Abstract

May–Thurner syndrome (MTS) is caused by venous occlusion because of compression of the iliac vein by the iliac artery and vertebral body, leading to left lower extremity deep venous thrombosis, eventually resulting in a series of symptoms. Endovascular treatment has now become the most preferred method of treatment of MTS.

The authors report a 66-year-old woman who was hospitalized because of increasing swelling in her left lower limb for almost 2 weeks. Ultrasonography performed upon admission indicated MTS, and venography revealed occlusion of the left common iliac vein and massive thrombosis in the left external iliac and femoral veins. The left lower extremity venous blood flow returned to normal after the patient underwent manual aspiration thrombectomy using a guide catheter, followed by balloon angioplasty and stent placement. The patient achieved complete remission after 1 week and had no in-stent restenosis during the 1-year follow-up.

Endovascular treatment is a safe and effective treatment of MTS.

INTRODUCTION

May–Thurner syndrome (MTS) refers to the complete or incomplete occlusion of the left common iliac vein because of compression by the overlying right common iliac artery and vertebral body. This results in the onset of corresponding symptoms, such as the swelling of the left lower limb, pain, and consecutive left lower extremity deep venous thrombosis.1–3 We discuss a case of MTS that was successfully treated with endovascular treatment.

CLINICAL REPORT AND TECHNIQUE DESCRIPTION

A 66-year-old woman was hospitalized because of increasing swelling of her left lower limb for almost 2 weeks. One-year prior, the patient had recurring swelling in her left lower limb for more than 1 month, with slow progression. The patient experienced increased swelling with occasional mild pain in the left lower limb upon standing or walking for a significant duration. The patient had no history of surgery or catheterization of the left femoral central vein. The patient experienced a significant increase in swelling of her left lower limb with pain for almost 2 weeks before admission. Upon admission, the patient's blood pressure was 120/65 mm Hg and heart rate was 85 bpm. Physical examination revealed that the patient's left lower limb was significantly swollen, the blood pressure of both lower limbs did not significantly differ, and the ankle–brachial indexes of the left and right lower limbs were similar. In addition, both the popliteal and dorsalis pedis arteries had a normal pulse. The deep tendon reflexes, strength, and sensation of the left lower limb were normal.

The results of the cardiac, thoracic, and abdominal examinations were normal. No obvious abnormalities were observed in the head, neck, and upper limbs. The patient's left lower limb was examined by using Doppler ultrasonography. The results suggest that the left common iliac vein was compressed by the iliac artery. The left common iliac, external iliac, and femoral veins were thickened, and intraluminal thrombus formation was observed.

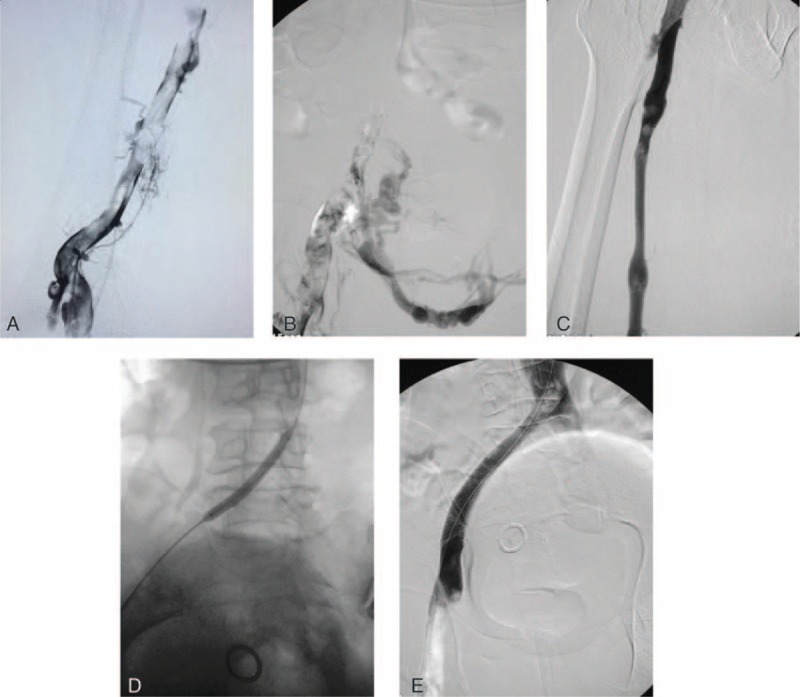

Written informed consent was obtained before the treatment. Local anesthesia was induced while the patient was in the prone position, after disinfection of the left popliteal area. The Seldinger technique was used to access the left popliteal vein and insert the 5-F vascular sheath, to perform venography through the sheath. Venography revealed the following: numerous irregular filling defects in the left popliteal, superficial femoral, and external iliac veins (Figure 1A); occlusion in the common iliac vein; numerous connections between the collateral vessels and contralateral iliac vein in the pelvis (Figure 1B); and backflow of contrast agent through the pelvic collateral veins from the right iliac vein. A guide wire and 5-F catheter (Radio Focus, Terumo, Japan) were used to pass through the occluded segment in the left common iliac vein. After venography ensured that the catheter was located in the inferior vena cava, the guide wire was retained and a 12-F/65-cm long sheath (Performer, Cook, Denmark) was inserted in the left common iliac vein. By using a 50-mL syringe, manual aspiration thrombectomy was performed repeatedly under vacuum, from the iliac vein proximal to the femoral vein, until venography revealed that blood flow in the left femoral and external iliac veins had been restored (Figure 1C). A 10/40-mm balloon catheter (Advance, Cook, Denmark) was inserted through the guide wire to dilate the occluded segment of the iliac vein for approximately 30 seconds (Figure 1D). Venography revealed that a small amount of thread-like blood was flowing through the vein and that the number of collateral vessels had been reduced. A 16/90-mm stent (Wallstent, Boston Scientific, Marlborough, MA) was inserted through the guide wire and released in the occluded segment of the common iliac vein, in which the distal end was positioned in the inferior vena cava whereas the proximal end was positioned in the external iliac vein. An approximately 30% residual stenosis was observed, and a 14/40-mm balloon (Advance, Cook, Denmark) was introduced to expand the in-stent restenosis segment again. Venography revealed that the condition of the stent was satisfactory, with good expansion and blood flow (Figure 1E). During the procedure, 4000-U heparin was intravenously injected as an anticoagulant, followed by 1000-U heparin every hour. The activated partial and complete activated thromboplastin times were closely monitored. After the procedure, the patient received a subcutaneous injection of 4000-IU q12h low-molecular weight heparin for 1 week. At the same time, the patient orally received warfarin. The warfarin dose was adjusted based on the international normalized ratio between 2.0 and 2.5. The patient achieved complete remission after 1 week, at which time the swelling in the left lower limb had disappeared. The patient was reexamined after 6 months and again after 1 year by using Doppler ultrasonography. The results suggest that the blood flow in the stent and that in the left lower limb vein were smooth without any significant thrombosis.

FIGURE 1.

A, Initial venography in the prone position shows femoral vein thrombosis. B, A venography shows occlusion of the common iliac vein and collateral formation. C, The venography shows a patent common femoral vein and little residual thrombus was shown after manual aspiration thrombectomy. D, The common iliac vein was dilated with an angioplasty balloon. E, A venography after stent deployment shows a patent common iliac vein, good antegrade flow, and abolition of collaterals.

DISCUSSION

The main conventional treatments of MTS are iliac vein adhesiolysis, endovascular synthetic stent grafting, anastomosis after transection of the right iliac artery from the left common iliac vein and resection of the involved segment of the iliac vein, and in situ vascular grafting. These surgical methods, however, cause serious trauma with unsatisfactory long-term efficacy, which are unacceptable for patients.1,2,4

Several imaging modalities are useful in MTS diagnosis. Color Doppler ultrasonography is the first-line method used to scan patients with common iliac vein disorders and can detect deep vein thrombosis.5 The technique, however, cannot accurately identify venous spurs or compression of the vein. If MTS is suspected in patients subjected to ultrasonography, computed tomography venography (CTV) or magnetic resonance angiography (MRV) should be used to accurately visualize the pelvic region. Computed tomography venography and MRV provides a relatively noninvasive imaging tool to diagnose and evaluate the severity of venous insufficiency. A CTV or MRV image not only shows the offending overlying artery but can also show the presence of any other extrinsic compressions.1,2 Although CTV or MRV depicts the details of anatomic structures, the intraluminal septation that may disturb venous flow is not easily seen because of limitations in the imaging resolution. The gold standard for detecting MTS and planning therapeutic interventions is digital subtraction venography.2,6 Digital subtraction venography obtained via femoral access can demonstrate the compression itself and the presence of tortuous venous collaterals crossing the pelvis to join contralateral veins.

Endovascular treatment has been proven to be a feasible and effective method for treating MTS, a technique that mainly uses catheter-directed thrombolysis or balloon angioplasty and stenting.2,6–8 Compared with anticoagulation therapy, catheter-directed thrombolysis can more effectively remove the thrombus and improve symptoms. Local infusion of thrombolytic drugs also reduces the risk of bleeding. Balloon angioplasty is rarely used alone and often used in combination with stenting, especially in patients with chronic MTS. Balloon angioplasty procedures lacking subsequent stent placement have been associated with low patency rates. A 73% recurrence rate was noted in patients with acute left-sided ilio-femora deep vein thrombosis when the underlying obstruction was not treated via stent placement.9 Thus, MTS treatment almost always features the placement of stents exhibiting high radical force. When compared with balloon angioplasty, stenting is a more effective treatment of venous obstruction. O'Sullivan et al10 reported the use of endovascular treatment in 39 patients with MTS, of whom 87% were treated successfully. The 1-year patency rate of endovascular stenting in the patients with acute vascular occlusion was 91.6%, and the symptoms in 85% of the patients were fully or partially improved from their state before the treatment. The 5-year patency rate of the iliac vein has been reported to be as high as 80%.11,12

In the current case, the patient had acute swelling with fresh thrombi for 2 weeks, which shows that the manual aspiration thrombectomy under vacuum by using a 12-F lumen catheter was effective. Although some old thrombi were difficult to remove, most of the thrombi were cleared. Furthermore, mural thrombi do not affect the bloodstream and do not detach easily. Vacuum aspiration can and should be performed repeatedly, in which the catheter carrying the thrombi is removed and inserted again for another aspiration. We are considering improving the large lumen catheter and syringe, especially the adapter diameter of the syringe and catheter, where a syringe with a large diameter can be designed to fit in the large lumen catheter. Hence, repeated catheter removal and reinsertion are no longer needed, which can greatly shorten the surgical and radiation exposure times.

Our study shows that endovascular treatment is a feasible and safe treatment of MTS and can significantly improve the symptoms of patients.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: CDT = catheter-directed thrombolysis, CDU = color Doppler ultrasonography, CTV = computed tomography venography, DSV = digital subtraction venography, DVT = deep vein thrombosis, MRV = magnetic resonance angiography, MTS = May–Thurner syndrome.

The authors have no funding and conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mousa AY, AbuRahma AF. May-Thurner syndrome: update and review. Ann Vasc Surg 2013; 27:984–995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brazeau NF, Harvey HB, Pinto EG, et al. May-Thurner syndrome: diagnosis and management. Vasa 2013; 42:96–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Donatella N, Marcello BU, Gaetano V, et al. What the young physician should know about May-Thurner syndrome. Transl Med UniSa 2015; 12:19–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Igari K, Kudo T, Toyofuku T, et al. Surgical thrombectomy and simultaneous stenting for deep venous thrombosis caused by iliac vein compression syndrome (May-Thurner syndrome). Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2014; 20:995–1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shebel ND, Whalen CC. Diagnosis and management of iliac vein compression syndrome. J Vasc Nurs 2005; 23:10–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ibrahim W, Al Safran Z, Hasan H, et al. Endovascular management of May-Thurner syndrome. Ann Vasc Dis 2012; 5:217–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bozkaya H, Cinar C, Ertugay S, et al. Endovascular treatment of iliac vein compression (May-Thurner) syndrome: angioplasty and stenting with or without manual aspiration thrombectomy and catheter-directed thrombolysis. Ann Vasc Dis 2015; 8:21–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Budnur SC, Singh B, Mahadevappa NC, et al. Endovascular treatment of iliac vein compression syndrome (May-Thurner). Cardiovasc Interv Ther 2013; 28:101–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mickley V, Schwagierek R, Rilinger N, et al. Left iliac venous thrombosis caused by venous spur: treatment with thrombectomy and stent implantation. J Vasc Surg 1998; 28:492–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O'Sullivan GJ, Semba CP, Bittner CA, et al. Endovascular management of iliac vein compression (May-Thurner) syndrome. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2000; 11:823–836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hood DB, Alexander JQ. Endovascular management of iliofemoral venous occlusive disease. Surg Clin North Am 2004; 84:1381–1396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kolbel T, Lindh M, Akesson M, et al. Chronic iliac vein occlusion: midterm results of endovascular recanalization. J Endovasc Ther 2009; 16:483–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]