SUMMARY

Animal development is characterized by signaling events that occur at precise locations and times within the embryo, yet determining when and where such precision is needed for proper embryogenesis has been a longstanding challenge. Here we address this question for Erk signaling, a key developmental patterning cue. We describe an optogenetic system for activating Erk with high spatiotemporal precision in vivo. Implementing this system in Drosophila, we find that embryogenesis is remarkably robust to ectopic Erk signaling, except from 1 to 4 hours post fertilization when perturbing the spatial extent of Erk pathway activation leads to dramatic disruptions of patterning and morphogenesis. Later in development, the effects of ectopic signaling are buffered, at least in part by combinatorial mechanisms. Our approach can be used to systematically probe the differential contributions of the Erk pathway and concurrent signals, leading to a more quantitative understanding of developmental signaling.

Keywords: Optogenetics, MAP kinase, embryogenesis, Drosophila, signal transduction

Graphical abstract

INTRODUCTION

The highly conserved Extracellular Signal Regulated Kinase (Erk) controls tissue patterning and morphogenesis in developing organisms from flatworms to humans (Umesono, et al., 2013; Corson, et al., 2003; Gabay, et al., 1997a). It is most commonly activated by locally-produced growth factors that establish elaborate patterns of signaling, thereby providing spatiotemporal control of cell responses. Studies in model organisms using gain-of-function (GOF) pathway mutations have established that aberrantly increasing Erk activity during development can result in improperly formed and malfunctioning structures (Brunner, et al., 1994; Klingler, et al., 1988). Consistent with these observations in the laboratory, deregulated Erk activation resulting from activating mutations in the Erk pathway has been associated with a large class of developmental abnormalities in humans (Jindal, et al., 2015; Rauen, 2013). The structural and functional phenotypes observed in affected individuals include congenital heart defects and delayed growth and are believed to result from Erk signaling events that may be too strong, too long, or not sufficiently restricted in space. All of this leads to questions about the sensitivity of the Erk-dependent developmental processes to quantitative changes in Erk activation.

What are the upper limits of signal dose, domain, and duration? Current approaches to addressing these questions rely on genetic perturbations, such as targeted expression systems and conditional mutants, which can augment endogenous signaling patterns. Yet most of these approaches have limited precision and dynamic range, making it difficult or impossible to independently perturb the timing, location, and level of a developmental signal. Here we demonstrate that the power of experimental approaches aimed at addressing this important problem can be significantly increased by optogenetic control. We have developed a versatile approach for perturbing Erk activity in developing organisms and implemented it in the early Drosophila embryo, the model organism that provided the first view of Erk dynamics in developing tissues (Gabay, et al., 1997a; Gabay, et al., 1997b) and continues to provide insights into the quantitative control of the Erk pathway. Our findings reveal that the consequences of increasing Erk signaling are very different depending on whether the intensity, location or timing of Erk signaling is perturbed. These results help to explain how even the globally-activating mutations associated with Erk-related developmental defects lead to highly tissue-specific effects.

RESULTS

Developing tunable optogenetic control of the Ras/Erk pathway in vivo

Our strategy for spatiotemporal control of developmental Erk signaling is based on inducing the membrane translocation of a Ras activator, SOS, to the plasma membrane with light. Our first efforts to control Erk activity in vivo were based on the Phy/PIF approach we previously developed in mammalian cells (Toettcher, et al., 2013). Although both the Phy and PIF components were expressed in vivo (see Figure S1A), recruitment was poor and our efforts were limited by the challenge of injecting phycocyanbilin (PCB) into embryos, which presented a significant experimental burden (Figure S1B). We therefore pursued an alternative strategy based on a blue light-responsive heterodimerization pair, the iLID/SSPB system, forming the basis of the rest of the current study (Guntas, et al., 2015).

This OptoSOS system consists of two components: a light-switchable membrane anchor (iLID-CAAX) and a fluorescent Ras activator (tRFP-SSPB-SOScat) that is relocalized to the membrane after light stimulation. Both components are expressed from a single construct using a P2A cleavable peptide to generate two protein products from a single transcript (Figure 1A) (Daniels, et al., 2014). Because the cleavage of P2A sequences operates with high efficiency in many cellular contexts (Kim, et al., 2011), this single-vector strategy is likely to be highly generalizable to other organisms. After verifying that light-induced Erk phosphorylation reached levels comparable to those observed with constitutively active Erk pathway mutations in Drosophila S2 cells (see Figure S1), we used the Gal4-UAS system to uniformly express both OptoSOS components in the early embryo (Duffy, 2002; Hunter and Wieschaus, 2000).

Figure 1. Light-mediated activation of signaling pathways in vivo.

(A) Schematic of optogenetic control of Erk signaling. An upstream activation sequence drives tissue-specific expression of both optogenetic components, tRFP-SSPB-SOScat and iLID-CAAX, which are cleaved by a P2A sequence into separate peptides. Recruiting SOScat to the membrane with light activates the Ras/Erk cascade. (B) Quantification of membrane SOScat recruitment over time for varying light intensities. (C) Local illumination (left panel) can be used to generate spatially precise patterns of membrane SOScat recruitment (middle and right panels). See also Figure S1.

An ideal optogenetic tool for probing developmental signaling should be fast, spatially precise, and usable with a minimum of specialized reagents and equipment. We found that iLID-based control in Drosophila meets all these criteria. Upon light stimulation SOScat relocalized from the cytoplasm to membrane in less than 1 min, an effect that was completely reversed in the dark within 2 min and could be quantitatively varied by tuning the light intensity (Figure 1B; see also Movie S1). By applying spatially restricted patterns of light, we were also able to control SOScat recruitment with subcellular resolution (Figure 1C; see also Movie S2). In contrast to other recent approaches (Buckley, et al., 2016; Guglielmi, et al., 2015), precise spatiotemporal control could be achieved without externally supplied chemical cofactors and required relatively conventional imaging equipment (i.e. single-photon excitation using either a 488 nm laser or blue LEDs).

Light-activated Ras triggers high Erk activity and hallmark transcriptional responses

In early embryos, the endogenous pattern of Erk activity is established by the localized activation of Torso, a uniformly-expressed receptor tyrosine kinase. This pattern is essential for the localized expression of several zygotic genes, including tailless (tll), which plays a key role in specifying the structures at the embryonic termini (Pignoni, et al., 1990). Prior genetic studies demonstrated that this expansion of Erk signaling has severe consequences for the embryo; GOF mutations in the Torso pathway lead to complete lethality and loss of body segmentation, effects that can be rescued by hypomorphic alleles of Erk or tll (Brunner, et al., 1994; Klingler, et al., 1988). Importantly, even in these GOF mutants, Erk is not activated to a uniform extent across the embryo. In the middle of the embryo, Erk activity reaches only 40% of the maximum level seen in wild-type embryos and signaling at the termini is not increased compared to wild-type (Grimm, et al., 2012). Accordingly, tll expression in these mutants is partially extended from the poles but does not reach the middle of the embryo (Figure S2A). These limitations have made it impossible to assess how different regions of the embryo interpret the same increased dose of Erk activation.

In contrast to prior GOF mutations, acute light stimulation induces high, spatially uniform Erk activation and downstream gene induction (Figure 2A; see also Figure S2). Quantification across multiple similarly staged embryos revealed that the level of active, doubly-phosphorylated Erk (dpErk) is at least two-fold higher than the maximum level seen in wild-type embryos, whereas dpErk levels in dark conditions were similar to wild-type (Figure 2B). Light-induced Erk was also fully competent to induce transcriptional responses, and expanded the domain of tll expression across more than 80% the embryo, connecting the tll bands that are normally present at the anterior and posterior ends (Figure 2C).

Figure 2. Light stimulation induces global Erk activity and downstream gene expression.

(A) Comparison of Erk activity in wild-type, unstimulated and light-stimulated OptoSOS embryos at nuclear cycle 14. Embryos were stained for dpErk (red) and DAPI (white). (B) Quantification of dpErk levels from embryos stimulated as in panel a (mean +/− SEM). (C) Fluorescence in situ hybridization for tailless (til) in wild-type or light-simulated OptoSOS embryos at nuclear cycle 14. (D) dpErk activation in 12 hour old OptoSOS embryos stimulated for 1 h with light, compared with similar age wild-type embryos. Scale bar is 100 urn in all panels. (E) Quantified dpErk intensity along line scans indicated by the dashed lines in (D). See Table S1 for numbers of embryos/replicates; see also Figure S2.

Even when maternally driven, the OptoSOS system can be used to induce Erk activity in both surface and internal tissues for at least 12 hours after fertilization, enabling us to perturb signaling through much of embryogenesis (Figure 2D; Figure S2D–F). However, in older embryos (5 to 12 h after fertilization) we observed that a uniformly increased dpErk field was superimposed upon the normal segmental pattern of Erk activity (Figure 2E; Figure S2D), suggesting that tissues either retain the ability to sense further increases in Ras signaling or become differentially responsive as they adopt specific cell fates. Nevertheless, even in 12 hour old OptoSOS embryos, the lowest level of dpErk between segments was two to three-fold higher than the maximum level observed in wild-type embryos (Figure 2E). Taken together, our results show that the OptoSOS system is highly active in vivo, generating more potent and controllable Erk activity than any known GOF pathway mutation.

Early embryogenesis is sensitive to the spatial distribution of Erk activity but not its dose

Developmental Erk signaling is tightly controlled from embryo to embryo, exhibiting highly reproducible profiles in intensity, spatial range, and duration (Lim, et al., 2015). Which of these three features are essential for development? We first focused on intensity, reasoning that if the precise level of Erk activity at the poles was read out by downstream processes, then perturbing that level should be deleterious to development. Such experiments were previously impossible, as no known pathway mutation is capable of generating increased dpErk at the poles.

We applied light to the anterior pole, posterior pole, or center of each embryo during the time at which Erk is normally activated at the termini (Figure 3A–B). Embryos stimulated with light only at the termini were viable, producing larvae, pupae and adult flies that were indistinguishable from wild-type or dark-incubated OptoSOS embryos (Figure S3A,B). Furthermore, despite strong light-induced Erk activity in pole cells (Figure S2), which are normally devoid of Erk activity at this point of embryogenesis, termini-illuminated flies were still fertile and have normal gonads (Figure S3B). In contrast, activating Erk in the middle of the embryo disrupted both the early steps of embryonic patterning and subsequent stages of embryogenesis, resulting in complete embryonic lethality similar to that obtained by GOF Torso signaling mutants (Klingler, et al., 1988). Strikingly, we found that even reducing ectopic activation to a narrow 40 µm strip delivered to the middle of the embryo, a region comprising about 3–5 cell diameters, induced high levels of embryonic lethality (Figure 3C).

Figure 3. Consequences of perturbing the level and location of Erk activity.

(A) Schematic of our setup where a digital micromirror device was used to apply spatially-patterned light to each embryo. (B) Lethality of local Erk activation from 1–3 hours post fertilization (mean + SD). Light was applied to ∼15% of the embryo at a pole, or the middle ∼45% of the embryo. The number of hatched larvae was counted. (C) Lethality after illuminating progressively decreasing stimulation areas in the middle of the embryo (mean + SD). (D) Cuticle phenotypes from GOF mutations in the Erk pathway (TorGOF and MekGOF). (E) Quantification of cuticle phenotypes from the experiment shown in (A). (F) Capicua staining in WT and OptoSOS embryos after 1 hr of illumination. (G) Quantification of Capicua staining as shown in (F) (mean +/− SEM). (H) Left panels: schematic of experiment: OptoSOS embryos were spatially illuminated during nuclear cycles 13–14, and observed through gastrulation. Right panels: still images of OptoSOS embryos exhibiting tissue contraction during gastrulation. See Table S1 for numbers of embryos/replicates; see also Figure S3.

To investigate this differential sensitivity in more detail we examined how different Erk patterns affected the formation of cuticle structures. Inappropriate Erk activity is known to interfere with cuticle formation and patterning, and strong GOF mutations in Torso signaling induce fusion of embryonic segments or lead to their loss in an Erk-dependent fashion (Figure 3D; see also Figure S3) (Urban, et al., 2004; Nussleinvolhard, et al., 1984). Consistent with this classic phenotype, the overwhelming majority of embryos illuminated in the center lacked segments, while the remainder exhibited pronounced fusions (Figure 3E). Spatially-restricted optogenetic stimulation thus revealed that two regions of the early embryo respond very differently to the same dose of additional Erk activity: the terminal regions (where Erk is normally active) are unaffected, but the middle of the embryo (where the Erk pathway is normally silent) is extremely sensitive.

Our findings can be interpreted in terms of the current model of Torso signaling, according to which Torso-dependent Erk activation controls gene expression by relieving transcriptional repression by Capicua (Cic), a DNA-binding factor that is uniformly expressed in the embryo in the absence of Torso signaling (Jimenez, et al., 2000). Downregulation of Cic at the poles is essential for the expression of genes like tll and differentiation into terminal structures such as the posterior midgut, which undergoes contraction and invagination at the onset of gastrulation. At the same time, Cic is needed in the middle of the embryo to play a role in the regulation of the segmentation cascade (Jimenez, et al., 2000). Accordingly, adding Erk signaling at the poles does not add much to the anti-repressive effect that is already provided by the endogenous localized activation of Torso, whereas increased Erk signaling (and thus removal of the Cic repressor) in the middle of the embryo has a major effect on the segmentation cascade and results in lethality. Indeed, measuring nuclear Cic levels in light-stimulated OptoSOS embryos revealed that nuclear Cic is reduced at all positions along the anterior-posterior (A-P) axis when compared to wild-type embryos (Figure 3F–G), consistent with Cic’s role as a target for Erk-mediated degradation.

To gain insight into the underlying developmental processes that are affected by ectopic Ras/Erk signaling, we performed time-lapse microscopy after local illumination in different regions of the embryo. In center-illuminated OptoSOS embryos but not wild-type embryos, we found that local illumination triggered pronounced tissue invagination at the locations where the light stimulus had previously been applied (Figure 3E; see also Movies S3–S4). We found that the domain of contraction scaled with the size of the light stimulus: a larger region of light stimulation led to large-scale contraction of the majority of the embryo, ejecting the yolk to the anterior side of the embryo (Figure 3E; see also Movie S5–S6). This contraction occurred during gastrulation at the same time as invagination of the posterior midgut, and could occur 30 minutes or more after light stimulation ceased. Our results thus demonstrate that light-activated Ras signaling locally drives the improper specification of contractile tissue, leading to defects in gastrulation that disrupt the normal course of morphogenesis.

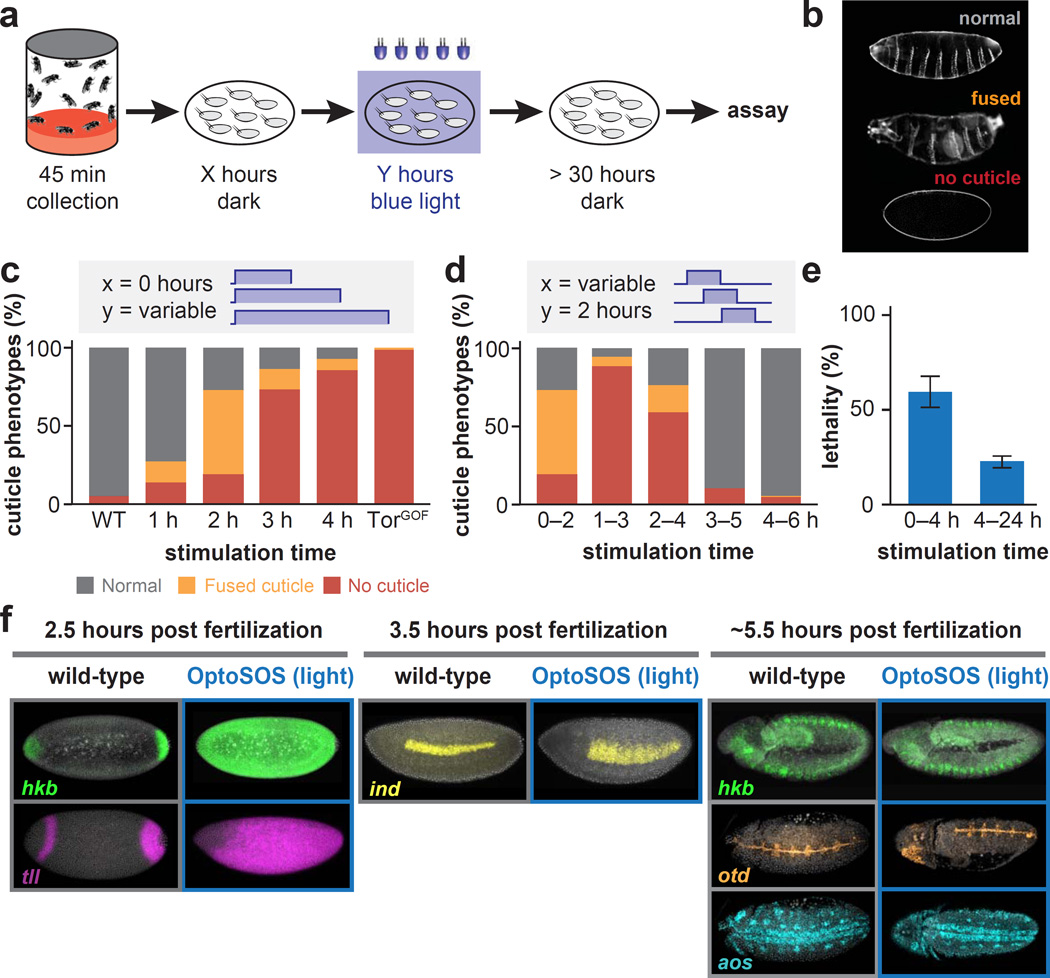

Embryonic sensitivity to ectopic Erk is limited to a narrow time window

We have shown that early embryogenesis is insensitive to increased Erk activity at the poles, and yet highly sensitive to Erk signaling in the middle of the embryo. Do other developmental stages have a similar Achilles’ heel? To address this question we applied uniform illumination to embryos at different times during development. After collecting freshly laid embryos over a 45 min window, we incubated the embryos in the dark for a specified amount of time (“X hours”), illuminated them for a fixed duration (“Y hours”) and returned them to the dark to complete embryogenesis (Figure 4A). As expected, global illumination of early embryos was lethal and led to segment fusion or loss (Figure 4B–C; see also Figure S4). Surprisingly, however, these phenotypes were limited to a brief time window. By 3 hours post fertilization, a global increase in Erk activation had no effect on segmentation and cuticle development (Figure 4D). We observed a similar decrease in overall lethality in late-illuminated embryos. Whereas only ∼40% of embryos survived global Erk activation induced by low-intensity blue light exposure during the first 4 hours of embryogenesis, ∼75% survived the same light stimulus applied during the rest of embryogenesis, from 4 hours post fertilization until hatching (Figure 4E; see also Figure S4C). We previously found that Erk phosphorylation was induced by light to similar levels above wild-type for at least 12 hours (Figure 2D–E; Figure S2E–F), suggesting that these results are not due to loss of expression of the maternally-driven OptoSOS system.

Figure 4. A temporal window of sensitivity to ectopic Erk activation.

(A) Embryos are collected for 45 minutes after which they are placed in the dark for X hours before being stimulated globally for Y hours under blue light. After allowing sufficient time to hatch, embryos are then assayed for lethality and segmentation defects. (B) Cuticle phenotypes obtained by varying light exposure duration and start time. (C-D) Quantification of cuticle defects varying light duration (C) or start time (D), compared to wild-type and a TorGOF mutant. (E) Lethality after stimulation with an intermediate light intensity from 0–4 hours after collection versus from 4 hours until hatching (mean +/− SEM). (F) Fluorescence in situ hybridization for hkb, tll, ind, otd , and aos at the indicated developmental stages for wild-type and light illuminated OptoSOS embryos. See Table S1 for numbers of embryos/replicates; see also Figure S4.

Why might spatial sensitivity be lost at later stages, where we observe that increasing Erk activity no longer has such severe consequences? In contrast to early development, the cells in later embryos have many concurrent sources of positional information – they may already have adopted a specific fate, may alter their sensitivity to signaling inputs by expressing positive or negative regulators, may have modified chromatin elements on target promoters, or multiple patterning cues may provide additional context (Lim, et al., 2015; Lander, 2007; Nguyen, et al., 1998). We therefore reasoned that in late embryogenesis, Erk target genes may be subject to combinatorial regulation by other input pathways, providing additional safeguards that cannot be overridden by ectopic Erk activation.

To test this model, we measured the expression domain of Erk-induced genes at different developmental stages: huckebein (hkb), intermediate neuroblasts defective (ind), orthodenticle (otd), and argos (aos). In each case, we compared wild-type embryos to blue light illuminated OptoSOS embryos, which globally activate Erk signaling. For those gene that are induced in 2.5–3 hour old embryos (tll and hkb), we observed a dramatic expansion after blue light stimulation (Figure 4F, left panel). In contrast, light stimulation of 5.5 hr old OptoSOS embryos induced gene expression that is indistinguishable from similarly aged wild-type embryos (hkb; otd in 11 of 12 embryos tested), or that is partially expanded (aos; otd in 1 of 12 embryos) (Figure 4F, right panel). Finally, for ind, an Erk target expressed at an intermediate time (3.5 hours), we observe an intermediate level of expansion (Figure 4F, middle panel). This pattern is consistent with known mechanisms of ind’s combinatorial control, including activation by Dorsal and repression by Vnd and Snail (Lim, et al., 2013). Our data thus support a model whereby Erk activity is initially sufficient to induce downstream gene expression at any embryonic position, but where combinations of positional cues or crosstalk from additional signaling pathways correct quantitative defects in Erk activity at subsequent developmental stages.

DISCUSSION

Twenty years ago, antibody staining revealed a highly dynamic atlas of Erk activation during Drosophila embryogenesis (Gabay, et al., 1997a; Gabay, et al., 1997b). Here, we use an optogenetic approach to examine the consequences of perturbing this atlas at different times and spatial locations. We find that throughout embryogenesis, proper development is remarkably robust to perturbations in the level of Erk activity. In contrast, early embryos are extremely sensitive to the location of Erk activity; even a narrow strip of ectopic Erk activity is sufficient to completely halt normal developmental progress. The results we describe are unlike what would be predicted for classical morphogens, where different genes are thought to be induced at various concentrations of a diffusible factor. Our data is more consistent with Erk activation in the early embryo behaving like a switch, where input levels are unimportant as long as they are above a triggering threshold (Ferrell and Machleder, 1998).

Importantly, our ability to characterize the consequences of increased Erk signaling was only possible because optogenetic stimulation generates such potent, uniform Erk activity in the early embryo (Figure 2A–B). This finding was unanticipated and contrasts with results from constitutively active Erk pathway mutations that have been previously studied in the early Drosophila embryo (Grimm, et al., 2012), which neither increased Erk activity at the embryo termini, nor induced Erk activity in the middle of the embryo to high, termini-like levels. This difference may be due to the different timescales of action between light stimulation and genetic perturbation. Long-term activation may desensitize a signaling pathway like Ras/Erk over time, an effect which may be bypassed by acute stimulation (Hoeller, et al., 2016). Optogenetic stimulation may thus serve as a powerful tool even for pathways that have been intensely studied using GOF signaling mutations, potentially revealing new activity states and modes of regulation.

The sensitivity differences we observe between early and late embryos do not arise because Erk signaling is less critical in later development. Indeed, prior loss-of-function studies demonstrated that eliminating Erk patterns at these stages is both lethal and prevents cuticle formation (Klambt, et al., 1992; Price, et al., 1989; Schejter and Shilo, 1989). Yet our results suggest that the consequences of hyperactive Erk signaling may be more complex than might have been expected from prior genetic studies. For instance, during tracheal development, hyperactivation of the Drosophila FGFR homolog Btl in tracheal cells stalls migration and tracheal development (Gabay, et al., 1997b; Sutherland, et al., 1996). In contrast, we found that OptoSOS larvae that hatch after illumination from 4–24h of embryogenesis showed no gross defects in tracheal development (Figure S4E). Similarly, the expression patterns of aos and otd are strongly expanded in the presence of the constitutively active EGF ligand s-spitz (Schweitzer, et al., 1995) but are less perturbed by illumination in OptoSOS embryos (Figure 4F). These differences may point to a hitherto-unappreciated role for other pathways that are activated at the receptor level but not by Ras (Toettcher, et al., 2013), such as phosphoinositide-dependent signaling, which has recently been implicated in tracheal development (Ghabrial, et al., 2011). Alternatively, target gene expression may respond to a feature of Erk activity other than its absolute level. We observed that globally-illuminated OptoSOS embryos still exhibited spatial patterns of Erk activity on top of an elevated background (Figure 2E); these patterns may thus still preserve information about the appropriate range for downstream gene expression. Dissecting the mechanisms with which Erk activity is decoded by downstream genes in the developing embryo will be an important challenge for future studies.

Our data suggests that the consequences of Erk hyperactivation are tissue- and stage-specific, an observation that closely resembles what is observed in human developmental disorders caused by GOF mutations in the Erk pathway. Even uniformly-expressed mutant alleles only lead to certain defects in highly specialized tissues (Gelb and Tartaglia, 2011; Pagani, et al., 2009), suggesting that many Erk-dependent signaling events may be similarly buffered in vertebrate development. In future work, cellular optogenetics could be useful for revealing the details of this buffering logic by directly setting the activity state of specific input pathways and monitoring the resulting transcriptional responses. Such approaches highlight the potential for optogenetics to reveal how inductive signals are interpreted in space and time.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Plasmids

The tRFP-SSPB-SOScat-P2A-iLID-CAAX expression cassette was first assembled using a PUWR backbone (Drosophila Genome Resource Center, #1281) as transfer vector. The tRFP-SSPB fragment was derived from pLL7.0: tgRFPt-SSPB WT (a gift from Brian Kuhlman, Addgene plasmid #60415). The SOScat fragment was derived from pHR-YFP-PIF-SOScat (Addgene plasmid #50851). The iLID-CAAX sequence was derived from pLL7.0: Venus-iLID-CAAX (a gift from Brian Kuhlman, Addgene plasmid #60411). All fragments were ligated and transferred to the pTIGER vector (Ferguson, et al., 2012) using In-Fusion assembly (Clontech).

Fly procedures

Generation of transgenic flies and stocks: constructs described in ‘plasmids’ section were integrated into the 3rd chromosome using the фC31-based integration system (Bischof, et al., 2007), at the Attp site estimated to be at 68A4. OregonR , Histone-GFP, TorD4021/+ alleles were also used in the experiments. P(matα-GAL-VP16)mat67; P(matα-GAL-VP16)mat15 was used to drive iLIDnano expression in the early embryo (Hunter and Wieschaus, 2000). Flies were raised under standard conditions and crosses were performed at 25°C unless otherwise specified.

Immunostaining and fluorescent in situ hybridization

Rabbit anti-dpErk (1:100; Cell Signaling), sheep anti-GFP (1:1000, Bio-Rad), sheep anti-digoxigenin (DIG) (1:125; Roche), and mouse anti-biotin (1:125; Jackson Immunoresearch), rat anti-mCherry (1:1000; Life Technologies) and rat anti HA (1:100, Roche # 11-867-423-001) were used as primary antibodies. DAPI (1:10,000; Vector laboratories) was used to stain for nuclei, and Alexa Fluor conjugates (1:500; Invitrogen) were used as secondary antibodies. Fluorescent imaging was done with a Nikon A1-RS scanning confocal microscope with a 20x objective. For pairwise comparisons of wild type and mutant backgrounds, embryos were collected, stained, and imaged together under the same experimental conditions. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean of embryo ages (x-axis) and normalized dpErk intensities (y-axis).

Cuticle preparation

Embryos were dechorionated after being aged for more than 30 hours. Dechorionated embryos were incubated overnight in a media containing lactic acid and Hoyer’s medium (1:1) at 65C. Cuticle imaging was performed with Nikon Eclipse Ni at 10X objective.

Microscopy

For Figure 1 and Figure S2C, bright-field and confocal microscopy was performed on a Nikon Eclipse Ti spinning disk confocal microscope (see Supplementary Methods for details). For translocation experiments embryos were dechorionated in 50% bleach for 2 minutes and rinsed in water before mounting and imaging at 40x. Microscopy of fixed samples in figure 2 was performed using a Nikon A1 RS point-scanning confocal microscope (Princeton microscopy core). For cuticle staining, dark-field images were collected on a Nikon Eclipse Ni.

For the patterned illumination experiments in Figure 3 and Movie S3, embryos were collected for 45 minutes, aligned on coverslip in a 3:1 mix of halocarbon 700/27 oil. The slide was then sandwiched with a Teflon window chamber using vacuum grease (a technique described in detail in (Kiehart, et al., 1994)). Patterned optogenetic illumination was performed using a Mightex Polygon digital micromirror device using an X-Cite XLED 450 nm blue light source. 450 nm light was applied at 40% power for 100 msec to each embryo at 20x. All embryos were illuminated once every 40 sec starting 30 minutes after collection – at this imaging frequency, up to 30 embryos could be illuminated per experiment. Just before stimulation, DIC images of each embryo were collected with a 650 nm long-pass filter (Chroma) in the light path to prevent any light-induced SOScat activation. Embryos which were in late NC 14 or older were excluded from counts.

Temporal activation experiments

Embryos were collected for 45 minutes at 25 °C before being were then wrapped in foil and aged at room temperature for ‘X’ hours before stimulation (where ‘x’ is defined for specific experiments in the corresponding text and figure). They were then placed in blue LED containing foil wrapped boxes and stimulated for ‘Y’ hours before returning to the dark for 30+ hours (where ‘y’ is defined for specific experiments in the corresponding text and figure). To achieve lower activation levels the LEDs were toggled on for one second pulses at regular intervals using an Arduino microcontroller. Lethality was calculated by counting unhatched and empty eggshell cases on a random region of each plate.

Supplementary Material

HIGHLIGHTS.

Optogenetic inputs can achieve spatiotemporal control of Erk signaling in vivo

Light-induced Erk is more potent than any known gain-of-function mutation

Development is sensitive to changes in the spatial range but not the dose of Erk

Late embryogenesis is robust even to global changes in the level of Erk activity

eTOC PARAGRAPH.

The Ras/Erk pathway plays a conserved and essential role in development. Here, Johnson and Goyal et al. (2016) use optogenetics to manipulate Erk signaling in the Drosophila embryo, revealing its differential sensitivity to the dose, duration and spatial range of Erk activity.

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the Toettcher and Shvartsman labs for comments and suggestions throughout this work, and Kei Yamaya for her help with fly husbandry. We also thank Dr. Berg (University of Washington) for the Capicua antibody and Amin Ghabrial (University of Pennsylvania) for valuable comments. HEJ was supported by NIH Ruth Kirschstein fellowship F32GM119297. This work was also supported by NIH Grants R01GM077620 (TS), R01GM086537 (SYS and YG), and DP2EB024247 (JET). We also thank Dr. Gary Laevsky and the Molecular Biology Microscopy Core, which is a Nikon Center of Excellence, for microscopy support.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

H.E.J., Y.G., T.S., S.Y.S. and J.E.T. conceived and designed the project. H.E.J. and Y.G. performed experiments in flies and cell lines and H.E.J. and N.P. cloned the constructs. J.E.T. wrote the manuscript with input from all authors.

REFERENCES

- Bischof J, Maeda RK, Hediger M, Karch F, Basler K. An optimized transgenesis system for Drosophila using germ-line-specific phiC31 integrases. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104:3312–3317. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611511104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunner D, Oellers N, Szabad J, Biggs WH, 3rd, Zipursky SL, Hafen E. A gain-of-function mutation in Drosophila MAP kinase activates multiple receptor tyrosine kinase signaling pathways. Cell. 1994;76:875–888. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90362-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckley CE, Moore RE, Reade A, Goldberg AR, Weiner OD, Clarke JD. Reversible Optogenetic Control of Subcellular Protein Localization in a Live Vertebrate Embryo. Developmental cell. 2016;36:117–126. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2015.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corson LB, Yamanaka Y, Lai KM, Rossant J. Spatial and temporal patterns of ERK signaling during mouse embryogenesis. Development. 2003;130:4527–4537. doi: 10.1242/dev.00669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniels RW, Rossano AJ, Macleod GT, Ganetzky B. Expression of multiple transgenes from a single construct using viral 2A peptides in Drosophila. PloS one. 2014;9:e100637. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0100637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy JB. GAL4 system in Drosophila: a fly geneticist’s Swiss army knife. Genesis. 2002;34:1–15. doi: 10.1002/gene.10150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson SB, Blundon MA, Klovstad MS, Schupbach T. Modulation of gurken translation by insulin and TOR signaling in Drosophila. J Cell Sci. 2012;125:1407–1419. doi: 10.1242/jcs.090381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrell JE, Jr, Machleder EM. The biochemical basis of an all-or-none cell fate switch in Xenopus oocytes. Science. 1998;280:895–898. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5365.895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabay L, Seger R, Shilo BZ. In situ activation pattern of Drosophila EGF receptor pathway during development. Science. 1997a;277:1103–1106. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5329.1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabay L, Seger R, Shilo BZ. MAP kinase in situ activation atlas during Drosophila embryogenesis. Development. 1997b;124:3535–3541. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.18.3535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelb BD, Tartaglia M. RAS signaling pathway mutations and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: getting into and out of the thick of it. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2011;121:844–847. doi: 10.1172/JCI46399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghabrial AS, Levi BP, Krasnow MA. A systematic screen for tube morphogenesis and branching genes in the Drosophila tracheal system. PLoS genetics. 2011;7:e1002087. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimm O, Sanchez Zini V, Kim Y, Casanova J, Shvartsman SY, Wieschaus E. Torso RTK controls Capicua degradation by changing its subcellular localization. Development. 2012;139:3962–3968. doi: 10.1242/dev.084327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guglielmi G, Barry JD, Huber W, De Renzis S. An Optogenetic Method to Modulate Cell Contractility during Tissue Morphogenesis. Developmental cell. 2015;35:646–660. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2015.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guntas G, Hallett RA, Zimmerman SP, Williams T, Yumerefendi H, Bear JE, Kuhlman B. Engineering an improved light-induced dimer (iLID) for controlling the localization and activity of signaling proteins. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2015;112:112–117. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1417910112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoeller O, Toettcher JE, Cai H, Sun Y, Huang C-H, Freyre M, Zhao M, Devreotes PN, Weiner OD. Gβ Regulates Coupling between Actin Oscillators for Cell Polarity and Directional Migration. PLoS biology. 2016;14:e1002381. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter C, Wieschaus E. Regulated expression of nullo is required for the formation of distinct apical and basal adherens junctions in the Drosophila blastoderm. The Journal of cell biology. 2000;150:391–401. doi: 10.1083/jcb.150.2.391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez G, Guichet A, Ephrussi A, Casanova J. Relief of gene repression by torso RTK signaling: role of capicua in Drosophila terminal and dorsoventral patterning. Genes & development. 2000;14:224–231. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jindal GA, Goyal Y, Burdine RD, Rauen KA, Shvartsman SY. RASopathies: unraveling mechanisms with animal models. Dis Model Mech. 2015;8:1167. doi: 10.1242/dmm.022442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiehart DP, Montague RA, Rickoll WL, Foard D, Thomas GH. High-resolution microscopic methods for the analysis of cellular movements in Drosophila embryos. Methods Cell Biol. 1994;44:507–532. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(08)60929-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JH, Lee SR, Li LH, Park HJ, Park JH, Lee KY, Kim MK, Shin BA, Choi SY. High cleavage efficiency of a 2A peptide derived from porcine teschovirus-1 in human cell lines, zebrafish and mice. PloS one. 2011;6:e18556. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klambt C, Glazer L, Shilo BZ. breathless, a Drosophila FGF receptor homolog, is essential for migration of tracheal and specific midline glial cells. Genes & development. 1992;6:1668–1678. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.9.1668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klingler M, Erdelyi M, Szabad J, Nusslein-Volhard C. Function of torso in determining the terminal anlagen of the Drosophila embryo. Nature. 1988;335:275–277. doi: 10.1038/335275a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lander AD. Morpheus unbound: reimagining the morphogen gradient. Cell. 2007;128:245–256. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim B, Dsilva CJ, Levario TJ, Lu H, Schupbach T, Kevrekidis IG, Shvartsman SY. Dynamics of Inductive ERK Signaling in the Drosophila Embryo. Current biology : CB. 2015;25:1784–1790. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2015.05.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim B, Samper N, Lu H, Rushlow C, Jimenez G, Shvartsman SY. Kinetics of gene derepression by ERK signaling. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2013;110:10330–10335. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1303635110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen M, Park S, Marques G, Arora K. Interpretation of a BMP activity gradient in Drosophila embryos depends on synergistic signaling by two type I receptors, SAX and TKV. Cell. 1998;95:495–506. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81617-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nussleinvolhard C, Wieschaus E, Kluding H. Mutations Affecting the Pattern of the Larval Cuticle in Drosophila-Melanogaster .1. Zygotic Loci on the 2nd Chromosome. Roux Arch Dev Biol. 1984;193:267–282. doi: 10.1007/BF00848156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagani MR, Oishi K, Gelb BD, Zhong Y. The phosphatase SHP2 regulates the spacing effect for long-term memory induction. Cell. 2009;139:186–198. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.08.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pignoni F, Baldarelli RM, Steingrimsson E, Diaz RJ, Patapoutian A, Merriam JR, Lengyel JA. The Drosophila gene tailless is expressed at the embryonic termini and is a member of the steroid receptor superfamily. Cell. 1990;62:151–163. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90249-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price JV, Clifford RJ, Schupbach T. The maternal ventralizing locus torpedo is allelic to faint little ball, an embryonic lethal, and encodes the Drosophila EGF receptor homolog. Cell. 1989;56:1085–1092. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90641-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauen KA. The RASopathies. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2013;14:355–369. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genom-091212-153523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schejter ED, Shilo BZ. The Drosophila EGF receptor homolog (DER) gene is allelic to faint little ball, a locus essential for embryonic development. Cell. 1989;56:1093–1104. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90642-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweitzer R, Shaharabany M, Seger R, Shilo BZ. Secreted Spitz triggers the DER signaling pathway and is a limiting component in embryonic ventral ectoderm determination. Genes & development. 1995;9:1518–1529. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.12.1518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland D, Samakovlis C, Krasnow MA. branchless encodes a Drosophila FGF homolog that controls tracheal cell migration and the pattern of branching. Cell. 1996;87:1091–1101. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81803-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toettcher JE, Weiner OD, Lim WA. Using optogenetics to interrogate the dynamic control of signal transmission by the Ras/Erk module. Cell. 2013;155:1422–1434. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umesono Y, Tasaki J, Nishimura Y, Hrouda M, Kawaguchi E, Yazawa S, Nishimura O, Hosoda K, Inoue T, Agata K. The molecular logic for planarian regeneration along the anterior-posterior axis. Nature. 2013;500:73–76. doi: 10.1038/nature12359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urban S, Brown G, Freeman M. EGF receptor signalling protects smooth-cuticle cells from apoptosis during Drosophila ventral epidermis development. Development. 2004;131:1835–1845. doi: 10.1242/dev.01058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.