Abstract

The epigenome is a dynamic mediator of gene expression that shapes the way that cells, tissues, and organisms respond to their environment. Initial studies in the emerging field of “toxicoepigenetics” have described either the impact of an environmental exposure on the epigenome or the association of epigenetic signatures with the onset or progression of disease; however, the majority of these pioneering studies examined the relationship between discrete epigenetic modifications and the effects of a single environmental factor. Although these data provide critical blocks with which we construct our understanding of the role of the epigenome in susceptibility and disease, they are akin to individual letters in a complex alphabet that is used to compose the language of the epigenome. Advancing the use of epigenetic data to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the mechanisms underlying exposure effects, identify susceptible populations, and inform the next generation risk assessment depends on our ability to integrate these data in a way that accounts for their cumulative impact on gene regulation. Here we will review current examples demonstrating associations between the epigenetic impacts of intrinsic factors, such as such as age, genetics, and sex, and environmental exposures shape the epigenome and susceptibility to exposure effects and disease. We will also demonstrate how the “epigenetic seed and soil” model can be used as a conceptual framework to explain how epigenetic states are shaped by the cumulative impacts of intrinsic and extrinsic factors and how these in turn determine how an individual responds to subsequent exposure to environmental stressors.

Keywords: epigenetics, chromatin, susceptibility, DNA methylation, seed and soil, developmental toxicity, prenatal, reproductive and developmental toxicology; toxicoepigenetics.

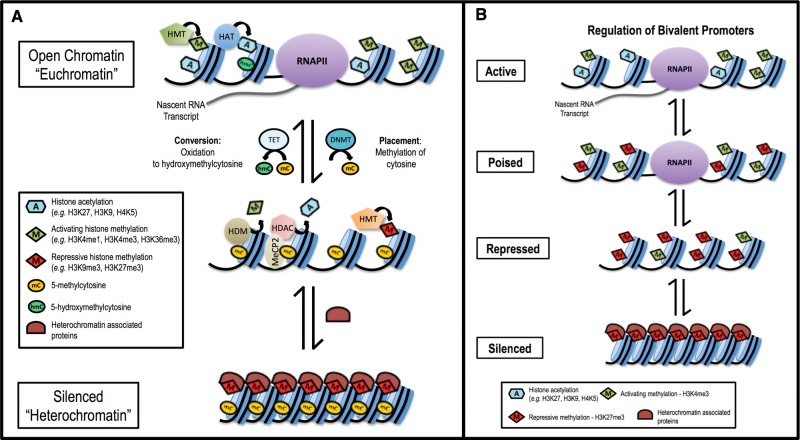

The structure and function of cells, tissues, and organs is determined by the differential expression of approximately 20 000 genes (Pruitt et al., 2009), which must be regulated in a carefully choreographed manner. The epigenome—a suite of covalent modifications to DNA and its histone protein scaffolding—dictates chromatin structure, interactions between the transcriptional machinery and DNA, and ultimately gene expression (Figure 1). Epigenetic modification of DNA is limited to methylation; however, while most commonly associated with gene silencing (Baylin, 2005; Clark and Melki, 2002; Esteller, 2007; Thienpont, et al., 2016; Venolia and Gartler, 1983), DNA methylation has a diverse range of roles in regulating gene expression that vary with its genomic context (reviewed in Jones, 2012; Law and Jacobsen, 2010; Smith and Meissner, 2013). In contrast to DNA, histone proteins are decorated with a broad range of covalent modifications, including methylation, acetylation, phosphorylation, ubiquitination, and many others (Kouzarides, 2007). In all, at least 130 unique epigenetic modifications have been identified to date (Tan et al., 2011). Akin to the arrangement of letters to form words in a language, these modification patterns function cooperatively as an epigenetic code that is “written” through the enzymatic activities of epigenetic modifying enzymes and “read” by specialized binding domains in transcription factors and other chromatin-associated proteins (Cedar and Bergman, 2009; Jenuwein and Allis, 2001; Strahl and Allis, 2000). Patterns of activating modifications facilitate an open chromatin structure (“euchromatin”) where DNA is accessible to transcription factors, while patterns of repressive modifications lead to compaction of chromatin structure (“heterochromatin”) that obstructs binding of the transcriptional machinery (Jenuwein and Allis, 2001).

FIG. 1.

Epigenetic modifications function in concert to regulate gene expression. A, Histone modifications and DNA methylation function cooperatively to regulate chromatin structure, accessibility to transcription factors, and gene expression. DNA methylation is the addition of a methyl group by a DNMT to the cytosine residue of CpG dinucleotides in DNA. Methylation of DNA in gene regulatory regions (promoters and enhancers) often results in transcriptional repression; however, the oxidation of 5-methylcytosine to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine by the 10–11 translocation family of methylcytosine dioxygenases is associated with the activation of gene expression. The genome is packaged on a protein scaffolding composed of histone proteins arranged into repeating units known as nucleosomes. The unstructured tails of these histones extend outside of the core nucleosome and are subject to numerous modifications such as acetylation, methylation, phosphorylation, ubiquitination, et cetera. These modifications can be activating (eg, H3K4me3 and acetylation) or repressive/silencing (eg, H3K9me3 and H3K27me3). Activating histone acetylation and methylation, modifications made by histone acetyltransferases and histone methyltransferases (HMTs), facilitate chromatin accessibility (euchromatin), recruitment of the transcriptional machinery, including RNA polymerase II, and initiation/elongation of transcription. DNA methylation and repressive histone modifications function cooperatively, through proteins such as methyl-CpG binding protein 2, histone deacetylases, histone demethylases, and repressive HMTs, in the recruitment of transcriptional co-repressors and the formation of repressed and inactive (heterochromatin) epigenetic states. B, Bivalent gene promoters regulate expression based on the balance of activating and repressive histone modifications. Bivalent modifications occur in gene promoters (H3K4me3/H3K27me3) and enhancers (H3K27ac/5mC) in both stem and somatic cells. The balance of otherwise opposing modifications determines whether a gene is repressed, poised (contains a paused polymerase ready to initiate transcription), or actively expressed. This figure is a representation of the generalized functions of certain epigenetic factors; however, the functionality of epigenetic modifications can vary based on the specific context in which they exist.

The epigenetic code functions as a form of biological memory at the cellular level that directs both basal gene expression and stimulus/exposure-responsive gene induction based on the persistent epigenetic impacts of an individual’s chemical and non-chemical environment. These patterns of epigenetic modifications are both inherited, mitotically and meiotically, and acquired as a result of intrinsic and extrinsic environmental factors. As a result, the epigenome acts as a biosensor of an individual’s environment. The use of epigenetic data has the potential to refine traditional methods for identifying at-risk populations by providing a biomarker of how the cumulative impact of an individual’s environmental history influences their response to future exposures. Although promising, this prospect has yet to be validated for practical application; however, it has fueled the rapid expansion of toxicoepigenetics research and led to the identification of novel putative links between environmental exposures, disease susceptibility, and public health (Bollati and Baccarelli, 2010; Cortessis et al., 2012).

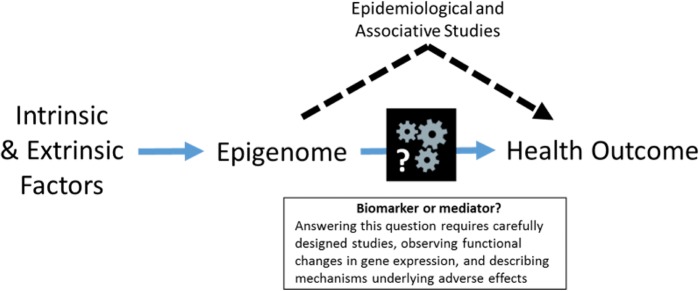

Early toxicoepigenetic studies have played a pivotal role in demonstrating that environmental factors can alter the epigenome thus revising the epigenetic language that regulates gene expression and susceptibility; however, these studies have typically focused on individual epigenetic markers, the equivalent of a single letter in an alphabet containing at least 130 characters. Although each of these studies provides a letter in this regulatory language, the complexity of the epigenome requires the incorporation of additional information to assemble a clear picture of how the environment shapes the regulation of gene expression and susceptibility to exposure-related disease. Unfortunately, this complexity also engenders significant technical and practical challenges to simultaneously examining multiple epigenetic markers within the regulatory regions of a range of genes. Traditional approaches to identifying susceptible populations consider intrinsic factors such as age, sex, and genotype. In recent years, greater consideration has been given to the role of the aggregate effects of extrinsic exposures (referred to as the “exposome”) in the alteration of physiological processes and susceptibility to disease. Although these individual approaches provide valuable insight into aspects of susceptibility, considering intrinsic and extrinsic factors separately does not faithfully reflect the effects of an individual’s environment on health and disease susceptibility. Since both intrinsic and extrinsic factors (collectively referred to as “environmental factors”) impact the epigenome, we proposed the “epigenetic seed and soil” model (Figure 2; adapted from McCullough et al., 2016) as a conceptual framework that describes the cumulative effects of environmental factors on susceptibility and exposure-related disease by integrating their impact on the epigenome. Here we will review literature that demonstrates the effects of individual environmental factors on the epigenome and discuss how the epigenetic seed and soil model can be used to explain how the cumulative impact of environmental factors on the epigenome shapes exposure effects and susceptibility.

FIG. 2.

The epigenetic seed and soil model. Individuals with different backgrounds, representing unique combinations of intrinsic and extrinsic factors, will have differing “epigenetic soil.” The “seed” represents the cellular signaling arriving at a gene promoter, either homeostatic signaling or signaling arising from an acute stimulus (eg, a toxicant exposure). In more responsive individuals, the epigenetic soil is more receptive to the incoming seed, resulting in increased gene transcription. Increases in gene transcription may either occur at baseline (a result of homeostatic signaling) or in response to an acute stimulus.

ENVIRONMENTAL FACTORS INFLUENCE THE EPIGENOME

Age

An individual’s epigenome is constantly being reshaped throughout his or her lifetime by two related processes known as the epigenetic clock and epigenetic drift. Although epigenetic changes associated with the epigenetic clock are programmed, those associated with epigenetic drift result from the accumulation of errors in epigenome maintenance. Common trends in specific age-related DNA methylation changes across individuals have been described as the “epigenetic clock” (Wilson et al., 1987; reviewed in Jones et al., 2015). Although this epigenetic clock correlates with chronological age (Hannum et al., 2013; Horvath et al, 2012; Horvath, 2013; Smith et al., 2014), it advances more slowly in those with relatively “healthier” lifestyles and greater longevity (Gentilini et al., 2013; Marioni et al., 2015b) and accelerated epigenetic age is associated with toxic exposures, obesity, disease, and early mortality (Christiansen et al., 2016; Faulk et al., 2014; Horvath, 2013; Horvath et al., 2014; Levine et al., 2015; Marioni et al., 2015a).

The age-dependent accumulation of changes in epigenetic modification states correlates with age-related changes in the expression of key metabolic enzymes, such as the cytochrome p450 (CYP) enzyme family (Giebel et al., 2016; Li et al., 2009) and may play a critical role in lifestage-dependent windows of susceptibility (de Magalhães et al., 2009). The diversity and abundance of expressed CYPs changes as a function of age (Hakkola et al., 1998; Parkinson et al., 2004; Stevens et al., 2003) and is an important determinant of inter-individual variability in xenobiotic metabolism (Hughes et al., 1996; Johnson, 2003; Tréluyer et al., 2001). CYP3A7 is highly expressed in the fetal liver, yet by two years of age its expression is barely detectable. Conversely, hepatic CYP3A4 expression is low at birth but increases through childhood and plateaus by adulthood (Stevens et al., 2003). Giebel et al. (2016) attributed the ontogeny of CYP3A7 and 3A4 expression to changes in the balance of activating histone H3 lysine 4 trimethylation (H3K4me3) and repressive (H3K27me3) modification levels within the regulatory regions of these genes. The post-natal increase in CYP3A4 expression corresponds to an increase in H3K4me3 abundance, and thus a shift in the balance of H3K4me3/H3K27me3 in favor of gene expression after birth. Similarly, the post-natal increase in H3K27me3 abundance at the CYP3A7 locus in post-natal liver shifted the H3K4me3/H3K27me3 balance in favor of repression. This “bivalency”, the co-occupancy of both activating and repressive epigenetic modifications, serves as a biological “switch” to regulate gene expression (described in Figure 1B). The age-dependent changes in the H3K4me3/H3K27me3 balance regulate the expression of specific metabolic enzymes during development and have significant consequences on xenobiotic metabolism, which are particularly well documented for pediatric use of pharmaceutical drugs (de Wildt, et al., 1999).

Genetics

Genetic variation between individuals is often assessed by examining single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). These variations in DNA sequence can have functional consequences on the epigenome and can be important arbiters of health and disease. SNPs within the regulatory regions of a gene, such as the promoter or enhancer, can influence its expression by altering CpG sites that are subject to DNA methylation or transcription factor binding sites. Further, SNPs within the protein-coding regions of epigenetic effector proteins—such as histone and DNA modifying-enzymes and transcription factors—can alter the epigenetic landscape across the epigenome by influencing binding and/or catalytic activity (Lemire et al., 2015; Tehranchi et al., 2016). As a result, genetic polymorphisms play a notable role in shaping inter-individual variability in the epigenome (Gertz et al., 2011).

Genome-wide association and quantitative trait loci (QTL) studies have identified important associations between SNPs and disease phenotypes; however, these traditional approaches often lack the ability to provide a mechanistic connection when identified SNPs are located in noncoding regions (Visscher et al., 2012). The incorporation of epigenetic information into genetic analysis has provided insight into the role of SNPs in a range of disease studies (Gamazon et al., 2013; Heyn et al., 2014; Jaffe et al., 2016; Liu et al., 2013). Similar integrative approaches have been used to describe the role of non-coding SNPs in the modulating expression of susceptibility genes such as paraoxonase 1 (PON1), an arylesterase enzyme involved in lipid biodisposition, antioxidant defense, and the hydrolysis of organophosphate compounds. Individuals with reduced expression or activity of PON1 are at an increased risk of a wide range of diseases including vascular diseases, metabolic syndrome, Alzheimer’s disease, various cancers, and reduced capacity to metabolize xenobiotics (Camps et al., 2009; Costa et al., 2003; Furlong et al., 2010). Of the various PON1 polymorphisms, the SNP PON1T-108 is the best predictor of gene expression; however, it is located in a non-coding promoter region and genetic analyses were not sufficient to identify the mechanism by which this SNP influenced PON1 expression. By integrating epigenetic data, Huen et al. (2015) determined that PON1T-108 was located in a CpG site and reduced PON1 expression by increasing local DNA methylation. Subsequent studies demonstrated that PON1T-108 disrupted the binding of the transcription factor specificity protein 1 (Deakin et al., 2003; Osaki et al., 2004) and reduced promoter activity, which led to increased local DNA methylation. These studies, demonstrate the capacity for genetic polymorphisms to impact the epigenome within the regulatory regions of genes that play important roles in the response to toxic exposures.

Sex

Males and females exhibit sex-specific expression of a wide range of genes, including metabolic enzymes, which impact both basic physiology and the response to environmental exposures (reviewed in Anderson 2005; Rademaker 2001; Soldin and Mattison, 2009; Tran et al., 1998). Sexually dimorphic gene expression is largely a function of endocrine differences between males and females, especially in the liver where approximately 1000 genes, including many CYPs, exhibit sexually biased expression (Waxman and O’Connor 2006; Zhang et al., 2011). Differences in the secretion of hormones, such as growth hormone (GH), control the expression of many transcription factors, particularly signal transducer and activator of transcription 5 (STAT5). The role of the GH-STAT5 axis, which has been implicated in the regulation of as many as 75–82% of hepatic sex-biased genes (Clodfelter et al., 2006), was recently linked to sex-dependent differences in DNase hypersensitivity (a measure of chromatin accessibility), 6 histone modifications (activating H3K4me3, K27ac, K4me1, K36me3; repressive K27me3, K9me), and the binding of five GH-regulated transcription factors (Sugathan and Waxman, 2013). Enhancer regions of male-biased genes were enriched for the “pioneer” transcription factors forkhead box proteins A1 and/or A2 (FOXA1, FOXA2), which facilitate the opening of chromatin. Increased accessibility was followed by the recruitment of additional transcription factors such as STAT5 and deposition of activating histone modifications (H3K27ac and H3K4me1). Aberrant expression of female-biased genes in males was prevented by the enrichment of both the repressive histone modification H3K27me3 and the male-biased transcriptional repressor B-Cell CLL/Lymphoma 6 (BCL6). Female-specific gene expression was strongly driven by the transcription factor cut-like homeobox 2 (CUX2), which can interact with distinct factors to act as either a repressor or an activator. To activate female-biased genes, CUX2 functions cooperatively with STAT5 and FOXA2 to facilitate the removal of repressive H3K27me3 at gene enhancers. Conversely, CUX2 suppresses male-biased genes by binding enhancer regions to promote repressive chromatin structure. Although further studies are required to integrate the contributions of DNA methylation and other histone modifications, the epigenome plays a clear role in the sexually dimorphic gene expression.

Toxicant Exposures and Developmental Reprogramming

The aforementioned intrinsic factors are intractable qualities that influence an individual’s susceptibility to toxicant exposure effects; however, environmental exposures also alter the epigenome and impact susceptibility and disease. These factors range from daily nutrition to overt toxicant exposures, but share the potential to alter the epigenome. Broadly speaking, these extrinsic factors can impact health through phenomena such as epigenetic carcinogenesis, regulation of inflammation, and developmental reprogramming, among others. Carcinogenesis is a frequently studied toxicological outcome, yet many carcinogens are not directly genotoxic. Although the underlying mechanisms have not yet been thoroughly described, the “epigenetic model of carcinogenesis” (Feinberg, 2004; Koturbash et al., 2011) postulates that epigenetic changes at cancer-associated genes impair the normal cellular mechanisms that prevent carcinogenic transformation. This model is supported by data demonstrating that exposure to tobacco smoke, benzene, arsenic, or nickel (reviewed in Koturbash et al., 2011; Ray et al., 2014) alters the epigenome at cancer-associated genes such as p53, p16, and Ras association domain family member 1 (Rassf1), making exposed cells more susceptible to subsequent carcinogenic stimuli. Similarly, exposure to a range of air pollutants alters the epigenome and expression of genes that are critical in regulating the balance between host defense and inflammatory disease (Bellavia et al., 2013; Bind et al., 2014; Madrigano et al., 2012; Nadeau et al., 2010). Further, epigenetic modifications play key roles in modulating responses to multiple exposures, such as inflammatory adaptation and priming (Foster et al., 2007; Gazzar et al., 2007). Many further examples exist and each theme could constitute its own review; however, here we will focus on endocrine disruptor exposure studies because they offer some of the most promising evidence for the potential use of the epigenome as an indicator of long-term susceptibility due to the persistent reprogramming that results from exposure. The studies discussed below provide examples of how multiple lines of evidence can be integrated to assemble a more complete understanding of the impacts of environmental exposures on the epigenome. Further, the studies by Bredfeldt et al. (2010), Greathouse et al. (2012), and Jefferson et al. (2013) adopt a target gene-centered approach to evaluating the relationship between exposure-induced epigenetic changes and the alternative regulation of outcome-associated genes.

Developmental Reprogramming

Exposures that occur during sensitive periods of epigenetic remodeling, such as during pregnancy and early childhood, have been shown to reprogram the epigenome and predispose offspring to diseases later in life. Strong associations between developmental exposures, the epigenome, and adult disease come from early exposure to endocrine disrupting chemicals (EDCs). Endogenous hormones, such as estrogen, play an integral and carefully choreographed role in regulating gene expression programs that are critical for normal development and reproductive function. These processes can be disrupted and reprogrammed by early exposure to exogenous estrogen mimetic compounds (xenoestrogens), such as the synthetic estrogen diethylstilbestrol (DES), dietary phytoestrogen genistein, and the ubiquitous consumer goods plasticizer, bisphenol-A (BPA). Although DES was removed from the American pharmaceutical market due to adverse health effects from in utero exposures, BPA and genistein are commonplace in the developed world. Unlike analogous adult exposures, DES, BPA, and genistein reprogram hormone-responsive gene expression and increase the incidence of uterine abnormalities and neoplasia in rodent developmental exposure models (Greathouse et al., 2008; Jefferson et al., 2013; Li et al., 1997; Markey et al., 2005; Murray et al., 2007; Newbold et al., 2007, 2012; Suen et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2014). This reprogramming is thought to occur through various changes in DNA methylation and histone modifications (reviewed in Walker, 2011), which alter both basal gene expression and hormone-dependent gene induction. These changes in transcriptional programs are thought to underlie developmental abnormalities (Jefferson et al., 2011) and the development of neoplasia later in life, especially after the initiation of menses in female mice when endogenous estrogen levels increase.

To explore the relationship between xenoestrogen exposure, neoplasia, and the epigenome, Bredfeldt et al., (2010) and Greathouse et al., (2008, 2012) modeled developmental DES, genistein, and BPA exposure in the Eker rats, a strain that is predisposed to a common hormone-responsive uterine tumor known as leiomyoma (Walker and Stewart, 2005). Although the transcriptional reprogramming induced by all 3 EDCs required estrogen receptor-α (ERα), only DES and genistein induced activation of “pre-genomic” ERα signaling through the PI3K/Akt kinase pathway. The resulting phosphorylation and inactivation of the histone methyltransferase enhancer of zeste homolog 2 (Ezh2) led to a global reduction in abundance of the repressive histone modification H3K27me3 in the uteri of DES- and genistein-exposed animals. Unlike DES and genistein, BPA exposure increased global abundance of H3K27me3 and did not increase the incidence of leiomyoma, despite being associated with reproductive anomalies and other types of neoplasia in other studies (Murray et al., 2007; Newbold et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2014). As the catalytic component of the histone-modifying polycomb repressive complex 2 Ezh2 plays a critical role in embryonic development, differentiation, and the control of bivalent gene promoters. Although the mechanisms through which different xenoestrogens exert their effects on the epigenome varies, dysregulation of key regulatory histone modification, such as H3K27me3, is likely to play an integral role in developmental reprogramming.

A similar study in mice demonstrated that developmental exposure to DES reprogrammed expression of a range of histone modifying enzymes (Hdac1, Hdac2, Hdac3, Kat2a, Kat2b, Myst2, and Kmt2b), DNA methyltransferases (Dnmt1 and Dnmt3a), and a methylcytosine dioxygenase (Tet1) (Jefferson et al., 2013). These changes in epigenetic modification enzymes coincided with alterations in the abundance of the activating histone modifications H3K9ac, H4K5ac, and H3K4me3 within the regulatory regions of cancer-associated genes that were permanently up-regulated following developmental genistein exposure (Suen et al., 2016). By examining multiple epigenetic aspects these studies provide a more comprehensive perspective on the mechanisms responsible for the xenoestrogen-induced persistent reprogramming of gene expression and associated increase in developmental abnormalities and cancer susceptibility later in life.

CUMULATIVE EFFECTS OF ENVIRONMENTAL FACTORS ON THE EPIGENOME

Relating Cumulative Epigenetic States to Exposure Outcomes and Susceptibility

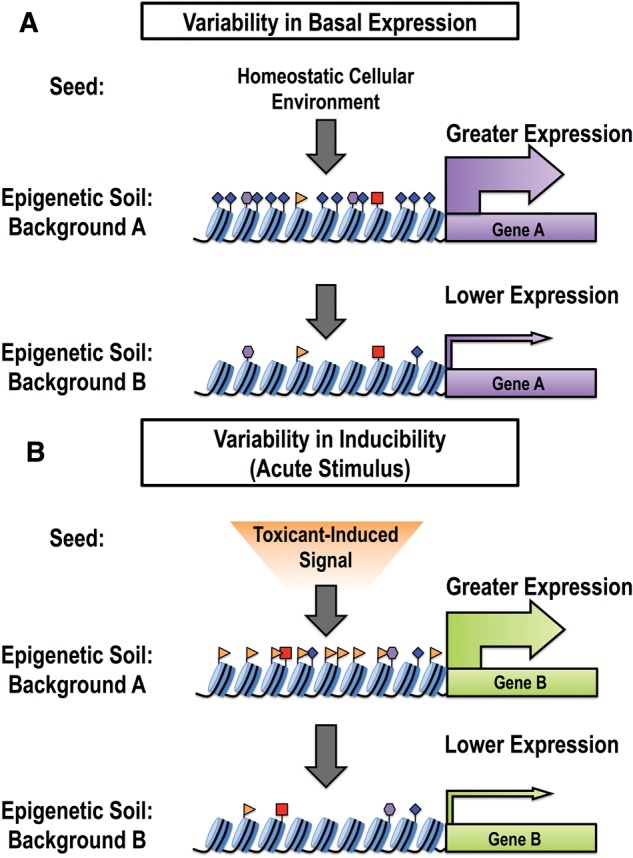

Unlike traditional approaches that rely on discrete factors such as age, genotype, and disease state, using the epigenome as a biomarker has the potential to provide a more comprehensive perspective on susceptibility by integrating the cumulative impacts of environmental factors. An individual’s epigenome is composed of patterns of DNA methylation and histone modifications that are both inherited and acquired as a result of intrinsic and extrinsic environmental factors. Due to practical limitations, the influence of environmental factors on the epigenome is typically studied individually; however, translating their impact on exposure-mediated disease requires consideration of the cumulative impacts of environment on the epigenome. We recently hypothesized that baseline epigenetic modification states, an “epigenetic snapshot” in time reflecting the cumulative influences of intrinsic and extrinsic factors on the epigenome, could predict both basal and toxicant-induced gene expression (McCullough et al., 2016). To test this hypothesis we compared the relative baseline (pre-exposure) abundance of specific epigenetic modifications in gene promoters with the basal and pollutant-induced (ozone) expression of target genes in a panel of donors using a primary bronchial epithelial cell air-liquid interface exposure model. We found that distinct epigenetic signatures were associated with the magnitude of basal and ozone-induced expression. Although not encompassing all epigenetic modifications or genes, our findings demonstrate that cumulative epigenetic states correlate with both basal and toxicant-induced gene expression.

The Seed and Soil Model

Here we expand upon our previously proposed “epigenetic seed and soil model” (McCullough et al., 2016), a conceptual framework that describes the cumulative effects of environmental factors on susceptibility and exposure-related disease by integrating the cumulative impact of environmental exposures on the epigenome (Figure 2). In this model, the “seed” represents incoming cellular signal (either homeostatic or toxicant-induced) and the “soil” represents the mosaic of epigenetic modifications within the regulatory region of a given gene. The epigenetic “soil” influences gene expression by either altering basal gene expression or modulating the magnitude of gene induction in response to an acute stimulus. In the first scenario, environmental factors shape the epigenome within the regulatory region(s) of a gene, which alters basal expression by reprograming its response to normal homeostatic signals. In the second scenario, environmentally mediated epigenetic changes reprogram how inducible a gene will be in response to an acute stimulus, such as toxicant exposure. If the cumulative effects of intrinsic and extrinsic forces result in a more receptive epigenetic soil (ie, contains modifications favoring gene transcription) then the stimulus induced-signal will be robust; however, a less-receptive epigenetic soil will result in modest induction. Thus the seed and soil model serves as a streamlined approach to conceptualizing the functional consequences resulting from the cumulative impact of environment-induced epigenetic changes with respect to health, exposure effects, and susceptibility (examples given in Table 1).

TABLE 1.

“Seed and Soil Table”

| Authors | Intrinsic or Extrinsic Factor | Driver | Epigenetic Soil | “Seed” (‘−‘indicates homeostatic signaling) | Functional Outcome | Health and Disease Implications | Expression change: Basal (B) Induced (I) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bredfeldt et al. (2010), Greathouse et al. (2008, 2012) | Extrinsic (rat) | Neonatal exposure: DES, BPA, genistein | Genistein and DES activated the PI3K/AKT pathway, inhibiting EZH2 via phosphorylation thereby reducing global H3K27me3; BPA increased H3K27me3 | — (Endogenous estrogen) | BPA, Genistein and DES reprogrammed both basal and estrogen-induced gene expression | Uterine neoplasia | B, I |

| Burdge et al. (2007); Lillycrop et al. (2008) | Extrinsic (mice) | Maternal protein-restricted diet | Pparɑ, Gr promoter hypomethylation; altered expression | — | Metabolic phenotype; increased Gr, Pparɑ expression | Metabolic syndrome and associated diseases | B |

| Cui et al. (2006) | Extrinsic (mice) | Arsenic | Hypomethylation of Rassf1a and p16 | — | Reduced gene expression found in lung tumors | Carcinogenesis | B |

| Dave et al. (2015) | Baseline (human) | Baseline | Altered methylation of PPARG1 and ADIPOR1 | — | Altered expression of PPARG1 and ADIPOR1 | Obesity; Metabolic syndrome | B |

| Foster et al. (2007) | Extrinsic (in vitro human) | LPS | Different patterns of H4Ac and H3K4me3 at genes that show LPS tolerance (pro-inflammatory genes) and those that do not (antimicrobial genes) | Secondary LPS exposure | Reduced pro-inflammatory gene expression and increased antimicrobial gene expression | Inflammation; Host defense | I |

| Giebel et al. (2016) | Intrinsic (human) | Age | In postnatal liver, alteration at bivalent promoters: enrichment of repressive H3K27me3 at CYP3A7; less H3K27me3 enrichment at CYP3A4 promoter | — | CYP ontogeny; predominant expression of fetal form (CYP3A7) switches to adult form (CYP3A4) | Adverse drug reactions | B |

| Ho et al. (2006), Tang et al. (2012) | Extrinsic (rat; in vitro rat) | Neonatal estradiol, BPA | Hypomethylation of Pde4d4; hypomethylation of Nsbp1; hypermethylation of Hpcal1 | — (xenoestrogen exposures) | Continual elevated expression of Pde4d4 demonstrated to precede pathological change; also noted aberrant expression of epigenetic regulators | Prostate cancer | B |

| Huen et al. (2015) | Intrinsic (human) | Genome | Promoter polymorphisms→ Differential methylation of PON1 | — | Reduced expression of PON1 | Various diseases; reduced ability to metabolize certain drugs and pollutant exposures | B |

| Lemire et al. (2015) | Intrinsic (human) | Genome | meQTLs: SNPS associated with methylation of CpGs; Various effects | — | Various effects | Various health implications | B, I |

| Li et al. (2009) | Intrinsic (mouse) | Age | Alterations in H3K4me2 and H3K27me2 in hepatic gene promoters at various developmental ages | — | CYP ontogeny: Increased H3K4me2 in neonates and adults leads to increases in Cyp3a16 and Cyp3a11 expression, respectively. Suppressed expression of neonatal form (Cyp3a16) in adults corresponded with increases in H3K27me3 and reduction of H3K4me2 | Adverse drug reactions | B |

| McCullough et al. (2016) | Baseline (in vitro human) | Baseline | Baseline chromatin motifs at ozone-responsive genes | Ozone | H3K4me3, H3K27me, H4Ac are associated with inducibility of HMOX-1, COX2. Basal expression of IL-8 and IL-6 are related to H4Ac and H3K4me3, among others. | Susceptibility to ozone exposure | B, I |

| Nadeau et al. (2010) | Extrinsic (human) | Ambient air pollution | Hypermethylation of FOXP3 | — | Altered FOXP3 expression; Altered T-Reg Cell function | Asthma | B |

| Rojas et al. (2015) | Extrinsic (human) | Pre-natal arsenic exposure | Altered DNA methylation patterns in six genes | — | Genes with altered methylation patterns also have altered expression. Associated with birth outcomes: gestational age, placental weight, head circumference | Pregnancy complications; Arsenic-associated diseases | B |

| Salam et al. (2012) | Extrinsic and Intrinsic (human) | Genome: NOS2 promoter haplotype | Differential methylation status | PM Exposure | Haplotype interacts with exposure to dictate the level of NOS2 detected in exhaled NO | Lung inflammation and pulmonary disease | I |

| Sugathan and Waxman (2013) | Intrinsic (mouse) | Sex | The regulatory regions of sex-biased genes have particular chromatin landscapes characterized by DNAse hypersensitivity, histone modifications, and the binding of GH-mediated transcription factors | — | Approximately 900 genes in the liver exhibit sexually dimorphic gene expression | Sex-based differences in drug pharmacokinetics | B, I |

| Susiarjo et al. (2013) | Extrinsic (mouse) | BPA | Altered methylation at six imprinted genes | — | Altered expression of imprinted genes in placenta; abnormal placental development | Fetal and post-natal health; imprinting disorders | B |

| Tang et al. (2012) | Extrinsic (human in vivo; in vitro) | PAH (BaP) | Hypermethylation of IFNy | — | Reduced expression of IFNy in vitro; Association between IFNy methylation and PAH exposure in vivo | Dysregulation of T-cell response- asthma | B |

| Tehranchi et al. (2016) | Intrinsic | Genotype | Altered TF binding and chromatin architecture | Various effects | Various effects | Various health implications | B, I |

| Tserel et al. (2015) | Intrinsic (human) | Age | Altered methylation of genes involved in T-cell immune responses and differentiation | — | Expression changes in genes related to T-cell function | “Inflamm-aging;” Impaired T-cell function | B |

| Zeybel et al. (2012) | Extrinsic (rat) | CCl4 (fibrogenic hepatotoxin) | Altered DNA methylation at Pparγ and Tgfβ1; Enriched H2A.Z and H3K27me3 at Pparγ locus in sperm | Subsequent CCl4 exposure in F1-3 generations | Altered expression of Pparγ and Tgfβ1; suppressed fibrotic response in offspring with ancestral liver fibrosis | Liver fibrosis- carcinogenesis | B |

Selected studies linking epigenetic alterations with functional changes and health outcomes.

CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Toxicoepigenetics is a rapidly emerging field of study that has made great advances in associating a broad range of environmental exposures with changes to the epigenome. The impact of toxicoepigenetic studies within the basic science and risk assessment communities will continue to grow as they evolve to include a broader range of epigenetic modifications to develop a more comprehensive understanding of how environmental factors shape the epigenome and thus exposure effects and susceptibility. Further, the identification of more complete epigenetic susceptibility profiles will provide targets to facilitate the exploration of causal links between environmental factors, the epigenome, and health outcomes. The application of toxicoepigenetic data will rely heavily on forthcoming studies bridging current knowledge gaps (Figure 3), which will involve addressing the following:

FIG. 3.

Need for causal in addition to associative evidence in defining the relationship between epigenetic state, exposures, and health outcomes. The majority of current epigenetics studies in public health demonstrate that intrinsic or extrinsic forces shape the epigenome, or describe associations between the epigenome and disease. Based on this information it is difficult to distinguish whether the epigenome has a role in disease development or is a biomarker of effect. In order to link the epigenome with health outcomes, it is necessary to implement study designs that may be able distinguish these roles. In addition to high-throughput screening, additional experiments should identify functional changes in gene expression and how these changes lead to the resulting outcome or phenotype.

DNA methylation and histone modifications are often studied independently; however, future studies will benefit from the integration of data related to both types of epigenetic modifications due to their concerted roles in regulating gene expression (Roadmap Epigenetics Consortium, 2015). Further, current high-throughput methods for analyzing global DNA methylation do not distinguish between 5-methylcytosine and its relatively abundant oxidation product 5-hydroxymethylcytosine, which can play an opposing role in gene regulation. Future studies would benefit from the incorporation of methods that distinguish the contributions of these two types of DNA methylation with divergent functions.

Most toxicoepigenetics studies have examined the relationship between epigenetic states and basal gene expression; however, this approach may overlook inducible genes that also play critical roles in response to external insults. The inclusion of both of these types of gene expression will give a more comprehensive perspective on how differences in epigenetic states shape exposure effects and susceptibility. Current studies typically examine the effects of environmental exposures on the epigenome at a single dose and time. The expansion of these studies to include a range of doses and exposure durations will facilitate the identification of threshold doses and response times.

The majority of toxicoepigenomic studies have succeeded in observing associations between environmental factors, epigenetic changes, and health outcomes. The impact of these studies will be increased by further studies that directly assess causal relationships between these factors (Figure 3) (Birney et al., 2016).

High-throughput data have been instrumental in generating hypotheses regarding the role of the epigenome in exposure effects and susceptibility. The utility of these data will be increased by complimentary studies that test the hypotheses generated through focused approaches that determine whether the identified epigenetic states are causative of associated health outcomes.

Controlling for cell populations, especially in blood samples, is a major complicating factor as inadvertently measuring different proportions of cell types could mislead the identification of environmentally induced epigenetic changes (Reinius et al., 2012). Ideally, cell sub-types should be separated by biochemical or immunologically based techniques prior to epigenetic analysis to avoid this potential flaw in the information obtained; however, when not possible (eg, when using previously stored samples), the development, validation, and application of emerging post-hoc computational methods, such as those described by Houseman et al. (2012), may allow for the interrogation of cell type specific epigenetic changes in samples that contain mixtures of cell types.

This review has provided a brief overview of how intrinsic and extrinsic factors can influence the epigenome and thus modulate exposure effects and disease susceptibility; however, we have only described a subset here. This rapidly evolving field has the potential to fundamentally change our understanding of the mechanisms underlying exposure effects and how cumulative environmental history shapes susceptibility. Reaching this potential will require continued innovation by researchers to overcome both technical and scientific challenges to definitively define causal roles for the epigenome in exposure-related outcomes. Doing so will ultimately allow for validation of the utility of epigenetic endpoints as indicators of exposure, modulators of susceptibility, and predictors of adverse health effects.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank Dr David Diaz-Sanchez and Dr Marie C. Fortin for their expert opinions during critical review of the manuscript. The research described in this article has been reviewed by the Environmental Protection Agency and approved for publication. The contents of this article do not necessarily represent Agency policy, nor does mention of trade names or commercial products constitute endorsement or recommendations for use.

FUNDING

This work was supported by U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) intramural funds and an EPA Pathfinder Innovation Project program grant awarded to S.D.M. E.C. Bowers is supported by NIEHS Toxicology Training Grant T32-ES007126.

REFERENCES

- Anderson G. D. (2005). Sex and racial differences in pharmacological response: where is the evidence? Pharmacogenetics, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics. J. Womens Health 14, 19–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baylin S. B. (2005). DNA methylation and gene silencing in cancer. Nat. Clin. Pract. Oncol. 2, S4–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellavia A., Urch B., Speck M., Brook R. D., Scott J. A., Albetti B., Behbod B., North M., Valeri L., Bertazzi P., et al. (2013). DNA hypomethylation, ambient particulate matter, and increased blood pressure: findings from controlled human exposure experiments. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 4, e001981.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bind M. A., Lepeule J., Zanobetti A., Gasparrini A., Baccarelli A. A., Coull B. A., Tarantini L., Vokonas P. S., Koutrakis P., Schwartz J. (2014). Air pollution and gene-specific methylation in the Normative Aging Study. Epigenetics 9, 448–458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birney E., Smith G. D., Greally J. M. (2016). Epigenome-wide association studies and the interpretation of disease-omics. PLoS Genet. 12, e1006105.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollati V., Baccarelli A. (2010). Environmental epigenetics. Heredity 105, 105.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bredfeldt T. G., Greathouse K. L., Safe S. H., Hung M. C., Bedford M. T., Walker C. L. (2010). Xenoestrogen-induced regulation of EZH2 and histone methylation via estrogen receptor signaling to PI3K/AKT. Mol. Endocrinol. 24, 993–1006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burdge G. C., Slater-Jefferies J., Torrens C., Phillips E. S., Hanson M. A., Lillycrop K. A. (2007). Dietary protein restriction of pregnant rats in the F0 generation induces altered methylation of hepatic gene promoters in the adult male offspring in the F1 and F2 generations. Br. J. Nutr. 97, 435–439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camps J., Marsillach J., Joven J. (2009). The paraoxonases: role in human diseases and methodological difficulties in measurement. Crit. Rev. Clin. Lab. 46, 83–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cedar H., Bergman Y. (2009). Linking DNA methylation and histone modification: Patterns and paradigms. Nat. Rev. Genet. 10, 295–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christiansen L., Lenart A., Tan Q., Vaupel J. W., Aviv A., McGue M., Christensen K. (2016). DNA methylation age is associated with mortality in a longitudinal Danish twin study. Aging Cell 15, 149–154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark S. J., Melki J. (2002). DNA methylation and gene silencing in cancer: Which is the guilty party?. Oncogene 21, 5380–5387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clodfelter K. H., Holloway M. G., Hodor P., Park S. H., Ray W. J., Waxman D. J. (2006). Sex-dependent liver gene expression is extensive and largely dependent upon signal transducer and activator of transcription 5b (STAT5b): STAT5b-dependent activation of male genes and repression of female genes revealed by microarray analysis. Mol. Endocrinol. 20, 1333–1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortessis V. K., Thomas D. C., Levine A. J., Breton C. V., Mack T. M., Siegmund K. D., Haile R. W., Laird P. W. (2012). Environmental epigenetics: prospects for studying epigenetic mediation of exposure-response relationships. Hum. Genet. 131, 1565–1589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa L. G., Cole T. B., Jarvik G. P., Furlong C. E. (2003). Functional genomics of the paraoxonase (PON1) polymorphisms: effects on pesticide sensitivity, cardiovascular disease, and drug metabolism. Annu. Rev. Med. 54, 371–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui X. G., et al. (2006). Chronic oral exposure to inorganic arsenate interferes with methylation status of p16INK4a and RASSF1A and induces lung cancer in A/J mice. Toxicol. Sci. 9, 372–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dave V., Yousefi P., Huen K., Volberg V., Holland N. (2015). Relationship between expression and methylation of obesity-related genes in children. Mutagenesis 30, 411–420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Magalhães J. P., Curado J., Church G. M. (2009). Meta-analysis of age-related gene expression profiles identifies common signatures of aging. Bioinformatics 25, 875–881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Wildt S. N., Kearns G. L., Leeder J. S., van den Anker J. N. (1999). Cytochrome P450 3A: ontogeny and drug disposition. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 37, 485–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deakin S., Leviev I., Guernier S., James R. W. (2003). Simvastatin modulates expression of the PON1 gene and increases serum paraoxonase A role for sterol regulatory element–binding protein-2. Aterioscl. Throm. Vasc. 23, 2083–2089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esteller M. (2007). Epigenetic gene silencing in cancer: the DNA hypermethylome. Hum. Mol. Genet. 16(S1), R50–R59., [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faulk C., Liu K., Barks A., Goodrich J. M., Dolinoy D. C. (2014). Longitudinal epigenetic drift in mice perinatally exposed to lead. Epigenetics 9, 934–941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg A. P. (2004). The epigenetics of cancer etiology. Sem. Cancer Biol. 14, 427–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster S. L., Hargreaves D. C., Medzhitov R. (2007). Gene-specific control of inflammation by TLR-induced chromatin modifications. Nature 447, 972–978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furlong C. E., Suzuki S. M., Stevens R. C., Marsillach J., Richter R. J., Jarvik G. P., Checkoway H., Samii A., Costa L. G., Griffith A., et al. (2010). Human PON1, a biomarker of risk of disease and exposure. Chem-Biol. Interact. 187, 355–361., [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamazon E. R., Badner J. A., Cheng L., Zhang C., Zhang D., Cox N. J., Gershon E. S., Kelsoe J. R., Greenwood T. A., Nievergelt C. M., et al. (2013). Enrichment of cis-regulatory gene expression SNPs and methylation quantitative trait loci among bipolar disorder susceptibility variants. Mol. Psychiatry 18, 340–346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazzar M. E., Yoza B. K., Hu J. Y. Q., Cousart S. L., McCall C. E. (2007). Epigenetic silencing of Tumor Necrosis Factor during endotoxin tolerance. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 26857–26864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentilini D., Mari D., Castaldi D., Remondini D., Ogliari G., Ostan R., Bucci L., Sirchia S. M., Tabano S., Cavagnini F. (2013). Role of epigenetics in human aging and longevity: genome-wide DNA methylation profile in centenarians and centenarians’ offspring. Age 35, 1961–1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gertz J., Varley K. E., Reddy T. E., Bowling K. M., Pauli F., Parker S. L., Kucera K. S., Willard H. F., Myers R. M. (2011). Analysis of DNA methylation in a three-generation family reveals widespread genetic influence on epigenetic regulation. PLoS Genet. 7, e1002228.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giebel N. L., Shadley J. D., McCarver D. G., Dorko K., Gramignoli R., Strom S. C., Yan K., Simpson P. M., Hines R. N. (2016). Role of chromatin structural changes in regulating human CYP3A ontogeny. Drug Metab. Dispos. 44, 1027–1037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greathouse K. L., Bredfeldt T., Everitt J. I., Lin K., Berry T., Kannan K., Mittelstadt M. L., Ho S. M., Walker C. L. (2012). Environmental estrogens differentially engage the histone methyltransferase EZH2 to increase risk of uterine tumorigenesis. Mol. Cancer Res. 10, 546–557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greathouse K. L., Cook J. D., Lin K., Davis B. J., Berry T. D., Bredfeldt T. G., Walker C. L. (2008). Identification of uterine leiomyoma genes developmentally reprogrammed by neonatal exposure to diethylstilbestrol. Reprod. Sci. 15, 765–778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hakkola J., Tanaka E., Pelkonen O. (1998). Developmental expression of cytochrome P450 enzymes in human liver. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 82, 209–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannum G., Guinney J., Zhao L., Zhang L., Hughes G., Sadda S., Klotzle B., Bibikova M., Fan J. B., Gao Y. (2013). Genome-wide methylation profiles reveal quantitative views of human aging rates. Mol. Cell 49, 359–367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyn H., Sayols S., Moutinho C., Vidal E., Sanchez-Mut J. V., Stefansson O. A., Nadal E., Moran S., Eyfjord J. E., Gonzalez-Suarez E., et al. (2014). Linkage of DNA methylation quantitative trait loci to human cancer risk. Cell Rep. 7, 331–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho S. M., Tang W. Y., Belmonte de Frausto J., Prins G. S. (2006). Developmental exposure to estradiol and bisphenol A increases susceptibility to prostate carcinogenesis and epigenetically regulates phosphodiesterase type 4 variant 4. Cancer Res. 66, 5624–5632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvath S. (2013). DNA methylation age of human tissues and cell types. Genome Biol. 14, R115.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvath S., Erhart W., Brosch M., Ammerpohl O., von Schönfels W., Ahrens M., Heits N., Bell J. T., Tsai P. C., Spector T. D., et al. (2014). Obesity accelerates epigenetic aging of human liver. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 111, 15538–15543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvath S., Zhang Y., Langfelder P., Kahn R. S., Boks M. P., van Eijk K., van den Berg L. H., Ophoff R. A. (2012). Aging effects on DNA methylation modules in human brain and blood tissue. Genome Biol. 13, R97.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houseman E., Accomando W. P., Koestler D. C., Christensen B. C., Marsit C. J., Nelson H. H., Wiencke J. K., Kelsey K. T. (2012). DNA methylation arrays as surrogate measures of cell mixture distribution. BMC Bioinformatics 13, 1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huen K., Yousefi P., Street K., Eskenazi B., Holland N. (2015). PON1 as a model for integration of genetic, epigenetic, and expression data on candidate susceptibility genes. Environ. Epigenet. 1, dvv003.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes J., Gill A. M., Mulhearn H., Powell E., Choonara I. (1996). Steady-State Plasma Concentrations of Midazolam in critically ill infants and children. Ann. Pharmacother. 30, 27–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaffe A. E., Gao Y., Deep-Soboslay A., Tao R., Hyde T. M., Weinberger D. R., Kleinman J. E. (2016). Mapping DNA methylation across development, genotype, and schizophrenia in the human frontal cortex. Nat. Neurosci. 19, 40–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jefferson W. N., Chevalier D. M., Phelps J. Y., Cantor A. M., Padilla-Banks E., Newbold R. R., Archer T. K., Kinyamu H. K., Williams C. J. (2013). Persistently altered epigenetic marks in the mouse uterus after neonatal estrogen exposure. Mol. Endocrinol. 27, 1666–1677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jefferson W. N., Padilla-Banks E., Phelps J. Y., Gerrish K. E., Williams C. J. (2011). Permanent oviduct posteriorization after neonatal exposure to the phytoestrogen genistein. Environ. Health. Perspect. 119, 1575–1582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenuwein T., Allis C. D. (2001). Translating the histone code. Science 293, 1074–1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson T. (2003). The development of drug metabolizing enzymes and their influence on the susceptibility to adverse drug reactions in children. Toxicology 192, 37–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones P. A. (2012). Functions of DNA methylation: islands, start sites, gene bodies, and beyond. Nat. Rev. Genet. 13, 484–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones M. J., Goodman S. J., Kobor M. S. (2015). DNA methylation and healthy human aging. Aging Cell 14, 924–932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koturbash I., Beland F. A., Pogribny I. P. (2011). Role of epigenetic events in chemical carcinogenesis—a justification for incorporating epigenetic evaluations in cancer risk assessment. Toxicol. Mech. Method 21, 289–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouzarides T. (2007). Chromatin modifications and their function. Cell 128, 693–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Law J. A., Jacobsen S. E. (2010). Establishing, maintaining and modifying DNA methylation patterns in plants and animals. Nat Rev Genet 11, 204–220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemire M., Zaidi S. H., Ban M., Ge B., Aissi D., Germain M., Kassam I., Wang M., Zanke B. W., Gagnon F., et al. (2015). Long-range epigenetic regulation is conferred by genetic variation located at thousands of independent loci. Nat. Commun. 6, 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine M. E., Hosgood H. D., Chen B., Absher D., Assimes T., Horvath S. (2015). DNA methylation age of blood predicts future onset of lung cancer in the women's health initiative. Aging (Albany NY) 7, 690–700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S., Washburn K. A., Moore R., Uno T., Teng C., Newbold R. R., McLachlan J. A., Negishi M. (1997). Developmental exposure to diethylstilbestrol elicits demethylation of estrogen-responsive lactoferrin gene in mouse uterus. Cancer Res. 57, 4356–4359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Cui Y., Hart S. N., Klaassen C. D., Zhong X. B. (2009). Dynamic patterns of histone methylation are associated with ontogenic expression of the Cyp3a genes during mouse liver maturation. Mol. Pharmacol. 75, 1171–1179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lillycrop K. A., Phillips E. S., Torrens C., Hanson M. A., Jackson A. A., Burdge G. C. (2008). Feeding pregnant rats a protein-restricted diet persistently alters the methylation of specific cytosines in the hepatic PPARα promoter of the offspring. Br. J. Nutr. 100, 278–282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Aryee M. J., Padyukov L., Fallin M. D., Hesselberg E., Runarsson A., Reinius L., Acevedo N., Taub M., Ronninger M. (2013). Epigenome-wide association data implicate DNA methylation as an intermediary of genetic risk in rheumatoid arthritis. Nat. Biotechnol. 31, 142–147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madrigano J., Baccarelli A., Mittleman M. A., Sparrow D., Spiro A., Vokonas P. S., Cantone L., Kubzansky L., Schwartz J. (2012). Air pollution and DNA methylation: Interaction by psychological factors in the VA Normative Aging Study. Am. J. Epidemiol. 176, 224–232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marioni R. E., Shah S., McRae A. F., Chen B. H., Colicino E., Harris S. E., Gibson J., Henders A. K., Redmond P., Cox S. R. (2015a). DNA methylation age of blood predicts all-cause mortality in later life. Genome Biol. 16, 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marioni R. E., Shah S., McRae A. F., Ritchie S. J., Muniz-Terrera G., Harris S. E., Gibson J., Redmond P., Cox S. R., Pattie A. (2015b). The epigenetic clock is correlated with physical and cognitive fitness in the Lothian Birth Cohort 1936. Int. J. Epidemiol. 44, 1388–1396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markey C. M., Wadia P. R., Rubin B. S., Sonnenschein C., Soto A. M. (2005). Long-term effects of fetal exposure to low doses of the xenoestrogen bisphenol-A in the female mouse genital tract. Biol. Reprod. 72, 1344–1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCullough S. D., Bowers E. C., On D. M., Morgan D. S., Dailey L. A., Hines R. N., Devlin R. B., Diaz-Sanchez D. (2016). Baseline chromatin modification levels may predict interindividual variability in ozone-induced gene expression. Toxicol. Sci. 150, 216–224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray T. J., Maffini M. V., Ucci A. A., Sonnenschein C., Soto A. M. (2007). Induction of mammary gland ductal hyperplasias and carcinoma in situ following fetal bisphenol A exposure. Reprod. Toxicol. 23, 383–390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadeau K., McDonald-Hyman C., Noth E. M., Pratt B., Hammond S. K., Balmes J., Tager I. (2010). Ambient air pollution impairs regulatory T-cell function in asthma. J. Allergy. Clin. Immunol. 126, 845–852 e10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newbold R. R., Jefferson W. N., Padilla-Banks E. (2007). Long-term adverse effects of neonatal exposure to bisphenol A on the murine female reproductive tract. Reprod. Toxicol. 24, 253–258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newbold R. R. (2012). Prenatal exposure to diethylstilbestrol and long-term impact on the breast and reproductive tract in humans and mice. J. Dev. Orig. Health Dis. 3, 73–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osaki F., Ikeda Y., Suehiro T., Ota K., Tsuzura S., Arii K., Kumon Y., Hashimoto K. (2004). Roles of Sp1 and protein kinase C in regulation of human serum paraoxonase 1 (PON1) gene transcription in HepG2 cells. Atherosclerosis 176, 279–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkinson A., Mudra D. R., Johnson C., Dwyer A., Carroll K. M. (2004). The effects of gender, age, ethnicity, and liver cirrhosis on cytochrome P450 enzyme activity in human liver microsomes and inducibility in cultured human hepatocytes. Toxicol. Appl. Pharm. 199, 193–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pruitt K. D., Harrow J., Harte R. A., Wallin C., Diekhans M., Maglott D. R., Searle S., Farrell C. M., Loveland J. E., Ruef B. J., et al. (2009). The consensus coding sequence (CCDS) project: Identifying a common protein-coding gene set for the human and mouse genomes. Genome Res. 19, 1316–1323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rademaker M. (2001). Do women have more adverse drug reactions?. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2, 349–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray P. D., Yosim A., Fry R. C. (2014). Incorporating epigenetic data into the risk assessment process for the toxic metals arsenic, cadmium, chromium, lead, and mercury: strategies and challenges. Front. Genet. 5, 1–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinius L. E., Acevedo N., Joerink M., Pershagen G., Dahlén S. E., Greco D., Söderhäll C., Scheynius A., Kere J. (2012). Differential DNA methylation in purified human blood cells: Implications for cell lineage and studies on disease susceptibility. PLoS One 7, e41361.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roadmap Epigenomics Consortium (2015). Integrative analysis of 111 reference human epigenomes. Nature 518, 317–330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rojas D., Rager J. E., Smeester L., Bailey K. A., Drobna Z., Rubio-Andrade M., Styblo M., Garcia-Vargas G., Fry R. C. (2015). Prenatal arsenic exposure and the epigenome: identifying sites of 5-methylcytosine alterations that predict functional changes in gene expression in newborn cord blood and subsequent birth outcomes. Toxicol. Sci. 143, 97–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salam M. T., Byun H. M., Lurmann F., Breton C. V., Wang X., Eckel S. P., Gilliland F. D. (2012). Genetic and epigenetic variations in inducible nitric oxide synthase promoter, particulate pollution, and exhaled nitric oxide levels in children. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 129, 232–239. e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith Z. D., Meissner A. (2013). DNA methylation: roles in mammalian development. Nat. Rev. Genet. 14, 204–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith J. A., Zagel A. L., Sun Y. V., Dolinoy D. C., Bielak L. F., Peyser P. A., Turner S. T., Mosley T. H., Jr, Kardia S. L. (2014). Epigenomic indicators of age in African Americans. Hereditary Genet. 3, 1–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soldin O. P., Mattison D. R. (2009). Sex differences in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 48, 143–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens J. C., Hines R. N., Gu C., Koukouritaki S. B., Manro J. R., Tandler P. J., Zaya M. J. (2003). Developmental expression of the major human hepatic CYP3A enzymes. J. Pharm. Exp. Ther. 307, 573–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strahl B. D., Allis C. D. (2000). The language of covalent histone modifications. Nature 403, 41–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suen A. A., Jefferson W. N., Wood C. E., Padilla-Banks E., Bae-Jump V. L., Williams C. J. (2016). SIX1 oncoprotein as a biomarker in a model of hormonal carcinogenesis and in human endometrial cancer. Mol. Cancer Res. 14, 849–858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugathan A., Waxman D. J. (2013). Genome-Wide Analysis of Chromatin States Reveals Distinct Mechanisms of sex-dependent gene regulation in male and female mouse liver. Mol. Cell Biol. 33, 3594–3610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Susiarjo M., Sasson I., Mesaros C., Bartolomei M. S. (2013). Bisphenol A exposure disrupts genomic imprinting in the mouse. PLoS Genet. 9, e1003401.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan M., Luo H., Lee S., Jin F., Yang J. S., Montellier E., Buchou T., Cheng Z., Rousseaux S., Rajagopal N., et al. (2011). Identification of 67 histone marks and histone lysine crotonylation as a new type of histone modification. Cell 146, 1016–1028., [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang W. Y., Morey L. M., Cheung Y. Y., Birch L., Prins G. S., Ho S. M. (2012). Neonatal exposure to estradiol/bisphenol A alters promoter methylation and expression of Nsbp1 and Hpcal1 genes and transcriptional programs of Dnmt3a/b and Mbd2/4 in the rat prostate gland throughout life. Endocrinology 153, 42–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tehranchi A. K., Myrthil M., Martin T., Hie B. L., Golan D., Fraser H. B. (2016). Pooled ChIP-Seq links variation in transcription factor binding to complex disease risk. Cell 165, 730–741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thienpont B., Steinbacher J., Zhao H., D’Anna F., Kuchino A., Ploumakis A., Ghesquière B., Van Dyck L., Boeckx B., Schoonjans L., et al. (2016). Tumor hypoxia causes DNA methylation by reducing TET activity. Nature 537, 63–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran C., Knowles S. R., Liu B. A., Shear N. H. (1998). Gender differences in adverse drug reactions. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 38, 1003–1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tréluyer J. M., Rey E., Sonnier M., Pons G., Cresteil T. (2001). Evidence of impaired cisapride metabolism in neonates. Brit. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 52, 419–425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tserel L., et al. (2015). “Age-related profiling of DNA methylation in CD8+ T cells reveals changes in immune response and transcriptional regulator genes.” Sci. Reprod. 5, 13107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visscher P. M., Brown M. A., McCarthy M. I., Yang J. (2012). Five years of GWAS discovery. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 90, 7–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venolia L., Gartler S. M. (1983). Comparison of transformation efficiency of human active and inactive X-chromosomal DNA. Nature 302, 82–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker C. L. (2011). Epigenomic reprogramming of the developing reproductive tract and disease susceptibility in adulthood. Birth Defects Res. A Clin. Mol. Teratol. 91, 666–671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker C. L., Stewart E. A. (2005). Uterine fibroids: The elephant in the room. Science 308, 1589–1592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D., Gao H., Bandyopadhyay A., Wu A., Yeh I. T., Chen Y., Zou Y., Huang C., Walter C. A., Dong Q., et al. (2014). Pubertal bisphenol A exposure alters murine mammary stem cell function leading to early neoplasia in regenerated glands. Cancer Prev. Res. 7, 445–455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waxman D., O’Connor C. (2006). Growth hormone regulation of sex-dependent liver gene expression. Mol. Endocrinol. 20, 2613–2629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson V. L., Smith R. A., Ma S., Cutler R. G. (1987). Genomic 5-methyldeoxycytidine decreases with age. J. Biol. Chem. 262, 9948–9951. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeybel M., Hardy T., Wong Y. K., Mathers J. C., Fox C. R., Gackowska A., Oakley F., Burt A. D., Wilson C. L., Anstee Q. M., et al. (2012). Multigenerational epigenetic adaptation of the hepatic wound-healing response. Nat. Med. 18, 1369–1377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Klein K., Sugathan A., Nassery N., Dombkowski A., Zanger U. M., Waxman D. J. (2011). Transcriptional profiling of human liver identifies sex-biased genes associated with polygenic dyslipidemia and coronary artery disease. PLoS One 6, e23506.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]