Abstract

The family of Eph receptor tyrosine kinases and their ephrin ligands regulate a diverse array of physiological processes, such as axonal guidance, bone remodeling, and immune cell development and trafficking. Eph/ephrin interactions have also been implicated in various pathological processes, including inflammation, cancer, and tumor angiogenesis. Because Eph receptors play prominent roles in both the immune system and cancer, they likely impact the tumor immune microenvironment, an area in which Eph receptors remain understudied. Here, we provide the first comprehensive review of Eph receptors in the context of tumor immunity. With the recent rise of cancer immunotherapies as promising therapeutic interventions, further elucidation of the roles of Eph receptors in the tumor immune microenvironment will be critical for understanding and developing novel targets against tumor immune evasion.

Keywords: Eph receptors, receptor tyrosine kinases, tumor immunity, cancer-immunity cycle

Introduction

Over the past several decades, the paradigm of cancer research and anticancer therapy has shifted from a focus on solely targeting tumor cells to a broader approach of understanding and remodeling the tumor microenvironment. The tumor microenvironment contains a diverse population of host cells, among which include immune cells that are often hijacked by cancer cells to fulfill the tumor’s agenda for growth and metastasis. Recently, increasing attention has been directed towards investigating cancer cell evasion of immune destruction, and breakthroughs in this field have led to novel strategies for immunotherapy.

Overview of tumor immunity

In 2013, Chen and Mellman proposed a model of the “cancer-immunity cycle,” a multi-step process that includes the release of cancer cell antigens, antigen presentation, priming and activation of T-cells, trafficking of T-cells to tumors, and recognition and killing of cancer cells by cytotoxic T-lymphocytes (CTLs) (1). This model of tumor immunity, though simplified and lacking other important players like natural killer cells, provides an organized approach to identifying vulnerabilities capitalized by cancer cells. The best-studied examples thus far include inhibition of T-cell activation through cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA-4) and exhaustion of T-cell effector function through programmed death 1 (PD-1) receptor signaling. Therapeutic anti-CTLA-4 (ipilimumab) and anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibodies (nivolumab, pembrolizumab) have proven successful in the clinic. However, these checkpoint inhibitors are collectively only approved for melanoma, renal cell carcinoma (RCC), non-small cell lung cancer, and Hodgkin lymphoma. Typically, only 15–40% of patients respond favorably to checkpoint inhibitor monotherapy (2–4), though response rates up to 61% have been reported for combination ipilimumab and nivolumab therapy (4). Thus, it is clear that other critical factors in tumor immunity have yet to be characterized and explored as targets.

The Eph receptor tyrosine kinase family

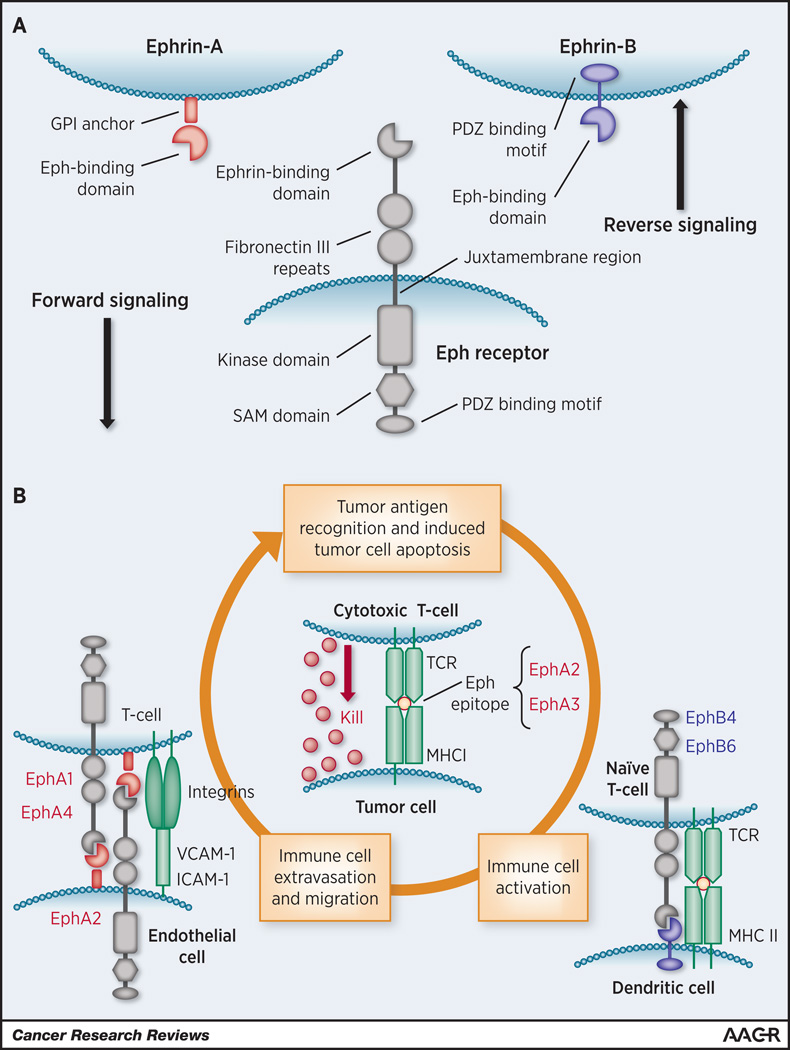

The Eph receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) family comprises the largest group of surface receptors and are categorized into EphA or EphB subclasses based on sequence homology and preferential binding to their ephrin-A and ephrin-B ligands, respectively (5). In humans, nine EphA (EphA1-8,10) and five EphB (EphB1-4,6) receptors are expressed, along with five ephrin-A and three ephrin-B ligands. Unlike most RTKs, Eph receptors interact with ligands that are often membrane-bound, allowing both “forward signaling” in the receptor-bound cell and “reverse signaling” in the ephrin-bound cell (Figure 1A). In addition to “forward signaling,” Eph receptors can signal in the absence of ligand binding and kinase activation through cross-talk with other RTKs, such as HER2 (6,7). Eph receptors are involved in a wide range of physiological and pathological processes, including inflammation and cancer. Although their roles in immune cell development, migration, and activation (8,9), as well as their involvement in tumorigenesis, tumor angiogenesis, and cancer stem cells (10–12), have been reviewed extensively, the junction between these two areas has yet to be rigorously examined. Here, we attempt to bridge this gap and provide the first comprehensive review of Eph RTKs in the context of tumor immunity.

Figure 1.

A) Structural elements of an Eph receptor and ephrin ligands. B) Graphical summary of potential roles of Eph receptors in the cancer-immunity cycle. Eph receptors are sources of immunogenic TAAs. Interaction between ephrin and Eph receptor in the vasculature could regulate lymphocyte trafficking to tumor. In addition, EphB receptors can serve as co-stimulation molecules to stimulate T cell activation in tumor microenvironment.

Eph receptor-derived tumor-associated antigens

The first Eph receptor identified as a tumor-associated antigen (TAA) was EphA3 (13), which is overexpressed in several malignancies, including melanoma. In this study, a CD4+ T-cell clone isolated from a melanoma patient with an exceptionally favorable clinical course was found to recognize an EphA3 epitope and elicit selective immunoreactivity against melanoma cell lines.

Subsequently, EphA2 has become the best-studied source of TAAs in the Eph family (Figure 1B). At baseline expression levels, EphA2 typically binds its main ligand ephrin-A1 and facilitates epithelial cell-to-cell adhesion. However, when overexpressed in many solid tumors, such as melanoma, glioma, RCC, and breast and lung cancer, EphA2 signals in a ligand-independent fashion through cross-talk with EGFR and HER2, and promotes tumor growth and angiogenesis (7,14).

Multiple EphA2-derived epitopes are recognized by human CD4+ or CD8+ T-cells (15,16). One particular epitope (EphA2883–891) from the C-terminus of human EphA2 induces significant immunoreactivity in CD8+ T-cells via MHC I-restricted presentation against RCC and glioma cell lines in vitro (15,17,18). Reactive T-cell clones were isolated from both healthy donors and patients with glioma or RCC; however, they were only identified after ex vivo expansion and antigen stimulation. Whether these EphA2883–891-specific T-cells are generated spontaneously and confer antitumor activity in humans remains unknown. Further investigation will likely require a more direct and sensitive method of detecting specific T-cell clones while minimizing ex vivo manipulation.

These early studies led to several preclinical investigations adopting vaccinations with EphA2 peptide-pulsed dendritic cells (DCs) in mouse tumor models of syngeneic glioma, sarcoma, melanoma, and colorectal carcinoma (19–21). Additionally, ephrin-A1 has been used to activate DCs in a rat glioma model (22). The data from these preclinical models suggest that these DC vaccines induce immune responses and decrease tumor burden, though the findings invite further investigation. In these studies, antigen-specific cytotoxic T-cell clones were isolated from vaccinated animals, and in vivo depletion of CD8+ T-cells blocked the reduction in tumor size induced by vaccination. However, both primary tumor and metastasis models in these cases were non-orthotopic and not ideal representations of human disease. Furthermore, none of the studies analyzed tumor-infiltrating immune populations or reported on the effects on survival. Interestingly, the mouse EphA2 peptides used to stimulate DCs in these studies are not homologous to EphA2883–891 in humans. This highlights the differences in MHC molecules across species and their different binding affinities for peptides, which becomes a significant barrier to translating these models into treatments for patients. Thus, future research in this area will likely benefit from using humanized mouse models.

A few studies mentioned above (17–19) have led EphA2 to become a prominent target for immunotherapy in glioma and provided rationale for clinical trials to test the safety of combination peptide vaccines with EphA2883–891 plus other TAAs in patients with gliomas (23–25). Reports on toxicity and preliminary efficacy demonstrate that the peptide vaccinations are generally well-tolerated and elicit clinical and immunologic T-cell responses. However, the data contains wide interpatient variability and does not control for key confounding factors, such as prior chemotherapy and/or radiation regimens, that can have a notable impact on immune function. Later phase trials will hopefully provide greater insight on the efficacy of combination peptide vaccines in patients with glioma. Currently, a vaccine trial testing a group of TAAs, including EphA2883–891, in combination with dasatinib, an inhibitor of Src and EphA2, is ongoing in patients with melanoma (26). Despite these advances, EphA2883–891 and other TAAs used in peptide vaccines can only be presented and potentially induce responses in patients with the MHC I haplotype HLA-A2. This greatly limits the patient population that may respond to such therapies.

Although the discussion thus far has focused on CTL function in relation to TAA immunogenicity, a few studies also examine the roles of other immune cell subsets, such as CD4+ T-cells. For example, Tatsumi et al. identifies MHC II-restricted EphA2 epitopes and examines the immunoreactivity of CD4+ T-cell subsets from RCC patients against these peptides (15). They found that Th1 polarization of CD4+ T-cells is greater in patients with stage I disease, while Th2 polarization and regulatory T-cells (Treg) differentiation, both generally considered to be immunosuppressive and tumor-promoting responses, are increased in patients with more advanced disease. In in vivo models, Yamaguchi et al. provide preliminary evidence that CD4+ T-cells can partially mediate antitumor responses induced by EphA2 peptide-pulsed DCs (20,21). Further elucidation of the effects of EphA2 peptide and DC vaccines on T-cell subsets, as well as novel investigations on other immune cell populations, will broaden our understanding of the mechanisms and advance development of these anticancer therapies.

Eph receptor-mediated immune cell trafficking

Besides inducing immunologic responses, Eph receptors can regulate immune cell trafficking. EphA2 is expressed on endothelial cells and may mediate lymphocyte adhesion to vessel walls, the first step in lymphocyte extravasation. Expression of both EphA2 and its main ligand ephrin-A1 is upregulated in activated endothelium in vitro, and stimulation of EphA2 signaling through ephrin-A1 binding leads to increased expression of adhesion proteins, such as E-selectin and VCAM-1, that bind to leukocyte integrins (27). Conversely, EphA2 binding to ephrin-A1 on T-cells results in reverse signaling that promotes T-cell adhesion to VCAM-1 and another vascular adhesion protein ICAM-1 (28) (Figure 1B). However, these interactions have not been tested in a co-culture system or transendothelial migration model. Although cursory evidence suggests that EphA2 signaling may be modulating the NF-κB pathway to affect expression of adhesion proteins (29), further mechanistic studies are needed to elucidate the signaling pathways downstream of both EphA2 and ephrin-A1 that may lead to changes in lymphocyte adhesion to endothelial cells. Furthermore, since these in vitro studies were conducted in the context of atherosclerosis, whether the adhesion induced by EphA2 and ephrin-A1 binding facilitates lymphocyte extravasation through activated tumor vessels remains to be investigated.

In addition to in vitro investigations, the interaction between ephrin-A1 and EphA2 has been studied in various lung injury and inflammation mouse models (29,30); however, their effects on lung vasculature remain equivocal and are likely model-dependent. For example, Carpenter et al. report that EphA2 knockout mice have reduced vascular permeability, immune cell infiltration, and chemokine production in a bleomycin-induced lung injury model (29), while Okazaki et al. conclude that the same knockout mice have increased immune cell infiltration and inflammatory cytokine production in Mycoplasma and ovalbumin-induced inflammatory lung models compared to their wild-type counterparts (30). Further in vivo studies are needed to clarify the effect of EphA2 in the lung vasculature.

Two other binding partners of ephrin-A1 are EphA1 and EphA4, which are expressed in T-cells and mediate T-cell chemotaxis in vitro (31–33) (Figure 1B). Ephrin-A1 stimulation of CD4+ and CD8+ T-cells promotes chemotaxis in response to stromal cell-derived factor 1α (SDF-1α)/CXCL12 and macrophage inflammatory protein 3β (MIP-3β)/CCL19 in vitro. EphA1 is expressed on CD4+ and CD8+ T-cells and facilitates migration of both T-cell subsets via recruitment of FAK-like kinase Pyk2, Src kinase Lck, Rho-GEF Vav1, and PI3K (31,32). On the other hand, EphA4 is not expressed on CD8+ T-cells but facilitates CD4+ T-cell migration through activation of Vav1 and Src kinases Lck and Fyn, as well as potential dimerization with EphA1 (32,33). Surprisingly, administration of a pan-Src inhibitor appears to increase T-cell chemotaxis in response to CCL19 and CXCL12 (31,32). These chemokines both regulate lymphocyte homing, though CXCL12 in particular is overexpressed in several types of cancer and can promote tumor growth, metastasis and angiogenesis through signaling of its receptor CXCR4 on cancer cells (34). Thus, evaluation of EphA receptor roles in T-cell recruitment to tumors, especially those that are driven by CXCL12/CXCR4, may provide additional insight in the immune microenvironment of these tumors.

While the association between EphA receptors and T-cell trafficking is well-established, some evidence suggests that EphB receptors regulate monocyte migration. Interactions between ephrin-B2 on endothelial cells and EphB4 expressed on monocytes inhibit their chemotaxis and transendothelial migration (35,36). Though these studies are framed in the context of atherosclerosis, ephrin-B2 also plays a crucial role in angiogenesis through regulation of VEGFR signaling (37,38) and may affect monocyte trafficking through the tumor vasculature. In addition to T-cell and monocyte recruitment, there is sparse literature on Eph/ephrin involvement in trafficking of other immune cells, mainly B-cells (39) and dendritic cells (40).

Although these investigations examining Ephs/ephrins in immune cell chemotaxis and migration have not utilized cancer models, much of the understanding gained from this work can be easily applied and tested in the context of tumor immunity. EphA/ephrin-A1 interactions between lymphocytes and endothelial cells may play a role in lymphocyte infiltration of tumors, while EphB/ephrin-B2 may have similar functions in monocytes and tumor-associated macrophages. Additional research in Eph/ephrin interactions in the immune system will help redress inconsistencies in our current understanding and perhaps reveal novel targets in the tumor microenvironment or treatment strategies.

Eph receptors in immune cell activation

The balance between costimulatory and inhibitory signals from DCs to naïve T-cells can direct the fate of T-cells towards differentiation into a tumor fighting or immunosuppressive subclass, like Tregs, or apoptosis, leading to immune tolerance of tumor cells. Although little is known about EphB/ephrin-B interactions in facilitating T-cell trafficking, their role in T-cell costimulation has been well-characterized (41–45) (Figure 1B).

In murine T-cells, in vitro stimulation of EphB receptors by ephrin-B1, B2, or B3 leads to EphB co-localization with the T-cell receptor (TCR) complex and T-cell activation, indicated by MAPK pathway signaling, T-cell proliferation, IFN-γ secretion, and cytotoxic activity (41–43). Likewise, stimulation of EphB6 expressed on human T-cells with ephrin-B2 yields similar results (44). EphB6 activation leads to increased expression of T-cell activation markers CD25 and CD69 and secretion of several proinflammatory cytokines, including IFN-γ and TNF-α, though not IL-2, the main cytokine upregulated in T-cells by canonical APC costimulation. The traditional costimulatory B7 molecules on DCs induce IL-2 transcription in T-cells and their survival, whereas other costimulatory receptors, such as those in the TNF receptor family, promote proliferation and differentiation without affecting IL-2 levels. Thus, EphB6 appears to function similarly to this last group of costimulatory receptors and, because it promotes IFN-γ secretion and cytotoxic activity, may promote CTL differentiation. Further evidence of this is demonstrated in EphB6 knockout mice that have impaired T-cell activation and function and reduced TCR downstream signaling proteins, such as activated ZAP-70, LAT, PLC-γ, and Erk1/2 (45).

Despite the evidence presented in these studies, EphB/ephrin-B involvement in T-cell activation is likely more complex. For example, other EphB receptors expressed on T-cells, such as EphB4, may share redundant functions with EphB6 in stimulating T-cell proliferation (45). Moreover, the concentration of available ephrin-B1 and B2 may modulate costimulatory function. Kawano et al. show that high concentrations of ephrin-B1 and B2, though not ephrin-B3, can inhibit instead of stimulate T-cell activation through EphB4 signaling (46). Nguyen et al. report that ephrin-B2 and EphB2 expressed on mesenchymal stromal/stem cells (MSCs) can suppress T-cell activation via interaction with EphB4 and ephrin-B1 on T-cells, respectively (47). The collective interactions of EphBs and ephrin-Bs between T-cells and MSCs increase expression of TGF-β1, indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO), and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), all three of which are immunosuppressive factors that can promote tumor immune evasion (48).

Besides EphB/ephrin-B involvement in T-cell costimulation and suppression, very little is known about the roles of other Eph receptors in activating immune cells, except scant evidence suggesting that EphA2 expressed on dendritic cells may help activate B-cells (49). Given the overwhelming evidence of EphB/ephrin-B engagement in T-cell costimulation, the activation of T-cells against TAAs and their differentiation into tumor-suppressing CTLs may be affected by EphB/ephrin-B interactions. Further investigation in this area using cancer models may provide insight into how we may capitalize on Eph/ephrin relationships to accentuate the antitumor immune response.

Concluding Remarks

Eph receptors are sources of immunogenic TAAs and have critical functions in the immune system that likely impact the tumor immune microenvironment (Figure 1B). Thus, modulating Eph receptor activities, in principle, could be leveraged to improve tumor immune therapies. However, much is still unknown about how Eph receptors regulate tumor immunity. First, many of the studies investigating Eph receptors in immune responses have yet to be translated in cancer models. Second, since the EphA2 receptor is often not mutated in human cancer, it is unclear if the immune system distinguishes EphA2 peptide-MHC complexes on tumor cells from those on normal tissue. Third, Eph receptor kinase inhibitors have been developed (50,51), but their impact on the immune system is unknown. Finally, while EphA2 is expressed on dendritic cells (40), its role in tumor immunity remains to be investigated. In summary, although there is abundant literature on Eph receptors and ephrins in cancer biology, as well as immunology, this family of RTKs is highly understudied in the context of tumor immunity. This gap in our current knowledge identifies a distinct opportunity for new discoveries that may advance our understanding of the tumor microenvironment and pave the way for novel immunotherapeutic targets.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs through a VA Merit Award and a Research Career Scientist Award (J. Chen), NIH grants R01 CA95004 and CA177681 (J. Chen) and T32 GM0734 (NIH/National Institute of General Medical Sciences) (E. Shiuan), and a Breast Cancer Program pilot project from the Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center.

Footnotes

Potential conflicts of interest: We have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose

References

- 1.Chen Daniel S, Mellman I. Oncology Meets Immunology: The Cancer-Immunity Cycle. Immunity. 2013;39(1):1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Topalian SL, Hodi FS, Brahmer JR, Gettinger SN, Smith DC, McDermott DF, et al. Safety, Activity, and Immune Correlates of Anti–PD-1 Antibody in Cancer. New England Journal of Medicine. 2012;366(26):2443–2454. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Larkin J, Chiarion-Sileni V, Gonzalez R, Grob JJ, Cowey CL, Lao CD, et al. Combined Nivolumab and Ipilimumab or Monotherapy in Untreated Melanoma. New England Journal of Medicine. 2015;373(1):23–34. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1504030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Postow MA, Chesney J, Pavlick AC, Robert C, Grossmann K, McDermott D, et al. Nivolumab and Ipilimumab versus Ipilimumab in Untreated Melanoma. New England Journal of Medicine. 2015;372(21):2006–2017. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1414428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kania A, Klein R. Mechanisms of ephrin-Eph signalling in development, physiology and disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2016;17(4):240–256. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2015.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arvanitis D, Davy A. Eph/ephrin signaling: networks. Genes & Development. 2008;22(4):416–429. doi: 10.1101/gad.1630408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brantley-Sieders DM, Zhuang G, Hicks D, Fang WB, Hwang Y, Cates JMM, et al. The receptor tyrosine kinase EphA2 promotes mammary adenocarcinoma tumorigenesis and metastatic progression in mice by amplifying ErbB2 signaling. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 118(1):64–78. doi: 10.1172/JCI33154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wu J, Luo H. Recent advances on T-cell regulation by receptor tyrosine kinases. Current Opinion in Hematology. 2005;12(4):292–297. doi: 10.1097/01.moh.0000166497.26397.9f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Funk SD, Orr AW. Ephs and ephrins resurface in inflammation, immunity, and atherosclerosis. Pharmacological Research. 2013;67(1):42–52. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2012.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen J, Zhuang G, Frieden L, Debinski W. Eph Receptors and Ephrins in Cancer: Common Themes and Controversies. Cancer Research. 2008;68(24):10031–10033. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pasquale EB. Eph receptors and ephrins in cancer: bidirectional signalling and beyond. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10(3):165–180. doi: 10.1038/nrc2806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen J, Song W, Amato K. Eph receptor tyrosine kinases in cancer stem cells. Cytokine & Growth Factor Reviews. 2015;26(1):1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2014.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chiari R, Hames G, Stroobant V, Texier C, Maillère B, Boon T, et al. Identification of a Tumor-specific Shared Antigen Derived From an Eph Receptor and Presented to CD4 T Cells on HLA Class II Molecules. Cancer Research. 2000;60(17):4855–4863. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miao H, Li D-Q, Mukherjee A, Guo H, Petty A, Cutter J, et al. EphA2 Mediates Ligand-Dependent Inhibition and Ligand-Independent Promotion of Cell Migration and Invasion via a Reciprocal Regulatory Loop with Akt. Cancer cell. 2009;16(1):9–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tatsumi T, Herrem CJ, Olson WC, Finke JH, Bukowski RM, Kinch MS, et al. Disease Stage Variation in CD4+ and CD8+ T-Cell Reactivity to the Receptor Tyrosine Kinase EphA2 in Patients with Renal Cell Carcinoma. Cancer Research. 2003;63(15):4481–4489. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alves PMS, Faure O, Graff-Dubois S, Gross D-A, Cornet S, Chouaib S, et al. EphA2 as Target of Anticancer Immunotherapy: Identification of HLA-A*0201-Restricted Epitopes. Cancer Research. 2003;63(23):8476–8480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hatano M, Eguchi J, Tatsumi T, Kuwashima N, Dusak JE, Kinch MS, et al. EphA2 as a Glioma-Associated Antigen: A Novel Target for Glioma Vaccines. Neoplasia. 2005;7(8):717–722. doi: 10.1593/neo.05277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang JG, Eguchi J, Kruse CA, Gomez GG, Fakhrai H, Schroter S, et al. Antigenic Profiling of Glioma Cells to Generate Allogeneic Vaccines or Dendritic Cell – Based Therapeutics. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2007;13(201):566–575. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hatano M, Kuwashima N, Tatsumi T, Dusak JE, Nishimura F, Reilly KM, et al. Vaccination with EphA2-derived T cell-epitopes promotes immunity against both EphA2-expressing and EphA2-negative tumors. Journal of Translational Medicine. 2004;2(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-2-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yamaguchi S, Tatsumi T, Takehara T, Sakamori R, Uemura A, Mizushima T, et al. Immunotherapy of murine colon cancer using receptor tyrosine kinase EphA2-derived peptide-pulsed dendritic cell vaccines. Cancer. 2007;110(7):1469–1477. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yamaguchi S, Tatsumi T, Takehara T, Sasakawa A, Hikita H, Kohga K, et al. Dendritic cell-based vaccines suppress metastatic liver tumor via activation of local innate and acquired immunity. Cancer Immunology, Immunotherapy. 2008;57(12):1861–1869. doi: 10.1007/s00262-008-0514-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li M, Wang B, Wu Z, Shi X, Zhang J, Han S. Treatment of Dutch rat models of glioma using EphrinA1-PE38/GM-CSF chitosan nanoparticles by in situ activation of dendritic cells. Tumor Biology. 2015;36(10):7961–7966. doi: 10.1007/s13277-015-3486-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pollack IF, Jakacki RI, Butterfield LH, Hamilton RL, Panigrahy A, Potter DM, et al. Antigen-Specific Immune Responses and Clinical Outcome After Vaccination With Glioma-Associated Antigen Peptides and Polyinosinic-Polycytidylic Acid Stabilized by Lysine and Carboxymethylcellulose in Children With Newly Diagnosed Malignant Brainstem and Nonbrainstem Gliomas. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2014;32(19):2050–2058. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.54.0526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Okada H, Butterfield LH, Hamilton RL, Hoji A, Sakaki M, Ahn BJ, et al. Induction of Robust Type-I CD8+ T-cell Responses in WHO Grade 2 Low-Grade Glioma Patients Receiving Peptide-Based Vaccines in Combination with Poly-ICLC. Clinical Cancer Research. 2015;21(2):286–294. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-1790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pollack IF, Jakacki RI, Butterfield LH, Hamilton RL, Panigrahy A, Normolle DP, et al. Immune responses and outcome after vaccination with glioma-associated antigen peptides and poly-ICLC in a pilot study for pediatric recurrent low-grade gliomas. Neuro-Oncology. 2016 doi: 10.1093/neuonc/now026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Storkus W. Dendritic cell vaccines + dasatinib for metastatic melanoma. [Accessed 2016 May 1];2016 May 1; < https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01876212 NLM Identifier: NCT01876212>.

- 27.Funk SD, Yurdagul A, Albert P, Traylor JG, Jin L, Chen J, et al. EphA2 Activation Promotes the Endothelial Cell Inflammatory Response: A Potential Role in Atherosclerosis. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. 2012;32(3):686–695. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.242792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sharfe N, Nikolic M, Cimpeon L, Van De Kratts A, Freywald A, Roifman CM. EphA and ephrin-A proteins regulate integrin-mediated T lymphocyte interactions. Molecular Immunology. 2008;45(5):1208–1220. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2007.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carpenter TC, Schroeder W, Stenmark KR, Schmidt EP. Eph-A2 Promotes Permeability and Inflammatory Responses to Bleomycin-Induced Lung Injury. American Journal of Respiratory Cell and Molecular Biology. 2012;46(1):40–47. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2011-0044OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Okazaki T, Ni A, Baluk P, Ayeni OA, Kearley J, Coyle AJ, et al. Capillary Defects and Exaggerated Inflammatory Response in the Airways of EphA2-Deficient Mice. The American Journal of Pathology. 2009;174(6):2388–2399. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aasheim H-C, Delabie J, Finne EF. Ephrin-A1 binding to CD4+ T lymphocytes stimulates migration and induces tyrosine phosphorylation of PYK2. Blood. 2005;105(7):2869–2876. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-08-2981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hjorthaug HS, Aasheim H-C. Ephrin-A1 stimulates migration of CD8+CCR7+ T lymphocytes. European Journal of Immunology. 2007;37(8):2326–2336. doi: 10.1002/eji.200737111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Holen HL, Nustad K, Aasheim H-C. Activation of EphA receptors on CD4+CD45RO+ memory cells stimulates migration. Journal of Leukocyte Biology. 2010;87(6):1059–1068. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0709497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Guo F, Wang Y, Liu J, Mok SC, Xue F, Zhang W. CXCL12/CXCR4: a symbiotic bridge linking cancer cells and their stromal neighbors in oncogenic communication networks. Oncogene. 2016;35(7):816–826. doi: 10.1038/onc.2015.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pfaff D, Héroult M, Riedel M, Reiss Y, Kirmse R, Ludwig T, et al. Involvement of endothelial ephrin-B2 in adhesion and transmigration of EphB-receptor-expressing monocytes. Journal of Cell Science. 2008;121(22):3842–3850. doi: 10.1242/jcs.030627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Korff T, Braun J, Pfaff D, Augustin HG, Hecker M. Role of ephrinB2 expression in endothelial cells during arteriogenesis: impact on smooth muscle cell migration and monocyte recruitment. Blood. 2008;112(1):73–81. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-12-128835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang Y, Nakayama M, Pitulescu ME, Schmidt TS, Bochenek ML, Sakakibara A, et al. Ephrin-B2 controls VEGF-induced angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis. Nature. 2010;465(7297):483–486. doi: 10.1038/nature09002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sawamiphak S, Seidel S, Essmann CL, Wilkinson GA, Pitulescu ME, Acker T, et al. Ephrin-B2 regulates VEGFR2 function in developmental and tumour angiogenesis. Nature. 2010;465(7297):487–491. doi: 10.1038/nature08995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Trinidad EM, Ballesteros M, Zuloaga J, Zapata A, Alonso-Colmenar LM. An impaired transendothelial migration potential of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) cells can be linked to ephrin-A4 expression. Blood. 2009;114(24):5081–5090. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-03-210617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.de Saint-Vis B, Bouchet C, Gautier G, Valladeau J, Caux C, Garrone P. Human dendritic cells express neuronal Eph receptor tyrosine kinases: role of EphA2 in regulating adhesion to fibronectin. Blood. 2003;102(13):4431–4440. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-02-0500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yu G, Luo H, Wu Y, Wu J. Ephrin B2 Induces T Cell Costimulation. The Journal of Immunology. 2003;171(1):106–114. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.1.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yu G, Luo H, Wu Y, Wu J. Mouse EphrinB3 Augments T-cell Signaling and Responses to T-cell Receptor Ligation. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003;278(47):47209–47216. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306659200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yu G, Luo H, Wu Y, Wu J. EphrinB1 Is Essential in T-cell-T-cell Co-operation during T-cell Activation. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2004;279(53):55531–55539. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410814200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Luo H, Yu G, Wu Y, Wu J. EphB6 crosslinking results in costimulation of T cells. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2002;110(8):1141–1150. doi: 10.1172/JCI15883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Luo H, Yu G, Tremblay J, Wu J. EphB6-null mutation results in compromised T cell function. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2004;114(12):1762–1773. doi: 10.1172/JCI21846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kawano H, Katayama Y, Minagawa K, Shimoyama M, Henkemeyer M, Matsui T. A novel feedback mechanism by Ephrin-B1/B2 in T-cell activation involves a concentration-dependent switch from costimulation to inhibition. European Journal of Immunology. 2012;42(6):1562–1572. doi: 10.1002/eji.201142175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nguyen TM, Arthur A, Hayball JD, Gronthos S. EphB and Ephrin-B Interactions Mediate Human Mesenchymal Stem Cell Suppression of Activated T-Cells. Stem Cells and Development. 2013;22(20):2751–2764. doi: 10.1089/scd.2012.0676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Joyce JA, Fearon DT. T cell exclusion, immune privilege, and the tumor microenvironment. Science. 2015;348(6230):74–80. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa6204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Aasheim H-C, Munthe E, Funderud S, Smeland EB, Beiske K, Logtenberg T. A splice variant of human ephrin-A4 encodes a soluble molecule that is secreted by activated human B lymphocytes. Blood. 2000;95(1):221–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Choi Y, Syeda F, Walker JR, Finerty PJ, Jr, Cuerrier D, Wojciechowski A, et al. Discovery and structural analysis of Eph receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters. 2009;19(15):4467–4470. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2009.05.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Amato KR, Wang S, Hastings AK, Youngblood VM, Santapuram PR, Chen H, et al. Genetic and pharmacologic inhibition of EPHA2 promotes apoptosis in NSCLC. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 124(5):2037–2049. doi: 10.1172/JCI72522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]