Abstract

RNA degradation is crucial for regulating gene expression in all organisms. Like the decapping of eukaryotic mRNAs, the conversion of the 5′-terminal triphosphate of bacterial transcripts to a monophosphate can trigger RNA decay by exposing the transcript to attack by 5′-monophosphate-dependent ribonucleases. In both biological realms, this deprotection step is catalyzed by members of the Nudix hydrolase family. The genome of the gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori, a Gram-negative epsilonproteobacterium, encodes two proteins resembling Nudix enzymes. Here we present evidence that one of them, HP1228 (renamed HpRppH), is an RNA pyrophosphohydrolase that triggers RNA degradation in H. pylori, whereas the other, HP0507, lacks such activity. In vitro, HpRppH converts RNA 5′-triphosphates and diphosphates to monophosphates. It requires at least two unpaired nucleotides at the 5′ end of its substrates and prefers three or more but has only modest sequence preferences. The influence of HpRppH on RNA degradation in vivo was examined by using RNA-seq to search the H. pylori transcriptome for RNAs whose 5′-phosphorylation state and cellular concentration are governed by this enzyme. Analysis of cDNA libraries specific for transcripts bearing a 5′-triphosphate and/or monophosphate revealed at least 63 potential HpRppH targets. These included mRNAs and sRNAs, several of which were validated individually by half-life measurements and quantification of their 5′-terminal phosphorylation state in wild-type and mutant cells. These findings demonstrate an important role for RppH in post-transcriptional gene regulation in pathogenic Epsilonproteobacteria and suggest a possible basis for the phenotypes of H. pylori mutants lacking this enzyme.

Keywords: gene regulation, Helicobacter pylori, RNA degradation, RNA modification, RNA turnover, RNA-protein interaction, Nudix, deep sequencing

Introduction

Helicobacter pylori is a Gram-negative, microaerophilic epsilonproteobacterium that colonizes the stomachs of more than 50% of the world's population (1). Infection by this microorganism is associated with the development of gastritis, peptic ulcers, and adenocarcinoma (2). A variety of H. pylori proteins important for colonization and pathogenesis have been identified, but little is yet understood about how the biosynthesis of these factors is controlled, especially at the post-transcriptional level. For example, although RNA degradation is among the principal post-transcriptional mechanisms that control gene expression in all organisms, little is known about this process in Epsilonproteobacteria.

Much of what is understood about bacterial mRNA decay has come from studies of Escherichia coli. Most mRNAs in E. coli and other Gammaproteobacteria are degraded by a combination of endonucleolytic cleavage by ribonuclease E (RNase E) and 3′-exonucleolytic digestion by polynucleotide phosphorylase, RNase II, and RNase R (3). Although Epsilonproteobacteria contain homologs of the principal 3′-exonucleases present in E. coli, they lack RNase E (4, 5). Instead, to degrade mRNA, they rely on two ribonucleases absent from Gammaproteobacteria but present in Gram-positive bacteria: the endonuclease RNase Y and the 5′-exonuclease RNase J (6–9).

When initially synthesized, the 5′ ends of bacterial transcripts typically are triphosphosphorylated. However, RNase J and RNase E favor RNA substrates that have only one 5′-terminal phosphate (10, 11). This property has two important consequences. First, it enables these enzymes to rapidly degrade monophosphosphorylated intermediates generated by prior ribonuclease cleavage (12). Furthermore, it can assist them in attacking full-length transcripts whose 5′-triphosphate has been converted to a monophosphate by an RNA pyrophosphohydrolase (11, 13).

Every bacterial RNA pyrophosphohydrolase that has so far been identified is a member of the Nudix hydrolase family of proteins, as are most eukaryotic RNA decapping enzymes (14–16). Nudix enzymes are present in all domains of life and have a variety of biochemical functions, most of which appear to involve the hydrolysis of substrates that contain a nucleoside diphosphate moiety (17). Besides their role in initiating RNA degradation (11, 13, 15, 19, 20), these enzymes have been implicated in a variety of metabolic pathways, such as those governing the synthesis or breakdown of folic acid (21), coenzyme A (22), ADP-ribose (23, 24), UDP-glucose (25), and mutagenic nucleotides such as 8-oxo-dGTP (26, 27).

The genomes of most species encode multiple Nudix enzymes, which can be identified by a characteristic sequence motif (the Nudix motif) (27) that usually is well conserved (17). Protein domains containing this motif typically fold so as to form a central four-stranded mixed β sheet (β strands 1, 3, 4, and 5) and an antiparallel β sheet (β strands 2 and 6) sandwiched between three α helices (α1, α2, and α3) (27). Those that act as RNA pyrophosphohydrolases (known by the genetic acronym RppH) are widespread in bacteria. However, their evolutionary divergence has made many of them difficult to identify on the basis of sequence alone. So far, two distinct families of RppH enzymes with recognizable sequence characteristics have been defined: those found in Alpha-, Beta-, Gamma-, and Epsilonproteobacteria and in flowering plants (E. coli RppH homologs) and those found in Bacillales but not in other Firmicutes (Bacillus subtilis RppH homologs) (16). These two families differ in their substrate specificity due to sequence differences external to the Nudix motif (16, 19, 28).

In addition to homologs of RNase J and RNase Y, the small genome of H. pylori (5) encodes two potential Nudix hydrolases, HP1228 and HP0507. HP1228 is able to catalyze the hydrolysis of the dinucleoside tetraphosphate Ap4A in vitro (29), and it appears from its sequence to be a homolog of E. coli RppH. However, its ability to function as an RNA pyrophosphohydrolase has never been examined, either in vitro or in vivo, and no H. pylori RNAs whose longevity is HP1228-dependent have ever been identified. Here we report the identification and characterization of HP1228 as an RNA pyrophosphohydrolase in H. pylori (HpRppH). Our studies demonstrate the ability of the purified protein to convert 5′-terminal triphosphates to monophosphates and define its substrate specificity. By employing RNA-seq methods selective for either triphosphorylated or monophosphorylated 5′ ends, we have identified mRNAs and sRNAs targeted by this enzyme in H. pylori. By contrast, HP0507 appears to lack RNA pyrophosphohydrolase activity.

Results

The H. pylori Genome Encodes a Potential RppH Homolog

In E. coli, 5′-end-dependent RNA degradation is triggered by the RNA pyrophosphohydrolase RppH, a member of the Nudix hydrolase family (13). Like other members of this protein family, E. coli RppH contains a Nudix motif (GX5EX7REUXEEXGU, where U is a bulky aliphatic residue and X is any amino acid) (27), a telltale signature of Nudix domains (17). Examination of the genome of H. pylori strain 26695 (5) for encoded proteins that bear a Nudix motif revealed two candidates, HP1228 and HP0507 (29, 30). HP1228 contains a region that matches this motif at eight of nine positions (GX5EX7REUXEEXGT; mismatch underlined), whereas HP0507 matches the motif at only four positions (LX5KX7EEAXEEXGY; mismatches underlined). The sequence of HP1228, which is well conserved in other Epsilonproteobacteria (see the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes website), is 34% identical to that of E. coli RppH (EcRppH) and contains each of the 23 amino acid residues that are strictly conserved in virtually all proteobacterial orthologs of EcRppH (Fig. 1A) (16). These sequence characteristics suggest that HP1228, like EcRppH, is an RNA pyrophosphohydrolase. We modeled the three-dimensional structure of HP1228 by using the X-ray crystal structure of EcRppH (31) as a template (Fig. 1, B and C). Most of the residues that are identical in these two proteins are clustered around a cavity that functions as the substrate-binding site and catalytic center of EcRppH. These residues include four glutamates that coordinate Mg2+ ions as well as other amino acids implicated in substrate recognition (16, 31). By contrast, the 19 residues that comprise the carboxyl terminus of EcRppH are entirely absent in HP1228 and many other EcRppH orthologs (16).

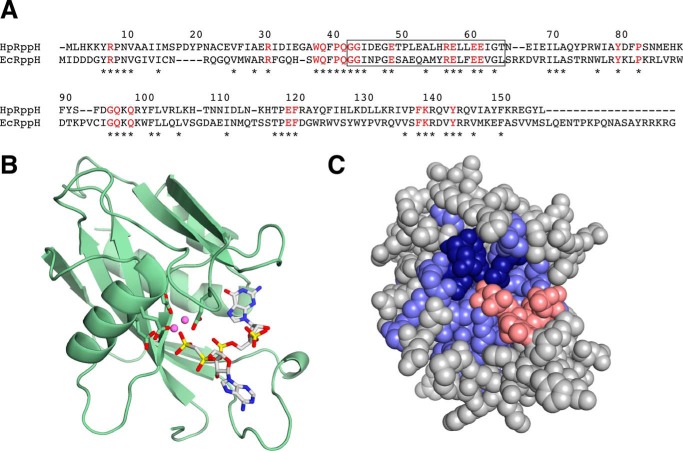

FIGURE 1.

RppH alignment and structure. A, alignment of HpRppH (HP1228) and EcRppH. The sequences were aligned by analysis with ClustalW (18). Asterisks mark amino acid residues that are identical in the two sequences. Residues that are conserved in virtually all bacterial orthologs of EcRppH (16) are depicted as red letters. The region containing the Nudix motif is enclosed in a rectangle. Numbers correspond to the sequence of HpRppH. B and C, structural model of HpRppH bound to an RNA ligand. The structure of HpRppH was modeled by homology to the X-ray crystal structure of EcRppH bound to an oligonucleotide ligand and two Mg2+ ions (Protein Data Bank code 4S2X) (31) by using SWISS-MODEL on the ExPASy bioinformatics website (50). B, ribbon model. Green ribbon, HpRppH backbone. The four glutamate side chains (Glu-57, Glu-60, Glu-61, and Glu-118; sticks) that coordinate Mg2+ ions (violet spheres) are also shown. The diphosphorylated RNA ligand is depicted in a stick representation. C, space-fill model. Blue, HpRppH residues that are identical in EcRppH, which include the four glutamate residues (dark blue) that coordinate Mg2+ (not shown). Gray, HpRppH residues that differ from EcRppH. Red, diphosphorylated RNA ligand.

HpRppH Functions in Vitro as an RNA Pyrophosphohydrolase

Cellular phenotypes such as decreased resistance to hydrogen peroxide exposure (29) and a diminished ability to invade gastric epithelial cells (32) have been reported for H. pylori mutants unable to produce HP1228. However, the molecular function of this protein has remained unclear. To address this question, we tested HP1228 in vitro for RNA pyrophosphohydrolase activity. A 0.44-kb triphosphorylated rpsT RNA substrate (13) bearing a 5′-terminal γ-32P label and an internal fluorescein label was treated with purified HP1228, and reaction samples were quenched at time intervals. The reaction products were then split into two portions and examined by gel electrophoresis and thin layer chromatography. HP1228 removed the radiolabel from the 5′ end of the transcript (Fig. 2A, top), yielding a mixture of radioactive pyrophosphate and orthophosphate (Fig. 2B). No such activity was observed for an HP1228 mutant in which an essential active site residue had been replaced (E57Q). γ-Phosphate removal by purified HP1228 was not accompanied by degradation of the transcript, whose fluorescence intensity was invariant (Fig. 2A, bottom).

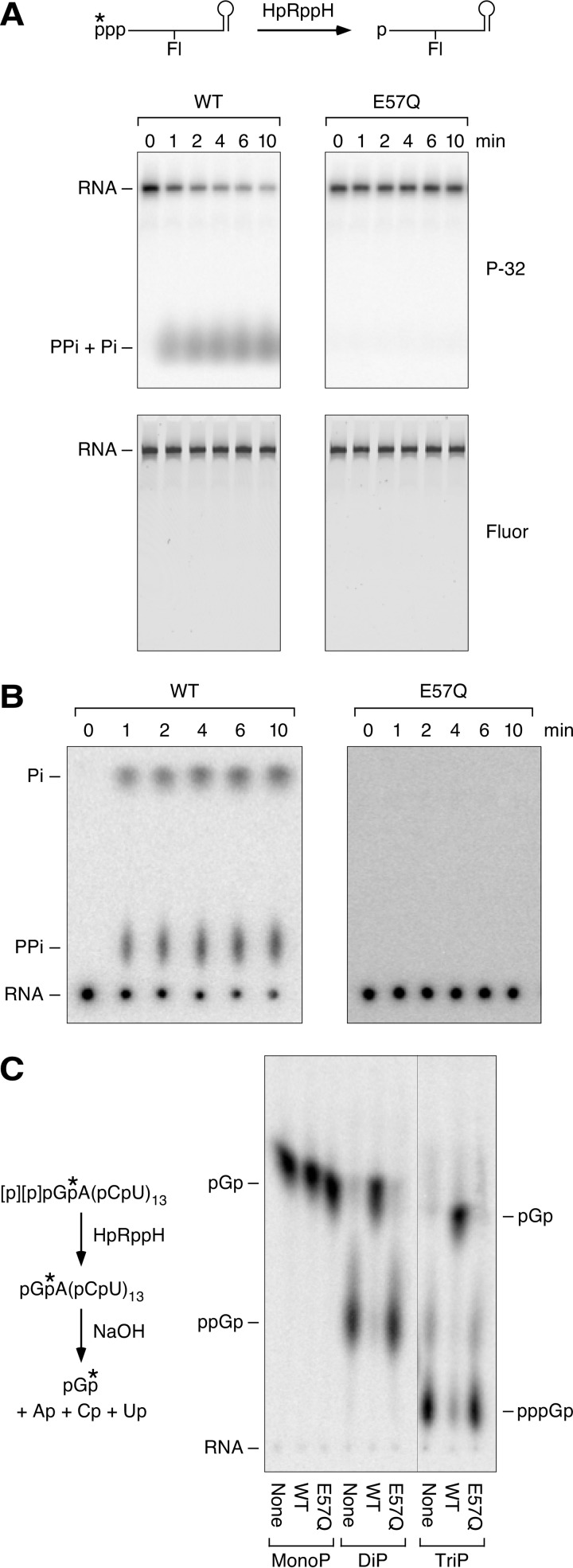

FIGURE 2.

RNA pyrophosphohydrolase activity of purified HpRppH. A and B, release of pyrophosphate and orthophosphate from the 5′ end of triphosphorylated RNA by HpRppH. Triphosphorylated rpsT P1 RNA (13) bearing a 5′-terminal γ-32P label (*) and an internal fluorescein label (Fl) (A, top) was treated with purified HpRppH or HpRppH-E57Q (75 nm), and reaction samples isolated at time intervals were analyzed by gel electrophoresis (with subsequent detection of radioactivity (P-32) and fluorescence (Fluor)) (A) or thin layer chromatography (with subsequent detection of radioactivity) (B). PPi, pyrophosphate; Pi, orthophosphate. C, conversion of triphosphorylated and diphosphorylated RNA to monophosphorylated RNA by HpRppH. Triphosphorylated (TriP), diphosphorylated (DiP), and monophosphorylated (MonoP) GA(CU)13 bearing a single 32P label (*) between the first and second nucleotides were treated with purified HpRppH or HpRppH-E57Q (75 nm), and the radiolabeled starting materials and reaction products were subjected to alkaline hydrolysis and analyzed by thin layer chromatography.

To determine whether HP1228 generates monophosphorylated RNA as the other reaction product, we prepared another RNA substrate, GA(CU)13, bearing a monophosphate, diphosphate, or triphosphate at the 5′ terminus and a single 32P label between the first and second nucleotide. After treatment with HP1228, the RNA reaction product was subjected to alkaline hydrolysis, and the 5′-terminal nucleotide was examined by thin layer chromatography and autoradiography (Fig. 2C). HP1228-catalyzed hydrolysis of both triphosphorylated and diphosphorylated GA(CU)13 generated monophosphorylated GA(CU)13, which was detected as radiolabeled pGp after alkaline hydrolysis, whereas the corresponding monophosphorylated substrate was not affected by this enzyme. As expected, none of the substrates reacted with catalytically inactive HP1228 bearing an E57Q substitution. We conclude that HP1228 functions in vitro as an RNA pyrophosphohydrolase that is able to convert triphosphorylated and diphosphorylated substrates to monophosphorylated products. These findings and the homology of HP1228 to EcRppH prompted us to rename it H. pylori RppH (HpRppH).

Requirement for Unpaired Nucleotides at the 5′ Terminus

To determine the minimum number of unpaired 5′-terminal nucleotides required for the reaction of RNA with HpRppH, we compared the reactivity of a set of structurally unambiguous substrates previously used to examine the specificity of EcRppH and B. subtilis RppH (BsRppH) (Fig. 3) (16, 19). A8, the prototype of these RNA substrates, comprised an 8-nucleotide single-stranded segment followed by two stem-loop structures, the first of which contained the only uracil base in the entire molecule. Synthesized by in vitro transcription in the presence of [γ-32P]ATP and fluorescein-12-UTP, A8 contained a γ radiolabel within the 5′-terminal triphosphate and a single fluorescein label at the top of the first stem-loop. For use as an internal standard, we also prepared doubly labeled A8XL RNA, which differed from A8 only in having an additional stem-loop at the 3′ end.

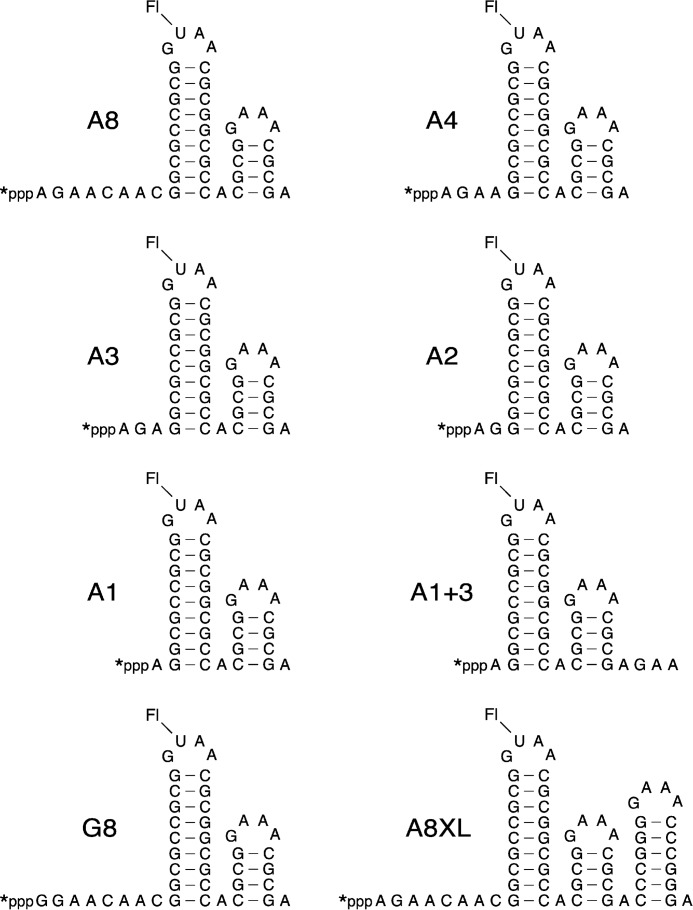

FIGURE 3.

HpRppH substrates. The sequence and expected secondary structure of A8, A4, A3, A2, A1, A1+3, G8, and A8XL RNA are shown. Each bore a 5′-terminal triphosphate (ppp), a γ-32P radiolabel (*) at the 5′ end, and a fluorescein label (Fl) at the top of the first stem-loop. In each RNA name, the letter indicates the identity of the 5′-terminal nucleotide, and the numeral indicates the number of unpaired nucleotides at the 5′ end. Truncated derivatives of A8 (A4, A3, A2, and A1) lacked 4–7 nucleotides from the 3′ boundary of the 5′-terminal single-stranded segment. G8, G4, G3, G2, G1, and G0 were identical to their A-series counterparts except for the presence of G instead of A at the 5′ end. A1+3 was the same as A1 except for three additional nucleotides at the 3′ end.

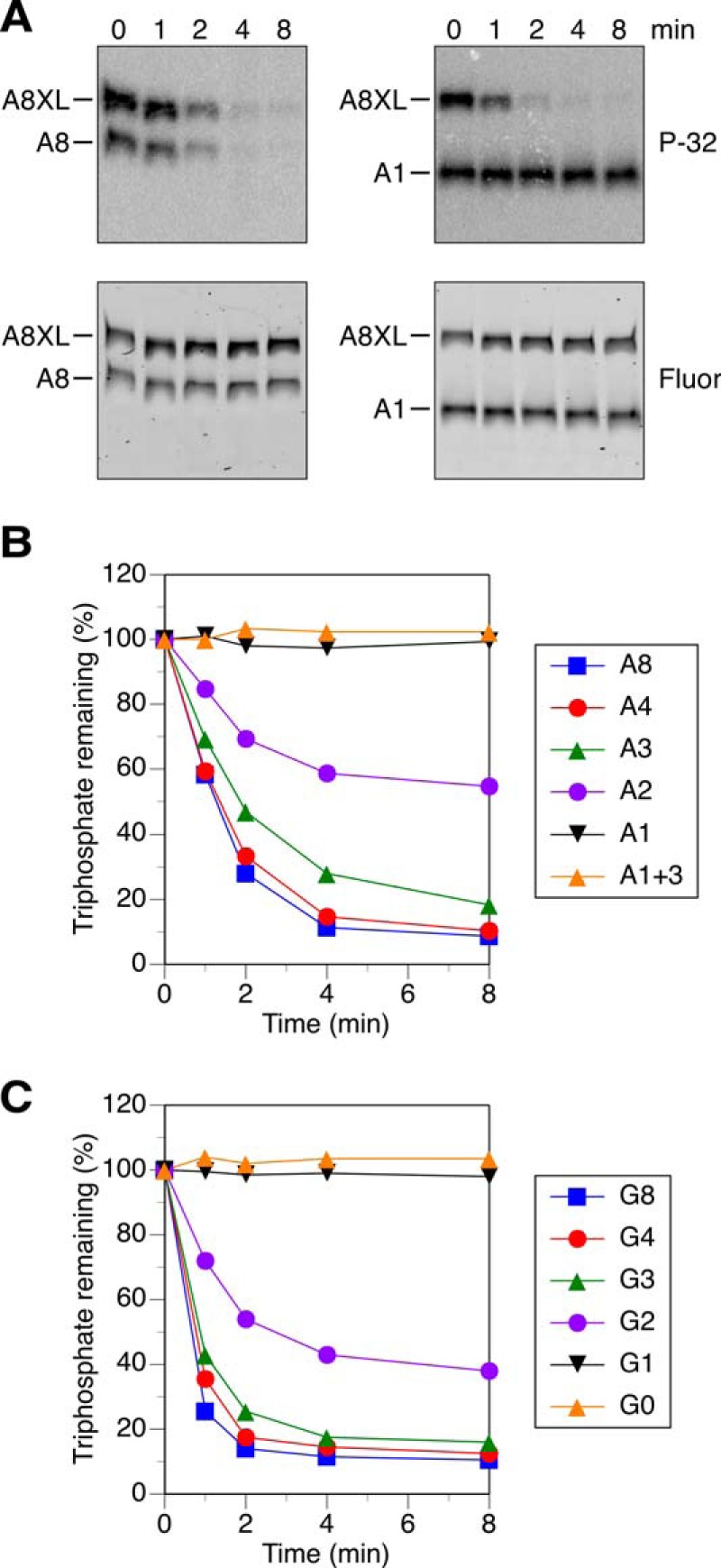

Conversion of these triphosphorylated RNAs to monophosphorylated products was monitored by combining equal amounts of each with HpRppH, quenching reaction samples periodically, and separating the reaction products by gel electrophoresis (Fig. 4A). The extent of reaction at each time point was then determined for both A8 and A8XL by comparing the radioactivity of the corresponding gel band with its fluorescence intensity. As anticipated, the reaction rates of these two substrates were very similar.

FIGURE 4.

Effect of the length of the 5′-terminal single-stranded segment on reactivity with HpRppH in vitro. A, representative gel images. In vitro transcribed A8 and A1 bearing a γ-32P radiolabel and an internal fluorescein label were mixed with labeled A8XL and treated with purified HpRppH (16 nm), and the radioactivity (P-32) and fluorescence (Fluor) of each RNA were monitored as a function of time by gel electrophoresis. B and C, graphs. HpRppH-catalyzed phosphate removal from A8, A4, A3, A2, A1, and A1+3 or from G8, G4, G3, G2, G1, and G0 was monitored as in A and quantified by normalizing the radioactivity remaining in each RNA to the corresponding fluorescence intensity. Each time point is the average of two or more independent measurements. Error bars have been omitted to improve the legibility of the graph; instead, the S.D. of each measurement is reported in supplemental Table S1.

The single-stranded segment at the 5′ end of A8 was then shortened from 8 to 4, 3, 2, or 1 nucleotide by removing nucleotides from its 3′ boundary to create A4, A3, A2, and A1 (Fig. 3), and the reactivity of these RNAs toward HpRppH was compared in the presence of A8XL. A4 and A3 were almost as reactive as A8, whereas A2 was significantly less reactive, and A1 was completely unreactive (Fig. 4, A and B). The addition of three unpaired nucleotides to the 3′ end of A1 (A1+3) (Fig. 3) did not improve its reactivity (Fig. 4B), providing evidence that its resistance to pyrophosphate removal by HpRppH resulted from an insufficient number of unpaired nucleotides at the 5′ end and not merely from its shorter overall length. The effect of the number of unpaired 5′-terminal nucleotides was similar for a related set of RNA substrates in which the first nucleotide was changed from A to G (Fig. 4C). These findings demonstrate that HpRppH, like EcRppH and BsRppH (16, 19), requires at least two unpaired nucleotides at the 5′ end of its substrates and prefers three or more.

Effect of 5′-Terminal RNA Sequence

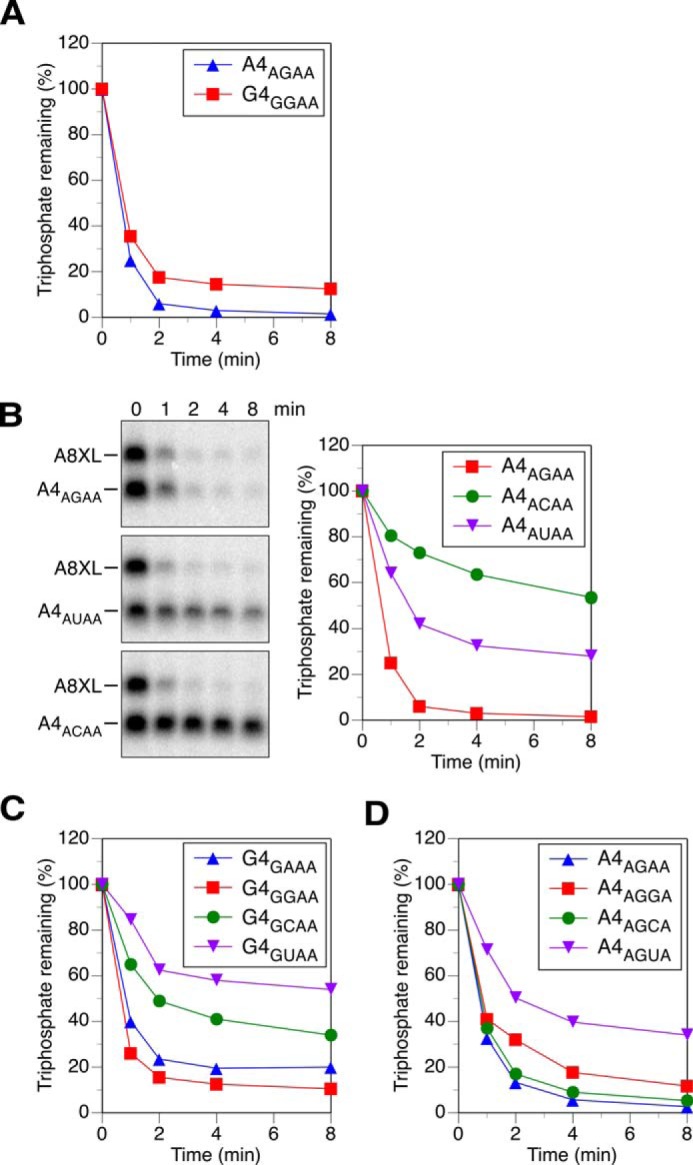

The requirement for unpaired nucleotides at the 5′ end of HpRppH substrates raised the possibility that this enzyme might also be affected by the identity of the nucleotides there. To determine whether HpRppH prefers substrates bearing certain 5′-terminal sequences, we replaced individual nucleotides in A4 (hereafter referred to as A4AGAA to reveal both the identity of the 5′-terminal nucleotide and the sequence of unpaired nucleotides at the 5′ end) and examined the effect of these substitutions on reactivity. A substitution mutant (G4GGAA) in which the first nucleotide was changed from A to G (a majority of primary transcripts in bacteria begin with either of these two nucleotides (33)) was only slightly less reactive than A4AGAA (Fig. 5A). By contrast, pyrimidine substitutions at the second position significantly impaired reactivity. In particular, replacing the G at position 2 of either A4AGAA or G4GGAA with C or U (to create A4ACAA, A4AUAA, G4GCAA, or G4GUAA) slowed the reaction considerably but did not block it, whereas substituting A at that position in G4GGAA (to create G4GAAA) had only a modest inhibitory effect (Fig. 5, B and C; synthesis of A4AAAA was not successful). Altering the third nucleotide had a substantial impact only when U was introduced there, as A4AGGA and A4AGCA were as reactive as A4AGAA, whereas A4AGUA was less reactive (Fig. 5D). Overall, the 5′-terminal sequence specificity of HpRppH closely resembles that of its ortholog EcRppH in that both enzymes are rather promiscuous but prefer a purine at position 2, unlike BsRppH, which strictly requires G at position 2 (16, 19).

FIGURE 5.

Effect of the sequence of the first three RNA nucleotides on reactivity with HpRppH in vitro. A, position 1. The reactivity of A4AGAA and G4GGAA was compared as in Fig. 4. The subscript in each RNA name indicates the sequence of the four unpaired nucleotides at the 5′ end. Consequently, A4AGAA was equivalent to A4. B and C, position 2. The reactivity of A4AGAA, A4ACAA, and A4AUAA and of G4GGAA, G4GAAA, G4GCAA, and G4GUAA was compared. Although both radioactivity and fluorescence were measured, only the former is shown in the gel images. To avoid modifying the second nucleotide, A4AUAA and G4GUAA were not labeled with fluorescein; instead, the fluorescence of fluorescein-labeled A8XL was used to normalize the data from each time point. The synthesis of A4AAAA was not successful. D, position 3. The reactivity of A4AGAA, A4AGGA, A4AGCA, and A4AGUA was compared. To avoid modifying the third nucleotide, A4AGUA was not labeled with fluorescein. The S.D. of each measurement is reported in supplemental Table S1.

Inactivity of HP0507 as an RNA Pyrophosphohydrolase

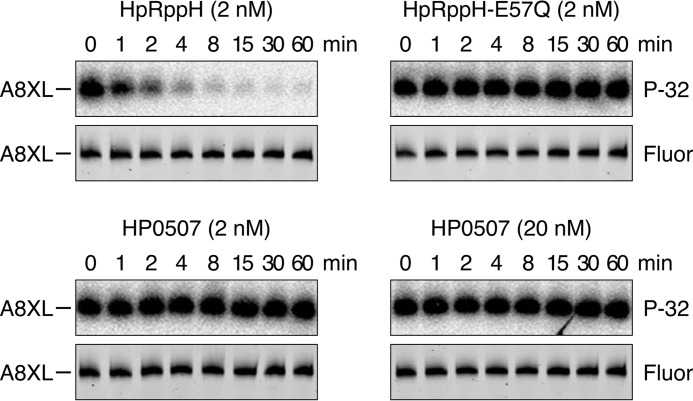

In addition to HpRppH (HP1228), which contains an almost perfect Nudix motif (GX5EX7REUXEEXGT; mismatch underlined), the genome of H. pylori encodes another protein, HP0507, that contains a partial Nudix motif (LX5KX7EEAXEEXGY; mismatches underlined). HP0507 is 11% identical in overall sequence to EcRppH and has been implicated in virulence (30). To determine whether HP0507 has RNA pyrophosphohydrolase activity, we tested whether it can remove a γ radiolabel from triphosphorylated A8XL. Whereas 2 nm HpRppH released almost 90% of the radiolabel from this substrate within 4 min, no reactivity was observed for HP0507, even when 10-fold more enzyme (20 nm) was added and the reaction was monitored for 60 min (Fig. 6). Assuming the structural integrity of the recombinant protein, these findings indicate that HP0507 either is not an RNA pyrophosphohydrolase or has a strict RNA substrate specificity that prevents it from acting on A8XL.

FIGURE 6.

Test of the putative Nudix hydrolase HP0507 for RNA pyrophosphohydrolase activity. In vitro transcribed A8XL RNA radiolabeled at the 5′-terminal γ-phosphate and internally labeled with fluorescein (see Fig. 3) was treated with purified HpRppH (2 nm final concentration), catalytically inactive HpRppH-E57Q (2 nm), or HP0507 (2 or 20 nm), and reaction samples quenched at time intervals were subjected to gel electrophoresis. Hydrolytic release of the 5′-terminal radiolabel was detected by autoradiography (P-32), and the integrity of the remainder of the RNA molecule was monitored by fluorescence (Fluor).

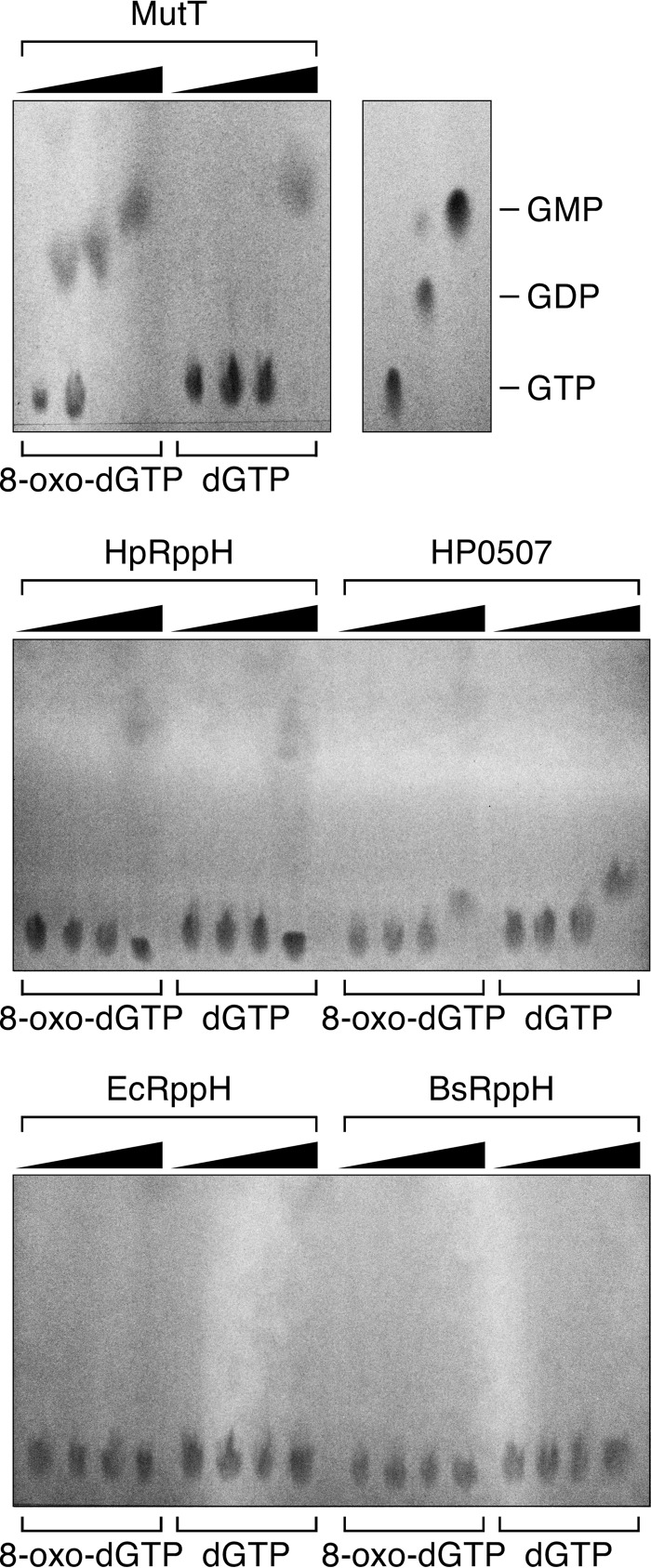

Test for 8-Oxo-dGTPase Activity

Most bacterial species contain multiple Nudix hydrolases, each of which has a distinct function (17). Because HpRppH is the only H. pylori protein with a bona fide Nudix motif, we wondered whether it might have more than one function. Therefore, we tested whether it possesses another well known Nudix hydrolase activity: the ability of MutT-like proteins to protect cells from incorporating the mutagenic nucleotide 8-oxo-dGTP during DNA replication by selectively converting it to 8-oxo-dGMP (34). 8-Oxo-dGTP or dGTP was mixed with purified E. coli MutT (positive control), HpRppH, HP0507, EcRppH, or BsRppH. After 60 min, the starting material and products were separated by thin layer chromatography on fluorescent PEI-cellulose plates. As expected, MutT exhibited substantial 8-oxo-dGTPase activity at an enzyme concentration of just 1 nm and completely hydrolyzed the substrate at a concentration of 10 nm; only at a much higher enzyme concentration (100 nm) was it able to hydrolyze dGTP (Fig. 7). By contrast, neither HpRppH nor HP0507 detectably hydrolyzed 8-oxo-dGTP below an enzyme concentration of 100 nm, and neither had a preference for that substrate over dGTP. EcRppH and BsRppH were completely unable to hydrolyze either substrate. These results suggest that neither HpRppH nor HP0507 functions as a selective 8-oxo-dGTPase in H. pylori. This conclusion is consistent with a previous report that the frequency of spontaneous mutation is the same in wild-type and ΔrppH strains of H. pylori (29).

FIGURE 7.

Test of HpRppH and HP0507 for selective 8-oxo-dGTPase activity. 8-Oxo-dGTP or dGTP (50 μm) was treated for 60 min with various concentrations of purified E. coli MutT, HpRppH, HP0507, EcRppH, or BsRppH (0, 1, 10, or 100 nm), and the reaction products were examined by thin layer chromatography on PEI-cellulose. GTP, GDP, and GMP served as mobility standards. Whereas MutT hydrolyzed 8-oxo-dGTP much faster than dGTP, the other enzymes either did not hydrolyze 8-oxo-dGTP detectably (EcRppH, BsRppH) or did so slowly and no faster than they hydrolyzed dGTP (HpRppH, HP0507).

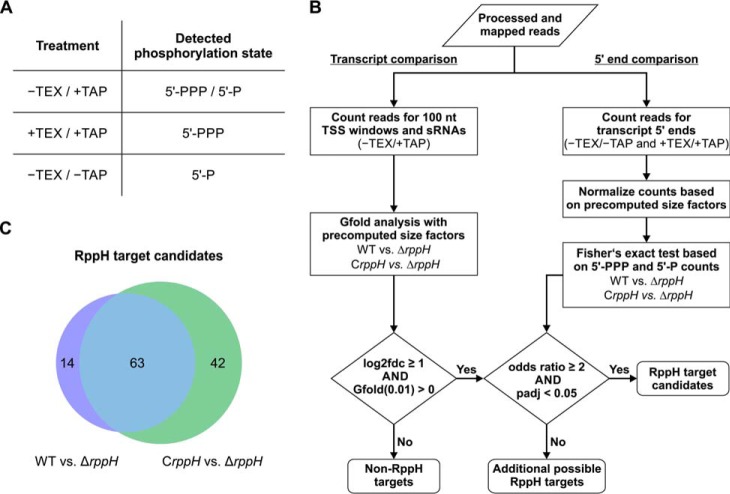

Global Identification of RppH Targets by Differential RNA-seq4

To investigate the global role of HpRppH in converting 5′-triphosphates to monophosphates in H. pylori, we used a variant of differential RNA-seq (dRNA-seq) (35, 36) to compare the concentration and 5′-phosphorylation state of transcripts in isogenic H. pylori strains containing or lacking the rppH gene. For this purpose, we constructed two derivatives of the wild-type H. pylori strain 26695: an rppH deletion mutant (ΔrppH) and an rppH complementation strain (CrppH) bearing an ectopic copy of the rppH gene. The ΔrppH strain was generated by a non-polar chromosomal substitution in which the rppH gene of wild-type (WT) cells was replaced with a kanamycin resistance cassette (37). The CrppH strain was then constructed by complementing this deletion with an ectopic copy of the H. pylori rppH gene under the control of its own promoter (35), which was introduced at an unrelated locus (rdxA) previously used as a site for integrating genes into the H. pylori chromosome (38–41).

These isogenic H. pylori strains were grown to log phase, and total RNA isolated from each was used to generate three libraries specific for transcripts bearing 1) a 5′-triphosphate, 2) a 5′-monophosphate, or 3) either a 5′-triphosphate or a 5′-monophosphate (Fig. 8A). This was accomplished by differential treatment of total cellular RNA with Terminator 5′-phosphate-dependent exonuclease (TEX) and tobacco acid pyrophosphatase (TAP) (35, 36, 42). The 5′-exonuclease activity of TEX digests 5′-monophosphorylated (5′-P) RNAs but leaves triphosphorylated (5′-PPP) transcripts intact. Subsequent treatment of the latter set of transcripts with TAP generates monophosphorylated 5′ ends to which an RNA oligonucleotide can be ligated, thereby enabling cDNA synthesis. By contrast, treatment with TAP alone enables cDNA synthesis from both triphosphorylated and monophosphorylated RNAs, whereas treatment with neither enzyme allows cDNA synthesis only from cellular RNAs that are already monophosphorylated. Therefore, to identify RNAs in each category, we generated cDNA libraries specific for transcripts with a 5′-triphosphate (+TEX/+TAP), a 5′-monophosphate (−TEX/−TAP), or both (−TEX/+TAP) from all three strains (Fig. 8A) and subjected them to Illumina sequencing. In total, between 4.1 and 5.8 million reads were sequenced for each of the cDNA libraries, of which between 96.8 and 98.5% could be mapped to the H. pylori 26695 genome (Table 1).

FIGURE 8.

Differential RNA-seq analysis of RNA 5′ ends in H. pylori cells containing or lacking HpRppH. A, combinations of TEX/TAP treatments used to enrich for 5′-PPP transcripts, 5′-P transcripts, or both (5′-PPP/5′-P). B, computational pipeline used to identify RppH target candidates. To pass muster, a ≥2-fold increase in both the RNA concentration (log2fdc ≥ 1) and the ratio of 5′-PPP to 5′-P ends (odds ratio ≥ 2) was required in ΔrppH cells versus WT and CrppH cells. Precomputed size factors were based on the number of mapped reads for each library. C, Venn diagram of RppH target candidates identified in ΔrppH cells versus WT or CrppH cells.

TABLE 1.

Mapping statistics for the H. pylori 26695 Illumina libraries

This table summarizes the total number of sequenced cDNA reads after quality trimming, as well as the number of mapped and uniquely mapped reads for each sequencing library. Percentage values are relative to the number of reads that are >11 nt in length after poly(A) trimming.

| Library | Total number of reads after quality trimming | Number of reads long enough after poly(A) trimming | Mapped reads | Percentage of mapped reads | Uniquely mapped reads | Percentage of uniquely mapped reads |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HP26695_WT_+TEX_+TAP | 4,105,444 | 2,904,136 | 2,855,756 | 98.3 | 1,776,256 | 61.2 |

| HP26695_WT_−TEX_+TAP | 4,709,180 | 4,393,218 | 4,303,527 | 98.0 | 2,191,371 | 49.9 |

| HP26695_WT_−TEX_−TAP | 4,541,183 | 3,735,492 | 3,637,516 | 97.4 | 1,801,667 | 48.2 |

| HP26695_drppH_+TEX_+TAP | 4,322,165 | 3,691,261 | 3,637,538 | 98.5 | 2,685,123 | 72.7 |

| HP26695_drppH_–TEX_+TAP | 5,687,933 | 5,367,180 | 5,285,689 | 98.5 | 2,913,153 | 54.3 |

| HP26695_drppH_−TEX_−TAP | 5,171,576 | 4,086,347 | 3,994,970 | 97.8 | 2,034,955 | 49.8 |

| HP26695_CrppH_+TEX_+TAP | 5,260,512 | 4,380,242 | 4,309,747 | 98.4 | 2,396,496 | 54.7 |

| HP26695_CrppH_−TEX_+TAP | 4,676,932 | 4,358,626 | 4,266,490 | 97.9 | 2,004,928 | 46.0 |

| HP26695_CrppH_−TEX_−TAP | 5,813,459 | 4,490,487 | 4,345,087 | 96.8 | 1,997,827 | 44.5 |

Because RppH triggers the degradation of its targets by converting 5′-terminal triphosphates to monophosphates, both the cellular concentration of those transcripts and the percentage of each that is 5′-triphosphorylated (rather than monophosphorylated) are expected to be higher in ΔrppH cells than in WT and CrppH cells. Hence, we screened for H. pylori transcripts that fulfill both of these criteria to identify RNAs that are directly and productively targeted by HpRppH. To detect changes in RNA concentration, the relative numbers of transcripts in the −TEX/+TAP libraries (5′-PPP and 5′-P) were calculated on the basis of cDNA counts for windows of up to 100 nt encompassing previously annotated transcription start sites (TSSs) of mRNAs and non-coding RNAs (42) as well as full-length annotations for sRNAs (35) and then compared among the three strains by using Gfold (43). In addition, to detect changes in 5′-phosphorylation, transcript levels in the +TEX/+TAP (5′-PPP) and −TEX/−TAP (5′-P) libraries were calculated for a region from 5 nt upstream to 4 nt downstream of each TSS and then compared for WT versus ΔrppH as well as CrppH versus ΔrppH by a one-sided Fisher's exact test. In total, 63 of 925 transcripts (53 mRNAs and 10 sRNAs) were found to be at least 2-fold more abundant (log2fdc ≥1 and Gfold (0.01) > 0) in ΔrppH cells versus both WT and CrppH cells and additionally to be enriched at least 2-fold for monophosphorylated versus triphosphorylated 5′ ends (5′-P/5′-PPP ratio) in WT and CrppH cells compared with the ΔrppH mutant (one-sided Fisher's exact test; odds ratio ≥2 and Benjamini-Hochberg adjusted p value <0.05) (Fig. 8, B and C), evidence that they may be RppH targets. These 63 transcripts are summarized in the first sheet of supplemental Table S2. The 53 up-regulated mRNAs included 52 primary TSSs and one secondary TSS associated with 52 distinct genes. An additional 119 possible targets whose concentration increased ≥2-fold in ΔrppH cells without a corresponding reduction in the percentage of monophosphorylated 5′ ends are listed in supplemental Table S3.

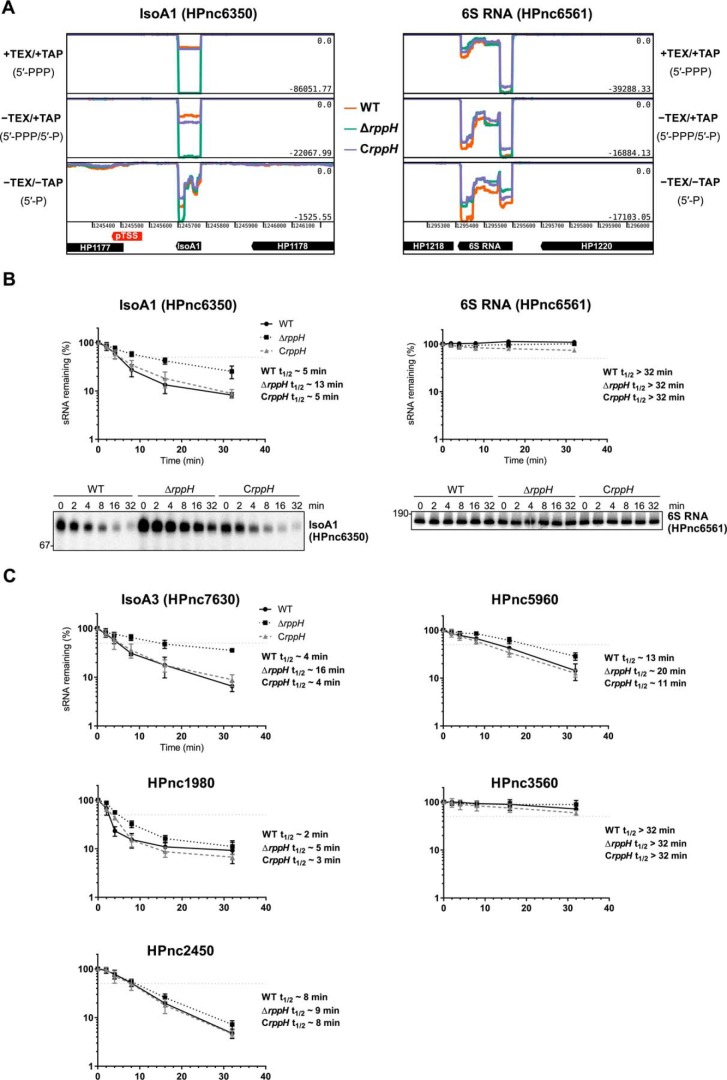

sRNAs Targeted by RppH

Among the apparent HpRppH targets that we detected is the sRNA IsoA1 (HPnc6350) (supplemental Table S2). As judged from the RNA-seq data, the concentration of triphosphorylated IsoA1 and its abundance relative to its monophosphorylated counterpart were substantially higher in ΔrppH cells than in WT and CrppH cells (Fig. 9A and supplemental Table S2). IsoA1 belongs to a group of six structurally related H. pylori sRNAs, IsoA1–6 (RNA inhibitor of small ORF family A), that are each ∼80 nt in length (35). They are transcribed antisense to the small ORFs aapA1–6 (antisense RNA-associated peptide family A), which encode homologous peptides 22–30 amino acids in length. In vitro, IsoA1 has been shown to strongly and selectively inhibit the translation of aapA1 mRNA (35). One other IsoA sRNA, IsoA3 (HPnc7630), as well as several additional sRNA candidates (including HPnc1980, HPnc3560, and HPnc7830) and potential cis-encoded antisense RNAs also appear to be targeted by HpRppH (supplemental Table S2). In contrast, a number of other sRNAs, such as the RNA polymerase inhibitor 6S RNA (HPnc6561, Fig. 9A) and HPnc2450 (supplemental Table S2), do not appear to be affected by HpRppH, indicating that this pyrophosphohydrolase targets sRNAs selectively.

FIGURE 9.

sRNA targets of HpRppH. A, screen shots of RNA-seq data for the HpRppH target IsoA1 sRNA (HPnc6350) and the non-target 6S RNA (HPnc6561) in WT, ΔrppH, and CrppH cells, as visualized by using Artemis (56). B, half-lives of IsoA1 sRNA (∼80 nt long) and 6S RNA (∼180 nt long) in H. pylori. RNA degradation was monitored by Northern blotting analysis of equal amounts of total RNA extracted from WT, ΔrppH, and CrppH cells at various times after the addition of rifampicin to log-phase cultures. Data from four biological replicates of each of the three strains were averaged, and half-lives (t½) were determined from the time at which 50% of the RNA remained (light gray dotted lines). Error bars, S.D. C, half-lives of additional sRNAs (HPnc7630, HPnc1980, HPnc5960, HPnc3560, and HPnc2450) in H. pylori, based on three biological replicates each.

To independently validate these findings, we examined the effect of HpRppH on the degradation rates of several of its putative sRNA targets. This was achieved by treating log-phase cultures of isogenic WT, ΔrppH, and CrppH strains of H. pylori with rifampicin to arrest transcription and unmask degradation. Total RNA was then extracted from the cells at time intervals, and equal amounts were analyzed by Northern blotting. The half-life of IsoA1 sRNA increased from ∼5 min in WT cells to ∼13 min in ΔrppH cells (Fig. 9B, left). Complementation of the ΔrppH mutation with an ectopic copy of the gene (CrppH) restored the original 5-min half-life. Several other sRNAs judged by dRNA-seq to be candidate RppH targets, such as IsoA3 (HPnc7630), HPnc1980, and HPnc5960, were also significantly stabilized (1.5–4-fold) in the ΔrppH strain, whereas the stability of the long-lived HPnc3560 transcript did not increase noticeably (Fig. 9C). No change in lifetime was observed for 6S sRNA (HPnc6561) (Fig. 9B, right) or HPnc2450 (Fig. 9C), which served as negative controls.

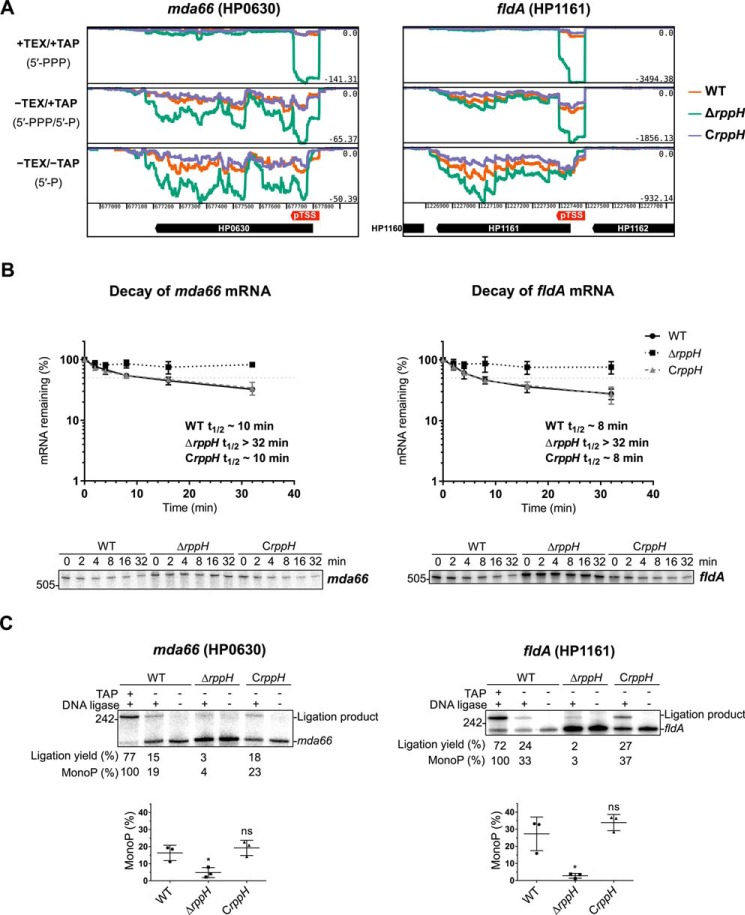

mRNAs Targeted by RppH

In addition to potential sRNA targets, we identified 52 potential mRNA targets of HpRppH by dRNA-seq. For example, the fldA (HP1161) and mda66 (HP0630) transcripts, encoding flavodoxin I (FldA) and an NADPH quinone reductase (MdaB), respectively, were more abundant and had a lower ratio of monophosphorylated to triphosphorylated 5′ ends in the ΔrppH mutant than in the WT and complemented strains (Fig. 10A). Other mRNAs that appeared to be targeted by HpRppH included those encoding cytochrome c553 (HP1227, encoded directly adjacent to HpRppH), cell binding factor 2 (HP0175), and outer membrane protein OMP18 (HP1125) (supplemental Table S2). Sensitivity to RppH was not significantly correlated with protein function, as defined by the PyloriGene database (44) (one-sided Fisher's exact test, calculated Benjamini-Hochberg adjusted p value >0.10 for every functional category; data not shown).

FIGURE 10.

mRNA targets of HpRppH. A, screen shots of RNA-seq data for the HpRppH targets mda66 mRNA (HP0630) and fldA mRNA (HP1161) in WT, ΔrppH, and CrppH cells, as visualized by using Artemis (56). B, half-lives of mda66 mRNA (∼621 nt long) and fldA mRNA (∼548 nt long) in H. pylori. RNA degradation was monitored by Northern blotting analysis of equal amounts of total RNA extracted from WT, ΔrppH, and CrppH cells at various times after the addition of rifampicin to log-phase cultures. Data from three biological replicates of each of the three strains were averaged, and half-lives (t½) were determined from the time at which 50% of the mRNA remained (light gray dotted lines). C, phosphorylation state of mda66 and fldA mRNA in H. pylori. Total RNA extracted from WT, ΔrppH, and CrppH cells was examined by PABLO analysis to determine the 5′-phosphorylation state of the transcripts in vivo. Top, representative PABLO assays. RNA samples that had first been treated in vitro with TAP were analyzed in parallel so that the ligation yields of fully monophosphorylated transcripts could be used as correction factors for calculating the percentage of mda66 and fldA that was monophosphorylated. Bottom, scatter plots showing the average of three independent PABLO experiments. Error bars, S.D. Student's t test was used for statistical comparison of the ΔrppH and CrppH data with the WT data. *, statistically significant difference (p ≤ 0.05); ns, not significant (p > 0.05).

To corroborate the influence of HpRppH on two of its mRNA targets, we examined its effect on the lifetime and 5′-phosphorylation state of the fldA and mda66 transcripts. First, we compared the half-lives of these mRNAs in cells containing or lacking RppH by using Northern blot analysis to monitor their disappearance after transcription inhibition with rifampicin. The half-lives of these transcripts increased from 7 min (flaA) or 10 min (mda66) in WT cells to >32 min in ΔrppH cells and returned to their original values in CrppH cells (Fig. 10B).

Next, we investigated the effect of RppH on the 5′-terminal phosphorylation state of these mRNAs by PABLO (phosphorylation assay by ligation of oligonucleotides), a splinted ligation assay specific for monophosphorylated 5′ ends (45, 46). This method is based on the ability of T4 DNA ligase to join a DNA oligonucleotide to a monophosphorylated RNA, but not its triphosphorylated counterpart, when their ends are juxtaposed by annealing them to a bridging oligonucleotide complementary to both. The percentage of the transcript that is monophosphorylated can then be determined by using denaturing gel electrophoresis and blotting to resolve the ligation product from its unligated counterpart and comparing the ligation yield with that of a fully monophosphorylated control (47). In this manner, we determined that a significant fraction of both fldA mRNA (27%) and mda66 mRNA (16%) is monophosphorylated at steady state in WT cells and that this percentage declines to only 3–5% in ΔrppH cells (Fig. 10C). The percentage of these transcripts that was monophosphorylated was restored to normal by complementation of the genetic defect. Together, these findings confirm that fldA and mda66 mRNA are direct targets of RppH and are degraded in H. pylori by an RppH-dependent mechanism.

Discussion

In bacteria, RNA degradation typically commences by either of two mechanisms: 1) direct access of a ribonuclease to cleavage sites within transcripts or 2) 5′-end-dependent access in which RNA cleavage by a ribonuclease is facilitated by prior conversion of the 5′-terminal triphosphate to a monophosphate by an RNA pyrophosphohydrolase (3). Here we have identified the Nudix protein HP1228 as an RNA pyrophosphohydrolase important for RNA degradation in H. pylori, characterized its biochemical activity and substrate specificity in vitro, and identified several of its mRNA and sRNA targets in vivo by employing a global strategy based on high-throughput sequencing. In view of these properties and the homology of HP1228 to E. coli RppH (EcRppH), we have renamed it HpRppH. Our findings suggest an important role for RppH in governing gene expression not only in H. pylori but also in other pathogenic Epsilonproteobacteria, where orthologs of this enzyme are ubiquitous.

Using in vitro assays, we have demonstrated that HpRppH converts triphosphorylated RNA 5′ ends to monophosphorylated ends while yielding a mixture of pyrophosphate and orthophosphate as by-products. The same two by-products are generated by EcRppH, albeit in a ratio that is more biased toward pyrophosphate (13), whereas BsRppH produces only orthophosphate (11), presumably by removing the γ- and β-phosphates consecutively. One other H. pylori protein, HP0507, may have a fold resembling a Nudix domain, as it contains a partial Nudix motif with matches at 4 of 9 positions. This protein has been implicated in H. pylori virulence (30), and orthologs appear to be present in other Epsilonproteobacteria and in E. coli. However, even at a high concentration, HP0507 exhibited no detectable RNA pyrophosphohydrolase activity when purified and assayed in vitro.

Like EcRppH (16) and BsRppH (19), HpRppH requires at least two unpaired nucleotides at the 5′ end of its substrates and prefers three or more. The purified enzyme is rather promiscuous with respect to the identity of those 5′-terminal nucleotides, although it has a slight preference for A over G at the first position and for a purine over a pyrimidine at the second position, properties shared by EcRppH (16) but not BsRppH (19), which strictly requires a G at the second position. The difference in specificity between the proteobacterial enzymes and BsRppH is explained by dissimilarities in the amino acid residues that line the pocket where the second nucleotide binds to each of these proteins (16, 28, 31), residues that are almost identical in HpRppH (Arg-30, Ala-36, Val-135, Phe-137, Lys-138) and EcRppH (Arg-27, Ser-32, Val-137, Phe-139, Lys-140) but very different in BsRppH (Asp-6, Tyr-86, Val-88, Ile-95, Lys-97, Phe-137, Ile-138, and Asp-141). Among these amino acids, the sole difference between the two proteobacterial enzymes is a residue (Ala-36 in HpRppH, Ser-32 in EcRppH) that contacts the Watson-Crick edge of the second nucleobase of the RNA ligand in X-ray crystal structures of EcRppH and contributes to the promiscuity of that ortholog (16, 31). The similarity of the substrate preferences of HpRppH and EcRppH despite their overall sequence divergence (34% identity) suggests that the many other proteobacterial and plant orthologs of these two enzymes are likely to share these properties.

To identify transcripts targeted by HpRppH in H. pylori, we employed a global dRNA-seq strategy in which three distinct enzymatic treatments were used to selectively enrich RNAs bearing a 5′-triphosphate and/or a 5′-monophosphate. By examining the effect of an rppH deletion on the number of 5′ ends that were triphosphorylated or monophosphorylated in H. pylori, we identified 53 mRNAs and 10 sRNAs whose degradation appears to be triggered by this enzyme (supplemental Table S2). Several of them were further validated by half-life measurements and PABLO analysis. To be classified as candidate RppH targets, transcripts had to fulfill two criteria in ΔrppH cells versus WT and CrppH cells: 1) a ≥2-fold increase in their cellular concentration and 2) a ≥50% decline in the ratio of monophosphorylated to triphosphorylated 5′ ends. These strict selection criteria were chosen to maximize the likelihood that only transcripts directly and productively targeted by HpRppH would be identified. Nevertheless, because of statistical uncertainty, the ≥2-fold effect used as a threshold, and the fact that only one growth condition was tested, it seems probable that HpRppH triggers the degradation of many additional H. pylori transcripts besides those identified here. Potential RppH targets whose concentration increased ≥2-fold in ΔrppH cells but whose phosphorylation state did not change sufficiently to satisfy the other requirement are listed in supplemental Table S3. For many of these 119 additional RNAs, the number of monophosphorylated 5′ ends detected in the −TEX/−TAP libraries may have been too low to be accurately quantified due to the susceptibility of such intermediates to rapid degradation.

HpRppH seems to target only a subset of H. pylori transcripts, as not all of the 925 5′ ends that were examined (second sheet of supplemental Table S2) satisfied the screening criteria. Therefore, although it is theoretically possible that this bacterial species contains a second, non-redundant RNA pyrophosphohydrolase, as has been proposed for B. subtilis and Staphylococcus aureus (19, 48), it is likely that a large number of H. pylori RNAs undergo rapid degradation by pathways that do not require prior conversion of the 5′-triphosphate to a monophosphate. Consistent with the existence of RppH-independent RNA decay pathways is the fact that rppH is not an essential gene in H. pylori, although its deletion reduces the growth rate of H. pylori 26695 by about one-third (data not shown).

The preference of purified HpRppH for a purine at the second position of its substrates is not reflected in the sequences at the 5′ end of the 63 candidate HpRppH targets identified in vivo, where there is a modest bias in favor of U at the expense of A and C at the second position (A:G:C:U (targeted transcripts/all transcripts) = 0.13/0.24 : 0.05/0.07 : 0.13/0.19 : 0.70/0.50 at position 2). For example, among the targets that were validated individually, IsoA1 and IsoA3 both have a purine (A) at position 2, whereas mda66, fldA, HPnc1980, and HPnc5960 each have a pyrimidine there (U, C, U, or U, respectively). This finding suggests that H. pylori transcripts degraded by a 5′-end-dependent mechanism have evolved not to maximize the RppH reaction rate but rather to allow sequence-dependent variations in that rate to contribute to differences in RNA lifetimes.

The fate of the monophosphorylated decay intermediates generated by RppH depends on the organism in which they are produced, as different bacterial species often have distinct ribonucleolytic arsenals (3). For example, E. coli and B. subtilis not only contain dissimilar RNA pyrophosphohydrolases but also utilize different sets of ribonucleases to degrade RNA. In E. coli, monophosphorylated decay intermediates are rapidly degraded by RNase E, a 5′-monophosphate-assisted endonuclease, whereas in B. subtilis they are degraded by RNase J, a 5′-monophosphate-dependent 5′-exonuclease (10, 11, 13, 49). H. pylori represents an interesting amalgam of those two species. Like E. coli, it is a proteobacterium, and it therefore contains an ortholog of EcRppH. However, as an epsilonproteobacterium, other aspects of RNA turnover in H. pylori more closely resemble B. subtilis, as it lacks RNase E and instead is thought to utilize two other ribonucleases, RNase J and the endonuclease RNase Y, to degrade RNA (5, 8, 9). As a result, it is likely that the monophosphorylated decay intermediates generated by HpRppH are degraded exonucleolytically by RNase J, probably with help from RhpA, a DEXD-box RNA helicase with which RNase J forms a complex in H. pylori (8). Indeed, >80% of the likely and possible RppH targets that were previously examined for RNase J sensitivity (5, 8, 9) appear to be degraded by an RNase J-dependent mechanism (supplemental Tables S2 and S3). RNase J is also capable of functioning as an endonuclease (8), but this activity is not dependent on the 5′-phosphorylation state of RNA (11) and therefore is unlikely to contribute significantly to the degradation of transcripts productively targeted by RppH.

Previous studies have reported that HpRppH is constitutively expressed in H. pylori at various stages of growth and during stress (29) and that H. pylori ΔrppH mutants have a diminished capacity to invade gastric epithelial adenocarcinoma cells (32) and to survive hydrogen peroxide exposure (29). The latter two phenotypes probably are consequences of altered patterns of gene expression resulting from the increased stability of RNAs ordinarily targeted by RppH, and they illustrate the physiological importance of 5′-end deprotection by this enzyme. The fact that HpRppH is the only known H. pylori protein with a bona fide Nudix motif suggests that, of all of the metabolic functions of bacterial Nudix hydrolases (17), this may well be the most important.

Experimental Procedures

Protein Structure Prediction

A detailed structural model of HpRppH was generated on the basis of sequence homology to EcRppH by using a high-resolution X-ray crystal structure of EcRppH bound to an oligonucleotide ligand and two Mg2+ ions (Protein Data Bank code 4S2X) (31) as a template. The calculations were performed with SWISS-MODEL software (50) on the ExPASy bioinformatics website. PyMOL (51) was utilized to prepare figures from the resulting atomic coordinates.

In Vitro Assays of RNA Pyrophosphohydrolase Activity and Specificity

HpRppH (HP1228), HpRppH-E57Q, and HP0507, each bearing an amino-terminal hexahistidine tag, were produced in E. coli, purified by affinity chromatography on TALON beads (Clontech), and assayed for RNA pyrophosphohydrolase activity as described previously (13). Triphosphorylated rpsT P1 RNA bearing a 5′-terminal γ-32P label and an internal fluorescein label and triphosphorylated, diphosphorylated, and monophosphorylated GA(CU)13 bearing a single 32P label between the first and second nucleotide were synthesized by in vitro transcription (13) and used as substrates in these assays. The specificity of HpRppH was examined as described previously with doubly labeled substrates (γ-32P and fluorescein) prepared by in vitro transcription, except that the assays of substrate reactivity were performed in solutions containing 1 mm MgCl2 and 16 nm HpRppH (19). Oligonucleotides and plasmids used to generate the DNA templates used for in vitro transcription have been described previously (13, 19, 45).

In Vitro Assays of 8-Oxo-dGTPase Activity

8-Oxo-dGTP or dGTP (50 μm) was combined with various concentrations of purified hexahistidine-tagged HpRppH, HP0507, E. coli MutT, E. coli RppH, or B. subtilis RppH (0, 1, 10, or 100 nm) in 500 μl of a buffer containing 5 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 1 mm MgCl2, and 1 mm dithiothreitol. After 60 min at 37 °C, the reactions were quenched with EDTA (2 mm final concentration) and then concentrated to 5 μl by evaporation. The reaction products were separated by thin layer chromatography on fluorescent PEI-cellulose plates and visualized by irradiating the plates with ultraviolet light.

H. pylori Growth Conditions

H. pylori strains were grown on GC-agar (Oxoid) plates supplemented with 10% (v/v) donor horse serum (Biochrom AG), 1% (v/v) vitamin mix, 10 μg/ml vancomycin, 5 μg/ml trimethoprim, and 1 μg/ml nystatin. For transformant selection and growth of mutant strains, 20 μg/ml kanamycin or 16 μg/ml chloramphenicol were added. For liquid cultures, 10 or 50 ml of brain heart infusion (BHI) medium (BD Biosciences) supplemented with 10% (v/v) FBS (Biochrom AG) and 10 μg/ml vancomycin, 5 μg/ml trimethoprim, and 1 μg/ml nystatin were inoculated with H. pylori from a plate to a final A600 of 0.02–0.05 and grown under agitation at 140 rpm in 25- or 75-cm3 cell culture flasks (PAA). Bacteria were grown at 37 °C in a HERAcell 150i incubator (Thermo Scientific) in a microaerophilic environment (10% CO2, 5% O2, and 85% N2). E. coli strains were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium supplemented with 100 μg/ml ampicillin, 20 μg/ml chloramphenicol, and/or 20 μg/ml kanamycin if applicable. Details about the generation of H. pylori mutant strains are provided below.

Construction of H. pylori Mutant Strains

All mutant strains were generated by natural transformation and homologous recombination of PCR-amplified constructs carrying either the aphA-3 kanamycin (37) or the catGC chloramphenicol resistance cassette (52) flanked by ∼500-bp regions of homology upstream and downstream of the respective genomic locus, as described previously. Briefly, H. pylori, grown from frozen stocks until passage two, was streaked in small circles on a fresh plate and grown for 6–8 h at 37 °C under microaerophilic conditions. For transformation, 0.5–1.0 μg of purified PCR product was added to the cells. After incubation for 14–16 h at 37 °C, cells were restreaked on selective plates containing the indicated antibiotics. The genotypes of mutants were verified by PCR amplification and sequencing of genomic DNA isolated using the NucleoSpin plasmid kit (Macherey-Nagel, Bethlehem, PA). Table 2 lists all oligonucleotides used for cloning.

TABLE 2.

DNA oligonucleotides used in this study

| Name | DNA sequences (5′–3′) | Description |

|---|---|---|

| CSO-0017 | GTTTTTTCTAGAGATCAGCCTGCCTTTAGG | Cloning of H. pylori 26695 rppH complementation |

| CSO-0018 | GTTTTTCTCGAGCTTAGCGCTTAATGAAACGC | Cloning of H. pylori 26695 rppH complementation |

| CSO-0033 | GCATTTGAGCAAAAGAGGG | Verification of H. pylori 26695 rppH complementation |

| CSO-0034 | GGCAAATCTTTAACCCTTTTG | Verification of H. pylori 26695 rppH complementation |

| CSO-0121 | ACTTGTAATTGTATCATTTTAAGATCATT | Deletion of H. pylori 26695 rppH |

| CSO-0122 | CTCCTAGTTAGTCACCCGGGTACATGTAGCATAGGTCTTTATTTTAGCT | Deletion of H. pylori 26695 rppH |

| CSO-0123 | TGTTTTAGTACCTGGAGGGAATATATTTATAGGGTGTTAATCGTTCAA | Deletion of H. pylori 26695 rppH |

| CSO-0124 | CCGTATAGATTTCGCACAAAT | Deletion of H. pylori 26695 rppH |

| CSO-0125 | GGGATATGAATGTATAAAATCATATTTATT | Verification of H. pylori 26695 rppH deletion |

| CSO-0146 | GTTTTTATCGATGTATGCTCTTTAAGACCCAGC | Cloning of H. pylori 26695 rppH complementation |

| CSO-0147 | GTTTTTCATATGCTCGAATTCAGATCCACGTT | Cloning of H. pylori 26695 rppH complementation |

| CSO-0148 | GTTTTTATCGATCATCAAAGCTTTAGCCAAATACAT | Cloning of H. pylori 26695 rppH complementation |

| CSO-0149 | GTTTTTCATATGCCGTATTTTTGAACGATTAACAC | Cloning of H. pylori 26695 rppH complementation |

| CSO-0505 | GTTCATAGCCTTTATCCACGA | Northern blotting probe for HP0630 (mda66) mRNA |

| CSO-1038 | GTTCCCGCTGTCTGTCCC | Northern blotting probe for HP1161 (flavodoxin) mRNA |

| CSO-2298 | CCGCTTTTAGCGAATGCTTGTCAAGTTATCATTCATATTGTTC | Y oligonucleotide for HP1161 for PABLO assay |

| CSO-2299 | AAAAAAAAAAGAACAATATGAATGATAACTTG | X32 oligonucleotide for PABLO assay |

| CSO-2300 | CAATCTGTTTGGGCTAGCTACAACGAAAATCACCCG | 10–23 DNAzyme for PABLO assay of HP1161 mRNA |

| CSO-2301 | AAATCGTCGCAGGCTAGCTACAACGACAGCGCTAAA | 10–23 DNAzyme for PABLO assay of HP0630 mRNA |

| CSO-2302 | TTCCTTTTCTAATAAAATAGCAAGTTATCATTCATATTGTTC | Y oligonucleotide for HP0630 for PABLO assay |

| HPK1 | GTACCCGGGTGACTAACTAGG | Amplification of aphA-3 cassette |

| HPK2 | TATTCCCTCCAGGTACTAAAACA | Amplification of aphA-3 cassette |

| JVO-0231 | GAGTTTGTCATGGCTACCAA | Northern blotting probe for IsoA1 |

| JVO-0514 | CATGCCATGAAACACAAAAG | Northern blotting probe for IsoA3 |

| JVO-2136 | AACACGAATCATCTAGGCGAT | Northern blotting probe for 6S rRNA |

| JVO-2635 | CGAGAAATACCTCCACACAAT | Northern blotting probe for HPnc2450 |

| JVO-2715 | ATCATATCTTATAAAGGCGTAACTTT | Northern blotting probe for HPnc1980, HPnc1990 |

| JVO-3928 | CTAATCATTTCTAAATCATGCTCG | Northern blotting probe for HPnc5960 |

| JVO-3938 | TCCTTATGGCTCAATTACAAGG | Northern blotting probe for HPnc3560 |

| JVO-5257 | TATAGGTTTTCATTTTCTCCCAC | Verification of H. pylori 26695 rppH deletion |

| pZE-A | GTGCCACCTGACGTCTAAGA | Colony PCR on pZE12-derived plasmids |

Construction of H. pylori rppH Deletion and Complementation Strains

To construct the rppH deletion strain, H. pylori 26695 ΔHP1228::KanR (CSS-0091, ΔrppH from 26695), overlap extension PCR was used to assemble a DNA fragment containing a non-polar KanR (aphA-3) cassette (37) flanked on one side by the first three codons of HP1228 (rppH) and ∼500 additional upstream base pairs and on the other side by the last three codons of HP1228 and ∼500 additional downstream base pairs. First, ∼500 bp upstream of HP1228 codon 4 were amplified from genomic DNA of wild-type H. pylori 26695 (CSS-0065, kindly provided by D. Scott Merrell) using primers CSO-0121/-0122, and ∼500 bp downstream of HP1228 codon 152 (the fourth to last codon) were amplified using primers CSO-0123/-0124. The KanR cassette was amplified using primers HPK1 and HPK2. The purified PCR products, corresponding to regions upstream and downstream of HP1228 as well as the KanR cassette, were mixed at an equimolar ratio and subjected to overlap extension PCR using primers CSO-0121/-0124. The resulting deletion construct was gel-purified and substituted into the chromosome of CSS-0065 by transformation (natural competence) and recombination, yielding CSS-0091 (ΔHP1228::KanR). Positive clones from CSS-0091 were verified by PCR with primers CSO-0125 and JVO-5257.

To generate an rppH complementation strain, the rppH gene and ∼200 additional base pairs on each side of it were amplified from genomic DNA of H. pylori 26695 (CSS-0065) using oligonucleotides CSO-0148/-0149. The PCR product was digested with NdeI (New England Biolabs, catalog no. R0111L) and ClaI (New England Biolabs, catalog no. R0197L). At the same time, plasmid pSP39-3 (41) was amplified using oligonucleotides CSO-0146/-0147 and, after digestion with DpnI, analogously digested with NdeI and ClaI and subsequently dephosphorylated with calf intestinal phosphatase (New England Biolabs, catalog no. M0290L). The PCR products of the plasmid backbone and of the rppH gene were purified, ligated, and transformed into E. coli Top 10 cells (CSS-0296, Invitrogen), yielding plasmid pSS4-2. Positive clones were selected on plates containing 100 μg/ml ampicillin and confirmed by colony PCR using oligonucleotides pZE-A/CSO-0017. Plasmid pSS4-2 contains both the rppH gene under the control of its own promoter and the catGC resistance cassette (52), flanked by the 5′ and 3′ parts of the rdxA locus, respectively. A PCR product amplified from pSS4-2 with oligonucleotides CSO-0017/-0018 was used for complementation of H. pylori 26695 ΔHP1228::KanR (CSS-0091), resulting in strain CSS-0148 (ΔHP1228::KanR; ΔrdxA::HP1228-catGCR), which contains the rppH gene in an antisense orientation relative to the catGC cassette and the rdxA gene. Positive clones from CSS-0148 were verified by PCR with primers CSO-0034/-0148 and sequencing with CSO-0033.

RNA Isolation

Unless stated otherwise, H. pylori was grown in liquid culture to logarithmic phase (A600 ∼1), and cells corresponding to an A600 of 4 were harvested, mixed with 0.2 volumes of stop mix (95% (v/v) EtOH, 5% (v/v) phenol), and immediately shock-frozen in liquid nitrogen. Frozen cell pellets were thawed on ice, centrifuged for 10 min at 3,250 × g at 4 °C, and resuspended in TE buffer (10 mm Tris, 1 mm EDTA, pH 8.0) containing 0.5 mg/ml lysozyme and 1% (w/v) SDS. RNA was extracted using the hot phenol method as described and treated with DNase I (New England Biolabs) according to the manufacturer's instructions (35).

Examination of RNA Stability and Northern Blotting Analysis

To determine the stability of mRNAs and sRNAs in the various H. pylori strains, cells were grown to an A600 of ∼1 and treated with rifampicin (final concentration, 500 μg/ml). Equal volumes of cells (5 ml) were withdrawn 0, 2, 4, 8, 16, and 32 min after the addition of rifampicin and immediately mixed with 0.2 volumes of stop solution (5% water-saturated phenol, 95% ethanol). The cells were promptly frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C until use. Total cellular RNA was isolated by the hot phenol method. For Northern blot analysis, 10 μg of total RNA were subjected to gel electrophoresis on 6% (v/v) polyacrylamide gels containing 7 m urea. RNA was subsequently transferred to a Hybond-XL membrane (GE Healthcare) by electroblotting and then UV-crosslinked to the membrane. Transcripts were detected by probing with 5′-end-labeled (γ-32P) oligodeoxynucleotide probes complementary to specific RNAs of interest, as described (35). Radioactive bands were visualized with a Fuji FLA-3000 imager, and the band intensities were quantified by using AIDA Image Analyzer software version 4.27 (Raytest).

PABLO

Total cellular RNA was extracted from various H. pylori mutant strains by the hot phenol procedure (35). As a control for the PABLO assay, a sample of total RNA from WT cells was treated with TAP to create fully monophosphorylated RNA, as described (46). Briefly, 50 μg of total WT RNA was combined in 44 μl of water with 5 μl of 10× TAP reaction buffer (Epicenter, catalog no. T19500), 1 μl of RNase inhibitor (Molox), and 0.5 μl of TAP (Epicenter, catalog no. T19500). This mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 2 h. Subsequently, 150 μl of autoclaved water was added to facilitate phenol extraction. The products were phenol-extracted once with water-equilibrated phenol and ethanol-precipitated. The pellets were washed with 75% ethanol and air-dried. The RNA was then resuspended in 25 μl of autoclaved water. After that, PABLO analysis was performed, using a portion of the TAP-treated RNA sample as a positive control, as described (46). For the assay, 15 μg of DNase I-treated total cellular RNA per reaction was combined with 2 μl of 10 μm oligonucleotide X32 (CSO-2299) and 4 μl of 1 μm oligonucleotide Y (CSO-2298 for HP1161, CSO-2302 for HP0630). To improve electrophoretic resolution of the ligation product, 4 μl of a 100 μm solution of a site-specific 10–23 DNAzyme oligonucleotide were included as well (CSO-2300 for HP1161, CSO-2301 for HP0630) (46). Water was added to bring the final volume to 45 μl. The samples were heated at 75 °C for 5 min and then cooled gradually to 30 °C before being placed on ice. A premixture (35 μl) containing the following components was added to each sample of RNA complexed with oligonucleotides X32 and Y: 10 μl of T4 DNA ligase (catalog no. M0202, New England Biolabs), 1 μl of RNase inhibitor (Molox), 8 μl of 10× ligation buffer (catalog no. M0202, New England Biolabs), 1.6 μl of 10 mm ATP, and 14.4 μl of H2O. The resulting mixtures were incubated at 37 °C for 4 h and subsequently placed on ice. The ligation reactions were quenched by adding 120 μl of 10 mm EDTA, and the products were phenol-extracted and ethanol-precipitated. The pellets were washed with 75% ethanol and air-dried. The pellets containing the ligation products were dissolved in 5 μl of water, combined with 15 μl of RNA loading buffer (95% (v/v) formamide, 20 mm EDTA (pH 8.0), 0.025% (w/v) bromphenol blue, 0.025% (w/v) xylene cyanol), and heated at 95 °C for 5 min. Electrophoresis was performed on a 6% polyacrylamide gel containing 7 m urea. The gel was electroblotted onto a Hybond-XL membrane (GE Healthcare), and after UV cross-linking, the membrane was probed with radiolabeled DNA complementary to the transcript of interest. Radioactive bands corresponding to ligated and unligated RNA were visualized with a Fuji FLA-3000 imager, and ligation yields were calculated from the measured band intensities (yield = ligated/(unligated + ligated)) using AIDA software (Raytest, Germany).

cDNA Library Preparation and Deep Sequencing

RNA-seq libraries were constructed from total RNA samples harvested in logarithmic growth phase (WT A600 0.7; ΔrppH A600 0.5; CrppH A600 0.7) in BHI medium. Residual genomic DNA was removed from the isolated total RNA by DNase I treatment. cDNA library preparation was performed by Vertis Biotechnology AG in a strand-specific manner as described previously for eukaryotic microRNA (53) but omitting the RNA size fractionation step before cDNA synthesis. In brief, the three RNA samples were each split into three portions. One portion was treated with TEX before the standard library preparation procedure described below to generate the +TEX/+TAP libraries. To this end, RNA was denatured for 2 min at 90 °C, cooled on ice for 5 min, and treated with 1.5 units of TEX (Epicenter) for 30 min at 30 °C. For the second portion, the TAP treatment (see below) was omitted to generate the −TEX/−TAP libraries. The standard procedure without modifications was used to generate the −TEX/+TAP libraries from the third portion. Here, ∼200 ng of RNA sample were poly(A)-tailed using 2.5 units of E. coli poly(A) polymerase (New England Biolabs) for 5 min at 37 °C. The 5′-triphosphates were then converted to monophosphates with TAP. TAP treatment was performed by incubating the samples with 5 units of TAP for 15 min at 37 °C. Afterward, an RNA adapter (5′ Illumina sequencing adapter, 5′-UUUCCCUACACGACGCUCUUCCGAUCU-3′) was ligated to the 5′-P of the TAP-treated, poly(A)-tailed RNA for 30 min at 25 °C. First-strand cDNA was synthesized by using an oligo(dT)-adapter primer (see below) and Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (AffinityScript, Agilent) by incubation at 42 °C for 20 min, ramping to 55 °C, and further incubation at 55 °C for 5 min. In a PCR-based amplification step using a high-fidelity DNA polymerase (Herculase II Fusion DNA polymerases, Agilent), the cDNA concentration was increased to 20–30 ng/μl (initial denaturation at 95 °C for 2 min, followed by 14–16 cycles at 95 °C for 20 s and 68 °C for 2 min). A library-specific barcode for multiplex sequencing was included as part of a 3′-sequencing adapter. The TruSeq index primers for PCR amplification were used according to the instructions of Illumina. For all libraries, the Agencourt AMPure XP kit (Beckman Coulter Genomics) was used to purify the DNA (1.8× sample volume), and cDNA sizes were examined by capillary electrophoresis on a MultiNA microchip electrophoresis system (Shimadzu).

The following adapter sequences flanked the cDNA inserts: TrueSeq_Sense_primer, 5′-AATGATACGGCGACCACCGAGATCTACACTCTTTCCCTACACGACGCTCTTCCGATCT-3′; TrueSeq_Antisense_NNNNNN_primer (where NNNNNN represents the 6n barcode for multiplexing), 5′-CAAGCAGAAGACGGCATACGAGAT-NNNNNN-GTGACTGGAGTTCAGACGTGTGCTCTTCCGATC(dT)25-3′. All libraries were sequenced using an Illumina HiSeq 2000 machine with 97 cycles in single-read mode.

Data Processing and Availability

To ensure high sequence quality, the Illumina reads in FASTQ format were trimmed with a cutoff phred score of 20 by the program fastq_quality_trimmer from FASTX toolkit version 0.0.13. Subsequent processing steps were conducted using the RNA-seq analysis pipeline READemption version 0.4.2 (54). These consisted of poly(A) tail removal followed by size filtering to keep only reads with a minimum length of 12 nt. Remaining reads from all libraries were mapped to the H. pylori 26695 reference genome (NC_000915.1) using segemehl version 0.2.0-418 (55). Read mapping statistics are summarized in Table 1.

Coverage plots representing the numbers of mapped reads per nucleotide were generated. Reads that mapped to multiple (n) locations with an equal score contributed fractionally (1/n) to the coverage value. Each resulting coverage graph was normalized by the number of reads that could be mapped from the respective library (typically several million reads when using Illumina sequencing) and then multiplied by the minimum number of mapped reads calculated over all libraries. Coverage plots were visualized using Artemis (56).

Expression analysis for TSS windows as well as sRNA and housekeeping RNA annotations was also conducted using READemption. Here, read overlap counts for −TEX/+TAP libraries were calculated based on 100-nt windows encompassing previously annotated primary and secondary TSSs for mRNAs, tRNAs, and rRNAs (42) together with their downstream regions and using full-length annotations for sRNAs and housekeeping RNAs (35). Each read with a minimum overlap of 10 nt was counted with a value based on the number of locations where the read was mapped. If the read overlapped more than one annotation, the value was divided by the number of annotations and counted separately for each of them (e.g. ⅓ for a read mapped to three locations). For +TEX/+TAP and −TEX/−TAP libraries, read 5′ ends (first base only) matching to a region from 5 nt upstream to 4 nt downstream of each TSS were counted with a value based on the number of locations where the read was mapped but without considering overlap with more than one annotation. Read counts for +TEX/+TAP and −TEX/−TAP libraries were normalized as described above for the coverage plots. Size factors corresponding to this normalization were used for the pairwise Gfold comparison of −TEX/+TAP counts from WT and ΔrppH as well as CrppH and ΔrppH but were rescaled by the software, resulting in slightly different values for each comparison.

Raw sequencing reads in FASTQ format and normalized coverage files in wiggle (WIG) format are available via the Gene Expression Omnibus under accession number GSE86943. Two of the RNA-seq libraries have already been published in a previous study, where the TSS data used in the current analysis was also generated (42). These were the +TEX/+TAP and −TEX/+TAP libraries from the WT sample, which were used as a replicate for the differential RNA-seq approach described in the former publication.

Comparison between RppH and RNase J Targets

To analyze the overlap between HpRppH and RNase J targets, we extracted sequences for all H. pylori 26695 genes (protein-coding regions, tRNAs, and rRNAs) that were used to define TSSs in previous studies (35, 42) and for the sRNAs/housekeeping RNAs discovered at that time (35). Sequences for all H. pylori B8 genes used to identify RNase J targets (9) were downloaded from the MicroScope platform (57) in FASTA format. Orthologous genes in the two strains were identified by using Ortholuge software (58) while taking care to analyze sRNAs/housekeeping RNAs separately from other RNAs to avoid erroneous mappings between different RNA classes. Next, the reciprocal best BLAST matches in the in1in2.out files were combined and used to map identified B8 homologs to the H. pylori 26695 transcripts assessed in this study. As described previously (9), B8 annotations for which RNase J depletion resulted in a ≥2-fold increase in transcript concentration with an adjusted p value ≤0.05 were considered RNase J targets. Overlapping and non-overlapping target genes are identified in supplemental Tables S2 and S3.

Author Contributions

J. G. B. and C. M. S. designed the research; M. R., P.-K. H., Q. L., H. S. T., P. L. F., and A. H. performed the experiments; T. B. analyzed the data; and J. G. B., C. M. S., M. R., and T. B. wrote the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Konrad U. Förstner (SysMed Core Unit, University of Würzburg, Germany) for help with deep sequencing analysis, Richard Reinhardt (Max Planck Genome Centre, Cologne, Germany) for help with deep sequencing, and Stephanie Stahl (University of Würzburg) for help with the cloning of H. pylori mutants.

Research in the Sharma laboratory was supported by the Young Investigator Program at the Research Center for Infectious Diseases in Würzburg, Germany; the Bavarian Research Network for Molecular Biosystems (BioSysNet); and DFG project Sh580/1-1 of the German Research Association (DFG). Research in the Belasco laboratory was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants 5R01GM035769 and 5R01GM112940 (to J. G. B.) and National Institutes of Health Fellowship T32AI007180 (to P. L. F.). The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

This article contains supplemental Tables S1–S3.

The data reported in this paper have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo (accession no. GSE86943).

- RNA-seq

- high-throughput RNA sequencing

- dRNA-seq

- differential RNA-seq

- TEX

- Terminator 5′-phosphate-dependent exonuclease

- TAP

- tobacco acid pyrophosphatase

- 5′-P and 5′-PPP

- 5′-monophosphorylated and 5′-triphosphorylated, respectively

- TSS

- transcription start site

- nt

- nucleotide(s)

- PABLO

- phosphorylation assay by ligation of oligonucleotides.

References

- 1.Cover T. L., and Blaser M. J. (2009) Helicobacter pylori in health and disease. Gastroenterology 136, 1863–1873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van Amsterdam K., van Vliet A. H., Kusters J. G., and van der Ende A. (2006) Of microbe and man: determinants of Helicobacter pylori-related diseases. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 30, 131–156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hui M. P., Foley P. L., and Belasco J. G. (2014) Messenger RNA degradation in bacterial cells. Annu. Rev. Genet. 48, 537–559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaberdin V. R., Singh D., and Lin-Chao S. (2011) Composition and conservation of the mRNA-degrading machinery in bacteria. J. Biomed. Sci. 18, 23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tomb J. F., White O., Kerlavage A. R., Clayton R. A., Sutton G. G., Fleischmann R. D., Ketchum K. A., Klenk H. P., Gill S., Dougherty B. A., Nelson K., Quackenbush J., Zhou L., Kirkness E. F., Peterson S., et al. (1997) The complete genome sequence of the gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori. Nature 388, 539–547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mathy N., Hébert A., Mervelet P., Bénard L., Dorléans A., Li de la Sierra-Gallay I., Noirot P., Putzer H., and Condon C. (2010) Bacillus subtilis ribonucleases J1 and J2 form a complex with altered enzyme behaviour. Mol. Microbiol. 75, 489–498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shahbabian K., Jamalli A., Zig L., and Putzer H. (2009) RNase Y, a novel endoribonuclease, initiates riboswitch turnover in Bacillus subtilis. EMBO J. 28, 3523–3533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Redko Y., Aubert S., Stachowicz A., Lenormand P., Namane A., Darfeuille F., Thibonnier M., and De Reuse H. (2013) A minimal bacterial RNase J-based degradosome is associated with translating ribosomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, 288–301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Redko Y., Galtier E., Arnion H., Darfeuille F., Sismeiro O., Coppée J. Y., Médigue C., Weiman M., Cruveiller S., and De Reuse H. (2016) RNase J depletion leads to massive changes in mRNA abundance in Helicobacter pylori. RNA Biol. 13, 243–253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mackie G. A. (1998) Ribonuclease E is a 5′-end-dependent endonuclease. Nature 395, 720–723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Richards J., Liu Q., Pellegrini O., Celesnik H., Yao S., Bechhofer D. H., Condon C., and Belasco J. G. (2011) An RNA pyrophosphohydrolase triggers 5′-exonucleolytic degradation of mRNA in Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Cell 43, 940–949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spickler C., Stronge V., and Mackie G. A. (2001) Preferential cleavage of degradative intermediates of rpsT mRNA by the Escherichia coli RNA degradosome. J. Bacteriol. 183, 1106–1109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deana A., Celesnik H., and Belasco J. G. (2008) The bacterial enzyme RppH triggers messenger RNA degradation by 5′ pyrophosphate removal. Nature 451, 355–358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Belasco J. G. (2010) All things must pass: contrasts and commonalities in eukaryotic and bacterial mRNA decay. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 11, 467–478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Messing S. A., Gabelli S. B., Liu Q., Celesnik H., Belasco J. G., Piñeiro S. A., and Amzel L. M. (2009) Structure and biological function of the RNA pyrophosphohydrolase BdRppH from Bdellovibrio bacteriovorus. Structure 17, 472–481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Foley P. L., Hsieh P. K., Luciano D. J., and Belasco J. G. (2015) Specificity and evolutionary conservation of the Escherichia coli RNA pyrophosphohydrolase RppH. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 9478–9486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McLennan A. G. (2006) The Nudix hydrolase superfamily. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 63, 123–143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thompson J. D., Higgins D. G., and Gibson T. J. (1994) CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 22, 4673–4680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hsieh P. K., Richards J., Liu Q., and Belasco J. G. (2013) Specificity of RppH-dependent RNA degradation in Bacillus subtilis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 8864–8869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.She M., Decker C. J., Svergun D. I., Round A., Chen N., Muhlrad D., Parker R., and Song H. (2008) Structural basis of Dcp2 recognition and activation by Dcp1. Mol. Cell 29, 337–349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gabelli S. B., Bianchet M. A., Xu W., Dunn C. A., Niu Z. D., Amzel L. M., and Bessman M. J. (2007) Structure and function of the E. coli dihydroneopterin triphosphate pyrophosphatase: a Nudix enzyme involved in folate biosynthesis. Structure 15, 1014–1022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cartwright J. L., Gasmi L., Spiller D. G., and McLennan A. G. (2000) The Saccharomyces cerevisiae PCD1 gene encodes a peroxisomal nudix hydrolase active toward coenzyme A and its derivatives. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 32925–32930 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gabelli S. B., Bianchet M. A., Ohnishi Y., Ichikawa Y., Bessman M. J., and Amzel L. M. (2002) Mechanism of the Escherichia coli ADP-ribose pyrophosphatase, a Nudix hydrolase. Biochemistry 41, 9279–9285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kang L. W., Gabelli S. B., Cunningham J. E., O'Handley S. F., and Amzel L. M. (2003) Structure and mechanism of MT-ADPRase, a nudix hydrolase from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Structure 11, 1015–1023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yagi T., Baroja-Fernández E., Yamamoto R., Muñoz F. J., Akazawa T., Hong K. S., and Pozueta-Romero J. (2003) Cloning, expression and characterization of a mammalian Nudix hydrolase-like enzyme that cleaves the pyrophosphate bond of UDP-glucose. Biochem. J. 370, 409–415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bessman M. J., Frick D. N., and O'Handley S. F. (1996) The MutT proteins or “Nudix” hydrolases, a family of versatile, widely distributed, “housecleaning” enzymes. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 25059–25062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mildvan A. S., Xia Z., Azurmendi H. F., Saraswat V., Legler P. M., Massiah M. A., Gabelli S. B., Bianchet M. A., Kang L. W., and Amzel L. M. (2005) Structures and mechanisms of Nudix hydrolases. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 433, 129–143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Piton J., Larue V., Thillier Y., Dorléans A., Pellegrini O., Li de la Sierra-Gallay I., Vasseur J. J., Debart F., Tisné C., and Condon C. (2013) Bacillus subtilis RNA deprotection enzyme RppH recognizes guanosine in the second position of its substrates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 8858–8863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lundin A., Nilsson C., Gerhard M., Andersson D. I., Krabbe M., and Engstrand L. (2003) The NudA protein in the gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori is an ubiquitous and constitutively expressed dinucleoside polyphosphate hydrolase. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 12574–12578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guo B. P., and Mekalanos J. J. (2002) Rapid genetic analysis of Helicobacter pylori gastric mucosal colonization in suckling mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 8354–8359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vasilyev N., and Serganov A. (2015) Structures of RNA complexes with the Escherichia coli RNA pyrophosphohydrolase RppH unveil the basis for specific 5′-end-dependent mRNA decay. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 9487–9499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu H., Semino-Mora C., and Dubois A. (2012) Mechanism of H. pylori intracellular entry: an in vitro study. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2, 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]