Abstract

Introduction

Group prenatal care results in improved birth outcomes in randomized controlled trials, and better attendance at group prenatal care visits is associated with stronger clinical effects. This paper’s objectives are to identify determinants of group prenatal care attendance, and to examine the association between proportion of prenatal care received in a group context and satisfaction with care.

Methods

We conducted a secondary data analysis of pregnant adolescents (n=547) receiving group prenatal care in New York City (2008–2012). Multivariable linear regression models were used to test associations between patient characteristics and percent of group care sessions attended, and between the proportion of prenatal care visits that occurred in a group context and care satisfaction.

Results

Sixty-seven groups were established. Group sizes ranged from 3 to 15 women (mean=8.16, SD=3.08); 87% of groups enrolled at least five women. Women enrolled in group prenatal care supplemented group sessions with individual care visits. However, the percent of women who attended each group session was relatively consistent, ranging from 56% to 63%. Being born outside of the United States was significantly associated with higher group session attendance rates (B[SE]=11.46 [3.46], p=0.001), and women who received a higher proportion of care in groups reported higher levels of care satisfaction (B[SE]=0.11 [0.02], p<0.001).

Discussion

Future research should explore alternative implementation structures to improve pregnant women’s ability to receive as much prenatal care as possible in a group setting, as well as value-based reimbursement models and other incentives to encourage more widespread adoption of group prenatal care.

Keywords: Group prenatal care, CenteringPregnancy, Implementation, Adherence, Translational study

INTRODUCTION

Group prenatal care results in perinatal and postpartum outcomes as good as or better than traditional individual care, with implications for maternal and child health and healthcare costs (Catling et al. 2015; Ickovics et al. 2007; Ickovics et al 2015; Picklesimer et al. 2012). A randomized controlled trial comparing CenteringPregnancy and CenteringPregnancy Plus (CenteringPregnancy bundled with an integrated sexual risk reduction intervention) group prenatal care to individual care in Atlanta and New Haven documented a 33% reduction in preterm delivery among young women randomized to group care and 51% reduction in rapid repeat pregnancy among those who received the sexual risk reduction intervention within a group (Ickovics et al. 2007; Kershaw et al. 2009).

Subsequently, a 14-site cluster randomized controlled trial of CenteringPregnancy Plus compared to usual care in New York City, documented a 34% risk reduction in babies born small for gestational age (Ickovics et al. 2016) and healthier weight trajectories (less weight gained during pregnancy and more weight lost postpartum) for young women at clinical sites delivering group care (Magriples et al. 2015). These positive effects of group prenatal care were observed despite modest adherence: women at clinical sites randomized to group care attended only about one-half of recommended group visits, and 22% never attended any group care sessions at all (Ickovics et al. 2016). “As treated” analyses documented that a greater number of group prenatal care visits was associated with better outcomes such as lower risk of preterm birth and low birthweight as well as fewer days in the neonatal intensive care unit and lower risk of rapid repeat pregnancy (Ickovics et al, 2016).

Although significant cost savings may be achieved for patients and payors through improved clinical outcomes, the expense of running group prenatal care is an important consideration for healthcare providers, who take on the logistic, financial and labor burdens of transforming their care systems. According to a financial model developed by Rowley and colleagues (2016), cost neutrality for group prenatal care requires groups enroll an average of five women per group. This assumes that patients receive all of their care in the group context; although the authors note this is highly unlikely. To date, little is known about factors that influence women’s group prenatal care attendance rates.

Better patient care experiences are associated with better health outcomes (Doyle et al. 2013). As a result, patient satisfaction has gained prominence as an indicator of provider performance in this post-reform era (Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act 2010). With healthcare systems increasingly shifting toward value-based payment strategies, it is essential to identify and support clinical care models that enhance health outcomes and patient satisfaction.

This paper reports a post-hoc secondary analysis of data from the 14-site, cluster randomized controlled trial of CenteringPregnancy Plus in New York City, providing a detailed account of group prenatal care attendance. Our objectives were to identify determinants of group care session attendance and to examine the association between the proportion of prenatal care received in a group setting and care satisfaction. We hypothesized that group prenatal care attendance rates would vary based on patients’ sociodemographic and health characteristics and that women who received a greater proportion of their prenatal care in a group setting would report higher levels of satisfaction with their care. Findings will inform how better to engage pregnant women in group prenatal care, including changes that may be necessary for sustained implementation of this important health innovation.

METHODS

Study design

The CenteringPregnancy Plus study assessed the effectiveness of an evidence-based model of group prenatal care compared to individual obstetric care on birth, neonatal and reproductive health outcomes (trial registration number: NCT00628771). Fourteen community health centers and hospitals in New York City were randomized to provide either the group prenatal care intervention or individual prenatal care. Clinic staff were responsible for implementing all aspects of care, including sending appointment reminders in accordance with their standard procedures. All procedures were approved by Institutional Review Boards at Yale University, Clinical Directors Network, and each clinical site.

Description of the intervention

Details about the CenteringPregnancy Plus intervention have been reported elsewhere (Ickovics et al, 2016; Ickovics et al, 2007; Novick et al, 2013). In brief, CenteringPregnancy Plus begins with a standard clinical intake (history/physical) conducted individually. Thereafter, all care occurs within a group, except for health concerns requiring privacy or urgent medical attention. Groups comprised of 8–12 women of similar gestational age are facilitated by a prenatal care clinician (e.g., obstetrician, midwife, nurse practitioner) and co-facilitator (e.g., nurse, medical assistant). The model consists of ten two hour sessions during which participants: (1) engage in self-care activities, such as weight and blood pressure assessment; (2) receive a brief assessment by a clinician, including fundal height and fetal heart rate monitoring, in a private area within the group space; and (3) participate in group discussions to address issues related to prenatal care, childbirth preparation, postpartum care, HIV prevention including sexual risk reduction, and mental health and psychosocial functioning (e.g., depression, stress reduction). Although facilitators are provided written materials and guidelines for session content, they are trained to use a non-didactic, facilitative approach to encourage group participation and to customize topics to participants’ needs and interests.

Recruitment

Between 2008 and 2011, young women (14–21 years old) attending an early prenatal care visit at a study site were referred by a health care provider or directly approached by research staff for participation in the study. Eligibility criteria included less than 24 weeks gestation, no medical indication of a high-risk pregnancy, less than 22 years old at last birthday, ability to speak English or Spanish, and willingness to participate in the study procedures. Research staff explained the study to eligible participants, answered questions, and obtained informed consent.

Data Collection

Participants completed surveys during the second trimester of pregnancy (14–24 weeks gestation), third trimester (32–42 weeks gestation), and approximately six and twelve months (5–8 months and 11–14 months, respectively) postpartum using Audio-Handheld Assisted Personal Interview technology. This allows participants to listen to questions with headphones while also seeing the questions on a computer screen. Participants were paid $20 for each interview. Trained research staff systematically reviewed maternal and child medical records using case report forms to extract uniform information.

Measures

Attendance

Number of group care sessions and individual care visits attended was determined by cross-referencing the dates of the prenatal care visits listed in patient’s chart with those on which her assigned group’s sessions occurred. Eligibility to attend each group session was based on the participant’s date of study enrollment, and baby’s date of birth. Attendance rates and proportion of prenatal care received in a group context were calculated by dividing the number of group sessions participants attended by the number they were eligible to attend and by total number of prenatal care visits, respectively.

Care satisfaction

Satisfaction with care was measured using the Patient Participation and Satisfaction Questionnaire (Littlefield et al. 1987). Previous work has demonstrated the content and construct validity, as well as reliability, of the Questionnaire among pregnant women (Littlefield et al. 1987; Littlefield et al. 1990). The satisfaction subscale included 17 items from the original scale (e.g., “Procedures and special tests were clearly explained to you before they were done during prenatal care,” “Helpful information was given to you about your pregnancy during prenatal care,” “You were treated with respect during your prenatal care”), and three items added by the study team (“You were allowed to actively participate in your own prenatal care,” “You could voice your opinions about your care during prenatal care,” “Overall, how satisfied were you with your prenatal care”). Responses ranged from “very dissatisfied” (1) to “very satisfied” (5), and were summed such that higher scores indicate greater satisfaction (α = 0.95).

Patient characteristics

Participants reported age, race/ethnicity, country of birth, school enrollment and employment status, relationship status (single versus with a partner) and number of children. They reported food and housing insecurity, defined as having “ever run out of money or food stamps to buy food” or having moved two or more times in the past year, respectively. Presence of the following maternal health conditions, which may require that patients receive additional monitoring and care (Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine et al. 2014), was determined via the medical chart reviews: preexisting diabetes, gestational diabetes and pregnancy-induced hypertension.

Analysis

The analytic sample is limited to participants enrolled at sites randomized to deliver group prenatal care. Descriptive analyses examined participants’ frequency of attendance at group prenatal care sessions and proportion of total prenatal care visits that occurred in a group setting. “Group” was defined as three or more patients.

Multivariable linear regression models tested associations between patient characteristics and percent of group care sessions attended and between the proportion of prenatal care visits that occurred in a group context and care satisfaction. All analyses controlled for site clustering with the effect of the clinical practice modeled as a random effect (Eldridge et al. 2012). Analyses were conducted using SPSS Version 19.0 (Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.).

RESULTS

Sample characteristics

Sixty-seven groups were established during the study period. Group sizes ranged from 3–15 women (mean = 8.16, SD = 3.08); 87% of groups enrolled at least five women.

A total of 575 pregnant women were recruited at the six intervention sites that delivered group prenatal care, of whom 547 (95%) had comprehensive attendance data available. Participants’ mean age was 18.7 years (SD=1.81). The majority (89%) self-identified as Black or Latina, 43% were born outside of the US, 42% were still enrolled in school and 20% were employed at least part-time. Over one-half (54%) described their relationship status as single; 85% were nulliparous. Food and housing insecurity were high: 40% and 29%, respectively. Few participants had pregestational diabetes (0.9%), gestational diabetes (1.3%) or pregnancy-induced hypertension (3.8%).

Attendance

Based on when they enrolled in the study and when they gave birth, group prenatal care participants were eligible to attend an average of 7.29 group sessions (SD = 1.77), of which they came to an average of 4.31 (SD = 3.04), for an overall mean attendance rate of 58% (SD = 38.06). Among those who attended at least one group session (N=446), the attendance rate was 71%.

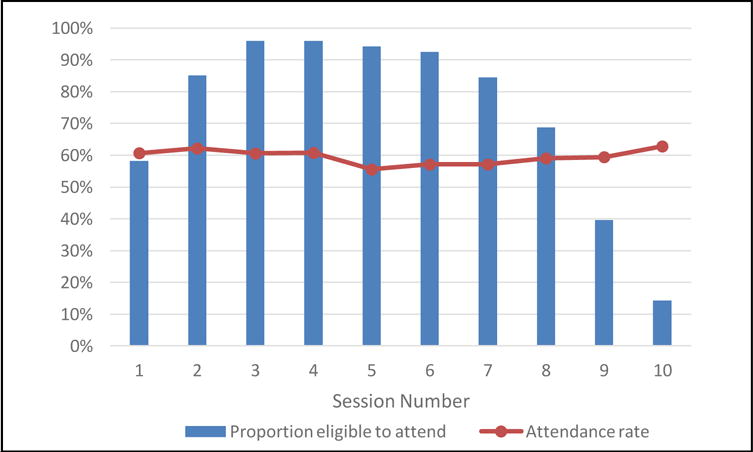

Figure 1 shows the proportion of the total sample eligible to attend and attendance rates among those eligible for each session. The proportion of the total sample who were eligible to attend each session varied considerably, ranging from 14% at session ten (by which time most participants had given birth) to greater than 95% for sessions three and four. However, attendance rates among women eligible to attend each session were fairly consistent, ranging from 56% to 63% per session.

Figure 1. Attendance per session.

1Proportion of the total sample eligible to attend each session based on date of enrollment in the study and baby date of birth.

2Proportion of women who attended each session of those eligible to attend each session.

In addition to group prenatal care visits, participants in the intervention arm of the study attended an average of 5.35 individual prenatal care visits (SD = 3.25). Overall, participants averaged a total of 9.66 prenatal care visits (SD = 3.21). On average, group visits constituted 43.6% of participants total prenatal care visits (range 0–100%; SD=28.42). The number of individual care visits was significantly inversely correlated with number of group sessions attended ([r(449)] = −0.48, p <0.001).

Factors associated with group prenatal care attendance

Table 1 presents unadjusted and adjusted analyses to identify factors associated with group prenatal care attendance. In multivariable analysis, controlling for clustering by site, higher attendance rates were significantly associated with having been born outside the US (B[SE]=11.46 [3.46], p=0.001). The percent of group sessions attended was not associated with any other patient characteristics.

Table 1.

Factors associated with group prenatal care attendance (N = 547)

| Attendance rate1 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Variable | M (SD) or n (%) | Unadjusted | Adjusted2 | ||

|

| |||||

| B (SE) | p-value | B (SE) | p-value | ||

|

| |||||

| Patient demographics | |||||

|

| |||||

| Age (14–21 years) | 18.66 (1.81) | −0.36 (0.90) | .691 | – | – |

|

| |||||

| Race/Ethnicity | |||||

| Latina | 310 (56.7) | 7.84 (3.79) | .042 | 5.32 (5.30) | .316 |

| Black, non-Latina | 177 (32.4) | −9.89 (4.02) | .020 | −3.47 (5.84) | .552 |

| White or other, non-Latina | 60 (11.0) | −0.88 (5.25) | .867 | – | – |

|

| |||||

| Born outside US | 237 (43.3) | 12.12 (3.44) | .001 | 11.46 (3.46) | .001 |

|

| |||||

| Enrolled in school | 228 (41.7) | 2.39 (3.27) | .465 | – | – |

|

| |||||

| Employed | 109 (19.9) | 1.33 (4.04) | .741 | – | – |

|

| |||||

| Relationship status single | 287 (52.5) | −3.63 (3.39) | .284 | – | – |

|

| |||||

| Nulliparous | 440 (80.4) | 6.60 (4.60) | .152 | – | – |

|

| |||||

| Food insecure | 218 (39.9) | −0.13 (3.31) | .970 | – | – |

|

| |||||

| Housing insecure | 153 (28.0) | 2.19 (3.63) | .545 | – | – |

|

| |||||

| Maternal comorbidities | |||||

|

| |||||

| Diabetes (Type I or II) | 5 (0.9) | 9.53 (16.93) | .574 | – | – |

|

| |||||

| Gestational diabetes | 7 (1.3) | −6.20 (14.29) | .664 | – | – |

|

| |||||

| Hypertension | 21 (3.8) | 11.32 (8.41) | .179 | – | – |

Percent of sessions participants’ attended of those they were eligible to attend based on date of enrollment in the study and baby’s date of birth

All of the regression models control for site clustering. The adjusted model includes all variables that were found to be p<0.05 in bivariate (unadjusted) analyses

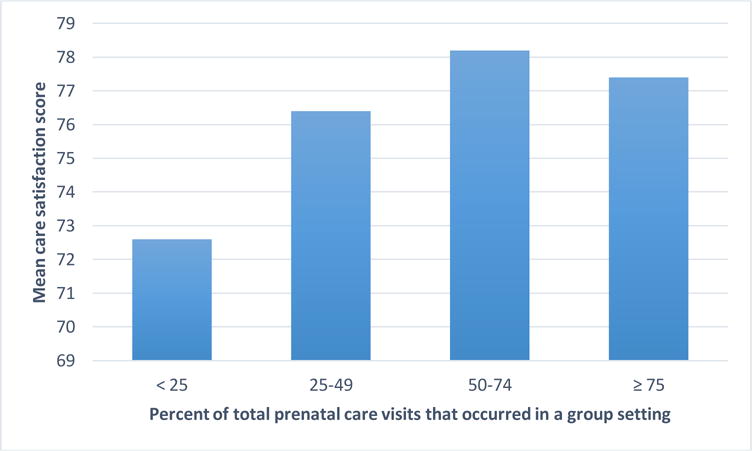

Association between the proportion of prenatal care received in group and care satisfaction

Level of care satisfaction was high among all group care participants (mean=76.54, SD=13.20, range 19–95). Nonetheless, mean levels of care satisfaction were significantly higher among women who received at least half of their prenatal care in a group context compared to those who had a majority of individual care visits (t(438)=−2.97; p=0.003) (Figure 2). Controlling for patient characteristics, a higher percent of total prenatal care visits being group sessions was significantly associated with greater satisfaction with care (B[SE]=0.11 [0.02], p<0.001).

Figure 2.

Relationship between the percent of total prenatal care visits that occurred in a group setting and patient satisfaction with care.

DISCUSSION

We found that a majority of women enrolled in CenteringPregnancy Plus group prenatal care supplemented their group care sessions with individual visits, resulting in provision of a “mixed care” approach. If a patient misses a group session, she typically will be offered an individual care appointment to ensure she receives adequate care throughout pregnancy. Currently, group care delivery is not structured to enable patients who miss a session to be accommodated by a different group. This is deliberate to promote strong cohesion among group members; however, there may be value in practices scheduling regular “drop-in” or “make-up” sessions. Additionally, medical issues may arise that necessitate supplementing group care with individual visits. This may be particularly true for low-income, minority women who are more likely to experience pregnancy-related risk factors, such as hypertensive disorders and diabetes, which may require additional monitoring and care (Paul 2013, Baraket 2014). Future studies should assess the extent to which individual care visits among patients enrolled in group care are clustered toward the end of their pregnancies, when more frequent visits may be indicated, as opposed to being dispersed throughout. Such data, coupled with the dramatic drop observed in this study regarding women’s eligibility to attend sessions nine and ten, may indicate that group care appointments should only be scheduled through 36 weeks gestational age, and thereafter, women should be booked for individual visits to accommodate individual needs.

Women with higher group session attendance rates were more likely to have been born outside the US. Social support provided by one’s prenatal group may be a motivator to attend for more recent immigrants or others with less well established social networks. Although age alone was not found to predict of group session attendance, another recent study found that women in groups with others more diverse in age may be more actively involved in their prenatal care and, in turn, attend more group sessions (Earnshaw et al. 2015).

Our findings also indicate that a higher proportion of prenatal visits occurring in a group context is associated with higher levels of care satisfaction. This is consistent with previous research demonstrating higher levels of care satisfaction among women randomized to group versus individual usual care (Ickovics et al. 2007) and may be the result of reduced wait times for group care visits, as well as increased social support, education, and continuity of care and personal connection with healthcare providers women value in prenatal care services (Edmonds et al. 2015; Novick et al. 2011). Although the number of women eligible to attend varied, average attendance rates remained consistent across sessions, indicating that once women decide to attend group sessions, they are likely to keep coming until childbirth or all sessions for their group sessions have been completed.

This study has several additional limitations. Participants were young, low income, minority women receiving prenatal care in urban clinics; thus, the findings may not be generalizable to other populations. Data were not available to be able to compare women who enrolled in the study at sites randomized to deliver group prenatal care to those who declined to participate. Analyses took into account only a limited number of clinical risk factors that may influence the extent to which additional monitoring and care via individual visits were warranted. Data were not available on facilitator characteristics or the extent to which they maintained fidelity to facilitative group processes. Previous research demonstrates the importance of group leaders’ ability to create a comfortable and inclusive environment (Novick et al. 2013). Structural factors, such as lack of transportation and childcare, also have been identified as barriers to prenatal care attendance (Novick 2009). However, these challenges affect all forms of health care seeking and are not specifically addressed through group prenatal care.

Recent evidence suggests that approximately one-half of low-risk women currently enrolled in traditional individual care would opt to participate in group prenatal care if given a choice (McDonald et al. 2015). Even with imperfect adherence, pregnant women who participate in group prenatal care have a reduced likelihood of experiencing adverse birth outcomes (Ickovics et al. 2007; Ickovics et al. 2016) and report higher levels of care satisfaction (Ickovics et al. 2007), both key considerations for value-based health care programs. Future research should explore alternative implementation structures, such as mixed care models, to improve pregnant women’s ability to receive as much care of their prenatal care as possible in a group setting, as well as value-based reimbursement models and other incentives to encourage more widespread adoption of this important healthcare innovation.

SIGNIFICANCE.

Group prenatal care results in improved birth outcomes in randomized controlled trials, and better attendance at group prenatal care visits is associated with stronger clinical effects. This article fills a gap in the literature by assessing pregnant women’s group prenatal care attendance rates, identifying determinants of group care session attendance, and examining the association between the proportion of prenatal care received in a group setting and care satisfaction.

References

- Catling CJ, Medley N, Foureur M, Ryan C, Leap N, Teate A, Homer CS. Group versus conventional antenatal care for women. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2015;2 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007622.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle C, Lennox L, Bell D. A systematic review of evidence on the links between patient experience and clinical safety and effectiveness. BMJ open. 2013;3(1):e001570. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earnshaw VA, Rosenthal L, Cunningham S, Kershaw T, Lewis J, Rising S, Stasko E, Tobin JN, Ickovics JR. Exploring group composition among young, urban women of color in prenatal care: Implications for satisfaction, engagement, and group attendance. Women’s Health Issues. 2015;26(1):110–5. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2015.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edmonds BT, Mogul M, Shea JA. Understanding Low-Income African American Women’s Expectations, Preferences, and Priorities in Prenatal Care. Family & community health. 2015;38(2):149–157. doi: 10.1097/FCH.0000000000000066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eldridge S, Kerry S. A Practical Guide to Cluster Randomised Trials in Health Services Research. Hoboken NJ: Wiley Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Healthy People 2020 [Internet] Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion; cited 12/2/15. Available from: http://www.healthypeople.gov/ [Google Scholar]

- Ickovics JR, Kershaw TS, Westdahl C, Magriples U, Massey Z, Reynolds H, Rising SS. Group prenatal care and perinatal outcomes: a randomized controlled trial. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2007;110(2 Pt 1):330. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000275284.24298.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ickovics JR, Earnshaw VA, Lewis JB, Kershaw T, Magriples U, Stasko E, Rising SS, Cassells A, Cunningham SD, Bernstein P, Tobin JN. Group Prenatal Care: Cluster RCT of Perinatal Outcomes among Young Women in Urban Health Centers. American Journal of Public Health. 2016;106(2):359–65. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kershaw TS, Magriples U, Westdahl C, Rising SS, Ickovics J. Pregnancy as a window of opportunity for HIV prevention: effects of an HIV intervention delivered within prenatal care. American Journal of Public Health. 2009;99(11):2079. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.154476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littlefield VM, Adams BN. Patient participation in alternative perinatal care: impact on satisfaction and health locus of control. Research in Nursing & Health. 1987;10(3):139–148. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770100305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- March of Dimes. Final Natality Data. National Center for Health Statistics. Accessed March 5, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Littlefield VM, Change A, Adams BN. Participation in alternative care: Relationship to anxiety, depression, and hostility. Research in Nursing & Health. 1990;13:17–25. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770130105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magriples U, Boynton MH, Kershaw TS, Lewis J, Rising SS, Tobin JN, Eppel E, Ickovics JR. The impact of group prenatal care on pregnancy and postpartum weight trajectories. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2015;213(5):688–e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.06.066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald SD, Sword W, Eryuzlu LN, Neupane B, Beyene J, Biringer AB. Why Are Half of Women Interested in Participating in Group Prenatal Care? Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2015:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s10995-015-1807-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novick G. Women’s experience of prenatal care: an integrative review. Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health. 2009;54(3):226–237. doi: 10.1016/j.jmwh.2009.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novick G, Reid AE, Lewis J, Kershaw TS, Rising SS, Ickovics JR. Group prenatal care: model fidelity and outcomes. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2013;209(2):112–e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2013.03.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novick G, Sadler LS, Kennedy HP, Cohen SS, Groce NE, Knafl KA. Women’s experience of group prenatal care. Qualitative Health Research. 2011;21(1):97–116. doi: 10.1177/1049732310378655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, 42 U.S.C. § 18001 (2010).

- Paul KH, Graham ML, Olson CM. The web of risk factors for excessive gestational weight gain in low income women. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2013;17(2):344–351. doi: 10.1007/s10995-012-0979-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picklesimer AH, Billings D, Hale N, Blackhurst D, Covington-Kolb S. The effect of CenteringPregnancy group prenatal care on preterm birth in a low-income population. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2012;206(5):415–e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2012.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowley RA, Phillips LE, O’Dell L, El Husseini R, Carpino S, Hartman S. Group Prenatal Care: A Financial Perspective. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2016;20(1):1–10. doi: 10.1007/s10995-015-1802-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM) Sciscione A, Berghella V, Blackwell S, Boggess K, Helfgott A, Irive B, Keller J, Menard MK, O’Keefe D, Riley L, Stone J. Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM) special report: The maternal-fetal medicine subspecialists’ role within a health care system. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2014;211:607–616. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2014.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]