Abstract

Objective. To compare pharmacy, osteopathic medicine, dental medicine, and physician assistant (PA) students’ perceptions of e-professionalism.

Methods. A 20-item questionnaire was developed and administered to four cohorts of health care professions students early in their first professional year. The questionnaire contained 16 scenarios in which a hypothetical health care student or professional shared information or content electronically and students were asked to indicate how much they agreed that the scenario represented professional behavior.

Results. Ninety-four percent of students completed the questionnaire. More female students were in the pharmacy and PA cohorts. There were statistical differences in students’ perceptions of e-professionalism in five of 16 scenarios. Specific differences were most often between the osteopathic medicine students and the other cohorts.

Conclusions. The health care professions students surveyed had similar perceptions of e-professionalism. Of the four cohorts, osteopathic medicine students appeared less conservative in their approach to e-professionalism than the other cohorts.

Keywords: professionalism, e-professionalism, electronic media, health care students, interdisciplinary

INTRODUCTION

The concept of professionalism is highlighted in the codes of conduct and pledges of many health care disciplines.1-5 Additionally, professionalism is a common theme in academic health care curricula;6,7 however, health care professionals and educators still struggle to develop a common definition for professionalism.8 The use of electronic media to quickly share information has further complicated the topic of professionalism by generating interest in a subtopic known as e-professionalism. E-professionalism has been defined as “the attitudes and behaviors reflecting traditional professionalism paradigms but manifested through digital media.”9

Several recent studies examine the extent to which healthcare professional students are demonstrating e-professionalism and the degree to which colleges, residency directors, and state boards are monitoring this. In a study that surveyed deans and administrators in US medical schools, 60% of the respondents reported that their students had posted unprofessional material online. These materials included HIPAA violations, alcohol and drug use, and messages containing profanity. Some of these behaviors resulted in serious consequences for some students, including disciplinary action and even dismissal.10 A review of surgical residents’ publicly available Facebook profiles revealed that 14.1% of profiles contained potentially unprofessional material and 12.2% of profiles contained clearly unprofessional content, with binge drinking, sexually suggestive material, and potential HIPAA violations being the most common types of unprofessional content.11 A survey of pharmacy residency directors revealed that about 20% of respondents indicated they had reviewed residency candidates’ social media information, and more than 50% of these reviews resulted in detecting e-professionalism concerns.12

A national survey of State Medical Boards reported that the most common online violations by medical professionals as reported by patients and their families were sexual misconduct with patients, inappropriate use of the Internet for prescribing without seeing the patient in the clinic, and false representation of credentials. Some of the penalties for these violations were severe and included restriction, suspension, and revocation of licenses by 56% of the state boards.13

There are fewer studies that have examined healthcare professional students’ attitudes towards e-professionalism. A qualitative study to evaluate medical student’s perspectives on unprofessional online behavior concluded that students uniformly agreed that HIPAA violations and illegal activity were inappropriate. However, there were differing opinions regarding the inappropriateness of posting sexually suggestive material, content depicting the use of alcohol, or content containing disparaging remarks about faculty or other students.14 A survey of doctor of pharmacy (PharmD) students in their final year of study revealed that 78% thought that student pharmacists should be held accountable for illegal acts discovered by social media. In addition, 74% of respondents felt it was important to edit their social media sites before applying to a job. However, only about 50% of respondents felt it was appropriate for potential employers or residency directors to make hiring decisions based on the information they found in social media profiles.15

A survey of faculty and second- and fourth-year PharmD students revealed that second-year pharmacy students and faculty members were more aligned in what they considered unprofessional online behavior. Fourth-year students were more complacent in what they perceived as unprofessional online behavior. Students were also more likely to make unprofessional comments when they thought the social media site was private.16 What remains unclear from the literature is whether health care professions students across the disciplines have the same perceptions of what constitutes professional behavior in online domains. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to examine pharmacy, osteopathic medicine, dental medicine, and physician assistant (PA) students’ attitudes toward e-professionalism behaviors.

METHODS

A survey instrument developed previously by Lee, Gettig and Fjortoft16 consisting of e-professionalism scenarios that describe behaviors in four electronic domains was reviewed and revised. The original survey instrument was modified to make the items nondiscipline specific and student centered. The number of items from the original survey instrument was also reduced, eliminating items that were redundant or were not frequently observed behaviors as noted in the previous study.16 One additional question was added to address students video recording class activities and then later posting them online. Students were asked to respond to their level of agreement regarding whether the behaviors described were professional, using a Likert scale (ie, strongly agree=5, agree=4, neutral=3, disagree=2, strongly disagree=1). Some items described positive professional behaviors, some items were purposely ambiguous, and some items described unprofessional behaviors. Two additional demographic questions (age and gender) were added, and two questions (mother’s first name and the student’s month and day of birth) were included to allow for pairwise comparisons if the survey were readministered at a later date. Cohort data about highest previous degree earned were collected directly from the university’s registrar.

The study population for this project consisted of first professional year students enrolled for the summer and fall 2014 semesters in Midwestern University’s Chicago College of Pharmacy, (n=210) Chicago College of Osteopathic Medicine, (n=208), College of Dental Medicine-Illinois, (n=132) and the Physician Assistant Program in the College of Health Sciences (n=87).

The survey was administered via paper and pencil to all students within one month of their orientation. Participation was voluntary, and students were assured their responses would remain anonymous. The survey was conducted during required class activities to ensure maximum participation, and was administered by a trained facilitator who was not an investigator in this project to ensure that students did not feel pressured to complete the survey. A study information sheet was provided to each student along with the survey instrument. The study was reviewed by Midwestern University’s Institutional Review Board and was found to be exempt.

Survey forms were collected, and an administrative assistant entered all data into Microsoft Excel. Data analysis was conducted using SPSS for Windows, version 22 (IBM Corp., Amonk, NY).

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) and chi-square analyses were used to compare the demographic characteristics of students. ANOVA was used to compare survey results among students. When variance was unequal across cohorts, the Welch F test was used to confirm or refute the ANOVA result. When ANOVA detected a significant difference across the four cohorts of students, the Scheffe (equal variance assumed) or Dunnett C (equal variance not assumed) post hoc tests were used to identify where specific differences between cohorts existed. Alpha was set a priori at.05.

RESULTS

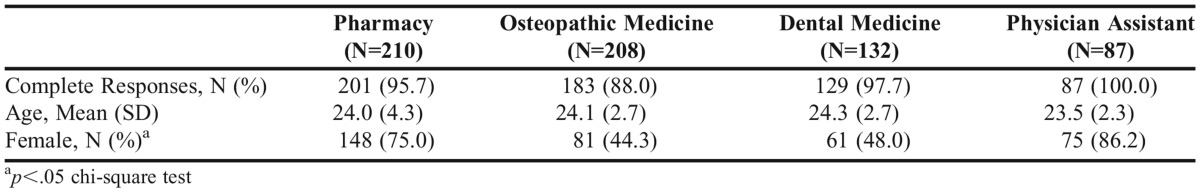

The overall response rate to the survey on e-professionalism was 94.2% (600/637). The individual cohort response rates were as follows: 95.7% (201/210) for pharmacy students, 88.0% (183/208) for osteopathic medicine students, 97.7% (129/132) for dental students, and 100% (87/87) for PA students (Table 1).

Table 1.

Response Rates, Age and Sex of Health Care Student Cohorts

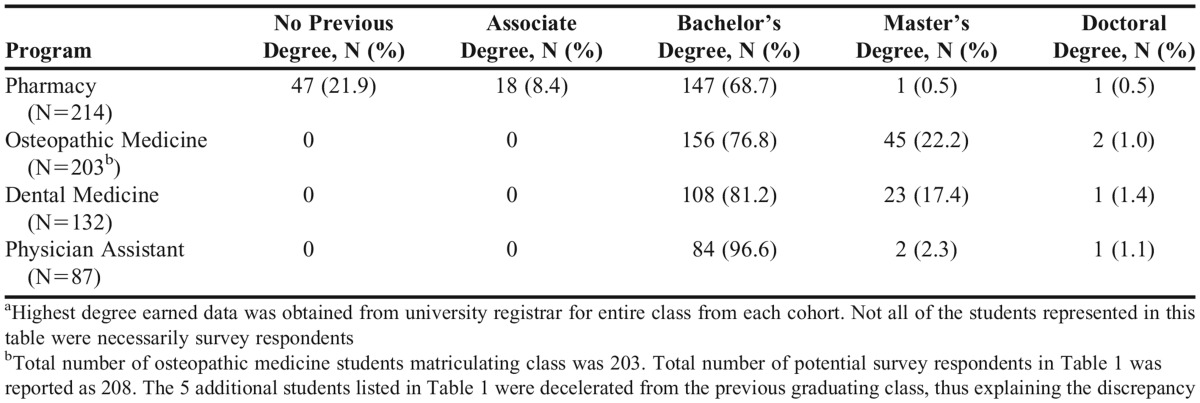

The average age and gender of the respondents is presented in Table 1. The average ages of students were comparable across cohorts, but pharmacy students had the largest variance in age within their cohort. There was a significant difference in the distribution of gender among the cohorts. A large majority of pharmacy and PA students were female, while a slight majority of osteopathic medicine and dental medicine students were male. The highest previous degrees earned by each cohort are presented in Table 2. Because this information was collected directly from the university’s registrar, the data in Table 2 represent the percentage of the entire population of each cohort that earned a particular degree rather than the percentage of respondents that earned a particular degree. The majority of students across all cohorts had at least a bachelor’s degree. About 30% of pharmacy students had no previous degree (21.9%) or had an associate’s degree (8.4%).

Table 2.

Highest Degree Earned by Population Cohorta

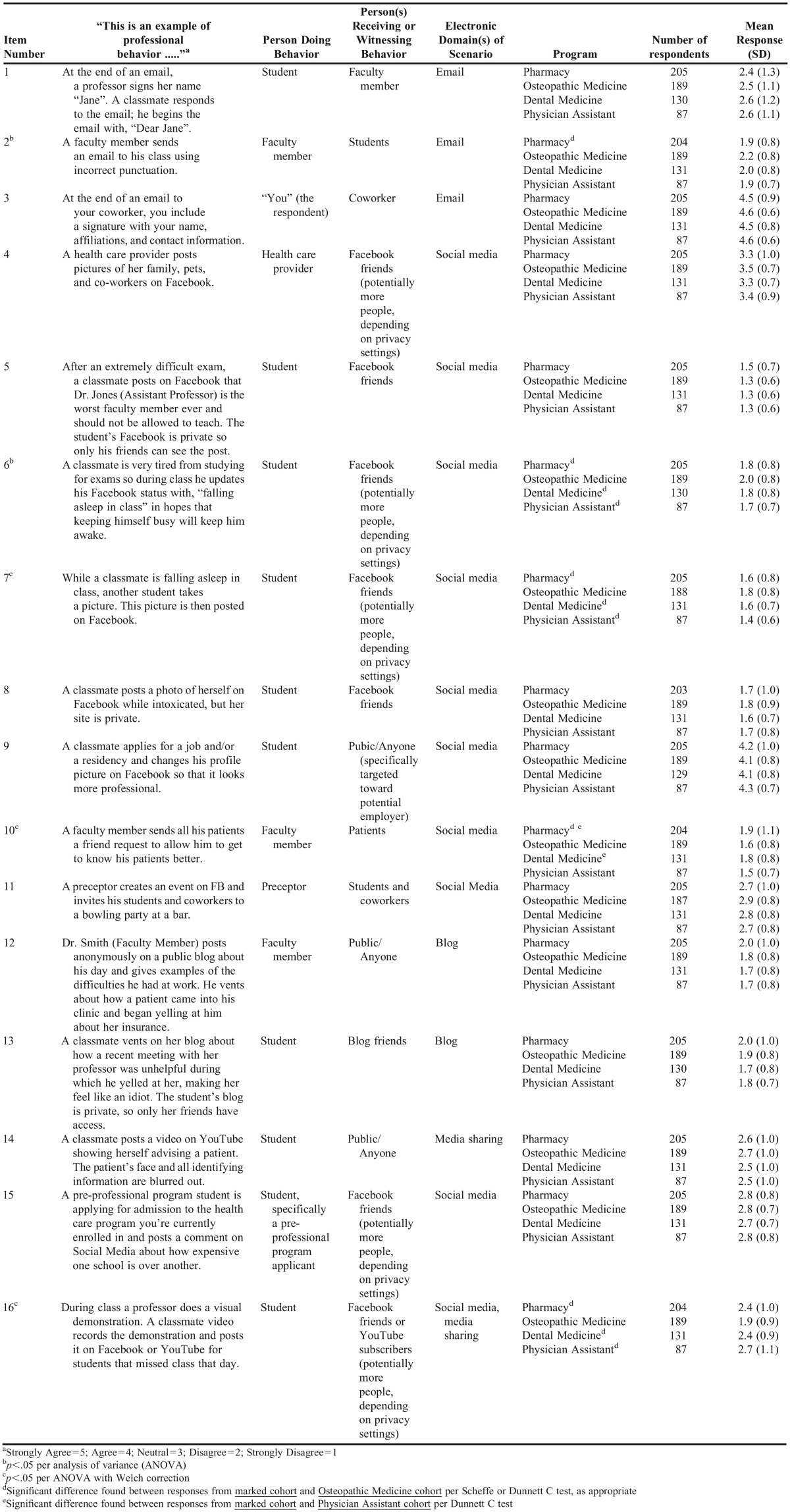

Table 3 outlines each of the survey items and each cohort’s response to the statement, “This is an example of professional behavior.” In addition, Table 3 characterizes each item in terms of the person doing the behavior, the person(s) receiving or witnessing the behavior, and the electronic domain(s) in which the behavior was performed. For example, item 1 reads: “At the end of an email, a professor signs her name ‘Jane.’ A classmate responds to the email; he begins the email with, ‘Dear Jane.’” In this example, the person doing the behavior in question is the student sending the response email. The person receiving or witnessing the behavior is the faculty member who received the email starting with “Dear Jane.” The electronic domain in this example is email.

Table 3.

E-professionalism Scenario Characteristics and Survey Responses

Respondents disagreed or strongly disagreed that most of the items represented professional behavior. For example, the mean response was between 1 (strongly disagree) and 2 (disagree) for most cohorts for eight (50%) of the items (items 2, 5, 6, 7, 8, 10, 12 and 13). The mean response was between 2 (disagree) and 3 (neutral) for most cohorts for five (31.3%) of the items (items 1, 11, 14, 15 and 16). There was one item that that was perceived neutrally by most students (item 4) and two items that were perceived positively (items 3 and 9) across cohorts.

Significant differences were found in five of the 16 items (items 2, 6, 7, 10 and 16). The first item for which there were significantly different responses was item 2, “A faculty member sends an email to his class using incorrect punctuation.” The mean response for this item ranged from 1.9 for pharmacy students to 2.2 for osteopathic medicine students (p<.05). The Scheffe post-hoc test found the specific significant difference between the osteopathic medicine and pharmacy cohorts for this question. In items 6, 7, and 16, there were specific significant differences found between each of the student cohorts and the osteopathic medicine student cohort. In item 10, a specific significant difference in responses was found between the pharmacy student cohort and the osteopathic medicine student cohort. In addition, specific differences were also detected between the pharmacy student cohort and PA student cohort and between the dental medicine student cohort and the PA student cohort for item 10.

DISCUSSION

Overall, students in all four cohorts were able to appropriately identify behaviors in various electronic domains as professional or unprofessional. Students perceived 13 of 16 behaviors (81.3%) as generally unprofessional, which coincides with the researchers’ judgments and response expectations. Interestingly, the tone of the behavior described appeared to influence how strongly a student rated something as unprofessional. For example, items 5, 6, 7, 8, 12, and 13 describe scenarios in which someone shares something negative about themselves or someone else electronically, usually through posting to social media. Consider item 5 which reads: “After an extremely difficult exam, a classmate posts on Facebook that Dr. Jones (Assistant Professor) is the worst faculty member ever and should not be allowed to teach. The student’s Facebook is private so only his friends can see the post.” In this scenario, a student is clearly posting something negative (“worst faculty member ever,” “should not be allowed to teach”) about a faculty member on social media. The mean responses of students from all cohorts ranged from 1.3±0.6 for PA students to 1.5±0.7 for pharmacy students. These responses indicate a strong level of disagreement with the statement “This is an example of professional behavior.”

One way in which students did not respond in a manner consistent with researchers’ expectations had to do with the perception of privacy. For example, in item 5 (described above), the person doing the behavior, a student in this case, has his Facebook account set to private, meaning only his friends could see his post. Contrast this to item 7 which reads: “While a classmate is falling asleep in class, another student takes a picture. This picture is then posted on Facebook.” Item 7 describes a negative situation by most standards given that students are expected to stay awake in class. We intentionally did not include specifics about the privacy settings of the person doing the behavior in item 7; however, overwhelmingly, students strongly disagreed or disagreed that this was an example of professional behavior. Mean responses ranged from 1.4±0.6 for PA students to 1.8±0.8 for osteopathic medicine students (p<.05 for all cohorts compared to osteopathic medicine students). In comparing responses to items 5 and 7, it appears students perceived item 5 as being more unprofessional than item 7, but these differences are not as pronounced as researchers anticipated given that item 5 clearly describes posting to a private Facebook account versus item 7, which leaves interpretation of privacy settings to the students. The researchers believe this lack of distinction with respect to privacy settings is a positive finding. It appears that the vast majority of health care professions students surveyed were able to identify unprofessional behaviors regardless of the intended audience.

Students’ perceptions of items that described behaviors in a more neutral manner were more mixed. For example, items 1, 3, 4, 10, 11, 14, 15, and 16 are scenarios in which there are no clear and intentional negative or positive descriptors. Student responses were mixed across these items. Mean responses were between 2 (disagree) and 3 (neutral) for items 1, 11, 14 and 16. Contrast this to mean responses for item 10, which were between 1 (strongly disagree) and 2 (disagree) and mean responses for items 3 and 4, which were more positive. Consider item 14 which reads: “A classmate posts a video on YouTube showing herself advising a patient. The patient’s face and all identifying information are blurred out.” There is nothing inherently negative or positive in the language of this item; however, students, on average, disagreed or felt neutral that this was an example of professional behavior. Mean responses ranged from 2.5±1.1 for dental medicine students to 2.7±1.1 for osteopathic medicine students. The generally negative perception of the behavior described in item 14 may stem from concerns over patient privacy and the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA). However, students who rated this behavior as neutral may not have understood that even though a patient’s face and all identifying information are blurred out, the patient could still be identified if someone watching the video knew what rotation the student was on, the hospital where the video was recorded, or if the disease or treatment was a rare event. When interpreting the findings, it is important to keep in mind that these are all first year students who had not completed any clinical rotations at the time of the study. With more didactic coursework and more experiential training, students may gain a better appreciation for all of the potential ways in which HIPAA can be violated.

Although there were no clear negative or positive descriptors in item 3, students generally interpreted the scenario described as professional. Item 3 reads: “At the end of an email to your coworker, you include a signature with your name, affiliations, and contact information”. Mean responses ranged from 4.5±0.9 for pharmacy students to 4.6±0.6 for PA students. The positive perception of item 3 may stem from students’ belief that name and contact information, which are often found in faculty members’ and other professionals’ email auto-signatures, are associated with someone in a professional position. Item 9 was the only other item with mean responses between 4 (agree) and 5 (strongly agree). Item 9 reads: “A classmate applies for a job and/or a residency and changes his profile picture on Facebook so that it looks more professional.” Mean responses ranged from 4.1±0.8 for dental medicine and 4.3±0.7 for PA students. Unlike item 4, item 9 contained the phrase “so that it looks more professional,” which may have directly influenced students’ perception that this was professional behavior. Although the researchers agree that item 9 represents professional behavior, we recognize that this item may need to be edited to change the response cue “so that it looks more professional” to something less leading.

The results indicate that there are some significant differences in perceptions of professionalism among the four cohorts in this study. However, the clinical significance of these differences is less clear given that a difference of .8 in mean response was the largest difference detected between 2 cohorts (PA students: 2.7±1.1; osteopathic medicine students: 1.9±0.9). This difference was noted in item 16, which reads: “During class a professor does a visual demonstration. A classmate video records the demonstration and posts it on Facebook or YouTube for students that missed class that day.” It is difficult to conjecture if osteopathic medicine students’ more negative perceptions about item 16, which is still less than a full Likert scale unit of 1, carries a deeper meaning worthy of further exploration.

In fact, the reasons behind the significant differences found in items 2, 6, 7, 10, and 11 are unclear. However, 4 out of the 5 items with significantly different sets of responses included specific significant differences between one or more cohorts and the osteopathic medicine student cohort. The osteopathic medicine student cohort had the smallest percentage of female students (Table 1) and the largest combined percentage of student with a bachelor’s or master’s degree (Table 2). In addition, the degree programs in which the cohorts were enrolled had varying prerequisite requirements, which may have impacted the students’ academic experience and maturity. The cohorts’ significantly different perceptions of e-professionalism were more than likely influenced by a combination of factors.

Responses to two of the items warrant further discussion in the context of published guidelines. First, item 4 reads: “A health care provider posts pictures of her family, pets, and co-workers on Facebook.” There is no mention of how private the Facebook account is in this scenario. Mean responses for all four cohorts were between 3 (neutral) and 4 (agree). Although students were relatively neutral about this item, guidelines recommend that healthcare professionals separate their personal and professional lives online. In a position paper from the American College of Physicians and the Federation of State Medical Boards,17 the authors recommended that physicians maintain separate online personas for their personal lives and professional lives. The authors suggest that patients may interpret physicians’ thoughts and opinions on social media as representative of the entire medical profession and that separate personas are needed to maintain public trust in medical professionals. Although the content of item 4 is relatively benign, students’ neutral to positive perceptions of this scenario in light of these guidelines may warrant further exploration.

Another area of particular interest is reflected in item 10, which reads: “A faculty member sends all his patients a friend request to allow him to get to know his patients better.” Guidelines17 recommend against physicians “friend” requesting patients through social media because doing so may diminish the professional boundaries between physicians and patients. Students’ mean responses ranged from 1.5±0.7 for PA students to 1.9±1.0 for pharmacy students, and significant differences were noted among the four cohorts. Osteopathic medicine and PA students overall were more likely to strongly disagree that this behavior was professional than were pharmacy and dental medicine students. While the clinical significance of these differences appears small, perhaps pharmacy and dental medicine students feel less strongly about this scenario because of the way they typically interact with patients in the community setting or the way they promote their private businesses through social media.

As health care moves to more team-based care, there is a need for the health care professions to agree on a definition or set of definitions for the broader concept of professionalism, and then subsequently, e-professionalism. A 2014 meta-analysis8 of 26 publications about professionalism in medical education determined that there is no universally accepted definition of “professionalism.” However, a 2014 editorial18 from the American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS) Standing Committee on Ethics and Professionalism explained the ABMS’ 2012 unanimous vote for the concept of professionalism to be defined as an underlying belief system rather than a list of values or behaviors. The ABMS argues that if professionalism is defined as a belief system, (1) clinical competency and ethics are equally important parts of the concept of professionalism, (2) clinicians will need to share accountability and self-regulate their actions, and (3) clinicians may lose public trust if they do not prove themselves worthy of trust.

If we choose to define professionalism as a belief system, then how does e-professionalism fit into this? Current younger generations are very much at ease with the use of social media in their personal and professional lives. The boundaries between personal information and professional information are sometimes blurred, and students may unknowingly cross boundaries that have not been clearly defined. Educators are faced with having to decide if it is acceptable to access students’ personal information that is publically available and whether students can be deemed unprofessional based on something that they have shared or done in their public “private” lives, regardless of how they present themselves in their professional lives. Views on this may vary, and some believe that material available online and accessible by anyone is fair game, while others may not agree with this philosophy.9

The results of this survey study as a whole may best serve as a starting point for further exploration of students’ perceptions of the concept of e-professionalism, especially in situational contexts. The more educators understand students’ perceptions of e-professionalism, the more educators will be able to positively influence their actions in electronic domains. Educators can shape students’ sense of e-professionalism by (1) developing and educating students on guidelines and policies regarding appropriate use of electronic media, and (2) teaching students about personal digital branding. Recent surveys of US dental medicine schools and US medical schools revealed that only 47.8% and 10% of respondents had social media policies in place, respectively.19,20 A medical school in Canada had some success with an educational approach. The researchers searched for medical students’ profiles on Facebook and used what they found to educate the students about appropriate privacy settings. One month after the education, they repeated the search and found a significant reduction in the number of profiles that shared personal information and personal photographs.21 Personalizing the learning experience for students instead of merely reciting a university policy may better help students appreciate their professional online image.

“Personal digital brand” has been defined as “a strategic self-marketing effort, crafted via social media platforms, which seeks to exhibit an individual's professional persona.”22 The negative effects of social media have been emphasized in the literature, which could influence students to avoid having an online persona all together. However, patients may interpret a lack of an online presence as an inability to communicate in the digital age. Educating students about how to develop and successfully manage a personal digital brand will be help them find a balance between appearing professional yet distant, and appearing unprofessional yet human.

The four cohorts of students in this study began their professional program studies having varying prerequisites and general life experience. Also, the survey was administered to the cohorts on different dates. All of these factors may have impacted the results. In addition, students’ previous work experience in healthcare environments also may have affected their responses. Although all students were assured that their responses would remain anonymous, some osteopathic medicine students were concerned about researchers identifying their responses by their mother’s first name and their month and day of birth. Finally, some of the language used in the survey items may have been new and unclear to first-year students. For example, some students may not have known what “preceptor” meant, and this may have impacted their response to the item containing this word.

CONCLUSION

While students from four different health care programs agreed about the degree of professionalism reflected in the majority of scenarios presented in the survey, some differences existed. Some cohorts demonstrated a lack of consistency about their attitudes toward e-professionalism. When differences existed, osteopathic medicine students appeared to have a slightly more relaxed attitude toward e-professionalism than the other three cohorts; however, the reasons for the differences and clinical significance of the differences are difficult to determine.

The results of this study can be used by health professions educators and academic administrators to shape discussions with students about e-professionalism and to ultimately develop college policies that promote professionalism while recognizing our future health care professionals’ evolving attitudes toward electronic communication and social media.

Footnotes

Note: John Graneto was affiliated with Midwestern University Chicago College of Osteopathic Medicine, Downers Grove, Illinois, at the time of research planning and execution.

REFERENCES

- 1. Code of Medical Ethics, American Medical Association. https://www.ama-assn.org/about-us/code-medical-ethics Accessed December 14, 2016.

- 2. Osteopathic Pledge of Commitment, American Association of Colleges of Osteopathic Medicine. http://www.aacom.org/become-a-doctor/about-om/osteopathic-pledge-of-commitment. Accessed November 15, 2015.

- 3. Code of Ethics for Pharmacists, American Pharmacists Association. http://www.pharmacist.com/code-ethics. Accessed November 15, 2015.

- 4. Principles of Ethics and Code of Professional Conduct, American Dental Association. http://www.ada.org/∼/media/ADA/Publications/Files/ADA_Code_of_Ethics_2016.pdf?la=en. Accessed December 14, 2016.

- 5. Guidelines for Ethical Conduct for the Physician Assistant Profession, American Academy of Physicians Assistants. https://www.aapa.org/WorkArea/DownloadAsset.aspx?id=815. Accessed November 15, 2015.

- 6.Englander R, Cameron T, Ballard AJ, Dodge J, Bull J, Aschenbrener CA. Toward a common taxonomy of competency domains for the health professions and competencies for physicians. Acad Med. 2013;88(8):1088–1094. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31829a3b2b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Medina MS, Plaza CM, Stowe CD, et al. Center for the Advancement of Pharmacy Education 2013 Educational Outcomes. Am J Pharm Educ. 2013;77(8):Article 162. doi: 10.5688/ajpe778162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Birden H, Glass N, Wilson I, Harrison M, Usherwood T, Nass D. Defining professionalism in medical education: a systematic review. Med Teach. 2014;36(1):47–61. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2014.850154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cain J, Romanelli F. E-professionalism: a new paradigm for a digital age. Curr Pharm Teach Learn. 2009;1(2):66–70. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chretian KC, Greyson SR, Chretian JP, Kind T. Online posting of unprofessional content by medical students. J Am Med Assoc. 2009;302(12):1309–1315. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Langenfeld SJ, Cook G, Sudbeck C, Luers T, Schenarts PJ. An assessment of unprofessional behavior among surgical residents on Facebook: a warning of the dangers of social media. J Surg Educ. 2014;71(6):e28–e32. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2014.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cain J, Scott DR, Smith K. Use of social media by residency program directors for resident selection. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2010;67(19):1635–1639. doi: 10.2146/ajhp090658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Greysen SR, Chretien KC, Kind T, Young A, Gross CP. Physician violations of online professionalism and disciplinary actions: a national survey of state medical boards. J Am Med Assoc. 2012;307(11):1141–1142. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chretian KC, Goldman EF, Beckman L, Kind T. It’s your own risk: medical student’s perspectives on online professionalism. Acad Med. 2010;85(10 Suppl):S68–S71. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181ed4778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ness GL, Sheehan AH, Snyder ME, Jordan J, Cunningham JE, Gettig JP. Graduating pharmacy students’ perspectives on e-professionalism and social media. Am J Pharm Educ. 2013;77(7):Article 146. doi: 10.5688/ajpe777146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gettig JP, Lee N, Fjortoft N. Student and faculty observations and perceptions of professionalism in online domain scenarios. Am J Pharm Educ. 2013;77(9):Article 192. doi: 10.5688/ajpe779192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Farnan JM, Sulmasy LS, Worster BK, Chaudry HJ, Rhyne JA. Arora VM for the American College of Physicians Ethics, Professionalism and Human Rights Committee; American College of Physicians Council of Associates; Federation of State Medical Boards Special Committee on Ethics and Professionalism*. Online medical professionalism: patient and public relationships: policy statement from the American College of Physicians and the Federation of State Medical Boards. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(8):620–627. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-8-201304160-00100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wynia MK, Papadakis MA, Sullivan WM, Hafferty FW. More than a list of values and desired behaviors: a foundational understanding of medical professionalism. Acad Med. 2014;89(5):712–714. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Henry RK, Webb C. A survey of social media policies in US dental schools. J Dental Educ. 2013;78(6):850–855. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kind T, Genrich G, Sodhi A, Chretian KC. Social media policies in US medical schools. Med Educ Online. 2010;15:5324. doi: 10.3402/meo.v15i0.5324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Walton JM, White J, Ross S. What’s on YOUR Facebook profile? Evaluation of an educational intervention to promote appropriate use of privacy settings by medical students on social networking sites. Med Educ Online. 2015;20:28708. doi: 10.3402/meo.v20.28708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kleppinger CA, Cain J. Personal digital branding as a professional asset in the digital age. Am J Pharm Educ. 2015;79(6):Article 79. doi: 10.5688/ajpe79679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]