Abstract

Lipoic acid is an essential prosthetic group in several metabolic pathways. The biosynthetic pathway of protein lipoylation in Escherichia coli involves gene products of the lip operon. YbeD is a conserved bacterial protein located in the dacA-lipB intergenic region. Here, we report the nuclear magnetic resonance structure of YbeD from E. coli. The structure includes a βαββαβ fold with two α-helices on one side of a four-strand antiparallel β-sheet. The β2-β3 loop shows the highest sequence conservation and is likely functionally important. The β-sheet surface contains a patch of conserved hydrophobic residues, suggesting a role in protein-protein interactions. YbeD shows striking structural homology to the regulatory domain from d-3-phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase, hinting at a role in the allosteric regulation of lipoic acid biosynthesis or the glycine cleavage system.

YbeD is a conserved protein in Escherichia coli located between the dacA gene, which encodes a d-alanyl-d-alanine carboxypeptidase involved in peptidoglycan biosynthesis, and the lip operon, which contains genes that are responsible for lipoic acid biosynthesis.

Lipoic acid (1,2-dithiolane-3-pentanoic acid) is a derivative of octanoic acid in which covalently linked sulfur atoms are at the C-6 and C-8 positions. It is an essential prosthetic group used in several metabolic pathways in most living organisms (26). Lipoic acid is covalently attached to the lipoyl domain of certain enzymes via an amide linkage between its carboxylic acid moiety and the ɛ-amino group of a specific lysine of the lipoylated protein. The added lengths of the reactive lipoate moiety and the lysine side chain create a swinging arm that helps to transfer reaction intermediates between catalytic sites of multienzyme complexes (26). The known E. coli enzymes that use lipoic acid as a prosthetic group include pyruvate and 2-oxoglutarate dehydrogenases (in glycolysis and the citric acid cycle), branched-chain keto acid dehydrogenases (in metabolism of valine, leucine, and isoleucine), and the glycine cleavage system (29, 33). All are involved in oxidative metabolism.

There are two complementary pathways of protein lipoylation in E. coli (9). The exogenous pathway utilizes extracellular lipoic acid scavenged from the environment. The enzyme lipoate-protein ligase (LplA) plays a key role in this pathway by using lipoic acid and ATP to lipoylate target proteins (22, 23). The endogenous, biosynthetic pathway is less understood and involves gene products of the lip locus of E. coli. Octanoic acid is a fatty acid precursor of lipoic acid, but its direct conversion to lipoic acid has not been observed (34, 35). Instead, the octanoyl moiety on acyl carrier protein of fatty acid synthesis (10) is converted to a lipoyl moiety by the enzyme lipoyl synthase (LipA) (20). This enzyme has 36% sequence identity to biotin synthase (BioB) and is expected to insert sulfur atoms by a similar mechanism (8, 29). The lipoyl moiety is then transferred from acyl carrier protein to the target enzyme by the lipoyl transferase LipB (11, 23).

In early work on the lip operon workers identified a lipolyated protein that belongs to the glycine cleavage system (33). The glycine cleavage system is thought to balance the cell's requirements for glycine and one-carbon units. It consists of four proteins, proteins H, P, T and L, which catalyze the oxidative cleavage of glycine to NH3, CO2, and a one-carbon methylene group (12, 18), which is used in synthesis of purines, histidine, methionine (17), and serine (28). The glycine cleavage system and lipoic acid biosynthesis pathways cross talk via LipB, which lipoylates protein H (4).

There are still unanswered questions concerning the catalytic mechanism of LipA and LipB in the endogenous lipoylation pathway and their enzymatic regulation. Some answers to these questions may come from studies of the two largely uncharacterized genes of the lip operon, ybeF and ybeD. Both gene products are conserved in bacterial species (32, 33). YbeF is putatively identified as a LysR-type transcriptional regulator, because its N-terminal part contains a characteristic DNA-binding helix-turn-helix motif. ybeD in the dacA-lipB intergenic region encodes a conserved 9.8-kDa protein which has no sequence homology to any known protein family and remains enigmatic.

Here, we solved the nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) structure of YbeD from E. coli and found that it has striking structural similarity to ACT domains, which are small-molecule binding domains often involved in allosteric regulation of amino acid and nucleoside metabolism.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Protein expression and purification.

YbeD was cloned into the NdeI and BamHI sites of a modified pET15b cloning vector (Novagen) containing a TEV protease cleavage site and a double stop codon downstream of the BamHI site. The N-terminally His6-tagged fusion protein was expressed in E. coli BL21-Gold(DE3) (Stratagene) and purified by immobilized metal affinity chromatography with an Ni2+-loaded chelating Sepharose column (Amersham Biosciences). The resulting protein contained the N-terminal His tag (MGTSHHHHHHSSGRENLYFQGH) in addition to YbeD residues 1 to 87 and was used in studies without cleavage. Isotopically enriched YbeD fusion protein was prepared from cells grown on minimal M9 media containing [15N]ammonium chloride with or without [6-13C]glucose (Cambridge Isotopes Laboratory, Andover, Mass.).

Gel filtration.

The oligomeric state of the YbeD fusion protein was determined by gel filtration. The column (HiLoad 16/60 Superdex 75; Pharmacia Biotech) was calibrated with bovine serum albumin (molecular mass, 66 kDa; Sigma), carbonic anhydrase from bovine erythrocytes (29 kDa; Sigma), cytochrome c from horse heart (12.4 kDa; Sigma), and aprotinin from bovine lung (6.5 kDa; Sigma). All samples were run at a flow rate of 1 ml/min and room temperature in 50 mM Tris-500 mM NaCl (pH 7.5). YbeD eluted from the column at a predicted molecular mass of ∼13 kDa, as expected for a monomer (molecular mass, 12.4 kDa).

NMR spectroscopy.

NMR samples at a protein concentration of 1 mM were exchanged into 50 mM phosphate buffer containing 0.3 M NaCl and 0.1 mM sodium azide at pH 6.3. NMR experiments were performed at 303 K. Backbone and side chain NMR signal assignments of the YbeD fusion protein were determined by performing HNCA, CBCA(CO)NH, N15-edited three-dimensional (3D) NOESY, N15-edited 3D TOCSY, and two-dimensional (2D) homonuclear NOESY experiments with a Bruker DRX500 MHz spectrometer. 3JHN-Hα coupling constants were obtained from an HNHA experiment (15). NMR spectra were processed by using GIFA (27) and XWINNMR (Bruker Biospin) software and were analyzed with XEASY (3).

Structure calculations.

NOE restraints were obtained from 15N-edited 3D NOESY and 2D homonuclear NOESY in D2O. The φ and ψ torsion angles were derived from 3JHN-Hα coupling constants and Cα, Cβ, and Hα chemical shifts by using TALOS (5). Structures were calculated by using the CANDID module implemented in the program Cyana (7). 2D NOESY and 3D 15N-NOESY spectra were used in the CANDID protocol to calibrate and assign NOE cross-peaks. The 20 lowest-energy structures obtained after seven cycles of calculations in Cyana were refined further by using standard protocols in Xplor-NIH (31), with the 15 lowest-energy structures comprising the final ensemble. On average, 6.9 constraints per residue in the YbeD structured region (Phe11 to Leu87) were used to calculate the YbeD structure. This relatively low number resulted from the tendency of the YbeD fusion protein to aggregate, which limited the protein concentration in NMR samples and the sensitivity of NOESY experiments. The YbeD aggregation properties were concentration dependent. The quality of the final structures was assessed by using PROCHECK (16). The structural statistics are shown in Table 1. Coordinates have been deposited in the PDB data bank (http://www.rcsb.org/pdb/; PDB ID code 1RWU), and chemical shift assignments have been deposited under BMRB accession number 6102 (http://www.bmrb.wisc.edu/).

TABLE 1.

Structural statistics for YbeD

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Restraints for structure calculations | |

| Total no. of restraints used | 556 |

| Total no. of NOE restraints | 393 |

| No. of intraresidual restraints | 139 |

| No. of sequential (|i−j| = 1) restraints | 120 |

| No. of medium-range (1 < |i−j| < 5) restraints | 44 |

| No. of long-range (|i−j| ≥ 5) restraints | 90 |

| No. of hydrogen bond restraints | 32 |

| No. of dihedral angle restraints | 131 |

| Root mean square deviations from experimental restraints | |

| Distance deviations (Å) | 0.018 ± 0.0011 |

| Dihedral deviations (°) | 0.349 ± 0.0716 |

| Deviations from idealized geometry | |

| Bonds (Å) | 0.0036 ± 0.0001 |

| Angles (°) | 0.5733 ± 0.0051 |

| Impropers (°) | 0.3849 ± 0.0096 |

| Root mean square deviations of the 15 structures from the mean coordinates (Å) | |

| Backbone (residues Phe11 to Leu87) | 0.54 ± 0.14 |

| Heavy atoms (residues Phe11 to Leu87) | 1.11 ± 0.20 |

| Ramachandran plot statistics for residues Phe11 to Leu87 (%) | |

| Residues in most favored regions | 88.0 |

| Residues in additional allowed regions | 11.6 |

| Residues in generously allowed regions | 0.4 |

| Residues in disallowed regions | 0.0 |

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

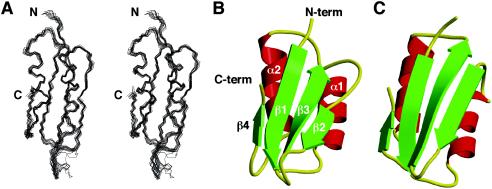

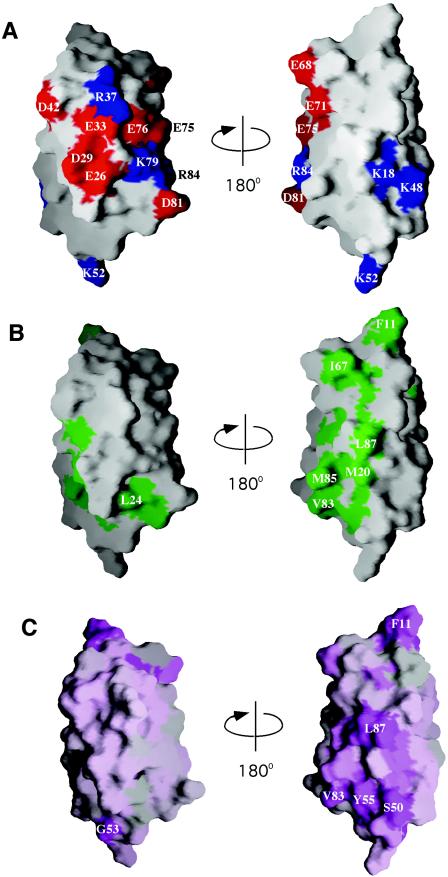

The structure of YbeD (Fig. 1) includes a four-strand antiparallel β-sheet and two parallel α-helices on one side. The hydrophobic core is formed by Phe15, Tyr17, Val19, Leu27, Val28, Val31, Val32, Val34, Val35, Pro45, Val47, Val58, Ile60, Ile62, Val70, Leu73, Tyr74, and Val86. The surface charge distribution identifies two distinct regions (Fig. 2A). The α-helical side of the protein is highly charged with a distinct negative patch formed by Glu26, Asp29, Glu33, and Glu76. In contrast, the opposite β-sheet surface is largely uncharged and contains a cluster of exposed hydrophobic amino acids (Met20, Val83, Met85, and Leu87) (Fig. 2B). YbeD residues 1 to 9 did not show any long-range NOEs with other parts of the protein and appear to be mobile.

FIG. 1.

Structure of YbeD. (A) Stereo view of the backbone superposition of the 15 lowest-energy structures generated with MOLMOL (13). The superposition was done by using residues Phe11 to Leu87. (B) Ribbon representation of the YbeD structure generated with MOLSCRIPT (14) and Raster3D (19). The N terminus (N-term), C terminus (C-term), and secondary-structure elements are indicated. (C) The structure of the ACT domain of d-3-phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase (PDB code 1PSD) is very similar to that of YbeD, as backbone superposition of 48 residues resulted in 1.9-Å root-mean-square deviation.

FIG. 2.

Surface distribution of charged (A), hydrophobic (B), and conserved (C) residues on two distinct faces of YbeD. While the α-helical surface is enriched with charged residues, the β-sheet side is mostly hydrophobic and may mediate protein-protein interactions. Positively charged residues are blue, negatively charged residues are red, hydrophobic residues are green, and conserved residues are purple. The view on the right is identical to that in Fig. 1. The figure was generated with GRASP (24).

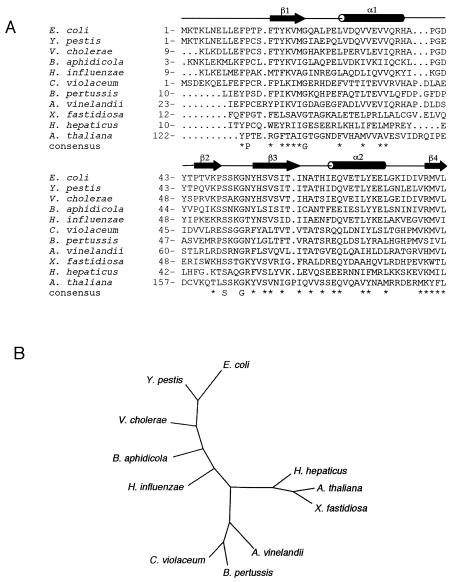

A sequence alignment for the YbeD family was used to identify functionally important residues (Fig. 3A). While the most conserved residues within the secondary structure regions play a structural role as part of the hydrophobic core, conservation of the exposed hydrophobic residues on the β-sheet surface suggests functional importance. Interestingly, the loop between the β2 and β3 strands is one of the most conserved regions of YbeD (Fig. 2C) and includes an invariant serine residue and almost invariant glycine. In addition to bacteria, a YbeD-like sequence is present in the C-terminal domain of a conserved plant protein found in Arabidopsis thaliana (gi: 18396311) and Oryza sativa (gi: 38347226). Unfortunately, the protein does not exhibit any significant sequence identity to known proteins and thus does not help identify the function of its YbeD-like C-terminal domain.

FIG. 3.

Sequence conservation in the YbeD protein family. (A) YbeD sequence from E. coli K-12 aligned with the sequences of homologous proteins from Yersinia pestis (gi: 16122813), Vibrio cholerae (gi: 15640961), Buchnera aphidicola strain Bp (gi: 27904910), Haemophilus influenzae Rd (gi: 16272003), Chromobacterium violaceum (gi: 34104405), Bordetella pertussis (gi: 33591363), Azotobacter vinelandii (gi: 23106484), Xylella fastidiosa Dixon (gi: 22994244), Helicobacter hepaticus ATCC 51449 (gi: 32266384), and Arabidopsis thaliana (gi: 18396311). The secondary-structure elements refer to YbeD from E. coli. (B) Phylogenetic tree for the aligned sequences generated with DIALIGN (21) and TreeView (25).

A structural homology search with YbeD by using the DALI server (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/dali) resulted in multiple hits corresponding to a wide variety of domains with RNA-binding, enzymatic, and regulatory functions. This reflects an ancient origin and the intrinsic stability of the βαββαβ fold, which is utilized in various contexts and activities. We can confidently exclude the possibility that YbeD is an RNA-binding protein, since it does not contain RNA recognition motifs and the patches of positively charged and aromatic residues that are characteristic of oligonucleotide-binding domains. Among all the DALI hits, the regulatory domain from d-3-phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase (SerA) showed the highest Z-score, 6.1 (Fig. 1C). This domain belongs to a class of small-molecule-binding modules termed ACT (aspartokinase, chorismate mutase, and TyrA) (2) domains. These domains are often involved in allosteric regulation (negative feedback) of amino acids and nucleoside metabolism. They usually occur in multidomain enzymes or transcription factors and also as stand-alone modules. In particular, SerA catalyzes the first step in serine biosynthesis and contains catalytic and regulatory domains connected via a flexible hinge region (30). When the serine effector molecule binds the YbeD-like regulatory domain, an interdomain rearrangement causes down-regulation of catalytic activity (6). The ACT domains bind ligands on the homodimeric interface of the β1-α1 loop (1, 6), which is reflected in the significant sequence conservation in this loop. YbeD shows highest sequence conservation in the β2-β3 loop, which makes this loop the most likely binding site for any potential effector. This loop is not well structured, as indicated by weak or missing NMR signals, but it may adopt a more rigid conformation upon substrate binding.

Gene organization in E. coli is characterized by the clustering of genes involved in specific pathways. Based on this, YbeD function is likely to be coupled with the function of proteins from the lip locus and, in particular, with LipB function. This suggests two main possibilities for YbeD function. One is allosteric regulation of lipoic acid biosynthesis. In this scenario, YbeD might bind lipoic acid and down-regulate intracellular lipoic acid biosynthesis. An E. coli strain with a transposon insertion mutation in ybeD did not require a lipoic acid supplement for normal growth (33), but this does not rule out a possible role for YbeD as a negative regulator. Another plausible function of YbeD is in negative regulation of the glycine cleavage system via suppression of protein H lipoylation by LipB. In either case, YbeD would have to interact with a targeted enzyme or DNA-binding domain, and the conserved hydrophobic patch on the β-sheet surface is a possible protein-protein interaction site.

Structural proteomics is developing into a powerful tool for identification of the functions of previously unknown proteins. In the case of YbeD, the striking structural similarity to the regulatory domain of SerA suggests that YbeD is a regulatory protein. The structure opens new perspectives for further studies on YbeD and proteins encoded by the lip operon.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by Canadian Institutes for Health Research genomics grant GSP-48370 (to M.C. and K.G.), by the Ontario Research and Development Challenge Fund, and by Genome Canada (C. H. Arrowsmith and A. M. Edwards). K.G. is a Chercheur National of the Fonds de la recherche en santé Québec.

REFERENCES

- 1.Al-Rabiee, R., Y. Zhang, and G. A. Grant. 1996. The mechanism of velocity modulated allosteric regulation in d-3-phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase. Site-directed mutagenesis of effector binding site residues. J. Biol. Chem. 271:23235-23238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aravind, L., and E. V. Koonin. 1999. Gleaning non-trivial structural, functional and evolutionary information about proteins by iterative database searches. J. Mol. Biol. 287:1023-1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bartels, C., T.-H. Xia, M. Billeter, P. Guntert, and K. Wuthrich. 1995. The program XEASY for computer-supported NMR spectral analysis of biological macromolecules. J. Biomol. NMR 5:1-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen, X. J. 1997. Cloning and characterization of the lipoyl-protein ligase gene lipB from the yeast Kluyveromyces lactis: synergistic respiratory deficiency due to mutations in lipB and mitochondrial F1-ATPase subunits. Mol. Gen. Genet. 255:341-349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cornilescu, G., F. Delaglio, and A. Bax. 1999. Protein backbone angle restraints from searching a database for chemical shift and sequence homology. J. Biomol. NMR 13:289-302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grant, G. A., D. J. Schuller, and L. J. Banaszak. 1996. A model for the regulation of d-3-phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase, a Vmax-type allosteric enzyme. Protein Sci. 5:34-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guntert, P., C. Mumenthaler, and K. Wuthrich. 1997. Torsion angle dynamics for NMR structure calculation with the new program DYANA. J. Mol. Biol. 273:283-298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hayden, M. A., I. Huang, D. E. Bussiere, and G. W. Ashley. 1992. The biosynthesis of lipoic acid. Cloning of lip, a lipoate biosynthetic locus of Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 267:9512-9515. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Herbert, A. A., and J. R. Guest. 1968. Biochemical and genetic studies with lysine+methionine mutants of Escherichia coli: lipoic acid and alpha-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase-less mutants. J. Gen. Microbiol. 53:363-381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jordan, S. W., and J. E. Cronan, Jr. 1997. A new metabolic link. The acyl carrier protein of lipid synthesis donates lipoic acid to the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex in Escherichia coli and mitochondria. J. Biol. Chem. 272:17903-17906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jordan, S. W., and J. E. Cronan, Jr. 2003. The Escherichia coli lipB gene encodes lipoyl (octanoyl)-acyl carrier protein:protein transferase. J. Bacteriol. 185:1582-1589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kikuchi, G. 1973. The glycine cleavage system: composition, reaction mechanism, and physiological significance. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 1:169-187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koradi, R., M. Billeter, and K. Wuthrich. 1996. MOLMOL: a program for display and analysis of macromolecular structures. J. Mol. Graph. 14:51-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kraulis, P. J. 1991. MOLSCRIPT: a program to produce both detailed and schematic plots of protein structures. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 24:946-950. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kuboniwa, H., S. Grzesiek, F. Delaglio, and A. Bax. 1994. Measurement of HN-H alpha J couplings in calcium-free calmodulin using new 2D and 3D water-flip-back methods. J. Biomol. NMR 4:871-878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Laskowski, R. A., J. A. Rullmannn, M. W. MacArthur, R. Kaptein, and J. M. Thornton. 1996. AQUA and PROCHECK-NMR: programs for checking the quality of protein structures solved by NMR. J. Biomol. NMR 8:477-486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Matthews, R. G. 1996. One-carbon metabolism, p. 600-611. In F. C. Niedhardt, R. Curtiss III, J. L. Ingraham, E. C. C. Lin, K. B. Low, B. Magasanik, W. S. Reznikoff, M. Riley, M. Schaechter, and H. E. Umbarger (ed.), Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology, 2nd ed. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 18.Meedel, T. H., and L. I. Pizer. 1974. Regulation of one-carbon biosynthesis and utilization in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 118:905-910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Merritt, E. A., and M. E. P. Murphy. 1994. Raster3D version 2.0: a program for photorealistic molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D 50:869-873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miller, J. R., R. W. Busby, S. W. Jordan, J. Cheek, T. F. Henshaw, G. Ashley, J. B. Broderick, J. E. Cronan, Jr., and M. A. Marletta. 2000. Escherichia coli LipA is a lipoyl synthase: in vitro biosynthesis of lipoylated pyruvate dehydrogenase complex from octanoyl-acyl carrier protein. Biochemistry 39:15166-15178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morgenstern, B., K. Frech, A. Dress, and T. Werner. 1998. DIALIGN: finding local similarities by multiple sequence alignment. Bioinformatics 14:290-294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morris, T. W., K. E. Reed, and J. E. Cronan, Jr. 1994. Identification of the gene encoding lipoate-protein ligase A of Escherichia coli. Molecular cloning and characterization of the lplA gene and gene product. J. Biol. Chem. 269:16091-16100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morris, T. W., K. E. Reed, and J. E. Cronan, Jr. 1995. Lipoic acid metabolism in Escherichia coli: the lplA and lipB genes define redundant pathways for ligation of lipoyl groups to apoprotein. J. Bacteriol. 177:1-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nicholls, A., K. A. Sharp, and B. Honig. 1991. Protein folding and association: insights from the interfacial and thermodynamic properties of hydrocarbons. Proteins 11:281-296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Page, R. D. 1996. TreeView: an application to display phylogenetic trees on personal computers. Comput. Appl. Biosci. 12:357-358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Perham, R. N. 2000. Swinging arms and swinging domains in multifunctional enzymes: catalytic machines for multistep reactions. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 69:961-1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pons, J. L., T. E. Malliavin, and M. A. Delsuc. 1997. Gifa V. 4: a complete package for NMR data set processing. J. Biomol. NMR 8:445-452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ravnikar, P. D., and R. L. Somerville. 1987. Genetic characterization of a highly efficient alternate pathway of serine biosynthesis in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 169:2611-2617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reed, K. E., and J. E. Cronan, Jr. 1993. Lipoic acid metabolism in Escherichia coli: sequencing and functional characterization of the lipA and lipB genes. J. Bacteriol. 175:1325-1336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schuller, D. J., G. A. Grant, and L. J. Banaszak. 1995. The allosteric ligand site in the Vmax-type cooperative enzyme phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2:69-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schwieters, C. D., J. J. Kuszewski, N. Tjandra, and G. M. Clore. 2003. The Xplor-NIH NMR molecular structure determination package. J. Magn. Res. 160:66-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Takase, I., F. Ishino, M. Wachi, H. Kamata, M. Doi, S. Asoh, H. Matsuzawa, T. Ohta, and M. Matsuhashi. 1987. Genes encoding two lipoproteins in the leuS-dacA region of the Escherichia coli chromosome. J. Bacteriol. 169:5692-5699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vanden Boom, T. J., K. E. Reed, and J. E. Cronan, Jr. 1991. Lipoic acid metabolism in Escherichia coli: isolation of null mutants defective in lipoic acid biosynthesis, molecular cloning and characterization of the E. coli lip locus, and identification of the lipoylated protein of the glycine cleavage system. J. Bacteriol. 173:6411-6420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.White, R. H. 1980. Biosynthesis of lipoic acid: extent of incorporation of deuterated hydroxy- and thiooctanoic acids into lipoic acid. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 102:6605-6607. [Google Scholar]

- 35.White, R. H. 1980. Stoichiometry and stereochemistry of deuterium incorporated into fatty acids by cells of Escherichia coli grown on [methyl-2H3]acetate. Biochemistry 19:9-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]