Abstract

Much of the gene regulatory circuitry of phage λ centers on a complex region called the OR region. This ∼100-bp region is densely packed with regulatory sites, including two promoters and three repressor-binding sites. The dense packing of this region is likely to impose severe constraints on its ability to change during evolution, raising the question of how the specific arrangement of sites and their exact sequences could evolve to their present form. Here we ask whether the sequence of a cis-acting site can be widely varied while retaining its function; if it can, evolution could proceed by a larger number of paths. To help address this question, we developed a λ cloning vector that allowed us to clone fragments spanning the OR region. By using this vector, we carried out intensive mutagenesis of the PRM promoter, which drives expression of CI repressor and is activated by CI itself. We made a pool of fragments in which 8 of the 12 positions in the −35 and −10 regions were randomized and cloned this pool into the vector, making a pool of PRM variant phage. About 10% of the PRM variants were able to lysogenize, suggesting that the λ regulatory circuitry is compatible with a wide range of PRM sequences. Analysis of several of these phages indicated a range of behaviors in prophage induction. Several isolates had induction properties similar to those of the wild type, and their promoters resembled the wild type in their responses to CI. We term this property of different sequences allowing roughly equivalent function “sequence tolerance ” and discuss its role in the evolution of gene regulatory circuitry.

Complex gene regulatory circuits can have a large number of interlocking components. This degree of interconnectivity raises two issues. First, how did these circuits evolve? Second, how can we understand the behavior of these existing circuits and predict their behavior in the face of small changes in parameters such as promoter strength? For these and other reasons, we have been analyzing the behavior of the regulatory circuitry of phage λ in the intact system. This system is probably the best-understood complex circuit (38, 39). Most, if not all, of the regulatory interactions have been identified, and most of these are well characterized at the mechanistic level. Previous analysis of this circuit generally has been carried out in uncoupled systems (such as the use of reporter genes and fusions with the lac promoter), an approach necessary to disentangle the causality of this system. With a circuit diagram in hand, it is now possible to return to the intact circuit and ask how particular changes affect the overall operation of the system.

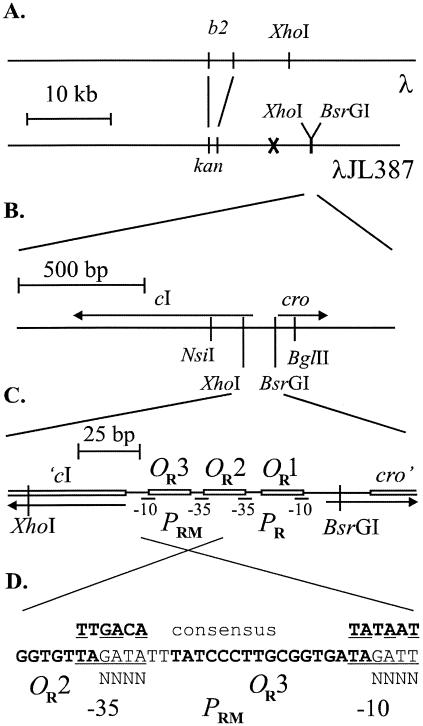

Many of the critical interactions in the λ circuit center on a complex regulatory region termed the OR region (Fig. 1C). This ∼100-bp region is densely packed with cis-acting sites, including two promoters and three sites to which both the CI and Cro repressors can bind (38). In addition, the promoters and repressor-binding sites overlap extensively. CI and Cro regulate the expression of these promoters, and their actions determine the overall behavior of the regulatory circuitry.

FIG. 1.

Structure of the λJL387 vector and sequence of PRM. All maps are to scale, as indicated. (A) Comparison with l+. The indicated BsrGI and XhoI sites in λJL351 were introduced; that for BsrGI is the only BsrGI site to the right of the XhoI site. The letter X in the λJL387 map indicates the site of the XhoI site removed by filling in. (B) Maps of cI and cro. The NsiI and BglII sites shown were used for routine subcloning of the OR region and are present in both λ and λJL351. (C) Close-up of the OR region showing the locations of the promoters and operators and those of the new XhoI and BsrGI sites. Cro and CI both bind to sites OR1, OR2, and OR3. λJL387 contains v1 and v3 mutations (not shown; see text) not present in λJL351 or the wild type. (D) Sequence of the PRM promoter, inverted from the usual order of the λ map. The locations of OR3 and the end of OR2 are shown in bold; the −35 and −10 regions of PRM are underlined, and the NNNN sequences represent positions that were randomized (Fig. S3 of the supplemental material contains more details). Above the sequence is that of a consensus promoter. Positions at which PRM matches it are underlined.

The λ circuitry is bistable—that is, lambda can exist in either of two stable epigenetic states, the lytic state and the lysogenic state. A choice is made between these two states soon after infection; this choice involves regulatory elements (CII, CIII, and PRE [see reference 14]) that we do not consider here. Once a particular choice is made, it is stabilized by the interactions of CI or Cro with the OR region. In the lytic state, Cro is made from PR. At moderate concentrations, Cro binds preferentially to OR3, repressing PRM but not affecting its own expression; at higher levels, Cro also binds to OR1 and OR2, partially repressing its own synthesis. Hence, if Cro but not CI is present, this pattern is perpetuated. In the lysogenic state, by contrast, CI but no Cro is present; CI binds tightly to OR1 and cooperatively to OR2 but only weakly to OR3. Binding to OR1 and/or OR2 represses PR. CI bound to OR2 also stimulates expression of PRM about 10-fold (31); hence, CI acts in this context as an activator of its own expression in a positive feedback loop. Again, if CI but not Cro is present, this pattern is perpetuated by the behavior of the circuitry. At higher CI levels, PRM is partially repressed by binding of CI to OR3, both directly and by a cooperative long-range interaction with CI molecules bound at a distant regulatory region termed OL (7, 8, 40).

It is of interest to ask how this particular arrangement and spacing of cis-acting sites benefits the phage, how it arose during the course of evolution, and how the sequences of the sites were refined during the course of evolution. We chose to address the last question by asking whether one of these cis-acting sites, the PRM promoter, could tolerate substantial genetic changes and still allow relatively normal behavior of the intact circuitry.

Although unstimulated PRM is a relatively weak promoter, it differs from the consensus σ70-specific promoter in only 4 positions out of 12 (Fig. 1D). Is its resemblance to the consensus important, or could it tolerate substantial changes and still preserve its function? Previous work and our unpublished studies have identified several point mutations in PRM that weaken or strengthen it, and these mutations affect the behavior of the λ circuitry (12, 31, 42, 43; our unpublished work), suggesting that its sequence is important. It is unclear whether more extensive changes in the promoter would destroy the operation of the circuitry. For instance, promoter mutations might also affect other processes operating in this complicated regulatory region. In this work, we have tested the effects of extensive changes in PRM on the operation of the λ circuitry.

In order to facilitate this and similar studies, it would be useful to be able to clone variants of the OR region into a wild-type background. This would allow one, for example, to use intensive site- or region-directed mutagenesis to create large pools of recombinant molecules and then to introduce these into intact genomes and assess their effects by using the powerful screens and selections afforded by λ genetics. This approach could be extended to combinatorial approaches in which many combinations are made and tested simultaneously. We describe here the isolation of a cloning vector that allows such manipulations in the OR regulatory region and use it to carry out extensive mutagenesis of PRM. We find that sequences differing markedly from the wild-type sequence can confer nearly normal behavior on the λ circuitry.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents and media.

Restriction enzymes and T4 DNA ligase were from New England Biolabs (Beverly, Mass.), Boehringer-Mannheim, and Promega Corp. (Madison, Wis.). Taq DNA polymerase was from Roche. Polymyxin B and mitomycin C were from Sigma. Oligonucleotides were from Midland Certified Reagent Corp. (Midland, Tex.). Shrimp alkaline phosphatase was from United States Biochemicals. Streptavidin-coated paramagnetic beads (product CM01N), in a 1% (wt/wt) slurry, were from Bangs Laboratories (Fishers, Ind.); 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (X-Gal) was from Research Products International Corp. The λ DNA isolation kit was from QIAGEN (Valencia, Calif.). The Phagemaker λ packaging kit was from Novagen (Madison, Wis.). TE was 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) plus 1 mM EDTA; BTE was TE plus 0.1 M NaHCO3; TZ8 (7) was 100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) plus 1 mM MgSO4 plus 10 mM KCl. LB and tryptone broth were as previously described (27) and supplemented with antibiotics as appropriate at the levels previously described (27), except that lysogens of λJL351 and the PRM variants were grown with 10 μg of kanamycin per ml and were not fully resistant to 30 μg/ml. LBGM and LBMM were LB with 1 mM MgSO4 and either 0.2% glucose or 0.2% maltose, respectively (27). DNA sequencing was carried out as previously described (27). For each MD phage (see Table 2), DNA sequencing was done on a PCR product extending from the distal end of cro to the end of cI; sequencing was done from the end of cro through about the first third of cI, spanning the entire cloned region.

TABLE 2.

PRM variants that form turbid plaquesa

| Name | Turbidity | Lysogeni- zation | −35 region | −10 region | No. of differences from:

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| W | C | |||||

| WT | ++++ | Yes | GATA | GATT | 0 | 3 |

| MD1 | ++++ | Yes | TCCT | TCCT | 7 | 5 |

| MD2 | ++++ | Yes | CCAC | TCAT | 7 | 5 |

| MD3 | ++++ | Yes | GACT | TCTC | 5 | 4 |

| MD4 | ++++ | Yes | CCAG | GCAT | 6 | 6 |

| MD5 | ++++ | Yes | ATAC | GACT | 5 | 6 |

| MD7 | +c | No | CTAT | TAGA | 7 | 6 |

| MD8 | +++++ | Unstable | TCTC | GAGT | 4 | 6 |

| MD9 | +++c | Yes | TCAG | GAGT | 5 | 6 |

| MD10 | +++c | No | AGCC | GAGT | 5 | 5 |

| MD11 | +d | Unstable | CCCA | GTTT | 4 | 5 |

| MD12 | +++c | Unstable | CATC | AATT | 3 | 5 |

| MD13 | ++++ | Unstable | TGCC | TTTT | 6 | 5 |

| MD14b | ++++ | Yes | GCAT | GACT | 4 | 5 |

| MD15 | +++ | Yes | ACGC | GTAT | 6 | 6 |

| MD16 | ++++ | Yes | GGGT | TATC | 5 | 5 |

| MD17 | ++ | Unstable | CCCA | TTAA | 7 | 4 |

| MD18 | +++ | Yes | CGCA | GTCT | 5 | 5 |

| MD19 | ++++ | Yes | GCAC | AACT | 5 | 5 |

| MD20 | +++ | Yes | GCTT | GAAG | 4 | 5 |

| MD21 | +++ | Yes | CTAC | GGCT | 6 | 7 |

| MD22 | + | Yes (few) | CATA | AATT | 2 | 4 |

| MD23 | ++++ | Yes | GACG | TGAA | 6 | 3 |

| MD24 | +++ | Yes | GCCA | TGAA | 6 | 3 |

| MD25 | ++++ | Yes | CTCA | GGCT | 5 | 5 |

| MD26 | ++++(+) | Yes | GCCT | GGCT | 5 | 5 |

| MD27 | +++ | Yes (few) | GGAC | TAGA | 6 | 5 |

| MD28 | +++ | Yes | CATG | GAAT | 3 | 4 |

| MD29 | +++ | Yes | GATA | GATT | 0 | 3 |

| MD30 | ++++ | Yes | CCCA | CAGT | 5 | 4 |

| MD31 | ++++d | No | CAAC | GGAC | 6 | 6 |

| MD32 | ++++ | Yes | TAGC | ACAT | 6 | 5 |

| MD33 | +++ | Yes | ACGC | TAGT | 6 | 5 |

| MD34b | + | Yes (few) | GACC | GTGT | 4 | 4 |

| MD35c | ++ | No | ACAC | GAAC | 6 | 6 |

| MD36b | + | Yes | CCAC | AAGT | 6 | 6 |

| MD37 | ++++ | Yes (few) | GGCT | TAAA | 6 | 3 |

| MD38 | +++ | Yes (few) | ACCT | TAGT | 6 | 4 |

| MD39 | +++ | Yes | CTAA | TGCT | 6 | 5 |

| MD40 | + | No | CCCA | GGTA | 5 | 6 |

| MD41 | ++++d | No | CATG | GAGA | 4 | 6 |

| MD42 | +++ | Yes | CTAA | CTCT | 6 | 6 |

| MD43 | +++ | Yes | GCAT | GTTT | 4 | 6 |

| MD44 | ++ | Yes | TCCA | AAGT | 5 | 4 |

| MD45 | ++++ | Yes | GGCA | GTAT | 4 | 3 |

| MD46 | +++ | Yes | TGCT | GTTT | 5 | 6 |

| MD47 | +++ | Unstable | CGCC | TCGT | 7 | 5 |

| MD48 | ++++ | Unstable | TCCC | TAAA | 7 | 4 |

| MD49 | ++++b,d | Yes | GTCA | TAAAC | 5 | 2 |

| MD50 | ++++ | Unstable | ACAA | TCTT | 5 | 5 |

| MD51 | ++++ | Yes | TACC | TCAT | 7 | 3 |

| MD52 | ++++ | Yes | TACG | GAGT | 4 | 4 |

| MD53 | ++++ | Yes | CTCC | CCAT | 7 | 5 |

| MD54 | ++ | Yes | TTCG | CGAT | 7 | 5 |

| MD55 | ++ | Yes (few) | CACT | TTGT | 6 | 4 |

| MD56 | ++++(+) | Unstable | CCCA | CAAC | 6 | 4 |

| MD57 | +++ | Yes | CAAA | ACCT | 5 | 5 |

| MD58 | ++++(+) | Yes | CGAC | GAGT | 5 | 6 |

| MD59 | ++++ | Yes | CAGC | TATT | 4 | 4 |

| MD60 | ++ | Yes | TCTA | AAGT | 4 | 5 |

| MD61 | ++ | Yes | GAAC | AAGT | 4 | 4 |

| MD62 | ++d | No | ACTC | GAGT | 4 | 6 |

WT, wild type. All mutants made large plaques the size of wild-type plaques, except MD28, MD49, and MD58, which made medium-sized plaques, and MD27, which formed small-to-medium-sized plaques. MD6 was lost. Turbidity: +, faintly turbid; ++, fairly turbid; +++, less turbid than the wild type; ++++, turbidity like that of the wild type; ++++(+), possibly more turbid than the wild type; +++++, more turbid than the wild type. For the lysogenization assay, plaques were streaked onto kanamycin plates. Yes, many colonies; Yes (few), few but healthy-looking colonies (see text); Unstable, unstable-lysogen phenotype (see text); No, no lysogens observed. In the sequences, the last four bases of the −35 and −10 regions are listed; in both positions, the first two bases of both the −35 and −10 regions are TA. The number of differences are given between the mutant and wild-type PRM (W) or the consensus (C). A database file in FilemakerPro format containing the above information is available in the supplemental material.

These isolates had additional mutations. MD14 had an OR2 mutation (CAACATGCACGGTGTTA, where the underlined nucleotide is C in the wild type). MD34 had two mutations in OR3, (1T→C and 9G→T, top strand in Fig. 1D numbered from left to right). MD36 had an E10V mutation in cI. MD49 had a 1-bp insertion in the −10 region, as shown. Plaques of MD34, MD36, and MD55 resembled those of cII mutants, but they did not contain mutations in cII.

These isolates had a less turbid central zone that varied in size.

Plaques were more uniform in turbidity across the plaque than those of the wild type (see text).

Bacterial and phage strains and plasmids.

A list of many of the strains and plasmids used is given in Table1. Phage strains not listed include intermediates in the construction of λJL387 (see supplemental material); phage isolated from the pool of PRM variants, termed MDx, where x is an allele number (MDx phage differ from λJL351 only by the changes listed in Table 2); MDWx phages, isolated as described below, which differ from λJL163 only by the altered PRM (x has the value of its MDx forebear); and phages bearing PRM::lacZ fusions. In addition, phages HK106, HK244, HK542 clear, and HK544, which were originally isolated and shown to have λ immunity by T. S. Dhillon (personal communication), were obtained from R. A. Weisberg; phages CL707 and CL715, isolated in Davis, Calif., and also found to have λ immunity (Dhillon, personal communication), were obtained from T. S. Dhillon. Plasmids not listed include those used to make reporter fusions and derivatives used to make MDW phages.

TABLE 1.

Strains used in this study

| Strain, phage, or plasmid | Relevant genotype | Vector | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bacterial strains | |||

| JL2497 | N99 lacZΔM15/F′ lacIqlacZΔM15::Tn9; used as wild type | 29 | |

| JL5434 | JL468/ptac::N+/pLR1 | 23; this work | |

| JL6039 | JL2497 hflKCa | This work | |

| JL6689 | Same as RW3480 = N99 ΔX74(lacIPOZY) | R. A. Weisberg | |

| JL6740 | JL6689/pJWL615/pA3B2 | This work | |

| JL6853 | JL6689/pGB2/pJWL486 | This work | |

| Y1089 | hflA150 linked to Tn10 | 17, 56 | |

| Phage strains | |||

| λ+ | Wild type | 27 | |

| λJL121 | λRS45 bor::kan | This work | |

| λJL161 | λ v1 v3 bor::kan | 27 | |

| λJL163 | λ+bor::kan | 27 | |

| λJL301 | PR::lacZ derivative of λJL121 | This work | |

| λJL351 | Control for cloning vector for OR region; OR+ | This work | |

| λJL387 | Cloning vector for OR region; v1 v3 | This work | |

| λJL611 | Derivative of λJL121 lacking distal part of lac operon | This work | |

| λJL628 | Same as λJL611, including λ OL operators distal to lacZ | This work | |

| λRS45 | ′amp-′lacZYA imm21 | 50 | |

| Plasmids | |||

| pA3B2 | Δ-35 lacP::cI; provides low level of CI; Cmr | pACYC184 | 51 |

| pACYC184 | Origin of p15A; compatible with pGB2- and ColE1-derived plasmids; Cmr | pACYC184 | New England Biolabs |

| pBS(−) | Cloning vector with extensive polylinker; Ampr | ColE1 | Stratagene |

| pER194 | bor::kan (called pE194 in reference 27) | pBR322 | 27 |

| pGB2 | Spcr; compatible with pACYC184- and ColE1-derived plasmids | 3 | |

| pJAM93 | lacI+ | pGB2 | 34 |

| pJWL319 | lacI+ | pBR322 | 34 |

| pJWL334 | Modified polylinker (Fig. S4 in supplemental material) | pBS(−) | This work |

| pJWL344 | NsiI-BglII interval spanning OR from λJL163 cloned into pJWL334 (Fig. S1 in supplemental material), modified by introducing XhoI and SpeI sites by site-directed mutagenesis | pBS(−) | This work |

| pJWL345 | Same as pJWL344 but carrying v1 v3 in OR | pBS(−) | This work |

| pJWL464 | Structure shown in Fig. S1 in supplemental material | pBS(−) | This work |

| pJWL465 | PCR of λ sequence from 32850 to 34499b | pBS(−) | This work |

| pJWL466 | pJWL465 cut with XhoI and SalI and religated | pBS(−) | This work |

| pJWL467 | pJWL465 cut with XhoI, followed by filling in and religation | pBS(−) | This work |

| pJWL468 | Structure like that of pJWL344, with XhoI and BsrGI sites introduced by site-directed mutagenesis | pBS(−) | This work |

| pJWL471 | Like pJWL468 but carrying v1 v3 | pBS(−) | This work |

| pJWL486 | pACYC184 cut with BstYI and HindIII and religated (control for pA3B2) | pACYC184 | This work |

| pJWL502 | Like pJWL344 but missing SpeI and SalI sites (see text) | pBS(−) | A. Watson; this laboratory |

| pJWL615 | lacIq promoter driving lacI | pGB2 | This work |

| pLR1 | Δ-35 lacP::cI; provides low level of CI; Ampr | pBR322 | 51 |

| pRS414 | Vector for making lacZ protein fusions | pBR322 | 50 |

| pRS1274 | Vector for making lacZ operon fusions (described as pRS528 in reference 50) | pBR322 | 50 |

| ptac::N+ | Fusion of λ N gene to tac promoter; Cmr | pACYC184 | N. C. Franklin |

JL6039 was made by P1 transduction of JL2497 with Y1089 as the donor. Tetracycline-resistant transductants were selected and screened for plaque morphology of λ. Those giving small, turbid plaques with a low plating efficiency were saved.

The PCR primer at 32850 introduced a HindIII site for cloning.

Maps of many of the plasmids made in the present work are shown in Fig. S1 and S4 of the supplemental material; details of their construction are available upon request. pJWL615 was made from pJAM93 (34) by cutting with EcoRI and MluI (which cuts within lacI) and cloning in a PCR product made with a pJWL319 template and primers that introduced the lacIq mutation into the lacI promoter. pJWL486 was made from pACYC184 by cutting with BstYI and HindIII, filling in with Klenow, and religation.

Construction of cloning vector λJL387 and preparation of vector arms.

For a description of the construction of cloning vector λJL387 and the preparation of vector arms, see Fig. S1 and S2 of the supplemental material.

Preparation of doped PRM pools.

A collection of DNA fragments bearing randomized bases in the eight positions shown by the NNNN sequences in Fig. 1D was prepared as outlined in Fig. S3 of the supplemental material.

Cloning in λJL387.

Vector arms in equimolar amounts at a total concentration of 75 μg/ml were mixed with a twofold molar excess of the doped PRM pool, treated with DNA ligase overnight at 16°C in a total volume of 10 μl, and packaged with a commercial packaging kit (Novagen). From 0.75 μg of input DNA we recovered only ∼20,000 plaque-forming phage, far fewer than expected from the stated efficiency of this kit (∼107 plaques per μg of ligation mixture), and infer that ligation or packaging was inefficient.

Subcloning of PRM variants.

The vector pJWL502 (from Andrea Watson) was the same as pJWL344 (Fig. S1C of the supplemental material), except that it lacked the SpeI site; also, the SalI site had been removed by cutting, filling in, and ligation; hence, the HincII site within OR was unique. pJWL502 was cut with NsiI and HincII as a backbone; inserts were a PCR fragment (with λJL163 as the template) from the NsiI site to a BsiHKAI site at codon 2 of cI and BsiHKAI-HincII fragments from PCR products of various PRM variants. The resulting plasmids lacked the XhoI and BsrGI sites while retaining the variant PRM and were used in two ways. First, the PRM variants were crossed into a wild-type background by a cross with λJL161; recombinants were identified as turbid-plaque formers, verified by DNA sequencing, and termed MDWx. Second, to make protein fusions of these promoters with lacZ, the plasmids were used as PCR templates with the primers GGGGGGGATCCTTAAGGCGACGTGC and CCCCCGAATTCAACCTCCTTAGTAC, followed by digestion with EcoRI and BamHI and cloning into pRS414. The resulting protein fusions contained the PRM variants and the first 18 amino acids of CI fused to lacZ. Codons in cI are numbered beginning not with the N-terminal Met, since this is removed posttranslationally (45, 46), but with the following Ser.

Modification of Simons vectors.

We modified the Simons vector λRS45 (50) in three ways (detailed in the supplemental material). First, we isolated a Kanr derivative, allowing selection of lysogens. Second, we deleted the distal part of the lac operon, from the middle of lacY to the end of the operon (7). Finally, we made another derivative in which a variant of the λ OL region was placed downstream of lacZ. These steps created a pair of phages, λJL611 (shown in Fig. S4 of the supplemental material) and λJL628, without and with the OL variant, respectively. These phages were crossed with derivatives of pRS414 bearing various PRM variants (see above) to create reporter phages used in the assay described below. In derivatives of λJL628 with PRM::lacZ protein fusions, the OL site lay 3.6 kb from OR, slightly closer than in the phages of Dodd et al. (7) (3.8 kb) and more distant than in λ (2.46 kb).

Reporter assays.

β-Galactosidase assays were performed as previously described (7), with several modifications, with the Molecular Devices Spectra MAX 340PC plate reader. Overnight cultures were diluted 1:6,000 with shaking in tubes in 3 ml of LBGM without and with graded amounts of isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) at 37°C to 1 × 108 to 3 × 108 cells per ml. Cell density was measured by determining optical density at 600 nm (OD600) with a plate reader (250 μl of culture per well); 50 μl of culture was added to 150 μl of TZ8 assay buffer (TZ8 plus 2.7 μl of β-mercaptoethanol per ml and 2.5 μl of 2% polymyxin B per ml). Assays were run in triplicate in flat-bottom 96-well plates (Evergreen Scientific) at 28°C for 1 or 5 h after addition of 50 μl of 0.4% ONPG (o-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactopyranoside) dissolved in TZ8. Units were defined by the following formula: 1,000 × (ΔOD420/min)/(OD600 × 1.5 × volume of culture in milliliters). Units defined in this way are roughly comparable to Miller units (32).

For each PRM variant, assays for reporter gene function were carried out with two pairs of strains. In each pair, the host carried either pA3B2, which provided a low level of CI (JL6740), or pJWL486, a derivative of pACYC184 (like pA3B2) but lacking cI (JL6853). The pairs differed in whether the fusion had the OL variant distal to lacZ. In all cases, single lysogens were used (37). Strains with pA3B2 carried pJWL615 as a source of Lac repressor; various levels of CI were supplied in these strains by adding graded amounts of IPTG.

Distinguishing vector from recombinants.

Most recombinants formed clear plaques. These were distinguished from the λJL387 vector, which bears v1 and v3 and also forms clear plaques, as follows. The v1 and v3 mutations are present in λvir, which can grow in a λ lysogen. λvir also contains a third mutation, v2, in OL1, allowing expression of the PL operon. CI binds poorly to the mutant operators and cannot repress the lytic genes of λvir. Since the only essential gene product from the PL operon is the N protein, λv1 v3 should be virulent if N is provided in trans, as in strain JL5434. λ and a cI mutant could not form plaques on JL5434, but λ v1 v3 and λJL387 formed small, clear plaques. Hence, clear plaques formed on JL2497 were tested individually for the ability to plate on JL5434. Alternatively, phage were plated on a 10:1 mixture of JL2497 and JL5434; λ v1 v3 and λJL387 formed clear plaques, while λ, λ cI, and recombinants formed turbid plaques.

Prophage induction.

Experiments were carried out as previously described (27), with two exceptions. First, after that study we changed the brand of UV lamp used for irradiation and found that the set point for the wild type changed from 5 to 12 J/m2, a difference we attribute to changes in the spectral properties of the lamp relative to those of the meter (International Light model IL1400A) used to measure its output. Second, phage titers were determined with lawns made from exponentially growing cells (JL2497 was grown to 2 × 108/ml in LBMM, centrifuged, and resuspended in 1/10 volume of TMG [27]),rather than the starved overnight lawns used in the previous studies. This change gave higher and more reproducible titers.

RESULTS

Approach.

Although λ has been widely used as a cloning vector, it has seldom been used in this way for analyzing λ itself. As described below, we developed a vector that allows us to clone fragments carrying only the OR region and a small portion of cI. We then used this vector to carry out cassette mutagenesis of the PRM promoter and analyzed progeny with properties resembling those of wild-type λ.

We judged the resemblance of the behavior of PRM variants to that of the wild type by several criteria. First was the ability to grow lytically, which is not a demanding criterion since PRM has no role in lytic growth. Second was the ability to establish and maintain a stable lysogenic state. Expression of CI from PRM is required for maintenance of this state. Third was the ability to undergo prophage induction, or the “genetic switch,” in which the regulatory state changes from lysogenic to lytic upon induction of the host SOS system (26, 41).

Design of the cloning vector.

The cloning vector used, termed λJL387 (Fig. 1), has several useful features. First, it carries a kanamycin resistance marker replacing a portion of the b2 region, allowing selection of lysogens. Second, it has two new restriction sites flanking the OR region (Fig. 1), both arising by single-base changes: a unique, silent XhoI site located at codons 12 to 13 of cI, and a BsrGI site at the start of the PR transcript. These sites were used in preparing vector DNA for cloning (Fig. S2 of the supplemental material). Third, to distinguish the vector from recombinants bearing inserts in the OR region, it contains two mutations in the OR operators, v1 in OR2 and v3 in OR1. These mutations prevent lysogeny (16), so the cloning vector formed clear plaques. Recombinants forming turbid plaques could easily be recognized by screening for this phenotype. In addition, we developed genetic tests to distinguish recombinants forming clear plaques from the vector (see Materials and Methods).

λJL351, which differs from the cloning vector only in that it lacks mutations in the OR operators, was used as a wild-type control for the behavior of recombinants. This phage differed phenotypically from wild-type λ in two ways. First, it formed plaques that were slightly less turbid than the wild type. Second, in prophage induction experiments (not shown), lysogens of this phage were induced at UV doses roughly half of those of the wild type (see Discussion). While these differences can limit the usefulness of this vector, as described below, its use has allowed us to gain initial insights into λ regulation that can then be explored in a more systematic way.

Doping of the PRM promoter.

We made a pool of recombinant DNA molecules in which 8 of the 12 bases in PRM were randomized (Fig. 1D; detailed in the supplemental material). We avoided the first two positions of the −35 and −10 regions because these overlap OR2 and OR3, respectively (Fig. 1D), and changes in these positions would also affect CI and Cro binding. This approach should allow 48 different PRM variants. This recombinant pool was cloned into λJL387, yielding about 20,000 plaque-forming phage; hence, not all possible PRM variants were recovered. The resulting pool of packaged phage was then characterized.

Wild-type λ forms turbid plaques because lysogens arise in the plaque and continue to grow. By contrast, many mutants, including those defective in CI, unable to bind CI (such as the cloning vector), or unable to make CI due to a defect in PRM, form clear plaques. Most of the phage in the pool formed clear plaques, either because they had an OR region from the vector or because PRM was nonfunctional. To assess the fraction of phage containing an insert, individual clear plaques formed on JL2497 were tested on JL5434, which allows phage containing the OR region from the vector, but not those containing an insert, to make plaques (see Materials and Methods); about half of the clear plaques tested were recombinants. On JL2497, about 5% of the total phage formed turbid plaques, indicating that roughly 10% of the lytically competent PRM variants could form turbid plaques. The analysis below suggests that recombinants that are not lytically competent are likely to be rare. In any case, the ability of many isolates to form turbid plaques suggested that these phages might be able to lysogenize and hence that their PRM promoter was functional in the context of the λ circuitry.

Properties of PRM variants.

We purified and further characterized 61 turbid-plaque-forming phage, picking isolates with a range of phenotypes (Table 2). The degree of turbidity varied substantially, from barely turbid to more turbid than λJL351. A few isolates formed plaques more uniformly turbid across the plaque than those of λJL351 or wild-type λ, for which the center of the plaque was more turbid than the periphery.

From all but seven of the isolates, we could readily isolate lysogens by streaking plaques on kanamycin plates. Among those that lysogenized, six isolates gave small numbers of lysogens but the colonies were healthy; most of these isolates also formed plaques less turbid than those of the wild type. Nine other isolates conferred a phenotype we term the unstable-lysogen phenotype; most of the Kanr colonies of these isolates were small, with a few large ones interspersed. Extensive analysis of another phage, λ prm240, which contains a very weak PRM promoter and confers this same phenotype, suggests that the small colonies are single lysogens, which are barely stable (unpublished data), while the larger colonies are multiple lysogens. We infer, but have not confirmed directly, that the present isolates that confer the unstable-lysogen phenotype likewise had very weak PRM promoters and that the stability of lysogens was improved by multiple lysogeny.

One might expect that all of the variants forming turbid plaques would be able to form stable lysogens, but this was not the case. Lysogens arising in a plaque might not be stable in isolation, because the conditions in a plaque differ from those affecting single cells streaked on a plate. Lysogens in a plaque are frequently superinfected by phage. A phage with a weak PRM could follow the lysogenic pathway after infection, since CI is expressed during the establishment phase from the much stronger PRE promoter. Hence, lysogens can arise as a plaque grows. CI is then expressed from PRM, which might be too weak to maintain lysogeny in a single copy. In a plaque, superinfecting phage would also express PRM, leading to higher CI levels through a gene dosage effect and maintenance of lysogeny. In contrast, when cells are isolated by streaking, superinfection no longer occurs and unstable lysogens could switch to the lytic state. In other studies, we have also isolated numerous derivatives of λOR323 (27) that form turbid plaques but not stable lysogens (27; our unpublished data), and the λprm240 phage with the unstable-lysogen phenotype described above forms plaques indistinguishable from those of the wild type.

Sequence analysis of the PRM variants revealed a wide range of PRM sequences (Table 2). Each isolate had a different sequence; MD29 was the same as the wild type. These sequences are further analyzed in the Discussion. We conclude from these findings that a very wide range of PRM sequences is compatible with at least some functioning of the λ regulatory circuitry.

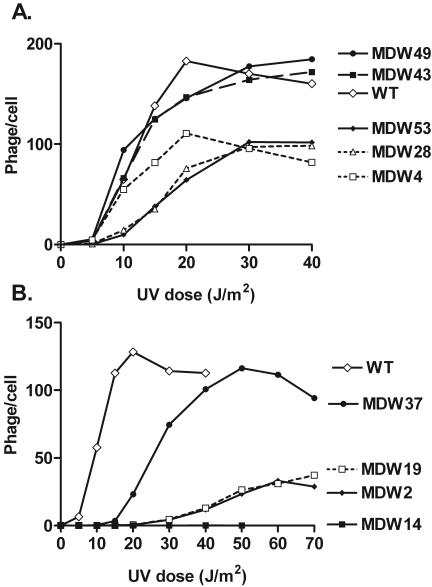

Prophage induction.

All of these phage isolates were able to grow lytically (as expected, since they were isolated as plaques and since PRM has no role in lytic growth), and most could form stable lysogens, indicating that these aspects of the regulatory circuitry were functional. As a more stringent test for normal behavior of the regulatory circuitry, we asked whether the PRM variants could undergo prophage induction. In this process, often termed the genetic switch, a lysogen is induced to switch from the lysogenic state to the lytic state by induction of the host SOS regulatory system (26, 41). Treatment with DNA-damaging agents, such as UV irradiation, activates the co-protease activity of RecA (24), which mediates cleavage and inactivation of CI, leading to prophage induction.

In wild-type λ, prophage induction has several characteristics, each of which can be assessed in the mutants. First, it gives a burst size of about 100 phage per induced cell, comparable to that seen after infection. Second, it exhibits threshold behavior. Induction is inefficient at low levels of DNA damage (such as that which occurs with low doses of UV light) but abruptly becomes efficient at higher doses. Finally, and related, this threshold behavior has a particular set point, which is the dose at which induction becomes efficient. Mutants are known that have changes in any one or combinations of these characteristics (27; our unpublished data).

To identify PRM variants resembling the wild type, we carried out spot tests (not shown) on plates with low and various levels of mitomycin C, an SOS-inducing agent. With increasing mitomycin C concentrations, phage spots became progressively less turbid. Among the isolates that appeared in this test to be as hard as or harder to induce than λJL351, nine were selected for further characterization. Because λJL351 differed somewhat from the wild type in prophage induction, we cloned the variant PRM regions into a wild-type background (see Materials and Methods), giving variants termed MDWx.

Prophage induction experiments were performed (Fig. 2) with single lysogens of these variants. A variety of dose responses was evident. Several isolates showed curves similar to that of the wild type. Some were harder to induce, some gave a small burst size, and mutant MDW14 was scarcely induced at all. We conclude that several different PRM variants can be found that allow relatively normal prophage induction.

FIG. 2.

UV induction of selected MDW phages. Nine variants of PRM were subcloned into a wild-type (WT) background (see text), making phages termed MDW for MD wild type. UV induction curves were obtained for single lysogens as described in Materials and Methods. Results of typical experiments are shown. The data in each panel were obtained in a single experiment.

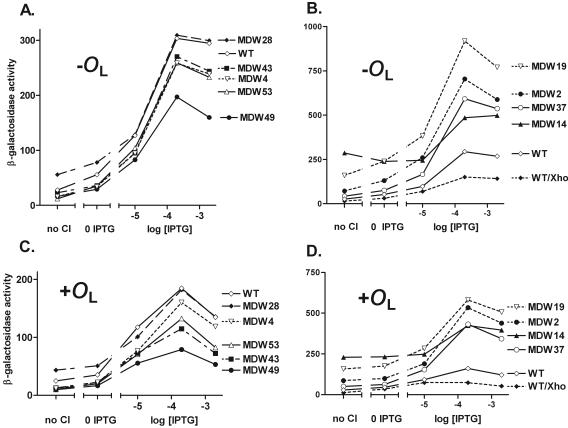

Analysis of promoter strength and regulation.

The above data indicate that, at the level of system behavior, several PRM variants could substitute reasonably well for wild-type PRM. We asked whether their strength and regulation were like those of wild-type PRM when assayed in an uncoupled system. Wild-type PRM is stimulated roughly 10-fold by CI binding to the OR2 operator (30). To test the response of these promoters to graded levels of CI, we supplied CI from a lacP::cI fusion on a plasmid and provided graded levels of IPTG to induce CI expression. To obviate potential complications due to transport of IPTG by Lac permease (7), we used derivatives of the Simons vectors (50) in which most of lacY had been deleted (see Materials and Methods and the supplemental material).

With this system, we analyzed promoter strengths for these nine PRM variants. All of those similar to the wild type were stimulated by CI (Fig. 3A); however, all five variants differed somewhat from the wild type either in their basal (unstimulated) levels, in the maximum level seen in the presence of CI, or in both features. One variant, MDW28, had about the same stimulated level but a higher basal level, three others were stimulated to somewhat lower levels, and MDW49 was about half as strong as the wild type, although this result is hard to interpret since MDW49 has an extra base pair at the end of the PRM −10 region. We conclude that variants similar but not identical to wild-type PRM in this uncoupled assay were able to substitute effectively for wild-type PRM in the context of the intact λ circuitry.

FIG. 3.

Promoter activity and response to various levels of CI. Single lysogens of phages bearing PRM::lacZ protein fusions were prepared. For each, two host strains were used. The first, JL6853, contained no CI; the second, JL6740, contained pA3B2 (51), which is regulated by the Lac repressor and makes low levels of CI. Cells were grown in the presence of the indicated levels of IPTG, and then β-galactosidase levels were measured as described in Materials and Methods. Results of a typical experiment are shown. (A and B) Activity in the absence of OL. (C and D) Activity in the presence of an OL variant located distal to the lacZ reporter. WT, wild type.

The variants that were harder to induce than the wild type contained stronger PRMs, as judged by this uncoupled assay (Fig. 3B [note the change in scale]). The promoter from mutant MDW14, which has a mutation in OR2, was strong in the absence of CI and was stimulated only about twofold by CI, presumably because CI could not bind tightly to OR2. As an additional control in this experiment, wild-type PRM with the XhoI site from λJL351 was found to be about half as strong as its counterpart lacking the XhoI site, a finding that might account for the ease of prophage induction of λJL351 (see Discussion).

PRM is also under negative autoregulation (7, 30), an effect mediated in large part by looping between CI dimers bound at the OR region and those bound at OL (7). We tested the same isolates in a reporter gene construct carrying a version of OL distal to lacZ. We found that the variant promoters also were negatively autoregulated (Fig. 3C and D), that the magnitude of this effect was similar to that seen with the wild type, and that their relative strengths were similar to those seen in the absence of OL.

DISCUSSION

We first discuss the cloning vector used in these studies. We then analyze the sequences of the PRM variants and discuss the mechanisms by which this promoter is expressed. Finally, we consider the implications of our findings for the evolution of complex regulatory circuitry.

Cloning vector.

Use of λJL387 allowed us to carry out localized combinatorial mutagenesis of the OR region. The same strategy can be used with any restriction site that is unique to the right of the XhoI site (Fig. 1). For instance, we have used an NsiI site located beyond cro to carry out extensive modification of the region between this site and the XhoI site (1).

A major advantage of this vector is that it allows us to identify variants with a desired behavior in the context of an intact λ regulatory circuit. In this way, promising candidates for further analysis can readily be identified and then subjected to more intensive analysis, much as is done for rapid screens such as two-hybrid systems or microarrays.

As noted above, the regulatory behavior of λJL351 (the OR+ version of this vector) was not completely wild type. The silent XhoI site in cI (Fig. 1) is responsible for this, at least in part. A phage carrying the XhoI site but not the BsrGI site resembled λJL351 in prophage induction and plaque turbidity, while a phage lacking both sites had a set point and turbidity like those of wild-type λ (data not shown). Also, in the presence of the XhoI site the strength of wild-type PRM was reduced by about 50%, with or without OL (Fig. 3B and D). Perhaps these effects result from changes in the translation efficiency of the leaderless cI mRNA (e.g., see reference 49) or in its stability. In addition, in other versions of the vector, we found (see supplemental material) that minor changes at the start of the PR transcript also affected the λ circuitry, since phages with the XhoI site in cI and an SpeI site or a Bsu36I site instead of the BsrGI site at the start of the PR transcript formed plaques less turbid than those of the XhoI-bearing phage. The OR region appears to be extremely sensitive to several seemingly innocuous changes, which makes our findings obtained with PRM variants even more unexpected (see below).

PRM variants.

Our data indicate that many PRM sequences are compatible with relatively normal regulatory behavior. The ease with which we obtained variants with behavior close to that of the wild type strongly suggests that many possible variants in this region could substitute adequately for wild-type PRM.

We tabulated the changes both for the variants that could form stable lysogens and for those that could not (Table 3). Among the lysogenizing variants, no clear patterns emerged, except that the last position of the −10 region was usually a T. At all other positions, no base was present in more than half of the isolates. The most frequently occurring base matched the consensus at five positions out of the eight that we mutagenized and matched the wild-type PRM sequence at four positions. Possibly the −35 region was able to vary more than the −10 region. Among the much smaller set of variants forming turbid plaques but not stable lysogens, again no clear patterns were evident.

TABLE 3.

Frequency of bases at each positiona

| Type of mutant (n) and base | −35 region position:

|

−10 region position:

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| Lysogenizers (45) | ||||||||

| A | 4 | 13 | 15 | 13 | 8 | 22 | 14 | 5 |

| C | 16 | 17 | 20 | 15 | 4 | 8 | 11 | 2 |

| G | 16 | 7 | 5 | 6 | 18 | 7 | 13 | 1 |

| T | 9 | 8 | 5 | 11 | 15 | 8 | 7 | 37 |

| Turbid-plaque formers- unstable or non- lysogenizers (16) | ||||||||

| A | 4 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 9 | 5 | 5 |

| C | 9 | 9 | 8 | 9 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 3 |

| G | 0 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 8 | 2 | 6 | 0 |

| T | 3 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 6 | 3 | 5 | 8 |

| Clear plaques (9) | ||||||||

| A | 5 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| C | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 0 |

| G | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 6 |

| T | 0 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 1 |

For three classes of mutants—those forming turbid plaques and stable lysogens, those forming turbid plaques but not stable lysogens, and those forming clear plaques—the number of isolates with a given base at each position is tabulated. In each set of numbers, the base in the wild-type sequence is underlined and the consensus base is in bold. For the clear plaques, designated MDCx, the sequences of the −35 and −10 regions are, respectively, as follows: MDC1, AAAT and TTTG; MDC2, ACTA and GGGG; MDC3, CACG and ACGA; MDC4, CACC and ACGG; MDC5, ATAC and GCTT; MDC6, ACGC and TGAG; MDC7, ACTA and TGCA; MDC8, CCCG and GATG; MDC9, CATA and GGGG.

We emphasize that not all PRM sequences were functional. Nine recombinants that formed clear plaques also contained variant PRM sequences (Table 3, footnote a), as expected. We could not identify any reliable distinction between this set and the functional set, except that only one of the former had a T in the last position of the −10 region (Table 3).

PRM variants with very strong promoters might not have been identified in our screen. In other work (J.W.L., unpublished data), we have made and studied a phage carrying the up promoter mutation prmup-1 (a change of the −35 region from TAGATA to TAGACA), which makes PRM ∼10-fold stronger in the absence of CI and four- to fivefold stronger than the stimulated wild type in the presence of CI (31). λprmup-1 has a low plating efficiency and forms very turbid plaques that are heterogeneous in size; perhaps singly infected cells often follow the lysogenic pathway or cannot complete the lytic pathway. Hence, isolates with promoters as strong as or stronger than the prmup-1 promoter might not plate efficiently and might not have been isolated in our screen.

Because PRM is intrinsically a rather weak promoter, it is not surprising that many variants could provide a promoter with roughly equivalent strength. More surprising is that it is very difficult to predict from the sequences of the PRM variants whether they will create a functional promoter in the context of the λ regulatory circuitry. The PRM sequences from many of the phage that can lysogenize bear no recognizable resemblance to the consensus site (see reference 33).

We observed changes in response to CI in some of the PRM variants (Fig. 3 and Table4). At least two related explanations are possible for this finding. First, expression of PRM is stimulated by CI bound to OR2. Activation involves a contact between residues in the DNA-binding domain of CI and the σ70 subunit of RNA polymerase (19, 21, 22, 35). This contact takes place close to the DNA. Subtle, sequence-dependent structural variations in different −35 regions might lead to local variations in the way σ70 interacts with the −35 region, influencing the strength of this interaction, as previously suggested (18). Second, it is known (13, 19) that CI stimulates the isomerization of the closed complex to the open complex (kf), rather than the binding step (KB). Since this transition involves several steps (2, 5), a mutation could alter the response to an activator that stimulates kf by changing which step in open-complex formation is rate limiting.

TABLE 4.

Set points and promoter propertiesa

| Mutant/promoter | Set point for prophage induction | β-Galactosidase activity of PRM::lacZ fusion

|

Induction ratio (with OL) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basal | Stimulated without OL | Stimulated with OL | |||

| WT | 12 | 28, 24, 26, 28 | 303, 293 | 184, 161 | 7 |

| WT/XhoI | 6 | 14, 12 | 150 | 74 | 6 |

| MDW49 | 10 | 16, 10 | 197 | 78 | 6 |

| MDW43 | 12 | 23, 13 | 270 | 114 | 6 |

| MDW4 | 12 | 16, 12 | 258 | 160 | 11 |

| MDW28 | 16-18 | 56, 43 | 309 | 182 | 3.6 |

| MDW53 | 18-20 | 12, 10 | 259 | 132 | 12 |

| MDW37 | 28-30 | 42, 50 | 592 | 432 | 9 |

| MDW2 | ≥45-50 | 72, 87 | 703 | 534 | 7 |

| MDW19 | ≥50 | 160, 158 | 917 | 581 | 3.7 |

| MDW14 | NA | 286, 228 | 485 | 424 | 1.6 |

For the wild type and each mutant, the set point for prophage induction 1 the UV dose giving about 50% of the maximal phage yield (Fig. 2). The value given for WT/XhoI is that for λJL351 (data not shown). For MDW2 and MDW19, the value given may be an underestimate since it is unclear whether induction reached a plateau. NA, not applicable (no induction). Basal β-galactosidase activity levels are listed both for constructs without OL and for constructs with OL; the stimulated values is the maximum level reached in each case (Fig. 3). The induction ratio is the maximum level with OL divided by the average of the basal values listed. Mutants are listed in order of increasing set point.

It is possible that some isolates created new promoters located at positions different from that of natural PRM. The changes do not allow the expression of a promoter that is normally suppressed by the activity of PRM (see reference 52), since nonfunctional PRMs have been both created by mutation of wild-type PRM (54) and found among the present isolates. If the mutations create new promoters, these must arise by virtue of particular substitutions. For all of the isolates tested, except possibly MDW14 (Fig. 3), it is highly likely that the promoter lies at the same site as that in wild-type λ, since these isolates were stimulated by CI, an effect dependent on the exact spatial relationship between PRM and OR2. The promoter cannot lie downstream of the wild-type location, since the A in the AUG start codon of cI is the first nucleotide in the mRNA. Conceivably, one or more of the PRM variants has a different location in the absence of CI. For instance, the MDW4 mutation creates a reasonable −35 region, TTACCA, overlapping OR2 by 3 bp instead of 2, but this would have an 18-bp spacing with the −10 region. A version of PRM termed Δ34 was made by a 1-bp deletion and created a 3-bp overlap with OR2 (53). CI represses this promoter, in contrast to stimulation of MDW4 by CI, so that in the presence of CI the natural promoter must be used by MDW4.

Although several PRM variants had properties similar to those of the wild type in laboratory experiments, the wild-type λ promoter sequence may be more fit in nature, since several different wild isolates of phages with lambda immunity have the same PRM sequence as that of λ. These include HK97 (20) and 933H (36); in addition, we have sequenced the OR regions of HK106, HK244, HK542, HK544, CL707, and CL715 (D. Wert and J. W. Little, unpublished data). Interpretation of these data is complicated by the likelihood that these phages are not reproductively isolated from each other, but they did contain a few other changes in and near the OR region, suggesting that gene flow among them is not exceedingly rapid.

Do the changes in our mutants affect other aspects of the λ circuitry? Preliminary evidence obtained with PR::lacZ operon fusions indicates that in the nine mutants analyzed in detail, the strength of PR was reduced to about 70 to 90% of its wild-type value. This finding is consistent with previous evidence (44) suggesting that a weak UP element for PR may overlap the −35 region of PRM. PR is slightly stronger when the region from −66 to −42 is present than in its absence (44), although this region does not have this effect in a different context. An AT-rich segment within this region matches fairly well with the upstream part of a consensus UP element (44), and a PRM mutation, prm116, in the −35 region that improves this match is known to increase the strength of PR (9). The region changed here in the −35 region of PRM is included in that AT-rich segment, and the match is weakened in the nine variants analyzed.

It is unclear whether other aspects of regulation have also been subtly altered in some variants. If so, perhaps we have chosen phages for which the balance of forces resembles those in the wild type, and restoring balance in this way is relatively straightforward. Evaluation of this possibility must await more detailed analysis of functional interactions in this region. However, comparison between the set points for prophage induction and the promoter strengths provides some evidence for other subtle changes in OR function, as we now discuss.

Prophage induction and promoter strength.

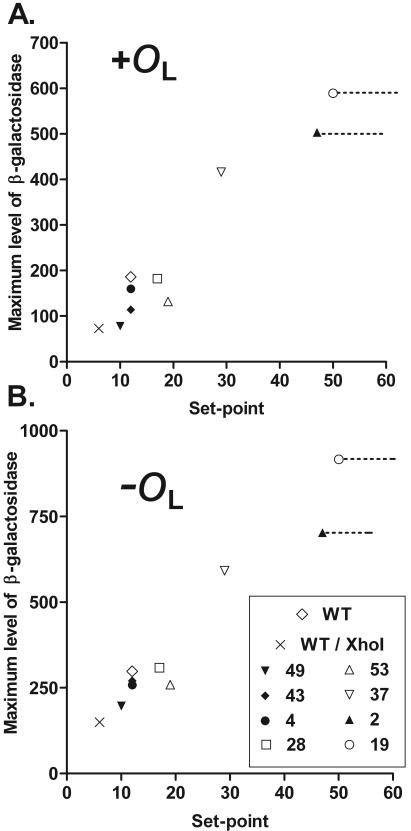

Our evidence suggests a relationship between PRM strength and the set point for prophage induction. Table 4 and Fig. 4 summarize the data from Fig. 2 and 3. For MD2 and MD19, the dashed lines in Fig. 4 indicate the uncertainty in estimating the set point (Table 4). Considering the entire set of mutants, there is a clear correlation between the value of the set point and the strength of stimulated PRM.

FIG. 4.

Correlation between set points and maximal promoter activities. Data from Table 4 were plotted to illustrate a correlation between the set point for UV induction and the maximal promoter strength observed in the presence (A) or absence (B) of the OL site located distal to lacZ. WT, wild type. For MD2 and MD19, dashed lines indicate uncertainty in estimating the set point.

At a mechanistic level, we suggest the following model to account for this correlation. For prophage induction to occur, CI levels must be reduced by RecA-mediated cleavage to a critical level low enough to allow substantial expression of PR. In cells containing more CI due to a stronger PRM, more RecA-mediated cleavage must occur to reach this critical level. It is unclear whether higher doses of UV give higher levels of activated RecA, and hence faster cleavage, or whether higher UV doses lead to more prolonged activation of RecA. Evidence obtained by cleavage of LexA (25; unpublished data) indicates that the initial level of activated RecA is about the same at all of the doses in the dose range used here and that RecA remains activated for longer times at higher UV doses. Hence, for a λ mutant with higher CI levels, a higher UV dose might be needed because RecA needs to remain activated longer to reduce CI levels to a critical value.

This model implies that one could predict the set point from promoter strength; that is, some function of the promoter strength would give the set point and the set point would increase monotonically as promoter strength increased. It is not straightforward to determine what this function is, for several reasons. First, it is hard to predict the CI levels expected for each promoter, owing to negative feedback, conferred mostly by looping with OL. Second, it is not clear how negative feedback and positive feedback change as CI levels drop. Third, the rate of RecA-mediated cleavage almost certainly varies with CI concentrations, both because only CI monomers are efficiently cleaved (4, 6, 11) and because the in vivo level of monomers is probably below the Km for this reaction (11).

Whatever the function relating promoter strength and the set point may be, our data are not completely consistent with the expectation of a monotonic function. Considering the wild type and the group of mutants with set points between 10 and 20 J/m2 (Fig. 4), there is little correlation between promoter strength and the set point. The most likely explanation for this disparity is that some of the changes in the mutants affect other aspects of OR function (see above). We conclude that the strength of PRM plays an important role in controlling the set point, particularly with large changes in PRM strength, but that it is not the only determinant.

The model discussed above suggests that other forces contributing to the set point are the rate of CI cleavage and the CI level at which switching becomes likely. In turn, the latter value is likely controlled by many factors. Some of these, such as cooperative CI binding and looping or efficiency of PRM mRNA translation, are unlikely to be affected by changes in PRM. Others, such as the affinity of CI for its operators or the affinity of Cro for OR3, might be modestly affected by changes adjacent to the operators. In addition, our mutations slightly reduce the strength of PR, although it is uncertain that this would have marked effects on the set point.

The term “robustness” refers to a property that describes the relative insensitivity of a system to changes in certain parameters, such as promoter strength and the affinity of DNA-binding proteins for their targets. An alternative term is “parameter sensitivity” (15, 47, 48), which quantifies how much an output (such as the set point) varies with changes in an input (such as promoter strength). The mathematical treatment of this property has not been extended to bistable switches (M. A. Savageau, cited in reference 27), so that a quantitative treatment of our findings is not possible at present. In addition, it is uncertain that only one input parameter has changed markedly. Qualitatively, however, the set point is not highly resistant to changes in promoter strength; a twofold change in promoter strength usually results in about a twofold change in the set point.

Evolution of gene regulatory circuitry.

We have previously suggested (27) that robustness has played an important role in the evolution of complex circuits in two ways. First, it allows an initial circuit to take a wide variety of forms, provided that the circuit offers a selective advantage (the lysogenic state in the case of λ). Second, as this initial circuit is refined in the later stages of evolution, robustness likewise allows a wider range of pathways for refinement.

An important aspect of this refinement process is evolution of the cis-acting sites to which RNA polymerase and regulatory proteins bind. Evolution of cis-acting sites likely involves two types of changes: changing the relative arrangements and locations of these sites, including spacing between sites, and refining the exact sequences of these sites. The present findings bear primarily on the latter issue.

We find that the sequence of PRM can adopt a wide variety of forms compatible with a functional regulatory circuit. One might use the term “sequence robustness” to describe this property, but the term “robustness” is increasingly being used in different ways, and this would further confuse its meaning. Instead, we offer the term “sequence tolerance” to describe this feature. Sequence tolerance is in a sense complementary to robustness, in that sequence tolerance allows different sequences to confer the same or similar parameter values on the system, rather than making the system tolerant of changes in parameter values as robustness does.

The functional consequences of sequence tolerance are also likely to be complementary to those of robustness, for both the establishment and refinement stages of the evolutionary pathway described above. Sequence tolerance further expands the range of acceptable initial solutions to the regulatory problem. Moreover, as these initial circuits are refined during a subsequent stage of evolution, it allows this refinement process to follow a wider range of pathways. Operating together, parameter robustness and sequence tolerance greatly expand the range of accessible pathways beyond those allowed by either feature alone.

A promoter like PRM is a favorable case for sequence tolerance, since PRM is a weak promoter and multiple sequences can likely provide comparable strength. In contrast, strong promoters like PR and PL are less likely to allow this feature. Use of a weak promoter imposes additional constraints on a bistable system, however. For such systems to operate, the forces stabilizing each epigenetic state must be in balance (e.g., see references 1, 10, and 55). If a system is not in balance, one state can take over even when the other has been established. For instance, two regulatory proteins might stabilize two alternative states; if the two proteins had equal affinities for DNA and equal dimer dissociation constants but were present in markedly unequal amounts, the action of the more abundant one would eventually lead to establishment of the state it stabilized. Accordingly, a protein whose expression is driven by a weak promoter might use other mechanisms, such as tighter DNA binding or dimerization, cooperativity, or increased stability, to compensate for its lower levels.

Our set of variants had a wide variety of phenotypes. This is also likely to be important for evolution, in two ways. First, we do not study λ (or its host) in its natural environment. This environment almost certainly affords a wide variety of selective pressures at different times and places. It is likely that different PRM variants would be advantageous under different conditions. Environmental variability would offer a further expanded set of pathways by which the circuitry could evolve to its present state.

Second, lambdoid phages have a “mosaic” or modular organization, and it is thought that modules assort rather freely among lambdoid phages during evolution. Hence, the immunity region of λ is likely to have evolved at various times in different genome contexts that were subjected to differing selective pressures. For instance, recent studies with phages H-19B and 933W, which express toxins from the late lytic pR′ promoter, show that these phages have a much lower set point for prophage induction (28), and exhibit far higher levels of spontaneous induction, than does λ. It was hypothesized that this low set point confers a selective advantage on the lysogen: If a small fraction of the bacterial population undergoes induction, the resulting toxin causes diarrhea in the vertebrate host, dispersing the surviving bacterial cells in the environment and promoting their spread. In contrast, we have argued that the set point of λ is optimized to allow prophage induction to occur efficiently only at doses of DNA damage likely to kill the host cell.

Shifting selective pressures might facilitate the evolution of PRM sequences. If an immunity region with a PRM with strength comparable to that of λ became associated with a toxin-producing late region, selective pressure for a weakerPRM might result. In a later step, loss of the toxin genes would change the selective pressures, favoring a stronger PRM, but possibly one with a different sequence. We suggest that variable contexts provide yet another way to expand greatly the number of possible pathways for evolution of cis-acting sites such as PRM.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grant GM24178 from the National Institutes of Health.

We are grateful to Stanley Brown, Piero Bianco, Don Court, and Gary Gussin for helpful discussions; Tarlochan Dhillon, Ian Dodd, David Friedman, and Shota Atsumi for communicating unpublished results; Tarlochan Dhillon and Bob Weisberg for strains; Ian Dodd, Andrea Watson, and Naomi Franklin for plasmids; and Carol Dieckmann, Andrea Watson, and Gary Gussin for helpful comments on the manuscript. We thank Alex Blumenkron, Kantad Supamit, and Louise Lin for excellent technical assistance.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jb.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Atsumi, S., and J. W. Little. 2004.. Regulatory circuit design and evolution using phage λ. Genes Dev. 18:2086-2094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buc, H., and W. R. McClure. 1985. Kinetics of open complex formation between Escherichia coli RNA polymerase and the lac UV5 promoter. Evidence for a sequential mechanism involving three steps. Biochemistry 24:2712-2723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Churchward, G., D. Belin, and Y. Nagamine. 1984. A pSC101-derived plasmid which shows no sequence homology to other commonly used cloning vectors. Gene 31:165-171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cohen, S., B. J. Knoll, J. W. Little, and D. W. Mount. 1981. Preferential cleavage of phage lambda repressor monomers by recA protease. Nature 294:182-184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Craig, M. L., O. V. Tsodikov, K. L. McQuade, P. E. Schlax, Jr., M. W. Capp, R. M. Saecker, and M. T. Record, Jr. 1998. DNA footprints of the two kinetically significant intermediates in formation of an RNA polymerase-promoter open complex: evidence that interactions with start site and downstream DNA induce sequential conformational changes in polymerase and DNA. J. Mol. Biol. 283:741-756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crowl, R. M., R. P. Boyce, and H. Echols. 1981. Repressor cleavage as a prophage induction mechanism: hypersensitivity of a mutant λ cI protein to RecA-mediated proteolysis. J. Mol. Biol. 152:815-820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dodd, I. B., A. J. Perkins, D. Tsemitsidis, and J. B. Egan. 2001. Octamerization of lambda CI repressor is needed for effective repression of PRM and efficient switching from lysogeny. Genes Dev. 15:3013-3022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dodd, I. B., K. E. Shearwin, A. J. Perkins, T. Burr, A. Hochschild, and J. B. Egan. 2004. Cooperativity in long-range gene regulation by the λ CI repressor. Genes Dev. 18:344-354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fong, R. S. C., S. Woody, and G. N. Gussin. 1994. Direct and indirect effects of mutations in lambda PRM on open complex formation at the divergent PR promoter. J. Mol. Biol. 240:119-126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gardner, T. S., C. R. Cantor, and J. J. Collins. 2000. Construction of a genetic toggle switch in Escherichia coli. Nature 403:339-342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gimble, F. S., and R. T. Sauer. 1989. Lambda repressor mutants that are better substrates for RecA-mediated cleavage. J. Mol. Biol. 206:29-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gussin, G. N., S. Brown, J. Ferm, and K. Matz. 1987. New mutations in the PRM promoter of bacteriophage lambda. Gene 54:291-297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hawley, D. K., and W. R. McClure. 1982. Mechanism of activation of transcription initiation from the lambda PRM promoter. J. Mol. Biol. 157:493-525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Herskowitz, I., and D. Hagen. 1980. The lysis-lysogeny decision of phage λ: explicit programming and responsiveness. Annu. Rev. Genet. 14:399-445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hlavacek, W. S., and M. A. Savageau. 1995. Subunit structure of regulator proteins influences the design of gene circuitry: analysis of perfectly coupled and completely uncoupled circuits. J. Mol. Biol. 248:739-755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hopkins, N., and M. Ptashne. 1971. Genetics of virulence, p. 571-574. In A. D. Hershey (ed.), The bacteriophage lambda. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 17.Huynh, T. V., R. A. Young, and R. W. Davis. 1985. Constructing and screening cDNA libraries using λgt10 and λgt11, p. 49-80. In D. Glover (ed.), DNA cloning: a practical approach, vol. I. IRL Press, Inc., Boca Raton, Fla.

- 18.Hwang, J. J., and G. N. Gussin. 1988. Interactions between Escherichia coli RNA polymerase and lambda repressor. Mutations in PRM affect repression of PR. J. Mol. Biol. 200:735-739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jain, D., B. E. Nickels, A. Hochschild, and S. A. Darst. 2004. Structure of a ternary transcription activation complex. Mol. Cell 13:45-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Juhala, R. J., M. E. Ford, R. L. Duda, A. Youlton, G. F. Hatfull, and R. W. Hendrix. 2000. Genomic sequences of bacteriophages HK97 and HK022: pervasive genetic mosaicism in the lambdoid bacteriophages. J. Mol. Biol. 299:27-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kuldell, N., and A. Hochschild. 1994. Amino acid substitutions in the −35 recognition motif of σ70 that result in defects in phage lambda repressor-stimulated transcription. J. Bacteriol. 176:2991-2998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li, M., H. Moyle, and M. M. Susskind. 1994. Target of the transcriptional activation function of phage lambda cI protein. Science 263:75-77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Little, J. W. 1984. Autodigestion of lexA and phage lambda repressors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 81:1375-1379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Little, J. W. 1993. LexA cleavage and other self-processing reactions. J. Bacteriol. 175:4943-4950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Little, J. W. 1983. The SOS regulatory system: control of its state by the level of RecA protease. J. Mol. Biol. 167:791-808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Little, J. W., and D. W. Mount. 1982. The SOS regulatory system of Escherichia coli. Cell 29:11-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Little, J. W., D. P. Shepley, and D. W. Wert. 1999. Robustness of a gene regulatory circuit. EMBO J. 18:4299-4307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Livny, J., and D. I. Friedman. 2004. Characterizing spontaneous induction of Stx encoding phages using a selectable reporter system. Mol. Microbiol. 51:1691-1704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mao, C., and J. W. Little. 1998. Mutations affecting cooperative DNA binding of phage HK022 CI repressor. J. Mol. Biol. 279:31-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maurer, R., B. J. Meyer, and M. Ptashne. 1980. Gene regulation at the right operator (OR) of bacteriophage λ. I. OR3 and autogenous negative control by repressor. J. Mol. Biol. 139:147-161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Meyer, B. J., R. Maurer, and M. Ptashne. 1980. Gene regulation at the right operator (OR) of bacteriophage λ. II. OR1, OR2, and OR3: their roles in mediating the effects of repressor and cro. J. Mol. Biol. 139:163-194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miller, J. H. 1972. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 33.Mulligan, M. E., and W. R. McClure. 1986. Analysis of the occurrence of promoter-sites in DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 14:109-126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mustard, J. A., and J. W. Little. 2000. Analysis of Escherichia coli RecA interactions with LexA, λ CI, and UmuD by site-directed mutagenesis of recA. J. Bacteriol. 182:1659-1670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nickels, B. E., S. L. Dove, K. S. Murakami, S. A. Darst, and A. Hochschild. 2002. Protein-protein and protein-DNA interactions of σ70 region 4 involved in transcription activation by λcI. J. Mol. Biol. 324:17-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Perna, N. T., G. Plunkett III, V. Burland, B. Mau, J. D. Glasner, D. J. Rose, G. F. Mayhew, P. S. Evans, J. Gregor, H. A. Kirkpatrick, G. Posfai, J. Hackett, S. Klink, A. Boutin, Y. Shao, L. Miller, E. J. Grotbeck, N. W. Davis, A. Lim, E. T. Dimalanta, K. D. Potamousis, J. Apodaca, T. S. Anantharaman, J. Lin, G. Yen, D. C. Schwartz, R. A. Welch, and F. R. Blattner. 2001. Genome sequence of enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7. Nature 409:529-533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Powell, B. S., D. L. Court, Y. Nakamura, M. P. Rivas, and C. L. Turnbough, Jr. 1994. Rapid confirmation of single copy lambda prophage integration by PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 22:5765-5766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ptashne, M. 1992. A genetic switch: phage λ and higher organisms. Cell Press and Blackwell Scientific Publications, Cambridge, Mass.

- 39.Ptashne, M. 2004. A genetic switch: phage lambda revisited. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 40.Revet, B., B. Von Wilcken-Bergmann, H. Bessert, A. Barker, and B. Müller-Hill. 1999. Four dimers of lambda repressor bound to two suitably spaced pairs of lambda operators form octamers and DNA loops over large distances. Curr. Biol. 9:151-154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Roberts, J. W., and R. Devoret. 1983. Lysogenic induction, p. 123-144. In R. W. Hendrix, J. W. Roberts, F. W. Stahl, and R. A. Weisberg (ed.), Lambda II. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 42.Rosen, E. D., and G. N. Gussin. 1979. Clustering of Prm mutations of bacteriophage lambda in the region between 33 and 40 nucleotides from the cI transcription start point. Virology 98:393-410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rosen, E. D., J. L. Hartley, K. Matz, B. P. Nichols, K. M. Young, J. E. Donelson, and G. N. Gussin. 1980. DNA sequence analysis of prm mutations of coliphage lambda. Gene 11:197-205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ross, W., S. E. Aiyar, J. Salomon, and R. L. Gourse. 1998. Escherichia coli promoters with UP elements of different strengths: modular structure of bacterial promoters. J. Bacteriol. 180:5375-5383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sauer, R. T. 1978. DNA sequence of the bacteriophage λ cI gene. Nature 276:301-302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sauer, R. T., and R. Anderegg. 1978. Primary structure of the lambda repressor. Biochemistry 17:1092-1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Savageau, M. A. 1974. Comparison of classical and autogenous systems of regulation in inducible operons. Nature 252:546-549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Savageau, M. A. 1971. Parameter sensitivity as a criterion for evaluating and comparing the performance of biochemical systems. Nature 229:542-544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shean, C. S., and M. E. Gottesman. 1992. Translation of the prophage lambda cI transcript. Cell 70:513-522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Simons, R. W., F. Houman, and N. Kleckner. 1987. Improved single and multicopy lac-based cloning vectors for protein and operon fusions. Gene 53:85-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Whipple, F. W., N. H. Kuldell, L. A. Cheatham, and A. Hochschild. 1994. Specificity determinants for the interaction of λ repressor and P22 repressor dimers. Genes Dev. 8:1212-1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Woody, S. T., R. S. C. Fong, and G. N. Gussin. 1993. A cryptic promoter in the OR region of bacteriophage lambda. J. Bacteriol. 175:5648-5654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Woody, S. T., R. S. C. Fong, and G. N. Gussin. 1993. Effects of a single base-pair deletion in the bacteriophage lambda PRM promoter. Repression of PRM by repressor bound at OR2 and by RNA polymerase bound at PR. J. Mol. Biol. 229:37-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yen, K. M., and G. N. Gussin. 1973. Genetic characterization of a prm mutant of bacteriophage lambda. Virology 56:300-312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yokobayashi, Y., R. Weiss, and F. H. Arnold. 2002. Directed evolution of a genetic circuit. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:16587-16591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Young, R. A., and R. W. Davis. 1983. Efficient isolation of genes by using antibody probes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 80:1194-1198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.