Abstract

Targeting the tumor-specific junction sequence produced by the BCR-ABL fusion has long been an attractive strategy and, in this issue of Blood, Comoli et al demonstrate, for the first time in humans, clinical benefit with infusions of p190BCR-ABL neoantigen-specific T cells to 3 patients with active Philadelphia chromosome–positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia (Ph+ ALL).1

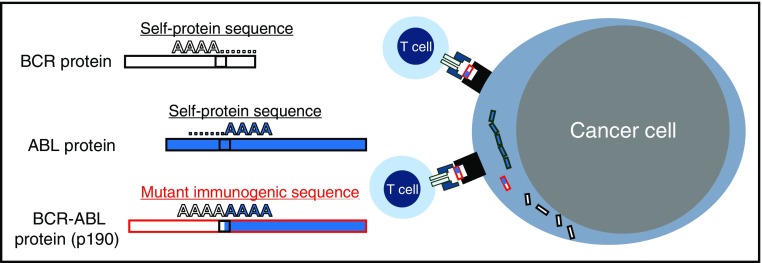

p190BCR-ABL junctional neoantigen sequence that elicits T-cell responses. The BCR-ABL translocation results in the creation of a “neoantigen” located at the junction of both otherwise “self” proteins. This foreign amino acid sequence presented in the context of major histocompatibility complex molecules can elicit T-cell responses; in this issue, Comoli et al go on to demonstrate that patients with Ph+ ALL can derive a clinical benefit from infusions of BCR-ABL–reactive T cells.

The potent effects of tyrosine-kinase inhibitors (TKIs) such as imatinib both in addition to front-line chemotherapy and as a single agent in patients unfit for chemotherapy has highlighted the benefit of targeting the BCR-ABL mutant protein in Ph+ ALL. Indeed, imatinib has significantly improved complete remission (CR) rates from 70% with chemotherapy alone to over 90% when front-line chemotherapy is combined with imatinib.2 Unfortunately, unlike chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), a large proportion of patients with Ph+ ALL eventually relapse despite TKI treatment.3 In these patients, CD19 chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-modified T-cell immunotherapy is emerging as a mainstream salvage option, but not without inducing “on-target, off-tumor” toxicities such as B-cell aplasia and other potentially fatal problems such as cytokine release syndrome and neurological toxicities.4 Therefore, the work by Comoli et al is particularly attractive as they enriched naturally occurring, polyclonal neoantigen-specific T cells from both patients and healthy donors and then administered these cells to Ph+ ALL patients, combining the benefits of adoptive T-cell therapy with the selective targeting of the “cancer-exclusive” p190BCR-ABL neoantigen sequence.

Like viral proteins, neoepitopes generated from somatic mutations within tumors such as the junctional amino acid sequence of the BCR-ABL fusion (see figure) are promising “nonself” and hence immunogenic T-cell targets. Naturally occurring neoantigen-specific T cells have been described for a spectrum of cancer-related mutations, including the fusion product of BCR-ABL, as highlighted in the authors’ previous work.5,6 As the native T-cell repertoire is shaped by the thymus to minimize self-recognition, T cells that protect against “nonself” foreign antigens are positively selected explaining their existence. These endogenous T cells can induce durable remissions whether they are activated ex vivo using tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes7 or in vivo using immune checkpoint inhibitors.8 Another recent noteworthy report described a patient with metastatic colon cancer who attained CR after treatment with T-cell clones isolated from the patients’ tumor that had specificity for a neoantigen derived from a KRAS mutation.9 It is significant though that Comoli et al, for the first time, could reactivate neoantigen-specific T cells from not only patients, but also their stem cell donors in order to tackle the major problem of leukemia relapse.

The choice of which neoantigen to target is often challenging as tumors harvested from different sites or at different time points, even within the same patient, could have strikingly different mutational patterns. The BCR-ABL tyrosine-kinase neoantigen is in some ways an ideal T-cell target for leukemias because it (1) is common (>20% of adult ALL and in all patients with CML), (2) develops early during carcinogenesis (truncal mutations vs branched), so nearly all cells are positive, and (3) has a critical role in propagating the cancer phenotype.

In this report, Comoli et al were successful in generating and administering T-cell products with specificity for the mutant sequence of p190BCR-ABL protein to 3 patients with active Ph+ ALL. Two patients had relapsed disease (minimal residual disease [MRD] in one and overt relapse in the other) post–allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (alloHSCT). One patient who had TKI-resistant MRD received an autologous product, whereas the post-HSCT patients received donor-derived T-cell products. To ensure selective targeting of the mutant sequence, all products were stimulated with 9-mer peptide pools spanning the junctional region of BCR-ABL only. As expected, in all patients, there was an increase in the frequency of bone marrow (BM) T cells specific for BCR-ABL postinfusion. This correlated with a deepening of the molecular response in the 2 patients with MRD and a complete hematologic response (66%-2% BM blasts) in the patient with overt relapse. Both patients treated with donor-derived products had previously relapsed post–donor lymphocyte infusions, and one of them has now maintained a major molecular response for over 4 years postinfusion. Remarkably, none of the 3 reported patients developed any infusion-related adverse events, including graft-versus-host disease, cytokine release syndrome, or neurological toxicity.

Although impressive, this study remains a proof-of-concept case series that will need to be replicated in confirmatory trials to establish safety and then efficacy. One of the limitations of targeting small, highly selected amino acid sequences is that they are typically only immunogenic in the context of specific HLA types, so the feasibility of applying this strategy broadly to patients that bear the p190BCR-ABL translocation will need to be tested in patients with diverse HLA haplotypes. Because all patients received T cells concurrently with TKIs, it remains to be seen whether BCR-ABL–specific T cells will be capable of inducing single-agent responses similar to that observed with CD19 CAR T cells. The authors propose using this therapy in combination with TKIs for patients unfit for high-dose chemotherapy or alloHSCT, and it will be interesting to see whether this combination will engender TKI- or T-cell–resistant clones.

In summary, the elegant work by Comoli et al has given us a teaser to the beneficial in vivo effects of infusing BCR-ABL neoantigen-specific T cells in patients with Ph+ ALL. In concert with the recent success of adoptively transferred neoantigen-specific T cells in a patient with colon cancer, this report highlights the emerging successes and limited toxicities associated with T-cell products selectively targeting cancer-specific mutants.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: H.E.H. has received research support from Cell Medica and Celgene and is a founder of ViraCyte. P.L. declares no competing financial interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Comoli P, Basso S, Riva G, et al. BCR-ABL–specific T-cell therapy in Ph+ ALL patients on tyrosine-kinase inhibitors. Blood. 2017;129(5):582-586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wassmann B, Pfeifer H, Goekbuget N, et al. Alternating versus concurrent schedules of imatinib and chemotherapy as front-line therapy for Philadelphia-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia (Ph+ ALL). Blood. 2006;108(5):1469-1477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jones D, Thomas D, Yin CC, et al. Kinase domain point mutations in Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia emerge after therapy with BCR-ABL kinase inhibitors. Cancer. 2008;113(5):985-994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brudno JN, Kochenderfer JN. Toxicities of chimeric antigen receptor T cells: recognition and management. Blood. 2016;127(26):3321-3330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cohen CJ, Gartner JJ, Horovitz-Fried M, et al. Isolation of neoantigen-specific T cells from tumor and peripheral lymphocytes. J Clin Invest. 2015;125(10):3981-3991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Riva G, Luppi M, Barozzi P, et al. Emergence of BCR-ABL-specific cytotoxic T cells in the bone marrow of patients with Ph+ acute lymphoblastic leukemia during long-term imatinib mesylate treatment. Blood. 2010;115(8):1512-1518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Verdegaal EM, de Miranda NF, Visser M, et al. Neoantigen landscape dynamics during human melanoma-T cell interactions. Nature. 2016;536(7614):91-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McGranahan N, Furness AJ, Rosenthal R, et al. Clonal neoantigens elicit T cell immunoreactivity and sensitivity to immune checkpoint blockade. Science. 2016;351(6280):1463-1469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tran E, Robbins PF, Lu YC, et al. T-cell transfer therapy targeting mutant KRAS in cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(23):2255-2262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]