Abstract

In yeast, the establishment and maintenance of a transcriptionally silent chromatin state are dependent upon the acetylation state of the N terminus of histone proteins. Histone H4 proteins that contain mutations in N-terminal lysines disrupt heterochromatin and result in yeast that cannot mate. Introduction of a wild-type copy of histone H4 restores mating, despite the presence of the mutant protein, suggesting that mutant H4 protein is either excluded from, or tolerated in, chromatin. To understand how the cell differentiates wild-type histone and mutant histone in which the four N-terminal lysines were replaced with alanine (H4-4A), we analyzed silencing, growth phenotypes, and the histone composition of chromatin in yeast strains coexpressing equal amounts of wild-type and mutant H4 proteins (histone H4 heterozygote). We found that histone H4 heterozygotes have defects in heterochromatin silencing and growth, implying that mutations in H4 are not completely recessive. Nuclear preparations from histone H4 heterozygotes contained less mutant H4 than wild-type H4, consistent with the idea that cells exclude some of the mutant histone. Surprisingly, the N-terminal nuclear localization signal of H4-4A fused to green fluorescent protein was defective in nuclear localization, while a mutant in which the four lysines were replaced with arginine (H4-4R) appeared to have normal nuclear import, implying a role for the charged state of the acetylatable lysines in the nuclear import of histones. The biased partial exclusion of H4-4A was dependent upon Cac1p, the largest subunit of yeast chromatin assembly factor 1 (CAF-1), as well as upon the karyopherin Kap123p, but was independent of Cac2p, another CAF-1 component, and other chromatin assembly proteins (Hir3p, Nap1p, and Asf1p). We conclude that N-terminal lysines of histone H4 are important for efficient histone nuclear import. In addition, our data support a model whereby Cac1p and Kap123 cooperate to ensure that only appropriately acetylated histone H4 proteins are imported into the nucleus.

Yeast cells have evolved several levels of control of silent chromatin to ensure that certain genomic domains are not expressed. The most basic level of control exists in the histone proteins that associate with DNA. Specific acetylation patterns in the N-terminal tails of both histones H3 and H4 are required to establish and maintain silent chromatin at telomeres, at the mating type, and at the rRNA gene loci (reviewed in references 14 and 16).

All histone proteins contain a nuclear localization signal located within the N-terminal 40 amino acids (aa) (40, 41). Upon synthesis in the cytoplasm, histones H3 and H4 assemble into heterotetramers and are transported into the nucleus by the karyopherin proteins Kap123p and Kap114p (40). Once in the nucleus, histone tetramers become associated with DNA through the activity of nucleosome assembly factors such as chromatin assembly factor 1 (CAF-1) and replication-coupled assembly factor.

In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, CAF-1 is a complex composed of Cac1p, Cac2p, and Cac3p (reviewed in reference 1) that associates with PCNA to bring H3-H4 tetramers to sites of newly replicated and newly repaired DNA (11, 29, 51, 62). In human cells, CAF-1 is essential for the completion of DNA synthesis during S phase (19). In S. cerevisiae, where CAF-1 activity is not essential (7, 26, 62, 65), several redundant histone chaperones, such as Asf1p, appear to assist in the assembly of chromatin (29, 37, 47, 60, 61). Asf1p was initially identified in S. cerevisiae as a protein that disrupts telomeric silencing when overexpressed (53). In addition, Asf1p is required for efficient replication-independent chromatin assembly (44). The replication-coupled assembly factor chromatin assembly complex consists of a Drosophila homologue of Asf1p in association with specifically acetylated histone H4 and H3 proteins (60).

The Hir proteins, originally identified as regulators of histone gene transcription in S. cerevisiae (50, 56), function with Asf1p (24, 29, 47). Double-mutant strains lacking Cac1p together with either the Asf1p or the Hir protein are severely sick and have more severe silencing defects than either single mutant (24, 29, 47), suggesting that the Cac1p and Asf1/Hir proteins contribute to the redundancy in chromatin assembly.

The highly charged N-terminal tails of each histone protein play a regulatory role in chromatin by undergoing multiple posttranslational modifications and by interacting with several transcription and silencing factors (reviewed in references 10, 21, 22, and 57). In the S. cerevisiae histone H4 N-terminal tail, four lysine residues, at positions 5, 8, 12, and 16, are subject to reversible acetylation (23, 34, 42). Newly made histone H4 is acetylated on K5 and K12 by histone acetyltransferase HatB (43), although acetylation of these two sites is redundant for nucleosome assembly (32). Once H4 is assembled into chromatin, the histone H4 acetylation pattern is modified, with the specific pattern of acetylation differing at different genome locations. Heterochromatin domains contain histone H4 proteins that are acetylated at residues K5 and K8 (15), while histone H4 is typically acetylated on K16 within actively transcribed euchromatin domains (15).

Mutant alleles of the histone H4 gene HHF2 in which codons encoding lysine residues 5, 8, 12, and 16 were replaced with those encoding either alanine (H4-4A), glutamine (H4-4Q), or arginine (H4-4R) encode proteins that cannot undergo acetylation changes and that exhibit defects in heterochromatin function (23, 34, 42). The consequences of these histone mutations include derepression of HMLa and HMRα, resulting in cells that are defective in mating (23, 27, 34, 42).

However, if cells that express mutant histone H4 from a plasmid (e.g., H4-4A or H4-4R) also contain a plasmid with wild-type H4 (H4-WT), the cells are competent to mate (see Table 2) (23, 27, 34, 42). Assuming that both the wild-type and mutant histone proteins are present in similar amounts in these cells, there are two possible explanations for this recessive phenotype. One possibility is that the silent mating cassettes maintain the silent state by tolerating some mutant histone H4 protein in the chromatin. An alternative possibility is that when wild-type histone H4 is present, the mutant protein is excluded from the silent chromatin. To investigate the mechanism(s) by which heterochromatin tolerates and/or excludes histones with inappropriate N-terminal tail acetylation, we constructed strains carrying single, integrated copies of mutant H4-4A and wild-type histone H4 genes to determine their effect on chromatin structure when both are present in a single cell. We found that the phenotype of these heterozygous strains is not completely wild type, indicating that some mutant histone is included in chromatin. In addition, in these histone H4 heterozygotes, the mutant H4 proteins are partially excluded from nuclei and from chromatin by the activity of the largest CAF-1 subunit, Cac1p, and to a lesser degree by the karyopherin Kap123p. Surprisingly, mutation of Cac2p, another CAF-1 subunit, did not affect the exclusion of mutant H4 protein. Thus, mutant histones are partially excluded from the nucleus by an activity of Cac1p that is independent of CAF-1. Furthermore, the presence of ∼30% mutant histone H4-4A in heterochromatin leads to detectable defects in silencing.

TABLE 2.

Phenotypic analysis of strains expressing H4-WT and H4-4A histone H4 proteins

| Strain | Avg generation time (min) ± SD | Avg mating efficiency (%) ± SD | % Shmoo cluster (% buds) |

|---|---|---|---|

| H4-WT | 94 ± 4 | 4.2 ± 0.04 | 37 (9) |

| H4-4A/WT | 121 ± 11 | 4.6 ± 0.03 | 80 (18) |

| H4-4A MATa | 145 ± 7 | 0 | Buds |

| H4-4A MATα | 145 ± 7 | 0.45 ± 0.003 | NDa |

| cac1Δ | ND | ND | 75 (9) |

| cac1Δ H4-4A MATa | ND | ND | 67 (37) |

ND, not determined in this study.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Yeast strains and plasmids.

All of the strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. The asf1Δ::his5+ allele was obtained from R. Kamakaka in strain ROY1246 (60). The hir3Δ::HIS3 allele was obtained from P. Kaufman in strain PKY379 (24), and the nap1Δ::LEU2 allele was obtained from D. Kellogg in strain DK131 (28). All of these alleles were introduced into the W303 strain background by standard crosses and multiple backcrosses. The kap123Δ::HIS3 allele was constructed with primers 1293 and 1294 with p1106 (pFA-GFP HIS3) as the template (31). The VIIL-URA3-TEL construct from p105 was transformed into H4-WT, H4-4A/WT, and cac1Δ strains to generate strains YJB8602, YJB8603, and YJB8604. Integration was confirmed by Southern analysis of PstI-digested genomic DNA probed with URA3 sequences (5). Plasmids 632, 860, 861, and p1540 were obtained from J. Szostak, plasmid 974 was obtained from M. Grunstein, and plasmid p920 was obtained from M. M. Smith. Sporulation and tetrad dissection were performed by standard methods (49). Strains were maintained in standard yeast media (48). Determination of generation time and quantitative mating assays were performed essentially as previously described (45) for yeast strains YJB7349 (H4-WT), YJB7418 (H4-WT), YJB7350 (H4-4A), YJB7354 (H4-4A), YJB7348 (H4-4A/WT), YJB7355 (H4-4A/WT), and YJB7356 (H4-4A/WT). Shmoo cluster analysis was performed essentially as previously described (7).

TABLE 1.

Yeast strains, plasmids, and primers used in this study

| Strain, plasmid, or primer | Relevant genotype, description, or sequence | Source | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parental strains | ||||

| YJB195 | MATaade2-1 can1-100 his3-11,15 leu2-3,112 trp1-1 ura3-1 | W303a | ||

| YJB209 | MATα ade2-1 can1-100 his3-11,15 leu2-3,112 trp1-1 ura3-1 | W303α | ||

| YJB1463 | MATaVR-ADE2-TEL | S. Enomoto | ||

| YJB1801 | MATacac2::TRP1 | S. Enomoto | ||

| YJB1804 | MATacac1::LEU2 cac2::TRP1 | S. Enomoto | ||

| YJB1862 | MATacac1::LEU2 cac3::hisG | S. Enomoto | ||

| YJB2704 | MATanap1::LEU2 | S. Enomoto | ||

| YJB4713 | MATahir3::HIS3 | S. Enomoto | ||

| YJB6277 | MATaasf1::his5+ | S. Enomoto | ||

| YJB6165 | MATacac1::LEU2 | S. Enomoto | ||

| YJB7649 | MATα hhf2-4A::KanR-HHT2::hhf1-hht1 hhf2-hht2::CaURA3 | Spore colony from YJB7344 × YJB1463 | ||

| YJB8349 | MATakap123::HIS3 | YJB195 transformed with kap123::HIS3 | ||

| YJB8420 | MATacac1::LEU2 | This study | ||

| Histone plasmid strains | ||||

| YJB344 | Δ(hht1-hhf1) Δ(hht2-hhf2)/p632 (H4-WT) | 41 | ||

| YJB347 | Δ(hht1-hhf1) Δ(hht2-hhf2)/p860 (H4-4A) | 41 | ||

| YJB348 | Δ(hht1-hhf1) Δ(hht2-hhf2)/p861 (H4-4R) | 41 | ||

| YJB2318 | Δ(hht1-hhf1) Δ(hht2-hhf2)/p632/p860 | YJB344 transformed with p860 | ||

| YJB2861 | hhf1::HIS3 hhf2::LEU2/p974 (H4-4Q) | 16 | ||

| H4-WT integrated strains | ||||

| YJB7349 | hhf2-hht2::CaURA3 | Spore colony from YJB1463 × YJB7345 | ||

| YJB7351 | HHF1/HHF2 | Spore colony from YJB1463 × YJB7345 | ||

| YJB7418 | HHF1/HHF2 | Spore colony from YJB1463 × YJB7345 | ||

| H4-4A integrated strains | ||||

| YJB7344 | MATα hhf2-4A::KanR-HHT2::hhf1-hht1 hhf2-hht2::CaURA3 | YJB7143 transformed with hhf2-hht2::CaURA3 | ||

| YJB7345 | MATα hhf2-4A::KanR-HHT2::hhf1-hht1 hhf2-hht2::CaURA3 | YJB7143 transformed with hhf2-hht2::CaURA3 | ||

| YJB7350 | MATahhf2-4A::KanR-HHT2::hhf1-hht1 hhf2-hht2::CaURA3 | YJB7151 transformed with hhf2-hht2::CaURA3 | ||

| YJB7354 | MATα hhf2-4A::KanR-HHT2::hhf1-hht1 hhf2-hht2::CaURA3 | Spore colony from YJB1463 × YJB7344 | ||

| H4-4A/WT heterozygote integrated strains | ||||

| YJB7143 | MATα hhf2-4A::KanR-HHT2::hhf1-hht1 HHF2 | This study | ||

| YJB7151 | MATahhf2-4A::KanR-HHT2::hhf1-hht1 HHF2 | This study | ||

| YJB7348 | MATahhf2-4A::KanR-HHT2::hhf1-hht1 HHF2 | Spore colony from YJB1463 × YJB7345 | ||

| YJB7355 | MATα hhf2-4A::KanR-HHT2::hhf1-hht1 HHF2 | Spore colony from YJB1463 × YJB7345 | ||

| YJB7356 | MATahhf2-4A::KanR-HHT2::hhf1-hht1 HHF2 | Spore colony from YJB1463 × YJB7345 | ||

| YJB8396 | MATahhf2-4A::KanR-HHT2::hhf1-hht1 asf1::his5+ | Spore colony from YJB6277 × YJB7649 | ||

| YJB8398 | MATahhf2-4A::KanR-HHT2::hhf1-hht1 cac1::LEU2 | Spore colony from YJB6165 × YJB7649 | ||

| YJB8400 | MATahhf2-4A::KanR-HHT2::hhf1-hht1 hir3::HIS3 | Spore colony from YJB4713 × YJB7354 | ||

| YJB8402 | MATahhf2-4A::KanR-HHT2::hhf1-hht1 nap1::LEU2 | Spore colony from YJB2704 × YJB7649 | ||

| YJB8405 | MATahhf2-4A::KanR-HHT2::hhf1-hht1 kap123::HIS3 | Spore colony from YJB7649 × YJB8349 | ||

| YJB8817 | MATahhf2-4A::KanR-HHT2::hhf1-hht1 cac2::TRP1 | Spore colony from YJB1801 × YJB7649 | ||

| URA3-TEL strains | ||||

| YJB8602 | MATaVIIL::URA3-TEL | YJB195 transformed with p105 | ||

| YJB8603 | MATacac1Δ VIIL::URA3-TEL | YJB8420 transformed with p105 | ||

| YJB8604 | MATahhf2-4A::KanR-HHT2::hhf1-hht1 VIIL::URA3-TEL | YJB7143 transformed with p105 | ||

| N-terminal histone H4-GFP fusion strains | ||||

| YJB8342 | HHF1/HHF2 p2087 (H4-WT-GFP) | YJB195 transformed with p2087 | ||

| YJB8343 | HHF1/HHF2 p2088 (H4-4A-GFP) | YJB195 transformed with p2088 | ||

| YJB8432 | cac1Δ p2087 (H4-WT-GFP) | YJB8420 transformed with p2087 | ||

| YJB8378 | cac1Δ p2088 (H4-4A-GFP) | YJB8420 transformed with p2088 | ||

| YJB9010 | HHF1/HHF2 p2115 (H4-K8R-GFP) | YJB195 transformed with p2115 | ||

| YJB9011 | HHF1/HHF2 p2116 (H4-K5,12R-GFP) | YJB195 transformed with p2116 | ||

| YJB9012 | HHF1/HHF2 p2021 (H4-4R-GFP) | YJB195 transformed with p2021 | ||

| YJB9013 | cac1Δ cac2Δ p2087 (H4-WT-GFP) | YJB1804 transformed with p2087 | ||

| YJB9014 | cac1Δ cac2Δ p2088 (H4-4A-GFP) | YJB1804 transformed with p2088 | ||

| YJB9015 | cac1Δ cac3Δ p2087 (H4-WT-GFP) | YJB1862 transformed with p2087 | ||

| YJB9016 | cac1Δ cac3Δ p2088 (H4-4A-GFP) | YJB1862 transformed with p2088?xpp Tr>Strain, plasmid, or primer | Relevant genotype, description, or sequence | Source |

| Chromatin immunoprecipitation strains | ||||

| YJB7650 | MATα hhf2-4A::KanR-HHT2::hhf1-hht1 hhf2-hht2::CaURA3 sir3::SIR3-HA-TRP1 | YJB7354 transformed with sir3::SIR3-HA-TRP1 | ||

| YJB7651 | MATα hhf2-hht2::CaURA3 sir3::SIR3-HA-TRP1 | YJB7349 transformed with sir3::SIR3-HA-TRP1 | ||

| YJB7902 | MATα hhf2-4A::KanR-HHT2::hhf1-hht1 sir3::SIR3-HA-TRP1 | YJB7143 transformed with sir3::SIR3-HA-TRP1 | ||

| YJB8651 | MATα hhf2-4A::KanR-HHT2::hhf1-hht1 p1307 (Sir3-HA) | YJB7143 transformed with p1307 | ||

| Plasmid | ||||

| p105 | VIIL-URA3-TEL | 12 | ||

| p632 | CEN4 ARS1 LYS2 HHT2-HHF2 | 42 | ||

| p860 | CEN4 ARS1 URA3 HHT2-hhf2-4A | 42 | ||

| p920 | CEN6 ARS4 LEU2 HHT1-hhf1-K5,12R | 34 | ||

| p925 | CEN6 ARS4 LEU2 HHT1-hhf1-K8R | S. Enomoto | ||

| p1307 | 2μm TRP1 SIR3-HA | 17 | ||

| p1540 | CEN4 ARS1 URA3 HHT2-hhf2-4R | 42 | ||

| p2077 | CEN6 ARS4 HIS3 MET3::HHF2(aa 1-41) | This study | ||

| p2078 | CEN6 ARS4 HIS3 MET3::hhf2-4A(aa 1-41) | This study | ||

| p2087 | CEN6 ARS4 HIS3 TRP1 MET3::HHF2-GFP | This study | ||

| p2088 | CEN6 ARS4 HIS3 TRP1 MET3::hhf2-4A-GFP | This study | ||

| p2113 | CEN6 ARS4 HIS3 MET3::hhf2-K5,12R(aa 1-41) | This study | ||

| p2114 | CEN6 ARS4 HIS3 MET3::hhf2-K8R(aa 1-41) | This study | ||

| p2117 | CEN6 ARS4 HIS3 MET3::hhf2-4R(aa 1-41) | This study | ||

| p2115 | CEN6 ARS4 HIS3 TRP1 MET3::hhf2-K8R-GFP | This study | ||

| p2116 | CEN6 ARS4 HIS3 TRP1 MET3::hhf2-K5,12R-GFP | This study | ||

| p2121 | CEN6 ARS4 HIS3 TRP1 MET3::hhf2-4R-GFP | This study | ||

| Primer | ||||

| 340 | ATGGAAGCTTCACATTTGC | |||

| 404 | CATGATGTATACATTGTGTGAGATATAGTTGTATTCCA ATTTGTGTCC | |||

| 684 | ATCCCCTGCAATAGTAGCGATAGTAAAAAGAGGCGCA TACATCCTACGCCAGTCGATTTGCGGATCCCCGGGT TAATTAA | |||

| 685 | AGCACACAATGGAAAATATCTTCGCTGGCAAACTAGA TTAGGCATTCTTATGTACCGCATGAATTCGAGCTCG TTTAAAC | |||

| 885 | GCCCAGATCTTCCCGCTTTATATTCATGATCTTTC | |||

| 886 | GCCCAGATCTTTAACCACCGAAACCATATAAGG | |||

| 943 | ATATTAGGATGAGGCGGTGA | |||

| 948 | TGTTTTTGTTCGTTTTTTACTAAAACTGATGACAATCA AATATTCATGATCTTTCACCT | |||

| 978 | TAACACGCTTAGCGTGAATAGCAGCCAGATTAGTGTC TTCCGATAGGCCACTAGTGGATCTG | |||

| 979 | TGTAAGTAACAGAGTCCCTGATGACGGATTCCAAGAA GGACAGCTGAAGCTTCGTACGC | |||

| 1001 | CTATTTAATCTGCTTTTCTTGTCTAATAAATATATATGT GAATTCGAGCTCGTTTAAAC | |||

| 1002 | CACAGAGTAAATTCCCAAAT | |||

| 1293 | AACTGAGGGACGAAAAACACTTTTTTAGTATCAAGTA GTATAATGCGGATCCCCGGGTTAATTAA | |||

| 1294 | GTTTATCGAAACAGACGAGAATAAAAAATGGTTTTAA AAAAATCAGAATTCGAGCTCGTTTAAAC | |||

| 1358 | GTTGTGATATCGCGTTTATTAAAATGTCCGGTAGAGGT AAAGGTGGT | |||

| 1359 | GTTGTGATATCGCGTTTATTAAAATGTCCGGTAGAGGT GCCGGTGGT | |||

| 1360 | CGCGGATCCTAATCTTCTGATAGCTGGCTTAGT | |||

| 1427 | TAACATTCAAGGTATCACTAAGCCAGCTATCAGAAGAA TACGGATCCCCGGGTTAATTAA | |||

| 1428 | CTCACTATAGGGCGAATTGGAGCTCCACCGCGGTGGCG GCGAATTCGAGCTCGTTTAAAC | |||

| 1694 | GTTGTGATATCGCGTTTATTAAAATGTCCGGTAGAGGTC GGGGTGGT |

Generation of integrated histone H4 mutant strains.

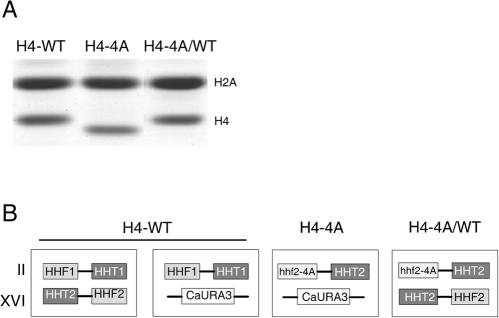

In S. cerevisiae, the genes encoding histones H4 and H3 (HHF and HHT, respectively) are divergently transcribed from the same promoter. There are two copies of the histone H4 and H3 genes, copies I and II, that encode identical proteins (54). The copy II genes are expressed at a higher level than the copy I genes (4). To facilitate the analysis of strains expressing two different histone H4 proteins, strains were generated that contained the copy II H4-4A mutant integrated at the copy I genomic locus (see Fig. 2B). The wild-type histone H4 gene located at the copy II locus was either deleted to generate a strain expressing only the H4-4A protein or left intact to produce strains expressing both the H4-WT and H4-4A proteins under the control of the same copy II promoter (Fig. 2B).

FIG. 2.

(A) Coomassie-stained gel of yeast strains expressing H4-WT and H4-4A histone proteins from centromere plasmids in the H4-WT (YJB344), H4-4A (YJB347), and H4-4A/WT (YJB2318) strains. Nuclear extracts of exponentially growing strains were prepared and separated by reverse-phase HPLC. Fractions containing histones H2A and H4 were separated by SDS-22% PAGE. (B) Diagram representing the different histone H4 mutant strains constructed as described in Materials and Methods. HHF1, HHF2, and hhf2-4A code for histone H4 proteins; HHT1 and HHT2 encode histone H3; and CaURA3 encodes the C. albicans URA3 gene that was used to disrupt the chromosome XVI histone gene locus.

The strains were generated as follows. First, to clone a portion of the 3′ end of the wild-type histone H4 gene containing putative termination sequences next to the G418 resistance marker, a 307-bp BamHI fragment from p652 was inserted into the BamHI-BglII sites in p1107 [pFA6-GFP(S65T)Kan] (31), generating p1867. Next, PCR primers 885 and 886 were used to amplify the H4-4A and wild-type H3 genes from p860. The PCR product was digested with BamHI and inserted into the BamHI site of p1867 to produce p1893. PCR primers 948 and 1001 were used to amplify the copy II histone genes from p1893 with copy I integrating ends. The resulting PCR product was transformed into W303 Mata and Matα parental strains. Transformants were screened by colony PCR with primers 943 and 1002, Southern analysis, and DNA sequencing for integration at the copy I locus. Positive strains were saved as YJB7143 and YJB7151.

To disrupt the copy II histone gene locus, primers 978 and 979 were used to amplify the Candida albicans URA3 gene from p1584 with copy II tails. The resulting PCR product was transformed into either YJB7143 or YJB7151. Southern analysis confirmed replacement of the copy II histone locus with the URA3 gene in strains YJB7344 and YJB7346. Strains YJB7344 and YJB7346 were crossed to W303 Mata and Matα (YJB195, YJB209) to obtain progeny that contain the following histone protein profiles: H4-WT (YJB7351, YJB7418, YJB7349), H4-4A/WT (YJB7355, YJB7356), and H4-4A (YJB7354) (Table 1).

The histone N-terminal green fluorescent protein (GFP) fusion constructs were made as follows. Primers 1358 and 1360 were used to amplify the first 41 aa of the wild-type histone H4 allele from genomic DNA. Primers 1359 and 1360 were used to amplify the first 41 aa of H4-4A from plasmid p860. Primers 1694 and 1360 were used to amplify the first 41 aa of H4-K5,12R and H4-4R from plasmids p920 and p1540, respectively. Primers 1358 and 1360 were used to amplify the first 41 aa of H4-K8R from plasmid p925. These PCR products were digested with BamHI and EcoRI and cloned into the corresponding sites of p678 (CEN/ARS/HIS3/MET3, pJR1588 obtained from the Jasper Rine laboratory) to generate p2077 (pMET-H4-WT), p2078 (pMET-H4-4A), p2114 (pMET-H4-K8R), p2113 (pMET-H4-K5,12R), and p2117 (pMET-H4-4R). These plasmids were transformed into W303 cells, selecting for His+ transformants. Primers 1427 and 1428 were used to amplify GFP-TRP1 from pFA6-GFP(S65T)TRP1 (31). The resulting PCR product was transformed into the His+ W303 strains, and His+ Trp+ transformants were selected. PCR and DNA sequencing confirmed that they contained the MET3 promoter driving the histone H4-GFP fusion protein. The constructs were saved as p2087 (H4-WT-GFP), p2088 (H4-4A-GFP), p2115 (H4-K8R-GFP), p2116 (H4-K5,12R-GFP), and p2121 (H4-4R-GFP). Strains expressing H4-WT-GFP consistently produced higher levels of the fusion protein than did strains expressing H4-4A-GFP. However, both fusion proteins were readily detected by fluorescence microscopy.

Chromatin purification.

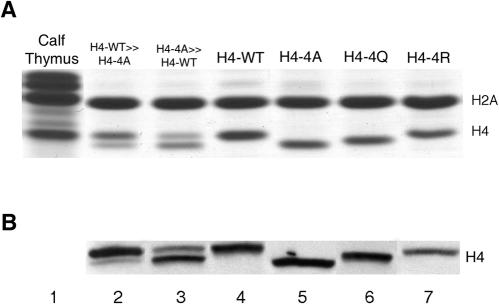

Histone proteins from YJB344, YJB347, YJB348, YJB2318, and YJB2861 were isolated (Fig. 1A and 2A) as described by Waterborg (64). Briefly, 100-ml volumes of exponentially growing cultures were collected and lysed with glass beads and nuclei were enriched with a sucrose nuclear isolation buffer (0.25 M sucrose, 10 mM MgCl2, 2.5 mM spermidine, 0.5 mM spermine, 20 mM HEPES, 100 mM sodium butyrate, 0.1% [wt/vol] Triton X-100, 5 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, pH 7). Chromatin was disrupted by sonication, and the sample was fractionated by reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis. Histone H4 proteins copurified with histone H2A in the 30- to 40-min acetonitrile fractions. The appropriate fractions were collected, lyophilized, and analyzed on 15-cm-long sodium dodecyl sulfate-18% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) gels stained with Coomassie brilliant blue. The amounts of histone proteins were quantitated by densitometry of the stained gel.

FIG. 1.

Histone H4 variant proteins can be resolved on polyacrylamide gels. (A) Coomassie-stained gel showing the different mobilities of the wild-type and mutant histone H4 proteins from the H4-WT (YJB344), H4-4A (YJB347), H4-4Q (YJB2861), and H4-4R (YJB348) strains. Nuclear extracts were prepared from exponentially growing strains and separated by reverse-phase HPLC, and fractions containing histones H2A and H4 were separated by SDS-18% PAGE. Histone H2A coelutes with H4 during HPLC and serves as a loading control (64). Lanes 2 and 3 contain mixtures of extracts from the H4-WT and H4-4A strains. Lane 2 contains approximately 75% H4-WT and 25% H4-4A, and lane 3 contains approximately 75% H4-4A and 25% H4-WT as determined by densitometry of the stained gel. (B) Western blot assay of WCEs of the same strains as in panel A separated by SDS-22% PAGE and probed with the anti-H4-17-33 antibody.

Histone proteins from YJB7349, YJB7354, YJB7348, YJB8398, YJB8400, YJB8402, YJB8405, and YJB8817 were used for Western analysis. Histone H4 proteins were isolated in accordance with the reduced-scale protocol of Edmondson and Roth (6). In brief, 25-ml cultures of each strain were collected and washed with sterile water. The pellet was incubated in 5 ml of 0.1 mM Tris (pH 9.4)-10 mM dithiothreitol for 15 min at 30°C with gentle shaking in 30-ml Oakridge tubes. The cells were collected and washed in 5 ml of S buffer (1.2 M sorbitol, 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.4). The pellet was resuspended in 5 ml of S buffer plus 200 μl of 10 mg of Zymolyase (dissolved in S buffer) per ml and incubated at 30°C with gentle shaking for 15 min. Spheroplasts were examined under a light microscope to verify cell wall digestion. Samples were then placed on ice, and 10 ml of ice-cold 1.2 M sorbitol-20 mM piperazine-N,N′-bis(2-ethanesulfonic acid) (PIPES)-1 mM MgCl2 (pH 6.8) was added. Cells were pelleted at 3,500 rpm for 5 min at 4°C in a Beckman JA-10 rotor. The cell pellet was resuspended in 5 ml of ice-cold nucleus isolation buffer (0.25 M sucrose, 60 mM KCl, 14 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM CaCl2, 15 mM morpholineethanesulfonic acid, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 0.8% Triton X-100, pH 6.6). The spheroplasts were held on ice water for at least 20 min and centrifuged at 15,000 rpm in a JA-10 rotor for 10 min. The nucleus-enriched pellet was resuspended in 200 to 500 μl of 1× reducing buffer (60 mM Tris [pH 6.8], 5% glycerol, 2% SDS, 4% β-mercaptoethanol, 0.0025% bromophenol blue) with 6 M urea and transferred to a Microfuge tube. The samples were heated at 70°C for 10 to 15 min. The lysate was centrifuged at 14,000 rpm (CLP Micro-Centrifuge) at room temperature for 5 min, and the resulting supernatant was transferred to a fresh Microfuge tube and stored at −20°C. Protein concentration was determined by measurement of A280.

Antibody production.

A peptide corresponding to aa 17 to 33 of histone H4 (RHRKILRDNIQGITKPA) was synthesized and used to immunize rabbits (BioSource/QBC, Hopkinton, Mass.). Whole rabbit sera were affinity purified against the immunizing peptide and eluted with glycine. The immunoglobulin G fraction contains 1.56 mg of protein/ml stored in phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.4) without Ca2+ or Mg2+. Typically, a 1:5,000 dilution of the affinity-purified antibody was used for immunoblot analysis (see below).

Immunoblot analysis and quantitation.

For whole cell extracts (WCEs), liquid cultures of exponentially growing strains (YJB344, YJB347, YJB348, YJB2318, YJB2861, and YJB7348) were harvested, washed two times with 1× phosphate-buffered saline, and resuspended in 50 μl of lysis buffer (40 mM Tris-HCl [pH 6.8], 5% SDS, 8 M urea, 0.1 M EDTA). The tubes were immediately agitated in a Vortex mixer with 250 μl of glass beads for 90 s and heated to 70°C for 3 min, and then 250 μl of protein loading buffer was added and the mixture was incubated for 5 min at 70°C. The resulting lysates were centrifuged for 10 min at 14,000 rpm (CLP Micro-Centrifuge). Protein from the supernatant (200 U of A280) was separated by SDS-22% PAGE. Immunoblot analysis was performed essentially as previously described (8). Anti-histone H4 antibody {1:5,000 in 1% BSA-TBS-T [1% bovine serum albumin, 137 mM sodium chloride, 10 mM Tris (pH 7.4), 0.1% Tween 20]} was detected with a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit secondary antibody (1:45,000 in 1% BSA-TBS-T [Santa Cruz Biotechnologies, Santa Cruz, Calif.]). Mouse monoclonal anti-GFP antibody at 1:2,000 in 0.2% milk-TBS-T (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, Ind.) was detected with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse secondary antibody (1:45,000 in 0.2% milk-TBS-T [Santa Cruz Biotechnologies]).

The ratio of H4-WT to H4-4A from immunoblot films scanned by a Bio-Rad densitometer (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.) was determined with ImageQuant software (Amersham Biosciences, Amersham, Buckinghamshire, England). In brief, ImageQuant generated values of the intensity of each band on the immunoblot (volume). The volume of the H4-WT band was divided by the total volume of H4-WT and H4-4A. This value was converted to a percentage by multiplying it by 100. The average and standard deviation of H4-WT were calculated by Microsoft Excel. The H4-4A histone percentage is the remaining amount of the total histone (100 − %H4-WT).

Microscopy.

For strains containing pMET-N-terminal histone H4-GFP fusion constructs, cells were grown on SDC−His−Trp+Met+Cys solid media overnight at 30°C and then diluted into 2-ml liquid cultures of SDC−His−Trp−Met−Cys+Ade at 30°C for 6 h to induce histone H4-GFP expression. Images were collected with a Nikon Eclipse E600 microscope at a magnification of ×100 and analyzed with Metamorph imaging software (Universal Imaging Corporation, Sunnyvale, Calif.).

ChIP.

Chromatin immunoprecipitations (ChIPs) were performed on yeast strains YJB7650, YJB7651, and YJB7902 essentially as described by Meluh et al. (38). Silent chromatin was immunoprecipitated with 10 μg of anti-hemagglutinin (HA) antibody (12CA5; Roche Applied Science) per ml, and active chromatin was immunoprecipitated with 1 μg of anti-acetyl-histone H3 (Upstate Biotech, Lake Placid, N.Y.) per ml. Primers for SSC1 were 1478 (GCTTCGGCCCGGTTCCA) and 1479 (CAGCAAGCATCTTGGTGCG). Primers for HMR-E were 1480 (CTAAATCGCATTTCTTTTCGTCCAC) and 1481 (TAACAAAAACCAGGAGTACCTGCGC). PCR conditions were as described by Rusche and Rine (46).

To determine the ratio of H4-WT to H4-4A in active versus silent chromatin, a modified ChIP protocol was developed. Cells were fixed with 1% (final concentration) formaldehyde for 45 min. Nuclear extracts from a 1-liter culture of an H4-4A/WT strain containing pSIR3-HA (YJB8651) were prepared as described above. Nuclei were isolated and resuspended in 6 ml of ChIP buffer (50 mM HEPES [pH 7.5], 140 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% sodium deoxycholate, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride). This solution was sonicated three times for 15 s and pelleted to remove cellular debris. The remaining chromatin solution was used in immunoprecipitation reactions. Two hundred microliters of lysate was used to immunoprecipitate histone H3 with 10 μl of anti-H3 antibody, and 500 μl of lysate was used to immunoprecipitate SIR3-HA with 10 μl of anti-HA antibody (see above). The immunoprecipitations were incubated overnight at 4°C with gentle rotation. Forty microliters of a 50% slurry of protein A-Sepharose (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, Mo.) was added to each tube, and the mixture was incubated for 2 h at 4°C with rotation. The beads were washed with 1 ml of ChIP buffer TSE-500 (0.1% SDS, 1% Triton X-100, 2 mM EDTA, 20 mM Tris [pH 8.1], 500 mM NaCl) and Tris-EDTA. The immune complexes were eluted from the protein A beads by incubation with 50 μl of 1× reducing buffer with 6 M urea for 15 min at 70°C. The eluate was then boiled for 45 min to reverse formaldehyde cross-links. The entire immunoprecipitate was separated by SDS-22% PAGE. Western analysis was performed as described above. Quantitation of the amounts of wild-type and mutant histone proteins was determined by a Bio-Rad densitometer with ImageQuant software (Amersham Biosciences).

RESULTS

Different histone H4 proteins can be resolved by SDS-PAGE.

In this report, we refer to the different histone genes by their protein designations. The wild-type HHF1 and HHF2 genes encode identical histone H4 proteins, which will be referred to as H4-WT. In the mutant H4-4A protein, lysines 5, 8, 12, and 16 have been replaced with alanine. The histone heterozygote strains, which express both wild-type and mutant proteins, are designated H4-4A/WT. Similarly, H4-4Q and H4-4R encode mutant proteins in which all four N-terminal lysines are replaced with glutamine or arginine, respectively.

Cells expressing both wild-type and mutant forms of histone H4 have been reported to have essentially wild-type mating properties (23, 34, 42). We asked if this is due to exclusion of the mutant histone from chromatin or to the ability of functional chromatin to tolerate the incorporation of up to 50% mutant histones. To study cells expressing both types of histones and to compare the levels of the two histone proteins in the same extracts, we developed a protocol that allowed us to isolate and distinguish between wild-type and mutant H4 proteins by SDS-PAGE.

Nuclear extracts were prepared from cells expressing H4-WT or one of the histone H4 mutants (H4-4A, H4-4Q, or H4-4R) from low-copy-number plasmids (Table 1). These extracts were separated by reverse-phase HPLC to isolate the fraction containing histones H2A and H4 (64). The appropriate acetonitrile fractions (63, 64) were then separated by SDS-18% PAGE and stained with Coomassie brilliant blue to detect the proteins. This protocol allowed us to resolve the H4-WT form from the H4-4A and H4-4Q forms (Fig. 1A, lanes 4 to 6). In contrast, the mobilities of H4-WT and the H4-4R form were difficult to distinguish (Fig. 1A, lanes 4 and 7). In addition, when H4-WT and H4-4A extracted histones were mixed together, we could differentially detect the two histone H4 proteins in the same gel lane (Fig. 1A, lanes 2 and 3). Thus, while H4-WT, H4-4A, and H4-4Q differ by only four amino acid substitutions, this protocol clearly distinguishes between the wild type and these mutant histone proteins prepared from nuclear extracts.

To analyze H4-WT and mutant H4 proteins from WCEs, we separated the extracts by SDS-22% PAGE and detected the histone H4 proteins on immunoblots with an antibody against a histone H4 peptide from a region located immediately adjacent to the histone H4 N-terminal tail (aa 17 to 33), which is identical in H4-WT and the H4 mutant proteins (see Materials and Methods). The resulting antibody (anti-H4-17-33) was then used to probe Western blots of WCEs from strains expressing different histone H4 mutants from plasmids. H4-WT and each of the H4 mutant proteins was recognized by anti-H4-17-33 (Fig. 1B, lanes 2 to 7). The anti-H4-17-33 antibody was able to detect differences in the amounts of the two proteins when WCEs from H4-WT and H4-4A were mixed and run in the same gel lane (Fig. 1B, lanes 2 and 3). Since the anti-H4-17-33 antibody recognizes a region of histone H4 that has the same sequence in all of the histone H4 proteins, we assume that it has similar affinity for all of them and thus can be used to compare the quantities of each histone protein from heterozygous strains. In the experiments described below, we focused primarily on analyzing the H4-4A mutant histone relative to H4-WT because H4-4A is the mutant protein with the largest difference in electrophoretic mobility relative to that of H4-WT.

H4-WT and H4-4A histone proteins expressed from plasmids are not present in equal amounts.

In previous studies (23, 34, 42), as well as in our initial experiments (Fig. 1), mutant histone proteins were expressed from plasmids. We also examined a strain (YJB2318) that contained H4-WT and H4-4A expressed from two different low-copy-number (centromere) plasmids. Each plasmid contained the same promoter driving the expression of either the H4-WT (p632) or the H4-4A (p680) protein, but each plasmid contained a different selectable marker. To ask if the H4-WT and H4-4A proteins were present in similar amounts in these plasmid-containing cells, we prepared nuclear extracts from these strains and analyzed them by HPLC fractionation and SDS-18% PAGE. When both plasmids were present in the same cell, however, nuclear extracts contained much more H4-WT protein than H4-4A protein (Fig. 2A). In fact, the amount of H4-4A protein in the nuclear extracts was below the level of detection in the Coomassie-stained gels.

Since the yeast strain contained two plasmids, we could not rule out the possibility of selective pressure to lose the H4-4A plasmid. Alternatively, differences in the selectable markers used may have altered the copy number in this strain. To obviate these possibilities, we constructed stable yeast strains that contained integrated alleles of the histone H4 genes.

Phenotypes of H4-4A and H4-4A/WT strains.

Previous reports that histone H4 mutations that prevented mating were recessive relied upon plasmid-borne copies of the histone genes (23, 34, 42). To rigorously determine if the H4 mutations were indeed recessive, we constructed strains expressing H4-WT and H4-4A histones from single integrated copies of the HHF2 and hhf2-4A genes, respectively (Fig. 2B). In S. cerevisiae, the histone H4 and H3 genes are located on chromosome II (HHF1-HHT1) and chromosome XVI (HHF2-HHT2). The two copies contain several base pair differences but encode identical proteins. The chromosome XVI copies are expressed at five- to seven-fold higher levels than the chromosome II copies (3). In all of the studies described below, we expressed both H4-WT and H4-4A from the HHF2-HHT2 promoter in the same chromosomal context (see Materials and Methods for details). In addition, we constructed strains that contained single integrated copies of either H4-WT or H4-4A as the only source of histone H4 protein (Fig. 2B). These strains were used in all of the subsequent experiments.

Consistent with previous results (42), yeast strains that contained H4-4A as the only histone H4 protein grew very slowly in rich medium, exhibiting a generation time 51 min longer than that of cells carrying only H4-WT (Table 2). This significant increase in doubling time may be caused by a delay in S phase, which has been seen with other histone H4 mutants that affect the acetylation state of the N terminus (35). While heterozygous H4-4A/WT strains grew better than the H4-4A strains, they exhibited a significantly longer doubling time (27 min longer than that of the H4-WT strains; Table 2). Thus, the slow-growth phenotype of strains expressing H4-4A is not strictly recessive, implying that some H4-4A is incorporated into the chromatin in these heterozygous strains.

Yeast cells contain silent chromatin in three genomic domains, i.e., in the silent mating loci (HML and HMR), in the rRNA gene locus, and near the telomeres (30). Homozygous mutations in the N termini of histone H3 or H4 mutants cause derepression of all three silent domains, resulting in a nonmating phenotype (23, 34, 42, 59). To determine the level of silencing at the silent mating loci, we performed quantitative mating assays with the H4-WT, H4-4A, and H4-4A/WT strains. The MATa H4-4A strain (YJB7350) did not mate, presumably because the HMLα silent mating cassette was derepressed (Table 2). As seen previously (42), a MATα H4-4A (YJB7354) strain mated, albeit with reduced efficiency (Table 2), presumably because silencing at HMRa is stronger than at HMLα (3). However, both the MATa H4-WT (YJB7418) and heterozygous MATa H4-4A/WT (YJB7348 and YJB7356) strains mated with equivalent efficiencies (Table 2), indicating that the hhf2-4A allele encoding H4-4A was recessive for mating. This suggests that the silencing achieved by chromatin present at the silent mating cassettes may tolerate the mutant histone H4 protein. Alternatively, it may indicate that mutant H4-4A was excluded from chromatin at the silent mating loci.

The long-term response to alpha factor is another test of heterochromatin integrity. When exposed to alpha factor, wild-type MATa cells arrest in the G1 phase of the cell cycle, forming a single mating projection or shmoo. In contrast, cells that have subtle defects in the maintenance of silent chromatin domains, such as cac1Δ mutants, form multiple mating projections, termed shmoo clusters (7). The multiple projections are thought to form because cells establish, but cannot maintain, silencing at HMLα. To determine if H4-4A/WT strains have problems maintaining silent chromatin, we performed shmoo cluster analysis on H4-4A/WT strains. Like cac1Δ mutants, H4-4A/WT cells produce shmoo clusters in response to alpha factor (Table 2). Furthermore, the level of shmoo cluster formation in H4-4A/WT cells was similar to the level of shmoo cluster formation in cac1Δ cells (7). This suggests that cells expressing both wild-type and mutant histones have defects in the maintenance of silent chromatin at the silent mating cassettes (6). cac1Δ H4-4A/AT cells exhibited an even more severe defect: 37% of the population of the cac1Δ H4-4A/WT cells budded in response to alpha factor (Table 2), implying that they either could not establish or maintain silent chromatin at the silent mating cassette. This result suggests that the single mutant silencing defects are due, at least in part, to independent, nonredundant mechanisms.

Genes placed near the ends of chromosomes exhibit a telomere position effect (TPE): the expression levels of these telomere-adjacent genes are affected by telomeric heterochromatin (58). When a URA3 gene is inserted at the VIIL telomere (12), wild-type strains are able to form colonies on medium lacking uracil and medium that selects against URA3 expression because of the TPE. Medium that contains 5-fluoroorotic acid (5-FOA) (Fig. 3) is metabolized into a cytotoxin by URA3 cells. Serial dilutions of strains expressing the H4-WT, H4-4A, or H4-4A/WT protein and containing URA3 inserted at the VIIL telomere were plated onto medium lacking uracil (SDC−Ura) and onto medium containing 5-FOA (Fig. 3). The H4-WT strain exhibited telomeric silencing, indicated by the formation of colonies on both the SDC-Ura and 5-FOA plates. The cac1Δ strain, which served as a negative control for telomeric silencing (9), did not grow on the 5-FOA plate. The H4-4A/WT strain exhibited a strong defect in telomeric silencing (Fig. 3), yet the defect in silencing was less extreme than in the cac1Δ strain, since the H4-4A/WT strain formed some colonies on the 5-FOA plate. This indicates that telomeric silencing was reduced, but not completely lost, in strains expressing both H4-WT and H4-4A.

FIG. 3.

Strains expressing both H4-WT and H4-4A histone proteins display defective telomeric silencing. Liquid cultures of exponentially growing yeast strains with the indicated genotypes were serially diluted, spotted onto SDC−Ura and 5-FOA plates, and grown for 3 days at 30°C. Strain YJB8002 was used for the H4-WT strain, YJB8003 was used for the cac1Δ H4-WT strain, and YJB8004 was used for the H4-4A/WT strain. Wild-type strains form colonies on both SDC-Ura and 5-FOA plates because of TPE on URA3 expression.

Taken together, these results indicate that the expression of H4-4A histones together with H4-WT histones affects the cellular growth rate and has intermediate effects on silent chromatin function. The fact that the H4-4A/WT strains have a silencing phenotype at telomeres and at the HM loci suggests that some of the H4-4A histone protein is incorporated into silent chromatin. However, the phenotypes of the H4-4A/WT strain are less severe than the phenotypes of the H4-4A strain, suggesting that the mutant protein may be tolerated when present together with wild-type histone H4. An alternative possibility is that mutant histone H4 is partially excluded from silent chromatin.

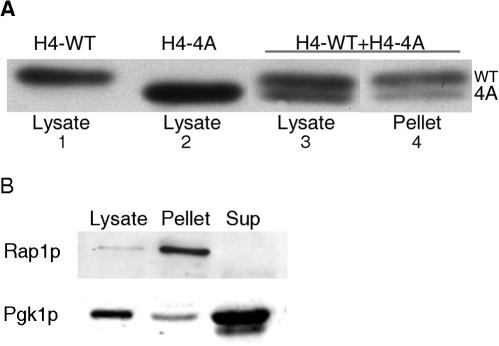

The ratio of H4-WT to H4-4A histones is different in whole cells and nuclei.

Much less H4-4A protein than H4-WT protein was present in nuclear extracts from yeast strains expressing both H4-WT and H4-4A histone proteins from plasmids (Fig. 2A). To analyze the relative amounts of H4-WT and H4-4A histone in cells containing single integrated copies of H4-4A and H4-WT, we compared the levels of the two proteins in WCEs and nuclear extracts from an H4-4A/WT strain (YJB7348). Whole cell lysates from the H4-4A/WT strain contained equivalent amounts of the two histone proteins (Fig. 4A, lane 3). This result implies that when both copies of the histone genes are expressed in a similar promoter context, the mutant histone is not preferentially degraded.

FIG. 4.

The ratio of H4-WT to H4-4A differs in WCEs and nuclear extracts. (A) WCEs (lysates) were prepared from exponentially growing H4-WT (YJB7349), H4-4A (YJB7354), and H4-4A/WT (YJB7348) strains, and extracted nuclear material (pellet) was prepared from the H4-4A/WT strain. Both WCEs and nuclear extracts were separated by SDS-22% PAGE and probed with the anti-H4-17-33 antibody. Note that the H4-4A/WT strain (lane 4) does not contain as much H4-4A protein in the nuclear pellet as in the lysate (lane 3). Quantitation of the amounts of histone H4 present in the nuclear pellet compared to the lysate indicated that 40% of the expected H4-4A is absent in the nuclear pellet. (B) Western blot assay of nucleus-enriched preparations. Lysate, pellet (nuclei), and supernatant (Sup; cytoplasm) material from the nuclear extract protocol were separated by SDS-8% PAGE and probed with either an anti-PGK1 antibody or an anti-RAP1 antibody.

To determine if the equivalent levels of H4-WT and H4-4A histones seen in WCEs were also present in nuclei, we prepared extracts enriched for nuclei from the H4-4A/WT strain (6) and detected the histone proteins with anti-H4-17-33 on immunoblots. As controls for the integrity of the analysis of the nuclear extracts, Rap1p (a transcription factor and telomere binding protein) was found exclusively within the nuclear pellet and Pgk1p (a glycolytic enzyme) was present primarily in the supernatant (Fig. 4B). We did not detect histone proteins by Western analysis of the supernatant with this protocol. This may be because the nuclear extract protocol involves steps that may result in degradation of non-chromatin-associated histone proteins. We also found that approximately 40% of the total H4-4A produced by cells is not present in nuclear preparations. Nuclei from H4-4A/WT consistently contained a higher percentage of H4-WT (71%) than of H4-4A (29%) (Fig. 4A, lane 4; see also Fig. 6). This suggests either that H4-4A/WT cells exclude some of the H4-4A protein from chromatin or from the nucleus or that the association of some of the H4-4A protein is lost during the preparation of nuclear extracts.

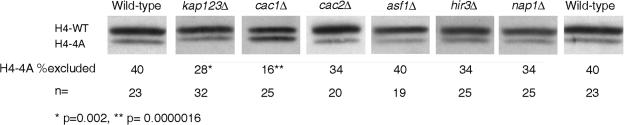

FIG. 6.

Cac1p is responsible for the exclusion of H4-4A histone from chromatin. Nucleus-enriched preparations of exponentially growing wild-type (YJB7348), kap123Δ (YJB8405), cac1Δ (YJB8398), cac2Δ (YJB8817), asf1Δ (YJB8396), hir3Δ (YJB8400), and nap1Δ (YJB8402) cells were separated by SDS-22% PAGE. Western analysis was performed with the anti-H4-17-33 antibody. Densitometry was performed on the indicated number (n) of isolates, and the average amounts of H4-4A excluded from nuclear extracts were calculated. Note the increased amount of H4-4A histone protein in the cac1Δ strain.

H4-4A histone protein is partially excluded from nuclei.

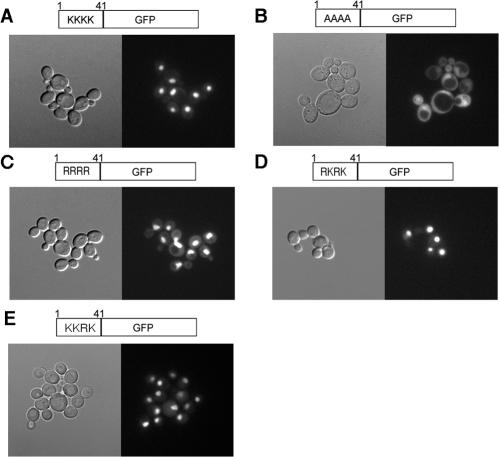

To ask where H4-WT and H4-4A are found in wild-type cells, we used fluorescence microscopy to analyze the localization of H4-WT and H4-4A truncations fused to GFP. Histone H4 contains a nuclear localization sequence in the N-terminal 41 aa (40). We conditionally expressed (from the MET3 promoter) the first 41 aa of histone H4-WT or H4-4A fused in frame to GFP (pH4-WT-GFP and pH4-4A-GFP) (Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

H4-4A-GFP protein is excluded from nuclei. Panels: A, H4-WT-GFP (YJB8342); B, H4-4A-GFP (YJB8343); C, H4-4R-GFP (YJB9012); D, H4-K5,12R-GFP (YJB9011); E, H4-K8R-GFP (YJB9010). Yeast strains containing the indicated GFP fusion proteins were grown overnight at 30°C on solid medium to repress expression of the GFP fusion protein. Cells were then introduced into liquid medium to induce expression of the GFP fusion protein and grown for 6 h at 30°C. Differential interference contrast (left panels) and fluorescence (right panels) micrographs of unfixed cells are shown.

Consistent with previous results (40), the H4-WT-GFP protein localized primarily to the nucleus in wild-type cells (Fig. 5A). In contrast, the H4-4A-GFP protein appeared in both the cytoplasm and the nucleus (Fig. 5B), indicating that it is partially excluded from the nucleus and/or is defective for nuclear localization. These results are consistent with the idea that the acetylation state of the N-terminal lysines of histone H4 is important for the nuclear localization of histone H4.

To further explore the influence of the acetylation state on the nuclear import of histone H4, we generated histone H4-GFP fusion proteins that contained arginine substitutions at the critical lysine residues. Arginine residues carry a permanent positive charge, are not acetylated, and are similar in size to the original lysine residue. To investigate the influence of loss of all four lysine residues, we constructed a quadruple arginine mutant histone H4 N terminus fused to GFP (H4-4R-GFP). Lysine residues at positions 5, 8, and 12 have previously been found to be redundant for nucleosome deposition (32) in vivo. In addition, we generated histone H4 N-terminal mutants that replaced lysine residues 5 and 12 (H4-K5,12R-GFP) or only lysine residue 8 with arginine (H4-K8R-GFP). When these constructs were introduced into wild-type cells, all three constructs localized to the nucleus (Fig. 5C, D, and E). Thus, it appears that the mislocalization of H4-4A-GFP is not simply due to an inability to acetylate the histone H4 N-terminal lysines. Many classic nuclear localization signals, however, contain positively charged residues, including arginine. The increased amount of positive charge due to the arginine substitution may have caused the H4-4R protein to be imported into the nucleus, perhaps through a different import pathway. While we cannot rule out the effect of amino acid side chain size and charge on nuclear import, our results clearly demonstrate that the H4-4A-GFP mutant is ineffectively imported into the nucleus.

Exclusion of mutant histone from chromatin is dependent upon Cac1p.

Cac1p is a histone chaperone in yeast and human cells and, together with Cac2p and Cac3p, is a member of the CAF-1 chromatin assembly complex. Human Cac1p is found in the nucleus during S phase. Upon induction of DNA damage, Cac1p associates with sites of DNA damage in the nucleus (13, 33, 55). No role for Cac1p in histone nuclear import in either yeast or humans has been reported. The phenotypic analysis of H4-4A/WT strains indicated that strains containing both histone proteins had some phenotypes similar to those of cac1Δ mutants. To test the hypothesis that loss of Cac1p may alter the biased exclusion of the H4-4A protein from chromatin, we isolated nuclei and compared the ratio of H4-WT to H4-4A in CAC1 and cac1Δ strains. Immunoblot analysis with anti-H4-17-33 antibody indicated that in nuclear extracts, a larger proportion of chromatin-associated H4-4A histone (relative to that of H4-WT histone) was seen in the cac1Δ H4-4A/WT strains (Fig. 6) than in the CAC1 H4-4A/WT strains. Quantitation of 25 samples demonstrated that the cac1Δ H4-4A/WT strain excluded an average of 16% H4-4A while the CAC1 H4-4A/WT strain excluded 40% H4-4A (P = 1.6 × 10−6; Fig. 6). This effect is specific for cac1Δ cells as neither asf1Δ, hir3Δ, nor nap1Δ mutants affected the ratio of H4-4A to H4-WT in chromatin (Fig. 6). To determine if the exclusion of H4-4A is dependent upon CAF-1 activity, we measured the ratio of H4-WT to H4-4A in a cac2Δ H4-4A/WT strain. Interestingly, the biased exclusion of H4-4A was similar to that in CAC+ strains (Fig. 6), suggesting that the nuclear exclusion of H4-4A depends upon Cac1p but not upon the activity of the CAF-1 complex. Therefore, Cac1p appears to be important for the exclusion of H4-4A from nuclei and chromatin.

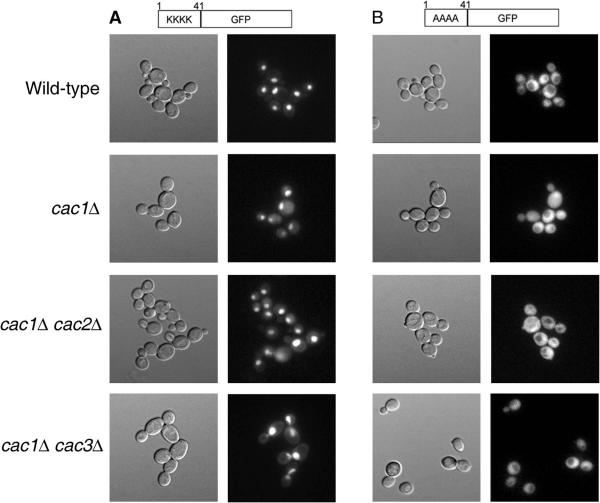

To ask about the role of Cac1p in histone H4 nuclear import, we compared the localization of H4-WT-GFP in wild-type and cac1Δ mutant cells. In general, cac1Δ cells retained most of the H4-WT-GFP in the nuclei although there was a detectable cytoplasmic haze of H4-WT-GFP in almost all of the cac1Δ cells (Fig. 7A). This supports the idea that Cac1p has some effect on the nuclear localization of histone H4.

FIG. 7.

H4-4A-GFP protein is excluded from nuclei in cac1 mutant cells. (A) H4-WT-GFP expressed in wild-type (YJB8342), cac1Δ (YJB8432), cac1Δ cac2Δ (YJB9013), and cac1Δ cac3Δ (YJB9015) cells. (B) H4-4A-GFP expressed in wild-type (YJB8343), cac1Δ (YJB8378), cac1Δ cac2Δ (YJB9014), and cac1Δ cac3Δ (YJB9016) cells. Yeast strains containing the indicated GFP fusion proteins were grown overnight at 30°C on solid medium to repress expression of the GFP protein. Cells were then introduced into liquid media to induce expression of the GFP fusion protein and grown for 6 h at 30°C. Differential interference contrast (left panels) and fluorescence (right panels) micrographs of unfixed cells are shown. Loss of the largest subunit of CAF-1 results in a subtle mislocalization of H4-WT-GFP, while loss of multiple CAF-1 subunits does not further alter the distribution of either H4-WT or H4-4A-GFP.

We also analyzed the localization of H4-4A-GFP in cac1Δ cells. Like the CAC+ cells, much of the GFP signal was cytoplasmic (Fig. 7B). Quantitative scans of 50 to 100 cells of each genotype, however, suggested that the cac1Δ cells had more nuclear H4-4A-GFP signal relative to cytoplasmic GFP than did CAC+ cells (data not shown). This supports the results from the Western analysis of histone H4 proteins from cac1Δ mutants (Fig. 6).

An alternative explanation for the biased exclusion of H4-4A in cac2Δ but not cac1Δ cells could be that the remaining CAF-1 components (i.e., Cac2p and Cac3p in a cac1Δ strain) interfere with H4-4A nuclear import. To test this possibility, we examined the localization of the H4-WT and H4-4A-GFP constructs in cac1Δ, cac1Δ cac2Δ, and cac1Δ cac3Δ strains (Fig. 7). We found that, as in the cac1Δ strain, the H4-WT-GFP construct localized primarily to the nucleus in cac1Δ cac2Δ, and cac1Δ cac3Δ strains (Fig. 7A). In addition, the H4-4A-GFP construct appeared to be mislocalized to a similar extent in cac1Δ, cac1Δ cac2Δ, and cac1Δ cac3Δ strains (Fig. 7B). Therefore, we conclude that the remaining CAF-1 subunits in a cac1Δ strain do not affect the localization of the mutant histone H4 protein.

KAP123 makes a minor contribution to the exclusion of mutant histone H4 from chromatin.

Histone proteins are imported into the nucleus through interactions with several karyopherin proteins (39-41). In the cytoplasm, histones H2A and H2B associate with Nap1p, a putative nucleosome assembly factor, and with the Kap114p, Kap123p, and Kap121p karyopherins (39, 41). In yeast extracts, histone H3/H4 tetramers associate primarily with Kap123p (40). Loss of Kap123p causes histone H3 to become mislocalized from the nucleus while histone H4 localization is less dramatically affected (40).

We analyzed the ratio of chromatin-associated histones H4 in kap123Δ H4-4A/WT strains on immunoblots with the anti-H4-17-33 antibody. We found that kap123Δ cells excluded 28% of the total H4-4A protein (Fig. 6). This is a slight but significant decrease relative to the 40% observed in otherwise wild-type H4-4A/WT cells (P < 0.005, Fig. 6). Thus, Kap123p makes a minor contribution to the biased exclusion of H4-4A from chromatin.

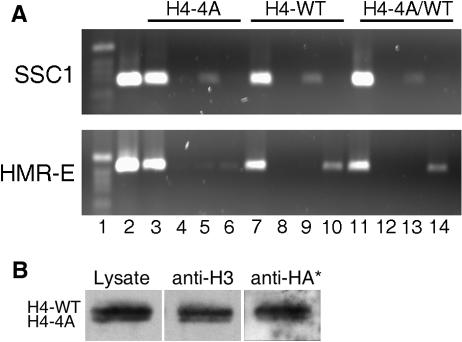

Overall chromatin organization is normal in cells expressing H4-WT and H4-4A histones.

In wild-type strains carrying both the H4-WT and H4-4A proteins, the H4-4A mutant represents roughly 30% of the total histone H4 in chromatin. To determine if this level of H4-4A in chromatin affects the overall chromatin structure, we performed ChIP on active and silent chromatin with strains that contained an integrated copy of SIR3 tagged with the HA epitope. Active chromatin contains mainly acetylated histone proteins, while Sir3p is found within silent chromatin domains. An antibody that recognizes acetylated histone H3 was used to precipitate active chromatin. Silent chromatin was precipitated with an antibody against Sir3-HA. The proportions of active and silent DNA (detected by PCR of SSC1 [active] and HMR-E [silent, Fig. 8A] and of MAT and ACT1 [active, data not shown]) revealed that the acetylated H3-associated and the Sir3p-associated chromatin in the H4-4A strain (Fig. 7A, lanes 3 to 6), the H4-WT/H4-4A strain (Fig. 8A, lanes 11 to 14), and the H4-WT strain (lanes 7 to 10) were similar. Sir3p was specifically associated with silent chromatin (Fig. 8A, HMR-E, lanes 6, 10, and 14), and acetylated H3 was found in active chromatin (Fig. 8A, SSC1, lanes 5, 9, and 13). This indicates that the overall chromatin organization is similar in strains expressing both histone proteins.

FIG. 8.

Overall chromatin organization is similar in cells expressing H4-WT and H4-4A histone H4. (A) ChIP was performed as described in Materials and Methods. Fifteen microliters of each PCR product was analyzed on 1% agarose gels. Lanes: 1, 1-kb DNA ladder; 2, PCR of genomic DNA; 3 to 6, YJB7650 (H4-4A); 7 to 10, YJB7651 (H4-WT);11 to 14, YJB7902 (H4-4A/WT); 3, 7, and 11, PCRs of total immunoprecipitate; 4, 8, and 12, no-antibody control; 5, 9, and 13, immunoprecipitation with anti-acetyl-histone H3; 6, 10, and 14, immunoprecipitation with anti-HA antibody. (B) Protein ChIP. Formaldehyde cross-linked lysates were isolated from the H4-4A/WT strain containing SIR3-HA (YJB8651). Active chromatin was immunoprecipitated with the anti-acetyl-histone H3 antibody; silent chromatin was precipitated with an anti-HA antibody against Sir3-HA. Nuclear extracts (lysates) and immunoprecipitates were separated by SDS-22% PAGE, and Western analysis of histone H4 proteins was performed with anti-H4-17-33 antibody. To detect the histones associated with silent chromatin, the blot, indicated by an asterisk, was exposed approximately 10 times longer than for active chromatin.

To determine if there is a bias in the assembly of the mutant histone protein into either silent or active chromatin, we measured the ratio of the two histone proteins present in active and silent chromatin. For these studies, the ChIP protocol was altered to examine the histone proteins associated with Sir3p and acetylated histone H3. Strains carrying an integrated copy of Sir3-HA were initially used for the protein ChIP experiments, but the amount of precipitated histone proteins was below the level of detection by Western analysis. Therefore, an H4-4A/WT strain that expressed Sir3-HA from a high-copy-number plasmid was constructed to increase silent chromatin precipitation. Lysates from the chromatin preparation still showed a biased exclusion of H4-4A (Fig. 8B), although the extent of the bias was reduced relative to that in nuclear preparations, owing to fixation and extraction conditions. In these studies, the ratios of H4-WT protein relative to H4-4A protein were similar in both silent and active chromatin (Fig. 8B), indicating no bias with respect to the genomic location of H4-4A assembly into chromatin. Since overexpression of SIR3 is known to cause spreading of silent chromatin at HM loci (17), these results may reflect an overestimation of the amount of histone proteins associated with Sir3p. Nonetheless, these results suggest that, despite the partial exclusion of the mutant histone protein from the nucleus, once H4-4A is in the nucleus, it is assembled into all of the regions of the chromatin.

DISCUSSION

Our studies have revealed that replacement of the N-terminal acetylatable lysine residues of histone H4 to alanine results in the partial exclusion of the mutant histone from the nucleus. Interestingly, the biased nuclear exclusion of mutant H4 is dependent upon CAC1 and, to a lesser degree, KAP123 yet does not require CAF-1 activity.

Analysis of the localization of the two H4-GFP proteins and quantitation of the proportion of the H4 mutant proteins in nuclear extracts indicate that in cells expressing H4-WT, the H4-4A protein is partially excluded from the nucleus and chromatin; just over half of the expected amount of mutant protein is present in nuclear extracts (Fig. 4). Thus, cells produce equivalent amounts of H4-WT and H4-4A but the mutant histone is not delivered to the nucleus as efficiently as is the wild-type histone. One possibility is that the H4-A4 protein remains in the cytoplasm in association with Cac1p.

Our studies with plasmid-borne and integrated copies of H4-encoding genes indicate that the original observation that H4 mutations are recessive with respect to the wild type was likely affected by selective pressure against the plasmid-borne mutant histone genes (Fig. 2A). Nonetheless, the mating defect remained recessive in H4-4A/WT strains carrying integrated copies of the two genes that produced equal amounts of protein (Fig. 4A). With strains carrying integrated copies of the two H4 genes, we found that the H4-4A strains were recessive for neither growth nor telomeric silencing (Table 2; Fig. 3). In heterozygous strains expressing both H4-WT and H4-4A, HM silencing is sufficient for mating, yet these strains display subtle silencing phenotypes (Table 2). This is consistent with the phenotypes of other mutations (e.g., loss of CAF-1 components) that have obvious silencing defects at telomeres and weak silencing defects at HML and do not have a large effect on mating as measured by quantitative mating assays (3, 7). Apparently, if HML is silent even for a brief time while a mating partner is available, mating will occur. Importantly, the silencing defects in H4-4A/WT strains imply that some mutant histone is incorporated into the chromatin.

We originally advanced two models to explain the recessive phenotype of mutant histones: either the cells excluded the H4 mutant from the chromatin, or they tolerated the incorporation of the H4 mutant protein into chromatin. Our results emphasize that these two mechanisms are not mutually exclusive; both mechanisms contribute to the phenotypes of H4-4A/WT strains. The H4-GFP constructs clearly demonstrate that the alanine mutant histone H4 protein is found in both the nucleus and the cytoplasm, while the wild-type protein is primarily located in the nucleus (Fig. 5A and B). Our biochemical studies indicate that 40% of the histone H4-4A protein produced in cells is absent in nuclear extracts (Fig. 6). We find that the remaining chromatin-associated H4-4A is sufficient to cause a reduced growth rate and to perturb telomeric silencing, albeit not completely (Fig. 3).

We propose that yeast cells do not import H4-4A protein into the nucleus as efficiently as they import H4-WT. A natural consequence of this import failure is partial exclusion of H4-4A from chromatin. Loss of Cac1p, the largest subunit of CAF-1, eliminates most of this exclusion of the H4-4A protein; in a cac1Δ strain, the amount of H4-4A is similar to the amount of wild-type protein in the nucleus (only 16% of the H4-4A protein produced is excluded from the nucleus) (Fig. 6). This implies that, when present, Cac1p excludes the mutant histone protein from the nucleus. It is tempting to speculate that Cac1p associates with the histone tetramers in the cytoplasm and escorts them into the nucleus, a role similar to that of Nap1p in the import of H2A-H2B dimers (39). Interestingly, this function of Cac1p appears to be independent of CAF-1 activity, as Cac2p is not required for the biased exclusion of H4-4A.

In human cells, Cac1p (p150) associates with newly synthesized histone proteins through an acidic domain located in the central region of the protein that appears to be independent of a Cac2p (p60) interaction domain (25). Taken together, our results suggest that Cac1p functions to exclude the mutant histone, perhaps by sequestering it in the cytoplasm. Cac1p is not visible in yeast when fused to GFP (20), therefore precluding direct analysis of the localization of the CAF-1 complex in H4-4A/WT cells. Consistent with a role for Cac1p independent of the CAF-1 complex, Cac1p, but not Cac2p, has been shown to interact with, and recruit, the SAS-I acetylase complex to regions of newly replicated DNA (36).

In addition to Cac1p, the karyopherin Kap123p makes a small but significant contribution to the partial exclusion of the mutant histone (Fig. 6). Previous work indicated that Kap123p was important for the localization of histone H3, while loss of Kap123p (in the DH5 genetic background) had only a subtle effect on histone H4 localization (40). In our kap123Δ strains (in the W303 genetic background), we observed more dramatic mislocalization of both wild-type and mutant histone H4, as well as cells that were larger and more vacuolated than the isogenic KAP123 strains (data not shown). This difference may be due to the different genetic backgrounds of the strains used in the two studies.

Kap95p is an essential karyopherin that had a subtle impact on histone H2A-H2B nuclear import (41). Interestingly, Cac1p physically interacts with a karyopherin complex including Kap95p and SRP1 (18). The other CAF-1 subunits were not present in this immunoprecipitated complex. While histone proteins were not identified in these complexes, our results support the suggestion that Cac1p may interact with the nuclear import machinery independently of its association with other CAF-1 components.

We do not know with certainty the stoichiometry of H4-WT to H4-4A within a tetramer in the H4-4A/WT strain. However, since the histone fold domain of H4-4A remains intact and since cells carrying H4-4A as the only histone in the cells are viable (Table 2), it is reasonable to assume that H4-4A is able to associate with histone H3 to form H3/H3/H4-4A/H4-4A tetramers. If equal amounts of both H4-WT and H4-4A are present in the cytoplasm, then ∼50% of the total tetramers would have a single wild-type H4 N terminus (H3/H3/H4-WT/H4-4A) while ∼25% of the tetramers would have two copies of H4-4A (H3/H3/H4-4A/H4-4A). One attractive hypothesis is that these H3/H3/H4-4A/H4-4A tetramers are not efficiently imported into the nucleus, perhaps because of sequestration by Cac1p. If they were not imported at all, one would expect that the mutant histone would comprise ∼25% of the total nuclear histone H4. We observed ∼30% H4-4A in the nucleus, which may be due to inefficient sequestration by Cac1p or to other competing activities that have not yet been identified.

Previous work indicated that the N-terminal tails of both histone proteins are not required for chromatin assembly in vitro (52). The cell-free system in which that work was performed, however, could not address the question of nuclear import. Our studies clearly demonstrate that alanine mutations in the N terminus of histone H4 causes a significant proportion of the protein to be cytoplasmic. While the acetylation state of the histone N terminus may not be required for in vitro assembly into chromatin, we propose that the histone H4 N terminus and, most likely, the acetylation state of the lysines in this region and their recognition by Cac1p are important for efficient entry of histones into the nucleus.

Recently, Hif1p, a new yeast CAF that promotes histone H3/H4 tetramer deposition onto chromatin, was reported (2). Furthermore, the type B histone acetylases Hat1p and Hat2p localize to both the cytoplasm and the nucleus and appear to be imported into the nucleus with H3/H4 tetramers, leading to the suggestion that one of the functions of the Hat proteins may be to protect the acetylation state of the histone N termini during nuclear import. We have demonstrated that the acetylatable lysines of the histone H4 N terminus are critical for nuclear import. Since Cac1p and Kap123p only partially account for the nuclear entry of H4-4A, perhaps Hif1p, Hat1p, and/or Hat2p also affect the nuclear localization of wild-type and/or mutant histone H4.

Acknowledgments

We thank R. Kamakaka, P. Kaufman, D. Kellog, D. Gottschling, M. Grunstein, M. Smith, and J. Szostak for yeast strains and plasmids. We thank M. Gerami-Nejad for expert assistance in plasmid and strain construction; M. R. McClellan and K. Finley for expert technical assistance; and E. Hendrickson, A. Bielinsky, D. Kirkpatrick, R. Kamakaka, S. Enomoto, C. Gale, and members of the Berman laboratory for helpful discussions and critiques of the manuscript.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants GM 38626 (J.B.) and F32 GM 63352 (L.G.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Adams, C. R., and R. T. Kamakaka. 1999. Chromatin assembly: biochemical identities and genetic redundancy. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 9:185-190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ai, X., and M. R. Parthun. 2004. The nuclear Hat1p/Hat2p complex: a molecular link between type B histone acetyltransferases and chromatin assembly. Mol. Cell 14:195-205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aparicio, O. M., B. L. Billington, and D. E. Gottschling. 1991. Modifiers of position effect are shared between telomeric and silent mating-type loci in S. cerevisiae. Cell 66:1279-1287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cross, S. L., and M. M. Smith. 1988. Comparison of the structure and cell cycle expression of mRNAs encoded by two histone H3-H4 loci in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 8:945-954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dahlseid, J. N., J. Lew-Smith, M. J. Lelivelt, S. Enomoto, A. Ford, M. Desruisseaux, M. McClellan, N. Lue, M. R. Culbertson, and J. Berman. 2003. mRNAs encoding telomerase components and regulators are controlled by UPF genes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Eukaryot. Cell 2:134-142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Edmondson, D. G., and S. Y. Roth. 1998. Interactions of transcriptional regulators with histones. Methods 15:355-364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Enomoto, S., and J. Berman. 1998. Chromatin assembly factor I contributes to the maintenance, but not the re-establishment, of silencing at the yeast silent mating loci. Genes Dev. 12:219-232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Enomoto, S., L. Glowczewski, J. Lew-Smith, and J. G. Berman. 2004. Telomere cap components influence the rate of senescence in telomerase-deficient yeast cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24:837-845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Enomoto, S., P. D. McCune-Zierath, M. Gerami-Nejad, M. A. Sanders, and J. Berman. 1997. RLF2, a subunit of yeast chromatin assembly factor-I, is required for telomeric chromatin function in vivo. Genes Dev. 11:358-370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fischle, W., Y. Wang, and C. D. Allis. 2003. Histone and chromatin cross-talk. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 15:172-183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Game, J. C., and P. D. Kaufman. 1999. Role of Saccharomyces cerevisiae chromatin assembly factor-I in repair of ultraviolet radiation damage in vivo. Genetics 151:485-497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gottschling, D. E., O. M. Aparicio, B. L. Billington, and V. A. Zakian. 1990. Position effect at S. cerevisiae telomeres: reversible repression of Pol II transcription. Cell 63:751-762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Green, C. M., and G. Almouzni. 2003. Local action of the chromatin assembly factor CAF-1 at sites of nucleotide excision repair in vivo. EMBO J. 22:5163-5174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grunstein, M. 1992. Histones as regulators of genes. Sci. Am. 267:68-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grunstein, M. 1998. Yeast heterochromatin: regulation of its assembly and inheritance by histones. Cell 93:325-328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grunstein, M., A. Hecht, G. Fisher-Adams, J. Wan, R. K. Mann, S. Strahl-Bolsinger, T. Laroche, and S. Gasser. 1995. The regulation of euchromatin and heterochromatin by histones in yeast. J. Cell Sci. Suppl. 19:29-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hecht, A., S. Strahl-Bolsinger, and M. Grunstein. 1996. Spreading of transcriptional repressor SIR3 from telomeric heterochromatin. Nature 383:92-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ho, Y., A. Gruhler, A. Heilbut, G. D. Bader, L. Moore, S. L. Adams, A. Millar, P. Taylor, K. Bennett, K. Boutilier, L. Yang, C. Wolting, I. Donaldson, S. Schandorff, J. Shewnarane, M. Vo, J. Taggart, M. Goudreault, B. Muskat, C. Alfarano, D. Dewar, Z. Lin, K. Michalickova, A. R. Willems, H. Sassi, P. A. Nielsen, K. J. Rasmussen, J. R. Andersen, L. E. Johansen, L. H. Hansen, H. Jespersen, A. Podtelejnikov, E. Nielsen, J. Crawford, V. Poulsen, B. D. Sorensen, J. Matthiesen, R. C. Hendrickson, F. Gleeson, T. Pawson, M. F. Moran, D. Durocher, M. Mann, C. W. Hogue, D. Figeys, and M. Tyers. 2002. Systematic identification of protein complexes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae by mass spectrometry. Nature 415:180-183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoek, M., and B. Stillman. 2003. Chromatin assembly factor 1 is essential and couples chromatin assembly to DNA replication in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:12183-12188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huh, W. K., J. V. Falvo, L. C. Gerke, A. S. Carroll, R. W. Howson, J. S. Weissman, and E. K. O'Shea. 2003. Global analysis of protein localization in budding yeast. Nature 425:686-691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Iizuka, M., and M. M. Smith. 2003. Functional consequences of histone modifications. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 13:154-160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jenuwein, T., and C. D. Allis. 2001. Translating the histone code. Science 293:1074-1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnson, L. M., P. S. Kayne, E. S. Kahn, and M. Grunstein. 1990. Genetic evidence for an interaction between SIR3 and histone H4 in the repression of the silent mating loci in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87:6286-6290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaufman, P. D., J. L. Cohen, and M. A. Osley. 1998. Hir proteins are required for position-dependent gene silencing in Saccharomyces cerevisiae in the absence of chromatin assembly factor I. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18:4793-4806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kaufman, P. D., R. Kobayashi, N. Kessler, and B. Stillman. 1995. The p150 and p60 subunits of chromatin assembly factor I: a molecular link between newly synthesized histones and DNA replication. Cell 81:1105-1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaufman, P. D., R. Kobayashi, and B. Stillman. 1997. Ultraviolet radiation sensitivity and reduction of telomeric silencing in Saccharomyces cerevisiae cells lacking chromatin assembly factor-I. Genes Dev. 11:345-357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kayne, P. S., U. J. Kim, M. Han, J. R. Mullen, F. Yoshizaki, and M. Grunstein. 1988. Extremely conserved histone H4 N terminus is dispensable for growth but essential for repressing the silent mating loci in yeast. Cell 55:27-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kellogg, D. R., and A. W. Murray. 1995. NAP1 acts with Clb1 to perform mitotic functions and to suppress polar bud growth in budding yeast. J. Cell Biol. 130:675-685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Krawitz, D. C., T. Kama, and P. D. Kaufman. 2002. Chromatin assembly factor I mutants defective for PCNA binding require Asf1/Hir proteins for silencing. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22:614-625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Laurenson, P., and J. Rine. 1992. Silencers, silencing, and heritable transcriptional states. Microbiol. Rev. 56:543-560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Longtine, M. S., A. McKenzie III, D. J. Demarini, N. G. Shah, A. Wach, A. Brachat, P. Philippsen, and J. R. Pringle. 1998. Additional modules for versatile and economical PCR-based gene deletion and modification in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 14:953-961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ma, X. J., J. Wu, B. A. Altheim, M. C. Schultz, and M. Grunstein. 1998. Deposition-related sites K5/K12 in histone H4 are not required for nucleosome deposition in yeast. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:6693-6698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Martini, E., D. M. Roche, K. Marheineke, A. Verreault, and G. Almouzni. 1998. Recruitment of phosphorylated chromatin assembly factor 1 to chromatin after UV irradiation of human cells. J. Cell Biol. 143:563-575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Megee, P. C., B. A. Morgan, B. A. Mittman, and M. M. Smith. 1990. Genetic analysis of histone H4: essential role of lysines subject to reversible acetylation. Science 247:841-845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Megee, P. C., B. A. Morgan, and M. M. Smith. 1995. Histone H4 and the maintenance of genome integrity. Genes Dev. 9:1716-1727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Meijsing, S. H., and A. E. Ehrenhofer-Murray. 2001. The silencing complex SAS-I links histone acetylation to the assembly of repressed chromatin by CAF-1 and Asf1 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genes Dev. 15:3169-3182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mello, J. A., H. H. Sillje, D. M. Roche, D. B. Kirschner, E. A. Nigg, and G. Almouzni. 2002. Human Asf1 and CAF-1 interact and synergize in a repair-coupled nucleosome assembly pathway. EMBO Rep. 3:329-334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Meluh, P. B., P. Yang, L. Glowczewski, D. Koshland, and M. M. Smith. 1998. Cse4p is a component of the core centromere of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Cell 94:607-613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mosammaparast, N., C. S. Ewart, and L. F. Pemberton. 2002. A role for nucleosome assembly protein 1 in the nuclear transport of histones H2A and H2B. EMBO J. 21:6527-6538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mosammaparast, N., Y. Guo, J. Shabanowitz, D. F. Hunt, and L. F. Pemberton. 2002. Pathways mediating the nuclear import of histones H3 and H4 in yeast. J. Biol. Chem. 277:862-868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mosammaparast, N., K. R. Jackson, Y. Guo, C. J. Brame, J. Shabanowitz, D. F. Hunt, and L. F. Pemberton. 2001. Nuclear import of histone H2A and H2B is mediated by a network of karyopherins. J. Cell Biol. 153:251-262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Park, E. C., and J. W. Szostak. 1990. Point mutations in the yeast histone H4 gene prevent silencing of the silent mating type locus HML. Mol. Cell. Biol. 10:4932-4934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Parthun, M. R., J. Widom, and D. E. Gottschling. 1996. The major cytoplasmic histone acetyltransferase in yeast: links to chromatin replication and histone metabolism. Cell 87:85-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Robinson, K. M., and M. C. Schultz. 2003. Replication-independent assembly of nucleosome arrays in a novel yeast chromatin reconstitution system involves antisilencing factor asf1p and chromodomain protein chd1p. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23:7937-7946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rose, M. D., F. Winston, and P. Hieter. 1990. Methods in yeast genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 46.Rusche, L. N., and J. Rine. 2001. Conversion of a gene-specific repressor to a regional silencer. Genes Dev. 15:955-967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sharp, J. A., E. T. Fouts, D. C. Krawitz, and P. D. Kaufman. 2001. Yeast histone deposition protein Asf1p requires Hir proteins and PCNA for heterochromatic silencing. Curr. Biol. 11:463-473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]