Abstract

Objective. To examine the extent to which reflective essays written by graduating pharmacy students revealed professional identity formation and self-authorship development.

Design. Following a six-week advanced pharmacy practice experience (APPE) grounded in Baxter-Magolda’s Learning Partnerships Model of self-authorship development, students completed a culminating reflective essay on their rotation experiences and professional identity formation.

Assessment. Thematic and categorical analysis of 41 de-identified essays revealed nine themes and evidence of all Baxter-Magolda’s domains and phases of self-authorship. Analysis also suggested relationships between self-authorship and pharmacist professional identity formation.

Conclusion. Results suggest that purposeful structuring of learning experiences can facilitate professional identity formation. Further, Baxter-Magolda’s framework for self-authorship and use of the Learning Partnership Model seem to align well with pharmacist professional identify formation. Results of this study could be used by pharmacy faculty members when considering how to fill gaps in professional identity formation in future course and curriculum development.

Keywords: professional identity formation, self-authorship, Learning Partnerships Model, professionalism, reflective writing

INTRODUCTION

Accreditation standards for the doctor of pharmacy (PharmD) curricula place heavy emphasis on professionalism development, but there is little in academic literature describing pedagogical methods for promoting professional identity formation (PIF) in pharmacy students.1 Professional identity formation has been described as “the transformative process of identifying and internalizing the ways of being and relating within a professional role” by adopting characteristics of a professional, such as altruism, respect for others, honesty and integrity, and commitment to self-improvement.1-5 One approach to PIF is Baxter-Magolda’s theory of self-authorship. Self-authorship theory describes combined cognitive and affective development and offers the Learning Partnerships Model as a pedagogical approach to promoting combined personal development.

The purpose of this study was to examine the extent to which reflective narrative essays written by graduating pharmacy students revealed PIF and self-authorship development, and how use of Baxter-Magolda’s framework for self-authorship might contribute to PIF as observed in these essays. If self-authorship theory can be applied to professional identity formation in pharmacy students, then Baxter-Magolda’s pedagogical Learning Partnerships Model can then be used by faculty members to design learning experiences that facilitate PIF.

The Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE) and Center for the Advancement of Pharmacy Education (CAPE) consider the development of professional attitudes and values in pharmacy students a priority for colleges and schools of pharmacy.2,3 Professionalism is considered vital to the profession of pharmacy because of its connections to maintaining competency in pharmacy practice through lifelong learning, the development of trusting relationships with patients and the collaborative health care team, advocacy for the advancement of the profession, and the public’s image of the profession.

The 2011 Report of the American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy (AACP) Professionalism Task Force states that the responsibility for the development of professional attitudes and behaviors ultimately lies with pharmacy students.4 The Pledge of Professionalism adopted by the American Pharmaceutical Association Academy of Students of Pharmacy and the AACP Council of Deans Task Force on Professionalism describes the need for students to voluntarily and consciously dedicate themselves to the development of a “professional identity.”5

However, because pharmacy student professionalism is influenced by pharmacy faculty members, educators in colleges and schools of pharmacy are encouraged to develop assignments and experiences that promote PIF in pharmacy students.5 Numerous publications have attempted to define professional characteristics, describe the role of pharmacy educators in the development of pharmacy student professionalism, promote an increasing focus on professionalism in the pharmacy curriculum, and offer tools for developing and assessing student professionalism.6-14 There is little consensus in the pharmacy literature on exactly how pharmacy faculty members should best support students’ PIF, which underscores the importance of this study.

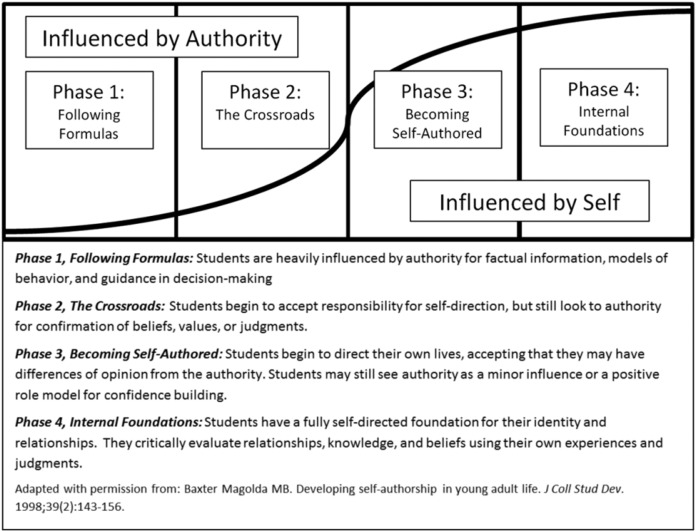

One of ACPE’s many goals for pharmacy graduates is the development of the student as a professional and self-directed, lifelong learner.2 The development of these and other necessary professional characteristics is analogous to Marcia Baxter-Magolda’s theory of self-authorship transition.15 Self-authorship describes an individual’s development of combined cognitive and affective maturity, defined as “the ability to collect, interpret, and analyze information and reflect on one’s own beliefs in order to form judgments.”16 Baxter-Magolda’s developmental theory of self-authorship describes the process a student undergoes during each of four transitional phases moving from reliance on authority figures to define herself to reliance on self-definition and self-influence (Figure 1).17 In this study, the authors attempted to demonstrate how self-authorship theory as described by Baxter-Magolda may be useful in pharmacy faculty members’ understanding of professional development in pharmacy students, in particular, PIF.

Figure 1.

Theoretical Relative Weight of Influence by Authority and Self During the Four Phases of The Transition to Self-authorship.

Students begin their journey to professionalism in the first developmental phase of self-authorship, known as “Following Formulas.” In this phase of PIF, students observe role models and preceptors delivering lectures and engaging in patient care activities. They accept as immutable fact knowledge, perceptions, beliefs, and values from authority figures, such as preceptors, and are not inspired to analyze, critique, or evaluate the words or actions of that authority.

Students transition to the second phase of self-authorship and professional identity development, known as the “Crossroads,” when they accept responsibility for evaluating the knowledge and values gained by observing authority figures and recognize their own role in developing an internal voice to guide their decision-making. This second phase involves beginning to self-select priorities for individual professional identity, and judging the actions of others in relation to personal moral and ethical beliefs. Rather than blindly trusting authority figures, students begin to evaluate whether they should trust the authority figure by assessing the preceptors’ actions against the students’ own beliefs and morality.

In the third phase of the transition, “Becoming Self-Authored,” students begin to demonstrate internal guidance. They practice professional characteristics and traits by evaluating scientific claims and building relationships with interprofessional team members and patients. An important aspect of this phase is acceptance by the students of the need for continued professional growth. At the conclusion of a professional experience or interaction, students should reflect on their actions and behaviors to determine opportunities for improvement. Students understand that the situational nature of knowledge and behavior, and continued PIF relies on their ability to reflect and refine for the purposes of personal and professional growth.

An individual who has mastered the art of critical self-evaluation and reflection has achieved the fourth phase of self-authorship development, “Internal Foundations.” These individuals confidently embody a professional identity founded on their unique, personal perspective. Applying the same skills needed to critically evaluate their own professional actions, self-authored individuals also use their individual perspective to participate in active knowledge generation with colleagues. These individuals also build collaborative relationships with diverse others, valuing social and/or cultural differences that bring a variety of perspectives to their work. Self-authored individuals have developed an internal authority or professional identity that guides their independent learning, critical thinking, mature decision-making, and development of tolerant, collaborative relationships with diverse others.15-17

Transition between these phases, or professional identity growth and development, is stimulated by provocative experiences that shake a student’s beliefs and encourage reflection.15-17 These provocative experiences can occur naturally or can be stimulated by activities designed according to the Learning Partnerships Model of self-authorship development.18

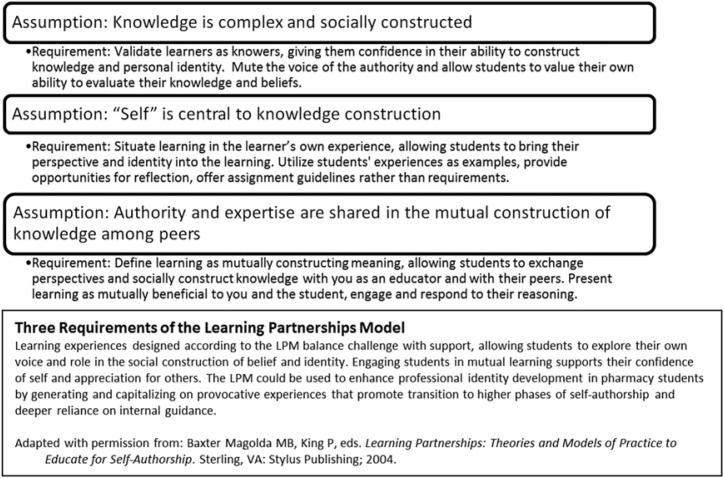

The pedagogical Learning Partnerships Model (LPM) describes learning experiences designed to imitate the effects of those provocative experiences.18 According to the LPM, learning experiences that promote self-authorship must challenge students to define their own knowledge and perspectives by (1) portraying knowledge as complex and socially constructed, (2) situating the student’s “self” as central to knowledge construction, and (3) engaging students in mutual learning with peers (Figure 2).18 In pharmacy education, if faculty members developed explicit learning experiences using the LPM, then students’ transition to self-authored professional identity might be more effectively achieved.

Figure 2.

Three Requirements of the Learning Partnerships Model.

Thomas Zlatic suggests that reflective writing is a tool to promote critical-thinking, communication, and problem-solving skills in pharmacy students.19,20 Reflective writing allows students the opportunity to recount and interpret the impact of significant events on their identity. In writing, students formulate and refine their ideas, and in the process, gain a deeper understanding of their beliefs and values and how these influence perceptions and actions. Because the intent of writing is to communicate with others, the authors are forced to provide evidence justifying those beliefs. Thus, reflective writing promotes critical-thinking skills.19,20

A review of reflective practices in pharmacy education examines the potential value of reflection in the development of skills vital to critical thinking, self-directed lifelong learning, and professional development, and questions the limited use of reflection in pharmacy education.21 Reflection could be employed as part of the Learning Partnerships Model to aid students in the transition to self-authorship. For example, explicit use of reflective writing could help students identify and reflect critically on their beliefs, observations, and experiences, and how these influence their actions and relationships with others and who they are becoming as pharmacists.

DESIGN

The learning activity from which data were derived for this study was integrated into an APPE, with the first author serving as preceptor in a critical care/internal medicine setting at a 200-bed academic medical center. The six-week rotation was offered for two to three students on each of seven APPE rotations per academic year. The activity was designed according to Baxter-Magolda’s Learning Partnerships Model and consisted of two phases.

A major criterion for self-authorship is the critical evaluation of knowledge imparted by authority (eg, statements) before integrating that knowledge into ones’ own beliefs.15-17 At the beginning of the rotation, students completed a reading assignment consisting of three published articles representing the “authority” on pharmacy professionalism and pharmacy practice.22-24 The first article, the American College of Clinical Pharmacy’s “Tenets of Professionalism for Pharmacy Students,” proposes six core values for pharmacy professionals: altruism, honesty and integrity, respect for others, professional presence, professional stewardship, and dedication and commitment to excellence.22 The second article, the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists’ “Statement on Pharmaceutical Care,” describes the mission of the pharmacist as the provider of pharmaceutical care, and emphasizes empathy and personal concern for the well-being of the patient.23 These concepts relate directly to two fundamentals of self-authorship: the development of mature relationships and the consideration of multiple perspectives. The third article, the American College of Clinical Pharmacy’s “The Definition of Clinical Pharmacy,” again describes the role of the pharmacist as being a provider of patient care and a member of the healthcare team, one who practices in collaboration with others, promoting cognitive maturity and the development of mature relationships.24

Students then participated in a two-hour preceptor-guided discussion to critically evaluate and discuss the meaning, validity, and applicability of concepts presented by the authority. During the discussion, the preceptor challenged students to rationalize and defend their positions on the validity of the authority statements, to offer examples of their personal experiences that supported their respective positions, and to play the role of “devil’s advocate,” offering counter examples and arguments from other perspectives. After the completion of the discussion, students were to continue to evaluate the authority statements of professionalism made in the articles and apply the principles with which they agreed to their professional practice.

The assigned reading and group discussion met each of the LPM core requirements (Figure 2). By challenging students’ responses and rationales with alternate viewpoints on a given scenario, the preceptor demonstrated how knowledge is complex and situational (requirement 1). When students shared their own examples with each other, those experiences became the foundations of their learning, validating their own ability to create knowledge (requirement 2). By describing and debating the concepts set forth by authority (statements in articles), the students considered each other’s experiences and learned collaboratively with their preceptor and peers (requirement 3).

At the end of the six-week APPE, each student composed a 1,000 word reflective essay in response to a writing prompt instructing students to reflect on how the three articles discussed during phase 1 and their rotation experiences influenced their understanding of pharmacy professionalism and development of their unique professional identity. The writing prompt also asked students to identify areas for improvement and to set goals for their future growth and professional practice.

EVALUATION AND ASSESSMENT

This qualitative study was guided by the following primary research question: To what extent did culminating reflective essays of APPE students on a faculty-precepted internal medicine rotation grounded in Baxter-Magolda’s self-authorship framework reveal professional identity formation (eg, adoption of professionalism attributes)? Each author’s institutional review board reviewed and determined the study to be exempt.

All students enrolled in this APPE between fall 2011and spring 2014 completed a single reflective narrative essay of at least 1,000 words in response to a structured prompt as part of the culminating course requirements. Each essay was deidentified and a copy was retained as a separate document prior to entering the essay into the research set.

Using an iterative and constant-comparative method, thematic analysis was conducted to reveal emergent themes in pharmacy professionalism and professional identity formation. Categorical analysis was used to examine the domains and phases of self-authorship at which students seemed to be, based on their narrative essays.25 Additional analysis of themes and self-authorship domains and phases were completed to answer the two secondary research questions.

Both authors served as researchers for the study. Because one of the authors (J.J.) was the course faculty member and preceptor, access to rich contextual features such as knowledge of additional details through personal memories of the events described was possible. Thus, her involvement introduced potential researcher bias requiring oversight.. The other author (S.C.) had no involvement in the APPE or with any of the students; thus, providing a basis for managing researcher bias and maximizing accuracy in analysis and interpretation.

To answer the primary research question, both authors read all of the essays to identify obvious patterns in narrative texts that suggested possible themes. A discussion of observed patterns resulted in an initial list of potential emergent themes. Clarification of example texts and features for each potential theme was determined. Next, the authors each independently coded one of the essays and then met to further develop and calibrate their coding of text before proceeding with additional coding. Once calibration was achieved, they each completed initial coding for half of the remaining essays and then exchanged the coded essays for crosschecking for accuracy and representativeness. The authors continued to meet to discuss and challenge each other’s findings until consensus was achieved. The process was repeated to identify any other potential themes until no other themes were evident. A third iteration and round of discussion was completed to finalize themes with corresponding coded text to achieve the most representative and parsimonious interpretation of the data, and a descriptive label was developed for each theme. The process was then repeated to identify and reach consensus on the predominant domain and phase of Baxter-Magolda’s self-authorship framework17 represented in each essay. Finally, the themes and status of self-authorship within each essay were examined to answer the two secondary research questions.

Forty-one essays were available from the APPE rotations (fall 2011 through spring 2014) and all were useable to answer the research question. Analysis revealed nine themes pertaining to PIF in terms of adopting specific attributes of pharmacy professionalism. A description of each theme follows and representative quotes are provided in Appendix 1. The themes are organized here for clarity, and the order in which they are presented does not reflect strength or priority.

For “personal definitions of professionalism,” students described professionalism as a lifestyle, with a sense of self-regulated responsibility. They wrote about feelings of pride and belongingness in the profession, and described how professionalism is not only about appearance or behavior, but also encompasses mindset, intention, and actions towards others.

When identifying “attributes of a professional,” students identified and defined professional traits and characteristics most important to them, and justified the need for these characteristics in professional practice. The most commonly listed attributes were integrity, respect for others, and altruism. Students described how these characteristics were the foundations of building trusting relationships with patients and providers that allow pharmacists to accomplish desired improvements in patient care. Additionally, students often described the need for confidence, which also generates trust in oneself and solicits trust from others.

Different than the previous category, for “witnessing and demonstrating professionalism,” students described real-life situations, personal observations, and/or direct experiences in which they witnessed demonstrations of professionalism by others. In essays that included such experiences, significant insights about professional identity were often described.

While “developing professional identity,” students described the various sources and means through which they learned about professionalism, including authority sources (parents, professors, and textbooks) and personal experiences. Consistently, students said they learned about professional traits in a classroom, but did not really understand or appreciate how they applied to self and others until they encountered them in real-life situations. Coded text corresponding to this theme also reflected connection between professionalism attributes and professional identity (eg, how “looking the part” influences perceptions of others regarding credibility and competence).

For “role of pharmacy knowledge and skills in professional identity,” students wrote about how acquiring knowledge and skills played an important role in building their self-confidence and developing trusting relationships with patients and providers. Students recognized their knowledge deficits and were inspired to commit to a lifelong quest for knowledge acquisition. In essays coded for this theme, students described accepting personal responsibility for developing knowledge and competence in critical appraisal.

Students identified empathy, compassion, and recognition of the value of each individual as vital to establishing a trusting “patient-centered relationship.” This trust was described as necessary for patients to follow recommendations and achieve positive outcomes. In essays for which coded text clearly reflected this theme, the student author’s frame of reference was those for whom they provided care, rather than on self or authority figures.

Students recognized the importance of their “role on the interprofessional team” and demonstrated appreciation for the contributions and perspectives of each professional on the healthcare team. Students recognized the unique role of the pharmacist as a medication expert and strove to develop the professional traits necessary to enact their role, such as communication skills and of course, pharmacotherapy knowledge.

Students described the kinds of provocative experiences that aided in “becoming a pharmacist” and their transition from student to professional. Students were both intimidated and excited by thoughts of their imminent graduation and the associated increase in professional responsibility. They wrote about the need for commitment to lifelong learning and continuous professional development.

Students recognized the “role of the assignment” and described the impact of the articles and their APPE experiences and assignments. Students recognized the need to teach principles of professionalism in classroom settings, and the value of practice experiences in helping to facilitate those externally defined principles in becoming internally defined practices.

To also answer the research question, analysis identified essays that demonstrated each of Baxter-Magolda’s four phases of self-authorship (Figure 1). Analysis of the student essays also revealed provocative experiences that represented the students’ transition between phases of self-authorship, thus demonstrating the intended purpose of the LPM. The following paragraphs describe results that reflect the developmental process of PIF and Baxter-Magolda’s phases of self-authorship and how experiences prompted transitional professional development. Representative quotes are provided in Appendix 2.

Some student essays most strongly exhibited characteristics of phase 1, Following Formulas. These students generally focused the majority of their essay on either summarizing authority articles from Part 1 of the assignment, or paraphrasing lessons learned from authority figures in their personal and professional lives. These essays displayed little evidence of reflection or introspection by the student. Students in phase 1 perceived knowledge as static, defined themselves through the expectations of others, and sought approval from authority figures in professional development and relationship-building.

The majority of student essays represented self-authorship in either phase 2, The Crossroads or phase 3, Becoming Self-Authored. In phase 2, students begin to see the need for internal definitions of belief, identity, and relationships. They begin to question the role of the authority in determining their priorities and beliefs and begin to establish their own vision for professional identity. They often criticize or critique the actions of the authority figures in their lives. Students may be internally developing a plan for how they will someday engage in professionalism, but they have not yet acted on their plan.

In phase 3, students begin to act on their internally defined and contextual knowledge, identity, and relationships, and understand the contextual nature of knowledge; and they are able to see multiple perspectives on belief and action. They begin to interpret statements from authority in the context of their own internal identity and choose how and when to apply traits in their own PIF.

Rarely, student essays revealed evidence of having achieved the final phase of self-authorship development, phase 4, Internal Foundations. In this phase, individuals have a fully grounded sense of self and identity that guides their actions and priorities. Students are easily able to recognize and value individual perspectives, and are able to critically evaluate multiple perspectives in decision-making to participate in active knowledge construction with peers. Essays written by students who were approaching or had reached this final phase of development demonstrated a significant reflective focus on team-based patient care and the need for continuous professional development beyond knowledge acquisition. In essays that reflected phase 4, students recognized that knowledge was more akin to a skill that is applied situationally through a process of critical evaluation.

DISCUSSION

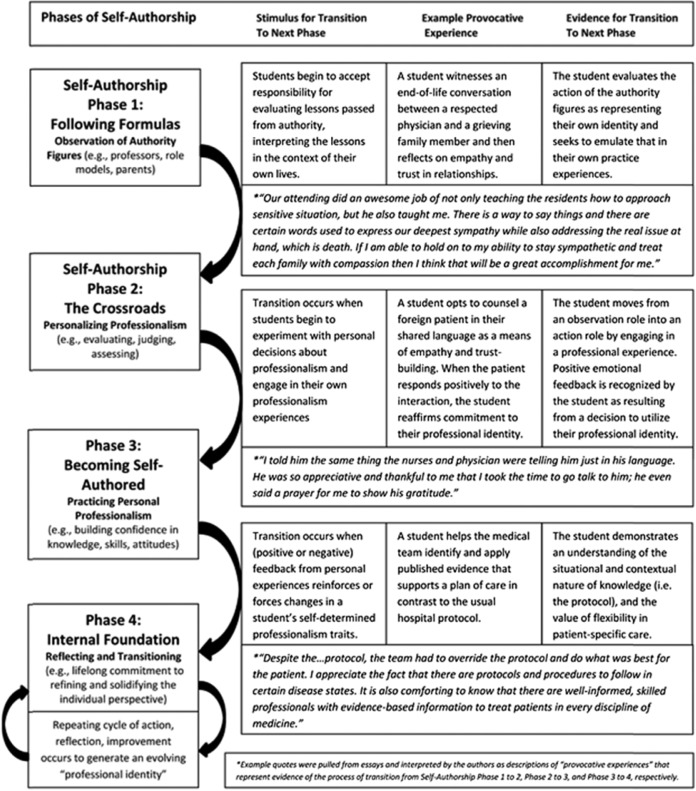

This study was conducted in an APPE that used the LPM to generate provocative experiences and promote students’ self-authorship development and PIF. The multipart learning experience culminated in the students’ creation of a written reflection describing their own concepts of professional identity. Analysis of these essays facilitated the development of an interpretive framework (Figure 3) that can be used to understand and purposefully facilitate PIF and self-authorship development. As shown in Figure 3, transition between self-authorship phases is stimulated by provocative experiences. Pharmacy faculty members can use this framework to generate provocative experiences that meet the core requirements of the LPM (Figure 2) and stimulate PIF through self-authorship development.

Figure 3.

Author’s Interpretive Framework for the Developmental Process of Professional Identity Formation and Self-authorship Progression.

One example of a provocative experience during an APPE was a student’s observation of an authority figure in an emotional or otherwise poignant situation, such as a code situation or end-of-life discussion (Figure 3). To meet the requirements of the LPM, however, the experience must include shared knowledge creation between peers, which can be achieved by a quick debriefing discussion with the student shortly after the event. When the faculty member engages with the student in an analysis of the authority figure’s actions during the situation, they are using the LPM to promote self-authorship development and PIF.

The nine themes that emerged from student essays revealed elements of professionalism and the process of PIF through adoption of professional attributes and Baxter-Magolda’s theory of self-authorship development. For example, student essays predominately coded with the theme “Attributes of a Professional” differed from essays predominately coded with the theme “Witnessing and Demonstrating Professionalism.” Students who wrote heavily about “Attributes of a Professional” tended to demonstrate reliance on authority for defining professional traits (phase 1), whereas students who described personal examples of “Witnessing and Demonstrating Professionalism” exhibited a mindset reflecting internal direction and included evidence of self-directed action (phases 2-4). Essays coded using the themes “The Patient-Centered Relationship” or “Role on the Interprofessional Team” also aligned with higher levels of self-authorship achievement, as students began to self-evaluate and demonstrate appreciation for the contributions of others to knowledge creation.

Essay analysis also identified evidence of provocative experiences that seem to have stimulated development across phases of self-authorship. For example, students who reflected on apparently provocative experiences in their essays seem to be describing how certain rotation experiences promoted development of internal guidance and PIF. Reflective writing served as an effective method for students to interpret and internalize explicit lessons learned from experiences in the context of PIF. These results provide initial evidence to support effective use of the LPM across all rotations for this APPE, thus supporting the potential for Baxter-Magolda’s self-authorship theory and the LPM for PIF in pharmacy students.

In a qualitative analysis of focus groups, Noble and colleagues found that pharmacy students at all levels struggled with professional identity formation, possibly because pharmacy students often enter the degree program with little understanding of the role of the pharmacist and the collective professional identity of the profession’s membership.26 Noble and colleagues identified many students who suggested that pharmacy was not their first career choice, and so students were not familiar with the history or goals of the profession prior to enrolling in a college of pharmacy. The authors suggest, as many others have, that students should begin a process of professional socialization and PIF as early in the curriculum as possible.

Other articles describing pharmacy faculty members’ charge to address professionalism in the curriculum suggest the following: faculty members and preceptors must demonstrate and model professionalism at all times, faculty members must set high standards and make expectations for professionalism explicit, and faculty members must hold students accountable for professional behavior.5,27,28 Students must feel able and empowered to recognize when a faculty member or preceptor is a poor example of professionalism, commit to internalizing and imitating good examples of professionalism, and make a personal, lifelong commitment to demonstrating professional values and behavior.5,27,28

While these published guidance statements5,27,28 offer some suggestions and advice, these papers do not discuss the nature of intentional interactions between faculty members and students, namely experiential education and the associated learning activities. Neither do these articles offer a pedagogical methodology for individual instructors to design appropriate activities and experiences to offer students an opportunity to learn and practice professionalism.

Evidence from our analysis of 41 reflective narrative essays suggests that use of the LPM to develop an APPE can guide self-authorship and PIF. The LPM associated with self-authorship theory offers a simple, three-step guideline to develop intentional learning experiences to provoke PIF and professionalism development (Figure 2). Continued exploration of self-authorship theory and the LPM may benefit pharmacy faculty members by providing an explicit pedagogical approach for developing learning experiences that promote self-authorship and PIF.

Inherent in qualitative research is the risk of investigator bias. In this study, one of the authors served as both the primary investigator and the APPE preceptor for the pharmacy students. This allows for the possibility that the investigator may have influenced the results by interpreting the data in the context of her own memories of the students or the events described in the reflections. The engagement of the other author (S.C.) as a co-investigator reduced the impact of such bias. In addition, the authors deidentified and randomized the order of the essays before analysis. The two authors met frequently to audit and crosscheck essays coded by one another for accuracy and representativeness. During analysis, only a small number of discrepancies occurred and these were resolved to consensus through discussion.

Limitations specific to this study include the use of a single essay per student, offering a snapshot view of students’ professionalism development. The quality and content of student essays were potentially influenced by students’ degree of prior experience with reflective writing, interpretation of the essay prompt, motivation and effort for the assignment, and their comfort level in revealing personal perspectives and insights to the preceptor. Each of these factors contributes to the potential for essays to be an inaccurate representation of their actual PIF and self-authorship phase.

The alternative approach of direct observation over time would be a more accurate representation of students’ developmental level. Future efforts to study PIF and self-authorship in pharmacy students might employ some combination of pre- and post-APPE essays, structured interviews, and field observations over time.

SUMMARY

This qualitative study provided evidence of the utility of Baxter-Magolda’s self-authorship theory and the LPM for facilitating pharmacy students’ PIF. Results contributed to the development of an interpretive framework that can be used by faculty members to generate provocative experiences that facilitate PIF. The purposeful and combined use of Baxter-Magolda’s self-authorship framework (Figure 1), the LPM (Figure 2), and the author’s interpretive framework (Figure 3) may be used by pharmacy faculty members to deliberately and effectively facilitate the process of PIF in pharmacy students.

Appendix 1. Pharmacy Student Quotes That Reflect The Nine Thematic Areas of Professional Identity Formation.

Personal Definitions of Professionalism

“My definition of professionalism is a state of mind, knowing and doing things that set me apart from others. It determines how I look, behave, think and act. It brings together what I as a person think is valuable, how I treat others, and the way I contribute to the workplace.”

Attributes of a Professional

“The idea of altruism in pharmacy is in my opinion the most correlative factor of the type of pharmacist I will one day become. In the field of healthcare as a whole, we are often judged by our willingness to take on difficult situations in order to better our patient’s outcomes and overall care.”

Witnessing and Demonstrating Professionalism

“Our decision to target areas most affected by heath disparities for our health fairs exhibited a lot of altruism. Sure there would be greater numbers (and comfort) in the [relative safety] of a community above the poverty line, but there would be a much greater impact in a community significantly and consistently below the poverty line.”

Developing Professional Identity

“I realized how much they [medical team members] listened and believed in everything I told them. This experience made me realize that a lot of people look up to pharmacy, so it is very important to be very professional in everything you do.”

“I honestly have always wondered the significance of having to dress up because I've always thought that what you look like shouldn't matter. I now realize how wrong my idea was because I have realized that I am better respected and heard when I look the part. I have noticed that I, too, pay more attention to and respect professionals that look the part.”

Role of Pharmacy Knowledge and Skills in Professional Identity

“Up until recently, I had only read review articles about medications. I have discovered that I need to read everything for myself without being told from review articles what it is. Evidence-based medicine is just that, however, I must be able to interpret it for myself. Knowing this has helped me re-evaluate all the stories that I have taken for facts without doing my own research and what disservices I could have done to my future patients.”

The Patient-Centered Relationship

“I think that one of the great aspects of pharmaceutical care is that it allows us to think of patients as people that depend on us to care for them in the best way possible. As a pharmacist-to-be, it would be important for me to treat each patient differently and focus my practice at targeting patient-specific outcomes that I can have an impact on in order to establish trust between myself and the patients that I will serve.”

Role on the Interprofessional Team

“You have to be able to work with others…The primary physician’s knowledge is not the only source of information being use to help these patients. It comes from the collective thoughts of the residents diagnosing the patients, nurses monitoring them, and pharmacists double checking pharmacotherapy chosen by the physicians for patient treatment. The combined knowledge of the team is important for an optimal outcome of the patients. You have to be willing and able to communicate with others to solve problems that present from a patient.”

Becoming a Pharmacist

“It was at that moment that I realized that my goal in life was not to see how quick I could recall information, but rather how I could use the knowledge I had to help save a life. Also, she reminded me that I will never stop learning. There will always be a drug to be designed, an article to be reviewed, and a miracle to be witnessed and if I want to continue being a key health care provider for my patients, my quest for knowledge will never end.”

Role of the Assignment

“The three articles and my experiences on rotation have strengthened my foundation and put me closer to being in a position to contribute to fulfillment of the mission of Xavier University. Altruism, integrity, accountability, and compassion are some of the qualities that have shaped and will continue to shape my professional identity post-graduation so that I may do my part in the promotion of a more just and humane society.”

Appendix 2. Pharmacy Student Quotes That Reflect The Developmental Process of PIF and Baxter-Magolda’s Phases of Self-authorship.

Phase 1: Following Formulas

“I feel that the articles were very influential in helping to shape my professional attitude. They showed me what types of characteristics were good to have and that allowed me to try and exhibit them during rotations and for future references. I knew most of them already, but to see them laid out and discussed let me see exactly how I can incorporate them.”

“I admire the effort they [my parents] have gone through in order to provide us with the best environment to grow in. Thus, I want to prove to my parents that their hard work will eventually pay off through my effort to become a pharmacist.”

Phase 2: The Crossroads or Phase 3: Becoming Self-Authored

“Even though I will be working in a retail setting, I would like to move beyond the traditional role of simply dispensing medication and deal with patients more directly and at a personal level… I will dedicate myself to providing individualized services to patients.”

“My education and values have taught me to listen first to the patients. Sometimes, they want to be heard and part of the regimen for their care. I need to establish a relationship where mutual respect can exist between the both of us. After all, the goal is to provide the patient with care that improves his or her quality of life.”

Phase 3: Becoming Self-Authored

“The ACCP student commentary says, ‘In all professional environments, students must dress and carry themselves in a way that will instill confidence and trust with patients and health care colleagues.’ I have always questioned many societal expectations and standards and a lot of these expectations do not make logical sense to me. I don’t like the idea of conforming to fit the standards of others, but I have learned that it is sometimes best to do so to a certain extent. Whether we are aware of it or not we are constantly judging people around us and they are constantly judging us. If you are not neatly dressed or well maintained, it will negatively affect other’s perception of you as a professional and may end up making you a less effective practitioner.”

Phase 4: Internal Foundations

“A practicing pharmacist shares responsibility with other healthcare providers and patients to achieve a desired therapeutic outcome aimed at benefiting the patient. I believe that personally accepting responsibility for a patient’s outcome is important because it enables us to truly be engaged in any decision that could ultimately harm or benefit the patient. If patients can trust my judgement and I can respect their opinions and concerns regarding their care, we can achieve positive outcomes more frequently.”

REFERENCES

- 1.Scott J, Bell H, Welch B, et al. American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy Council of Deans Taskforce on Professional Identity Formation – Final Report. http://www.aacp.org/governance/councildeans/Documents/COD%20Taskforce%20on%20Professional%20Identity%20Formation%20Final%20Report%20July%202014.pdf. Accessed December 7, 2015.

- 2.Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education. Accreditation standards and key elements for the professional program in pharmacy leading to the doctor of pharmacy degree. https://www.acpe-accredit.org/pdf/Standards2016FINAL.pdf. Updated 2016.

- 3.Medina MS, Plaza CM, Stowe CD, et al. Center for the Advancement of Pharmacy Education 2013 educational outcomes. Am J Pharm Educ. 2013;77(8):162–162. doi: 10.5688/ajpe778162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Popovich NG, Hammer DP, Hansen DJ, et al. Report of the AACP professionalism task force, May 2011. Am J Pharm Educ. 2011;75(10):Article S4. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hill WT. American Pharmaceutical Association Academy of Students of Pharmacy-American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy Council of Deans Task Force on Professionalism. White paper on pharmacy student professionalism. J Am Pharm Assoc (Wash). 2000;40(1):96–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown D, Ferrill MJ. The taxonomy of professionalism: reframing the academic pursuit of professional development. Am J Pharm Educ. 2009;73(4):Article 68. doi: 10.5688/aj730468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kelley KA, Stanke LD, Rabi SM, Kuba SE, Janke KK. Cross-validation of an instrument for measuring professionalism behaviors. Am J Pharm Educ. 2011;75(9):Article 179. doi: 10.5688/ajpe759179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schafheutle EI, Hassell K, Ashcroft DM, Harrison S. Organizational philosophy as a new perspective on understanding the learning of professionalism. Am J Pharm Educ. 2013;77(10):Article 214. doi: 10.5688/ajpe7710214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cruess RL, Cruess SR. Teaching professionalism: general principles. Med Teach. 2006;28(3):205–208. doi: 10.1080/01421590600643653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peeters MJ, Stone GE. An instrument to objectively measure pharmacist professionalism as an outcome: a pilot study. Can J Hosp Pharm. 2009;62(3):209–216. doi: 10.4212/cjhp.v62i3.790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aguilar AE, Stupans L, Scutter S. Assessing students’ professionalism: considering professionalism's diverging definitions. Educ Health (Abingdon) 2011;24(3):599. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Poirier TI, Gupchup GV. Assessment of pharmacy student professionalism across a curriculum. Am J Pharm Educ. 2010;74(4):Article 62. doi: 10.5688/aj740462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rutter PM, Duncan G. Can professionalism be measured? Evidence from the pharmacy literature. Pharm Pract (Granada). 2010;8(1):18–28. doi: 10.4321/s1886-36552010000100002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schafheutle EI, Hassell K, Ashcroft DM, Hall J, Harrison S. How do pharmacy students learn professionalism? Int J Pharm Pract. 2012;20(2):118–128. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7174.2011.00166.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnson JL. Self-authorship in pharmacy education. Am J Pharm Educ. 2013;77(4):Article 69. doi: 10.5688/ajpe77469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baxter Magolda MB. Developing self-authorship in young adult life. J Coll Stud Dev. 1998;39(2):143–156. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baxter Magolda MB. Three elements of self-authorship. J Coll Stud Dev. 2008;49(4):269–284. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baxter Magolda MB, King P, editors. Learning Partnerships: Theories and Models of Practice to Educate for Self-Authorship. Sterling, VA: Stylus Publishing; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zlatic TD. Writing to learn in pharmacy education. In: Re-visioning Professional Education: An Orientation to Teaching. Lenexa, KS: American College of Clinical Pharmacy; 2005:107–131.

- 20. Zlatic TD. Re-affirming the human nature of professionalism. In: Zlatic TD, ed. Clinical Faculty Survival Guide. Lenexa, KS: American College of Clinical Pharmacy; 2010:3–20.

- 21.Tsingos C, Bosnic-Anticevich S, Smith L. Reflective practice and its implications for pharmacy education. Am J Pharm Educ. 2014;78(1):Article 18. doi: 10.5688/ajpe78118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Holt SL, Lau MS, Wong FL, et al. Tenets of professionalism for pharmacy students. Pharmacother. 2009;29(6):757–759. doi: 10.1592/phco.29.6.757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.American Society of Hospital Pharmacists. ASHP statement on pharmaceutical care. Am J Hosp Pharm. 1993;50:1720–1723. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.American College of Clinical Pharmacy. The definition of clinical pharmacy. Pharmacother. 2008;28(6):816–817. doi: 10.1592/phco.28.6.816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Merriam SB. Qualitative Research: A Guide to Design and Implementation. 3rd ed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Noble C, O’Brien M, Coombes I, Shaw PN, Nissen L, Clavarino A. Becoming a pharmacist: students’ perceptions of their curricular experience and professional identity formation. Curr Pharm Teach Learn. 2014;6(3):327–339. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hammer D. Improving student professionalism during experiential learning. Am J Pharm Educ. 2006;70(3):Article 59. doi: 10.5688/aj700359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.American College of Clinical Pharmacy. Roth MT, Zlatic TD. Development of student professionalism. Pharmacother. 2009;29(6):749–756. doi: 10.1592/phco.29.6.749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]