Abstract

Rubrerythrin was purified by multistep chromatography under anaerobic, reducing conditions from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus furiosus. It is a homodimer with a molecular mass of 39.2 kDa and contains 2.9 ± 0.2 iron atoms per subunit. The purified protein had peroxidase activity at 85°C using hydrogen peroxide with reduced P. furiosus rubredoxin as the electron donor. The specific activity was 36 μmol of rubredoxin oxidized/min/mg with apparent Km values of 35 and 70 μM for hydrogen peroxide and rubredoxin, respectively. When rubrerythrin was combined with rubredoxin and P. furiosus NADH:rubredoxin oxidoreductase, the complete system used NADH as the electron donor to reduce hydrogen peroxide with a specific activity of 7.0 μmol of H2O2 reduced/min/mg of rubrerythrin at 85°C. Strangely, as-purified (reduced) rubrerythrin precipitated when oxidized by either hydrogen peroxide, air, or ferricyanide. The gene (PF1283) encoding rubrerythrin was expressed in Escherichia coli grown in medium with various metal contents. The purified recombinant proteins each contained approximately three metal atoms/subunit, ranging from 0.4 Fe plus 2.2 Zn to 1.9 Fe plus 1.2 Zn, where the metal content of the protein depended on the metal content of the E. coli growth medium. The peroxidase activities of the recombinant forms were proportional to the iron content. P. furiosus rubrerythrin is the first to be characterized from a hyperthermophile or from an archaeon, and the results are the first demonstration that this protein functions in an NADH-dependent, hydrogen peroxide:rubredoxin oxidoreductase system. Rubrerythrin is proposed to play a role in the recently defined anaerobic detoxification pathway for reactive oxygen species.

Rubrerythrin is a nonheme iron protein that was originally isolated from the cytoplasm of the anaerobic bacterium Desulfovibrio vulgaris (27). The native protein is purified as a dimer with a subunit molecular weight of 21.9 kDa (41). Although D. vulgaris rubrerythrin (4, 7-9, 12, 27, 30, 35, 42) and the rubrerythrins from a variety of other microorganisms (2, 3, 10, 16, 28, 47) have been extensively studied, its cellular function is still not understood. A number of enzyme activities have been reported for rubrerythrin, including pyrophosphatase (30), ferroxidase (4), and NADH peroxidase (7-9), but which are of physiological significance and the nature of its redox partner proteins have not been established. Even the true metal content of rubrerythrin is still a matter of controversy. The D. vulgaris protein was originally reported to contain two iron atoms per monomer. However, this was subsequently increased to three iron atoms per monomer (18, 34, 35), and more recently the protein was proposed to contain one zinc atom and two iron atoms per monomer (41).

What is not in doubt is that each monomer of rubrerythrin contains two separate structural domains. One is similar to the protein rubredoxin and contains a single iron atom coordinated by four Cys residues (27). This domain appears to contain an iron atom even in the 1Zn/2Fe form of the protein (41). The other domain is comprised of four helices and contains a binuclear center that is coordinated by one His and five Glu residues and one atom of molecular oxygen (35). In the 3Fe form of the protein, the binuclear site in the four-helix domain has spectroscopic and magnetic properties similar to those of other diiron-containing proteins such as hemerythrin. In the 1Zn/2Fe form of the protein, this site is thought to contain one Zn and one Fe atom (41). Crystal structures are available for both the 3Fe and 1Zn/2Fe forms (41), the overall structures of which are very similar.

The metal content and redox state of the purified forms of rubrerythrin from D. vulgaris affect its catalytic activity in vitro. The oxidized form of the 1Zn/2Fe protein has inorganic pyrophosphatase activity (30), although the reduced protein is inactive (29). On the other hand, the oxidized form of 3Fe-rubrerythrin exhibits ferroxidase activity, the O2-dependent oxidation of Fe2+ to Fe3+ (4). A recombinant form of rubrerythrin containing the diiron but not the rubredoxin-like domain did not have ferroxidase activity (4, 18), indicating that both metal sites are required for activity. That rubrerythrin may have a peroxidase-type activity was first demonstrated with the D. vulgaris protein with an artificial electron donor, but this had relatively low activity (9). Subsequently, the peroxidase activity of reduced rubrerythrin was demonstrated with reduced rubredoxin as the electron donor. Rubredoxin was reduced either chemically with stoichiometric amounts of dithionite or enzymatically via spinach ferredoxin-NADP+ oxidoreductase with NADH as the electron donor (7), so a physiologically relevant electron donor was not established.

In contrast to the results with the D. vulgaris proteins, rubrerythrin was purified from the cell extract of the obligate anaerobe Clostridium perfringens by measuring its superoxide dismutase activity (28). Although the metal content of the purified protein was not reported, the amino acid sequence (deduced from the cloned gene) was 52% identical to that of D. vulgaris rubrerythrin and contained the putative metal-binding sites for both the rubredoxin-like and diiron sites. Furthermore, a sod mutant of Escherichia coli expressing the gene (rbr) encoding rubrerythrin from C. perfringens exhibited superoxide dismutase activity. This mutant also had a higher resistance to oxidative stress than a mutant lacking rbr, implying a role for rubrerythrin in scavenging reactive oxygen species (ROS) (28). Rubrerythrin appears to be unregulated by reactive oxygen species in C. perfringens, however, as the transcription levels of the genes encoding rubrerythrin and superoxide dismutase were unaffected by oxidative stress (16). Despite all of this evidence for the C. perfringens rubrerythrin, the D. vulgaris protein did not show detectable superoxide dismutase activity (34).

Evidence for a relationship between rubrerythrin and reactive oxygen species also comes from studies of other microorganisms. For example, a peroxide-resistant mutant of Spirillum volutans contained a high level of rubrerythrin, but no expression could be detected in the wild-type strain, even in the presence of peroxide (3). Cell extracts of the mutant strain also had measurable NADH peroxidase activity (0.07 U/mg), but this was not detected in extracts of the wild type (2). Unfortunately, the protein(s) responsible for the activity was not purified. Similarly, an rbr mutant of the anaerobic pathogen Porphyromonas gingivalis was more sensitive than the wild-type strain to oxygen and peroxide (43). In this case, the transcription of rbr was upregulated in response to exposure of cells to either oxygen or hydrogen peroxide. It therefore appears that rubrerythrin does play some role in the response of anaerobes to reactive oxygen species exposure. In fact, with few exceptions, a gene encoding a homolog of the protein is found in all complete genome sequences currently available for anaerobic and microaerophilic prokaryotes (21). It is therefore essential that the precise function and metal content of rubrerythrin be defined.

Herein we focus on the anaerobic archaeon Pyrococcus furiosus (15). This organism grows optimally near 100°C with either carbohydrates or peptides as a carbon source. Interestingly, in its genome sequence (36), the gene (PF1283) encoding the homologue of D. vulgaris rubrerythrin is adjacent to those encoding rubredoxin and the enzyme superoxide reductase. Superoxide reductase was recently postulated to be a key enzyme in a novel detoxification pathway in anaerobes, where it reduces superoxide to peroxide with rubredoxin as the electron donor (23). An intriguing possibility was that in P. furiosus, rubredoxin also supplied reductant to rubrerythrin, as proposed for D. vulgaris (7), so that it could reduce the peroxide generated by superoxide reductase to water. The goal of this study was therefore to purify rubrerythrin from P. furiosus, to determine its metal content and its catalytic activity, and to examine these and other properties of the recombinant protein. The results show that native rubrerythrin is an iron-dependent peroxidase that does not contain zinc and probably functions in vivo to remove the peroxide produced by superoxide reductase with rubredoxin, ultimately reduced by NADH, as the electron donor.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Growth of microorganisms.

Pyrococcus furiosus (DSM 3638) was routinely grown at 95°C in a 600-liter fermentor with maltose as the carbon source as described previously (6). The cells were harvested by centrifugation and stored at −80°C until needed.

Purification of rubrerythrin from P. furiosus.

All procedures were carried out under anaerobic conditions at 23°C. All buffers were degassed and flushed with Ar and contained 2 mM sodium dithionite unless otherwise stated. Rubrerythrin was identified throughout the purification procedure by its migration after sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) analysis to a position corresponding to a molecular mass of 19 kDa. Frozen cells (250 g, wet weight) were thawed in 750 ml of 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0 (buffer A), containing 2 μg of DNase I per ml. Cells were lysed by incubation at 37°C for 2 h. A cell extract was obtained by ultracentrifugation at 100,000 × g for 1.5 h at 4°C. The resulting supernatant (12,045 mg of protein) was applied to a DEAE Fast Flow column (5 by 30 cm) (Pharmacia, Piscataway, N.J.) equilibrated with buffer A. The solution was diluted 50% with buffer A during loading. Protein was eluted at a flow rate of 12 ml/min with a 10 column volume (5 liter) linear gradient of 0 to 1 M NaCl in buffer A. Fractions of 100 ml were collected.

Rubrerythrin eluted as 100 to 175 mM NaCl was applied. These fractions were combined (2,510 mg), concentrated to 200 ml with a PM10 Amicon membrane, and loaded onto a hydroxyapatite (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.) column (2.6 by 20 cm) equilibrated with buffer A. The protein solution was diluted 50% with buffer A during loading. The adsorbed protein was eluted at 4 ml/min with a 1.2-liter linear gradient of 0 to 1 M potassium phosphate buffer, and 50-ml fractions were collected. Rubrerythrin eluted from the column as 100 to 230 mM potassium phosphate was applied. The fractions containing rubrerythrin (1,906 mg) were combined, solid ammonium sulfate was added to a final concentration of 1.5 M, and the solution was loaded onto a column (2.6 by 11 cm) of phenyl-Sepharose (Pharmacia) equilibrated with buffer A containing 1.5 M ammonium sulfate. Protein was diluted 50% with the equilibration buffer during loading. The adsorbed protein was eluted with a linear gradient (720 ml) of 1.5 to 0 M ammonium sulfate in buffer A at 4 ml/min, and fractions of 25 ml were collected.

Rubrerythrin eluted as 560 to 300 mM ammonium sulfate was applied. Rubrerythrin-containing fractions were combined (307 mg), concentrated through a PM10 Amicon membrane to ≈10 ml, diluted to ≈100 ml with buffer A, and then concentrated to 6 ml. This was applied to a column (2.6 by 60 cm) of Superdex 75 equilibrated with buffer A containing 200 mM NaCl. The column was run at a flow rate of 0.5 ml/min, and 10-ml fractions were collected. Rubrerythrin eluted after 190 ml had been applied to the column. Rubrerythrin-containing fractions (123 mg) were loaded onto a column (2.6 by 13 cm) of Q-Sepharose High Performance (Pharmacia) equilibrated with buffer A. The protein solution was diluted by 60% during loading with buffer A. The column was eluted with a 550-ml linear gradient from 0 to 1 M NaCl in buffer A, and 25-ml fractions were collected. Rubrerythrin eluted as 150 to 270 mM NaCl was being applied. Rubrerythrin-containing fractions (65 mg) were combined and loaded onto a hydroxyapatite column (2.6 by 1 cm) equilibrated with 50 mM BisTris, pH 6.0. The protein solution was diluted 90% with equilibration buffer during loading. The column was run at a flow rate of 1 ml/min, and a linear gradient (40 ml) of 0 to 50% of 1 M potassium phosphate buffer, pH 6.0, was applied, and 2-ml fractions were collected.

Rubrerythrin began to elute as 240 mM potassium phosphate buffer was being applied. Rubrerythrin-containing fractions were combined (56 mg) and loaded onto a Q-Sepharose High Performance column (1.6 by 2.5 cm, Amersham Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden) equilibrated with 50 mM BisTris, pH 7.0 (buffer B). The protein solution was diluted 85% with buffer B during loading. Protein was eluted with a 75-ml linear gradient from 0 to 1 M NaCl in buffer B at a flow rate of 1 ml/min, and 1.5-ml fractions were collected. Rubrerythrin eluted as 210 to 270 mM NaCl was being applied to the column. Rubrerythrin-containing fractions judged pure by SDS-PAGE analysis were combined (26 mg) and stored frozen as pellets in liquid nitrogen until needed.

Cloning and heterologous expression of the P. furiosus rubrerythrin gene.

A pET21 plasmid containing a modified rubrerythrin gene (PF1283) with a His-6 tag at the N terminus (MAHHHHHHGS) was provided by the Southeastern Collaboratory for Structural Genomics at the University of Georgia (20). This was transformed into E. coli strain BL21(λDE3)Star/pRIL, which was grown at 37°C in three variations of M9 minimal medium (39) containing 100 μg of ampicillin and 34 μg of chloramphenicol per ml. Medium M-Zn was unmodified and contained Fe and Zn at concentrations of 10 and 20 μM, respectively. Medium M-Fe lacked added Zn but contained 10-fold the normal Fe concentration (100 μM FeSO4), while medium M-FeZn contained Zn (20 μM) and additional Fe (110 μM total). The recombinant cells were grown in 1-liter cultures until the optical density at 600 nm was 0.6, isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG, 0.4 mM) was added, and the temperature was reduced to 25°C. After 3.5 h, cells were harvested by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C, transferred to an anaerobic chamber containing Ar, and resuspended in anaerobic lysis buffer (10 mM imidazole, 10 mM sodium phosphate, and 0.5 M NaCl, pH 7.4). They were stored in sealed serum bottles under Ar at −80°C until required.

Purification of recombinant rubrerythrin from E. coli.

All steps were carried out under anaerobic conditions at 23°C. E. coli cells (3 to 4 g from 1-liter growth) were thawed at room temperature under a constant flow of Ar in lysis buffer. Phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride was added to a final concentration of 100 μM, and cells were lysed by sonication under a flow of Ar. Cell extracts were centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 20 min at 4°C, and the supernatants were applied to 4-ml Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid His-bind affinity columns (Novagen, Madison, Wis.) equilibrated with lysis buffer. Recombinant rubrerythrin was eluted with 10 mM sodium phosphate, 0.5 M NaCl, and 300 mM imidazole, pH 7.0. Those fractions containing recombinant rubrerythrin as determined by SDS-PAGE electrophoresis were then loaded on a column (1.6 by 2.5 cm) of Q-Sepharose High Performance (Amersham Pharmacia) equilibrated with 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, containing 2 mM sodium dithionite. Protein was diluted 80% with equilibration buffer during loading and was eluted in 2-ml fractions at a flow rate of 1 ml/min with a linear gradient (100 ml) from 0 to 1.0 M NaCl in the equilibration buffer. Recombinant rubrerythrin eluted as 0.3 to 0.4 M NaCl was applied. Fractions containing pure recombinant rubrerythrin as judged by electrophoresis were combined, concentrated through a PM10 Amicon membrane, and stored frozen as pellets on liquid nitrogen until needed.

Enzyme assays.

Peroxidase assays were routinely carried out anaerobically at 85°C in 3-ml glass cuvettes containing 2 ml of 50 mM morpholinepropanesulfonic acid (MOPS, pH 7.5). Rubredoxin (22) and NADH:rubredoxin oxidoreductase (32) were purified as previously described. Rubredoxin (150 μM) reduced by sodium dithionite (200 μM) was used as an electron donor, and hydrogen peroxide (250 μM) was the electron acceptor. The reaction was initiated by the addition of between 2 and 5 μM rubrerythrin or recombinant rubrerythrin. Activity was measured by the rate of rubredoxin oxidation at 490 nm with an extinction coefficient of 9.2 cm−1 mM−1 (22). One unit of peroxidase activity is defined as the amount of enzyme that oxidizes 1 μmol of rubredoxin/min. The same assay conditions were used when NADH was the electron donor except that NADH:rubredoxin oxidoreductase, rubredoxin, and rubrerythrin were added in catalytic amounts (≈0.5 μM) and NADH was used at a final concentration of 150 μM. Its oxidation was measured at 340 nm with an extinction coefficient for NADH of 6.2 cm−1 mM−1 (11).

Superoxide dismutase activity was measured at 50°C by cytochrome c reduction (33), and pyrophosphatase activity was determined at 80°C by the release of inorganic phosphate from sodium pyrophosphate (30). Inorganic phosphate was estimated as described previously (19). Alkaline phosphatase and bovine superoxide dismutase (Sigma Chemical Co.) were used as the positive controls for both assay systems. NADH peroxidase activity was measured anaerobically at 85°C following the oxidation of NADH at 340 nm. The reaction mixture (2.0 ml) included 50 mM N-(2-hydroxyethyl)piperazine-N′-(3-proponesulfonic acid) (EPPS) buffer (pH 8.0) with 1 mM diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid (DPTA) with NADH (0.3 mM) as the electron donor and hydrogen peroxide (0.25 mM) as the electron acceptor. Ferroxidase activity was measured at 25, 50, and 80°C at 315 nm following the conversion of [Fe2+] to [Fe3+] by the addition of rubrerythrin (0.45 to 3.6 μmol/ml) to air-saturated buffer containing 0.12 mM ferrous ammonium sulfate added from a freshly prepared anaerobic solution (4).

Other methods.

Iron and zinc were determined by inductively coupled plasma emission spectroscopy (ICP-M5) at the Chemical Analysis Laboratory of the University of Georgia. The iron content was also determined with a colorimetric iron assay (31). UV and visible spectra were recorded on a Shimadzu UV-2501PC spectrophotometer, and all samples were in 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0. Liquid chromatography-mass spectroscopy analysis was performed at the Mass Spectrometry Laboratory at the University of Georgia. Protein was measured with the Bradford protein assay kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.). Amino acid sequences were aligned with Vector NTI AlignX software (Suite 9.0.0; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.). Phylogenetic trees was constructed with the neighbor-joining method (38) and the minimum evolution method (37), both from MEGA software version 3.0 (26). The p-distance and Poisson correction substitution models were used in both tree-building methods. Bootstrap values were calculated based on 1,000 replicates of the data (14).

RESULTS

Purification of rubrerythrin from P. furiosus.

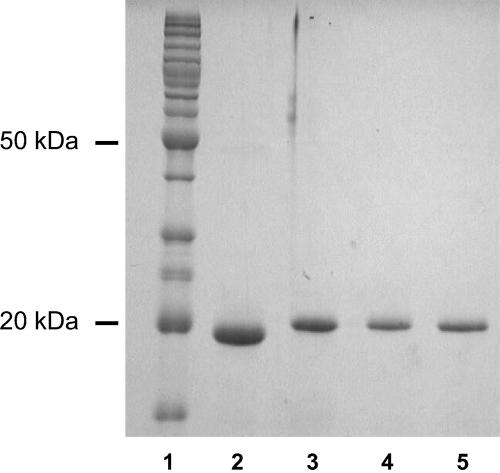

Rubrerythrin was purified to homogeneity from cell extracts of maltose-grown P. furiosus by multistep chromatography. The protein is present in cells in sufficiently high amounts that it can be identified on a one-dimensional SDS-PAGE gel after just one column chromatography step. Rubrerythrin is the only major protein band near 19 kDa in fractions eluting near 150 mM NaCl from the first ion exchange column (data not shown). The purification procedure was carried out with buffers containing sodium dithionite under anaerobic conditions because, as described below, rubrerythrin was found to be soluble only in its reduced state. The procedure yielded approximately 25 mg of rubrerythrin from 250 g of P. furiosus cells (wet weight). This migrated as a single band on a denaturing electrophoresis gel corresponding to a molecular mass of approximately 19 kDa (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

SDS-PAGE (12.5%) of rubrerythrin. Lane 1: standard molecular size markers. Lane 2: native rubrerythrin purified from P. furiosus. Lanes 3 to 5: recombinant rubrerythrin purified from E. coli cells grown on M9-Zn, M9-Fe, and M9-FeZn, respectively. Each lane contained 2 μg of protein.

Its N-terminal amino acid sequence (VVKRTMT-) indicated that the N-terminal methionine residue is cleaved in vivo. According to the gene sequence (PF1283), this should result in a protein of 170 amino acids with a predicted mass of 19,349 Da. This is consistent with the analysis of the purified protein by mass spectrometry, which indicated a mass of 19,377 Da. Analytical gel filtration data showed that native rubrerythrin has a molecular weight of 36 ± 0.3 kDa and therefore appears to be a homodimeric protein. The amino acid sequence of P. furiosus rubrerythrin was 29 and 27% identical to those of the rubrerythrins of D. vulgaris and C. perfringens, respectively.

Purification of recombinant P. furiosus rubrerythrin.

The gene encoding rubrerythrin was successfully expressed in E. coli grown on a minimal medium after induction with IPTG for 3.5 h at 25°C. The presence of recombinant rubrerythrin in cell extracts of E. coli was evident by a protein band corresponding to a molecular mass of 19 kDa after SDS-PAGE analysis. Recombinant rubrerythrin was purified in two steps by affinity and ion exchange chromatography, with yields of 42, 32, and 13 mg from cells (4 g, wet weight) grown on M-Zn, M-Fe, and M-FeZn media, respectively. The three preparations of recombinant rubrerythrin were indistinguishable by SDS-PAGE, although they migrated more slowly than the native protein, presumably because of the additional N-terminal residues that incorporate the His tag (Fig. 1). Liquid chromatography-mass spectroscopy analyses gave subunit molecular weights of 20,615, 20,530, and 20,640 Da, respectively, for the three types of recombinant rubrerythrin, compared with a calculated value of 20,407 Da. Analytical gel filtration data were consistent with a molecular mass of ≈37 kDa for all three forms, indicating that all three are homodimers, like the native protein.

Physical properties of the native and recombinant forms of rubrerythrin.

The metal contents of native rubrerythrin and the three forms of recombinant rubrerythrin are summarized in Table 1. While the native protein contained three Fe atoms/subunit, the values for the recombinant rubrerythrins were much lower, with zinc apparently replacing the iron. Thus, recombinant rubrerythrin purified from E. coli grown on M-Zn medium contained approximately 1 Fe and 2 Zn atoms/subunit, but cells grown in the same medium lacking added zinc and supplemented with iron (M-Fe) yielded recombinant rubrerythrin containing approximately 2 Fe and 1 Zn per subunit. In spite of no added zinc, the M-Fe medium was found to contain 2.0 μM Zn, as determined by ICP-MS, presumably due to contamination by zinc in other medium components. Accordingly, recombinant rubrerythrin obtained from cells grown on M-Zn medium contained approximately 0.5 Fe and 2.5 Zn atoms/subunit (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Metal contents and peroxidase activities of native and recombinant forms of rubrerythrin

| Rubrerythrina | No. of atoms

|

Sp actb (U/mg) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICP-MS

|

Colorimetric [Fe] | |||

| [Fe] | [Zn] | |||

| P. furiosus native form | 2.8 ± 0.2 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 2.9 ± 0.2 | 36.1 |

| M-Fe | 1.9 ± 0.2 | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 1.8 ± 0.1 | 3.1 |

| M-FeZn | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 1.7 ± 0.2 | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 0.7 |

| M-Zn | 0.4 ± 0.1 | 2.2 ± 0.2 | 0.9 ± 0.2 | 0.3 |

Either the native form purified from P. furiosus or the recombinant form purified from E. coli cells was grown on the indicated medium (see the text for details of the media).

Specific activity refers to peroxidase activity with dithionite-reduced rubredoxin as the electron donor and hydrogen peroxide as the electron acceptor.

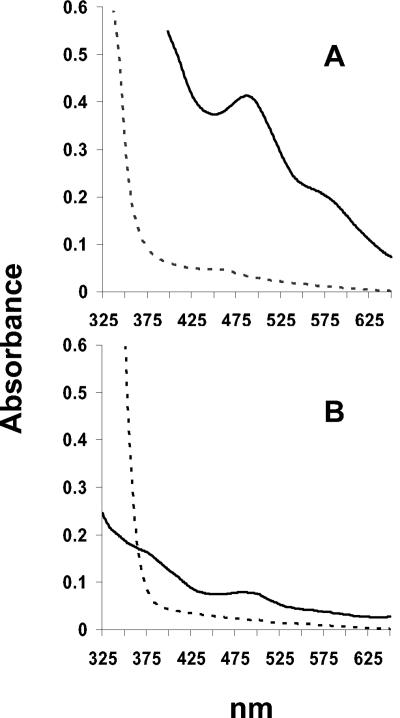

A characteristic of D. vulgaris rubrerythrin is that it is colorless in its reduced state and becomes red upon oxidation due to the redox properties of the rubredoxin-like, monomeric Fe site (27). Similarly, native P. furiosus rubrerythrin in its dithionite-reduced form was colorless as purified, but, strangely, the protein precipitated when exposed to either oxygen (air) or the addition of 10 molar equivalents of either potassium ferricyanide or hydrogen peroxide, e.g., when hydrogen peroxide was added to a 0.1 mM rubrerythrin solution at a final concentration of 1.0 mM. The precipitated protein was red, indicating that the monomeric Fe site was oxidized. This was also evident by an absorbance peak at 490 nm that appeared as the protein changed from colorless to red immediately prior to precipitation (Fig. 2). In contrast, recombinant rubrerythrin proteins containing one or less iron atom per subunit (from cells grown in M-Zn or M-FeZn medium) did not show any features in the visible region upon oxidation (data not shown) and did not precipitate. Thus, the monomeric site in these proteins should contain predominantly zinc. On the other hand, the recombinant rubrerythrin that contained two Fe atoms/subunit, obtained from cells grown in M-Fe medium, did change from colorless to red upon oxidation (Fig. 2). The extinction coefficient at 490 nm was 1.6 mM−1 cm−1. This compares with the value of 10.6 mM−1 cm−1reported for D. vulgaris rubrerythrin (35). This suggests that the monomeric Fe site in the P. furiosus recombinant protein is approximately 15% occupied, while the binuclear site should be almost fully occupied (for an aggregate of two Fe atoms/subunit), but this state did not precipitate. Thus, it appears that the binuclear site is more readily occupied by iron and that the protein precipitates only as the 3Fe form.

FIG. 2.

UV-visible absorption spectra for A) native rubrerythrin and B) recombinant rubrerythrin from E. coli cells grown on M-Fe medium. The reduced samples contained a threefold molar excess of sodium dithionite and were oxidized with a fivefold molar excess of hydrogen peroxide. The final protein concentration in each case was approximately 1 mg/ml (the higher absorbance of the native protein is due to protein precipitation).

Catalytic properties of native and recombinant forms of rubrerythrin.

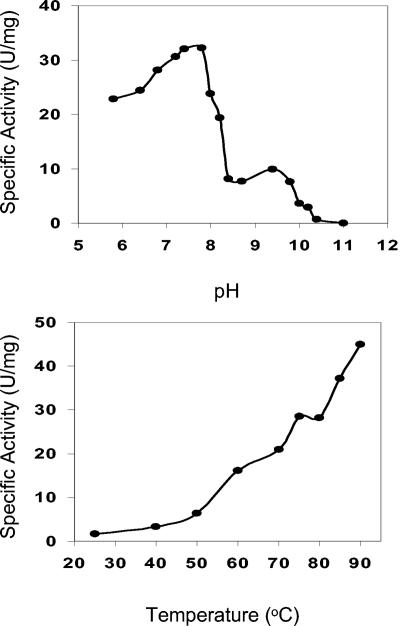

P. furiosus rubrerythrin was assayed for pyrophosphatase, superoxide dismutase, ferroxidase, and NADH peroxidase activities, all of which have been attributed to the rubrerythrins of D. vulgaris and/or C. perfringens (4, 7, 9, 28-30). However, there was no detectable activity with any of the assays for the P. furiosus protein. On the other hand, it did exhibit rubredoxin-dependent peroxidase activity with hydrogen peroxide (250 μM) as the electron acceptor and P. furiosus rubredoxin (150 μM, chemically reduced with sodium dithionite) as the electron donor. The specific activity was 36 U/mg of rubrerythrin at 85°C and pH 7.5, which is comparable to that reported for the D. vulgaris protein measured at 22°C (7). As shown in Fig. 3, the activity showed a bimodal response to pH, with an optimum near 7.8 (at 85°C), and a temperature optimum of ≥90°C (at pH 7.5) (Fig. 3). With standard assay conditions, the apparent Km values, calculated from linear reciprocal plots, were 35 μM for hydrogen peroxide (with a concentration range of 15 to 300 μM with 150 μM rubredoxin) and 70 μM for rubredoxin (over a concentration range of 15 to 270 μM, with 250 μM hydrogen peroxide).

FIG. 3.

Effect of pH (top) and temperature (bottom) on the peroxidase activity of the native form of P. furiosus rubrerythrin. For the temperature measurements, all assays were carried out in 50 mM MOPS (pH 7.5) containing 0.1 mM EDTA, while the pH-dependent assays were performed at 85°C with the following buffers (each at 50 mM): Bis-Tris, pH 5.8, 6.4, 6.8, and 7.2; MOPS, pH 7.4 and 7.8; HEPES, pH 8.0 and 8.2; EPPS, pH 8.4 and 8.7; 3-(N-cyclohexyl amino)-1-propane sulfonic acid (CHES), pH 9.4 and 10.0; 2-(N-cyclohexyl amino)ethanesulfonic acid (CAPS), pH 10.2, 10.4, and 11.

When the recombinant forms of rubrerythrin were assayed under the same conditions, the specific activities were significantly lower, by at least an order of magnitude (Table 1). The 2Fe/1Zn form obtained from cells grown in M-Fe medium was the most active, with approximately 10% of the activity of the native protein. This roughly corresponds to the amount of iron in the mononuclear site (15% occupancy), rather than the binuclear site (approximately 60% occupancy). One would therefore expect the 1Fe/2Zn form (obtained from M-FeZn-grown cells, Table 1) to be virtually inactive, and this form of the protein exhibited only 2% of the activity of the native protein. This is about twice that of the recombinant rubrerythrin form obtained from cells grown in M-Zn, a protein which has an even lower iron content (Table 1).

In the proposed superoxide reductase-dependent pathway of reactive oxygen species detoxification of P. furiosus (23), the ultimate source of reductant for superoxide reduction is NADH, wherein NADH:rubredoxin oxidoreductase reduces rubredoxin, and this in turn supplies reductant to superoxide reductase. To investigate whether NADH via NADH:rubredoxin oxidoreductase and rubredoxin could also supply reductant to rubrerythrin, a system containing all three purified proteins was reconstituted. At 85°C, the reconstituted pathway containing NADH (150 μM), rubredoxin (0.5 μM), NADH:rubredoxin oxidoreductase (0.5 μM), rubrerythrin (0.5 μM), and hydrogen peroxide (250 μM) had a specific activity of 7.0 U/mg of rubrerythrin. However, little or no NADH oxidation activity (<0.5 U/mg) could be measured if any of the components (NADPH, NADH:rubredoxin oxidoreductase, rubredoxin, rubrerythrin, or H2O2) was omitted from the reaction mixture.

DISCUSSION

Representatives of rubrerythrin are present in the majority (23 of 29) of anaerobic and microaerophilic microorganisms for which genome sequences are available. These include organisms from both the bacterial and archaeal domains. There are also three aerobic organisms that contain homologues of rubrerythrin, and these include both bacteria (Magnetococcus and Nostoc spp.) and archaea (Sulfolobus spp.). The crystal structure of D. vulgaris rubrerythrin (12, 29, 41) shows that there are five glutamyl and one histidinyl residue that bind the binuclear metal site, as well as two CXXC motifs that coordinate the rubredoxin-like mononuclear Fe center. However, of the 42 rubrerythrin-like sequences currently available, several of them (7 of 42) do not contain the two Cys motifs and most of these (five of seven) also lack one or more of the Glu residues that bind the binuclear site, leaving only 35 that appear to be homologues of the D. vulgaris protein in that they contain all of the predicted metal-binding sites.

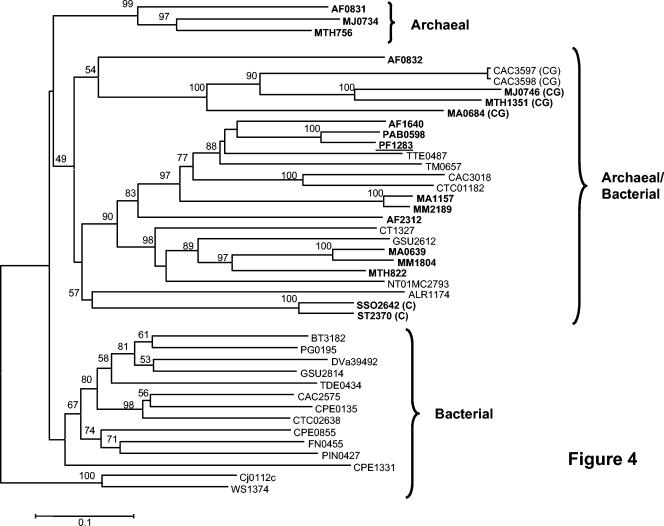

A phylogenetic tree was constructed with all 42 rubrerythrin-like sequences by the neighbor-joining method with the p-distance method (Fig. 4). Similar topologies resulted from different tree-building methods (neighbor-joining versus minimum evolution) and distance estimations (p-distance versus Poisson correction), showing the tree's robustness. It contains two major branches, one with both archaeal and bacterial representatives (which includes the P. furiosus protein) and one with only bacterial proteins (including that from D. vulgaris). There is also a third, smaller branch containing only archaeal proteins. Bootstrap values indicate that the archaeal branch is very well conserved (99%), although both the bacterial and mixed (archaeal/bacterial) branches have much lower bootstrap values (47 and 49%, respectively).

FIG. 4.

Rooted phylogenetic tree of rubrerythrin homologues. Archaeal genes are indicated in bold. Bootstrap values are indicated at the branch points. The bar indicates a branch length equivalent of 0.1 change per amino acid. The Wolinella (WS1374) and Campylobacter (Cj0112c) cluster was used as the outgroup. (C) indicates sequences that do not contain the Cys motifs that coordinate the rubredoxin-like mononuclear site. (CG) indicates sequences that do not contain Cys motifs or the fourth Glu residue conserved in all rubrerythrin homologues. All sequences were obtained from the TIGR website (21) except for the D. vulgaris sequence (46). The position of P. furiosus rubrerythrin (PF1283) is underlined. Abbreviations: AF, Archaeoglobus fulgidus; BT, Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron; Cj, Campylobacter jejuni; CT, Chlorobium tepidum; CAC, Clostridium acetobutylicum; CPE, Clostridium perfringens; CTC, Clostridium tetani; DV, Desulfovibrio vulgaris; FN, Fusobacterium nucleatum; GSU, Geobacter sulfurreducens; NT01MC, Magnetococcus sp.; MTH, Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum; MJ, Methanococcus jannaschii; MA, Methanosarcina acetivorans; MM, Methanosarcina mazei; Nostoc, Nostoc sp.; PG, Porphyromonas gingivalis; PIN, Prevotella intermedia; PAB, Pyrococcus abyssi; PF, Pyrococcus furiosus; SSO, Sulfolobus solfataricus; ST, Sulfolobus tokodaii; TTE, Thermoanaerobacter tengcongensis; TM, Thermotoga maritima; TDE, Treponema denticola; WS, Wolinella succinogenes.

As shown in Fig. 4, the five rubrerythrin homologues that lack both the Cys motifs (which coordinate the rubredoxin site) and one or more of the Glu residues that typically coordinate the binuclear site from Methanosarcina acetivorans (MA0684), Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum (MTH1351), Methanococcus jannaschii (MJ0746), and Clostridium acetobutylicum (CAC3597 and CAC3598) cluster together in the major bacterial/archaeal branch. These are well separated from the two rubrerythrins that lack just the Cys motifs (from Sulfolobus tokodai and Sulfolobus sulfolobus). Interestingly, the expression of CAC3597 and CAC3598 in C. acetobutylicum is induced by oxygen (24), although their functions are not known.

Here we demonstrate that both metal sites (containing only Fe) are needed for the peroxidase activity of P. furiosus rubrerythrin (see below), and so these seven rubrerythrin homologues (including CAC3597 and CAC3598) lacking at least one metal site are unlikely to possess this activity. One might predict that the other members of the archaeal/bacterial branch (Fig. 4) that contain the metal-binding motifs are peroxidases like that of P. furiosus, although additional biochemical analyses are required to define the physiological activities of the proteins in the bacterial-only branch.

P. furiosus rubrerythrin is a homodimeric protein, and this is also true for the only rubrerythrin homologue (containing both metal sites) for which a crystal structure is available, that of D. vulgaris (12, 29, 41). A structure was recently reported for the rubrerythrin sequence homologue from the archaeon Sulfolobus tokodaii, which was given the name sulerythrin (this lacks the rubredoxin-binding domain). Interestingly, a comparison of the two structures showed a rare case of domain swapping to constitute the binuclear site of the Sulfolobus tokodaii protein. The crystal structure for the P. furiosus rubrerythrin has recently been determined (44), and there is also strong evidence for domain swapping in this metal site homologue of the D. vulgaris protein. Thus, the two domain-swapped rubrerythrins (relative to D. vulgaris rubrerythrin) include a sequence homologue (lacking one metal site/domain, in Sulfolobus tokodaii sulerythrin) and a metal site homologue (with Fe in both metal sites, in P. furiosus rubrerythrin), and both are from archaea. Clearly, this domain-swapping phenomenon with rubrerythrin is independent of metal sites, but whether it is a property of archaeal rubrerythrins remains to be seen. At present one cannot predict from an amino acid sequence just which domain structure (“bacterial” or “archaeal”) a particular rubrerythrin adopts.

The true physiological function of rubrerythrin has been the subject of much debate, as a multitude of activities have been attributed to this protein. In this study we have shown that the P. furiosus protein has rubredoxin-dependent peroxidase activity, which is comparable to that reported for archaeal and bacterial (nonrubrerythrin) peroxidases, such as from Archaeoglobus fulgidus (25), Thermus brockianus (45), Bacillus stearothermophilus (17), and Halobacterium halobium (5). The gene encoding rubrerythrin is adjacent to those encoding rubredoxin and superoxide reductase in the P. furiosus genome, consistent with a functional relationship between them (23). Superoxide reductase reduces superoxide to hydrogen peroxide and thereby plays a major role in the detoxification of reactive oxygen species in anaerobes such as P. furiosus (23).

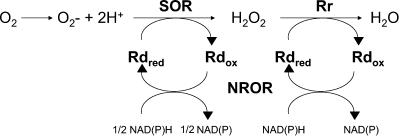

In a recent assessment of the superoxide reductase-dependent pathway (1), the most fundamental unanswered question was what happens to the peroxide produced by superoxide reductase. The answer appears to be, at least in part, that it is reduced to water by rubrerythrin, which functions as a rubredoxin:hydrogen peroxide oxidoreductase. The reductant for this reaction ultimately comes from NADH, with the same mechanism (NADH:rubredoxin oxidoreductase and rubredoxin) that provides electrons for the reduction of superoxide by superoxide reductase. This is illustrated in Fig. 5. It is also shown here that this pathway can be reconstituted in vitro, where electrons from NADH serve to reduce hydrogen peroxide to water with NADH:rubredoxin oxidoreductase, rubrerythrin, and rubredoxin as the intermediate electron carriers.

FIG. 5.

Proposed role of rubrerythrin (Rr) in the superoxide reductase (SOR)-dependent pathway of reactive oxygen species (ROS) detoxification in anaerobic microorganisms. Modified from Fig. 3 in reference 24. Rd, rubredoxin; red, reduced; ox, oxidized; NROR, NADH:rubredoxin oxidoreductase.

Rubrerythrin is present at a relatively high concentration in cell extracts of maltose-grown P. furiosus cells, as shown by the fact that it is readily seen on an SDS-PAGE gel after only one purification step. Superoxide reductase and rubredoxin are also present at high concentrations (22, 23). Furthermore, microarray studies indicate that the genes encoding rubrerythrin, superoxide reductase, and rubredoxin are among the most highly expressed genes in the P. furiosus genome when the organism is grown under anaerobic (non-oxidative stress) conditions (40). This makes it very unlikely these genes will be upregulated even further in response to oxidative stress. Indeed, preliminary analyses indicate that the addition of hydrogen peroxide to a culture of P. furiosus does not have a significant affect on the expression of these three genes (C.-J. Sun and M. W. W. Adams, unpublished results). These data suggest that anaerobically grown P. furiosus is “armed” and responds readily via the superoxide reductase pathway to an oxidative challenge.

The three recombinant forms of P. furiosus rubrerythrin all contained much less than the three Fe atoms per subunit found in the native protein purified from P. furiosus biomass, although the overall metal contents were approximately 3 ions/subunit where the balance was zinc. Unfortunately, little is known about how simple (mono- and binuclear) metal centers are assembled in any organism. Consequently, there is no information as to why P. furiosus only inserts iron into its rubrerythrin, while E. coli inserts predominantly zinc. In fact, E. coli mainly inserts zinc rather than iron into the recombinant form of clostridial rubredoxin (13). The lower iron contents of the recombinant forms appeared to be directly related to the lower peroxidase activity of the proteins (relative to native rubrerythrin from P. furiosus), with an approximately 10-fold reduction in peroxidase activity with each equivalent of an iron atom that was replaced by zinc (Table 1).

The binuclear site in the native rubrerythrin-like protein from the aerobic hyperthermophilic archaeon Solfolobus tokodaii appears to contain both iron (0.9 mol of Fe/rubrerythrin monomer) and zinc (0.5 mol of Zn/rubrerythrin monomer). This could be the reason why no activity was detected when it was assayed for superoxide dismutase and inorganic pyrophosphatase (47). In the case of P. furiosus recombinant rubrerythrin, the presence of the N-terminal His tag might interfere with metal ion insertion, protein folding, and/or peroxidase activity. However, the crystal structure (44) of the recombinant protein shows that is fully folded, the metal sites are fully occupied and coordinated by the expected residues, and the His tag is not in close proximity to the proposed active site or the metal centers. It is therefore extremely unlikely that the variable metal contents and variable peroxidase activities of the recombinant proteins are in any way related to the His tag.

The observation that P. furiosus rubrerythrin in its purified reduced state precipitates when oxidized by air, ferricyanide, or peroxide is a puzzling phenomenon. None of the recombinant forms exhibited this property, even the 2Fe/1Zn form, which had significant catalytic activity (10% of the native form) and a mononuclear site containing predominantly iron (as shown by visible absorption). It therefore appears that precipitation requires that the protein be in an almost fully active form with a binuclear center predominantly occupied by iron. Since precipitation is not expected to occur inside the cell, these data may provide indirect evidence that rubrerythrin exists in vivo as a heteromeric multiprotein complex, and such a possibility is currently under investigation.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (GM 60329 and GM 62407).

We thank William B. Whitman for advice about phylogeny and guide tree construction.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adams, M. W. W., F. E. Jenney, M. D. Clay, and M. K. Johnson. 2002. Superoxide reductase: fact or fiction? J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 7:647-652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alban, P. S., and N. R. Krieg. 1998. A hydrogen peroxide resistant mutant of Spirillum volutans has NADH peroxidase activity but no increased oxygen tolerance. Can. J. Microbiol. 44:87-91. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alban, P. S., D. L. Popham, K. E. Rippere, and N. R. Krieg. 1998. Identification of a gene for a rubrerythrin/nigerythrin-like protein in Spirillum volutans by using amino acid sequence data from mass spectrometry and NH2-terminal sequencing. J. Appl. Microbiol. 85:875-882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bonomi, F., D. M. Kurtz, and X. Y. Cui. 1996. Ferroxidase activity of recombinant Desulfovibrio vulgaris rubrerythrin. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 1:67-72. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown-Peterson, N. J., and M. L. Salin. 1993. Purification of a catalase-peroxidase from Halobacterium halobium: characterization of some unique properties of the halophilic enzyme. J. Bacteriol. 175:4197-4202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bryant, F. O., and M. W. W. Adams. 1989. Characterization of hydrogenase from the hyperthermophilic archaebacterium, Pyrococcus furiosus. J. Biol. Chem. 264:5070-5079. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coulter, E. D., and D. M. Kurtz. 2001. A role for rubredoxin in oxidative stress protection in Desulfovibrio vulgaris: catalytic electron transfer to rubrerythrin and two-iron superoxide reductase. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 394:76-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coulter, E. D., N. V. Shenvi, Z. M. Beharry, J. J. Smith, B. C. Prickril, and D. M. Kurtz. 2000. Rubrerythrin-catalyzed substrate oxidation by dioxygen and hydrogen peroxide. Inorg. Chim. Acta 297:231-241. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coulter, E. D., N. V. Shenvi, and D. M. Kurtz. 1999. NADH peroxidase activity of rubrerythrin. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 255:317-323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Das, A., E. D. Coulter, D. M. Kurtz, and L. G. Ljungdahl. 2001. Five-gene cluster in Clostridium thermoaceticum consisting of two divergent operons encoding rubredoxin oxidoreductase-rubredoxin and rubrerythrin-type A flavoprotein-high-molecular-weight rubredoxin. J. Bacteriol. 183:1560-1567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dawson, R. M. C., D. C. Elliot, W. H. Elliot, and K. M. Jones. 1986. Data for biochemical research, 3rd ed., vol. 1. Clarendon Press, Oxford, England.

- 12.deMare, F., D. M. Kurtz, and P. Nordlund. 1996. The structure of Desulfovibrio vulgaris rubrerythrin reveals a unique combination of rubredoxin-like FeS4 and ferritin-like diiron domains. Nat. Struct. Biol. 3:539-546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eidsness, M., S. O'Dell, D. Kurtz, Jr., R. Robson, and R. Scott. 1992. Expression of a synthetic gene coding for the amino acid sequence of Clostridium pasteurianum rubredoxin. Protein Eng. 5:367-371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Felsenstein, J. 1996. Inferring phylogenies from protein sequences by parsimony, distance and likelihood methods. Methods Enzymol. 266:418-427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fiala, G., and K. O. Stetter. 1986. Pyrococcus furiosus sp-nov represents a novel genus of marine heterotrophic archaebacteria growing optimally at 100oC. Arch. Microbiol. 145:56-61. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Geissmann, T. A., M. Teuber, and L. Meile. 1999. Transcriptional analysis of the rubrerythrin and superoxide dismutase genes of Clostridium perfringens. J. Bacteriol. 181:7136-7139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gudelj, M., G. O. Fruhwirth, A. Paar, F. Lottspeich, K. H. Robra, A. Cavaco-Paulo, and G. M. Gubitz. 2001. A catalase-peroxidase from a newly isolated thermoalkaliphilic Bacillus sp. with potential for the treatment of textile bleaching effluents. Extremophiles 5:423-429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gupta, N., F. Bonomi, D. M. Kurtz, N. Ravi, D. L. Wang, and B. H. Huynh. 1995. Recombinant Desulfovibrio vulgaris rubrerythrin-isolation and characterization of the diiron domain. Biochemistry 34:3310-3318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heinonen, J. K., and R. J. Lahti. 1981. A new and convenient colorimetric determination of inorganic ortho-phosphate and its application to the assay of inorganic pyrophosphatase. Anal. Biochem. 113:313-317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. http://www.secsg.org.

- 21. http://www.tigr.org.

- 22.Jenney, F. E., and M. W. W. Adams. 2001. Rubredoxin from Pyrococcus furiosus. Methods Enzymol. 334:45-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jenney, F. E., M. F. J. M. Verhagen, X. Y. Cui, and M. W. W. Adams. 1999. Anaerobic microbes: Oxygen detoxification without superoxide dismutase. Science 286:306-309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kawasaki, S., J. Ishikasa, Y. Watamusa, and Y. Niimura. 2004. Identification of O2-induced peptides in an obligatory anaerobe, Clostridium acetobutylicum. FEBS Lett. 571:21-25. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Kengen, S. W., F. J. Bikker, W. R. Hagen, W. M. de Vos, and J. Van Der Oost. 2001. Characterization of a catalase-peroxidase from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Archaeoglobus fulgidus. Extremophiles 5:323-332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kumar, S., K. Tamura, and M. Nei. 2004. MEGA3: Integrated software for molecular evolutionary genetics analysis and sequence alignment. Briefings Bioinformatics 5:150-163. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Legall, J., B. C. Prickril, I. Moura, A. V. Xavier, J. J. G. Moura, and B. H. Huynh. 1988. Isolation and characterization of rubrerythrin, a non-heme iron protein from Desulfovibrio vulgaris that contains rubredoxin centers and a hemerythrin-like binuclear iron cluster. Biochemistry 27:1636-1642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lehmann, Y., L. Meile, and M. Teuber. 1996. Rubrerythrin from Clostridium perfringens: Cloning of the gene, purification of the protein, and characterization of its superoxide dismutase function. J. Bacteriol. 178:7152-7158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li, M., M. Y. Liu, J. Le Gall, L. L. Gui, J. Liao, T. Jiang, J. Zhang, D. Liang, and W. Chang. 2003. Crystal structure studies on rubrerythrin: Enzymatic activity in relation to the zinc movement. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 8:149-155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu, M. Y., and J. Legall. 1990. Purification and characterization of two proteins with inorganic pyrophosphatase activity from Desulfovibrio vulgaris-rubrerythrin and a new, highly-active, enzyme. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 171:313-318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lovenberg, W., J. C. Rabinowitz, and B. B. Buchanan. 1963. Studies on chemical nature of clostridial ferredoxin. J. Biol. Chem. 238:3899-3913. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ma, K., and M. W. W. Adams. 1999. A hyperactive NAD(P)H: rubredoxin oxidoreductase from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus furiosus. J. Bacteriol. 181:5530-5533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mccord, J. M., and I. Fridovic. 1969. Superoxide dismutase-an enzymic function for erythrocuprein. J. Biol. Chem. 244:6049-6055. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pierik, A. J., R. B. G. Wolbert, G. L. Portier, M. F. J. M. Verhagen, and W. R. Hagen. 1993. Nigerythrin and rubrerythrin from Desulfovibrio vulgaris each contain two mononuclear iron centers and two dinuclear iron clusters. Eur. J. Biochem. 212:237-245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ravi, N., B. C. Prickril, D. M. Kurtz, and B. H. Huynh. 1993. Spectroscopic characterization of Fe-57-reconstituted rubrerythrin, a nonheme iron protein with structural analogies to ribonucleotide reductase. Biochemistry 32:8487-8491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Robb, F. T., D. L. Maeder, J. R. Brown, J. DiRuggiero, M. D. Stump, R. K. Yeh, R. B. Weiss, and D. M. Dunn. 2001. Genomic sequence of hyperthermophile, Pyrococcus furiosus: Implications for physiology and enzymology. Methods Enzymol. 330:134-157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rzhetsky, A., and M. Nei. 1993. Theoretical foundation of the minimum-evolution method of phylogenetic inference. Mol. Biol. Evol. 10:1073-1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Saitou, N., and M. Nei. 1987. The neighbor-joining method-a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 4:406-425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sambrook, J., and D. Russell. 2001. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 3rd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 40.Schut, G. J., S. D. Brehm, S. Datta, and M. W. W. Adams. 2003. Whole-genome DNA microarray analysis of a hyperthermophile and an archaeon: Pyrococcus furiosus grown on carbohydrates or peptides. J. Bacteriol. 185:3935-3947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sieker, L. C., M. Holmes, I. Le Trong, S. Turley, M. Y. Liu, J. LeGall, and R. E. Stenkamp. 2000. The 1.9 angstrom crystal structure of the “as isolated” rubrerythrin from Desulfovibrio vulgaris: some surprising results. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 5:505-513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sieker, L. C., M. Holmes, I. Le Trong, S. Turley, B. D. Santarsiero, M. Y. Liu, J. LeGall, and R. E. Stenkamp. 1999. Alternative metal-binding sites in rubrerythrin. Nat. Struct. Biol. 6:308-309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sztukowska, M., M. Bugno, J. Potempa, J. Travis, and D. M. Kurtz. 2002. Role of rubrerythrin in the oxidative stress response of Porphyromonas gingivalis. Mol. Microbiol. 44:479-488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tempel, W., Z. J. Liu, F. D. Schubot, M. V. Weinberg, F. E. Jenney, Jr., M. W. W. Adams, J. P. Rose, and B. C. Wang. Structural genomics of Pyrococcus furiosus: X-ray crystallography reveals 3D domain swapping in rubrerythrin. Proteins Struct. Funct. Genet., in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 45.Thompson, V. S., K. D. Schaller, and W. A. Apel. 2003. Purification and characterization of a novel thermo-alkali-stable catalase from Thermus brockianus. Biotechnol. Prog. 19:1292-1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Van Beeumen, J. J., G. Van Driessche, M. Y. Liu, and J. LeGall. 1991. The primary structure of rubrerythrin, a protein with inorganic pyrophosphatase activity from Desulfovibrio vulgaris-comparison with hemerythrin and rubredoxin. J. Biol. Chem. 266:20645-20653. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wakagi, T. 2003. Sulerythrin, the smallest member of the rubrerythrin family, from the strictly aerobic and thermoacidophilic archaeon, Sulfolobus tokodaii strain 7. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 222:33-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]