Summary

Coeliac disease (CD) is an autoimmune enteropathy triggered by gluten and characterized by a strong T helper type 1 (Th1)/Th17 immune response in the small intestine. Regulatory T cells (Treg) are CD4+CD25++forkhead box protein 3 (FoxP3+) cells that regulate the immune response. Conversely to its counterpart, FoxP3 full length (FL), the alternatively spliced isoform FoxP3 Δ2, cannot properly down‐regulate the Th17‐driven immune response. As the active state of CD has been associated with impairments in Treg cell function, we aimed at determining whether imbalances between FoxP3 isoforms may be associated with the disease. Intestinal biopsies from patients with active CD showed increased expression of FOXP3 Δ2 isoform over FL, while both isoforms were expressed similarly in non‐coeliac control subjects (HC). Conversely to what we saw in the intestine, peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) from HC subjects did not show the same balance between isoforms. We therefore hypothesized that the intestinal microenvironment may play a role in modulating alternative splicing. The proinflammatory intestinal microenvironment of active patients has been reported to be enriched in butyrate‐producing bacteria, while high concentrations of lactate have been shown to characterize the preclinical stage of the disease. We show that the combination of interferon (IFN)‐γ and butyrate triggers the balance between FoxP3 isoforms in HC subjects, while the same does not occur in CD patients. Furthermore, we report that lactate increases both isoforms in CD patients. Collectively, these findings highlight the importance of the ratio between FoxP3 isoforms in CD and, for the first time, associate the alternative splicing process mechanistically with microbial‐derived metabolites.

Keywords: autoimmunity, celiac disease, microbiome, Treg

Introduction

Regulatory T cells (Treg) represent a subset of CD4+ T cells that control the immune response to foreign antigens and maintain self‐tolerance 1, 2. Treg cells can mediate suppression of responder cells through different mechanisms, including the production of immunosuppressive cytokines, the consumption of IL‐2 and the down‐regulation of co‐stimulatory molecules on antigen‐presenting cells (APC) 3. The nuclear transcription factor forkhead box protein 3 (FoxP3) has been described to be fundamental in regulating the differentiation and function of Treg cells 4, 5. Indeed, mutations located on the FOXP3 gene have been associated with the onset of several autoimmune diseases, such as immune dysregulation, polyendocrinopathy, enteropathy, X‐linked syndrome (IPEX), type 1 diabetes, Grave's disease and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) 6, 7, 8, 9, 10. Like other members of the Fox protein family, FoxP3 is characterized by a highly conserved forkhead DNA‐binding domain, a leucine zipper‐like domain and a zinc finger motif. Finally, a unique proline‐rich repressor domain is located on the N‐terminal region 11. This domain plays a fundamental role in modulating the regulatory functions of FoxP3 by interacting with other transcription factors 11, 12, 13. Furthermore, it has been shown to be important for maintaining the anergic state of Treg cells 14 and regulating the balance between Treg and T helper type 17 (Th17) cells 15, 16, 17.

Several FoxP3 alternatively spliced isoforms have been described. They are present only in human cells, and no animal counterparts have been reported 18. The most common isoforms are the full‐length (FL) and Delta 2 (Δ2), which lacks exon 2 17, 18, 19. Although both these isoforms have been shown to confer some suppressive ability to Treg cells 18, they seem to have functional differences. Exon 2 is located on the N‐terminal repressor domain and contains the binding site for retinoic acid‐related orphan receptors (RORγT and RORαT). By interacting with RORαT and RORγT, FoxP3 FL down‐regulates their expression and inhibits Th17 differentiation, while FoxP3 Δ2 does not 17.

Coeliac disease (CD) is an autoimmune enteropathy triggered by ingestion of gluten in genetically predisposed individuals 20, 21. Th1 cells are known to be important players in the cascade of events that leads to intestinal inflammation in CD patients by producing proinflammatory cytokines interferon (IFN)‐γ and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)‐α 22, 23. IFN‐γ is also produced in large amounts by CD8+ intraepithelial lymphocytes (IELs). These cells are expanded in the small intestine of active coeliac patients and contribute to the pathogenesis of the disease not only by secreting proinflammatory cytokines, but also through cytolytic proteins such as perforin and granzymes 20, 24. Recently, Th17‐associated cytokines have also been reported to be increased in the small intestinal mucosa of active CD patients 25, 26, 27, therefore suggesting a role of Th17 cells in the pathogenesis of CD. While deficiencies in the population of Treg cells have been associated with other autoimmune diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) 28, CD is characterized by an increased number of FoxP3+ cells in the lamina propria of the small intestine 29, 30. Several groups have shown that their suppressive function is impaired significantly 31, 32, 33, but the exact mechanisms behind these deficiencies are not understood fully. In the present study, we show that in CD patients the Δ2 isoform is over‐expressed compared to FL in FoxP3‐positive cells homing in the gut mucosa and that the intestinal microenvironment, characterized by high production of proinflammatory cytokines and specific microbial‐derived metabolites, may contribute to this disequilibrium. This evidence is the first instance of linking changes in the intestinal microenvironment to host epigenetic modifications associated mechanistically with immune surveillance.

Methods

Human subjects

Whole blood was obtained by venipuncture from adult patients aged between 16 and 65 years and distributed similarly between both sexes during routine visits to our clinic at Massachusetts General Hospital. Patients included non‐coeliac control subjects (HC), coeliac patients in remission following a gluten‐free diet (CDGF) with normal duodenal pathology (Marsh 0–II) and coeliac patients with active disease (CDA). Small intestinal biopsies were obtained from the second portion of the duodenum according to standard clinical procedure from HC, CDGF and CDA during clinically indicated upper endoscopic procedures. Patients with CD in the cohort were diagnosed based on pathological evaluation (Marsh III at time of diagnosis) and positive serology results for anti‐human tissue transglutaminase immunoglobulin (Ig)A antibodies (Inova Diagnostics Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) (the manufacturer's instructions were followed and samples were evaluated as positive if values of TtG‐IgA ≥20 were detected). Patients were considered CDGF if, at the time of specimen collection, they have been following a gluten‐free diet for at least 6 months and presented negative serology and normal intestinal mucosa (Marsh 0–II).

Peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) isolation and stimulation

PBMC were isolated from whole blood samples by density gradient centrifugation over Ficoll (GE Healthcare, Rahway, NJ, USA) and cultured (1 × 106 cells/ml) for 24 or 48 h in complete medium RPMI‐1640 Dutch modification (Gibco, Carlsbad, CA, USA), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Sigma‐Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA), 1% L‐glutamine, 1% penicilin/streptomycin, 1% sodium pyruvate and 1% non‐essential amino acid solution (Gibco) with 1 mg/ml of previously digested gliadin (Sigma) 34, 100 ng/ml of IFN‐γ (eBioscience, San Diego, CA, USA), 1 μg/ml lactate (Sigma) or butyrate (Sigma) and a combination of IFN‐γ and butyrate at 37°C, 5% CO2.

Isolation and stimulation of CD4+CD25– and CD4+CD25+ T cells form peripheral blood and flow cytometry

CD4+CD25– and CD4+CD25+ T cells were isolated from PBMC with the dynabeads CD4+CD25+ Treg cells isolation kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). CD4+CD25– T cells were isolated by negative selection and stimulated with 1 μg/ml of lactate or with a combination of 1 μg/ml of butyrate and 100 ng/ml of IFN‐γ for 48 h in complete RPMI‐1640 medium enriched with 10% FBS, 50 U/ml of recombinant IL‐2 (rIL2) (eBioscience) and CD3/CD28 dynabeads (Invitrogen). Treg cells were isolated by positive selection, expanded in complete RPMI‐1640 medium enriched with 10% FBS, 500 U/ml of rIL‐2, CD3/CD28 dynabeads and cultured with the different stimuli for 48 h. Purity of the different T cell populations was higher than 90% and determined by flow cytometry. Briefly, isolated T cells were stained with antibodies peridinin chlorophyll (PerCP)‐conjugated anti‐CD4 (eBioscience) and phycoerythrin (PE)‐conjugated anti‐CD25 (eBioscience). Cells were then permeabilized with the FoxP3 staining kit (eBioscience) and stained for FoxP3 following the manufacturer's instructions. Detection of CD4+CD25–FoxP3– and CD4+CD25++FoxP3+ cells was performed with BD Bioscience software.

Isolation of CD4+ cells from small intestinal biopsies

For each patient four biopsies were collected in ice‐cold RPMI‐1640 complete medium enriched with 10% FBS. The specimens were then incubated for 20 min at room temperature in calcium and magnesium‐free Hanks’ balanced salt solution (HBSS) 1× (Gibco) and 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT) to eliminate mucus in excess. Biopsies were then incubated twice at 37°C for 30 min under tilting in calcium and magnesium‐free HBSS 1× and 1 mM ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA) (Ambion, Foster City, CA, USA) to remove the epithelium. Each incubation was followed by a brief wash in calcium and magnesium‐free HBSS 1×. Finally, the intestinal lamina propria was incubated up for at least 30 min at 37°C under tilting with RPMI‐1640 complete medium enriched with 2% FBS containing 20 μg/ml of DNAse I (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) and 1 mg/ml of collagenase (Sigma). After digestion, PBMC were isolated by Ficoll. The dynabeads CD4+ positive isolation kit was used to isolate CD4+ cells following the manufacturer's instructions (Invitrogen).

RNA extraction and real‐time polymerase chain reaction (PCR)

RNA from PBMC, CD4+CD25– T cells, CD4+CD25+ Treg cells from whole blood and whole biopsies was extracted with Trizol reagent (Ambion), following the manufacturer's directions. Due to the small amount of CD4+ cells isolated from the small intestinal lamina propria, RNA from these samples was extracted with RNAeasy Microkit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA), following the manufacturer's instructions. All RNAs were treated with DNAse I to remove traces amounts of DNA following the manufacturer's instructions (Fermentas, Waltham, MA, USA). For each sample, reverse transcription was performed using the RevertAid First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Fermentas) followed by real‐time PCR (each sample in duplicate) using PerfeCta SYBR Green SuperMix (Quanta Biosciences, Beverly, MA, USA). For the real‐time PCR the following primers were used: human 18S: 5′‐AACCCGTTGAACCCCATT‐3′ (sense) and 5′‐CCATCCAATCGGTAGTAGCG‐3′ (anti‐sense); total FOXP3: 5′‐ATCTACCACTGGTTCACACG‐3′ (sense) and 5′‐CTCCTTTCCTTGATCTTGAG‐3′ (anti‐sense); FOXP3 FL: 5′‐CCATCCAATCGGTAGTAGCG‐3′ (anti‐sense) and 5′‐GCCTTGAGGGAGAAGACC‐3′ (anti‐sense), FOX3 Δ2: 5′ CAGCTGCAGCTCTCAACGGTG ‐3′ (sense) and 5′‐GCCTTGAGGGAGAAGACC‐3′(anti‐sense) 19; RORγT: 5′‐CCTGGGCTCCTGCCTGAC‐3′ (sense) and 5′‐ TCTCTCTGCCCTCAGCCTTGCC‐3′ (anti‐sense); hIL17A: 5′‐ACTACAACCGATCCACCTCAC‐3′ (sense) and 5′‐ACTTTGCCTCCCAGATCACAG‐3′ (anti‐sense); hIL6: 5′‐CCAGAGCTGTGCAGATGATGTA‐3′ (sense) and 5′‐TTGGGTCAGGGGTGGTTATTG‐3′ (anti‐sense); Tbet 5′‐GATGCGCCAGGAAGTTTCAT‐3′ (sense) and 5′‐GCACAATCATCTGGGTCACATT‐3′ (anti‐sense). Total FOXP3 was detected by primers that amplified a region included between exons 10 and 11 of the gene where no alternative splicing sites have been reported; FOXP3 FL was recognized by primers that spanned exon 2 and FOXP3 Δ2 was detected by primers that spanned the junction between exons 1 and 3. Cycling conditions were 10 min at 95°C, followed by 40 cycles of 15 s at 95°C, 30 s at 60°C and 30 s at 72°C, and finally 1 min at 95°C and 1 min at 65°C. Relative expression of the different genes was calculated as 2–ΔΔCt and normalized on housekeeping gene 18S. To measure the ratio between FOXP3 isoforms, we determined the relative expression of each isoform and calculated their ratio individually for each sample (2–ΔΔCtΔ2/2–ΔΔCt FL or 2–ΔΔCtFL/2–ΔΔCtΔ2).

Western blot

Protein lysates from PBMC before and after stimulation with butyrate and IFN‐γ were obtained by lysing the cells in radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer (Sigma) and protease inhibitors cocktail (Roche). Cells were agitated for 15 min at 4°C and centrifuged at 1789 g for 15 min at 4°C. Protein concentrations were measured with the detergent compatible (DC) protein assay (Biorad, Hercules, CA, USA). Samples were denaturated at 95°C for 5 min and separated on 4–20% Novex Tris‐Glycine gels (Life Technologies, Paisley, UK) at 100 V for 2 h. Proteins were then transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes (Life Technologies) using the X Cell Blot Module (Invitrogen) at 25 V for 2 h at 4°C. Membranes were blocked with 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) and incubated with isoform non‐specific α‐FoxP3 (PHC101; eBioscience) at a concentration of 4 μg/ml, followed by washing and incubation with secondary horseradish peroxidase (HRP)‐conjugated antibody (GE Healthcare). Protein bands were visualized by the enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) Western blotting substrate kit (Abcam, Cambridge, UK). Β‐actin protein (α−β actin; Thermo‐Fisher) was used to normalize the relative protein expression.

Statistics

Depending on the sample distribution, statistical analysis of the samples was performed by t‐test, two‐tailed Mann–Whitney test (unpaired samples) and paired t‐test or Wilcoxon's test (paired samples) as appropriate. Standard error of the mean (s.e.m.) was measured to determine the dispersion among data within the same group. In all statistical tests, a P‐value less than 0·05 was considered significant. Correlation between gene expressions was measured by two‐tailed Spearman's or Pearson's correlation analysis, depending on the sample distribution.

Study approval

All protocols were approved by the Partners Human Research Committee Institutional Review Board and written informed consent was obtained from all enrolled subjects.

Results

Altered expression of FoxP3 isoforms in the intestine of active coeliac patients

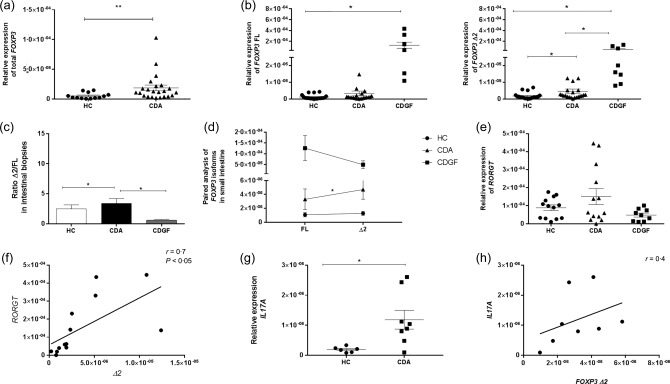

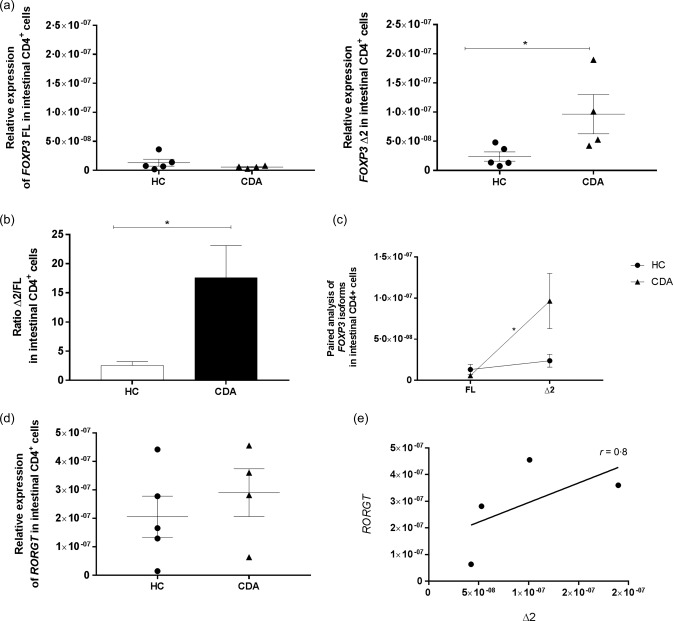

We measured the expression of total FOXP3 in the small intestine of CDA patients and HC subjects and also the expression of each FOXP3 isoform in HC, CDA and CDGF patients by performing a real‐time reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT–PCR). As reported in previous studies, CDA patients showed an increased expression of total FOXP3 compared to HC subjects (P < 0·005) (Fig. 1a). The comparison between CDA and HC showed no differences in the expression of FOXP3 FL, while the Δ2 isoform appeared expressed more significantly in a subgroup of CDA patients compared to the HC (P < 0·05). Interestingly, the analysis in CDGF patients showed that this group of subjects expressed higher levels of both FOXP3 isoforms compared to either HC either CDA subjects (Fig. 1b). The analysis between FOXP3 isoforms ratios (Δ2/FL) showed no differences between HC subjects and CDGF patients, while in CDA patients the ratio between the two isoforms was significantly higher than in the other groups of subjects (P < 0·05) (Fig. 1c). Furthermore, a paired analysis between isoforms revealed that in CDA patients FOXP3 Δ2 was expressed significantly more than its counterpart FL, while in HC and CDGF subjects the two isoforms were expressed similarly (Fig. 1d). The alternatively spliced isoform FoxP3 Δ2 has been described to be less efficient in down‐regulating RORγT expression 17. To evaluate if the elevated intestinal expression of FOXP3 Δ2 that we found in CDA patients matched with a higher expression of RORγT, we performed real time RT–PCR on the mRNA extracted from whole biopsies of HC subjects, CDA and CDGF patients. Although the different expression of RORγT among the groups did not reach statistical significance, it appeared to be higher in a subgroup of CDA patients (Fig. 1e). Furthermore, our data showed a positive correlation between the expression of RORγT and FOXP3 Δ2 in CDA patients (Fig. 1f). Analysis of IL17A mRNA between another set of CDA patients and HC subjects confirmed that the increased RORγT expression that we found in biopsies of CDA patients matched with higher Th17 proinflammatory cytokine IL17A (Fig. 1g). Additionally, we found that in CDA subjects the expression of IL17A was correlated positively with the expression of FOXP3Δ2 (Fig. 1h). To confirm that the differences in FOXP3 isoforms expression that we saw in the whole small intestinal biopsies were due to changes in the Treg population, we isolated CD4+ cells from the small intestinal biopsies of HC and CDA patients and measured the genic expression of both isoforms by real‐time RT–PCR. Our data not only showed a significantly higher expression of FOXP3 Δ2 in CDA compared to HC subjects (P < 0·05) (Fig. 2a), but also confirmed that in CDA patients the less functional isoform is more expressed than its counterpart FL, while in HC subjects the two isoforms are expressed at similar levels (P < 0·05) (Fig. 2b,c). Finally analysis of RORγT expression in the same samples confirmed a higher expression of the Th17 transcription factor in CDA patients (Fig. 2d) that correlated with the expression of the alternatively spliced isoform FOXP3 Δ2 (Fig. 2e).

Figure 1.

Relative expression of forkhead box protein 3 (FOXP3) isoforms, retinoic acid‐related orphan receptors (RORγT) and interleukin (IL) 17A in small intestinal biopsies. Real‐time reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT–PCR) was used to measure the relative expression of total FOXP3 in healthy subjects (HC n = 18) and active coeliac patients (CDA n = 20) (a). Specific primers were used to measure the relative expression of both FOXP3 isoforms separately in HC, CDA and coeliac patients in remission following a gluten‐free diet (CDGF) (n = 8) (b). The ratio between the relative expression of FOXP3 Δ2 and FL (Δ2/FL) was calculated individually for each subject and compared among the three groups of patients. The bars show the mean of the ratios ± standard error of the mean (s.e.m.) in small intestinal biopsies of HC (white bars), CDA (black bars) and CDGF patients (grey bars) (c). Paired analysis was used to determine further the differences between the two isoforms’ expression within the same group of patients (d). Each dot represents the mean among the mRNA expression values ± s.e.m. Relative expression of RORγT was measured in small intestinal biopsies form HC (n = 13), CDA (n = 13) and CDGF (n = 9) (e). Positive correlation between the expression of RORγT and FOXP3 Δ2 was determined on the CDA samples for which we had both gene values (n = 13) by two‐tailed Spearman's correlation analysis (f). Relative expression of IL17A was measured in small intestinal biopsies of HC (n = 6) and CDA (n = 8) (G). Positive correlation between the expression of IL17A and FOXP3Δ2 was determined on CDA samples (n = 8) by two‐tailed Pearson correlation analysis (h). Real‐time RT–PCR data were normalized to housekeeping gene 18S. Statistical comparisons were made using the Mann–Whitney U‐test (a,b,g), unpaired t‐test (c,e) and Wilcoxon's or paired t‐test (d). *P < 0·05; **P < 0·005.

Figure 2.

Relative expression of forkhead box protein 3 (FOXP3) isoforms, retinoic acid‐related orphan receptors (RORγT) in CD4+ cells isolated from small intestinal biopsies. Real‐time reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT–PCR) was used to measure the relative expression of each FOXP3 isoform in CD4+ cells isolated from small intestinal biopsies in healthy controls (HC) (n = 5) and CDA (n = 4) patients (a). The ratio between the two isoforms (Δ2/FL) was calculated individually for each subject and compared between the two groups of patients (b). The bars show the mean of the ratios ± standard error of the mean (s.e.m.) in small intestinal biopsies of HC (white bars) and CDA (black bars). Paired analysis was used to determine further the differences between the two isoforms within the same group of patients (c). Each dot represents the mean among the mRNA expression values ± s.e.m. Relative expression of RORγT was measured in HC (n = 5) and CDA (n = 4) patients (d) and the correlation between the expression of RORγT and FOXP3 Δ2 was determined on the CDA samples by two‐tailed Spearman's correlation analysis (e). Real time RT–PCR data were normalized to housekeeping gene 18S. Statistical comparisons were made using the Mann–Whitney U‐test (a,b) and Wilcoxon's test (c). *P < 0·05.

Peripheral blood expression of FoxP3 isoforms is similar between coeliac patients and control subjects

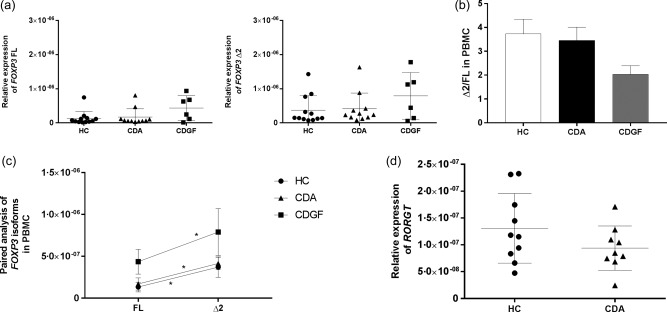

The intestinal microenvironment is unique and highly diverse. To evaluate if the differences found in biopsies of CDA patients represented an event restricted exclusively to the intestinal compartment, we measured the expression of FOXP3 isoforms and RORγT by real‐time RT–PCR on mRNA extracted from PBMC of HC subjects, CDA and CDGF patients. Our data did not show a significant difference among the three groups of patients (Fig. 3a). Interestingly, the ratios (Δ2/FL) between isoforms were similar in all groups (Fig. 3b) and the alternatively spliced isoform FOXP3 Δ2 appeared more expressed than the FL (P < 0·05) (Fig. 3c). Furthermore, data on RORγT expression did not reveal differences in the expression of the transcription factor between CDA and HC (Fig. 3d).

Figure 3.

Relative expression of forkhead box protein 3 (FOXP3) isoforms, retinoic acid‐related orphan receptors (RORγT) in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC). Real‐time reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT–PCR) was used to measure the relative expression of both FOXP3 isoforms separately (a) and RORγT (d) among healthy subjects (HC n = 12), active coeliac patients (CDA n = 11) and CD patients in remission [coeliac patients in remission following a gluten free diet (CDGF) n = 6]. The ratio between the relative expression of FOXP3 Δ2 and FL (Δ2/FL) was calculated individually for each subject and compared among the three groups of patients. The bars show the mean of the ratios ± standard error of the mean (s.e.m.) in PBMC of HC (white bars), CDA (black bars) and CDGF patients (grey bars) (b). Paired analysis was used to determine further the differences between the two isoforms’ expression within the same group of patients (c). Each dot represents the mean among the mRNA expression values ± s.e.m. Real time RT–PCR data were normalized to housekeeping gene 18S. Statistical comparisons were made using the Mann–Whitney U‐test (a,b), Wilcoxon's test (c) and unpaired t‐test (d). *P < 0·05.

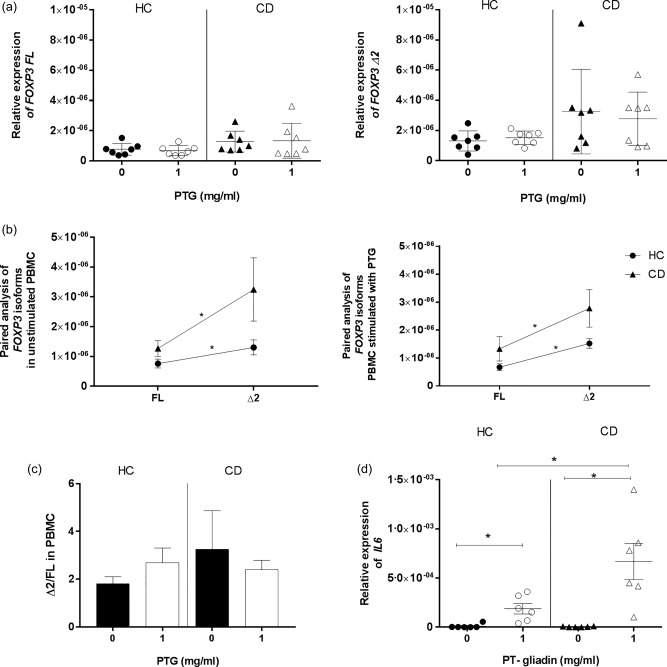

Pepsin–trypsin (PT)‐gliadin does not affect the ratio between FoxP3 isoforms expression

Gliadin is the recognized environmental trigger for CD and, to this day, the complete elimination of gluten from the diet is the only efficient treatment for CD patients. Given that gliadin peptides have been shown to interact with immune cells in the lamina propria of the small intestine during the active state of the disease, we hypothesized that they may trigger the sustained imbalance between FOXP3 isoforms in genetically predisposed individuals. This would then explain the lack of the same phenomenon when the subjects are in remission following gluten elimination from the diet. To test our hypothesis, we stimulated PBMC from HC and CD patients in remission with pepsin–trypsin gliadin digest (PTG). PTG did not trigger a higher expression of FOXP3 Δ2 in CD patients compared to HC subjects (Fig. 4a). Our paired analysis showed that in both groups of patients, even after stimulation with PTG, FOXP3 Δ2 was more expressed than FL (P < 0·05) (Fig. 4b). Furthermore, we did not see changes in FOXP3 isoforms ratio (Δ2/FL) after stimulation (Fig. 4c). Relative expression of IL6 was measured in PBMC from both groups to ensure the efficacy of the stimulation with PTG (Fig. 4d).

Figure 4.

Relative expression of forkhead box protein 3 (FOXP3) isoforms in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) stimulated with pepsin–trypsin (PT) gliadin (PTG). PBMC from healthy controls (HC) and CD patients in remission were cultured for 24 h with medium alone or with 1 mg/ml of PTG. Relative expression of FOXP3 isoforms normalized to housekeeping gene 18S expression was measured before and after stimulation in HC (n = 7) and CD (n = 7) patients (a). Paired analysis was used to determine the differences between the two isoforms’ expression within the same group of patients in both culture conditions (b). Each dot represents the mean among the mRNA expression values ± standard error of the mean (s.e.m.). The ratio between the relative expressions of FOXP3 isoforms (Δ2/FL) was calculated individually for each subject in HC and CD cultured with medium alone or stimulated with PTG. The bars show the mean of the ratios ± s.e.m. in PBMC of HC and CD patients without stimulus (black bars) or stimulated with PTG (white bars) (c). Relative expression of interleukin (IL)6 was measured as a positive control of the efficacy of the PBMC stimulation with PTG in PBMC from HC (n = 6) and CD (n = 6) (D). Statistical comparisons were made using Wilcoxon's test (a,b,d), the Mann–Whitney U‐test (b,d) and the Kruskal–Wallis test (c). *P < 0·05.

Combined effect of proinflammatory cytokine IFN‐γ plus butyrate on modulating the ratio between FoxP3 isoforms expression in PBMC.

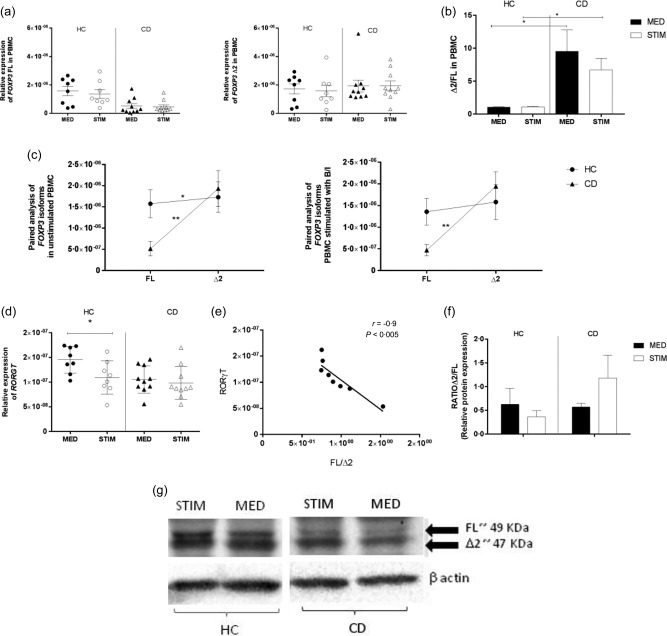

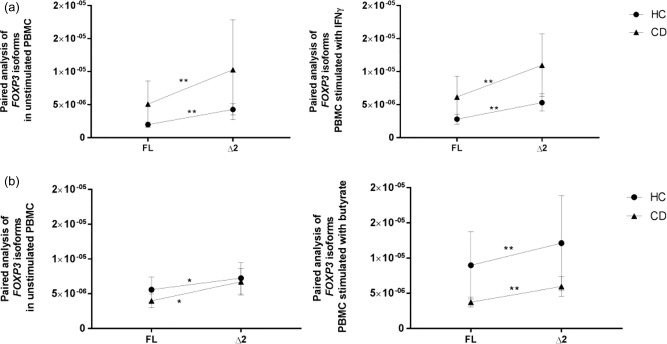

We reasoned that the imbalance between FoxP3 isoforms observed in CDA subjects may be due to the unique intestinal microenvironment of these patients. A major feature of the cascade of events that lead to enteric damage in CD is the adaptive Th1‐driven immune response and its consequent high production of the proinflammatory cytokine IFN‐γ [22]. The active state of the disease has also been associated with high levels of the microbial‐derived metabolite butyrate 35, 36. To determine the role of the intestinal microenvironment in modulating FoxP3 isoform expression, we stimulated PBMC from HC and CD patients with a combination of IFN‐γ plus butyrate. In either group of patients the relative expression of each FoxP3 isoform did not change upon stimulation (Fig. 5a). The comparison between individual ratios (Δ2/FL) showed a significant skew towards FoxP3 Δ2 in CD subjects compared to the control group (P < 0·05) (Fig. 5b). Interestingly, our paired analysis between isoforms revealed that in HC subjects the combination of butyrate and IFN‐γ appeared to trigger a balance between the two FoxP3 isoforms, which showed similar expression levels (Fig. 5c). Conversely, PBMC from CD patients maintained the imbalanced ratio between isoforms (P < 0·005) after stimulation when compared to non‐stimulated cells. The acquired balance between FoxP3 isoforms in HC subjects mimicked what we saw in the intestinal samples. Furthermore, it matched with a significant decrease of RORγT mRNA expression after stimulation (P < 0·05), while no differences in RORγT expression occurred in CD patients (Fig. 5d). Interestingly, we showed a negative correlation between the expression of RORγT and FL/Δ2 ratio in HC subjects (Fig. 5e). Western blot analysis confirmed the presence of the two isoforms at the protein level before and after stimulation with butyrate and IFN‐γ in both groups of subjects. The analysis by Western blot also showed that the ratio between isoforms (Δ2/FL) decreased after stimulation in HC, while it increased in CD subjects (Fig. 5f,g). Relative expression of Tbet was used as positive control to confirm the efficacy of IFN‐γ stimulation (Supporting information, Fig. S1) To confirm that the modulatory effect on FoxP3 isoforms in HC subjects was due to the combination of the proinflammatory cytokine and the microbial‐derived metabolite, we stimulated PBMC from HC and CD subjects with each molecule separately. Our paired analysis showed that neither IFN‐γ nor butyrate alone had any effect in altering the ratio between FoxP3 isoforms in HC or CD subjects (Fig. 6a,b).

Figure 5.

Relative expression of forkhead box protein 3 (FOXP3) isoforms, retinoic acid‐related orphan receptors (RORγT) in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) stimulated with interferon (IFN)‐γ and butyrate. PBMC from healthy controls (HC) (n = 8) and coeliac disease (CD) patients in remission (n = 10) were cultured for 48 hours in medium alone (MED) or stimulated with 100 ng/ml of IFN‐γ and 1 μg/ml of butyrate (STIM). Relative expression of FOXP3 and RORγT was measured by relative real‐time reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT–PCR) using specific primers for the two isoforms and normalized to housekeeping gene 18S (a,d). The ratio between the relative expressions of FOXP3 isoforms (Δ2/FL) was calculated individually for each subject in HC and CD cultured with medium alone (MED) or stimulated (STIM). The bars show the mean of the ratios ± standard error of the mean (s.e.m.) in PBMC of HC and CD patients without stimuli (black bars) or stimulated with butyrate and IFN‐γ (white bars) (b). Paired analysis was used to determine further the differences between the two isoforms’ expression within the same group of patients (c). Each dot represents the mean among the mRNA expression values ± s.e.m. Negative correlation between the expression of RORγT and the ratio FOXP3 FL/Δ2 was confirmed by two‐tailed Spearman's correlation analysis (e). Protein levels of splice variants were analysed by Western blot using isoform‐non‐specific α‐FoxP3 antibody PCH101. The ratio between FoxP3 isoforms (Δ2/FL) was calculated normalizing the relative protein expression of each isoform to β‐actin in PBMC isolated from HC (n = 3) and CD subjects (n = 3) before (MED) and after stimulation (STIM) (f). Western blot analysis of FoxP3 protein detection in PBMC cultured with medium alone (MED) or with butyrate and IFN‐γ (STIM) is representative of three independent experiments on PBMC from HC and CD patients (g). Statistical comparisons were made using Wilcoxon's test or paired t‐test. *P < 0·05; **P < 0·005.

Figure 6.

Relative expression of forkhead box protein 3 (FOXP3) isoforms in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) from non‐coeliac controls and coeliac patients stimulated with interferon (IFN)‐γ or butyrate. Paired analysis was used to determine the differences between the two isoforms’ expression within the same group of patients in PBMC from healthy controls (HC) (n = 12 for the IFN‐γ experiment and n = 19 for the butyrate experiment) and CD (n = 10 for the IFN‐γ experiment and n = 20 for the butyrate experiment) subjects were cultured for 48 h in medium alone or stimulated with either 100 ng/ml of IFN‐γ (a) or 1 μg/ml of butyrate (b). Each dot represents the mean among the mRNA expression values ± standard error of the mean (s.e.m.). Differences between the relative expression of FOXP3 isoforms within each group was determined in HC and CD in both culture conditions. Relative real‐time reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT–PCR) data were normalized to housekeeping gene 18S. Statistical comparisons were made using Wilcoxon's test or paired t‐test (a,b). *P < 0·05; **P < 0·005.

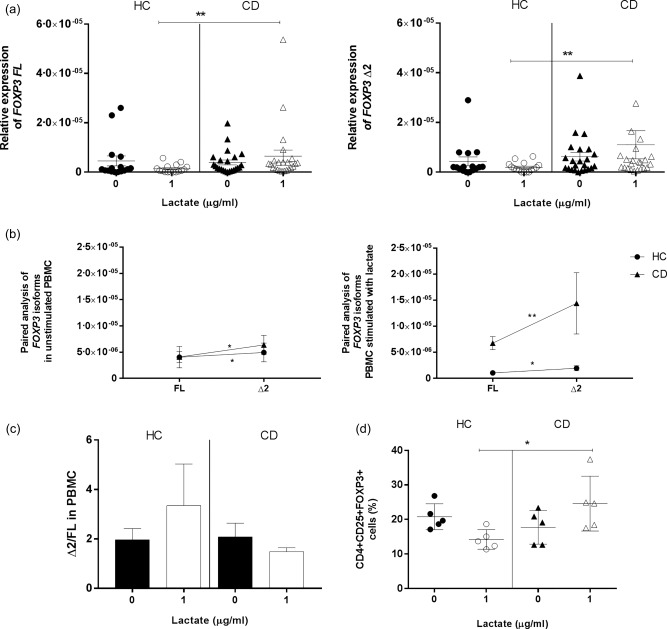

Microbial‐derived lactate modulates FoxP3 isoforms expression in PBMC

We have shown previously that high levels of lactate and Lactobacilli spp. are detected in genetically predisposed infants just prior to the onset of CD 36. We hypothesized that components characterizing the preclinical phase of the disease may prime the intestinal microenvironment of future CD patients and lead to the onset of the disease. To investigate this further, we stimulated PBMC from HC subjects and CD patients with lactate to evaluate if this metabolite may play a role in modulating FOXP3 isoforms expression. Although our analysis on HC and CD subjects did not show statistically significant changes in FOXP3 isoforms expression between the two culture conditions, upon stimulation with lactate both FOXP3 isoforms appeared to be expressed more significantly in CD patients compared to HC subjects (P < 0·005) (Fig. 7a). Additionally, in both groups of subjects FOXP3 Δ2 was expressed significantly more than its counterpart FL (P < 0·005) (Fig. 7b). The ratio between isoforms (Δ2/FL) did not appear to differ between the two groups of subjects or between culture conditions (Fig. 7c). The protein levels of FoxP3 were measured in PBMC by flow cytometry rather than by Western blot. By looking at the genic expression we observed that both isoforms were increased in CD compared to HC after stimulation with lactate, therefore we did not find it necessary to look at the protein levels of each isoform separately. We found it to be more appropriate to measure the total FoxP3 expression. Furthermore, flow cytometry allowed us to confirm that the increased expression of FoxP3 in CD was due to Treg cell population and not to other FoxP3‐expressing cells. Our flow cytometry analysis confirmed the increased expression of total FoxP3 protein in CD patients compared to HC subjects after stimulation with lactate (P < 0·05) (Fig. 7d and Supporting information, Fig. S2).

Figure 7.

Expression of forkhead box protein 3 (FOXP3) isoforms in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) upon stimulation with lactate. The effect of lactate (1 μg/ml) on FOXP3 isoforms expression was evaluated by real‐time reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT–PCR) on PBMC from non‐coeliac subjects (HC n = 16) and coeliac patients (CD n = 23) after a 48‐h stimulation and normalized on 18S (a). Paired analysis was used to determine differences between the two isoforms’ expression within each group of patients in both cultures conditions (b). Each dot represents the mean among the mRNA expression values ± standard error of the mean (s.e.m.). The ratio between the relative expressions of FOXP3 isoforms (Δ2/FL) was calculated individually for each subject in HC and CD cultured with medium alone or stimulated. The bars show the mean of the ratios ± s.e.m. in PBMC of HC and CD patients without stimuli (black bars) or stimulated with lactate (white bars) (c). Flow cytometry was used to determine the protein levels of total FoxP3 before and after stimulation in HC (n = 5) and CD (n = 5) subjects. The percentage of CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ cells was calculated within the CD4+CD25+ gate (d). Statistical comparisons were made using Wilcoxon's test (a,d) and the Mann–Whitney U‐test (b,c). *P < 0·05; **P < 0·005.

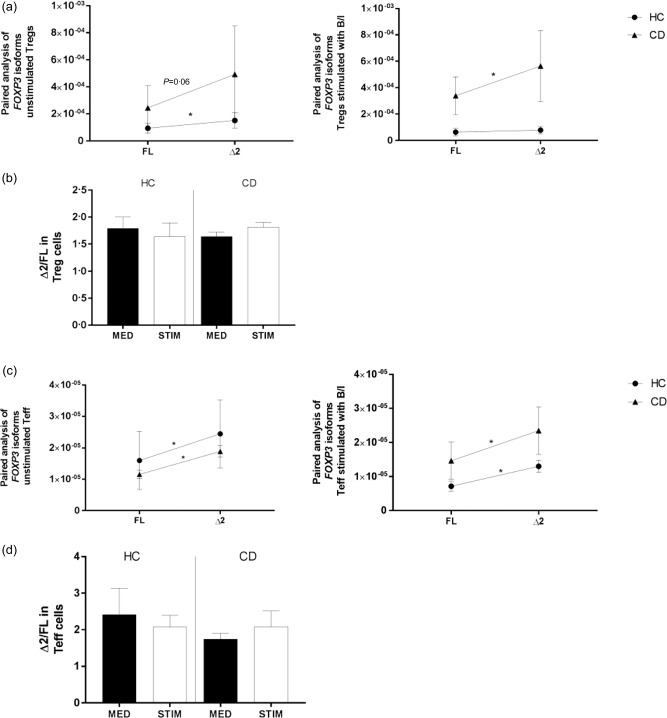

Effect of butyrate and IFN‐γ on the expression of FoxP3 isoforms in CD4+CD25+ Treg and CD4+CD25– T cells

It has been shown that, upon activation, FoxP3 expression is up‐regulated in CD4+CD25– T cells 37. This confers a transient suppressive function to this subset of cells. To evaluate more clearly the precise cells subset targeted by IFN‐γ and butyrate, we isolated CD4+CD25– T cells and CD4+CD25+ Treg from HC and CD patients (Supporting information, Fig. S3) and cultured them under the same conditions used previously for our PBMC. Real‐time RT–PCR data showed that stimulation of Treg cells with IFN‐γ and butyrate triggered a balance between FOXP3 isoforms in HC subjects, while the same did not occur in cells isolated from CD patients (Fig. 8a). However, the ratios between isoforms (Δ2/FL) did not differ between HC and CD subjects (Fig. 8b). Conversely to what we saw in the Treg cell population, our experiments on CD4+CD25– T cells showed that stimulation with IFN‐γ and butyrate did not have a modulatory effect on the FOXP3 isoforms, with FOXP3 Δ2 being expressed more sustainably than its counterpart FL (Fig. 8c), and that the ratio between isoforms (Δ2/FL) did not change between the two groups of patients (Fig. 8d).

Figure 8.

Relative expression of forkhead box protein 3 (FOXP3) isoforms in CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells (Treg) and CD4+CD25– T cells upon stimulation with butyrate and interferon (IFN)‐γ. The effect of butyrate and IFN‐γ on the ratio between FOXP3 isoform expression was evaluated by real‐time reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT–PCR) on CD4+CD25+ Treg [healthy controls (HC) n = 6, coeliac disease (CD) n = 6] and CD4+CD25– T cells (HC n = 8 and CD n = 11). CD4+CD25+ Treg (a) and CD4+CD25– T cells (c) were isolated from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC), respectively, by double‐positive and ‐negative selection and cultured for 48 h with medium alone or a combination of 1 μg/ml of butyrate and 100 ng/ml of IFN‐γ (Β/Ι). Paired analysis was used to determine differences between the two isoforms’ expression in both groups of patients and culture conditions (unstimulated or stimulated with B/I), respectively, in CD4+CD25+ Treg (a) and CD4+CD25– T cells (c). Each dot represents the mean among the mRNA expression values ± standard error of the mean (s.e.m.). The ratio between the relative expressions of FOXP3 isoforms (Δ2/FL) was calculated individually for each subject in HC and CD cultured with medium alone or stimulated. The bars show the mean of the ratios ± s.e.m. different T subsets of HC and CD patients without stimuli (black bars) or stimulated with butyrate and IFN‐γ (white bars) (b,d). The relative expression of FOXP3 isoforms was normalized on 18S. Statistical comparisons were made using Wilcoxon's test and paired t‐test (a,c) and the Mann–Whitney U‐test (b,d). *P < 0·05; **P < 0·005.

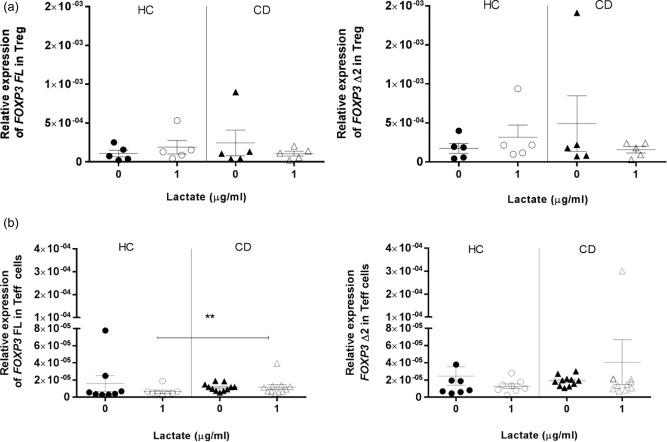

Effect of lactate on FoxP3 isoforms expression on CD4+CD25+ and CD4+CD25– T cells

To determine if lactate triggers the increased expression of both FoxP3 isoforms by targeting Treg or T effector cells directly, we isolated CD4+CD25– T cells and CD4+CD25+ Treg from HC and CD patients and cultured them with or without lactate. Our data showed that stimulation of Treg cells with lactate did not trigger any increase in FOXP3 isoforms expression in CD patients compared to HC subjects, nor were there differences between the two cultures conditions (Fig. 9a), therefore refuting the hypothesis that this microbial‐derived metabolite targets Treg cells directly. Interestingly, the stimulation of CD4+CD25– T cells led to a higher expression of FOXP3 FL (P < 0·05) in CD patients compared to HC subjects, but not of FOXP3 Δ2 (Fig. 9b).

Figure 9.

Relative expression of forkhead box protein 3 (FOXP3) isoforms in CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells (Treg) and CD4+CD25– T cells upon stimulation with lactate. The effect of lactate on the relative expression of both FOXP3 isoforms was evaluated by real‐time reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT–PCR) in CD4+CD25+ Treg [healthy controls (HC) n = 6, coeliac disease (CD) n = 6] and CD4+CD25– T cells (HC n = 8 and CD n = 11). CD4+CD25+ Treg (a) and CD4+CD25– T cells (b) were isolated from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC), respectively, by double‐positive and ‐negative selection and cultured for 48 h with medium alone or with 1 μg/ml of lactate. The relative expression of FOXP3 isoforms was normalized on 18S. Statistical comparisons were made using Wilcoxon's test (a) and the Mann–Whitney U‐test (b). *P < 0·05; **P < 0·005.

Discussion

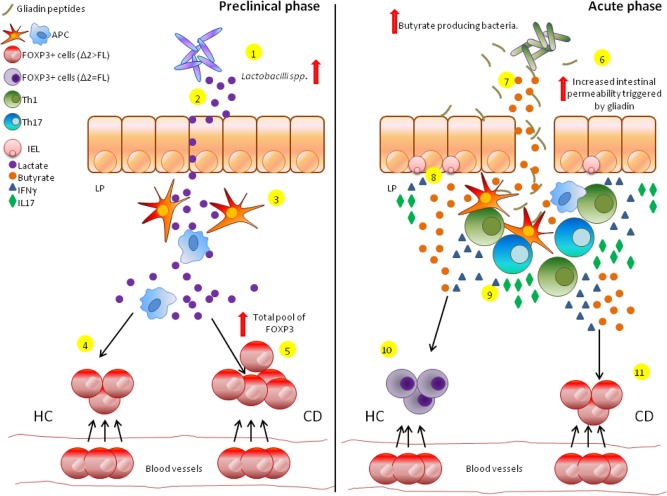

FoxP3 is a transcription factor fundamental for the suppressive function and differentiation of Treg cells. In this study we report a higher expression of the alternatively spliced isoform FOXP3 Δ2 in the intestine of CDA patients compared to non‐coeliac controls, while no differences were seen in the expression of FOXP3 FL. Conversely to what was previously reported in the literature 33, our data on CDGF showed a higher expression of both FOXP3 isoforms in this group of patients. Interestingly, however, we found that in CDA patients the relative amount of FOXP3 Δ2 in the gut mucosa was higher than the FL, while HC subjects and CDGF patients presented a similar expression of both isoforms. These findings underscore the importance that the altered intestinal ratio between FoxP3 isoforms may have on the pathogenesis of CD. The spliced isoform FoxP3 Δ2 has been described as less efficient in down‐regulating RORγT/αT expression compared to its counterpart FL 17. Our data demonstrated that the over‐expression of FOXP3 Δ2 matched with higher mRNA levels of RORγT. Furthermore, we also found a positive correlation between the expression of FOXP3Δ2, RORγT and IL17A. Taken together, these findings confirmed the deficiency of the Δ2 isoform in down‐regulating the Th17 master transcription factor. Previous studies have reported an increase in the number of Treg cells in CD patients and suggested that functional impairments in their suppressive function may be related to the onset of the disease 29, 30, 31, 32. The exact mechanisms that cause the altered regulatory activity of Treg cells in CD, however, are not understood fully. As the active state of the disease has been associated with a proinflammatory Th17‐driven response 25, 26, we infer from our data that the imbalance between FOXP3 isoforms may play a role in triggering and activating this Th17 response in a subgroup of CD patients. Our data from PBMC isolated from whole blood suggest a contribution of the intestinal microenvironment in modulating the ratio between FoxP3 isoforms. The intestinal lamina propria is considered one of the largest interfaces between the host and its external surroundings. T cells are particularly susceptible to different stimuli such as cytokines that have been shown to play a fundamental role in shaping the outcome of the immune response 38. Additionally, the microbiome has been described to interact directly with immune cells to either promote or down‐regulate inflammatory processes 39, and several studies have reported an association between CD and intestinal dysbiosis 40, 41, 42. We have shown that the combination of proinflammatory cytokine IFN‐γ plus microbial‐derived butyrate creates a gut micromilieu that, by epigenetic pressure, establishes equilibrium between the two isoforms in HC subjects, while the same balance is not reached in PBMC from CD patients. Interestingly, the same effect was not seen when the PBMC were stimulated with only one of the two molecules, therefore underscoring a synergistic action of IFN‐γ with the microbial‐derived metabolite. Our studies on different subsets of T cells (namely CD4+CD25– T effector cells and CD4+CD25++ Treg cells) confirmed that the short chain fatty acid and the proinflammatory cytokine target Treg cells directly. In line with our findings that a specific gut microenvironment during gut homing may influence the alternative splicing machinery, Mailer et al. showed that patients affected by Crohn's disease display an increased expression of the less common FoxP3 isoform lacking exon 7 and that proinflammatory cytokine IL‐1β induced the alternative splicing 43. The importance of butyrate in the regulation of the immune system is well described. This short chain fatty acid has been shown to induce FoxP3 expression and Treg cell differentiation in the colonic lamina propria and to promote FOXP3 promoter acetylation 44, 45, 46. Based on our data, we hypothesize that the balance between FOXP3 isoforms in HC subjects after stimulation with IFN‐γ and butyrate may represent a compensatory mechanism of Treg cells in becoming more efficient at responding to mucosal inflammation. The sustained imbalance between the two isoforms that we reported in CD patients may account, instead, for the lack of proper anti‐inflammatory response and the subsequent chronic mucosal inflammatory process that characterizes the active state of the disease despite the high number of Treg cells. These findings emphasize the hypothesis that innate defects in Treg cell population can lead to a different response to the same microenvironment and eventually trigger an inefficient immune regulation. Additional studies are warranted to understand more clearly the mechanisms by which IFN‐γ and butyrate synergize to restore equilibrium between FOXP3 isoforms in HC subjects and how, conversely, this does not occur in CD patients. The human gastrointestinal microbiota is composed of 1014 microbes, whose main functions are limiting the growth of potential pathogenic microorganisms, regulating gastrointestinal development and contributing to the breakdown of dietary products 47, 48. The intestinal immune system is known to play an important role in establishing the tolerogenic environment to commensal bacteria 49, and the microbiome itself is fundamental in shaping the immune system 50, 51. We have previously reported the proof of concept that infants genetically predisposed to CD are characterized by increased production of lactate associated with enrichment in Lactobacilli spp. in the preclinical phase, followed by a sharp drop of both just before the onset of the disease. The same metabolomic profile was not detected in children who did not develop CD 36. In the present study we have shown that, upon stimulation with lactate, PBMC from CD patients expressed higher levels of both FOXP3 isoforms compared to non‐coeliac HC subjects, therefore confirming once again how cells from CD patients respond differently to the same microenvironment. As Lactobacilli spp. have been shown to enhance the integrity of the intestinal barrier and to shape the immune system in a protective manner 52, 53, it is conceivable to hypothesize that the increased FOXP3 expression in response to lactate may represent a preclinical compensatory mechanism in CD at‐risk patients to down‐regulate the inflammation. The following drop then may contribute to the definitive loss of gluten tolerance and the subsequent onset of disease. This theory is supported by the evidence that longitudinal studies of infants at‐risk for CD have shown that, in the preclinical phase, the onset of the autoimmune process as shown by the appearance of anti‐tissue transglutaminase autoantibodies is dynamic and reversible, with 50–80% of subjects showing normalization of the autoantibody titres without any dietary intervention 54, 55. Our experiments on T effector and Treg cells, however, suggest that this microbial‐derived metabolite does not modulate FOXP3 expression directly, but probably exerts its effect through other cells such as APC. In line with our findings, Goodman et al. reported that the probiotic Lactobacillus family contains suppressive motifs that interact with APC signals 39. Furthermore, L. crispatus has been shown to be able to induce human dendritic cell proliferation and to confer to them an anti‐inflammatory phenotype 56. Further studies are needed to understand more clearly the role of lactate in the preclinical phase of the disease and how this may affect the suppressive function of Treg cells. Collectively from these findings, we hypothesize the following sequence of events (Fig. 10): while circulating in the blood, Treg cells are characterized by an over‐expression of less functional FoxP3 Δ2 over functional FL. Once recruited to the intestinal compartment, the specific microenvironment of HC or CD subjects modulates differentially the expression of both isoforms. The high production of lactate that characterizes the preclinical state of CD triggers an increased expression of FoxP3 in CD patients compared to HC, while the ratio between the isoforms is maintained imbalanced. This microbial‐derived metabolite, however, does not target Treg cells directly, but probably acts on APC. During the active state of the disease, the intestine is characterized by increased intestinal permeability and a proinflammatory IFN‐γ enriched microenvironment related to microbiota dysbiosis (as mimicked by excessive butyrate production). These conditions trigger an efficient regulatory immune response in HC subjects by modulating directly the balance between FoxP3 isoforms, while intrinsic defects on Treg cells do not allow this balance to occur in CD patients.

Figure 10.

Proposed sequence of events contributing to the development of coeliac disease (CD). Increased production of lactate associated with enrichment in Lactobacilli spp. has been shown to characterize the preclinical phase of individuals predisposed genetically to CD (1,2). The interaction between this microbial‐derived metabolite and antigen‐presenting cells (APC) triggers a regulatory phenotype on the cells (3) that, in a healthy subject (HC), will lead to the intestinal homing of forkhead box protein 3 (FoxP3+) cells (4). CD patients, however, seem to be more responsive to lactate and show an increase in the total pool of FoxP3+ cells compared to HC as a possible compensatory mechanism to maintain a high level of functional FoxP3+ FL isoform (5). During the active state of the disease the small intestine of CD patients is characterized by a drop in lactate levels, an increased intestinal permeability due to the interaction between gliadin and epithelial cells (6) and high production of butyrate from the microbial flora (7). Furthermore, expanded intraepithelial lymphocytes (IELs) produce a high amount of proinflammatory cytokines such as interferon (IFN)‐γ and interleukin (IL)‐17 (8). The increased intestinal permeability allows gliadin peptides to translocate to the lamina propria of the small intestine, where they are recognized by APC (9). This triggers an adaptive immune response that is T helper type 1 (Th1)/Th17‐driven and characterized by high production of proinflammatory IL‐17 and IFN‐γ. In HC subjects the local micro‐milieu characterized by this proinflammatory environment and microbiome‐derived excess butyrate causes the FoxP3 epigenetic switch toward the more functional (and, therefore, more protective) FL isoform restoring the equilibrium between FoxP3 isoforms (10). Conversely, in CD patients Treg cells are not capable of undergoing this epigenetic modification and persistently over‐express FoxP3 Δ2 (less functional) over FL, leading to chronic inflammation and, eventually, autoimmune enteropathy (11). [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

In summary, our study demonstrates for the first time a direct and mechanistic link between microbiota‐derived metabolites, mucosal inflammatory processes and epigenetic changes regulating FOXP3 isoform expression and how these mechanisms lead towards a Th17‐driven immune response in CD subjects. Our data highlight the multi‐factorial nature of CD and provide a set of new possible targets for the prevention of CD in genetically susceptible individuals.

Disclosure

None.

Supporting information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article at the publisher's web‐site.

Fig. S1. Relative expression of TBET in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) upon stimulation with butyrate and interferon (IFN)‐γ. Relative expression of TBET was measured as a positive control of the efficacy of PBMC stimulation with IFN‐γ and butyrate. PBMC (n = 11) were cultured for 48 h in complete medium alone (MED) or stimulated with 100 ng/ml of IFN‐γ and 1 μg/ml of butyrate (STIM). Relative expression of TBET was normalized on housekeeping gene 18S. Statistical comparisons were made using Wilcoxon's test. **P < 0·005.

Fig. S2. Flow cytometry analysis of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) upon stimulation with lactate. Each scatter dot‐plot shows the percentage of forkhead box protein 3 (FoxP3+) cells within the CD4+CD25+ gate. Scatter dot‐plots are representative of five experiments for each group of subjects. Data 001 [coeliac disease (CD)] and Data 011 [healthy controls (HC)] represents PBMC without stimulation, while Data 002 (CD) and Data 012 (HC) represent PBMC after stimulation with lactate.

Fig. S3. Flow cytometry analysis of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells (Treg) and CD4+CD25– T cells at baseline. The purity of isolated CD4+CD25+ Treg cells (a) and CD4+CD25– T cells (b) was determined higher than 90% by flow cytometry. Cells were stained with antibodies peridinin chlorophyll (PerCP)‐conjugated anti‐CD4 and phycoerythrin (PE) conjugated anti‐CD25. Detection of CD4+CD25++ and CD4+CD25– was performed with BD Bioscience software. Scatter dot‐plots are representative of two separate experiments for Treg cells (a) and three separate experiments for CD4+CD25– T cells (b).

Acknowledgements

G. S. designed and performed the experiments, analysed the data and wrote the manuscript; S. Y. helped in performing experiments and performed the serology of all samples; S. C., S. P., R. S. M., A. S., M. M. L. and R. M. provided clinical samples; K. M. L. helped in designing experiments, A. F. developed the overall hypothesis and supervised the research. All authors reviewed the manuscript critically. This work was supported partially by The National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants DK048373 and DK104344 to A. F.

References

- 1. Asseman C, von Herrath M. About CD4pos CD25pos regulatory cells. Autoimmun Rev 2002; 1:190–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Piccirillo CA, Shevach EM. Naturally‐occurring CD4+CD25+ immunoregulatory T cells: central players in the arena of peripheral tolerance. Semin Immunol 2004; 16:81–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Schmidt A, Oberle N, Krammer PH. Molecular mechanisms of Treg‐mediated T cell suppression. Front Immunol 2012; 3:51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ohkura N, Kitagawa Y, Sakaguchi S. Development and maintenance of regulatory T cells. Immunity 2013; 38:414–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Devaud C, Darcy PK, Kershaw MH. Foxp3 expression in T regulatory cells and other cell lineages. Cancer Immunol Immunother 2014; 63:869–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lopes JE, Torgerson TR, Schubert LA et al Analysis of FOXP3 reveals multiple domains required for its function as a transcriptional repressor. J Immunol 2006; 177:3133–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bennett CL, Christie J, Ramsdell F et al The immune dysregulation, polyendocrinopathy, enteropathy, X‐linked syndrome (IPEX) is caused by mutations of FOXP3. Nat Genet 2001; 27:20–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Owen CJ, Eden JA, Jennings CE, Wilson V, Cheetham TD, Pearce SH. Genetic association studies of the FOXP3 gene in Graves’ disease and autoimmune Addison's disease in the United Kingdom population. J Mol Endocrinol 2006; 37:97–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lin YC, Lee JH, Wu AS et al Association of single‐nucleotide polymorphisms in FOXP3 gene with systemic lupus erythematosus susceptibility: a case–control study. Lupus 2011; 20:137–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sanchez E, Rueda B, Orozco G et al Analysis of a GT microsatellite in the promoter of the foxp3/scurfin gene in autoimmune diseases. Hum Immunol 2005; 66:869–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Deng G, Xiao Y, Zhou Z et al Molecular and biological role of the FOXP3 N‐terminal domain in immune regulation by T regulatory/suppressor cells. Exp Mol Pathol 2012; 93:334–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Zhang F, Meng G, Strober W. Interactions among the transcription factors Runx1, RORgammat and Foxp3 regulate the differentiation of interleukin 17‐producing T cells. Nat Immunol 2008; 9:1297–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hu H, Djuretic I, Sundrud MS, Rao A. Transcriptional partners in regulatory T cells: Foxp3, Runx and NFAT. Trends Immunol 2007; 28:329–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lee SM, Gao B, Fang D. FoxP3 maintains Treg unresponsiveness by selectively inhibiting the promoter DNA‐binding activity of AP‐1. Blood 2008; 111:3599–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zhou L, Lopes JE, Chong MM et al TGF‐beta‐induced Foxp3 inhibits T(H)17 cell differentiation by antagonizing RORgammat function. Nature 2008; 453:236–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zhou Z, Song X, Li B, Greene MI. FOXP3 and its partners: structural and biochemical insights into the regulation of FOXP3 activity. Immunol Res 2008; 42:19–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Du J, Huang C, Zhou B, Ziegler SF. Isoform‐specific inhibition of ROR alpha‐mediated transcriptional activation by human FOXP3. J Immunol 2008; 180:4785–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Allan SE, Passerini L, Bacchetta R et al The role of 2 FOXP3 isoforms in the generation of human CD4+ Tregs. J Clin Invest 2005; 115:3276–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mailer RK, Falk K, Rotzschke O. Absence of leucine zipper in the natural FOXP3Delta2Delta7 isoform does not affect dimerization but abrogates suppressive capacity. PLOS ONE 2009; 4:e6104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Meresse B, Ripoche J, Heyman M, Cerf‐Bensussan N. Celiac disease: from oral tolerance to intestinal inflammation, autoimmunity and lymphomagenesis. Mucosal Immunol 2009; 2:8–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Fasano A, Catassi C. Clinical practice. Celiac disease. N Engl J Med 2012; 367:2419–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Garrote JA, Gomez‐Gonzalez E, Bernardo D, Arranz E, Chirdo F. Celiac disease pathogenesis: the proinflammatory cytokine network. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2008; 47: S27–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Castellanos‐Rubio A, Santin I, Irastorza I, Castano L, Carlos Vitoria J, Ramon Bilbao J. TH17 (and TH1) signatures of intestinal biopsies of CD patients in response to gliadin. Autoimmunity 2009; 42:69–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Forsberg G, Hernell O, Melgar S, Israelsson A, Hammarstrom S, Hammarstrom ML. Paradoxical coexpression of proinflammatory and down‐regulatory cytokines in intestinal T cells in childhood celiac disease. Gastroenterology 2002; 123:667–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sapone A, Lammers KM, Mazzarella G et al Differential mucosal IL‐17 expression in two gliadin‐induced disorders: gluten sensitivity and the autoimmune enteropathy celiac disease. Int Arch Allergy Immunol 2010; 152:75–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Eiro N, Gonzalez‐Reyes S, Gonzalez L et al Duodenal expression of Toll‐like receptors and interleukins are increased in both children and adult celiac patients. Dig Dis Sci 2012; 57:2278–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Monteleone I, Sarra M, Del Vecchio Blanco G et al Characterization of IL‐17A‐producing cells in celiac disease mucosa. J Immunol 2010; 184:2211–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lyssuk EY, Torgashina AV, Soloviev SK, Nassonov EL, Bykovskaia SN. Reduced number and function of CD4+CD25highFoxP3+ regulatory T cells in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Adv Exp Med Biol 2007; 601:113–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Tiittanen M, Westerholm‐Ormio M, Verkasalo M, Savilahti E, Vaarala O. Infiltration of forkhead box P3‐expressing cells in small intestinal mucosa in coeliac disease but not in type 1 diabetes. Clin Exp Immunol 2008; 152:498–507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Vorobjova T, Uibo O, Heilman K et al Increased FOXP3 expression in small‐bowel mucosa of children with coeliac disease and type I diabetes mellitus. Scand J Gastroenterol 2009; 44:422–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Granzotto M, dal Bo S, Quaglia S et al Regulatory T‐cell function is impaired in celiac disease. Dig Dis Sci 2009; 54:1513–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Cianci R, Pagliari D, Landolfi R et al New insights on the role of T cells in the pathogenesis of celiac disease. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents 2012; 26:171–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hmida NB, Ben Ahmed M, Moussa A et al Impaired control of effector T cells by regulatory T cells: a clue to loss of oral tolerance and autoimmunity in celiac disease? Am J Gastroenterol 2012; 107:604–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lammers KM, Lu R, Brownley J et al Gliadin induces an increase in intestinal permeability and zonulin release by binding to the chemokine receptor CXCR3. Gastroenterology 2008; 135:194–204 e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tjellstrom B, Hogberg L, Stenhammar L, Falth‐Magnusson K, Magnusson KE, Norin E, Sundqvist T, Midtvedt T. Faecal short‐chain fatty acid pattern in childhood coeliac disease is normalised after more than one year's gluten‐free diet. Microb Ecol Health Dis 2013; 24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sellitto M, Bai G, Serena G et al Proof of concept of microbiome‐metabolome analysis and delayed gluten exposure on celiac disease autoimmunity in genetically at‐risk infants. PLOS ONE 2012; 7:e33387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Amarnath S, Dong L, Li J, Wu Y, Chen W. Endogenous TGF‐beta activation by reactive oxygen species is key to Foxp3 induction in TCR‐stimulated and HIV‐1‐infected human CD4+CD25– T cells. Retrovirology 2007; 4:57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Schmitt N, Ueno H. Regulation of human helper T cell subset differentiation by cytokines. Curr Opin Immunol 2015; 34:130–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Goodman WA, Pizarro TT. Regulatory cell populations in the intestinal mucosa. Curr Opin Gastroenterol 2013; 29:614–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wacklin P, Kaukinen K, Tuovinen E et al The duodenal microbiota composition of adult celiac disease patients is associated with the clinical manifestation of the disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2013; 19:934–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Sanchez E, Donat E, Ribes‐Koninckx C, Fernandez‐Murga ML, Sanz Y. Duodenal–mucosal bacteria associated with celiac disease in children. Appl Environ Microbiol 2013; 79:5472–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Cheng J, Kalliomaki M, Heilig HG et al Duodenal microbiota composition and mucosal homeostasis in pediatric celiac disease. BMC Gastroenterol 2013; 13:113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Mailer RK, Joly AL, Liu S, Elias S, Tegner J, Andersson J. IL‐1beta promotes Th17 differentiation by inducing alternative splicing of FOXP3. Sci Rep 2015; 5:14674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Furusawa Y, Obata Y, Fukuda S et al Commensal microbe‐derived butyrate induces the differentiation of colonic regulatory T cells. Nature 2013; 504:446–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Vinolo MA, Rodrigues HG, Nachbar RT, Curi R. Regulation of inflammation by short chain fatty acids. Nutrients 2011; 3:858–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Fontenelle B, Gilbert KM. n‐Butyrate anergized effector CD4+ T cells independent of regulatory T cell generation or activity. Scand J Immunol 2012; 76:457–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Sekirov I, Russell SL, Antunes LC, Finlay BB. Gut microbiota in health and disease. Physiol Rev 2010; 90:859–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kelly D, Mulder IE. Microbiome and immunological interactions. Nutr Rev 2012; 70 Suppl 1:S18–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Mowat AM, Agace WW. Regional specialization within the intestinal immune system. Nat Rev Immunol 2014; 14:667–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Chai JN, Zhou YW, Hsieh CS. T cells and intestinal commensal bacteria–ignorance, rejection, and acceptance. FEBS Lett 2014; 588:4167–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Kopitar AN, Ihan Hren N, Ihan A. Commensal oral bacteria antigens prime human dendritic cells to induce Th1, Th2 or Treg differentiation. Oral Microbiol Immunol 2006; 21:1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Jounai K, Ikado K, Sugimura T, Ano Y, Braun J, Fujiwara D. Spherical lactic acid bacteria activate plasmacytoid dendritic cells immunomodulatory function via TLR9‐dependent crosstalk with myeloid dendritic cells. PLoS One 2012; 7:e32588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Takata K, Kinoshita M, Okuno T et al The lactic acid bacterium Pediococcus acidilactici suppresses autoimmune encephalomyelitis by inducing IL‐10‐producing regulatory T cells. PLoS One 2011; 6:e27644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Simell S, Kupila A, Hoppu S et al Natural history of transglutaminase autoantibodies and mucosal changes in children carrying HLA‐conferred celiac disease susceptibility. Scand J Gastroenterol 2005; 40:1182–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Lionetti E, Castellaneta S, Pulvirenti A et al Prevalence and natural history of potential celiac disease in at‐family‐risk infants prospectively investigated from birth. J Pediatr 2012; 161:908–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Eslami S, Hadjati J, Motevaseli E, Mirzaei R, Farashi Bonab S, Ansaripour B, Khoramizadeh MR. Lactobacillus crispatus strain SJ‐3C‐US induces human dendritic cells (DCs) maturation and confers an anti‐inflammatory phenotype to DCs. APMIS 2016; 124:697–710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article at the publisher's web‐site.

Fig. S1. Relative expression of TBET in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) upon stimulation with butyrate and interferon (IFN)‐γ. Relative expression of TBET was measured as a positive control of the efficacy of PBMC stimulation with IFN‐γ and butyrate. PBMC (n = 11) were cultured for 48 h in complete medium alone (MED) or stimulated with 100 ng/ml of IFN‐γ and 1 μg/ml of butyrate (STIM). Relative expression of TBET was normalized on housekeeping gene 18S. Statistical comparisons were made using Wilcoxon's test. **P < 0·005.

Fig. S2. Flow cytometry analysis of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) upon stimulation with lactate. Each scatter dot‐plot shows the percentage of forkhead box protein 3 (FoxP3+) cells within the CD4+CD25+ gate. Scatter dot‐plots are representative of five experiments for each group of subjects. Data 001 [coeliac disease (CD)] and Data 011 [healthy controls (HC)] represents PBMC without stimulation, while Data 002 (CD) and Data 012 (HC) represent PBMC after stimulation with lactate.

Fig. S3. Flow cytometry analysis of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells (Treg) and CD4+CD25– T cells at baseline. The purity of isolated CD4+CD25+ Treg cells (a) and CD4+CD25– T cells (b) was determined higher than 90% by flow cytometry. Cells were stained with antibodies peridinin chlorophyll (PerCP)‐conjugated anti‐CD4 and phycoerythrin (PE) conjugated anti‐CD25. Detection of CD4+CD25++ and CD4+CD25– was performed with BD Bioscience software. Scatter dot‐plots are representative of two separate experiments for Treg cells (a) and three separate experiments for CD4+CD25– T cells (b).