Abstract

Objective

This study aimed to gather qualitative feedback on patient perceptions of informed consent forms and elicit recommendations to improve readability and utility for enhanced patient safety and engagement in shared decision making.

Methods

Sixty in person interviews were conducted consisting of a literacy and numeracy assessment, a comprehension quiz to assess retention of key information and open ended questions to determine reactions, clarity of information and suggestions for improvement.

Results

While 68% of the participants had education beyond high school, many still missed comprehension questions and found the forms difficult to read. Recurrent suggestions included: specific formatting changes to enhance readability, a need for additional sources of information, mixed attitudes towards inclusion of risk information and the recognized importance of physician-patient conversations.

Conclusion

This study provides evidence from the patient perspective that consent forms are too complex and fail to achieve comprehension. Future studies should be conducted using patients’ suggestions for form redesign and inclusion of supplemental educational tools in order to optimize communication and safety to achieve more informed health care decision making.

Keywords: Informed Consent, Patient Perspective, Health Literacy, Patient Safety

Introduction

Despite their ethical and legal importance, informed consents for medical and surgical procedures can be barriers to engaging patients in the shared decision making process1. A signature on a consent form indicates that the patient has had a detailed conversation with their provider and that the patient understands the purpose, benefits, risks and alternatives of the treatment they are receiving1,2. However, consent forms frequently fail to convey any knowledge because they are too complex for the average patient with a low literacy level and risk information is often subjectively interpreted 3,4.

Previous studies report that interventions with decision aids or reformatting can increase the likelihood that patients will read the forms and understand their content. Providing additional materials such as videos,5 personalized worksheets,1 take-home information sheets6, illustrations or diagrams2, incorporating test/feedback questions3,7 and formatting changes to create easy to read versions8 have all been cited as means to improve comprehension for patients with both high and low literacy. Furthermore, numerical presentation rather than relative risk categories and incorporation of graphical representations may facilitate more accurate risk perceptions and improve risk communication between providers and patients9,10. Even though the literature contains a wide scope of recommendations for enhancing form readability and tailoring risk information, limited studies obtain patient input on these suggestions; majority of studies focus on patient recall and comprehension11. Only two papers7,12 produced from the same study site were found to directly measure patient anxiety and satisfaction and elicit patient perceptions with an informed consent process.

Given that consent forms are intended to be read by patients, their opinions on formatting, style and content should be solicited and incorporated into best practice methods to enhance safety and risk management while facilitating patients taking an active role in shared decision making. This study examines patient understanding of information presented in currently used clinical consent forms at two large teaching hospitals and elicits patient input on alterations via detailed interviews. The aim was to gather qualitative feedback on what patients perceive as the most challenging to understand, what type of additional materials would provide the greatest assistance and any desire for inclusion of risk information. This information is vital for clinicians who are responsible for ensuring that the informed consent process achieves its intended goals.

Methods

Study Sample and Setting

Sixty patients and family members were recruited from surgical, maternity and general medicine clinic waiting rooms at two hospitals in an independent academic health system in Delaware from June 2014 – August 2014. Christiana Hospital is a 913 bed suburban teaching hospital and Wilmington Hospital is a 241 bed urban teaching hospital. Participants had to be at least 21 years old and able to read and speak English. All participants signed a consent form to participate in the study that was approved by the Christiana Care Health System Institutional Review Board.

Form Selection and Analysis

The following 5 consent forms were used: Consent for Procedure, Consent for Procedures in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU), Consent for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, Consent for Peripherally Inserted Central Catheter (PICC) and Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU) Consent for Admission, Medical Treatment and Procedures. These forms were chosen because they are frequently utilized at the study site and they represent variation in formatting style and amount of information as seen in Appendix 1.

Form readability was assessed using the SMOG Readability Test and the Fry Readability Scale, which were completed manually and by the Health Literacy Advisor Microsoft Word Add-In. The SMOG readability test estimates the years of education a person needs to understand a piece of writing based on percentage of polysyllabic words13. The Fry Readability Scale determines reading level based on average number of syllables and sentences per 100 words14. Numerical information was intended to be coded using a conceptual model described by Apter and colleagues15. However, none of the included consent forms nor any of the commonly used forms in the study site’s health system contained numerical information.

Patient Interview Structure

All responses were gathered anonymously and coded upon data entry. An interview script is included in Appendix 2. Interviews lasted approximately 15 minutes and were conducted by 2 research assistants.

Demographic Survey: Patients were asked to circle appropriate responses for age, gender, race/ethnicity and education

Literacy Assessment: Health literacy was measured using the Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine Short Form (REALM-SF), a validated 7-item word recognition test. This test was chosen because of the simplicity of administration within the patient interview while still being highly accurate16, 17.

Numeracy Assessment: The self-reported Subjective Numeracy Scale (SNS) was used to assess patient numerical ability and preferences18. The SNS is both reliable and highly correlated with the Lipkus, Samsa & Rimer numeracy measure, and has been validated as efficient in risk communication18. Previous studies indicate scores between 4 and 5 (out of a possible 6) are average while scores below 4 indicate low numeracy, low ability and preference for words over numerical information19,20.

Comprehension Quiz: Participants were given 1 of the 5 consents at random and asked to read it, taking as much or as little time as needed. The primary research assistant asked 3 comprehension quiz questions and the secondary research assistant recorded the participant’s responses as correct or incorrect. As detailed in Appendix 3, the questions asked about procedure details, treatment options, possible risks and legal rights of the hospital. The questions were modeled on a questionnaire used in a previous study and evaluated understanding of ethically essential content1,6. The order of the questions matched the order of information within the form. Patients were permitted to use the form to find the correct answers. If a patient could not find the answer or was not sure of the answer, “I don’t know” was recorded as the response.

Open Ended Questions: The primary research assistant asked open ended questions addressing general reaction to the form, identification of confusing words or medical terms, identification of any part of the form that appeared easier to read, any proposed changes, possible questions for the doctor after reading the form, and any preference for receiving additional information in a variety of formats. Both the primary and secondary research assistants recorded the participants’ responses that were subsequently compared to ensure documentation completeness.

Outcomes and Analysis

Responses to the open ended questions were coded and grouped into categories of common themes by the primary research assistant for all 60 interviews. Literacy and numeracy assessment scores were compared to scores on the comprehension quiz questions and responses to open ended questions.

Results

A total of 62 patients were recruited and signed a consent to participate in an interview. Two participants were unable to complete the interview and none of their information was included in the results. Demographic information, literacy scores and numeracy assessment results are in Table 1 for all 60 completed interviews.

Table 1.

Patient Demographics (N=60)

| Gender | |

| Male | 19 (32%) |

| Female | 41 (68%) |

|

| |

| Education | |

| Less than high school | 0 (0%) |

| High school degree or equivalent | 19 (32%) |

| Some college, no degree | 18 (30%) |

| Associate degree | 4 (7%) |

| Bachelor degree | 10 (17%) |

| Graduate degree | 9 (15%) |

|

| |

| Race | |

| White | 45 (75%) |

| African American | 11 (18%) |

| Native American | 1 (2%) |

| Asian | 0 (0%) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 1 (2%) |

| Other | 2 (3%) |

|

| |

| Age | |

| 20–29 | 2 (3%) |

| 30–39 | 6 (10%) |

| 40–49 | 9 (15%) |

| 50–59 | 27 (45%) |

| 60–69 | 12 (20%) |

| 70+ | 4 (7%) |

|

| |

| Literacy Level | |

| 3rd grade and below | 0 (0%) |

| 4th – 6th grade | 1 (2%) |

| 7th – 8th grade | 11 (18%) |

| High school | 48 (80%) |

|

| |

| Numeracy Level | |

| Total score below average | 13 (22%) |

| Ability score below average | 21 (35%) |

| Preference for words over numbers | 16 (27%) |

Despite differences in format and amount of information, all the forms were at a college reading level by both SMOG and Fry assessments.

Comprehension quiz

Quiz results by literacy level are included in Table 2. Forty-six percent (22/48) of participants at a high school literacy level and 64% (7/11) of participants at a seventh-eighth grade literacy level missed one or more questions. The Consent for Procedure was the shortest form and had the high percentage of participants answer all three questions correctly. Consent for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy was the only form to be 2 pages in length and had the highest percentage of participants miss one or more questions. Participants missed all types of content questions, including those concerning the nature of the procedure, possible complications and legal permissions of the hospital.

Table 2.

Comprehension Quiz Results by Literacy Level

| All Correct | Missed One | Missed Two | Missed Three | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High School (n= 48) | 25 (52%) | 18 (38%) | 3 (6%) | 1 (2%) |

| 7th – 8th grade (n=11) | 2 (18%) | 6 (55%) | 1 (9%) | 0 (0%) |

| 4th– 6th grade (n=1) | 1 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

Open Ended Questions

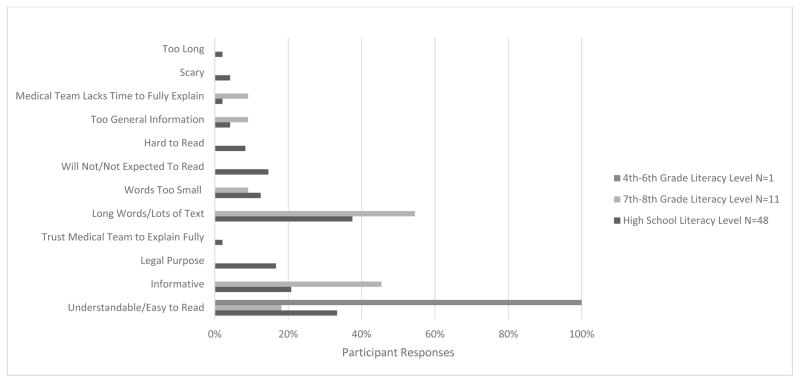

Based on common answers, the general reaction responses were grouped into 12 categories of which 8 were negative, 2 were neutral (legal purpose, trust medical team to fully explain) and 2 were positive (understandable/easy to read, informative) as seen in Figure 1. More than half (55%, 6/11) of the participants at a seventh-eighth grade literacy level thought the form had long words/lots of text. Negative responses of scary (4%, 2/48), will not read/not expected to read (15%, 7/48), too long (2%, 1/48) and hard to read (8%, 4/48) were received from high school literacy level participants exclusively. The participant at a fourth-sixth grade literacy level only positively responded that the form was understandable/easy to read.

Figure 1.

General Reaction to Consent Form by Literacy Level

Fifty-eight percent (35/60) of all participants believed the forms contained confusing words most of which were medical terms and procedure names such as fluoroscopy, pneumothorax and endotracheal incubation. When asked what changes could be made to improve the forms, participants most commonly gave suggestions for formatting changes such as bullets (72%, 43/60), larger font (70%, 42/60) and highlighting/bolding section headings and key terms (55%, 33/60).

When asked if the participant would have any additional questions for the doctor after reading the form 43% (26/60) said yes. Participants at a high school literacy level were more likely to have specific questions (46%, 22/48) compared to participants at a lower level (25%, 3/12).

Regarding risk information, 52% (31/60) of the respondents preferred risks grouped by severity or frequency. 35% (21/60) wanted risk percentages included in the forms. The average SNS score of patients wanting more risk information was not different than that of patients not wanting more risk information (4.6 versus 4.4). Fear of too much information was the reason most cited for not including risk percentages within the form. Of the participants who had additional questions for the doctors, 35% (9/26) were concerning risk information.

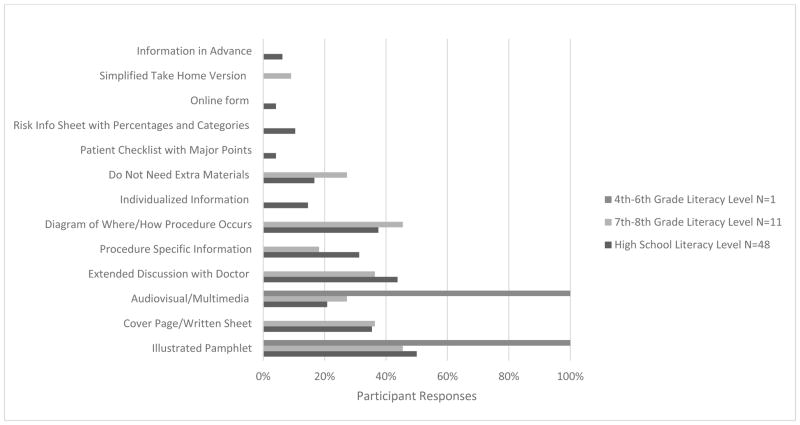

Preferences for sources of additional information by literacy level are detailed in Figure 2. Eighty-two percent (49/60) of participants felt it would be beneficial to have an additional source of information. Illustrated pamphlets and diagrams were most commonly requested by all literacy levels, high school literacy 50% (24/48), seventh and eight grade 45% (5/11) and fourth to sixth grade 100% (1/1). Requesting an extended conversation with the doctor was the second most common response for participants at high school (44%, 21/48) and seventh-eighth grade (36%, 4/11) literacy levels.

Figure 2.

Desire for Additional Sources of Information by Literacy Level

Discussion

This study generated valuable feedback on patient comprehension, preferences and attitudes across different literacy levels towards the informed consent process. While the literature is rich with evidence that consent forms fail to achieve their intended purpose, this study is unique in eliciting patient perspectives to learn more specifically why consent forms are ineffective and how the process could be improved for patients at both high and low literacy levels in order to reduce risks and improve care.

The majority of study participants had a negative reaction towards the forms revealing a discouraging lack of user-friendliness. Only half of the participants with a degree in higher education correctly answered all the comprehension quiz questions indicating that this group was unable to assimilate the information. These poor findings correspond with those of a recent review including 13 studies, reporting 21–81% comprehension of treatment risks and benefits to indicate that understanding can be limited even among patients who have high literacy levels11.

A concerning finding was that low literacy may prevent patients from feeling confident to ask any questions at all. Although they found the forms dense and confusing, it was rare that low literacy patients gave specific examples of questions they wanted to ask their doctor. Consequently, low literacy patients may defer to the clinician’s knowledge, relying primarily on explanations provided by physicians when making decisions21. Especially in busy offices, it is not uncommon for clinicians to accept this decision deferral without encouraging the patient to voice opinions or concerns22. Physicians also may unintentionally influence a patient by providing selective information or inappropriately emphasizing or deemphasizing information23. When low literacy hinders open lines of bilateral communication and patient safety is compromised, then the patient is prevented from accurately weighing the pros and cons of a medical decision and is left vulnerable to physician biases24.

Independent of literacy level, patients gave four recurring recommendations for improving the forms and the consent process: specific formatting changes to enhance readability, a need for additional sources of simplified information, mixed attitudes towards inclusion of risk information, and the recognized importance of physician-patient conversations. While these recommendations have been previously described1,2, 5,6,8,9,10 the direct patient feedback solicited in this study enhances the evaluation these interventions as essential in addressing patient voiced issues with failures of the informed consent process.

Many patients expressed that when handed a document with large blocks of texts and small font with little expectation from the medical staff for patients to take time to read the entire form, patients will skim the document and sign without asking questions25. To make the forms more readable, both high and low literacy patients asked for more white space, bulleted lists, shorter blocks of text, bolded section headings and larger font, similar to “reader-friendly” versions previously described8. By utilizing bulleted lists under highlighted or bolded section headings, the forms could better serve as guidelines facilitating patient-physician discussion and optimizing education and risk management rather than dense legal documents receiving no attention beyond a signature1.

To further enhance accessibility, patients with both high and low literacy expressed a desire for extra educational information to be provided separately from consent forms. Many felt that offering a simplified supplemental clarification tool, such as a video, diagram or illustration, geared towards education and developed without the legal constraints of a consent form would be highly beneficial. Such decision aids focused on education have been shown to increase patient knowledge of options and outcomes, further encourage patients to take a more active role in the decision making process and reduce decisional conflict26. For instance in a recent study, patients who watched a video describing the procedure, risks, benefits and alternatives developed at a seventh grade reading level prior to signing a surgical consent form had significantly improved comprehension compared to patients who only received information verbally5. The comprehension benefits were even greater in patients with low literacy indicating that simplified supplemental tools have the potential to improve safety and quality of care for patients experiencing the most difficulty with complex forms.

These benefits could be further increased by providing more information prior to hospital arrival, which was an option that many participants expressed an interest in22,24. Clinical teams may be uncertain how to incorporate these tools into the consent process or may believe they do not have the time or training to use the tools22. Certification of decision aids will require legislative guidelines to instill confidence in patients and clinicians that the tools are unbiased, comprehensive, accurate, and as up-to-date as possible27. Given the demonstrated value and patient demand for additional sources of information as found in this study, overcoming these barriers should be a priority in delivering safe and effective patient centered care.

A third pattern was mixed attitudes toward inclusion of numerical risk information. Some patients felt that “less is more” when it comes to risk information. Believing that percentages would be scary or overwhelming, patients often expressed that such information should be available by request on a separate information sheet. Some patients only wanted to know which risks were most relevant to them based on preexisting conditions or individual circumstance. While patients believed that individualized risks would be too complex to convey, it is becoming possible. In a study that improved consent forms for invasive cardiac treatment, patient-specific estimates of risk were determined from validated models and included in the forms28. Even if risks can be tailored to the individual, communication challenges remain for physicians who have little formal training in presenting probabilities and risk information29. Physicians should be mindful of a patient’s emotions or personal experiences skewing interpretations of subjective descriptive terms such as “low risk”10. Due to mixed patient attitudes, more research is needed to determine how to best include risk information within consent forms in a manner that is most beneficial.

Finally, this study indicates that patients recognize that the informed consent process should go beyond signing a form. Regardless of any additional decision aids, patients trust their physicians to communicate the most important and relevant information in an individualized conversation30. Different interventions have mixed degrees of impact on patient comprehension2 and thus caution must be taken to ensure that a detailed conversation to the patient’s satisfaction is not displaced by additional interventions and tools.

This study represents a first step towards modifying the informed consent process to meet patient expectations. Currently, informed consent is intended to legally protect patients and ethically support patient-defined goals and autonomous decision making11. Requirements on which situations require a full consent and how much information physicians are expected to disclose varies among state legislatures and institutions creating grey areas and documentation failure31. To truly empower patients, the informed consent process should incorporate shared decision making, requiring a clinical culture change and physician input24. Future studies are needed to further evaluate the patient viewpoint and to expand knowledge of best practices for implementing decision aids and enhancing risk communication.

The study did have limitations. Given the short duration of the study, the sample size is small. However, the study captured the diverse demographic that our hospital network serves, making the results generalizable to other urban and suburban hospital settings. While the majority of patients interviewed (80%) had a high school literacy level and the results might not be reflective of preferences of lower literacy patients, the results provide valuable insights of tendencies lower literacy patients to under-participate in the consent process. Most participants were unlikely to have prior knowledge of the procedure or condition related to the consent form they were given. In real life situations, patients often have a baseline knowledge or have done research on their condition which could improve familiarity with the information in the form and improve ability to ask appropriate questions. Conversely, in the low stress hypothetical interview situation, participants may have had improved comprehension of the form than when under real life high stress situations. Finally, majority of patients easily completed the multi step interview but some felt rushed or did not wish to continue. If the interviews were conducted in a more private area, participants might have felt more comfortable taking time to answer the questions.

Conclusion

This study provides evidence that consent forms are too complex and fail to achieve comprehension from the patient perspective. Ideally, the consent process allows for shared decision making by incorporating current evidence-based physician knowledge with patient preferences. Future studies should be conducted using patients’ suggestions for form redesign and inclusion of supplemental simplified educational tools in order to optimize communication and safety to achieve well informed health care decision making.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funders: This project was supported by the Delaware INBRE program, with a grant from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences - NIGMS (8 P20 GM103446-13) from the National Institutes of Health.

Prior presentations: Results from this study were presented as a poster in October 2015 at the Society of Medical Decision Making 37th Annual North American Meeting in St. Louis, MO.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest:

None

References

- 1.Bottrell MM, Alpert H, Fischbach RL, Emanuel LL. Hospital informed consent for procedure forms: facilitating quality patient-physician interaction. Archives of Surgery. 2000;135(1):36–33. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.135.1.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schenker Y, Fernandez A, Sudore R, Schillinger D. Interventions to Improve Patient Comprehension in Informed Consent for Medical and Surgical Procedures: A Systematic Review. Med Decision Making. 2011;31(1):151–173. doi: 10.1177/0272989X10364247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matiasek J, Wynia MK. Reconceptualizing the Informed Consent Process at Eight Innovative Hospitals. The Joint Commission Journal of Quality and Patient Safety. 2008;34(3):127–137. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(08)34015-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lloyd AJ. The Extent of patients’ understanding of the risk of treatments. Quality in Health Care. 2001;10(Suppl I):i14–i18. doi: 10.1136/qhc.0100014... [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rossi M, McClellan R, Chou L, Davis K. Informed Consent for Ankle Fracture Surgery: Patient Comprehension of Verbal and Videotaped Information. Foot and Ankle International. 2004;25(10):756–762. doi: 10.1177/107110070402501011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clark K, O’Loughlin P, Cashman J. Standardized Consent: The Effect of Information Sheets on Information Retention. J Patient Saf. 2015;00:00–00. doi: 10.1097/PTS.0000000000000230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fink AS, et al. Enhancement of Surgical Consent by Addition of Repeat Back: A Multicenter, Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. Ann Surg. 2010;252:27–36. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181e3ec61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lorenzen B, Melby CE, Earles B. Using Principles of Health Literacy to Enhance the Informed Consent Process. AORN Journal. 2008;88(1):23–29. doi: 10.1016/j.aorn.2008.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Waldron CA, van der Weijden T, Ludt S, Gallacher J, Elwyn G. What are effective strategies to communicate cardiovascular risk information to patients? A systematic review. Patient Education and Counseling. 2011;82:169–181. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paling J. Strategies to Help Patients Understand Risks. Boston Medical Journal. 2003;327(7417):745–748. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7417.745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sherlock A, Brownie S. Patients’ recollection and understanding of informed consent: A literature review. ANZ J Surg. 2014;84(4):207–210. doi: 10.1111/ans.12555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Prochazka AV, et al. Patient Perceptions of Surgical Informed Consent: Is Repeat Back Helpful or Harmful? J Patient Saf. 2014;10:140–145. doi: 10.1097/PTS.0b013e3182a00317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McLaughlin GH. SMOG grading: A new readability formula. Journal of Reading. 1969;12(8):639–646. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fry F. Fry’s Readability Graph: Clarification, Validity and Extension to Level 17. Journal of Reading. 1977;21(3):242–252. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Apter AJ, Paasche-Orlow MK, Remillard JT, et al. Numeracy and Communication with Patients: They Are Counting on Us. J Gen Internal Medicine. 2008;23(12):2117–2124. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0803-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arozullah AM, Yarnold PR, Bennett CL, et al. Development and Validation of a Short-Form, Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine. Medical Care. 2007;45(11):1026–1033. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3180616c1b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Health Literacy Measurement Tools: Fact Sheet. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; Rockville, MD: Jan, 2009. http://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/quality-patient-safety/quality-resources/tools/literacy/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fagerlin A, Zikmund-Fisher BJ, Ubel PA, Jankovic A, Derry HA, Smith DM. Measuring numeracy without a math test: Development of the Subjective Numeracy Scale (SNS) Medical Decision Making. 2007;27:672–680. doi: 10.1177/0272989X07304449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zikmund-Fisher BJ, Smith DM, Ubel PA, Fagerlin A. Validation of the subjective numeracy scale (SNS): Effects of low numeracy on comprehension of risk communications and utility elicitations. Medical Decision Makin. 2007;27:663–671. doi: 10.1177/0272989X07303824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McNaughton CD, Collins SP, Kripalani S, et al. Low Numeracy Is Associated With Increased Odds of 30-Day Emergency Department or Hospital Recidivism for Patients With Acute Heart Failure. Circulation: Heart Failure. 2013;6(1):40–46. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.112.969477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Godwin Y. Do they listen? A review of information retained by patients following consent for reduction mammoplasty. Br J Plast Surg. 2000;53:121–125. doi: 10.1054/bjps.1999.3220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Coulter A, Collins A. Making Shared Decision-Making a Reality. London: King’s Fund; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Terry PB. Informed Consent in Clinical Medicine. Chest Journal. 2007;131(2):563–568. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-1955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moulton B, King JS. Aligning Ethics with Medical Decision-Making: The Quest for Informed Patient Choice. Journal of Law and Medical Ethics. 2010;38(1):85–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720X.2010.00469.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.King J, Moulton B. Group Health’s Participation in a Shared-Decision-Making Demonstration Yielded Lessons, Such as Role of Culture Change. Health Affairs. 2013;32(2):294–302. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.O’Connor AM, Rostom A, Fiset V, et al. Decision Aids for Patients Facing Health Treatment or Screening Decisions: Systemic Review. British Medical Journal. 1999;319:731–734. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7212.731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shafir A, Rosenthal J. Shared Decision Making: Advancing Patient-Centered Care Through State and Federal Implementation. Boston, MA: Informed Medical Decisions Foundation; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Arnold SV, Decker C, Ahmad H, et al. Converting the Informed Consent Form a Perfunctory Process to an Evidence Based Foundation for Patient Decision Making. Circulation Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes. 2008;1(1):21–38. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.108.791863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.King JS, Moulton BW. Rethinking Informed Consent: The Case for Shared Medical Decision Making. American Journal of Law & Medicine. 2006;32(4):429–501. doi: 10.1177/009885880603200401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miller MJ, Ann Abrams Mary, Earles B, et al. Improving Patient-Provider Communication for Patients Having Surgery: Patient Perceptions of a Revised Health Literacy Based Consent Process. J Patient Saf. 2011;7:30–38. doi: 10.1097/PTS.0b013e31820cd632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fleisher L, Raivitch S, Miller S, et al. A Practical Guide to Informed Consent. [Accessed January 1, 2014];Temple Health. n.d http://www.templehealth.org/ICTOOLKIT/html/ictoolkitpage1.html.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.