SUMMARY

The RSC chromatin remodeler slides and ejects nucleosomes, utilizing a catalytic subunit (Sth1) with DNA translocation activity, which can pump DNA around the nucleosome. A central question is whether and how DNA translocation is regulated to achieve sliding versus ejection. Here, we report the regulation of DNA translocation efficiency by two domains residing on Sth1 (Post-HSA and Protrusion 1), and by actin-related proteins (ARPs) which bind Sth1. ARPs facilitated sliding and ejection by improving ‘coupling’ – the amount of DNA translocation by Sth1 relative to ATP hydrolysis. We also identified and characterized Protrusion 1 mutations that promote ‘coupling’, and Post-HSA mutations that improve ATP hydrolysis; notably, the strongest mutations conferred efficient nucleosome ejection without ARPs. Taken together, sliding-to-ejection involves a continuum of DNA translocation efficiency, consistent with higher magnitudes of ATPase and coupling activities (involving ARPs and Sth1 domains), enabling the simultaneous rupture of multiple histone-DNA contacts facilitating ejection.

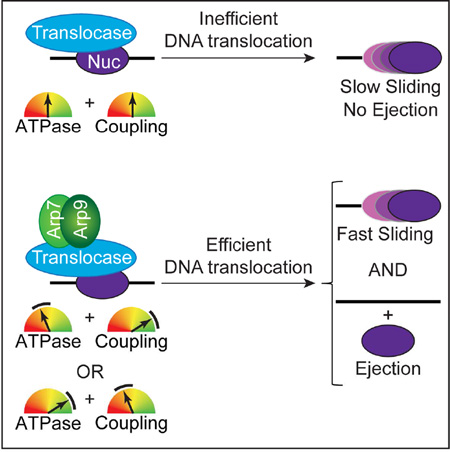

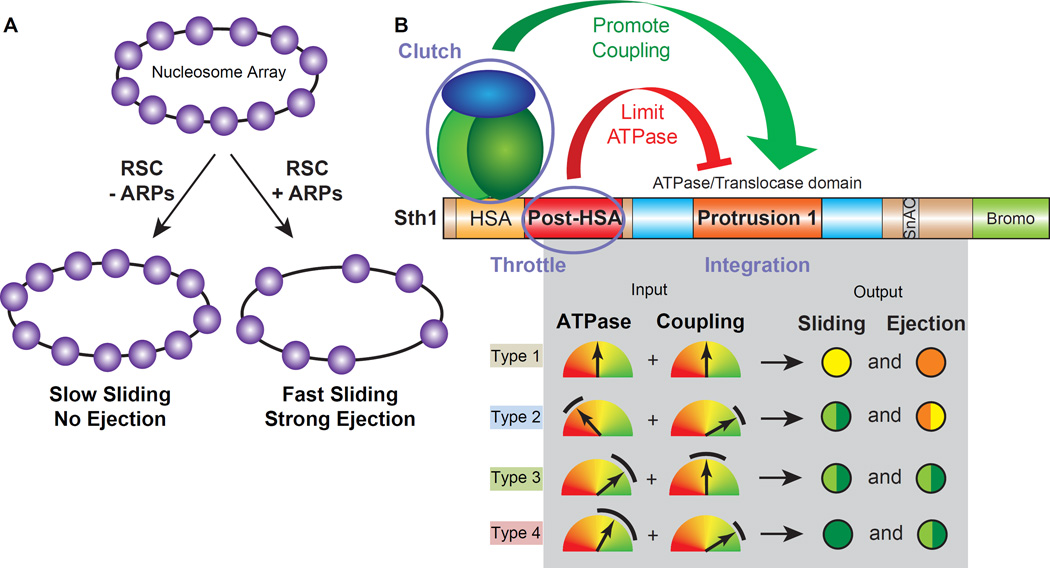

Graphical Abstract

eTOC

Clapier et al. establish that the chromatin remodeling complex RSC conducts regulated ATP-dependent DNA translocation. Distinct domains and actin-related proteins separately regulate ATPase activity and DNA translocation efficiency. These parameters combine to tune nucleosome sliding, and at higher levels, to cause the simultaneous rupture of multiple histone-DNA contacts, enabling ejection.

INTRODUCTION

SWI/SNF-family chromatin remodeling complexes provide DNA-binding proteins access to their sites in chromatin by mobilizing or removing histone octamers, termed nucleosome sliding or ejection, respectively (Clapier and Cairns, 2014). RSC is an essential and abundant SWI/SNF-family chromatin remodeling complex from S. cerevisiae (Cairns et al., 1996) that slides and ejects nucleosomes. Although histone ejection is widely studied in vivo (Boeger et al., 2003; Parnell et al., 2008) and in vitro (Lorch et al., 2011; Lorch et al., 2006), little is known regarding domains or proteins that regulate ejection by SWI/SNF-family remodelers.

The catalytic subunit of RSC, Sth1, is a DNA translocase that pumps DNA around the nucleosome (Saha et al., 2002), using a central ATPase/translocase domain flanked by the HSA domain (Szerlong et al., 2008), which nucleates an ‘ARP module’ that includes two actin-related proteins (ARPs), Arp7 and Arp9 (an obligate heterodimer), and the ARP-binding and -bridging protein Rtt102 (Cairns et al., 1998; Szerlong et al., 2008; Schubert et al., 2013). Furthermore, Rtt102 biases the ARPs toward their ‘compact’ rather than their ‘extended’ conformation (Lobsiger et al., 2014; Schubert et al., 2013; Turegun et al., 2013) (Figure 1A). ARPs are conserved in SWI/SNF-family remodelers, and are important for viability, growth or development in vivo (Cairns et al., 1998; Ho and Crabtree, 2010; Peterson et al., 1998; Shen et al., 2003; Zhao et al., 1998).

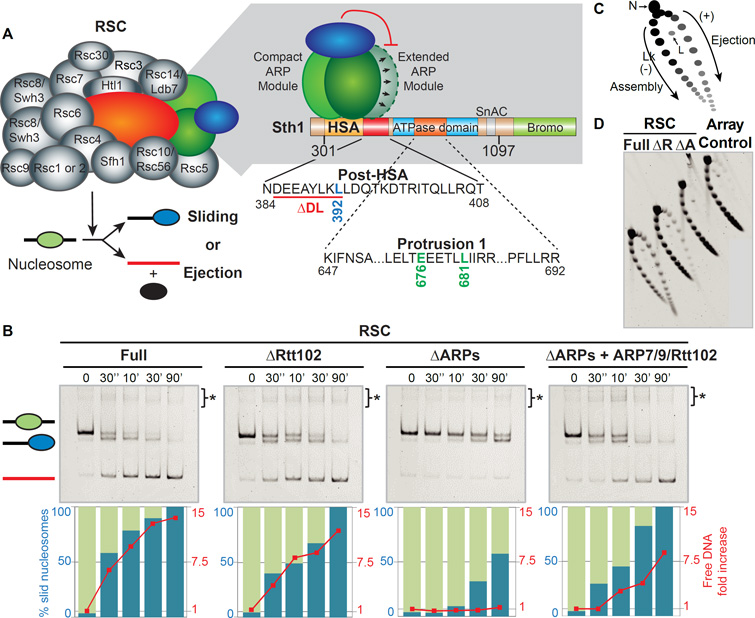

Figure 1. Actin-related proteins promote nucleosome ejection by RSC.

(A) RSC, with core motor subunits colored and accessory subunits in grey. Below, the two alternative outcomes of nucleosome remodeling by RSC. At right, scheme of RSC core motor subunits and their interactions (note: Rtt102-biases ARP conformations, see main text) and conserved Sth1 regulatory domains, with outset (below) depicting the mutations derived and investigated.

(B) Comparative sliding and ejection of mononucleosomes by RSC derivatives. Enzyme:substrate molar ratio is 1:2. ARP module re-addition (right panel) involves a 2-fold molar ratio over RSC ΔARPs. Bracket*; (here, and upper region of native gels) other remodeling intermediates (e.g RSC/Sth1-nucleosome complexes). Here, and in subsequent figures, a representative gel from multiple experiments is shown.

(C) Principle of the nucleosome array ejection assay, with supercoiled plasmid (topoisomer) distribution revealed by 2D gel. Lk: Linking number, N: Nicked, L: Linear.

(D) Comparative nucleosome array ejection by RSC derivatives, (1:2 RSC:Nuc molar ratio; 90 min).

See also Figures S1, S2 and S4.

ARPs interact physically and functionally with the remodeler ATPase subunit (Chen et al., 2013; Shen et al., 2003; Yang et al., 2007; Zhao et al., 1998) but important aspects regarding their mechanistic relationship to DNA translocation, nucleosome sliding and ejection are poorly understood. ARPs are essential in yeast, however genome-wide screens for arpΔ suppressors yielded mutations in STH1 itself, which mapped to two small domains: one located just after the HSA domain (termed Post-HSA domain), and one located centrally within the ATPase/translocase domain (termed Protrusion 1) (Flaus et al., 2006). These genetic results link ARPs to the Post-HSA and Protrusion 1 domains, but whether they regulate DNA translocation, sliding or ejection remains untested. Here, we reveal that ARPs along with the associated protein Rtt102 work together with the Post-HSA and Protrusion 1 domains to regulate DNA translocation efficiency, potentiating nucleosome sliding and enabling ejection.

RESULTS

In RSC, the ARP Module Promotes Sliding and Enables Ejection

To characterize ARP module function, we isolated RSC complexes lacking Rtt102 or the entire ARP module (figure S1A). We also reconstituted and purified a recombinant ARP module: Arp7, Arp9, and Rtt102 (figure S1B). We find that under catalytic conditions (2-fold excess of nucleosomes) RSC conducted efficient mononucleosome sliding and progressive mononucleosome ejection. Remarkably, the loss of ARPs and Rtt102 greatly reduced nucleosome sliding, and eliminated ejection (Figure 1B). Notably, loss of Rtt102 alone attenuated sliding but preserved ejection, linking nucleosome ejection to ARP function. Furthermore, the ARP module loss reduced but did not eliminate sliding; with a slid nucleosome representing the dominant final product (Figure 1B). Remarkably, re-addition of the ARP module to RSC (lacking the ARP module) largely restores sliding and ejection (Figure 1B). Thus, the ARP module promotes sliding, and is largely required for ejection in this assay.

To provide a complementary system for monitoring ejection, we assembled nucleosome arrays (which better represent the natural substrate) on circular plasmids, in the presence of topoisomerase. Each assembled nucleosome on the plasmid stores one negative supercoil as writhe, allowing the extent of assembly (the number of nucleosomes on the array) to be monitored by examining the distribution of plasmid DNA topoisomers using two-dimensional gel electrophoresis (Figure 1C). Here, after the removal of topoisomerase and nucleosomes, the plasmid will contain one negative supercoil for each nucleosome formerly residing on the plasmid. Thus, each ‘dot’ on the ‘arc’ represents a plasmid topoisomer, with more fully assembled plasmids (with higher topological linking numbers, and more nucleosomes) found on the lower left of the ‘arc’ with progressively less assembled states (and successively fewer nucleosomes) distributed in a clockwise manner along the arc, and unassembled plasmids present at the lower right terminus. For example, the loss of one nucleosome from the plasmid during remodeling by RSC redistributes that plasmid one position/dot clockwise along the arc.

Remarkably, we observed a major change in array topoisomer distribution with full RSC, consistent with nucleosome ejection under catalytic conditions (2-fold molar excess of nucleosomes over RSC; no histone chaperone). As with mononucleosomes above (Figure 1B), ejection was diminished by removing Rtt102, nearly abolished by removing the ARP module (Figure 1D), and partially restored by the re-addition of the ARP module (figure S1C). Thus, RSC can implement ejection without a histone chaperone, and utilizes the ARP module.

Although nucleosome ejection intuitively explains topological changes, we also tested other alterations that could impact the twist or writhe of DNA (Cote et al., 1998; Guyon et al., 2001; Ulyanova and Schnitzler, 2005). For example, a RSC-DNA complex, or a RSC-nucleosome complex or its product - such as two nucleosomes brought into close/overlapping proximity - can cause a change in DNA writhe. To distinguish nucleosome loss from other alternatives, we examined the persistence of the topological state following the removal of ATP (via apyrase) and/or removal of remodeler interaction (via competitor DNA), and incubated a further 2–8h, to allow for possible reversion of topology (Cote et al., 1998; Guyon et al., 2001; Lorch et al., 2011). With RSC, and also with a highly active recombinant Sth1 derivative (L392P, described below) the large majority of the topological affect was not reversible (figure S2), strongly supporting nucleosome ejection as the main remodeling product.

Dominant-negative STH1D Alleles Bear Mutations within the Post-HSA Domain

Our parallel genetic work generated a series of Sth1 domain mutations useful for biochemical analysis of regulated DNA translocation and nucleosome remodeling. We acquired and utilized two different types of STH1 mutations: 1) STH1 mutations capable of suppressing the lethality conferred by arpΔ mutations, to reveal Sth1 domains and functions linked to ARPs, and 2) dominant-lethal STH1D mutations (capable of killing wild type cells) to reveal Sth1 domains and gain-of-function activities that might link to, or be independent of ARPs. Regarding the first type, our prior genetic work yielded ten STH1 mutations that suppressed arpΔ lethality, all of which mapped within two small, essential and conserved Sth1 domains, termed Post-HSA and Protrusion 1 (Szerlong et al., 2008) (Figure 1A).

To obtain the alternative ‘dominant-lethal’ type, we conducted a second genetic screen that involved random mutagenesis of STH1, regulated expression of these mutated STH1 alleles in vivo, and screening for potent STH1D alleles that caused potent dominant lethality. Interestingly, this screen yielded three mutations within the Post-HSA domain. Notably, the most potent mutation (L392P) mapped to the same amino acid (L392) isolated in the arpΔ suppressor screen (L392V); thus, different substitutions of L392 in the Post-HSA of Sth1 either kill WT cells (L392P, red; Figure 2A), or resurrect an arpΔ strain (L392V, green). In principle, these STH1D mutations could be dominant due to a loss of function of Sth1 activity, or instead due to a gain-of-function property. To help inform, we tested whether loss of DNA translocation within Sth1 confers dominant lethality. However, expression of catalytically-inactive Sth1 allele (Sth1K501R) conferred only slightly slower growth, and (notably) so did combination of L392P with K501R (Figure 2A). Thus, the STH1D alleles isolated above represent dominant gain-of-function mutations that require catalytic activity to greatly impair growth. Certain mutations from these two screens (L392P, L392V, E676Q, L681F; Figure 1A), were integrated into our biochemical studies for functional characterization.

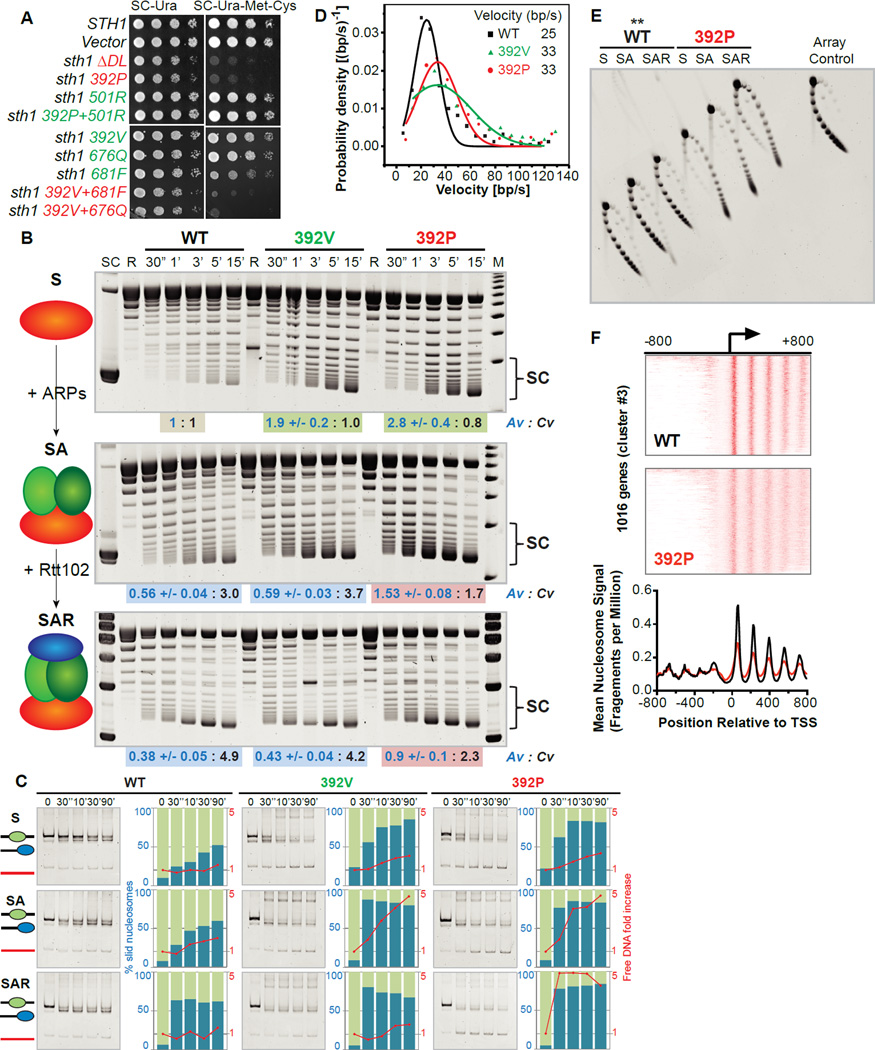

Figure 2. ARPs promote coupling, while the Post-HSA domain regulates ATPase activity.

(A) Dominant lethality (red) conferred by expression of particular STH1Post-HSA alleles or by combining two mutations that separately confer arpΔ suppression (green).

(B) Comparative ‘Tet-tethered’ DNA-translocation activity measured by accumulation of plasmid supercoiled (SC) topoisomers (see Figure S3A), with plasmid-stimulated ATPase activity (Av, blue text; represented as mean +/− SEM) and coupling value (Cv, black text). Background color reflects classification into ‘Types’ (see Figure 4, Figure S8 and Discussion). At left, S: Sth1 alone; SA: Sth1+ARPs; SAR: Sth1+ARPs+Rtt102. SC: highly-supercoiled topoisomers, R: Relaxed plasmid, M: Marker.

(C) Comparative sliding and ejection of mononucleosomes (S, SA, SAR formats). Enzyme:substrate molar ratio is 1:2.

(D) Single molecule measurements (optical tweezers) reveal enhanced velocity of DNA translocation with L392V or L392P mutation (SA format).

(E) Comparative nucleosome array ejection. **WT samples derived from the same experiment, run on a separate gel.

(F) Impact on nucleosome positioning in vivo following expression of Sth1 WT or L392P, displaying nucleosome midpoints for promoters (heat map, top and middle panels) or mean nucleosomal profile (bottom panel); data is from one typical cluster (cluster#3; see Figure S6 for all clusters).

See also Figures S1, S2, S3, S4, S5 and S6.

ARPs Help Couple ATP Hydrolysis to DNA Translocation

To characterize functional interactions between the ARP module and these Sth1 domain mutations, we developed a versatile and robust remodeling system involving purified recombinant RSC ‘core motor’ proteins consisting of Sth1 (WT or derivatives) containing or lacking ARP module components (figure S1D). Sth1 derivative endpoints (residues 301–1097, Figure 1A) were defined by proteolysis, activity, and stability assays. Then, Sth1 was fused to the DNA-binding domain of the Tet repressor, enabling monitoring of DNA translocation in ‘tethered’ formats involving plasmid supercoiling (Clapier and Cairns, 2012) or (in selected instances) single molecule approaches (Sirinakis et al., 2011) (assay schematics, figures S3A and S3B).

To evaluate DNA translocation efficiency, we first visualized DNA translocation in a time course using the plasmid supercoiling assay (Figure 2B), quantified translocation by measuring the highly-supercoiled topoisomers at 15min (SC bracket), and also measured plasmid-stimulated ATPase activity and its linear range (figure S4A). Our ‘reference’ enzyme is wild type (WT) Sth1 alone (S), which displayed moderate DNA-stimulated ATPase activity, and low DNA translocation (Figure 2B, top left); here, the observed DNA translocation and ATPase activity/value (Av) of WT Sth1 itself were normalized to 1.0. Intuitively, ‘coupling’ involves the amount of DNA translocation relative to ATP hydrolysis; is a measure of efficiency, with improved coupling involving a clear increase in DNA translocation without increasing ATP hydrolysis. Therefore, a ‘coupling value’ (Cv) is obtained by dividing the amount of DNA translocation by the amount of ATP hydrolysis, which for WT Sth1 alone yields a Cv of 1.0. This normalization allows quantitative comparisons of Av and Cv following the addition of ARPs and/or Rtt102, mutations in Post-HSA and Protrusion 1, and combinations of these factors/mutations (compiled in Table S1).

Importantly, addition of ARPs (SA) lowered ATPase activity but increased DNA translocation (Figure 2B, middle left), providing a clear increase in coupling (Cv). Addition of Rtt102 (SAR) further increased DNA translocation, while further lowering ATPase (Figure 2B, bottom left), reinforcing coupling. In keeping with translocation, ARPs and Rtt102 improved sliding (Figure 2C, left panels). (Note: sliding by RSC or these Sth1 derivatives is strictly ATP dependent (Figures S4B and S4C)). Notably, ARP addition modestly enhanced ejection in both mono and array formats, but ejection was attenuated by Rtt102, which lowered ATPase (Figures 2C and 2E). Thus, the ARP module enhances ‘coupling’, suggesting that ARPs in their ‘compact’ conformation, promoted by Rtt102, (Turegun et al., 2013) help couple ATP hydrolysis to DNA translocation.

Post-HSA Mutations Increase ATPase Activity, Improve Sliding and Enable Efficient Ejection

Although RSC and its core motor (SA) can eject nucleosomes, the efficiency of ejection (and the impact of ARPs) were of different magnitudes with full RSC versus the core motor system. Here, we reasoned that our core motor system may have the capacity to implement ejection at levels similar to full RSC, but lacks a particular input that informs the ejection decision; an input that might be provided/mimicked by our STH1 genetic mutations.

To explore, we implemented the STH1 alleles from our genetic screens (and follow-up site-directed mutants) within our recombinant core motor format. Interestingly, for the Post-HSA domain, the arpΔ suppressor (L392V) or dominant-lethal (L392P) alleles conferred moderate-strong increases in ATPase activity, DNA translocation and sliding (Figures 2B and 2C) – but had little or no impact on coupling (Table S1). This impact prompted tests of translocation in a single molecule optical tweezer format, using Tet-tethered Sth1 WT, L392V, or L392P (with ARPs). Here, we observed a striking increase in DNA translocation velocity with the L392V and L392P derivatives (Figure 2D) without impacting processivity (Figure S3C). Furthermore, these Post-HSA mutations enabled ejection from mononucleosomes; an activity reinforced by ARP addition (Figure 2C). Extension to nucleosome arrays revealed strong ejection by Post-HSA mutations (for L392P Figure 2E; for L392V Figures 3C and 3F). Moreover, deletion of conserved Post-HSA residues (Δ385–392, termed ΔDL, Figure 1A), conferred dominant lethality in vivo (Figure 2A) and very high ATPase, translocation, sliding and ejection activities in vitro (Figure S5). We note that L392V and L392P display similar upregulation in most DNA translocation and remodeling assays (compared to WT), with L392P trending higher in a subset of assays; thus, additional assay types are needed to fully understand the lethal impact of L392P. However, all Post-HSA mutations consistently upregulate ATPase activity and DNA translocation, but not coupling, and improve one or more remodeling capabilities, establishing the Post-HSA as a negative regulator of catalytic activity.

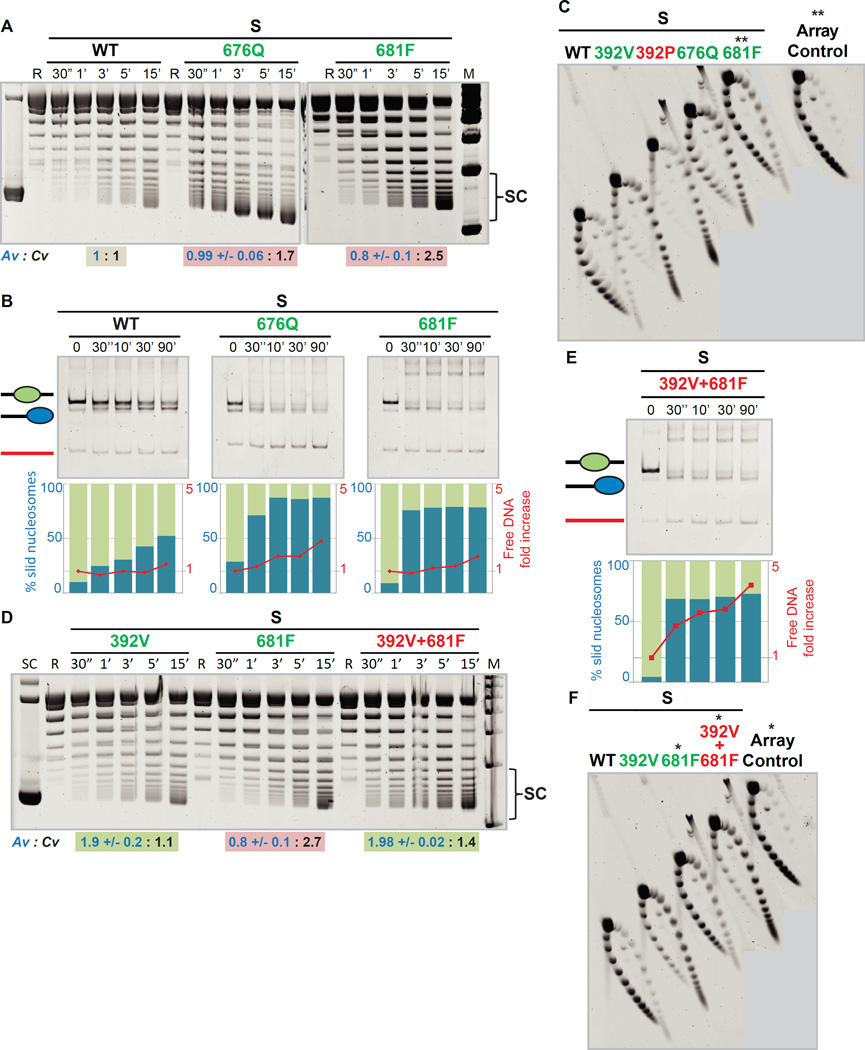

Figure 3. The Protrusion 1 domain integrates ATP hydrolysis and coupling, and synergizes with the Post-HSA.

(A) The Protrusion 1 domain mediates and enhances coupling. Comparative DNA-translocation, plasmid-stimulated ATPase activity (Av, blue text) and coupling values (Cv, black text), as in Figure 2B. Background color reflects classification into ‘Types’ (see Figure 4) SC: highly-supercoiled topoisomers, R: Relaxed plasmid, M: Marker.

(B) Protrusion 1 suppressor mutations enhance nucleosome sliding. Comparative sliding and ejection of mononucleosomes (S format). Enzyme:substrate molar ratio is 1:2.

(C) Protrusion 1 suppressor mutations moderately enhance array ejection. **Samples from the same experiment, run on a different gel.

(D), (E) and (F) Combining Post-HSA and Protrusion 1 suppressor mutations increases DNA translocation (conditions and display as in Figure 3A, panel D) and confers strong ejection in mononucleosome (panel E) or array (panel F) assays. (S format; conditions as in B). *Samples from the same experiment, moved within the same gel to aid depiction. Note: the L681F samples are the same in panels C and F.

See also Figure S7 for an additional mutant combination.

Post-HSA Mutations Impact Nucleosome Positioning in vivo

We next tested whether Post-HSA mutations that conferred high sliding and ejection activities in vitro would also disrupt chromatin structure in vivo by mapping nucleosome positions via mononucleosome isolation and sequencing. Here, we employed a degron system (Parnell et al., 2008) which enabled the degradation of genome-encoded WT Sth1 protein, alongside the simultaneous expression of either WT, L392P or ΔDL derivatives of Sth1 using the methionine-regulated MET25 promoter. We utilized a time point (2 h) at which the vast majority of genome-encoded WT Sth1 protein was degraded, but the cells remained >95% viable (Parnell et al., 2008).

Whereas expression of WT Sth1 provided the expected sharp positioning of nucleosomes at the majority of promoters, expression of L392P or ΔDL derivatives conferred a less-uniform (‘fuzzy’) nucleosomal arrays (Figure 2F; Figure S6), consistent with increased sliding or ejection activities despite competition of replacement/assembly by ISWI-family remodelers. As the majority of nucleosomes are affected, and as Sth1 occupies the majority of promoters (~70% at 1% FDR; Figure S6), the L392P and ΔDL mutant derivatives likely remodel in a misregulated/hyperactive mode in vivo, similar to their behavior in vitro. Taken together, the Post-HSA domain regulates/throttles Sth1 ATPase activity, as Post-HSA mutations increase Sth1 ATPase activity and subsequent remodeling activities in vitro, with excessive levels correlated with lethality and less-uniform positioning in vivo.

Protrusion 1 Mutations Increase Coupling, and Improve both Sliding and Ejection

Regarding Protrusion 1 domain function, the arpΔ suppressor mutations E676Q or L681F strikingly increased Sth1 DNA translocation, while largely maintaining ATPase activity/values (Av) – thus greatly promoting coupling (Cv, Figure 3A; Table S1). In keeping, both mutations confer major increases in sliding efficiency and modest-to-substantial increases in ejection (Figures 3B and 3C). Notably, these mutations confer coupling improvement directly on Sth1, as the effect of the mutations on Sth1 activity is evident without ARPs, consistent with their isolation as arpΔ suppressors. Taken together, arpΔ suppressors compensate for ARP loss (lower coupling) by improving Sth1 ATPase activity (via Post-HSA mutations) or coupling (via Protrusion 1 mutations).

Combining Protrusion 1 and Post-HSA Mutations Improves Translocation

We next combined arpΔ suppressor mutations in Protrusion 1 and the Post-HSA, and (compared to isolated mutations) observed moderate enhancement of DNA translocation, nucleosome sliding, and ejection in the array format (Figures 3D–3F; see Figure S7 for other mutant combinations, and titrations for sliding). These combinations exhibited even higher levels of ATPase activity (Av), but not coupling (Cv), suggesting that Protrusion 1 mutations help maintain coupling at high ATPase levels and/or permit even higher Av outputs from Post-HSA mutations, improving DNA translocation. Interestingly, combining arpΔ suppressors in these two domains caused lethality in vivo (Figure 2A), which may reflect an intolerably high level of DNA translocation.

DISCUSSION

Although histone sliding and ejection are of critical importance in vivo, little is known regarding domains or proteins that regulate these functions within SWI/SNF-family remodelers. For RSC, the catalytic subunit Sth1 conducts ATP-dependent DNA translocation, pumping DNA around nucleosomes, providing the ‘engine’ for sliding and ejection. We provide here clear evidence that DNA translocation in RSC is a regulated activity, and reveal both regulatory proteins and domains. First, we demonstrate that nucleosome sliding, and especially ejection, is greatly stimulated by ARPs (Figure 4A), which directly bind Sth1 and promote DNA translocation by increasing ‘coupling’ the amount of DNA translocated per ATP hydrolysis (Figure 4B). Moreover, the ARPs cooperate with two Sth1 domains, Post-HSA and Protrusion 1, which specifically regulate either ATP hydrolysis or ‘coupling’, respectively (Figure 4B), improve DNA translocation velocity (via single molecule analysis), and impact nucleosome positioning in vivo. Our genetic studies clearly link these domains to ARP function, as gain-of-function Post-HSA or Protrusion 1 mutations suppress arpΔ lethality, and improve ATPase or coupling activities, respectively.

Figure 4. ARPs promote nucleosome ejection by RSC - and the integration of ATPase and coupling potentiates nucleosome sliding and ejection.

(A) ARPs enhance sliding (not depicted) and enable ejection in a nucleosome array format.

(B) A model for the integration of ATPase and coupling in remodeling outcomes. Summary of the impact of Sth1 regulatory domains (Post-HSA and Protrusion 1) and interacting proteins (ARPs and Rtt102) on DNA translocation and nucleosome remodeling (sliding and ejection). Different ATPase and coupling activities were grouped into four Input ‘Types’. A colored tachometer represents ATPase and Coupling activities/values, and the same color spectrum displays the impact on sliding and ejection. Red: none. Orange: low/weak. Yellow: moderate. Light Green: high/strong. Dark Green: very high. The black arcs represent the range of values displayed by the different Sth1 complexes (WT or mutants, +/− ARPs and Rtt102) within these Types. See Table S1 for all ATPase and coupling activities/values, and Figure S8 for examples of Input Types linked to the model.

See also Figures S8, S9 and Table S1.

Overall, the logic for regulating nucleosome sliding and ejection involves the proper blending of ATP turnover (Av) and coupling (Cv). To illustrate, the Sth1 derivatives/complexes tested here were classified into four ‘Types’ (color coded), based on their Av and Cv values (Table S1), and then linked to their impact on sliding and ejection (Figure 4B). Our ‘reference’ enzyme is WT Sth1 alone (Type 1), which displays moderate Av and Cv, and confers low-to-moderate sliding, but not ejection. Interestingly, addition of ARPs greatly increased Cv while lowering Av (Type 2), which strongly increased sliding, and enabled low ejection; here, a major upregulation of coupling compensates for a modest reduction in ATPase activity. Thus, ARPs implement strong coupling even at low ATP turnover. Type 3 Sth1 derivatives (e.g. (S) L392V) strongly increase Av, while maintaining coupling within a moderate range, conferring strong sliding and ejection. Finally, Type 4 derivatives (e.g. (S) E676Q) strongly increase Cv, while Av remains within a moderate-high range, which confers strong-very strong sliding and ejection. Taken together, sliding is improved by increasing Av or Cv, and large increases in one parameter can compensate for moderate decrease in the other. Furthermore, strong ejection is observed only when moderate-high ranges of Av are combined with moderate-high ranges of Cv; however, either one or both parameters must be in the high range (>1.5). (Additional examples and discussion are provided in Figure S8). We note that the Sth1 derivatives that display the highest Av values and strongest DNA translocation confer lethality.

A key insight is that Sth1 alone is intrinsically capable of strong DNA translocation, but full ATPase and coupling abilities are held in check by regulatory domains and proteins. Here, the Post-HSA domain acts as a ‘throttle’ to control ATPase activity, whereas Protrusion 1 along with the ARP module may work together as a ‘clutch’ to control coupling (Figure 4B). We propose that the ARP module folds back and interacts directly with the ATPase domain and Protrusion 1 to form an interface where the integration of ATPase and coupling activities occurs. Furthermore, the ARP module toggles between a compact and extended conformation, with Rtt102 promoting ARP compaction (Turegun et al., 2013), which may further enhance coupling. As ARP compaction also alters the exposure/conformation of the adjacent Post-HSA domain, alterations in ATPase activity are further predicted. The Protrusion 1 domain may detect the conformation of the ARPs and adjacent Post-HSA domain, serving as part of an ‘integrator’ that relays to the ATPase domain the appropriate ATPase and coupling levels to implement, regulating sliding and ejection (Figure 4B). Regarding conservation, SWI/SNF- and INO80-subfamily remodelers both have ARPs bound to their HSA domains. Notably, INO80-subfamily remodelers have two additional ARPs bound to their ATPase domain, and prior studies support Arp5 and Arp8 in regulating ATPase activity and nucleosome sliding (Shen et al., 2003). Thus, ARP regulation of ATPase function (‘throttle and/or clutch’) may be a unifying principle, with future studies needed to explore their precise roles in each remodeler subfamily.

How might strong DNA translocation achieve nucleosome ejection? Intuitively, strong DNA translocation activity may enable the simultaneous rupture of multiple histone-DNA contacts, causing histone loss from the RSC-bound nucleosome (Boeger et al., 2003; Bruno et al., 2003; Lorch et al., 2006; Lorch et al., 2011). An alternative mode of nucleosome ejection involves the pulling/spooling of DNA off of the neighbouring nucleosome during remodeling (Dechassa et al., 2010). Notably, strong DNA translocation could provide a mechanism that underlies both of these proposed modes of nucleosome ejection.

The identification of domains and proteins that regulate DNA translocation efficiency provides an opportunity to test whether transcription factors (Gutierrez et al., 2007), histone variants and/or histone modifications (Ferreira et al., 2007; Goldman et al., 2010) interact with these domains and proteins to augment DNA translocation parameters (Av and/or Cv) to impact remodelling outcomes and efficiency along the sliding-to-ejection continuum. In keeping, ARP modules can bind nucleosomes (Galarneau et al., 2000; Wu et al., 2009), and RSC bears multiple domains that bind histone modifications (Clapier and Cairns, 2014). Finally, we compared RSC/Sth1 to the ISWI remodeler, which slides nucleosomes but lacks ARPs or a Post-HSA domain, and the capacity for ejection. Interestingly, a hyperactive ISWI mutant (termed ISWI2RA) with strong constitutive ATPase activity (Clapier and Cairns, 2012) displayed increased DNA translocation and (remarkably) acquired low ejection capacity (Figure S9). This observation reinforces the notion that ATPase/coupling integration mediates DNA translocation efficiency, and helps explain a major difference between ISWI and RSC: DNA translocation efficiency by ISWI normally extends up to the sliding/ejection boundary, conferring regulated sliding but not ejection - whereas RSC/Sth1 has a broader range of efficiency, enabling regulated sliding and ejection.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Detailed experimental procedures, and genetic screens are provided in the Supplemental Information.

Reagents

RSC complexes were purified from S. cerevisiae strains BCY211 (wild-type), BCY262 (arp9Δ mra Sth1), and BCY3476 (rtt102Δ) harboring integrated RSC2-TAP and plasmid-encoded Sth1-Flag. See Supplemental Information for ARP module reconstitution. Recombinant complexes containing Sth1 protein alone (S), with Arp7/9 (SA), and Rtt102 (SAR) were produced as N-terminal fusions to trigger factor (S only) and the Tet repressor DNA-binding domain, and were purified to homogeneity as monodisperse derivatives. Mononucleosomes and nucleosome arrays were produced using purified Drosophila histones expressed in E. coli BL21-CodonPlus(DE3)RIL, assembled with 200-bp DNA fragments (containing a centrally-located 601 strong-positioning sequence), or with pBluescript plasmid DNA, by salt-dialysis linear gradient.

ATPase assay

ATPase assays were performed at 30°C after 30 min incubation of S/SA/SAR complexes (10 pmol, 0.4µM) with pBluescript plasmid (500 ng), using a colorimetric assay (molybdate-malachite green).

DNA-translocation assays

The DNA-translocation assay measured plasmid supercoils generated by a S/SA/SAR protein complex (50nM) anchored through its TetR fusion to a relaxed (by E. coli topoisomerase I) plasmid DNA containing a single tetO operator sequence. Deproteinized samples were loaded on a 1.3% agarose gel, stained in ethidium bromide, and scanned on a Typhoon Trio (Amersham, GE). Procedures involving optical tweezers are provided in the Supplemental Information.

Nucleosome sliding assay

Nucleosome sliding assays were performed at 30°C using 1:2 enzyme (S/SA/SAR/RSC): substrate molar ratio (10nM:20nM). The reactions were stopped by adding excess competitor pBluescript plasmid DNA, run on a 4.5% (37.5:1) native polyacrylamide gel, stained in ethidium bromide, and scanned on a Typhoon Trio.

Nucleosome ejection assay

S/SA/SAR/RSC protein complexes (1 pmol, 20nM) were incubated with nucleosome arrays (500 ng) at 30°C. Deproteinized samples were resolved by two-dimensional separation on a 1.3% agarose gel, stained in ethidium bromide and scanned on a Typhoon Trio.

Nucleosome Positioning in Vivo

Yeast strains containing an integrated sth1 degron allele (Parnell et al., 2008) were transformed with plasmid-borne methionine-regulatable (MET25 promoter) STH1, sth1L392P, or sth1ΔDL. Cells were fixed with formaldehyde (20 min), quenched with glycine, harvested, rinsed with Tris-buffered saline, and stored at −80C. Mononucleosomes were purified from MNase titrations that generated about 60% mono-, 30% di-, and 10% tri-nucleosomes and prepared for sequencing using Illumina ChIP Tru-Seq kits. Two independent biological replicates were sequenced with 50 bp single-end runs on an Illumina HiSeq 2500 to yield 12–18 million reads.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Actin-related proteins and the P1 domain regulate Sth1 DNA translocation efficiency

The Post-HSA domain regulates Sth1 ATPase activity and DNA translocation speed

A blend of moderate-to-high ATPase activity and efficiency enable nucleosome ejection

Strong upregulation of DNA translocation confers chromatin changes and cell lethality

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH GM60415 to B. Cairns, HHMI (C. Clapier and M. Kasten), CA24014 (core facilities), and NIH GM093341 and Sinsheimer Foundation to Y. Zhang.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

SUPPLEMENTAL INFORMATION

Supplemental Data: Figures S1–S9 and Table S1.

Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

Supplemental References.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

C.R.C.: S/SA/SAR reagents and chromatin substrates, nucleosome ejection system and biochemical assays. M.M.K.: RSC reagents and genetic experiments. T.J.P.: nucleosome sequencing and genomic data analysis. R.V. and H.S.: genetic screens. G.S. and Y.Z.: optical tweezers experiments and analysis. All authors contributed to experimental design. B.R.C. and C.R.C. wrote the paper.

REFERENCES

- Boeger H, Griesenbeck J, Strattan JS, Kornberg RD. Nucleosomes unfold completely at a transcriptionally active promoter. Mol Cell. 2003;11:1587–1598. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00231-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruno M, Flaus A, Stockdale C, Rencurel C, Ferreira H, Owen-Hughes T. Histone H2A/H2B dimer exchange by ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling activities. Mol Cell. 2003;12:1599–1606. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00499-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cairns BR, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Winston F, Kornberg RD. Two actin-related proteins are shared functional components of the chromatin-remodeling complexes RSC and SWI/SNF. Mol Cell. 1998;2:639–651. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80162-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cairns BR, Lorch Y, Li Y, Zhang M, Lacomis L, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Du J, Laurent B, Kornberg RD. RSC, an essential, abundant chromatin-remodeling complex. Cell. 1996;87:1249–1260. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81820-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Conaway RC, Conaway JW. Multiple modes of regulation of the human Ino80 SNF2 ATPase by subunits of the INO80 chromatin-remodeling complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:20497–20502. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1317092110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clapier CR, Cairns BR. Regulation of ISWI involves inhibitory modules antagonized by nucleosomal epitopes. Nature. 2012;492:280–284. doi: 10.1038/nature11625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clapier CR, Cairns BR. Chromatin Remodeling Complexes. In: Workman JL, Abmayr SM, editors. Fundamentals of Chromatin. New York, NY: Springer; 2014. pp. 69–146. [Google Scholar]

- Cote J, Peterson CL, Workman JL. Perturbation of nucleosome core structure by the SWI/SNF complex persists after its detachment, enhancing subsequent transcription factor binding. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:4947–4952. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.9.4947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dechassa ML, Sabri A, Pondugula S, Kassabov SR, Chatterjee N, Kladde MP, Bartholomew B. SWI/SNF has intrinsic nucleosome disassembly activity that is dependent on adjacent nucleosomes. Mol Cell. 2010;38:590–602. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.02.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira H, Somers J, Webster R, Flaus A, Owen-Hughes T. Histone tails and the H3 alphaN helix regulate nucleosome mobility and stability. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:4037–4048. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02229-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flaus A, Martin DM, Barton GJ, Owen-Hughes T. Identification of multiple distinct Snf2 subfamilies with conserved structural motifs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:2887–2905. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galarneau L, Nourani A, Boudreault AA, Zhang Y, Heliot L, Allard S, Savard J, Lane WS, Stillman DJ, Cote J. Multiple links between the NuA4 histone acetyltransferase complex and epigenetic control of transcription. Mol Cell. 2000;5:927–937. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80258-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman JA, Garlick JD, Kingston RE. Chromatin remodeling by imitation switch (ISWI) class ATP-dependent remodelers is stimulated by histone variant H2A.Z. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:4645–4651. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.072348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez JL, Chandy M, Carrozza MJ, Workman JL. Activation domains drive nucleosome eviction by SWI/SNF. Embo J. 2007;26:730–740. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyon JR, Narlikar GJ, Sullivan EK, Kingston RE. Stability of a human SWI-SNF remodeled nucleosomal array. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:1132–1144. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.4.1132-1144.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho L, Crabtree GR. Chromatin remodelling during development. Nature. 2010;463:474–484. doi: 10.1038/nature08911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobsiger J, Hunziker Y, Richmond TJ. Structure of the full-length yeast Arp7-Arp9 heterodimer. Acta crystallographica Section D, Biological crystallography. 2014;70:310–316. doi: 10.1107/S1399004713027417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorch Y, Griesenbeck J, Boeger H, Maier-Davis B, Kornberg RD. Selective removal of promoter nucleosomes by the RSC chromatin-remodeling complex. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2011;18:881–885. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorch Y, Maier-Davis B, Kornberg RD. Chromatin remodeling by nucleosome disassembly in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:3090–3093. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511050103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parnell TJ, Huff JT, Cairns BR. RSC regulates nucleosome positioning at Pol II genes and density at Pol III genes. Embo J. 2008;27:100–110. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson CL, Zhao Y, Chait BT. Subunits of the yeast SWI/SNF complex are members of the actin-related protein (ARP) family. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:23641–23644. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.37.23641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saha A, Wittmeyer J, Cairns BR. Chromatin remodeling by RSC involves ATP-dependent DNA translocation. Genes & development. 2002;16:2120–2134. doi: 10.1101/gad.995002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schubert HL, Wittmeyer J, Kasten MM, Hinata K, Rawling DC, Heroux A, Cairns BR, Hill CP. Structure of an actin-related subcomplex of the SWI/SNF chromatin remodeler. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:3345–3350. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1215379110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen X, Ranallo R, Choi E, Wu C. Involvement of actin-related proteins in ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling. Mol Cell. 2003;12:147–155. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00264-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sirinakis G, Clapier CR, Gao Y, Viswanathan R, Cairns BR, Zhang Y. The RSC chromatin remodelling ATPase translocates DNA with high force and small step size. Embo J. 2011;30:2364–2372. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szerlong H, Hinata K, Viswanathan R, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Cairns BR. The HSA domain binds nuclear actin-related proteins to regulate chromatin-remodeling ATPases. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2008;15:469–476. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turegun B, Kast DJ, Dominguez R. Subunit Rtt102 controls the conformation the Arp7/9 heterodimer and its interactions with nucleotide and the catalytic subunit of SWI/SNF remodelers. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:35758–35768. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.514083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulyanova NP, Schnitzler GR. Human SWI/SNF generates abundant, structurally altered dinucleosomes on polynucleosomal templates. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:11156–11170. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.24.11156-11170.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu WH, Wu CH, Ladurner A, Mizuguchi G, Wei D, Xiao H, Luk E, Ranjan A, Wu C. N terminus of Swr1 binds to histone H2AZ and provides a platform for subunit assembly in the chromatin remodeling complex. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:6200–6207. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M808830200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X, Zaurin R, Beato M, Peterson CL. Swi3p controls SWI/SNF assembly and ATP-dependent H2A–H2B displacement. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2007;14:540–547. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao K, Wang W, Rando OJ, Xue Y, Swiderek K, Kuo A, Crabtree GR. Rapid and phosphoinositol-dependent binding of the SWI/SNF-like BAF complex to chromatin after T lymphocyte receptor signaling. Cell. 1998;95:625–636. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81633-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.