Summary

Nucleotide‐binding oligomerization domain (NOD) ‐like receptors (NLRs) are a family of 23 receptors known as pattern recognition receptors; they are expressed in many cell types and play a key role in the innate immune response. The NLRs are activated by pathogen‐associated molecular patterns, which include structurally conserved molecules present on the surfaces of bacteria. The activation of these NLRs by pathogens results in the downstream activation of signalling kinases and transcription factors, culminating in the transcription of genes coding for pro‐inflammatory factors. Expression of NLR is altered in many cellular, physiological and disease states. There is a lack of understanding of the mechanisms by which NLR expression is regulated, particularly in chronic inflammatory states. Genetic polymorphisms and protein interactions are included in such mechanisms. This review seeks to examine the current knowledge regarding the regulation of this family of receptors and their signalling pathways as well as how their expression changes in disease states with particular focus on NOD1 and NOD2 in inflammatory bowel diseases among others.

Keywords: NOD1, NOD2, inflammation, NLR expression, inflammatory bowel disease

NOD‐like receptors

The innate immune response is the body's first line of defence against challenges posed by pathogens and endogenous stress. This rapid and non‐specific response relies on recognition by a family of receptors, referred to as pathogen recognition receptors.1 Nucleotide‐binding oligomerization domain (NOD)‐like receptors (NLRs) are a family of intracellular pathogen recognition receptors that have the ability to respond to invading pathogens in addition to stress signals generated within the cell.2, 3 The 23 NLR family members have a similar tripartite structure consisting of a C‐terminal leucine‐rich repeat (LRR) domain, a central nucleotide‐binding domain (NACHT domain), and a variable N‐terminal domain. The NLR family are most commonly classified according to their N‐terminal domain, falling into one of four subfamilies; NLRA, NLRB, NLRC and NLRP. These subfamilies contain either an acidic transactivation domain, baculovirus inhibitor repeat, caspase recruitment domain (CARD) or pyrin domain, respectively.4 NOD1 (CARD4) and NOD2 (CARD15) receptors, which are both NLRC proteins, were the first of the NLRs to be identified and so are the most extensively studied members of the family5, 6 and will be the main focus of this review.

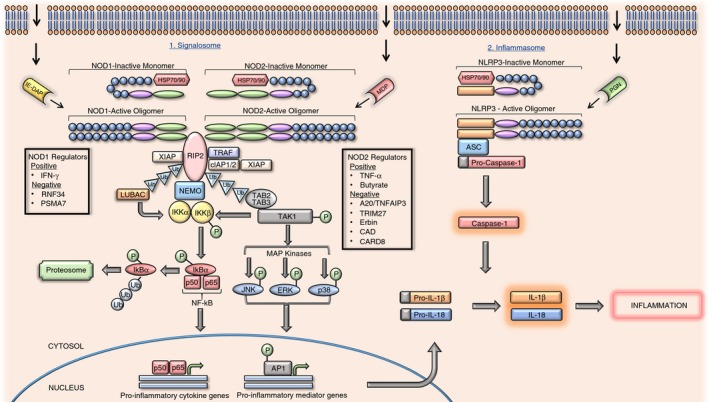

The LRR domain acts as a sensor of a minimal recognition motif from either the invading pathogens peptidoglycan (PGN) cell wall, referred to as pathogen‐associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), or endogenous stress signals, known as danger‐associated molecular patterns (DAMPs). Upon sensing the insult, NLRs homo‐oligomerize and act as a signalling platform for the assembly of adaptor and effector molecules.7 The variable N‐terminal content dictates whether the receptor will respond to the PAMP/DAMP by instigating ‘signalosome’ or ‘inflammasome’ assembly.8, 9 Signalosome activity gives rise to immature pro‐inflammatory cytokine production, whereas inflammasome assembly activates caspase‐1 and processes the immature pro‐inflammatory cytokines generated by signalosome activity (Fig. 1). Although members react differently upon stimulation, they display cooperation in the immune response.

Figure 1.

Nucleotide‐binding oligomerization domain (NOD)‐like receptor (NLR) pro‐inflammatory signalling pathway. The biochemical pathways shown in this figure pertain to NOD1 and NOD2 receptors that have been activated by γ‐d‐glutamyl‐mesodiaminopimelic acid or muramyl dipeptide.

NOD1 receptors are expressed ubiquitously, whereas NOD2 receptors are found mostly in macrophages, monocytes, Paneth intestinal cells and dendritic cells.10 The specific ligands for NOD1 and NOD2 receptors are from N‐acetylmuramic acid residues, which partially make up the PGN carbohydrate backbone.11 NOD1 receptors recognize γ‐d‐glutamyl‐mesodiaminopimelic acid (iE‐DAP), found in some Gram‐positive bacteria, including Bacillus and Listeria, and all Gram‐negative bacteria.12, 13 The NOD2 receptors sense muramyl dipeptide (MDP), a conserved motif in all Gram‐positive and Gram‐negative bacteria, making NOD2 a more general sensor of bacterial invasion.14, 15

Recent studies have proposed that host cells initially recognize polymeric PGN, responding by internalizing the polymers and subsequently trafficking them to the lysosome. The polymer is then degraded into monomeric motifs, which are released into the cytoplasm where they encounter and stimulate NLRs.16, 17 The main PGN internalization method used by invasive bacteria is phagocytosis, whereby bacteria become encapsulated in phagosomes allowing them to traverse the cell membrane. Internalized capsules then release their contents into the surrounding cytosol through type III and IV secretion systems.11 Discovery of additional internalization mechanisms including outer membrane vesicle formation, endocytosis, bacterial secretion systems, oligopeptide transporters and gap junction transport, have broadened the range of bacteria that we must consider regarding NLR stimulation.18, 19, 20, 21, 22

In the absence of pathogenic ligands, NLRs are kept in an inactive monomeric state by auto‐inhibitory molecular interactions, whereby the LRR domain of the NLR binds back on its NACHT domain, hindering oligomerization.6 Inactive NLRs are further stabilized by chaperone proteins. By forming complexes with chaperones such as heat‐shock proteins, e.g. hsp 70 or hsp 90, NLRs are able to correctly assemble, avoiding premature degradation.23, 24, 25 These complexes are thought to contribute to bacterial tolerance, preventing an excessive inflammatory response in regions such as the intestine, where trillions of bacteria reside.24 Upon recognition and binding of the appropriate PAMP, a conformational change occurs in these monomeric receptors, allowing the NLRs to homo‐oligomerize and become activated via their NACHT domains.2, 26 Active receptors can transduce the bacterial signal via a ubiquitylation/phosphorylation cascade (Fig. 1), beginning with the recruitment and activation of the serine‐threonine kinase; receptor‐interacting protein 2 (RIP2) kinase.27 Three E3 ubiquitin ligases conjugate to RIP2 kinase and subsequently polyubiquitinate the kinase at K63, thereby assisting the binding and activation of the transforming growth factor β‐activated kinase 1 (TAK1)–TAK1 binding protein 2 (TAB 2)–TAK1 binding protein 3 (TAB 3) complex.28 The TAK1 kinase becomes highly active when associated with its complex components. Active TAK1 subsequently recruits the IKK complex for activation. This complex consists of two kinases; inhibitor of κB kinase α (IKKα), and inhibitor of κB kinase β (IKKβ)29 alongside a regulatory subunit; inhibitor of κB kinase γ (IKKγ), otherwise known as nuclear factor‐κB (NF‐κB) essential modifier (NEMO).30 Phosphorylation of IKKβ renders it active so that it can phosphorylate the NF‐κB inhibitor; inhibitor of κBα (IκBα). Due to its newly acquired phosphorylated status, IκBα can be polyubiquitinated at K48 causing it to dissociate from the NF‐κB transcription factor heterodimer (p50–p65). The released inhibitor then travels to the proteasome for proteolytic degradation.28 The liberated p50–p60 heterodimer, otherwise referred to simply as NF‐κB, translocates to the nucleus where it promotes pro‐inflammatory cytokine expression.11, 31 Phosphorylated TAK1 kinase also phosphorylates the mitogen‐activating protein kinases; c‐jun N‐terminal kinase (JNK), p38 and extracellular signal‐regulated kinase (ERK), which are upstream promoters of the activator protein‐1 (AP1) transcription factor. Activated activator protein‐1 subsequently translocates to the nucleus in the same manner as NF‐κB, where it promotes the expression of pro‐inflammatory mediators.11, 32 Activation of other NLRs, such as NLRP3, by PGN components initiates inflammasome assembly. Active NLRP3 oligomers recruit apoptosis‐associated speck‐like protein containing CARD (ASC) and pro‐caspase‐1, with subsequent maturation of pro‐caspase‐1 to caspase‐1. Caspase‐1 has the capacity to cleave inactive pro‐inflammatory cytokines to their active counterparts, such as pro‐interleukin‐1β (pro‐IL‐1β) to IL‐1β.8 Therefore, it is clear that although NLRs may react differently upon stimulation they have co‐operative effects essential for an innate immune response.

NLRs in disease

The discovery of several genetic loss‐of‐function and gain‐of‐function polymorphisms fuelled extensive research to establish whether defective NOD1 and NOD2 function or regulation has a role to play in chronic inflammation. Expression studies revealed aberrant NOD1 and NOD2 expression in states of chronic inflammation, implicating the receptors in a range of inflammatory diseases (summarized in Table 1). We will review some of the recent evidence linking NOD1 and NOD2 with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), autoinflammatory disease, rheumatoid arthritis, allergy and cardiovascular and metabolic diseases, with our main focus being on IBD.

Table 1.

Expression of NOD1 and NOD2 in chronic inflammatory disorders

| Category | Disorder | Cells/Tissues studied | NLR | NLR expression | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inflammatory bowel disease | Ulcerative colitis | Lower colonic mucosal biopsies from healthy and UC patients with severe/mild inflammation or are in remission. | NOD1 | Eightfold increase in severe UC patients relative to mild/healthy samples. Remission patients had similar expression levels to healthy individual. | 34 |

| Crohn's disease | Paneth cells from ileal crypts of CD patients. | NOD2 | Increased in ileal crypts. No increase in colonic crypts. | 41 | |

| Autoimmune disease | Blau syndrome | BMDMs from WT or NOD2 R314Q knock‐in mice. | NOD2 | Stimulation with poly(I:C) increased NOD2 expression in WT but not NOD2 R314Q knock‐in cells. | 67 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | Synovial macrophages and fibroblasts from synovium of RA patients. | NOD2 | Increased expression in the synovium of RA patients. | 68 | |

| Synovial tissue from RA patients. | NOD1 | Increased expression in lining and sublining of RA synovial tissue. | 69 | ||

| Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) and synovial fluid T cells (SFTCs) from RA patients. | NOD1 | No increase in expression in PBMCs or SFTCs. | 70 | ||

| NOD2 | Significantly increased expression in PBMCs and SFTCs. | ||||

| Allergic reaction | Allergic rhinitis | Human nasal epithelial cells (HNECs) isolated from nasal mucosa biopsies of AR patients in/out of pollen season. | NOD1 | Reduced expression in HNECs from pollen season AR sufferers, relative to AR sufferers outside pollen season. | 71 |

| NOD2 | Expression uniform between AR sufferers and healthy controls regardless of pollen season | ||||

| Nasal mucosal biopsies from AR patients. | NOD1 | Increased in AR patients relative to healthy individuals. | 72 | ||

| NOD2 | Increased in AR patients relative to healthy individuals. | ||||

| Cardiovascular disease | Atherosclerosis | Serum from Apoe−/− and Apoe−/− Nod1−/− mice. | NOD1 | Required for atherosclerotic lesions development. | 76 |

| Endothelial cells and macrophages from human carotid plaques and healthy arteries. | NOD2 | Fourfold expression increase in plaques relative to healthy mammary arteries. Barely detectable in healthy arteries. | 77 | ||

| Behçet disease | Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) from BD patients and healthy controls. | NOD2 | Increased significantly in BD patients relative to healthy controls | 74 | |

| Metabolic disease | Metabolic syndrome | Abdominal subcutaneous adipose tissue and adipocytes from MetS patients and healthy controls. | NOD1 | Increased expression in MetS adipose tissue and adipocytes. | 80 |

| NOD2 | No significant expression difference between MetS and healthy controls. | ||||

| Gestational diabetes | Subcutaneous and omental adipose tissue from GDM and normal glucose tolerance (NGT) women. | NOD1 | Expression significantly higher in GDM women relative to NGT women. | 81 |

Abbreviations: AR, allergic rhinitis; BD, Behçet's disease; BMDM, bone‐marrow‐derived macrophages; CD, Crohn's disesae; GDM, gestational diabetes mellitus; HNEC, human nasal epithelial cells; IEC, intraepithelial cells; NGT, normal glucose tolerance; NLR, NOD‐like receptor; NOD1, nucleotide‐binding oligomerization domain 1; PBMC, peripheral blood mononuclear cells; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; SFTC, synovial fluid T cells; UC, ulcerative colitis; WT, wild‐type.

Listed in this table are studies that have made direct links between chronic inflammatory disorders and increased NOD1/NOD2 expression and their findings. Disorders associated with NOD1/NOD2 include inflammatory bowel disease, autoimmune disease, allergic reactions, cardiovascular disease and metabolic diseases.

Inflammatory bowel disease is the collective term for a group of autoimmune disorders causing chronic, transmural inflammation within varying segments of the digestive tract. The aetiology of IBD has yet to be fully elucidated; however, it is postulated that it is caused by excessive activation of the innate immune response in the mucosal cell lining.33 Crohn's disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC) are the primary subtypes of IBD, whose pathologies share similarities but differ in location within the gastrointestinal tract. Ulcerative colitis is characterized by chronic inflammation localized to the colon and rectum.33 Analysis of colon mucosal biopsies from patients with UC revealed an eightfold increase in NOD1 expression relative to control biopsies. Analysis of biopsies from the same cohort of UC patients during remission revealed a reduction in NOD1 expression relative to control biopsy levels. These findings suggest heightened NOD1 expression as a contributing factor behind the UC chronic inflammatory state.34

Crohn's Disease can manifest across any region of the gastrointestinal tract and can be further classified according to the region affected and its clinical presentation.35 In 2001, the first genetic links to CD were established.36, 37 Extensive research has demonstrated three polymorphisms within or neighbouring the LRR region of the NOD2 gene directly associated with the disease. Of the three polymorphisms, one takes the form of a frame‐shift mutation (L1007fs) whereas the other two are missense mutations (R702W and G908R).36, 37, 38 Interestingly, individuals who are heterozygous for NOD2 variants have a twofold to fourfold increased risk of developing CD, whereas homozygous variants have an additional risk of 20‐ to 40‐fold.36, 37, 39 Regardless of this significant risk upsurge, most individuals possessing two NOD2 variants do not develop the chronic inflammatory disorder. This finding is supported by a knock‐in murine study whereby the L1007fs NOD2 variant was introduced into both alleles of mice, thereby generating homozygous variants. When maintained within a specific‐pathogen‐free environment the variants did not spontaneously develop intestinal inflammation,40 suggesting that other factors are involved in disease onset.

These polymorphisms have been regarded as loss‐of‐function, with NOD2 variants having diminished responsiveness to MDP. There have been several proposed mechanisms by which NOD2 loss‐of‐function results in exacerbated inflammation. NOD2 has been found to maintain the intestinal epithelial barrier by regulating antimicrobial agent release and sustaining bacterial levels and population types. NOD2 variants may lose this protective function, providing insufficient bacterial clearance and allowing excessive bacterial invasion, resulting in augmented inflammation through NOD2‐independent pro‐inflammatory pathways.15, 40 The NOD2 receptor is highly expressed within Paneth cells, which are specialized cells located at the base of the intestinal crypts of Lieberkühn. These cells are most numerous in the terminal ileum of the small intestine, which is interestingly the most commonly affected site in CD sufferers. These cells release antimicrobial agents, such as α‐defensin, collectively referred to as cryptdins.41, 42 Disruption of Paneth cell function (and α‐defensin release), potentially as a result of NOD2 deficiency, could alter the load and composition of the intestinal flora, an attribute of IBD.42 Early studies investigating the effect of NOD2 polymorphisms on release of α‐defensin from Paneth cells recorded reduced release in patients with ileal CD holding the NOD2 L1007fs polymorphism.43, 44 However, more recent data imply that the reduction recorded is in fact a secondary effect of the NOD2 knock‐down, whereby defective NOD2 results in excessive inflammation, which in turn blocks the release of α‐defensin.45 Therefore, it appears that Paneth cell dysfunction may be a consequence of, as opposed to a contributor to, NOD2 loss‐of‐function.

Intestinal epithelial cells are exposed to trillions of bacteria on a daily basis; however, a healthy intestine appears to be able to deal with this without causing excessive inflammation.46 Several studies have recorded aberrant bacterial content and load in the intestines of Crohn's patients relative to healthy comparators.47, 48, 49, 50 Commensal bacteria play a crucial role in preventing pathogenic invasion and colonization by restoring the epithelial barrier and assisting mucosal immune cells in upholding a basal immune response.51 NOD2 and commensal bacteria function in a feedback loop, whereby commensal bacteria promote NOD2 expression, which in turn negatively feeds back and prevents over‐expansion of commensal communities.52 This highlights the important role played by NOD2 in maintaining a peaceful balance between the microbiome and host immune responses. An imbalance in this relationship can result in dysbiosis, whereby pathogenic bacteria begin to outweigh symbiotic bacteria causing the intestinal epithelial barrier to become overwhelmed, thereby allowing bacterial invasion and associated inflammation to ensue.52, 53

Defective NOD2 has been linked to altered patterns in the microbiome and diminished integrity of the epithelial barrier. Knockdown of NOD2 expression was found to significantly weaken bacterial‐killing ability by crypts harvested from the terminal ilea.54 This diminished bactericidal activity was complimented by data indicating significantly enhanced colonization by the pathogenic bacteria Helicobacter hepaticus in NOD2‐deficient mice.54 Additionally, NOD2‐deficient mice have been recorded as having altered phyla content in their terminal ilea. There are still conflicting data regarding which phyla are affected by NOD2 mutations and the level at which they are affected. However, it generally appears that levels of Bacteroides and Firmicutes (two most abundant phyla in the intestine) are increased in NOD2‐deficient mice.51, 53 Dysbiosis has been recorded in patients with CD and has also been associated with polymorphisms in NOD2 and the autophagy‐related 16 like 1 (ATG16L1) genes. However, it remains unclear whether this bacterial imbalance is a consequence or cause of these genetic mutations.42, 55

Autophagy is a self‐degrading cellular process that plays an important role during cell starvation and bacterial invasion. During times of nutrient deprivation or bacterial invasion this ‘self‐eating’ process is called upon to encapsulate less vital organelles or invading pathogens, respectively, sentencing them to lysosomal degradation. This protective mechanism thereby assists survival by reallocating cellular energy during periods of starvation and ridding the cell of invading pathogens.56, 57 NOD2 and ATG16L1 proteins physically interact with each other.58, 59 This highlights a potential regulatory role for ATG16L1 in NOD2 pro‐inflammatory signalling and bacterial clearance.

The precise way in which ATG16L1 influences NOD2‐associated inflammation is not yet certain, with several theories surfacing. One hypothesis proposes that this autophagy‐associated protein assists MDP trafficking within the cell, thereby assisting NOD2 signalling, although some conflicting results have been published.58, 60, 61 Conversely, a negative regulatory function for ATG16L1 was proposed, suggesting that ATG16L1 dampens NOD1‐ and NOD2‐dependent pro‐inflammatory signalling by blocking polyubiquitination and subsequent activation of the adaptor protein, RIP2.62

Another theory postulates that upon activation of NOD1 and NOD2 intracellular receptors by bacterial invasion, autophagy is promoted in parallel with pro‐inflammatory signalling to assist bacterial degradation.59 This theory is supported by research on individuals with NOD2 and ATG16L1 variants, which unveiled defective innate immune responses and bacterial clearance. NOD2 variants cannot effectively respond to invading pathogens, a deficit which the cell attempts to counteract by enhancing the adaptive immune response through excess monocyte activation and phagocytosis. Excessive phagocytosis results in an accumulation of bacteria within the cell interior. If the autophagic response of the cell is defective, due to an ATG16L1 polymorphism, it will be unable to clear the internalized bacteria as efficiently as is needed to counteract the increased bacterial insult.63 This combination of defective innate immune responses by NOD2 and ineffective bacterial clearance by autophagy could together be responsible for CD development and progression.

The direct association between NLRs and IBD would suggest that NOD1 and NOD2 may be playing a role in similar disease states. Therefore, NOD1/NOD2 expression patterns have been investigated in a wide range of chronic inflammatory diseases, as outlined below and summarized in Table 1. Blau syndrome is a rare dominant autoinflammatory disorder, characterized by granulomatous inflammatory arthritis, uveitis and dermatitis.64 Blau syndrome has been linked to three missense mutations in the NACHT domain of the NOD2 gene; R334Q, R334W and L469F.65, 66 NOD2 has been recorded as being less responsive to MDP in Blau syndrome mutants.67 These data propose that the effects of the R314Q mutation may manifest during translation, causing a truncated form of NOD2 to materialize that has reduced functionality.67 Rheumatoid arthritis is a common chronic inflammatory disease affecting synovial tissue. Expression of NOD1 and NOD2 in this tissue has been found to be augmented in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, implicating these receptors in disease development and/or progression.68, 69, 70 Allergic rhinitis is a highly prevalent disorder affecting the nasal cavity following exposure to common allergens such as pollen, dust, mould spores or animal dander. It is now believed that bacterial infection could also contribute to allergic rhinitis development through NOD1 and NOD2 activation. Studies have suggested that altered NOD1 and/or NOD2 expression may contribute to allergic rhinitis but further studies are needed to clarify their role in this disorder.71, 72 Cardiovascular disease in the form of atherosclerosis, characterized by the accumulation and subsequent maturation of leucocytes into cholesterol‐laden foam cells at vessel walls,73 and Behçet's disease, a rare disorder characterized by inflammation of the blood vessel walls,74 have been associated with aberrant NOD1 and NOD2 expression.74, 75, 76, 77 Finally, diet‐induced adipocyte inflammation, referred to as metabolic disease, can manifest as either metabolic syndrome or gestational diabetes mellitus. Enhanced NOD1 expression has been recorded in these diet‐induced conditions, supporting a role for NOD1 in ‘metainflammation’.78, 79, 80, 81 To conclude, current knowledge has identified a strong link between NOD1/NOD2 and IBD development. Support for the role of NOD1 and/or NOD2 in the other chronic inflammatory diseases, as listed in Table 1, is still in a relatively early stage of research and further analysis is needed to confirm their role in these diseases.

Mechanisms of regulation

With many studies reporting changes in expression during disease states, it is important to understand how these receptors may be regulated. Regulation of the NOD1/NOD2 signalling pathway is necessary to maintain cellular homeostasis, thereby preventing an excessive or insufficient immune response (regulators of NOD1 and NOD2 receptors are outlined in Table 2). There is growing evidence that the tumour necrosis factor‐α (TNF‐α) induced protein 3 (TNFAIP3) ubiquitin ligase, otherwise referred to as A20, is a negative regulator of the NOD‐induced NF‐κB signalling pathway. One study revealed that in cells deficient in A20, levels of polyubiquitinated RIP2 increased, which was accompanied by enhanced NF‐κB signalling.82 In addition, cells over‐expressing A20 dose‐dependently inhibited NOD2 activity. It seems that NOD2 and A20 are part of a negative feedback loop as functional NOD2 has been found to be required for A20 activation.83 It has been proposed that A20 diminishes signalling through complimentary processes carried out by its different domains. The N terminus of A20 removes K63‐linked polyubiquitin chains from the C terminus and adds K48‐linked polyubiquitin chains to RIP2, which together switch off the NF‐κB signalling.82, 83 Interestingly, single nucleotide polymorphisms within the A20 gene have been directly associated with several chronic inflammatory diseases including rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis and systemic lupus erythematous.84 The link between A20 and IBD has stood out with various genetic studies independently identifying this regulator as a susceptibility locus for CD.85, 86 Analysis of CD biopsy samples revealed either diminished or defective A20 protein relative to healthy control samples.87 In addition, studies carried out on A20‐deficient mice uncovered hypersensitivity to dextran sulphate sodium‐induced colitis and increased responsiveness to TNF‐α.88, 89 Collectively, these data suggest that loss of A20‐assisted regulation of NOD2 activity may result in an excessive response to commensal microbiota and unwarranted inflammatory responses.

Table 2.

NOD1 and NOD2 regulators

| Type | Regulator | NLR | Target | Proposed regulation mechanism | Cell type | Refs | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cell line type | Primary cells | ||||||

| Negative | A20/TNFAIP3 | NOD1/2 | RIP2 protein downstream of NOD2. | Removes K63‐linked polyubiquitin chains and adds K48‐linked polyubiquitin chains to RIP2, which subsequently switches off RIP2‐dependent NF‐κB signalling and sends RIP2 for proteosomal degradation. | Embryonic kidney | BMDMs from Tnfaip3 −/− and Tnfaip3 +/+ mice. | 82, 83 |

| Leukemia blood | BMDMs from NOD2wt and NOD2 −/− mice. | ||||||

| RNF34 | NOD1 | NOD1 protein. | K48‐linked polyubiquitination of NOD1, assisting NOD1 proteosomal degradation. | Embryonic kidney | N/A | 90 | |

| Colonic epithelial | |||||||

| PSMA7 | NOD1 | NOD1 protein. | K48‐linked polyubiquitination of NOD1, assisting NOD1 proteosomal degradation. | Embryonic kidney | N/A | 91 | |

| Colonic epithelial | |||||||

| TRIM27 | NOD2 | NOD2 protein. | K48‐linked polyubiquitination of NOD2, assisting NOD2 proteosomal degradation. | Embryonic kidney | Colon sections/biopsies from healthy and CD patients. | 92 | |

| Colonic epithelial | |||||||

| Cervical epithelial | |||||||

| Erbin | NOD2 | NOD2 protein. | Reduces NOD2 sensitivity to MDP stimulation. | Embryonic kidney | Mouse Embryo Fibroblasts (MEFs) isolated from Erbin+/+, Erbin+/−, and Erbin−/− mouse embryos. | 93, 94 | |

| Colonic epithelial | |||||||

| Leukemia blood | |||||||

| Cervical epithelial | |||||||

| CAD | NOD2 | NOD2 protein. | Diminishes NOD2‐associated NF‐κB and MAPK signalling and bacterial management. | Colonic epithelial | Colonic tissue sections from healthy and IBD patients. | 95 | |

| Embryonic kidney | |||||||

| CARD8 | NOD2 | NOD2 protein. | Blocks self‐oligomerisation of NOD2 or masks binding sites essential for signalosome assembly. | Cervical epithelial | Colonic tissue biopsies from healthy and CD patients. | 96 | |

| Embryonic kidney | |||||||

| Positive | IFN‐γ cytokine | NOD1 | IRF‐1 protein. | IFN‐γ enhances IRF‐1 protein expression, which in turn promotes NOD1 transcription. | Colonic epithelial | Intestinal epithelial cells from colonic mucosal biopsies. | 99 |

| TNF‐α (and IFNγ) cytokines | NOD2 | NOD2 protein. | TNF‐α enhances NOD2 expression and this effect is augmented by IFN‐γ stimulation. | Leukemia blood | Peripheral blood progenitor cells. | 101, 102 | |

| Breast epithelial | |||||||

| Cervical epithelial | Colonic mucosal biopsies from IBD patients | ||||||

| Colonic epithelial | |||||||

| Butyrate | NOD2 | Histone proteins at NOD2 promoter | Supports acetylation at H3 and H4 histone proteins, exposing NOD2 for transcription. | Colonic epithelial | N/A | 104 | |

Abbreviations: BMDM, bone‐marrow‐derived macrophages; CD, Crohn's disesae; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; MDP, muramyl dipeptide; NOD1, nucleotide‐binding oligomerization domain 1.

Listed in this table are negative and positive regulators of NOD1 and NOD2 receptor activity. Regulators are classified according to regulator type, NLR regulated, target protein, mechanism of action and cell type studies have been carried out on. Negative regulators include A20/TNFAIP3, RNF34, PSMA7, TRIM27, Erbin, CAD and CARD8. Positive regulators include interferon‐γ, tumour necrosis factor‐α and butyrate.

The ring finger protein 34 (RNF34) E3 ubiquitin ligase and the 20S proteasome subunit α 7 (PSMA7), have both been proposed as novel negative regulators of NOD1 signalling. In vitro studies have uncovered NOD1 activity to be indirectly proportional to both RNF3490 and PSMA791 levels. The proposed mechanism of negative regulation for RNF34 and PSMA7 is by way of the ubiquitin/proteasome pathway, whereby NOD1 is K48‐ubiquitinated, thereby targeting it to the proteasome for degradation by proteolysis. This mechanism was supported by inhibition studies, whereby the inhibitory effects of RNF34 and PSMA7 on NOD1 activity were significantly impeded by treatment with a proteasome inhibitor (MG132)90 or small interfering RNA knockdown of PSMA7,91 respectively. RNF34 and PSMA7 expression studies have yet to be carried out to establish whether these proteins are directly linked to chronic inflammatory disease.

Tripartite motif containing 27 (TRIM27) E3 ubiquitin ligase has been found to physically interact with NOD2 with high affinity. This mediates K48‐linked ubiquitination of NOD2 leading to degradation of the receptor. In addition, MDP stimulation strengthens the NOD2–TRIM27 interaction and ubiquitination of NOD2. TRIM27 was linked directly to CD through analysis of colon sections taken from patients with CD, which showed enhanced TRIM27 expression relative to healthy patients.92 These data propose that up‐regulated TRIM27 could dampen basal NOD2 activity, leading to disturbed intestinal homeostasis.

Erb‐B2 Receptor Tyrosine Kinase 2 interacting protein (Erbin) specifically interacts with NOD2 protein, and has been proposed as a negative regulator of NOD2 activity in vitro and in vivo. Erbin over‐expression dose‐dependently reduces MDP‐induced NOD2 signalling. Conversely, Erbin knockdown resulted in increased NOD2 receptor responsiveness to MDP.93, 94 Therefore, it appears that the molecular mechanism underlying Erbin regulation is through alteration of MDP sensitivity. The expression of this negative regulator has yet to elucidated in disease models; however, we would expect for this protein to be down‐regulated in patients suffering NOD2‐associated chronic inflammation.

Carbamoyl phosphate synthetase/aspartate transcarbamylase/dihydroorotase (CAD), an essential enzyme in the de novo synthesis of pyrimidine nucleotides, was uncovered as another potential regulator of NOD2 by immunoprecipitation‐coupled mass spectrometry in an attempt to identify novel NOD2 regulators. CAD was found to directly interact with NOD2 and over‐expression of the enzyme diminished NOD2‐associated NF‐κB and mitogen‐activating protein kinase signalling as well as bacterial management. These effects point to CAD as a potential negative regulator of NOD2 activity, an indication that was supported by CAD knockdown whereby reduced CAD expression or CAD inhibition augmented NOD2 signalling and antibacterial ability. CAD levels were quantified in the intestinal epithelium of patients with CD, with higher CAD levels being recorded in patients with CD compared with healthy controls.95 This finding suggests that CAD up‐regulation in the intestine could result in reduced NOD2 levels, subsequently leading to loss of intestinal homeostasis.

CARD8 has been investigated for its NOD2 modulating effects. CARD8 and NOD2 were found to co‐localize and interact with each other through their FIIND and NACHT domains, respectively. Functional analysis revealed that CARD8 masked NOD2 bacterial management and MDP‐stimulated NF‐κB pro‐inflammatory signalling.96 Analysis of colonic mucosal biopsies from patients with CD revealed significantly higher CARD8 expression relative to healthy comparators.96 This link to CD is reinforced by studies investigating the connection to a specific polymorphism in CARD8 (rs2043211). A recent meta‐analysis identified that this CARD8 polymorphism significantly enhanced CD susceptibility.97 This CARD8 variant has also been linked to other NLR‐associated diseases, including atherosclerosis, with elevated CARD8 mRNA expression recorded in atherosclerotic plaques.98

Research carried out so far identified fewer positive regulators of NOD1 and NOD2. Recent evidence has shown that pro‐inflammatory cytokines may regulate NOD1 and NOD2 expression. Interferon‐γ (IFN‐γ) was found to indirectly increase NOD1 mRNA and protein expression dose and time dependently, through augmentation of nuclear IFN regulatory factor 1. NOD1 expression promotion in response to cytokines appears to be specific to IFN‐γ, because other cytokines including TNF‐α and IL‐1β do not have an impact on NOD1 levels.99 However, TNF‐α had previously been found to intensify NF‐κB signalling by promoting the liberation of NF‐κB from the inhibitory effects of IκBα through phosphorylation and dissociation of IκBα.100 Building on this finding, an intestinal epithelial cell line treated with TNF‐α increased NOD2 mRNA levels.101 Subsequent studies using epithelial cell lines and primary intestinal epithelial cells uncovered increases in NOD2 mRNA and protein levels in response to treatment with TNF‐α.102 Unlike with NOD1, IFN‐γ exposure did not appear to up‐regulate NOD2 expression alone; however, this cytokine did have a synergistic response alongside TNF‐α whereby IFN‐γ augmented the TNF‐α‐induced increase in NOD2 expression.102

Diet may also play a role in NOD regulation. Butyrate is a short‐chain fatty acid that is generated as a by‐product of anaerobic fermentation of dietary fibres in the intestine. A role for butyrate in the maintenance of intestinal immunity is now evident. A study found PGN‐induced NF‐κB transactivation to be increased sevenfold in the presence of butyrate. Additionally, butyrate appeared to significantly strengthen the interaction between the activated p65 transcription factor and pro‐inflammatory cytokine/chemokine genes. Butyrate was found to increase NOD2 expression in a dose‐dependent manner, without altering the receptor's half‐life. Butyrate had previously been found to have histone deacetylase inhibitory properties.103 Studies showed that it also promotes NOD2 transcription by supporting acetylation of H3 and H4 at the NOD2 gene promoter.104 Interestingly, treating patients with IBD with butyrate was found to reduce intestinal inflammation, possibly by restoring a healthy NOD2 response to commensal bacteria.105

The research outlined above has uncovered several NOD1/2‐negative and ‐positive regulators. An imbalance between regulators could indirectly disrupt inflammatory homeostasis and result in an inappropriate response to bacterial insult, potentially manifesting as a NOD1/2‐associated disease. Hence, reduced expression of negative regulators or enhanced expression of positive regulators could be indirectly contributing to excess inflammation in chronic inflammatory diseases. The interactions identified between each of these regulators and NOD1/2, alongside the direct link between some of these regulators and CD, suggests regulator targeting as a new therapeutic intervention point for chronic inflammatory disorders.

Aside from negative/positive regulation led by the proteins identified above and Table 2, NLR gene expression could be regulated by epigenetic modifications. Epigenetic mechanisms have the ability to alter gene expression through DNA methylation, histone modifications and RNA interference.106 Research exploring the link between NLRs and DNA methylation is beginning to emerge, with the main focus being on NOD2. Age‐associated CpG sites, at which DNA methylation patterns change over an individual's lifetime, have been identified in the promoter region of NOD2.107 This finding would suggest that if these sites exist in NOD2 then the associated changes in methylation could be altering expression of the underlying NOD2 gene. Research quantifying global and NOD2‐specific DNA methylation status in states of chronic inflammatory disease is beginning to emerge. Global hypomethylation has been recorded in rheumatoid arthritis synovial fibroblasts. Atheromatous plaque lesions were associated with NOD2 hypomethylation relative to plaque‐free intima, which correlates with the increased NOD2 expression in patients suffering from atherosclerosis.108, 109 These data, alongside what we know about the influence of epigenetic modifications on gene expression, potentially provide an explanation for NLR expression patterns identified in chronic inflammatory diseases. As mentioned earlier, homozygous genetic NOD2 variants have a 20‐ to 40‐fold increased risk of developing CD but disease onset is not guaranteed. This implies that certain environmental/lifestyle factors encountered during a variant's lifetime are potentially modifying epigenetic patterns surrounding NOD2 and inducing CD development. The role played by epigenetic modifications in NLR expression regulation is still in its infant stage. However, as our knowledge of the NLR epigenetic profile expands, we predict that the role played by epigenetic modifications in NLR expression regulation will be uncovered.

Perspectives and Conclusions

Chronic inflammation is considered a cause of a number of diseases, as opposed to a side‐effect. Mounting evidence links aberrant NOD1 and NOD2 expression to many chronic inflammatory disorders. As outlined in Table 1, in vitro and in vivo studies have recorded increased NOD1/NOD2 expression in numerous diseased states. Although these studies identify an increase in expression, they fail to establish the mechanisms underlying NOD1/NOD2 gene expression regulation. Therefore, questions remain, including how NOD‐associated innate immune responses are regulated at the genetic level and what factors contribute. Some studies have associated NOD1/NOD2 genetic polymorphisms to altered receptor expression, such as those associated with CD. However, as our knowledge of gene expression regulation grows, it suggests that NOD1/NOD2 expression dysregulation stretches beyond genetics and potentially into epigenetic mechanisms. If the mechanisms controlling NOD expression could be deciphered then we could potentially identify regulators underlying different chronic inflammatory disorders and rectify their function pharmacologically, so restoring the normal innate immune response. Answers to these remaining questions could lead to the development of more effective therapies for inflammatory disorders linked to NLR dysregulation.

Disclosures

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

CL Feerick is a Hardiman scholar.

References

- 1. Kawai T, Akira S. The roles of TLRs, RLRs and NLRs in pathogen recognition. Int Immunol 2009; 21:317–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Franchi L, et al Function of Nod‐like receptors in microbial recognition and host defense. Immunol Rev 2009; 227:106–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kanneganti TD, Lamkanfi M, Nunez G. Intracellular NOD‐like receptors in host defense and disease. Immunity 2007; 27:549–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ting JP, et al The NLR gene family: a standard nomenclature. Immunity 2008; 28:285–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Inohara N, et al Human Nod1 confers responsiveness to bacterial lipopolysaccharides. J Biol Chem 2001; 276:2551–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ogura Y, et al Nod2, a Nod1/Apaf‐1 family member that is restricted to monocytes and activates NF‐κB. J Biol Chem 2001; 276:4812–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Proell M, et al The Nod‐like receptor (NLR) family: a tale of similarities and differences. PLoS One 2008; 3:e2119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Martinon F, Tschopp J. NLRs join TLRs as innate sensors of pathogens. Trends Immunol 2005; 26:447–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Said‐Sadier N, Ojcius DM. Alarmins, inflammasomes and immunity. Biomed J 2012; 35:437–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Inohara N, et al NOD‐LRR proteins: role in host‐microbial interactions and inflammatory disease. Annu Rev Biochem 2005; 74:355–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chen G, et al NOD‐like receptors: role in innate immunity and inflammatory disease. Annu Rev Pathol 2009; 4:365–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chamaillard M, et al An essential role for NOD1 in host recognition of bacterial peptidoglycan containing diaminopimelic acid. Nat Immunol 2003; 4:702–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Girardin SE, et al Nod1 detects a unique muropeptide from Gram‐negative bacterial peptidoglycan. Science 2003; 300:1584–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Girardin SE, et al Nod2 is a general sensor of peptidoglycan through muramyl dipeptide (MDP) detection. J Biol Chem 2003; 278:8869–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Inohara N, et al Host recognition of bacterial muramyl dipeptide mediated through NOD2: implications for Crohn′s disease. J Biol Chem 2003; 278:5509–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Iyer JK, Coggeshall KM. Cutting edge: primary innate immune cells respond efficiently to polymeric peptidoglycan, but not to peptidoglycan monomers. J Immunol 2011; 186:3841–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Schaffler H, et al NOD2 stimulation by Staphylococcus aureus‐derived peptidoglycan is boosted by Toll‐like receptor 2 costimulation with lipoproteins in dendritic cells. Infect Immun 2014; 82:4681–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fiocca R, et al Release of Helicobacter pylori vacuolating cytotoxin by both a specific secretion pathway and budding of outer membrane vesicles. Uptake of released toxin and vesicles by gastric epithelium. J Pathol 1999; 188:220–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lee J, et al pH‐dependent internalization of muramyl peptides from early endosomes enables Nod1 and Nod2 signaling. J Biol Chem 2009; 284:23818–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Viala J, et al Nod1 responds to peptidoglycan delivered by the Helicobacter pylori cag pathogenicity island. Nat Immunol 2004; 5:1166–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Vavricka SR, et al hPepT1 transports muramyl dipeptide, activating NF‐κB and stimulating IL‐8 secretion in human colonic Caco2/bbe cells. Gastroenterology 2004; 127:1401–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kasper CA, et al Cell–cell propagation of NF‐κB transcription factor and MAP kinase activation amplifies innate immunity against bacterial infection. Immunity 2010; 33:804–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hahn JS. Regulation of Nod1 by Hsp90 chaperone complex. FEBS Lett 2005; 579:4513–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lee K‐H, et al Proteasomal degradation of Nod2 protein mediates tolerance to bacterial cell wall components. J Biol Chem 2012; 287:39800–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mohanan V, Grimes CL. Hsp70 binds to and stabilizes Nod2, an innate immune receptor involved in Crohn's disease. J Biol Chem 2014; 289:18987–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hsu LC, et al A NOD2‐NALP1 complex mediates caspase‐1‐dependent IL‐1β secretion in response to Bacillus anthracis infection and muramyl dipeptide. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2008; 105:7803–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Park JH, et al RICK/RIP2 mediates innate immune responses induced through Nod1 and Nod2 but not TLRs. J Immunol 2007; 178:2380–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hasegawa M, et al A critical role of RICK/RIP2 polyubiquitination in Nod‐induced NF‐κB activation. EMBO J 2008; 27:373–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. DiDonato JA, et al A cytokine‐responsive IκB kinase that activates the transcription factor NF‐κB. Nature 1997; 388:548–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Yamaoka S, et al Complementation cloning of NEMO, a component of the IκB kinase complex Essential for NF‐κB activation. Cell 1998; 93:1231–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Shaw MH, et al NOD‐like receptors (NLRs): bona fide intracellular microbial sensors. Curr Opin Immunol 2008; 20:377–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Vandenabeele P, Bertrand MJ. The role of the IAP E3 ubiquitin ligases in regulating pattern‐recognition receptor signalling. Nat Rev Immunol 2012; 12:833–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Maloy KJ, Powrie F. Intestinal homeostasis and its breakdown in inflammatory bowel disease. Nature 2011; 474:298–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Verma R, Verma N, Paul J. Expression of inflammatory genes in the colon of ulcerative colitis patients varies with activity both at the mRNA and protein level. Eur Cytokine Netw 2013; 24:130–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Maglinte DD, et al Classification of small bowel Crohn's subtypes based on multimodality imaging. Radiol Clin North Am 2003; 41:285–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ogura Y, et al A frameshift mutation in NOD2 associated with susceptibility to Crohn's disease. Nature 2001; 411:603–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hugot J‐P, et al Association of NOD2 leucine‐rich repeat variants with susceptibility to Crohn's disease. Nature 2001; 411:599–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Russell RK, Nimmo ER, Satsangi J. Molecular genetics of Crohn's disease. Curr Opin Genet Dev 2004; 14:264–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hugot J‐P, et al Prevalence of CARD15//NOD2 mutations in Caucasian healthy people. Am J Gastroenterol 2007; 102:1259–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kim Y‐G, et al Cutting edge: Crohn's disease‐associated Nod2 mutation limits production of proinflammatory cytokines to protect the host from Enterococcus faecalis‐induced lethality. J Immunol 2011; 187:2849–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ogura Y, et al Expression of NOD2 in Paneth cells: a possible link to Crohn's ileitis. Gut 2003; 52:1591–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Frank DN, et al Disease phenotype and genotype are associated with shifts in intestinal‐associated microbiota in inflammatory bowel diseases. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2011; 17:179–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Wehkamp J, et al NOD2 (CARD15) mutations in Crohn's disease are associated with diminished mucosal α‐defensin expression. Gut 2004; 53:1658–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Wehkamp J, et al Reduced Paneth cell α‐defensins in ileal Crohn's disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2005; 102:18129–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Simms LA, et al Reduced α‐defensin expression is associated with inflammation and not NOD2 mutation status in ileal Crohn's disease. Gut 2008; 57:903–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Ferreira CM, et al The central role of the gut microbiota in chronic inflammatory diseases. J Immunol Res 2014; 2014:12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Seksik P, et al Alterations of the dominant faecal bacterial groups in patients with Crohn's disease of the colon. Gut 2003; 52:237–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Ott SJ, et al Reduction in diversity of the colonic mucosa associated bacterial microflora in patients with active inflammatory bowel disease. Gut 2004; 53:685–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Manichanh C, et al Reduced diversity of faecal microbiota in Crohn's disease revealed by a metagenomic approach. Gut 2006; 55:205–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Jia W, et al Diversity and distribution of sulphate‐reducing bacteria in human faeces from healthy subjects and patients with inflammatory bowel disease. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 2012; 65:55–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Rehman A, et al Nod2 is essential for temporal development of intestinal microbial communities. Gut 2011; 60:1354–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Biswas A, Petnicki‐Ocwieja T, Kobayashi KS. Nod2: a key regulator linking microbiota to intestinal mucosal immunity. J Mol Med (Berl) 2012; 90:15–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Ramanan D, et al Bacterial sensor Nod2 prevents inflammation of the small intestine by restricting the expansion of the commensal Bacteroides vulgatus . Immunity 2014; 41:311–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Petnicki‐Ocwieja T, et al Nod2 is required for the regulation of commensal microbiota in the intestine. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2009; 106:15813–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Hold GL, et al Role of the gut microbiota in inflammatory bowel disease pathogenesis: what have we learnt in the past 10 years? World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20:1192–210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Patel KK, Stappenbeck TS. Autophagy and intestinal homeostasis. Annu Rev Physiol 2013; 75:241–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Glick D, Barth S, Macleod KF. Autophagy: cellular and molecular mechanisms. J Pathol 2010; 221:3–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Homer CR, et al ATG16L1 and NOD2 interact in an autophagy‐dependent antibacterial pathway implicated in Crohn's disease pathogenesis. Gastroenterology 2010; 139: 1630–41, 1641 e1‐2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Travassos LH, et al Nod1 and Nod2 direct autophagy by recruiting ATG16L1 to the plasma membrane at the site of bacterial entry. Nat Immunol 2010; 11:55–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Saitoh T, et al Loss of the autophagy protein Atg16L1 enhances endotoxin‐induced IL‐1β production. Nature 2008; 456:264–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Cooney R, et al NOD2 stimulation induces autophagy in dendritic cells influencing bacterial handling and antigen presentation. Nat Med 2010; 16:90–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Sorbara MT, et al The protein ATG16L1 suppresses inflammatory cytokines induced by the intracellular sensors Nod1 and Nod2 in an autophagy‐independent manner. Immunity 2013; 39:858–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Wolfkamp SC, et al ATG16L1 and NOD2 polymorphisms enhance phagocytosis in monocytes of Crohn's disease patients. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20:2664–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Blau EB. Familial granulomatous arthritis, iritis, and rash. J Pediatr 1985; 107:689–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Tromp G, et al Genetic linkage of familial granulomatous inflammatory arthritis, skin rash, and uveitis to chromosome 16. Am J Hum Genet 1996; 59:1097–107. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Miceli‐Richard C, et al CARD15 mutations in Blau syndrome. Nat Genet 2001; 29:19–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Dugan J, et al Blau syndrome‐associated Nod2 mutation alters expression of full‐length NOD2 and limits responses to muramyl dipeptide in knock‐in mice. J Immunol 2015; 194:349–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Ospelt C, et al Expression, regulation, and signaling of the pattern‐recognition receptor nucleotide‐binding oligomerization domain 2 in rheumatoid arthritis synovial fibroblasts. Arthritis Rheum 2009; 60:355–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Yokota K, et al The pattern‐recognition receptor nucleotide‐binding oligomerization domain‐containing protein 1 promotes production of inflammatory mediators in rheumatoid arthritis synovial fibroblasts. Arthritis Rheum 2012; 64:1329–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Franca R., et al Expression and activity of NOD1 and NOD2/RIPK2 signalling in mononuclear cells from patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Scand J Rheumatol 2015; 45:8–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Bogefors J, et al Nod1, Nod2 and Nalp3 receptors, new potential targets in treatment of allergic rhinitis? Allergy 2010; 65:1222–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Hu S, et al The expression of NOD1 and NOD2 and the regulation of glucocorticoids on them in allergic rhinitis. Lin Chung Er Bi Yan Hou Tou Jing Wai Ke Za Zhi 2013; 27:393–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Ross R. Atherosclerosis – an inflammatory disease. N Engl J Med 1999; 340:115–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Hamzaoui K, et al NOD2 is highly expressed in Behcet disease with pulmonary manifestations. J Inflamm 2012; 9:3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Nishio H, et al Nod1 ligands induce site‐specific vascular inflammation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2011; 31:1093–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Kanno S, et al Activation of an innate immune receptor, Nod1, accelerates atherogenesis in Apoe−/− mice. J Immunol 2015; 194:773–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Liu H‐Q, et al NOD2‐mediated innate immune signaling regulates the eicosanoids in atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2013; 33:2193–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Zhao L, et al NOD1 activation induces proinflammatory gene expression and insulin resistance in 3T3‐L1 adipocytes. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2011; 301:E587–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Grundy SM, et al Diagnosis and management of the metabolic syndrome: an American Heart Association/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Scientific Statement. Circulation 2005; 112:2735–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Zhou Y‐J, et al Increased NOD1, but not NOD2, activity in subcutaneous adipose tissue from patients with metabolic syndrome. Obesity 2015; 23:1394–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Lappas M. NOD1 expression is increased in the adipose tissue of women with gestational diabetes. J Endocrinol 2014; 222:99–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Hitotsumatsu O, et al The ubiquitin‐editing enzyme A20 restricts nucleotide‐binding oligomerization domain containing 2‐triggered signals. Immunity 2008; 28:381–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Billmann‐Born S, et al Genome‐wide expression profiling identifies an impairment of negative feedback signals in the Crohn's disease‐associated NOD2 variant L1007fsinsC. J Immunol 2011; 186:4027–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Musone SL, et al Sequencing of TNFAIP3 and association of variants with multiple autoimmune diseases. Genes Immun 2011; 12:176–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Barmada MM, et al A genome scan in 260 inflammatory bowel disease‐affected relative pairs. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2004; 10:513–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Bradbury LA, Brown MA. Genome‐wide association study of 14,000 cases of seven common diseases and 3,000 shared controls. Nature 2007; 447:661–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Arsenescu R, et al Signature biomarkers in Crohn's disease: toward a molecular classification. Mucosal Immunol 2008; 1:399–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Vereecke L, et al Enterocyte‐specific A20 deficiency sensitizes to tumor necrosis factor‐induced toxicity and experimental colitis. J Exp Med 2010; 207:1513–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Lee EG, et al Failure to regulate TNF‐induced NF‐κB and cell death responses in A20‐deficient mice. Science 2000; 289:2350–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Zhang R, et al The E3 ligase RNF34 is a novel negative regulator of the NOD1 pathway. Cell Physiol Biochem 2014; 33:1954–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Yang L, et al PSMA7 directly interacts with NOD1 and regulates its function. Cell Physiol Biochem 2013; 31:952–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Zurek B, et al TRIM27 negatively regulates NOD2 by ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation. PLoS One 2012; 7:e41255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. McDonald C, et al A role for erbin in the regulation of Nod2‐dependent NF‐κB signaling. J Biol Chem 2005; 280:40301–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Kufer TA, et al Role for erbin in bacterial activation of Nod2. Infect Immun 2006; 74:3115–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Richmond AL, et al The nucleotide synthesis enzyme CAD inhibits NOD2 antibacterial function in human intestinal epithelial cells. Gastroenterology 2012; 142: 1483–92 e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. von Kampen O, et al Caspase recruitment domain‐containing protein 8 (CARD8) negatively regulates NOD2‐mediated signaling. J Biol Chem 2010; 285:19921–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Liu J, et al Association between CARD8 rs2043211 polymorphism and inflammatory bowel disease: a meta‐analysis. Immunol Invest 2015; 44:253–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Paramel GV, et al CARD8 gene encoding a protein of innate immunity is expressed in human atherosclerosis and associated with markers of inflammation. Clin Sci (Lond) 2013; 125:401–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Hisamatsu T, Suzuki M, Podolsky DK. Interferon‐γ augments CARD4/NOD1 gene and protein expression through interferon regulatory factor‐1 in intestinal epithelial cells. J Biol Chem 2003; 278:32962–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Beg AA, et al Tumor necrosis factor and interleukin‐1 lead to phosphorylation and loss of IκBα: a mechanism for NF‐κB activation. Mol Cell Biol 1993; 13:3301–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Gutierrez O, et al Induction of Nod2 in myelomonocytic and intestinal epithelial cells via nuclear factor‐κB activation. J Biol Chem 2002; 277:41701–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Rosenstiel P, et al TNF‐α and IFN‐γ regulate the expression of the NOD2 (CARD15) gene in human intestinal epithelial cells. Gastroenterology 2003; 124:1001–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Candido EP, Reeves R, Davie JR. Sodium butyrate inhibits histone deacetylation in cultured cells. Cell 1978; 14:105–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Leung C‐H, et al Butyrate mediates nucleotide‐binding and oligomerisation domain (NOD) 2‐dependent mucosal immune responses against peptidoglycan. Eur J Immunol 2009; 39:3529–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Scheppach W, et al Effect of butyrate enemas on the colonic mucosa in distal ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology 1992; 103:51–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Konsoula Z, Barile FA. Epigenetic histone acetylation and deacetylation mechanisms in experimental models of neurodegenerative disorders. J Pharmacol Toxicol Methods 2012; 66:215–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Acevedo N, et al Age‐associated DNA methylation changes in immune genes, histone modifiers and chromatin remodeling factors within 5 years after birth in human blood leukocytes. Clin Epigenetics 2015; 7:34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Karouzakis E, et al DNA methylation regulates the expression of CXCL12 in rheumatoid arthritis synovial fibroblasts. Genes Immun 2011; 12:643–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Yamada Y, et al Identification of hypo‐ and hypermethylated genes related to atherosclerosis by a genome‐wide analysis of DNA methylation. Int J Mol Med 2014; 33:1355–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]