Abstract

In meiosis I, chromosomes become paired with their homologous partners and then are pulled toward opposite poles of the spindle. In the budding yeast, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, in early meiotic prophase, centromeres are observed to associate in pairs in a homology-independent manner; a process called centromere coupling. Later, as homologous chromosomes align, their centromeres associate in a process called centromere pairing. The synaptonemal complex protein Zip1 is necessary for both types of centromere association. We aimed to test the role of centromere coupling in modulating recombination at centromeres, and to test whether the two types of centromere associations depend upon the same sets of genes. The zip1-S75E mutation, which blocks centromere coupling but no other known functions of Zip1, was used to show that in the absence of centromere coupling, centromere-proximal recombination was unchanged. Further, this mutation did not diminish centromere pairing, demonstrating that these two processes have different genetic requirements. In addition, we tested other synaptonemal complex components, Ecm11 and Zip4, for their contributions to centromere pairing. ECM11 was dispensable for centromere pairing and segregation of achiasmate partner chromosomes; while ZIP4 was not required for centromere pairing during pachytene, but was required for proper segregation of achiasmate chromosomes. These findings help differentiate the two mechanisms that allow centromeres to interact in meiotic prophase, and illustrate that centromere pairing, which was previously shown to be necessary to ensure disjunction of achiasmate chromosomes, is not sufficient for ensuring their disjunction.

Keywords: Zip1, Zip4, centromere pairing, chromosome segregation, meiosis, synaptonemal complex

ACCURATE chromosome segregation in meiosis is important for preservation of the genome of an organism through multiple generations. In meiosis I, the cell is presented with a unique challenge in which homologous chromosomes must segregate from one another. This is followed by a mitosis-like segregation of the sister chromatids in meiosis II. In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, chromosomes interact with other chromosomes in meiosis I in four defined ways that will be introduced here: crossing over, centromere coupling, synaptonemal complex (SC) formation, and centromere pairing (reviewed in Kurdzo and Dawson 2015).

During meiotic prophase, homologous chromosome partners go through a series of events that culminate in the formation of crossovers between the homologous partners. In early prophase, double-strand breaks (DSBs) in the DNA are created by the endonuclease Spo11 (Keeney et al. 1997), homologous partners align, and a proteinaceous structure called the SC assembles along the axes of the homologs (reviewed in Kurdzo and Dawson 2015). The SC is comprised of two axial elements that run along the axes of each homolog and a central region that joins the axial elements together along their length. Repair of the DSBs by homologous recombination is critical for the formation of crossovers that, together with sister chromatid cohesion, serves to tether homologous partners together as they go through the process of attaching to the meiotic spindle (Keeney et al. 1997; Celerin et al. 2000).

Coincident with the formation of DSBs, centromeres undergo a period of pairwise associations that are homology independent and are referred to as centromere coupling (Tsubouchi and Roeder 2005; Obeso and Dawson 2010). Similar coupling or clustering of centromeres, or regions of pericentric heterochromatin, have been observed in a number of organisms, including onion (Church and Moens 1976), wheat (Bennett 1979; Martínez-Pérez et al. 1999), rice (Prieto et al. 2004), fission yeast (Ding et al. 2004; Tsubouchi and Roeder 2005; Obeso and Dawson 2010), maize (Zhang et al. 2013), and mouse (Scherthan et al. 1996; Takada et al. 2011). The reason behind this centromere coupling or clustering remains unclear, but recent studies in yeast suggest the chromosomes show a length-dependent preference for partner choice during centromere coupling, which may improve the efficiency of homologous pairing later in meiosis (Lefrancois et al. 2016).

As the chromosomes begin to synapse with their homologs, the centromeres seem to transition individually from nonhomologous coupling to pairing with their homologous centromere, as there is never a time in wild-type (WT) cells when all the centromeres are fully dispersed between the coupling and pairing stages (Obeso and Dawson 2010). When the homologous partners are fully synapsed (pachytene stage), remaining pairs of natural or artificial chromosomes that have failed to recombine (achiasmate partners) can be seen to pair at their centromeres (called centromere pairing) (Kemp et al. 2004; Gladstone et al. 2009; Newnham et al. 2010).

As the cells transition out of pachytene, the SC largely disassembles to reveal a small stretch of Zip1 left behind at the centromeres; suggesting that, like achiasmate partners, the chiasmate homologous chromosomes are also joined at their centromeres in pachytene. This type of pairing has been observed in yeast (Kemp et al. 2004; Gladstone et al. 2009; Newnham et al. 2010), but similar centromere-centromere interactions in late prophase (after SC disassembly) have also been observed in Drosophila (Dernburg et al. 1996; Takeo et al. 2011), fission yeast (Davis and Smith 2003; Ding et al. 2004), and mouse spermatocytes (Bisig et al. 2012; Qiao et al. 2012). Centromere pairing has been proposed to serve as an alternative means to tether partners that have failed to become joined by chiasmata (Dawson et al. 1986), and has been shown in genetic experiments to promote the biorientation of homologous chiasmate partners on the spindle (Gladstone et al. 2009).

The genes that are necessary for centromere coupling and pairing remain largely undefined. When centromere coupling was first discovered, it became clear that the protein Zip1 was necessary to tack the two centromeres together (Tsubouchi and Roeder 2005). Zip1 is a component of the transverse filament of the central region of the SC in budding yeast (Sym et al. 1993; reviewed in Kurdzo and Dawson 2015). Cohesin was found to be necessary for coupling as well, but this might be because faulty cohesin leads to a lack of correct Zip1 localization (Chuong and Dawson 2010). Zip1 is a member of the ZMM group of proteins (Zip1, Zip2, Zip3, Zip4, Mer3, Msh4, Msh5, and Spo16), also known as the synapsis initiation complex, that are required for SC assembly (Chua and Roeder 1998; Agarwal and Roeder 2000; Novak et al. 2001; Borner et al. 2004; Fung et al. 2004; Jessop et al. 2006; Shinohara et al. 2008). ZIP2 and ZIP3 are dispensable for centromere coupling, as is RED1, which encodes an axial element protein (Chuong and Dawson 2010). ECM11 and GMC2, which encode SC central element proteins in budding yeast, were also found to be unnecessary for coupling to occur (Humphryes et al. 2013). DSBs and the signaling mechanisms they trigger are not necessary for centromere coupling, because coupling occurs in mutants lacking SPO11 (Tsubouchi and Roeder 2005; Obeso and Dawson 2010). Exactly what is required for coupling besides ZIP1 and REC8 remains to be elucidated.

It is not clear at the mechanistic level how centromere coupling and pairing differ from one another besides their timeline in prophase. It has been hypothesized that coupling and pairing could result from the same mechanism, as they both require ZIP1, but this has not been formally tested. The centromere pairing (but not centromere coupling) has a partial dependence on ZIP2, ZIP3, or ZIP4, which could suggest a mechanistic difference (Gladstone et al. 2009; Newnham et al. 2010). Alternatively, these proteins may affect centromere pairing indirectly by affecting the availability of Zip1 for centromere pairing in late prophase, but not affect centromere coupling before SC assembly has begun.

Also unclear is the role, if any, that centromere coupling provides to the cell. It has been proposed that coupling nonhomologous centromeres together could provide a means to sequester homologous centromeres away from each other, preventing the formation of crossovers near the centromeres (Obeso and Dawson 2010). By this model, nonhomologous coupling would force centromere-proximal meiotic DSBs to be repaired from sister chromatids. Yeast and many other organisms exhibit repression of crossing over around centromeres and such crossovers have been shown to predispose chromosomes to higher rates of meiotic chromosome segregation errors (Koehler et al. 1996; Lamb et al. 1997; Rockmill et al. 2006; reviewed in Hassold and Hunt 2001).

The experiments here take advantage of a phosphomimetic mutation of ZIP1, zip1-S75E, that has been identified as a separation-of-function allele (Falk et al. 2010). Serine 75 was identified as a target of the kinase, Mec1 (ATR), in response to DSBs, and its phosphorylation promotes additional phosphorylation of Zip1, presumably by other kinases. Cells expressing the zip1-S75E allele appeared WT for ZIP1-related functions, such as recombination and SC assembly, but exhibited a severe defect in centromere coupling (Falk et al. 2010). Here, we take advantage of the zip1-S75E allele and mutations in other genes related to SC function to explore the role of centromere coupling and the requirements for centromere coupling and centromere pairing. The results demonstrate that centromere coupling does not measurably influence centromere-proximal recombination, and that centromere coupling and centromere pairing operate by nonidentical molecular mechanisms that both require the protein Zip1.

Materials and Methods

Yeast strains and culture conditions

Genotypes of the strains used in this study are listed in Supplemental Material, Table S1. Strains are isogenic derivatives of a rapidly sporulating diploid strain that is formed by mating haploids from lines called X and Y, which are primarily of S288C and W303 ancestry. These strains were derived in the Rochelle Easton Esposito laboratory (Dresser et al. 1994). We used standard yeast media and culture techniques (Burke et al. 2000). To induce meiosis, cells were grown in YPAcetate to 3–4 × 107 cells/ml, then shifted to 1% potassium acetate at 108 cells/ml.

Strain construction

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based methods were used to create complete deletions of open reading frames and epitope-tagged versions of genes (Longtine et al. 1998; Janke et al. 2004). Some deletions were created by using PCR to amplify gene deletion-kanMX4 insertions from the gene-deletion collection (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), and these products were then used for transformations. The PCYC1-lacI-GFP-LYS2 cassette was inserted in the LYS2 locus as part of pLL1. The PDMC1-lacI-GFP-LYS2 cassette was inserted in the LYS2 locus as part of pMDE798, a gift from Mike Dresser. The plasmid ptetR-tdTomato-LEU2 (a gift from Zachariae laboratory), containing the tdTomato gene fused to the 3′ end of the tetR coding sequence under the control of the URA3 promoter and with ADH1 transcriptional terminator at the 3′ end of the fusion gene, was inserted at URA3. The plasmid pD212 targeted a cassette (∼10 kb) of 256 tet operon operator (tetO) repeats to CEN3, coordinates 113,101–113,583. The plasmid pD214 targeted 256 lac operon operator (lacO) repeats to CEN3, coordinates 113,101–113,583 (Straight et al. 1996; Michaelis et al. 1997). The plasmid pMNS25 targeted 256 lacO repeats to CEN4, coordinates 447,580–448,580; the plasmid pELK20 targeted 256 tetO repeats to CEN4, coordinates 447,580–448,580. Correct integration was confirmed genetically.

A zip1-S75E point mutant was built by a modified gene two-step replacement method. Briefly, WT ZIP1 was amplified using high-fidelity fusion PCR with primer sets containing the GAA codon instead of AGT at ZIP1 position 222–225 of the ZIP1 ORF, creating a ZIP1 DNA coding for glutamic acid instead of a serine at position 75. This fragment was cloned in the PCR-Blunt II TOPO vector (Invitrogen). Yeast cells, in which the ZIP1 gene was previously replaced by URA3, were transformed with the restriction-enzyme digested plasmid DNA and colonies selected on plates containing 5-fluoro-orotic acid (Boeke et al. 1984). The sequence of the zip1-S75E gene was determined and no additional mutations were present. A hygromycin resistance gene (hphMX4) marker was then added downstream of zip1-S75E in the 3′ untranslated region (between 2721 and 2820 bp downstream of the ZIP1 start codon) using PCR-based standard techniques (Janke et al. 2004). The hygromycin resistance gene position was confirmed by PCR.

Microscopy

Images were collected using a Carl Zeiss (Thornwood, NY) AxioImager microscope with band-pass emission filters, a Roper HQ2 charge coupled device, and AxioVision software or, where noted, a Deltavision OMX-SR structured illumination imaging station.

Meiotic chromosome spreads

Two chromosome-spreading methods were used. For the experiments in Figure 1, Figure 2, and Figure 3, chromosome spreads were prepared from cells harvested 5 hr (Figure 1) or 7 hr (Figure 2 and Figure 3) after induction of sporulation at 30°, and meiotic nuclear spreads were prepared according to Dresser and Giroux (1988) with minor modifications. Cells were spheroplasted using 20 mg/ml zymolyase-100T for ∼30 min. Spheroplasts were briefly suspended in MEM [100 mM 2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid, 10 mM EDTA, 500 µM MgCl2] containing 1 mM phenylmethane sulfonyl fluoride, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde plus 0.1% Tween 20, and spread onto poly-L-lysine-coated slides (Fisherbrand Superfrost Plus). Slides were blocked with 4% nonfat dry milk in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) for at least 30 min, and incubated overnight at 4° with primary antibodies. Primary antibodies were mouse anti-Zip1 (used at 1:1000 dilution; gift from S. Rankin), rabbit anti-Zip1 (used at 1:1000 dilution, y-300 SC-33733; Santa Cruz), rabbit anti-MYC (1:400, A190–105A; Bethyl Laboratories), mouse anti-MYC (used at 1:1000 dilution; gift from S. Rankin), chicken anti-GFP (used at 1:500 dilution, AB16901; Millipore, Bedford, MA), rabbit anti-DsRed (used at 1:1000–1:2000 dilution, 632496; Clontech), and rabbit anti-RFP (1:500, 600-401-379; Thermo Scientific). Secondary antibodies were Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-chicken IgG (used at 1:1200 dilution), Alexa Fluor 568-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (used at 1:1000 dilution), Alexa Fluor 647 conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (used at 1:1200 dilution), and Alexa Fluor 568-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (used at 1:1000 dilution).

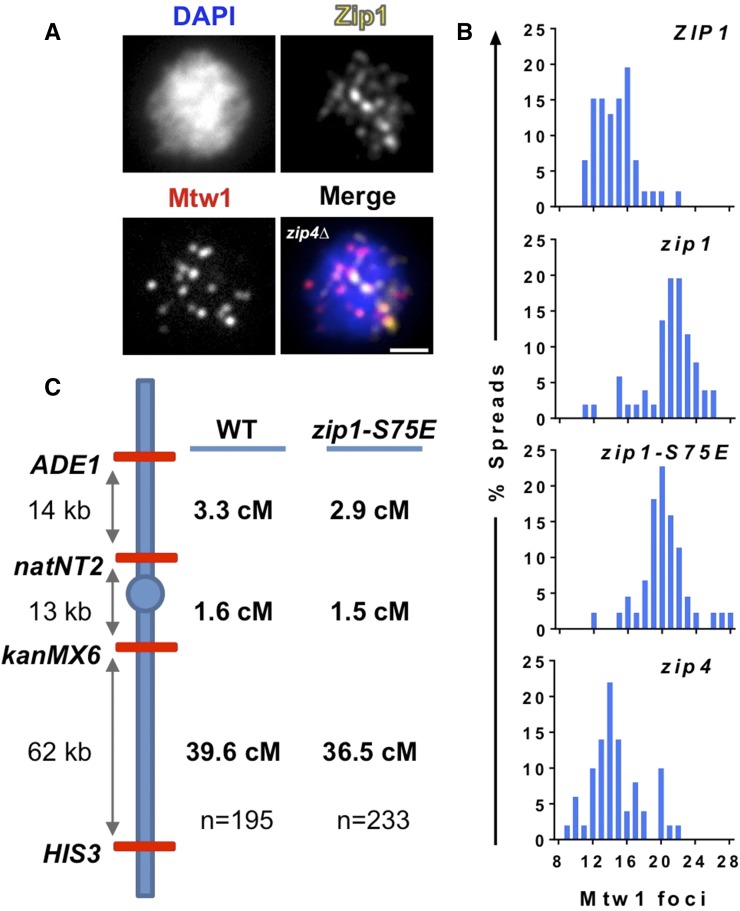

Figure 1.

Centromere coupling does not repress centromere-proximal crossing over. (A and B) The zip1-S75E mutation diminishes centromere coupling. (A) Centromere coupling was monitored by creating chromosome spreads that were assayed for the number of Mtw1 foci (the representative spread that is shown is from the zip4Δ spo11Δ mutant strain; DEK330). Scale bar equals 2 μm. (B) Histograms show the number of Mtw1 foci for WT (ZIP1/zip1Δ spo11Δ/spo11Δ; DDO133), zip1Δ/zip1Δ spo11Δ/spo11Δ (DDO134), zip1-S75E//zip1Δ spo11Δ/spo11Δ (DDO132), and zip4Δ/zip4Δ spo11Δ/spo11Δ (DEK330). Averages, 95% C.I., and the number of cells scored for each strain are as follows: ZIP1: 14.6, 13.9–15.3, 46; zip1Δ: 20.8, 19.9–21.7, 51; zip1-S75E: 20.2, 19.4–21.1, 44; zip4Δ: 14.8, 13.9–15.7, 50. The difference in coupling between the ZIP1/zip1 strain and the zip1-S75E and zip4 strains was significant, as was the difference between the zip4 strain and the zip1-S75E and zip1 strains (Kruskal–Wallis; P < 0.0001; Dunn’s post hoc test for these comparisons P < 0.0001); the difference between ZIP1/zip1 and zip4 was not significant, nor was the difference between zip1-S75E and zip1. (C) Mapping crossing over in zip1-S75E strains. Diploid strains were constructed to allow the assessment of crossing over on chromosome I in WT (ZIP1/zip1Δ; DDO140 and DDO145) and zip1-S75E (zip1-S75E1/zip1Δ; DDO143) strains. n, the number of four spore viable tetrads that were analyzed.

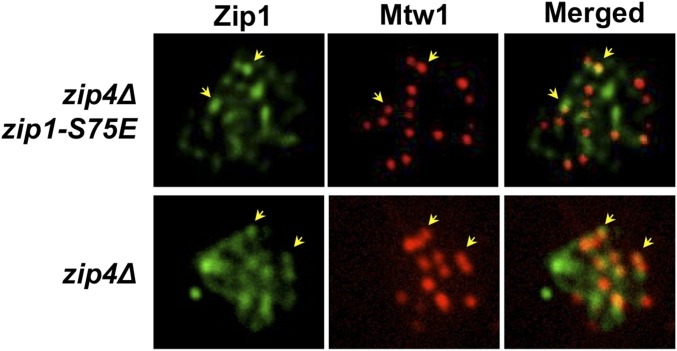

Figure 2.

Zip1-S75E localizes to centromeres. Colocalization of Zip1 and Mtw1 staining on zip4Δ (DDO172) and zip4Δ zip1-S75E double mutants (DDO182). Cells were induced to sporulate in liquid medium, and samples were harvested 7 hr later for the preparation of chromosome spreads. Yellow arrowheads indicate examples of colocalization of Zip1 and Mtw1 immunofluorescence. The level of Mtw1/Zip1 colocalization in both zip4 (32 spreads, 438 Mtw1 foci) and zip4 zip1-S75E (24 spreads, 356 Mtw1 foci) strains was quantified and compared to the Mtw1/Zip1 overlap that was seen when the foci were randomized (see Materials and Methods for details).

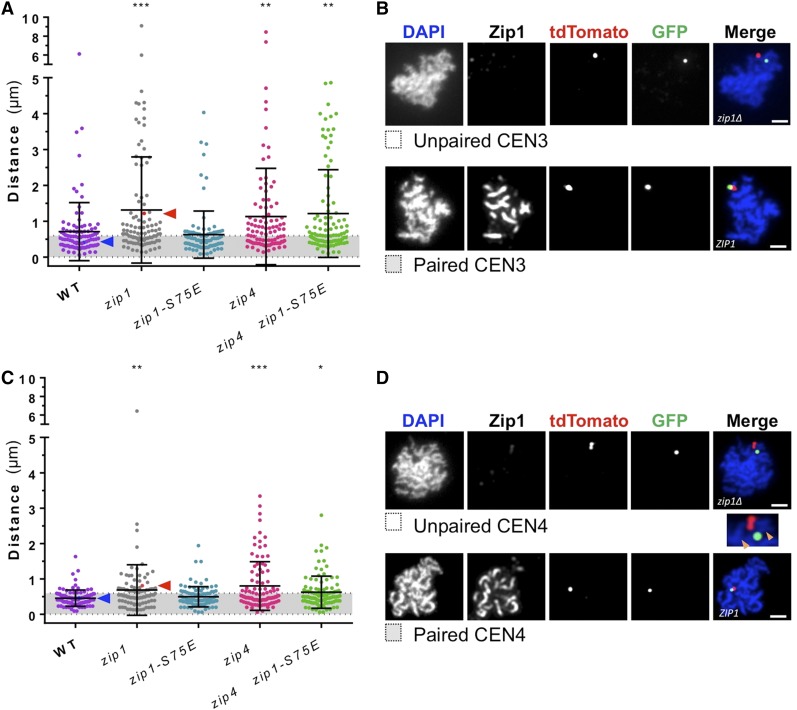

Figure 3.

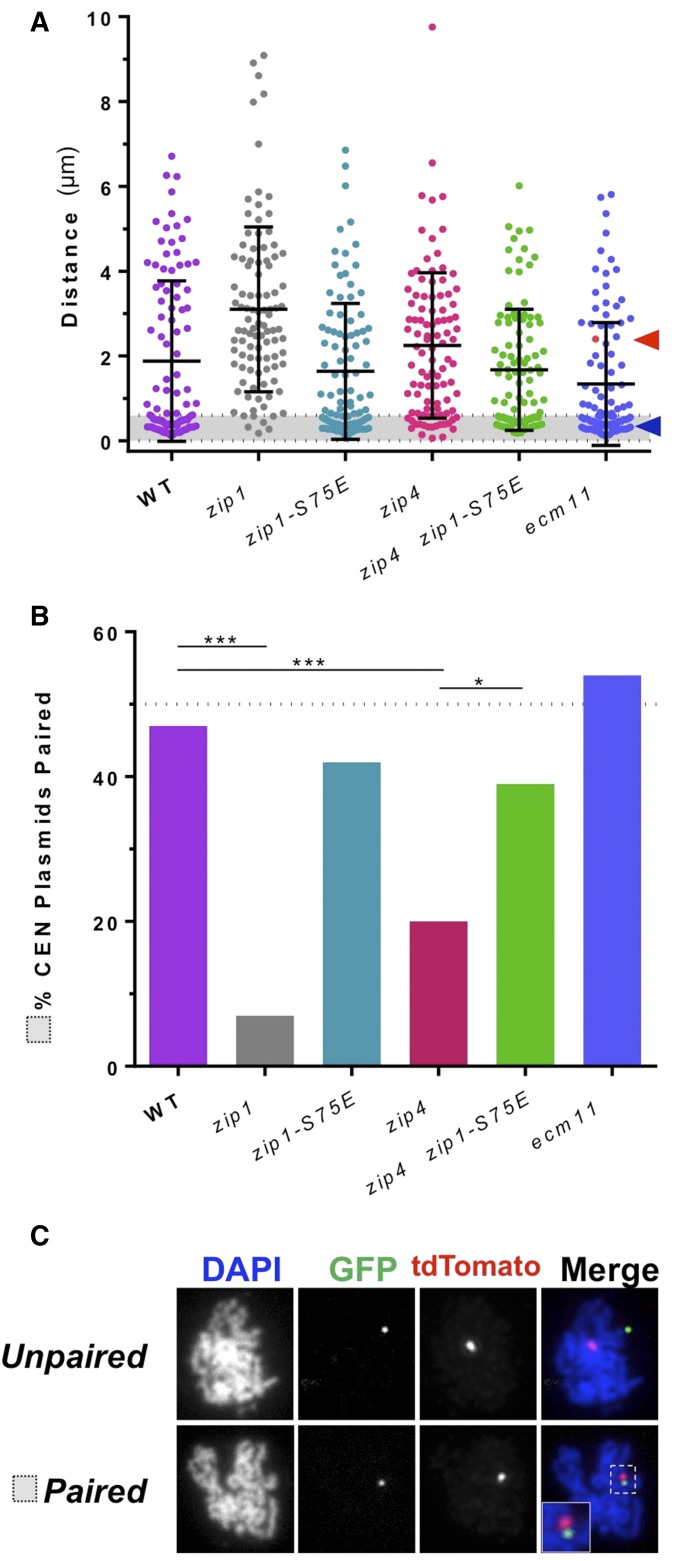

The zip1-S75E mutation does not affect pairing of homologous pericentric regions at pachytene. (A and B) zip4Δ affects pairing between peri-centromeric regions of chromosome III. Cells were induced to sporulate in liquid medium, and samples were taken at time of 5 hr for chromosome spreads. tdTomato and GFP foci, which localized to tet and lac operator repeats situated near the centromere of chromosome III (CEN3), were visualized using indirect immunofluorescence and the distance between foci was measured. (A) The measured distance between CEN3 foci. CEN pairing, as defined as <0.6-μm distance (gray shading). The observed pairing values for the strains tested were: 61% WT (median = 0.51 μm; DEK350, DEK360), 41% zip1∆ (median = 0.71 μm; DEK337, DEK361), 68% zip1-S75E (median = 0.46 μm; DEK357, DEK362), 46% zip4Δ (median = 0.70 μm; DEK338, DEK363), and 44% zip4∆ zip1-S75E double mutant (median = 0.63 μm; DEK339, DEK364); n = 100 spreads per genotype consisting of two separate experiments. The data points indicated by the red and blue arrowheads correspond to chromosome spreads shown in (B). See Figure S2 for a graphical representation of the centromere pairing data shown in (A). (B) Representative spreads with unpaired [zip1Δ, DEK361; 1.22 µm distance, red arrowhead and data point in (A)] and paired [WT, DEK360; 0.41 µm distance, blue arrowhead and data point in (A)] tdTomato and GFP foci are shown. Bar, 2 μm. (C) Centromere pairing (CEN4) was assessed by localization of tetR-tdTomato and GFP-lacI foci localized to tet and lac operator repeats respectively inserted adjacent to CEN4. CEN pairing, as defined as <0.6-μm distance (gray shading), was exhibited between 83% WT (median = 0.43 μm; DEK359, DEK365), 55% zip1Δ (median = 0.55 μm; DEK258, DEK370), 75% zip1-S75E (median = 0.41 μm; DEK353), 59% zip4Δ (median = 0.49 μm; DEK351, DEK368), and 63% zip4 zip1-S75E double mutant (median = 0.50 μm; DEK352, DEK369); n = 100 spreads per genotype consisting of two separate experiments. (D) Representative spreads used for the quantifications in (C) with unpaired [zip1Δ, DEK370; 0.81 µm distance, red arrowhead and data point in (C)] and paired [WT, DEK365; 0.45 µm distance, blue arrowhead and data point in (C)]. Orange arrowheads in inset indicate axial associations of chromosome IV pair that display no pairing. Bar, 2 μm. The errors bars in (A) and (C) represent mean and SD. Statistical comparisons were performed with Kruskal–Wallis; (A) P < 0.0001, (C) P = 0.0002; multiple comparisons to WT done by Dunn’s post hoc test *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001.

For the chromosome spreads for Figure 4, Figure 5, and Figure S1, cells were harvested 5 hr after induction of sporulation at 30° (Figure 4) or 13 hr after induction of sporulation at 23° (Figure 5). Chromosome spreads for Figure 4, Figure 5, and Figure S1 were prepared as described by Grubb et al. (2015) with the following modifications. After chromosome spreads were created and dried overnight, the slides were rinsed gently with 0.4% Photoflo. The slide was then incubated with PBS/4% milk at room temperature for 30 min in a wet chamber. Milk was drained off of the slide, and primary antibody diluted in PBS/4% milk was incubated on the slide overnight at 4°. A control slide with PBS/4% milk was used for each experiment. The following day, the slides were washed in PBS, and incubated with secondary antibody diluted in PBS/4% milk for 2 hr in a wet chamber at room temperature. The slides were gently washed in PBS. Then, 1 µg/ml of 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) was added to each slide and allowed to incubate at room temperature for 10 min. Slides were then washed gently in PBS and 0.4% Photoflo, then allowed to dry completely before a coverslip was mounted. Antibodies used for this spread protocol match those of the spread protocol used for Figure 1 and Figure 3.

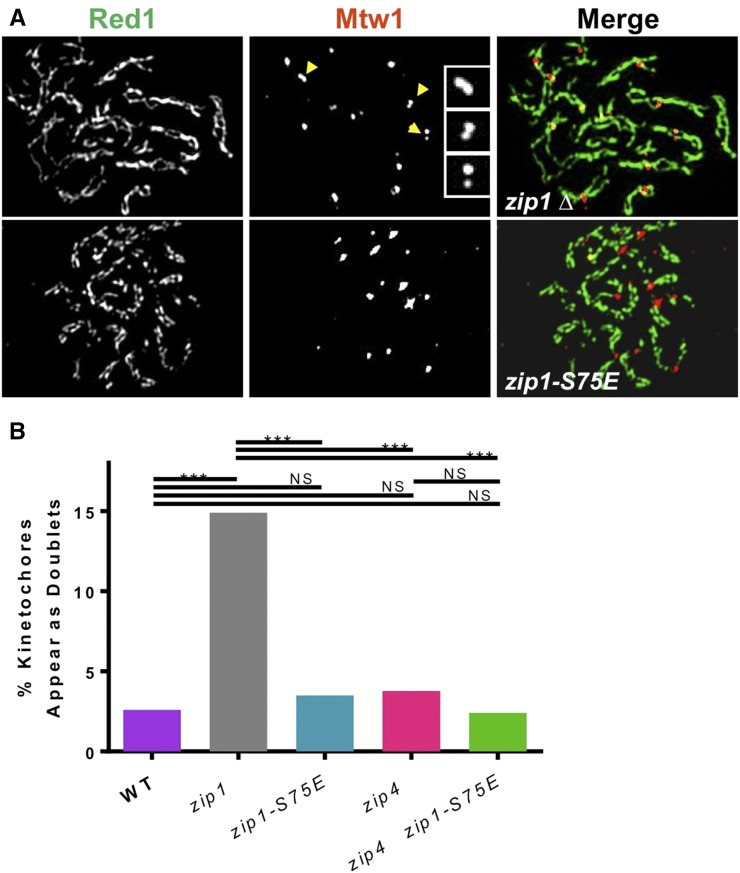

Figure 4.

Zip1 promotes pairing of chromosomal centromeres. The pairing of centromeres of homologous chromosomes was monitored on chromosome spreads from pachytene cells. Chromosome axes were stained with anti-Red1 antibodies (green) and kinetochores were stained with anti-MYC antibodies (red). (A) Examples of spreads from zip1Δ and zip1-S75E strains are shown. Yellow arrowheads indicate examples of separated Mtw1 foci associated with parallel Red1 axes that were scored as “doublets.” The indicated doublets are shown in magnified images in the insets. (B) Histogram of the percentage of Mtw1 foci scored as doublets in five different strains. n, total Mtw1 foci scored. Strains: WT (ZIP1), DHC349, n = 114; zip1Δ, DHC350, n = 179; zip1-S75E, DHC351, n = 159; zip4Δ, DHC352, n = 177; zip4Δ zip1-S75E, DHC353, n = 122. ***P ≤ 0.001. Raw P-values can be found in Table S3.

Figure 5.

Zip1-S75E promotes centromere pairing of CEN plasmids. (A) Centromere pairing of CEN plasmids was assessed by monitoring the pairing of tetR-tdTomato and lacI-GFP foci localized to tet and lac operator repeats respectively inserted into a plasmid that contains 5.1 kb of CEN3 sequence. Chromosome spreads were prepared from samples taken at time 13 hr after transfers of cultures to sporulation medium and sporulated at 23°. tdTomato and GFP foci were visualized using indirect immunofluorescence and pairing, as defined as <0.6-μm distance (gray shading), and was assessed to occur between 47% WT (median = 0.65 μm, DEK303, DEK323), 7% zip1Δ (median = 2.7 µm, DEK320, DEK325), 42% zip1-S75E (median = 0.87 µm, DEK267, DEK324), 20% zip4Δ (median = 2.1 µm, DEK304, DEK326), 39% zip4Δ zip1-S75E double mutant (median = 1.2 µm, DEK335), and 54% ecm11Δ (median = 0.57 µm, DEK321, DEK327). Sample size n = 100 cells from at least two experiments. Statistical comparisons were performed with Kruskal–Wallis, P < 0.0001; multiple comparisons to WT done by Dunn’s post hoc test ****P ≤ 0.0001. (B) Histogram of percentage of pairing between CEN plasmids, from gray shading in (A). Statistical comparisons were performed with Fisher’s exact test to compare all genotypes to WT, and zip4Δ to both zip1Δ and zip4Δ zip1-S75E double mutant. Bonferroni’s correction was used to adjust for the number of comparisons: *P ≤ 0.05, ***P ≤ 0.001. Raw P-values can be found in Table S4. (C) Representative spreads with unpaired [2.4 µm distance; red arrowhead and data point in (A); DEK321] and paired [0.38 µm distance; navy blue arrowhead in (A); DEK321] tdTomato and GFP foci are shown.

Coupling assay

Centromere coupling in Figure 1 was monitored as described previously (Obeso and Dawson 2010). Mtw1 (an inner kinetochore protein) foci were quantified in spreads that were ≥5.4 µm in diameter to ensure centromeres were spread enough to assay. Centromere coupling would theoretically yield 16 kinetochore (Mtw1) foci, while absence of coupling would yield 32 kinetochore foci. All strains were spo11∆/spo11∆ to block progression beyond the coupling stage (Falk et al. 2010; Obeso and Dawson 2010).

Genetic mapping

Diploid strains heterozygous for several markers located at different positions on chromosome I were created by PCR-based methods. Briefly, haploids; in which ADE1 has been replaced by LYS2 at position 169,375 of chromosome I (Chuong and Dawson 2010), kanMX4 has been inserted at position 143,400 (5 kb to the left of CEN1), the natNT2 gene has been inserted at position 156,285 (adjacent to SWD1, 8 kb to the right of CEN1), and HIS5 has been added at position 80,587 (after the MTW1 gene); were mated with strains WT for ADE1, with the TRP1 gene instead of HIS5 added after the MTW1 gene and without the kanMX4 and natNT2 insertions. Tetrads were dissected and the spore phenotypes were tested by replica plating onto selective media. The percentage of crossing over between two markers was determined by scoring the percentage of tetratypes (T) and nonparental ditypes (NPD) among all four spore viable tetrads (total). The distance in centimorgans was estimated as 100 × (0.5T + 3NPD)/total (see Perkins 1949 and Amberg et al. 2005 for descriptions of mapping functions).

Power analysis of genetic mapping experiment

With a lack of significance between incidents of recombination in WT and zip1-S75E cells within intervals that included a 13-kb region which included CEN1 and 14 kb directly adjacent, we wanted to test our power. Using G*Power, we performed both post hoc and a priori tests to judge current power and the necessary number of tetrads to dissect to achieve significance. The outcomes of these tests can be found in Table S2.

Pachytene pairing assays

Centromere pairing in pachytene for Figure 3, Figure 5, and Figure S1 was assessed using published methods (Gladstone et al. 2009) in which lacO and tetO arrays were either inserted adjacent to the centromeres of two chromosomes or two plasmids. These cells expressed a GFP-lacI gene fusion under the control of a DMC1 meiotic promoter, and a tetR-tdTomato gene fusion under the control of the URA3 promoter. This produced fluorescent foci at the operator arrays. Chromosome spreads were prepared and indirect immunofluorescence was used to identify the hybrid proteins and Zip1 localization. Only cells that exhibited “ropey” DAPI staining were scored in this assay, and they were disqualified for assessment if there was more than one GFP focus or more than one tdTomato focus. In these cells, the distance between the center of the green focus and the center of the red focus was measured using AxioVision software. Foci within 0.6 µm were scored as paired, and those separated by 0.6 µm or a larger distance were scored as unpaired.

To monitor pairing of kinetochores (Mtw1-13×Myc), chromosome spreads were prepared as in Figure 3 (see above). Spreads were stained for Mtw1-13×MYC (mouse anti-MYC, Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, 1:200) and Red1 (guinea pig anti-Red1, from Marta Kasperzyk, 1:1000) using methods described above. Secondary antibodies were Alexa Fluor 568 goat anti-mouse (Invitrogen, 1:1000) and Alexa Fluor 488 donkey anti-guinea pig (Jackson ImmunoResearch, 1:800). Z-series images were collected with a Deltavision OMX in the OMRF Imaging Core. Images were then deconvolved and reconstructed using softWoRx. Presented images (Figure 4) are a quick projection generated using softWoRx. Spreads with continuous Red1 staining were identified and these spreads were scored for whether the Mtw1-13×MYC foci were singlets or doublets by evaluating the projected images and by scrolling through the deconvolved Z-series. Foci were scored as doublets if they could be resolved as two separated foci that were associated with the same pair of Red1 axes.

Mtw1 colocalization with Zip1-S75E

To determine whether Mtw1 foci showed a significant overlap with Zip1-S75E foci, images were cropped to contain the DAPI-staining region. ImageJ software was used to define the perimeters of each Zip1 focus. Mtw1 foci that overlapped edges of the Zip1 foci were scored as colocalized. The Zip1 images were then flipped 180° and Mtw1 colocalization was again scored. A statistical analysis was then performed to determine whether actual colocalization was significantly greater than the randomized (flipped) control. A paired t-test was used to compare the number of Mtw1 foci that colocalized within the actual vs. flipped Zip1 foci.

Meiosis I nondisjunction assay

Nondisjunction frequencies of CEN plasmids were determined in a manner similar to how homeologous chromosomes were assayed in a previously published work (Gladstone et al. 2009). Diploid cells were induced to enter meiosis at 23° (because zip1, zip4, and ecm11 mutants in this strain background arrest in pachytene at 30°) and cells were harvested at 24 hr (when many anaphase I cells are present). Harvested cells were either assayed fresh, or were frozen in 15% glycerol and 1% potassium acetate until the time at which they were assayed. Preparation for assaying the cells included staining the cells with DAPI and then mounting the cells on agarose pads for viewing (Kim et al. 2013). Anaphase I cells were identified by the presence of two DAPI masses on either side of elongated cells, indicating that the chromosomes had segregated. To avoid scoring cells with duplicated or lost CEN plasmids, only cells with one GFP focus and one tdTomato focus were assayed. A Z-series of each cell was collected to assess whether CEN plasmids had disjoined or nondisjoined.

The representative images in Figure 6B were edited using AxioVision software, using a constrained iterative deconvolution algorithm and a wavelet-based extended focus algorithm to collapse the Z-stacks into a single two-dimensional image.

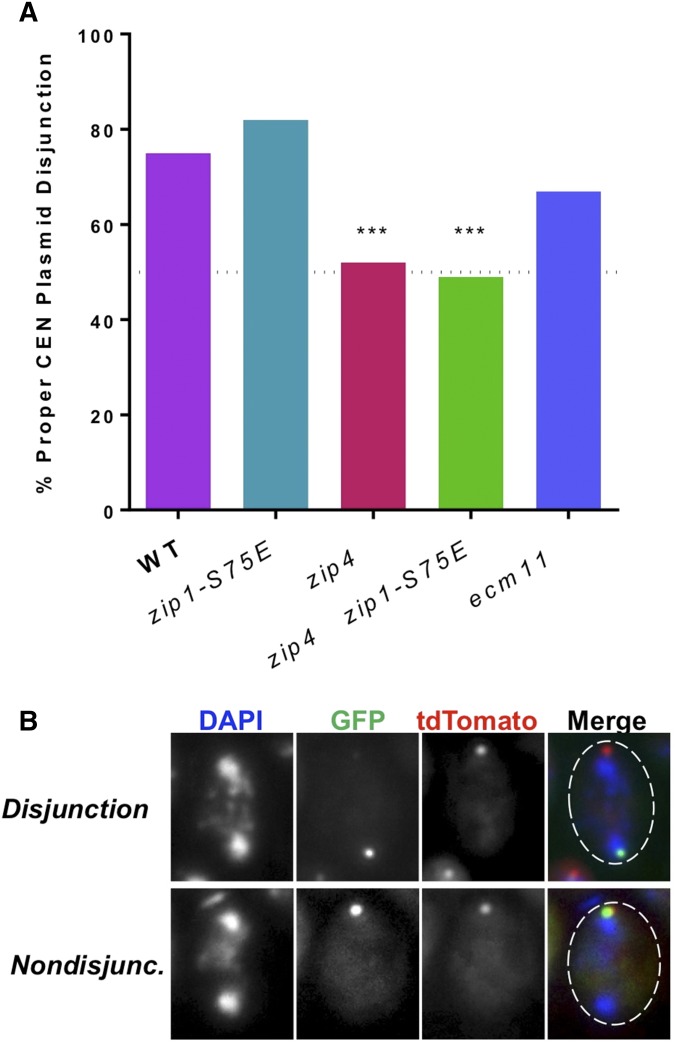

Figure 6.

CEN plasmids disjunction requires ZIP1 and ZIP4. (A) Segregation of CEN plasmids in anaphase I was assessed by monitoring the tetR-tdTomato and lacI-GFP foci localized to tet and lac operator repeats on the plasmids. Cells from meiotic cultures (23°, time = 26 hr post meiotic induction) were stained with DAPI and scored for segregation of CEN plasmid. (A) shows the percentage of spreads with correctly segregated CEN plasmids. Disjunction was assessed to occur in 75% WT (DEK303, DEK323), 82% zip1-S75E (DEK267, 324), 52% zip4Δ (DEK304, DEK326), 49% zip1-S75E zip4Δ (DEK335), and 67% ecm11Δ (DEK321, DEK327). Sample size represents n = 150 cells, split between three experiments. Statistical comparisons were performed with Fisher’s exact test to compare all genotypes to WT. Bonferroni’s correction was used to adjust for the number of comparisons; ***P ≤ 0.001. Raw P-values can be found in Table S5. (B) Representative binucleate cells with disjoined and nondisjoined CEN plasmids. Both sample photos are from WT cells (DEK323).

Statistics

GraphPad Prism software was used for all statistical calculations. Continuous data were tested for normality and compared using the Kruskal–Wallis test. Dunn’s post hoc test was done for direct comparisons between genotypes. Experiments that required 180° rotation of a fluorescent channel to test overlap employed student’s paired t-test (Wilcoxon signed-rank test). Categorical data were compared using Fisher’s exact test and Bonferroni’s correction was used to adjust the P-value for multiple comparisons where we have noted. Raw P-values can be found in Table S3, Table S4, and Table S5.

Data availability

Strains and plasmids are available upon request. Table S1 includes names and genotypes of each strain used in this work.

Results

Centromere coupling does not repress centromere-proximal crossing over

The characterization of the zip1-S75E separation-of-function allele (Falk et al. 2010) has made it possible to test the hypothesis that the coupling of centromeres with nonhomologous partners blocks recombination between homologous centromere regions. We first confirmed that the zip1-S75E allele has a coupling defect in our strain background like that previously shown by Falk et al. (2010). To ensure we were examining centromere coupling between nonhomologous chromosomes, and not centromere pairing that occurs later in prophase between centromeres of homologous chromosomes, we deleted SPO11 (Keeney et al. 1997) which prevents homologous centromere pairing (Falk et al. 2010; Obeso and Dawson 2010). We assayed centromere coupling by quantifying the number of Mtw1 (an inner kinetochore protein) foci using indirect immunofluorescence of a MYC-tagged version of Mtw1 5 hr after the induction of meiosis by transfer to a sporulation medium (Figure 1A). In this assay, each of the 32 chromosomes is comprised of two sister chromatids with a shared kinetochore, which appears as a single focus. If the centromeres of the 32 chromosomes form 16 couples, they appear as ∼16 foci (some foci may overlap or be undetectable) when visualized using conventional wide-field microscopy (Obeso and Dawson 2010; Tsubouchi and Roeder 2005). Our WT chromosome spreads, on average, showed ∼16 kinetochore foci (average 14.6 foci)—indicative of complete coupling, as do zip4 mutants (Figure 1B). At this stage of meiosis, Zip1 appears as dispersed foci of varying intensities (Figure 1A). As shown previously, many of these colocalize with or are adjacent to kinetochore foci, consistent with the requirement for Zip1 for efficient centromere coupling (Tsubouchi and Roeder 2005; Chuong and Dawson 2010; Falk et al. 2010; Obeso and Dawson 2010). The number of foci is significantly increased in zip1Δ mutants (average 20.8 foci). Note that in these assays the maximum unpaired number of kinetochore foci (32) is not typically observed (Tsubouchi and Roeder 2005; Chuong and Dawson 2010; Falk et al. 2010; Obeso and Dawson 2010). This may be because of some residual pairing capability in the zip1 mutants, or because some kinetochores are too faint to detect, or are obscured, or overlap one another in the chromosome spreads. There was no distinguishable difference between coupling in the zip1-S75E strain (average 20.2 foci) and zip1Δ mutants (Figure 1, legend). Thus, in our strain background, the zip1-S75E allele behaves as described previously (Falk et al. 2010) and appears as defective in coupling as a zip1 deletion mutation.

To test whether loss of coupling affected centromere-proximal crossing over, we integrated markers that would allow us to monitor crossing over in a region including the centromere as well as flanking intervals on the arms of chromosome I (Figure 1C). The genetic distance measured between the markers straddling the centromere in WT cells was 1.6 cM. The similarly sized adjacent arm interval was measured as 3.3 cM, consistent with repression of crossing over between homologous partners near the centromeres. The map distances exhibited by the zip1-S75E mutant were indistinguishable and not significantly different from those in the WT strain (Figure 1C and Figure S1). To assess whether we had examined an adequate number of tetrads to make conclusions based on our data, we performed a power analysis (Table S2), which assured us that our sample size was large enough to conclude there was no significant difference between centromere-proximal crossovers in WT and zip1-S75E cells. We conclude that absence of centromere coupling does not affect the level of crossover repression that occurs at the centromere, corroborating similar work recently published by Marston and colleagues (Vincenten et al. 2015).

The zip1-S75E allele is not defective in associations of homologous peri-centromeric regions during pachytene

Neither coupling nor pairing is dependent on the homology of the underlying DNA sequence near the centromere, but centromere pairing most often occurs between centromeres of homologous chromosomes because the homologous chromosomes are paired with one another during pachytene. The exception to this occurs when two nonhomologous chromosomes are left without homologous partners during pachytene. The centromere regions of these partners pair with one another, even if they are not homologous, and they segregate away from each other in anaphase I (Kemp et al. 2004; Gladstone et al. 2009; Newnham et al. 2010). The fact that both coupling and pairing of centromeres are Zip1 dependent and homology independent raises the question of whether they operate using the same mechanism, but at different times in the meiotic program. To address this question, we tested whether the zip1-S75E mutation ablates centromere-pairing interactions just as it does centromere coupling.

As a first test of whether the Zip1-S75E protein might promote centromere pairing, we determined whether it can localize to centromeres as the WT protein does (Figure 2). This was done in zip4-strain backgrounds, as these do not assemble a continuous SC; leaving discernable Zip1 foci of varying intensities, some of which colocalize with kinetochores (Tsubouchi et al. 2008). In this experiment, Zip1 and Zip1-S75E showed similar levels of localization with Mtw1 (51 and 59%, respectively), which were significantly greater than randomized controls (P < 0.0001).

Next we monitored the proximity of centromere regions using fluorescence microscopy in zip1-S75E mutants. We inserted linearized plasmids containing (∼10 kb) arrays of the bacterial lac operator or tet operator sequences ∼1 kb from the centromeres of homologous chromosomes, and expressed GFP-lacI or tetR-tdTomato to tag the centromere regions of the homologous partners (Straight et al. 1996; Michaelis et al. 1997). The centromeres of both a small (CEN3) and a large (CEN4) chromosome were tagged in this manner. Diploids with the tagged centromeres were induced to enter meiosis (sporulation), and at a time point (5 hr) corresponding to pachytene, cells were harvested and chromosome spreads were prepared (Grubb et al. 2015) and analyzed by indirect fluorescence microscopy. To assay centromere pairing in these cells, the distances between the centers of the fluorescent GFP and tdTomato foci were measured in pachytene cells, which were identified by the dense ropey appearance of the chromosomes when stained with DAPI (Figure 3A, representative photos in Figure 3B). For CEN3, WT cells showed a median separation of the dots of 0.51 µm, with ∼61% of the dots separated by 0.6 µm or less, which we defined as “paired” for the purposes of this assay. As a negative control, we used a zip1Δ strain, which exhibited a significantly elevated median of 0.71 µm and a drop to 41% of measurements scored as paired (Figure 3, A and B). The zip1-S75E mutant was indistinguishable from the WT strain (median 0.46 µm, 68% of centromeres paired). The higher level of centromere associations in the WT and zip1-S75E cells compared to the zip1Δ cells could be due to the formation of the SC in the pericentric region, keeping centromeres near one another; or due to centromere pairing, independent of SC formation. To test this, we assayed the effect of the zip1-S75E mutation in a zip4Δ background (Tsubouchi et al. 2008). The zip4 mutant resulted in a significant increase in median focus-to-focus distance compared to WT cells (median 0.70 µm, 46% paired), suggesting that at least a portion of the associations were due to the SC. The pairing in the zip4Δ zip1-S75E double mutant cells (median 0.63 µm, 44% paired) was indistinguishable from the zip4Δ mutants (Figure 3, A and B). Both mutants exhibited a level of pairing similar to that seen in zip1 null mutants. But the fact that pairing in the zip4Δ background [which eliminates the SC but not pairing (Tsubouchi et al. 2008)] is similar to the pairing exhibited in the zip1Δ mutation, which eliminates both the SC and pairing (Gladstone et al. 2009; Newnham et al. 2010), suggests that associations of peri-centromeric dots in WT and zip1-S75E spreads is mainly attributable to the SC, not centromere pairing.

A similar approach was taken to examine pairing of the pericentric region of the much larger chromosome IV and similar results were obtained. That is, zip1-S75E mutants were not significantly different from WT, while zip1Δ (median 0.55 µm, 55% paired), zip4Δ (median 0.49 µm, 59% paired), and zip4Δ zip1-S75E double mutants (median 0.50 µm, 63% paired) all exhibited significantly larger distances between the GFP and tdTomato foci than were seen in WT spreads (Figure 3C, representative photos in Figure 3D).

At both the chromosomal CEN3 and CEN4 regions, the association of GFP and tdTomato arrays that persists in the zip4Δ and zip1Δ strains (∼40–50%, Figure S2) is presumably promoted by the tethering of the homologous pericentric regions by adjacent crossovers, since in the absence of both ZIP1 and crossing over, homologous centromeres do not associate (Obeso and Dawson 2010). The persistent association of the pericentric regions even in zip1Δ mutants could be compromising our ability to monitor centromere pairing. In fact, our observation that zip1Δ and zip4Δ mutations similarly reduce peri-centromeric associations of 10-kb arrays inserted adjacent to the centromere is in contrast to the findings found by Tsubouchi et al. (2008), wherein a zip4Δ mutant exhibited paired kinetochores late in prophase, as assayed by Ctf19 immunofluorescence, while this pairing vanished in zip1Δ strains.

The zip1-S75E allele promotes pairing of homologous centromeres during pachytene

To directly test whether the Zip1-S75E protein can promote pairing of centromere regions, we used an assay similar to that described by Tsubouchi et al. (2008), except that structured illumination microscopy was used to evaluate the association of centromeres in the chromosome spreads rather than conventional indirect fluorescence microscopy. Chromosome spreads from five different isogenic strains were stained with antibodies against Red1, to reveal chromosome axes, and Mtw1-13×MYC, to reveal kinetochores. Spreads with paired/aligned axial elements were scored for whether the Mtw1 foci for axis pairs appeared as a single focus (paired) or as a doublet (unpaired) (examples in Figure 4A). High levels of doublet kinetochore foci could be seen in the zip1Δ strain (Figure 4, A and B) as described previously (Tsubouchi et al. 2008), indicating a loss of centromere pairing. In contrast, ZIP1, zip1-S75E, and zip4Δ mutants were indistinguishable, with high levels of pairing (Figure 4B). Even in zip4Δ zip1-S75E double mutants the kinetochores remain paired, demonstrating that even in the absence of an SC, the Zip1-S75E protein can promote centromere pairing.

Achiasmate centromere pairing in pachytene requires ZIP1 but not ZIP4 or ECM11

To evaluate zip1-S75E phenotypes in a system in which the association of partner centromeres would not be affected by adjacent crossovers, we used circular mini-chromosomes [or centromere (CEN) plasmids] that are small enough that they rarely recombine with one another. These plasmids contain a 5-kb block of chromosome III that contains the centromere (CEN3); selectable yeast genes TRP1 and LEU2 or URA3, so that their segregation could be followed using genetic assays; and lacO and tet O arrays, so that they could be followed by fluorescence microscopy in cells expressing GFP-lacI and tetR-tdTomato fusion proteins, respectively (Straight et al. 1996; Michaelis et al. 1997).

To probe centromere pairing (Figure 5), cells were induced to enter meiosis [at 23° to circumvent the pachytene arrest that occurs when SC proteins are disrupted (Borner et al. 2004)]. Cells were harvested coincident with entry into pachytene, and chromosome spreads were prepared. The purpose of the low sporulation temperature was to allow for these cells to later be assayed for their ability to segregate chromosomes in anaphase I (below). We identified pachytene cells by the condensed ropey appearance of chromosomes after staining with DAPI. Only cells with a single GFP focus and a single tdTomato focus (one copy of each plasmid) were evaluated in this assay. The distance between the two foci was then measured and plotted to show the distribution of these distances (Figure 5A). WT cells showed a median of 0.65 µm between foci. For the CEN plasmids, the separation of dots that did not pair (>0.6 µm) is much larger than was seen with the chromosomal CEN3 and CEN4 dots (compare Figure 5A and Figure 3, A and C). This illustrates how the CEN plasmids, unrestrained by crossovers, can truly disassociate when not paired with one another. It is notable that the chromosomal CEN4 focus-to-focus distances were markedly less than those observed for chromosomal CEN3 (Figure 3C, representative images in Figure 3D). The reason behind this is unclear, but one possible explanation is that chromosome IV, being the larger chromosome, might be more compacted than chromosome III as appears to be the case in mitotic cells (Neurohr et al. 2011).

In the WT control, 47% of cells showed pairing (focus-to-focus distances <0.6 µm; Figure 5, A and B, representative images in Figure 5C). In contrast, only 7 of the 100 assayed zip1Δ spreads showed a focus-to-focus distance of <0.6 µm (Figure 5B). The zip1-S75E mutant exhibited levels of pairing (42%, Figure 5B) that were not significantly different from WT cells.

Previous studies of the role of ZIP4 in mediating centromere associations have yielded different results depending on the assay used. ZIP4 (like ECM11, GMC2, and REC8) is not required for centromere coupling (Figure 1, A and B). When pairing of homologous centromeres was examined using native chromosomes it was found that in the absence of ZIP1, centromeres were often separated, while in zip4 mutants they were paired even though the flanking arm regions were not synapsed (Tsubouchi et al. 2008). However, in zip4 mutants, centromere pairing of nonexchange chromosome partners was significantly diminished (Newnham et al. 2010). We found that in the zip4Δ background, CEN plasmids were unable to pair at WT levels in pachytene but did exhibit a low level of centromere pairing, much as was seen by Newnham et al. (2010). Though this amount of pairing was not significantly more than in zip1Δ mutants, given the numbers of spreads examined, it is striking that the number of zip4Δ cells that exhibited centromere pairing between CEN plasmids was >20% (Figure 5B). One possible explanation for these results is that centromere pairing is possible, but weakened, in zip4 mutants. In this scenario, for chromosomes tacked together along their length by crossovers (as examined by Tsubouchi et al. 2008 and this work, Figure 4), the weakened centromere-pairing mechanism may still be sufficient to hold centromeres together. In contrast, with nonexchange chromosomes or plasmids in which centromere pairing is the only mechanism holding the partners together during the spreading process, the weakened centromere pairing may fail to hold the partners together in every chromosome spread. In both assay systems, elimination of Zip1, which is required for the pairing mechanism, leads to complete loss of pairing. When the zip4Δ zip1-S75E double mutant was assayed, we were surprised to see a rescue phenotype; indeed, the zip4Δ zip1-S75E double mutant cells had no significant decrease in pairing compared to WT cells, but a significant gain of centromere pairing compared to zip4Δ alone (Figure 5B). This indicated to us that the zip1-S75E mutant version of Zip1 promotes more stable centromere associations in late prophase than its WT counterpart—completely contradictory to its role in centromere coupling in early prophase.

A newly described protein of the central element of the SC, Ecm11, has also been discovered to be important for linear loading of Zip1 along the chromosome arms (Zavec et al. 2008; Humphryes et al. 2013). Though found to be dispensable for centromere coupling (Humphryes et al. 2013), it has not been examined closely in its role in centromere pairing or segregation of achiasmate chromosomes. We examined the effects of deletion of ECM11 on CEN plasmid centromere pairing because we were curious whether it was necessary for late centromere pairing. The ecm11Δ strain exhibited no defect in centromere pairing between CEN plasmids (Figure 5B, and representative images in Figure 5C). So despite the importance of ECM11 in stabilizing a continuous SC, it is not necessary at the centromere to mediate coupling or pairing.

From these data, we conclude that some but not all SC proteins play a role in centromere pairing. While Zip1 appears to play one of the most important roles, the importance of other components that affect a mature SC assembly cannot be discounted.

CEN pairing is not sufficient to ensure disjunction at anaphase

Prior work has shown that Zip1-dependent centromere pairing of nonexchange partner chromosomes in prophase is correlated with their proper disjunction in anaphase (Gladstone et al. 2009; Newnham et al. 2010). There are several steps in meiotic progression (Meyer et al. 2013) that separate centromere pairing in pachytene from homolog disjunction in anaphase, and it is not clear how pairing in pachytene translates into better segregation fidelity at anaphase. We asked whether the connections we observed between CEN plasmids in pachytene resulted in proper disjunction of these chromosomes in anaphase I.

We induced meiosis in the cells described in Figure 5, but collected cells at a time when anaphase cells were most prevalent in WT strains. These cells were collected and stained with DAPI and those with two DAPI masses (indicative of the segregated homologs on either side of the cell at anaphase) were scored for either disjunction or nondisjunction of the fluorescently labeled CEN plasmids (Figure 6A, with representative photos in Figure 6B). In the WT control strain, CEN plasmids segregated properly 75% of the time—this is about the segregation fidelity that would be expected if the plasmids that had paired in pachytene (47%, Figure 5) segregated properly, and the remaining 53% of cells segregated randomly—disjoining correctly by chance half of the time. This amount of pairing and disjunction is similar to levels observed previously with achiasmate pairing partners (Guacci and Kaback 1991; Gladstone et al. 2009; Newnham et al. 2010). In a zip1Δ control strain, very few cells completed meiosis I, despite the lower sporulation temperature so these cells were not scored for plasmid segregation. Yet historically, in a different strain background (S288C), nonexchange chromosomes showed elevated levels of nondisjunction when ZIP1 was deleted (Gladstone et al. 2009; Newnham et al. 2010). By comparison, the zip1-S75E mutant exhibited WT levels of segregation; 82% of CEN plasmids segregated properly (Figure 6A).

In contrast, zip4Δ (similar to previous reports, Newnham et al. 2010) and the zip4Δ zip1-S75E double mutant both exhibited random segregation of the CEN plasmids at meiosis I (Figure 6A). The fact that the zip4Δ mutant showed a modest level of pairing and the zip4Δ zip1-S75E double mutant displayed WT levels of pairing during pachytene, yet segregated their plasmids randomly, demonstrates that the pairing that occurs in pachytene may be necessary but not sufficient to ensure disjunction at anaphase I.

Previous experiments have shown that mutants (zip1, zip2, zip3, and zip4) that fail to efficiently assemble the SC are defective in pairing and segregation of nonexchange chromosome partners (Gladstone et al. 2009; Newnham et al. 2010). Here we tested whether a fully WT SC structure is necessary. We found that an ecm11Δ mutant showed proper disjunction near WT levels (67%, Figure 6A). Therefore, not all SC structural-component proteins are required to faithfully segregate the nonexchange CEN plasmids in meiosis.

Discussion

This study has provided evidence that centromere coupling and pairing are controlled by independent mechanisms that are both dependent on ZIP1, and that ZIP4 is critical for proper pairing and disjunction of achiasmate partner chromosomes in meiosis I. The major conclusions from this work are (1) that there is no measureable defect in crossover repression near centromeres in the absence of centromere coupling, (2) that there is a difference between the mechanisms that allow for early centromere coupling and late centromere pairing, and (3) that centromere associations that occur in pachytene do not necessarily lead to correct segregation in anaphase.

zip1-S75E mutants are incapable of coupling but still protect the centromere from crossovers in meiosis

Crossovers that occur close to the centromere are repressed in many organisms including budding yeast, flies, and humans. This is likely due to the fact that these crossovers lead to error-prone disjunction during anaphase I (Sears et al. 1995; Koehler et al. 1996; Lamb et al. 1996; Ross et al. 1996; reviewed in Hassold and Hunt 2001). We had originally hypothesized that centromere coupling might protect homologous centromeres from forming centromere-proximal crossovers (Obeso and Dawson 2010); however, we found no conclusive evidence that such protection is provided to the cells by coupling, as a coupling-deficient zip1-S75E mutant shows WT levels of crossovers both at the centromere and along the chromosome arms. This confirms what Vincenten et al. (2015) have recently published when they examined crossovers in a zip1-S75E mutant in SK1 yeast cells. Their studies confirm that repression of crossing over near centromeres requires ZIP1 (Chen et al. 2008), but that loss of coupling, by using the zip1-S75E allele, yielded no significant change in crossover repression (Vincenten et al. 2015).

zip1-S75E is capable of pairing centromeres in late prophase

The question remained whether early centromere coupling and late centromere pairing could be controlled by similar mechanisms. If coupling and pairing occur by exactly the same mechanism we reasoned that zip1-S75E mutants, defective for centromere coupling, would also struggle to pair centromeres in late prophase, which would hinder proper disjunction of achiasmate chromosomes. To the contrary, we found that the zip1-S75E mutant showed full centromere pairing between CEN plasmids, an otherwise achiasmate chromosome system. This leads us to conclude that centromere coupling and pairing are mediated by two different mechanisms. This conclusion is supported by the observation that ZIP2, ZIP3, and ZIP4 are required for efficient centromere pairing, but it could be argued that the role of these proteins in centromere pairing is indirect—that is, supporting centromere associations by modulating the availability of Zip1 for the process.

ZIP4 is required for disjunction-promoting pairing of CEN plasmids

In zip4 mutants, CEN plasmids exhibit modest levels of pairing at pachytene but segregate randomly. This result is unique since other SC regulatory components examined have either been required for both pairing and disjunction (as is the case for ZIP1, ZIP2, and ZIP3; Gladstone et al. 2009; Newnham et al. 2010) or for neither (ECM11, this article). In budding yeast, Zip4 plays an important role in linear SC assembly and therefore crossover frequency, but how it contributes specifically is not fully understood (Tsubouchi et al. 2006). In atzip4 Arabidopsis mutant lines, there is abrupt separation of homolog pairing partners after diplotene despite normal synapsis (Kuromori et al. 2008), but this is likely due at least in part to the loss of the normal number of crossovers. Similarly, in ZIP4H-deficient mice (also known as TEX11), synapsis levels are normal but crossover number and timing are altered, leading to increased arrest and apoptosis (Adelman and Petrini 2008).

Centromere pairing in zip4 mutant strains is not sufficient to promote subsequent disjunction at anaphase. This suggests that Zip4 might aid in the stability of pairing interactions beyond pachytene, or Zip4 could promote an environment in which a different, more stable, connection can be formed—and it is this connection that could promote proper disjunction to occur. The fact that the majority of Zip1 (and SYCP1 in mouse spermatocytes) has vanished from centromeres before segregation occurs suggests the second model may be correct: pachytene pairing may allow for the formation of another connection that is critical for disjunction. A possible example of this is seen in Drosophila females, where centromeres associate in prophase (Dernburg et al. 1996; Takeo et al. 2011), but later, in metaphase, elastic connections composed of peri-centromeric heterochromatic DNA have been detected between achiasmate partner chromosomes. These connections have been suggested to promote disjunction of the chromosomes (Hughes et al. 2009). Perhaps this form of connection is created in the pachytene environment of centromere pairing, but not in zip4 mutants.

zip1-S75E stabilizes centromere pairing in late prophase

We found that the zip1-S75E allele rescues the defect in pairing seen in zip4Δ mutants during pachytene. How could a version of Zip1 that cannot promote centromere coupling in early prophase provide a stabilizing force in centromere associations late in prophase? The Zip1-S75E protein mimics a version of Zip1 that not only has a phosphorylation at residue 75, but multiple phosphorylated amino acids along the protein (Falk et al. 2010). The initial phosphorylation is completed by Mec1 (ATR), a DSB-activated checkpoint sensor kinase, and serves as a regulatory step to connect meiotic timing with DSB formation (Falk et al. 2010). It is not clear why the Zip1-S75E protein can provide more centromere pairing in the zip4 background than the WT Zip1 protein. Perhaps the Zip1-S75E version of the protein promotes a more stable SC structure than the nonphosphorylated version of Zip1 and it is this sort of structure that promotes centromere pairing. Consistent with this, the Zip1-S75E protein is competent to form an SC that is functional and indistinguishable from a WT SC, where tested. In contrast, centromere coupling relies on a mechanism that is independent of other tested ZMM proteins and is only known, thus far, to require Zip1 and Rec8 at the centromere (Tsubouchi and Roeder 2005; Chuong and Dawson 2010).

Ecm11 is unnecessary for centromere-centromere associations in late prophase

Ecm11, being a newly identified central element protein important for stabilizing Zip1 on the chromosomes (Zavec et al. 2008; Humphryes et al. 2013), was an attractive candidate to test for its effects on centromere pairing. In our hands, however, centromere pairing showed no dependence on ECM11. When anaphase cells were examined, it was also found that ECM11 was dispensable for proper segregation of CEN plasmids; indicating to us that though the Ecm11 protein is critical for full synapsis of natural chromosomes, it is not necessary to the mechanism of pairing and segregation of achiasmate chromosomes.

A model for centromere-centromere interactions in prophase in budding yeast

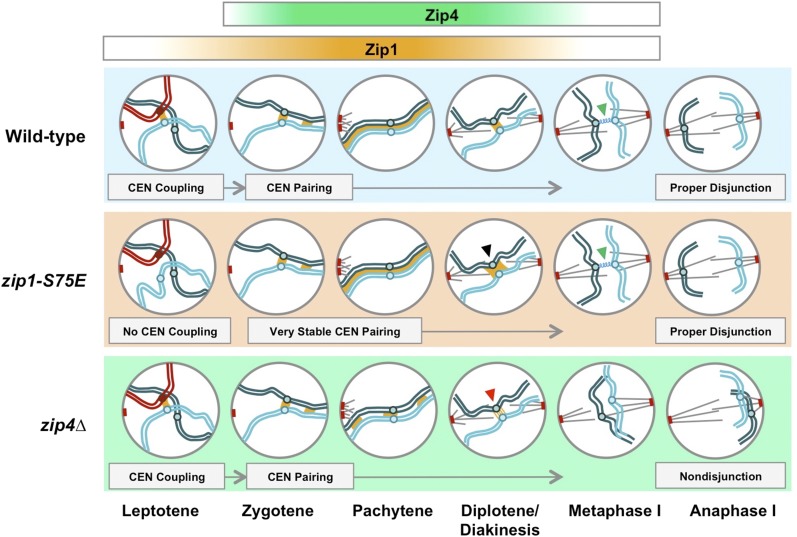

The data presented here provide sufficient evidence to conclude that centromere coupling and centromere pairing operate via separate mechanisms. We propose a model (Figure 7) in which Zip1 and Zip4 play a role in pairing centromeres and segregating achiasmate chromosomes. In this model, centromeres that normally couple in WT and zip4Δ cells are unable to couple in zip1-S75E cells. Once DSBs have been created, Zip4 becomes active in helping Zip1 form linear stretches of SC between homologous partners (Tsubouchi et al. 2006). It is notable here that Zip4 is unable to load onto chromosomes in the absence of DSBs, as seen in a spo11 mutant (Tsubouchi et al. 2006). In the absence of Zip4, Zip1 can still be found in short stretches along the chromosomes and at the centromere, but its ability to form linear stretches along the lengths of chromosomes is impeded (Tsubouchi et al. 2006).

Figure 7.

A model for how Zip1 and Zip4 may contribute to centromere coupling and pairing. A progression of one pair of achiasmate homologous chromosomes proceeding from early prophase through anaphase I. Gradients of Zip1 and Zip4 at the top indicate their contributions to centromere interactions and synaptonemal complex formation during this time. In WT cells, nonhomologous centromere coupling resolves into centromere pairing and SC formation. After SC disassembly, centromere pairing can be seen more clearly until Zip1 unloads and yields a proposed flexible tether that leads to proper disjunction of chromosomes during anaphase I. zip1-S75E cells display defective centromere coupling, but very stable centromere pairing (black arrow) that helps contribute to proper disjunction of achiasmate partners, except in the absence of Zip4. zip4Δ mutants exhibit WT levels of coupling, defective SC formation, and weak centromere pairing during pachytene (red arrow) that leads to a lack of a stable but flexible interaction thereafter (green arrows in metaphase I). This ultimately leads achiasmate chromosomes to behave independently of one another in anaphase I, contributing to random segregation of pairing partners.

How Zip4 helps Zip1 load at a mechanistic level is still not well understood. After pachytene and the disassembly of the majority of the SC, a small stretch of Zip1 stays behind to mediate centromere pairing. Given the ability of Zip4 to promote SC assembly, it may be that there is less Zip1 at the centromeres in zip4 mutants, and this might explain why pairing is somewhat deficient between achiasmate partner chromosomes in the zip4Δ single mutant. It could also be true that the SC that forms in a zip4∆ mutant is less stable and more apt to disassemble prematurely, as supported by observations of premature bivalent separation made in Arabidopsis and mouse spermatocyte ZIP4 mutants (Adelman and Petrini 2008; Kuromori et al. 2008).

The results here could have implications for human health. Intriguingly, mutations in TEX11 in humans, the homolog of ZIP4, lead to infertility and nonobstructive azoospermia (Yang et al. 2015). Though this is likely due to a pachytene arrest from defects in chiasma or SC formation, it remains clear that understanding ZIP4 better might allow us to understand mutations that are relevant to fertility issues in humans. Additionally, measurements of recombination and segregation patterns in humans suggest that the frequency of achiasmate chromosome 21’s is larger than the frequency of conceptuses that are aneuploid for this chromosome. This has led to the suggestion that humans may have mechanisms beyond chiasma formation for ensuring the proper segregation of homologous chromosomes (Oliver et al. 2008; Cheng et al. 2009; Fledel-Alon et al. 2009). Indeed, a recent study has uncovered previously unappreciated segregation mechanisms in human oogenesis that appear to reduce the risks of aneuploidy from achiasmate partners (Ottolini et al. 2015). The centromere-pairing assisted segregation described in this work might provide clues to understanding the fates of achiasmate chromosomes in humans.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental material is available online at www.genetics.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1534/genetics.116.190264/-/DC1.

Acknowledgments

We thank Michael Dresser for plasmid pMDE798; Wolfgang Zachariae for plasmid ptetR-tdTomato-LEU2; and members of the Dawson laboratory, past and present, for contributions of plasmids and yeast strains that were used in these studies. Members of the Program in Cell Cycle and Cancer Biology contributed to the intellectual development of the project. Structure illumination microscopy was performed in the Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation Imaging Core with their expert consultation and technical assistance. The project was supported by National Institutes of Health grant R01 GM-087377 to D.S.D.

Footnotes

Communicating editor: N. Hunter

Literature Cited

- Adelman C. A., Petrini J. H. J., 2008. ZIP4H (TEX11) deficiency in the mouse impairs meiotic double strand break repair and the regulation of crossing over. PLoS Genet. 4: e1000042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal S., Roeder G. S., 2000. Zip3 provides a link between recombination enzymes and synaptonemal complex proteins. Cell 102: 245–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amberg D. C., Burke D. J., Strathem J. N., 2005. Methods in Yeast Genetics: A Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Course Manual. Cold Spring Habor Laboratory Press, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett M., 1979. Centromere arrangements in Triticum aestivum and their relationship to synapsis. Heredity 43: 157. [Google Scholar]

- Bisig C. G., Guiraldelli M. F., Kouznetsova A., Scherthan H., Hoog C., et al. , 2012. Synaptonemal complex components persist at centromeres and are required for homologous centromere pairing in mouse spermatocytes. PLoS Genet. 8: e1002701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boeke J. D., LaCroute F., Fink G. R., 1984. A positive selection for mutants lacking orotidine-5′-phosphate decarboxylase activity in yeast: 5-fluoro-orotic acid resistance. Mol. Gen. Genet. 197: 345–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borner G. V., Kleckner N., Hunter N., 2004. Crossover/noncrossover differentiation, synaptonemal complex formation, and regulatory surveillance at the leptotene/zygotene transition of meiosis. Cell 117: 29–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke D., Dawson D. S., Stearns T., 2000. Methods in Yeast Genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; New York. [Google Scholar]

- Celerin M., Merino S. T., Stone J. E., Menzie A. M., Zolan M. E., 2000. Multiple roles of Spo11 in meiotic chromosome behavior. EMBO J. 19: 2739–2750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S. Y., Tsubouchi T., Rockmill B., Sandler J. S., Richards D. R., et al. , 2008. Global analysis of the meiotic crossover landscape. Dev. Cell 15: 401–415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng E. Y., Hunt P. A., Naluai-Cecchini T. A., Fligner C. L., Fujimoto V. Y., et al. , 2009. Meiotic recombination in human oocytes. PLoS Genet. 5: e1000661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chua P. R., Roeder G. S., 1998. Zip2, a meiosis-specific protein required for the initiation of chromosome synapsis. Cell 93: 349–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuong H., Dawson D. S., 2010. Meiotic cohesin promotes pairing of nonhomologous centromeres in early meiotic prophase. Mol. Biol. Cell 21: 1799–1809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Church K., Moens P. B., 1976. Centromere behavior during interphase and meiotic prophase in Allium fistulosum from 3-D, E.M. reconstruction. Chromosoma 56: 249–263. [Google Scholar]

- Davis L., Smith G. R., 2003. Nonrandom homolog segregation at meiosis I in Schizosaccharomyces pombe mutants lacking recombination. Genetics 163: 857–874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson D. S., Murray A. W., Szostak J. W., 1986. An alternative pathway for meiotic chromosome segregation in yeast. Science 234: 713–717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dernburg A. F., Sedat J. W., Hawley R. S., 1996. Direct evidence of a role for heterochromatin in meiotic chromosome segregation. Cell 86: 135–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding D.-Q., Yamamoto A., Haraguchi T., Hiraoka Y., 2004. Dynamics of homologous chromosome pairing during meiotic prophase in fission yeast. Dev. Cell 6: 329–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dresser M. E., Giroux C. N., 1988. Meiotic chromosome behavior in spread preparations of yeast. J. Cell Biol. 106: 567–573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dresser M. E., Ewing D. J., Harwell S. N., Coody D., Conrad M. N., 1994. Nonhomologous synapsis and reduced crossing over in a heterozygous paracentric inversion in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 138: 633–647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falk J. E., Chan A. C., Hoffmann E., Hochwagen A., 2010. A Mec1- and PP4-dependent checkpoint couples centromere pairing to meiotic recombination. Dev. Cell 19: 599–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fledel-Alon A., Wilson D. J., Broman K., Wen X., Ober C., et al. , 2009. Broad-scale recombination patterns underlying proper disjunction in humans. PLoS Genet. 5: e1000658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fung J. C., Rockmill B., Odell M., Roeder G. S., 2004. Imposition of crossover interference through the nonrandom distribution of synapsis initiation complexes. Cell 116: 795–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gladstone M. N., Obeso D., Chuong H., Dawson D. S., 2009. The synaptonemal complex protein Zip1 promotes bi-orientation of centromeres at meiosis I. PLoS Genet. 5: e1000771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grubb J., Brown M. S., Bishop D. K., 2015. Surface spreading and immunostaining of yeast chromosomes. J. Vis. Exp. e53081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guacci V., Kaback D. B., 1991. Distributive disjunction of authentic chromosomes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 127: 475–488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassold T., Hunt P., 2001. To err (meiotically) is human: the genesis of human aneuploidy. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2: 280–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes S. E., Gilliland W. D., Cotitta J. L., Takeo S., Collins K. A., et al. , 2009. Heterochromatic threads connect oscillating chromosomes during prometaphase I in Drosophila oocytes. PLoS Genet. 5: e1000348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphryes N., Leung W. K., Argunhan B., Terentyev Y., Dvorackova M., et al. , 2013. The Ecm11-Gmc2 complex promotes synaptonemal complex formation through assembly of transverse filaments in budding yeast. PLoS Genet. 9: e1003194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janke C., Magiera M. M., Rathfelder N., Taxis C., Reber S., et al. , 2004. A versatile toolbox for PCR-based tagging of yeast genes: new fluorescent proteins, more markers and promoter substitution cassettes. Yeast 21: 947–962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessop L., Rockmill B., Roeder G. S., Lichten M., 2006. Meiotic chromosome synapsis-promoting proteins antagonize the anti-crossover activity of sgs1. PLoS Genet. 2: e155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keeney S., Giroux C. N., Kleckner N., 1997. Meiosis-specific DNA double-strand breaks are catalyzed by Spo11, a member of a widely conserved protein family. Cell 88: 375–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemp B., Boumil R. M., Stewart M. N., Dawson D. S., 2004. A role for centromere pairing in meiotic chromosome segregation. Genes Dev. 18: 1946–1951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S., Meyer R., Chuong H., Dawson D. S., 2013. Dual mechanisms prevent premature chromosome segregation during meiosis. Genes Dev. 27: 2139–2146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koehler K. E., Boulton C. L., Collins H. E., French R. L., Herman K. C., et al. , 1996. Spontaneous X chromosome MI and MII nondisjunction events in Drosophila melanogaster oocytes have different recombinational histories. Nat. Genet. 14: 406–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurdzo E. L., Dawson D. S., 2015. Centromere pairing–tethering partner chromosomes in meiosis I. FEBS J. 282: 2458–2470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuromori T., Azumi Y., Hayakawa S., Kamiya A., Imura Y., et al. , 2008. Homologous chromosome pairing is completed in crossover defective atzip4 mutant. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 370: 98–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb N. E., Freeman S. B., Savage-Austin A., Pettay D., Taft L., et al. , 1996. Susceptible chiasmate configurations of chromosome 21 predispose to non-disjunction in both maternal meiosis I and meiosis II. Nat. Genet. 14: 400–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb N. E., Feingold E., Savage A., Avramopoulos D., Freeman S., et al. , 1997. Characterization of susceptible chiasma configurations that increase the risk for maternal nondisjunction of chromosome 21. Hum. Mol. Genet. 6: 1391–1399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefrancois P., Rockmill B., Xie P., Roeder G. S., Snyder M., 2016. Multiple pairwise analysis of non-homologous centromere coupling reveals preferential chromosome size-dependent interactions and a role for bouquet formation in establishing the interaction pattern. PLoS Genet. 12: e1006347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longtine M. S., McKenzie A., III, Demarini D. J., Shah N. G., Wach A., et al. , 1998. Additional modules for versatile and economical PCR-based gene deletion and modification in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 14: 953–961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Pérez E., Shaw P., Reader S., Aragón-Alcaide L., Miller T., et al. , 1999. Homologous chromosome pairing in wheat. J. Cell Sci. 112: 1761–1769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer R. E., Kim S., Obeso D., Straight P. D., Winey M., et al. , 2013. Mps1 and Ipl1/Aurora B act sequentially to correctly orient chromosomes on the meiotic spindle of budding yeast. Science 339: 1071–1074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaelis C., Ciosk R., Nasmyth K., 1997. Cohesins: chromosomal proteins that prevent premature separation of sister chromatids. Cell 91: 35–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neurohr G., Naegeli A., Titos I., Theler D., Greber B., et al. , 2011. A midzone-based ruler adjusts chromosome compaction to anaphase spindle length. Science 332: 465–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newnham L., Jordan P., Rockmill B., Roeder G. S., Hoffmann E., 2010. The synaptonemal complex protein, Zip1, promotes the segregation of nonexchange chromosomes at meiosis I. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107: 781–785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novak J. E., Ross-Macdonald P. B., Roeder G. S., 2001. The budding yeast Msh4 protein functions in chromosome synapsis and the regulation of crossover distribution. Genetics 158: 1013–1025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obeso D., Dawson D. S., 2010. Temporal characterization of homology-independent centromere coupling in meiotic prophase. PLoS One 5: e10336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver T. R., Feingold E., Yu K., Cheung V., Tinker S., et al. , 2008. New insights into human nondisjunction of chromosome 21 in oocytes. PLoS Genet. 4: e1000033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ottolini C. S., Newnham L. J., Capalbo A., Natesan S. A., Joshi H. A., et al. , 2015. Genome-wide maps of recombination and chromosome segregation in human oocytes and embryos show selection for maternal recombination rates. Nat. Genet. 47: 727–735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins D. D., 1949. Biochemical mutants in the smut fungus Ustilago maydis. Genetics 34: 607–626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prieto P., Santos A. P., Moore G., Shaw P., 2004. Chromosomes associate premeiotically and in xylem vessel cells via their telomeres and centromeres in diploid rice (Oryza sativa). Chromosoma 112: 300–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiao H., Chen J. K., Reynolds A., Hoog C., Paddy M., et al. , 2012. Interplay between synaptonemal complex, homologous recombination, and centromeres during mammalian meiosis. PLoS Genet. 8: e1002790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rockmill B., Voelkel-Meiman K., Roeder G. S., 2006. Centromere-proximal crossovers are associated with precocious separation of sister chromatids during meiosis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 174: 1745–1754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross L. O., Maxfield R., Dawson D., 1996. Exchanges are not equally able to enhance meiotic chromosome segregation in yeast. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93: 4979–4983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherthan H., Weich S., Schwegler H., Heyting C., Harle M., et al. , 1996. Centromere and telomere movements during early meiotic prophase of mouse and man are associated with the onset of chromosome pairing. J. Cell Biol. 134: 1109–1125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sears D. D., Hegemann J. H., Shero J. H., Hieter P., 1995. Cis-acting determinants affecting centromere function, sister-chromatid cohesion and reciprocal recombination during meiosis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 139: 1159–1173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinohara M., Oh S. D., Hunter N., Shinohara A., 2008. Crossover assurance and crossover interference are distinctly regulated by the ZMM proteins during yeast meiosis. Nat. Genet. 40: 299–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straight A. F., Belmont A. S., Robinett C. C., Murray A. W., 1996. GFP tagging of budding yeast chromosomes reveals that protein-protein interactions can mediate sister chromatid cohesion. Curr. Biol. 6: 1599–1608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sym M., Engebrecht J. A., Roeder G. S., 1993. ZIP1 is a synaptonemal complex protein required for meiotic chromosome synapsis. Cell 72: 365–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeo S., Lake C. M., Morais-de-Sa E., Sunkel C. E., Hawley R. S., 2011. Synaptonemal complex-dependent centromeric clustering and the initiation of synapsis in Drosophila oocytes. Curr. Biol. 21: 1845–1851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takada Y., Naruse C., Costa Y., Shirakawa T., Tachibana M., et al. , 2011. HP1gamma links histone methylation marks to meiotic synapsis in mice. Development 138: 4207–4217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsubouchi T., Roeder G. S., 2005. A synaptonemal complex protein promotes homology-independent centromere coupling. Science 308: 870–873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsubouchi T., Zhao H., Roeder G. S., 2006. The meiosis-specific zip4 protein regulates crossover distribution by promoting synaptonemal complex formation together with zip2. Dev. Cell 10: 809–819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsubouchi T., Macqueen A. J., Roeder G. S., 2008. Initiation of meiotic chromosome synapsis at centromeres in budding yeast. Genes Dev. 22: 3217–3226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincenten N., Kuhl L.-M., Lam I., Oke A., Kerr A. R., et al. , 2015. The kinetochore prevents centromere-proximal crossover recombination during meiosis. eLife 4: e10850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang F., Silber S., Leu N. A., Oates R. D., Marszalek J. D., et al. , 2015. TEX11 is mutated in infertile men with azoospermia and regulates genome-wide recombination rates in mouse. EMBO Mol. Med. 7: 1198–1210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zavec A. B., Comino A., Lenassi M., Komel R., 2008. Ecm11 protein of yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae is regulated by sumoylation during meiosis. FEMS Yeast Res. 8: 64–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J., Pawlowski W. P., Han F., 2013. Centromere pairing in early meiotic prophase requires active centromeres and precedes installation of the synaptonemal complex in maize. Plant Cell 25: 3900–3909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials