Abstract

Human matrix attachment regions (MARs) can insulate transgene expression from chromosomal position effects in Drosophila melanogaster. To gain insight into the mechanism(s) by which chromosomal insulation occurs, we studied the expression phenotypes of Drosophila transformants expressing mini-white transgenes in which MAR sequences from the human apoB gene were arranged in a variety of ways. In agreement with previous reports, we found that a single copy of the insulating element was not sufficient for position-independent transgene expression; rather, two copies were required. However, the arrangement of the two elements within the transgene was unimportant, since chromosomal insulation was equally apparent when both copies of the insulator were upstream of the mini-white reporter as when the transcription unit was flanked by insulator elements. Moreover, experiments in which apoB 3′ MAR sequences were removed from integrated transgenes in vivo by site-specific recombination demonstrated that MAR sequences were required for the establishment but not for the maintenance of chromosomal insulation. These observations are not compatible with the chromosomal loop model in its simplest form. Alternate mechanisms for MAR function in this system are proposed.

Matrix attachment regions (MARs) are specialized DNA sequences that are thought to play a role in the organization of eukaryotic chromatin by virtue of their interactions with proteins of the nuclear matrix (22, 30). MARs are abundant in eukaryotic genomes, occurring every ∼30 to 100 kb (27); they vary in size from several hundred base pairs to >10 kb, and they are conserved among eukaryotic species. This conservation of function has been demonstrated by showing that nuclear matrix proteins from one species can bind MARs from other organisms in vitro (11). MARs do not have simple consensus binding sites for nuclear matrix proteins, but they do share a number of sequence motifs, such as AT-rich tracts, curved and bent DNA motifs, origins of replication, and topoisomerase II binding sites (2), that may be involved in matrix binding. These common motifs have been used to design algorithms for predicting the locations of putative MARs within genomic DNA sequences (9, 35). These methods for MAR mapping have been used with various degrees of success in silico (9, 25, 26).

Another important feature of MARs is that they are often composed largely of repetitive DNA elements (33). This suggests that DNA secondary structure may be a primary determinant of matrix binding. This hypothesis is consistent with observations that several nuclear matrix proteins, including topoisomerase II (10, 14, 37) and the T-cell-specific MAR-binding protein, SATB1 (6), recognize aspects of DNA secondary structure. SATB1 seems to regulate gene expression in a tissue-restricted manner by binding to ATC tracts that have a propensity to create regions containing unpaired bases. The importance of DNA secondary structure over specific base recognition by proteins that are conserved through evolution may explain how MARs can function across species in the absence of primary sequence conservation.

In addition to the structural roles that MARs are thought to play in organizing eukaryotic chromatin, a variety of studies indicate that MARs may be involved in the regulation of gene expression. Transgenes containing MARs are often expressed at higher, more consistent levels than transgenes without MARs when they are integrated into host cell chromatin by stable transfection (13, 28, 41, 42) or retroviral transduction (32). These observations suggested that MARs might be able to insulate integrated transgenes from chromosomal position effects in vivo. To test this possibility directly, we used the mini-white position effect assay of Kellum and Schedl (16) to demonstrate that human MARs can insulate transgenes from position effects in Drosophila (24). We investigate here the mechanisms of this apparent insulation, and we show that MARs are required for the establishment but not the maintenance of chromosomal insulation. Models for this unusual genetic behavior are discussed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Construction of transformation vectors.

All of the P-element transformation vectors used in the present study are derivatives of mwS′ or EmwS′, which were originally provided by Paul Schedl under the names ΔXS and RW, respectively (39). The construction of the derivative P-element vectors apoB3′MmwS′ and apoB3′Mmw has been described (24). ApoB3′Mmw3′ and apoB3′3′Mmw were generated via a multistep process as follows. First, mwS′ was digested with EcoRI, PvuII, and SalI to remove the mini-white cassette and the scs′ element from the pBluescript backbone and the 5′ and 3′ P-element ends. Second, an EcoRI fragment containing the mini-white cassette and the upstream polylinker was ligated to the plasmid containing the two P-element ends at a unique EcoRI site. This generated mw, which is the P-element vector containing the mini-white cassette flanked by EcoRI sites. Third, P-element vectors with either the mini-white cassette flanked by apoB 3′ MARs at both ends (apoB3′Mmw3′) or with two apoB 3′ MARs at the 5′ end (apoB3′3′Mmw) were created by ligating EcoRI fragments containing apoB 3′ MARs to an EcoRI partial digest of the mw vector. The orientations of apoB 3′ MARs were determined by restriction analysis.

MARFRT, the vector used to study the effects of removing the apoB 3′MAR from integrated mini-white transgene constructs in vivo, was made by blunt-end ligation of the apoB 3′ MAR/FRT HincII fragment from pFRT3′MAR into the unique XbaI site of mwS′. pFRT3′MAR was generated by blunt-end ligation of the apoB 3′ MAR XhoI fragment (18) into the HpaI site of pGEM-FRT-2 (40); this HpaI site is located between two FLP sequences that are flanked by HincII sites.

Drosophila transformation and line establishment.

The transformation protocol used to create all of the P-element transformants used in these studies has been described (24, 36). Transgene copy number was determined by Southern analysis for each transformed line (24), and those with multiple P-element integrations were discarded. The apoB 3′ MAR was excised from integrated mini-white transgenes in situ by using yeast flp recombinase. MAR/FRT males were crossed to .−1118; Cyo, 70FLP3A females and maintained at 25°C. The mated pairs were transferred to new vials every 24 h. At 2 h after removal of the adults, the embryos were incubated at 38°C for 1 h to induce expression of the flp recombinase that was under the control of the hsp70 promoter. After heat shock, the embryos were allowed to develop into adults at 25°C, and six males from each line were crossed with the appropriate balancer stock to generate balanced lines. Excision of the apoB 3′ MAR was verified by Southern analysis. Briefly, DNA was isolated from 35 flies of each heat-shocked line and parental pre-heat shock line and then cut with SpeI, a restriction endonuclease that cuts once within the mini-white cassette of the P-element transgene. The Southern blot was hybridized to an EcoRI/BamHI fragment containing the scs′ sequence. The size of the hybridizing DNA fragments was compared for pre- and post-heat-shocked lines.

Isolation of nuclei from embryos.

Nuclei were isolated from +MARFRT transformant D by using the protocol of Jack and Eggert (12) with modifications, as follows. Zero- to eighteen-hour-old embryos were collected from adult flies maintained in a large population cage and washed with water, and a 5-ml settled volume of embryos was dechorinated by suspending them in cold 11% sodium hypochlorite for 2 min. The dechorinated embryos were collected on a Nitex filter and washed with cold water before they were suspended in 200 ml of ice-cold N buffer (5 mM Tris [pH 7.4], 20 mM KCl, 0.125 mM spermidine, 0.05 mM spermine, 0.5 mM EDTA) plus 0.1% digitonin (Fluka 37006), 1× aprotinin (Sigma A-6279 is 100×), and 1× thiodiglycol (Sigma T-6125 is 100×). The embryonic membranes were disrupted by two strokes of a B (loose) pestle in a Wheaton glass homogenizer, filtered through Nitex, and centrifuged at 2,000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C. The pelleted nuclei were washed three times in 50 ml of cold N buffer plus 0.1% digitonin, and the optical density (OD) of the nuclei was measured at 260 and 280 nm. The nuclei were resuspended at 20 to 40 OD/ml in freezing buffer (1× N buffer, 50% glycerol, 1× aprotinin, 1× thiodiglycol, and 0.1% digitonin) and stored at −20°C.

MAR binding assay.

The in vivo MAR binding protocol used to assay binding of the human apoB 3′ MAR in the +MARFRT D line was first described by Mirkovitch et al. (22). Ten .260 units of +MARFRT D nuclei were washed twice and resuspended in 150 μl of wash buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 40 mM KCl, 0.25 mM spermidine, 0.1 mM spermine, 1 mM EDTA-KOH [pH 7.4], 20 μg of aprotinin [Sigma]/ml, 1% thiodiglycol) before stabilization for 18 min at 37°C. Nuclear “halos” were formed by extracting chromatin proteins with 3.5 ml of LIS buffer (5 mM HEPES [pH 7.4], 0.25 mM spermidine, 2 mM EDTA-KOH [pH 7.4], 2 mM KCl, 0.1% digitonin) and 86.5 mg of LIS (3,5-diiodosalicylic acid, lithium salt; Sigma) per sample and pelleted by centrifugation at 1,000 rpm for 4 min. The pellets were washed five times in digestion buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 20 mM KCl, 70 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 0.125 mM spermidine, 0.05 mM spermine, 20 μM aprotinin, 0.1% digitonin) to remove the LIS and then resuspended in 2 ml of digestion buffer. Halo DNA was cleaved from the pellet by overnight digestion at 37°C with 250 U each of PstI, BamHI, BglII, XhoI, HindIII, and NotI. Matrix-bound and released DNAs were separated by centrifugation and purified by overnight digestion with proteinase K, phenol-chloroform extraction, and ethanol precipitation before quantitation. The supernatant fraction contained ∼95% of the DNA, whereas only ∼5% remained in the matrix fraction, demonstrating that LIS extraction of chromatin proteins from embryonic fly nuclei was efficient. Then, 5 μg of DNA from the pellet and supernatant fractions in addition to 5 μg of total genomic DNA isolated from embryonic nuclei was analyzed by Southern hybridization. The probe used to detect the apoB 3′ MAR was a 786-bp Xho apoB 3′ MAR restriction fragment (18).

P-Element mobilization.

The +MARFRT P-element vectors containing the mini-white cassette were mobilized from their original positions on chromosome 3 to either chromosome 2, chromosome X, or another chromosome 3 for two transformed fly lines (D and F) and for their isogenic counterparts (−MARFRT D and F) from which the apoB 3′ MAR had been removed by flp recombinase. +MARFRT lines D and F were chosen for this analysis because they had intact 5′ and 3′ P-element ends as determined by sequencing the relevant inverse PCR products generated from genomic DNA of each transformant. None of the MARFRT transformants with transgene insertions in chromosome 2 had intact P-element ends, so they could not be used in these experiments. Females homozygous for the P-element insertion were crossed to males from the P-element transposase line .−1118; Sp/CyO; Δ2-3 Dr/TM6B Tb. All G1 male progeny with colored eyes (p[.]) and the Drop phenotype (Δ2-3 Dr) were crossed to TM3/D females in order to segregate the original p[.] chromosome. G2 males with colored eyes and TM3 or D had experienced a transposition of the P-element onto another chromosome. These males with the new P-element insertions on chromosome 2, X, or 3 were balanced by crossing the G2 males with colored eyes and +/TM3 or +/D to FM6/y; CyO/Pin females. DNA from the balanced mobilized lines was analyzed by Southern hybridization with an scs′ probe to verify that each line contained only one copy of the P-element after mobilization with Δ2-3 transposase.

Identification of P-element insertion sites.

The insertion sites of MARFRT transgenes were determined by using inverse PCR (described in detail at http://www.fruitfly.org/p_disrupt/inverse_pcr.html) to isolate genomic DNA sequences adjacent to each P-element insertion site. Briefly, DNA was isolated from 35 adult flies, digested with either Sau3AI or HinPI, and self-ligated overnight to form circular DNA molecules containing one P-element end plus adjacent Drosophila DNA sequences. PCR primers complementary to the 5′ (Plac4, ACTGTGCGTTAGGTCCTGTTCATTGTT; Plac1, CACCCAAGGCTCTGCTCCCACAAT) or 3′ (Pry2, CTTGCCGACGGGACCACCTTATTTATT; Pry1, CCTTAGCATGTCCGTGGGGTTTGAAT) ends of the PlacW′ P-element were used to amplify genomic DNA sequences adjacent to each P-element insertion. The PCR products were sequenced directly using either the Sp1 primer ACACAACCTTTCCTCTCAACAA (5′ P-element) or the Pry2 primer (see above) (3′ P-element) and the Applied Biosystems BigDye PCR sequencing system. The genomic position of each P-element insertion was determined by using BLASTN (http://www.NCBI.nih.gov) to identify Drosophila genomic DNA sequences adjacent to each P-element insertion site. Flybase (http://flybase.bio.indiana.edu/) was used to determine the cytogenetic location of transgenic P-elements and identify the closest gene.

RESULTS

Insulation of mini-white transgenes by the human ApoB 3′ MAR is copy number dependent but orientation independent.

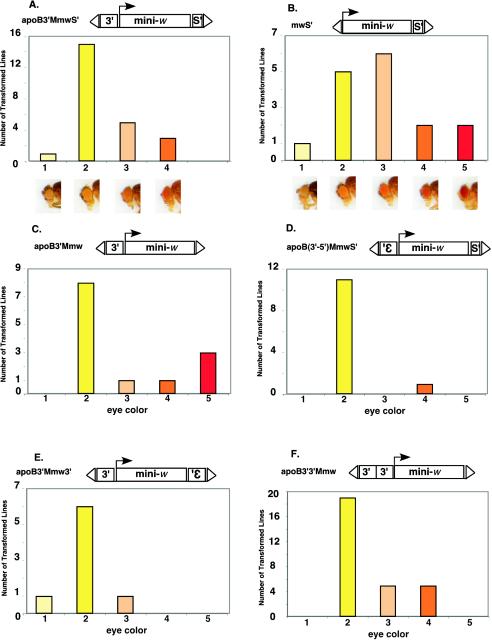

Using the mini-white position effect assay of Kellum and Schedl (16), we demonstrated previously that the ∼850-bp MAR from the 3′ end of the human apolipoprotein gene (apoB 3′ MAR), together with the Drosophila insulator scs′, could insulate transgene expression from chromosomal position effects in vivo (24). For example, most transformants that contained transgenes in which mini-white was flanked by the apoB 3′ MAR and scs′ had yellow eyes, the eye color phenotype expected for position-independent expression of mini-white from the enhancer-less white promoter used in these constructs (16) (apoB3′MmwS′; Fig. 1A). In contrast, Drosophila transformants containing transgenes with scs′ downstream of mini-white but no insulator sequences upstream displayed a wide range of eye color phenotypes that ranged from light yellow to dark red (mwS′; Fig. 1B). This indicates that the mini-white transgenes of these transformants were expressed in a position-dependent manner. Significantly, the red eye color, which results from interactions between mini-white and chromosomal enhancer sequences, was never observed for transformants containing both the apoB 3′ MAR and scs′; thus, red-eyed flies are diagnostic for transgenes whose expression is position dependent. Transgenic lines with the apoB 3′ MAR upstream of mini-white, but no insulator downstream, also showed position-dependent transgene expression, with nearly 25% of the lines exhibiting red eyes (apoB3′Mmw; Fig. 1C). These results confirm the observations of Kellum and Schedl, who demonstrated that single insulator elements cannot insulate transgene expression from chromosomal position effects in vivo (16).

FIG.1.

Factors affecting insulation of mini-white transgenes by the human apoB 3′ MAR. Transgenic Drosophila lines containing the transgenes shown above each panel were generated by P-element transformation as described in Materials and Methods. Each transformed line was assigned to one of five eye color phenotypes—1, light yellow; 2, yellow; 3, light orange; 4, orange; or 5, red—based on the eye colors of 4-day-old females homozygous for the P-element. Examples of each eye color phenotype are shown in the photographs below panels A and B. The colored bars represent the number of independent transformed lines exhibiting that particular eye color phenotype. Key: 3′, apoB 3′ MAR; mini-., mini-white expression cassette; s′, scs′; 3′ (inverted), apoB 3′ MAR in the reverse orientation; Δ, 5′ and 3′ P-element ends. (A) Mini-white flanked by the apoB 3′ MAR at the 5′ end and scs' at the 3′ end; (B) mini-white containing only scs′ at the 3′end; (C) mini-white containing only the apoB 3′ MAR at the 5′ end; (D) mini-white flanked by the apoB 3′ MAR in the reverse orientation at the 5′ end and scs′ at the 3′ end; (E) mini-white flanked by the apoB 3′ MAR both 5′ and 3′. The MAR downstream of mini-white is in the inverted 3′-to-5′ orientation. (F) Mini-white containing two copies of the apoB 3′ MAR upstream of the transcription unit.

To determine whether MAR orientation affected insulating activity, the apoB 3′ MAR was placed in the 3′-to-5′ orientation upstream of mini-white, with scs′ downstream [apoB(3′-5′)MmwS′; Fig. 1D]. More than 90% of these transformants had yellow eyes. Thus, the insulating activity of the apoB 3′ MAR was largely orientation independent.

All of the MAR-containing transgenes that displayed position-independent expression in this and a previous study (24) contained the Drosophila insulator element scs′ downstream of mini-white. To determine whether human MARs alone could confer chromosomal insulation, we prepared a transformation vector in which mini-white was flanked by the apoB 3′ MAR both upstream and downstream (apoB3′Mmw3′; Fig. 1E). Most (75%) of the Drosophila transformants expressing this transgene displayed yellow eyes, i.e., the transgene was expressed in a position-independent manner (Fig. 1E).

Finally, to determine whether chromosomal insulation required that the apoB 3′ MARs be positioned on either side of mini-white, we prepared a transformation vector in which two copies of the apoB 3′ MAR were located upstream of mini-white, but no insulator elements were downstream (apoB3′3′Mmw; Fig. 1F). Most (19 of 29) of the Drosophila transformants expressing this transgene had yellow eyes (Fig. 1F), and none had red eyes. Thus, whereas two copies of the apoB 3′ MAR were required for insulation of mini-white from chromosomal position effects, the positions of the MARs within the transgene were unimportant. This is in contrast to the common assertion that insulator elements must flank the expression cassette in order for chromosomal insulation to be observed (5, 16, 34).

Excision of the apoB 3′ MAR from integrated mini-white transgenes does not alter gene expression.

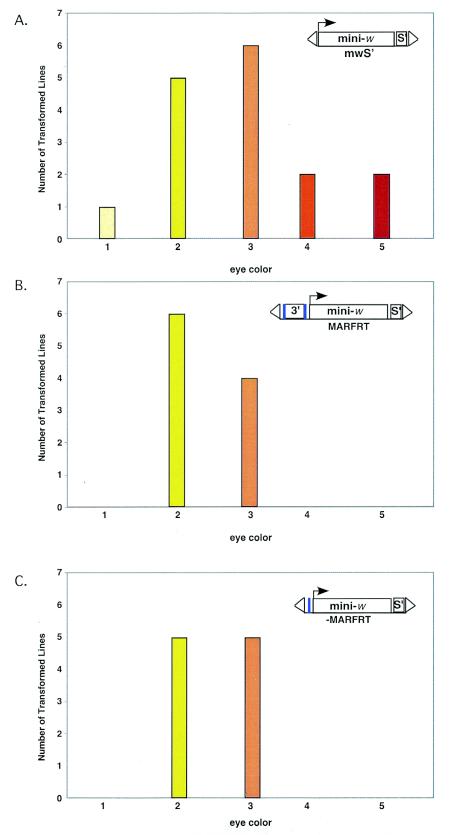

The experiments described above and previously (24) compared the eye color phenotypes of collections of Drosophila transformants expressing mini-white transgenes with or without putative insulator elements, such as the apoB 3′ MAR. These comparisons suffer from the caveat that in every instance the mini-white transgenes have integrated into different chromosomal sites. In order to compare the expression levels of mini-white transgenes with or without the apoB 3′ MAR at the same chromosomal site, we prepared a transformation vector in which the apoB 3′ MAR was flanked by FRT sites, allowing its removal postintegration by using the yeast flp recombinase. This vector, MARFRT, was comparable to apoB3′MmwS′ (Fig. 1A) except for the inclusion of 34-bp FRT sites on each side of the apoB 3′ MAR. Six of ten Drosophila transformants expressing MARFRT displayed yellow eyes, whereas the remaining four lines had light orange eyes (Fig. 2B). This tight distribution of eye color phenotypes among MARFRT transformants resembled that of other collections of chromosomally insulated lines (e.g., Fig. 1A), i.e., expression of MARFRT was position independent.

FIG. 2.

Excision of the apoB 3′ MAR after integration does not alter mini-white transgene expression. The transgenes in each collection of transformants are illustrated within each panel of the figure, where mini-. is the mini-white expression cassette, s′ is scs′, 3′ is apoB 3′ MAR, the blue boxes are the flp recombinase sites, and triangles indicate the 5′ and 3′ P-element ends. (A) The mwS′ lines used as controls in thisfigure are the same as those shown in Fig. 1A. The colored bars represent the number of independent transformed lines exhibiting that particular eye color phenotype, as follows: 1, light yellow; 2, yellow; 3, light orange; 4, orange; or 5, red. (B) The MARFRT transformants containing the mini-white transgene flanked by the apoB 3′ MAR at the 5′ end and scs′ at the 3′ end. Transgenic Drosophila lines containing the MARFRT transgene were prepared by P-element transformation as described in Materials and Methods. (C) −MARFRT lines were generated from the original +MARFRT transformants shown in panel B by precise excision of the apoB 3′ MAR by using flp recombinase as described in Materials and Methods.

Each of the MARFRT transformants was crossed with a Drosophila stock in which flp recombinase was under the control of an inducible heat shock promoter. The resulting embryos were incubated at 38°C for 1 h, and derivative lines were established. Three to five −MAR sublines were generated for 9 of the 10 primary +MAR transformants. Site-specific excision of the apoB 3′ MAR from the transgene was determined for each subline by Southern hybridization (data not shown), and the eye color phenotypes of the derivative lines that lacked the apoB 3′ MAR were assessed. Surprisingly, the distributions of eye color phenotypes among the −MAR derivatives were essentially identical to those of their +MAR parents. For example, 9 of the 10 −MAR lines shown in Fig. 2C had the same eye color phenotypes as their +MAR parents (Fig. 2B), and −MAR sublines of only a single +MAR line displayed a subtle yellow-to-light orange shift in eye color upon MAR excision. Thus, removing MAR sequences from previously integrated transgenes had no effect on gene expression.

This result was both unexpected and paradoxical. The −MAR derivatives generated in this experiment (−MARFRT, Fig. 2C) contain transgenes that are virtually identical to those of the mwS′ transformants (Fig. 2A), only a single 34-bp FRT site distinguishes the transgenes of the two families of transformants. However, the mwS′ transformants displayed a wide range of eye color phenotypes (Fig. 2A), including dark red, whereas the −MARFRT lines had only yellow or light orange eyes. These eye color phenotypes were stable. These observations indicate that, although the transgenes of mwS′ and −MARFRT lines were essentially identical, expression was position dependent in the mwS′ lines but position independent in the −MARFRT lines. A formal conclusion from these studies is that MAR sequences were required for the establishment of chromosomal insulation but not for its maintenance. To gain insight into potential mechanisms by which this effect might occur, P-element mobilization experiments were performed.

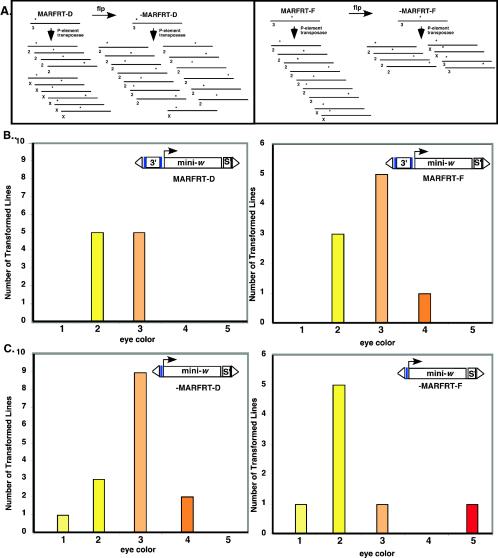

Insulation of mobilized mini-white transgenes is MAR dependent.

As described above, the mini-white transgenes of the MARFRT transformants and their −MARFRT derivatives were all expressed in a position-independent manner. This suggested that position-independent transgene expression among −MARFRT lines might be mediated through local effects at the sites of transgene integration. To test this possibility, we mobilized MARFRT and −MARFRT transgenes from two different chromosomal sites and assessed gene expression after reintegration into new genomic locations.

The MARFRT transgenes of transformant lines MARFRT-D and MARFRT-F were integrated at two different sites on the third chromosome. We mobilized these P-elements by crossing MARFRT-D, MARFRT-F, and their −MAR derivatives with a Drosophila stock expressing the P-element transposase. Sublines with transgene insertions on different chromosomes were then isolated as described in Materials and Methods. Ten new lines were generated from +MARFRT-D, 15 were generated from −MARFRT-D, 9 were generated from +MARFRT-F, and 8 were generated from −MARFRT-F (Fig. 3A). The eye color phenotypes of these lines with new transgene insertion sites are summarized in Fig. 3B and C. Most transformants produced by mobilizing the MAR-containing transgenes of MARFRT-D (Fig. 3B, left) and MARFRT-F (Fig. 3B, right) had yellow or light orange eyes, indicating that transgene expression was position independent, as expected. However, derivative lines prepared from the −MARFRT-D (Fig. 3C, left) and −MARFRT-F (Fig. 3C, right) transformants displayed a range of eye color phenotypes, including light yellow, orange, and red. Thus, these mobilized transgenes were expressed in a position-dependent manner.

FIG. 3.

Mini-white transgenes flanked by the apoB 3′ MAR and scs′ maintain insulation when mobilized to new locations in the Drosophila genome; transgenes without the apoB 3′MAR do not. P-element transgenes in the MAR-containing transformants MARFRT-D and MARFRT-F and their −MAR derivatives, −MARFRT-D and −MARFRT-F, respectively, were mobilized by expression of P-element transposase to create lines with novel transgene insertions sites, as illustrated schematically in panel A. Each line represents a particular Drosophila chromosome, the asterisks denote novel insertion sites, and the number below each line indicates the chromosome into which the P-element inserted after mobilization. (B) Eye color phenotypes of collections of Drosophila transformants created by mobilizing the P-elements in MARFRT-D (left) and MARFRT-F (right). The mobilized MARFRT and −MARFRT transgenes are illustrated inside each panel, where the blue boxes indicate the flp recombinase recognition sequences, 3′ is the apoB 3′ MAR, mini-. is the mini-white expression cassette, s′ is scs′, and the “▵” symbols indicate the 5′ and 3′ P-element ends. The colored bars represent the number of lines with novel MARFRT-D (left) and MARFRT-F (right) insertions exhibiting that eye color phenotype as follows: 1, light yellow; 2, yellow; 3, light orange; 4, orange; and 5, red. (C) Eye color phenotypes of collections of Drosophila transformants created by mobilizing the P-elements in −MARFRT-D (left) and −MARFRT-F (right). Panel C is organized as described above for panel B.

These results demonstrate that the apoB 3′ MAR was required for chromosomal insulation when the transgenes were mobilized to new genomic locations, regardless of their insulation status at previous locations. Thus, position-independent expression of mini-white in −MARFRT-D and −MARFRT-F was not an intrinsic property of the mini-white transgenes themselves; rather, it was a consequence of local chromatin effects at the sites of transgene integration.

Matrix association of MAR-containing transgenes in vivo.

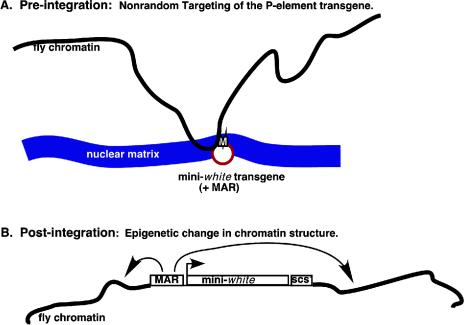

The experiments described above demonstrate that the apoB 3′ MAR is necessary for the establishment of chromosomal insulation but not for its maintenance. Two models that might explain these findings are shown in Fig. 4. In the first model, the apoB 3′ MAR directs nonrandom integration of the P-element to specific sites in the Drosophila genome. For example, the apoB 3′ MAR might target transgene integration to Drosophila chromatin that is associated with the nuclear matrix. A second model would be one in which MAR-containing transgenes induce stable epigenetic changes in local chromatin conformation at the sites of integration. In this model, the MAR would not be required for chromosomal insulation after the initial MAR-induced chromatin-remodeling event. A distinguishing feature of these models is the degree to which MAR-containing transgenes are associated with the nuclear matrix in vivo. To approach this question, two different experiments were performed.

FIG. 4.

Models for mechanisms of transgene insulation by the human apoB 3′ MAR. (A) Nonrandom targeting of the .-element transgene. The P-element containing either two copies of the apoB 3′ MAR or the apoB 3′ MAR and scs′ flanking the mini-white cassette associate with the nuclear matrix before integration of the P-element into the Drosophila genome. (B) Epigenetic chromatin alteration. The apoB 3′ MAR and scs′ cause an epigenetic change in local chromatin structure that results in insulation of the transgene that can be transmitted from one generation to the next.

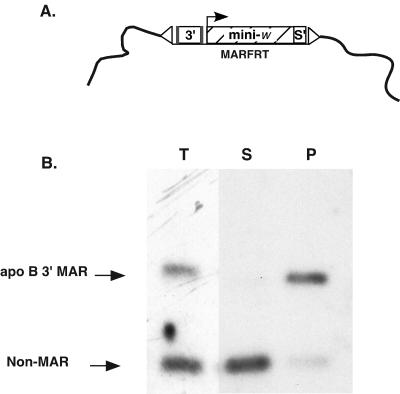

First, we used the in vivo MAR assay (22) to determine whether the human apoB 3′ MAR was actually associated with the Drosophila nuclear matrix after integration of the mini-white transgenes into the genome. Nuclei were isolated from 0- to 18-h-old FRTMAR-D embryos, and chromatin proteins were extracted by using the LIS protocol. The loops of DNA released by salt extraction were cleaved from the nuclear matrices by using restriction endonucleases, and DNA was separated into supernatant (released) and pellet (matrix-associated) fractions. Southern blot hybridization of the supernatant and pellet fractions with an apoB 3′ MAR probe demonstrated that >95% of the apoB 3′ MAR sequences were associated with the nuclear matrix (Fig. 5). Thus, the apoB 3′ MAR is associated with the Drosophila nuclear matrix in vivo.

FIG. 5.

The human apoB 3′ MAR binds to the Drosophila nuclear matrix in vivo. (A) Schematic of a P-element inserted into the genome of the transgenic Drosophila line MARFRT-D; the blue boxes indicate flp recombinase recognition sequences, 3′ is the apoB 3′ MAR, mini-. is the mini-white expression cassette, s′ indicates the scs′, and the “▵” symbols indicate the 5′ and 3′ P-element ends. (B) An in vivo MAR assay showing partitioning of the human apoB 3′ MAR with the Drosophila nuclear matrix. Nuclei were isolated from 0 to 18 h old Drosophila embryos, chromatin proteins were extracted with LIS, and the resulting nuclear halos of DNA were digested with PstI, BamHI, BglII, XhoI, HindIII, and NotI. Matrix-associated (P, pellet) and released (S, supernatant) DNA fragments were separated by centrifugation and purified, and 5 μg of DNA of each fraction was analyzed by Southern hybridization with the human apoB 3′ MAR fragment as a probe. Total (T) genomic DNA was purified from MARFRT-D embryos and used as a control.

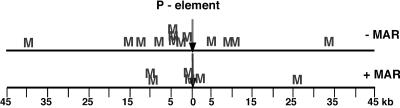

In a second experiment, we determined whether MAR-containing transgenes were preferentially integrating near or within Drosophila MARs compared to transgenes without MAR sequences. The chromosomal insertion sites for several MARFRT and mwS′ transformants were identified by sequencing the relevant inverse PCR products as described in Materials and Methods. The genomic location of each transgene insertion was determined by using BLAST to compare the sequence of the chromosomal DNA adjacent to the 5′ end of each P-element with the Drosophila genome sequence (http://www.ncbi.nih.gov/BLAST/). Table 1 shows the chromosomal locations, cytogenetic positions, and locations of transgene insertions relative to neighboring Drosophila genes. Interestingly, the majority of P-elements, both with or without MAR sequences, integrated within Drosophila genes. This observation is unusual because previous results had suggested that P-elements tend to integrate within several hundred base pairs of transcription start sites (19). Although we found several +MAR insertions in the vicinity of Drosophila MARs, some of the −MAR transgenes had inserted near Drosophila MARs as well. Thus, the tendency for MAR-containing transgenes to integrate near predicted MARs (http://www.futuresoft.org/MAR-Wiz/) appeared not to depend on MAR sequences within the transgenes (Fig. 6). Although this conclusion is subject to the caveat that some of the predicted matrix-binding elements may be false negatives or false positives (25), it suggests that MAR-containing transgenes do not preferentially integrate into MAR-rich regions in vivo. It remains possible, however, that MAR-containing transgenes may integrate into the genome nonrandomly, and targeted integration may be mediated by some other, as yet undefined, aspect of chromatin structure.

TABLE 1.

Insertion sites of .-element transformants

| Transformant | Chromosome | Cytogenetic location | Gene location |

|---|---|---|---|

| mwS′ | |||

| A | 3L | 75D5-75D6 | CG18811-exon 4 |

| B | 3L | 68C1-68C2 | Intergenic |

| C | 2R | 56F16 | LC21403-intron 6 |

| D | 2R | 54B16 | LD13441-intron |

| E | X | 1A1 | BACR37P7.5-exon2 |

| F | X | 6E4-6E5 | inx2-exon 1 |

| G | 2L | 39D3 | Histone H2B-like |

| H | 2L | 39A | GC12050-intron 1 |

| I | X | 4A1 | Intergenic |

| J | X | 19B3 | RAB, small monomeric GTPase-exon 3 |

| MARFRT | |||

| K | 3L | 63C2 | Intergenic |

| L | X | 13D4 | CG7872-exon |

| M | X | 3F2 | Intergenic |

| A | 2L | 32D3-32D4 | CG6181-exon 10 |

| B | 2L | 28A6 | Intergenic |

| C | 2L | 39E3 | CG2201, choline kinase-exon 8 |

| D | 3L | 63A5-63A6 | CG32486-exon |

| E | 3R | 90B4 | Intergenic |

| F | 3L | 67E5-67E6 | CG32066-exon 4 |

FIG. 6.

MAR-Wiz predictions of the locations of Drosophila MARs around P-element insertion sites. The arrows represent the different insertion sites of transgenes among all of the +MAR and −MAR transformants; each “M” represents the location of the nearest predicted MAR in the Drosophila genome. Predicted MAR sequences were identified in the vicinity of P-element insertion sites in both +MAR and −MAR transformants.

DISCUSSION

Well-studied chromosomal insulators in Drosophila include the specialized chromatin structures (scs and scs′) that flank the hsp70 heat shock locus, and the Su(Hw) binding sites within the gypsy retrotransposon. The proteins that bind to these insulators, and presumably mediate their activities, have been identified for all three DNA elements (7, 20, 32, 43). These insulators have the ability to protect transgenes from chromosomal position effects in vivo (16, 34); furthermore, they act as enhancer blockers when positioned between enhancers and promoters (15, 34). It has been suggested that a mechanism by which these insulators affect transcription is by regulating higher-order chromatin structure (for a review, see reference 8). One way they may accomplish this is by interacting with each other through their associated proteins, creating loops of intervening DNA that are protected from cis regulation by DNA elements located outside the loops. Evidence supporting this model has recently been reported for the Su(Hw) element within the gypsy insulator (3, 17). Byrd and Corces (3) demonstrated that the two endogenous Su(Hw) binding sites flanking the cut locus were associated with the nuclear matrix through their interactions with the Su(Hw) and Mod(mdg4) proteins, creating loops of chromatin in between. These authors also demonstrated that an intact nuclear matrix was required for loop formation.

We demonstrated previously that the human apoB 3′ MAR can insulate mini-white transgenes from chromosomal position effects when integrated into the genome of D. melanogaster (24). We show here that, although two copies of the apoB 3′ MAR were required for chromosomal insulation, flanking the mini-white transgenes was not necessary, since transgenes with two copies of the apoB 3′ MAR upstream of mini-white were insulated as well as transgenes that were flanked by apoB 3′ MARs. This suggests that chromatin looping may not be the means by which MARs encode insulating activity. In studies of other elements, two copies were generally required for insulation, but the arrangements of the elements within the transposon were not addressed (16, 34). Interestingly, when two Su(Hw) binding sites were placed between a promoter and an enhancer, the enhancer blocking activity of Su(Hw) was lost (4, 23).

A second observation that bears on the mechanism of MAR insulation derives from experiments in which MAR sequences were excised from insulated transgenes that had already integrated into the Drosophila genome. Excision of MAR sequences from these transgenes had no effects on gene expression. Thus, the presence of the apoB 3′ MAR was required for establishment of chromosomal insulation initially in the transformed Drosophila lines, but it was not necessary for the maintenance of the insulated phenotype after integration. This observation is not consistent with the looping model in its simplest form, which requires flanking elements for both the establishment and maintenance of insulation.

These observations suggest that the insulating activities of human MARs in Drosophila may be mediated by novel mechanisms. Two possibilities can be envisioned. In one model, MAR sequences may cause P-element transgenes to home to the nuclear matrix prior to integration. This might target transgene integration to specific kinds of sites within the Drosophila genome. According to this view, insulation of transgene expression would be a secondary effect due to chromosomal targeting. A second model would postulate that the chromatin structure of the integration site is altered epigenetically in a MAR-dependent manner. Once established, this epigenetic alteration could be stably propagated through subsequent generations. These models are distinct from those proposed for scs/scs′, gypsy, and CTCF, but a common feature of all of these models is that insulation is mediated by effects on chromatin structure.

To determine whether MAR-containing transgenes might be preferentially associating with the Drosophila nuclear matrix, two kinds of experiments were performed. First, we used in vivo MAR assays to show that human apoB 3′ MAR sequences associate with the Drosophila nuclear matrix in vivo. Second, we determined the locations of +MAR and −MAR insertion sites relative to MAR sequences in the Drosophila genome. No preferential integration of MAR-containing transgenes near Drosophila MARs was observed, suggesting that chromosomal targeting to MAR sequences may not be involved. An important caveat to this conclusion, however, is that the matrix binding activities of the MARs identified in silico have not yet been critically assessed in vitro.

Many insulating elements encode both enhancer blocking and insulating activities. Recently, it was demonstrated that these two activities within HS4, an insulator in the chicken β-globin locus, are separable (31), and CTCF was identified as the trans-acting factor that mediates enhancer blocking (1). In contrast, whereas the apoB 3′ MAR does insulate against position effects, it does not block enhancer function (unpublished observations). Interestingly, the AT-rich human apoB 3′ MAR does not contain CTCF binding sites.

MARs are defined by their abilities to associate with the nuclear matrix. This structural definition does not provide insight into the functions of MARs in vivo, which remain controversial (12, 30). The specificity of MAR function must result from a diversity of proteins that bind to them. These proteins could be components of the nuclear matrix itself or components that interact with matrix proteins. These kinds of interactions are exemplified by the T-cell-specific MAR-binding protein, SATBI, and by the Su(Hw) protein, both of which bind to specific DNA sequences and cause them to become matrix associated. Because both proteins associate with the nuclear matrix, the DNA sequences they interact with may be defined as MARs, but the functional consequences of those interactions might be quite different. According to this view, it is not surprising that some MARs seem to have insulating activities (21, 24), but others do not (29, 38). These differences in function must result from the interactions of specific proteins with matrix-binding DNA sequences. The identification of these proteins will be an important step in determining the mechanisms of MAR function.

Acknowledgments

We thank Susan Parkhurst, Meng-Chao Yao, Julio Vazquez, Wendy Gombert, and Anton Krumm for critically reading the manuscript and Lourdes Sarausad for technical assistance.

These studies were supported by grant GM26449 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bell, A. C., A. G. West, and G. Felsenfeld. 1999. The protein CTCF is required for the enhancer blocking activity of vertebrate insulators. Cell 98:387-396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boulikas, T. 1993. Nature of DNA sequences at the attachment regions of genes to the nuclear matrix. J. Cell. Biochem. 52:14-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Byrd, K., and V. G. Corces. 2003. Visualization of chromatin domains created by the gypsy insulator of Drosophila. J. Cell Biol. 162:565-574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cai, H. N., and P. Shen. 2001. Effects of cis arrangement of chromatin insulators on enhancer-blocking activity. Science 291:493-495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chung, J. H., M. Whiteley, and G. Felsenfeld. 1993. A 5′ element of the chicken b-globin domain serves as an insulator in human erythroid cells and protects against position effect in Drosophila. Cell 74:505-514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dickinson, L. A., T. Joh, Y. Kohwi, and T. Kohwi-Shigematsu. 1992. A tissue-specific MAR/SAR DNA-binding protein with unusual binding site recognition. Cell 70:631-645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gaszner, M., J. Vazquez, and P. Schedl. 1999. The Zw5 protein, a component of the scs chromatin domain boundary, is able to block enhancer-promoter interaction. Genes Dev. 13:2098-2107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gerasimova, T. I., and V. G. Corces. 2001. Chromatin insulators and boundaries: effects on transcription and nuclear organization. Annu. Rev. Genet. 35:193-208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Glazko, G. V., I. B. Rogozin, and M. V. Glazkov. 2001. Comparative study and prediction of DNA fragments associated with various elements of the nuclear matrix. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1517:351-364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Howard, M. T., M. P. Lee, T. S. Hsieh, and J. D. Griffith. 1991. Drosophila topoisomerase II-DNA interactions are affected by DNA structure. J. Mol. Biol. 217:53-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Izaurralde, E., J. Mirkovitch, and U. K. Laemmli. 1988. Interaction of DNA with nuclear scaffolds in vitro. J. Mol. Biol. 200:111-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jack, R. S., and H. Eggert. 1992. The elusive nuclear matrix. Eur. J. Biochem. 209:503-509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kalos, M., and R. E. K. Fournier. 1995. Position-independent transgene expression mediated by boundary elements from the apolipoprotein B chromatin domain. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15:198-207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kas, E., and U. K. Laemmli. 1992. In vivo topoisomerase II cleavage of the Drosophila histone and satellite III repeats: DNA sequence and structural characteristics. EMBO J. 11:705-716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kellum, R., and P. Schedl. 1992. A group of scs elements function as domain boundaries in an enhancer-blocking assay. Mol. Cell. Biol. 12:2424-2431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kellum, R., and P. Schedl. 1991. A position-effect assay for boundaries of higher-order chromosomal domains. Cell 64:941-950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuhn, E. J., M. M. Viering, K. M. Rhodes, and P. K. Geyer. 2003. A test of insulator interactions in Drosophila. EMBO J. 22:2463-2471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Levy-Wilson, B., and C. Fortier. 1989. The limits of the DNase I-sensitive domain of the human apolipoprotein B gene coincide with the locations of chromosomal anchorage loops and define the 5′ and 3′ boundaries of the gene. J. Biol. Chem. 264:1196-1204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liao, G. C., E. J. Rehm, and G. M. Rubin. 2000. Insertion site preferences of the P transposable element in Drosophila melanogaster. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:3347-3351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mazo, A. M., L. J. Mizrokhi, A. A. Karavanov, Y. A. Sedkov, A. A. Krichevskaja, and Y. V. Ilyin. 1989. Suppression in Drosophila: Su(Hw) and su(f) gene products interact with a region of gypsy (mdg4) regulating its transcriptional activity. EMBO J. 8:903-911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McKnight, R. A., A. Shamay, L. Sankaran, R. J. Wall, and L. Hennighausen. 1992. Matrix-attachment regions can impart position-independent regulation of a tissue-specific gene in transgenic mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89:6943-6947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mirkovitch, J., M. E. Mirault, and U. K. Laemmli. 1984. Organization of the higher-order chromatin loop: specific DNA attachment sites on nuclear scaffold. Cell 39:223-232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Muravyova, E., A. Golovnin, E. Gracheva, A. Parshikov, T. Belenkaya, V. Pirrotta, and P. Georgiev. 2001. Loss of insulator activity by paired Su(Hw) chromatin insulators. Science 291:495-498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Namciu, S. J., K. B. Blochlinger, and R. E. K. Fournier. 1998. Human matrix attachment regions insulate transgene expression from chromosomal position effects in Drosophila melanogaster. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18:2382-2391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Namciu, S. J., R. D. Friedman, M. D. Marsden, L. M. Sarausad, C. L. Jasoni, and R. E. K. Fournier. 2004. Sequence organization and matrix attachment regions of the human serine protease inhibitor gene cluster at 14q32.1. Mammalian Genome 15:162-178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ostermeier, G. C., Z. Liu, R. P. Martins, R. R. Bharadwaj, J. Ellis, S. Draghici, and S. A. Krawetz. 2003. Nuclear matrix association of the human beta-globin locus utilizing a novel approach to quantitative real-time PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 31:3257-3266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Paulson, J. R., and U. K. Laemmli. 1977. The structure of histone-depleted metaphase chromosomes. Cell 12:817-828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Phi-Van, L., J. P. von Kries, W. Ostertag, and W. H. Stratling. 1990. The chicken lysozyme 5′ matrix attachment region increases transcription from a heterologous promoter in heterologous cells and dampens position effects on the expression of transfected genes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 10:2302-2307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Poljak, L., C. Seum, T. Mattioni, and U. K. Laemmli. 1994. SARs stimulate but do not confer position independent gene expression. Nucleic Acids Res. 22:4386-4394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Razin, S. V. 1996. Functional architecture of chromosomal DNA domains. Crit. Rev. Eukaryot. Gene Expr. 6:247-269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Recillas-Targa, F., M. J. Pikaart, B. Burgess-Beusse, A. C. Bell, M. D. Litt, A. G. West, M. Gaszner, and G. Felsenfeld. 2002. Position-effect protection and enhancer blocking by the chicken beta-globin insulator are separable activities. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:6883-6888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rivella, S., J. A. Callegari, C. May, C. W. Tan, and M. Sadelain. 2000. The cHS4 insulator increases the probability of retroviral expression at random chromosomal integration sites. J. Virol. 74:4679-4687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rollini, P., S. J. Namciu, M. D. Marsden, and R. E. K. Fournier. 1999. Identification and characterization of nuclear matrix-attachment regions in the human serpin gene cluster at 14q32.1. Nucleic Acids Res. 27:3779-3791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roseman, R. R., V. Pirrotta, and P. K. Geyer. 1993. The Su(Hw) protein insulates expression of the Drosophila melanogaster white gene from chromosomal position-effects. EMBO J. 12:435-442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Singh, G. B., J. A. Kramer, and S. A. Krawetz. 1997. Mathematical model to predict regions of chromatin attachment to the nuclear matrix. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:1419-1425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Spradling, A. C., and G. M. Rubin. 1982. Transposition of cloned P elements into Drosophila germ line chromosomes. Science 218:341-347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Udvardy, A., and P. Schedl. 1991. Chromatin structure, not DNA sequence specificity, is the primary determinant of topoisomerase II sites of action in vivo. Mol. Cell. Biol. 11:4973-4984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.van der Geest, A. H., and T. C. Hall. 1997. The B-phaseolin 5′ matrix attachment region acts as an enhancer facilitator. Plant Mol. Biol. 33:553-557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vazquez, J., and P. Schedl. 1994. Sequences required for enhancer blocking activity of scs are located within two nuclease-hypersensitive regions. EMBO J. 13:5984-5993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Walters, M. C., W. Magis, S. Fiering, J. Eidemiller, D. Scalzo, M. Groudine, and D. I. Martin. 1996. Transcriptional enhancers act in cis to suppress position-effect variegation. Genes Dev. 10:185-195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wells, K. D., J. A. Foster, K. Moore, V. G. Pursel, and R. J. Wall. 1999. Codon optimization, genetic insulation, and an rtTA reporter improve performance of the tetracycline switch. Transgenic Res. 8:371-381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Whitelaw, C. B., S. Grolli, P. Accornero, G. Donofrio, E. Farini, and J. Webster. 2000. Matrix attachment region regulates basal beta-lactoglobulin transgene expression. Gene 244:73-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhao, K., C. M. Hart, and U. K. Laemmli. 1995. Visualization of chromosomal domains with boundary element-associated factor BEAF-32. Cell 81:879-889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]