Abstract

Bacterial live-vector vaccines aim to deliver foreign antigens to the immune system and induce protective immune responses, and surface-expressed or secreted antigens are generally more immunogenic than cytoplasmic constructs. We hypothesize that an optimum expression system will use an endogenous export system to avoid the need for large amounts of heterologous DNA encoding additional proteins. Here we describe the cryptic chromosomally encoded 34-kDa cytolysin A hemolysin of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi (ClyA) as a novel export system for the expression of heterologous antigens in the supernatant of attenuated Salmonella serovar Typhi live-vector vaccine strains. We constructed a genetic fusion of ClyA to the reporter green fluorescent protein and showed that in Salmonella serovar Typhi CVD 908-htrA, the fusion protein retains biological activity in both domains and is exported into the supernatant of an exponentially growing live vector in the absence of detectable bacterial lysis. The utility of ClyA for enhancing the immunogenicity of an otherwise problematic antigen was demonstrated by engineering ClyA fused to the domain 4 (D4) moiety of Bacillus anthracis protective antigen (PA). A total of 11 of 15 mice immunized intranasally with Salmonella serovar Typhi exporting the protein fusion manifested fourfold or greater rises in serum anti-PA immunoglobulin G, compared with only 1 of 16 mice immunized with the live vector expressing cytoplasmic D4 (P = 0.0002). In addition, the induction of PA-specific gamma interferon and interleukin 5 responses was observed in splenocytes. This technology offers exceptional versatility for enhancing the immunogenicity of bacterial live-vector vaccines.

Bacterial live vectors for use in humans are attenuated strains that present to the human immune system sufficient foreign (heterologous) antigens from unrelated human pathogens to elicit protective immune responses. Toward this end, we have engineered expression plasmids encoding a plasmid maintenance system that promotes uniform plasmid inheritance while removing plasmidless daughter cells from a growing population of live vectors (16). However, often overlooked in live-vector engineering is the effect that stabilized expression plasmids (and the heterologous antigens that they typically encode) can exert on the fitness of a live vector.

Galen and Levine previously hypothesized (15) that an appropriate balance between levels of immunogenic expression of a given heterologous antigen and minimization of metabolic burden upon the live vector can be achieved through surface expression or secretion of the foreign antigen from the live vector, thereby removing any unintended metabolic influences from high-level synthesis of a foreign cytoplasmic protein; such secretion may, in addition, allow for proper folding of antigens requiring the formation of disulfide bonds, which are not formed in cytoplasmically expressed proteins. A growing body of evidence now confirms that surface expression or antigen export each improves the immunogenicity of foreign antigens expressed in Salmonella live vectors, with immune responses being improved 104-fold in some instances (21) with secreted versus cytoplasmically expressed antigens.

Significant enhancement of the immunogenicity of foreign antigens by live vectors has been obtained with a limited number of strategies. The methods used have included surface display technology based on engineering of the Pseudomonas syringae ice nucleation protein (24) and secretion of antigens via the HlyA type I secretion system of uropathogenic Escherichia coli (18, 47, 49) or via the Salmonella pathogenicity island 1 type III secretion system (43); this type III secretion-mediated approach was recently improved upon by use of heterologous Yersinia outer membrane protein E (YopE) as a carrier for the transport of carboxyl-terminal fusions via the Salmonella pathogenicity island 1 secretion system (42).

Here we describe the development of a new antigen export system engineered from an endogenous cryptic hemolysin (ClyA), encoded by clyA within the chromosome of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi, for the delivery of foreign antigens from the attenuated Salmonella serovar Typhi live-vector vaccine strain CVD 908-htrA. ClyA from Salmonella serovar Typhi was first described by Wallace et al. (52), who also reported the crystal structure for homologous hemolysin HlyE of E. coli. This previously described hemolysin has been variously referred to as ClyA (30, 31), HlyE (1, 52), or SheA (10); to avoid confusion, we refer here to the E. coli hemolysin as HlyE, encoded by hlyE, and to the Salmonella serovar Typhi hemolysin as ClyA, encoded by clyA. In elegant recent studies, Wai et al. (51) demonstrated vesicle-mediated export and assembly of ClyA such that the resulting outer membrane vesicles were larger than normally formed vesicles and contained periplasmic contents entrapped during vesicle release. Such a mechanism for vesicle formation raises the intriguing possibility of engineering ClyA to export from a live vector, via vesicles, heterologous domains that are otherwise potentially toxic to the live vector. These vesicles would also carry immunomodulatory lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and perhaps improve the immunogenicity of an otherwise poorly immunogenic antigen.

We have applied this novel technology in the initial development of a Salmonella serovar Typhi-based vaccine against anthrax. The primary virulence determinant responsible for the clinical effects of infection with Bacillus anthracis is anthrax toxin. Anthrax toxin is actually comprised of two catalytic protein domains, lethal factor and edema factor, which competitively bind to three equivalent binding sites on top of a heptameric ring of 63-kDa cell binding protective antigen (PA63) monomers (5). Aggregate in vitro results obtained with tissue culture monolayers and purified toxin components suggest that upon intoxication of a target cell, this protective antigen (PA) undergoes an acid-induced conformational change which results in translocation of the lethal factor catalytic domain into the cell cytoplasm, followed either by rapid cell death or cytokine release at sublethal levels of intoxication (6). Crystallographic analysis of PA (36) has revealed a four-domain structure in which the eukaryotic cell binding site resides within carboxyl-terminal 16.2-kDa domain 4 (D4) (residues 596 to 735) (50).

Genetic deletion of D4 from the chromosomal locus encoding PA in an otherwise fully virulent B. anthracis strain resulted in a 4-log-unit increase in the 50% lethal dose of the resulting strain. Since mice immunized with spores from this attenuated strain were only partially protected from a spore challenge with 40 50% lethal doses of the fully virulent encapsulated parent strain, it was hypothesized that D4 contains immunodominant epitopes required to induce a strong protective humoral immune response against anthrax toxin (4). Here we report the engineering of a synthetic gene (d4) encoding PA D4 genetically fused in frame to the carboxyl terminus of ClyA (clyA::d4), studies to demonstrate the export of ClyA-D4 into the extracellular medium of live-vector strain CVD 908-htrA, and the effect of export on the immunogenicity of ClyA-D4 versus that of unfused D4 expressed cytoplasmically.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and culture conditions.

All plasmid constructions were recovered in E. coli strain DH5α (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Carlsbad, Calif.). Live-vector Salmonella serovar Typhi CVD 908-htrA is an auxotrophic derivative of wild-type strain Ty2 with deletions in aroC, aroD, and htrA (48). Salmonella serovar Typhi strains used in this work were grown in media supplemented with 2,3-dihydroxybenzoic acid (DHB) (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) (14, 19). Plasmid-bearing strains of CVD 908-htrA were streaked from frozen (−70°C) master stocks on 2× Luria-Bertani agar (solid medium) containing 20 g of Bacto Tryptone, 10 g of Bacto Yeast Extract, and 50 mM NaCl (2×LB50 agar) plus kanamycin at 10 mg/ml or carbenicillin at 50 mg/ml, as appropriate. Plates were incubated at 30°C for 24 to 36 h to obtain isolated colonies ∼2 mm in diameter and to minimize any toxicity of heterologous antigen expression in CVD 908-htrA.

Molecular genetic techniques.

Standard techniques were used for plasmid constructions (44). Unless otherwise noted, native Taq DNA polymerase (Invitrogen Life Technologies) was used in PCRs. Salmonella serovar Typhi strains were prepared for electroporation of recombinant plasmids after being harvested from 2×LB50 broth supplemented with DHB, and electroporation was carried out as previously described (14). Isolated colonies were swabbed on supplemented 2×LB50 agar and incubated at 30°C for 16 h. Frozen master stocks were prepared by harvesting bacteria into SOC medium (Invitrogen Life Technologies) without further supplementation and freezing at −70°C.

(i) Construction of expression plasmids containing oriE1 and ori15A.

The primers used in this study are listed in Table 1, and the essential plasmids created from these primers are listed in Table 2. In general, the expression plasmids were constructed in three phases of increasing complexity. The basic expression replicons containing plasmid maintenance functions were previously described as the pGEN series (16). Further refinements of such plasmids involved improving the clinical acceptability of such plasmids by replacement of β-lactamase genes with kanamycin resistance cassettes to generate the pEXO series detailed here. With the further introduction of putative antigen export systems, the pSEC series was finally constructed.

TABLE 1.

Primers used in construction and testing of ClyA expression plasmids

| Primer | Sequencea | Cassette created | Templateb | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5′-GCTAGCAGCGAACCGGAATTGCCACGGCTGGGGCGCCCTCTGGTAAGGTTGGGAAGCCCTGC-3′ | aphA-5 | pIB279 | 3 |

| 2 | 5′-GCTAGCCCAACCTTTCATAGAAGGCGGCGGTGGAATCGAAATCTCGTGATGGCAG-3′ | aphA-5 | pIB279 | |

| 3 | 5′-GGATCCAAAATAAGGAGGAAAAAAAAATGACTAGTATTTTTGCAGAACAAACTGTAGAGGTAGTTAAAAGCGCGATCGAAACCGCAGATGGGGCATTAGATC-3′ | clyA-tetA | CVD 908-htrA | 43 |

| 4 | 5′-CCTAGGTTATCAGCTAGCGACGTCAGGAACCTCGAAAAGCGTCTTCTTACCATGACGTTGTTGGTATTCATTACAGGTGTTAATCATTTTCTTTGCAGCTC-3′ | clyA-tetA | CVD 908-htrA | |

| 5 | 5′-CACGGTAAGAAGACGCTTTTCGAGGTTCCTGACGTCGCTAGCTGATAACCTAGGTCATGTTAGACAGCTTATCATCGATAAGCTTTAATGCGGTAGT-3′ | tetA | pBR322 | 2 |

| 6 | 5′-AGATCTACTAGTGTCGACGCTAGCTATCAGGTCGAGGTGGCCCGGCTCCATGCACCGCGACGCAACGCG-3′ | tetA | pBR322 | |

| 7 | 5′-CCCGGGATCCTCATGTTTGACAGCTTATCATCGATAAGCTTTAATGCG-3′ | tetA | pBR322 | |

| 8 | 5′-GCGCAGATCTTAATCATCCACAGGAGGCGCTAGCATGAGTAAAGGAGAAGAACTTTTCACTGGAGTTGTCCCAATTCTTG-3′ | gfpuv-tetA | pGEN84 | 15 |

| 9 | 5′-GTGATAAACTACCGCATTAAAGCTTATCGATGATAAGCTGTCAAACATGAGCGCTCTAGAACTAGTTCATTATTTGTAGAGCTCATCCATGCCATGTGTAATCCCAGCAG-3′ | gfpuv-tetA | pGEN84 | |

| 10 | 5′-TCATGTTTGACAGCTTATCATCGATAAGCTTTAATGCGGTAGTTTA-3′ | gfpuv-tetA | pGEN84 | |

| 11 | 5′-TAGTAATGAACTAGTAAACGTTTTCATTATGATCGTAATAACATCGCAGTTGGGGCGGATGAGTCAGTAGTTAAGGAGGCTCATCGTGAAGTAATTAATTCGTC-3′ | d4 | NA | |

| 12 | 5′-CAGTATCTTCAATTTCTACAATATATCCGGATAAGATTTTACGGATATCCTTATCAATATTTAACAATAATCCCTCTGTTGACGAATTAATTACTTCACGATGAGCCTCCTTAA-3′ | |||

| 13 | 5′-TTATCCGGATATATTGTAGAAATTGAAGATACTGAAGGGCTTAAAGAAGTTATCAATGACCGTTATGATATGTTGAATATTTCTAGTTTACGTCAAGATGG-3′ | |||

| 14 | 5′-GCATATACATTTACCTTATAATTCGGATTACTGATATATAACGGTAATTTATCATTATATTTTTTAAAATCGATAAATGTTTTTCCATCTTGACGTAAACTAGAAATATTCAACA-3′ | |||

| 15 | 5′-ATCAGTAATCCGAATTATAAGGTAAATGTATATGCTGTTACTAAAGAAAACACTATTATTAATCCTAGTGAGAATGGGGATACCAGCACCAACGGGATCAAGAAAATTTTAATC-3′ | |||

| 16 | 5′-GTTAGATTTCATTTTTTTTTCCTCCTTATTTTCCTAGGTCATTATCCGATCTCATAGCCTTTTTTAGAAAAGATTAAAATTTTCTTGATCCCGTTGGTGCTGGTATC-3′ |

Relevant restriction sites are designated in bold type (see the text for details); ribosome binding sites and start codons are designated in italic type.

NA, not applicable.

TABLE 2.

Selected plasmids used in this work

| Plasmid | Size (kb) | Relevant genotype | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|---|

| pGEN84 | 4.5 | oriE1 gfpuv bla hok-sok par | 16 |

| pGEN91 | 3.5 | ori15A gfpuv bla | 16 |

| pGEN222 | 6.2 | ori15A gfpuv bla hok-sok par parA | 16 |

| pEXO1 | 4.4 | oriE1 gfpuv aph hok-sok par | This work |

| pEXO2 | 4.2 | ori15A tetA bla | This work |

| pEXO3 | 6.0 | ori15A gfpuv aph hok-sok par parA | This work |

| pEXO4 | 6.6 | ori15A tetA aph hok-sok par parA | This work |

| pSEC84 | 6.3 | oriE1 clyA aph hok-sok par parA | This work |

| pSEC91 | 7.6 | ori15A clyA tetA aph hok-sok par parA | This work |

| pSEC91D4-c | 5.8 | ori15A d4 aph hok-sok par parA | This work |

| pSEC91D4 | 6.7 | ori15A clyA::d4 aph hok-sok par parA | This work |

The kanamycin resistance cassette for the pEXO series was encoded by a modified aphA-5 gene engineered to express reduced levels of resistance to the aminoglycosides neomycin and kanamycin (46). PCR was carried out with primers 1 and 2 and the template pIB279 (3) to generate a 1,046-bp product in which the native promoter strength was reduced by an increase in the intervening sequence between the −35 and −10 regions from 17 to 19 bp. The resulting NheI cassette was used to replace the 1,181-bp XbaI-SpeI bla cassette of pGEN84 (Table 2), generating pEXO1, and the identical cassette of pGEN222, generating pEXO3. The expected copy numbers of pEXO1 and pEXO3 are approximately 60 and 15 copies per chromosomal equivalent, respectively.

(ii) Cloning of the Salmonella serovar Typhi clyA gene.

Since the development of the export system described here was begun prior to publication of the Ty2 genome sequence (11) or the initial description of a Salmonella serovar Typhi clyA allele (29), the identification of clyA was accomplished by BLASTN analysis of the Salmonella serovar Typhi CT18 genome sequence (32), available from the Sanger Centre (http://www.sanger.ac.uk/Projects/S_typhi/blast_server.shtml), by use of the DNA sequence of E. coli hlyE (GenBank accession number U57430). A promoterless 2,252-bp clyA-tetA genetic cassette was synthesized by overlapping PCR as previously described (16) with primers 3 and 4 and chromosomal template DNA from CVD 908-htrA and with primers 5 and 6 and a template derived from pBR322; clyA was engineered to contain an in-frame NheI site penultimate to the tandem TGA TAA stop codons. The desired product was recovered in pGEM-T (Promega, Madison, Wis.) and used to transform E. coli, and 33 CFU were screened for hemolytic activity; of 2 positive isolates, 1 was chosen for further use and was designated pGEM-TclyA.

To facilitate subcloning of the clyA-tetA cassette, an additional tetA cassette was synthesized with primers 6 and 7 and a pBR322 derivative to generate a 1,309-bp product; this product was inserted as an SmaI-BglII fragment into pGEN91 that had been cleaved with EcoRV and BamHI to create pEXO2. The resulting PompC-tetA cassette then was excised as an EcoRI-SpeI fragment and inserted into EcoRI-NheI-digested pEXO3 to yield pEXO4. Finally, the clyA-tetA fragment was excised from pGEM-TclyA as a BamHI fragment and inserted into pEXO4 that had been digested with BamHI to regenerate tetA and create pSEC91. To generate isogenic clyA expression plasmids with the expected copy numbers of 60 and 15 copies per chromosomal equivalent, the clyA cassette was cleaved from pSEC91 (∼15 copies) as an XhoI-AvrII fragment and ligated into pEXO1 that had been digested with XhoI-AvrII to generate pSEC84 (∼60 copies); as pSEC84 and pSEC91 are so similar in structure, only pSEC84 is shown in Fig. 1.

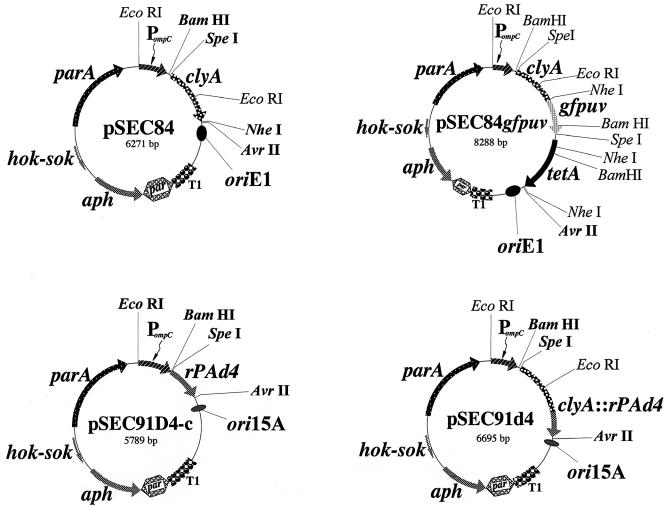

FIG. 1.

Genetic maps of isogenic expression plasmids encoding ClyA and ClyA fusion proteins; a list of the plasmids used in this work is shown in Table 2. Restriction sites shown in bold represent unique sites in the expression plasmids. Abbreviations: PompC, modified osmotically controlled ompC promoter from E. coli; clyA, gene encoding ClyA from Salmonella serovar Typhi; gfpuv, gene encoding prokaryotic codon-optimized GFPuv; d4, gene encoding D4 of anthrax toxin PA; clyA::d4, gene encoding D4 of PA fused to the carboxyl terminus of ClyA; tetA, gene encoding the tetracycline efflux protein from pBR322; aph, gene encoding the aminoglycoside 3′-phosphotransferase conferring resistance to kanamycin; oriE1, origin of replication from pBR322 providing an expected expression plasmid copy number of ∼60 per chromosomal equivalent; ori15A, origin of replication from p15A providing an expected copy number of ∼15 per chromosomal equivalent; T1, transcriptional terminator from the rrnB rRNA operon of E. coli; hok-sok, postsegregational killing locus from the multiple antibiotic resistance R plasmid pR1; and parA, gene encoding the active partitioning system from pR1.

(iii) Construction of ClyA protein fusions.

All fusions reported here were engineered as genetic fusions of SpeI or NheI cassettes inserted in frame into the NheI site adjacent to the tandem stop codons at the clyA 3′ terminus; the DNA sequence of the intended fusion junctions was confirmed by use of the sequencing primer 5′-CGATGCGGCAAAATTGAAATTAGCCACTGA-3′, which hybridizes 172 bases upstream of the engineered NheI site within clyA.

The clyA::gfpuv fusion was constructed after synthesis of a 2,069-bp gfpuv-tetA cassette by overlapping PCR with primers 8 and 9 and the template pGEN84 to generate the reporter green fluorescent protein (GFPuv) gene (gfpuv) and with primers 6 and 10 and a pBR322 derivative to generate tetA. The gfpuv-tetA cassette was engineered to contain a consensus ribosome binding site 8 bp upstream of the GFPuv ATG start codon, such that when the PCR product was recovered in pGEM-T, tetracycline-resistant colonies could be quickly screened to confirm native GFP fluorescence prior to fusion with ClyA. The desired gfpuv-tetA cassette was cleaved by partial digestion with NheI to create a 2,017-bp fragment, which was inserted into identically cleaved pSEC84 to create pSEC84gfpuv. After electroporation into CVD 908-htrA, colonies were screened for the retention of both hemolytic activity and fluorescence prior to Western immunoblot analysis.

The sequence encoding the D4 allele (d4) used for codon optimization was taken from the published sequence of B. anthracis PA (GenBank accession number M22589) (55) and modeled after a synthetic gene reported to encode a domain which retains the ability to bind the anthrax toxin receptor of HeLa cells (22). However, no attempt was made to fully optimize codon usage; rather, only rare arginine (CGG and AGA) and isoleucine (ATA) codons were removed. In addition, unique BspEI and ClaI sites were engineered into the open reading frame such that if point mutations arose in nonoverlapping regions of independent clones, then restriction cassettes could be reassembled to generate the desired sequence.

d4 was constructed in a two-step PCR with six overlapping oligonucleotides (primers 11 to 16) (Table 1) with at least 30-base regions of complementarity between successive oligonucleotides. Reactions were carried out with 50-μl volumes containing 1 U of Vent DNA polymerase (New England BioLabs, Beverly, Mass.) in the presence of primers as recommended by the manufacturer. PCR parameters were as follows: 1 cycle at 94°C for 1 min, 30 cycles at 94°C for 30 s, 55°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 1.5 min, and 1 cycle at 72°C for 5 min. Primer sets 11 and 12, 13 and 14, and 15 and 16 were combined in reactions to synthesize fragments of 184 bp (fragment A), 185 bp (fragment B), and 184 bp (fragment C), respectively. Fragments of the expected sizes were gel purified prior to use in the next stage of assembly. While attempts to fuse fragments A and B in PCRs yielded smeared products that were not pursued further, combining fragments B and C yielded fusion products with the expected size of 334 bp (fragment D). Therefore, fragments A and D were recovered in pCR-Blunt II-TOPO (Invitrogen Life Technologies), and the expected DNA sequence was verified. The final D4 allele (d4) was assembled within pCR-Blunt II-TOPO by removal of carboxyl-terminal fragment D of d4 as a BspEI-ApaI 392-bp cassette and insertion into an identically cleaved plasmid containing fragment A. The sequence of the resulting d4 product was verified, and the product finally was inserted as a 438-bp SpeI-AvrII cassette into pSEC91 that had been cleaved with SpeI-NheI to create the unfused d4 construct in pSEC91D4-c or into pSEC91 that had been cleaved only with NheI to generate the desired clyA::d4 gene fusion in pSEC91D4 (Fig. 1).

Phenotypic screening and immunoblot analysis.

Screening for hemolytic activity was performed on freshly prepared 2×LB50 agar containing DHB plus an appropriate selection antibiotic and 5% sheep blood. Isolated colonies were first recovered from frozen stocks streaked on supplemented 2×LB50 and incubated at 37°C for 36 h. Colonies then were either patched or streaked for isolation on blood medium and incubated at 37°C for 24 to 48 h to detect zones of red blood cell hemolysis.

Western immunoblot analysis was carried out as previously described (28), with care taken to analyze samples from cultures grown at 30°C to optical densities at 600 nm (OD600) that did not exceed 1.0. The locations of the fusion proteins were examined by use of semiquantitative cell fractionation analysis as previously described (45). Immunoblots were developed by use of an ECL+Plus detection system (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, N.J.), and blots were exposed to Kodak X-OMAT XAR-2 film.

Detection of GFPuv was carried out by use of a murine GFP primary antibody (BD Biosciences/Clontech, Palo Alto, Calif.) and a peroxidase-labeled affinity-purified goat anti-mouse secondary antibody (Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories, Inc., Gaithersburg, Md.). To estimate the amount of cell lysis possibly contributing to the release of ClyA-GFPuv fusions into supernatants, contamination of supernatants with cytoplasmic protein GroEL was directly detected by use of peroxidase-conjugated anti-E. coli GroEL rabbit antibody (Sigma).

Detection of D4 and ClyA-D4 fusions was accomplished by use of murine D4 antiserum. Antiserum was raised in mice immunized with unfused D4 purified from pSEC91D4-c lysates fractionated on sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-15% polyacrylamide gels and lightly stained with BluPrint (Invitrogen Life Technologies) to identify the expected 16.5-kDa protein. Excised material from four preparative gels (total volume, ∼800 ml) was homogenized in 1.2 ml of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (total volume, ∼2.0 ml) and used directly for immunization without adjuvant of five BALB/c mice; ∼400 ml/mouse was injected intraperitoneally. Serum samples from mice were collected by retro-orbital bleeding 4 weeks later, and the anti-PA63 geometric mean titer (GMT) of pooled sera was quantitated (as described below) to be 100,000. Prior to use in Western immunoblot analysis, pooled sera were diluted 1:20,000 in Tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween 20 and 1% blotting-grade nonfat dry milk and adsorbed overnight at room temperature with CVD 908-htrA. Following quantitative removal of bacteria, the remaining sera were used directly for immunoblotting.

For direct comparison of total heterologous antigens present in whole-cell lysates of strains expressing D4 protein fusions, 0.1 OD600 units of bacteria were loaded per lane, corresponding to viable counts of 1.65 × 108 for CVD 908-htrA, 5.36 × 107 for CVD 908-htrA(pSEC91D4), and 5.1 × 107 for CVD 908-htrA(pSEC91D4-c). The original Coomassie brilliant blue-stained gel then was scanned as a TIFF file by use of a Hewlett-Packard ScanJet 6300C and analyzed by use of Phoretix 1D version 4.0 gel analysis software. The absolute intensities of two independent and corresponding bands [CVD 908-htrA(pSEC91D4) lysate and CVD 908-htrA(pSEC91D4-c) lysate] were determined and used to develop a correction factor of 1.169 to account for slightly less bacterial host protein from CVD 908-htrA(pSEC91D4) than from CVD 908-htrA(pSEC91D4-c). The absolute intensities of the heterologous protein bands then were determined and, after correction for intensity, it was determined that the intensity of the foreign protein in CVD 908-htrA(pSEC91D4-c) lysates was 29.2% greater than the intensity of the foreign protein detected in CVD 908-htrA(pSEC91D4) lysates; that these foreign species corresponded to D4-containing proteins was confirmed by Western immunoblot analysis with D4-specific antiserum.

Vaccination of mice.

Groups of 10 female BALB/c mice (Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, Mass.), aged 6 to 8 weeks, were inoculated via the intranasal route (14, 33-35, 37) by placing 10 μl of a vaccine suspension containing 1 × 109 to 3 × 109 CFU into the right and left nares on days 0 and 28. Serum samples from mice were collected by retro-orbital bleeding on days 0, 28, and 56. The methods used in these animal studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Maryland, Baltimore.

Measurement of antibodies in mouse sera.

Total serum IgG antibodies against Salmonella serovar Typhi LPS and B. anthracis PA63 were measured by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Briefly, 96-well plates were coated with 100 μl of Salmonella serovar Typhi LPS (Sigma) at 10 μg/ml or purified PA63 (lot 1744A1; List Biological Laboratories, Campbell, Calif.) at 5 μg/ml in carbonate buffer (pH 9) and blocked overnight with 10% milk (Nestle USA Inc., Glendale, Calif) in PBS. After each incubation, plates were washed with PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20 (PBST). To determine endpoint titers, sera were tested in serial twofold dilutions in 10% milk in PBST (PBSTM). Specific antibodies were detected with goat anti-mouse IgG-horseradish peroxidase conjugate (Roche Diagnostics Corporation, Indianapolis, Ind.) diluted 1:1,000 in PBSTM. The substrate solution used was TMB microwell peroxidase (Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories). After 15 min of incubation, the reaction was stopped by the addition of 100 μl of 1 M H3PO4, and the OD450 was measured with an ELISA reader (Multiskan Ascent; Thermo Labsystem, Helsinki, Finland). Sera were run in duplicate; negative and positive controls were included in each assay. Titers were calculated from linear regression curves as the inverse of the serum dilution that produced an optical density of 0.2 unit above the blank and were expressed in ELISA units per milliliter.

Measurement of the frequencies of T cells producing IFN-γ and IL-5.

Spleens were harvested 6 weeks after the boost. Single-cell suspensions were prepared as follows. Spleens were homogenized, filtered through sterile gauze, and washed with RPMI medium. Erythrocytes were eliminated by incubating cells with 1 ml (per spleen) of lysis buffer (Sigma) on ice for 10 min. Cells then were washed and resuspended in RPMI medium containing 2 mM l-glutamine, 10 mM HEPES, 50 μg of gentamicin/ml, and 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (Gibco, Grand Island, N.Y.) (complete medium). PA-specific cytokine responses were measured by ELISPOT. Briefly, 96-well nitrocellulose plates (Multiscreen-HA; Millipore, Bedford, Mass.) were coated with 5 μg of anti-mouse gamma interferon (IFN-γ) or interleukin 5 (IL-5) (Pharmingen, San Diego, Calif.)/ml overnight at 4°C. Plates then were washed with RPMI medium and blocked with complete medium for 2 h at 37°C. Splenocytes were incubated in serial dilutions (1.5 × 106 to 3.75 × 105 cells/well) with 10 μg of recombinant PA83 (kindly provided by Nicola Walker, Defence Science and Technology Laboratory Porton Down, Salisbury, United Kingdom)/ml for 40 h at 37°C in 5% CO2. Cells also were incubated with medium alone and phytohemagglutinin (Sigma) at 10 μg/ml as controls. Plates then were washed with PBST and incubated with biotin-labeled anti-IFN-γ or anti-IL-5 (Pharmingen) for 2 h at 37°C. Wells were washed and incubated with 100 μl of streptavidin-peroxidase (diluted 1:400 in PBS) for 1 h at 37°C. After washes, 50 μl of TrueBlue peroxidase substrate (Kirkergaard & Perry Laboratories) was added. Plates were incubated for 5 to 10 min at room temperature in the dark and rinsed with tap water. The numbers of spots corresponding to IFN-γ- or IL-5-secreting cells were determined by use of a stereomicroscope. The results are reported as mean spot-forming cells per 106 cells in replicate wells after subtraction of spot-forming cells in wells containing medium alone.

Statistical analysis.

Antibody titers before immunization and after each dose were compared by use of the t test and the Mann-Whitney rank-sum test (when the normality test failed). The PA-specific IFN-γ and IL-5 responses of the experimental and control groups were compared by use of the Hold-Sidak test (multiple comparisons). A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed with Sigma Stat 3.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Ill).

RESULTS

Cloning of Salmonella serovar Typhi clyA.

With data available at the start of this work, the identification of clyA was accomplished by use of BLASTN analysis of the Salmonella serovar Typhi strain CT18 genome sequence and the DNA sequence available for E. coli hlyE. The CT18 clyA open reading frame was identified as a 912-bp sequence predicted to encode a 303-residue protein that has a molecular mass of 33.8 kDa and that is 89.4% identical to E. coli HlyE at the amino acid level. A comparison of the CT18 clyA locus with the recently available Ty2 genome sequence revealed 100% identity at the DNA sequence level within a 3-kb region spanning clyA, as described by Oscarrsson et al. (29) in a comparison of Salmonella serovar Typhi strain S2369/96 and CT18 in this region.

Based on the identification of Salmonella serovar Typhi clyA, primers were designed for PCR amplification of a promoterless genetic cassette encoding ClyA and into which an optimized ribosome binding site was engineered 5′ proximal to the ATG start codon. To facilitate recovery, overlapping PCRs were used to create a 2,252-bp clyA-tetA fragment, which was inserted into cloning vector pGEM-T; the resulting pGEM-TclyA construct was recovered in E. coli DH5α. Recombinant clones were screened on solid agar medium containing sheep red blood cells, and several colonies which produced clear halos of hemolysis were immediately identified. This observation strongly suggested that if clyA required accessory proteins for translocation out of the bacterium, then these proteins were apparently common to both Salmonella serovar Typhi and E. coli.

Construction of a carboxyl-terminal fusion of test antigen GFPuv to ClyA.

Using random mutagenesis with TnphoA, Wyborn et al. previously confirmed that the carboxyl terminus of Salmonella serovar Typhi ClyA is not required for transport out of the cytoplasm of E. coli (56). Based on this observation, we chose to test the ability of ClyA to export passenger domains fused to the carboxyl terminus of the protein and to verify the presence of ClyA fusion products in the supernatants of exponentially growing CVD 908-htrA cultures. To this end, clyA was inserted as an XhoI-AvrII cassette into a replicon derived from pBR322 to create pSEC84, with an expected copy number of 60 copies per chromosomal equivalent (Fig. 1). After electroporation, the resulting CVD 908-htrA(pSEC84) construct was screened on blood agar plates and confirmed to retain hemolytic activity. We then constructed a genetic fusion of clyA to the GFPuv gene (gfpuv), creating the clyA::gfpuv cassette of pSEC84gfpuv (Fig. 1). After introduction of pSEC84gfpuv into CVD 908-htrA, CVD 908-htrA(pSEC84gfpuv) was screened for the retention of hemolytic activity and confirmed to be hemolytic but to have reduced fluorescence compared to that seen with cytoplasmically expressed GFPuv (data not shown).

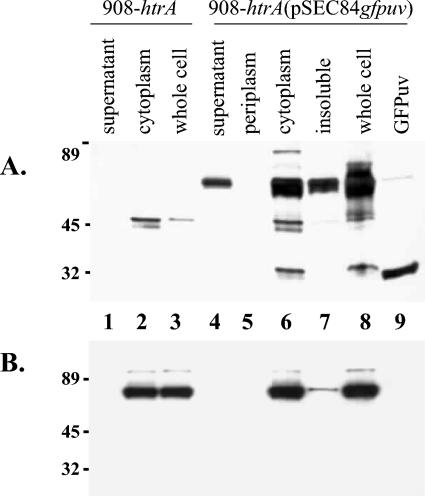

We examined the export of ClyA-GFPuv into culture supernatants by Western immunoblot analysis with anti-GFP antibody. A significant amount of the expected 61-kDa fusion protein was detected in 250 μl of trichloroacetic acid-precipitated supernatant fractions from CVD 908-htrA(pSEC84gfpuv) (Fig. 2A, lane 4) but was not observed in supernatant fractions from CVD 908-htrA (lane 1); an irrelevant cross-reacting species of approximately 45 kDa was also detected in cytoplasmic and whole-cell fractions from CVD 908-htrA (lanes 2 and 3) as well as in cytoplasmic and whole-cell fractions from CVD 908-htrA(pSEC84gfpuv) (lanes 6 and 8). Interestingly, the results shown in Fig. 2A, lane 5, suggested that little if any ClyA-GFPuv was recovered from the periplasmic space of CVD 908-htrA(pSEC84gfpuv).

FIG. 2.

Western immunoblot analysis of bacterial cell fractions from either CVD 908-htrA (lanes 1 to 3) or CVD 908-htrA(pSEC84gfpuv) (lanes 4 to 8). Cell fractions analyzed are shown above the lanes; lane 9 contains 50 ng of GFPuv. Numbers at left indicate kilodaltons. Membranes with identical samples were probed with antibodies specific for GFPuv (A) or E. coli GroEL (B). Immunoblots were scanned as high-resolution TIFF files, and image contrast was improved by use of Adobe Photoshop 6.0.

If autolysis of the live vector is significantly involved in the release of ClyA-GFPuv from CVD 908-htrA, then exclusively cytoplasmic proteins should be detected in supernatants containing ClyA-GFPuv. To examine this possibility, the samples analyzed with anti-GFP antibody were also examined in a separate blotting experiment with peroxidase-conjugated antibody specific for cytoplasmic protein GroEL. As shown in Fig. 2B, GroEL was detected in all cytoplasmic and whole-cell lysate fractions from both CVD 908-htrA and CVD 908-htrA(pSEC84gfpuv), as expected. However, no GroEL was detected in supernatant fractions from either strain. We conclude that the export of ClyA-GFPuv occurs efficiently and in the absence of significant levels of autolysis in actively growing cultures of CVD 908-htrA(pSEC84gfpuv).

Construction and expression of ClyA fused to truncated PA.

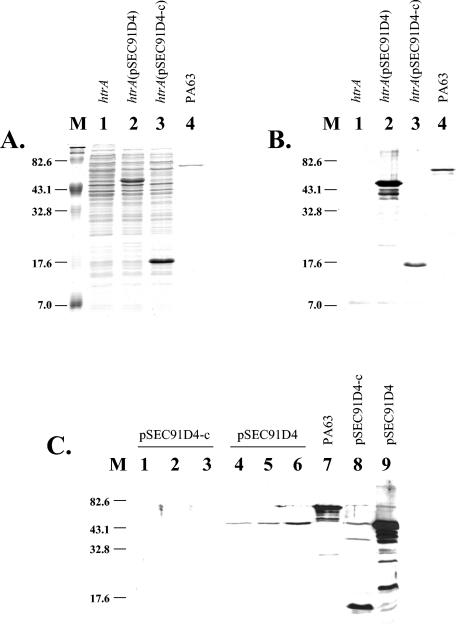

To investigate the versatility of ClyA as a fusion partner for the export of heterologous antigens to possibly improve immunogenicity, we examined the ability of ClyA to export the candidate vaccine antigen D4 from the carboxyl terminus of the PA moiety of B. anthracis toxin. To improve the likelihood of achieving a sufficiently high level of expression of the ClyA-D4 fusion protein, we engineered a synthetic d4 allele in which rare arginine and isoleucine codons were removed. However, we did not completely reengineer this open reading frame to consist only of codons corresponding to the most frequently used Salmonella tRNAs, lest we inadvertently cause metabolic toxicity associated with the overexpression of D4. The resulting synthetic cassette contained an open reading frame encoding a D4 protein with 144 residues and expected molecular masses of 16.5 kDa when expressed from pSEC91D4-c within the cytoplasm and 50.2 kDa when encoded by pSEC91D4.

After repeated attempts to insert a 438-bp SpeI-AvrII d4 cassette into the higher-copy-number expression plasmid pSEC84 (∼60 copies per chromosomal equivalent) failed, we successfully inserted the cassette into lower-copy-number pSEC91 (∼15 copies per chromosomal equivalent) that had been cleaved with NheI to generate the desired clyA::d4 gene fusion in pSEC91D4 (Fig. 1). To ensure a strict comparison and analysis of the immunogenicity of exported D4 versus cytoplasmic D4, the same SpeI-AvrII d4 cassette was also inserted into pSEC91 that had been cleaved with SpeI-NheI to generate pSEC91D4-c (Fig. 1). The expected DNA sequences of the resulting constructs were confirmed by DNA sequence analysis. After the introduction of pSEC91D4 and pSEC91D4-c into CVD 908-htrA by electroporation, we examined the expression of D4. Excellent expression of D4 was observed when whole-cell lysates from both CVD 908-htrA(pSEC91D4) and CVD 908-htrA(pSEC91D4-c) were separated on SDS-polyacrylamide gels and stained with Coomassie brilliant blue dye (Fig. 3A, lanes 2 and 3, respectively). This result was confirmed by Western immunoblot analysis with anti-D4 antiserum raised to gel-purified D4 as described in Materials and Methods (Fig. 3B, lanes 2 and 3). Immunoblot analysis of culture supernatants from both exponentially growing and stationary overnight cultures of CVD 908-htrA(pSEC91D4) indicated the export of ClyA-D4 in the absence of significant cell lysis, since cultures of CVD 908-htrA(pSEC91D4-c) grown under identical conditions did not result in the detection of cytoplasmic D4 in culture supernatants (Fig. 3C, lanes 4 to 6 versus lanes 1 to 3). As expected, no protein was recognized by antiserum in whole-cell lysates from CVD 908-htrA (Fig. 3B, lane 1).

FIG. 3.

(A) Coomassie brilliant blue-stained SDS-polyacrylamide gel of whole-cell lysates from either CVD 908-htrA (lane 1), CVD 908-htrA(pSEC91D4) (lane 2), or CVD 908-htrA(pSEC91D4-c) (lane 3); lane 4 contains 0.3 μg of purified PA63. (B) Western immunoblot analysis of whole-cell lysates from either CVD 908-htrA (lane 1), CVD 908-htrA(pSEC91D4) (lane 2), or CVD 908-htrA(pSEC91D4-c) (lane 3); lane 4 contains 0.3 μg of purified PA63. Membranes were probed with murine polyclonal antiserum raised against D4 as described in Materials and Methods. The expected molecular mass of D4 expressed within the cytoplasm was 16.5 kDa; the expected molecular mass of D4 expressed as a ClyA-D4 fusion protein was 50.2 kDa. Immunoblots were scanned as high-resolution TIFF files, and image contrast was improved by use of Adobe Photoshop 6.0. (C) Western immunoblot analysis of whole-cell lysates and supernatants from either CVD 908-htrA(pSEC91D4-c) (lanes 1 to 3 and 8) or CVD 908-htrA(pSEC91D4) (lanes 4 to 6 and 9); lane 7 contains 0.5 μg of purified PA63. Supernatants were harvested from CVD 908-htrA(pSEC91D4-c) cultures grown to OD600s of 0.54, 0.95, and 1.65 (lanes 1 to 3, respectively) and from CVD 908-htrA(pSEC91D4) cultures grown to OD600s of 0.53, 0.92, and 1.47 (lanes 4 to 6, respectively). Immunoblots were analyzed as described for panel B. Lanes M in all panels contain molecular mass markers (in kilodaltons).

Immunogenicity of exported ClyA-D4.

We assessed the immunogenicity of exported versus cytoplasmically expressed D4 by using the murine intranasal model of immunogenicity. Mice were randomly assorted and immunized with two doses of the live-vector CVD 908-htrA constructs on days 0 and 28. As shown in Table 3, 11 of 15 mice immunized with two doses of CVD 908-htrA(pSEC91D4), in which D4 was engineered for extracellular presentation to the immune system, exhibited seroconversion, with a peak anti-PA63 geometric mean titer (GMT) of 254. In contrast, only 1 of 16 mice immunized with the cytoplasmic expression construct manifested seroconversion (P = 0.0002); responses in the latter group of mice differed little from those in controls (P = 0.347). As expected, all mice immunized with CVD 908-htrA alone, CVD 908-htrA(pSEC91D4-c), or CVD 908-htrA(pSEC91D4) mounted strong antibody responses against Salmonella serovar Typhi LPS (Table 3). However, we noted a trend toward lower titers in mice that received CVD 908-htrA(pSEC91D4-c) than in those that received CVD 908-htrA alone (P = 0.093) or CVD 908-htrA(pSEC91D4) (P = 0.158).

TABLE 3.

Anti-PA63 or anti-Salmonella serovar Typhi LPS IgG GMTsa

| Strain | Time (wk) | Vaccine dose | Results for:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anti-PA63

|

Anti-Salmonella LPS

|

|||||

| Seroconversionb | GMTc (range) | Seroconversionb | GMTc (range) | |||

| CVD 908-htrA | 0 | Priming | 25 (25) | 25 (25) | ||

| 4 | Boost | 25 (25) | 167 (25-2,264) | |||

| 8 | 0/15 | 25 (25) A | 15/15 | 3,245 (360-43,213) B | ||

| CVD 908-htrA(pSEC91D4) | 0 | Priming | 25 (25) | 25 (25) | ||

| 4 | Boost | 27 (25-70) | 124 (25-787) | |||

| 8 | 11/15 C | 254 (25-15,299) D | 15/15 | 3,014 (131-42,756) E | ||

| CVD 908-htrA(pSEC91D4-c) | 0 | Priming | 25 (25) | 25 | ||

| 4 | Boost | 29 (25-116) | 66 (25-584) | |||

| 8 | 1/16 F | 34 (25-809) G | 15/16 | 1,297 (49-12,675) H | ||

Mice were immunized intranasally with 109 CFU in a 10-μl volume. Sera were collected 1 day prior to administration of the priming and booster doses as well as 4 weeks after the boost. Uppercase letters following data are used to indicate groups compared to generate the following P values: C versus F, P < 0.0002; D versus A, P < 0.001; G versus A, P = 0.347; D versus G, P = 0.002; E versus B, P = 0.921; H versus B, P = 0.093; and E versus H, P = 0.158.

Number of seroconverting mice/number of immunized mice.

From twofold serial dilutions starting at 1:50.

We also investigated whether Salmonella expressing PA could elicit cell-mediated immunity and whether the protein export system would influence the outcome of T-cell responses in comparison with cytoplasmic expression. The frequencies of IFN-γ- and IL-5-secreting cells in spleens from mice immunized with CVD 908-htrA alone, CVD 908-htrA(pSEC91D4), or CVD 908-htrA(pSEC91D4-c) were measured by ELISPOT upon in vitro stimulation with recombinant PA83. The results are shown in Table 4. Mice that received CVD 908-htrA(pSEC91D4) and CVD 908-htrA(pSEC91D4-c) showed IFN-γ responses that were significantly higher than those of mice in the control group, which received CVD 908-htrA alone (P = 0.008 and P = 0.019, respectively), as well as superior IL-5 responses (P = 0.015 and P = 0.040, respectively). Mice that received CVD 908-htrA(pSEC91D4) exhibited slightly higher frequencies of both IFN-γ- and IL-5-secreting cells than did mice immunized with CVD 908-htrA(pSEC91D4-c), although the difference was not statistically significant.

TABLE 4.

Frequency of PA-specific T cells producing IFN-γ and IL-5a

| Strain | Results for:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IFN-γ

|

IL-5

|

|||

| SFC/106 (range) | SD | SFC/106 (range) | SD | |

| CVD 908-htrA | 9.6 (8.6-10.6) A | 1.4 | 3 (2.6-3.3) B | 1.9 |

| CVD 908-htrA(pSEC91D4) | 29 (26-35.3) C | 5.1 | 9.3 (8-10.6) D | 1.9 |

| CVD 908-htrA(pSEC91D4-c) | 25.5 (18-30) E | 1.4 | 7.3 (6.6-8) F | 0.9 |

To measure PA-specific T-cell responses induced by Salmonella live-vector vaccines, mice were immunized intranasally with CVD 908-htrA alone (control) or carrying plasmid pSEC91D4 or pSEC91D4-c encoding the PA D4 fragment. Spleens were harvested 6 weeks after the boost. Specific IFN-γ and IL-5 responses were measured by ELISPOT. Data are reported as the mean frequency of IFN-γ- or IL-5-secreting spot-forming cells (SFC)/106 splenocytes and standard deviation for replicate wells. Uppercase letters following data are used to indicate groups compared to generate the following P values: A versus C, P = 0.008; A versus E, P = 0.019; B versus D, P = 0.015; and B versus F, P = 0.040.

DISCUSSION

It has been suggested that the metabolic burden imposed on a bacterial live-vector vaccine strain can be diminished, while the immunogenicity of a foreign antigen is increased, if the antigen can be exported from the live vector (15). We hypothesized that a simple but efficient antigen export system might be derived from an endogenous export system, thereby avoiding the need for large amounts of heterologous DNA encoding additional proteins. However, the system chosen for modification must not be critical for cell survival within appropriate immunological niches, lest the modification diminish or even remove natural function, thereby paradoxically lowering the desired immune responses to both the live vector and heterologous antigen(s). In an attempt to strike an appropriate balance between sufficient foreign antigen expression to elicit immunogenicity and minimization of metabolic burden upon the live vector, we report the first genetic engineering of the cryptic hemolysin ClyA from Salmonella serovar Typhi Ty2 to export heterologous and potentially toxic antigen domains out of the attenuated vaccine strain CVD 908-htrA and into the surrounding medium.

When we initiated the exploration of ClyA as a vehicle for exporting foreign antigen domains, little was known regarding the manner in which ClyA homologs are exported from a bacterium. del Castillo et al. (10) described the growth-phase-dependent secretion of hemolytic activity, which peaked during mid-log phase and vanished at the onset of stationary phase. Ludwig and colleagues (27) reported that secretion of this cryptic hemolysin was accompanied by the leakage of periplasmically confined proteins but was not accompanied by the loss of cytoplasmic proteins, arguing against outright cell lysis for the release of HlyE. In addition, compared to the sequence encoded by hlyE, N-terminal sequencing of secreted HlyE revealed that HlyE is not N-terminally processed during transport. The mode of cellular export of these hemolysins was recently described by Wai et al. (51), who demonstrated vesicle-mediated export of ClyA from both E. coli and Salmonella serovar Typhi. Notably, the resulting outer membrane vesicles containing ClyA appeared to be at least five times larger than normally formed vesicles and contained periplasmic contents entrapped during vesicle release.

For the initial test of the ability to export passenger proteins, we fused the carboxyl terminus of ClyA to GFPuv and detected the expected fusion protein in culture supernatants using Western immunoblot analysis (Fig. 2). Identical samples analyzed with an antibody specific for cytoplasmically expressed GroEL showed that GroEL was not detected in supernatants in which ClyA-GFPuv was present. Our success with ClyA carboxyl-terminal fusions complements the observations of del Castillo et al. (9), who reported that carboxyl-terminal fusions of HlyE (the E. coli homolog of ClyA) to enzymatically active β-lactamase were exported at levels twofold higher than those of amino-terminal fusions; these authors also reported the presence of periplasmic alkaline phosphatase activity in supernatants in the absence of detectable cell lysis or loss of cell viability. Taken together, these data suggest that ClyA may represent a simple yet highly versatile vehicle for the export of foreign antigen domains from a bacterial live vector. We chose to apply this novel technology to the initial development of a Salmonella serovar Typhi-based vaccine against anthrax.

It is now well documented that immunization of rodents, rabbits, and nonhuman primates with vaccines containing PA confers protective immunity to otherwise highly lethal B. anthracis aerosol spore challenge (12, 20, 38, 39). It was also recently established that in rabbits, anti-PA IgG antibodies as well as toxin-neutralizing antibodies constitute serological correlates of protection against aerosol anthrax challenge (25, 38). Interestingly, antibodies raised against PA also display antispore activity (54), with enhanced phagocytosis and intracellular killing of spores by macrophages (53).

Delivery of PA83 by attenuated Salmonella live vectors was first attempted with high-copy-number nonstabilized expression plasmids. These constructs proved to be unstable in mice and conferred low levels of protection against spore challenge even when mice were given antibiotics to improve the retention of expression plasmids by the live vector (7, 8). Integration of the gene encoding PA83 into the chromosome of Salmonella successfully resolved the genetic instability problem. This modification, in addition to exporting PA83 from the live vector by fusing it with the HlyA type I secretion system of uropathogenic E. coli, resulted in protection against spore challenge (17). Subsequently, it was discovered that protection against intraperitoneal spore challenge in mice could be achieved by using just carboxyl-terminal D4 (13). D4 therefore becomes an attractive candidate for vaccine development with Salmonella live vectors.

We were encouraged when the fusion of D4 to the carboxyl terminus of ClyA resulted in excellent expression of D4 and export of the fusion protein into supernatants of the live vector. The export of D4 resulted in a striking enhancement of the immunogenicity of this domain over its immunogenicity when expressed in the cytoplasm, despite the fact that the levels of expression of both forms of D4 were comparable (Fig. 3A and B). The trend toward lower anti-LPS titers in mice immunized with CVD 908-htrA(pSEC91D4-c) versus CVD 908-htrA and CVD 908-htrA(pSEC91D4) could be associated with a decrease in metabolic fitness in vivo due to an unexpected toxicity associated with D4 expression, an effect reduced by the export of D4 from the live vector. In support of this hypothesis, we noted that CVD 908-htrA(pSEC91D4-c) had a slower growth rate in vitro than CVD 908htrA and CVD 908-htrA(pSEC91D4) (data not shown). We believe that such observations underscore the critical importance of balancing the expression of a foreign antigen with the metabolic fitness of a live vector to maximize relevant immune responses to both the live vector and any coexpressed foreign proteins.

CVD 908-htrA expressing PA, either cytoplasmically or as an exported fusion protein, was also able to elicit T-cell responses, as demonstrated by the presence of PA-specific IFN-γ- and IL-5-secreting cells. While antigen export appears to be critical for the induction of PA-specific antibody responses, both constructs showed similar frequencies of cytokine-producing cells. The most likely explanation for this observation is that while antigens delivered intracellularly by the live vector can be presented by professional antigen-presenting cells to stimulate T cells, antigens released extracellularly can be easily accessed by B-cell immunoglobulin receptors to induce antibody production. The presence of IFN-γ and IL-5, together with antigen-specific antibody production, suggests that both Th1 and Th2 responses are induced. Such a balanced response profile could be beneficial in the induction of a protective immune response against anthrax toxin, since relevant protective epitopes remain undefined.

The adaptation of the ClyA system that we have designed for antigen transport in live-vector vaccine strains opens the theoretical possibility of engineering multivalent live-vector vaccines in which three distinct foreign antigens are rendered more immunogenic by surface presentation or export via vesicles. Thus, ClyA itself could export antigen 1; antigen 2 could be surface exposed on vesicles via an independent surface expression system (such as the AIDA-I or MisL autotransporter fusions) (23, 40, 41); and antigen 3 could be targeted to the periplasmic space, where it could become entrapped within vesicles during ClyA release. Based on extensive experience with proteosome-based vaccines (i.e., antigen adsorbed to group B Neisseria meningitidis outer membrane protein vesicles), one would also expect the foreign antigens within the ClyA outer membrane vesicles to be more immunogenic than the same antigens delivered as soluble proteins (26). Moreover, the LPS present within such vesicles may trigger the innate immune system, resulting in enhanced adaptive immune responses to the antigens within ClyA vesicles.

ClyA is theoretically a virulence factor. When overexpressed from multicopy expression plasmids, in principle it could confer some degree of pathogenicity to attenuated Salmonella serovar Typhi live vectors, such as CVD 908-htrA. A number of point mutations have now been defined for the ClyA homolog HlyE; these mutations preserve the tertiary structure of HlyE while removing hemolytic activity. As demonstrated by Wallace et al. (52), the introduction of the triple mutation V185S-A187S-I193S reduces hemolytic activity to 0.002% the wild-type activity while still preserving normal folding of the protein, as judged by gel filtration and observed solubility; since V185, A187, and I193 all lie within the critical hydrophobic transmembrane region proposed to be required for pore formation, the introduction of serine polar side chains would be expected to block membrane insertion and abolish hemolytic activity. More important, del Castillo et al. (9) demonstrated that deletion of amino acids 183 to 202 from within the transmembrane region of HlyE results in the export of an enzymatically active β-lactamase domain as a carboxyl-terminal fusion in the absence of hemolytic activity. Thus, inactivating mutations can be successfully engineered into ClyA to remove hemolytic activity while preserving folding, solubility, and export properties. Exploitation of ClyA could represent a versatile additional tool for the development of stabilized low-copy-number plasmid-based expression systems that minimize host metabolic burden while enhancing immune responses to selected foreign antigens expressed by mucosally administered polyvalent live-vector vaccines.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grant 5 RO1 AI29471, research contract NO1 AI45251, and the Mid-Atlantic Regional Center for Excellence (MARCE) for Biodefense and Emerging Infectious Diseases Research grant U54 AI57168 (to M. M. Levine). J. Green thanks the BBSRC (Swindon, United Kingdom) for financial support.

We thank Nicola Walker for kindly providing purified recombinant PA83. We also thank Laura Quinn Leverton for computer analysis of D4 expression levels in Fig. 3A.

Editor: D. L. Burns

REFERENCES

- 1.Atkins, A., N. R. Wyborn, A. J. Wallace, T. J. Stillman, L. K. Black, A. B. Fielding, M. Hisakado, P. J. Artymiuk, and J. Green. 2000. Structure-function relationships of a novel bacterial toxin, hemolysin E. The role of αG. J. Biol. Chem. 275:41150-41155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Balbas, P., X. Soberon, E. Merino, M. Zurita, H. Lomeli, F. Valle, N. Flores, and F. Bolivar. 1986. Plasmid vector pBR322 and its special-purpose derivatives—a review. Gene 50:3-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blomfield, I. C., V. Vaughn, R. F. Rest, and B. I. Eisenstein. 1991. Allelic exchange in Escherichia coli using the Bacillus subtilis sacB gene and a temperature-sensitive pSC101 replicon. Mol. Microbiol. 5:1447-1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brossier, F., M. Weber-Levy, M. Mock, and J. C. Sirard. 2000. Role of toxin functional domains in anthrax pathogenesis. Infect. Immun. 68:1781-1786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Collier, R. J., and J. A. Young. 2003. Anthrax toxin. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 19:45-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cordoba-Rodriguez, R., H. Fang, C. S. Lankford, and D. M. Frucht. 2004. Anthrax lethal toxin rapidly activates caspase-1/ICE and induces extracellular release of interleukin (IL)-1beta and IL-18. J. Biol. Chem. 279:20563-20566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coulson, N. M., M. Fulop, and R. W. Titball. 1994. Bacillus anthracis protective antigen, expressed in Salmonella typhimurium SL 3261, affords protection against anthrax spore challenge. Vaccine 12:1395-1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coulson, N. M., M. Fulop, and R. W. Titball. 1994. Effect of different plasmids on colonization of mouse tissues by the aromatic amino acid dependent Salmonella typhimurium SL 3261. Microb. Pathog. 16:305-311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.del Castillo, F. J., F. Moreno, and I. del Castillo. 2001. Secretion of the Escherichia coli K-12 SheA hemolysin is independent of its cytolytic activity. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 204:281-285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.del Castillo, F. J., S. C. Leal, F. Moreno, and I. del Castillo. 1997. The Escherichia coli K-12 sheA gene encodes a 34-kDa secreted haemolysin. Mol. Microbiol. 25:107-115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deng, W., S. R. Liou, G. Plunkett III, G. F. Mayhew, D. J. Rose, V. Burland, V. Kodoyianni, D. C. Schwartz, and F. R. Blattner. 2003. Comparative genomics of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi strains Ty2 and CT18. J. Bacteriol. 185:2330-2337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fellows, P. F., M. K. Linscott, B. E. Ivins, M. L. Pitt, C. A. Rossi, P. H. Gibbs, and A. M. Friedlander. 2001. Efficacy of a human anthrax vaccine in guinea pigs, rabbits, and rhesus macaques against challenge by Bacillus anthracis isolates of diverse geographical origin. Vaccine 19:3241-3247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Flick-Smith, H. C., N. J. Walker, P. Gibson, H. Bullifent, S. Hayward, J. Miller, R. W. Titball, and E. D. Williamson. 2002. A recombinant carboxy-terminal domain of the protective antigen of Bacillus anthracis protects mice against anthrax infection. Infect. Immun. 70:1653-1656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Galen, J. E., O. G. Gomez-Duarte, G. Losonsky, J. L. Halpern, C. S. Lauderbaugh, S. Kaintuck, M. K. Reymann, and M. M. Levine. 1997. A murine model of intranasal immunization to assess the immunogenicity of attenuated Salmonella typhi live vector vaccines in stimulating serum antibody responses to expressed foreign antigens. Vaccine 15:700-708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Galen, J. E., and M. M. Levine. 2001. Can a ′flawless' live vector vaccine strain be engineered? Trends Microbiol. 9:372-376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Galen, J. E., J. Nair, J. Y. Wang, S. S. Wasserman, M. K. Tanner, M. Sztein, and M. M. Levine. 1999. Optimization of plasmid maintenance in the attenuated live vector vaccine strain Salmonella typhi CVD 908-htrA. Infect. Immun. 67:6424-6433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garmory, H. S., R. W. Titball, K. F. Griffin, U. Hahn, R. Bohm, and W. Beyer. 2003. Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium expressing a chromosomally integrated copy of the Bacillus anthracis protective antigen gene protects mice against an anthrax spore challenge. Infect. Immun. 71:3831-3836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hess, J., I. Gentschev, D. Miko, M. Welzel, C. Ladel, W. Goebel, and S. H. E. Kaufmann. 1996. Superior efficacy of secreted over somatic antigen display in recombinant Salmonella vaccine induced protection against listeriosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:1458-1463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hone, D. M., A. M. Harris, S. Chatfield, G. Dougan, and M. M. Levine. 1991. Construction of genetically defined double aro mutants of Salmonella typhi. Vaccine 9:810-816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ivins, B. E., M. L. Pitt, P. F. Fellows, J. W. Farchaus, G. E. Benner, D. M. Waag, S. F. Little, G. W. Anderson, Jr., P. H. Gibbs, and A. M. Friedlander. 1998. Comparative efficacy of experimental anthrax vaccine candidates against inhalation anthrax in rhesus macaques. Vaccine 16:1141-1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kang, H. Y., and R. Curtiss III. 2003. Immune responses dependent on antigen location in recombinant attenuated Salmonella typhimurium vaccines following oral immunization. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 37:99-104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krishnanchettiar, S., J. Sen, and M. Caffrey. 2003. Expression and purification of the Bacillus anthracis protective antigen domain 4. Protein Expr. Purif. 27:325-330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lattemann, C. T., J. Maurer, E. Gerland, and T. F. Meyer. 2000. Autodisplay: functional display of active β-lactamase on the surface of Escherichia coli by the AIDA-I autotransporter. J. Bacteriol. 182:3726-3733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee, J.-S., K.-S. Shin, J.-G. Pan, and C.-J. Kim. 2000. Surface-displayed viral antigens on Salmonella carrier vaccine. Nat. Biotechnol. 18:645-648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Little, S. F., B. E. Ivins, P. F. Fellows, M. L. Pitt, S. L. Norris, and G. P. Andrews. 2004. Defining a serological correlate of protection in rabbits for a recombinant anthrax vaccine. Vaccine 22:422-430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lowell, G. H., D. Burt, and G. White. 2004. Proteosome technology for vaccines and adjuvants, p. 271-282. In M. M. Levine, J. B. Kaper, R. Rappuoli, M. A. Liu, and M. F. Good (ed.), New generation vaccines. Marcel Dekker, Inc., New York, N.Y.

- 27.Ludwig, A., S. Bauer, R. Benz, B. Bergmann, and W. Goebel. 1999. Analysis of the SlyA-controlled expression, subcellular localization and pore-forming activity of a 34 kDa haemolysin (ClyA) from Escherichia coli K-12. Mol. Microbiol. 31:557-567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Orr, N., J. E. Galen, and M. M. Levine. 1999. Expression and immunogenicity of a mutant diphtheria toxin molecule, CRM197, and its fragments in Salmonella typhi vaccine strain CVD 908-htrA. Infect. Immun. 67:4290-4294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oscarsson, J., M. Westermark, S. Lofdahl, B. Olsen, H. Palmgren, Y. Mizunoe, S. N. Wai, and B. E. Uhlin. 2002. Characterization of a pore-forming cytotoxin expressed by Salmonella enterica serovars Typhi and Paratyphi A. Infect. Immun. 70:5759-5769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oscarsson, J., Y. Mizunoe, L. Li, X.-H. Lai, A. Wieslander, and B. E. Uhlin. 1999. Molecular analysis of the cytolytic protein ClyA (SheA) from Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 32:1226-1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oscarsson, J., Y. Mizunoe, B. E. Uhlin, and D. J. Haydon. 1996. Induction of haemolytic activity in Escherichia coli by the slyA gene product. Mol. Microbiol. 20:191-199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Parkhill, J., G. Dougan, K. D. James, N. R. Thomson, D. Pickard, J. Wain, C. Churcher, K. L. Mungall, S. D. Bentley, M. T. G. Holden, M. Sebaihia, S. Baker, D. Basham, K. Brooks, T. Chillingworth, P. Connerton, A. Cronin, P. Davis, R. M. Davies, L. Dowd, N. White, J. Farrar, T. Feltwell, N. Hamlin, A. Haque, T. T. Hien, S. Holroyd, K. Jagels, A. Krogh, T. S. Larsen, S. Leather, S. Moule, P. O'Gaora, C. Parry, M. Quail, K. Rutherford, M. Simmonds, J. Skelton, K. Stevens, S. Whitehead, and B. G. Barrell. 2001. Complete genome sequence of a multiple drug resistant Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi CT18. Nature 413:848-852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pasetti, M. F., R. J. Anderson, F. R. Noriega, M. M. Levine, and M. B. Sztein. 1999. Attenuated deltaguaBA Salmonella typhi vaccine strain CVD 915 as a live vector utilizing prokaryotic or eukaryotic expression systems to deliver foreign antigens and elicit immune responses. Clin. Immunol. 92:76-89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pasetti, M. F., T. E. Pickett, M. M. Levine, and M. B. Sztein. 2000. A comparison of immunogenicity and in vivo distribution of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi and Typhimurium live vector vaccines delivered by mucosal routes in the murine model. Vaccine 18:3208-3213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pasetti, M. F., R. Salerno-Goncalves, and M. B. Sztein. 2002. Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi live vector vaccines delivered intranasally elicit regional and systemic specific CD8+ major histocompatibility class I-restricted cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Infect. Immun. 70:4009-4018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Petosa, C., R. J. Collier, K. R. Klimpel, S. H. Leppla, and R. C. Liddington. 1997. Crystal structure of the anthrax toxin protective antigen. Nature 385:833-838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pickett, T. E., M. F. Pasetti, J. E. Galen, M. B. Sztein, and M. M. Levine. 2000. In vivo characterization of the murine intranasal model for assessing the immunogenicity of attenuated Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi strains as live mucosal vaccines and as live vectors. Infect. Immun. 68:205-213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pitt, M. L., S. Little, B. E. Ivins, P. Fellows, J. Boles, J. Barth, J. Hewetson, and A. M. Friedlander. 1999. In vitro correlate of immunity in an animal model of inhalational anthrax. J. Appl. Microbiol. 87:304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pittman, P. R., G. Kim-Ahn, D. Y. Pifat, K. Coonan, P. Gibbs, S. Little, J. G. Pace-Templeton, R. Myers, G. W. Parker, and A. M. Friedlander. 2002. Anthrax vaccine: immunogenicity and safety of a dose-reduction, route-change comparison study in humans. Vaccine 20:1412-1420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rizos, K., C. T. Lattemann, D. Bumann, T. F. Meyer, and T. Aebischer. 2003. Autodisplay: efficacious surface exposure of antigenic UreA fragments from Helicobacter pylori in Salmonella vaccine strains. Infect. Immun. 71:6320-6328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ruiz-Olvera, P., F. Ruiz-Perez, N. V. Sepulveda, A. Santiago-Machuca, R. Maldonado-Rodriguez, G. Garcia-Elorriaga, and C. Gonzalez-Bonilla. 2003. Display and release of the Plasmodium falciparum circumsporozoite protein using the autotransporter MisL of Salmonella enterica. Plasmid 50:12-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Russmann, H., E. I. Igwe, J. Sauer, W. D. Hardt, A. Bubert, and G. Geginat. 2001. Protection against murine listeriosis by oral vaccination with recombinant Salmonella expressing hybrid Yersinia type III proteins. J. Immunol. 167:357-365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Russmann, H., H. Shams, F. Poblete, Y. Fu, J. E. Galan, and R. O. Donis. 1998. Delivery of epitopes by the Salmonella type III secretion system for vaccine development. Science 281:565-568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 45.Sambrook, J., and D. W. Russell. 2001. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, p. 15-35. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 46.Shaw, K. J., P. N. Rather, R. S. Hare, and G. H. Miller. 1993. Molecular genetics of aminoglycoside resistance genes and familial relationships of the aminoglycoside-modifying enzymes. Microbiol. Rev. 57:138-163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Su, G. F., H. N. Brahmbhatt, V. de Lorenzo, J. Wehland, and K. N. Timmis. 1992. Extracellular export of Shiga toxin B-subunit/haemolysin A (C-terminus) fusion protein expressed in Salmonella typhimurium aroA-mutant and stimulation of B-subunit specific antibody responses in mice. Microb. Pathog. 13:465-476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tacket, C. O., M. Sztein, G. Losonsky, S. S. Wasserman, J. P. Nataro, R. Edelman, D. Pickard, G. Dougan, S. Chatfield, and M. M. Levine. 1997. Safety of live oral Salmonella typhi vaccine strains with deletions in htrA and aroC aroD and immune responses in humans. Infect. Immun. 65:452-456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tzschaschel, B. D., C. A. Guzman, K. N. Timmis, and V. de Lorenzo. 1996. An Escherichia coli hemolysin transport system-based vector for the export of polypeptides: export of Shiga-like toxin IIeB subunit by Salmonella typhimurium aroA. Nat. Biotechnol. 14:765-769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Varughese, M., A. V. Teixeira, S. Liu, and S. H. Leppla. 1999. Identification of a receptor-binding region within domain 4 of the protective antigen component of anthrax toxin. Infect. Immun. 67:1860-1865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wai, S. N., B. Lindmark, T. Soderblom, A. Takade, M. Westermark, J. Oscarsson, J. Jass, A. Richter-Dahlfors, Y. Mizunoe, and B. E. Uhlin. 2003. Vesicle-mediated export and assembly of pore-forming oligomers of the enterobacterial ClyA cytotoxin. Cell 115:25-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wallace, A. J., T. J. Stillman, A. Atkins, S. J. Jamieson, P. A. Bullough, J. Green, and P. J. Artymiuk. 2000. E. coli hemolysin E (HlyE, ClyA, SheA): X-ray crystal structure of the toxin and observation of membrane pores by electron microscopy. Cell 100:265-276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Welkos, S., A. Friedlander, S. Weeks, S. Little, and I. Mendelson. 2002. In-vitro characterisation of the phagocytosis and fate of anthrax spores in macrophages and the effects of anti-PA antibody. J. Med. Microbiol. 51:821-831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Welkos, S., S. Little, A. Friedlander, D. Fritz, and P. Fellows. 2001. The role of antibodies to Bacillus anthracis and anthrax toxin components in inhibiting the early stages of infection by anthrax spores. Microbiology 147:1677-1685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Welkos, S. L., J. R. Lowe, F. Eden-McCutchan, M. Vodkin, S. H. Leppla, and J. J. Schmidt. 1988. Sequence and analysis of the DNA encoding protective antigen of Bacillus anthracis. Gene 69:287-300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wyborn, N. R., A. Atkins, R. E. Roberts, S. J. Jamieson, S. Tzokov, P. A. Bullough, T. J. Stillman, P. J. Artymiuk, J. E. Galen, L. Zhao, M. M. Levine, and J. Green. 2004. Properties of hemolysin E (HlyE) from a pathogenic Escherichia coli avian isolate and studies of HlyE export. Microbiology 150:1495-1505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]