Abstract

Eukaryotic vacuolar H+-ATPase (V-ATPase) is a multisubunit enzyme complex that acidifies subcellular organelles and the extracellular space. V-ATPase consists of soluble V1-ATPase and membrane-integral Vo proton channel sectors. To investigate the mechanism of V-ATPase regulation by reversible disassembly, we recently determined a cryo-EM reconstruction of yeast Vo. The structure indicated that, when V1 is released from Vo, the N-terminal cytoplasmic domain of subunit a (aNT) changes conformation to bind rotor subunit d. However, insufficient resolution precluded a precise definition of the aNT-d interface. Here we reconstituted Vo into lipid nanodiscs for single-particle EM. 3D reconstructions calculated at ∼15-Å resolution revealed two sites of contact between aNT and d that are mediated by highly conserved charged residues. Alanine mutagenesis of some of these residues disrupted the aNT-d interaction, as shown by isothermal titration calorimetry and gel filtration of recombinant subunits. A recent cryo-EM study of holo V-ATPase revealed three major conformations corresponding to three rotational states of the central rotor of the enzyme. Comparison of the three V-ATPase conformations with the structure of nanodisc-bound Vo revealed that Vo is halted in rotational state 3. Combined with our prior work that showed autoinhibited V1-ATPase to be arrested in state 2, we propose a model in which the conformational mismatch between free V1 and Vo functions to prevent unintended reassembly of holo V-ATPase when activity is not needed.

Keywords: EM, isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC), protein structure, proton transport, vacuolar ATPase, Vo proton channel, lipid nanodisc

Introduction

The vacuolar H+-ATPase (V-ATPase,2 V1Vo-ATPase) is a large multisubunit enzyme complex found in the endomembrane system of all eukaryotic cells, where it acidifies the lumen of subcellular organelles, including lysosomes, endosomes, the Golgi apparatus, and clathrin-coated vesicles (1–4). V-ATPase function is essential for pH and ion homeostasis (2), protein trafficking, endocytosis, mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) (5, 6), and Notch (7) signaling as well as hormone secretion (8) and neurotransmitter release (9). In animals, V-ATPase can also be found in the plasma membrane of polarized cells, where its proton pumping function is involved in bone remodeling, urine acidification, and sperm maturation (1). The essential nature of eukaryotic V-ATPase is highlighted by the fact that complete loss of V-ATPase activity in animals is embryonic lethal (10). On the other hand, partial loss of enzyme function (or hyperactivity) has been associated with numerous widespread human diseases, including, but not limited to, renal tubular acidosis (11), osteoporosis (12), neurodegeneration (13), male infertility (14), deafness (15), diabetes (8), and cancer (16). Furthermore, V-ATPase is targeted by pathogens such as Mycobacterium tuberculosis or Legionella pneumophila (17, 18) to facilitate pathogen entry and survival. Because of its essential nature and key role in so many human diseases, V-ATPase has been identified as a potential drug target (19–21).

V-ATPase can be divided into a soluble catalytic sector, V1, and a membrane-integral proton channel sector, Vo (Fig. 1). In the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, V1 is composed of eight different polypeptides, AB(C)DEFGH, that are arranged in an A3B3 catalytic hexamer with a central stalk made of DF and three peripheral stators (EG heterodimers), one of which binds the single-copy H subunit. The ∼320-kDa Vo contains subunits acc'c”de, which are organized in a membrane-integral “proteolipid” ring (c8c'c” (22, 23)), a membrane-bound subunit a with an integral C-terminal domain (aCT) that is bound at the periphery of the proteolipid ring, and an N-terminal cytoplasmic domain (aNT) that is bound to subunit d (Fig. 1). The stoichiometry, location, and function of subunit e are not known. Eukaryotic V-ATPase belongs to the family of energy-transducing rotary motor ion pumps that also includes F1Fo-ATP synthase, archaeal A-ATPase, and bacterial A/V-like ATPase (24, 25). In V-ATPase, ATP hydrolysis at three catalytic sites in the A3B3 hexamer is coupled to proton translocation via rotation of V1 subunits DF that are connected to the subunit d-proteolipid ring subcomplex of Vo. Proton translocation is through two aqueous half-channels at the interface of aCT and the proteolipid ring and involves membrane-embedded essential glutamate and arginine residues in the c subunits and aCT, respectively.

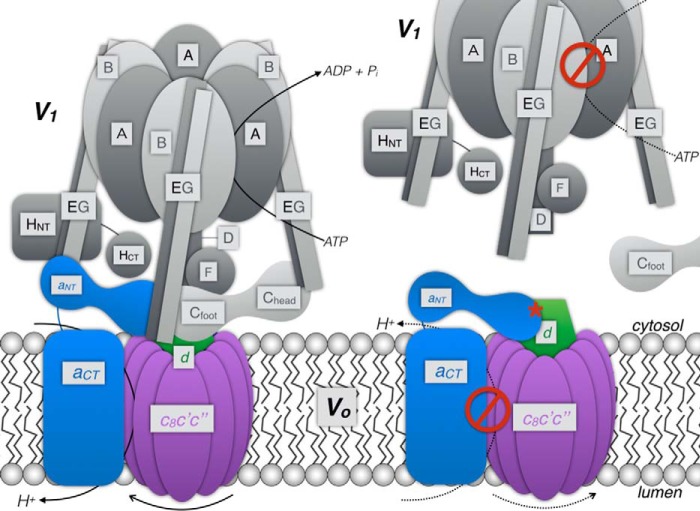

FIGURE 1.

Schematic of V-ATPase architecture and the mechanism of regulation by reversible disassembly. V1 is represented by subunits shaded in gray. Subunits of Vo are shown in blue (a), purple (c-ring composed of c8c'c″), and green (d). ATP hydrolysis in V1 drives rotation of the c-ring, resulting in proton translocation across the interface of the c-ring and aCT. Upon reversible disassembly, subunit C is released into the cytoplasm, and the interactions between subunits of V1 (DF and EG1–3) and Vo (aNT, d) are broken. Disassembly of the enzyme results in a V1 that does not hydrolyze MgATP and a Vo that does not support passive proton translocation. Note that, upon release of V1 from the membrane, aNT changes conformation to bind the central rotor subunit d (red asterisk) as reported previously (38).

V-ATPase function is regulated in vivo by a unique mechanism referred to as reversible disassembly, a condition under which the enzyme dissociates into membrane-bound Vo and cytoplasmic V1 sectors (26, 27) (Fig. 1). Reversible dissociation of V-ATPase is well characterized in the model organism S. cerevisiae (28), but more recent data suggest that the mammalian enzyme is regulated by a similar process in some cell types (5, 29–31). Although the assembly status of yeast V-ATPase is mainly governed by nutrient availability (32), the situation in mammalian cells appears to be more complex. Besides glucose levels (30), V-ATPase assembly in animal cells can be induced by a variety of signals, including cell maturation (33) and stimulation by hormones (34) and growth factors (6). Upon enzyme dissociation, the activity of both sectors is silenced; that is, the V1 no longer hydrolyzes MgATP (35, 36), and the Vo no longer translocates protons (37, 38). Although studies in yeast suggest that V1 activity silencing depends on the C-terminal domain of subunit H, possibly together with inhibitory MgADP (35, 39, 40), the mechanism by which passive proton transport across Vo is blocked is less well understood.

The structure of eukaryotic V-ATPase has been analyzed by EM, and together with crystal structures of individual subunits and subcomplexes from yeast V-ATPase and related bacterial enzymes, the EM reconstructions have allowed generation of pseudoatomic models of the intact enzyme (22, 41, 42) and its functional V1 (43) and Vo (38, 44) sectors. Although the resulting structural models together with biochemical data provide valuable information on the mechanism of ATP hydrolysis-driven proton pumping, we only have a limited understanding of the mechanism of reversible enzyme dissociation and reassociation. We recently obtained a cryo-EM reconstruction of yeast Vo (38), and although a comparison with EM models of holo V-ATPase showed that aNT undergoes a large structural change to bind the rotor subunit d in free Vo, the resolution of the model was insufficient to precisely define the aNT-d interface.

Here we present a negative-stain 3D EM reconstruction of lipid nanodisc-reconstituted Vo calculated at a resolution of ∼15 Å. The model of nanodisc-bound Vo suggests that the interaction between aNT and subunit d is mediated by charge complementation between acidic and basic residues on d and aNT, respectively. Site-directed mutagenesis and isothermal titration calorimetry experiments conducted with recombinant subunits identified acidic and basic patches on d and aNT that mediate the aNT-d interaction. A comparison with the recent EM reconstructions of yeast V-ATPase in three states (22) suggests that, upon enzyme dissociation, free Vo is halted in state 3. We showed previously that autoinhibited, membrane-detached V1-ATPase is halted in state 2 (45), and we propose that this conformational mismatch to state 3 Vo could function to prevent unintended reassembly of holo V-ATPase under conditions when the proton pumping activity of the enzyme is not needed.

Results

Purification of Vo Membrane Sector and Reconstitution into Lipid Nanodiscs

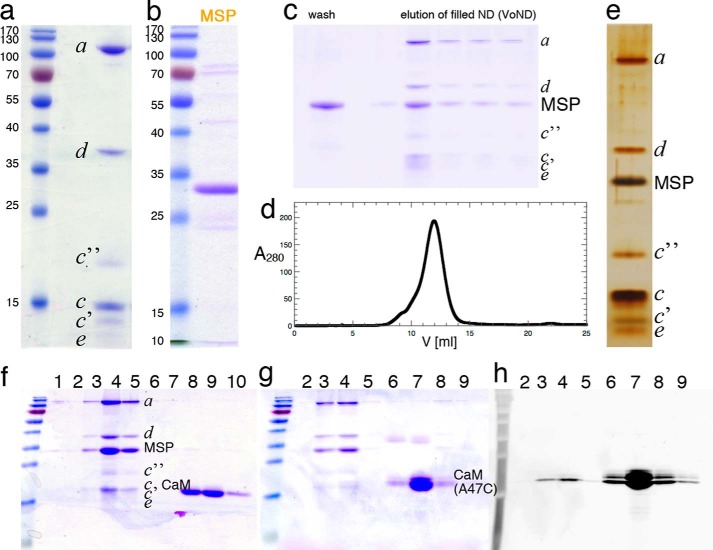

We previously developed a procedure for purification of milligram amounts of yeast V-ATPase Vo sector for functional and structural studies (38). Briefly, Vo was solubilized from vacuolar membranes and affinity-captured via a calmodulin binding peptide fused to the C terminus of the vacuole-specific isoform of subunit a (Vph1p). For structural studies under more native-like conditions, Vo was reconstituted into lipid nanodiscs as described under “Experimental Procedures” (Fig. 2). Purified detergent-solubilized Vo (Fig. 2a) was mixed with Escherichia coli polar lipids and the recombinant membrane scaffold protein MSP1E3D1 (Fig. 2b), followed by detergent removal with polystyrene beads. In a final purification step, Vo-containing nanodiscs (VoND) were separated from “empty” discs by a second calmodulin affinity binding step followed by size exclusion chromatography on a Superdex S200 column (Fig. 2, c and d). Peak fractions of VoND eluted from the gel filtration column were pooled, and the concentrated preparation was analyzed by SDS-PAGE and silver staining (Fig. 2e).

FIGURE 2.

Purification of Vo and reconstitution into lipid nanodiscs. a, SDS-PAGE of yeast Vo affinity-purified from solubilized yeast microsomal membranes via a calmodulin binding peptide fused to the C terminus of subunit a. b, SDS-PAGE of the membrane scaffold protein MSP1E3D1, purified by affinity chromatography via an N-terminal His6 tag. c, SDS-PAGE of flow-through and elution fractions from the calmodulin column after nanodisc reconstitution to remove unfilled discs. Reconstitution of the Vo into lipid nanodiscs is accomplished by mixing Vo, MSP, and lipid. Upon removal of detergent, Vo self-assembles into a nanodisc bilayer patch. d, size exclusion chromatography of VoND after removal of unfilled discs. e, SDS-PAGE of the final preparation after gel filtration. f, glycerol gradient of VoND-CaM. VoND was mixed with a 5-fold excess of calmodulin, and the mixture was applied to a discontinuous 15–35% glycerol gradient and centrifuged at 200,000 × g for 16 h at 4 °C. Fractions were collected from the bottom of the gradient and analyzed by SDS-PAGE. Peak fractions (4, 5) were pooled and used for negative stain electron microscopy. g and h, to verify binding of calmodulin to VoND, calmodulin (A47C) was labeled with fluorescein maleimide and the mixture of VoND, and labeled calmodulin was subjected to glycerol density centrifugation as in f. h, the fluorescence scan of the gel shown in g indicates co-migration of labeled calmodulin with VoND. The gels in a–c, f, and g were stained with Coomassie blue; the gel in e was stained with silver.

3D EM Reconstruction of VoND

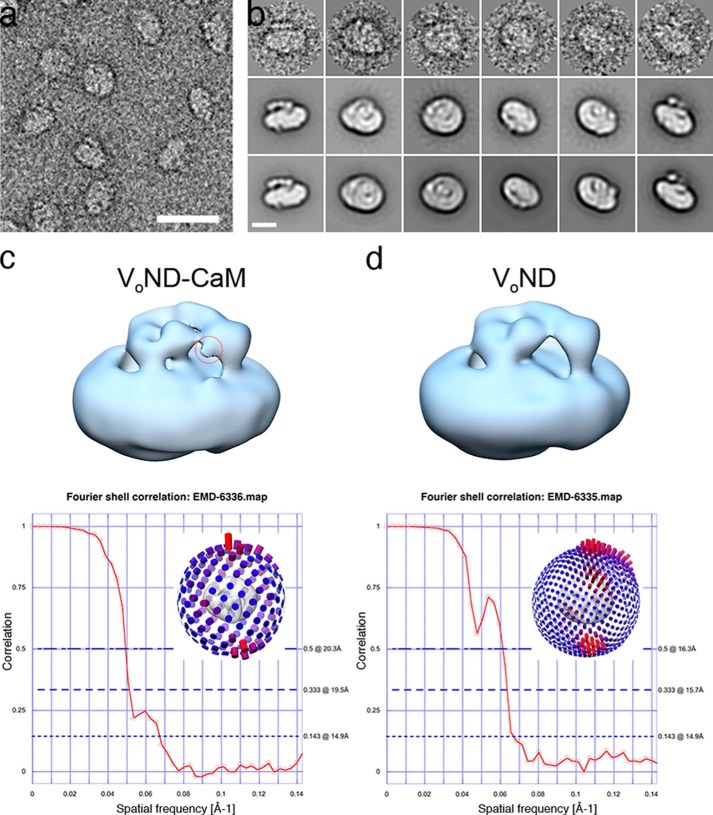

We initially generated a dataset of ∼30,000 particles from EM images of negatively stained VoND. However, attempts to reconstruct a 3D model of the complex using reference-free algorithms were unsuccessful, likely because of the limited size of the complex and the lack of characteristic features required for alignment. Models did not converge on a specific handedness, i.e. orientation of aNT with respect to the membrane sector, and density for aNT was smeared out over the membrane and did not allow us to distinguish its positioning relative to subunit d. We therefore decided to make use of the calmodulin binding peptide on the C terminus of subunit a to introduce an additional asymmetry to aid in alignments and angle determination in the 3D startup procedure. Purified calmodulin (CaM) was incubated with VoND, followed by removal of excess CaM using glycerol gradient centrifugation (Fig. 2, f–h). Negative stain electron microscopy showed that the final VoND-CaM preparation was monodisperse, with an average diameter of the particles of ∼12 nm (Fig. 3a). A dataset of ∼40,000 particles, generated from 380 micrographs such as shown in Fig. 3a, was subjected to reference-free alignment procedures as implemented in EMAN2. Fig. 3b shows class averages of side, top, and intermediate view projections (center row), representative raw particle images (top row), and the corresponding reprojections of the final 3D model (bottom row). Class averages, including those shown in Fig. 3b, were used for a 3D startup procedure in EMAN2, and the resulting 3D reconstruction was refined until stable. At this point, the reconstruction was strongly low pass-filtered and used as input for the 3D autorefinement procedure as implemented in the Relion 1.3 software package. The model was then refined until no further improvement was observed. The resolution of the final VoND-CaM 3D reconstruction was estimated to be 14.9 Å (20.3 Å at 0.5 correlation) using the “gold standard” FSC protocol as implemented in Relion 1.3 (Fig. 3c).

FIGURE 3.

Negative stain transmission electron microscopy of VoND-CaM. a, the representative micrograph reveals a monodisperse sample of ∼12-nm particles. b, class averages obtained by reference-free alignment of a dataset of ∼40,000 VoND-CaM projections (center row) with corresponding raw particle images (top row) and reprojections of the final VoND-CaM reconstruction (bottom row). c and d, final 3D reconstructions of VoND-CaM (c) and VoND (d) with corresponding gold standard FSC graphs shown below the models. The red circle on the VoND-CaM reconstruction indicates the density for calmodulin bound to the C terminus of subunit a. Insets in the FSC graphs illustrate the angular distributions of the particle orientations of the two datasets. Scale bars = 20 nm (a) and 10 nm (b).

The final VoND-CaM model was strongly low pass-filtered to serve as a reference for a new VoND dataset (∼47,000 images) using the Relion 3D autorefinement procedure as described for the VoND-CaM dataset. The 3D autorefinement converged to a final model of VoND with an estimated gold standard resolution of ∼14.9 Å (16.3 Å at 0.5 correlation, Fig. 3d). As can be seen from Fig. 3, c and d, the final VoND-CaM and VoND models are very similar except for a small density in the VoND-CaM map that is due to the CaM bound at the a subunit C terminus (Fig. 3c, top panel, red circle). However, because the VoND-CaM map showed slightly more detail, we used this model to illustrate the features of nanodisc-bound Vo as summarized in Fig. 4.

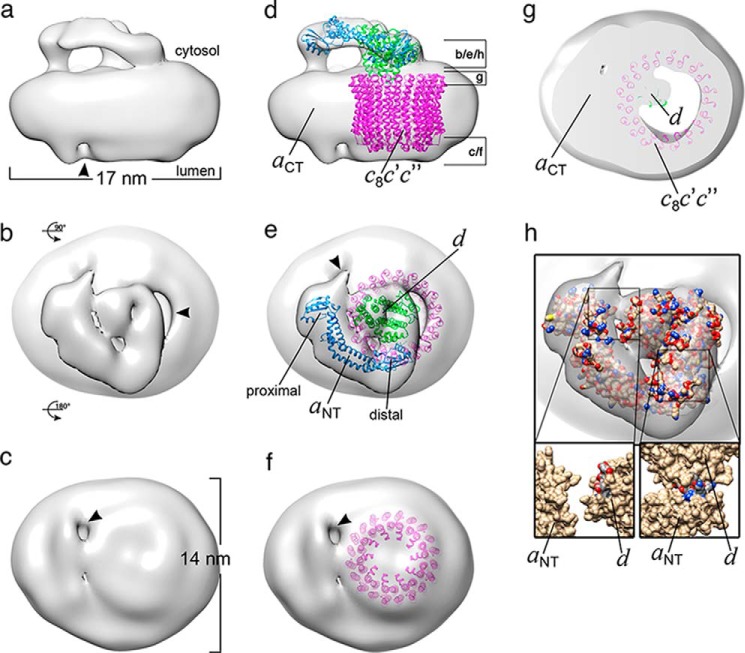

FIGURE 4.

3D reconstruction of VoND-CaM. a–c, side (a), top (b), and bottom (b) views of the 3D model of VoND-CaM. The membrane sector is ∼17 × 14 nm (a and c) with density on the cytosolic side above the membrane (aNT and subunit d) and a cleft on the lumenal side (arrowhead in a). d–f, fit of homology models of Vo subunits into the EM density: aNT (threaded into the crystal structure of M. ruber INT, PDB code 3RRK) in cyan, subunit d (threaded into the crystal structure of T. thermophilus C, PDB code 1V9M) in green, and E. hirae K10 (PDB code 2BL2) in magenta. g, cross-section as indicated in d, showing that the density representing the N-terminal α helix of subunit d contacts only one side of the c-ring as seen in state 3 of holo V1Vo (22). h, top view of VoND-CaM fitted with atomic models to indicate the sites of contact between aNT and subunit d. Note that, because of its pseudo-3-fold symmetry, the homology model of subunit d could be placed into the EM density in three orientations corresponding to the orientations as described for states 1–3 (22), with orientations 2 and 3 resulting in much better model-map correlations compared with orientation 1. The model (Phyre model of yeast “d”) to map (VoND-CaM; EMD-6336) correlations for the three orientations were 0.081 for state 3, 0.085 for state 2, and 0.076 for state 1, with 404, 296, and 323 amino acids outside of the model at a contour level of 0.022 for states 1–3, respectively.

Side, top, and bottom views of the VoND-CaM model are illustrated in Fig. 4, a–c, showing the characteristic features as seen in earlier reconstructions of bovine (44) and yeast (38) Vo, including the densities above the membrane (aNT and subunit d), the cleft between the density for aCT and the c-ring (Fig. 4a, arrowhead), which opens into a solvent (stain)-accessible pore as seen in the bottom view (Fig. 4c, arrowhead), and the large cavity on the cytoplasmic side of the c-ring (Fig. 4b, arrowhead). Semiautomatic fitting of homology models of the yeast Vo subunits into the EM density is summarized in Fig. 4, d–f. As illustrated in Fig. 4, d and e, aNT (blue) was positioned with its proximal lobe (which is comprised by the N and C termini of subunit a, domain nomenclature as in Ref. 46) near the connection point to the membrane-bound aCT, placing its distal lobe near the central density corresponding to subunit d (green). Because of its pseudo-3-fold symmetry and the limited resolution of the EM reconstruction, the yeast subunit d homology model could be fit in three orientations corresponding to rotational states 1, 2, and 3, as seen in the recent cryo-EM reconstructions of intact yeast V-ATPase (22). However, only the orientation corresponding to state 3 preserved the contact between the subunit d N-terminal α helix and the cytoplasmic face of the c subunit ring, as seen in the recent cryo-EM model of holo V-ATPase in state 3 (22) (Fig. 4g), and we therefore explored the contacts between aNT and d predicted by this configuration (Fig. 4h, see below). For filling the density corresponding to the yeast c-ring, we used the crystal structure of the K10 ring from Enterococcus hirae (47) (Fig. 4h, magenta).

Interaction of aNT and Subunit d

We previously reported a 3D reconstruction from cryo-EM images of detergent-solubilized yeast Vo that showed aNT and subunit d in close proximity (38). Although subsequent binding studies using recombinant aNT (residues 1–372, aNT(1–372)) and d revealed a Kd of the aNT(1–372)-d interaction of ∼5 μm (38), the resolution of the cryo-EM model, was insufficient to define the binding site(s) between aNT and d in detail. Fig. 4h illustrates the interface between aNT and subunit d based on the fitting of the homology models into the EM density of the VoND-CaM model presented here. As can be seen, aNT and subunit d appear to contact each other via two distinct sites near the proximal and distal lobes of aNT (Fig. 4h). The contact near the distal lobe (Fig. 4h, bottom right) is mediated by two short α helices, one from aNT (residues 242–256, yeast subunit a isoform Vph1p) and one from subunit d (residues 144–154). The other site near the proximal lobe of aNT is mediated by a short helix-turn-helix motif in d (residues 38–58) and a less well defined face in aNT (Fig. 4h, bottom left). Many of the acidic and basic residues involved in these two contact sites are highly conserved from yeast to human (see isothermal titration calorimetry sections below). Considering the conserved nature of the charged residues, we reasoned that complex formation between aNT and d could be driven by electrostatic interactions involving the conserved residues. To test this hypothesis, we generated aNT double (R250A,K251A) and quadruple mutants (K247A,R250A,K251A,E254A) in the short α helix in the distal lobe of aNT and triple (D144A,E146A,E150A) and quadruple (D37A,D40A,D41A,K43A) mutants in subunit d for in vitro binding experiments using isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC). As a negative control, we generated a triple mutant of d in an area predicted to be outside of the aNT-d contact area (E198A,E199A,E202A).

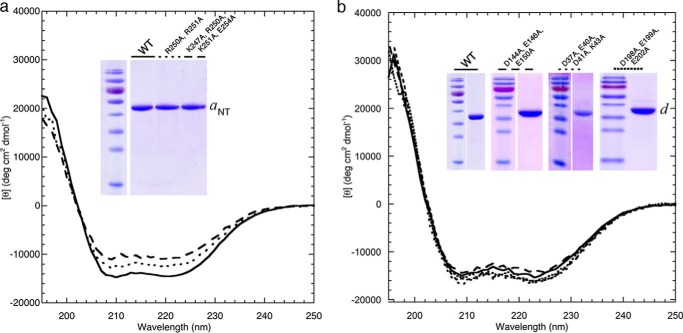

The wild type and alanine mutants of aNT(1–372) and subunit d were expressed as N-terminal fusions with maltose binding protein (MBP) connected via a protease cleavage site as described previously (38). The proteins were purified away from MBP via anion exchange and size exclusion chromatography. Purity and proper folding of the resulting aNT(1–372) and subunit d constructs was confirmed by Coomassie-stained SDS-PAGE and CD spectroscopy, respectively (Fig. 5, a and b). As can be seen from the CD spectra, all aNT(1–372) and subunit d mutant proteins showed minima at 208 and 222 nm similar to the wild-type subunits and characteristic for highly α-helical proteins, indicating that the mutations did not interfere with proper folding of the recombinant subunits.

FIGURE 5.

Purification and circular dichroism spectroscopy of recombinant wild-type and mutant aNT(1–372) and subunit d. a, Coomassie-stained SDS-PAGE and CD spectroscopy of the wild type and mutant aNT(1–372) constructs expressed and purified as described under “Experimental Procedures.” b, SDS-PAGE and CD spectra of the wild type and mutant subunit d. The two minima at ∼208 and 222 nm in the CD spectra of both the wild type and mutant aNT(1–372) and subunit d constructs indicate α-helical secondary structure. CD wavelength scans were collected from 250–195 nm in 25 mm sodium phosphate (pH 7) at 10 °C (0.1 mm TCEP was included in the buffer for the subunit d scans). SDS-PAGE gels were loaded with ∼3 μg of the wild type or mutant subunits.

Isothermal Titration Calorimetry of Mutant aNT(1–372) and Wild-type d

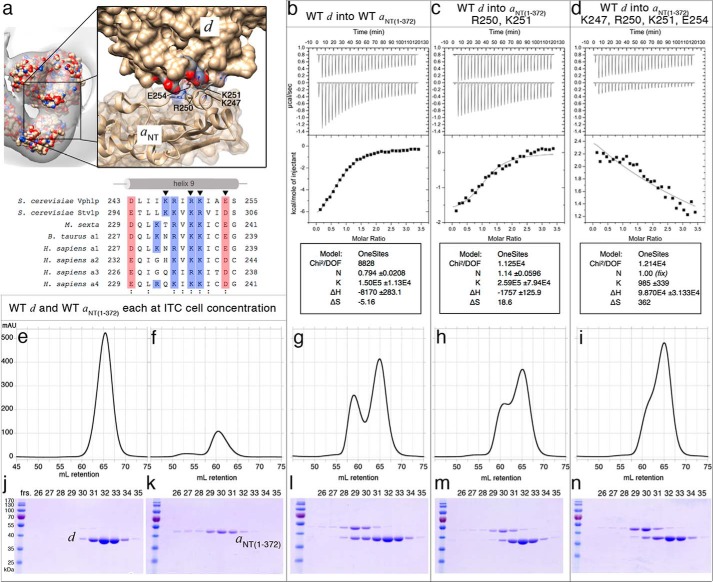

We first conducted ITC titrations with double and quadruple mutants of the conserved charged residues in the short α helix of the aNT distal domain that were facing subunit d (Fig. 6a). Titrating subunit d into wild-type aNT(1–372) revealed an exothermic binding reaction (Fig. 6b). Fitting the data with a single-site binding model revealed a ∼1:1 stoichiometry with a Kd of 6.7 μm, similar to what we obtained earlier by titrating aNT(1–372) into subunit d (38). The ΔH and ΔS were −34.2 kJ/mol and −21.6 J·(mol·K)−1, respectively, giving a ΔG of the enthalpy-driven binding reaction of −28.1 kJ/mol. Titrating subunit d into the double aNT(1–372) mutant (R250A,K251A) produced significantly less heat (ΔH = −7.4 kJ/mol), but, at the same time, the Kd was similar compared with the wild-type proteins (Kd = 4 μm, Fig. 6c) and appeared to be partly driven by entropy (ΔS = 77.8 J·(mol·K)−1, ΔG = −29.4 kJ/mol). On the other hand, titrating subunit d into the quadruple mutant of aNT(1–372) (K247A,R250A,K251A,E254A) resulted in a weak endothermic reaction that could not be fit to a single site model without fixing the stoichiometry at 1:1 (Fig. 6d). Under these conditions, the Kd was ∼1 mm, indicating that replacement of all four conserved charged residues by alanines disrupted the interaction between aNT(1–372) and d.

FIGURE 6.

Isothermal titration calorimetry of the interaction between subunit d and wild-type and mutant aNT(1–372). a, top panel, detailed view of the aNT/d contact as shown in Fig. 4h, bottom right, indicating that the distal lobe of aNT appears to be participating in an interaction with subunit d via a short charged α helix in aNT to a largely acidic face of subunit d. a, bottom panel, the four residues of the short α helix facing subunit d are Lys-247, Arg-250, Lys-251, and Glu-254, which belong to a patch of charged residues mostly conserved through higher eukaryotes, as shown by the sequence alignment of helix 9 of subunit a. b–d, isothermal titration calorimetry of subunit d and aNT(1–372) constructs (representative titrations of two repeats). Titration of subunit d into wild-type aNT(1–372) (b), aNT(1–372) (R250A,K251A) (c), and aNT(1–372) (K247A,R250A,K251A,E254A) (d). e–i, subunit d and aNT(1–372) alone as well as the cell contents of the completed titrations were subjected to size exclusion chromatography on Superdex 200 (16 × 500 mm) with the corresponding SDS-PAGE gels shown in j–n. For details, see text.

The cell contents of the ITC experiments (with titrated wild-type aNT(1–372), double mutant, and quadruple mutant) were subjected to size exclusion chromatography as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Subunit d and aNT(1–372) alone eluted at 65 and 60 ml, respectively (Fig. 6, e and f). Note that although subunit d alone runs as a monodisperse monomer (Fig. 6, e and j), aNT(1–372) exists in a concentration-dependent monomer-dimer equilibrium as reported earlier (38) and as evident from its elution profile and accompanying SDS-PAGE gel (Fig. 6, f and k). The elution profile of the mixture of wild-type aNT(1–372) and d revealed two peaks at 58 and 65 ml (Fig. 6g), and analysis by SDS-PAGE showed that the peak around 58 ml (fraction 29) contained close to stoichiometric amounts of aNT(1–372) and d (Fig. 6l). The relatively small shift of 2 ml (one fraction) toward larger molecular size is consistent with the moderate Kd of the aNT(1–372)-d complex formation of 6.7 μm and in close agreement with our previous study (38).

In the size exclusion profile of the double mutant titration (subunit d into aNT(1–372) R250A,K251A), the interacting peak is shifted slightly to a larger volume at ∼61 ml as a shoulder of the subunit d peak (∼66 ml) (Fig. 6h), indicating a weakening of the aNT(1–372)-d interaction and consistent with the reduced binding enthalpy and the SDS-PAGE gel of the peak fractions (Fig. 6m). This trend is continued for the titration of the quadruple mutant (subunit d into aNT(1–372) K247A,R250A,K251A,E254A), which only shows a shoulder for aNT unresolved from the subunit d peak (Fig. 6i) with elution profiles similar to the individual subunits (Fig. 6n). Taken together, the ITC and gel filtration data showed that mutation of the conserved charged residues on the short α helix in the distal domain of aNT disrupts the aNT-d interaction.

Isothermal Titration Calorimetry of Mutant d and Wild-type aNT(1–372)

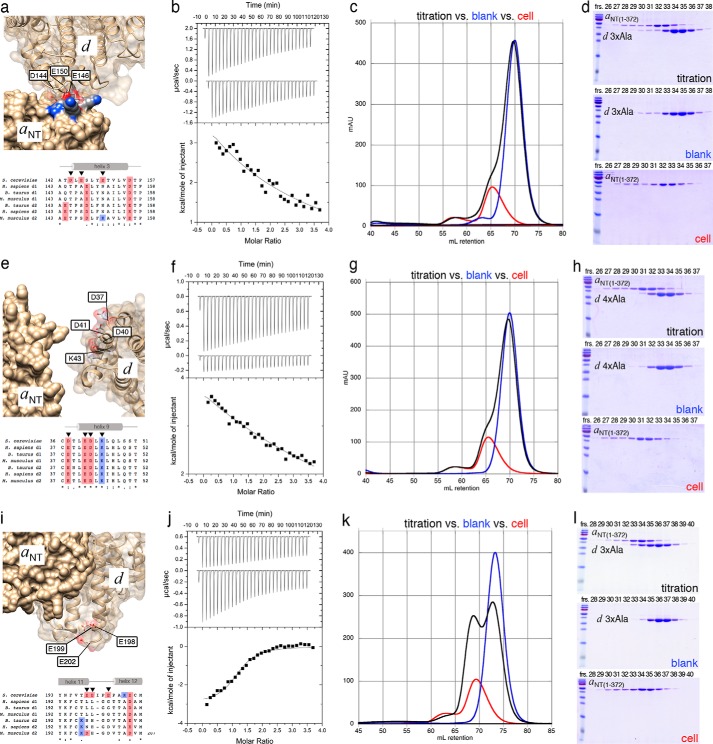

As mentioned above, subunit d appears to contact aNT at two sites, the short α helix in the distal domain and at a second site near the proximal domain (Fig. 4h). To verify the fit of subunit d in the EM model and to test whether the contact site near the proximal lobe of aNT contributes to the interaction between the two subunits, we generated triple and quadruple mutants of subunit d by replacing conserved charged residues that are facing aNT from the two sites on d (Fig. 7, a and e). ITC titrations of both triple (Fig. 7b) and quadruple (Fig. 7f) alanine mutants of d with wild-type aNT(1–372) revealed weak endothermic reactions that could not be fit to a single site binding model without fixing n = 1. Under these conditions, the Kds for the two titrations of the triple and quadruple mutants of d were ∼0.25 mm and ∼1.7 mm, respectively. Consistent with the ITC titrations, gel filtration profiles (Fig. 7, c and g) and SDS-PAGE of the peak fractions (Fig. 7, d and h) indicated elution of non-interacting subunits. Contrary to the alanine mutations of residues predicted to be in the aNT-d binding interface (Fig. 7, a–h), mutagenesis of a patch of acidic residues outside the interface (E198A,E199A,E202A) did not interfere with complex formation (Fig. 7, i–l). Taken together, the ITC and gel filtration experiments showed that both contact sites between aNT and d as seen in the EM fit contribute to the binding interaction between the two subunits. However, because disrupting either of the two sites weakened the interaction beyond detection by ITC or gel filtration, this suggests that the individual interactions are weak and that only the combined avidity of the two interactions results in a measurable affinity.

FIGURE 7.

Isothermal titration calorimetry of the interaction between wild-type aNT(1–372) and mutant subunit d. a and e, close-up of the contact between d and the aNT distal (a) and proximal (e) lobe. b–d, ITC (b), gel filtration (c), and SDS-PAGE (d) of the d triple mutant (D144A,E146A,E150A) with aNT(1–372). f–h, ITC (f), gel filtration (g), and SDS-PAGE (h) of the d quadruple mutant (D37A,E40A,D41A,K43A) with aNT(1–372). i–l, as a negative control, a subunit d mutant with acidic residues (Glu-198, Glu-199, and Glu-202) outside of the predicted interface with aNT changed to alanines was titrated with wild-type aNT(1–372). Fitting the data revealed a Ka of ∼4 ×105 ± 8 × 104 M (Kd ∼ 2.5 μm; N ∼ 1.2; ΔH = −12.4 ± 0.49 kJ/mol; ΔS ∼ 63 J·(mol·K)−1). Shown are representative ITC titrations of at least two repeats for each mutant. Note that the gel filtration column was repacked after the experiments in Fig. 6, resulting in a slightly different elution volume for the recombinant subunits for the two sets of titrations shown in Figs. 6 and 7.

Discussion

We have developed a protocol to reconstitute purified V-ATPase Vo membrane sector into lipid nanodiscs. When reconstituted into nanodiscs, Vo is stable, as evident from the lack of subunit a degradation products (Fig. 2e) sometimes seen in the detergent-solubilized complex (38). Negative stain EM showed that the preparation is monodisperse, and we were able to reconstruct 3D models of the nanodisc-bound Vo with and without calmodulin bound to the calmodulin binding peptide at the C terminus of subunit a. Fitting of aNT and subunit d homology models into the EM density revealed that the two subunits are in contact, as described previously for the negative stain and cryo-EM models of detergent solubilized bovine and yeast Vo, respectively (38, 44). However, the slightly better resolution of the VoND models allowed us to identify two sites of contact between aNT and d, both involving charged and highly conserved residues. ITC analysis of triple and quadruple alanine mutants of aNT and d confirmed the involvement of the charged residues in the interaction, but the analysis also showed that the individual interactions are weak and that only the combined avidity of both binding sites leads to a measurable Kd of ∼6 μm (Ref. 38 and the data presented here). As mentioned under “Introduction,” V-ATPase is regulated by a reversible disassembly mechanism that results in membrane-detached V1 and membrane-bound free Vo. A relatively moderate affinity between d and aNT can be rationalized by the fact that this interaction has to be broken when reassembly of holo V-ATPase is initiated.

A comparison of the VoND 3D models with the recent cryo-EM reconstructions of holo V-ATPase in three states (22) revealed that free Vo appears to be halted in rotary state 3 based on the orientation of subunit d relative to aNT. As mentioned under “Results,” because of the limited resolution of the VoND 3D models and because of the pseudo-3-fold symmetry of subunit d, d could also be fit in the state 2 orientation with a comparable model-map correlation compared with the state 3 fit (the fit of state 1 is of much lower quality, see Fig. 4). The ITC data, however, are only consistent with the state 3 orientation. Furthermore, only the state 3 orientation preserves the contact between the N-terminal α helix of d and the cytoplasmic loops of the proteolipid ring, as seen in the models of all three states of the holo enzyme (22). Taken together, the data therefore indicate that free Vo is halted in a single conformation corresponding to state 3 of holo V-ATPase.

Recently, we determined the 6.2- to 6.5-Å crystal structure of autoinhibited yeast V1-ATPase (40). Interestingly, a comparison of the structure of autoinhibited V1 with the structure of V1 as part of holo V-ATPase (22) revealed that the membrane-detached V1 is halted in state 2 based on the rotational position of the DF rotor relative to the inhibitory H subunit (40). The observation that autoinhibited V1 is halted in state 2 together with the findings presented here that free Vo is halted in state 3 indicates that there is a conformational mismatch between the two complexes as a result of regulated enzyme disassembly. We speculate that this mismatch may serve to prevent unintended reassembly of the enzyme when the disassembled state is required. How this mismatch is relieved when reassembly is required is not known, but it is possible that V1 binding to the assembly chaperone regulator of the H+-ATPase of vacuolar and endosomal membranes (RAVE) (48) changes V1 conformation to enable Vo binding. Another possibility is that the Vo conformation is altered by interaction with specific phosphoinositides that have been shown to bind to Vo and promote enzyme assembly on the vacuolar membrane (49).

Here we have shown that yeast Vo can be reconstituted into lipid nanodiscs, resulting in a highly monodisperse preparation that is amenable to structure determination by single-molecule EM. Future studies using cryo-EM will allow high-resolution structural studies of the complex in a more native environment compared with the detergent-solubilized state, allowing, for example, an examination of the interaction with specific lipid molecules that have been shown to be either essential for V-ATPase function (50) or involved in the mechanism of reversible enzyme disassembly (49). These studies are ongoing in our laboratory.

Experimental Procedures

Reagents

Undecyl-β-d-maltoside (UnDM) was from Anatrace. E. coli polar lipid extract was obtained from Avanti. Calmodulin-Sepharose beads were from GE Healthcare or Agilent. CDTA was from Fisher Scientific. All other reagents were of analytical grade.

Purification of Yeast Vo

Cell growth of a yeast strain expressing subunit a isoform Vph1p with a C-terminal fusion of calmodulin binding peptide, membrane preparation, and Vo extraction and purification were performed as described previously (38) with the following modifications. Yeast cells were harvested during the second log phase by centrifugation at 2600 × g, washed in water, and resuspended in lysis buffer (25 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 500 mm sorbitol, and 2 mm EGTA), and broken in a Bead Beater (Omni International) using zirconium beads (BioSpec). After removing cell debris and mitochondria by low-speed (2500 × g, 10 min) and medium-speed (12,000 × g, 20 min) centrifugation, membranes were collected by ultracentrifugation (370,000 × g, 2 h), washed once in buffer (25 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.4) and 500 mm sorbitol), and pelleted again (370,000 × g, 1 h). The total protein concentration of the membrane samples was determined by BCA protein assay (Thermo Scientific) of trichloroacetic acid-precipitated membranes. Isolated membranes were diluted to 10 mg/ml and stored at −80 °C until use.

Membranes were solubilized by addition of UnDM from a 20% stock solution in water to a final concentration of 0.6 mg of detergent/mg of membrane protein for 1 h with gentle agitation. Extracted membranes were supplemented with 4 mm CaCl2 and centrifuged at 180,000 × g for 1 h to remove the insoluble fraction. The supernatant was then applied to a 5-ml calmodulin-Sepharose column pre-equilibrated in calmodulin washing buffer (10 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8), 150 mm NaCl, 2 mm CaCl2, 10 mm β-mercaptoethanol, and 0.1% UnDM). The column was washed with 5 column volumes each of washing buffer and washing buffer without NaCl and eluted with elution buffer (10 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8), 10 mm CDTA, 10 mm β-mercaptoethanol, and 0.1% UnDM).

Preparation of Membrane Scaffold Protein

Membrane scaffold protein MSP1E3D1 (MSP) was expressed in E. coli BL21 (DE3) via a pET28a plasmid (Addgene, 20066) as described previously (51) with the following modifications. Briefly, the strain was grown to mid-log phase in terrific broth (25 g/liter Luria-Bertani-Miller broth (EMD Biosciences) supplemented with 0.4% (v/v) glycerol). Expression was induced with 1 mm isopropyl 1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside (BioVectra) for 1 h at 37 °C, followed by 3.5 h at 28 °C. Cells were harvested by centrifugation, resuspended in lysis buffer (25 mm sodium phosphate (pH 8) and 1% Triton X-100) and lysed with a French press (Spectronic Unicam). Lysate was cleared by centrifugation (17,000 × g) and passed over a nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid affinity column (Qiagen). The column was washed in place with each of three buffers: 40 mm Tris-HCl, 300 mm NaCl, and 1% Triton X-100, pH 8); 40 mm Tris-HCl, 300 mm NaCl, 50 mm sodium cholate, and 5 mm imidazole (pH 8); and 40 mm Tris-HCl, 300 mm NaCl, and 10 mm imidazole (pH 8). Protein was eluted with a 10-column volume linear gradient of elution buffer (40 mm Tris-HCl, 300 mm NaCl, and 100 mm imidazole (pH 8)) and dialyzed against 40 mm Tris-HCl, 100 mm NaCl, and 0.5 mm EDTA (pH 7.4). MSP-containing fractions were pooled and concentrated by ultrafiltration using an Amicon cell with an XM50 filter membrane. Purified MSP was stored at −80 °C until use.

Lipid Nanodisc Reconstitution of Vo

E. coli total lipid extract (Avanti Polar Lipids) was suspended by sonication in disc-forming buffer (20 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 100 mm NaCl, and 0.5 mm EDTA) with the addition of 1 mm DTT (EMD Millipore). Detergent-solubilized Vo, purified MSP, and lipid were combined at a molar ratio of 0.02:1:25 with the addition of protease inhibitors, 1 mm PMSF, 1 mm leupeptin, 1 mm pepstatin, and 1 mm chymostatin (EMD Biosciences) and incubated at room temperature for 1 h with mixing. Prewashed Bio-Beads SM-2 (Bio-Rad) were added at 0.4 g/ml and incubated with mixing for 2 h at room temperature. The self-assembled nanodisc sample was recovered from the Bio-Bead mixture with a syringe. To remove unfilled (empty) nanodiscs (ND) from Vo-containing discs (VoND), the reconstituted sample was supplemented with 10 mm CaCl2 and applied to a 1-ml calmodulin resin column, washed with disc-forming buffer and eluted with the same buffer without CaCl2 and supplemented with 10 mm CDTA. As a final polishing step, the eluted VoND sample was concentrated to 2 ml, applied to a Superdex 200 HR 16/500 column on an AKTA FPLC (GE Healthcare) equilibrated with disc-forming buffer and eluted at 0.5 ml/min.

Preparation of Calmodulin

The gene for human calmodulin 1 was synthesized (BioBasic, Markham, ON, Canada) and cloned into a modified pMAL-c2E expression vector with a Prescission protease cleavage site between MBP and the N terminus of calmodulin. Briefly, E. coli Rosetta 2 harboring the calmodulin expression plasmid was grown to mid-log phase in rich broth (Luria broth supplemented with 0.2% glucose), and expression was induced with 1 mm isopropyl 1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside for 18 h at 18 °C. Cells were harvested by centrifugation, resuspended in lysis buffer (20 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 200 mm NaCl, and 1 mm EDTA and lysed by sonication (Hielscher Ultrasonics). The lysate was cleared by centrifugation at 20,000 × g and passed over a pre-equilibrated amylose column (New England Biolabs). Bound protein was washed using the same buffer and eluted with the buffer supplemented with 10 mm maltose. Protein was cleaved using Prescission protease to remove the MBP tag and dialyzed into anion exchange buffer (20 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 1 mm EDTA, and 1 mm DTT). The sample was passed over a MonoQ anion exchange column attached to an FPLC and pre-equilibrated in buffer and eluted using a 30-column volume linear gradient of buffer to buffer plus 500 mm NaCl. Calmodulin-containing fractions were pooled, concentrated, and subjected to size exclusion chromatography (Superdex 75 16/500 column). For fluorescence detection of calmodulin, residue Ala-47 was changed to cysteine using QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis with the following primers: A47_fwd, GCC AGA ATC CAA CCG AAT GTG AAC TGC AAG ATA TGA TTA ACG; A47_rev, CGT TAA TCA TAT CTT GCA GTT CAC ATT CGG TTG GAT TCT GGC. For fluorescence detection, calmodulin (A47C) was reacted with fluorescein maleimide for 1 h in the dark. Excess label was removed by a Sephadex G25 spin column.

Labeling of VoND with Calmodulin

Purified calmodulin was added in a 5:1 molar ratio to VoND, and the sample was loaded onto a discontinuous glycerol gradient (15–35% (v/v), 10 mm MOPS (pH 7), and 4 mm CaCl2) for separation of unbound calmodulin. The gradient was subjected to centrifugation at 285,000 × g for 16 h. Afterward, 1-ml fractions were collected by fractionation from the bottom of the gradient and analyzed by SDS-PAGE.

Electron Microscopy

Carbon-coated copper grids were subjected to glow discharge in air for 45 s. Samples of VoND and calmodulin-labeled VoND (VoND-CaM) at ∼1 mg/ml were diluted 1:100 in 20 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.4) and 150 mm NaCl supplemented with 0.5 mm EDTA or 4 mm CaCl2, respectively, and applied to glow-discharged grids for 1 min, washed with water, and stained with 2% (w/v) uranyl formate (Electron Microscopy Science). Grids were observed in a JEOL JEM-2100 transmission electron microscope operating at 200 kV. Images were acquired on a charge-coupled device (F415MP, Tietz Video and Image Processing Systems GmbH) at a nominal magnification of ×60,000 and an underfocus of between ∼1–2 μm. The calibrated pixel size on the specimen level was 1.75 Å.

Image Analysis and 3D Reconstruction

Single particles were selected (192 × 192 pixels) using e2boxer from EMAN2 with a semiautomated monitored picking procedure. Particles were phase flip-corrected for their contrast transfer functions by micrograph within the EMAN2 package. Datasets of 47,422 and 40,092 particles were collected for VoND and VoND-CaM, respectively. The datasets were normalized, bandpass-filtered, binned by 2, and circularly masked. Datasets were analyzed using reference-free alignment as implemented in EMAN2.

Twenty-seven class averages from the CaM-VoND dataset were selected for use as initial references in a startup procedure for 3D reconstruction. Initial models were generated using the standard EMAN2 procedure and subjected to seven rounds of refinement. The resulting model was low pass-filtered to 40 Å and used to start up automated 3D refinement in Relion 1.3 (52). Half-datasets were refined independently for six iterations, and the unfiltered final maps served as inputs to the “relion_postprocess” protocol for automatic masking and a resolution estimate from calculation of the corrected gold standard Fourier shell correlation (FSC). The resolution was estimated at 14.9 Å using the 0.143 gold standard FSC cutoff (20.3 Å at 0.5 FSC). The final model was filtered to 40 Å and used as a reference for starting up the 3D reconstruction of the VoND dataset using the Relion 1.3 autorefinement procedure as described above for the VoND-CaM dataset. The resolution of the VoND reconstruction was estimated at 14.9 Å using the 0.143 FSC cutoff (16.3 Å at 0.5 FSC).

Fitting of Atomic Models of Subunits

We used the atomic structure of the K10 ring from E. hirae (PDB code 2BL2) to fit into the corresponding density for the yeast Vo c-ring. Homology models were calculated using Phyre2 (53) for aNT and subunit d against template bacterial subunit structures of Meiothermus ruber INT (PDB code 3RRK) and Thermus thermophilus C subunit (PDB code 1V9M). Semiautomated and manual docking of the structures was performed in Chimera (54).

Site-directed Mutagenesis of aNT(1–372) and Subunit d

The aNT(1–372) and subunit d constructs used in this study have been described previously (38). Site-directed mutagenesis was done using the QuikChange protocol (Stratagene). Double (R250A,K251A) and quadruple (K247A,R250,K251A,E254A) alanine mutants of aNT(1–372) were generated using the following primers: vph1–372-r250a-k251a-F, CTC ACG GTG ATC TGA TTA TTA AAA GAA TCG CAG CGA TTG CGG AAT CAT TGG ATG; vph1–372-r250a-k251a-R, GTA AAG ATT GGC ATC CAA TGA TTC CGC AAT CGC TGC GAT TCT TTT AAT AAT C. The quadruple mutant was generated in two steps using the double mutant as template with the following primers: vph1–372-e254a-F, CTG ATT ATT AAA AGA ATC GCA GCG ATT GCG GCA TCA TTG GAT GCC AAT C; vph1–372-e254a-R, GAT TGG CAT CGT AAA GAT TGG CAT CCA ATG ATG CCG CAA TCG CTG CGA TT; vph1–372-k247a-F, GTA TTT TCT CAC GGT GAT CTG ATT ATT GCA AGA ATC GCA GCG ATT GCG GCA TC; vph1–372-k247a-R, CAT CCA ATG ATG CCG CAA TCG CTG CGA TTC TTG CAA TAA TCA GAT CAC CGT GAG.

The triple alanine mutant construct of subunit d (D144A,E146A,E150A) was generated in two separate mutagenesis steps (D144A and E146A followed by E150A) using the following primers: m6-d144a-e146a-F, GTT GAG TGT TGC TAC TGC TCT TGC ATC CCT ATA CGA AAC CG; m6-d144a-e146a-R, CGG TTT CGT ATA GGG ATG CAA GAG CAG TAG CAA CAC TCA AC; m6-d144a-e146a-e150a-F, GCT CTT GCA TCC CTA TAC GCA ACC GTA TTG GTG GAT ACC; m6-d144a-e146a-e150a-R, GGT ATC CAC CAA TAC GGT TGC GTA TAG GGA TGC AAG AGC. The quadruple alanine mutant construct of subunit d (D37A, E40A, D41A, K43A) was generated in three sequential mutagenesis steps using the following primers: m6-a110c-F, ATA CAT CAA CTT AAC ACA ATG TGC CAC GTT GGA AGA TCT AAA ATT AC; m6–110-R, GTA ATT TTA GAT CTT CCA ACG TGG CAC ATT GTG TTA AGT TGA TGT AT; m6-a110c-a119c-a122c-F, CTT AAC ACA ATG TGC CAC GTT GGC AGC TCT AAA ATT ACA ATT ATC ATC AAC; m6-a110c-a119c-a122c-R, GTT GAT GAT AAT TGT AAT TTT AGA GCT GCC AAC GTG GCA CAT TGT GTT AAG; m6-a110c-a119c-a122c-a127g-a128c-F, CAA TGT GCC ACG TTG GCA GCT CTA GCA TTA CAA TTA TCA TCA ACT GAT TAT; m6-a110c-a119c-a122c-a127g-a128c-R, ATA ATC AGT TGA TGA TAA TTG TAA TGC TAG AGC TGC CAA CGT GGC ACA TTG. A second triple alanine mutant of subunit d (E198A,E199A,E202A; ITC control mutant) was generated in two steps using the following primers: M6_a593c_a596c_F, AAG ACT TTT ACA ATT TTG TCA CTG CAG CAA TTC CGG AAC CTG CTA AAG AAT G; M6_a593c_a596c_R, CAT TCT TTA GCA GGT TCC GGA ATT GCT GCA GTG ACA AAA TTG TAA AAG TCT T; M6_a605c_F, CAC TGC AGC AAT TCC GGC ACC TGC TAA AGA ATG TA; M6_a605c_R, TAC ATT CTT TAG CAG GTG CCG GAA TTG CTG CAG TG. The sequences of the aNT(1–372) and subunit d constructs were confirmed by DNA sequencing (Eurofins) using MalE and M13 primers (New England Biolabs).

Circular Dichroism Spectroscopy

Far UV CD spectra of aNT(1–372) and subunit d constructs were collected on an Aviv 420 spectrometer in 25 mm sodium phosphate (pH 7.4) in a 1-mm path length cuvette at 10 °C. For the subunit d scans, 0.1 mm tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP) was included in the buffer. Scans of buffer only were subtracted from the spectra.

Isothermal Titration Calorimetry

The interactions between subunit d and aNT(1–372) constructs were determined using a VP-ITC (MicroCal). Proteins were prepared in 20 mm Tris (pH 7), 0.5 mm EDTA, and 1 mm TCEP at 10 °C. Ligand (subunit d, 370–400 μm) was titrated into solutions of aNT(1–372) constructs (25 μm). The titrations were corrected for ligand heat of dilution by subtraction of blank experiments of ligand into buffer. Analysis of data was performed using MicroCal VP-ITC Origin software. After completion of the titrations, the cell contents were subjected to size exclusion chromatography over a Superdex 200 H/R 16/500 column. At least two titrations were performed for each wild type and mutant construct combinations.

Other Methods

Protein concentrations were determined using the BCA assay (Pierce) after TCA precipitation of proteins as described previously (38). Site-directed mutagenesis was verified by DNA sequencing (Eurofins).

Author Contributions

N. J. S. and S. W. designed the study. All experiments were carried out by N. J. S. N. J. S. and S. W. wrote the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Steven Ludtke for advice regarding data processing using the EMAN software package. We thank Dr. Stewart Loh for assistance with CD data collection. Sergio Couoh-Cardel is acknowledged for advice with Vo purification and Dr. Rebecca Oot and Stuti Sharma for helpful discussions.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant GM058600 (to S. W.). The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

The 3D EM reconstructions of VoND and VoND-CaM have been deposited in the EMDB with accession numbers EMD-6335 and EMD-6336, respectively.

- V-ATPase

- vacuolar ATPase

- Vo

- membrane sector of the vacuolar ATPase

- VoND

- membrane sector of the vacuolar ATPase reconstituted in lipid nanodiscs

- aNT

- N-terminal cytoplasmic domain of the a subunit

- CaM

- calmodulin

- FSC

- Fourier shell correlation

- ITC

- isothermal titration calorimetry

- MBP

- maltose binding protein

- UnDM

- undecyl-β-d-maltoside

- MSP

- MSP1E3D1

- TCEP

- tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine.

References

- 1.Forgac M. (2007) Vacuolar ATPases: rotary proton pumps in physiology and pathophysiology. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8, 917–929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kane P. M. (2006) The where, when, and how of organelle acidification by the yeast vacuolar H+-ATPase. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 70, 177–191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marshansky V., and Futai M. (2008) The V-type H+-ATPase in vesicular trafficking: targeting, regulation and function. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 20, 415–426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Graham L. A., Flannery A. R., and Stevens T. H. (2003) Structure and assembly of the yeast V-ATPase. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 35, 301–312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zoncu R., Bar-Peled L., Efeyan A., Wang S., Sancak Y., and Sabatini D. M. (2011) mTORC1 senses lysosomal amino acids through an inside-out mechanism that requires the vacuolar H+-ATPase. Science 334, 678–683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xu Y., Parmar A., Roux E., Balbis A., Dumas V., Chevalier S., and Posner B. I. (2012) Epidermal growth factor-induced vacuolar (H+)-ATPase assembly: a role in signaling via mTORC1 activation. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 26409–26422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yan Y., Denef N., and Schüpbach T. (2009) The vacuolar proton pump, V-ATPase, is required for notch signaling and endosomal trafficking in Drosophila. Dev. Cell 17, 387–402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sun-Wada G. H., Toyomura T., Murata Y., Yamamoto A., Futai M., and Wada Y. (2006) The a3 isoform of V-ATPase regulates insulin secretion from pancreatic β-cells. J. Cell Sci. 119, 4531–4540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vavassori S., and Mayer A. (2014) A new life for an old pump: V-ATPase and neurotransmitter release. J. Cell Biol. 205, 7–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Inoue H., Noumi T., Nagata M., Murakami H., and Kanazawa H. (1999) Targeted disruption of the gene encoding the proteolipid subunit of mouse vacuolar H+-ATPase leads to early embryonic lethality. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1413, 130–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith A. N., Skaug J., Choate K. A., Nayir A., Bakkaloglu A., Ozen S., Hulton S. A., Sanjad S. A., Al-Sabban E. A., Lifton R. P., Scherer S. W., and Karet F. E. (2000) Mutations in ATP6N1B, encoding a new kidney vacuolar proton pump 116-kD subunit, cause recessive distal renal tubular acidosis with preserved hearing. Nat. Genet. 26, 71–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thudium C. S., Jensen V. K., Karsdal M. A., and Henriksen K. (2012) Disruption of the V-ATPase functionality as a way to uncouple bone formation and resorption: a novel target for treatment of osteoporosis. Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 13, 141–151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Williamson W. R., and Hiesinger P. R. (2010) On the role of v-ATPase V0a1-dependent degradation in Alzheimer disease. Commun. Integr. Biol. 3, 604–607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brown D., Smith P. J., and Breton S. (1997) Role of V-ATPase-rich cells in acidification of the male reproductive tract. J. Exp. Biol. 200, 257–262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Karet F. E., Finberg K. E., Nelson R. D., Nayir A., Mocan H., Sanjad S. A., Rodriguez-Soriano J., Santos F., Cremers C. W., Di Pietro A., Hoffbrand B. I., Winiarski J., Bakkaloglu A., Ozen S., Dusunsel R., et al. (1999) Mutations in the gene encoding B1 subunit of H+-ATPase cause renal tubular acidosis with sensorineural deafness. Nat. Genet. 21, 84–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sennoune S. R., Bakunts K., Martínez G. M., Chua-Tuan J. L., Kebir Y., Attaya M. N., and Martínez-Zaguilán R. (2004) Vacuolar H+-ATPase in human breast cancer cells with distinct metastatic potential: distribution and functional activity. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 286, C1443–C1452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wong D., Bach H., Sun J., Hmama Z., and Av-Gay Y. (2011) Mycobacterium tuberculosis protein tyrosine phosphatase (PtpA) excludes host vacuolar-H+-ATPase to inhibit phagosome acidification. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 19371–19376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xu L., Shen X., Bryan A., Banga S., Swanson M. S., and Luo Z. Q. (2010) Inhibition of host vacuolar H+-ATPase activity by a Legionella pneumophila effector. PLoS Pathog. 6, e1000822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kartner N., and Manolson M. F. (2014) Novel techniques in the development of osteoporosis drug therapy: the osteoclast ruffled-border vacuolar H+-ATPase as an emerging target. Expert. Opin. Drug Discov. 9, 505–522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fais S., De Milito A., You H., and Qin W. (2007) Targeting vacuolar H+-ATPases as a new strategy against cancer. Cancer Res. 67, 10627–10630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bowman E. J., and Bowman B. J. (2005) V-ATPases as drug targets. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 37, 431–435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhao J., Benlekbir S., and Rubinstein J. L. (2015) Electron cryomicroscopy observation of rotational states in a eukaryotic V-ATPase. Nature 521, 241–245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Powell B., Graham L. A., and Stevens T. H. (2000) Molecular characterization of the yeast vacuolar H+-ATPase proton pore. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 23654–23660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wilkens S. (2005) Rotary molecular motors. Adv. Protein Chem. 71, 345–382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Muench S. P., Trinick J., and Harrison M. A. (2011) Structural divergence of the rotary ATPases. Q. Rev. Biophys. 44, 311–356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kane P. M. (1995) Disassembly and reassembly of the yeast vacuolar H+-ATPase in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 17025–17032 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sumner J. P., Dow J. A., Earley F. G., Klein U., Jäger D., and Wieczorek H. (1995) Regulation of plasma membrane V-ATPase activity by dissociation of peripheral subunits. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 5649–5653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kane P. M. (2012) Targeting reversible disassembly as a mechanism of controlling V-ATPase activity. Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 13, 117–123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lafourcade C., Sobo K., Kieffer-Jaquinod S., Garin J., and van der Goot F. G. (2008) Regulation of the V-ATPase along the endocytic pathway occurs through reversible subunit association and membrane localization. PLoS ONE 3, e2758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sautin Y. Y., Lu M., Gaugler A., Zhang L., and Gluck S. L. (2005) Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-mediated effects of glucose on vacuolar H+-ATPase assembly, translocation, and acidification of intracellular compartments in renal epithelial cells. Mol. Cell Biol. 25, 575–589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Trombetta E. S., Ebersold M., Garrett W., Pypaert M., and Mellman I. (2003) Activation of lysosomal function during dendritic cell maturation. Science 299, 1400–1403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Parra K. J., and Kane P. M. (1998) Reversible association between the V1 and V0 domains of yeast vacuolar H+-ATPase is an unconventional glucose-induced effect. Mol. Cell Biol. 18, 7064–7074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Delamarre L., Pack M., Chang H., Mellman I., and Trombetta E. S. (2005) Differential lysosomal proteolysis in antigen-presenting cells determines antigen fate. Science 307, 1630–1634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Voss M., Vitavska O., Walz B., Wieczorek H., and Baumann O. (2007) Stimulus-induced phosphorylation of vacuolar H+-ATPase by protein kinase A. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 33735–33742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Parra K. J., Keenan K. L., and Kane P. M. (2000) The H subunit (Vma13p) of the yeast V-ATPase inhibits the ATPase activity of cytosolic V1 complexes. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 21761–21767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gräf R., Harvey W. R., and Wieczorek H. (1996) Purification and properties of a cytosolic V1-ATPase. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 20908–20913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang J., Feng Y., and Forgac M. (1994) Proton conduction and bafilomycin binding by the V0 domain of the coated vesicle V-ATPase. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 23518–23523 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Couoh-Cardel S., Milgrom E., and Wilkens S. (2015) Affinity purification and structural features of the yeast vacuolar ATPase Vo membrane sector. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 27959–27971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Diab H. I., and Kane P. M. (2013) Loss of vacuolar H+-ATPase (V-ATPase) activity in yeast generates an iron deprivation signal that is moderated by induction of the peroxiredoxin TSA2. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 11366–11377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Oot R. A., Kane P. M., Berry E. A., and Wilkens S. (2016) Crystal Structure of Yeast V1-ATPase in the Autoinhibited State. EMBO J. 35, 1694–1706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang Z., Zheng Y., Mazon H., Milgrom E., Kitagawa N., Kish-Trier E., Heck A. J., Kane P. M., and Wilkens S. (2008) Structure of the yeast vacuolar ATPase. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 35983–35995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Benlekbir S., Bueler S. A., and Rubinstein J. L. (2012) Structure of the vacuolar-type ATPase from Saccharomyces cerevisiae at 11-A resolution. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 19, 1356–1362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Muench S. P., Scheres S. H., Huss M., Phillips C., Vitavska O., Wieczorek H., Trinick J., and Harrison M. A. (2014) Subunit positioning and stator filament stiffness in regulation and power transmission in the V1 motor of the Manduca sexta V-ATPase. J. Mol. Biol. 426, 286–300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wilkens S., and Forgac M. (2001) Three-dimensional structure of the vacuolar ATPase proton channel by electron microscopy. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 44064–44068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Oot R. A., Kane P. M., Berry E. A., and Wilkens S. (2016) Crystal structure of yeast V1-ATPase in the autoinhibited state. EMBO J. 35, 1694–1706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Srinivasan S., Vyas N. K., Baker M. L., and Quiocho F. A. (2011) Crystal structure of the cytoplasmic N-terminal domain of subunit I, a homolog of subunit a, of V-ATPase. J. Mol. Biol. 412, 14–21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Murata T., Yamato I., Kakinuma Y., Leslie A. G., and Walker J. E. (2005) Structure of the rotor of the V-Type Na+-ATPase from Enterococcus hirae. Science 308, 654–659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Smardon A. M., Nasab N. D., Tarsio M., Diakov T. T., and Kane P. M. (2015) Molecular interactions and cellular itinerary of the yeast RAVE (regulator of the H+-ATPase of vacuolar and endosomal membranes) complex. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 27511–27523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li S. C., Diakov T. T., Xu T., Tarsio M., Zhu W., Couoh-Cardel S., Weisman L. S., and Kane P. M. (2014) The signaling lipid PI(3,5)P(2) stabilizes V(1)-V(o) sector interactions and activates the V-ATPase. Mol. Biol. Cell 25, 1251–1262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chung J. H., Lester R. L., and Dickson R. C. (2003) Sphingolipid requirement for generation of a functional v1 component of the vacuolar ATPase. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 28872–28881 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ritchie T. K., Grinkova Y. V., Bayburt T. H., Denisov I. G., Zolnerciks J. K., Atkins W. M., and Sligar S. G. (2009) Chapter 11: reconstitution of membrane proteins in phospholipid bilayer nanodiscs. Methods Enzymol. 464, 211–231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Scheres S. H. (2012) RELION: implementation of a Bayesian approach to cryo-EM structure determination. J. Struct. Biol. 180, 519–530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kelley L. A., Mezulis S., Yates C. M., Wass M. N., and Sternberg M. J. (2015) The Phyre2 web portal for protein modeling, prediction and analysis. Nat. Protoc. 10, 845–858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pettersen E. F., Goddard T. D., Huang C. C., Couch G. S., Greenblatt D. M., Meng E. C., and Ferrin T. E. (2004) UCSF Chimera: a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 25, 1605–1612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]