Abstract

Termination efficiency of stop codons depends on the first 3′ flanking (+4) base in bacteria and eukaryotes. In both Escherichia coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae, termination read-through is reduced in the presence of +4U; however, the molecular mechanism underlying +4U function is poorly understood. Here, we perform comparative genomics analysis on 25 bacterial species (covering Actinobacteria, Bacteriodetes, Cyanobacteria, Deinococcus-Thermus, Firmicutes, Proteobacteria, and Spirochaetae) with bioinformatics approaches to examine the influence of +4U in bacterial translation termination by contrasting highly- and lowly-expressed genes (HEGs and LEGs, respectively). We estimated gene expression using the recently formulated Index of Translation Elongation, ITE, and identified stop codon near-cognate transfer RNAs (tRNAs) from well-annotated genomes. We show that +4U was consistently overrepresented in UAA-ending HEGs relative to LEGs. The result is consistent with the interpretation that +4U enhances termination mainly for UAA. Usage of +4U decreases in GC-rich species where most stop codons are UGA and UAG, with few UAA-ending genes, which is expected if UAA usage in HEGs drives up +4U usage. In HEGs, +4U usage increases significantly with abundance of UAA nc_tRNAs (near-cognate tRNAs that decode codons differing from UAA by a single nucleotide), particularly those with a mismatch at the first stop codon site. UAA is always the preferred stop codon in HEGs, and our results suggest that UAAU is the most efficient translation termination signal in bacteria.

Keywords: translation termination, termination read-through, gene expression, release factors

DIFFERENT stop codons have different termination efficiency, and replacing UGA with UAA reduces termination read-through of human genes expressed in Escherichia coli (Meng et al. 1995; Cesar Sanchez et al. 1998). The discrepancies in termination efficiency among stop codons in bacteria are largely attributed to: (1) the competition between near-cognate transfer RNAs (tRNAs) (nc_tRNAs) and class I release factors (RF1 and RF2) in decoding stop codons (Nakamura et al. 1996; Tate et al. 1999; Blanchet et al. 2014), mediated by the relative abundance of RF1 and RF2 (Korkmaz et al. 2014; Wei et al. 2016), and (2) nucleotide sites downstream of stop codons interacting with 18S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) and modulating the structural stability of binding sites for RF1 and RF2 (Namy et al. 2001) or interacting directly with release factors based on inferences from cross-linking experiments in both bacterial (Poole et al. 1998) and eukaryotic species (Bulygin et al. 2002).

Termination efficiency of stop codons depends on the first 3′-flanking (+4) base in bacterial species such as E. coli and Salmonella typhimurium (Bossi and Ruth 1980; Miller and Albertini 1983; Tate et al. 1995; Poole et al. 1998) and in eukaryotes (Manuvakhova et al. 2000; Jungreis et al. 2011). The inefficiency of translation termination associated with +4C, especially in UGA-ending genes, is well-documented in both bacteria (Brown and Tate 1994; Poole et al. 1995; Tate et al. 1999) and eukaryotes (Manuvakhova et al. 2000; Namy et al. 2001; Jungreis et al. 2011; Dabrowski et al. 2015; Beznoskova et al. 2016). UGA-C contributes to the autoregulation of prfB (coding RF2) translation (Craigen et al. 1985; Craigen and Caskey 1986), with a truncated RF2 produced when functional RF2 is abundant and a full-length functional RF2 produced when functional RF2 is rare. Baranov et al. (2002) identified the prfB gene in 87 bacterial species using BLAST (Altschul et al. 1990), and revealed programmed frameshift in 70% of these bacteria. The segment involved in the frameshift (CUU UGA CNN) and the translated segment (CUU GAC NNN) are always conserved, showing ribosome slippage at UGA-C.

UGA is particularly prone to be misread by tRNATrp when followed by +4A in E. coli (Engelberg-Kulka 1981) and yeast (Geller and Rich 1980). A recent study in yeast by Beznoskova et al. (2016) measured the read-through of termination tetranucleotides (e.g., UGA-C) in dual luciferase constructs. Indeed, +4C increases read-through in all three stop codons, but particularly so in UGA in yeast. Furthermore, UGA-A and UGA-G enhance misreading by tRNATrp and tRNACys, respectively (Beznoskova et al. 2016). In contrast, UGA-U, UAA-U, and UAG-U are all associated with low read-through (Beznoskova et al. 2016). The finding that +4U reduces termination read-through is consistent with the observation that this base is overrepresented in E. coli, especially in UAA-ending genes (Brown et al. 1990; Poole et al. 1995; Tate et al. 1996).

Early studies in E. coli suggest that the decoding efficiency of RF2 depends on the +4 base (Brown and Tate 1994; Tate et al. 1996; Poole et al. 1997, 1998). In particular, Brown and Tate (1994) and Poole et al. (1998) revealed that RF2 cross-links with UAA, and with UGA at the first (+ 1) base and the downstream +4 base; and the cross-link efficiency between RF2 and stop codons is promoted in the presence of +4U. Thus, +4U may participate in recruiting RF2 to the stop codon. Similarly, studies in eukaryotes found cross-linking between the +4 base and eRF1 in human UAA-ending genes (Bulygin et al. 2002).

If the +4 site really serves as part of an extended stop signal, and if +4U enhances the stop signal relative to other nucleotides, then one can immediately predict that highly-expressed genes (HEGs), which are under selection to evolve toward high translation initiation, elongation, and termination efficiency, should prefer +4U more strongly than lowly-expressed genes (LEGs). Furthermore, it is possible that different stop codons may require different +4 nucleotides to enhance the stop signal. In particular, GC-rich species may have difficulty maintaining a +4U site and may have different combinations of stop codons and +4 nucleotides from those AT-rich species. Testing these predictions constitutes the first part of this paper.

Stop codons can be misread by nc_tRNAs in E. coli (Sambrook et al. 1967; Strigini and Brickman 1973), coliphage (Weiner and Weber 1973), eukaryotic viruses (Beier and Grimm 2001), the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Blanchet et al. 2014), and mammals (Geller and Rich 1980). Available data suggest termination read-through is most frequent at UGA, less at UAG, and least at UAA, in both bacteria and eukaryotes (Parker 1989; Jorgensen et al. 1993; Tate et al. 1999; Dabrowski et al. 2015).

Stop codon read-through can occur in yeast by the incorporation of nc_tRNAs with wobble-pairing at the third stop codon site (Beznoskova et al. 2015, 2016), or at the first stop codon site involving tRNAUUG/Gln and tRNACUG/Gln misreading UAA and UAG, respectively (Blanchet et al. 2014; Roy et al. 2015, 2016). In the yeast, tRNAGln, tRNATyr, and tRNALys can misread stop codons UAA and UAG, whereas tRNATrp, tRNACys, and tRNAArg can misread stop codon UGA (Blanchet et al. 2014). Misreading of UAA and UAG by tRNAGln also occurs in E. coli (Nilsson and Ryden-Aulin 2003). UGA can be misread by tRNATrp decoding UGG in both E. coli and Bacillus subtilis (Engelberg-Kulka 1981; Matsugi and Murao 1999, 2000; Nilsson and Ryden-Aulin 2003).

How +4U may enhance the stop codon signal remains unknown. Namy et al. (2001) speculated that, in yeast UAG-ending genes, several bases at the 3′-UTR leading with +4C may pair with yeast 18S rRNA and destabilize secondary structures in the ribosome, preventing release factors from binding to stop codons. However, it is possible that +4U may serve to prevent misreading of stop codons by nc_tRNA. If this is the case, then + U usage should increase with the frequency of nc_tRNA, which is an easily testable prediction. Testing this prediction constitutes the second part of this study.

We analyzed the genomic and proteomic data in 25 bacterial species (Supplemental Material, Table S1 in File S2), whose protein abundance data are present in PaxDB 4.0 (Wang et al. 2015), to examine the effect of the +4 site and nc_tRNA on termination efficiency of the three stop codons. We found that +4U was consistently overrepresented in HEGs in contrast to LEGs in bacteria. However, +4U usage in HEGs decreased in GC-rich bacterial species where most stop codons are UGA and UAG, suggesting that UGA and UAG do not need +4U as a stop signal enhancer as much as UAA. In HEGs, +4U usage also increases significantly with the abundance of UAA nc_tRNAs, suggesting that +4U increases UAA termination efficiency, presumably by reducing the misreading of UAA by nc_tRNAs.

Materials and Methods

Protein expression data

Proteomic data are available in PaxDB 4.0 (Wang et al. 2015) for 26 bacterial species of which one (Mycoplasma pneumoniae) is excluded from this study. The reason for the exclusion is that M. pneumoniae uses genetic code 4, thus is different from the other species which use genetic code 11. M. pneumoniae uses only two stop codons (UAA and UAG, decoded by RF1) and does not have prfB genes coding for RF2 (which would decode UAA and UGA). The integrated data set was chosen when there were multiple data sets for a single species. B. subtilis protein IDs in PaxDB are UniProt IDs; the “Retrieve/ID mapping” function in UniProt (Pundir et al. 2016) was used to map UniProt IDs to Gene IDs.

Proteomic data are used to classify genes into HEGs and LEGs for compiling codon usage tables of HEGs and LEGs that are needed for computing the index of translation elongation or ITE (Xia 2015). ITE incorporates the tRNA-mediated selection and the effect of background mutation, and is therefore advantageous over codon adaptation index (Sharp and Li 1987; Xia 2007) or tRNA adaptation index (dos Reis et al. 2004) when genomes of diverse GC% are used in analysis. We used ITE as a proxy of translation efficiency. That is, genes with a high ITE are expected to be under stronger selection for translation efficiency than genes with a low ITE.

For each of the 25 species, 40 ribosomal protein genes with the highest protein abundances (parts per million) and 40 genes with the lowest nonzero protein abundances were taken from each species to compile codon usage for HEGs and LEGs, respectively. ITE was computed with the option of “Break 8-fold and 6-fold families into 2.” Only nonpseudo and nonhypothetical genes were selected in this study.

Among the 25 species, five species (Bartonella henselae, Helicobacter pylori, Leptospira interrogans, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Synechocystis sp.) do not exhibit clear differences in codon usage between HEGs and LEGs. This means that ITE will not be a good proxy for translation efficiency in these five species. Shigella flexneri is phylogenetically nested within E. coli strains and therefore does not supply an independent data point. For this reason, only those 19 remaining species were used for ITE-related analysis.

Processing bacterial genomes

The bacterial genomes were retrieved from GenBank, and coding sequences (CDSs) were extracted by using DAMBE (Xia 2013b) for computing ITE. An alternative set of HEGs consists of all ribosomal protein genes extracted from DAMBE (Xia 2013b) based on genomic annotation. We also extracted small subunit rRNA (ssu rRNA) genes from each species for building a phylogenetic tree for computing independent contrasts. For each stop codon, their nc_tRNAs (Table 1) were compiled. No tRNA had anticodons AUA or ACA in the species studied and, thus, they are not included in Table 1.

Table 1. Anticodons of nc_tRNAs for each of the three stop codons.

| UAA | UAG | UGA |

|---|---|---|

| Glu-TTC | Glu-CTC | Gly-TCC |

| Gln-TTG | Gln-CTG | Arg-TCG |

| Lys-TTT | Lys-CTT | Arg-TCT |

| Leu-TAA | Leu-CAA | Leu-TAA |

| Ser-TGA | Trp-CCA | Ser-TGA |

| Tyr-GTA | Ser-CGA | Trp-CCA |

| Tyr-GTA | Cys-GCA |

No tRNA (transfer RNA) has AUA or ACA anticodons in all of the bacterial species we studied.

Phylogenetic reconstruction and independent contrasts

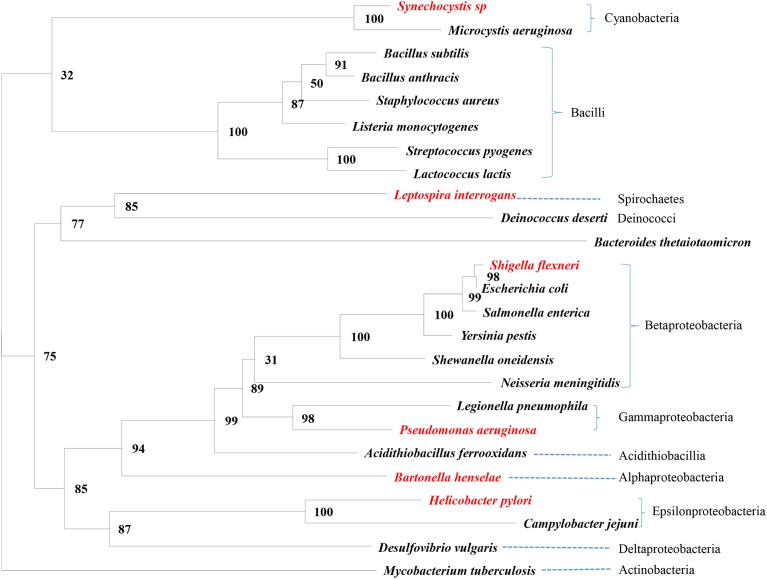

Variables measured from a set of species are typically not independent because of shared ancestry. Phylogeny-based independent contrasts (Felsenstein 1985) were computed to alleviate this problem. We aligned ssu rRNA sequences aligned by MAFFT (Katoh et al. 2009) with the LINSI option, which generates the most accurate alignment (“–localpair” and “–maxiterate = 1000”). PhyML (Guindon and Gascuel 2003) was used for phylogenetic reconstruction, with general time reversible (GTR) substitution model and six categories of gamma-distributed rates. The resulting tree (Figure 1) was used for computing independent contrasts (Felsenstein 1985), as numerically illustrated in Xia (2013a). The same approach was used to reconstruct the tree for the 19 species (indicated in Figure 1) in ITE-related analysis.

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic relationship among the 25 bacterial species. The six species in red were not used in ITE-related analysis (see Materials and Methods for reason of exclusion). The branch length for Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron was shortened by nearly one-third for a more compact display. ITE, Index of Translation Elongation.

Because the bacterial species involve deep phylogeny with limited resolution close to the root node, we assessed the effect of different trees on the results of independent contrasts by using 100 bootstrapped trees. DAMBE takes a file with the 100 trees and automatically performs independent contrasts for each tree. We have also used a tree built with PhyPA, suitable for deep phylogenetic relationships (Xia 2016). The PhyPA is based on pairwise sequence alignment using default option simultaneously estimated distances based on a TN93 model (Tamura and Nei 1993).

Data availability

File S1 contains a detailed description of File S2, File S3, File S4, and File S5, and provides additional details for the Materials and Methods. File S2 contains supplementary tables and figures discussed in this manuscript. HEG_RSCU and LEG_RSCU data are provided in File S3. File S4 contains ITE scores for all CDSs in 19 bacterial species. File S5 contains the associated data for Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5, and Figure 6.

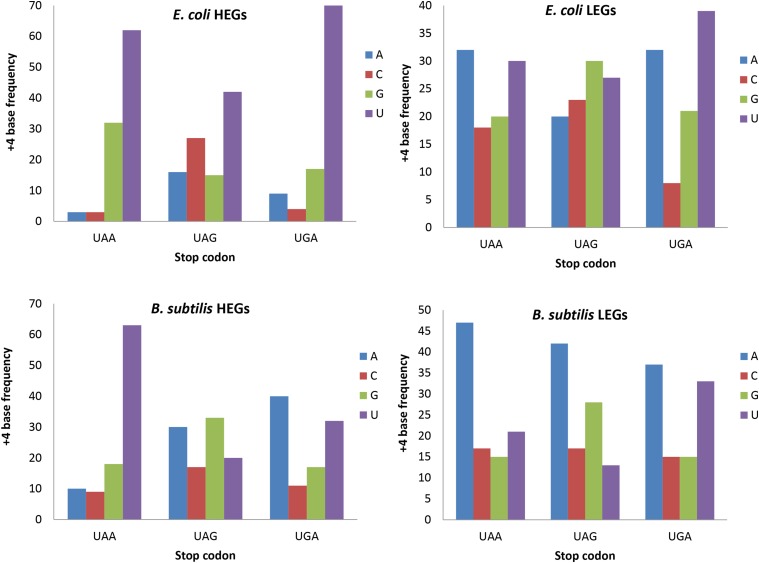

Figure 2.

Relationship between +4 nucleotide usage and stop codons in E. coli and B. subtilis, contrasting between 100 highly- and 100 lowly-expressed genes (HEGs and LEGs, respectively) for each stop codon, respectively. Only nonpseudo and nonhypothetical genes are used.

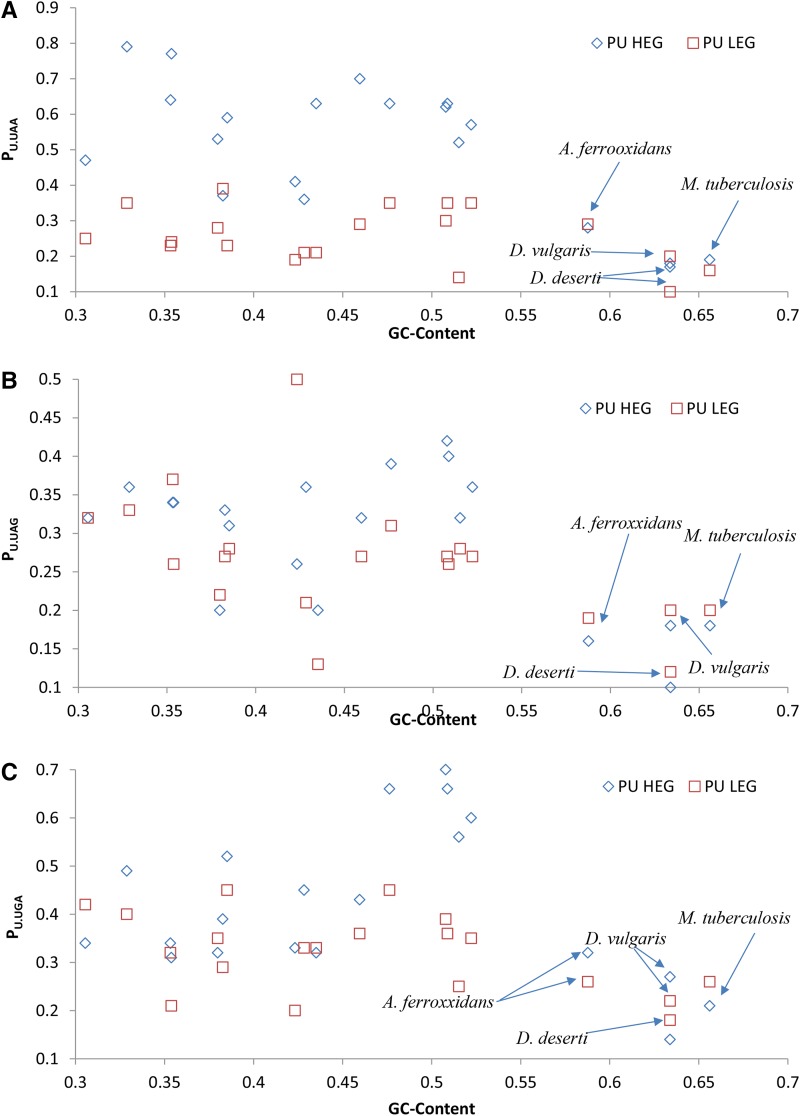

Figure 3.

Relationship between genomic GC-content (proportion of G and C in the genome) and +4U usage measured as the proportion of +4U at the +4 site and designated by PU.UAA (A), PU.UAG (B), and PU.UGA (C), respectively, for the three stop codons in 19 bacterial species. 100 HEGs and 100 LEGs are used for each stop codon. Only nonpseudo, nonhypothetical genes are used. The four species with high GC-contents (> 58%) are indicated. HEGs, highly-expressed genes; LEGs, lowly-expressed genes.

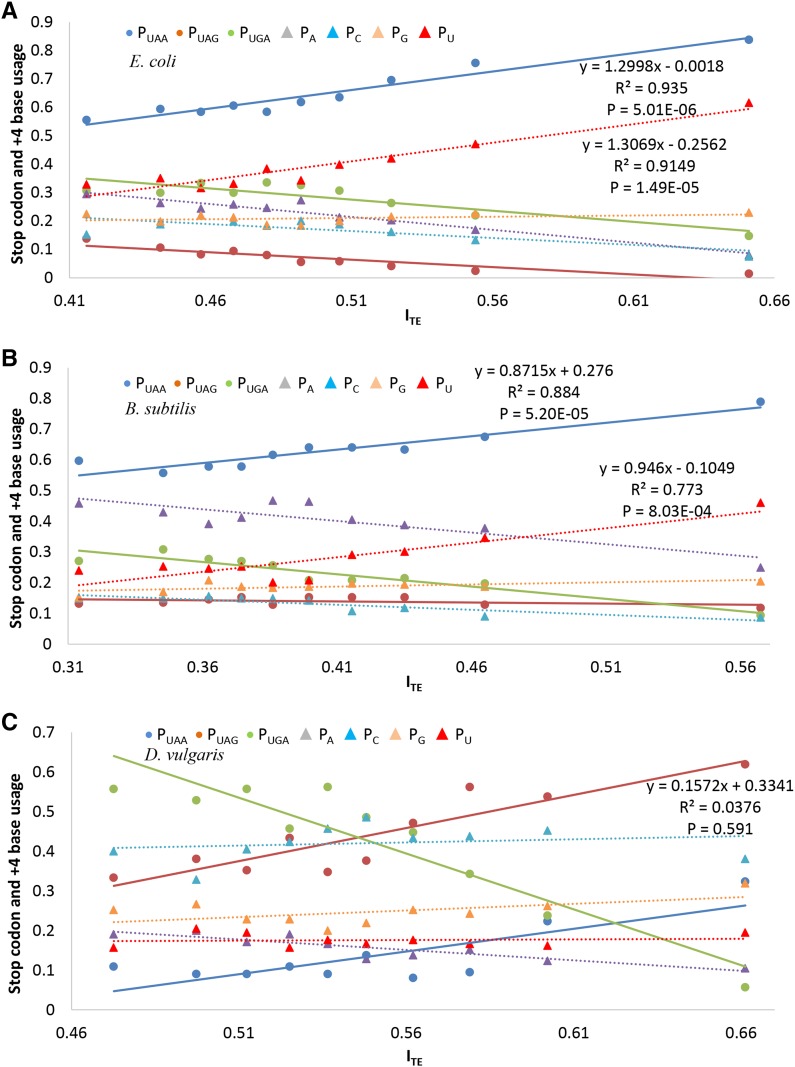

Figure 4.

Relationship between ITE and usage of termination signals (stop codons and +4 bases), in E. coli (A), B. subtilis (B), and D. vulgaris (C). All nonpseudo, nonhypothetical CDSs were ranked by ITE and binned into 10 sets; the stop codon usage and +4 base usage was obtained in each set. Stop codon usage (PUAA, PUAG, and PUGA) is represented by solid lines; +4 base usage (PA, PC, PG, and PU) is represented by dotted lines. CDSs, coding sequences; ITE, Index of Translation Elongation.

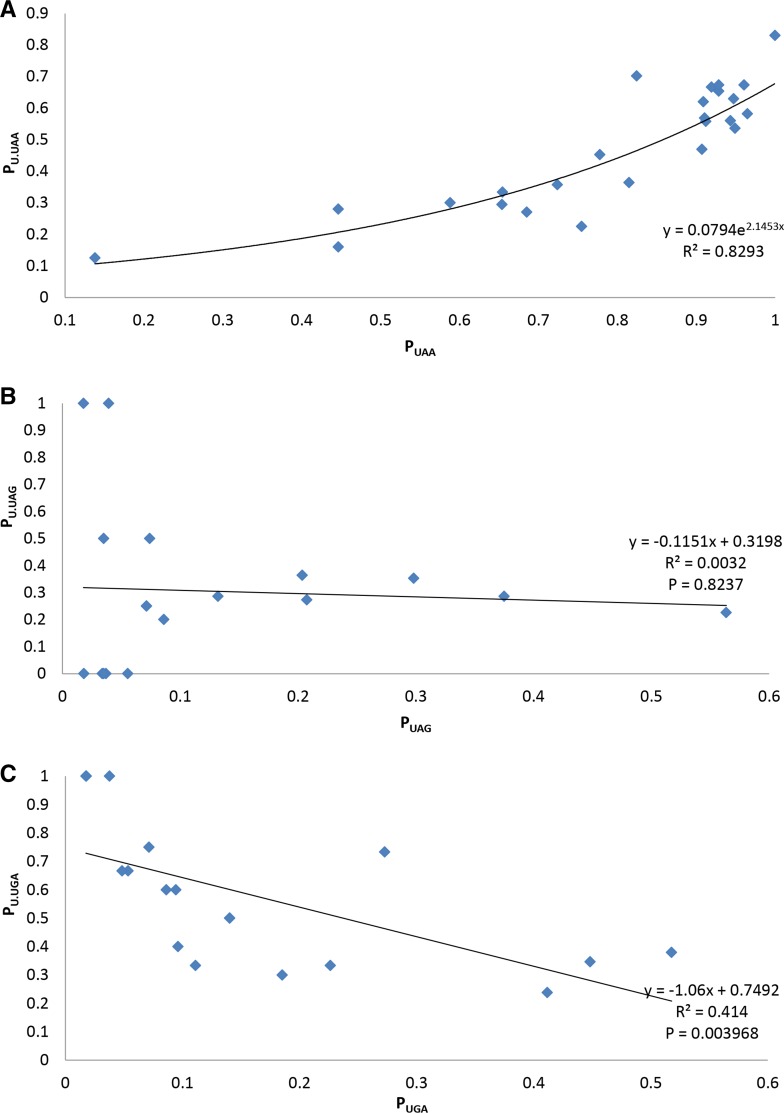

Figure 5.

Relationship between stop codon and +4 base usage, represented with regression between the proportions of stop codons (PUAA, PUAG, and PUGA) and proportion of their +4U (PU.UAA, PU.UAG, and PU.UGA), and shown in (A), (B), and (C), respectively. Data from all 30S and 50S ribosomal protein genes in 25 bacterial species, excluding the data point if the stop codon usage is zero.

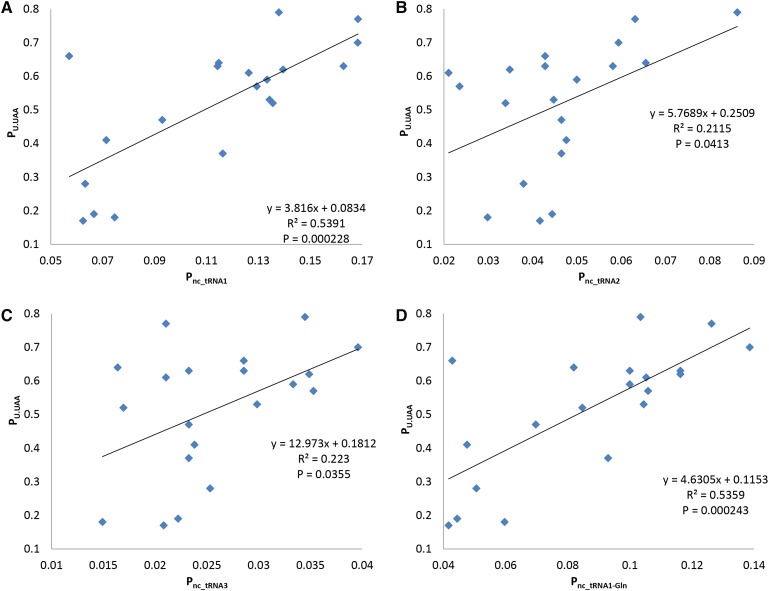

Figure 6.

Relationship between nc_tRNA abundance and +4U usage, represented by linear regression between 100 UAA-ending HEGs (highest ITE scores) and abundance of UAA nc_tRNAs with a single mismatch at (A) the first stop codon site, (B) the second stop codon site, (C) the third stop codon site, and (D) the first stop codon site, omitting tRNAGln, 5′-TTG-3′, in 19 bacterial species. CDSs, coding sequences; HEGs, highly-expressed genes; ITE, Index of Translation Elongation; nc_tRNA, near-cognate tRNA; tRNA, transfer RNA.

Results

HEGs and LEGS differ in the relationship between +4U and stop codons

+4U is strongly overrepresented in all stop codons in E. coli, especially for UAA-ending and UGA-ending HEGs (Figure 2). In contrast, +4U is overrepresented in UAA-ending HEGs relative to UAA-ending LEGs in B. subtilis (Figure 2). In each species, the nucleotide distribution at the +4 site depends significantly on stop codons (P < 0.0001) when tested by log-linear models. The difference between the two species is also highly significant (P < 0.0001), with the main contribution to the difference from +4 sites following UAG and UGA. While both species exhibit overuse of +4U in UAA-ending HEGs, only E. coli overused +4U in UGA-ending HEGs. A previous experimental study demonstrated a strong effect of +4U in increasing the termination efficiency of UGA (Kopelowitz et al. 1992).

All five of the species belonging to Betaproteobacteria (Figure 1) share the E. coli pattern, i.e., +4U overrepresented in all stop codons in HEGs relative to LEGs (Table 2), and all seven species belonging to Cyanobacteria and Bacilli share the B. subtilis pattern, with strong overrepresentation of +4U in UAA-ending HEGs relative UAA-ending LEGs, but no clear pattern involving UAG and UGA codons (Table 2). Species with the E. coli pattern generally have far more RF2 than RF1, whereas those with the B. subtilis pattern have more RF1 than RF2 (Wei et al. 2016). It is likely that +4U increases termination efficiency for RF2 decoding UAA and UGA, whereas RF1 may benefit from +4U only in decoding UAA. This would suggest that overuse of UAA by HEGs would result in overuse of +4U. This is indeed the case. The species with overrepresented +4U in HEGs, i.e., the seven species belonging Cyanobacteria and Bacilli and the five species belonging to Betaproteobacteria, indeed all have more UAA overrepresented in HEGs than LEGs.

Table 2. The usage of +4U (PU) in 100 nonpseudo and nonhypothetical UAA, UAG, and UGA-ending HEGs and LEGs, ranked by ITE, in 19 bacterial species, together with the species’ accession number and genomic GC content.

| Species Name | Accession | GC% | UAA | UAG | UGA | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PU.HEG | PU.LEG | PU.HEG | PU.LEG | PU.HEG | PU.LEG | |||

| Microcystis aeruginosa | NC_010296 | 42.331 | 0.41 | 0.19 | 0.26 | 0.5 | 0.33 | 0.2 |

| Bacillus anthracis | NC_005945 | 35.379 | 0.77 | 0.24 | 0.34 | 0.26 | 0.31 | 0.21 |

| Bacillus subtilis | NC_000964 | 43.514 | 0.63 | 0.21 | 0.2 | 0.13 | 0.32 | 0.33 |

| Staphylococcus aureus | NC_002758 | 32.878 | 0.79 | 0.35 | 0.36 | 0.33 | 0.49 | 0.40 |

| Listeria monocytogenes | NC_003210 | 37.981 | 0.53 | 0.28 | 0.2 | 0.22 | 0.32 | 0.35 |

| Streptococcus pyogenes | NC_002737 | 38.512 | 0.59 | 0.23 | 0.31 | 0.28 | 0.52 | 0.45 |

| Lactococcus lactis | NC_002662 | 35.329 | 0.64 | 0.23 | 0.34 | 0.37 | 0.34 | 0.32 |

| Deinococcus deserti | NC_002937 | 63.388 | 0.17 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.12 | 0.14 | 0.18 |

| Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron | NC_004663 | 42.837 | 0.66 | 0.33 | 0.36 | 0.21 | 0.45 | 0.33 |

| Escherichia coli | NC_000913 | 50.791 | 0.62 | 0.3 | 0.42 | 0.27 | 0.7 | 0.39 |

| Salmonella enterica | NC_003197 | 52.222 | 0.57 | 0.35 | 0.36 | 0.27 | 0.6 | 0.35 |

| Yersinia pestis | NC_003143 | 47.636 | 0.63 | 0.35 | 0.39 | 0.31 | 0.66 | 0.45 |

| Shewanella oneidensis | NC_004347 | 45.961 | 0.7 | 0.29 | 0.32 | 0.27 | 0.43 | 0.36 |

| Neisseria meningitidis | NC_003112 | 51.528 | 0.52 | 0.14 | 0.32 | 0.28 | 0.56 | 0.25 |

| Legionella pneumophila | NC_002942 | 38.27 | 0.37 | 0.39 | 0.33 | 0.27 | 0.39 | 0.29 |

| Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans | NC_011761 | 58.773 | 0.28 | 0.29 | 0.16 | 0.19 | 0.32 | 0.26 |

| Campylobacter jejuni | NC_002163 | 30.549 | 0.47 | 0.25 | 0.32 | 0.32 | 0.34 | 0.42 |

| Desulfovibrio vulgaris | NC_002937 | 63.388 | 0.18 | 0.2 | 0.18 | 0.2 | 0.27 | 0.22 |

| Mycobacterium tuberculosis | NC_000962 | 65.615 | 0.19 | 0.16 | 0.18 | 0.2 | 0.21 | 0.26 |

A value of 0.26 under UAA/PU.HEG means 26 genes out of 100 UAA-ending HEGs have +4U. Horizontal lines delineate major taxonomic groups corresponding to Figure 1. HEG, highly-expressed gene; LEG, lowly-expressed gene.

The usage of +4U changes with genomic GC% (Figure 3), with the overuse of +4U most pronounced in UAA-ending genes with the proportion of genomic GC from low to slightly higher than 50% (Figure 3). Based on the Wilcoxon rank sum test with continuity correction, the difference in +4U usage between HEGs and LEGs is significant in UAA-ending genes (P = 0.000327, two-tailed test), but not significant in UAG-ending genes (P = 0.2538, two-tailed test) and UGA-ending genes (P = 0.0795, two-tailed test). However, four species with high genomic GC contents (> 58.7%) (M. tuberculosis, Deinococcus deserti, Desulfovibrio vulgaris, and Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans), do not have higher PU in HEGs than LEGs (Wilcoxon rank sum test: P = 0.706, two-tailed test; Table 2). These four species, being GC-rich, have few UAA-ending genes; this is consistent with our previous interpretation from Figure 2 and Figure 3, that UAA-ending genes are the main driver for increased +4U. Few UAA-ending genes implies little selection driving up +4U usage.

We investigated how stop codon and +4 nucleotide usage change with ITE (a proxy of translation efficiency and gene expression) for three species (E. coli, B. subtilis, and D. vulgaris) that appear to represent the three different patterns: (1) +4U is overrepresented in HEGs, (2) +4U is overrepresented in only UAA-ending HEGs, and (3) +4U is not overrepresented, respectively. We binned all nonpseudo, nonhypothetical CDSs into 10 gene groups ranked by ITE. ITE is significantly and positively correlated with PUAA in all three species (E. coli: R2 = 0.935, P < 0.0001; B. subtilis: PUAA: R2 = 0.884, P < 0.0001; D. vulgaris: R2 = 0.644, P = 0.00518; Figure 4), even when UAA accounts for a small fraction of the stop codons. This is consistent with a previous study (Wei et al. 2016) showing UAA to be always preferred by HEGs. Furthermore, ITE was significantly positively correlated with PU in E. coli (R2 = 0.9149, P < 0.0001) and in B. subtilis (R2 = 0.773, P < 0.001), but not in D. vulgaris (R2 = 0.0098, P = 0.786). No significant relationship between other nucleotides at the +4 site and ITE was observed (Figure 4). To show that the U bias exists only at the +4 site, we randomly shuffled 20 nucleotides in the (5′-UTR) for all 4140 nonpseudo, nonhypothetical E. coli genes, and the significant correlation between ITE and PU disappeared (R2 = 0.0301, P = 0.632; Figure S1 in File S2). To validate that other metrics of codon usage bias return compatible results, we measured HEGs and LEGs by CAI (Table S1 in File S2); the two metrics (CAI and ITE) return similar +4U usage (Wilcoxon rank sum test with continuity correction: P = 0.845, two-tailed test).

The overuse of +4U in UAA-ending genes is also visible in the highly-expressed 30S and 50S ribosomal protein genes (Figure 5A, Spearman rank correlation = 0.8385, d.f. = 25, P < 0.0001), and the fitted nonlinear curve (Figure 5A) accounts for 82.93% of the variation in PU.UAA. There is no significant correlation between PU.UAG and PUAG (Figure 5B, R2 = 0.0032, P = 0.8237), and a negative linear correlation between PU.UGA and PUGA (Figure 5C, R2 = 0.414, P = 0.003968). Here, all 25 species (Figure 1) were analyzed since ribosomal protein genes were considered. To alleviate the issue of data dependence due to shared ancestry between species (Figure 1), we performed linear regression on Felsenstein’s phylogeny-based independent contrasts (Felsenstein 1985); and the correlation between PU.UAA and PUAA was still significant (R2 = 0.5819, P < 0.0001), and the result is consistent with bootstrapped trees or the tree reconstructed by using PhyPA (Xia 2016).

Relationship between +4U usage and nc_tRNA abundance

We have hypothesized that +4U reduces misreading of stop codons, especially UAA, by nc_tRNAs (Table 1). We used tRNA gene copy numbers as a proxy of tRNA abundance. This approach has been fruitful in a number of studies (Duret and Mouchiroud 1999; Kanaya et al. 1999; Percudani et al. 1997; Chithambaram et al. 2014a,b; Prabhakaran et al. 2014). We denoted nc_tRNA1, nc_tRNA2, and nc_tRNA3 as the number of nc_tRNAs with a single mismatch at the first, second, and third stop codon site, respectively. In each species, Pnc_tRNA1 was calculated as the number of nc_tRNA1 copies divided by the total number of tRNA copies. In the 19 bacterial species, PU in UAA-ending HEGs was significantly and positively correlated with Pnc_tRNA, the relationship being particularly strong in nc_tRNAs with a single mismatch at the first stop codon site (Figure 6). This positive correlation remains highly significant even after excluding nc_tRNAGln, which is a key contributor to UAA read-through (Blanchet et al. 2014; Roy et al. 2015, 2016) (R2 = 0.517, P = 0.0005, Figure 6D). The correlation between PU and Pnc_tRNA was, however, not significant in UAG and UGA-ending HEGs (Figure S2 in File S2).

To alleviate data dependence due to shared ancestry, we performed regression on independent contrasts (Felsenstein 1985) that showed significant correlation between PU and Pnc_tRNA1 (R2 = 0.349, P = 0.00985) and between PU and Pnc_tRNA1 – Gln (R2 = 0.501, P = 0.00101), but weak linear correlation between PU and Pnc_tRNA2 (R2 = 0.150, P = 0.112) and Pnc_tRNA3 (R2 = 0.233, P = 0.0424).

Discussion

UAA is consistently the preferred stop codon in HEGs in a diverse array of bacterial species (Wei et al. 2016), presumably because: (1) UAA can be decoded by both RF1 and RF2 (Scolnick et al. 1968; Milman et al. 1969; Nakamura et al. 1996), and (2) UAA has the least termination read-through (Parker 1989; Jorgensen et al. 1993; Meng et al. 1995; Cesar Sanchez et al. 1998; Tate et al. 1999; Dabrowski et al. 2015). Our study advanced these studies by showing that: (1) +4U is strongly associated with UAA in HEGs relative to LEGs, (2) +4U usage increases with an increasing number of nc_tRNAs, and (3) both UAA and +4U usage increases with gene expressed measured by ITE. Taken together, these findings suggest that +4U may enhance the UAA stop signal by reducing misreading by nc_tRNAs. This interpretation is consistent with read-through studies discussed previously and with the finding that termination suppression of stop codons was least efficient in the presence of +4U in E. coli (Kopelowitz et al. 1992). Consequently, the tetranucleotide UAAU is expected to represent the strongest termination signal a variety of bacterial lineages.

The interpretation above also explains why +4U is not overused in GC-rich species (Figure 3 and Table 2), because these species have few genes ending with UAA. If +4U mainly enhances the termination signal of UAA against misreading by nc_tRNAs, the rarity of UAA-ending genes is naturally expected not to associate with overuse of +4U.

The importance of considering gene expression (or translation efficiency) in studying codon adaptation is highlighted by the fact that little +4U bias would be observed in the 19 species when all CDSs were considered (Figure S3 in File S2) without contrasting between HEGs and LEGs. It is also important to study +4U bias separately for different stop codons because nucleotide distribution at the +4 site is heterogeneous among genes ending with different stop codons (Figure 2). Previous studies on termination read-through in yeast (Roy et al. 2015, 2016) and bacteria (Kramer and Farabaugh 2007) often did not take into consideration all of the possible combinations of stop codons and the +4U nucleotide.

Our study also suggests phylogenetic inertia in the evolution of the stop codon decoding mechanism. For example, all five species in Betaproteobacteria exhibit very similar differences between HEGs and LEGs in +4U usage, so do the seven species belonging to the supercluster including Cyanobacteria and Bacilli (Figure 1). For this reason, phylogeny-based comparative methods are crucial for the proper assessment of statistical significance among variables.

It is interesting to note that UGA- and UAG-ending genes do not show the same strong preference for +4U observed in UAA-ending genes. Given that RF1 decodes UAA and UAG, and RF2 decodes UAA and UGA, it seems that RF1 and RF2 must have different binding dynamics between UAA- and UAG-ending genes. Structural (Matheisl et al. 2015; Svidritskiy et al. 2016; Tang et al. 2016) or cross-linking studies (Brown and Tate 1994; Tate et al. 1996; Poole et al. 1997, 1998) may shed light on the effect of +4U on the UAA termination signal.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental material is available online at www.genetics.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1534/genetics.116.193961/-/DC1.

Acknowledgments

We thank J. Wang, J. Silke, and C. Vlasschaert for discussion and comments, and the two reviewers for suggestions that have led to significant improvement of the manuscript. This study is funded by a Discovery grant from the Natural Science and Engineering Research Council of Canada to X.X. (RGPIN/261252-2013).

Footnotes

Communicating editor: J. Lawrence

Literature Cited

- Altschul S. F., Gish W., Miller W., Myers E. W., Lipman D. J., 1990. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215: 403–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baranov P. V., Gesteland R. F., Atkins J. F., 2002. Release factor 2 frameshifting sites in different bacteria. EMBO Rep. 3: 373–377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beier H., Grimm M., 2001. Misreading of termination codons in eukaryotes by natural nonsense suppressor tRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 29: 4767–4782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beznoskova P., Wagner S., Jansen M. E., von der Haar T., Valasek L. S., 2015. Translation initiation factor eIF3 promotes programmed stop codon readthrough. Nucleic Acids Res. 43: 5099–5111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beznoskova P., Gunisova S., Valasek L. S., 2016. Rules of UGA-N decoding by near-cognate tRNAs and analysis of readthrough on short uORFs in yeast. RNA 22: 456–466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchet S., Cornu D., Argentini M., Namy O., 2014. New insights into the incorporation of natural suppressor tRNAs at stop codons in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nucleic Acids Res. 42: 10061–10072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bossi L., Ruth J. R., 1980. The influence of codon context on genetic code translation. Nature 286: 123–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown C. M., Tate W. P., 1994. Direct recognition of mRNA stop signals by Escherichia coli polypeptide chain release factor two. J. Biol. Chem. 269: 33164–33170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown C. M., Stockwell P. A., Trotman C. N., Tate W. P., 1990. The signal for the termination of protein synthesis in procaryotes. Nucleic Acids Res. 18: 2079–2086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulygin K. N., Repkova M. N., Ven’yaminova A. G., Graifer D. M., Karpova G. G., et al. , 2002. Positioning of the mRNA stop signal with respect to polypeptide chain release factors and ribosomal proteins in 80S ribosomes. FEBS Lett. 514: 96–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cesar Sanchez J., Padron G., Santana H., Herrera L., 1998. Elimination of an HuIFN alpha 2b readthrough species, produced in Escherichia coli, by replacing its natural translational stop signal. J. Biotechnol. 63: 179–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chithambaram S., Prabhakaran R., Xia X., 2014a Differential codon adaptation between dsDNA and ssDNA phages in Escherichia coli. Mol. Biol. Evol. 31: 1606–1617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chithambaram S., Prabhakaran R., Xia X., 2014b The effect of mutation and selection on codon adaptation in Escherichia coli bacteriophage. Genetics 197: 301–315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craigen W. J., Caskey C. T., 1986. Expression of peptide chain release factor 2 requires high-efficiency frameshift. Nature 322: 273–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craigen W. J., Cook R. G., Tate W. P., Caskey C. T., 1985. Bacterial peptide chain release factors: conserved primary structure and possible frameshift regulation of release factor 2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 82: 3616–3620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dabrowski M., Bukowy-Bieryllo Z., Zietkiewicz E., 2015. Translational readthrough potential of natural termination codons in eucaryotes–The impact of RNA sequence. RNA Biol. 12: 950–958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- dos Reis M., Savva R., Wernisch L., 2004. Solving the riddle of codon usage preferences: a test for translational selection. Nucleic Acids Res. 32: 5036–5044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duret L., Mouchiroud D., 1999. Expression pattern and, surprisingly, gene length shape codon usage in Caenorhabditis, Drosophila, and Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96: 4482–4487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engelberg-Kulka H., 1981. UGA suppression by normal tRNA Trp in Escherichia coli: codon context effects. Nucleic Acids Res. 9: 983–991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felsenstein J., 1985. Phylogenies and the comparative method. Am. Nat. 125: 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Geller A. I., Rich A., 1980. A UGA termination suppression tRNATrp active in rabbit reticulocytes. Nature 283: 41–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guindon S., Gascuel O., 2003. A simple, fast, and accurate algorithm to estimate large phylogenies by maximum likelihood. Syst. Biol. 52: 696–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen F., Adamski F. M., Tate W. P., Kurland C. G., 1993. Release factor-dependent false stops are infrequent in Escherichia coli. J. Mol. Biol. 230: 41–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jungreis I., Lin M. F., Spokony R., Chan C. S., Negre N., et al. , 2011. Evidence of abundant stop codon readthrough in Drosophila and other metazoa. Genome Res. 21: 2096–2113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanaya S., Yamada Y., Kudo Y., Ikemura T., 1999. Studies of codon usage and tRNA genes of 18 unicellular organisms and quantification of Bacillus subtilis tRNAs: gene expression level and species-specific diversity of codon usage based on multivariate analysis. Gene 238: 143–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katoh K., Asimenos G., Toh H., 2009. Multiple alignment of DNA sequences with MAFFT. Methods Mol. Biol. 537: 39–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopelowitz J., Hampe C., Goldman R., Reches M., Engelberg-Kulka H., 1992. Influence of codon context on UGA suppression and readthrough. J. Mol. Biol. 225: 261–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korkmaz G., Holm M., Wiens T., Sanyal S., 2014. Comprehensive analysis of stop codon usage in bacteria and its correlation with release factor abundance. J. Biol. Chem. 289: 30334–30342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer E. B., Farabaugh P. J., 2007. The frequency of translational misreading errors in E. coli is largely determined by tRNA competition. RNA 13: 87–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manuvakhova M., Keeling K., Bedwell D. M., 2000. Aminoglycoside antibiotics mediate context-dependent suppression of termination codons in a mammalian translation system. RNA 6: 1044–1055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matheisl S., Berninghausen O., Becker T., Beckmann R., 2015. Structure of a human translation termination complex. Nucleic Acids Res. 43: 8615–8626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsugi J., Murao K., 1999. Search for a selenocysteine tRNA in Bacillus subtilis. Nucleic Acids Symp. Ser. 42: 209–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsugi J., Murao K., 2000. A study of the method to pick up a selenocysteine tRNA in Bacillus subtilis. Nucleic Acids Symp. Ser. 44: 149–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng S. Y., Hui J. O., Haniu M., Tsai L. B., 1995. Analysis of translational termination of recombinant human methionyl-neurotrophin 3 in Escherichia coli. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 211: 40–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller J. H., Albertini A. M., 1983. Effects of surrounding sequence on the suppression of nonsense codons. J. Mol. Biol. 164: 59–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milman G., Goldstein J., Scolnick E., Caskey T., 1969. Peptide chain termination. 3. Stimulation of in vitro termination. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 63: 183–190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura Y., Ito K., Isaksson L. A., 1996. Emerging understanding of translation termination. Cell 87: 147–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Namy O., Hatin I., Rousset J. P., 2001. Impact of the six nucleotides downstream of the stop codon on translation termination. EMBO Rep. 2: 787–793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson M., Ryden-Aulin M., 2003. Glutamine is incorporated at the nonsense codons UAG and UAA in a suppressor-free Escherichia coli strain. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1627: 1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker J., 1989. Errors and alternatives in reading the universal genetic code. Microbiol. Rev. 53: 273–298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Percudani R., Pavesi A., Ottonello S., 1997. Transfer RNA gene redundancy and translational selection in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Mol. Biol. 268: 322–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poole E. S., Brown C. M., Tate W. P., 1995. The identity of the base following the stop codon determines the efficiency of in vivo translational termination in Escherichia coli. EMBO J. 14: 151–158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poole E. S., Brimacombe R., Tate W. P., 1997. Decoding the translational termination signal: the polypeptide chain release factor in Escherichia coli crosslinks to the base following the stop codon. RNA 3: 974–982. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poole E. S., Major L. L., Mannering S. A., Tate W. P., 1998. Translational termination in Escherichia coli: three bases following the stop codon crosslink to release factor 2 and affect the decoding efficiency of UGA-containing signals. Nucleic Acids Res. 26: 954–960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prabhakaran R., Chithambaram S., Xia X., 2014. Aeromonas phages encode tRNAs for their overused codons. Int. J. Comput. Biol. Drug Des. 7: 168–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pundir S., Martin M. J., O’Donovan C., UniProt Consortium , 2016. UniProt tools. Curr. Protoc. Bioinformatics 53: 1.29.1–1.29.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy B., Leszyk J. D., Mangus D. A., Jacobson A., 2015. Nonsense suppression by near-cognate tRNAs employs alternative base pairing at codon positions 1 and 3. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 112: 3038–3043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy B., Friesen W. J., Tomizawa Y., Leszyk J. D., Zhuo J., et al. , 2016. Ataluren stimulates ribosomal selection of near-cognate tRNAs to promote nonsense suppression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 113: 12508–12513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J. F., Fan D. P., Brenner S., 1967. A strong suppressor specific for UGA. Nature 214: 452–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scolnick E., Tompkins R., Caskey T., Nirenberg M., 1968. Release factors differing in specificity for terminator codons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 61: 768–774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp P. M., Li W. H., 1987. The codon adaptation index–a measure of directional synonymous codon usage bias, and its potential applications. Nucleic Acids Res. 15: 1281–1295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strigini P., Brickman E., 1973. Analysis of specific misreading in Escherichia coli. J. Mol. Biol. 75: 659–672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svidritskiy E., Madireddy R., Korostelev A. A., 2016. Structural basis for translation termination on a pseudouridylated stop codon. J. Mol. Biol. 428: 2228–2236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K., Nei M., 1993. Estimation of the number of nucleotide substitutions in the control region of mitochondrial DNA in humans and chimpanzees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 10: 512–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang X., Zhu Y., Baker S. L., Bowler M. W., Chen B. J., et al. , 2016. Structural basis of suppression of host translation termination by Moloney Murine Leukemia Virus. Nat. Commun. 7: 12070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tate W. P., Poole E. S., Horsfield J. A., Mannering S. A., Brown C. M., et al. , 1995. Translational termination efficiency in both bacteria and mammals is regulated by the base following the stop codon. Biochem. Cell Biol. 73: 1095–1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tate W. P., Poole E. S., Dalphin M. E., Major L. L., Crawford D. J., et al. , 1996. The translational stop signal: codon with a context, or extended factor recognition element? Biochimie 78: 945–952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tate W. P., Mansell J. B., Mannering S. A., Irvine J. H., Major L. L., et al. , 1999. UGA: a dual signal for ‘stop’ and for recoding in protein synthesis. Biochemistry. Biokhimiia 64: 1342–1353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M., Herrmann C. J., Simonovic M., Szklarczyk D., von Mering C., 2015. Version 4.0 of PaxDb: protein abundance data, integrated across model organisms, tissues, and cell-lines. Proteomics 15: 3163–3168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei Y., Wang J., Xia X., 2016. Coevolution between stop codon usage and release factors in bacterial species. Mol. Biol. Evol. 33: 2357–2367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiner A. M., Weber K., 1973. A single UGA codon functions as a natural termination signal in the coliphage q beta coat protein cistron. J. Mol. Biol. 80: 837–855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia X., 2007. An improved implementation of codon adaptation index. Evol. Bioinform. Online 3: 53–58. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia X., 2013a Comparative Genomics. Springer, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Xia X., 2013b DAMBE5: a comprehensive software package for data analysis in molecular biology and evolution. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30: 1720–1728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia X., 2015. A major controversy in codon-anticodon adaptation resolved by a new codon usage index. Genetics 199: 573–579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia X., 2016. PhyPA: phylogenetic method with pairwise sequence alignment outperforms likelihood methods in phylogenetics involving highly diverged sequences. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 102: 331–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

File S1 contains a detailed description of File S2, File S3, File S4, and File S5, and provides additional details for the Materials and Methods. File S2 contains supplementary tables and figures discussed in this manuscript. HEG_RSCU and LEG_RSCU data are provided in File S3. File S4 contains ITE scores for all CDSs in 19 bacterial species. File S5 contains the associated data for Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5, and Figure 6.

Figure 2.

Relationship between +4 nucleotide usage and stop codons in E. coli and B. subtilis, contrasting between 100 highly- and 100 lowly-expressed genes (HEGs and LEGs, respectively) for each stop codon, respectively. Only nonpseudo and nonhypothetical genes are used.

Figure 3.

Relationship between genomic GC-content (proportion of G and C in the genome) and +4U usage measured as the proportion of +4U at the +4 site and designated by PU.UAA (A), PU.UAG (B), and PU.UGA (C), respectively, for the three stop codons in 19 bacterial species. 100 HEGs and 100 LEGs are used for each stop codon. Only nonpseudo, nonhypothetical genes are used. The four species with high GC-contents (> 58%) are indicated. HEGs, highly-expressed genes; LEGs, lowly-expressed genes.

Figure 4.

Relationship between ITE and usage of termination signals (stop codons and +4 bases), in E. coli (A), B. subtilis (B), and D. vulgaris (C). All nonpseudo, nonhypothetical CDSs were ranked by ITE and binned into 10 sets; the stop codon usage and +4 base usage was obtained in each set. Stop codon usage (PUAA, PUAG, and PUGA) is represented by solid lines; +4 base usage (PA, PC, PG, and PU) is represented by dotted lines. CDSs, coding sequences; ITE, Index of Translation Elongation.

Figure 5.

Relationship between stop codon and +4 base usage, represented with regression between the proportions of stop codons (PUAA, PUAG, and PUGA) and proportion of their +4U (PU.UAA, PU.UAG, and PU.UGA), and shown in (A), (B), and (C), respectively. Data from all 30S and 50S ribosomal protein genes in 25 bacterial species, excluding the data point if the stop codon usage is zero.

Figure 6.

Relationship between nc_tRNA abundance and +4U usage, represented by linear regression between 100 UAA-ending HEGs (highest ITE scores) and abundance of UAA nc_tRNAs with a single mismatch at (A) the first stop codon site, (B) the second stop codon site, (C) the third stop codon site, and (D) the first stop codon site, omitting tRNAGln, 5′-TTG-3′, in 19 bacterial species. CDSs, coding sequences; HEGs, highly-expressed genes; ITE, Index of Translation Elongation; nc_tRNA, near-cognate tRNA; tRNA, transfer RNA.