Abstract

Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) have been shown to be critical biomarkers or therapeutic targets for human diseases. However, only a small number of lncRNAs were screened and characterized. Here, we identified 15 lncRNAs, which are associated with fatty liver disease. Among them, APOA4-AS is shown to be a concordant regulator of Apolipoprotein A-IV (APOA4) expression. APOA4-AS has a similar expression pattern with APOA4 gene. The expressions of APOA4-AS and APOA4 are both abnormally elevated in the liver of ob/ob mice and patients with fatty liver disease. Knockdown of APOA4-AS reduces APOA4 expression both in vitro and in vivo and leads to decreased levels of plasma triglyceride and total cholesterol in ob/ob mice. Mechanistically, APOA4-AS directly interacts with mRNA stabilizing protein HuR and stabilizes APOA4 mRNA. Deletion of HuR dramatically reduces both APOA4-AS and APOA4 transcripts. This study uncovers an anti-sense lncRNA (APOA4-AS), which is co-expressed with APOA4, and concordantly and specifically regulates APOA4 expression both in vitro and in vivo with the involvement of HuR.

INTRODUCTION

Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) are transcripts longer than 200 nucleotides, which do not have protein-coding potential. According to the genomic location, lncRNAs can be further categorized into intergenic, intronic, antisense and enhancer lncRNA (1). The antisense lncRNAs are transcribed from the antisense strand of protein-coding genes and often partially overlap with opposite strand mRNA. They may regulate sense-strand mRNAs in a positive (concordant) or negative (discordant) manner at transcriptional or post-transcriptional levels to carry out a wide range of biological and cellular functions (2,3). Emerging evidence has shown that lncRNAs are involved in multiple aspects of human health and diseases such as cancer (4) and diabetes (5,6).

APOA4 is a plasma lipoprotein, which is involved in the regulation of many metabolic pathways such as lipid and glucose metabolism. In rodents, APOA4 is primary synthesized by the liver and small intestine, followed by secretion into blood (7). The plasma APOA4 level correlates to the high-density lipoproteins levels and has anti-oxidative and anti-inflammatory properties (8–10). APOA4 mutations, which are associated with plasma lipid levels, have been identified in many populations (11–15). In vivo study has shown that APOA4 enhances triglyceride (TG) secretion from the liver (16). APOA4 could also enhance glucose stimulated insulin secretion (17) and inhibit glucose production in the liver (18). APOA4 is closely linked to the obesity and type 2 diabetes in both mice and humans (16,19). Multiple transcription factors such as HNF-4α, CREB, CREBH, ERR-α, PPARα and SERBP1 regulate APOA4 expression (7,16,20,21). However, whether lncRNA regulates APOA4 expression is largely unknown.

In the present study, we report an antisense lncRNA, APOA4-AS, which is transcribed from the reverse strand of APOA4 gene, partially overlaps with 3′ end of APOA4, and plays an essential role in regulating APOA4 gene expression. Short hairpin RNA (shRNA)-mediated knockdown of APOA4-AS leads to a reduction of APOA4 mRNA and protein abundance both in vitro and in vivo. In the genetic (ob/ob) obesity mice model, the elevated APOA4-AS expression contributes to the induction of APOA4 level in the liver and the hypertriglyceridemia in the plasma. Moreover, the protein–RNA complex (APOA4-AS–HuR) is involved in APOA4 expression; and furthermore, the deletion of HuR leads to a significant reduction of both APOA4-AS and APOA4 transcripts, indicating that APOA4-AS transcript may stabilize APOA4 mRNA through HuR. Results from current investigation present a novel antisense lncRNA, APOA4-AS that preserves the specific and potential biological function in regulating APOA4 expression and plasma TG levels, providing novel molecular mechanisms that can be applied to biomedical and therapeutic application for metabolic diseases such as type 2 diabetes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

RNA-seq and gene enrichment (GO) analysis

RNA-seq data (GSE43314, NCBI GEO database) from wide type (WT) and db/db mice were analyzed to identify differentially expressed lncRNAs in the liver with Tophat, Cufflinks and CummeRbund (22). To link the lncRNA to its associated protein-coding gene, lncRNA neighboring mRNAs were extracted and gene enrichment (GO) analysis was performed (http://genontology.org/).

Animals

C57BL/6 mice were purchased from Vital River (A Charles River Company, Beijing, China), and ob+/- mice were from Dr. Liangyou Rui (University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA) (23). All animals were maintained on 12-h light/12-h dark cycles in a clean facility at Northeast Normal University. This study was carried out in strict accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Institutes of Health and was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee or Animal Experimental Ethics Committee of Northeast Normal University (NENU/IACUC).

Human liver tissues

Human fatty and normal liver tissues were obtained from Shanghai Tongji Hospital based on liver biopsy. The study was approved by Shanghai Tongji Hospital ethical committees and individual permission was obtained using standard informed consent procedures. The investigation conforms to the principles that are outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki regarding the use of human tissues.

Rapid Amplification of cDNA Ends

RACE experiment was performed using Smart RACE cDNA Amplification Kit (Clontech) according to manufacturer's instruction. The 5′ RACE specific primer for APOA4-AS is 5′ GCCACTTGAGCTTCCTGGAGAAGAG 3′. The 5′ ends of APOA4-AS cDNA were polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplified and sequenced.

Northern blot

Total RNAs from the small intestine, liver, brain, heart and kidney of C57BL/6 mice were extracted using TriPure Isolation Reagent (Roche, Mannheim, Germany). RNAs were treated with DNase I to remove potential chromosomal DNA contamination. A 683-nt APOA4-AS probe was synthesized utilizing the PCR DIG Probes Synthesis Kit (Roche, Mannheim, Germany). Northern blot hybridization was performed using the DIG-labeled APOA4-AS probes, and the signals were detected by a DIG Nucleic Acid Detection Kit (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instruction. The primers used for APOA4-AS probe synthesis were listed: northern-F: 5′-GCAACCCGATGGGGCTAA-3′; northern-R: 5′-GGGCGTGCAGGAGAAACT-3′.

Primary hepatocyte cultures and adenoviral infection

Primary hepatocytes were isolated from male mice as described previously (24,25). Primary hepatocytes were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 2% fetal bovine serum, 100 units/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. For knockdown of APOA4-AS, two target sequences (shAPOA4-AS1: CACCAGAGCCTTGTTGAACAT and shAPOA4-AS2: AACTTGTCCTTTAAGTTGGTG) were selected. Primary hepatocytes were infected with control adenovirus (ad-scramble) or two different adenoviral vectors encoding APOA4-AS shRNAs (2 × 109 viral particles/well) for 2 h, and cultured for 36 h. Cells were then collected for quantitative real time (qRT)-PCR or immunobloting.

APOA4-AS knockdown in the liver of WT or ob/ob mice

C57BL/6 (8 weeks old) or ob/ob male mice (8 weeks old) were injected with ad-scramble or ad-shRNAs (1 × 1011 viral particles/mouse) via tail vein for 10–14 days. Liver sections were stained with hematoxylin-eosin. Plasma TG levels were measured using a TG assay kit (Pointe Scientific Inc., Canton, MI, USA). Plasma total cholesterol (TC) levels were measured using a TC assay kit (Dongou Diagnosis, Zhejiang, China).

Immunoblotting

Mice were anesthetized and sacrificed after fasting for 20–24 h. Livers were isolated and homogenized in a lysis buffer (50 mM Tris HCl, pH 7.5, 1% TRITON-X 100, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM EGTA, 100 mM NaF, 1 mM PMSF, 10 μg/ml aprotinin and 10 μg/ml leupeptin). The extracts from the liver, primary hepatocytes or HEK293T cells were immunoblotted with anti-APOA4 (Cell Signaling), anti-tubulin (Santa Cruz), anti-HuR and anti-albumin (Proteintech Group, Inc.) or anti-actin (BD Transduction Laboratories™).

qRT-PCR analysis

Total RNAs were extracted using TriPure Isolation Reagent (Roche, Mannheim, Germany). RNAs were treated with DNase I to remove potential chromosomal DNA contamination before cDNA synthesis. The first-strand cDNAs were synthesized using random primers and M-MLV reverse transcriptase (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). RNA abundance was measured using ABsolute qRT-PCR SYBR Mix (Life technologies) and Roche LightCycler 480 real-time PCR system (Roche, Mannheim, Germany). The expression of individual genes was normalized to the expression of 36B4, a house-keeping gene. Primers for real time qRT-PCR were listed in Supplementary Table S1.

In vitro translation assay

In vitro translation assay was performed using Transcend TM Non-Radioactive Translation Detection Systems (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). APOA4-AS transcript was subjected to in vitro translation assay, and luciferase serves as a positive control. Translational products were analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulphate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis followed by western blot. Strep-HRP detected the translational incorporation of biotinylated lysine. The same membrane was stained by Ponceau S.

CRISPR/Cas9 mediated gene editing

Two guide RNA sequences are selected (sgRNA1: 5′-CUUAUUCGGGAUAAAGU AGCAGG-3′; sgRNA2: 5′-CCGUUUGUCAAACCGGAUAAAGG-3′). The production of viral vectors Ad-Cas9, Ad-sgRNA1 and Ad-sgRNA2 was carried out as described elsewhere (26,27). Primary hepatocytes were isolated and infected with Ad-Cas9, or Ad-Cas9 and two Ad-sgRNAs (Ad-sgRNA1 and sgRNA2) adenovirus for 36 h. Immunoblotting and qRT-PCR analysis were performed.

RNA–protein interaction assays

HEK293T cells were transiently transfected with Flag-HuR and APOA4-AS (WT, T1 or T2) alone or in combination. Immunoprecipitation (IP) was performed by using anti-Flag agarose beads (Sigma). After washing, RNA was extracted with TriPure Isolation Reagent (Roche, Mannheim, Germany), treated with RNase-free DNase and analyzed by semi-quantitative RT-PCR or qRT-PCR. For reverse precipitation, StA-APOA4-AS (WT, T1 or T2) was precipitated from total lysates prepared from transfected HEK293T cells using streptavidin agarose beads. APOA4-AS binding proteins were eluted and analyzed by immunoblotting.

Statistical analysis

Figures were prepared by using GraphPad Prism software (La Jolla, CA, USA). Data were presented as means ± SEM. Differences between groups were analyzed by two-tailed Student's t-tests. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. For statistical analysis of RNA levels, data were calculated by the 2−ΔΔct method and represented as the means ± SEM. Differences between groups were analyzed by two-tailed Student's t-tests. For Figure 6C and D, one-way ANOVA analysis was performed. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

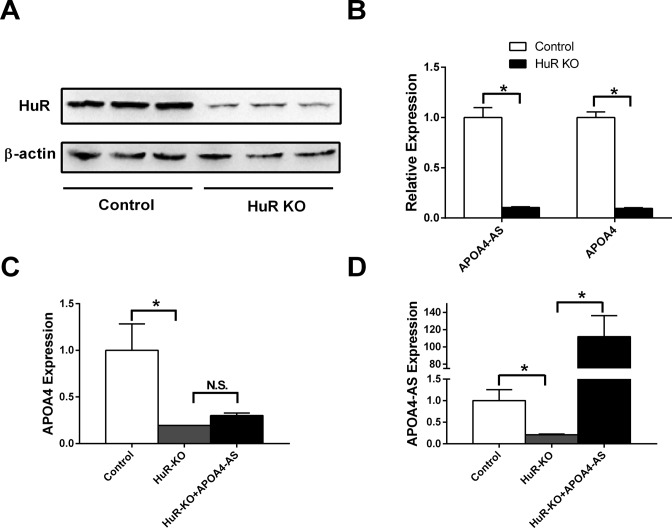

Figure 6.

Deletion of HuR decreases both APOA4-AS and APOA4 mRNA in primary hepatocytes. Primary hepatocytes were isolated from C57BL/6 mice. Cells were infected with ad-Cas9 and two different ad-sgRNAs adenovirus targeting to HuR. (A) HuR and β-actin protein levels were measured by western blot. (B) APOA4-AS and APOA4 transcripts were measured by qRT-PCR. (C) and (D) Hepatocytes with HuR deletion were infected with APOA4-AS adenovirus. APOA4 (C) and APOA4-AS (D) transcripts were measured by qRT-PCR. n = 4–6. *P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Identification and characterization of an antisense lncRNA (APOA4-AS) at APOA4 gene locus

In an attempt to investigate the lncRNA expression profile in the liver, specifically those associated with lipid metabolisms, we analyzed a previously published RNA-seq dataset from the WT and db/db mice liver, which were originally designed to identify genes associated with glucose metabolism and involved in the development of type 2 diabetes (28). Here, both RNA-seq reads were mapped to mouse genome (GRCm38/mm10) by TopHat and assembled against annotated lncRNA library (gencode vM2 long non-coding RNAs library) by Cufflinks (22,29). Cuffdiff and CummeRbund were further utilized to analyze the differentially regulated lncRNAs in the liver between WT and db/db mice. Fifteen uncharacterized lncRNAs were then identified and shown to be dysregulated in the liver of db/db mice (Figure 1A). In an effort to analyze the systemic network and pathways in which lncRNA-associated mRNAs were involved, lncRNA-neighboring protein coding genes were selected to perform gene enrichment analysis (Gene Ontology: http://geneontology.org/). GO analysis focuses on the biological process, molecular function and cellular component that lncRNA-neighboring mRNAs are involved in. GO analysis showed that the lncRNA-neighboring mRNAs are associated with the lipid metabolism (Supplementary Figure S1).

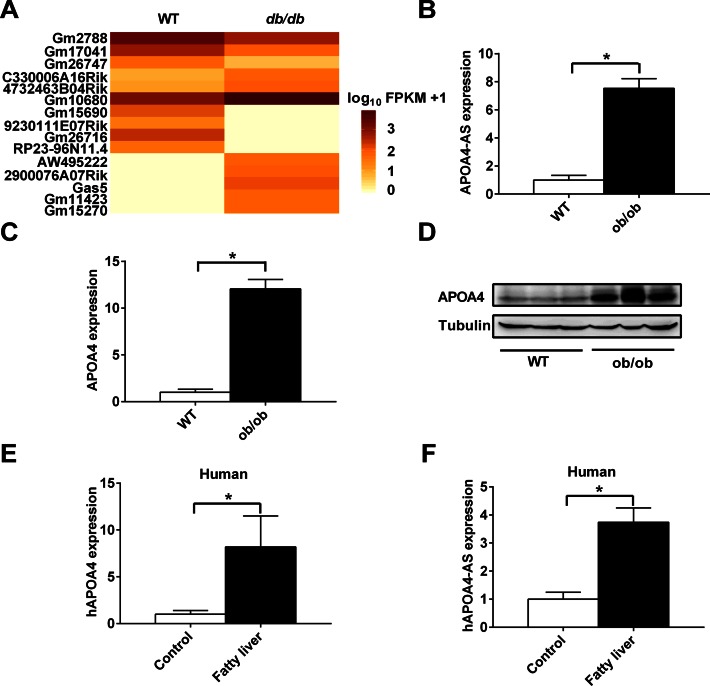

Figure 1.

Identification of lncRNAs differentially expressed in the liver of obese mice. (A) The cluster heat map shows lncRNAs with expression change fold >5 from RNA-seq data (P < 0.05). (B–D) WT and ob/ob mice were fed with normal chow diet for 14 weeks. APOA4-AS (B) and APOA4 transcripts (C) in the liver were measured by qRT-PCR. APOA4 protein level in the liver was measured by Western blot (D). Expression analysis of hAPOA4 (E) and hAPOA4-AS (F) in human fatty and normal liver tissues. n = 5–8. *P < 0.05.

Among the dysregulated lncRNAs, Gm10680 is highly upregulated in db/db mice liver. Retrieving the sequence and genome wide location from the Ensembl Genome Browser (www.ensembl.org/) database, the putative GM10680 (− strand) is transcribed from the opposite strand of APOA4 locus (+ strand), partially overlaps with APOA4 exon 3 and 3′-UTR (chr9:46 242 621–46 243 529) and contains two exons and one intron (Supplementary Figure S2). Therefore, we named GM10680 as APOA4 antisense transcript (APOA4-AS).

APOA4-AS was identified to be highly induced in diabetic mouse liver. To measure the expression level of APOA4-AS, we designed APOA4-AS-specific qPCR primers, spanning the intron region. Our results showed that our qPCR primers specifically detected the non-adenylated APOA4-AS (Supplementary Figure S3A and B). Furthermore, we measured the APOA4-AS expression level in both WT and obese mice liver showing that APOA4-AS transcript was increased by ∼7.5-fold (Figure 1B) and concordantly, APOA4 mRNA level was increased by ∼12-fold in ob/ob mice compared with that of WT mice (Figure 1C). APOA4 protein level was also dramatically increased (Figure 1D).

Human APOA4 expression and synthesis are only confined to the intestine (30). Compared with rodents, such as mouse and rat, APOA4 expression is barely detected in the human liver (30). However, we demonstrated that APOA4 expression was highly induced in the liver of human with fatty liver disease (Figure 1E). Thus, we speculated that whether the human APOA4-AS transcript may exit and its expression also correlates with that of APOA4. By analyzing the human liver RNA-seq data from database (https://www.encodeproject.org/), we observed the sequencing peaks in Integrative Genomics Viewer (Data access number: ENCSR285LDX) from the opposite strand of APOA4 in a similar region of mouse APOA4-AS (data not shown). To further characterize the expression of APOA4-AS in human liver samples, we showed that hAPOA4-AS transcript level was also significantly increased in the liver of human with fatty liver disease (Figure 1F). These data demonstrate that both hAPOA4-AS and hAPOA4 can be induced by lipid accumulation, and could potentially be used as biomarkers for fatty liver disease.

Putative APOA4-AS sequence in both Ensembl and UCSC Genome Database contains two exons and one intron. However, by performing coding potential analysis, the predicted APOA4-AS (previously annotated as GM10680) cDNA sequence in both database has coding potential assessed by Coding Potential Assessment Tool (CPAT) (Supplementary Table S2). Next, we performed 5′ RACE to determine whether APOA4-AS cDNA contains the intron. It was shown that in C57B/L6 mouse liver, APOA4-AS transcript contains intron and the intron-containing full length transcript (blue color highlighted intron sequencing from the database does present in our RACE determined new APOA4-AS transcript sequencing in Supplementary Figure S2) is an ∼900-nt non-coding RNA assessed by CPAT (Supplementary Table S2) while the protein coding mRNA APOA4, APOC3 and APOA5 were predicted to have protein-coding potential utilizing the same prediction setting for CPAT (Supplementary Table S2). Furthermore, the full-length APOA4-AS failed to express any protein using in vitro translation assay (Figure 2A).

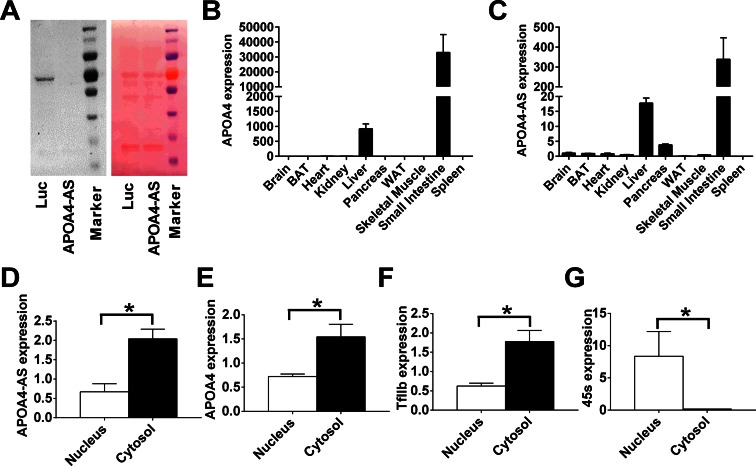

Figure 2.

Characterization of the non-coding property, expression profile and cellular location of APOA4-AS. (A) In vitro translation assay using luciferase (Luc) and APOA4-AS RNA. Strep-HRP detection of translational incorporation of biotinylated lysine (left). The same membrane was stained by Ponceau S (right). (B) and (C) Expression analysis of APOA4 and APOA4-AS in 10 mouse tissues. (D–G) Expression of APOA4-AS, APOA4, TfIIb and 45s in isolated cytosol and nucleus from primary hepatocytes. n = 4–6. *P < 0.05.

Next, we examined the expression profile of both APOA4 and APOA4-AS across 10 tissues by qRT-PCR, showing that APOA4 is majorly detected in both the small intestine and liver (Figure 2B) as reported before (7), and APOA4-AS is also significantly enriched in the small intestine and liver, while it is barely detected in other tissues, such as the brain, heart and kidney (Figure 2C). Meanwhile, our northern blot also confirmed that APOA4-AS is an ∼900-nt transcript that is only expressed in the small intestine and liver (Supplementary Figure S4). Both APOA4-AS and APOA4 show a similar expression pattern, suggesting that functionally related mechanisms may present between these two transcripts.

To further determine the cellular localization of APOA4-AS transcript, the nuclear and cytosolic RNAs were isolated from primary hepatocytes, and the expressions of APOA4-AS and APOA4 transcripts in both subcellular locations were measured. qRT-PCR data show that both APOA4-AS and APOA4 transcripts are highly expressed in the cytosol compared with that in the nucleus (Figure 2D and E). As control, TfIIb mRNA is specifically located in the cytosol (Figure 2F), whereas 45S ribosomal RNA precursor is primarily located in the nucleus (Figure 2G).

APOA4-AS is an essential component to maintain APOA4 expression both in vitro and in vivo

We have shown that both APOA4-AS and APOA4 transcripts are localized in cytosol. To investigate whether the APOA4-AS transcript is associated with the expression of APOA4, we designed two distinct adenovirus-based shRNAs targeting to APOA4-AS transcript. Adenovirus-mediated expression of the shAPOA4-AS1 or shAPOA4-AS2 in primary hepatocytes resulted in a significant reduction of not only the targeted APOA4-AS transcript (Figure 3A) but also APOA4 mRNA and protein levels (Figure 3B and C). Two distinct APOA4-AS shRNA molecules that specifically target to the APOA4-AS transcript resulted in concomitant reduction of APOA4 expression, which suggests that APOA4-AS may regulate the expression of APOA4 at both the mRNA and the protein levels in primary hepatocytes.

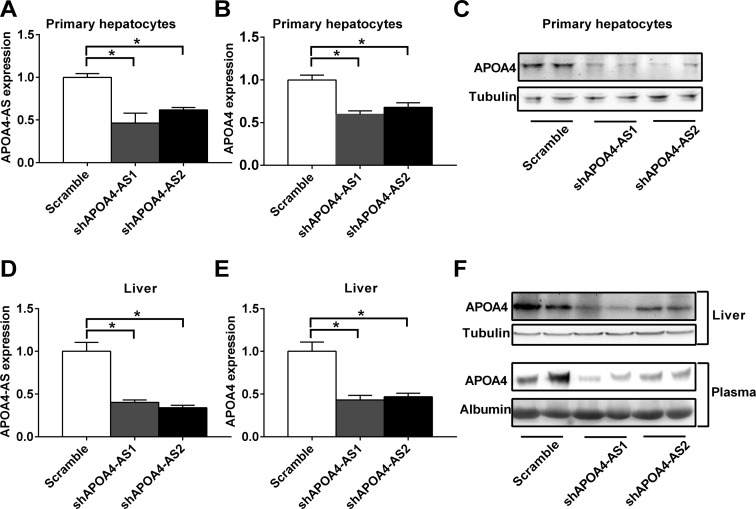

Figure 3.

Knockdown of APOA4-AS transcript decreases APOA4 mRNA and protein levels both in vitro and in vivo. (A–C) Primary hepatocytes were isolated from C57BL/6 mice. Cells were infected with ad-scramble or two different ad-shRNAs (shAPOA4-AS1 or shAPOA4-AS2) adenovirus targeting to APOA4-AS transcript. APOA4-AS (A) and APOA4 (B) transcripts were measured by qRT-PCR. APOA4 protein level was measured by western blot (C). (D–F) C57BL/6 mice (8 weeks old) were tail-vein injected with ad-scramble or two different ad-shRNAs (shAPOA4-AS1 or shAPOA4-AS2) adenovirus targeting APOA4-AS transcript. APOA4-AS (D) and APOA4 transcripts (E) in the liver were measured by qRT-PCR. APOA4 protein levels in the liver and plasma were measured by western blot (F). n = 3–6. *P < 0.05.

To further determine whether APOA4-AS regulates APOA4 mRNA and protein levels in vivo, we generated liver-specific APOA4-AS knockdown mice by tail-vein injection of two individual purified adenovirus particles carrying APOA4-AS shRNA (shAPOA4-AS1 or shAPOA4-AS2). Consistently, either shAPOA4-AS1 or shAPOA4-AS2 significantly reduced APOA4-AS transcript level as well as APOA4 mRNA and protein levels in mouse liver (Figure 3D–F). Furthermore, the plasma APOA4 protein level in APOA4-AS liver-specific knockdown mice was significantly reduced (Figure 3F). Therefore, these data demonstrate that APOA4-AS is an essential component to stabilize APOA4 expression both in vitro and in vivo.

APOA4 gene is a part of the gene cluster that also includes APOA1, APOC3 and APOA5 involving in lipid metabolism (13,15). Recent study has shown that APOA1-AS could negatively regulate APOA1, APOA4 and APOC3 expression at transcription level (31). Here, we showed that manipulation of APOA4-AS expression does not affect the expression level of APOA1, APOC3 or APOA5 mRNA both in vitro and in vivo (Supplementary Figure S5), providing strong evidence to support the specificity of APOA4-AS to regulate APOA4 expression.

Liver-specific knockdown of APOA4-AS decreases APOA4 expression and reduces plasma TG and TC level in ob/ob mice

Consistent with the observation we made in WT mice, we also noted that knockdown of APOA4-AS in the liver of ob/ob mice by shRNA dramatically decreased APOA4 mRNA and protein levels (Figure 4A and B). However, the expression of other lipid metabolism associated genes (e.g. FASN, SCD1, APOB, MTP, CPT1α and MCAD) was not altered (Figure 4B). These data demonstrate that similar regulatory mechanisms may exist between APOA4-AS and APOA4 in both healthy and obese conditions.

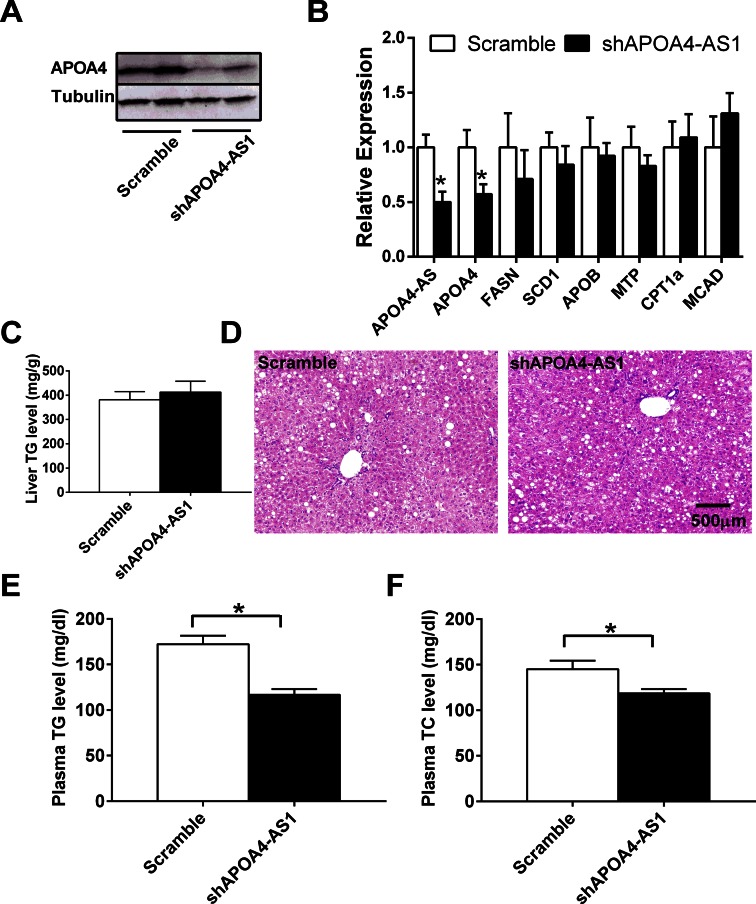

Figure 4.

Knockdown of APOA4-AS in ob/ob mice decreases APOA4 expression and plasma TG and TC levels without affecting steatosis. ob/ob mice (8 weeks old) were tail-vein injected ad-scramble or ad-shAPOA4-AS1 purified adenovirus. Mice were sacrificed at 10–12 days after adenovirus injection. (A) APOA4 and tubulin were measured by western blot. (B) APOA4-AS, APOA4, FASN, SCD1, APOB, MTP, CPT1a and MCAD transcripts in the liver were measured by qRT-PCR. (C) Liver TG level. (D) H&E staining of liver sections. (E) Plasma TG levels. (F) Plasma TC levels. n = 5–6. *P < 0.05.

It has been shown before that APOA4 regulates hepatic TG secretion (16). To assess whether APOA4-AS may regulate hepatic TG homeostasis, we measured liver TG, plasma TG and TC levels in liver-specific APOA4-AS knockdown ob/ob mice and control ob/ob mice. We did not observe any change in liver TG level and steatosis (Figure 4C and D). However, plasma TG and TC levels were significantly reduced by 32.3 and 18%, respectively, in liver-specific APOA4-AS knockdown of ob/ob mice (Figure 4E and F). These data suggest that APOA4-AS stabilizes APOA4 in obesity contributing to hypertriglyceridemia.

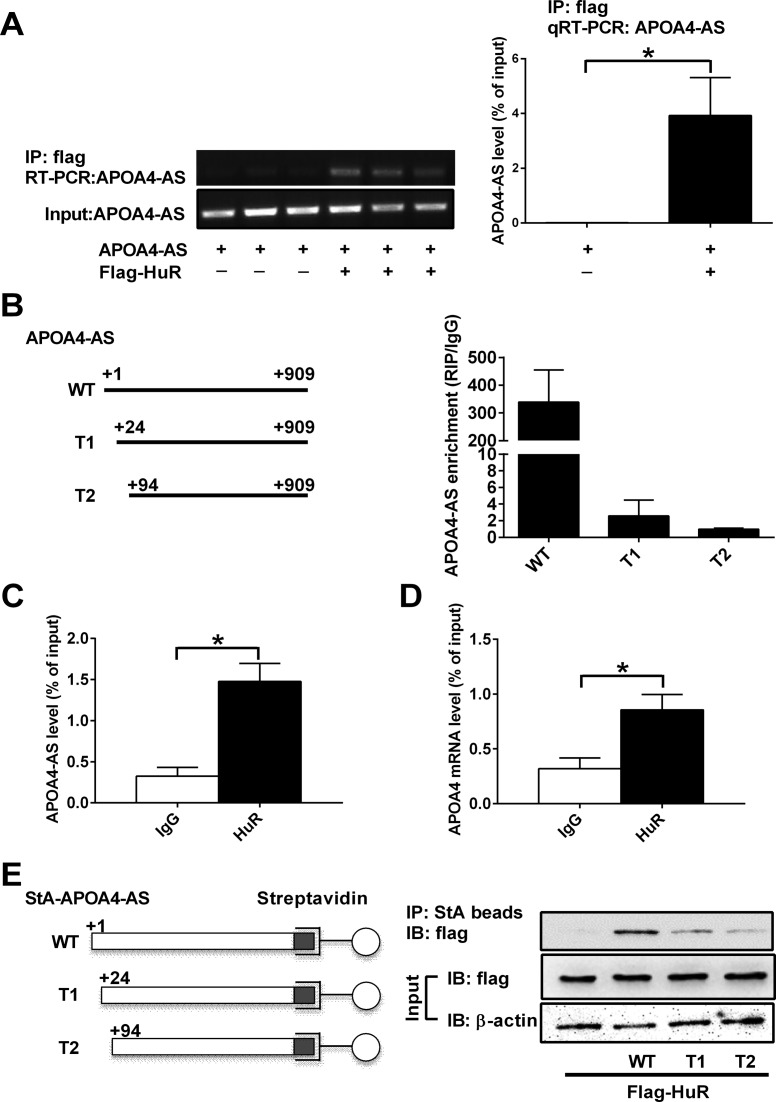

APOA4-AS directly binds mRNA stabilizing protein HuR

Antisense transcript stabilizes sense mRNA through extended base-pairing or physical interaction with mRNA stabilizing protein. One of the mRNA stabilizing proteins is HuR whose expression in the liver has been reported before (32,33). APOA4-AS contains two HuR binding sites (Supplementary Figure S2). To determine whether APOA4-AS directly binds to mRNA stabilizing protein HuR, we transiently transfected human embryonic kidney 293T (HEK293T) cells with vectors expressing APOA4-AS transcript and flag-tagged HuR, followed with IP using anti-Flag agarose beads. Semi-quantitative RT-PCR and qRT-PCR analyses indicated that APOA4-AS presents in the HuR immunocomplex (Figure 5A). To further determine whether predicted HuR binding sites are essential for APOA4-AS and HuR interaction, one or two HuR binding sites were deleted in truncation 1 (T1) or 2 (T2) isoforms of APOA4-AS. Sequence (+1 to +24) and (+1 to +94) was deleted in T1 or T2, respectively. RNA immunoprecipitation (RIP) assay showed that these two sites are important for the interaction between APOA4-AS and HuR (Figure 5B). Furthermore, RIP-qRT-PCR assay showed that endogenous APOA4-AS and APOA4 transcripts form a complex with endogenous HuR in mouse liver (Figure 5C and D). To confirm this physical interaction, we constructed three plasmids expressing APOA4-AS WT, T1 or T2 isoform, respectively, fused to streptavidin-binding aptamer (StA-APOA4-AS WT, T1 and T2), a 60-nt RNA tag that mimics biotin and binds to streptavidin with high affinity (34). Streptavidin precipitation of lysates from HEK293T cells transiently transfected with HuR alone or in combination with StA-APOA4-AS (WT, T1 or T2) revealed that HuR was only detected in the APOA4-AS (WT) RNA complexes (Figure 5E). The amount of HuR in APOA4-AS T1 or T2 RNA complexes was dramatically reduced (Figure 5E). These data demonstrate that APOA4-AS directly binds to HuR, which may contribute to APOA4 mRNA stabilization.

Figure 5.

APOA4-AS transcript interacts with mRNA stabilizing protein HuR. (A) Semi-quantitative RT-PCR (left) analyses of APOA4-AS in RNA isolated from a-flag immunocomplex (top) or input (bottom) from transiently transfected HEK293T cells. qRT-PCR analyses (right) were also performed by using the same samples and normalized by input. (B) Flag-HuR was co-transfected with APOA4-AS WT or two truncated APOA4-AS (T1 or T2) in HEK293T cells. APOA4-AS enrichment in flag immunocomplex was present by RIP/IgG. (C) and (D) qRT-PCR analyses of endogenous APOA4-AS and APOA4 transcripts in the HuR immunocomplex from mouse liver. (E) Immunoblots of Flag-HuR after strepavidin-APOA4-AS (StA-APOA4-AS) precipitation from transfected HEK293T cell lysates. Schematic diagrams of StA-APOA4-AS are shown on the right. n = 3–5. *P < 0.05.

Deletion of HuR decreases both APOA4-AS and APOA4 expression

To further determine whether HuR affects the stability of APOA4-AS and APOA4 expression, CRISPR/Cas9 mediated deletion of HuR was performed. As shown in Figure 6A, HuR was dramatically reduced by CRISPR/Cas9 mediated gene editing. The expression of APOA4-AS and APOA4 was reduced by 89.6 and 90.5%, respectively (Figure 6B). Overexpression of APOA4-AS in HuR deleted hepatocytes could barely increase APOA4 expression (Figure 6C and D). These data indicate that HuR is an essential component to stabilize both APOA4-AS and APOA4 transcripts, and APOA4-AS regulates APOA4 expression depending on HuR.

DISCUSSION

APOA4 controls multiple metabolic pathways including fat absorption (35), food intake (36), energy expenditure (37), TG secretion (16), insulin secretion (17) and hepatic glucose production (18), and its expression is also tightly regulated by metabolic state. High fat diet or steatosis increases APOA4 level in the liver, while the deletion of APOA4 leads to a reduction of the plasma level of TG (16,38). At molecular level, CREBH, CREB3, ERRa and PPARa drive the expression of APOA4 (21,39,40). In current investigation, we demonstrate that APOA4-AS, a long non-coding antisense transcript for APOA4, functions as a concordant regulator of APOA4 gene expression and plays a role in regulating plasma TG and TC levels. We present data showing that APOA4-AS is co-expressed with APOA4 in the liver, and HuR–APOA4-AS complex specifically regulates APOA4 expression both in vitro and in vivo.

lncRNAs are involved in lipid homeostasis (41). We initially discovered a subset of lncRNAs dysregulated in the liver of db/db mice, an obese mice model with leptin receptor deficiency. The GO analysis of dysregulated lncRNAs-neighboring mRNAs indicates that these mRNAs are majorly involved in TG and cholesterol metabolism, especially the TG catabolism, suggesting that these dysregulated lncRNAs may be related to TG and cholesterol metabolism.

Among the 15 dysregulated lncRNAs, we found that APOA4-AS is co-elevated with APOA4 in the liver of ob/ob mice, another obese mice model with leptin deficiency. Both hepatic APOA4-AS and APOA4 are also abnormally elevated in ob/ob mice compared with that in WT mice. This observation is consistent with previous reports that hepatic APOA4 expression is positively associated with liver TG accumulation (16) indicating that APOA4-AS may be associated with APOA4 expression and involved in TG metabolism. APOA4 could enhance hepatic TG secretion and increase plasma TG level in mice (16). We also found that in ob/ob mice, knockdown of APOA4-AS not only reduced APOA4 expression but also significantly decreased plasma TG and TC levels. However, knockdown of APOA4-AS in ob/ob mice did not affect liver TG level, which indicates that the primary role of APOA4 in the liver is to assist hepatic TG secretion, but not TG accumulation (16).

To delve into the regulatory mechanism of APOA4-AS on APOA4, we manipulated the expression level of APOA4-AS both in vitro and in vivo, demonstrating that APOA4-AS is closely associated with the APOA4 mRNA stability, possible through the extended overlap region between lncRNA and mRNA to further assist the mRNA stability. Further mechanistic investigation revealed HuR (an mRNA stabilizing protein) involved in this process. Our study first determined that both APOA4-AS and APOA4 transcripts are present in cytosol of primary hepatocytes. shRNA-mediated APOA4-AS knockdown decreases APOA4 mRNA level, suggesting that APOA4-AS may stabilizes sense APOA4 mRNA through extended base-pairing with sense mRNA at APOA4 3′-end to prevent mRNA from 3′ exonuclease-mediated decay (42). Previously, a study performing 3′ region extraction and deep sequencing (3′ READS) identified that in mammalian cells about 66% long non-coding RNA genes are polyadenylated (43). In current investigation, we noted that cDNA synthesis of APOA4-AS by oligo (dT) was failed unless polyadenylation reaction is performed or random hexamer is utilized (Supplementary Figure S3B), suggesting that APOA4-AS transcript is non-polyadenylated and requires additional RNA stabilization protein to prevent exonuclease-mediated RNA decay. Here, through bioinformatics analysis, we identified two putative HuR binding sites in the sequence of 5′ end of APOA4-AS. Truncated APOA4-AS with deletion of HuR binding site abolished the HuR-binding to APOA4-AS. Deletion of HuR by CRISPR/Cas9 medicated gene editing dramatically reduced both APOA4-AS and APOA4 transcripts. We also showed that in in vitro cultured mouse hepatocyte treated with Actinomycin D (ActD), a transcriptional inhibitor, shows that APOA4-AS is more stable than APOA4 transcript (Supplementary Figure S3C). These data all together demonstrate that HuR is essential for the stability of APOA4-AS and APOA4 transcripts, and APOA4-AS RNA may recruit HuR to form a complex with APOA4 mRNA.

In summary, our work reveals a novel mechanism by which HuR–APOA4-AS complex stabilizes APOA4 mRNA. APOA4-AS could be a potential therapeutic target for metabolic diseases.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Liangyou Rui (University of Michigan) for kindly providing ob+/- mice, Dr. Yanjing Zhang for vector cloning and Dr. Li Liu (Nanfang Hosipital, Southern Medical University, China) for nicely providing flag-HuR construct. Liwei Xie together with all authors thank Dr. Hang Yin (University of Georgia) for support of the studies proposed in this manuscript.

Footnotes

Present address: Liwei Xie, Center for Molecular Medicine, University of Georgia, Athens, GA 30602, USA.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online.

FUNDING

Changbai Mountain Scholars Program of The People's Government of Jilin Province [2013046 to Z.C.]; Jilin Talent Development Foundation [111860000 to Z.C.]; Jilin Science and Technology Development Program [20160101204JC to Z.C.]; Fok Ying Tong Education Foundation [151022 to Z.C.]; National Natural Science Foundation of China [31500957 to Z.C., 31470798 to Y.Z.]; American Heart Association [16POST26400005 to L.X.]; Northeast Normal University [120401204 to Z.C.]. Funding for open access charge: Changbai Mountain Scholars Program of The People's Government of Jilin Province [2013046].

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Derrien T., Johnson R., Bussotti G., Tanzer A., Djebali S., Tilgner H., Guernec G., Martin D., Merkel A., Knowles D.G., et al. The GENCODE v7 catalog of human long noncoding RNAs: analysis of their gene structure, evolution, and expression. Genome research. 2012;22:1775–1789. doi: 10.1101/gr.132159.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Katayama S., Tomaru Y., Kasukawa T., Waki K., Nakanishi M., Nakamura M., Nishida H., Yap C.C., Suzuki M., Kawai J., et al. Antisense transcription in the mammalian transcriptome. Science. 2005;309:1564–1566. doi: 10.1126/science.1112009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khorkova O., Myers A.J., Hsiao J., Wahlestedt C. Natural antisense transcripts. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2014;23:R54–R63. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddu207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tseng Y.Y., Moriarity B.S., Gong W., Akiyama R., Tiwari A., Kawakami H., Ronning P., Reuland B., Guenther K., Beadnell T.C., et al. PVT1 dependence in cancer with MYC copy-number increase. Nature. 2014;512:82–86. doi: 10.1038/nature13311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mirza A.H., Kaur S., Brorsson C.A., Pociot F. Effects of GWAS-Associated Genetic Variants on lncRNAs within IBD and T1D Candidate Loci. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e105723. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0105723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reddy M.A., Chen Z., Park J.T., Wang M., Lanting L., Zhang Q., Bhatt K., Leung A., Wu X., Putta S., et al. Regulation of inflammatory phenotype in macrophages by a diabetes-induced long noncoding RNA. Diabetes. 2014;63:4249–4261. doi: 10.2337/db14-0298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang F., Kohan A.B., Lo C.M., Liu M., Howles P., Tso P. Apolipoprotein A-IV: a protein intimately involved in metabolism. J. Lipid Res. 2015;56:1403–1418. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R052753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duverger N., Tremp G., Caillaud J.M., Emmanuel F., Castro G., Fruchart J.C., Steinmetz A., Denefle P. Protection against atherogenesis in mice mediated by human apolipoprotein A-IV. Science. 1996;273:966–968. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5277.966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Recalde D., Ostos M.A., Badell E., Garcia-Otin A.L., Pidoux J., Castro G., Zakin M.M., Scott-Algara D. Human apolipoprotein A-IV reduces secretion of proinflammatory cytokines and atherosclerotic effects of a chronic infection mimicked by lipopolysaccharide. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2004;24:756–761. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000119353.03690.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khovidhunkit W., Duchateau P.N., Medzihradszky K.F., Moser A.H., Naya-Vigne J., Shigenaga J.K., Kane J.P., Grunfeld C., Feingold K.R. Apolipoproteins A-IV and A-V are acute-phase proteins in mouse HDL. Atherosclerosis. 2004;176:37–44. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2004.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boerwinkle E., Visvikis S., Chan L. Two polymorphisms for amino acid substitutions in the APOA4 gene. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:4966. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.16.4966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dallongeville J., Delcroix A.G., Wagner A., Ducimetiere P., Ruidavets J.B., Arveiler D., Bingham A., Ferrieres J., Amouyel P., Meirhaeghe A. The APOA4 Thr347->Ser347 polymorphism is not a major risk factor of obesity. Obes. Res. 2005;13:2132–2138. doi: 10.1038/oby.2005.264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gomez P., Perez-Martinez P., Marin C., Camargo A., Yubero-Serrano E.M., Garcia-Rios A., Rodriguez F., Delgado-Lista J., Perez-Jimenez F., Lopez-Miranda J. APOA1 and APOA4 gene polymorphisms influence the effects of dietary fat on LDL particle size and oxidation in healthy young adults. J. Nutr. 2010;140:773–778. doi: 10.3945/jn.109.115964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guclu-Geyik F., Onat A., Coban N., Komurcu-Bayrak E., Sansoy V., Can G., Erginel-Unaltuna N. Minor allele of the APOA4 gene T347S polymorphism predisposes to obesity in postmenopausal Turkish women. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2012;39:10907–10914. doi: 10.1007/s11033-012-1990-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Herron K.L., Lofgren I.E., Adiconis X., Ordovas J.M., Fernandez M.L. Associations between plasma lipid parameters and APOC3 and APOA4 genotypes in a healthy population are independent of dietary cholesterol intake. Atherosclerosis. 2006;184:113–120. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2005.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.VerHague M.A., Cheng D., Weinberg R.B., Shelness G.S. Apolipoprotein A-IV expression in mouse liver enhances triglyceride secretion and reduces hepatic lipid content by promoting very low density lipoprotein particle expansion. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2013;33:2501–2508. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.113.301948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang F., Kohan A.B., Kindel T.L., Corbin K.L., Nunemaker C.S., Obici S., Woods S.C., Davidson W.S., Tso P. Apolipoprotein A-IV improves glucose homeostasis by enhancing insulin secretion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2012;109:9641–9646. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1201433109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li X., Xu M., Wang F., Kohan A.B., Haas M.K., Yang Q., Lou D., Obici S., Davidson W.S., Tso P. Apolipoprotein A-IV reduces hepatic gluconeogenesis through nuclear receptor NR1D1. J. Biol. Chem. 2014;289:2396–2404. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.511766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sleddering M.A., Markvoort A.J., Dharuri H.K., Jeyakar S., Snel M., Juhasz P., Lynch M., Hines W., Li X., Jazet I.M., et al. Proteomic analysis in type 2 diabetes patients before and after a very low calorie diet reveals potential disease state and intervention specific biomarkers. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e112835. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0112835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sanecka A., Ansems M., van Hout-Kuijer M.A., Looman M.W., Prosser A.C., Welten S., Gilissen C., Sama I.E., Huynen M.A., Veltman J.A., et al. Analysis of genes regulated by the transcription factor LUMAN identifies ApoA4 as a target gene in dendritic cells. Mol. Immunol. 2012;50:66–73. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2011.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xu X., Park J.-G., So J.-S., Hur K.Y., Lee A.-H. Transcriptional regulation of apolipoprotein A-IV by the transcription factor CREBH. J. Lipid Res. 2014;55:850–859. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M045104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Trapnell C., Roberts A., Goff L., Pertea G., Kim D., Kelley D.R., Pimentel H., Salzberg S.L., Rinn J.L., Pachter L. Differential gene and transcript expression analysis of RNA-seq experiments with TopHat and Cufflinks. Nat. Protoc. 2012;7:562–578. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2012.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen Z., Shen H., Sun C., Yin L., Tang F., Zheng P., Liu Y., Brink R., Rui L. Myeloid cell TRAF3 promotes metabolic inflammation, insulin resistance, and hepatic steatosis in obesity. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2015;308:E460–E469. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00470.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen Z., Sheng L., Shen H., Zhao Y., Wang S., Brink R., Rui L. Hepatic TRAF2 regulates glucose metabolism through enhancing glucagon responses. Diabetes. 2012;61:566–573. doi: 10.2337/db11-0474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen Z., Canet M.J., Sheng L., Jiang L., Xiong Y., Yin L., Rui L. Hepatocyte TRAF3 promotes insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes in mice with obesity. Mol. Metab. 2015;4:951–960. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2015.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maggio I., Holkers M., Liu J., Janssen J.M., Chen X., Gonçalves M.A.F.V. Adenoviral vector delivery of RNA-guided CRISPR/Cas9 nuclease complexes induces targeted mutagenesis in a diverse array of human cells. Sci. Rep. 2014;4:5105. doi: 10.1038/srep05105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhou Y., Zhu S., Cai C., Yuan P., Li C., Huang Y., Wei W. High-throughput screening of a CRISPR/Cas9 library for functional genomics in human cells. Nature. 2014;509:487–491. doi: 10.1038/nature13166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang F., Xu X., Zhang Y., Zhou B., He Z., Zhai Q. Gene expression profile analysis of type 2 diabetic mouse liver. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e57766. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mudge J.M., Harrow J. Creating reference gene annotation for the mouse C57BL6/J genome assembly. Mamm. Genome. 2015;26:366–378. doi: 10.1007/s00335-015-9583-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kohan A.B., Wang F., Lo C.-M., Liu M., Tso P. ApoA-IV: current and emerging roles in intestinal lipid metabolism, glucose homeostasis, and satiety. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2015;308:G472–G481. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00098.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Halley P., Kadakkuzha B.M., Faghihi M.A., Magistri M., Zeier Z., Khorkova O., Coito C., Hsiao J., Lawrence M., Wahlestedt C. Regulation of the apolipoprotein gene cluster by a long noncoding RNA. Cell Rep. 2014;6:222–230. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cao C., Sun J., Zhang D., Guo X., Xie L., Li X., Wu D., Liu L. The long intergenic noncoding RNA UFC1, a target of MicroRNA 34a, interacts with the mRNA stabilizing protein HuR to increase levels of beta-catenin in HCC cells. Gastroenterology. 2015;148:415–426. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bartolome N., Aspichueta P., Martinez M.J., Vazquez-Chantada M., Martinez-Chantar M.L., Ochoa B., Chico Y. Biphasic adaptative responses in VLDL metabolism and lipoprotein homeostasis during Gram-negative endotoxemia. Innate Immun. 2012;18:89–99. doi: 10.1177/1753425910390722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Leppek K., Stoecklin G. An optimized streptavidin-binding RNA aptamer for purification of ribonucleoprotein complexes identifies novel ARE-binding proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:e13. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kohan A.B., Wang F., Li X., Bradshaw S., Yang Q., Caldwell J.L., Bullock T.M., Tso P. Apolipoprotein A-IV regulates chylomicron metabolism-mechanism and function. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2012;302:G628–G636. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00225.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fujimoto K., Fukagawa K., Sakata T., Tso P. Suppression of food intake by apolipoprotein A-IV is mediated through the central nervous system in rats. J. Clin. Invest. 1993;91:1830–1833. doi: 10.1172/JCI116395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shen L., Pearson K.J., Xiong Y., Lo C.M., Tso P., Woods S.C., Davidson W.S., Liu M. Characterization of apolipoprotein A-IV in brain areas involved in energy homeostasis. Physiol. Behav. 2008;95:161–167. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2008.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weinstock P.H., Bisgaier C.L., Hayek T., Aalto-Setala K., Sehayek E., Wu L., Sheiffele P., Merkel M., Essenburg A.D., Breslow J.L. Decreased HDL cholesterol levels but normal lipid absorption, growth, and feeding behavior in apolipoprotein A-IV knockout mice. J. Lipid Res. 1997;38:1782–1794. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Carrier J.C., Deblois G., Champigny C., Levy E., Giguère V. Estrogen-related receptor α (ERRα) is a transcriptional regulator of apolipoprotein A-IV and controls lipid handling in the intestine. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:52052–52058. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410337200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nagasawa M., Hara T., Kashino A., Akasaka Y., Ide T., Murakami K. Identification of a functional peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) response element (PPRE) in the human apolipoprotein A-IV gene. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2009;78:523–530. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2009.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen Z. Progress and prospects of long noncoding RNAs in lipid homeostasis. Mol. Metab. 2016;5:164–170. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2015.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Houseley J., Tollervey D. The many pathways of RNA degradation. Cell. 2009;136:763–776. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hoque M., Ji Z., Zheng D., Luo W., Li W., You B., Park J.Y., Yehia G., Tian B. Analysis of alternative cleavage and polyadenylation by 3′ region extraction and deep sequencing. Nat. Methods. 2013;10:133–139. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.