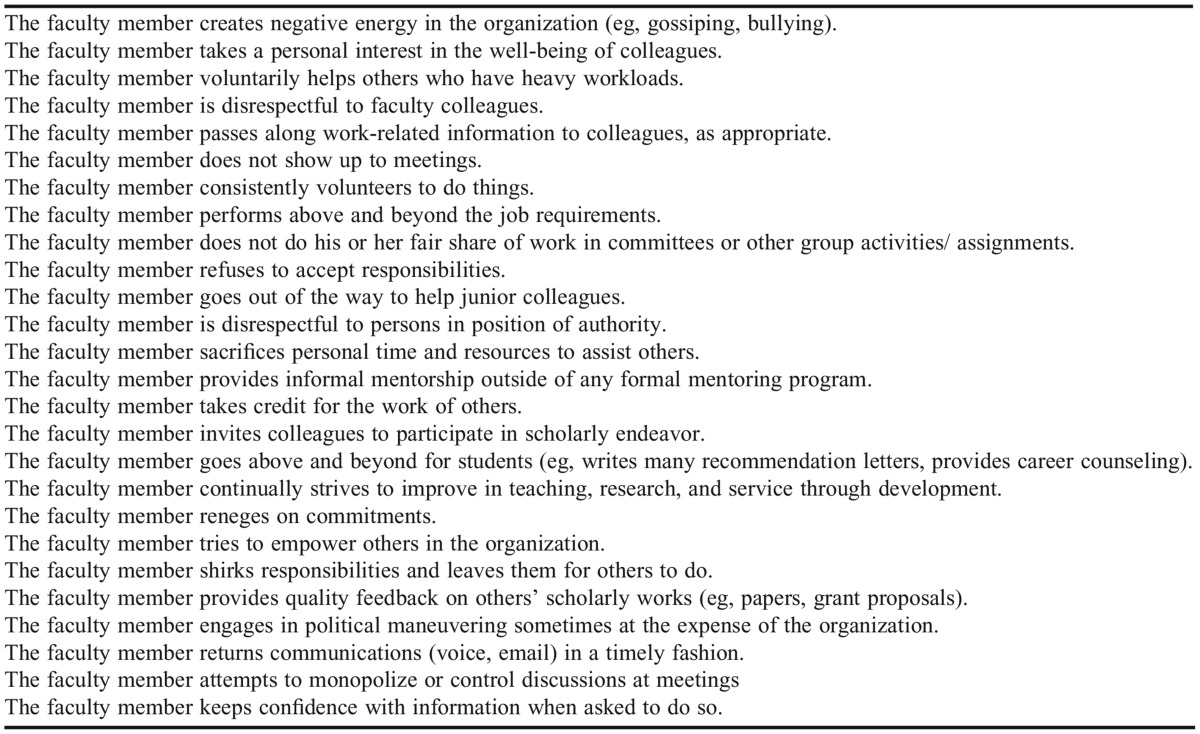

Table 2.

Final Set of Organizational Citizenship Behavior Items Included in Round 4 of a Delphi Procedure

DISCUSSION

The Delphi procedure produced a list of 26 items that can comprise a measure of OCBs of pharmacy faculty members, and potentially can be adapted for use among faculty members in different fields of study, pending appropriate validity and reliability testing. While created specifically within academic pharmacy, the items generated can be compared with the dimensions of conscientiousness, altruism, courtesy, sportsmanship, and civic virtue proposed by Organ.1 For example, “The faculty member returns communications (voice, email) in a timely fashion,” might fit in a conscientiousness domain. Further, “The faculty member takes a personal interest in the well-being of colleagues,” could be said to fall within the auspices of altruism. An item potentially belonging to a courtesy domain would be, “The faculty member passes along work-related information to colleagues, as appropriate.” Finally, “The faculty member engages in political maneuvering sometimes at the expense of the organization (reverse scored),” could be seen as a negative component of civic virtue.

The results of this study also attest to dimensions of OCBs proposed by Williams and Anderson; that is, the inclusion of behaviors directed to other individuals in the organization versus those directed at the organization itself. For example, “The faculty member shows empathy to colleagues’ problems and worries,” exemplifies behaviors directed at an individual; whereas, “The faculty member consistently volunteers to do things,” describes a behavior directed toward the benefit of the organization. Similarly, Skarlicki and Latham, in training union members on organizational justice principles found that the training increased employees’ perceptions of their leaders’ and their peers’ behavior.33 Organizational justice was found to partially mediate the effect of behavioral training on behaviors directed toward the organization but not fellow members. In other words, the benefits of such training had a direct, unmediated effect on perceptions of citizenship. This begs whether such training, adapted for more autonomous workers as those in this study, could significantly impact perceptions toward peer citizenship behaviors and those behaviors that more directly affect the organization as a whole. Moreover, Oplatka laid the foundation for such training in an academic environment, even though it was for faculty members of secondary schools rather than faculty members in a university.34 Therefore, the framework for creating an environment of citizenship behaviors through a collegial atmosphere does exist.

As such, OCBs can be said to be a manifestation of collegiality and thus of a collegial atmostphere.51 Collegiality is critical because it has been associated with faculty effectiveness.52,53 It is especially important for the productivity and success of new faculty members.54 As collegiality depends on the mutual respect and the interrelationships among colleagues, achieving any sort of collegial harmony is even more challenging under strains such as a scarcity of human resources.55 Pharmacy academia has been facing a faculty shortage for quite some time, even though vacancies and/or lost positions have recently decreased. Lack of collegiality has been cited as one of the most frequent reasons for faculty members leaving an institution.56 An American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy (AACP) task force on pharmacy faculty workplace issues suggested that colleges and schools of pharmacy inspire collegiality among faculty and staff members.57 Collegial leadership, trust, and achievement have been found to promote OCBs.58 If, as it has been suggested, citizenship can create social capital,10 then citizenship behaviors by faculty members also may promote a collegial environment, although this relationship requires further study.

One study found that collegial cultures facilitate higher trust and solidarity among colleagues in academia.59 Collegial cultures are deemed paramount for quality of work life and productivity; thus, it has been argued that collegial acts be “psychologically required.”60 Doing so facilitates a positive and reciprocal relationship between employees and the organization, which in turn creates an image of the organization to external stakeholders as one treating its internal clients well and thus likely to manifest in similar positive outcomes in dealing with external clients, be they students, customers, or future job-seekers.61 Ross and colleagues spoke at least indirectly to this issue when opining toward preparation of faculty members and students to be citizen leaders and advocates in pharmacy.62 While the crux of their thesis focused on advocating for pharmacy, they more than intimated that doing so effectively required careful examination of internal culture and collegial behaviors as ones to role model inwardly and outwardly. Likewise, the collegiality and consensus behaviors are viewed as inextricable in establishing strategic priorities and even success in a culture of scholarship.63,64

While improving OCBs may be beneficial for productivity and efficiency in any organization,6,7,15-17 the proliferation of such behaviors might be particularly important to the success of new faculty members.54 New faculty members find challenges in coping with work-related stress, allocating their time between teaching, research, professional development, and other areas of service, job expectations and navigating the faculty review process. A collegial atmosphere and mentoring can have a profound impact.54 The aforementioned AACP task force emphasized the importance for colleges and schools of pharmacy to incorporate effective mentoring programs to help retain junior faculty members.57 Mentors are critically important for the success of junior faculty members in academia58 and in conducting research.61 Positive mentoring relationships enhance the level of OCBs by the mentee.65,66 Mentors model OCBs by being good mentors.61 By its very nature, informal mentoring (not compensated and not formally mandated) can be conceptualized as a form of citizenship.61 The presence of such citizenship behaviors and a culture promoting them has been advocated in pharmacy academia for junior faculty members in evaluating potential positions.67 This type of culture likewise helps to maintain engagement for and enliven the intellectual arena for more senior faculty members.68

As such, the proliferation, or culture of OCBs may be helpful to new and junior faculty members with promotion, tenure, and other organizational rewards. In other fields, OCBs have been shown to affect managerial evaluations and reward recommendations, even though such a direct relationship has yet to be tested in the academic environment.13-15,18,19 Additionally, while tenure and promotion criteria are accompanied by benchmarks noted in an academic organization’s policies and procedures, the recommendations of the department chair and dean are critical. The department chair’s annual evaluations also are important for keeping junior faculty members on track for advancement. Based on results from previous studies,6,11,12,55,69 it might be suggested that the performance of OCBs by a faculty member may have an influence on a department chair’s evaluation of that faculty member. Overall, creating a culture with positive citizenship and a collegial, positive work environment should help faculty members be productive and successful in their academic careers.55,70

The OCBs generated from these procedures might describe behaviors found in most jobs; however, some are items that specifically reflect academic autonomy and the tripartite mission of scholarship, teaching, and service. Indeed, “The faculty member creates negative energy in the organization (reverse scored),” is an item that could describe many workplaces. Whereas one item, “The faculty member continually strives to improve teaching, research, and service through development,” drives home the importance of all three components of the academic triad. There are other items pertaining specifically to teaching; others reflect scholarship specifically; and others evidence the importance of service. Academic institutions, or even departments, can use the citizenship items not only to gauge perceptions of collegiality, but also to benchmark desired extra-role behaviors that presumably shape the entire ethos of a college or department and may affect faculty quality of work life, perceived support, and productivity.

The results of any Delphi procedure are limited by the expertise of the panel participants and the level of diligence with which they carried out the process. For example, judging by comments to the investigators and responses to open-ended questions, the Delphi participants in the study seemed to approach this responsibility with diligence; however, the possibility that, in latter rounds, some participants conformed their ratings on certain items to those of their peers for the sake of convenience rather than earnest beliefs cannot be ruled out. No matter how expert, a different set of participants may have generated a slightly different set of items. A purposive sampling strategy was employed to gain representation from the basic, clinical, and social/administrative pharmaceutical sciences, in addition to representation by type of institution, faculty rank, and participation in administrative activities.

Use of a focus group rather than a Delphi procedure might have resulted in the opinions important to disciplines with lesser representation or from junior faculty members being diminished due to groupthink, intimidation, or other limitations inherent to focus group methodology.71 In spite of its limitations, the Delphi procedure incorporates inherent strengths in its design, including mitigation of groupthink and, potentially, arrival at a consensus from knowledgeable experts highly engaged in the process. The investigators provided participants with a cursory definition of organizational citizenship behaviors based upon Organ’s conceptual framework.4 A more detailed explanation could have been provided, and this could have led to alternative results in the first round procedure, thus, impacting information generated from subsequent rounds. It is believed that the “blank slate” provided to participants created more flexibility and diversity of answers that led to successful subsequent Delphi rounds.

Another putative limitation is researcher bias. This was possible in that the research team selected the original definition, the first set of instructions, and the development of the round two list of items from the comments and suggestions from the first round. Although there are several ways to define OCBs, the research team chose only to provide one definition. This was intentional so as to lower participant burden/confusion and allow the generation of items to transpire under the auspices of a well-renowned and accepted conceptual definition. The list was developed based on the comments and suggested items from the participants. This limited the influence of the researchers in an attempt to maximize participant input.

The Delphi panel procedures were conducted over 4 years prior to the paper’s construction. The effects of history and maturation always have to be considered; however, there were no specific salient events that would have substantively altered the findings.

The proposed list of items requires validation and reliability testing for use as a measure of OCBs in a department or college or school. The items generated from this process should be employed in studies with larger sample sizes and validated using quantitative designs. Further refinement of the OCB measure would include factor analysis to evidence construct validity and comparing the resultant domains with those of Organ and others, in addition to reliability testing and examination of its convergent and discriminant validity properties. The use of this study’s procedures to inform item generation followed by the aforementioned quantitative approaches is commensurate with recommendations for the development of measures used in survey research.72 Once completed, an OCB measurement should be useful for post-secondary professional programs like pharmacy in assessing and benchmarking the citizenship behaviors of its faculty and determining how such behaviors affect the productivity and effectiveness of constituent faculty.

The items proffered to measure OCBs were generated from a process that included only pharmacy faculty members. An additional strength, particularly beginning with open-ended questions composing the round 1 procedure, allowed perceptions of citizenship behaviors to manifest from the lived experiences of these faculty members. As such, it might be said to have some unique properties related to pharmacy. However, the fact that the participants were not provided instruction to, nor did they comment overtly on, items particular to pharmacy make the items generated here particularly more useful, or at least readily adaptable to faculty members in other areas, which lends further strength to this study’s design.

CONCLUSION

A Delphi procedure was used to develop a list of perceived OCBs by faculty members in the field of pharmacy. The generated list contains items that are reflective of previously proposed dimensions of OCB for workers in less autonomous environments, but also offers measurement of facets unique to the job of an academician in general, perhaps with some uniqueness to those in a professional program. The items generated by the procedure provide appropriate guidance for faculty members by which to comport and to mentor/model onto others, in addition to providing a map for administrators for establishing a positive culture in the organization.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors acknowledge and thank the participants of the Delphi for their diligence in completing the study. The study was supported in part by a Pre-Doctoral Fellowship awarded to Dr. Peirce by the American Foundation for Pharmaceutical Education (AFPE).

Appendix 1. Pharmacy Faculty’s Perceptions of Important Organizational Citizenship Behaviors: A Delphi Procedure

Round 1 Survey

Thank you for agreeing to participate in our Delphi process. Your contributions will be invaluable toward defining organizational citizenship behaviors (OCBs) among pharmacy faculty that will eventually lead to a larger study examining faculty quality of work life and productivity. The purpose of Round 1 in the Delphi process is to identify OCBs that are unique from in-role job functions, or performance. In-role job performance “refers to employee’s formal role requirements” and includes examples such as publishing scholarly work, preparing for class, serving on committees, providing high quality clinical services, etc. A conceptual definition of OCBs is behaviors that go beyond requirements of your job that are not directly recognized in your formal reward system and facilitate organizational functioning, yet are discretionary in nature. They can be comprised of behaviors that include altruism, conscientiousness, sportsmanship, courtesy, civic virtue, reliability, helpfulness, and cooperation. OCBs are behaviors that benefit the organization in general, even if immediately benefiting specific individuals, because this indirectly benefits the organization. With this background we are asking you to answer the following questions:

1. Please identify up to 5 OCBs that you feel you have done for others and/or your institution.

2. Please identify up to 5 OCBs that you feel others and/or your institution have done for you, or other colleagues.

3. To what sources would you most attribute pharmacy faculty engaging in positive OCBs.

4. Please list up to 5 behaviors in which you have engaged that could be interpreted as anti-citizen-like or retaliatory in response to unfair treatment or policies by colleagues or administrators.

5. Please list up to 5 behaviors in which others have engaged that might be interpreted as anti-citizen-like in response to unfair treatment or policies by colleagues or administrators.

6. To what sources would you most attribute pharmacy faculty engaging in anti-citizen like or retaliatory behaviors.

Appendix 2. Pharmacy Faculty’s Perceptions of Important Organizational Citizenship Behaviors: A Delphi Procedure

Round 2 Survey

Part 1

From your Round 1 responses and a careful review of the literature we have proposed an initial set of items listed below that are potential items representative of both positive and negative Organizational Citizenship Behaviors. The purpose of Round 2 is to determine the appropriateness of these items to compose an OCB measure, AND NOT to report which of these you have experienced or engaged. We are asking you to rate each of these items for IMPORTANCE to compose the OCB measure. In other words, how impactful (either positively or negatively) is this behavior by a colleague on other colleagues and the organization (college/school of pharmacy), as a whole? Please circle your answer according to the scale below.

Part 2

Please identify any additional items not listed in Part 1 and/or make any suggestions for rephrasing or even combining any items from Part 1.

Appendix 3. Pharmacy Faculty’s Perceptions of Important Organizational Citizenship Behaviors: A Delphi Procedure

Rounds 3& 4 Surveys*

Part 1

Below are the Round 2 [3] items, the inter-quartile range and your response for each item. Some items have been modified, eliminated, or newly created based on your comments and those of your colleagues from the second round. In this third round of the Delphi you are asked to re-evaluate the IMPORTANCE of each of these items in potentially composing a measure of organizational citizenship behavior (OCBs). In other words, how impactful (either positively or negatively) is this behavior by a colleague on other colleagues and the organization (college/school of pharmacy), as a whole? Please remember that your responses SHOULD NOT be based on the extent to which you, personally, have experienced or engaged in these behaviors; but rather, the extent to which you feel this item is IMPORTANT in composing an instrument to measure OCBs. This is NOT to measure YOUR personal experiences with OCBs. Instead, it is to help us design a measure of OCBs. Please indicate in the Revised Response column your new response, even if your response is exactly the same as the previous round. Response Scale: 1= not important at all; 2 = slightly important; 3 = important; 4 = extremely important.

Part 2

Please briefly justify any responses that remain outside the 1st or 3rd quartiles of your colleagues’ responses.

* Round 3 & 4 Surveys were separate procedures, but identical instructions were used.

Appendix 4. Samples of Pharmacy Faculty Participants’ Direct Responses to Round 1 (open-ended) of the Delphi Procedure

“I appreciate it when faculty volunteer to do things that they don’t HAVE to do, especially since they are the ones often the busiest in the first place.” (Public, associate professor; led to item #9 in Table 1).

“Some faculty are almost always the first to help out and volunteer based on what is in their heart (and mind) to help the organization. Others, on the other hand, can never be found, even when really needed. (Private, full professor; also led to item #9 in Table 1).

“We have a mentoring program. It works, but people have to be careful not to step on any toes. A really good faculty member provides good counsel and mentorship when asked or given the opportunity. He or she doesn’t make a big deal about it or ask for attention or reward. They just go around helping people without fanfare and without stamping down the pride of other faculty.” (Public, full professor; led to item #17 in Table 1).

“A good citizenship behavior, knowing how much we are under pressure to produce scholarship, invites others to participate on projects. He or she doesn’t have to do this, but it is a good gesture, and doing so probably enhances or strengthens the project, anyway.” (Public, associate professor and assistant dean; led to item #19 in Table 1, that was then modified in subsequent rounds).

“Good citizenship, or what I would call collegial is when a faculty member keeps his word and makes good on his promises. On the other hand, we know faculty that do not. This sets a bad example for junior faculty. And besides, it probably leaves another faculty, most likely a junior one, left holding the bag.” (Private, full professor and department chair; led to #22 in Table 1).

“Oh my goodness. I can tell you that there are more senior faculty . . .well, faculty in general, who keep their word. By that I mean make good on their commitments. There are others who like to say in a general faculty meeting or somewhere else on public record that they are going to do so-and-so. Then they don’t. Their going back on their word ends up hurting others, mostly people like me, but not just people like me—everybody.” (Private, assistant professor; also led to #22 in Table 1).

“We are all busy. I really don’t know anyone who isn’t. Yet it is amazing how different people are in something so simple like returning emails. There are some who you can count on to respond immediately. Others practically never do so. This creates stress for the person sending the email, and often stress upon others needing that response, and perhaps even entire committees, students, staff, the whole school”. (Public, full professor; led to #30 in Table 1).

“A good citizenship behavior is prompt return of communication! It does not take long to return an email. If it would be a long response, you can pick up the phone or walk down the hall and speak to the person.” (Private, full professor; also led to #30 in Table 1).

REFERENCES

- 1.Organ DW. Organizational Citizenship Behavior: The Good Soldier Syndrome. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Katz D. The motivational basis of organizational behavior. Behav Sci. 1964;9(2):131–146. doi: 10.1002/bs.3830090206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morrison E. Role definitions and organizational citizenship behavior: the importance of the employee’s perspective. Acad Manage J. 1994;37(6):1543–1567. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Organ DW. Organizational citizenship behavior: It’s construct clean-up time. Human Performance. 1997;10(2):85–97. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Organ DW, Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB. Organizational Citizenship Behavior: Its Nature, Antecedents, and Consequences. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Podsakoff PM, Ahearne M, MacKenzie SB. Organizational citizenship behavior and the quantity and quality of work group performance. J Appl Psychol. 1997;82(2):262–270. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.82.2.262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Walz SM, Niehoff BP. Organizational citizenship behaviors: Their relationship to organizational effectiveness. J Hosp Tour Res. 2000;24(3):301–319. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koys DJ. The effects of employee satisfaction, organizational citizenship behavior, and turnover on organizational effectiveness: a unit-level, longitudinal study. Pers Psychol. 2001;54(1):101–114. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB. Organizational citizenship behaviors and sales unit effectiveness. J Mark Res. 1994;31(3):351–363. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bolino MC, Turnley WH, Bloodgood JM. Citizenship behavior and the creation of social capital in organizations. Acad Manage Rev. 2002;27(4):505–522. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ellinger AD, Ellinger AE, Bachrach DG, Wang Y-L, Elmadag Bas AB. Organizational investments in social capital, managerial coaching, and employee work-related performance. Management Learning. 2011;42(1):67–85. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bowling NA, Beehr TA, Johnson AL, Semmer NK, Hendricks EA, Webster HA. Explaining potential antecedents of workplace social support: Reciprocity or attractiveness? J Occup Health Psychol. 2004;9(4):339–350. doi: 10.1037/1076-8998.9.4.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.MacKenzie SB, Podsakoff PM, Fetter R. Organizational citizenship behavior and objective productivity as determinants of managerial evaluations of salespersons’ performance. Organ Behav Hum Dec Process. 1991;50(1):123–150. [Google Scholar]

- 14.MacKenzie SB, Podsakoff PM, Fetter R. The impact of organizational citizenship behavior on evaluations of salesperson performance. J Mark. 1993;57(1):70–80. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Podsakoff NP, Whiting SW, Podsakoff PM, Blume BD. Individual-and organizational-level consequences of organizational citizenship behaviors: a meta-analysis. J Appl Psychol. 2009;94(1):122–141. doi: 10.1037/a0013079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen X-P, Lam SSK, Naumann SE, Schaubroeck J. Group citizenship behaviour: conceptualization and preliminary tests of its antecedents and consequences. Manage Org Rev. 2005;1(2):273–300. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dunlop PD, Lee K. Workplace deviance, organizational citizenship behavior, and business unit performance: the bad apples do spoil the whole barrel. J Org Behav. 2004;25(1):67–80. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Orr JM, Sackett PR, Mercer M. The role of prescribed and nonprescribed behaviors in estimating the dollar value of performance. J Appl Psychol. 1989;74(1):34–40. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Allen TD, Rush MC. The effects of organizational citizenship behavior on performance judgments: a field study and a laboratory experiment. J Appl Psychol. 1998;83(2):247–260. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.83.2.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smith CA, Organ DW, Near JP. Organizational citizenship behavior: its nature and antecedents. J Appl Psychol. 1983;68(4):653–663. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Moorman RH, Fetter R. Transformational leader behaviors and their effects on followers' trust in leader, satisfaction, and organizational citizenship behaviors. Leader Quar. 1990;1(2):107–142. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Graham JW. Organizational Citizenship Behavior: Construct Redefinition, Operationalization, and Validation. Loyola: University of Chicago; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Moorman R, Blakely G. A preliminary report on a new measure of organizational citizenship behavior. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Southern Management Association1992; Valdosta, GA. 185–187.

- 24.Van Dyne L, Graham JW, Dienesch RM. Organizational citizenship behavior: Construct redefinition, measurement, and validation. Acad Manage J. 1994;37(4):765–802. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Williams LJ, Anderson SE. Job satisfaction and organizational commitment as predictors of organizational citizenship and in-role behaviors. J Manage. 1991;17(3):601–617. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Van Dyne L, LePine JA. Helping and voice extra-role behaviors: Evidence of construct and predictive validity. Acad Manage J. 1998;41(1):108–119. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Turnley WH, Bolino MC, Lester SW, Bloodgood JM. The impact of psychological contract fulfillment on the performance of in-role and organizational citizenship behaviors. J Manage. 2003;29(2):187–206. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Latham GP, Skarlicki DP. Criterion-related validity of the situational and patterned behavior description interviews with organizational citizenship behavior. Human Performance. 1995;8(2):67–80. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Somech A, Drach-Zahavy A. Understanding extra-role behavior in schools: the relationships between job satisfaction, sense of efficacy, and teachers’ extra-role behavior. Teaching and Teacher Education. 2000;16(5-6):649–659. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Deckop JR, McClendon JA, Harris-Pereles KL. The effect of strike militancy intentions and general union attitudes on the organizational citizenship behavior of university faculty. Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal. 1993;6(2):85–97. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gooty J, Gavin M, Johnson PD, Frazier ML, Snow DB. In the eyes of the beholder. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies. 2009;15(4):353–367. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Skarlicki DP, Latham GP. Increasing citizenship behavior within a labor union: a test of organizational justice theory. J Appl Psychol. 1996;81(2):161–169. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Skarlicki DP, Latham GP. Leadership training in organizational justice to increase citizenship behavior within a labor union: a replication. Pers Psychol. 1997;50(3):617–633. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oplatka I. Going beyond role expectations: toward an understanding of the determinants and components of teacher organizational citizenship behavior. Educ Adm Q. 2006;42(3):385–423. [Google Scholar]

- 35.DiPaola M, Tschannen-Moran M. Organizational citizenship behavior in schools and its relationship to school climate. Journal of School Leadership. 2001;11(5):424–447. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Regoxs A. Citizenship behaviours of university teachers. Active Learning in Higher Education. 2003;4(1):8–23. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jimmieson NL, Hannam RL, Yeo GB. Teacher organizational citizenship behaviours and job efficacy: implications for student quality of school life. Br J Psychol. 2010;101(3):453–479. doi: 10.1348/000712609X470572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.LePine J, Erez A, Johnson D. The nature and dimensionality of organizational citizenship behavior: a critical review and meta-analysis. J Appl Psychol. 2002;87(1):52–65. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.87.1.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Paine JB, Bachrach DG. Organizational citizenship behaviors: a critical review of the theoretical and empirical literature and suggestions for future research. J Manage. 2000;26(3):513–563. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Drucker PF. Management Challenges for the 21st Century. New York, NY: HarperCollins Publishers Inc.; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Holmes ER, Desselle SP. Is scientific paradigm important for pharmacy education? Am J Pharm Educ. 2004;68(5):Article 118. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Helmer O, Brown B, Gordon T. Social Technology. New York, NY: Basic Books; 1966. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brown B, Cochran S, Dalkey N. The Delphi Method, II; Structure of Experiments. Santa Monica, CA: The Rand Corp.; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dalkey NC. The Delphi Method: An Experimental Study of Group Opinion. Santa Monica, CA: The Rand Corp.; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- 45.McKenna HP. The Delphi technique: a worthwhile research approach for nursing? J Adv Nurs. 1994;19(6):1221–1225. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.1994.tb01207.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hassell K, Hibbert D. The use of focus groups in pharmacy research: processes and practicalities. J Soc Adm Pharm. 1996;13(4):169–177. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Conklin MH, Desselle SP. Development of a multidimensional scale to measure work satisfaction among pharmacy faculty members. Am J Pharm Educ. 2007;71(4):Article 61. doi: 10.5688/aj710461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Donabedian A. The Criteria and Standards of Quality. Explorations in Quality Assessment and Monitoring. Vol. II. Ann Arbor, MI: Health Admin. Press; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mullen PM. Delphi: myths and reality. J Health Organ Manag. 2003;17(1):37–52. doi: 10.1108/14777260310469319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hasson F, Keeney S, McKenna H. Research guidelines for the Delphi survey technique. J Adv Nurs. 2000;32(4):1008–1015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hatifield RD. Collegiality in higher education: toward an understanding of the factors involved in collegiality. J Org Culture Comm Conflict. 2006;10(1):11–20. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Shirk J, Miller M. Linking the faculty recognition process to teaching excellence. Paper presented at the National Conference on Successful College Teaching; February 1994; Orlando, FL. (ERIC No. ED390456).

- 53.Thomas C, Simpson DJ. Guest editorial: community, collegiality, and diversity: is there a conflict of interest in the professoriate. J Negro Educ. 1995;64(1):1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Menges RJ. Faculty in New Jobs: A Guide to Settling in, Becoming Established, and Building Institutional Support. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Blyn MR, Zoerner CE., Jr The academic string pushers: the origins of the upcoming cisis in the management of academia. Change. 1982;14(2):21–25. 60. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Conklin MH, Desselle SP. Job turnover intentions among pharmacy faculty. Am J Pharm Educ. 2007;71(4):Article 62. doi: 10.5688/aj710462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Desselle SP, Peirce GL, Crabtree BL, et al. Pharmacy faculty workplace issues: findings from the 2009-2010 COD-COF Joint Task Force on Faculty Workforce. Am J Pharm Educ. 2011;75(4):Article 63. doi: 10.5688/ajpe75463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.DiPaola MF, Hoy WK. School characteristics that foster organizational citizenship behavior. J School Leader. 2005;15(4):387–406. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Myers SA, Johnson AD. Perceived solidarity, self-disclosure and trust in organizational peer relationships. Comm Res Rep. 2004;21(1):75–83. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Turnipseed DL, Wilson GL. From discretionary to required: the migration of organizational citizenship behavior. J Leadership Org Studies. 2009;15(3):201–216. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Umphress EE, Tihanyi L, Bierman L, Gogus CI. Personal lives? The effect of nonwork behaviors on organizational image. Org Psychol Rev. 2013;3(3):199–221. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ross LA, Janke KK, Boyle CJ, et al. Preparation of faculty members and students to be citizen leaders and pharamcy advocates. Am J Pharm Educ. 2013;77(10):Article 220. doi: 10.5688/ajpe7710220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nahata M, Kelly K, McAuley J, et al. Reviewing vision and strategic priorities for an academic unit. Am J Pharm Educ. 2010;74(1):Article 13. doi: 10.5688/aj740113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kennedy RH, Gubbins PO, Luer M, Reddy IK, Light KE. Developing and sustaining a culture of scholarship. Am J Pharm Educ. 2003;67(3):Article 92. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Haines ST. The mentor-protégé relationship. Am J Pharm Educ. 2003;67(3):Article 82. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bird SJ. Mentors, advisors and supervisors: their role in teaching responsible research conduct. Sci Engineere Ethics. 2001;7(4):455–468. doi: 10.1007/s11948-001-0002-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.MacLaughlin EJ, Haase MR, Iron BK, et al. Assessing an academic pharmacy position: guidelines for evaluating an institution and roles for new faculty. Curr Pharm Teach Learn. 2009;1(1):17–24. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Haines SL, Popovich NG. Engaging external senior faculty members as faculty mentors. Am J Pharm Educ. 2014;78(5):Article 101. doi: 10.5688/ajpe785101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Donaldson SI, Ensher EA, Grant-Vallone EJ. Longitudinal examination of mentoring relationships on organizational commitment and citizenship behavior. J Career Dev. 2000;26(4):233–249. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wolfgang AP, Gupchup GV, Plake KS. Relative importance of performance criteria in promotion and tenure decisions: perceptions of pharmacy faculty members. Am J Pharm Educ. 1995;59(4):342–347. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Morgan DL. Focus groups. Annu Rev Sociol. 1996;22:129–152. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hinkin TR. A brief tutorial on the development of measures for use in survey questionnaires. Org Res Meth. 1998;1(1):104–121. [Google Scholar]