Abstract

In all trypanosomatids, trans splicing of the spliced leader (SL) RNA is a required step in the maturation of all nucleus-derived mRNAs. The SL RNA is transcribed with an oligo-U 3′ extension that is removed prior to trans splicing. Here we report the identification and characterization of a nonexosomal, 3′→5′ exonuclease required for SL RNA 3′-end formation in Trypanosoma brucei. We named this enzyme SNIP (for snRNA incomplete 3′ processing). The central 158-amino-acid domain of SNIP is related to the exonuclease III (ExoIII) domain of the 3′→5′ proofreading ɛ subunit of Escherichia coli DNA polymerase III holoenzyme. SNIP had a preference for oligo(U) 3′ extensions in vitro. RNA interference-mediated knockdown of SNIP resulted in a growth defect and correlated with the accumulation of one- to two- nucleotide 3′ extensions of SL RNA, U2 and U4 snRNAs, a five-nucleotide extension of 5S rRNA, and the destabilization of U3 snoRNA and U2 snRNA. SNIP-green fluorescent protein localized to the nucleoplasm, and substrate SL RNA derived from SNIP knockdown cells showed wild-type cap 4 modification, indicating that SNIP acts on SL RNA after cytosolic trafficking. Since the primary SL RNA transcript was not the accumulating species in SNIP knockdown cells, SL RNA 3′-end formation is a multistep process in which SNIP provides the ultimate 3′-end polishing. We speculate that SNIP is part of an organized nucleoplasmic machinery responsible for processing of SL RNA.

The kinetoplastid protozoa are deep-branching eukaryotes that have evolved unusual mechanisms of nuclear gene expression. Transcription initiation of protein-coding genes in these organisms is regulated minimally, and all nucleus-derived pre-mRNAs are transcribed polycistronically. To resolve these polycistronic pre-mRNAs into mature mRNAs, kinetoplastids use the trans-splicing reaction. Through trans splicing, the 5′ 39-nucleotide (nt) spliced leader (SL) is transferred from the substrate SL RNA to the polycistronic pre-mRNA, yielding trans-spliced mRNAs. In addition to substrate SL RNA, trans splicing also requires the coordinated functions of mature U2, U4, U5, and U6 small nuclear RNAs (snRNAs) and associated proteins.

Although there are differences in the details of individual snRNA gene transcription among eukaryotes, all snRNAs share at least one common feature: nascent snRNAs contain 3′ extensions as a consequence of transcription termination. These 3′ extensions are of variable sequence and length and are removed to yield the mature 3′ end of each snRNA (10). In metazoans 3′-extension removal of nascent U1 snRNA was shown to require (i) intracellular trafficking of U1 snRNA, (ii) the activities of at least two nucleases, and (iii) a cis-acting element downstream of the mature 3′ end of U1 snRNA (5). The first nuclease acting on nascent U1 snRNA was cytosolic and left a 2-nt extension, whereas the final 3′-end trimming activity was nuclear (20). 3′-Extension removal of human precursor U2 snRNA also required intracellular trafficking, a 3′ cis-acting sequence element, and at least two distinct nuclease activities (7). The identities of the nucleases responsible for metazoan snRNA 3′-extension removal are not known.

In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, nascent U4 snRNA 3′-extension removal minimally requires the activities of three nucleases (15). The ≈500-nt 3′ extension of nascent U4 snRNA is cut initially by the endonuclease RNT1, trimmed secondarily by the exonuclease RRP6, and polished finally by the exonuclease REX2 (15). RRP6 is part of a complex of 3′→5′ exonucleases known as the exosome (16). REX2 is one of three partially characterized nonexosomal RNase D-type 3′→5′ exonucleases that are involved in the final 3′-end formation of a variety of small RNAs (15). Knockouts of REX1, REX2, and REX3 in S. cerevisiae individually or as a trio were viable, suggesting that 3′-extended snRNA precursors are competent to catalyze cis splicing (15).

In the kinetoplastid Leishmania tarentolae, accurate 3′-end formation of the SL RNA is necessary but not sufficient for the SL RNA to function in trans splicing. Mutagenesis studies revealed that there are two intronic cis elements required for accurate 3′-end formation of the substrate SL RNA (14). The first cis element of SL RNA is an Sm protein binding site, and the second is the intact structure of stem-loop III, located immediately downstream of the Sm protein binding site and immediately upstream of the mature 3′ end (14). In Trypanosoma brucei substrate SL RNA 3′-end processing requires intracellular trafficking (22) and Sm protein binding (9, 21).

Here we report the identification and characterization of T. brucei SNIP (for snRNA incomplete 3′ processing). SNIP is an essential 3′→5′ exonuclease required for the final 3′-end trimming step of SL RNA, U2 and U4 snRNAs, U3 small nucleolar RNA (snoRNA), and 5S rRNA. Based on the spectrum of substrates, SNIP is not an ortholog of any single S. cerevisiae REX protein.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cloning and plasmids.

A genomic fragment spanning the 2.3-kb SNIP (GeneDB accession no. 66.m00281) coding region from T. brucei was amplified by using oligonucleotides SNIP-F (5′-ATG GGA CGC CGA AAG TGT TC) and SNIP-R (5′-CTG TTG CTC GCA TGC CGG G) and cloned by using the TOPO-TA kit (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. SNIP was excised from this construction with EcoRI, and the 2.3-kb fragment was gel purified and ligated to itself. The SNIP multimer was then digested with XhoI and HindIII, and a 1.3-kb fragment containing the 5′- and 3′-terminal 650 nt of SNIP was gel purified. This fragment contained a 1-kb internal deletion, which removed the entire exonuclease III (ExoIII) homologous region. The XhoI/HindIII ExoIII deletion fragment was subcloned into pZJM (17), resulting in tetracycline (TET)-inducible, double-stranded RNA interference (RNAi) plasmid pZJM-SNIP. The SNIP portion of the subclone was confirmed by sequencing.

For overexpression and purification of recombinant SNIP, the 2.3-kb EcoRI-flanked SNIP open reading frame (ORF) was inserted into pET28A (Novagen) to generate pETSNIP, which when expressed in Escherichia coli, placed dual His6 tags at the amino and carboxy termini of recombinant SNIP-His6.

To generate the localization construction pHDsnipGFP, the 2.3-kb ORF of SNIP lacking a stop codon was PCR amplified with HindIII- and XbaI-flanked forward and reverse primers, respectively. This PCR fragment was ligated upstream of green fluorescent protein (GFP) in pHD496, which contains a hygromycin-selectable marker. The insert of the resulting plasmid, pHDsnipGFP, was sequenced in both directions.

Strains and cell culture.

Procyclic T. brucei strain 29-13 (19) containing a T7 RNA polymerase (Pol) and the TET repressor was grown at 27°C in semidefined maintenance (SM) medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum in the presence of hygromycin (50 μg/ml) and G418 (15 μg/ml). Log-phase cultures (ca. 5 × 107 cells/ml) were used for transfection as described previously (17).

RNAi was performed by using the pZJM system developed by Wang et al. (17). The pZJM-SNIP construction was transfected into T. brucei 29-13 cells by electroporation as performed previously (22), and drug-resistant T. brucei was cloned by limiting dilution in SM medium under the selection pressure of G418 (20 μg/ml; ICN), hygromycin (50 μg/ml; PGC Scientific), and Zeocin (20 μg/ml; Invitrogen). RNAi was induced by the addition of 100 ng of TET/ml to pZJM-SNIP cells at 105 cells/ml, and growth was assayed by using a Coulter Counter (Beckman/Coulter).

pHDsnipGFP was electroporated into KH4A YTAT T. brucei (obtained from Kent Hill, University of California at Los Angeles) as described above. Stable transfectants were selected with 50 μg of hygromycin/ml, and 24 clonal cell lines were made by limiting dilution.

In vitro activity assay.

Native SNIP-His6 was isolated by cobalt-column chromatography according to the manufacturer's instructions (Clontech). The in vitro exonuclease activity assay was performed as described previously (1). Briefly, the cobalt column eluate was dialyzed overnight in 150 mM KCl-5 mM MgCl2-50% glycerol-1 mM dithiothreitol and then stored at −20°C. Next, 0.1 μmol of γ-32P-5′-end-labeled RNA oligonucleotide was incubated with 30 nmol of SNIP-His6 at ambient temperature. The time course of incubation is indicated in Fig. 2. The reaction products were resolved by electrophoresis through a 15% acrylamide-8 M urea sequencing gel until the bromophenol blue dye had run off the bottom of the gel, dried, exposed to a PhosphorImager screen (Amersham), and quantitated with ImageQuant (Amersham) software. The RNA oligonucleotide sequences were as follows: G6, 5′-GCU AUA CAU GCU ACA UUG GGG GG; A6, 5′-GCU AUG UCU GCU AAC UUG AAA AAA; U6, 5′-GCU AUG UCU GCU AAC UUG UUU UUU; C6, 5′-GCU AUG UCU GCU AAC UUG CCC CCC; and U5dU, 5′-GCU AUG UCU GCU AAC UUG UUU UUdU (1).

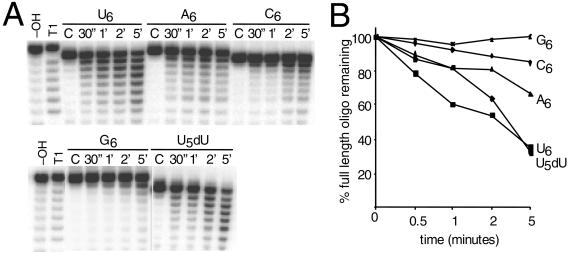

FIG. 2.

T. brucei SNIP has 3′→5′ exonuclease activity in vitro. (A) 5′-end-labeled RNA oligonucleotides differing only in the 6 nucleotides at their 3′ ends indicated 3′ as were incubated with 30 nmol of SNIP-His6 for 30 s (lane 30) or 1, 2, or 5 min (lanes 1′, 2′, and 5′, respectively) or mock treated with storage buffer alone (lane C). The reaction products were resolved by electrophoresis through a 15% acrylamide-8 M urea sequencing gel, dried, and exposed. Included for size comparison is the RNase T1-digested G6 substrate, which migrates through the gel slightly slower than the C6 and U-containing substrates. (B) Graphical representation of the percentage of remaining full-length oligonucleotides as a function of time.

RNA analysis.

Total RNA was isolated with the TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) as described previously (22). Medium- and high-resolution RNA blotting, RNA primer extension, and DNA sequencing reactions were performed as described previously (22). Low-resolution RNA blots were generated as described previously (13). Blots were hybridized with γ-32P-end-labeled oligonucleotides and exposed by using PhosphorImager (Amersham) cassettes as described previously (13).

Fluorescence microscopy.

For visualization of the SNIP-GFP fusion, live clonal populations of cells were washed in 1× phosphate-buffered saline containing 100 ng of DAPI (4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole; Sigma)/ml for 5 min at ambient temperature and then visualized with a Zeiss Axiocam fluorescence microscope fitted with a Zeiss ×63 objective lens and a fluorescein isothiocyanate-GFP fluorescent filter (Chroma). All images were captured with a Zeiss Axiocam digital camera and Zeiss Axiovision software. Images were processed with Adobe Photoshop.

Data deposition.

The sequences reported here have been deposited in the GenBank database (TbSNIP, GeneDB Tb08.10J17.670; LmSNIP, GeneDB LmjF10.0270; TcSNIP, GeneDB Tc00.1047053511575.40).

RESULTS

Cloning of T. brucei SNIP.

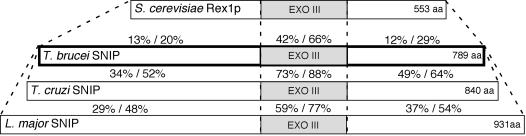

Our studies with L. tarentolae and T. brucei indicate that a key step in SL RNA maturation is 3′-end nucleolytic processing (14). We initiated our search for the nuclease(s) responsible for SL RNA 3′-extension removal by BLAST searching the kinetoplastid databases with the three S. cerevisiae REX nuclease family members, since these proteins are involved in the processing of small RNAs in S. cerevisiae (15). TBLASTN searches of the EMBL parasite genome server with S. cerevisiae REX1 yielded significant hits to a 158-amino-acid (aa) region within 789-, 840-, and 931-aa translated ORFs present in T. brucei, Trypanosoma cruzi, and Leishmania major, respectively (Fig. 1). Outside the 158-aa region there was no significant similarity between the S. cerevisiae REX1 and the kinetoplastid ORFs. The L. major and T. brucei proteins share 38% identity and 56% similarity overall; the T. brucei and T. cruzi proteins share 49% identity and 72% similarity overall. Intraspecies BLAST searches indicated that the identified ORF was not part of a larger gene family in the kinetoplastids. After genetic and biochemical analyses described below, we named the kinetoplastid proteins SNIP (for snRNA incomplete 3′ processing).

FIG. 1.

Identification of T. brucei SNIP. Shown are the relative sizes (in amino acids) of T. brucei SNIP, T. cruzi SNIP, L. major SNIP, and S. cerevisiae REX1p. The proteins are aligned relative to the gray-shaded ExoIII domain of each protein, which has similarity to the ɛ subunit of E. coli DNA Pol III. Shown are the amino acid identity and similarity comparisons between hatched domains of T. brucei, T. cruzi, and L. major SNIP (lower) and between T. brucei SNIP and S. cerevisiae REX1p (upper).

The central 158-aa domain of SNIP identified in our search showed similarity to the ExoIII domain of the ɛ subunit of E. coli DNA Pol III, which contains the editing 3′→5′ exonuclease activity of the DNA Pol III holoenzyme (11), as well as the REX RNA exonucleases. Thus, the sequence recognized by the search engine likely represents a domain common to diverse nucleases. We proceeded to characterize SNIP from T. brucei.

SNIP has 3′→5′ exonuclease activity in vitro.

In our examination of SNIP, we initially assayed for nucleolytic activity by using purified recombinant protein. We created a His-tagged version of SNIP for expression and purification from bacteria. Ribo-oligonucleotides were used as substrates for nuclease activity (1).

To demonstrate that we had indeed identified a 3′→5′ exonuclease, bacterially expressed, recombinant His-tagged SNIP (SNIP-His6) was purified by standard cobalt column chromatography under native conditions with the full-length, 2.3-kb T. brucei SNIP. We performed a 5-min time course with 30 ng of SNIP-His6 and the indicated 0.1-μm 5′-end-labeled RNA oligonucleotide substrates that differ only in the 6 nucleotides at their 3′ ends (Fig. 2A). Hydroxy radical and RNase T1 cleavage products of the G6 probe were run alongside as size standards (18). When the amounts of full-length oligonucleotide substrate remaining as a function of time were compared, SNIP-His6 showed a bias toward U6 ≫ A6 > C6 > G6 (Fig. 2B). SNIP-His6 did not differentiate between rU or dU at the 3′ terminus of the oligonucleotide substrate in vitro. Although it is possible that a bacterial exonuclease copurified with SNIP, control experiments with the unrelated S. cerevisiae TOM70-His6 purified under identical conditions as SNIP-His6 showed no appreciable degradation of the RNA oligonucleotide substrates (data not shown). Viewed in concert with the experiments detailed below, it is probable that the observed in vitro exonuclease activity was due to the presence of SNIP-His6 and not to a spurious bacterial contaminant.

The demonstration that SNIP had an in vitro substrate preference for U residues supported its potential for a nuclease to remove the 3′ end of nascent SL RNA transcripts that terminate in poly(U) tracts (13, 22). We next examined the in vivo role of SNIP in T. brucei.

SNIP is an essential gene in T. brucei.

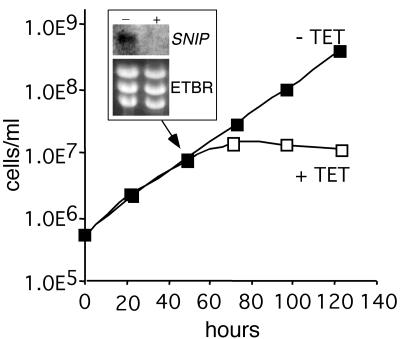

To test the function of SNIP in T. brucei, we used Tet-inducible RNAi, which allows specific knockdown of target mRNA levels with a subsequent loss of target protein (17). The RNAi construction contained a 1.3-kb fragment of the SNIP ORF with an internal deletion of the ExoIII-homologous domain. Induction of RNAi demonstrated a TET-dependent loss of SNIP mRNA at 48 h by RNA blotting and a subsequent growth defect at 72 h (Fig. 3). Microscopic examination of the induced SNIP RNAi cells at 72 h revealed extensive morphological defects and cell death associated with growth curve divergence (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

SNIP function is essential in T. brucei. Procyclic T. brucei strain 29-13 was transfected with pZJM-SNIP. Clonal stable transfectants were inoculated at 7.5 × 105 cells/ml in the absence (▪) or presence (□) of 100 ng of TET/ml, and cells were counted at the indicated time points. RNA was extracted at 48 h from both cultures, separated on an agarose-formaldehyde gel, transferred, and probed with a γ-32P-labeled SNIP probe (inset), which recognizes the 2.3-kb mRNA. The ethidium bromide (ETBR)-stained gel is provided as a loading control.

The SNIP knockdown data demonstrate that SNIP is required for T. brucei viability. Based on the in vitro and in vivo data, we hypothesized that SNIP may be involved in 3′-end processing of SL RNA and, by analogy to the REX family, possibly of other small RNAs. Thus, the appearance of 3′-end formation defects in small RNAs was examined in cells under knockdown for SNIP.

The absence of SNIP correlates with defects in 3′-extension removal for SL RNA and other small RNAs.

Loss of 3′ processing in small RNA molecules can be visualized by the accumulation of higher-molecular-weight precursors on RNA blots. For SL RNA we anticipated the accumulation of the T tract termination products as seen in the absence of an intact Sm-binding site or stem-loop III disruption (13).

We investigated the molecular phenotype of the SNIP knockdown cells at 48 h after RNAi induction with respect to a variety of snRNA, rRNA, and snoRNA substrates by high-resolution RNA blotting. In choosing this time point we hoped to score the primary, rather than secondary, effects of a SNIP knockdown. We chose 48 h for three reasons: (i) SNIP mRNA was undetectable at 48 h (Fig. 3 inset), (ii) the TET-induced cells looked normal morphologically at 48 h (data not shown), and (iii) 48 h was the last time point at which the growth curves of TET-induced and uninduced cell lines overlapped (Fig. 3).

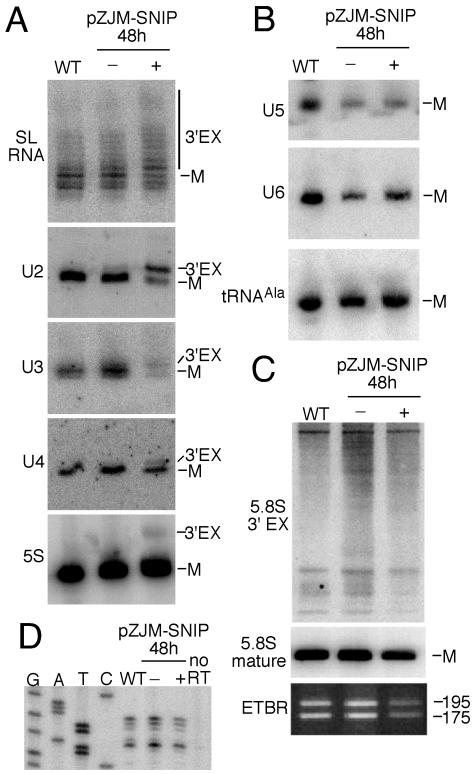

The loss of SNIP mRNA correlated with 3′-end-formation defects for substrate SL RNA, U2 and U4 snRNAs, U3 snoRNA, and 5S rRNA (Fig. 4A). The 3′ ends of SL RNA from mock-induced and TET-induced SNIP RNAi cells were mapped. The majority of 3′ ends for SL RNA from uninduced cells was C142 (6), whereas the majority of 3′ ends from TET-induced cells was U143 (data not shown). In the case of all but the 5S rRNA, which accumulated a 4- to 5-nt longer form, the substrate RNAs accumulated species 1 to 3 nt longer than their mature forms. SL RNA is the only SNIP substrate that is actively consumed in trans splicing; however, the U2 snRNA and U3 snoRNA showed an overall decrease in abundance possibly due to instability of improperly 3′-end-processed forms. In contrast, U5 and U6 snRNAs, as well as tRNAAla, were not affected by the SNIP knockdown (Fig. 4B), as was the 5.8S rRNA (Fig. 4C). SL RNA from TET-induced cells was further examined by primer extension to assess any modification in cap 4 formation. We have previously shown that SL RNA 3′-extension removal either precedes or is concurrent with 5′-end cap 4 methylation (12). There was no difference in the primer extension patterns between the SNIP induced and uninduced RNA populations (Fig. 4D). RNA derived from TET-induced cells was examined for accumulation of unspliced α/β-tubulin precursors by RNase protection (4). No precursors accumulated, indicating that trans splicing was not affected by SNIP depletion at this time point (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

Molecular phenotypes of RNAi-mediated SNIP knockdown. Total RNA was extracted from untransfected 29-13 cells (wild type [WT]) or transfectants of pZJM-SNIP grown for 48 h in the absence (−) or presence (+) of TET. (A) Substrates affected by knockdown of SNIP. RNA was resolved by electrophoresis through a sequencing gel, transferred to nylon membranes, and hybridized with the indicated γ-32P-labeled probes. The mature (M) and 3′-extension (3′EX) forms of each RNA are indicated. (B) Substrates unaffected by knockdown of SNIP. The blot used in panel A was probed for U5 and U6 snRNAs, and tRNAAla. (C) Exosome-processing intermediates are not generated by SNIP knockdown. The RNAs described above were resolved by electrophoresis through a medium-resolution acrylamide gel, blotted to nylon membrane, and probed with a γ-32P-labeled 3′-extension 5.8S rRNA probe (upper panel) and a 5.8S rRNA internal probe (lower panel). (D) Cap 4 formation is not affected by RNAi-mediated SNIP knockdown. Primer extensions were performed on the RNAs described above with a γ-32P-labeled oligonucleotide that hybridized to the intron portion of SL RNA. Primer extension stops correlate with cap 4 base or ribose methylations. A sequence ladder derived from sequencing a plasmid-based copy of T. brucei SL RNA with the primer extension oligonucleotide is provided for comparison with the primer extension products.

SNIP is a nuclease involved in the final trimming of the 3′ ends of several snRNAs, including SL RNA. Superficially, cap 4 formation was unaffected by the absence of SNIP activity; however, our assay may have missed upstream changes in cap 4 structure that will be examined elsewhere. These data indicate that SNIP is not part of the exosome since SNIP knockdown did not result in the accumulation of 5.8S rRNA intermediates associated with exosome subunit knockdowns (2) SNIP did not copurify with TAP-tagged exosome components (2, 3).

SNIP localizes to the nucleoplasm of T. brucei.

Inhibition of nuclear export resulted in the accumulation of 3′-end-extended SL RNAs, indicating that 3′ processing is initiated after nuclear egress (22). To better understand the spatial progression of the SL RNA maturation pathway, SNIP was localized within the cell.

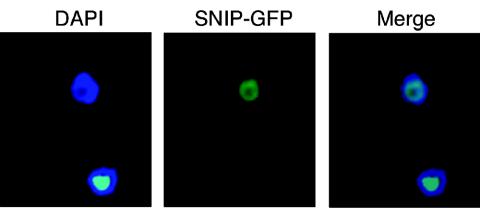

We generated clonal T. brucei cell lines constitutively expressing SNIP with a C-terminal GFP translational fusion. SNIP-GFP localized to a ring of nucleoplasm in vivo (Fig. 5), corresponding to the distribution of nuclear DNA as visualized by the DAPI staining pattern. The nucleoplasmic localization pattern of SNIP-GFP did not overlap with the nucleolus, which does not stain intensely with DAPI (21, 22). All of the 24 clonal SNIP-GFP cell lines demonstrated nucleoplasmic localization for SNIP-GFP; enzymatic activity of the fusion was not examined.

FIG. 5.

SNIP-GFP localizes to the nucleoplasm. Cells were transfected with pHDsnip-GFP, which contains the full-length ORF of SNIP lacking a stop codon, followed by the ORF of eGFP. The DNA of the nucleus and kinetoplast were visualized by counterstaining with DAPI. Clonal stable transfectants were subjected to fluorescence microscopy.

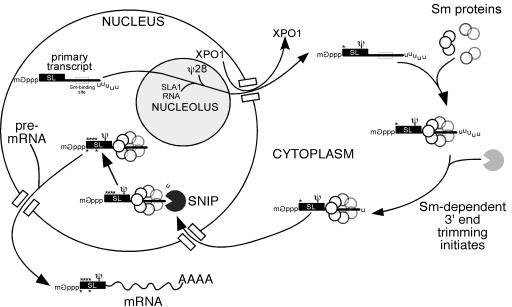

These localization studies revealed a nucleoplasmic presence for SNIP. When considered in light of the SmD1 RNAi phenotype for SL RNA, this intracellular location was consistent with the final 3′ trimming of SL RNA occurring after cytosolic trafficking. Given the predilection of SNIP for U residues, the incompletely trimmed SL RNA seen under nuclear retention conditions (22) indicated that the mere presence of both SL RNA and SNIP in the nucleoplasm was not sufficient for 3′-end maturation. In the case of SL RNA, SNIP function may be dependent on cytosolic formation of the SL RNP and/or prior trimming of the nascent SL RNA by other nucleases.

DISCUSSION

Here we report the identification and characterization of T. brucei SNIP, a 3′→5′ exonuclease required for final 3′-extension removal of SL RNA, U2 and U4 snRNAs, U3 snoRNA, and 5S rRNA. Recombinant SNIP had an in vitro preference for the exonucleolytic removal of U residues commonly found at the 3′ ends of small RNAs and minimal activity on G or C ribonucleotides. Substrates for SNIP in vivo have G or C at their mature 3′ ends, whereas nonsubstrates have U or A residues at the mature 3′ ends (6). SNIP is an essential protein in T. brucei. The absence of SNIP activity did not obviously affect 5′-end cap 4 methylation of SL RNA but led to a reduction in the stability of U2 snRNA and U3 snoRNA. A SNIP-GFP fusion localized to the nucleoplasmic periphery and was excluded from the nucleolus. We propose that SNIP executes the final 3′-end cleavages from SL RNA as part of a minimally two-step 3′-end processing pathway.

What are the distinguishing features of SNIP substrates? The mature 3′ end of T. brucei SL RNA is C142 (6). The next ribonucleotide downstream of the mature SL RNA 3′ end is U143. Viewed in isolation, the 3′ mapping data fit with the SNIP RNAi results that show a 1-nt 3′ extension upon SNIP RNAi induction and with the in vitro SNIP substrate preference for U ribonucleotides. In the case of the SL RNA, SNIP trims the single exposed U left over from the previous non-SNIP nuclease cleavage. None of the other SNIP substrates have U ribonucleotide residues immediately downstream of their mature 3′ ends (Table 1). Clearly, other criteria exist that differentiate SNIP substrates from nonsubstrates.

TABLE 1.

Summary of RNAs examined as SNIP substrates and their characteristics

| RNA | SNIP substrate | RNA Pol | Function | 5′ cap | Sm site and trafficking | 3′-end sequencea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SL RNA | Yes | II | trans splicing | m7G/cap4 | Yes | TGACCTCCAC↓TCTTTTTATTTT |

| U2 snRNA | Yes | III | Splicing | m2,2,7G | Yes | GGAGCGCGAC↓GGTCGCGAACATTTT |

| U3 snoRNA | Yes | III | snoRNA | m2,2,7G | No | CAGAAGGATC↓CTTTTTTTT |

| U4 snRNA | Yes | III | Splicing | m2,2,7G | Yes | ACCACGGGTG↓GGAGGTCCTTTTT |

| U5 snRNA | No | III | Splicing | Not m7G, m2,2,7G, or ppp | Yes | TTTGGGGTGT↓C-N25-TTTTTTT |

| U6 snRNA | No | III | Splicing | Not m7G or m2,2,7G | No | TATAGCTTTT↓CGG |

| tRNAAla | No | III | Translation | p | No | AACTTCTCCA↓CGTTTT |

| 5S rRNA | Yes | III | Translation | ppp | No | TTGTACTCTC↓CCAAACTTTTTT |

| 5.8S rRNA | No | I | Translation | p | No | CAGTGTCGAA↓TAT-N20-TTTTTT |

↓, mature 3′ end. Termination elements are underlined.

Aside from the 3′-extension primary sequence, five additional characteristics (Table 1) can be ruled out for SNIP substrate specificity: transcription class, RNA function, an m7G-derived 5′-cap structure, Sm protein interaction, and trafficking. Other factors directing SNIP may include (i) 3′-end secondary structure, (ii) a not-yet-defined SNIP recognition sequence element, or (iii) indirect SNIP interaction via an unidentified RNA-binding protein partner(s).

Our working model (Fig. 6) for SL RNA 3′-end formation is that substrate SL RNA is transcribed by RNA Pol II as a poly(U) 3′-end-extended precursor and translocated into the cytoplasm by a nuclear export complex containing XPO1 (22). In the cytoplasm, SL RNA is bound by Sm proteins (21), and in an Sm protein-dependent manner the SL RNA 3′ extension receives a primary set of postnuclear export cleavages that produces 3′-end-extended SL RNA of 143 nt. The Sm-bound SL RNA is imported into the nucleus, where it encounters SNIP, which removes the remaining 1-nt 3′ extension to the base of SL RNA stem-loop III at C142. After 3′-extension removal and other maturation steps, including cap 4 acquisition in the substrate, SL RNA is trans spliced. We cannot exclude the possibility that all 3′ processing initiates in the nucleus after cytosolic trafficking. Experimental inactivation of the nuclear import pathway for SL RNA would allow localization of the primary 3′-end-trimming events, as would direct identification of the nuclease(s) involved.

FIG. 6.

Model for SL RNA 3′-end formation. Substrate SL RNA is transcribed by RNA Pol II as a poly(U) 3′-end-extended precursor and translocated into the cytoplasm by a nuclear export complex containing XPO1 (22). SL RNA is bound by Sm proteins (21), and the SL RNA 3′ extension receives Sm-dependent primary cleavages that produces 3′-end-extended SL RNA of 143 nt. The Sm-bound SL RNA is imported into the nucleus for final modifications. SNIP removes the remaining SL RNA 1-nt 3′ extension to C142. Mature SL RNA is then competent for trans splicing.

Substrate SL RNA intracellular trafficking is upstream of SNIP function. Trapping nascent SL RNA in the nucleus with the XPO1 inhibitor leptomycin B demonstrated that substrate SL RNA in proximity with SNIP was insufficient for 3′-extension removal. Although these trapped nuclear SL RNAs were partially trimmed 3′, the mature 142-nt form of SL RNA was completely absent from these cells (22). In this artificial circumstance, the SL RNA and SNIP may have been isolated physically from one another, or perhaps additional factors are required for recognition of the SL RNA substrate. In contrast to the intracellular trafficking requirements for SL RNA, U3 snoRNA and 5S rRNA are not known to exit and reenter the nucleus as part of their biogenesis, and yet they are both substrates for SNIP.

Our identification of SNIP as the enzyme involved in the terminal stage of SL RNA 3′-end formation begs the question as to the identity and cellular location of the initial SL RNA 3′-processing event. In other systems the exosome is known to contain activities involved in the processing of snRNAs. The exosome is a nuclease complex that can be implicated en masse (2) for SL RNA processing. If exosome membership is not a characteristic of the initial 3′-processing enzyme, we will continue to examine the database for likely candidates.

Similar to T. brucei SL RNA, Xenopus precursor U1 snRNA 3′-extension removal also requires intracellular trafficking. In both cases, at least two nuclease activities are required for U1 snRNA 3′-extension removal. In Xenopus the first nuclease activity is cytosolic and acts upon the m7G-capped form of U1 snRNA. The second nuclease activity is nuclear and requires the m2,2,7G-capped form of U1 snRNA. The conversion of m7G to m2,2,7G-capped snRNAs in Xenopus oocytes requires bound Sm proteins (8) as a prerequisite for nucleus reentry.

SNIP is not an ortholog of any individual S. cerevisiae REX family member by the criteria of overall sequence similarity or enzymatic activity. The RNAi-mediated knockdown of SNIP was lethal, whereas S. cerevisiae REX1, REX2, REX3, or REX1:REX2:REX3 knockouts were viable (15). A key difference that may account for the lethality phenotype in T. brucei is the destabilization of some unprocessed RNAs. SNIP has substrate specificities distinct from any single S. cerevisiae REX subunit. REX1 and REX2 are both involved in 5.8S rRNA maturation and REX1, REX2, and REX3 have overlapping substrate specificities for U5 snRNA, whereas SNIP does not cleave 5.8S rRNA or U5 snRNA.

The localization of SNIP is consistent with the presence of a nucleoplasmic SL RNA processing center that provides the final maturation steps prior to trans splicing. This spatial separation creates a critical subcellular sequestration of mature substrate SL RNA from the cytosolic mRNA seen by the translational machinery. Our studies have shown that incomplete cap 4 methylation correlates with a decrease in polysome loading (23). To further examine the possibility and components of such a structure, we have initiated efforts aimed at purification of SNIP-interacting proteins, as well as determining the localization of other SL RNA maturation enzymes. SNIP may copurify with other Sm-dependent processing activities of the SL RNA and other snRNAs; passage through a nucleoplasmic RNA-processing center could mark the end of SL RNA adolescence and the beginning of its marriage to mRNA.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ruslan Aphasizhev, Larry Simpson, and Wade Winkler for oligonucleotides and helpful suggestions with the in vitro exonuclease assay; Danielle Leuenberger and Carla Koehler for TOM70-His6; C. C. Wang for 29-13 cells; Kent Hill for YTAT cells and for use of the Zeiss fluorescence microscope; Keith Matthews for the α/β-tubulin intragenic RNase protection probe; and Sean Thomas, Scott Westenberger, Jesse Zamudio, Bidyottam Mittra, and Carmen Zelaya for stimulating discussion and comments on the manuscript.

G.M.Z. was a predoctoral trainee on Microbial Pathogenesis Training Grant 2-T32-AI-07323. This study was supported by NIH grant AI 056034 to D.A.C. and N.R.S.

Footnotes

This work is dedicated to the memory of Pauline “Pesh” Katz (1923-2004).

REFERENCES

- 1.Aphasizhev, R., and L. Simpson. 2001. Isolation and characterization of a U-specific 3′-5′-exonuclease from mitochondria of Leishmania tarentolae. J. Biol. Chem. 276:21280-21284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Estévez, A. M., T. Kempf, and C. Clayton. 2001. The exosome of Trypanosoma brucei. EMBO J. 20:3831-3839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Estévez, A. M., B. Lehner, C. M. Sanderson, T. Ruppert, and C. Clayton. 2003. The roles of intersubunit interactions in exosome stability. J. Biol. Chem. 278:34943-34951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hendriks, E. F., A. Abdul-Razak, and K. R. Matthews. 2003. tbCPSF30 depletion by RNA interference disrupts polycistronic RNA processing in Trypanosoma brucei. J. Biol. Chem. 278:26870-26878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hernandez, N. 1985. Formation of the 3′ end of U1 snRNA is directed by a conserved sequence located downstream of the coding region. EMBO J. 4:1827-1837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hitchcock, R. A., G. M. Zeiner, N. R. Sturm, and D. A. Campbell. 2004. The 3′ termini of small RNAs in Trypanosoma brucei. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 236:73-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huang, Q., and T. Pederson. 1999. A human U2 RNA mutant stalled in 3′ end processing is impaired in nuclear import. Nucleic Acids Res. 27:1025-1031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kuersten, S., M. Ohno, and I. W. Mattaj. 2001. Nucleocytoplasmic transport: Ran, beta and beyond. Trends Cell Biol. 11:497-503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mandelboim, M., S. Barth, M. Biton, X.-H. Liang, and S. Michaeli. 2003. Silencing of Sm proteins in Trypanosoma brucei by RNAi captured a novel cytoplasmic intermediate in SL RNA biogenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 278:51469-51478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Perumal, K., and R. Reddy. 2002. The 3′ end formation in small RNAs. Gene Expr. 10:59-78. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shevelev, I. V., and U. Hübscher. 2002. The 3′-5′ exonucleases. Nat. Mol. Cell. Biol. 3:1-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sturm, N. R., and D. A. Campbell. 1999. The role of intron structures in trans-splicing and cap 4 formation for the Leishmania spliced leader RNA. J. Biol. Chem. 274:19361-19367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sturm, N. R., J. Fleischmann, and D. A. Campbell. 1998. Efficient trans-splicing of mutated spliced leader exons in Leishmania tarentolae. J. Biol. Chem. 273:18689-18692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sturm, N. R., M. C. Yu, and D. A. Campbell. 1999. Transcription termination and 3′-end processing of the spliced leader RNA in kinetoplastids. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19:1595-1604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van Hoof, A., P. Lennertz, and R. Parker. 2000. Three conserved members of the RNase D family have unique and overlapping functions in the processing of 5S, 5.8S, U4, U5, RNase MRP and RNase P RNAs in yeast. EMBO J. 19:1357-1365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van Hoof, A., and R. Parker. 1999. The exosome: a proteasome for RNA. Cell 99:347-350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang, Z., J. C. Morris, M. E. Drew, and P. T. Englund. 2000. Inhibition of Trypanosoma brucei gene expression by RNA interference using an integratable vector with opposing T7 promoters. J. Biol. Chem. 275:40174-40179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Winkler, W. C., A. Nahvi, and R. R. Breaker. 2002. Thiamine derivatives bind messenger RNAs directly to regulate bacterial gene expression. Nature 419:956-962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wirtz, E., S. Leal, C. Ochatt, and G. A. M. Cross. 1999. A tightly regulated inducible expression system for conditional gene knockouts and dominant negative genetics in Trypanosoma brucei. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 99:89-101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang, H., M. L. Moss, E. Lund, and J. E. Dahlberg. 1992. Nuclear processing of the 3′-terminal nucleotides of pre-U1 RNA in Xenopus laevis oocytes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 12:1553-1560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zeiner, G. M., S. Foldynová, N. R. Sturm, J. Lukes, and D. A. Campbell. 2004. SmD1 is required for spliced leader RNA biogenesis. Eukaryot. Cell 3:241-244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zeiner, G. M., N. R. Sturm, and D. A. Campbell. 2003. Exportin 1 mediates nuclear export of the kinetoplastid spliced leader RNA. Eukaryot. Cell 2:222-230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zeiner, G. M., N. R. Sturm, and D. A. Campbell. 2003. The Leishmania tarentolae spliced leader contains determinants for association with polysomes. J. Biol. Chem. 278:38269-38275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]