Abstract

In the past five decades, alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency has been the only known genetic cause of emphysema, yet it explains the genetics in only 1–2% of severe cases. Recently, mutations in telomerase genes were found to induce susceptibility to young-onset, severe, and familial emphysema at a frequency comparable to that of alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency. Telomerase mutation carriers with emphysema report a family history of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, and both lung phenotypes show autosomal dominant inheritance within families. The data so far point to a strong gene–environment interaction that determines the lung disease type. In never-smokers, pulmonary fibrosis predominates, while smokers, especially females, are at risk for developing emphysema alone or in combination with pulmonary fibrosis. The telomere-mediated emphysema phenotype appears to have clinically recognizable features that are distinct from alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency, and patients are prone to developing short telomere syndrome comorbidities that influence clinical outcomes. In animal models, telomere dysfunction causes alveolar epithelial stem cell senescence, which is sufficient to drive lung remodeling and recruit inflammation. Here, we review the implications of these discoveries for understanding emphysema biology as well as for patient care.

Keywords: aging, alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency, senescence, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, hepatopulmonary syndrome

Emphysema is estimated to affect three to four million individuals in the United States alone; it is a leading cause of disability and mortality worldwide (1–3). Therapies that reverse the airspace destruction characteristic of emphysema are lacking. In the vast majority of patients, cigarette smoke is the culprit, highlighting the importance of prevention efforts (1, 4). In some cases, even after minimal cigarette smoke exposure, severe emphysema develops at a young age, as early as the fifth decade (5, 6). Several pieces of evidence support a genetic etiology for these cases (7). For example, in addition to severe, young-onset disease, emphysema may cluster in families (5, 6). In familial cases, airspace destruction is frequently the predominant phenotype and occurs in the absence of significant airway obstruction, suggesting that emphysema may be a definable heritable trait that is separable from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (5–7). This article reviews the emerging role of telomerase and telomere abnormalities in driving emphysema susceptibility.

Alpha-1 Antitrypsin Deficiency Explains Only a Small Subset of Extreme Emphysema Phenotypes

Since Laurel and Eriksson published their landmark paper in 1963, and until recently, alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency has been the only known genetic cause of familial emphysema. It is estimated to explain the susceptibility in approximately 1–2% of severe cases (8). Mutations in the SERPINA1 gene cause abnormally low alpha-1 antitrypsin protein levels and an autosomal recessive form of emphysema (9). The pathogenesis of lung disease in these patients is attributed to protease–antiprotease imbalance, predominantly due to unchecked activity of neutrophil elastase, which is neutralized by alpha-1 antitrypsin (9). This imbalance, in turn, is thought to promote inflammation and airspace destruction. The protease–antiprotease imbalance paradigm has been at the heart of understanding emphysema biology over the past five decades (9, 10). It has given impetus to the idea that inflammation is a primary driver of cigarette smoke–induced emphysema, and as such it has focused therapeutic efforts on testing the role of antiinflammatory medications (10). However, the clinical benefit from this approach has been limited (4). In addition, because alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency explains only a small subset of patients with severe familial emphysema, other yet-to-be discovered factors have been hypothesized (7).

Telomere Shortening Causes Premature Aging Disease Phenotypes

Telomerase is the specialized enzyme that synthesizes telomeres onto chromosome ends (11, 12). Telomere length shortens with cell division, and abnormally short telomeres signal senescence and apoptosis (reviewed in Reference 13). The role of telomere maintenance defects in mediating age-related disease has become evident in recent years through studies of human telomerase mutation carriers (13). These individuals have abnormally short telomere length for their age (14), and develop a disease spectrum known as the short telomere syndromes (15). Among these phenotypes, lung disease, both idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) and emphysema, is most common, comprising an estimated 90% of short telomere syndrome presentations in adults (15, 16). Emphysema and pulmonary fibrosis cluster with other features of premature aging, including early graying, osteoporosis, liver disease, a predisposition to bone marrow failure, and infertility (15, 17). There is also an increased incidence of myelodysplastic syndrome and acute myeloid leukemia in patients with short telomere syndromes (18–20).

Telomerase and Telomere Gene Mutations Explain the Genetic Basis in One-Third of Families with Pulmonary Fibrosis

The role of telomerase genetics in familial lung disease came first from a study of a three-generation family that was found to carry a deleterious mutation in the telomerase reverse transcriptase gene, TERT (21). In this family, the IPF phenotype was most common (21). Mutations in TERT are now recognized to be the most prevalent cause of familial pulmonary fibrosis (16). To date, mutations in seven telomerase and telomere genes have been shown to cause familial lung disease; together, they explain one-third of the inheritance in familial pulmonary fibrosis. They include genes that encode the essential telomerase components: TERT, the catalytic component, and TR, the telomerase RNA (21–23). Three other genes when mutated disrupt TR stability, processing, and biogenesis: DKC1, PARN, and NAF1, respectively (24–27). Mutations in TINF2, a telomere-binding protein, cause telomere shortening via a dominant negative mechanism (28), while mutations in RTEL1, which encodes a DNA helicase, disturb telomere length through mechanisms that are still incompletely understood (29). Abnormally short telomere length is also constitutional in at least half of individuals with sporadic IPF (30, 31), suggesting that it is a pervasive contributor to disease risk, even beyond familial cases (30).

Although IPF was the first lung disease to be causally linked to telomerase mutations, the connection to emphysema risk was first documented in mouse models (32). Telomerase-null mice with short telomeres share features of the human disease such as bone marrow failure (13), but do not develop de novo lung disease (32). However, after chronic exposure to cigarette smoke, they develop airspace destruction that recapitulates all the hallmarks of emphysema (32). Concurrent with this observation, severe young-onset emphysema was reported in two sisters who carried a deleterious mutation in the TR gene (32). Both of them had been suspected to have alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency based on their extreme phenotype, but their protein levels were intact. These early observations suggested that telomerase mutations and short telomeres may cause susceptibility to cigarette smoke–induced emphysema in humans.

Telomerase Mutations Predispose to Severe, Young-Onset, and Familial Forms of Emphysema

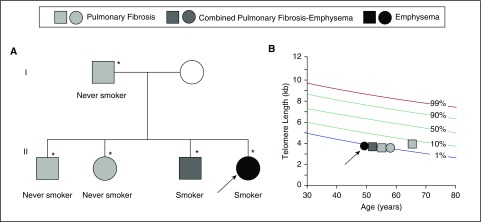

The prevalence of telomerase mutations in patients with early-onset severe emphysema was recently reported to be comparable to alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency across two cohorts (33). In the COPDGene and Lung Health Studies, the frequency of deleterious TERT mutations was 1% in severe, early-onset disease. Severe, early-onset disease was defined as Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) stage 3 and 4 that occurs in individuals younger than 65 years; the COPDGene study included additional radiographic criteria for emphysema (33). Some of the mutations had been previously reported in families with pulmonary fibrosis (33). To date, three telomerase genes—TERT, TR, and NAF1—have been linked to familial emphysema risk (26, 32, 33). Notably, the pedigrees of mutation carriers show that their relatives, who also carry mutations, have pulmonary fibrosis (Figure 1A) (33). A unique pattern emerges when examining the lung phenotypes closely. Within a single family, never-smokers develop pulmonary fibrosis, while mutation carriers who are smokers are at risk for emphysema (Figure 1) (33). This pattern highlights a unique gene–environment interaction in which the lung disease phenotype is determined by an environmental exposure in the presence of the genetically determined short telomere defect (Figure 1B). Notably, the gene–environment interaction seems to be particularly evident in females (33). Among the small series of patients with telomerase-associated emphysema heretofore reported, 90% are female even though the populations studied have been equally divided between males and females (33). Interestingly, this female predominance of severe disease among telomerase mutation carriers recapitulates a pattern previously documented in a Boston-based study of familial COPD in which 80% of probands younger than 53 years were female (6, 34). Importantly, the female-predominant susceptibility in telomerase mutation carriers contrasts with the predilection to disease manifesting earlier and more severely in men with alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency (35). Together, these observations suggest that pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema, in some cases, share a single genetic etiology, with the primary phenotype being highly influenced by environmental factors as well as sex differences (Figure 1) (33).

Figure 1.

Emphysema and pulmonary fibrosis show autosomal dominant inheritance in families with mutant telomerase–telomere genes. (A) Typical pedigree of a proband carrying a telomerase mutation who presents with early-onset emphysema (arrow). Her family history shows relatives with pulmonary fibrosis and combined pulmonary fibrosis–emphysema who also carry mutations (TERT, TR, or NAF1 mutations), as denoted by the asterisks. Squares refer to men and circles to women. The key above refers to the lung disease phenotype. (B) Telogram shows the telomere lengths of individuals in pedigree in A plotted relative to a normal distribution of telomere length with the percentiles as shown.

The Short Telomere–mediated Emphysema Phenotype May Be Clinically Recognizable

The heretofore published observations suggest that the telomere-mediated emphysema phenotype may also have clinically distinguishing features. Table 1 summarizes the distinguishing clinical and biological differences between the two known genetic forms of emphysema. For example, the airspace destruction in telomerase mutation carriers with emphysema has a predilection to the lung’s apex and is associated with an increased risk of pneumothorax (33). One-third of the reported telomerase mutation carriers with emphysema had a history of pneumothorax, a rate that is significantly higher rate than the overall rate for COPD (33) and that could reflect the apical predilection of their disease. Patients with emphysema with telomerase mutations, perhaps not surprisingly, also show short telomere syndrome features such as liver disease and bone marrow failure (26, 33). The emphysema arising in telomerase mutation carriers may thus represent a subphenotype that is clinically recognizable. Larger studies will be needed to define the natural history of this genetic form.

Table 1.

Comparison of emphysema caused by alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency and short telomeres

| Alpha-1 Antitrypsin Deficiency | Telomerase Deficiency and Telomere Shortening | |

|---|---|---|

| Inheritance | Autosomal recessive | Autosomal dominant |

| Disease gene(s) | SERPINA1 | TERT, TR, NAF1 |

| % of severe emphysema | 1–2% | 1% |

| Demographic | Male > female | Female > male |

| Lung disease pattern | Lower > upper lobe | Upper > lower lobe |

| Co-occurrence with IPF | No | Yes |

| Pneumothorax risk | Baseline | Increased |

| Link to aging biology | No | Yes |

| Mechanism | Protease–antiprotease imbalance, inflammation | Stem cell senescence, regenerative defect |

Definition of abbreviation: IPF = idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis.

Telomere Dysfunction Causes Alveolar Stem Cell Senescence

What are the mechanisms underlying the telomere-mediated lung disease phenotype? Studies in telomerase knockout mice suggest that abnormally short telomeres lower the threshold to genotoxic stress from cigarette smoke (32). Supporting this model, only telomerase-null mice with short telomeres develop emphysema, while telomerase-null mice with long telomeres are protected (32). The short telomere–dependent defect is intrinsic to the lung, as normal bone marrow cells transplanted before cigarette smoke exposure are not protective (32). The experimental data support a model of “two-hits,” in which the first is the genetically determined short telomere length and the second is an acquired cigarette smoke–induced damage (32, 36). The additive effect provokes the telomere-mediated emphysema phenotype.

One candidate cell type in which the additive damage accumulates in the alveolar space is the alveolar epithelial stem cell. In that milieu, at least a subset of type 2 alveolar epithelial cells (AEC2s) function as a facultative progenitor for new AEC2s as well as type 1 cells (37). The role of stem cell failure in lung disease susceptibility has been addressed experimentally (38). Co-culture experiments showed an AEC2-intrinsic regenerative defect in which only AEC2s with short telomeres, not mesenchymal cells, fail to support alveolar organoid formation. When telomere dysfunction is induced in vivo by deletion of the telomere-protective protein Trf2 specifically in AEC2s, the resultant DNA damage response induces senescence and consequent lung remodeling (38). Remarkably, the epithelial-derived DNA damage signal is sufficient to recruit macrophages and T cells, an inflammatory response that resembles what is seen in smokers and in patients with COPD (38). The current working model that synthesizes the findings of these studies is that short telomere–mediated stem cell senescence upregulates the expression of proinflammatory cytokines, which in turn drives inflammation (38). In effect, the inflammation in this form of emphysema is a secondary bystander caused by an upstream defect in stem cell senescence rather than a primary driver per se (38). Such a paradigm predicts a modest benefit for antiinflammatory approaches in subsets of patients in whom telomere shortening is the primary driver of disease.

Implications for Diagnostic and Patient Care Decisions

In addition to implications for emphysema biology, the link between telomerase and emphysema genetics has relevance for patient care, since mutation carriers have recurrent, well-described comorbidities. For example, patients with short telomere syndromes have an increased incidence of hepatopulmonary syndrome, which causes hypoxia because of intrapulmonary shunting (39). Distinguishing the etiology of dyspnea and hypoxia in patients with emphysema is obviously critical for interpreting pulmonary function studies and for assessing the severity of parenchymal lung disease (39). Patients with telomere-mediated lung disease are also sensitive to ionizing radiation and myelosuppressive medications (40, 41). In the lung transplant setting, telomerase mutation carriers have a higher rate of infectious complications, and almost invariably they require attenuation of immunosuppressive regimens because of their limited bone marrow reserves (41).

Beyond the immediate clinical implications, the genetic link between short telomeres and emphysema risk presents fundamental new considerations for the classification of lung disease. Although considered separate physiologic and radiographic clinical processes, the recent findings from our group highlight a single shared etiology for some cases of emphysema and pulmonary fibrosis. Rather than two entities, they may, in patients with short telomeres, represent manifestations of a single molecular process that diverges phenotypically because of environmental exposures and sex differences.

Finally, the link between telomere dysfunction and stem cell senescence provides a novel context within which to understand emphysema biology beyond alpha-1 antitryspin deficiency. Uniquely, this mechanism provides a causal link between disturbances in a biological mechanism well-established to promote cellular aging and emphysema risk. The significance of telomere shortening beyond the subset heretofore genetically identified remains to be determined. Since multiple genetic mechanisms influence telomere length, the full proportion of disease directly linked to telomere shortening may be greater than what early studies have so far estimated. The role beyond Mendelian genetic forms also needs to be assessed. A few studies have examined telomere length in populations of patients with COPD. They have consistently documented a reproducible shortening of telomere length in COPD, but the effect size was variable, and these studies did not examine extreme COPD phenotypes (42–45). The recent discoveries indicate that telomere shortening, within certain abnormal thresholds relative to healthy populations, plays a causal role in mediating susceptibility. Important for patient care paradigms and for future research in this area, the short telomere subphenotype is recognizable. Its pathogenesis is linked to a new paradigm of stem cell failure. However large the contribution of the short telomere mechanism will end up being in emphysema genetics, its discovery will undoubtedly facilitate the discovery of other yet-to-be identified subphenotypes within the heterogeneous entity of COPD.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Dr. Jonathan Alder for critical comments on this manuscript.

Footnotes

Supported by National Institutes of Health grants RO1 CA160433 (S.E.S. and M.A.), RO1 HL119476 (S.E.S. and M.A.), and T32 HL007534 (S.J.M.), and by the Commonwealth Foundation (S.E.S., S.J.M., and M.A.).

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org

References

- 1.Vestbo J, Hurd SS, Agusti AG, Jones PW, Vogelmeier C, Anzueto A, Barnes PJ, Fabbri LM, Martinez FJ, Nishimura M, et al. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, gold executive summary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;187:347–365. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201204-0596PP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xu J, Murphy SL, Kochanek KD, Bastian BA. Deaths: final data for 2013. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2016;64:1–119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Lung AssociationTrends in COPD (chronic bronchitis and emphysema): morbidity and mortality, 2013. [accessed 2016 Sep 15]. Available from: http://www.lung.org./assets/documents/research/copd-trend-report.pdf

- 4.Berry CE, Wise RA. Mortality in COPD: causes, risk factors, and prevention. COPD. 2010;7:375–382. doi: 10.3109/15412555.2010.510160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Foreman MG, Zhang L, Murphy J, Hansel NN, Make B, Hokanson JE, Washko G, Regan EA, Crapo JD, Silverman EK, et al. COPDGene Investigators. Early-onset chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is associated with female sex, maternal factors, and African American race in the COPDGene Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;184:414–420. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201011-1928OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Silverman EK, Chapman HA, Drazen JM, Weiss ST, Rosner B, Campbell EJ, O’Donnell WJ, Reilly JJ, Ginns L, Mentzer S, et al. Genetic epidemiology of severe, early-onset chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: risk to relatives for airflow obstruction and chronic bronchitis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;157:1770–1778. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.157.6.9706014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wan ES, Silverman EK. Genetics of COPD and emphysema. Chest. 2009;136:859–866. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-0555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rahaghi FF, Sandhaus RA, Brantly ML, Rouhani F, Campos MA, Strange C, Hogarth DK, Eden E, Stocks JM, Krowka MJ, et al. The prevalence of alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency among patients found to have airflow obstruction. COPD. 2012;9:352–358. doi: 10.3109/15412555.2012.669433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hatipoğlu U, Stoller JK. Alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency. Clin Chest Med. 2016;37:487–504. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2016.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cosio MG, Saetta M, Agusti A. Immunologic aspects of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:2445–2454. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0804752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Greider CW, Blackburn EH. Identification of a specific telomere terminal transferase activity in Tetrahymena extracts. Cell. 1985;43:405–413. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90170-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Greider CW, Blackburn EH. A telomeric sequence in the RNA of Tetrahymena telomerase required for telomere repeat synthesis. Nature. 1989;337:331–337. doi: 10.1038/337331a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Armanios M, Blackburn EH. The telomere syndromes. Nat Rev Genet. 2012;13:693–704. doi: 10.1038/nrg3246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mitchell JR, Wood E, Collins K. A telomerase component is defective in the human disease dyskeratosis congenita. Nature. 1999;402:551–555. doi: 10.1038/990141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stanley SE, Armanios M. The short and long telomere syndromes: paired paradigms for molecular medicine. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2015;33:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2015.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Armanios M. Telomerase and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Mutat Res. 2012;730:52–58. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2011.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Armanios M. Syndromes of telomere shortening. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2009;10:45–61. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genom-082908-150046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alter BP, Giri N, Savage SA, Rosenberg PS. Cancer in dyskeratosis congenita. Blood. 2009;113:6549–6557. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-12-192880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kirwan M, Vulliamy T, Marrone A, Walne AJ, Beswick R, Hillmen P, Kelly R, Stewart A, Bowen D, Schonland SO, et al. Defining the pathogenic role of telomerase mutations in myelodysplastic syndrome and acute myeloid leukemia. Hum Mutat. 2009;30:1567–1573. doi: 10.1002/humu.21115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parry EM, Alder JK, Qi X, Chen JJ, Armanios M. Syndrome complex of bone marrow failure and pulmonary fibrosis predicts germline defects in telomerase. Blood. 2011;117:5607–5611. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-11-322149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Armanios M, Chen JL, Chang YP, Brodsky RA, Hawkins A, Griffin CA, Eshleman JR, Cohen AR, Chakravarti A, Hamosh A, et al. Haploinsufficiency of telomerase reverse transcriptase leads to anticipation in autosomal dominant dyskeratosis congenita. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:15960–15964. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508124102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Armanios MY, Chen JJ, Cogan JD, Alder JK, Ingersoll RG, Markin C, Lawson WE, Xie M, Vulto I, Phillips JA, III, et al. Telomerase mutations in families with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1317–1326. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa066157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tsakiri KD, Cronkhite JT, Kuan PJ, Xing C, Raghu G, Weissler JC, Rosenblatt RL, Shay JW, Garcia CK. Adult-onset pulmonary fibrosis caused by mutations in telomerase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:7552–7557. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701009104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alder JK, Parry EM, Yegnasubramanian S, Wagner CL, Lieblich LM, Auerbach R, Auerbach AD, Wheelan SJ, Armanios M. Telomere phenotypes in females with heterozygous mutations in the dyskeratosis congenita 1 (DKC1) gene. Hum Mutat. 2013;34:1481–1485. doi: 10.1002/humu.22397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stuart BD, Choi J, Zaidi S, Xing C, Holohan B, Chen R, Choi M, Dharwadkar P, Torres F, Girod CE, et al. Exome sequencing links mutations in PARN and RTEL1 with familial pulmonary fibrosis and telomere shortening. Nat Genet. 2015;47:512–517. doi: 10.1038/ng.3278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stanley SE, Gable DL, Wagner CL, Carlile TM, Hanumanthu VS, Podlevsky JD, Khalil SE, DeZern AE, Rojas-Duran MF, Applegate CD, et al. Loss-of-function mutations in the RNA biogenesis factor NAF1 predispose to pulmonary fibrosis-emphysema. Sci Transl Med. 2016;8:351ra107. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaf7837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moon DH, Segal M, Boyraz B, Guinan E, Hofmann I, Cahan P, Tai AK, Agarwal S. Poly(A)-specific ribonuclease (PARN) mediates 3′-end maturation of the telomerase RNA component. Nat Genet. 2015;47:1482–1488. doi: 10.1038/ng.3423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alder JK, Stanley SE, Wagner CL, Hamilton M, Hanumanthu VS, Armanios M. Exome sequencing identifies mutant TINF2 in a family with pulmonary fibrosis. Chest. 2015;147:1361–1368. doi: 10.1378/chest.14-1947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cogan JD, Kropski JA, Zhao M, Mitchell DB, Rives L, Markin C, Garnett ET, Montgomery KH, Mason WR, McKean DF, et al. Rare variants in RTEL1 are associated with familial interstitial pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;191:646–655. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201408-1510OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alder JK, Chen JJ, Lancaster L, Danoff S, Su SC, Cogan JD, Vulto I, Xie M, Qi X, Tuder RM, et al. Short telomeres are a risk factor for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:13051–13056. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804280105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cronkhite JT, Xing C, Raghu G, Chin KM, Torres F, Rosenblatt RL, Garcia CK. Telomere shortening in familial and sporadic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;178:729–737. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200804-550OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alder JK, Guo N, Kembou F, Parry EM, Anderson CJ, Gorgy AI, Walsh MF, Sussan T, Biswal S, Mitzner W, et al. Telomere length is a determinant of emphysema susceptibility. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;184:904–912. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201103-0520OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stanley SE, Chen JJ, Podlevsky JD, Alder JK, Hansel NN, Mathias RA, Qi X, Rafaels NM, Wise RA, Silverman EK, et al. Telomerase mutations in smokers with severe emphysema. J Clin Invest. 2015;125:563–570. doi: 10.1172/JCI78554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Silverman EK, Weiss ST, Drazen JM, Chapman HA, Carey V, Campbell EJ, Denish P, Silverman RA, Celedon JC, Reilly JJ, et al. Gender-related differences in severe, early-onset chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;162:2152–2158. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.162.6.2003112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Demeo DL, Sandhaus RA, Barker AF, Brantly ML, Eden E, McElvaney NG, Rennard S, Burchard E, Stocks JM, Stoller JK, et al. Determinants of airflow obstruction in severe alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency. Thorax. 2007;62:806–813. doi: 10.1136/thx.2006.075846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Armanios M. Telomeres and age-related disease: how telomere biology informs clinical paradigms. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:996–1002. doi: 10.1172/JCI66370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Barkauskas CE, Cronce MJ, Rackley CR, Bowie EJ, Keene DR, Stripp BR, Randell SH, Noble PW, Hogan BL. Type 2 alveolar cells are stem cells in adult lung. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:3025–3036. doi: 10.1172/JCI68782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Alder JK, Barkauskas CE, Limjunyawong N, Stanley SE, Kembou F, Tuder RM, Hogan BL, Mitzner W, Armanios M. Telomere dysfunction causes alveolar stem cell failure. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:5099–5104. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1504780112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gorgy AI, Jonassaint NL, Stanley SE, Koteish A, DeZern AE, Walter JE, Sopha SC, Hamilton JP, Hoover-Fong J, Chen AR, et al. Hepatopulmonary syndrome is a frequent cause of dyspnea in the short telomere disorders. Chest. 2015;148:1019–1026. doi: 10.1378/chest.15-0825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stanley SE, Rao AD, Gable DL, McGrath-Morrow S, Armanios M. Radiation sensitivity and radiation necrosis in the short telomere syndromes. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2015;93:1115–1117. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2015.08.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Silhan LL, Shah PD, Chambers DC, Snyder LD, Riise GC, Wagner CL, Hellström-Lindberg E, Orens JB, Mewton JF, Danoff SK, et al. Lung transplantation in telomerase mutation carriers with pulmonary fibrosis. Eur Respir J. 2014;44:178–187. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00060014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Albrecht E, Sillanpää E, Karrasch S, Alves AC, Codd V, Hovatta I, Buxton JL, Nelson CP, Broer L, Hägg S, et al. Telomere length in circulating leukocytes is associated with lung function and disease. Eur Respir J. 2014;43:983–992. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00046213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rode L, Bojesen SE, Weischer M, Vestbo J, Nordestgaard BG. Short telomere length, lung function and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in 46,396 individuals. Thorax. 2013;68:429–435. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2012-202544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Savale L, Chaouat A, Bastuji-Garin S, Marcos E, Boyer L, Maitre B, Sarni M, Housset B, Weitzenblum E, Matrat M, et al. Shortened telomeres in circulating leukocytes of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;179:566–571. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200809-1398OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lee J, Sandford AJ, Connett JE, Yan J, Mui T, Li Y, Daley D, Anthonisen NR, Brooks-Wilson A, Man SF, et al. The relationship between telomere length and mortality in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) PLoS One. 2012;7:e35567. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]