Abstract

N2-methylguanosine is one of the most universal modified nucleosides required for proper function in transfer RNA (tRNA) molecules. In archaeal tRNA species, a specific S-adenosyl-L-methionine (SAM)-dependent tRNA methyltransferase (MTase), aTrm11, catalyzes formation of N2-methylguanosine and N2,N2-dimethylguanosine at position 10. Here, we report the first X-ray crystal structures of aTrm11 from Thermococcus kodakarensis (Tko), of the apo-form, and of its complex with SAM. The structures show that TkoTrm11 consists of three domains: an N-terminal ferredoxinlike domain (NFLD), THUMP domain and Rossmann-fold MTase (RFM) domain. A linker region connects the THUMP-NFLD and RFM domains. One SAM molecule is bound in the pocket of the RFM domain, suggesting that TkoTrm11 uses a catalytic mechanism similar to that of other tRNA MTases containing an RFM domain. Furthermore, the conformation of NFLD and THUMP domains in TkoTrm11 resembles that of other tRNA-modifying enzymes specifically recognizing the tRNA acceptor stem. Our docking model of TkoTrm11-SAM in complex with tRNA, combined with biochemical analyses and pre-existing evidence, provides insights into the substrate tRNA recognition mechanism: The THUMP domain recognizes a 3′-ACCA end, and the linker region and RFM domain recognize the T-stem, acceptor stem and V-loop of tRNA, thereby causing TkoTrm11 to specifically identify its methylation site.

INTRODUCTION

Transfer RNA (tRNA) plays a crucial role as the adapter molecule that translates genetic information from messenger RNA (mRNA) to protein. Nascent precursor (pre)-tRNAs must be processed for the maturation of tRNAs. The maturated tRNAs are required for protein synthesis on ribosomes. In the maturation process of archaeal/eukaryotic pre-tRNA molecules, many tRNA maturation factors, which include enzymes and RNA–protein complexes, are responsible for tRNA splicing, processing and modifications.

An enormous number and variety of tRNA modification enzymes have been identified and characterized, and numerous modified nucleosides are more often found in tRNA molecules than in other RNA species (mRNA, ribosomal RNA (rRNA) and small RNA) (1,2). These modified nucleosides are mostly responsible for the stabilization of L-shaped tRNA structure, as well as the fine-tuning of the decoding of mRNAs during translation, and of numerous interactions between RNA and RNA-binding protein partners (3). On the other hand, several modifications are involved in genetic diseases. Deficiencies of tRNA modifications are linked to human genetic diseases, e.g. intellectual disability, Type II diabetes, mitochondrial myopathy and sideroblastic anemia, etc (4,5). Extensive studies of tRNA modification machineries at a molecular level are needed to better understand related human pathologies and provide clues for the design of therapies to treat human genetic diseases.

Methylation is one of the most ubiquitous and abundant kinds of nucleoside modifications and is part of the biosynthetic pathways of the majority of tRNA hypomodifications (1,2,6). In archaea and eukaryotes, small nucleolar (sno) RNAPs in complex with guide sno RNAs produce not only methylation of the 2′-O ribose position but also the psudouridylation of uridine in tRNA/rRNAs (7). In most cases, however, specific RNA methyltransferases (MTases) strictly methylate bases and 2′-O ribose sugars at precise positions in various RNA species (8). The RNA MTases are classified into four superfamilies: Rossmann-fold MTase (RFM), SPOUT (SpoU and TrmD), radical-S-adenosyl-L-methinonine (SAM) and FAD/NAD(p)-dependent MTase (9). For tRNA MTases, there are two types designated according to the distinct consumption of the methyl group donor: (i) One is the SAM-dependent tRNA MTases, which are further classified by their catalytic domain (10); the class I type includes RFM as the catalytic domain, while the class IV type contains the topological-knot structure, which is universally conserved in a member of the SPOUT superfamily (11). (ii) Second is the folate/FAD/NAD(p)-dependent tRNA MTases, in which TrmFO catalyzes the formation of m5U54 in tRNA using the 5, 10 methylenetetrahydrofolate as a methyl donor in Gram-positive and some Gram-negative eubacteria (12–14). Recent studies have elucidated the mechanisms underlying substrate specificity and catalysis of TrmFO (15–19).

The N2-methylguanosine (m2G) and N2, N2-dimethylguanosine (m22G) are major types of methylated nucleosides. To date, their modifications have been identified at positions 6, 7, 9, 10, 18, 26 and 27 of various tRNAs present in the three domains of life (1,2). Specific SAM-dependent tRNA MTases have been biochemically and structurally characterized for their methylation at the positions 6, 10, 26 and 27 (20–27). Bacterial TrmN and archaeal Trm14 play a catalytic role in the formation of m2G6 nucleoside (20,21); structural information is available for both, and a mechanism for their site specificity has been proposed based on structure-guided mutagenesis studies (27). Archaeal Trm-G10 was first identified in Pyrococcus species (Pyrococcus abyssi (Pab) and Pyrococcus furiosus (Pfu)) and catalyzes the production of m2G10 or m22G10 nucleosides (28). Its eukaryotic homolog Trm11 has been shown to catalyze the formation of m2G10 in tRNAPhe from Saccharomyces cerevisiae (29). Only Trm11, however, is functional when it dimerizes with the ‘hub’ protein Trm112, which can interact and activate not only Trm11 but also the catalytic subunits of other RNA MTases and translational factor (30,31). The X-ray crystal structure determination of Trm-G10 or the Trm11-Trm112 complex has not been achieved yet and therefore the structural mechanisms for their site specificity and catalysis remain elusive.

The genes coding for Trm-G10 and Trm11 belong to the cluster of orthologous group COG1041, exclusively and ubiquitously found in archaea and eukaryotes, and the two proteins share ∼30% sequence similarity (28). Previous reports suggest that Trm-G10 and Trm11 are composed of three domains: an N-terminal ferredoxin like domain (NFLD); a THioUridine synthase, MTase and Pseudouridine synthase domain (THUMP); and a Rossmann-fold MTase catalytic domain (RFM) (28,32–34). Given the structural and functional similarities of archaeal Trm-G10 and eukaryotic Trm11, we have renamed archaeal Trm-G10 to ‘aTrm11’ in this study. The naming of aTrm11 is followed by a standard nomenclature for the tRNA MTases, for example, aTrm56 that catalyzes the formation of Cm56 at position 56 of archaeal tRNA (35). The RFM domain of both Trm11 enzymes is likely to be fused to a THUMP domain that also includes an NFLD responsible for the RNA-binding (28,34,36), and the NFLD is a minimum unit of THUMP domain. Structural studies have revealed that TrmN/Trm14 employ the RFM domain as the catalytic unit, and that one SAM molecule is bound to a pocket of the RFM domain, which is fused to the THUMP domain through a single linker (27). Similar architectures have been found in other tRNA-modifying enzymes consisting of three domains, i.e. where the NFLD and THUMP domain are fused to one catalytic domain. For examples, CDAT8 is a cytidine deaminase responsible for the deamination of U8 in archaeal tRNA species and composed of the NFLD and THUMP domain fused to one deaminase domain (37). The biosynthesis of s4U8 is catalyzed by a 4-thiouridine synthase (ThiI) (32). ThiI constitutes an NFLD and THUMP domain fused to the pyrophoshatase (PPase) domain through single linker (38,39), although ThiI orthologs from γ-proteobacteria and archaeon Thermoplasma species contains a fourth, C-terminal rhodanese-like domain in addition to the three domains (40). It seems that the two common domains, NFLD and THUMP, confer site specificity to tRNA-modifying enzymes. In fact, TrmN/Trm14, CDAT8, ThiI and aTrm11 were shown to recognize the tRNA acceptor stem required for catalysis (27,34,36,37,41). Furthermore, it has been shown that a shortened or blunt tRNA ACCA end is deleterious to the activity of ThiI (42) and that the THUMP domain recognizes the 3′-ACCA end of tRNA (43), suggesting that the combination of NFLD and THUMP domains is a key structural module to specify the modification site around the tRNA acceptor stem.

In order to understand the molecular mechanism underlying site specificity of aTrm11, the structural information of aTrm11 should be available. Here, we present the first X-ray crystal structures of aTrm11 from Thermococcous kodakarensis (Tko), as well as its SAM complex. The TkoTrm11 is composed of NFLD and THUMP domains fused to an RFM domain, which is bound to a SAM molecule in its pocket. Our structure-guided mutagenesis identified the SAM binding mode and the putative residues responsible for tRNA-binding. Structural comparison shows that there is a striking similarity between the three domains (NFLD, THUMP and RFM) of TkoTrm11 and Trm14 with exception to the conformational location of the RFM domain. Our docking model of a TkoTrm11–tRNA complex, combined with biochemical analyses supports previous evidence that the THUMP domain recognizes the 3′-ACCA end that serves as a reference point to measure the distance to the modification site. These findings expand our understanding of the molecular ruler mechanism for site specificity of archaeal Trm11 and Trm14.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

[Methyl-14C]-SAM (1.95 GBq/mmol) and [methyl-3H]-SAM (2.47 TBq/mmol) were purchased from PerkinElmer. Non-radioisotope-labeled SAM was obtained from Sigma. DNA oligomers and 2′-O methylated primers were obtained from Invitrogen and Hokkaido System Science, respectively. T7 RNA polymerase was purchased from Toyobo. All other chemical reagents were of analytical grade.

Protein preparation and crystallization

Tko cells were prepared following a previously described standard culture protocol (44). The Tko genomic DNA was extracted from the cells with a phenol-chloroform mixture. TkoTrm11 was assigned as TK0981, N2, N2-dimethylguanosine tRNA methyltransferase, in the Tko genome project (45). The TK0981 gene was subcloned into a pMD20-T vector using the Mighty TA cloning kit (Takara) and then sequenced. The resulting vector was used as a template to amplify regions of the TK0981 gene by PCR, using the primers listed in Supplementary Table S1. Following NcoI and BamHI digestion, the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) product was ligated into a pET-30a vector (Novagen), which contains the coding sequence for a human rhinovirus 3C (HRV-3C)-cleavable C-terminal His6 tag. The expression vector was used to overexpress the recombinant TkoTrm11 in Escherichia coli Rosetta 2(DE3) strain (Novagen) cells. E. coli cells harboring the vector were grown at 37°C in LB medium supplemented with 50 μg/ml of kanamycin. When the cell density reached OD600 = ∼0.8, isopropylthio-β-galactoside (IPTG) was added to a final concentration of 0.5 mM and cells were grown for an additional 48 h at 20°C. Cells were then harvested by centrifugation at 4320 xg at 20°C for 20 min. A total of 7 g of the cells were suspended in 35 ml of buffer A (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 200 mM NaCl and 20 mM imidazole) supplemented with Halt protease inhibitor single-use cocktail (Thermo Scientific) and then disrupted with an ultrasonic disruptor (model VCX-500, Sonics & Materials. Inc, USA). To remove a fraction of E. coli proteins by heat denaturation, lysed cells were incubated at 70°C for 45 min and pelleted by centrifugation at 38 900 xg at 4°C for 20 min. The supernatant was loaded onto a Ni-NTA Superflow column (Qiagen) equilibrated with buffer A and the enzyme was eluted using buffer A containing 500 mM imidazole. The eluted fractions were collected and loaded onto a HiTrap Heparin-Sepharose column (GE Healthcare) pre-equilibrated with buffer B (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.5], 50 mM KCl and 5 mM 2-mercaptoethanol). The bound protein was eluted with a linear gradient of buffer B containing 50 mM–1 M KCl. The eluted fractions were collected and concentrated to ∼3 ml volume using Vivaspin 15R centrifugal filter units (Sartorius Stedim Biotech). The concentrated protein was applied to a HiLoad 16/60 Superdex 75 pg column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated with buffer C (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 200 mM KCl and 6 mM 2-mercaptoethanol). The fractions corresponding to the single peak eluting between 45–58 ml were collected (Supplementary Figure S1A). For X-ray crystal structure phasing of a selenomethionine substituted (SeMet) crystal of TkoTrm11 using the single-wavelength anomalous dispersion (SAD) technique, we found that an additional SeMet was required (data not shown). Therefore, Ile291 was replaced with methionine using the QuickChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). The mutation was verified by DNA sequencing. The SeMet I291M mutant was expressed by suppression of the biosynthesis pathway for methionine (46) and purified in the same manner as the wild-type (WT) protein. Likewise, we prepared alanine-substituted mutants (I163A, D185A, F187A, D208A, I209A, R210A, D235A and D254A) for the mutagenesis experiment on the SAM-binding site, alanine-substituted mutants (R105A, K106A, R105A/K106A, K122A, R128A, R140A, K122A/R140A, K122A/R128A/R140A, K151A, R152A, K151A/R152A, R266A, K267A, R268A, R266A/K267A/R268A, R317A, K320A and R317A/K320A) for the mutagenesis experiment on the tRNA recognition site, and alanine-substituted mutants (F86A, K87A, V88A, F86A/K87A/V88A, V118A, L120A and V118A/L120A) for the mutagenesis study on the 3′-ACCA end of the tRNA recognition site. Respective protein purities were confirmed by SDS-PAGE with Coomassie staining (Supplementary Figures S1B, S6A, S6C, S6D and S6E).

Respective gel filtration fractions corresponding to the single peak were pooled and concentrated to ∼3 mg/ml using Vivaspin 15R centrifugal filter units. During the concentration of TkoTrm11, buffer C was substituted with the crystallization buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH. 8.0] and 100 mM NaCl). Initial crystallization trials were set up in VDX48 plates with sealant (Hampton Research) using the hanging-drop vapor diffusion method and commercial crystallization screens from Hampton Research (Index, Salt RX and Crystal screen). The drop solution was equilibrated against 200 μl of reservoir solution at 20°C. A few single crystals of TkoTrm11 appeared after ∼6 months with Index screen reagent #12 (i.e. 0.1 M Tris-HCl [pH 8.5] and 3.0 M NaCl). To decrease the growth time of the crystals, we optimized the initial crystallization condition and the concentration of TkoTrm11. Full-sized rectangular-shaped (300 × 200 × 200 μm) crystals grew within 2 days when we mixed 2μl of TkoTrm11 at 10 mg/ml with an equal volume of crystallization solution composed of 0.1 M Tris-HCl (pH 8.5) and 4.5 M NaCl, and grew crystals at 20°C. SeMet crystals grew under the same conditions. Crystals of TkoTrm11 in complex with SAM were obtained by soaking the crystal of TkoTrm11 in crystallization mother liquor supplemented with 1 mM SAM at 20°C for 3 h. Cryoprotection was achieved by stepwise transfer to the respective artificial mother liquor containing 15% glycerol. The crystals were then flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen.

Structure determination

X-ray diffraction data sets from apo-TkoTrm11 (λ = 1.0000) and TkoTrm11-SAM (λ = 1.0000) were recorded at the BL38B1 beamline at SPring-8 (Hyogo, Japan). The SAD data set from SeMet-I291M (λ = 0.9791) was also collected at the same beamline at SPring-8. Data collection statistics are in Table 1. All data sets were processed, merged and scaled using the HKL2000 program (47). Using the deduced Se-SAD data set, all 6 Se positions were identified and refined in the orthorhombic space group P212121, and the initial phase was calculated using AutoSol in PHENIX (48), and followed by automated model building using RESOLVE (49). The resulting map and partial model were used for manually building the model using COOT (50). The model was further refined using PHENIX (48). Using the refined coordinates of SeMet-I291M as a search model, molecular replacement phasing of the apo-TkoTrm11 and TkoTrm11-SAM crystal structure was achieved using the Phaser program (51). The model was further built manually with COOT (50) and refined with PHENIX (48). The structures of apo-TkoTrm11 and TkoTrm11-SAM were refined to Rwork/Rfree of 20.5%/24.0% at 1.70 Å resolution and 18.7%/22.3% at 1.74 Å resolution, respectively (Table 1). The crystals belonged to space group P212121, where one apo-TkoTrm11 molecule is present per asymmetric unit. The final model of apo-TkoTrm11 contained 323 residues (1–257 and 266–331) and 179 water molecules, and the TkoTrm11-SAM contained 323 residues (1–257 and 266–331) and 282 water molecules and one SAM molecule. Both final models were further checked using PROCHECK (52), showing the quality of the refined model. Ramachandran plots (%) of the two structures are tabulated in Table 1. The structure factors and coordinates of apo-TkoTrm11 and TkoTrm11-SAM have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB code 5E71 and 5E72).

Table 1. Data collection and refinement statistics.

| apo-TkoTrm11 | TkoTrm11–SAM | SeMet I291M | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data collection | |||

| Wavelength (Å) | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 0.9791 |

| Space group | P212121 | P212121 | P212121 |

| Cell dimensions | |||

| a, b, c (Å) | 47.73, 53.52, 134.86 | 47.60, 53.79, 134,75 | 47.65, 53.81, 134,84 |

| α, β, γ (°) | 90, 90, 90 | 90, 90, 90 | 90, 90, 90 |

| Resolution (Å) | 50–1.70 (1.73–1.70) | 50–1.74 (1.80–1.74) | 50–1.75 (1.76–1.70) |

| Rmergea | 5.1 (59.4) | 4.3 (21.7) | 10.1 (33.8) |

| I / σI | 53.7 (4.2) | 41.6 (6.7) | 106.7 (15.5) |

| Completeness (%) | 99.8 (100.0) | 99.7 (99.3) | 100.0 (100.0) |

| Redundancy | 7.1 (7.2) | 5.1 (5.1) | 29.0 (28.0) |

| Refinement | |||

| Resolution (Å) | 34.4-1.70 | 32.6-1.74 | |

| No. reflections | 34,442 | 35,857 | |

| Rworkb/ Rfreec | 20.5/ 24.0 | 18.7/22.3 | |

| No. atoms | 2,774 | 2,909 | |

| Protein | 2,599 | 2,599 | |

| Water | 179 | 282 | |

| SAM | 0 | 1 | |

| Avg. B-factors (Å2) | 25.9 | 18.8 | |

| R.m.s. deviations | |||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.006 | 0.007 | |

| Bond angles (°) | 1.0 | 1.1 | |

| Ramachandran plot (%) | |||

| Most favored | 92.8 | 92.0 | |

| Additionally allowed | 6.9 | 7.6 | |

| Generously allowed | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| Disallowed | 0.4 | 0.4 | |

The value in the parentheses is for the highest resolution shell.

aRmerge = ΣΣj|<I(h)> – I(h)j|/ΣΣj|<I(h)>|, where <I(h)> is the mean intensity of symmetry-equivalent reflections.

bRwork = Σ (IIFp(obs) – Fp(calc)II)/ΣIFp(obs)I.

cRfree = R factor for a selected subset (5%) of reflections that was not included in earlier refinement calculations.

Preparation of Tko tRNATrp transcript and its mutants (G10A, ΔA, ΔCA, ΔCCA and ΔACCA)

Tko tRNATrp transcript (Supplementary Figure S2A) was prepared by T7 RNA polymerase in vitro transcription using our previously reported method (53) from a DNA template produced from PCR amplification using our designed two primers (F and R denote the upstream and the downstream primers, respectively, and DNA sequences in bold show a promoter that is recognized by T7 RNA polymerase): Tk-TrpF, 5′-GGGTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGGGCGTGGTGTAGCCTGGTCCATCATCGCGCGGGCTCCAGACCCGCGG-3′; Tk-TrpR, 5′-TGGTGGGGGCGCGGGGATT TGAACCCCGGTCCGCGGGTCTGGAGCCCG-3′. The G10A mutant, which replaces guanine at 10 position of Tko tRNATrp transcript with adenine, was prepared as described above by using the following two primers (A10 is underlined): Tk-TrpF, 5′-GGGTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGGGCGTGATGTAGCCTGGTCCATCATCGCGCGGGCTCCAGACCCGCGG-3′; G10A-R, 5′-TGGTGGGGGCGCGGGGATTTGAACCCCGGTCCGCGGGTCTGGAGCCCG-3′. The three truncated mutants of the 3′-CCA end of Tko tRNATrp were prepared using the following primers (In all three reverse-primers, the first underlined nucleotide was methylated on its 2′-O ribose): Tk-TrpF, 5′-GGGTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGGGCGTGGTGTAGCCTGGTCCATCATCGCGCGGGCTCCAGACCCGCGG-3′; ΔA-R, 5′-GGTGGGGGCGCGGGGATTTGAACCCCGGTCCGCGGGTCTGGAGCCCG-3′; ΔCA-R, 5′-GTGGGGG CGCGGGGATTTGAACCCCGGTCCGCGGGTCTGGAGCCCG-3′; ΔCCA-R, 5′-TG GGGGCGCGGGGATTTGAACCCCGGTCCGCGGGTCTGGAGCCCG-3′; ΔACCA-R, 5′-GGGGGCGCGGGGATTTGAACCCCGGTCCGCGGGTCTGGAGCCCG-3′. All transcripts were purified through anion exchange chromatography using a HiTrap Q-sepharose column (GE healthcare). Mutant (ΔA, ΔCA, ΔCCA and ΔACCA) RNA transcripts were further PAGE-purified using a 15% PAGE (7M Urea) gel (Supplementary Figures S8A and S8B).

Measurement of TkoTrm11 activity

The enzymatic assay was measured by incorporation of 14C-methyl groups from [methyl-14C]-SAM onto the Tko tRNATrp transcript (Supplementary Figure S2A); 0.1 μM enzyme, 10 μM transcript and 11 μM [methyl-14C]-SAM in 35 μl of buffer A (50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 5 mM MgCl2, 6 mM 2-mercaptoethanol and 50 mM KCl) were incubated for various times (0, 0.5, 2, 8, 16, 32 and 64 min) at 50°C. An aliquot (30 μl) was then used for the filter assay (Supplementary Figure S2B).

In order to discriminate the m2G and m22G formation activities of TkoTrm11, we employed two-dimensional TLC (54). The 14C-methylated RNA was dissolved in 5 μl of 50 mM ammonium acetate (pH 5.0) and digested with 2.5 units of nuclease P1, and then 2 μl of standard nucleotides containing 0.05 A260 units each of pA, pG, pC and pU was added. A total of 2 μl of the sample was spotted onto a thin layer plate (Merck code number 1.05565, cellulose F) and separated using the following two solvent systems: Supplementary Figures S2C, S2D and S6B, first dimension, isobutyric acid/concentrated ammonia/water, 66:1:33, v/v; second dimension, isopropyl alcohol/HCl/water, 70:15:15, v/v; Supplementary Figure S2D, first dimension, isobutyric acid/concentrated ammonia/water, 66:1:33, v/v/v; second dimension, 0.1 M Sodium phosphate (pH 6.8), ammonium sulfate, n-propanol, 100:60:2, v/w/v. Incorporation of 14C-methyl groups was monitored with a Fuji Photo Film BAS2000 imaging analyzer. Standard nucleotides were marked by UV 260 nm irradiation.

To visualize the methylation activity, we used 10% PAGE (7 M urea) and an imaging analyzer system. In brief, tRNA (0.1 A260 units) was incubated with 0.1 μM TkoTrm11 and 11 μM [methyl-14C]-SAM for 10 min at 50°C in 35 μl of buffer A and then loaded onto a 10% polyacrylamide gel (7 M urea). The gel was stained with methylene blue and dried. The incorporation of 14C-methyl groups into tRNA was monitored with an imaging analyzer as described above.

Measurements of kinetic parameters for SAM

We initially performed time course experiments at 50°C with 0.1 μM TkoTrm11, 11 μM Tko tRNATrp transcript and 11 μM [methyl-14C]-SAM in 200 μl of buffer A. The aliquots (30 μl each) were taken at appropriate times (0, 2, 5, 7.5, 10 and 15 min) and formations of 14C-pm2G and 14C-pm22G were monitored by two-dimensional TLC. Under these conditions, most of the pm2G was observed at 10 min, and m22G formation was undetectable by autoradiography (Supplementary Figure S6B). Kinetic parameters for SAM were determined by incorporation of 3H-methyl groups from [methyl-3H]-SAM into tRNA. The following conditions were used for the kinetics: 0.1 μM TkoTrm11, 11 μM tRNATrp transcript and various concentrations (0.8, 1.5, 3.0, 6.0, 12.0, 24.0, 36.0, 48.0, 60.0 and 72.0 μM) of [methyl-3H]-SAM were incubated at 50°C for 10 min, and then the filter assay was performed.

Gel mobility shift assay

A gel mobility shift assay was carried out according to our previous reports (55). A total of 6.7 μM Tko tRNATrp transcript and various concentrations (0, 0.84, 1.68, 3.35 and 6.70 μM) of WT TkoTrm11 or mutant were incubated in the buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 5 mM MgCl2, 6 mM β-mercaptoethonol and 50 mM KCl) at 60°C for 30 min. A 4x loading solution (0.25% bromphenol blue and 30% glycerol) was added to the each sample, and the mixtures were applied to a 6% polyacrylamide gel. After electrophoresis in running buffer (25 mM Tris-acetic acid (pH 7.0) and 5 mM Mg(OAc)2) at 30 mA for 1 h, the gel was stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue to detect protein and then with methylene blue to detect RNA.

Computer programs for figures

Structural figures were generated using PyMOL (DeLano Scientific, Palo Alto, CA, USA) and CueMol (http://www.cuemol.org). The electrostatic potential surface models were calculated using APBS (56). The schematic diagram of SAM interactions with the amino acid residues of TkoTrm11 was generated using LIGPLOT (57). The amino acid sequence alignment was generated using ClustalW 1.83 (58) and ESPript (59) programs.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Crystal structure determination

The TkoTrm11 was cloned and overexpressed in E. coli, and the recombinant was purified using three chromatographic steps. The molecular weight of TkoTrm11 is 39 255 Da, including the C-terminal His-tag and the protease cleavage site (332LEVLFQGPSHHHHHH346) (Supplementary Figure S1B). Seven grams of E. coli cells yielded ∼2 mg of purified TkoTrm11. HRV-3C protease could cleave the C-terminal His-tag only partially, possibly because of steric hindrance between TkoTrm11 and the HRV-3C protease. We confirmed that the purified TkoTrm11 retained methylation activity (Supplementary Figure S2B). The first crystals of TkoTrm11 appeared ∼6 months after we set up the initial crystallization screening. Upon optimization of the crystallization solution, crystals grew within 2 days. Crystals of apo-TkoTrm11 and of TkoTrm11 in complex with SAM diffracted to ∼1.7 Å resolution and belonged to the orthorhombic space group P212121. For phasing using the Se-SAD method, we prepared Se-methionine labeled crystals. The initial electron density map allowed us to model one molecule of TkoTrm11 in the asymmetric unit, consistent with the biological unit (i.e. hydrodynamic radius size estimate) observed with size exclusion chromatography (Supplementary Figure S1A). The structures of apo-TkoTrm11 and TkoTrm11–SAM were refined with reliable R and Rfree factor values that validate the model (Table 1).

Overall structure

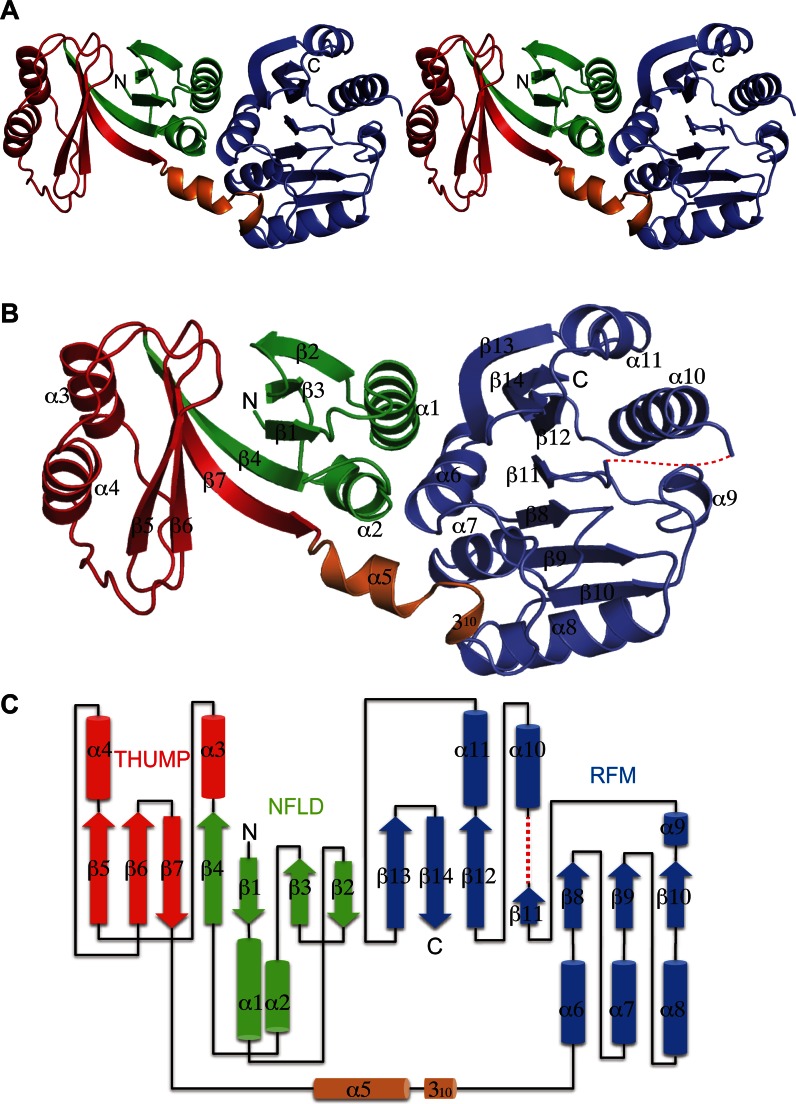

The overall shape of TkoTrm11 is like a cylinder with approximate 60 × 30 × 30 Å3 dimensions (Figure 1A). The structure of TkoTrm11 is comprised of three domains: NFLD (green), THUMP (red) and RFM (slate blue). The THUMP domain is connected to the C-terminal RFM domain via a rigid linker region (orange) consisting of two secondary structures, an α-helix joined to a more C-terminal 310-helix (Figure 1B and C). NFLD has been regarded as a minimal core of the THUMP domain (38). The entirety of NFLD and THUMP domains employs a globular α/β structure consisting of seven β strands and four α helices. The four β strands (β1–β4) of NFLD form one antiparallel β sheet together with two α helices (α1 and α2). In contrast to the structural arrangement of NFLD, the three β strands (β5–β7) of THUMP domain form one mixed antiparallel and parallel β sheet together with two α helices (α3 and α4). The two β sheets are connected by two long kinked β strands (β4 and β7). Therefore, seven β strands (β1–β7) seem to form one twisted β sheet in the center of two domains, and the β sheet is packed by two α helices. On the other hands, the C-terminal RFM domain of TkoTrm11 is a class I type of MTase that consists of seven β strands (β8–β14) and six α helices (α6–α11) (11). The parallel β sheet, forming by seven β strands (β8–β14), is sandwiched by the three α helices out of six α helices (α6–α11), indicating that the architecture of the RFM domain in TkoTrm11 is a classical feature that belongs to the RFM superfamily and present in other MTases. The entire region comprising the NFLD and THUMP domains is reported to function as the tRNA-binding module in other tRNA modifying-enzymes (33). Our structure-based sequence alignment analysis suggests that the structural arrangement of TkoTrm11 is conserved in aTrm11 from the Pyrococcus genus, which are species related to Tko (Supplementary Figure S3). Thus, TkoTrm11 probably possess the ability to specifically recognize the tRNA substrate, similar to the substrate recognition mechanism of aTrm11 from Pyrococcus species as previously reported (34,36).

Figure 1.

Crystal structure of aTrm11 from Thermococcus kodakarensis. (A) Ribbon stereo diagram of the overall structure. The three domains, NFLD (1–65 residues), THUMP domain (66–144 residues) and RFM domain (157–257 and 266–331 residues) are colored green, red, slate blue, respectively. A rigid linker region of the α- and 310 helices (145–156 residues) is colored orange. The N and C-terminal ends are labeled as N and C, respectively. (B) Ribbon diagram of the overall structure. The secondary structures of the α helix, 310 helix and β strand are labeled (in order) as the α 310 and β, respectively. The dotted line (red color) indicates a disordered region (258–265 residues) (C) A TkoTrm11 secondary structure topology diagram. The α helices and β strands are represented by cylinders and thick arrows, respectively. The dotted line (red color) indicates a disordered region (258–265 residues).

Structural comparison

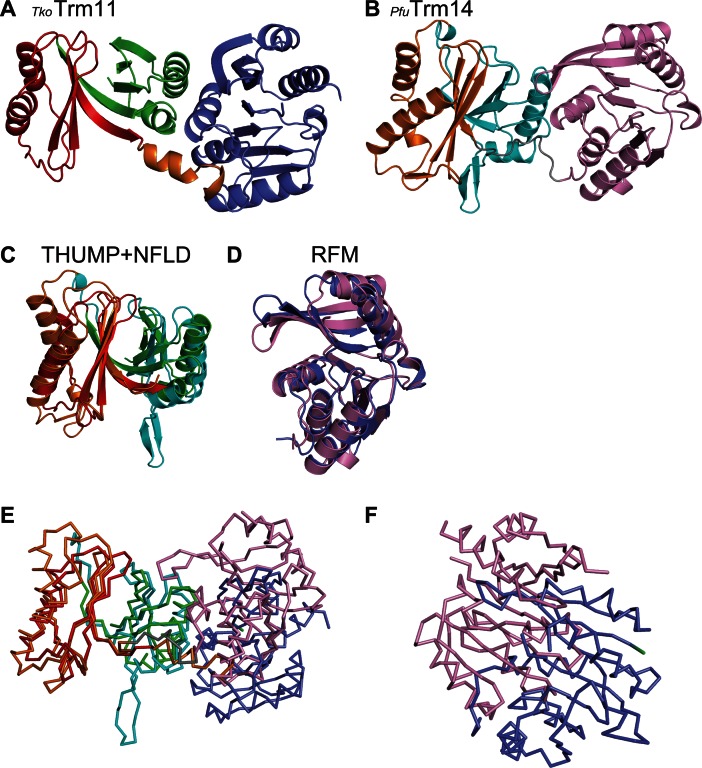

Our structural analysis provided a detailed configuration of TkoTrm11. To estimate the functional features of TkoTrm11 from its structural conservation, we searched for homologous structures using the DALI server (60). The most similar structure identified (i.e. the structure with the highest Z-score), was archaeal Trm14 from Pyrococcus furiosus (Pfu) (Figure 2A and B), which catalyzes the formation of m2G6 in archaeal tRNA species (27). Furthermore, the structure of NFLD and THUMP domain in TkoTrm11 is homologous to that of the NFLD and THUMP domain in other two tRNA-modifying enzymes ThiI (38) and CDAT8 (37). Their domains are shown to be responsible for tRNA recognition. The TkoTrm11 and PfuTrm14 conformations of respective NFLD-THUMP and RFM domains superimposed well (Figure 2C and D), with root mean square deviations (r.m.s.d) of 2.7 Å and 3.0 Å that were estimated using their 136 and 205 Cα atoms. This high level of structural conservation between these regions suggests that TkoTrm11 and PfuTrm14 (Supplementary Figure S4) are derived from a common ancestor. Importantly, however, the linker regions connecting the NFLD and RFM domains are not conserved between TkoTrm11 and PfuTrm14. The TkoTrm11 α- and 310 helices linker is rather a flexible loop in PfuTrm14. Furthermore, the conformational location of the RFM domain is remarkably different between TkoTrm11 and PfuTrm14 (Figure 2E and F) when their NFLD-THUMP domain is superimposed. The RFM domain of pfuTrm14 is largely rotated and shifted more upward and closer to the NFLD-THUMP domain than it is in the TkoTrm11 structure. The movement of the RFM domain in TkoTrm11 seems to be restricted because of the rigidness (i.e. like a tension-rod) of the linker region formed by the α- and 310 helices. However, the RFM domain of PfuTrm14 can be more flexible than that of TkoTrm11 because the linker region consists of loop structure. Thus, we infer that the structural difference of linker regions between TkoTrm11 and PfuTrm14 attributes to the difference in spatial location of the RFM domain. Because the RFM domain includes a catalytic center, the distinct linker-regions might have an effect on the site specificity of the two enzymes.

Figure 2.

Structural comparison of TkoTrm11 and PfuTrm14 (PDB ID = 3TLJ). (A) Ribbon diagram of the overall structure of TkoTrm11. The three domains, NFLD, THUMP and RFM, and the rigid linker region are colored as in Figure 1A. (B) Ribbon diagram of the overall structure of PfuTrm14. The three domains, NFLD, THUMP and RFM, and a loop linker are colored cyan, orange, pink and grey, respectively. (C) Superimposition (obtaining by aligning respective Cα atoms) of the THUMP (red) and NFLD (green) domains of the TkoTrm11 structure onto that of the THUMP (orange) and NFLD (cyan) domains of the PfuTrm14 structure. (D) Superimposition (obtaining by aligning respective Cα atoms) of the TkoTrm11 RFM (slate blue) domain onto that of the PfuTrm14 RFM (pink) domain. (E) Line diagram of the overall structure based on the superimposed Cα atoms of THUMP and NFLD domains between the TkoTrm11 and PfuTrm14 structures. (F) Close-up view of the structural deviation of RFM domains (TkoTrm11, slate blue and PfuTrm14, pink) based on the superimposed Cα atoms of THUMP and NFLD domains between the TkoTrm11 and PfuTrm14 structures.

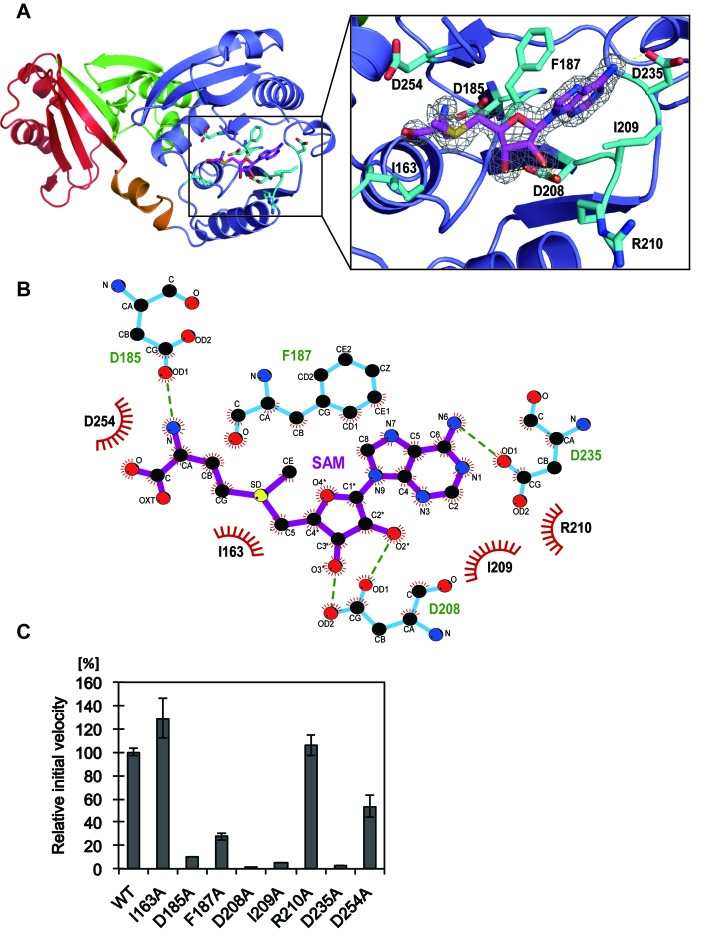

The SAM-binding mode

To examine how the SAM binds to the catalytic domain of RFM in TkoTrm11, we determined the X-ray crystal structure of the TkoTrm11–SAM complex at 1.74 Å resolution. One SAM molecule was bound to the pocket of the RFM domain (Figure 3A). The SAM-binding pocket is composed of several residues, which are conserved in archaeal Trm11 enzymes (Supplementary Figures S5A and S5B). The eight residues (I163, D185, F187, D208, I209, R210, D235 and D254) that interact with the SAM molecule are illustrated in Figure 3B. These residues belong to the conserved motifs I, II, III and IV that exist in SAM dependent MTases (Supplementary Figure S3) (25,61,62). The three aspartate residues at amino acid numbers 185, 208 and 235, are included in conserved motifs I, II and III, respectively, and form four hydrogen bonds with the SAM molecule. As it has been predicted by bioinformatics studies of PabTrm11 (28), the three aspartates indeed coordinate the methionine moiety, the 2′- and 3′- hydroxyl groups of the ribose moiety, and the N6 atom of the adenine moiety, respectively. On the other hands, the adenine moiety of the SAM molecule is specifically recognized by two hydrophobic residues (F187 and I209), resulting in the formation of stacking interactions between the two residues and the adenine moiety. Other TkoTrm11 residues contribute several van der Waals contacts with the SAM molecule. The bound SAM molecule is structurally extended, and its conformation is very similar to that of the SAM molecule in complex with PfuTrm14 (27).

Figure 3.

The SAM-binding site of TkoTrm11 in complex with SAM. (A) Close-up view of the SAM molecule and its binding residues illustrated as stick models (magenta and cyan, respectively). Electron density map around the SAM molecule contoured at 2.0 σ. (B) Ligplot diagram (64) of interactions between TkoTrm11 amino acid residues and the bound SAM molecule. (C) Methyl transfer activity of the alanine-substituted mutant proteins. The mutant name indicates the site of alanine substitution. The initial velocity of wild-type (WT) TkoTrm11 is expressed as 100%. Error-bar indicates the SD (standard deviation) that was calculated between three independent experiments.

To determine whether the side chain of these residues plays an important role in the binding of the SAM molecule to TkoTrm11, we performed an alanine-scanning mutagenesis study. The initial velocities of six mutants (D185A, D208A, I209A, R210A, D235A and D254A: Supplementary Figure S6A) showed a decrease compared to that of the WT enzyme. Specifically, the initial velocities of D185A, F187A, D208A, I209A and D235 were less than 20% of that of WT, suggesting that the formations of hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic interactions between those residues and the SAM molecule are required for the binding of SAM into the pocket of the RFM domain. A kinetic study further confirmed the enzymatic significance of these SAM-binding residues (Table 2). In this study, we optimized the reaction time and conditions for the measurement of the first TkoTrm11 methyl transferase reaction (m2G formation) at the position G10 of Tko tRNATrp (see Materials and Methods). The mono-methylation was confirmed by TLC (Supplementary Figure S6B). The four mutants, F187A, I209A, D235A and D254A, had respective apparent Km values of 23, 23, 45 and 26 μM, which are 3.2–6.4 times higher than that of the WT enzyme, and the apparent Km value of D208A was more than 1200 μM. These results indicate the large effect that these residues contribute to the binding affinity of TkoTrm11 for the SAM molecule, and thereby leading to the decrease of Vmax values in the mutants. Because the Vmax/Km values of D208A and D235A mutant are less than 0.00039 and 0.02, respectively, each of their three hydrogen bonds with SAM (D208 Oδ1—ribose 2′O, D208 Oδ2—ribose 3′O and D235 Oδ1—SAM N6) seems to be the most important for SAM-recognition compared to other interactions, which are the hydrophobic interactions between two residues (F187 and I209) and the adenine moiety of SAM molecule, and the van der Waals contacts formed by the D254 and  and α-COO− group of SAM molecule. Although the Vmax value of D185A was decreased to 230 nmol mg−1 h−1, which is 3.2 times lower than that of the WT enzyme, the Km value was almost the same as that of the WT enzyme. The decrease is probably due to the disruption of the D185 Oδ1—SAM

and α-COO− group of SAM molecule. Although the Vmax value of D185A was decreased to 230 nmol mg−1 h−1, which is 3.2 times lower than that of the WT enzyme, the Km value was almost the same as that of the WT enzyme. The decrease is probably due to the disruption of the D185 Oδ1—SAM  hydrogen bond. The formed hydrogen bond determines the spatial location of the

hydrogen bond. The formed hydrogen bond determines the spatial location of the  and α-COO− groups of the SAM molecule, resulting in the stabilization of the entire SAM molecule. The amino-carboxyl group of SAM molecule is often shown to be a disordered region in other tRNA MTases because no residues are observed directly interacting with a SAM molecule. Therefore, TkoTrm11 D185 might contribute to the transfer speed of the SAM methyl group to N2-guanine and/or the release speed of product S-adenosyl-L-homocystein from the pocket of the TkoTrm11 RFM domain. Other region (TkoTrm11 residues 258–265), which is closely located near the SAM-binding pocket, was unable to be modeled in our structure due to missing electron density. This region is a C-terminal conserved catalytic motif IV (254DPPY257) (Supplementary Figure S3), which is involved in the catalytic reaction and recognition of a guanine moiety (28). The residues in motif IV are also found in pfuTrm14 (293NLPY296) and in Thermus thermophilus RsmC (305NPPF308), which is a SAM dependent 16S rRNA (m2G1207) methyltransferase (63). In the crystal structure of RsmC in complex with SAM and guanosine molecules, the aromatic ring of F308 forms a stacking interaction with a substrate guanine moiety that is flipped out from the rRNA. Among the three enzymes, their SAM-binding mode and motif IV are structurally conserved. Therefore, it is likely that Y257 of TkoTrm11 as well as Y296 of pfuTrm14 provide almost the same hydrophobic interaction for the substrate base as does F308 of T. thermophilus RsmC. However, the underlying mechanism by which the TkoTrm11 produces not only a N2-methylguanosine (m2G) but also a N2, N2-dimethylguanosine (m22G) remains a puzzling question despite of the structural conservation of catalytic center of three enzymes. An observation of structural intermediate methylated by TkoTrm11 could be needed to answer the question, although U25 and a V-loop of four nucleotides of yeast tRNAPhe might be major determinants for the formation of m22G as previously reported (36).

and α-COO− groups of the SAM molecule, resulting in the stabilization of the entire SAM molecule. The amino-carboxyl group of SAM molecule is often shown to be a disordered region in other tRNA MTases because no residues are observed directly interacting with a SAM molecule. Therefore, TkoTrm11 D185 might contribute to the transfer speed of the SAM methyl group to N2-guanine and/or the release speed of product S-adenosyl-L-homocystein from the pocket of the TkoTrm11 RFM domain. Other region (TkoTrm11 residues 258–265), which is closely located near the SAM-binding pocket, was unable to be modeled in our structure due to missing electron density. This region is a C-terminal conserved catalytic motif IV (254DPPY257) (Supplementary Figure S3), which is involved in the catalytic reaction and recognition of a guanine moiety (28). The residues in motif IV are also found in pfuTrm14 (293NLPY296) and in Thermus thermophilus RsmC (305NPPF308), which is a SAM dependent 16S rRNA (m2G1207) methyltransferase (63). In the crystal structure of RsmC in complex with SAM and guanosine molecules, the aromatic ring of F308 forms a stacking interaction with a substrate guanine moiety that is flipped out from the rRNA. Among the three enzymes, their SAM-binding mode and motif IV are structurally conserved. Therefore, it is likely that Y257 of TkoTrm11 as well as Y296 of pfuTrm14 provide almost the same hydrophobic interaction for the substrate base as does F308 of T. thermophilus RsmC. However, the underlying mechanism by which the TkoTrm11 produces not only a N2-methylguanosine (m2G) but also a N2, N2-dimethylguanosine (m22G) remains a puzzling question despite of the structural conservation of catalytic center of three enzymes. An observation of structural intermediate methylated by TkoTrm11 could be needed to answer the question, although U25 and a V-loop of four nucleotides of yeast tRNAPhe might be major determinants for the formation of m22G as previously reported (36).

Table 2. Kinetic parameters for SAM.

| Sample names | KmμM | Vmaxnmol mg−1 h−1 | kcatmin−1 | Relative Vmax/Km |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | 7 ± 1 | 746 ± 46 | 0.49 ± 0.08 | 1.00 |

| D185A | 6 ± 1 | 230 ± 18 | 0.15 ± 0.03 | 0.34 |

| F187A | 23 ± 1 | 319 ± 21 | 0.21 ± 0.02 | 0.13 |

| D208A | >1200 | 10 – 50 | 0.007 – 0.03 | <0.00039 |

| I209A | 23 ± 1 | 309 ± 31 | 0.20 ± 0.04 | 0.12 |

| D235A | 45 ± 3 | 111 ± 11 | 0.07 ± 0.03 | 0.02 |

| D254A | 26 ±3 | 154 ± 9 | 0.10 ± 0.02 | 0.05 |

The Km/Vmax value is expressed relative to that of the wild type enzyme, which is set to 1.00.

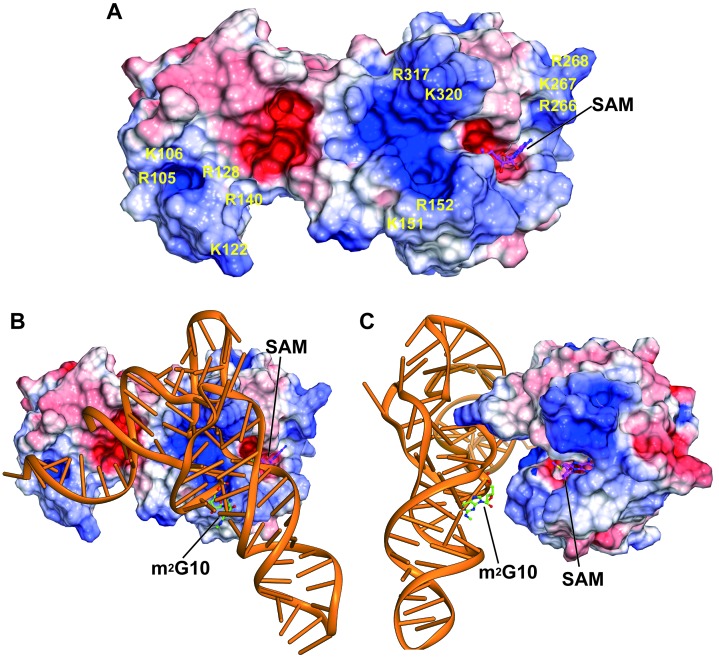

Recognition of tRNA by TkoTrm11

We calculated an electrostatic potential map of the TkoTrm11–SAM complex structure (Figure 4A) in order to examine specific residues responsible for the recognition of substrate tRNA. As a result, many positively charged residues are observed on the surface areas of TkoTrm11 located on the THUMP domain, linker region and RFM domains, suggesting that the positively charged residues are probably involved in the recognition of tRNA. Extensive biochemical studies have reported that the structural elements of acceptor stem, T-arm and V-loop in the S. cerevisiae tRNAPhe and tRNAAsp species are important for the substrate specificity and formation of m22G by the pabTrm11 (34,36). Based on the previous results for the substrate recognition and our above finding of the positive surface areas of TkoTrm11, the docking model of TkoTrm11 in complex with S. cerevisiae tRNAPhe was manually built (Figure 4B and C). Furthermore, the structure of the bacterial ThiI–RNA complex, which was reported recently (43), greatly contributed to the construction of its docking model. The docking model of the TkoTrm11–tRNAPhe complex shows that four structural components (a 3′-ACCA end, acceptor stem, T-stem and V-loop) interact with the THUMP-RFM domains and linker region of TkoTrm11 along the positive surface areas. In addition, m2G10 is located at the front of the SAM binding pocket, where the recognition and methylation for substrate N2-guanosine can occur by the flipping out of the substrate tRNA G10 guanine moiety coinciding with the conformational changes of TkoTrm11. Thus, these observations suggest that the positively charged residues, which are estimated by the electrostatic potential, may play a significant role as the tRNA-binding sites.

Figure 4.

Search for the tRNA recognition site of TkoTrm11. (A) Surface model of TkoTrm11 colored according to electrostatic potential represented as a gradient from negative (red) to positive (blue). The positions of positively charged residues are labeled on the surface model. The stick model represents the SAM molecule bound to TkoTrm11. (B) Proposed model of the complex formed between TkoTrm11 and yeast tRNAPhe with SAM (magenta) and m2G10 (green) illustrated as stick representations. (C) Figure 4B rotated 90° clockwise around its vertical axis.

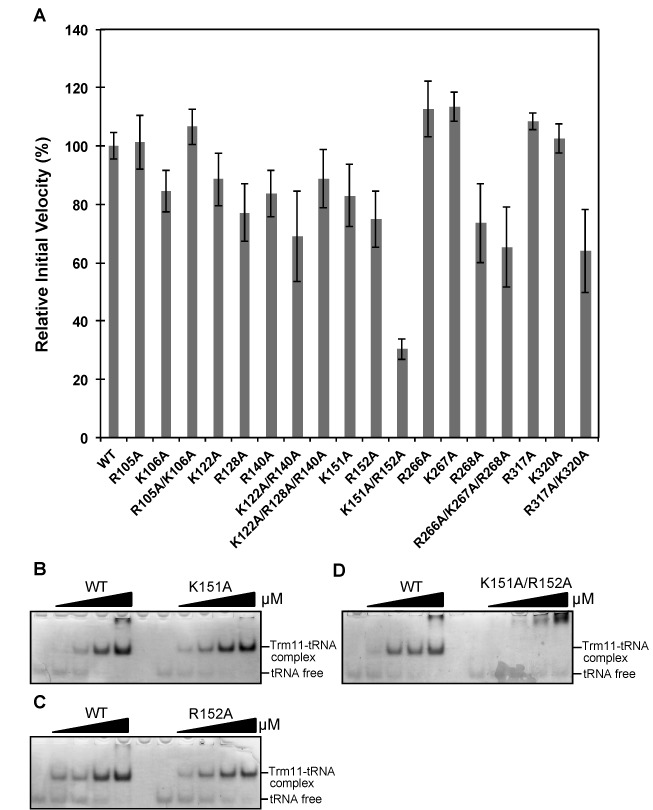

To clarify whether the Arg and Lys residues observed above are responsible for recognition of a substrate tRNA, we conducted a mutagenesis study: The positively charged TkoTrm11 residues were each replaced with an alanine residue (Ala), which we expected to moderately disrupt interactions with the negative charges of tRNA generated by its phosphate backbone. Eighteen mutant proteins (R105A, K106A, R105A/K106A, K122A, R128A, R140A, K122A/R140A, K122A/R128A/R140A, K151A, R152A, K151A/R152A, R266A, K267A, R268A, R266A/K267A/R268A, R317A, K320A and R317A/K320A) were constructed and then purified (Supplementary Figures S6A, S6C and S6D). Figure 5A shows the relative velocities of WT TkoTrm11 and of the 18 mutants. No significant changes in the initial velocities were observed in single mutants, but the double mutant (K151A/R152A) showed a ∼30% reduction in the initial velocity as compared to WT TkoTrm11 (Figure 5A). The K151A and R152A residues are located in the linker region connecting the THUMP and RFM domains, likely interacting with the phosphate backbone around the acceptor stem of tRNA in our docking model of TkoTrm11–tRNA (Figure 4B and C). We hypothesized that the double mutant, K151A/R152A, might have a synergistic effect on the binding affinity for tRNA as compared to the single mutants. We therefore tested its ability to bind tRNA in a gel shift assay (Figure 5B, C and D). As a result, one band that corresponds to the formation of a complex between WT TkoTrm11 and tRNATrp was detected after an increase in the concentration of WT TkoTrm11. The free tRNATrp gradually disappeared with the increasing concentration of WT TkoTrm11. Similar results were obtained for the two single mutants (K151A and R152A). In contrast to these findings about WTTkoTrm11 and the two single mutants, formation of a complex between K151A/R152A and tRNATrp was not observed (Figure 5D) despite having ∼30% relative activity as compared to WT TkoTrm11, and there remained free tRNATrp that was not bound to the double mutant. These results suggest that K151 and R152 residues synergistically contribute to the recognition of a substrate tRNA. Similarly, the R266, K267, R268, R317 and K320 residues can contribute to tRNA-binding because the corresponding double and triple mutants (R266A/K267/R268A and R317A/K320A) showed a decrease in a nearly 50% decrease in initial velocities in comparison with the relevant single mutants (R266A, K267A, R268A, R317A and K320A). The R317 and K320 residues in the RFM domain seem to recognize the V-loop of tRNA (Figure 4B). In the case of three R266, K267 and R268 residues, it is difficult to find an interaction between the three residues and tRNA without a conformational change of the docking model. Taken together, our data suggest that these positively charged residues distributed in the linker region and RFM domain play a significant role as the tRNA-binding sites.

Figure 5.

Putative tRNA-binding sites. (A) Methyl transfer activity of the alanine-substituted mutant proteins. The mutant name indicates the site of alanine substitution. The initial velocity of WT TkoTrm11 is expressed as 100%. Error-bar indicates the standard deviation (SD) that was calculated between three independent experiments. (B) The binding-affinity values of the WT TkoTrm11 and K151A mutant for Tko tRNATrp were analyzed by a gel mobility shift assay. (C) The binding-affinity values of WT TkoTrm11 and R152A mutant for Tko tRNATrp were also analyzed by a gel mobility shift assay. (D) The binding-affinity values of WT TkoTrm11 and R152A mutant for Tko tRNATrp were analyzed by a gel mobility shift assay. The formations of a complex by WT TkoTrm11 or each of the three mutants with Tko tRNATrp and unbound free tRNA were indicated by two black lines labeled on the right side of the gel.

Possible mechanism for site specificity

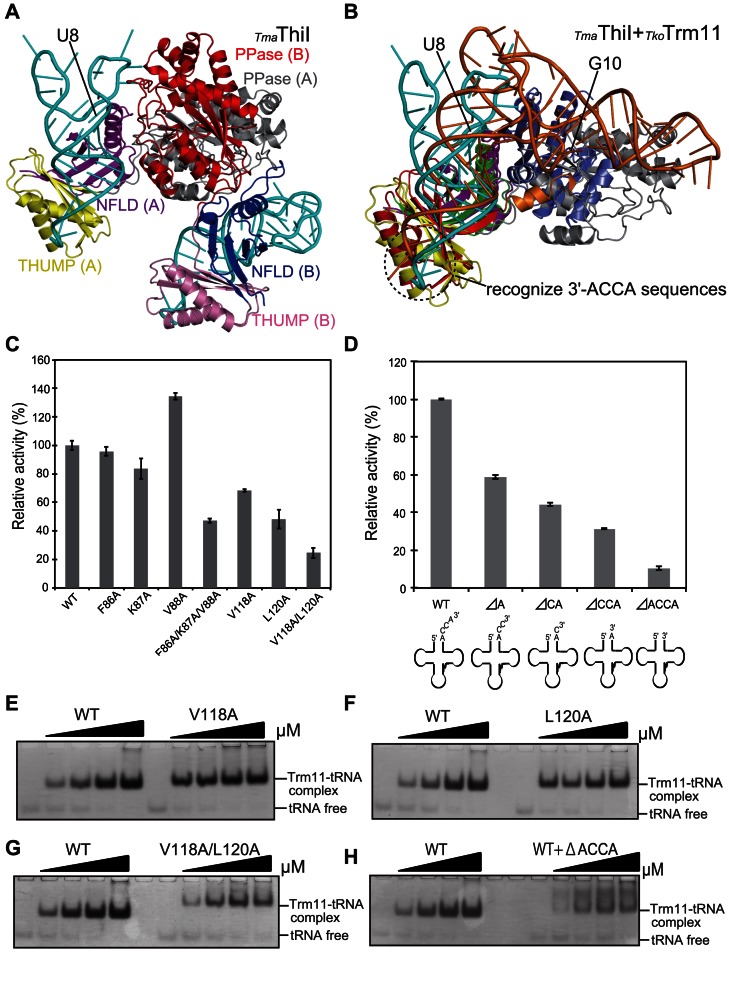

As we described above, there is a striking structural similarity between the NFLD and THUMP domains among tRNA modifying-enzymes, TkoTrm11, PfuTrm14, ThiI and CDAT8. ThiI is a 4-thiouridine synthetase that catalyzes the formation of 4-thiouridine at position 8 (S4U8) in bacterial and archaeal tRNA species. Recently, the X-ray crystal structure of Thermotoga maritime (Tma) ThiI in complex with truncated tRNA has been determined (43) and has revealed that the RNA is mainly bound to the NFLD and THUMP domains of one subunit within the homodimer of ThiI thereby positioning U8 close to the pyrophosphatase domain (PPase) active site in the other subunit (Figure 6A). To examine the difference of RNA-binding mode between the TmaThiI–RNA complex and docking model of TkoTrm11–tRNAPhe complex (Figure 4B and C), we superimposed it onto the TmaThiI–RNA complex by aligning their respective main chain Cα atoms of their NFLD and THUMP domains (Figure 6B). These two domains superimpose well between both enzymes with a r.m.s.d value of 3.2 Å. Remarkably, the structural orientation of the RNA molecule in our docking-model of TkoTrm11–tRNAphe is similar to that of the truncated RNA molecule in the TmaThiI–RNA complex structure. The accepter stem in tRNA is a structural element important for the recognition of substrate tRNA in the both enzymes. It has previously been demonstrated that the 3′-ACCA end of tRNAPhe is essential for the C4-thiolation of U8 (42). In fact, the crystal structure of the TmaThiI–RNA complex reveals that the THUMP domain specifically recognizes the 3′-ACCA end, suggesting a molecular ruler that defines the length from the 3′-ACCA end to the modification site ((43), Figure 6B). The 3′-CCA end is bound into a groove of the THUMP domain, which is composed of the β5-strand (T102-K109), the α4-helix (V118-N132) and CCA-binding loop (F133-D144; Supplementary Figure S7). This groove in the THUMP domain of TmaThiI is structurally homologous to a THUMP domain groove in TkoTrm11 formed by the β5-strand (A85-T92), the α4-helix (V100-H112) and CCA-binding loop (A113-D124), although the residues of the groove appear to be slightly diversified between TmaThiI and TkoTrm11. Therefore, TkoTrm11 likely recognizes the 3′-ACCA end with site specificity like TmaThiI. To confirm this possibility, we selected five conserved residues (F86, K87, V88, V118 and L120) responsible for recognition of the 3′-ACCA end, followed by a mutagenesis study using the seven alanine-substituted mutants prepared (F86A, K87A, V88A, F86A/K87A/V88A, V118A, L120A and V118A/L120A; Supplementary Figure S6D). As shown in Figure 6C, the methylation activity of the two single mutants (F86A and K87A) was not significantly changed compared to that of WT TkoTrm11, except for the V88A mutant with an increased relative activity. The V118A and L120A mutants showed 50–70% reduction in relative activity compared to WT TkoTrm11. In the F86A/K87A/V88A and V118A/L120A mutants, the methylation activities were remarkably reduced, especially in the latter, with a decrease of ∼30% relative activity. We further performed a gel mobility shift assay to test the binding affinity of V118A/L120A to Tko tRNATrp. The amount of V118A/L120A–tRNA complex formation was considerably less than that of WT TkoTrm11–RNA, V118A-tRNA and L120A–tRNA complex formation (Figure 6E, F and G). Unbound, free tRNA was still detected in the gel for the V118A/L120A mutant, although the molecular mixing ratio between V118A/L120A and tRNA was 1:1. These results indicate that the seven conserved residues synergistically contribute to recognition of the 3′-ACCA end. In the crystal structure of the TmaThiI–RNA complex, various interactions (i.e. polar contact, hydrogen bond formation and van der Waals contact), except electrostatic ones, between the groove of the THUMP domain and the 3′-ACCA end were shown to be responsible for recognition of the 3′-CCA end. Probably, such interactions occur in the groove of the THUMP domain of TkoTrm11. We performed a mutational analysis for four Tko tRNATrp mutants (ΔA, ΔCA, ΔCCA and ΔACCA), in which the 3′-ACCA sequences of Tko tRNATrp were truncated one by one from the 3′ terminus of adenosine (Supplementary Figure S8A and B). Using purified wild-type (WT) Tko tRNATrp and its four mutants, their specific activities were measured at various times (Supplementary Figure S8C), and their relative activities at 8 min were further compared, as shown in Figure 6D. All mutants showed decreased activity compared to WT tRNATrp. The relative activities of ΔA, ΔCA, ΔCCA and ΔACCA mutants were gradually reduced to ∼60%, 50%, 30% and 10%, respectively, according to the deletion of one nucleotide from the 3′ terminus of Tko tRNATrp. Furthermore, we performed a gel mobility shift assay to confirm the binding affinity between WT TkoTrm11 and ΔACCA mutant (Figure 6H). The formation of WT TkoTrm11–ΔACCA complex yielded smeared bands, which reflected low binding affinity, compared to the formation of Wt TkoTrm11–tRNA complex. These results clearly demonstrate that the 3′-ACCA end is required for the total activity of TkoTrm11. However, the amplitude of decreased methylation activity in the ΔACCA mutant was rather low as compared to that observed for E.coli ThiI having <0.1% activity (42). In the case of ThiI, only the N-terminal THUMP-NFLD domain appeared to function as a tRNA-binding site, which could recognize not only the 3′-CCA end, but also the acceptor and T-stems (41,43). Free PPase domain of ThiI was unable to bind substrate tRNA. In contrast, the THUMP-NFLD domain of PabTrm11 showed rather low binding affinity to substrate tRNA (34), although we could not detect the formation of THUMP-NFLD domain–tRNA complex in TkoTrm11 (data not shown). Our mutational analyses described above showed that the linker region and RFM domain likely recognized substrate tRNA (Figure 4B and C). The formation of K151A/R152A–tRNA complex was not observed (Figure 5D), however, that of V118A/L120A–tRNA and WT TkoTrm11–ΔACCA complexes was still detected (Figure 6G and H). These findings indicate that the tRNA-binding affinities of the linker region and RFM domain maybe higher than that of the THUMP-NFLD domain in TkoTrm11. Accordingly, TkoTrm11 can maintain ∼10% relative activity using the ΔACCA mutant because it possesses RNA-binding sites in the THUMP domain, as well as in the linker region and RFM domain.

Figure 6.

TkoTrm11 specifically recognizes the 3′-ACCA end of tRNA through the THUMP domain common to other tRNA-modifying enzymes, TmaThiI, PfuTrm14 and CDAT8. (A) Ribbon diagram of crystal structure of dimeric TmaThiI in complex with truncated tRNA (PDB code, 4KR6). The THUMP, NFLD, PPase domains and truncated tRNA in the A-form structure are colored yellow, purple, gray and cyan, respectively. The THUMP, NFLD, PPase domains and truncated tRNA in the B-form structure are colored pink, blue, red and cyan, respectively. (B) Ribbon diagram of the TkoTrm11–tRNA complex model and the A-form of the TmaThiI–RNA complex structure based on the superimposed Cα atoms of the THUMP (red) and NFLD (green) domains of TkoTrm11 onto that of the THUMP (yellow) and NFLD (purple) domains of the TmaThiI structure (A-form). The tRNA of the TkoTrm11–tRNA complex model and RNA of TmaThiI–RNA complex are colored orange and cyan, respectively. (C) Methyl transfer activity of the alanine-substituted mutant proteins. The mutant name indicates the site of alanine substitution. The initial velocity of wild-type TkoTrm11 is expressed as 100%. Error-bar indicates the SD (standard deviation) that was calculated between three independent experiments. (D) Relative activity of methylation by TkoTrm11 with the 3′-terminal truncated Thermococcus kodakarensis tRNATrp (full-length 76 mer) mutants, ΔA (76A is truncated), ΔCA (76A and 75C are truncated), ΔCCA (76A, 75C and 74C are truncated) andΔACCA (76A, 75C, 74C and 73A are truncated). The specific activity of WT TkoTrm11 is expressed as 100%. Error-bar indicates the SD that was calculated between three independent experiments. (E) The binding-affinity values of WT TkoTrm11 and V118A mutant for Tko tRNATrp analyzed by the gel mobility shift assay. (F) The binding-affinity values of WT TkoTrm11 and L120A mutant for Tko tRNATrp analyzed by the gel mobility shift assay. (G) The binding-affinity values of WT TkoTrm11 and V118A/L120A mutant for Tko tRNATrp analyzed by the gel mobility shift assay. (H) The binding-affinity values of WT TkoTrm11for Tko tRNATrp and ΔACCA analyzed by the gel mobility shift assay. The formations of a complex by WT TkoTrm11 or each of the three mutants with Tko tRNATrp or ΔACCA and unbound free tRNA are indicated by two black lines labeled on the right side of the gel.

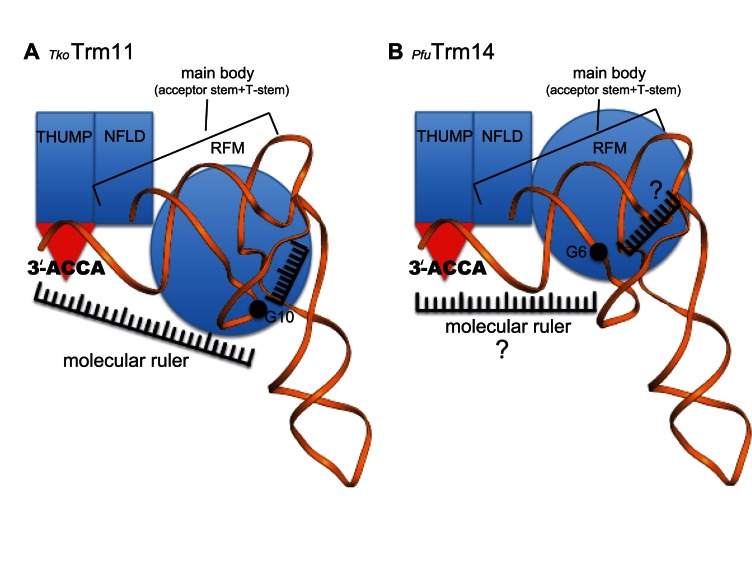

Therefore, we hypothesize that TkoTrm11 employs the following substrate recognition mechanism: specific binding of the 3′-ACCA end to the groove of the THUMP domain determines the length from the 3′-ACCA end to the methylation site at the catalytic center of the RFM domain, and recognition of V-loop by the RFM domain defines the length from the V-loop to the methylation site. The two molecular rulers would intersect at the methylation site, thereby defining the site specificity of TkoTrm11 (Figure 7A). Notably, the molecular ruler mechanism could be conserved in archeal Trm14, because the enzyme contains the NFLD and THUMP domains, which are structurally similar to those of TkoTrm11 and TmaThiI. In particular, the structural arrangement of PfuTrm14 is almost the same as that of TkoTrm11. Furthermore, PfuTrm14 possesses a groove of the THUMP domain responsible for specific binding of the 3′-ACCA end, and the groove is composed of sequences similar to those of TkoTrm11 and TmaThiI (Supplementary Figures S7 and S9A). The RFM domain of bacterial TrmN, which is almost identical to that of PfuTrm14, was shown to be responsible for the recognition of substrate tRNA (27). These observations indicate that PfuTrm14 probably employs the molecular ruler mechanism common to TkoTrm11. Nonetheless, the site specificity of PfuTrm14 is distinct from that of TkoTrm11. Moreover, structural comparison of TkoTrm11 and PfuTrm14 showed only two differences (Figure 2E, F and Supplementary Figure S9B): the linker region connecting the THUMP domain to the RFM domain; and the spatial location of the RFM domain, which might be caused by the difference in linker regions. We also found that the linker region of TkoTrm11 contributes to the recognition of tRNA by electrostatic interactions between the positively charged residues and the negatively charged phosphate groups (Figures 4B and 5D). Thus, our results allow us to propose molecular ruler mechanism models for the site specificity of two tRNA MTases, TkoTrm11 (Figure 7A) and PfuTrm14 (Figure 7B). The acceptor stem and T-stem play a significant role as the ‘main body,’ which is bound by the NFLD and THUMP domains, and thereby fixes the orientation of the stems as shown in the crystal structure of the TmaThiI–RNA complex and our docking model of the TkoTrm11–tRNAPhe complex (Figure 6A and B). The fixed orientation of acceptor stem and T-stem is probably a common feature of tRNA-modifying enzymes containing the NFLD and THUMP domains. The position of the catalytic center of the RFM domain in TkoTrm11 is distinct in PfuTrm14 because of the structural difference in the linker regions of TkoTrm11 and PfuTrm14. In TkoTrm11, the K151 and R152 of the linker region appears to be involved in the recognition of tRNA (Figure 5D), and the R317 and K320 of the RFM domain may recognize the V-loop of the tRNA responsible for the formation of m22G10. Therefore, the lengths from the 3′-ACCA end and the V-loop to the methylation site in TkoTrm11 are likely to be different from those in PfuTrm14, although the existence of molecular ruler remains uncertain in the RFM domain of PfuTrm14 (Figure 7A and B). Indeed, the lengths of the molecular ruler may have an effect on the specific position of methylation, resulting in the difference in site specificity of TkoTrm11 and PfuTrm14. In fact, TkoTrm11 specifically transfers a methyl group to either N2-guanosine or N2-monoguanosine at position 10 in tRNA, while the formation of N2-methylguanosine by PfuTrm14 is found at position 6. However, further structural determination of TkoTrm11–tRNA and PfuTrm14–tRNA complexes will be needed to ensure the proposed molecular ruler mechanism models for site specificity of TkoTrm11 and PfuTrm14.

Figure 7.

Cartoon diagram of the proposed tRNA recognition mechanism of (A) TkoTrm11 and (B) PfuTrm14.

In conclusion, we resolved the first X-ray crystal structure of TkoTrm11, and our results reveal that it is composed of NFLD, THUMP and RFM domains, and that one linker region formed by both an α-helix and a 310 helix connects the THUMP and RFM domains. There is striking structural similarity between the NFLD and THUMP domains of the tRNA-modifying enzymes TkoTrm11, PfuTrm14, TmaThiI and archeal CDAT8. The structural arrangement of TkoTrm11 is almost the same as that of PfuTrm14, indicating that TkoTrm11 and PfuTrm14 are derived from a common ancestor. However, each of the linker regions connecting the THUMP and RFM domains of these two tRNA MTases is distinct from the other. The linker region therefore appears to be involved in the specificity of methylation site of TkoTrm11 and PfuTrm14. The structure of the TkoTrm11–SAM complex showed that the SAM molecule is structurally extended in the pocket of the RFM domain, similar to that of the PfuTrm14–SAM complex. Furthermore, kinetic analysis identified the most important residues for the recognition of the SAM molecule. Our plausible docking model of the TkoTrm11–yeast tRNAPhe complex, which is based on biochemical results and structural similarity to the NFLD and THUMP domains of the TmaThiI–RNA complex, allow us to hypothesize that TkoTrm11 employs a molecular ruler mechanism by which specific binding of the 3′-ACCA end with the groove of the THUMP domain and recognition of the V-loop by the RFM domain define the lengths from the 3′-ACCA end and V-loop to the site of methylation. The intersection of two molecular rulers maybe a specific site for methylation. Moreover, the different lengths of molecular rulers between TkoTrm11 and PfuTrm14, which is probably caused by differences in their linker regions connecting the THUMP and RFM domains, might determine the specific site for methylation. Thus, our findings here provide a unified interpretation of the molecular mechanism of site specificity of tRNA MTase that contains the NFLD and THUMP domains.

ACCESSION NUMBERS

The atomic coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, www.rcsb.org (PDB ID code 5E71, 5E72).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their deepest sympathy to T.T. who is a co-author in this article. He passed away on March 13, 2013. The authors thank Dr Michael Gleghorn for his precious comments and suggestions. The authors also thank the staff members of the beam-line facility at SPring-8 (Hyogo, Japan) for their technical support during data collection. The synchrotron radiation experiments were performed at the BL38B1 beamline at SPring-8 with the approval of the Japan Synchrotron Radiation Research Institute (JASRI) (proposal nos. 2012A1098, 2013B1112 and 2014A1246). Finally, the authors thank the Advanced Research Support Center of Ehime University for technical assistance. The purification of TkoTrm11 and its mutants were carried out with an AKTAexplorer 100 at the Division of Applied Protein Research, Advance Research Support Center, Ehime University.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online.

FUNDING

Grant-in-Aid for Science Research (C) [15K06975 to A. H., in part]; Grant-in-Aid for Young Scientists (B) [24770125 to A. H.]; Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B) [19350087 and 23350081 to H. H.] from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science. Funding for open access charge: Grant-in-Aid for Science Research (C) [15K06975 to A. H.].

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cantara W.A., Crain P.F., Rozenski J., McCloskey J.A., Harris K.A., Zhang X., Vendeix F.A., Fabris D., Agris P.F. The RNA Modification Database, RNAMDB: 2011 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:D195–D201. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jühling F., Mörl M., Hartmann R.K., Sprinzl M., Stadler P.F., Pütz J. tRNAdb 2009: compilation of tRNA sequences and tRNA genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D159–D162. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Motorin Y. RNA Modification. eLS. 2015 doi:10.1002/9780470015902.a0000528.pub3. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abbott J.A., Francklyn C.S., Robey-Bond S.M. Transfer RNA and human disease. Front Genet. 2014;5:158. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2014.00158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Torres A.G., Batlle E., Ribas de Pouplana L. Role of tRNA modifications in human diseases. Trends Mol. Med. 2014;20:306–314. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2014.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hori H. Methylated nucleosides in tRNA and tRNA methyltransferases. Front Genet. 2014;5:144. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2014.00144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dennis P.P., Omer A. Small non-coding RNAs in Archaea. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2005;8:685–694. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2005.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Machnicka M.A., Milanowska K., Osman Oglou O., Purta E., Kurkowska M., Olchowik A., Januszewski W., Kalinowski S., Dunin-Horkawicz S., Rother K.M., et al. MODOMICS: a database of RNA modification pathways–2013 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:D262–D267. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Czerwoniec A., Kasprzak J.M., Kaminska K.H., Rother K., Pruta E., Bujnick J.M. Folds and functions of domains in RNA modification enzymes. In: Grosjean H, editor. DNA and RNA modification enzymes: Structure, mechanism, function and evolution. Austin: Landes Bioscience; 2009. pp. 289–302. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schubert H.L., Blumenthal R.M., Cheng X. Many paths to methyltransfer: a chronicle of convergence. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2003;28:329–335. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(03)00090-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anantharaman V., Koonin E.V., Aravind L. SPOUT: a class of methyltransferases that includes spoU and trmD RNA methylase superfamilies, and novel superfamilies of predicted prokaryotic RNA methylases. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2002;4:71–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Urbonavicius J., Skouloubris S., Myllykallio H., Grosjean H. Identification of a novel gene encoding a flavin-dependent tRNA:m5U methyltransferase in bacteria–evolutionary implications. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:3955–3964. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Delk A.S., Nagle D.P., Rabinowitz J.C., Straub K.M. The methylenetetrahydrofolate-mediated biosynthesis of ribothymidine in the transfer-RNA of Streptococcus faecalis: incorporation of hydrogen from solvent into the methyl moiety. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1979;86:244–251. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(79)90858-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Delk A.S., Nagle D.P., Rabinowitz J.C. Methylenetetrahydrofolate-dependent biosynthesis of ribothymidine in transfer RNA of Streptococcus faecalis. Evidence for reduction of the 1-carbon unit by FADH2. J. Biol. Chem. 1980;255:4387–4390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yamagami R., Yamashita K., Nishimasu H., Tomikawa C., Ochi A., Iwashita C., Hirata A., Ishitani R., Nureki O., Hori H. The tRNA recognition mechanism of folate/FAD-dependent tRNA methyltransferase (TrmFO) J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:42480–42494. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.390112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hamdane D., Argentini M., Cornu D., Golinelli-Pimpaneau B., Fontecave M. FAD/folate-dependent tRNA methyltransferase: flavin as a new methyl-transfer agent. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:19739–19745. doi: 10.1021/ja308145p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hamdane D., Guerineau V., Un S., Golinelli-Pimpaneau B. A catalytic intermediate and several flavin redox states stabilized by folate-dependent tRNA methyltransferase from Bacillus subtilis. Biochemistry. 2011;50:5208–5219. doi: 10.1021/bi1019463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hamdane D., Argentini M., Cornu D., Myllykallio H., Skouloubris S., Hui-Bon-Hoa G., Golinelli-Pimpaneau B. Insights into folate/FAD-dependent tRNA methyltransferase mechanism: role of two highly conserved cysteines in catalysis. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:36268–36280. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.256966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nishimasu H., Ishitani R., Yamashita K., Iwashita C., Hirata A., Hori H., Nureki O. Atomic structure of a folate/FAD-dependent tRNA T54 methyltransferase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2009;106:8180–8185. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901330106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Menezes S., Gaston K.W., Krivos K.L., Apolinario E.E., Reich N.O., Sowers K.R., Limbach P.A., Perona J.J. Formation of m2G6 in Methanocaldococcus jannaschii tRNA catalyzed by the novel methyltransferase Trm14. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:7641–7655. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roovers M., Oudjama Y., Fislage M., Bujnicki J.M., Versées W., Droogmans L. The open reading frame TTC1157 of Thermus thermophilus HB27 encodes the methyltransferase forming N2-methylguanosine at position 6 in tRNA. RNA. 2012;18:815–824. doi: 10.1261/rna.030411.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Awai T., Kimura S., Tomikawa C., Ochi A., Ihsanawati Bessho, Y., Yokoyama S., Ohno S., Nishikawa K., Yokogawa T., et al. Aquifex aeolicus tRNA (N2,N2-guanine)-dimethyltransferase (Trm1) catalyzes transfer of methyl groups not only to guanine 26 but also to guanine 27 in tRNA. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:20467–20478. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.020024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Constantinesco F., Benachenhou N., Motorin Y., Grosjean H. The tRNA(guanine-26,N2-N2) methyltransferase (Trm1) from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus furiosus: cloning, sequencing of the gene and its expression in Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:3753–3761. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.16.3753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Constantinesco F., Motorin Y., Grosjean H. Characterisation and enzymatic properties of tRNA(guanine 26, N2, N2)-dimethyltransferase (Trm1p) from Pyrococcus furiosus. J. Mol. Biol. 1999;291:375–392. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ihsanawati Nishimoto, M., Higashijima K., Shirouzu M., Grosjean H., Bessho Y., Yokoyama S. Crystal structure of tRNA N2,N2-guanosine dimethyltransferase Trm1 from Pyrococcus horikoshii. J. Mol. Biol. 2008;383:871–884. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.08.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Awai T., Ochi A., Ihsanawati Sengoku, T., Hirata A., Bessho Y., Yokoyama S., Hori H. Substrate tRNA recognition mechanism of a multisite-specific tRNA methyltransferase, Aquifex aeolicus Trm1, based on the X-ray crystal structure. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:35236–35246. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.253641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fislage M., Roovers M., Tuszynska I., Bujnicki J.M., Droogmans L., Versées W. Crystal structures of the tRNA:m2G6 methyltransferase Trm14/TrmN from two domains of life. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:5149–5161. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Armengaud J., Urbonavicius J., Fernandez B., Chaussinand G., Bujnicki J.M., Grosjean H. N2-methylation of guanosine at position 10 in tRNA is catalyzed by a THUMP domain-containing, S-adenosylmethionine-dependent methyltransferase, conserved in Archaea and Eukaryota. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:37142–37152. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403845200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Purushothaman S.K., Bujnicki J.M., Grosjean H., Lapeyre B. Trm11p and Trm112p are both required for the formation of 2-methylguanosine at position 10 in yeast tRNA. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2005;25:4359–4370. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.11.4359-4370.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Okada K., Muneyoshi Y., Endo Y., Hori H. Production of yeast (m2G10) methyltransferase (Trm11 and Trm112 complex) in a wheat germ cell-free translation system. Nucleic Acids Symp. Ser (Oxf). 2009:303–304. doi: 10.1093/nass/nrp152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liger D., Mora L., Lazar N., Figaro S., Henri J., Scrima N., Buckingham R.H., van Tilbeurgh H., Heurgué-Hamard V., Graille M. Mechanism of activation of methyltransferases involved in translation by the Trm112 'hub' protein. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:6249–6259. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mueller E.G., Buck C.J., Palenchar P.M., Barnhart L.E., Paulson J.L. Identification of a gene involved in the generation of 4-thiouridine in tRNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:2606–2610. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.11.2606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Aravind L., Koonin E.V. THUMP–a predicted RNA-binding domain shared by 4-thiouridine, pseudouridine synthases and RNA methylases. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2001;26:215–217. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(01)01826-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gabant G., Auxilien S., Tuszynska I., Locard M., Gajda M.J., Chaussinand G., Fernandez B., Dedieu A., Grosjean H., Golinelli-Pimpaneau B., et al. THUMP from archaeal tRNA:m22G10 methyltransferase, a genuine autonomously folding domain. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:2483–2494. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Renalier M.H., Joseph N., Gaspin C., Thebault P., Mougin A. The Cm56 tRNA modification in archaea is catalyzed either by a specific 2′-O-methylase, or a C/D sRNP. RNA. 2005;11:1051–1063. doi: 10.1261/rna.2110805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Urbonavicius J., Armengaud J., Grosjean H. Identity elements required for enzymatic formation of N2,N2-dimethylguanosine from N2-monomethylated derivative and its possible role in avoiding alternative conformations in archaeal tRNA. J. Mol. Biol. 2006;357:387–399. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.12.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Randau L., Stanley B.J., Kohlway A., Mechta S., Xiong Y., Söll D. A cytidine deaminase edits C to U in transfer RNAs in Archaea. Science. 2009;324:657–659. doi: 10.1126/science.1170123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Waterman D.G., Ortiz-Lombardía M., Fogg M.J., Koonin E.V., Antson A.A. Crystal structure of Bacillus anthracis ThiI, a tRNA-modifying enzyme containing the predicted RNA-binding THUMP domain. J. Mol. Biol. 2006;356:97–110. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Baker B.J., Tyson G.W., Webb R.I., Flanagan J., Hugenholtz P., Allen E.E., Banfield J.F. Lineages of acidophilic archaea revealed by community genomic analysis. Science. 2006;314:1933–1935. doi: 10.1126/science.1132690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Palenchar P.M., Buck C.J., Cheng H., Larson T.J., Mueller E.G. Evidence that ThiI, an enzyme shared between thiamin and 4-thiouridine biosynthesis, may be a sulfurtransferase that proceeds through a persulfide intermediate. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:8283–8286. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.12.8283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tanaka Y., Yamagata S., Kitago Y., Yamada Y., Chimnaronk S., Yao M., Tanaka I. Deduced RNA binding mechanism of ThiI based on structural and binding analyses of a minimal RNA ligand. RNA. 2009;15:1498–1506. doi: 10.1261/rna.1614709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lauhon C.T., Erwin W.M., Ton G.N. Substrate specificity for 4-thiouridine modification in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:23022–23029. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401757200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Neumann P., Lakomek K., Naumann P.T., Erwin W.M., Lauhon C.T., Ficner R. Crystal structure of a 4-thiouridine synthetase-RNA complex reveals specificity of tRNA U8 modification. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:6673–6685. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Atomi H., Fukui T., Kanai T., Morikawa M., Imanaka T. Description of Thermococcus kodakaraensis sp. nov., a well studied hyperthermophilic archaeon previously reported as Pyrococcus sp. KOD1. Archaea. 2004;1:263–267. doi: 10.1155/2004/204953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fukui T., Atomi H., Kanai T., Matsumi R., Fujiwara S., Imanaka T. Complete genome sequence of the hyperthermophilic archaeon Thermococcus kodakaraensis KOD1 and comparison with Pyrococcus genomes. Genome Res. 2005;15:352–363. doi: 10.1101/gr.3003105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Doublié S. Preparation of selenomethionyl proteins for phase determination. Methods Enzymol. 1997;276:523–530. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Otwinowski Z., Minor W. Processing of X-ray Diffraction Data collected in oscillation mode. Methods in Enzymol. 1997;276:307–326. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Adams P., Grosse-Kunstleve R., Hung L., Ioerger T., McCoy A., Moriarty N., Read R., Sacchettini J., Sauter N., Terwilliger T. PHENIX: building new software for automated crystallographic structure determination. Acta Crystallogr D Biol. Crystallogr. 2002;58:1948–1954. doi: 10.1107/s0907444902016657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Terwilliger T.C. Automated side-chain model building and sequence assignment by template matching. Acta Crystallogr D Biol. Crystallogr. 2003;59:45–49. doi: 10.1107/S0907444902018048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Emsley P., Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D Biol. Crystallogr. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.McCoy A., Grosse-Kunstleve R., Adams P., Winn M., Storoni L., Read R. Phaser crystallographic software. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2007;40:658–674. doi: 10.1107/S0021889807021206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Laskowski R., MacArthur M., Moss D., Thoronton J. PROCHECK: a program to check the stereochemical quality of protein structures. J. Appl. Cryst. 1992;26:283–291. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hori H., Suzuki T., Sugawara K., Inoue Y., Shibata T., Kuramitsu S., Yokoyama S., Oshima T., Watanabe K. Identification and characterization of tRNA (Gm18) methyltransferase from Thermus thermophilus HB8: domain structure and conserved amino acid sequence motifs. Genes Cells. 2002;7:259–272. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.2002.00520.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]