Abstract

Background and study aims It is important to examine the pharynx during upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. Pharyngeal anesthesia using topical lidocaine is generally used as pretreatment. In Japan, lidocaine viscous solution is the anesthetic of choice, but lidocaine spray is applied when the former is considered insufficient. However, the relationship between the extent of pharyngeal anesthesia and accuracy of observation is unclear. We compared the performance of lidocaine spray alone versus lidocaine spray combined with lidocaine viscous solution for pharyngeal observation during transoral endoscopy.

Patients and methods In this prospective, double-blinded, randomized clinical trial conducted between January and March 2015, 327 patients were randomly assigned to lidocaine spray alone (spray group, n = 157) or a combination of spray and viscous solution (combination group, n = 170). We compared the number of pharyngeal observable sites (non-inferiority test), pain by visual analogue scale, observation time, and the number of gag reflexes between the two groups.

Results The mean number of images of suitable quality taken at the observable pharyngeal sites in the spray group was 8.33 (95 % confidence interval [CI]: 7.94 – 8.72) per patient, and 8.77 (95 % CI: 8.49 – 9.05) per patient in the combination group. The difference in the number of observable pharyngeal sites was – 0.44 (95 % CI: – 0.84 to – 0.03, P = 0.01). There were no differences in pain, observation time, or number of gag reflexes between the 2 groups. Subgroup analysis of the presence of sedation revealed no differences between the two groups for the number of pharyngeal observation sites and the number of gag reflexes. However, the number of gag reflexes was higher in the spray group compared to the combination group in a subgroup analysis that looked at the absence of sedation.

Conclusions Lidocaine spray for pharyngeal anesthesia was not inferior to lidocaine spray and viscous solution in terms of pharyngeal observation. It was considered that lidocaine viscous solution was unnecessary for pharyngeal observation. UMIN000016073

Introduction

Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy (UGE) is a common diagnostic procedure. However, patients usually experience severe discomfort during transoral UGE because of the strong gag reflex and pain that occur when the endoscope is passed through the pharynx 1 2 3.

To reduce transoral UGE-induced gag reflex and pain, topical pharyngeal anesthesia is administered, either alone or in combination with intravenous sedation 4 5. Lidocaine is the topical anesthetic of choice, administered as either a viscous solution or a spray.

There is some literature comparing lidocaine viscous solution and spray in UGE. The Japan Gastroenterological Endoscopy Society (JGES) recommends use of lidocaine viscous solution prior to endoscopy; use of lidocaine spray is recommended only if the viscous solution is considered insufficient 6. However, topical lidocaine spray may be a better option than lidocaine viscous solution because of a higher procedural completion rate, greater ease of intubation, and greater satisfaction for both the patient and endoscopist 7.

Recent advances in endoscopic instruments, including magnifying endoscopy and narrow band imaging (NBI), have enabled more in-depth examinations. Transoral UGE with NBI has been found to improve the early diagnosis of superficial squamous cell pharyngeal carcinomas 8 9 10. Early detection is associated with a better prognosis and use of minimally invasive treatment techniques such as endoscopic resection. However, endoscopic observation of the pharynx is difficult, and some pharyngeal tumors may remain undiagnosed. To reduce the rate of undiagnosed cancers, it is important to observe the pharynx carefully under less-active gag reflex, and to know the blind spots in the pharynx.

To identify the best anesthetic for pharyngeal observation, we conducted a prospective, double-blinded, randomized clinical trial that compared lidocaine spray alone (spray group) with a combination of lidocaine spray and viscous solution (combination group).

The viscous solution is hard to swallow because of its viscous texture and bitter taste 4 11. In addition, it prolongs the duration of pharyngeal anesthesia and increases the risk of lidocaine intoxication. In this study, if the spray group was not inferior to the combination group in terms of pharyngeal observation, lidocaine viscous solution would be considered unnecessary. We devised a non-inferiority trial to test this hypothesis.

Patients and methods

Patients

Patients age ≥ 20 years undergoing transoral UGE from January to March 2015 provided written informed consent prior to endoscopy. Only patients who agreed to participate in the study were enrolled. Patients who had previously undergone surgical or endoscopic mucosal resection for pharyngeal cancer were excluded, because their pharynxes had been removed or were too damaged to evaluate. Other exclusion criteria were a history of allergy of lidocaine, difficulty participating in the test because of psychosis or psychotic symptoms, and determined to be unable to carry out the study.

Study design and anesthesia protocols

This prospective, double-blinded, randomized study was conducted with patients from a single center (Kanazawa University Hospital, Ishikawa, Japan).

We inquired about study participants’ expectation of sedation at the time of informed consent, before group allocation. If expectation of sedation is confirmed after group allocation, the patients in the spray group are more likely to expect more sedation than those in the combination group. The enrolled patients were randomized by computer-generated numerical codes to receive either spray or spray plus viscous solution (simple randomization, allocation ratio 1:1). A stratification factor (by sedation status or presence/absence of sedation) was included in the analysis because the results are likely to depend on sedation. The randomization list was stored in the clinical laboratory department, and could not be accessed by the study researchers.

The combination group received lidocaine viscous oral solution 2 % (Xylocaine Viscous 2 %; AstraZeneca, Osaka, Japan). Lidocaine viscous solution was allowed to accumulate in the back of the throat for about 3 to 5 minutes. The spray group received a placebo (the patient could not distinguish the two by taste) that was allowed to accumulate in the back of the throat for about 3 to 5 minutes, similar to lidocaine viscous solution. After this step, participants of both groups inhaled five puffs (40 mg) of lidocaine (Xylocaine Pump Spray 8 %; AstraZeneca, Osaka, Japan).

To remain blinded, the endoscopist entered the room only after pharyngeal anesthesia.

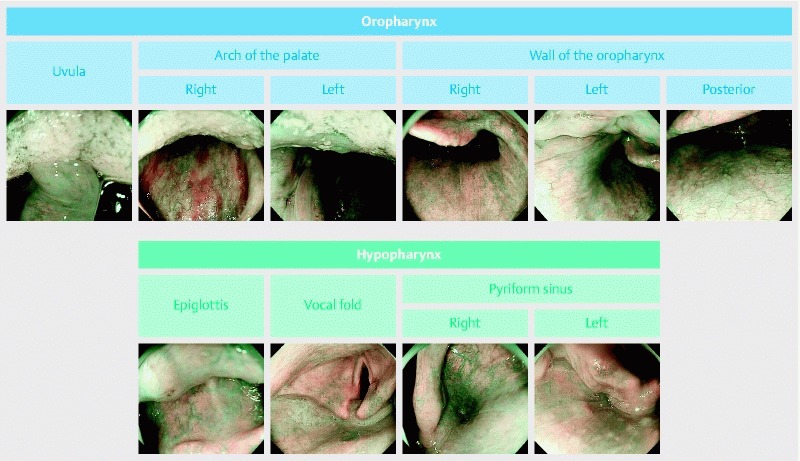

According to a previously described method 12, the endoscopist took the first image immediately upon insertion of the endoscope, followed by 6 endoscopic images of the oropharynx, 4 images of the hypopharynx, and 1 image before insertion into the esophagus. The nasopharynx was not included in these examinations. Overall, 12 narrow band images were obtained per patient. We determined the time before the endoscopist was able to obtain any images. The endoscopist inserted the endoscope into the esophagus when it was impossible to obtain images as a result of a continuous gag reflex.

Two endoscopists (T. H. and Y. A.) measured the time between the first and last images, and assessed whether the ten images of the oropharynx and hypopharynx were appropriate (Fig. 1). The endoscopists were blind to the study arm and independent from endoscopists who examined patients. The definition of an appropriate image required 3 criteria. First, the image was taken at the appropriate location. Second, the image was on focus. Third, mucus had been removed, and it was possible to evaluate the color of the pharyngeal mucosa in the images. Screening and pharyngeal examination were performed under unmagnified observation.

Fig. 1.

The 10 images of the oropharynx and hypopharynx. The definition of a high-quality image required 3 criteria: first, the image was taken at the appropriate location; second, the image was on focus; third, mucus had been removed, and it was possible to evaluate pharyngeal mucosa color.

After the endoscopic procedure was carried out, the following data were recorded for each patient: age, gender, height, weight, body mass index (BMI), Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status (PS), drinking and smoking habits, and the number of endoscopic procedures.

Subjective symptoms of pain were evaluated by questionnaire after endoscopy. Pain was evaluated on an 11-point visual analogue scale (VAS), where 0 indicated no pain, and 10 points indicated the most severe pain.

The researcher evaluated pharyngeal observation time and whether images of predetermined sites were clear. Two independent blinded expert endoscopists evaluated the quality of the images obtained at the predetermined sites. In case of disagreement, consensus was reached upon discussion with a panel of 3 other expert endoscopists.

Endoscopic examinations

All endoscopic procedures were carried out using a magnifying endoscope (GIF-H260Z; Olympus Medical Systems, Tokyo, Japan) with a hood attachment (MAJ-1990; Olympus Medical Systems). The videoendoscopy system used in this study comprised a video processor (EVIS LUCERA ELITE CV-290; Olympus Medical Systems) and a light source (EVIS LUCERA ELITE CLV-290SL; Olympus Medical Systems). Prior to the procedure, each patient was given 100 mL water containing 20,000 units pronase (Kaken Pharmaceutical, Tokyo, Japan), 1 g sodium bicarbonate, and 10 mL dimethylpolysiloxane (20 mg/mL; Horii Pharmaceutical Industries, Osaka, Japan).

Afterward, pharyngeal anesthesia was performed as described in “Study design and anesthesia protocols.”

Patients were placed in the left lateral decubitus position, with endoscopic examinations carried out while they were awake or under conscious sedation with midazolam (Dormicum Injection; Astellas Pharma, Tokyo, Japan). The patient's wish to the use of a sedative was obtained before the procedure. The sedative was adjusted within the range of 2 mg to 5 mg based on the patient's body weight. The pharynx was assessed at the beginning of each examination, and standard endoscopy was carried out at the end of each pharyngeal examination. If pharyngeal lesions were detected, the examination was completed first and the lesions were evaluated at the end of endoscopy.

Outcome measures

The main outcome was a difference in the number of pharynx observable sites between the spray group and combination group (non-inferiority trial).

The secondary outcomes were (1) a difference in endoscopy-associated pain; (2) a difference in the pharyngeal observation time; (3) subgroup analysis of presence or absence of sedation; (4) adverse effects of lidocaine including decreased SpO2 (< 90 % or decrease of more than 4 % for < 94 %) decreased blood pressure (systolic blood pressure < 90 mmHg), and bradycardia (< 60/bpm or decrease of more than 10 %) 12; and (5) the percentages of suitable quality images obtained at the ten prescribed points.

Statistical analysis

Sample size was calculated as follows. An experienced endoscopist is expected to be able to observe 90 % (9.0 sites) of the pharyngeal sites 13. A non-inferiority threshold [Δ] of 10 % (1.0 site) was selected to indicate that it was acceptable that the number of pharyngeal sites observed in the spray group was 10 % lower than that in the combination group. It was estimated that at least 310 cases were required to detect statistically significant differences, admitting a type I error rate of 0.025 (one-sided test) and a statistical power of 90 %. Therefore, we have determined that it was necessary to include a total of 320 cases in consideration of dropouts.

Presence or absence of sedation was used as stratification factor.

Continuous variables are expressed as mean (standard deviation [SD]), and comparisons between groups were performed using the Student’s t-test or Mann Whitney U test (not approximately normally distributed). Categorical variables are expressed as percentage, and comparisons between groups were performed using Fisher exact tests. The level of statistical significance was defined as a P value < 0.05. Only the researchers performed the collection and aggregation of data. All statistical analyses were performed with SPSS II statistical software (SPSS Japan Inc., Tokyo, Japan).

Ethics statement

The protocol and consent form for this study were approved by the institutional review board of Kanazawa University Hospital. The study conformed to the Declaration of Helsinki, complied with thical Guideline for Clinical Research of the ministry, and has been registered in the UMIN Clinical Trials Registry System as trial ID UMIN-CTR000016073.

Results

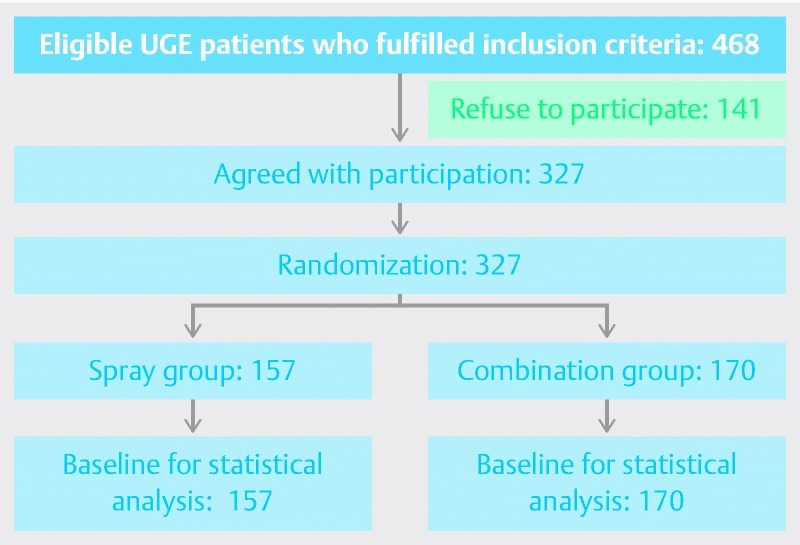

Fig. 2 shows a flow chart of patient selection and allocation. There were 468 eligible UGE patients who fulfilled the inclusion criteria. Of those, 141 patients refused to participate in the study. Finally, 327 patients were enrolled and randomly allocated to the spray group (157 patients) and the combination group (170 patients) by computer-generated codes.

Fig. 2.

Flowchart of patient enrollment.

Patient demographics and clinical characteristics are shown in Table 1. The patients in the 2 groups were similar with regard to age, gender, height, weight, BMI, ECOG PS, drinking habits, smoking habits, the number of endoscopic procedures, and patients requiring sedation and antispasmodic drugs.

Table 1. Patient demographics and clinical characteristics.

| Spray group(n = 157) | Combination group(n = 170) | |

| Age, y | 65.4 ± 15.5 | 65.3 ± 12.6 |

| Gender (male:gemale) | 84:73 | 97:73 |

| Height, cm | 160.5 ± 9.4 | 160.8 ± 9.2 |

| Weight, kg | 57.5 ± 12.2 | 59.2 ± 12.4 |

| Body mass index | 22.2 ± 3.6 | 22.7 ± 3.4 |

| ECOG PS(0:1: ≥ 2) | 105:43:9 | 120:39:11 |

| Drinking habit(Never:Sometimes:One or more times per week:Every day) | 87:26:17:27 | 83:34:20:22 |

| Smoking habit: (no:yes) | 86:71 | 101:69 |

| Number of endoscopies(1st time: 2nd to 4th times: 5th times or more) | 10:78:69 | 20:91:59 |

| Sedation ( + :-) | 108:49( + : 68.8 %) | 115:55( + : 67.6 %) |

| Antispasmodic ( + :-) | 77:80( + : 49.0 %) | 94:76( + : 55.3 %) |

The rate of agreement between the two endoscopists was 92.4 %, and the Kappa statistic was 0.767.

The mean number of images with suitable quality of the pharyngeal observable sites per patient in the spray group was 8.33 (95 % confidence interval [CI]: 7.94 – 8.72), and that in the combination group was 8.77 (95 % CI: 8.49 – 9.05). The difference in the number of pharyngeal observable sites was – 0.44 (95 % CI: – 0.84 to – 0.03, P = 0.01) (Table 2).

Table 2. Non-inferiority test of the difference of pharyngeal observable sites (based on a type I error rate of 0.025 [one-sided test], a statistical power of 90 %, and a non-inferiority threshold [Δ] of 0.1).

| Spray group (95 % CI) | Combination group (95 % CI) | Difference (95 % CI) | P value |

| 8.33 (7.94~8.72) | 8.77 (8.49~9.05) | –0.44 (–0.84~–0.03) | 0.01 |

Table 3 shows the difference in pain and situation during endoscopy. There were almost no differences in pain evaluated by VAS (2.27 ± 2.88 vs. 2.33 ± 2.63, P = 0.85), pharyngeal observation time (72.0 ± 34.7 vs. 67.0 ± 27.8 seconds, P = 0.15), and the number of gag reflexes (2.12 ± 2.58 vs. 1.68 ± 2.27, P = 0.10) in the two groups. There were almost no differences in adverse events, decrease of SpO2 (2.55 % vs. 5.29 %, P = 0.20), decrease of blood pressure (0 % vs. 1.76 %, P = 0.27), and bradycardia (0 % vs. 0 %, P = 1.00) between the 2 groups.

Table 3. Differences in pain and situation during endoscopy.

| Spray group(n = 157) | Combination group(n = 170) | P value | |

| Pain by visual analogue scale | 2.27 ± 2.88 | 2.33 ± 2.63 | 0.85 |

| Pharyngeal observation time, seconds | 72.0 ± 34.7 | 67.0 ± 27.8 | 0.15 |

| Number of gag reflexes | 2.12 ± 2.58 | 1.68 ± 2.27 | 0.10 |

| Adverse events | |||

| (Decrease in SpO2) | 4 (2.55 %) | 9 (5.29 %) | 0.20 |

| (Decrease in blood pressure) | 0 (0 %) | 3 (1.76 %) | 0.27 |

| (Bradycardia) | 0 (0 %) | 0 (0 %) | 1.00 |

Subgroup analysis for presence of sedation (223 cases) revealed almost no differences between the 2 groups in the number of pharyngeal observation sites (8.48 ± 2.16 vs. 8.79 ± 1.85, P = 0.25), pain evaluated by VAS (1.08 ± 2.06 vs. 1.33 ± 2.16, P = 0.79), pharyngeal observation time (73.3 ± 36.6 vs. 68.3 ± 30.9 seconds, P = 0.14), and number of gag reflexes (2.02 ± 2.44 vs. 1.86 ± 2.45, P = 0.63) (Table 4). Subgroup analysis of absence of sedation (104 cases) revealed almost no differences between the 2 groups in the number of pharyngeal observation sites (8.00 ± 3.12 vs. 8.73 ± 1.94, P = 0.63), pain evaluated by VAS (4.75 ± 2.79 vs. 4.30 ± 2.37, P = 0.20), and pharyngeal observation time (69.1 ± 30.1 vs. 64.1 ± 19.9 seconds, P = 0.16). The number of gag reflexes was significantly higher in the spray group than in the combination group (2.35 ± 2.87 vs. 1.27 ± 1.79), P = 0.03) (Table 4).

Table 4. Subgroup analysis of presence or absence of sedation.

| Sedation ( + ) | Spray group(n = 108) | Combination group(n = 115) | P value |

| Age, y | 64.5 ± 16.0 | 63.8 ± 13.6 | |

| Gender (male:female) | 55:53 | 61:54 | |

| Ramsay score | 4.83 ± 1.26 | 4.89 ± 1.25 | |

| Pharyngeal observable site | 8.48 ± 2.16 | 8.79 ± 1.85 | 0.25 |

| Pain by visual analogue scale | 1.08 ± 2.06 | 1.33 ± 2.16 | 0.79 |

| Pharyngeal observation time, seconds | 73.3 ± 36.6 | 68.3 ± 30.9 | 0.14 |

| Number of gag reflex | 2.02 ± 2.44 | 1.86 ± 2.45 | 0.63 |

| Sedation (–) | Spray group(n = 49) | Combination group(n = 55) | P value |

| Age, y | 67.5 ± 14.1 | 68.3 ± 9.49 | |

| Gender (male:female) | 29:20 | 36:19 | |

| Pharyngeal observable site | 8.00 ± 3.12 | 8.73 ± 1.94 | 0.16 |

| Pain by visual analogue scale | 4.75 ± 2.79 | 4.30 ± 2.37 | 0.20 |

| Pharyngeal observation time, seconds | 69.1 ± 30.1 | 64.1 ± 19.9 | 0.16 |

| Number of gag reflex | 2.35 ± 2.87 | 1.27 ± 1.79 | 0.03 |

Table 5 shows the percentages of suitable quality images obtained at the ten prescribed points. The percentage of suitable quality images at the right pyriform sinus was significantly lower in the spray group compared to the combination group (82.8 % vs. 91.2 %, P = 0.02). There were no significant differences in the percentage of suitable quality images at any of the other points the between the 2 groups.

Table 5. Percentages of suitable quality images obtained at the ten tested points.

| Spray group(n = 157) | Combination group(n = 170) | P value | ||

| Uvula | 78.3 | 84.1 | 0.18 | |

| Arch of the palate | Right | 84.7 | 87.6 | 0.44 |

| Left | 77.7 | 77.1 | 0.89 | |

| Wall of the oropharynx | Right | 87.9 | 91.8 | 0.25 |

| Left | 85.4 | 91.8 | 0.07 | |

| Posterior | 92.4 | 96.5 | 0.10 | |

| Epiglottis | 74.5 | 81.8 | 0.11 | |

| Vocal fold | 86.6 | 90.0 | 0.34 | |

| Pyriform sinus | Right | 82.8 | 91.2 | 0.02 |

| Left | 82.8 | 85.3 | 0.54 |

Discussion

This is the first study evaluating pharyngeal observation in patients receiving lidocaine spray alone versus lidocaine viscous solution and spray combination as topical pharyngeal anesthesia. According to a previous report, topical lidocaine spray may be described as a better option than lidocaine viscous solution because of higher procedural completion rate, greater ease of intubation, and greater satisfaction for both the patient and the endoscopist 7. If the spray group were not inferior to the combination group in terms of pharyngeal observation, lidocaine viscous solution would be considered unnecessary. We found that lidocaine spray alone performs similar to lidocaine spray plus viscous solution for pharyngeal observation during transoral endoscopy. For the observation of the pharynx, addition of lidocaine viscous solution was found not to be necessary.

Side effects of lidocaine include an anaphylactoid reaction and poisoning after an increase in concentration of circulating lidocaine. The frequency of anaphylactoid reactions is low among amide-type local anesthetics such as lidocaine. However, methylparaben, which is added as a preservative, has similar structure and cross-antigenicity to para-aminobenzoic acid. Para-aminobenzoic acid can induce T-lymphocyte antibody production and sensitization, and eventually cause an allergic reaction. Thus, anaphylactoid reactions are probably non-immunoglobulin E-mediated anaphylactoid reactions in which the presence of methylparaben in the local anesthetic solution plays a major role 14. Methylparaben is included in lidocaine viscous solution, but not in lidocaine spray.

Local anesthetics poisoning by lidocaine spray is thought to occur because the concentration of lidocaine is higher in the spray than in the viscous solution. However, 5 puffs of spray (40 mg lidocaine per puff) are usually sufficient for pharyngeal anesthesia. It is extremely rare to use more than 200 mg lidocaine per dose; a higher dosage could cause local anesthetics poisoning during pharyngeal anesthesia. In other words, the possibility of poisoning by lidocaine spray alone is considered to be extremely rare in pharyngeal anesthesia. However, the combined use of lidocaine spray and viscous solution increase the potential of poisoning. To prevent poisoning, it is important to perform minimal pharyngeal anesthesia with a valid method. In this study, the number of adverse events was higher in the spray group compared to the combination group, although this different was not significant because of the small number of events. Although the effect of sedation is suspected to decrease SpO2 or blood pressure, it is undeniable that adverse effects of lidocaine are stronger in the combination group. To prove this fact, it is necessary to perform the study in a larger number of cases.

There were no significant differences in pain by VAS, pharyngeal observation time, or the number of gag reflexes between the 2 groups. These differences were also considered to be very clinically slight. The differences of 0.06 points for the VAS (max 10 points), 5.0 seconds of pharyngeal observation time, and 0.44 times of gag reflexes were not clinically meaningful.

In the subgroup analysis of each pharyngeal site, the spray group was inferior to the combination group in terms of observation of the right pyriform sinus, statistically. But the difference of 8.4 % of observation rate of this structure was not clinically meaningful. This difference could be attributable to multiple comparisons, and there might be no statistically significant difference in left pyriform sinus observation. Although the possibility of the effect of anesthesia in the hypopharynx being stronger in the combination group cannot be denied, it is necessary to assess a larger number of cases because the results are not consistent between the left and right sides. Since the pyriform sinus is the predilection site of pharyngeal cancer 15, it is desirable to perform further studies on the relationship between the extent of hypopharyngeal anesthesia and pharyngeal observation.

In this study, the number of gag reflexes was significantly higher in the spray group than in the combination group in subgroup analysis (no sedation). It is possible that the no-sedation group was more susceptible to pharyngeal anesthesia. Conscious sedation during endoscopic examination can provide more adequate anxiolysis and acceptance than wakefulness 16.

Because of strong pain experienced by the patients, there are some opinions that pharyngeal observation is not needed. However, the overall rate of detection of pharyngeal cancer by screening endoscopy is as low as 0.26 % 16. In patients who are not at increased risk of pharyngeal cancer, the rate of detection of pharyngeal cancer is 0.11 % 17. Although this rate is lower than the 0.26 % of gastric cancer detection rate by regular screening 18, it is not a negligible value. Therefore, we are of the opinion that screening pharyngeal observation is necessary.

Heuss reported that topical pharyngeal anesthesia does not seem to influence the ease of the procedure or patient or endoscopist satisfaction in adequately sedated patients 19. Nevertheless, it remains unclear whether pharyngeal anesthesia improves pharyngeal observation in adequately sedated patients. A future prospective, double-blinded, randomized clinical trial is necessary to clarify this issue.

This study has some limitations. First, it was carried out at a single institution. Second, patients might be aware of the placebo of the viscous solution by detecting subtle differences in taste. Third, our study did not evaluate the postcricoid area. The nasal Valsalva and trumpet maneuvers with anterior neck skin traction cannot be carried out using transoral endoscopy 20. The sniffing position in the left decubitus position can improve examination of the postcricoid area 21. Future studies are needed to explore these methods.

Conclusion

In conclusion, with and without sedation, using only lidocaine spray for pharyngeal anesthesia was not inferior to using lidocaine spray and viscous solution in terms of pharyngeal observation. While the overall findings support the hypothesis that lidocaine viscous solution is unnecessary for pharyngeal observation, the subgroup analysis of each pharyngeal site indicated that spray might be inferior to combination treatment with regard to pyriform sinus observation.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Gaku Oishi, Hidetoshi Nakagawa, Fumiyo Iida, Miyabi Miura, Naoki Oishi, Norihiko Ogawa, Masaki Nishitani, Noriho Iida, Tetsuhiro Shimode, Kazunori Kawaguchi, and endoscopy medical staff in Kawazana University Hospital.

Footnotes

Competing interests None

References

- 1.Leslie K, Stonell C A. Anaesthesia and sedation for gastrointestinal endoscopy. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2005;18:431–436. doi: 10.1097/01.aco.0000168328.02444.3c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Campo R, Brullet E, Montserrat A et al. Identification of factors that influence tolerance of upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1999;11:201–204. doi: 10.1097/00042737-199902000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mogensen S, Treldal C, Feldager E et al. New lidocaine lozenge as topical anesthesia compared to lidocaine viscous oral solution before upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. Local Reg Anesth. 2012;5:17–22. doi: 10.2147/LRA.S30715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shaoul R, Higaze H, Lavy A. Evaluation of topical pharyngeal anaesthesia by benzocaine lozenge for upper endoscopy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;24:687–694. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.03023.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Evans L T, Saberi S, Kim H M et al. Pharyngeal anesthesia during sedated EGDs: is “the spray” beneficial? A meta-analysis and systematic review. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:761–766. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2005.11.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kawaguchi M, Aoki S.Guidelines for digestive endoscopy3rd ed.Tokyo: Japan Gastroenterological Endoscopy Society; 2006

- 7.Amornyotin S, Srikureja W, Chalayonnavin W et al. Topical viscous lidocaine solution versus lidocaine spray for pharyngeal anesthesia in unsedated esophagogastroduodenoscopy. Endoscopy. 2009;41:581–586. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1214865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Muto M, Nakane M, Katada C et al. Squamous cell carcinoma in situ at oropharyngeal and hypopharyngeal mucosal sites. Cancer. 2004;101:1375–1381. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Muto M, Katada C, Sano Y et al. Narrow band imaging: A new diagnostic approach to visualize angiogenesis in superficial neoplasia. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2005;3:16–S20. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(05)00262-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Muto M, Minashi K, Yano T et al. Early detection of superficial squamous cell carcinoma in the head and neck region and esophagus by narrow band imaging: A multicenter randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1566–1572. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.4680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Asante M A, Northfield T C. Variation in taste of topical lignocaine anaesthesia for gastroscopy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1998;12:685–686. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1998.00355.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Collinsworth K A, Kalman S M, Harrison D C. The clinical pharmacology of lidocaine as an antiarrhythmic drug. Circulation. 1974;50:1217–1230. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.50.6.1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tsuji K, Doyama H, Takeda Y et al. Use of transoral endoscopy for pharyngeal examination: cross-sectional analysis. Dig Endosc. 2014;26:344–349. doi: 10.1111/den.12211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kajimoto Y, Rosenberg M E, Kyttä J et al. Anaphylactoid skin reactions after intravenous regional anaesthesia using 0.5% prilocaine with or without preservative -- a double-blind study. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1995;39:782–784. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.1995.tb04170.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barnes L, Johnson J T. Pathologic and clinical considerations in the evaluation of major head and neck specimens resected for cancer. Part I. Pathol Annu. 1986;21:173–250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McQuaid K R, Laine L. A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials of moderate sedation for routine endoscopic procedures. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67:910–923. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2007.12.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nakanishi H, Doyama H, Takemura K et al. Detection of pharyngeal cancer in the overall population undergoing upper GI endoscopy by using narrow-band imaging: a single-center experience, 2009 – 2012. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;79:558–564. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2013.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kitagawa S. Digestive cancer screening nationwide summary report (Japan) J Gastroenterol Cancer Screen. 2015;53:87–101. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heuss L T, Hanhart A, Dell-Kuster S et al. Propofol sedation alone or in combination with pharyngeal lidocaine anesthesia for routine upper GI endoscopy: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, non-inferiority trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:1207–1214. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.07.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Draper M R, Blagnys B, Premachandra D J. To 'EE' or not to 'EE'. J Otolaryngol. 2007;36:191–195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mori S, Yokoyama A, Matsui T et al. Endoscopic screening for upper aerodigestive tract cancer in alcoholics using wide visualization of the pharynx and esophageal iodine staining procedures. Gastroenterol Endosc. 2011;53:1426–1434. [Google Scholar]