Summary

Background

Assisted partner services for index patients with HIV infections involves elicitation of information about sex partners and contacting them to ensure that they test for HIV and link to care. Assisted partner services are not widely available in Africa. We aimed to establish whether or not assisted partner services increase HIV testing, diagnoses, and linkage to care among sex partners of people with HIV infections in Kenya.

Methods

In this cluster randomised controlled trial, we recruited non-pregnant adults aged at least 18 years with newly or recently diagnosed HIV without a recent history of intimate partner violence who had not yet or had only recently linked to HIV care from 18 HIV testing services clinics in Kenya. Consenting sites in Kenya were randomly assigned (1:1) by the study statistician (restricted randomisation; balanced distribution in terms of county and proximity to a city) to immediate versus delayed assisted partner services. Primary outcomes were the number of partners tested for HIV, the number who tested HIV positive, and the number enrolled in HIV care, in those who were interviewed at 6 week follow-up. Participants within each cluster were masked to treatment allocation because participants within each cluster received the same intervention. This trial is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov, number NCT01616420.

Findings

Between Aug 12, 2013, and Aug 31, 2015, we randomly allocated 18 clusters to immediate and delayed HIV assisted partner services (nine in each group), enrolling 1305 participants: 625 (48%) in the immediate group and 680 (52%) in the delayed group. 6 weeks after enrolment of index patients, 392 (67%) of 586 partners had tested for HIV in the immediate group and 85 (13%) of 680 had tested in the delayed group (incidence rate ratio 4·8, 95% CI 3·7–6·4). 136 (23%) partners had new HIV diagnoses in the immediate group compared with 28 (4%) in the delayed group (5·0, 3·2–7·9) and 88 (15%) versus 19 (3%) were newly enrolled in care (4·4, 2·6–7·4). Assisted partner services did not increase intimate partner violence (one intimate partner violence event related to partner notification or study procedures occurred in each group).

Interpretation

Assisted partner services are safe and increase HIV testing and case-finding; implementation at the population level could enhance linkage to care and antiretroviral therapy initiation and substantially decrease HIV transmission.

Funding

National Institutes of Health.

Introduction

Public health departments in the USA and some European countries routinely provide assisted partner services to people with newly diagnosed HIV infections.1–3 These services typically involve having a trained professional interview people with HIV to identify their sex partners and then having the professional contact the partners who have been identified with the goal of ensuring that they test for HIV and, if infected, link to medical care. Such services have not been widely implemented in Africa, and few data exist for the effectiveness and feasibility of their provision in primary health-care settings.

effective assisted partner services can decrease HIV transmission by increasing HIV testing among exposed partners, reducing ongoing HIV exposure in people in HIV-discordant relationships, and assuring prompt linkage to care and initiation of antiretroviral therapy (ART) among infected people.4,5 The potential effect of assisted partner services would be greatest in sub-Saharan Africa where HIV is endemic and HIV testing and ART coverage are low.6 Although substantial expansion of HIV testing has been reported in Africa, 28·4% of Kenyan adults report never having been tested in the most recent national AIDS indicator survey (Kenya AIDS Indicator Survey), and only about 10% of adults in Uganda and Nigeria report testing within the preceding year.7,8 Efforts are needed throughout sub-Saharan Africa to identify people with undiagnosed HIV infections, and traditional approaches to HIV testing services, such as voluntary counselling and testing, fail to reach many infected people. Mobile, home-based, and expanded provider-initiated testing might all improve testing coverage; however, scalable and targeted new approaches for identification of people with undiagnosed HIV infections and linkage to care are needed if 90% of adults with HIV infections are to learn their status, as promoted by the Joint UN Programme on HIV/AIDS.9

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

We reviewed published literature up to June 10, 2016, through searches of PubMed (restricted to the English language) and used the search terms “contact tracing”, “partner notification”, “partner services”, “HIV”, and “randomized trials”. Little evidence existed for the feasibility and effectiveness of assisted partner services, including partner notification for HIV.

Three decades ago, a small trial in the USA showed that partner notification was efficacious and this finding formed the basis for the adoption of partner notification as a routine public health practice in the USA and Europe. Data from Malawi indicate that provider referral is better than patient referral in increasing rates of HIV testing among sexual partners.

Programme data from Cameroon also showed that partner services are effective, without increasing the risk of intimate partner violence (IPV). None of these studies used pragmatic study designs; all were small and did not explore first-time HIV testing and linkage to care for sexual partners with HIV infections. IPV also needed further assessment. Perhaps because of an absence of data from real-world settings and for social harms, clinical practice for HIV case finding in Africa has not changed and does not include sexual partner elicitation, HIV testing, and linkage to care of infected sexual partners.

Added value of this study

This study was larger than were previous trials and enhances the body of evidence supporting use of assisted partner services, especially in Africa. In combination with previously published and presented data, we provide evidence that assisted partner services are effective and acceptable public health interventions that need to be brought to scale in low-income and middle-income countries. The pragmatic design of our trial, the broad eligibility criteria for index patient enrolment, and the diverse clinical setting in which the trial occurred could enhance adoption of partner services in sub-Saharan Africa.

Implications of all the available evidence

The consistency of our results with findings from previous studies in the USA and Africa suggest assisted partner services are feasible in sub-Saharan Africa and require urgent policy action. Future research should now focus on implementation of partner services. Given the high prevalence of lifetime IPV in east Africa and other regions hit hard by the HIV epidemic, introduction of a partner services programme warrants close monitoring. Our findings could potentially influence HIV testing approaches globally and accelerate achievement of universal knowledge of HIV status.

Existing data suggest that assisted partner services are both efficacious and effective. Investigators of a small individually randomised trial10 done in the USA in the early 1990s found that assisted partner services increase partner testing. Findings from two randomised trials11,12 done in Malawi showed that assisted partner services were efficacious, whereas observational programme data13 from Cameroon indicate that they can be brought to scale in a resource-limited setting. Despite this increasing body of evidence, assisted partner services are not widely used in the parts of the world where HIV is most prevalent, and international guidelines have yet to endorse the intervention. Additional data showing scalability and effectiveness of assisted partner services in routine and diverse health-care settings are needed. Furthermore, previous individually randomised trials were prone to contamination, indicating the need for a cluster-randomised design.

We report the safety and effectiveness of assisted partner services among individuals testing HIV positive at 18 rural and urban Kenyan HIV testing services sites and who reported no recent intimate partner violence (IPV) in improving HIV testing, first-time testing, case-finding, and linkage to HIV care for their sex partners. We also assessed the number of index patients who would need to receive assisted partner services to achieve each of these outcomes relative to standard-ofcare counselling.

Methods

Study design and participants

In this cluster-randomised controlled trial, we sought administrative approval before randomisation in each of the 18 clusters. These clusters were HIV testing service clinics located within public sector or faith-based health facilities. 11 clusters were located in central Kenya (including Nairobi, the capital city) and seven were located in western Kenya. Cluster eligibility captured geographical diversity, rural and urban location, and regional differences in HIV prevalence. Clinic staff referred index participants with HIV infections to health advisors for screening and enrolment. Health advisors were nurses and medical assistants with experience in HIV testing and community tracing.

HIV prevalence in each cluster varied from 4% to 14% and numbers of HIV cases identified per month ranged from three to 218. We deemed potential participants (index participants) eligible if they were at least 18 years of age, not pregnant, willing to provide consent and sex partner information, newly or recently diagnosed with HIV, had not yet linked to HIV care or had linked to care within the preceding 6 weeks, and reported no IPV in the preceding month. We classified study participants as at a moderate risk of IPV if they reported a history of IPV during their lifetime, either from a present or past partner, or feared IPV if they participated in the study. These participants could be eligible for study participation and, if enrolled, received special monitoring. We excluded those who lived outside a 50 km radius from the study site. We counselled people who declined study participation during post-test HIV counselling to disclose their HIV status to sex partners, as per the standard of care in Kenya. The study was approved by the Kenyatta National Hospital Ethics Review Committee and the University of Washington Institutional Review Board. We obtained written informed consent in either English or Kiswahili depending on the language that the study participants preferred. The study protocol has been previously published.14

Randomisation and masking

The study biostatistician (BAR) used restricted randomisation to assign the 18 sites (1:1) into immediate or delayed assisted partner services to ensure balanced distribution between treatment groups of site-level characteristics (county [Nairobi, Kiambu, Muranǵa, Kisumu, and Siaya] and proximity to a city [urban, periurban, and rural). The randomisation process generated 3360 possible ways to allocate nine sites to each study group, one of which was chosen with a random number generator. The health advisors who collected the data, the health workers who referred index participants to the study, and the investigators who analysed the data were not masked to treatment allocation. Participants within each cluster were masked to treatment allocation because all participants within each cluster received the same intervention.

Procedures

After informed consent and enrolment, study staff interviewed participants. The baseline interview elicited participants’ demographic characteristics, HIV testing history, and sexual behaviours, and included questions designed to enumerate and identify each of the participant’s sex partners in the preceding 3 years. Specifically, study staff asked index participants to provide partners’ names, phone numbers, and home and work addresses, as well as information about their relationship.

In both study groups (delayed and immediate), health advisors encouraged index participants to notify their sex partners of their HIV-positive status as per the standard of care in Kenya. However, in the delayed group, they did not provide any additional support to promote partner notification or testing until 6 weeks after the participant’s enrolment. By contrast, in the immediate group, health advisors immediately initiated confidential Efforts to contact named sex partners, inform them of their potential exposure to HIV, offer to test them for HIV at home, the workplace, or other convenient venue and, for those testing HIV positive, refer them to an HIV clinic. Health advisors made three attempts to contact partners initially by telephone. If this contact was unsuccessful, they validated locator information with index participants and attempted to contact the partner in person at least twice. Those who refused testing or tested HIV negative were encouraged to test at a later date or retest as a couple and were counselled on HIV prevention methods, including condom use as per the HIV testing policy in Kenya. We classified partners as lost or non-locatable if telephone and in-person attempts were unsuccessful or if partners refused to meet with the health advisor.

In both study groups, health advisors contacted index participants and their sex partners 6 weeks after the index participant initial enrolment. In the delayed group, health advisors also provided participants with the same assisted partner service intervention at 6 weeks as participants in the immediate group received at the time of enrolment. Health advisors interviewing partners at 6 weeks in the delayed intervention clinics asked whether or not each partner had tested for HIV in the preceding 2 months (because, in these settings, events are mostly remembered in the month rather than the week that they occurred), and if they had, asked about their test result and whether or not they had sought medical care (HIV-positive partners only). In the immediate group, we contacted partners at 6 weeks and interviewed them again to verify if they tested at enrolment or, if after enrolment, whether they tested within the study. We assessed both index participants and their sex partners for IPV at their 6 week interview. To establish if IPV was related to study participation, we asked the index participant if the event they had experienced since enrolment was a result of their partner knowing their HIV status. We also considered IPV to be related to the study if the event occurred after notification of sex partners by study staff.

Following the Kenya HIV testing algorithm,15 we screened consenting participants for HIV antibody using the KHB Colloidal Gold assay (Shanghai Kehua Bio-engineering, Shanghai, China). We reported non-reactive specimens as HIV negative. We confirmed reactive specimens with the First Response 1–2.0 assay (Premier Medical Corporation, Daman, India) and reported those that tested reactive on both assays as having a final HIV-positive result.

We collected data on smartphones using the Open Data Kit platform, which were encrypted and submitted daily to servers at the National AIDS/Sexually Transmitted Diseases Control Programme. The University of Washington hosted the backup server. A safety review committee consisting of a National Institutes of Health medical officer, study coinvestigators, and study coordinators was convened every 6 months to review any episodes of IPV or other social harms.

Outcomes

The primary outcomes were the number of partners tested for HIV, the number who tested HIV positive, and the number enrolled in HIV care, all at 6 weeks. We defined partner HIV testing outcomes, including new HIV diagnoses, in the immediate group on the basis of verified outcomes among people tested by study staff and, when no test could be verified, by partner self-report at the 6 week follow-up interview. In the delayed group, we defined partners as having tested if they self-reported testing in the previous 2 months during the 6 week follow-up interview; we also based new HIV diagnoses on partner self-report. A further outcome not prespecified in the protocol was the number of partners testing for HIV for the first time, assessed at 6 weeks. Partners who tested for the first time in both groups were those testing within the study period who reported that they had never been tested before. In both study groups, we defined enrolment in HIV care among partners with HIV infections on the basis of partner self-report recorded during the 6 week follow-up interview. We plan to publish data for the secondary outcome of cost-effectiveness of assisted partner services separately.

Statistical analysis

We used the Hayes and Moulton formula16 and conservatively estimated that by enrolling 60 participants per cluster, we would require nine clusters per group to have 80% power at a significance level of 0·05 (two-tailed) to detect a two-times difference in the number of sex partners testing for HIV between the study groups. We assumed the number testing and newly diagnosed with HIV per index participant to follow a Poisson distribution (mean=λ0) and the coefficient of variation from cluster to cluster to be k=0·25.

We analysed the primary outcomes in sex partners who were interviewed at 6 week follow-up, and all 18 clusters contributed data for analysis. We assessed individual-level differences in baseline characteristics of study participants between randomisation groups with χ² tests for proportions and Wilcoxon Mann-Whitney tests for continuous distributions. We estimated incidence rate ratios for primary outcomes with a Poisson link and applying the number of index participants enrolled as the offset for each primary outcome. To account for clustering within study sites and nesting within index participants, we used generalised estimating equations to model the individual-level effect of assisted partner services on the primary outcomes. All models applied an independent correlation matrix and we did all analyses with Stata version 12.1.

We also calculated the incremental number needed to interview (NNTI) for each of our primary outcomes. The incremental NNTI is the number of index patients who needed to receive assisted partner services to achieve each outcome relative to the standard-of-care counselling provided in the delayed assisted partner services group. NNTI has been used in previous partner services assessments and is defined by the formula:13,17,18

Rates are defined as the number of outcomes observed in a group divided by the number of index participants in that group. This trial is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov, number NCT01616420.

Role of funding source

The funder of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report. However, Hans Spiegel, who works for the funder, was a member of the study’s data safety and monitoring board. PC, CF, KHÁ, and BS had full access to all the data in the study and PC and CF had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Results

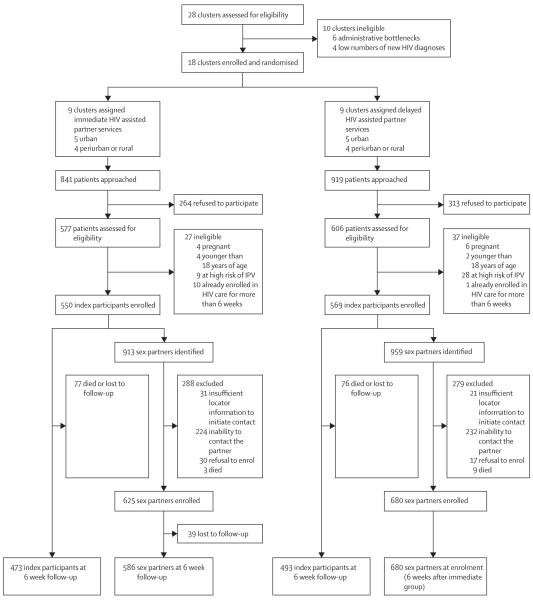

Between Aug 12, 2013, and Aug 31, 2015, we initially assessed 28 clusters for participation in the study, excluding ten (figure). We randomly assigned the remaining 18 clusters to receive either immediate or delayed assisted partner services. Study staff approached 1760 potential index participants for enrolment in the study, 841 in the immediate clusters and 919 in the delayed clusters; we enrolled 1119 index patients (figure). Among the 64 index participants with HIV infections who were ineligible, ten (1%) were pregnant, six (<1%) were younger than 18 years of age, 37 (3%) were at high risk of IPV, and 11 (1%) had already been enrolled in HIV care for more than 6 weeks. A mean of 62·2 participants were enrolled per cluster (SD 4·5). The index participants identified 1872 sex partners (mean per cluster 72·5 [SD 18·6]), 913 (49%) in the immediate group and 959 (51%) in the delayed group, of whom 1305 (70%) were successfully contacted and consented to enrol in the study (figure). 567 sex partners identified by index participants at their enrolment interview could not be enrolled (288 [51%] in the immediate group and 279 [49%] in the delayed group; figure). 6 week follow-up data were available for 473 (86%) index participants in the immediate group and 493 (87%) in the delayed group. 586 (94%) of 625 partners contacted in the immediate group were reinterviewed at 6 weeks. In all but one site, more female than male index participants enrolled (in Casino, 24 women enrolled compared with 36 men).

Figure. Trial profile.

IPV=intimate partner violence.

The median age of the index participants was 30 years (IQR 25–38) and of their sex partners was 31 years (26–37). Most index participants were women, were in stable relationships, and had previously tested for HIV (table 1). The mean number of sex partners identified per index participant was 1·67 (SD 0·26), and 547 (49%) of 1113 index participants identified more than one sex partner. 37 (3%) of 1113 reported four or more sex partners in the preceding 3 years. Despite a higher proportion of female index participants in the delayed group than in the immediate group (p=0·04), both study groups were similar at baseline in terms of sociodemographic characteristics, HIV testing behaviours, reported sexual history, geographical location, and number of partners identified per index case. Compared with those in the delayed group, sex partners in the immediate group were younger (p=0·001) and more likely to be women (p<0·0001; table 2). All other baseline characteristics of sex partners were similar across the two study groups.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of index participants

| Immediate group (n=550) |

Delayed group (n=569) |

|

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Sociodemographic | ||

|

| ||

| Age (years) | 30 (25–37) | 31 (26–38) |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 321 (58%) | 368 (65%) |

| Male | 229 (42%) | 201 (35%) |

| Marital status | ||

| Married monogamous | 306 (56%) | 308/568 (54%) |

| Married polygamous | 30 (5%) | 42/568 (7%) |

| Single | 104 (19%) | 100/568 (18%) |

| Non-married cohabiting | 21 (4%) | 14/568 (2%) |

| Separated or divorced | 67 (12%) | 74/568 (13%) |

| Widowed | 22 (4%) | 30/568 (5%) |

| Employment status | ||

| Unemployed | 138 (25%) | 120 (21%) |

| Student | 9 (2%) | 7 (1%) |

| Has means of economic support |

39 (7%) | 23 (4%) |

| Other | 90 (16%) | 90 (16%) |

| Employed | 412 (75%) | 449 (79%) |

|

| ||

| HIV behavioural characteristics | ||

|

| ||

| Ever tested for HIV | 379 (69%) | 366 (64%) |

| Self-reported last HIV test result | ||

| Does not know | 10 (2%) | 9 (2%) |

| HIV negative | 257 (47%) | 264 (46%) |

| HIV positive | 112 (20%) | 93 (16%) |

| Never tested for HIV | 171 (31%) | 203 (36%) |

| Reason for testing for HIV at enrolment | ||

| Sexual partner is HIV positive | 21 (4%) | 22/562 (4%) |

| Notified by partner | 14 (3%) | 18/562 (3%) |

| Notified by health provider or other |

7 (1%) | 4/562 (1%) |

| Pregnant or partner pregnant or new sexual relationship |

15 (3%) | 12/562 (2%) |

| Own health or other reason | 514 (93%) | 528/562 (94%) |

| Number of lifetime sexual partners |

4 (2–6) | 4 (3–8) |

| Number of new sex partners in last 3 months |

0 (0–1) | 0 (0–0) |

| Self-reported sexual preferences | ||

| Heterosexual | 536 (97%) | 561 (99%) |

| Bisexual or homosexual | 14 (3%) | 8 (1%) |

| History of transactional sex | 169 (31%) | 191 (34%) |

| Ever sexual relationship with partner with HIV infection |

30 (5%) | 23 (4%) |

| Condom use at last sex | 137 (25%) | 111 (20%) |

|

| ||

| Partner notifi cation characteristics | ||

|

| ||

| Number of index participants naming one sexual partner |

288/547 (53%) | 278/566 (49%) |

| Number of index participants naming two sexual partners |

191/547 (35%) | 211/566 (37%) |

| Number of index participants naming three sexual partners |

48/547 (9%) | 60/566 (11%) |

| Number of index participants naming more than three sexual partners |

20/547 (4%) | 17/566 (3%) |

|

| ||

| Facility-level characteristics | ||

|

| ||

| Region | ||

| Nairobi or central | 232 (42%) | 262/568 (46%) |

| Western (Kisumu or Siaya) | 318 (58%) | 306/568 (54%) |

| Location | ||

| Urban | 302 (55%) | 322 (57%) |

| Periurban | 185 (34%) | 186 (33%) |

| Rural | 63 (11%) | 61 (11%) |

Data are median (IQR), n (%), or n/N (%).

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of sexual partners of index participants

| Overall (n=1305) | Immediate group (n=625) |

Delayed group (n=680) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Sociodemographic | |||

|

| |||

| Age (years) | 31 (26–37) | 30 (26–37) | 32 (28–38) |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 567 (43%) | 309 (49%) | 258 (38%) |

| Male | 738 (57%) | 316 (51%) | 422 (62%) |

| Marital status | |||

| Married monogamous | 752 (58%) | 342 (55%) | 410 (60%) |

| Married polygamous | 105 (8%) | 60 (10%) | 45 (7%) |

| Single | 280 (21%) | 137 (22%) | 143 (21%) |

| Non-married cohabiting | 44 (3%) | 27 (4%) | 17 (3%) |

| Separated or divorced | 81 (6%) | 38 (6%) | 43 (6%) |

| Widowed | 43 (3%) | 21 (3%) | 22 (3%) |

| Employment status | |||

| Unemployed | 218/1298 (17%) | 126/623 (20%) | 92/675 (14%) |

| Student | 12/1298 (1%) | 7/623 (1%) | 5/675 (1%) |

| Other | 206/1298 (16%) | 119/623 (19%) | 87/675 (13%) |

| Employed | 1080/1298 (83%) | 497/623 (80%) | 583/675 (86%) |

|

| |||

| HIV behavioural characteristics | |||

|

| |||

| Number of lifetime sexual partners |

5 (3–8) | 4 (3–7) | 5 (3–9) |

| Number of new sexual partners in last 3 months |

0 (0–1) | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–1) |

| Self-reported sexual preferences | |||

| Heterosexual | 1280 (98%) | 619 (99%) | 661/679 (97%) |

| Bisexual or homosexual | 25 (2%) | 6 (1%) | 18/679 (3%) |

| History of transactional sex | 508 (39%) | 244 (39%) | 264 (39%) |

| Ever sexual relationship with partner with HIV infection |

99 (8%) | 49 (8%) | 50 (7%) |

| Condom use at last sex | 516 (40%) | 242 (39%) | 274 (40%) |

|

| |||

| Facility-level characteristics | |||

|

| |||

| Region | |||

| Nairobi or Central | 742 (57%) | 286 (46%) | 456 (67%) |

| Western (Kisumu or Siaya) | 563 (43%) | 339 (54%) | 224 (33%) |

| Location | |||

| Urban | 605 (46%) | 282 (45%) | 323 (48%) |

| Periurban | 425 (33%) | 211 (34%) | 214 (31%) |

| Rural | 275 (21%) | 132 (21%) | 143 (21%) |

Data are median (IQR), n (%), or median (range).

Among 625 enrolled sex partners in the immediate group, 392 (63%) consented to HIV testing, with 164 (26%) declining because they believed or knew that they were already infected (table 3). Of the 392 accepting testing at enrolment, 136 (35%) were infected with HIV. An additional 69 (11%) of 625 sex partners declined testing altogether either because they wanted to test later or elsewhere or had recently tested for HIV. 81 (13%) enrolled sex partners had never tested for HIV before and 33 (41%) of these 81 were infected with HIV.

Table 3.

HIV testing, new HIV diagnoses, enrolment in HIV care, and new HIV testing of sexual partners at 6 week follow-up

| Immediate group (n=586 sex partners at 6 week follow-up) |

Delayed group (n=680 sex partners at enrolment) |

IRR (95% CI)* | Coefficient of variation (95% CI) |

Incremental NNTI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Tested | 392 (67%); 0713 | 85 (13%); 0·149 | 4·8 (37-6·4) | 0·32 (0·17-0·48) | 1·8 |

|

| |||||

| Newly diagnosed | 136 (23%); 0247 | 28 (4%); 0·049 | 5·0 (3·2-7·9) | 0·10 (0·03-0·17) | 5·1 |

|

| |||||

| Newly enrolled in HIV care | 88 (15%); 0160 | 19 (3%); 0·033 | 4·4 (2·6-7·4) | 0·05 (0·01-0·10) | 7·9 |

|

| |||||

| Tested for the fi rst time | 81 (14%); 0·147 | 4 (1%); 0·007 | 14·8 (5·4-41·0) | 0·08 (0·02-0·14) | 7·1 |

Data are n (%); outcome per index case unless otherwise indicated. IRR=incidence rate ratio. NNTI=number needed to interview.

Estimated with use of generalised estimating equation Poisson regression with independent correlation matrix and index cases as off set variable.

Compared with the delayed group, assisted partner services significantly increased partner HIV testing, identification of previously undiagnosed partners with HIV infections, the number of partners with HIV infections linked to care, and first-time partner HIV testing (table 3). Among partners for whom data were available 6 weeks after index participants’ HIV diagnoses, only 85 (13%) of 680 partners interviewed in the delayed group had HIV tested compared with 392 (67%) of 586 partners in the immediate group who contributed 6 week follow-up data. Comparing the number of partners tested per index participant, immediate assisted partner services were associated with nearly five-times higher partner HIV testing. The impact of immediate assisted partner services was also substantial on sex partners testing for the first time, HIV case-finding among partners, and enrolment of partners with HIV infections into medical care (table 3). The NNTI to test one sex partner was 1·8 among all and 7·1 among those partners who had never tested. Compared with delayed assisted partner services, the NNTIs for case finding was 5·1 and for linkage was 7·9.

At 6 week follow-up, 105 (9%) of 1119 enrolled index participants (67 [12%] in the immediate group vs 38 [7%] in the delayed group) reported physical (33 [3%]; 20 [4%] vs 13 [2%]), emotional (60 [5%]; 40 [7%] vs 20 [4%]), or sexual (12 [1%]; seven [1%] vs five [1%]) IPV. We defined two IPV events, one in each group, as related to partner notification or study procedures. Assisted partner services had not been provided to either participant at the time of the IPV because one participant was in the delayed group and the other opted to notify their sex partner on their own.

Discussion

Findings from this large-scale pragmatic community trial substantiate that assisted partner services are safe and significantly increase HIV testing and case detection among partners of men and women testing HIV-positive in the clinical setting. We showed a substantial effect of assisted partner services in identifying undiagnosed infection. Our findings are consistent with previous data from sub-Saharan Africa, but also show some differences. Compared with the delayed intervention group, sex partners receiving immediate assisted partner services were 15 times as likely to be testing for the first time and five times as likely to be newly diagnosed with HIV. Previous studies of assisted partner services11,12,19 in sub-Saharan Africa have shown smaller effect sizes than those we observed, but also lower NNTIs. The larger effect seen in our study reffects a combination of high levels of partner testing in our intervention group and low levels of partner testing in our control group. Findings from an assisted partner services trial11 in patients attending sexually transmitted disease clinics in Malawi showed that 0·25 partners tested per index participant in the control group and another trial12 done in pregnant women in Malawi found that 0·52 partners tested per index participant in the control group, compared with 0·15 in the delayed intervention group in our study. Comparing the intervention groups, investigators of the two Malawi studies reported that assisted partner services increased partner to index test ratios to 0·52 in the sexually transmitted disease study and 0·74 in the pregnant women study compared with 0·71 among recipients of immediate assisted partner services in this study in Kenya. NNTIs of 3·57 for HIV case finding in the trial of Malawian pregnant women and 4·54 for sexually transmitted disease clinic patients were somewhat lower than we observed in Kenya in this study (5·1), reffecting the very high HIV test positivity observed in those studies (64% in the trial of sexually transmitted disease clinic patients and 71% in the trial of Malawian pregnant women) compared with what we found in Kenya in this study (35%).

The number of sex partners elicited (1·67 per index patient) in our study was also higher than that previously reported.11–13 Several factors might explain this difference. First, different studies have used different contact periods. Partner services among Malawi sexually transmitted disease clinic patients and people seen through a faith-based health-care organisation in Cameroon concentrated on sex partners from the preceding 3 months to 1 year, whereas services among pregnant women in Malawi focused on current partners.12 By contrast, we elicited sex partners from the preceding 3 years. In a study done in Mozambique, a large proportion of index participants (50%) named only one sex partner and the mean number of partners was 1·4.19

The acceptability of HIV testing among notified partners in this study was high (about 60%). An assisted partner services study in Cameroon13 showed a similar proportion of testing (67%). Although about 40% of partners did not consent to test in our study, about a quarter refused HIV testing because of the belief that they were already infected with HIV. Only 11% declined HIV testing in the absence of a previous HIV diagnosis. This finding is consistent with many opt-out approaches for HIV testing in which testing uptake is high.20–22 Thus, the acceptability of HIV testing is unlikely to be a major barrier in the scale-up and implementation of assisted partner services. Among these newly diagnosed individuals, enrolment in HIV care and initiation of ART were high, and this trend should be sustained since overall effectiveness of assisted partner services would be low if people with HIV infections were not linked to care, initiated on ART promptly, and followed up for optimal retention in care.23

We believe that our findings, in combination with previously published and presented data, show that assisted partner services is an efficacious and acceptable public health intervention that needs to be brought to scale in low-income and middle-income countries. The pragmatic design of our trial, its diverse clinical setting, and the broad eligibility criteria for index patient enrolment show that assisted partner services can be effectively implemented in public sector settings in Kenya. Specifically, exclusion of low-HIV prevalence sites reffect real-world considerations for scale up of partner services because the NNTI would be higher and assisted partner services less likely to be effective than in high-HIV burden settings. The consistency of our results with findings from previous small trials in Malawi11,12 and programmatic assessments in Cameroon13 and Mozambique19 strongly suggest that our findings are widely generalisable in sub-Saharan Africa. HIV partner services research now needs to focus on issues of implementation. Budgeting and cost-effectiveness of diverse clinical settings as proposed in this study require assessment.

We engaged highly trained health advisors to offer assisted partner services in the study, a model that might not be feasible as the services are brought to scale. Task shifting to a less highly educated cadre of providers than those used in this study should be possible as has been done with more complex interventions, such as male circumcision and delivery of ART and in other studies of assisted partner services.19,24–26 Our approach to data collection with use of the Open Data Kit platform has the advantage of acceleration of prompt public health action and could be expanded as technology and internet connectivity become increasingly pervasive in most parts of the world.27 However, cost-effectiveness studies are required to compare traditional data collection systems with Open Data Kit platforms. Also, a substantial proportion of sex partners could not be located in this study because they were not at home. Strategies to increase enumeration and tracing of sex partners might increase overall effectiveness of the intervention. Additionally, national programmes should explore different strategies to improve tracing. Text messaging-based and internet-based programmes might counterbalance these challenges.28,29 The one-way aspect of these approaches could be improved by interactive text messaging and internet communication as these approaches might, in addition to telephone contact, be preferred by health providers.30

Consistent with previous studies,11,12 we did not observe any association between IPV and assisted partner services. However, participants in our study did experience IPV; 11% of index patients reported some form of IPV, including 31% of whom reported episodes of physical violence. Clinics and public health agencies planning to institute assisted partner service programmes should consider screening patients to identify those at highest risk of IPV, counselling them, and referring them to specialised IPV management centres. Additional research and programme monitoring related to IPV will be important as assisted partner service programmes expand in sub-Saharan Africa and internationally.

Our study has its limitations. We excluded index participants at high risk of IPV; had we not, participants in the delayed group might have been disinclined to notify their sex partners, and so accrue fewer HIV testing outcomes, biasing our results away from the null hypothesis. The study verified HIV testing outcomes in the immediate group, but these outcomes were self-reported in the delayed group, which could have led to bias. However, sex partners in the delayed group are likely to have correctly reported their HIV testing because doing so would be socially desirable. IPV was also self-reported, but any resultant misclassification would have been non-differential between study groups. Additionally, this study was an unmasked study and health advisors in the delayed group might have provided more than the standard of care; as such, our results are more likely to be conservative than if it was masked. We used a 2 month recall for HIV testing outcomes in the delayed group, but we assumed that any HIV testing among participants in this group between the 6 week follow-up period and 2 month recall window was minimal.

Assisted partner services are effective at the population level and could play a pivotal role in reaching the Joint UN Programme on HIV/AIDS 90-90-90 targets9 through identification of new people with HIV infections, early initiation of ART, and potential viral suppression. It should be implemented as part of HIV testing service delivery with a focus on populations and regions with the highest risk of acquisition and lowest uptake of HIV testing services. Coupled with efficient linkage to care and immediate initiation of ART, as shown in the Strategic Timing of Antiretroviral Therapy trial,31 assisted partner services could potentially increase ART access and lead to population-level reductions in HIV incidence.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was made possible through a grant from the National Institutes of Health (NIH; R01 A1099974). CF had support from NIH grant K24 AI087399 and PC had support from NIH Fogarty International Center grant D43 TW009580. The findings and conclusions in this manuscript are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Government of Kenya.

Footnotes

Contributors

PC, CF, and MRG designed and developed the study. All authors contributed to study implementation. PC, PMM, BS, KHÁ, MRG, and CF analysed the data. PC drafted the manuscript. MRG, BW, BAR, PMM, PM, KHÁ, DB, FAO, AN, BS, MD, and CF reviewed the manuscript. PC, KHÁ, BS, and PM managed the database.

Declaration of interests

We declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Cates W, Jr, Toomey KE, Havlak GR, Bowen GS, Hinman AR. From the CDC. Partner notification and confidentiality of the index patient: its role in preventing HIV. Sex Transm Dis. 1990;17:113–14. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199004000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arthur G, Lowndes CM, Blackham J, Fenton KA. Divergent approaches to partner notification for sexually transmitted infections across the European Union. Sex Transm Dis. 2005;32:734–41. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000175376.62297.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Recommendations for partner services programs for HIV infection, syphilis, gonorrhea, and chlamydial infection. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2008;57(RR-9):1–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ferreira A, Young T, Mathews C, Zunza M, Low N. Strategies for partner notification for sexually transmitted infections, including HIV. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;10:CD002843. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002843.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hoxworth T, Spencer NE, Peterman TA, Craig T, Johnson S, Maher JE. Changes in partnerships and HIV risk behaviors after partner notification. Sex Transm Dis. 2003;30:83–88. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200301000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Joint UN Programme on HIV/AIDS . Global AIDS Update 2016. Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS; Geneva: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nǵanǵa A, Waruiru W, Ngare C, et al. The status of HIV testing and counseling in Kenya: results from a nationally representative population-based survey. J Acquir Immune Deffic Syndr. 2014;66(suppl 1):S27–36. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marum E, Taegtmeyer M, Parekh B, et al. “What took you so long?” The impact of PEPFAR on the expansion of HIV testing and counseling services in Africa. J Acquir Immune Deffic Syndr. 2012;60(suppl 3):S63–69. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31825f313b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Joint UN Programme on HIV/AIDS . Ambitious treatment targets: writing the final chapter of the AIDS epidemic. Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS; Geneva: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Landis SE, Schoenbach VJ, Weber DJ, et al. Results of a randomized trial of partner notification in cases of HIV infection in North Carolina. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:101–06. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199201093260205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brown LB, Miller WC, Kamanga G, et al. HIV partner notification is effective and feasible in sub-Saharan Africa: opportunities for HIV treatment and prevention. J Acquir Immune Deffic Syndr. 2011;56:437–42. doi: 10.1097/qai.0b013e318202bf7d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rosenberg NE, Mtande TK, Saidi F, et al. Recruiting male partners for couple HIV testing and counselling in Malawi’s option B+ programme: an unblinded randomised controlled trial. Lancet HIV. 2015;2:483–91. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3018(15)00182-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Henley C, Forgwei G, Welty T, et al. Scale-up and case-finding effectiveness of an HIV partner services program in Cameroon: an innovative HIV prevention intervention for developing countries. Sex Transm Dis. 2013;40:909–14. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wamuti BM, Erdman LK, Cherutich P, et al. Assisted partner notification services to augment HIV testing and linkage to care in Kenya: study protocol for a cluster randomized trial. Implement Sci. 2015;10:23. doi: 10.1186/s13012-015-0212-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.National AIDS and Sexually Transmitted Infection Control Programme . Guidelines for HIV testing and and counselling in Kenya. National AIDS and Sexually Transmitted Infection Control Programme; Nairobi: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hayes RJ, Bennett S. Simple sample size calculations for cluster-randomized trials. Int J Epidemiol. 1999;28:319–26. doi: 10.1093/ije/28.2.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Golden MR, Hogben M, Potterat JJ, Handsfield HH. HIV partner notification in the United States: a national survey of program coverage and outcomes. Sex Transm Dis. 2004;31:709–12. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000145847.65523.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ahrens K, Kent CK, Kohn RP, et al. HIV partner notification outcomes for HIV-infected patients by duration of infection, San Francisco, 2004 to 2006. J Acquir Immune Deffic Syndr. 2007;46:479–84. doi: 10.1097/qai.0b013e3181594c61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Feldacker C, Myers S, Cesar F, et al. Who benefits from assisted partner services in Mozambique? Results from a pilot program in a public, urban clinic. J Int AIDS Soc. 2015;18(5 suppl 4):20479. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Suthar AB, Ford N, Bachanas PJ, et al. Towards universal voluntary HIV testing and counselling: a systematic review and meta-analysis of community-based approaches. PLoS Med. 2013;10:e1001496. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baggaley R, Hensen B, Ajose O, et al. From caution to urgency: the evolution of HIV testing and counselling in Africa. Bull World Health Organ. 2012;90:652–58B. doi: 10.2471/BLT.11.100818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hensen B, Baggaley R, Wong VJ, et al. Universal voluntary HIV testing in antenatal care settings: a review of the contribution of provider-initiated testing & counselling. Trop Med Int Health. 2012;17:59–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2011.02893.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McNairy ML, El-Sadr WM. A paradigm shift: focus on the HIV prevention continuum. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59(suppl 1):S12–15. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ford N, Chu K, Mills EJ. Safety of task-shifting for male medical circumcision: a systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS. 2012;26:559–66. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32834f3264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kredo T, Adeniyi FB, Bateganya M, Pienaar ED. Task shifting from doctors to non-doctors for initiation and maintenance of antiretroviral therapy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;7:CD007331. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007331.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fairall L, Bachmann MO, Lombard C, et al. Task shifting of antiretroviral treatment from doctors to primary-care nurses in South Africa (STRETCH): a pragmatic, parallel, cluster-randomised trial. Lancet. 2012;380:889–98. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60730-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tom-Aba D, Olaleye A, Olayinka AT, et al. Innovative technological approach to Ebola virus disease outbreak response in Nigeria using the open data kit and form hub technology. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0131000. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0131000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hightow-Weidman L, Beagle S, Pike E, et al. “No one’s at home and they won’t pick up the phone”: using the internet and text messaging to enhance partner services in North Carolina. Sex Transm Dis. 2014;41:143–48. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Udeagu CC, Bocour A, Shah S, Ramos Y, Gutierrez R, Shepard CW. Bringing HIV partner services into the age of social media and mobile connectivity. Sex Transm Dis. 2014;41:631–36. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gilbart VL, Town K, Lowndes CM. A survey of the use of text messaging for communication with partners in the process of provider-led partner notification. Sex Transm Infect. 2015;91:97–99. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2014-051701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lundgren JD, Babiker AG, Gordin F, et al. Initiation of antiretroviral therapy in early asymptomatic HIV Infection. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:795–807. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1506816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.