Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the results of arthroscopic releases performed in patients with adhesive capsulitis refractory to conservative treatment.

Methods

This was a retrospective study, conducted between 1996 and 2012, which included 56 shoulders (52 patients) that underwent surgery; 38 were female, and 28 had the dominant side affected. The mean age was 51 (29–73) years. The mean follow-up was 65 (12–168) months and the mean preoperative time was 8.9 (2–24) months. According to Zukermann's classification, 23 cases were considered primary and 33 secondary. With the patient in the lateral decubitus position, circumferential release of the joint capsule was performed: joint debridement; rotator interval opening; coracohumeral ligament release; anterior, posterior, inferior, and finally antero-inferior capsulotomy. A subscapularis tenotomy was performed when necessary. All patients underwent intense physical therapy in the immediate postoperative period. In 33 shoulders, an interscalene catheter was implanted for anesthetic infusion. Functional results were evaluated by the UCLA criteria.

Results

Improved range of motion was observed: mean increase of 45° of elevation, 41° of external rotation and eight vertebral levels of medial rotation. According to the UCLA score excellent results were obtained in 25 (45%) patients; good, in 24 (45%); fair, in two (3%); and poor, in two (7%). Patients who had undergone inferior capsulotomy achieved better results. Only 8.8% of patients who used the anesthetic infusion catheter underwent postoperative manipulation. Seven patients had complications.

Conclusion

There was improvement in pain and range of motion. Inferior capsulotomy leads to better results. The use of the interscalene infusion catheter reduces the number of re-approaches.

Keywords: Shoulder pain, Arthroscopy, Bursitis

Resumo

Objetivo

Avaliar os resultados das liberações artroscópicas feitas em pacientes com capsulite adesiva refratária ao tratamento conservador.

Métodos

Trabalho retrospectivo feito entre 1996 e 2012, com 56 ombros (52 pacientes) submetidos a cirurgia; 38 eram do sexo feminino e 28 tinham o lado dominante acometido. A média de idade foi de 51 (29-73) anos. O seguimento médio, de 65 (12-168) meses e o tempo médio de pré-operatório, de 8,9 (2-24) meses. Pela classificação de Zukermann, 23 casos foram considerados primários e 33 secundários. Com o paciente em decúbito lateral, fizemos a liberação circunferencial da cápsula articular: desbridamento articular, abertura do intervalo rotador, liberação do ligamento coracoumeral, capsulotomia anterior, posterior, inferior e finalmente, anteroinferior. A tenotomia do subescapular foi feita quando necessária. Todos foram submetidos a fisioterapia intensa no pós-operatório imediato. Em 33 ombros foi implantado o catéter interescalênico para infusão de anestésico. Os resultados funcionais foram avaliados pelos critérios do escore da University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA).

Resultados

Obtivemos melhoria do arco de movimento: aumento médio de 45° de elevação, 41° de rotação lateral e oito níveis vertebrais de rotação medial. Pelo escore da UCLA, tivemos 25 resultados excelentes (45%), 25 bons (45%), dois razoáveis (3%) e quatro ruins (7%). Os pacientes que fizeram capsulotomia inferior evoluíram melhor do que os que não fizeram. Apenas 8,8% dos pacientes que usaram cateter de infusão anestésico foram submetidos a manipulação no pós-operatório. Sete pacientes apresentaram complicações.

Conclusão

Houve melhoria da dor e do arco de movimento. A capsulotomia inferior leva a melhores resultados. O uso do catéter interescalênico de infusão anestésica diminui o número de reabordagens.

Palavras-chave: Dor de ombro, Artroscopia, Bursite

Introduction

The term “adhesive capsulitis” was first described by Neviaser in 1945, as an inflammatory disease of the shoulder joint capsule that develops with contracture and results in stiffness and pain.1

Treatment aims to control pain and recover range of motion. Initially, treatment is conservative, especially in the acute phase2, 3; there are several therapeutic options, such as physical therapy, corticosteroids and/or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and suprascapular nerve blocks.4, 5, 6, 7 In review articles, Checchia et al.7 and Robinson et al.5 demonstrated good results when treating patients with physical therapy associated with anti-inflammatory drugs (hormonal and non-hormonal) and serial suprascapular nerve blocks.

Invasive treatment is indicated in case of failure of conservative treatment conducted for a minimum period of six months; however, according to the literature reviewed, this interval may range from six weeks to 12 months.8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13 Procedures described as invasive include hydraulic distention of the capsule (the literature differ on its effectiveness due to high recurrence rates), joint manipulation under anesthesia, and capsular release, which can be done through open or arthroscopic surgery.4, 5, 6, 14

Joint manipulation under anesthesia, which was once widely used, is currently being discontinued due to its complications: fractures, glenoid labrum injuries, neurapraxis, rotator cuff tear, and persistent pain.14, 15, 16, 17

One of the first descriptions of the surgical technique for shoulder release through the open access route was made by Ozaki et al.,18 who advocated resection of the coracohumeral ligament and opening of the rotator interval. Literature shows that open surgery presents good results, but adds a greater morbidity than arthroscopy: it is difficult to release the posterior capsule and the intraoperative bleeding is greater, as well as postoperative pain, which extends hospital stay; furthermore, it is necessary to restrict movements until the subscapularis tendon heals.4, 5, 8, 14, 19

Recent studies have shown excellent results, both in terms of pain relief and range of motion gain, with arthroscopic release of adhesive capsulitis. It is currently considered to be a reproducible method, which enables better access to the entire joint capsule of the shoulder with low rates of complications, since the release is done gradually under direct vision through a minimally invasive method, which nonetheless requires proper training.8, 9, 10, 11, 19, 20, 21 Literature mentions as complications of this procedure the risk of iatrogenic injury to the axillary nerve,22 chondral lesion due to the insertion of the instruments in a joint with reduced space,9 and chondrolysis due to thermal injury caused by the use of intra-articular radiofrequency.23

This study aimed to evaluate the results of arthroscopic releases performed in this department in patients with adhesive capsulitis refractory to conservative treatment.

Material and methods

This study retrospectively analyzed 56 shoulders of 52 patients who underwent arthroscopic release due to adhesive capsulitis refractory to conservative treatment. Surgeries were performed between February 1996 and May 2012 by the Shoulder and Elbow Group of the Santa Casa de São Paulo School of Medical Sciences – Fernandinho Simonsen Pavilion.

Patients with adhesive capsulitis refractory to conservative treatment, with a minimum follow-up period of one year, with no other abnormalities that could justify the loss of range of motion (osteoarthritis, malunion, and necrosis, among others) were included. The clinical and epidemiological data are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient clinical data.

| Sex | Age | Dominant side | Comorbidities | Associated lesions | Symptoms | Pre-op treatment | Range of motion |

Post-op UCLA |

Follow-up | Complications | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ΔT/years | ΔT/months | ΔT/months | Pre-op. |

Post-op. |

Score | Result | ΔT/months | ||||||||||

| Elev. | LR | MR | Elev. | LR | MR | ||||||||||||

| 1 | F | 56 | − | DM II, SAH | – | 36 | 11 | 90° | 35° | L5 | 140° | 45° | T6 | 31 | Good | 23 | Radial neurap. |

| 2 | F | 43 | + | SAH, DM II | – | 36 | 18 | 95° | 10° | L4 | 130° | 40° | T10 | 27 | Fair | 50 | – |

| 3 | F | 55 | + | DM I | – | 26 | 11 | 90° | 20° | Glut | 150° | 60° | T11 | 33 | Good | 26 | – |

| 4 | F | 44 | + | – | – | 7 | 5 | 70° | 20° | Glut | 150° | 60° | T8 | 33 | Good | 14 | – |

| 5 | F | 56 | − | SAH | – | 17 | 11 | 90° | 0° | L5 | 125° | 30° | T8 | 30 | Good | 36 | – |

| 6 | F | 61 | − | SAH, DM II | – | 12 | 10 | 100° | 15° | L3 | 150° | 45° | T7 | 31 | Good | 72 | – |

| 7 | F | 47 | + | Epilep. | – | 24 | 18 | 70° | 30° | S1 | 120° | 40° | T12 | 15 | Bad | 128 | Pre-op + RCI |

| 8 | F | 45 | + | – | – | 22 | 13 | 90° | 0° | S1 | 130° | 50° | S1 | 25 | Fair | 138 | RSD |

| − | – | – | 15 | 15 | 100° | 10° | T12 | 150° | 60° | T10 | 31 | Good | 72 | – | |||

| 9 | F | 45 | − | SAH, DM II | – | 18 | 15 | 90° | 0° | Glut | 150° | 60° | T7 | 35 | Excellent | 124 | – |

| + | – | – | 13 | 11 | 90° | 10° | Glut | 150° | 60° | L5 | 31 | Good | 124 | Pain AC | |||

| 10 | F | 47 | + | Asthma | – | 18 | 14 | 30° | −10° | GT | 90° | 20° | GT | 15 | Bad | 51 | Pre-op + RSD |

| 11 | M | 64 | − | DMII, SAH | – | 22 | 14 | 70° | 25° | GT | 130° | 40° | L1 | 30 | Good | 76 | – |

| 12 | F | 49 | + | DMI | – | 42 | 7 | 90° | 0° | Glut | 120° | 30° | T10 | 30 | Good | 75 | – |

| 13 | F | 52 | + | – | Post-op RCI | 13 | 13 | 100° | 30° | L2 | 140° | 60° | T9 | 32 | Good | 64 | – |

| 14 | M | 36 | + | Tab. | Post-op ft GT + glenoid | 34 | 23 | 125° | 0° | L4 | 140° | 40° | T10 | 28 | Good | 67 | – |

| 15 | F | 42 | + | SAH, Tab. | Ft. humeral neck surg. cons. treat. | 49 | 10 | 90° | 40° | Glut | 120° | 60° | L3 | 30 | Good | 42 | – |

| 16 | F | 56 | + | – | – | 24 | 22 | 90° | 20° | S1 | 100° | 20° | L3 | 18 | Bad | 16 | – |

| 17 | F | 55 | + | DM II, SAH, breast CA | – | 24 | 24 | 80° | 45° | Glut | 130° | 45° | Glut | 15 | Bad | 27 | – |

| 18 | M | 55 | − | – | Post-op cal. tend. | 60 | 9 | 85° | 10° | L5 | 130° | 70° | T12 | 30 | Good | 22 | – |

| 19 | F | 67 | + | – | – | 8 | 8 | 70° | 0° | GT | 150° | 45° | T10 | 34 | Good | 115 | – |

| 20 | F | 60 | + | Hypot. | – | 2.5 | 2.5 | 110° | 60° | L5 | 140° | 60° | T8 | 32 | Good | 84 | – |

| 21 | M | 60 | + | SAH, Dep. | – | 3.5 | 3 | 60° | −10° | S1 | 150° | 60° | L4 | 35 | Excellent | 84 | – |

| 22 | F | 55 | + | – | – | 5 | 5 | 110° | 10° | L4 | 160° | 60° | T2 | 35 | Excellent | 39 | – |

| 23 | F | 57 | + | DM, Coron. | – | 24 | 8 | 80° | 10° | S1 | 140° | 60° | L5 | 35 | Excellent | 79 | – |

| 24 | F | 57 | − | SAH | – | 13 | 6 | 90° | 20° | L4 | 150° | 80° | T5 | 35 | Excellent | 27 | – |

| 25 | M | 57 | − | DM II | – | 3 | 3 | 90° | 10° | S1 | 150° | 80° | T6 | 35 | Excellent | 70 | – |

| 26 | F | 53 | − | – | – | 9.5 | 7 | 80° | 0° | L5 | 150° | 60° | T7 | 35 | Excellent | 83 | – |

| 27 | M | 51 | + | DM I | Tend. calc. | 36 | 12 | 100° | 0° | L5 | 150° | 60° | T10 | 35 | Excellent | 69 | – |

| 28 | F | 45 | + | – | – | 12 | 8 | 80° | 10° | L3 | 150° | 60° | T7 | 30 | Good | 74 | – |

| 29 | M | 50 | − | – | – | 10 | 10 | 90° | 0° | L5 | 140° | 60° | T10 | 34 | Excellent | 92 | – |

| 30 | F | 49 | + | – | – | 24 | 24 | 100° | 20° | L5 | 140° | 60° | T8 | 35 | Excellent | 118 | – |

| 31 | F | 44 | − | – | – | 6 | 6 | 100° | 20° | L5 | 160° | 70° | T5 | 35 | Excellent | 86 | – |

| 32 | M | 43 | + | – | Sd. impact | 16 | 4 | 130° | 45° | L1 | 140° | 60° | L1 | 35 | Excellent | 122 | – |

| 33 | M | 43 | + | DM I | – | 13 | 5 | 120° | 0° | L3 | 150° | 60° | T10 | 35 | Excellent | 128 | – |

| 34 | M | 42 | − | DM I | – | 11 | 8 | 130° | 20° | L3 | 150° | 60° | T8 | 35 | Excellent | 95 | – |

| 35 | F | 42 | − | – | – | 30 | 6 | 140° | 45° | T10 | 150° | 60° | T6 | 35 | Excellent | 70 | – |

| 36 | M | 29 | − | Tab. | Ft. GT (cons. treat.) | 3 | 3 | 100° | 10° | L2 | 140° | 30° | T12 | 28 | Good | 168 | – |

| 37 | F | 35 | − | Hypot. | – | 5 | 3 | 80° | 0° | S1 | 160° | 45° | T5 | 35 | Excellent | 16 | – |

| 38 | F | 73 | − | SAH, DM II | Osteoarthritis AC | 4 | 3 | 130° | 60° | S1 | 140° | 60° | L4 | 34 | Excellent | 12 | – |

| 39 | F | 65 | − | – | – | 3 | 3 | 70° | 0° | S1 | 150° | 70° | T7 | 34 | Excellent | 25 | Axillary neurap. |

| 40 | M | 58 | + | – | – | 5 | 5 | 120° | 30° | L4 | 140° | 30° | L1 | 32 | Good | 69 | – |

| 41 | F | 52 | − | Dep. | – | 4 | 4 | 40° | −20° | Glut | 160° | 80° | T5 | 34 | Excellent | 107 | Radial neurap. |

| 42 | F | 55 | − | Hypot. | – | 8 | 6 | 100° | −10° | L4 | 150° | 60° | T6 | 33 | Good | 44 | – |

| 43 | F | 57 | − | DLP | Tend. calc. | 12 | 6 | 120° | 45° | L5 | 150° | 70° | T7 | 33 | Good | 14 | – |

| 44 | F | 56 | + | DLP | – | 12 | 8 | 120° | 60° | T12 | 160° | 80° | T3 | 35 | Excellent | 19 | – |

| 45 | M | 52 | + | SAH, Hypot. | – | 7 | 2 | 100° | 20° | L4 | 150° | 80° | T7 | 34 | Excellent | 85 | – |

| M | − | SAH, Hypot. | – | 3 | 3 | 120° | 30° | L5 | 150° | 80° | T6 | 35 | Excellent | 54 | – | ||

| 46 | F | 51 | − | – | Wrist ft. + imob. | 8 | 6 | 90° | 10° | L2 | 150° | 70° | T5 | 35 | Excellent | 96 | – |

| F | + | – | – | 6 | 2 | 130° | 45° | L3 | 140° | 70° | T6 | 34 | Excellent | 49 | – | ||

| 47 | F | 49 | + | – | Sd. impact | 6 | 2 | 150° | 20° | L4 | 140° | 70° | T5 | 32 | Good | 52 | – |

| 48 | F | 53 | + | Sd. Panic | Cal. tend. of the sub. | 5 | 2 | 100° | 10° | L4 | 150° | 70° | T5 | 33 | Good | 72 | – |

| 49 | F | 48 | − | Tob. | – | 5 | 7 | 90° | 0° | L3 | 130° | 70° | T5 | 28 | Good | 14 | – |

| 50 | M | 46 | + | – | Post-op SLAP | 8 | 12 | 140° | 45° | T8 | 145° | 70° | T5 | 35 | Excellent | 19 | – |

| 51 | F | 51 | + | Breast CA | Post-op epiphyseal ft | 12 | 12 | 90° | −10° | Glut | 130° | 30° | T9 | 29 | Good | 21 | – |

| 52 | F | 50 | + | DM I | – | 6 | 8 | 80° | 0° | Glut | 110° | 60° | T10 | 30 | Good | 13 | – |

| Means | 51.2 | 15.3 | 8.9 | 96° | 16° | L5 | 141° | 57° | T9 | 31.4 | 64.8 | ||||||

Source: Santa Casa de São Paulo Archives.

AC, acromioclavicular joint; CA, cancer; dep., depression; RSD, reflex sympathetic dystrophy; DLP, dyslipidemia; DM, diabetes mellitus; elev., elevation; epilep., epilepsy; F, female; ft., fracture; glut, gluteus; GT, greater trochanter of the femur; SAH, systemic hypertension; hypot., hypothyroidism; imob., immobilization; RCI, rotator cuff injury; neurap., neurapraxia; post-op., post-operative period; pre-op., pre-operative period; LR, lateral rotation; MR, medial rotation; sd, syndrome; sub, subscapularis tendon; tob, tobacco smoker; cal. tend., calcareous tendinitis.; GT, greater tuberosity; cons. treat., conservative treatment prior to the fracture; M, male.

Patients underwent conservative treatment for a mean period of 8.9 months (2–24). Most of them (66%) were treated with serial suprascapular nerve blocks associated with physiotherapy, with a mean of 12.2 blocks.2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23 Surgery was indicated when there was no response to conservative treatment, i.e., there was improvement in pain but patient remained with limited joint mobility, which hindered their day-to-day activities or even work activities. It was also indicated when patient could not attend the office with the regularity needed for undergoing blocks, that is, every 15 days until complete improvement of the condition, which takes seven months, on average.7

Mean postoperative follow-up was 65 months (12–168) and patients’ age ranged from 29 to 73 years (mean 51.2); 38 patients were female (73%) and 14 male (27%). In 28 (54%) patients, the dominant limb underwent arthroscopic release; in four patients (three female and one male), involvement was bilateral and both shoulders were subjected to this procedure (8%).

Regarding the etiology, 23 shoulders were classified according to Zuckerman and Rokito24 as primary capsulitis (41%) and 33 as secondary (59%), 20 of systemic origin. Of these, 15 patients were diabetic (29% of total), 12 had intrinsic causes (92.3%), and one had extrinsic causes (3.7%).

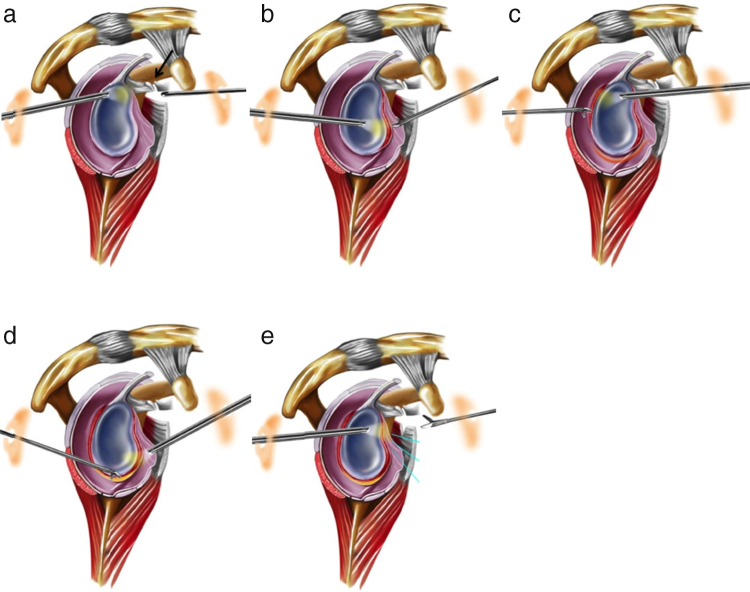

Patients underwent several arthroscopic procedures, which varied according to the need and improvement of the surgical technique, as shown in Table 2. With the patient positioned in lateral decubitus, the following steps were taken: through the anterior portal, joint debridement was made, the rotator interval was opened, the coracohumeral ligament was released, and an interior capsulotomy was performed. Then, portal was changed. Through the posterior portal, posterior and inferior capsulotomies were made. Finally, again through the anterior portal, an anteroinferior capsulotomy was made with the aid of a basket-type forceps to avoid axillary nerve injury. At the end of these procedures, circumferential release of the joint capsule was achieved. Lateral rotation was clinically assessed; if the gain was considered to be insufficient, a partial tenotomy of the subscapularis was made (Fig. 1).

Table 2.

Procedures performed during arthroscopy.

| Procedures | Number of shoulders | % |

|---|---|---|

| Opening of the rotator interval | 56 | 100 |

| Coracohumeral ligament release | 55 | 98 |

| Anterior capsulotomy | 52 | 93 |

| Posterior capsulotomy | 44 | 78 |

| Inferior capsulotomy | 20 | 36 |

| Subscapularis tenotomy | 14 | 25 |

| Acromioplasty | 24 | 43 |

| Mumford | 11 | 19 |

| Calcareous tendinitis drainage | 2 | 3.5 |

Source: Santa Casa de São Paulo Archives.

Fig. 1.

Surgical steps of the arthroscopic release for treating adhesive capsulitis. Sagittal section of the left shoulder showing (a) release of coracohumeral ligament (arrow), (b) anterior capsulotomy performed through the anterior portal, (c) posterosuperior capsulotomy, and (d) anteroinferior capsulotomy, along the axillary nerve, with both capsulotomies performed using the posterior portal, and (e) tenotomy of the superior quarter of the subscapularis muscle tendon, again through the anterior portal.

From the first day post-operative onwards, patients were subjected to an intensive physical therapy work with potent analgesia. An interscalene catheter was used in 33 shoulders (59%) for anesthesia infusion (bupivacaine). At discharge, the catheter was removed and patient was referred for outpatient physiotherapy sessions and received guidelines for performing capsular stretching exercises at home. Patients were hospitalized an average of four days. In the first weeks, patients were instructed to attend 4–5 therapy sessions per week; this schedule was modified according to patient's improvement. On average, patients attended 53.4 sessions (12–139).

The shoulder functional analysis criteria by the University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA)25 was used to assess the present results; shoulder range of motion was measured according to the criteria set forth by the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons.26

For the statistical analysis, the following programs were used: SPSS (Statistical Package for Social Sciences) version 17, Minitab 16, and Excel Office 2010, and the following tests were applied: ANOVA, Student's t-test for paired samples, equality of two proportions, and Pearson's correlation. To obtain the results, the 95% confidence interval was considered statistically significant (p < 0.05).

This study was approved by the hospital's ethics committee under CAAE No. 14412713.2.0000.5479.

Results

Patients presented an improved range of motion. Mean pre-operative range of motion was 96° of elevation, 16° of lateral rotation, and L5 medial rotation; after arthroscopic release, means became 141° of elevation, 57° of lateral rotation, and T9 medial rotation (p < 0.001).

When postoperative results were compared with the contralateral limb, excluding patients who underwent bilateral arthroscopic release, a mean deficit of 3° of elevation was observed (p = 0.03).

Regarding the procedures, patients undergoing inferior capsulotomy had a mean of 8° of elevation (p = 0.057, close to significance margin), 13° of lateral rotation (p = 0.003), four vertebral levels (p = 0.002), and 3.2 points in the UCLA score (p = 0.021) more than those patients who did not undergo inferior capsulotomy.

Patients undergoing partial tenotomy of the subscapularis (25%) had lower preoperative lateral rotation (p = 0.010) and elevation (p = 0.062). The mean elevation for this group was 86°, and mean lateral rotation was 5°, which was lower than the 99° of elevation and 20° of lateral rotation observed in patients who did not undergo this procedure.

Regarding postoperative analgesia, only 8.8% of patients in whom the anesthetic infusion catheter was used underwent manipulation during the postoperative follow-up, in contrast with the 31.8% of patients in whom said catheter was not used, which proves its effectiveness in preventing a new procedure (p = 0.028).

No statistical significance was observed in relationship to the results and variables age, sex, and comorbidities among the diabetic and non-diabetic populations and between primary and secondary capsulitis.

Based on the results of the UCLA criteria,25 25 shoulders were classified as excellent (45%), 25 as good (45%), two as fair (3%), and four as poor (7%). Seven patients had complications (12.5%), including two with radial neurapraxia, one with axillary neurapraxia, two reoperations, two cases of reflex sympathetic dystrophy, one rotator cuff injury, and one case of acromioclavicular pain.

Discussion

The primary goal of treatment of adhesive capsulitis is pain relief and restoration of range of motion in the shortest time possible.

Initial treatment should be conservative, because the literature shows that physical therapy associated with adjuvant methods yields good results. The minimum duration recommended by most authors is six months, but it can vary from six weeks to 12 months.5, 8, 9, 12, 13, 27 In the present study, the mean time of evolution to surgical indication was 8.9 (2–24) months. In this service, cases of adhesive capsulitis are treated with physical therapy associated with serial suprascapular nerve blocks, and a rate of 84% good results was observed in a study by the present authors published in 20067; 37 (66%) patients in the current study underwent this treatment with a mean of 12 (range: 2–23) nerve blocks until surgical indication. It is noteworthy that the nerve block is done on an outpatient basis, in a minimally invasive manner; however, it must be done regularly every 15 days and its initial analgesic effect, on average, starts after the fourth block.7 For these reasons, many patients refused to follow the treatment and chose surgery, despite the initial guidance for conservative treatment.

Regarding invasive procedures, the authors prefer arthroscopic release rather than other techniques, due to the lower rates of complications and excellent results.

Gerber et al.19 reported a gain of 38° of elevation and 18° of lateral rotation; Warner et al.,9 an increase of 49° of flexion, 42° of lateral rotation, and eight levels of spinal processes in medial rotation; Cohen et al.,21 an increase of 64° of flexion, 43.5° of lateral rotation, and eight levels in spinal medial rotation; other authors have also reported good results.8, 12, 13, 20 The present results showed an improvement in the elevation of 45°, 38° of lateral rotation, and eight levels in the spinal medial rotation, with a final mean range of motion of 141° of elevation, 57° of medial rotation, and 9T medial rotation, results that are in agreement with the literature.

Mean elevation and lateral and medial rotation of the contralateral limb of these patients, excluding those who underwent bilateral release, were 143°, 56°, and T9, respectively. Comparing mean postoperative elevation, excluding patients who had bilateral release, a deficit of only 3° was observed (p = 0.030). This demonstrates that, albeit with a small deficit of elevation, generally it is possible to restore range of motion in these patients.

Regarding the procedures performed during arthroscopic release, initial cases were limited to opening of the rotator interval, resection of the coracohumeral ligament, anterior and posterior capsular releases, and a final joint manipulation for rupture of the inferior capsule. In their study, Pollock et al.20 performed arthroscopy immediately after manipulation of the shoulder joint and found a rate of 30% of inferior capsule rupture failure with this procedure. Studies of the arthroscopic anatomy of the axillary nerve10, 28, 29 provided a better understanding, allowing the development of safe techniques for inferior capsular release; therefore, circumferential releases have become standard in the service. The 20 (36%) patients who underwent inferior capsulotomy had better results compared with other patients in the final mean elevation (146° vs. 138°, p = 0.057), mean lateral rotation (65° vs. 52°, p = 0.003), mean medial rotation (T7 vs. T11, p = 0.002), and mean postoperative UCLA score25 (33.4 vs. 30.2, p = 0.021). The authors believe that circumferential capsulotomy reduces the risks of complications associated with joint manipulation, as well as the recurrence rate, restoring more functional range of motion in a shorter time. As for the tenotomy of the subscapularis, the procedure was performed in the intra-articular portion of the tendon that is visualized during arthroscopy; it was indicated during surgery, after complete capsular release, when it was not possible to achieve the same lateral rotation (in degrees) as the contralateral side.

Pollock et al.20 and Cinar et al.30 observed worse outcomes in diabetic patients when compared with non-diabetic patients after arthroscopic release. In the present study, results of arthroscopic treatment were similar in these two populations, with no statistical significance, both in relationship to the range of motion and final UCLA,2 which was in agreement with results observed with conservative treatment.7 Regarding final mean range of motion, diabetics showed a slight limitation in relation to non-diabetic patients, with mean post-operative elevation (p = 0.551), lateral rotation (p = 0.357), and medial rotation (p = 0.154) of 140°, 54°, and T11. In turn, these results in non-diabetics were 142°, 58°, and T9, respectively. Regarding the mean UCLA,25 it was 31.4 for both groups (p = 0.995), although none of these data were statistically significant.

Another very important point in the surgical treatment of adhesive capsulitis is postoperative rehabilitation. Physical therapy protocol should be initiated on the first postoperative day, in an intensive regimen associated with potent analgesia, in order to maintain movement gain achieved intraoperatively. The use of interscalene catheter for anesthetic infusion in the early postoperative period is recommended by some authors.2, 9, 13 Mariano et al.31 concluded that continuous interscalene block is superior to the single application block, providing greater pain relief, minimizing the use of additional opioids, improving sleep quality, and increasing patient satisfaction after shoulder surgery. This analgesia facilitates the physical therapy rehabilitation work, thus leading to a better result. In the present study, of the 33 shoulders (59%) in which this catheter was used, only 8.8% patients required joint manipulation during the postoperative follow-up period: in one patient, the catheter moved out of the interscalene space and lost its analgesic effect on the second postoperative day. Conversely, 31.8% of those in whom this catheter was not used required joint manipulation due to loss of motion in the postoperative follow-up, which proves the effectiveness of this analgesia in preventing relapse (p = 0.028). This manipulation is performed within a maximum of 30 days postoperatively.

Complications were observed in seven patients: two patients developed radial neurapraxia, with reversal of symptoms after 2–3 months. This complication probably originated during the interscalene anesthetic block. This patient did not use interscalene catheter for anesthetic infusion. One patient developed axillary neurapraxia postoperatively. He presented a complete recovery of function in four months. This patient did not undergo inferior capsulotomy, but rather the manipulation for inferior capsule rupture. The authors believe that there was a probable traction of the axillary nerve during manipulation, causing symptoms. Although mentioned as a possible complication of inferior capsulotomy,1 no cases of injury or neurapraxia of this nerve were observed in patients who underwent this procedure. Therefore, we can conclude that inferior capsulotomy is a safe procedure, as long as the correct surgical technique is performed.

Regarding the other complications, one patient had residual pain in the acromioclavicular joint (case 9), two (cases 8 and 10) developed reflex sympathetic dystrophy in the operated limb, and one had a rotator cuff injury. This patient (case 7) underwent two arthroscopic procedures for treatment of adhesive capsulitis with joint release; during follow-up after second surgery, as the patient still presented range of motion limitation and pain, a magnetic resonance imaging exam was performed, which disclosed rotator cuff injury. In the two previous surgical procedures, patient had undergone joint manipulation to complement capsular release, which may have contributed to the cause of injury.

Another patient (case 10) required reoperation, and a wider capsular release was performed; nonetheless, patient still presented range of motion limitation and pain. In the initial surgery, joint access was difficult due to the small articular space, which eventually compromised the procedure: the release of the joint capsule was incomplete. Another patient (case 16) had poor UCLA score25 results; an osteochondral lesion of the humeral head, observed during arthroscopic inspection, may have negatively influenced rehabilitation. One patient (case 17), although the range of motion was satisfactorily restored, persisted in pain and was dissatisfied with the results. The two patients (cases 2 and 8) with regular results obtained range of motion improvement; however, they still had restrictions and pain during daily activities, and one of them presented reflex sympathetic dystrophy (case 8).

Conclusion

Arthroscopic release of patients with adhesive capsulitis refractory to conservative treatment is effective for improving pain and range of motion.

The best results were obtained in patients who underwent inferior capsulotomy.

Lower reoperation rates were observed in patients in whom the interscalene catheter for anesthetic infusion was used, demonstrating its importance in postoperative rehabilitation.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Study conducted at the Faculdade de Ciências Médicas da Santa Casa de São Paulo (FCMSCSP), Departamento de Ortopedia e Traumatologia, Grupo de Cirurgia do Ombro e Cotovelo, São Paulo, SP, Brazil.

References

- 1.Neviaser J.S. Adhesive capsulitis of the shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1945;27:211–222. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reeves B. The natural history of the frozen shoulder syndrome. Scand J Rheumatol. 1975;4(4):193–196. doi: 10.3109/03009747509165255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grey R.G. The natural history of idiopathic frozen shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1978;60(4):564. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Endres N.K., ElHassan B., Higgins L.D., Warner J.P. The stiff shoulder. In: Rockwood C.A. Jr., Matsen F.A. 3rd, Wirth M.A., Lippitt S.B., editors. The shoulder. 4th ed. Saunders; Philadelphia: 2009. pp. 1405–1428. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Robinson C.M., Seah K.T., Chee Y.H., Hindle P., Murray I.R. Frozen shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2012;94(1):1–9. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.94B1.27093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ferreira Filho A.A. Capsulite adesiva. Rev Bras Ortop. 2005;40(10):565–574. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Checchia S.L., Fregoneze M., Miyazaki A.N., Santos P.D., Silva L., Ossada A. Tratamento da capsulite adesiva com bloqueios seriados do nervo supraescapular. Rev Bras de Ortop. 2006;41(7):245–252. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lafosse L., Boyle S., Kordasiewicz B., Aranberri-Gutiérrez M., Fritsch B., Meller R. Arthroscopic arthrolysis for recalcitrant frozen shoulder: a lateral approach. Arthroscopy. 2012;28(7):916–923. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2011.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Warner J.J., Allen A., Marks P.H., Wong P. Arthroscopic release for chronic, refractory adhesive capsulitis of the shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1996;78(12):1808–1816. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199612000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jerosch J. 360 degrees arthroscopic capsular release in patients with adhesive capsulitis of the glenohumeral joint-indication, surgical technique, results. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2001;9(3):178–186. doi: 10.1007/s001670100194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harryman D.T., 2nd, Matsen F.A., 3rd, Sidles J.A. Arthroscopic management of refractory shoulder stiffness. Arthroscopy. 1997;13(2):133–147. doi: 10.1016/s0749-8063(97)90146-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Segmüller H.E., Taylor D.E., Hogan C.S., Saies A.D., Hayes M.G. Arthroscopic treatment of adhesive capsulitis. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1995;4(6):403–408. doi: 10.1016/s1058-2746(05)80030-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baums M.H., Spahn G., Nozaki M., Steckel H., Schultz W., Klinger H.M. Functional outcome and general health status in patients after arthroscopic release in adhesive capsulitis. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2007;15(5):638–644. doi: 10.1007/s00167-006-0203-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tasto J.P., Elias D.W. Adhesive capsulitis. Sports Med Arthrosc. 2007;15(4):216–221. doi: 10.1097/JSA.0b013e3181595c22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Loew M., Heichel T.O., Lehner B. Intraarticular lesions in primary frozen shoulder after manipulation under general anesthesia. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2005;14(1):16–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2004.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koh K.H., Kim J.H., Yoo J.C. Iatrogenic glenoid fracture after brisement manipulation for the stiffness of shoulder in patients with rotator cuff tear. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2013;23(Suppl. 2):S175–S178. doi: 10.1007/s00590-012-1090-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Magnussen R.A., Taylor D.C. Glenoid fracture during manipulation under anesthesia for adhesive capsulitis: a case report. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20(3):e23–e26. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2010.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ozaki J., Nakagawa Y., Sakurai G., Tamai S. Recalcitrant chronic adhesive capsulitis of the shoulder. Role of contracture of the coracohumeral ligament and rotator interval in pathogenesis and treatment. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1989;71(10):1511–1515. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gerber C., Espinosa N., Perren T.G. Arthroscopic treatment of shoulder stiffness. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001;(390):119–128. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200109000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pollock R.G., Duralde X.A., Flatow E.L., Bigliani L.U. The use of arthroscopy in the treatment of resistant frozen shoulder. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1994;(304):30–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cohen M., Amaral M.V., Brandão B.L., Pereira M.R., Monteiro M., Motta Filho G.R. Avaliação dos rersultados do tratamento artroscópico da capsulite adesiva. Rev Bras Ortop. 2013;48(3):272–277. doi: 10.1016/j.rboe.2012.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jerosch J., Filler T.J., Peuker E.T. Which joint position puts the axillary nerve at lowest risk when performing arthroscopic capsular release in patients with adhesive capsulitis of the shoulder? Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2002;10(2):126–129. doi: 10.1007/s00167-001-0270-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jerosch J., Aldawoudy A.M. Chondrolysis of the glenohumeral joint following arthroscopic capsular release for adhesive capsulitis: a case report. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2007;15(3):292–294. doi: 10.1007/s00167-006-0112-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zuckerman J.D., Rokito A. Frozen shoulder: a consensus definition. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20(2):322–325. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2010.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ellman H., Hanker G., Bayer M. Repair of the rotator cuff. End-result study of factors influencing reconstruction. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1986;68(8):1136–1144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hawkins R.J., Bokos D.J. Clinical evaluation of shoulder problems. In: Rockwood C.A. Jr., Matsen F.A. 3rd, editors. The shoulder. 2nd ed. Saunders; Philadelphia: 1998. pp. 175–180. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Green S., Buchbinder R., Hetrick S. Physiotherapy interventions for shoulder pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;(2):CD004258. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Price M.R., Tillett E.D., Acland R.D., Nettleton G.S. Determining the relationship of the axillary nerve to the shoulder joint capsule from an arthroscopic perspective. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86(10):2135–2142. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200410000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yoo J.C., Kim J.H., Ahn J.H., Lee S.H. Arthroscopic perspective of the axillary nerve in relation to the glenoid and arm position: a cadaveric study. Arthroscopy. 2007;23(12):1271–1277. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2007.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cinar M., Akpinar S., Derincek A., Circi E., Uysal M. Comparison of arthroscopic capsular release in diabetic and idiopathic frozen shoulder patients. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2010;130(3):401–406. doi: 10.1007/s00402-009-0900-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mariano E.R., Afra R., Loland V.J., Sandhu N.S., Bellars R.H., Bishop M.L. Continuous interscalene brachial plexus block via an ultrasound-guided posterior approach: a randomized, triple-masked, placebo-controlled study. Anesth Analg. 2009;108(5):1688–1694. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e318199dc86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]