Abstract

As a fungal etiology has been proposed to underlie severe nasal polyposis, the present study was undertaken to assess local antifungal immune reactivity in nasal polyposis. For this purpose, microbial colonization, along with the pattern of T helper 1 (Th1)/Th2 cytokine production and Toll-like receptor (TLR) expression, was evaluated in patients with nasal symptoms and with and without polyposis and in healthy subjects. The results show that Th2 reactivity was a common finding for patients with nasal polyposis regardless of the presence of microbes. The production of interleukin-10 was elevated in patients with bacterial and, particularly, fungal colonization, while both TLR2 expression and TLR4 expression were locally impaired in microbe-colonized patients. Eosinophils and neutrophils, highly recruited in nasal polyposis, were found to exert potent antifungal effector activities toward conidia and hyphae of the fungus and to be positively regulated by TLR2 or TLR4 stimulation. Therefore, a local imbalance between activating and deactivating signals to effector cells may likely contribute to fungal pathogenicity and the expression of local immune reactivity in nasal polyposis.

Nasal polyposis is a chronic inflammatory disease of the nasal mucosa (5). The clinical picture shows great heterogeneity, ranging from single polyps to almost complete polypoid transformation of the mucosae in all paranasal sinuses (26). Despite the prevalence and long history of nasal polyps, many questions are still unanswered with respect to the incidence and pathogenesis of nasal polyposis, though the condition is more common in certain medical disorders (15, 26). It is frequently associated with different local inflammatory diseases, such as chronic rhinosinusitis, cystic fibrosis, and Kartagener's syndrome (26, 33).

The role of infection as a cause of or effect on nasal polyps is debated. Clinical as well as experimental studies indicate that nasal polyp formation and growth are activated and perpetuated by an integrated process of mucosal epithelium and matrix and inflammatory cells, which in turn may be initiated by both infectious and noninfectious inflammations (23). Experimental models in which multiple epithelial disruptions with proliferating granulation tissue have been initiated by bacterial infection with Streptococcus pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus, Bacteroides fragilis (all common pathogens in sinusitis), or Pseudomonas aeruginosa (24) have been described previously. It appears that the cellular events of polyp formation are the results of an inflammatory reaction not directly related to the presence of a given microbial species but to the potential of a microorganism to induce trauma or epithelial desquamation.

Fungal infection of the paranasal sinuses may occur in both immunocompromised and immunocompetent individuals. Aspergillus spp. are the most common fungal species found in both groups (32). A fungal etiology has been proposed to underlie severe nasal polyps in general (35). While allergic fungal sinusitis is a well-defined clinical entity with recognized diagnostic criteria, the ubiquitous nature of fungal spores makes the role of fungal infection in patients with nasal polyps difficult to determine (5).

Recent studies provide evidence for immunopathogenic mechanisms underlying the orchestration of both the innate and the adaptive immune responses in nasal polyposis (9, 20, 31). Tissue eosinophilia is the typical histological feature in most nasal polyps. Although still controversial (14, 19), the production of T helper 2 (Th2) cytokines, including interleukin-4 (IL-4) and IL-5, by infiltrating Th cells is considered to contribute to the allergic mechanism of eosinophilia, whereas the nonallergic mechanism involves mainly gamma interferon (10). It is now clear that the induction of adaptive Th cell responses is under the control of a set of germ line-encoded receptors (Toll-like receptors [TLRs]) present on cells of the innate immune system (2). TLRs are a family of conserved, mammalian cellular receptors that mediate cellular responses to structurally conserved, pathogen-associated microbial products (2). All TLRs activate a core set of stereotyped responses, such as inflammation (25). However, individual TLRs can also induce specific programs in cells of the innate immune system that are tailored for the particular pathogen (6, 25, 28). Recent evidence indicates a possibly important immunological sentinel function of the upper-airway mucosa (9, 31). For instance, the fact that human mast cells isolated from nasal polyps express a unique profile of TLRs suggests a specialized role for TLRs in the local host response to bacterial and fungal pathogens (18).

To correlate local immune reactivity with microbial colonization in nasal polyposis, in the present study, we have evaluated the microbial colonization and the parameters of local immune reactivity, such as Th1/Th2 cytokine production and TLR expression, in patients with nasal symptoms with and without polyposis and in healthy subjects.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects and study design.

Table 1 gives the clinical information and the characteristics of the patient populations of the present study. Forty adult subjects with nasal polyps (NP+ patients) attending the Division of Otorhinolaryngology of the Monteluce Hospital at the Medical University of Perugia, Perugia, Italy, were included in the study. Clinical data on nasal symptoms were obtained by interviewing the patients and/or their relatives. All the patients had nasal symptoms (nasal obstruction, anosmia, sneezing, rhinorrhea, and itching) ranging from moderate to severe, and three patients were overtly atopic. Polyps were diagnosed by using either anterior rhinoscopy or standard nasal endoscopy with a 4-mm-diameter fiber-optic endoscope (after a topical decongestant and a topical anesthetic had been applied) and were resected with the patient being under conventional antibacterial chemotherapy. Additional groups included 12 sex- and age-matched patients with nasal symptoms but without polyps (NP− patients) and 10 healthy controls. Healthy controls were not allowed to have airborne allergies or any ongoing nasal symptoms (no nasal congestion and no ongoing infection in the nasal area); they were also not allowed to have had earlier surgery in the nasal or sinus region or any ongoing nasal medical treatment. Nasal lavage specimens were obtained upon endoscopic examination (12). Briefly, after excessive mucus was cleaned out by forceful exsufflation, the subjects were allowed to incline their necks approximately 45° from the horizontal while in a sitting position. Five milliliters of phosphate-buffered saline solution was poured into the antral part of the nose by means of a syringe with a cap on top to prevent the solution from leaking out. The solution was poured twice (in and out) from the syringe into the cavity while the subjects did not breathe or swallow. The gathered solution was stored at 4°C for a maximum of 2 h until it was processed. Nasal lavage specimens were centrifuged at 1,000 × g for 10 min, and the cell pellet was processed for differential cell morphology by cytospin staining with a May-Grünwald-Giemsa stain. The pellet was also subjected to qualitative and quantitative microbial cultures. Excised nasal polyps were immediately divided in two parts: one part was ground and subjected to investigation for microbiological parameters, and the other was frozen immediately in liquid nitrogen and used for total RNA extraction. Most polyps arose from the anterior end of the middle turbinate or the superior uncinate process mucosa. As controls, tissues from the same area of mucosae from healthy subjects were obtained. Two months after polypectomy, one further nasal lavage was performed to assess changes in the microbial population of nasal cavities.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of NP+ and NP− patients or healthy controls

| Parametera | Value (%) for:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| NP+ patients (n = 40) | NP− patients (n = 12) | Healthy controls (n = 10) | |

| No. of males | 30 (75) | 9 (75) | 7 (70) |

| No. of females | 10 (25) | 3 (25) | 3 (30) |

| Age (yr) | 50 ± 17 | 46 ± 21 | 46 ± 22 |

| No. of patients with: | |||

| Atopy | 3 (8) | 2 (17) | 0 (0) |

| Nasal blockage | 40 (100) | 12 (100) | 0 (0) |

| Anosmia | 40 (100) | 12 (100) | 0 (0) |

| Rhinorrhea | 40 (100) | 12 (100) | 0 (0) |

| Sneezing | 40 (100) | 12 (100) | 0 (0) |

| Facial pain | 9 (23) | 3 (25) | 0 (0) |

| Itching | 40 (100) | 12 (100) | 0 (0) |

Atopy was present if the patient exhibited one or more immediate skin reactions to 15 ubiquitous inhaled allergens. NP+ and NP− patients received at least one cycle (3 months) of inhalation corticosteroid therapy (10 μg of Aircort per puff, twice daily; Italchimici, Lumezzane S.A., Brescia, Italy), but none received systemic antibiotics (other than the preoperative treatment for patients undergoing polypectomy). As per the antibiotic policy during the study, systemic antibiotics were given only in cases of infection (i.e., a fever of 38.5°C, leukocytosis of >12,000 × 109/liter, and an elevated level of C-reactive protein [>15 μg/ml] combined with purulent secretions).

Permission to conduct the study was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the Monteluce Hospital, and all the patients who participated in the study provided informed consent.

Microbial investigations.

Microbial cultures for the isolation of aerobic and/or anaerobic bacterial and fungal species were performed according to standardized procedures (21). The isolated bacteria were identified to the species level through Sceptor system and Phoenix system biochemical tests (Becton Dickinson, Paramus, N.J.). Fungi were identified to the genus or species level through morphological analysis of the colonies, microscopic analysis of mycelia after staining with lactophenol cotton blue (Becton Dickinson), and biochemical tests.

Microorganisms.

A strain of Aspergillus fumigatus was obtained from a fatal case of pulmonary aspergillosis at the Infectious Diseases Institute of the University of Perugia. Resting conidia were harvested by extensive washing of the slant culture with 5 ml of 0.025% Tween 20 in saline. For generation of hyphae, resting and swollen conidia were allowed to germinate (>98% germination) by incubation in Sabouraud broth (for ∼20 and 6 h, respectively) at 37°C (6, 30).

Cell isolation.

Human polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMNs) were obtained from the heparinized whole blood of healthy donors, after donors gave their written informed consent, by lysis with ammonium chloride and fractionation by Ficoll-Hypaque (Pharmacia Fine Chemicals, Uppsala, Sweden) centrifugation. The purity of PMN preparations was >97%, as determined by Giemsa staining. Typical recovery was 3 million to 5 million PMNs per ml of collected blood. Eosinophils were purified from PMNs by negative selection with CD16 microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany) as described previously (11). The purity of eosinophils counted with Randolph's stain was >98%. A typical recovery was 1 × 105 to 3 × 105 eosinophils per ml of collected blood. PMNs and eosinophils were isolated before each experiment and used immediately. Endotoxin was depleted from all solutions by use of Detoxi-Gel (Pierce, Rockford, Ill.).

Antifungal effector activity.

For phagocytosis, PMNs and eosinophils were incubated at 37°C with resting Aspergillus conidia for 60 min at an effector cell-to-fungal cell ratio of 1:3. The percentage of internalization was calculated on Giemsa-stained cytospin preparations, as previously described (6). For fungicidal activity, effector cells were incubated with unopsonized resting conidia for 120 min, and the percentage of CFU inhibition (mean ± standard error [SE]), referred to as conidiocidal activity, was determined as previously described (6). To assess the damage to the hyphae, viability staining with the fluorescence probe FUN-1 (Molecular Probes Europe BV, Leiden, The Netherlands) was examined in a Titertek II fluorescence microplate reader (Flow Laboratories, Milan, Italy) at a 485-nm excitation wavelength and with a 620-nm emission wavelength (6). As controls, hyphae were incubated without cells and were treated with 96% ethanol. PMN production of reactive oxygen intermediates was done by quantifying superoxide anion (O2−) production by measuring the superoxide dismutase-inhibitable reduction of cytochrome c (6). For TLR stimulation, PMNs and eosinophils were preexposed for 120 min to zymosan (10 μg/ml; Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.), as a TLR2 stimulus, and ultrapure lipopolysaccharide (10 μg/ml; Labogen S.r.l., Milan, Italy) from a Salmonella minnesota strain, as a TLR4 stimulus, before the addition of resting conidia.

ELISAs.

The levels of cytokines in the nasal lavage specimens, polyp homogenates, and culture supernatants were determined by kit enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) (R&D Systems, Inc., Space Import-Export S.r.l., Milan, Italy). The detection limits (in picograms per milliliter) of the assays were 10 for tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), 5 for IL-5 and IL-10, and 0.5 for IL-4.

RT-PCR and real-time RT-PCR.

Total RNA was extracted and reverse transcribed as described previously (30). PCR amplification of the housekeeping eukaryotic 18S rRNA gene was performed for each sample to control for sample loading and to allow normalization between samples, per the manufacturer's instructions (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.). For real-time reverse transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR), the eukaryotic 18S rRNA gene-normalized data were expressed as relative levels of cytokine mRNA (change in cycle threshold) in polyps from NP+ patients compared to those in nasal brush specimens from healthy subjects (30).

Statistical analysis.

Fisher's exact test was used to assess the association of nasal polyps with the presence and type of microbial colonization. Statistical analysis was performed using Stata (College Station, Tex.) statistical software, release 8.2. Student's t test or analysis of variance and Bonferroni's test were used to determine the statistical significance (defined as a P of <0.05) of differences in results for experimental groups.

RESULTS

Evaluation of microbial growth in nasal polyposis.

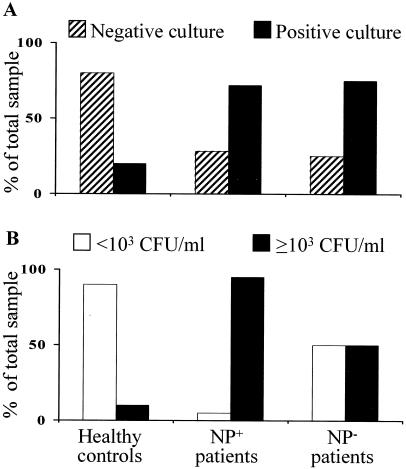

To quantitate the microbial colonization in NP+ and NP− patients and healthy controls, microbiological cultures were set up with the nasal lavage fluids. The majority of cultures (80%) were negative for microbial growth in healthy controls, and lower percentages of negative cultures were observed for NP+ (27%) and NP− (25%) patients (Fig. 1A). In addition, the microbial load of the majority of positive cultures from healthy controls was less than 103 CFU/ml of sample, as opposed to the higher load observed in NP+ and NP− patients (more than 103) (Fig. 1B). Upon qualitatively evaluating the microbial burden, it was found that the majority of positive cultures (about 90%) from healthy controls and NP− patients consisted of bacterial species belonging to coagulase-negative staphylococci and alpha-hemolytic streptococci. No colonizing fungal species were isolated. In contrast, both bacterial and fungal species were isolated in NP+ patients, although the species were never isolated together from a single patient at levels superior to the threshold value (103 CFU/ml) (Table 1). It is worth noting that species of the genus Staphylococcus accounted for the highest percentage (more than 30%) of the different bacteria, and species of the genus Aspergillus were the most commonly isolated fungi (42%) (Table 2). Therefore, these data indicate that the microbial colonization of patients with polyps varied, consisting of either bacteria or fungi. Moreover, the differences observed in NP+ and NP− patients indicate the relative independence of microbial colonization from corticosteroid exposure. Microbial growth was also assessed in the nasal lavage specimens 2 months after polypectomy. It was found that the positive fungal cultures disappeared but that the level of bacterial (mainly S. aureus) colonization did not vary (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Microbial colonization in nasal lavage specimens of NP+ and NP− patients or healthy controls. The nasal lavages and microbial growth were carried out as described in Materials and Methods.

TABLE 2.

Bacterial and fungal species isolated from the nasal cavities of NP+ and NP− patients or healthy controls or healthy controls

| Parameter | Value (%) for:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Healthy controls (n = 10) | NP+ patients (n = 40) | NP− patients (n = 12) | |

| Total no. of culture-positive specimensa | 2 (20) | 29 (73) | 9 (64) |

| No. of specimens with any bacterial species: | 2 (20) | 16 (40) | 9 (64) |

| Hemophilus influenzae | 1 (3) | 1 (7) | |

| Streptococcus pyogenes | 1 (3) | ||

| α-hemolytic streptococci | 1 (10) | 4 (10) | 2 (14) |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 6 (16) | 1 (7) | |

| Coagulase-negative staphylococci | 1 (10) | 3 (8) | 5 (36) |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 1 (3) | ||

| No. of specimens with any fungal speciesa: | 0 (0) | 13 (33) | 0 (0) |

| Aspergillus niger | 8 (21) | ||

| Aspergillus fumigatus | 3 (8) | ||

| Aspergillus candidus | 1 (3) | ||

| Penicillium spp. | 1 (3) | ||

Values are statistically significant.

The analysis of inflammatory-cell recruitment in the different groups showed the absence of inflammatory cells in healthy controls and in NP− patients, as opposed to the presence of numerous PMNs and eosinophils, associated with few lymphocytes and virtually no mononuclear phagocytes, in NP+ patients with either bacterial or fungal colonization (data not shown).

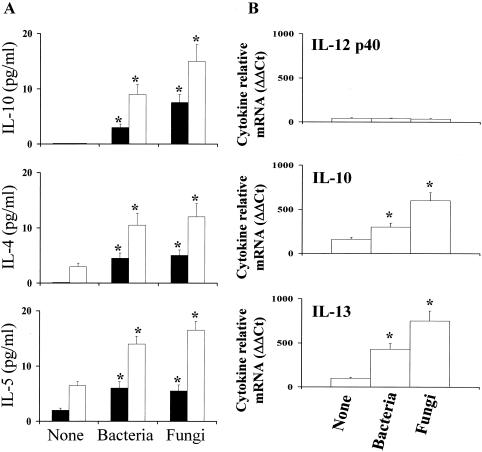

Cytokine production in nasal polyposis.

To find out the possible correlation between the pattern of microbial colonization and local immunological reactivity in nasal polyposis, we determined the pattern of local proinflammatory (TNF-α), anti-inflammatory (IL-10), and type 1 (IL-12 p70) and type 2 (IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13) cytokine production in NP+ patients, as a number of cytokines have been implicated in the pathogenesis of inflammatory sinus diseases (10, 14). For this purpose, the levels of these cytokines were assessed in the nasal lavage specimens and polyp homogenates by a specific ELISA and real-time RT-PCR. The results showed that no detectable levels of TNF-α were measured, regardless of microbial colonization (data not shown), unlike with IL-10, whose production was particularly elevated in NP+ patients associated with fungal colonization. No IL-10 was detected in NP+ patients without microbial colonization (Fig. 2A). RT-PCR confirmed the higher expression of IL-10 mRNA in NP+ patients with fungal colonization (Fig. 2B). In terms of type 1 and type 2 cytokine production, elevated levels of type 2 cytokines (IL-4 and IL-5) and high levels of IL-13 mRNA expression were observed in NP+ patients with either bacterial or fungal growth (Fig. 2). IL-12 p40 production could not be measured by either ELISA (data not shown) or RT-PCR (Fig. 3B). Therefore, these data suggest that the local expression of type 1 and type 2 reactivity is skewed toward type 2 reactivity in the presence of either bacterial or fungal colonization.

FIG. 2.

Local cytokine production in NP+ patients. Cytokine production was detected by ELISA (A) or real time RT-PCR (B) in the nasal lavage specimens (black bars) or nasal polyps (white bars) of NP+ patients with or without (None) microbial colonization. Levels of cytokines were below the detection limit of the assays in the nasal lavage specimens from healthy donors. In the RT-PCR assay, the results are expressed as relative levels of cytokine mRNA (change in cycle threshold [ΔΔCt]) in polyps from NP+ patients compared to those in nasal brush specimens from healthy subjects. *, P < 0.05 for results for patients with bacterial or fungal colonization versus those for noncolonized patients.

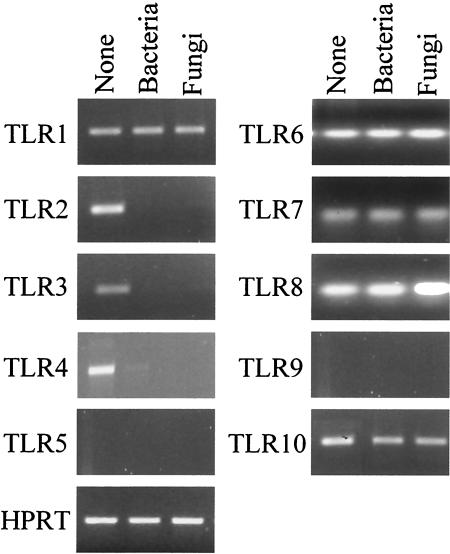

FIG. 3.

TLR expression in NP+ patients. TLR expression in nasal polyps that were positive for bacteria, fungi, or neither (None) as determined by RT-PCR is shown. TLR expression was inconsistently detected in the nasal brush specimens from healthy subjects. cDNA levels were normalized against levels of the hypoxanthine phosphoribosyltransferase gene. Shown are the results from one experiment representative of five done.

TLR expression in nasal polyposis.

Because TLR expression has been detected in cells from nasal polyps (18) and TLRs very likely play an important role in governing the local inflammatory reaction to microbial stimuli (28, 31), we analyzed TLR gene expression in nasal polyps positive for Staphylococcus, Aspergillus, or neither organism. No differences were observed among groups in terms of TLR5, TLR6, TLR7, TLR8, TLR9, and TLR10 expression, as these TLRs were never (TLR5 and TLR9) or always (TLR6, TLR7, TLR8, and TLR10) detected. In contrast, TLR1, TLR2, TLR3, and TLR4 were consistently expressed in noncolonized patients, but only TLR1, and not TLR2, TLR3, or TLR4, was detected in microbially colonized patients (Fig. 3). TLR expression was inconsistently detected in the nasal brush specimens from healthy subjects (data not shown).

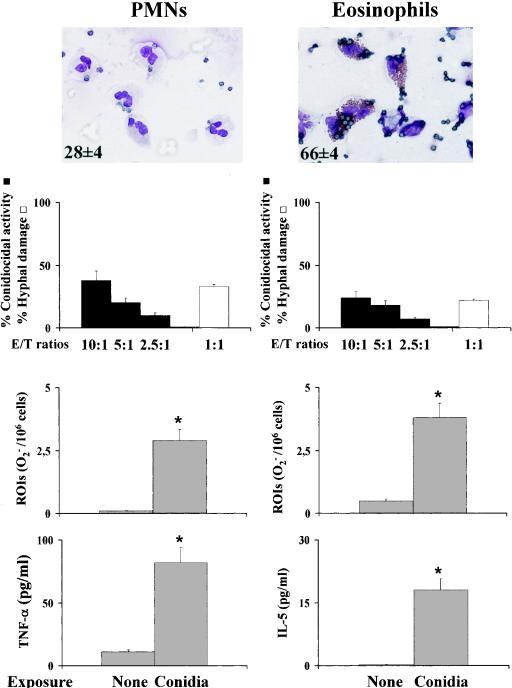

TLRs govern the antimicrobial functions of effector cells.

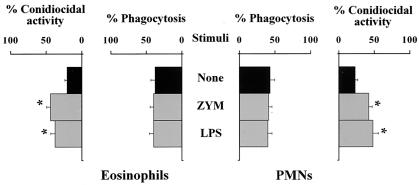

To correlate TLR expression with the functional activities of TLRs on inflammatory cells, we assessed the effects of selected TLR ligands on the antifungal effector functions of PMNs and eosinophils, as these cells were abundantly present in NP+ patients with fungal colonization and, at least for PMNs, are known to respond to A. fumigatus in a TLR-dependent manner (6, 16). For this purpose, peripheral PMNs and eosinophils were comparatively analyzed for phagocytosis, conidiocidal activity, hyphal damage, and oxidant and cytokine production in the presence of TLR2 and TLR4 ligands, as they are known to affect antifungal PMN functions (6). Both PMNs and eosinophils phagocytosed and killed resting conidia, although to various degrees. Eosinophils, more than PMNs, were particularly active at phagocytosing resting conidia, with the phagocytosis of multiple conidia being observed most often, and slightly less active at killing them. In contrast, PMNs were more active than eosinophils in damaging hyphae. In terms of secretory functions, both effectors produced reactive oxygen intermediates and cytokines upon exposure to the fungus, with PMNs producing mainly TNF-α and eosinophils producing IL-5 (Fig. 4). In assessing the effect of stimulation with the relevant TLR ligands, we found that both TLR2 and TLR4 stimulation increased the conidiocidal activity of both PMNs and eosinophils (Fig. 5). Interestingly, TLR2 stimulation significantly increased TNF-α production by PMNs, while TLR4 stimulation also induced IL-10 production (data not shown). Therefore, the local expression of TLRs in nasal polyps may profoundly affect local effector cell reactivity and immune reactions to fungi.

FIG. 4.

Antifungal and immunomodulatory activities of PMNs and eosinophils. Purified PMNs and eosinophils from peripheral blood were incubated with resting conidia and assessed for phagocytosis, fungicidal activity, and oxidant and cytokine production as detailed in Materials and Methods. The hyphal damage activity was assessed as detailed in Materials and Methods. The numbers inside the micrographs are percentages (means ± SEs) of phagocytosis. Photographs were taken with a high-resolution-microscopy camera (AxioCam color). Experiments were done in triplicate. Values are means ± SEs of results for samples taken from five independent experiments. *, P < 0.05 for results for conidium-stimulated versus unstimulated (None) cells. ROIs, reactive oxygen intermediates.

FIG. 5.

Effects of TLR agonists on the antifungal functions of eosinophils and PMNs. Peripheral PMNs and eosinophils were pretreated with zymosan (ZYM; 10 μg/ml) or lipopolysaccharide (LPS; 10 μg/ml) for 120 min before the assessment of effector functions, after a subsequent incubation with resting conidia (120 min). For phagocytosis and fungicidal activity, see Materials and Methods. Values are percentages (means ± SEs) for samples taken from five independent experiments. *, P < 0.05 for functions with and without (None) TLR ligands.

DISCUSSION

The present study shows that microbial colonization is associated with defined local immune reactivity in NP+ patients, namely, an elevated production of both type 2 cytokines and IL-10. No major differences in terms of IL-4 and IL-5 production and IL-13 expression were observed between NP+ patients colonized with either bacterial or fungal species, a finding suggesting the existence of a common predisposing condition, regardless of microbial presence. The finding that the production of IL-4 and IL-5 was appreciated in NP+ patients without microbial colonization lends support to this conclusion. In contrast, and interestingly, the production of IL-10 was significantly elevated in NP+ patients with fungal colonization. Because IL-10 negatively affects the antifungal activity of effector phagocytes (29), it is likely that elevated IL-10 production could serve to limit the inflammatory reaction locally, including the ability to control fungal growth. In addition, as higher levels of IL-10 are seen in asthmatic NP+ patients than in nonasthmatic NP+ patients (8, 27), it seems that the presence of fungal elements may worsen local allergic reactivity, as suggested previously (13, 35). In this regard, it is worth mentioning that fungal species were virtually never recovered from NP− patients.

The recruitment of inflammatory cells, mainly PMNs and eosinophils, was not impaired in colonized patients, a finding suggesting that the qualitative inflammatory response could be locally affected in these patients. In this regard, it was of interest to find out that the patterns of TLR expression were different between NP+ patients with and without microbial colonization. Recent evidence indicates a possibly important immunological sentinel function of the upper-airway mucosa (9, 31). For instance, the levels of expression of human β-defensins, TLR2, and TLR4 were different in various upper-airway tissues and in different disease states (9). In addition, the fact that mast cells isolated from nasal polyps express a unique profile of TLRs suggests a specialized role for TLRs in the local host response to bacterial and fungal pathogens (18). We found that the expression of TLR2, TLR3, and TLR4 was consistently downregulated in NP+ patients with microbial colonization, as opposed to that in NP+ patients without colonization. Because both TLR2 and TLR4 participate in host recognition of and immune response to Aspergillus spp. (6, 16, 22, 29, 34), the impaired expression of both TLRs may play a pathogenic role in the establishment of fungal colonization and/or infection. It has already been shown that the conidiocidal activity of murine PMNs is greatly impaired in the absence of either TLR2 or TLR4 (6). Here we confirm this finding by showing that the stimulation of either TLR2 or TLR4 significantly increased the conidiocidal activity of peripheral PMNs. Preliminary evidence suggests dysregulated antifungal effector activities of PMNs from NP+ patients, such as defective conidiocidal and secretory activities (data not shown). Although it remains to be determined whether the impaired antifungal activity of inflammatory cells is associated with local TLR reactivity, our findings support the notion that TLRs may influence airway reactivity (31). Functional polymorphisms in human TLR4 that affect airway reactivity have indeed been described previously (3).

One interesting observation of the present study concerns the antifungal effector activity of eosinophils. Eosinophils are selectively recruited in nasal polyps (17) and are considered to play a pathogenic role in polyp formation (4). We found in this study that eosinophils are endowed with a potent phagocytic activity and an oxidative killing capacity affecting Aspergillus conidia and hyphae and produce IL-5. Preliminary observations indicate that eosinophils also undergo massive degranulation upon conidial ingestion (data not shown). Therefore, eosinophils appear to share with conventional antifungal effector cells the abilities to oppose fungal infectivity and influence the local immune inflammatory response. Because the effector activity of eosinophils, similar to that of PMNs, was sensitive to TLR2 or TLR4 stimulation, it will be important to understand, once allergic and nonallergic diseases are established, whether infectious triggers may worsen inflammation by TLR signaling on local inflammatory cells. A recent study has shown that stimulation of TLR2 by lipopeptides abolished allergic Th2 responses in the airway (1). Therefore, the possibility that the stimulation of selected TLRs can be exploited for the treatment of allergic diseases exists.

In conclusion, the present study suggests that a local imbalance between activating and deactivating signals to effector cells may likely contribute to fungal pathogenicity and the expression of local immune reactivity in nasal polyposis. The fact that the local immune reactivity may be affected by signaling through selected TLRs implies that TLR manipulation by fungal pathogens alone or concomitantly with other microbial species may have an impact on local expression of morbidity. Therefore, in addition to staphylococci (7), fungi may have an immunopathogenic role in nasal polyposis. Moreover, our study suggests that TLR manipulation is amenable to controlling local inflammatory pathology and microbial growth.

Acknowledgments

We thank Lara Bellocchio for superb editorial assistance.

This study was supported by the National Research Project on AIDS (contract 50D.27, Opportunistic Infections and Tuberculosis) and by project 1AF/F (Immunotherapeutic Approaches in Fungal Infections) from the ISS, Rome, Italy.

Editor: T. R. Kozel

REFERENCES

- 1.Akdis, C. A., F. Kussebi, B. Pulendran, M. Akdis, R. P. Lauener, C. B. Schmidt-Weber, S. Klunker, G. Isitmangil, N. Hansjee, T. A. Wynn, S. Dillon, P. Erb, G. Baschang, K. Blaser, and S. S. Alkan. 2003. Inhibition of T helper 2-type responses, IgE production and eosinophilia by synthetic lipopeptides. Eur. J. Immunol. 33:2717-2726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akira, S. 2003. Mammalian Toll-like receptors. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 15:5-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arbour, N. C., E. Lorenz, B. C. Schutte, J. Zabner, J. N. Kline, M. Jones, K. Frees, J. L. Watt, and D. A. Schwartz. 2000. TLR4 mutations are associated with endotoxin hyporesponsiveness in humans. Nat. Genet. 25:187-191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bachert, C., P. Gevaert, G. Holtappels, C. Cuvelier, and P. van Cauwenberge. 2000. Nasal polyposis: from cytokines to growth. Am. J. Rhinol. 14:279-290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bateman, N. D., C. Fahy, and T. J. Woolford. 2003. Nasal polyps: still more questions than answers. J. Laryngol. Otol. 117:1-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bellocchio, S., C. Montagnoli, S. Bozza, R. Gaziano, G. Rossi, S. S. Mambula, A. Vecchi, A. Mantovani, S. M. Levitz, and L. Romani. 2004. The contribution of the Toll-like/IL-1 receptor superfamily to innate and adaptive immunity to fungal pathogens in vivo. J. Immunol. 172:3059-3069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bernstein, J. M., M. Ballow, P. M. Schlievert, G. Rich, C. Allen, and D. Dryja. 2003. A superantigen hypothesis for the pathogenesis of chronic hyperplastic sinusitis with massive nasal polyposis. Am. J. Rhinol. 17:321-326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bolard, F., P. Gosset, C. Lamblin, C. Bergoin, A. B. Tonnell, and B. Wallaert. 2001. Cell and cytokine profiles in nasal secretions from patients with nasal polyposis: effects of topical steroids and surgical treatment. Allergy 56:333-338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Claeys, S., T. de Belder, G. Holtappels, P. Gevaert, B. Verhasselt, P. van Cauwenberge, and C. Bachert. 2003. Human β-defensins and toll-like receptors in the upper airway. Allergy 58:748-753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hamilos, D. L., D. Y. Leung, D. P. Huston, A. Kamil, R. Wood, and Q. Hamid. 1998. GM-CSF, IL-5 and RANTES immunoreactivity and mRNA expression in chronic hyperplastic sinusitis with nasal polyposis (NP). Clin. Exp. Allergy 28:1145-1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hansel, T. T., I. J. De Vries, T. Iff, S. Rihs, M. Wandzilak, S. Betz, K. Blaser, and C. Walker. 1991. An improved immunomagnetic procedure for the isolation of highly purified human blood eosinophils. J. Immunol. Methods 145:105-110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Henriksson, G., K. M. Westrin, F. Karpati, A. C. Wikström, P. Stierna, and L. Hjelte. 2002. Nasal polyps in cystic fibrosis. Clinical endoscopic study with nasal lavage fluid analysis. Chest 121:40-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kauffman, H. F., and S. van der Heide. 2003. Exposure, sensitization, and mechanisms of fungus-induced asthma. Curr. Allergy Asthma Rep. 3:430-437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee, C. H., C. S. Rhee, and Y. G. Min. 1998. Cytokine gene expression in nasal polyps. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 107:665-670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lund, V. J. 1995. Fortnightly review: diagnosis and treatment of nasal polyps. BMJ 311:1411-1414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mambula, S. S., K. Sau, P. Henneke, D. T. Golenbock, and S. M. Levitz. 2002. Toll-like receptor (TLR) signaling in response to Aspergillus fumigatus. J. Biol. Chem. 277:39320-39326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marcella, R., A. Croce, A. Moretti, R. C. Barbacane, M. Di Giocchino, and P. Conti. 2003. Transcription and translation of the chemokines RANTES and MCP-1 in nasal polyps and mucosa in allergic and non-allergic rhinopathies. Immunol. Lett. 90:71-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McCurdy, J. D., T. J. Olynych, L. H. Maher, and J. S. Marshall. 2003. Cutting edge: distinct toll-like receptor 2 activators selectively induce different classes of mediator production from human mast cells. J. Immunol. 170:1625-1629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Min, Y. G., C. H. Lee, C. S. Rhee, K. H. Kim, C. S. Kim, Y. Y. Koh, K. U. Min, and P. L. Anderson. 1997. Inflammatory cytokine expression on nasal polyps developed in allergic and infectious rhinitis. Acta Otolaryngol. 117:302-306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Min, Y. G., and K. S. Lee. 2000. The role of cytokines in rhinosinusitis. J. Korean Med. Sci. 15:255-259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Murray, P. R., E. J. Baron, M. A. Pfaller, F. C. Tenover, and R. H. Yolken (ed.). 1999. Manual of clinical microbiology, 7th ed. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 22.Netea, M. G., A. Warris, J. W. Van der Meer, M. J. Fenton, T. J. Verver-Janssen, L. E. Jacobs, T. Andresen, P. E. Verweij, and B. J. Kullberg. 2003. Aspergillus fumigatus evades immune recognition during germination through loss of toll-like receptor-4-mediated signal transduction. J. Infect. Dis. 188:320-326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Norlander, T., M. Bronnegard, and P. Stierna. 1999. The relationship of nasal polyps, infection, and inflammation. Am. J. Rhinol. 13:349-355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Norlander, T., M. Fukami, K. M. Wetrin, P. Stierna, and B. Carsloo. 1993. Formation of mucosal polyps in the nasal and maxillary sinus cavities by infection. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 109:522-529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O'Neill, L. A. 2002. Toll-like receptor signal transduction and the tailoring of innate immunity: a role for Mal? Trends Immunol. 23:296-300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reiss, M. 1997. Current aspects of diagnosis and therapy of nasal polyposis. Wien. Klin. Wochenschr. 109:820-825. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Robinson, D. S., A. Tsicopoulos, Q. Meng, S. Durham, A. B. Kay, and Q. Hamid. 1996. Increased interleukin-10 messenger RNA expression in atopic allergy and asthma. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 14:113-117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roeder, A., C. J. Kirschning, R. A. Rupec, M. Schaller, and H. C. Korting. 2004. Toll-like receptors and innate antifungal responses. Trends Microbiol. 12:44-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Romani, L. 2004. Immunity to fungal infections. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 4:11-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Romani, L., F. Bistoni, R. Gaziano, S. Bozza, C. Montagnoli, K. Perruccio, L. Pitzurra, S. Bellocchio, A. Velardi, G. Rasi, P. Di Francesco, and E. Garaci. 2004. Thymosin alpha 1 activates dendritic cells for antifungal Th1 resistance through Toll-like receptor signaling. Blood 103:4232-4239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Seitz, M. 2003. Toll-like receptors: sensors of the innate immune system. Allergy 58:1247-1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Slavin, R. G. 1997. Nasal polyps and sinusitis. JAMA 278:1849-1854. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stierna, P. L. 1996. Nasal polyps: relationship to infection and inflammation. Allergy Asthma Proc. 17:251-257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang, J. E., A. Warris, E. A. Ellingsen, P. F. Jorgensen, T. H. Flo, T. Espevik, R. Solberg, P. E. Verweij, and A. O. Aasen. 2001. Involvement of CD14 and Toll-like receptors in activation of human monocytes by Aspergillus fumigatus hyphae. Infect. Immun. 69:2402-2406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weschta, M., D. Rimek, M. Formanek, D. Polzehl, and H. Riechelmann. 2003. Local production of Aspergillus fumigatus specific immunoglobulin E in nasal polyps. Laryngoscope 113:1798-1802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]