Abstract

Skull-base metastasis (SBM) from hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is extremely rare, and multiple cranial nerve paralysis due to SBM from HCC is also rare. We report a case of bulbar and facial paralysis due to SBM from HCC.

A 46-year-old Chinese man presented with a hepatic right lobe lesion that was detected during a routine physical examination. After several failed attempts to treat the primary tumor and bone metastases, neurological examination revealed left VII, IX, X, and XI cranial nerve paralysis. Computed tomography of the skull base subsequently revealed a large mass that had destroyed the left occipital and temporal bones and invaded the adjacent structure. After radiotherapy (27 Gy, 9 fractions), the patient experienced relief from his pain, and the cranial nerve dysfunction regressed. However, the patient ultimately died, due to the tumor's progression.

Radiotherapy is usually the best option to relieve pain and achieve regression of cranial nerve dysfunction in cases of SBM from HCC, although early treatment is needed to achieve optimal outcomes. The present case helps expand our understanding regarding this rare metastatic pathway and indicates that improved awareness of SBM in clinical practice can help facilitate timely and appropriate treatment.

INTRODUCTION

Prostate cancer (38%) and breast cancer (20%) are the most common malignancies that result in skull-base metastasis (SBM).1 In contrast, SBM from hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is an exceedingly rare condition. Therefore, we report a case of SBM from HCC, with the detailed clinical course, treatment strategies, and outcome. We also review the related literature to summarize the typical clinical presentation, diagnosis, and intervention options for SBM. This report may improve awareness regarding this unique metastasis, and improved awareness and early treatment are needed to improve clinical outcomes.

CASE REPORT

Approval from our institutional ethics review board was not required for this case report. However, the patient provided written informed consent for the publication of this case report and the accompanying images.

A 46-year-old Chinese man presented at our hospital in July 2009, due to the detection of a hepatic right lobe lesion during a routine physical examination (May 2009). However, the patient reported not experiencing any discomfort. He had a >20-year history of hepatitis B viral infection and alcohol abuse, and a family history of liver disease. His sister had undergone liver transplant due to cirrhosis in 2006, and his 2 brothers had HCC.

Laboratory testing revealed slightly elevated gamma glutamyltransferase (γ-GGT) levels (84 U/L) and normal coagulation function. His hepatitis B surface antigen levels were >250 IU/mL, his hepatitis B envelop antigen levels were 3.111 S/CO, and his core antibody levels were 16.610 S/CO. Additional testing revealed hepatitis B viral DNA levels of 2.56 × 106 copies/mL, and his serum alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) levels were 759.1 ng/mL. Contrast-enhanced abdominal computed tomography (CT) revealed a 24 mm × 18 mm lesion in the right lobe of the liver with typical radiologic manifestation of HCC. Therefore, the patient underwent radiofrequency ablation for the hepatic lesion on July 10, 2009, and was subsequently treated using entecavir.

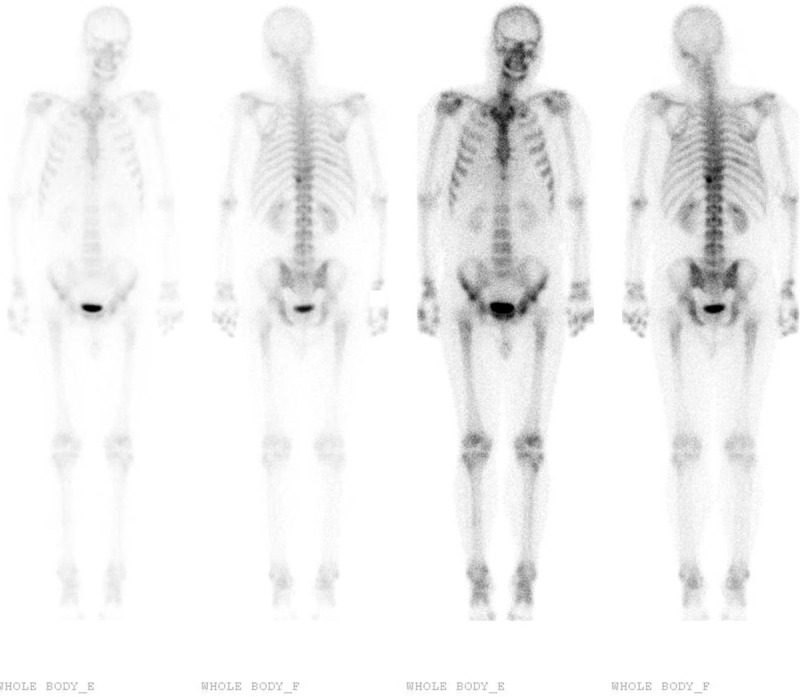

However, the patient experienced relapse in the tumor bed, and subsequently underwent 2 additional rounds of radiofrequency ablation. Unfortunately, the tumor aggressively progressed, and contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging of the liver in May 2010 revealed multiple cancerous nodules in the cirrhotic right and left lobes. The patient also exhibited elevated AFP levels (1116 ng/mL). Therefore, he underwent 2 rounds of transarterial chemoembolization with chemotherapy (20 mg of epirubicin, 4 mg of mitomycin, 100 mg of tegafur, and 30 mg of hydroxycamptothecin), although these did not slow down the tumor's progression. In November 2010, the patient experienced left peripheral facial paralysis and backache, and liver function testing revealed multiple abnormal findings (alkaline phosphatase: 210 U/L, aspartate aminotransferase: 111 U/L, alanine aminotransferase: 69 U/L, and γ-GGT: 540 U/L). The patient's AFP levels had increased to 60,500 ng/mL, and his hepatitis B viral DNA levels were 2.02 × 104 copies/mL. Bone scanning revealed metastases in the ninth and tenth thoracic vertebrae and in the eighth right posterior rib (Figure 1), and CT revealed destruction of the ninth and tenth thoracic vertebrae (Figure 2). Therefore, the patient underwent palliative radiotherapy (RT; 30 Gy, 10 fractions) for the metastases in the ninth and tenth thoracic vertebrae, and he reported that his backache was relieved.

FIGURE 1.

Bone scanning reveals increased radioactivity in the ninth and tenth thoracic vertebrae and in the eighth right posterior rib. No abnormal activity was observed in the left occipital and temporal bones.

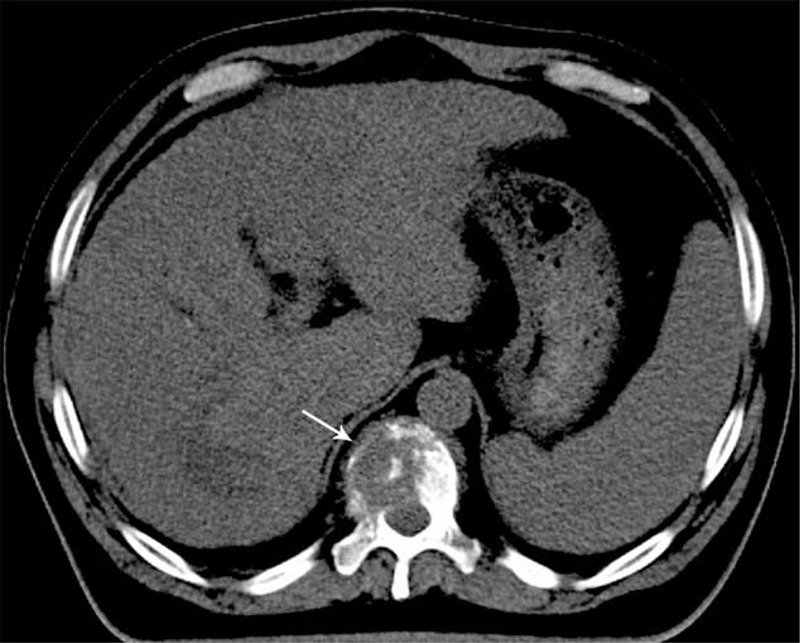

FIGURE 2.

Computed tomography reveals destruction of the tenth thoracic vertebra (the tenth thoracic level).

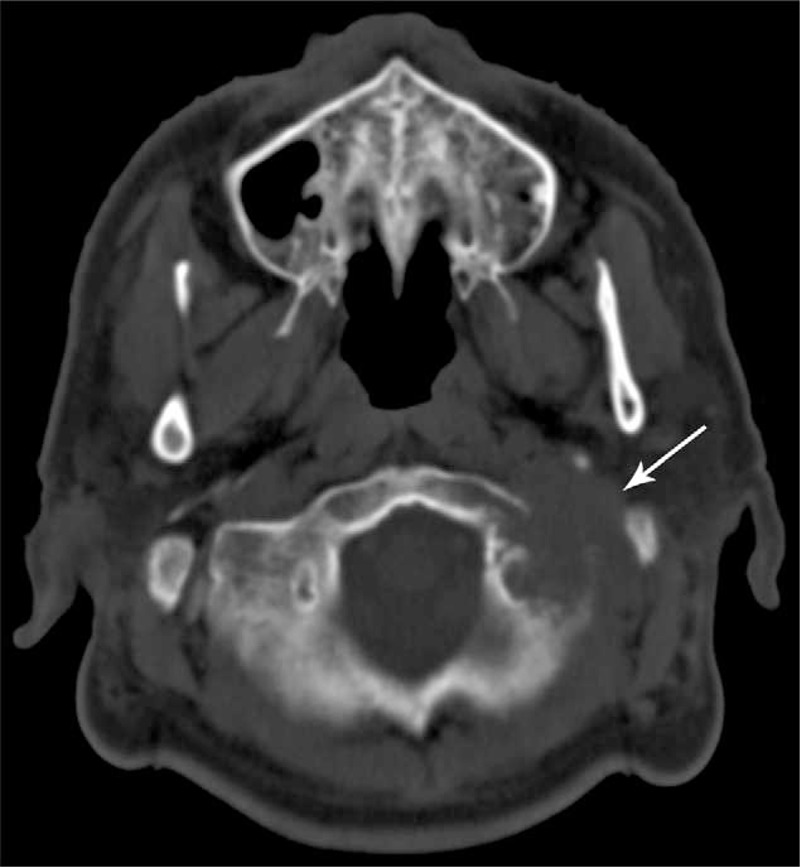

Unfortunately, the patient subsequently experienced throat tightness, dysphagia, and left-sided headache. Our neurological examination revealed left VII, IX, X, and XI cranial nerve paralysis, and CT of the skull base revealed a large mass that had destroyed the left occipital and temporal bones and invaded the adjacent structure (Figure 3). Given the patient's poor general condition, the SBM was treated using RT (27 Gy, 9 fractions), which relieved his headache. However, the patient ultimately died in January 2011, due to the tumor's progression.

FIGURE 3.

Computed tomography of the skull base reveals a large mass that destroyed the left occipital and temporal bones and invaded the adjacent structure.

DISCUSSION

HCC is one of the most lethal cancers throughout the world and is especially lethal in Asia and Africa, where the burden of chronic hepatitis B viral infection is overwhelming.2 In the past, the dismal survival rates for patients with HCC have resulted in low incidences of symptomatic extrahepatic metastases, such as lung and bone metastases (0–5%).3,4 However, recent improvements in the overall survival of patients with HCC has increased the likelihood that metastasis will be observed in these patients. For example, Fukutomi et al have reported that the incidence of bone metastasis from HCC increased to 13% and that the most commonly involved sites were the vertebra, pelvis, rib, and skull.5 Furthermore, the characteristic radiological features of bone metastases from HCC are expansive lesions with soft-tissue masses.6,7 However, SBM from HCC are rarely encountered in clinical practice, with reported incidences are 0.4% to 1.6%,6,8,9,10 and the most common clinical manifestations are pain and related cranial nerve palsies.6 Rades et al have reported that 96% of SBM cases from HCC experienced different cranial nerve deficits that were dependent on the involved cranial nerves.6,11 Laigle-Donadey et al have also summarized 5 syndromes of cranial nerve deficits, which include the orbital, parasellar, middle-fossa, jugular foramen, and occipital condyle syndromes.1 The present case exhibited both middle-fossa and jugular foramen syndromes, which were relatively uncommon (6% and 3.5%, respectively) in Laigle-Donadey et al's series.1 Therefore, careful examinations should be performed to detect other osseous metastases, as a solitary SBM is exceedingly rare in cases of HCC.6,11 In addition, liver dysfunction and coagulopathy due to the HCC might result in bleeding from the SBM,12 and Woo et al have described an acute spontaneous epidural hematoma that was due to SBM from HCC.12 Unfortunately, acute-onset and heavy intracranial hemorrhage is difficult to control and can lead to death.

In addition to the characteristic clinical manifestations, radiological findings can play a critical role in the diagnosis of SBM. In this context, magnetic resonance imaging is generally more sensitive for detecting metastatic soft tissue masses, especially when the fat suppression technique and gadolinium infusion are used.1 In contrast, skull-base CT with bone windows is the best technique for detecting osteolytic lesions,1,13 and skull-base CT clearly revealed the extent of the SBM in the present case.

Treatment of SBM from HCC presents a multidisciplinary challenge and should be customized according to the patient's general condition, tumor burden, and SBM site. As the presence of SBM usually indicates a late-stage tumor, palliative RT is frequently performed to relieve pain and improve neurological outcomes. A retrospective study by Dröge et al revealed that external beam RT with a mean dose of 31.6 Gy could provide a response rate of 81.1% and relatively mild side effects.14 However, the effects of RT are attenuated if RT initiation is delayed, as cases with symptom durations of <1 month, 1 to 3 months, and >3 months achieved RT response rates of 87%, 69%, and 25%, respectively.15 Therefore, it is essential to quickly recognize the presence of an SBM and to provide timely RT. The total dose and fraction vary for each case, although 35 Gy (14 fractions) are recommended because this treatment has good tolerance.16 However, patients with a limited tumor and who are expected to experience prolonged survival may receive doses as high as 50 Gy (25 fractions).16 Furthermore, Iwai et al have demonstrated that Gamma Knife radiosurgery was a useful treatment for SBM, as either a primary intervention or as secondary management for recurrence after previous RT.17 Unfortunately, surgery has very limited usefulness for SBM management and is reserved for carefully selected cases with a worsening disfiguring mass, cases with neurological deficit, cases that are difficult to diagnose,18 and cases with a solitary metastasis.16

The present case involved several limitations and useful lessons that should be considered to improve the outcomes in similar cases. It appears that bone scanning is only sensitive for osteoblastic lesions, rather than osteolytic lesions, as it only detected the metastases in the ninth and tenth thoracic vertebrae and the eighth right posterior rib, but failed to detect the metastases in the left occipital and temporal bones. Because the metastases in the left occipital and temporal bones were osteolytic, their presence was only detected when we performed a later skull-base CT scan. Thus, we were not aware of the possibility of SBM from HCC and should not have relied solely on the findings from the bone scan. Therefore, if a patient exhibits left peripheral facial paralysis, physicians should immediately perform a neurological examination and skull-base CT, in order to reach a timely diagnosis and provide appropriate treatment. If we have diagnosed the SBM at an earlier stage in the present case and had provided RT for the SBM, it is possible that we could have achieved greater cranial nerve dysfunction regression, as delayed RT initiation can reduce the clinical effect of this treatment.

CONCLUSION

We report an extremely rare case of SBM from HCC. Although RT can effectively relieve the patient's symptoms and improve their quality of life, it is important to consider this uncommon metastasis and to provide early and appropriate intervention, in order to achieve the optimal response to RT.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: γ-GGT = gamma glutamyltransferase, AFP = alpha-fetoprotein, HCC = hepatocellular carcinoma, RT = radiotherapy, SBM = skull-base metastasis.

ML, SL, and BL contributed equally to this study.

Funding: this report was supported by the Science and Technology Department of Jilin Province (grant no: 3D512J233428), the Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no: 81272999, 81372929), the First Hospital of Jilin University (grant no: JDYY52015004, JDYY52015012), and the Traditional Chinese Medicine Administration Bureau of Jilin Province (grant no: 2014-Q54).

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Laigle-Donadey F, Taillibert S, Martin-Duverneuil N, et al. Skull-base metastases. J Neurooncol 2005; 75:63–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benson AB, 3rd, Abrams TA, Ben-Josef E, et al. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: hepatobiliary cancers. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2009; 7:350–391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Okuda K. Okuda K, Peter RL. Clinical aspects of hepatocellular carcinoma: analysis of 134 cases. Hepatocellular Carcinoma. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1976; 387-436. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee YT, Geer DA. Primary liver cancer: pattern of metastasis. J Surg Oncol 1987; 36:26–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fukutomi M, Yokota M, Chuman H, et al. Increased incidence of bone metastases in hepatocellular carcinoma. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2001; 13:1083–1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hayashi S, Tanaka H, Hoshi H. Palliative external-beam radiotherapy for bone metastases from hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Hepatol 2014; 6:923–929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kuhlman JE, Fishman EK, Leichner PK, et al. Skeletal metastases from hepatoma: frequency, distribution, and radiographic features. Radiology 1986; 160:175–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hsieh CT, Sun JM, Tsai WC, et al. Skull metastasis from hepatocellular carcinoma. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2007; 149:185–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Trivedi P, Gupta A, Pasricha S, et al. Isolated skull base metastasis as the first manifestation of hepatocellular carcinoma—a rare case report with review of literature. J Gastrointest Cancer 2009; 40:10–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nozaki I, Tsukada T, Nakamura Y, et al. Multiple skull metastases from hepatocellular carcinoma successfully treated with radiotherapy. Intern Med 2010; 49:2631–2634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rades D, Stalpers LJ, Veninga T, et al. Evaluation of five radiation schedules and prognostic factors for metastatic spinal cord compression. J Clin Oncol 2005; 23:3366–3375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Woo KM, Kim BC, Cho KT, et al. Spontaneous epidural hematoma from skull base metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Korean Neurosurg Soc 2010; 47:461–463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Post MJ, Mendez DR, Kline LB, et al. Metastatic disease to the cavernous sinus: clinical syndrome and CT diagnosis. J Comput Assist Tomogr 1985; 9:115–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dröge LH, Hinsche T, Canis M, et al. Fractionated external beam radiotherapy of skull base metastases with cranial nerve involvement. Strahlenther Onkol 2014; 190:199–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vikram B, Chu FC. Radiation therapy for metastases to the base of the skull. Radiology 1979; 130:465–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chamoun RB, DeMonte F. Management of skull base metastases. Neurosurg Clin N Am 2011; 22:61–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Iwai Y, Yamanaka K. Gamma Knife radiosurgery for skull base metastasis and invasion. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg 1999; 72 Suppl 1:81–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chamoun RB, Suki D, DeMonte F. Surgical management of cranial base metastases. Neurosurgery 2012; 70:802–810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]