Abstract

Background

Tattooing is a globally growing trend. Overall prevalence among adults in industrialized countries is around 10–20%. Given the high and increasing numbers of tattooed people worldwide, medical and public health implications emerging from tattooing trends require greater attention not only by the public, but also by medical professionals and health policy makers.

Methods

We performed a systematic review of the literature on tattoo-associated bacterial infections and bacterial contamination of tattoo inks. Furthermore, we surveyed tattoo inks sampled during an international tattoo convention in Germany to study their microbial status.

Results

Our systematic review identified 67 cases published between 1984 and 2015, mainly documenting serious bacterial infectious complications after intradermal deposition of tattoo inks. Both local skin infections (e.g. abscesses, necrotizing fasciitis) and systemic infections (e.g. endocarditis, septic shock) were reported. Published bacteriological surveys showed that opened as well as unopened tattoo ink bottles frequently contained clinically relevant levels of bacteria indicating that the manufactured tattoo product itself may be a source of infection. In our bacteriological survey, two of 39 colorants were contaminated with aerobic mesophilic bacteria.

Conclusions

Inappropriate hygiene measures in tattoo parlors and non-medical wound care are major risk factors for tattoo-related infections. In addition, facultative pathogenic bacterial species can be isolated from tattoo inks in use, which may pose a serious health risk.

Body modifications including tattoos are a globally growing trend. According to recent surveys the overall prevalence of tattoos among adults in industrialized countries is around 10–20% (1). Since there are currently no public health reporting requirements for infectious complications associated with tattooing, the actual incidence and prevalence of infections following tattooing remain largely unknown in many countries, which is why scientifically sound risk quantification is not possible.

In compliance with the International Classification of Procedures in Medicine (ICPM) tattooing represents a surgical procedure with its own Operations and Procedures (OPS) code number (5–890.0; see OPS version 2015). However, tattooing is almost never performed by medical doctors and can therefore not be epidemiologically monitored by use of medical databases.

A specific diagnosis code for diseases following non-medically indicated cosmetic surgery was introduced in Germany in 2008. However, this comprises diverse procedures such as a range of aesthetic operations, along with tattoos and piercings. Since there is currently no ICD (International Classification of Diseases) code that would explicitly and specifically associate infectious diseases with the procedure of tattooing, it proved impossible to derive a reliable estimate of infection rates from data collected by German health insurance companies. Based on published surveys, between 0.5% and 6% of the people with a tattoo experienced infectious complications after being tattooed (2– 6).

Considering the increasing numbers of tattooed people, tattooing may thus represent a significant public health risk (7, 8). Therefore, physicians should be aware of atypical clinical presentations of tattoo-related infections that may lead to rare but severe adverse outcomes. Tattooing results in traumatization of the skin that may facilitate microbial pathogens to pass the epidermal barrier causing local skin infections. In most cases such mild-to-moderate superficial skin infections remain unreported since they are self-limiting or easily treated with proper aftercare, local disinfection measures and/or antibiotic therapy. However, as tattoo needles punch through the epidermis, thereby coming into contact with blood and lymph vessels in the dermal layer, bacteria may cause systemic infections by entering the blood stream. The severity of infection depends on the virulence of the pathogen, the immune status of the person being tattooed and underlying diseases.

To assess hazards and disease outcomes related to bacterial infections as a consequence of tattooing, a systematic review of the literature and bacteriological investigation of inks was performed.

Methods

Literature survey

We conducted an electronic literature search in MEDLINE (PubMed), Scopus, Web of Science, BIOSIS Previews, EMBASE and Google Scholar for eligible studies addressing

bacterial infections, not related to mycobacteria, associated with a recent tattoo, and

tattoo inks contaminated with bacteria other than mycobacteria.

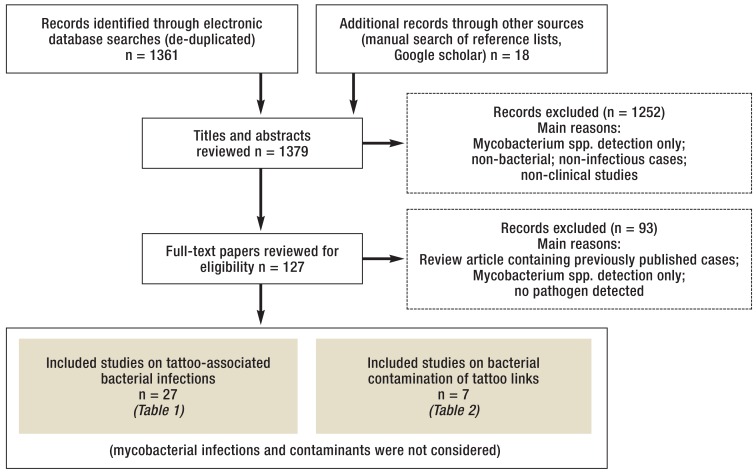

A flow chart of the selection process is presented in the Figure

Literature search: Clinical studies as well as case reports on bacterial infections following tattooing and microbiological studies on the bacterial contamination of tattoo ink were included.

eBox 1 for a detailed description of the methodology).

eBOX 1. Literature survey.

An electronic literature search was performed in MEDLINE (PubMed), Scopus, Web of Science, BIOSIS Previews, EMBASE and Google Scholar for eligible studies addressing

bacterial infections associated with a recent tattoo, and

tattoo inks contaminated with bacteria other than mycobacteria.

Mycobacterial infections were excluded from the search. Search terms used were “tattoo*” combined with “bacteria”, “bacterial” or “microbial”.

Searches were performed on all records available up to February 11, 2016 without language restrictions taking into account the PRISMA guidelines (e15). No review protocol was used. In addition, we hand-searched bibliography lists of selected full papers for potentially missed articles and added them to our database. Duplicate records were discarded. Titles and abstracts of all records in our database were screened to ensure the selection criteria have been met. Records on mycobacteria, non-bacterial infections, non-infectious cases associated with tattoos or non-clinical studies were excluded.

Two scientists independently screened and evaluated the references. Data was extracted on patient demographics, incubation period, clinical diagnoses and outcomes, bacterial pathogens identified, and likely cause of infection or transmission route. Relevant data were used to carry out basic statistical analyses.

The quality of the records was not assessed because most of the identified studies were case reports. Generally, case reports and case series provide weak evidence of causality, but contain useful information regarding, e.g., rare manifestations or unexpected risks, and therefore allow to generate hypotheses (e16). Consequently, our study should be considered as exploratory.

Our review might be somewhat biased as severe hospitalized cases were predominantly described in the literature, most cases were reported from a few geographic regions (primarily North America and Europe), and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus (S.) aureus (MRSA) cases were mostly reported in publications from the United States. Although no language restriction was used, cases from the so-called gray literature or published in non-English language might have been missed.

Microbiological analysis

A total of 39 samples of tattoo inks originating from opened vials that were randomly collected by local health inspectors during the 10th International Tattoo Convention in Reutlingen, Germany, were analyzed. Enumeration and detection of aerobic mesophilic bacteria (i.e., aerobic bacteria that grow best at moderate temperatures) were performed in accordance with validated guidelines for the microbiological analysis of cosmetic products (EN ISO 21149:2009), as was the detection of specified and non-specified microorganisms including Escherichia (E.) coli, Pseudomonas (P.) aeruginosa, and Staphylococcus (S.) aureus (EN ISO 18415:2011). Isolates from contaminated samples were sub-cultured for further identification by Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization Time-of-Flight Mass Spectrometry (MALDI-ToF MS) and 16S rRNA gene sequencing.

Results

Tattoo-related infections

Our initial literature search yielded 1379 records, of which 1345 were excluded, mainly because they described non-infectious cases, non-bacterial infections, non-clinical studies or were summary reports of already considered cases (Figure). Two systematic reviews of tattoo-associated skin infections caused by non-tuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) were published quite recently (9, 10). Since our survey revealed only four additional reports describing six new cases (e1– e4), mycobacterial infections were excluded from our data analysis and interpretation because of a lack of novelty.

We identified 67 cases of non-mycobacterial infections reported in 27 publications published between 1984 and 2015 (11– 37), mainly documenting serious bacterial infectious complications after intradermal deposition of tattoo inks (Table 1, eTable). Since the CDC case series (16) presented only aggregated data, those 34 cases were omitted from the statistical analysis and discussed separately. Most patients were male (75%). The mean age was 28 years (range: 0–48 years). Most cases were reported from the United States (n=12), Europe (n=11) and New Zealand (n=5). The number of reports increased over time and 9 out of 11 cases from Europe and 10 out of 13 cases from North America were published between 2011 and 2015, which might indicate an increased awareness. S. aureus was reported as an etiological agent in 81% of the cases. Long-term antibiotic therapy with a mean duration of six weeks (range 1–15 weeks) was the treatment of choice in 21 reports, which provided this type of information. Two patients died due to complications related to their infections (11, 15).

Table 1. Local skin infections, systemic complications and etiological agents extracted from reported cases of tattoo-related, non-mycobacterial infections*.

| Local skin infections (reference) | Bacteria isolated from wound swab or abscess drainage (reference) |

|

Systemic complications (reference) |

Bacteria isolated from blood, tissue, wound swab and/or abscess drainage (reference) |

*see the eTable for more detailed information; MSSA, methicillin-sensitive S. aureus; MRSA, methicillin-resistant S. aureus

eTable. Reported cases of tattoo-related, non-mycobacterial infections.

|

Manifestations at primary infection site (tattoo) |

Secondary infection complications, (concomitant pre-existing conditions supporting bacterial infections) |

Number of cases*, patient’s country of origin |

Age (years), sex (m/f) |

Organisms identified (Source) |

Incubation period (days) |

Likely cause of infection, transmission route |

Outcome | Reference |

| Local skin infections | ||||||||

| Skin and soft tissue infection |

1, United States of America |

45, m | MRSA (WS) |

NA | Improper sanitary conditions: sharing needles and tattoo paraphernalia at a correctional facility |

NA | Stemper et al. (2006) (17) |

|

| Abscess | 3, United States of America |

18, f | MRSA (WS, abscess drainage) |

NA | Unhygienic conditions |

Fully recovered after 8 weeks |

Coulson (2012) (22) |

|

| Abscess, tissue necrosis |

(drug detoxification) | 22, f | MRSA (WS, abscess drainage) |

NA | NA | Fully recovered after 6 weeks |

||

| Multiple abscesses, cellulitis |

37, m | MSSA, S. pyogenes (WS, abscess drainage) |

7 | Potential ink contamination |

Hospitalization, fully recovered after 4 weeks |

|||

| Cutaneous diphtheria, cellulitis |

1, New Zealand | Adult, m | Toxigenic Corynebacterium diphtheriae var. gravis, S. aureus (WS) |

within days | Traditional Samoan tattooing |

Hospitalization, fully recovered within 1 week |

Sears et al. (2012) (23), McGouran et al. (2012) (24) |

|

| Abscess | 1, Germany | 31, m | MRSA (WS, abscess drainage) |

NA | NA | NA | Wollina (2012) (25) |

|

| Abscesses | 4, France | 29–43, m | MSSA (WS) | <21 | Tattooing or body shaving with mechanical razors |

NA | Bourigault et al. (2014) (30) |

|

| Abscess | 1, Spain | 32, m | S. marcescens (WS, abscess drainage) |

30 | NA | Hospitalization, fully recovered after 15 weeks |

Diranzo-Garcia et al. (2015) (34) |

|

| Erythema, pustules | 1, Italy | 31, f | P. aeruginosa (WS) |

2 | Possible use of non-sterile tattooing technique or contamination of the ink |

Recovery after 2 weeks |

Maloberti et al. (2015) (36) |

|

| Erythema | Lyell's syndrome (staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome; SSSS) |

1, Denmark | 48, m | S. aureus (WS) | NA | Home kit tattoo ink imported via the internet, probable phototoxic reaction to the ink followed by a break in the skin barrier due to itching resulting in bacterial infection |

Hospitalization, recovery after 1 week (followed by a 6 months treatment against allergic contact dermatitis reaction) |

Mikkelsen et al. (2015) (37) |

| Systemic complications | ||||||||

| Purulent wound infection |

Septicemia | 1, Nigeria | Newborn, NA | P. aeruginosa (BC, WS, pus) |

1 | Tribal tattooing under unhygienic conditions |

Hospitalization, death |

Mathur and Sahoo (1984) (11) |

| Cellulitis and fasciitis, subcutaneous abscess |

Polymicrobial septicemia |

1, Australia | 25, m | P. aeruginosa, S. pyogenes (BC, WS), K. oxytoca, MSSA (WS), Bacteroides fragilis (abscess drainage) |

7 | Traditional Samoan tattooing under unhygienic conditions |

Hospitalization, fully recovered after 9 weeks |

Korman et al. (1997) (12) |

| Pustular lesions | Acute spinal epidural abscess with lower limb weakness |

1, United States of America |

25, f | MSSA (WS, abscess drainage) |

7 | NA | Hospitalization, fully recovered after 8 weeks |

Chowfin et al. (1999) (13) |

| Endocarditis (bicuspid aortic valve) |

1, United Kingdom | 28, m | S. aureus (BC, explanted aortic valve) |

7 | NA | Hospitalization, fully recovered after 16 weeks |

Satchithananda et al. (2001) (14) |

|

| Cellulitis | Septic shock | 2, New Zealand | 45, m | S. aureus, S. pyogenes, P. aeruginosa (WS) |

2 | Traditional Samoan tattooing under unhygienic conditions |

Hospitalization, fully recovered after 4 weeks |

Porter et al. (2005) (15) |

| Necrotizing fasciitis |

Septic shock, abdominal compartment syndrome, acute heart failure |

29, m | S. pyogenes, S. aureus (WS), Corynebacterium spp., K. oxytoca (soft tissue debridement) |

2 | Traditional Samoan tattooing, use of non-sterile equipment, highly contaminated ink and yellow pigment (aerobic spore-forming bacilli) |

Hospitalization, death | ||

| Cellulitis, pustules, abscesses |

Bacteremia (4/34 cases) (no underlying diseases except for one patient with hepatitis C) |

34, United States of America |

15–42, 73% m | MRSA (WS) |

4–22 | Use of non-sterile equipment and suboptimal infection-control practices (unlicensed tattooists) |

Hospitalization (4/34 cases) |

CDC (2006) (16) |

| Local skin infection | Endocarditis (bicuspid aortic valve) |

1, United Kingdom | 44, m | S. lugdunensis (BC) |

NA | NA | Hospitalization, full recovery |

Tse et al. (2009) (18) |

| Erythema | Xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis |

1, United States of America | 16, m | MRSA (renal tissue) |

<21 | Unsterile tattooing |

Hospitalization, fully recovered after 4 weeks |

Chalmers et al. (2010) (20) |

| Endocarditis | 1, Argentina | 34, f | Moraxella lacunata (BC) |

4 | NA | Hospitalization, fully recovered after 8 weeks |

Callejo et al. (2010) (19) |

|

| Extensive cellulitis | Septic shock leading to acute renal failure |

2, New Zealand | 23, m | S. aureus and group C streptococci (WS) |

3 | Traditional Samoan tattooing under unhygienic conditions |

Hospitalization, full recovery after 6 weeks but ongoing wound management required |

McLean and D’Souza (2011) (21) |

| Severe cellulitis, necrotizing fasciitis |

Septic shock leading to multi-organ failure |

25, m | S. pyogenes, P. aeruginosa (WS) |

2 | Traditional Samoan tattooing under unhygienic conditions |

Hospitalization, full recovery after 6 weeks but ongoing wound management required |

||

| Deep skin infection, multiple abscesses |

Sepsis | 1, United States of America |

46, m | Group A streptococci and MSSA (BC) |

<5 | Traditional Samoan tattooing |

Hospitalization, fully recovered after 6 weeks |

Elegino-Steffens et al. (2013) (27) |

| Tropical pyomyositis | 1, Cuba | 19, f | S. aureus (WS) |

15 | Non-professional tattooing under unhygienic conditions |

Complete recovery after 4 weeks |

Báez Sarría et al. (2013) (26) |

|

| Superficial skin infection |

Iliopsoas abscess | 2, United States of America |

Adult, m | MRSA | NA | Sharing the same ink and equipment with his wife | Hospitalization | Gulati et al. (2014) (31) |

| Iliopsoas abscess (intravenous drug abuse, hepatitis C) |

48, f | MRSA (BC) |

NA | Non-professional home-made tattoo under unhygienic conditions or potential ink contamination |

Hospitalization, fully recovered |

|||

| Endocarditis (myxoid degeneration of the mitral valve), septic emboli (knee, brain, lung) |

1, United States of America |

23, m | MSSA (BC) |

1–2 | NA | Hospitalization, fully recovered after 6 weeks |

Akkus et al. (2014) (28) |

|

| Abscess | Peripheral septic thrombophlebitis; necrotizing pneumonia (intravenous drug abuse in medical history) |

1, United States of America |

28, m | MRSA (WS, abscess drainage, BC, sputum) |

7 | NA | Hospitalization, fully recovered after 6 weeks |

Rabbani and Sharma(2014) (33) |

| Sepsis, septic emboli (muscle and joints) | 1, United States of America |

18, m | Haemophilus influenzae (BC) |

14 | NA | Hospitalization, fully recovered after 2 weeks |

Kaldas et al. (2014) (29) |

|

| Sepsis, endocarditis, pulmonary emboli (open valvotomy for congenital aortic stenosis at the age of 18 months followed by Ross procedure) |

1, United Kingdom | 20, m | MSSA (BC, excised pulmonary homograft tissue) |

28 | Tattooing under unhygienic conditions |

Hospitalization, recovered after 8 weeks |

Orton et al. (2014) (32) |

|

| Erythematous rash and multiple papules |

Toxic shock syndrome |

1, South Korea | 26, m | MSSA (WS) |

3 | NA | Hospitalization, fully recovered after 2–3 weeks |

Jeong et al. (2015) (35) |

Bacteriological contamination of tattoo inks

Since only seven reports on contaminated tattoo inks have been published so far (Table 2) we officially collected 39 tattoo inks in use during an international tattoo convention in Germany, 2014, and determined their microbial status to specify the risk of infection associated with the subepidermal application of ink deposits. A total of 19 inks (49%) were claimed to be sterile/sterilized on the label. Fifteen (38%) contained benzisothiazolinone as a preservative, three additionally contained methylisothiazolinone and phenoxyethanol. Twenty-three products used alcohol as a solvent, in most cases isopropyl alcohol. Among the 39 colorants investigated, two (5%) were contaminated with aerobic mesophilic bacteria (˜107 bacteria per gram of ink). Both products were free of preservatives. In one sample various Pseudomonas species (P. pseudoalcaligenes, P. stutzeri, P. fluorescens group) and Delftia spp. (D. lacustris/tsuruhatensis group) were detected. The other sample was contaminated with P. aeruginosa, Stenotrophomonas maltophilia, Agrobacterium tumefaciens/Rhizobium sp. and bacteria belonging to the Staphylococcus warneri/pasteuri group. The bacterial genera identified were largely in line with those described in the literature (Table 2).

Table 2. Bacterial contamination of tattoo inks.

| Reference |

Total number of tested inks (opened/ unopened) |

Number (percentage) of contaminated samples |

Bacterial load [cfu/g] (samples) |

Organisms identified | |

| Total |

Opened, Unopened |

||||

| Reus and van Buuren (2001) (e5) |

63 (32/31) | 11 (18) | 8(25), 3 (10) |

104–105 (1), > 105 (7) 102 –104 (3) |

Pseudomonas aeruginosa, P. putida, P. fluorescens |

| Charnock (2004) (e6) |

12 (10/2) | 7 (58) | 6 (60), 1 (50) |

102–103 (2), 106–109 (4) 102 –103 (1) |

Gram-positive, aerobic rods, Citrobacter freundii, Achromobacter xylosoxidans, A. denitrificans, Corynebacterium sp., Brevundimonas diminuta, P. aeruginosa, Stenotrophomonas maltophilia, Leuconostoc spp., Methylobacterium mesophilicum |

| Droß and Mildau (2007) (e7) |

245 (mainly opened) |

26 (11) | 102–107 (26) | Pseudomonas spp., Citrobacter spp., aerobic spore-forming bacteria, Ralstonia pickettii, coliform bacteria | |

| Baumgartner and Gautsch (2011) (e8) |

145 (106/39) | 41 (28) | 27 (26), 14 (36) |

< 101 (5), 101–103 (18), 103–108 (4) < 101 (7), 101 –103 (7) |

Enterococcus spp., Micrococcus spp., Staphylococcus spp., Brevundimonas vesicularis, P. fluorescens, S. maltophilia, Bacillus spp., Geobacillus spp., Paenibacillus spp., Virgibacillus pantothenticus, Brevibacillus laterosporus |

| Kluger et al. (2011) (e9) |

16 (16/0) | 0 (0) | – | – | – |

| Høgsberg et al. (2013) (e10) |

64 (6/58) | 7 (11) | 1 (17), 6 (10) |

102 (1) 102 –103 (6) |

Streptococcus spp., Acinetobacter sp., Bacillus sp., Staphylococcus sp., Aeromonas sobria, Acidovorax, Pseudomonas sp., Dietzia maris, Blastomonas sp., Enterococcus faecium |

| Bonadonna et al. (2014) (e11) |

34 (27/7) | 29 (85) | 23 (85), 6 (86) |

< 101 (11), 101–103 (12) < 101 (4), < 102 (2) |

Bacillus spp., Staphylococcus spp., Enterobacter intermedius, Cronobacter sakazakii, Sphingomonas paucimobilis |

cfu, colony forming unit

Discussion

Infectious complications from tattoos include superficial infections such as impetigo, deep bacterial skin infections presenting as erysipelas or cellulitis and systemic infections which may lead, in very rare cases, to life-threatening complications due to endocarditis, septic shock, and multi-organ failure (38). Acute pyogenic skin infections or bacteremia usually occur within a few days after placement of the tattoo and predominantly involve methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) or methicillin-sensitive S. aureus (MSSA), Streptococcus spp., and Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

Nontuberculous mycobacterial (NTM) skin infections

In recent years, a considerable number of reports describing cases of nontuberculous mycobacterial infections following tattooings have been published (9, 10). Conaglen et al. identified a total of 25 reports describing 71 confirmed and 71 probable tattoo-related infections with NTM such as M. chelonae, M. haemophilum, and M. abscessus (10). NTM infections typically occurred in healthy individuals within weeks to months after tattooing and manifested as localized cutaneous infections presenting as papules, pustules and nodules at the site of the tattoo. Often, lesions were restricted to a single colored part of the tattoo. The most frequently postulated route of transmission was the dilution of tattoo ink with non-sterile water. With several months of antibiotic treatment (either clarithromycin alone or in combination with quinolones) outcomes of these long-lasting infections tended to be good.

Other bacterial infectious complications

Seven cases followed traditional Samoan tattooing in previously healthy, young men from New Zealand, Australia and the USA (12, 15, 21, 23, 24, 27). Typically, patients initially developed erysipelas, multiple subcutaneous abscesses and necrotizing soft tissue infections localized in the tattooed skin area which led to severe polymicrobial septicemia, septic shock and life-threatening organ failure. In one of these cases, cutaneous diphtheria caused by a toxigenic strain of Corynebacterium diphtheriae (var. gravis) has been reported (23, 24). However, it could well be that S. aureus was the primary pathogen in this case.

One patient died of acute heart failure as a consequence of septic shock following a ritual Samoan tattooing (15). In this case, the used ink and a natural yellow pigment (turmeric) showed high contamination with Gram-positive bacteria. Most patients recovered but required prolonged hospitalization with intravenous antibiotic treatment. Inadequate cleaning and sterilization of tattoo equipment as well as inappropriate infection control measures and the more invasive procedures were supposed to be the main risk factors of traditional tattooing.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) have documented a series of 34 cases of MRSA infections among recipients of tattoos from 13 unlicensed tattooists in the USA in 2004–2005 (16). The majority of patients were white males without underlying diseases or risk factors. Most infections were mild to moderate (erysipelas, bacterial pustules, and abscesses) and wound healing could be improved with surgical drainage and/or oral antibiotics. Four patients developed bacteremia and required hospitalization for intravenous vancomycin treatment. Suboptimal infection control procedures of unlicensed tattooists were identified as the major risk factor.

Similar outcomes and risk factors for three cases of tattoo-associated S. aureus infections were described in a recent report (22). In at least one of the cases ink contamination may have caused the infection, since the distribution of the infectious lesions was linked to a single color. Two outbreaks of community-associated MRSA (CA-MRSA) and Panton-Valentine Leukocidin (PVL)-positive MSSA skin and soft tissue infections at a correctional facility in the USA and in a prison in France have been attributed to unhygienic tattooing conditions (17, 30).

Rare complications of tattoo-related infections caused by S. aureus are the toxic shock syndrome (TSS) caused by toxigenic strains of S. aureus (35) and the staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome (SSSS) (37).

Five cases of presumably tattoo-related infective endocarditis were found in the literature. Prior heart disease was noticed as a risk factor in four of them. Etiologic agents were human commensals such as S. aureus (14, 28), S. lugdunensis (18), and Moraxella lacunata (19). Typically, symptoms started within a week after tattoo placement with recurring episodes of high fever and dyspnea.

Tattoos are generally accepted to be an initial entrance door for bacteria into the human body, but the clinical pictures of possible tattoo-related infectious diseases can be more heterogeneous and the etiologic agents more diverse than actually expected (Table 1, eTable).

Contamination of tattoo inks as a potential source of infection

Although most licensed tattoo parlors have implemented hygiene measures, bacterial infections emerge. Inappropriate infection control is often blamed to be responsible for tattoo-related infections. Pathogens may originate from surfaces in the tattoo studio environment and from inadequately sterilized instruments or other equipment, or from the commensal or transient skin flora of the tattooed person and the tattooist alike. Tattoo wounds may also become infected during the healing process due to inadequate wound care or personal hygiene. In addition, the applied colorant itself might have gotten extrinsically contaminated during usage or intrinsically during production. Published bacteriological surveys (e5– e11) show that opened (used) as well as unopened (unused) tattoo ink bottles frequently contain considerable numbers of bacteria indicating that the manufactured tattoo product itself may be a risk factor in tattoo-related infections (Table 2). Contamination rates beyond 10% are not unusual for tattoo inks. In general, lower bacterial counts of bacilli or other spore-forming bacteria are found in unopened ink containers (102–103 colony forming units per gram ink [cfu/g]), whereas high bacterial loads are common for opened bottles (103–109 cfu/g). From opened bottles, Gram-negative aerobic bacteria such as P. aeruginosa were isolated in high numbers (e6). These ubiquitous germs (?) are able to colonize virtually all environments including soil, tap and marine waters, as well as the human skin. Yet Gram-positive bacteria such as Staphylococcus spp. that are part of the commensal flora of the human skin can also be found in opened as well as unopened bottles (e8). Most of the bacterial contaminants were not highly virulent though, but instead opportunistic pathogens (e5– e11).

Many of the bacterial genera that have been associated with tattoo-related infections are in accordance with those found in bacteriological surveys of opened tattoo ink bottles (see Tables 1 and 2, eTable). Bottling of ink solutions from stock bottles to smaller non-sterile cups recurrently contaminated during the placement of a tattoo represents only one but certainly a highly likely source of contamination, in particular, when the top of the stock bottle repeatedly gets into contact with the cup. Another common source is the mixing of colors and dilution of inks by the tattoo artist under non-sterile conditions or with non-sterile diluents (e.g., tap water or “distilled”, but not germ-free water). As a consequence, bacteria may readily reach infective doses (>103 to 108 cfu/g, see Table 2) in tattoo products, especially when they are inadequately preserved (e6, e8, e10). Hence, tattoo inks may be underrated as a potential source of bacterial infection and harmonized legal requirements for tattooing services as well as mandatory quality measures are needed not only for tattoo parlors but also for producers of tattoo inks (see eBox 2 on regulatory aspects).

eBOX 2. Regulatory aspects.

Because there are currently no harmonized legal requirements for tattooing services, qualification standards of tattoo artists regarding hygiene, infection control and prevention greatly vary (2). Generally tattoo inks are regarded as cosmetic products and the colorants and ingredients do not require explicit governmental approval prior to deposition into the skin (2).

The composition of tattoo inks is highly variable and often unknown. Since manufacturers usually refuse to disclose the individual ingredients of their ink formulas, these may contain numerous hazardous compounds including inorganic metal salts and additives originating from plants or animals, the latter of which may be sources of bacterial contamination. Still, companies producing and distributing tattoo inks have the legal responsibility to ensure the safety of their products, but legislative bodies do not provide specifications for product sterility requirements and do not set specific standards for sterilization measures, sterility testing or preservation.

Some manufacturers claim their inks to be “sterilized” on the label, but they are not obliged to report their sterility testing results to the legal authorities.

In 2003 and 2008, two resolutions have been published by the Council of Europe regarding the safety of tattooing, which recommended sterility of products used for tattooing and permanent make-up (PMU) (e12, e13). However, they are not legally binding to European member states and even differ in their recommendations about preservation and container usage.

While ResAP(2003)2 suggests that tattoo and PMU products may only be permitted if they are sterile and supplied in single-use containers which maintain sterility until application in the absence of chemical preservatives, ResAP(2008)1 states that such preservatives (e.g., isothiazolinones or formaldehyde) should be used to ensure preservation of the product after opening. Further, according to the newer resolution multi-use containers could be used if their design ensures that the contents will not be contaminated during the lifetime of the bottle.

In 2014, the German Institute for Standardization (Deutsches Institut für Normung, DIN) proposed a new project to the European CEN Technical Board to compile European standards establishing requirements related to tattooing. The proposal was accepted as CEN/TC 435 “Tattooing services” comprising hygienic performance of tattooing, including knowledge and skills, infection control, vaccination, suitable facilities as well as requirements for cleaning, disinfection and sterilization, management of waste, necessary documentation and aftercare information (e14). However, microbiological quality criteria of tattoo inks are not covered, as this may be a potential future mandate on tattoo products in the framework of the General Product Safety Directive (2001/95/EC).

*Confirmed by pathogen detection

Abbreviations: f, female; m, male; MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; MSSA, methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus; NA, data not available; WS, wound swab; BC, blood culture.

K., Klebsiella; P., Pseudomonas; S., Staphylococcus in S. aureus and S. lugdunensis; S., Serratia in S. marcescens; S., Streptococcus in S. pyogenes

Conclusions

With respect to the considerable popularity of tattoos and yet insufficient regulation of hygiene measures in both the production of tattoo inks and the process of tattooing, infection risks associated to this kind of body art should be recognized as a potential public health concern (2, 3, 8, 38). Since consumers may not be aware of infection risks from tattooing and tattoo artists complying with hygiene guidelines cannot easily be identified, statutory rules are urgently needed for consumer protection. Physicians should be aware of the tattoo-related complications, educate patients about potential health risks and provide advice to those with predisposing conditions regarding the need of preventive measures such as specific follow-up care. If indicated patients shall be asked to refrain from tattoos which may help to prevent sequelae.

Key Messages.

In recent years, skin infections associated with tattoos are more frequently recognized as public health concern.

Serious bacterial infectious complications following tattooing have occasionally been documented in the literature.

Inappropriate hygiene measures and pre-existing conditions are among the major risk factors, and tattoo inks are likely being underrated as a potential source of bacterial infection.

Mandatory quality measures for tattoo ink producers, tattoo parlors, and the tattoo artists are urgently recommended to protect consumers’ health.

Physicians should adequately inform their patients about potential hazards and clinical complications after tattooing.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

Prof. Al Dahouk has written a medical expertise report regarding this paper's subject matter.

All other authors declare that no conflict of interest exists.

Acknowledgments

This study has been financially supported by intramural grants of the German Federal Institute for Risk Assessment (BfR).

References

- 1.Kluger N. Epidemiology of tattoos in industrialized countries. Curr Probl Dermatol. 2015;48:6–20. doi: 10.1159/000369175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Laux P, Tralau T, Tentschert J, et al. A medical-toxicological view of tattooing. Lancet. 2016;387:395–402. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60215-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Klügl I, Hiller KA, Landthaler M, Bäumler W. Incidence of health problems associated with tattooed skin: a nation-wide survey in German-speaking countries. Dermatology. 2010;221:43–50. doi: 10.1159/000292627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kazandjieva J, Tsankov N. Tattoos: dermatological complications. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:375–382. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2007.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kluger N. Self-reported tattoo reactions in a cohort of 448 French tattooists. Int J Dermatol. 2015;55:764–768. doi: 10.1111/ijd.13030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liszewski W, Kream E, Helland S, Cavigli A, Lavin BC, Murina A. The demographics and rates of tattoo complications, regret, and unsafe tattooing practices: a cross-sectional study. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41:1283–1289. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000000500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schmidt A. Hygiene standards for tattooists. Curr Probl Dermatol. 2015;48:223–227. doi: 10.1159/000369840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wenzel SM, Rittmann I, Landthaler M, Bäumler W. Adverse reactions after tattooing: review of the literature and comparison to results of a survey. Dermatology. 2013;226:138–147. doi: 10.1159/000346943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mudedla S, Avendano EE, Raman G. Non-tuberculous mycobacterium skin infections after tattooing in healthy individuals: a systematic review of case reports. Dermatol Online J. 2015;21(6.) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Conaglen PD, Laurenson IF, Sergeant A, Thorn SN, Rayner A, Stevenson J. Systematic review of tattoo-associated skin infection with rapidly growing mycobacteria and public health investigation of a cluster in Scotland, 2010. Eurosurveillance. 2013 doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.es2013.18.32.20553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mathur DR, Sahoo A. Pseudomonas septicemia following tribal tatoo marks. Trop Geogr Med. 1984;36:301–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Korman TM, Grayson ML, Turnidge JD. Polymicrobial septicaemia with Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Streptococcus pyogenes following traditional tattooing. J Infect. 1997;35 doi: 10.1016/s0163-4453(97)92172-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chowfin A, Potti A, Paul A, Carson P. Spinal epidural abscess after tattooing. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;29:225–226. doi: 10.1086/520174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Satchithananda DK, Walsh J, Schofield PM. Bacterial endocarditis following repeated tattooing. Heart. 2001;85:11–12. doi: 10.1136/heart.85.1.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Porter CJW, Simcock JW, MacKinnon CA. Necrotising fasciitis and cellulitis after traditional Samoan tattooing: case reports. J Infect. 2005;50:149–152. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2003.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus skin infections among tattoo recipients— Ohio, Kentucky, and Vermont, 2004-2005. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2006;55:677–679. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stemper ME, Brady JM, Qutaishat SS, et al. Shift in Staphylococcus aureus clone linked to an infected tattoo. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12:1444–1446. doi: 10.3201/eid1209.051634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tse D, Khan S, Clarke S. Bacterial endocarditis complicating body art. Int J Cardiol. 2009;133:e28–e29. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2007.08.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Callejo RM, Nacinovich F, Prieto MA, et al. Moraxella lacunata infective endocarditis after tattooing as confirmed by 16S rRNA gene sequencing from heart valve tissue. Clin Microbiol Newsl. 2010;32:6–7. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chalmers D, Marietti S, Kim C. Xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis in an adolescent. Urology. 2010;76:1472–1474. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2010.03.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McLean M, D’Souza A. Life-threatening cellulitis after traditional Samoan tattooing. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2011;35:27–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-6405.2010.00658.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Coulson A. Illegal tattoos complicated by Staphylococcus infections: a North Carolina wound care and medical center experience. Wounds. 2012;24:323–326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sears A, McLean M, Hingston D, Eddie B, Short P, Jones M. Cases of cutaneous diphtheria in New Zealand: implications for surveillance and management. N Z Med J. 2012;125:64–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McGouran DC, Ng SK, Jones MR, Hingston D. A case of cutaneous diphtheria in New Zealand. N Z Med J. 2012;125:93–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wollina U. Severe adverse events related to tattooing: a retrospective analysis of 11 years. Indian J Dermatol. 2012;57:439–443. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.103062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Báez Sarría F, Rodríguez Collar TL, Santos VF. Tropical pyomyositis as a complication of a tattoo. Rev Cubana Med Mil. 2013;42:417–422. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Elegino-Steffens DU, Layman C, Bacomo F, Hsue G. A case of severe septicemia following traditional Samoan tattooing. Hawaii J Med Public Health. 2013;72:5–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Akkus NI, Mina GS, Fereidoon S, Rajpal S. Tattooing complicated by multivalvular bacterial endocarditis. Herz. 2014;39:349–351. doi: 10.1007/s00059-013-3810-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kaldas V, Katta P, Trifinova I, Marino C, Sitnitskaya Y, Khanna S. Rare tattoo complication: Haemophilus influenzae sepsis in a teenager. Consultant. 2014;54:289–291. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bourigault C, Corvec S, Brulet V, et al. Outbreak of skin infections due to panton-valentine leukocidin-positive methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus in a French prison in 2010-2011. PLoS Curr. 2014 doi: 10.1371/currents.outbreaks.e4df88f057fc49e2560a235e0f8f9fea. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gulati S, Jain A, Sattari M. Tattooing: a potential novel risk factor for iliopsoas abscess. World J Clin Cases. 2014;2:459–462. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v2.i9.459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Orton CM, Norrington K, Alam H, Alonso-Gonzalez R, Gatzoulis M. The danger of wearing your heart on your sleeve. Int J Cardiol. 2014;175:e6–e7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.04.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rabbani S, Sharma TR. MRSA necrotizing pneumonia and peripheral septic thrombophlebitis. Consultant. 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Diranzo García J, Villodre Jiménez J, Zarzuela Sánchez V, Castillo Ruiperez L, Bru Pomer A. Skin abscess due to Serratia marcescens in an immunocompetent patient after receiving a tattoo. Case Rep Infect Dis 2015; 2015 doi: 10.1155/2015/626917. 626917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jeong KY, Kim KS, Suh GJ, Kwon WY. Toxic shock syndrome following tattooing. Korean J Crit Care Med. 2015;30:184–190. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maloberti A, Betelli M, Perego MR, Foresti S, Scarabelli G, Grassi G. A case of Pseudomonas aeruginosa commercial tattoo infection. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2015 doi: 10.23736/S0392-0488.17.04937-9. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mikkelsen CS, Holmgren HR, Arvesen KB, Jarjis RD, Gunnarsson GL. Severe scratcher-reaction: an unknown health hazard? Dermatology Reports. 2015;7:9–11. doi: 10.4081/dr.2015.5816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Serup J, Hutton Carlsen K, Sepehri M. Tattoo complaints and complications: diagnosis and clinical spectrum. Curr Probl Dermatol: S. Karger AG. 2015:48–60. doi: 10.1159/000369645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E1.Frew JW, Nguyen RT. Tattoo-associated mycobacterial infections: an emerging public health issue. Med J Aust. 2015;203 doi: 10.5694/mja15.00098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E2.Philips RC, Hunter-Ellul LA, Martin JE, Wilkerson MG. Mycobacterium fortuitum infection arising in a new tattoo. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E3.Sousa PP, Cruz RC, Schettini AP, Westphal DC. Mycobacterium abscessus skin infection after tattooing—case report. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90:741–743. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20153362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E4.Danford B, Weingartner J, Patel G. Rapidly growing mycobacterial infection following tattoo. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72 [Google Scholar]

- E5.Reus H, van Buuren R. Kleurstoffen voor tatoeage en permanente make-up. Legislation report no ND COS 012. Inspectorate for Health Protection North, Ministry of Health. 2001:1–36. [Google Scholar]

- E6.Charnock C. Colourants used for tattooing contaminated with bacteria. Tatoveringsløsninger forurenset av bakterier. 2004;124:933–935. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E7.Droß A, Mildau G. Mikrobiologischer Status von Mitteln zum Tätowieren Berichte zur Lebensmittelsicherheit 200, Bundesweiter Überwachungsplan 2007. Bundesamt für Verbraucherschutz und Lebensmittelsicherheit. 2007 [Google Scholar]

- E8. Baumgartner A, Gautsch S. Hygienic-microbiological quality of tattoo- and permanent make-up colours. J Verbrauch Lebensm. 2011;6:319–325. [Google Scholar]

- E9.Kluger N, Terru D, Godreuil S. Bacteriological and fungal survey of commercial tattoo inks used in daily practice in a tattoo parlour. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:1230–1231. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2010.03788.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E10.Høgsberg T, Saunte DM, Frimodt-Møller N, Serup J. Microbial status and product labelling of 58 original tattoo inks. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:73–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2011.04359.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E11.Bonadonna L, Briancesco R, Coccia AM, et al. Valutazione delle caratteristiche microbiologiche di inchiostri per tatuaggi in confezioni integre e dopo l’apertura. Microbiologica Medica. 2014;29 [Google Scholar]

- E12.Council of Europe Resolution ResAP(2003)2 on tattoos and permanent make-up. Strasbourg, France, Council of Europe. 2003 [Google Scholar]

- E13.Council of Europe Resolution ResAP(2008)1 on requirements and criteria for the safety of tattoos and permanent make-up (superseding resolution ResAP(2003)2 on tattoos and permanent make-up) Strasbourg, France, Council of Europe. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- E14.CEN European committee for standardization CEN/TC 435—Project committee tattooing services Safe practice and hygiene requirements. https://standards.cen.eu/ (last accessed 15 August 2016). [Google Scholar]

- E15.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. Ital J Public Health. 2009;6:354–391. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E16.Vandenbroucke JP. In defense of case reports and case series. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134:330–334. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-134-4-200102200-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]