Abstract

Ribavirin is a broad-spectrum antiviral drug with inhibitory activity against many RNA viruses, including measles virus. Five patients with subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE) were treated with ribavirin by intraventricular administration. Although there were transient side effects attributed to ribavirin, such as drowsiness, headache, lip and gingival swelling, and conjunctival hyperemia, intraventricular ribavirin therapy was generally safe and well tolerated. The cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) ribavirin concentration decreased, as described by a monoexponential function, after a single intraventricular dose. There was considerable interindividual variability, however, in the peak level and half-life. We aimed to adjust the individual dose and frequency of intraventricular administration based on the peak level and half-life of ribavirin in the CSF in order to maintain the CSF ribavirin concentration at the target level. Clinical effectiveness (significant neurologic improvement and/or a significant decrease in titers of hemagglutination inhibition antibodies against measles virus in CSF) was observed for four of five patients. For these four patients, CSF ribavirin concentrations were maintained at a level at which SSPE virus replication was almost completely inhibited in vitro and in vivo, whereas the concentration was lower in the patient without clinical improvement. These results suggest that intraventricular administration of ribavirin is effective against SSPE if the CSF ribavirin concentration is maintained at a high level. Intraventricular ribavirin therapy should be pursued further for its potential use for patients with SSPE and might be applied in the treatment of patients with encephalitis caused by other RNA viruses.

Subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE) is a progressive and fatal central nervous system disorder that results from a persistent SSPE virus infection. There is currently no specific treatment for SSPE. SSPE virus strains are measles viruses in which the viral genes encoding the structural proteins are altered. The altered genes appear to be important in the pathogenesis of the persistent central nervous system infection that yields the SSPE syndrome. We examined a wide variety of antiviral compounds for their inhibitory effects on measles and SSPE virus strains in vitro. Ribavirin inhibited the replication of SSPE virus strains more than other nucleoside and nonnucleoside compounds (6), including inosiplex and interferon (IFN), which are reported to prolong the lives of patients with SSPE. The 50 and 99% inhibitory concentrations of ribavirin in vitro were calculated to be 8.0 and 50 μg/ml, respectively (6, 8). In a hamster SSPE model, ribavirin administered into the subarachnoid space inhibited replication of SSPE virus in the brain and improved the survival rate (5). The MIC and complete inhibitory concentration of ribavirin in the hamster brain were estimated to be 5 to 10 μg/ml and 50 to 100 μg/ml, respectively (9).

Two patients with SSPE were treated safely and effectively with a high dose of intravenous ribavirin combined with intraventricular IFN (11). The ribavirin concentrations maintained in the serum (10.2 to 20.9 μg/ml) and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) (7.5 to 17.4 μg/ml) were comparable to the MICs in vitro and in vivo (7). Although there were definite improvements in the neurologic states of both patients, neurologic deterioration was observed a few months after the high-dose intravenous ribavirin therapy was stopped. For lasting efficacy, a higher ribavirin concentration in the CSF seems to be necessary. Because of systemic toxicity, i.e., anemia, we could not further increase the ribavirin dose by intravenous administration. Therefore, we administered intraventricular ribavirin to five patients with SSPE and analyzed the pharmacokinetics of ribavirin in the CSF.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Intraventricular ribavirin therapy was approved by the ethics committee of the institution to which the patients were admitted. Informed consent was obtained from the patients' parents after a full explanation of the procedures. Five children with SSPE were enrolled in the study. Oral isoprinosine and intraventricular IFN administrations were continued. For patients 1 and 2, intravenous ribavirin therapy preceded intraventricular ribavirin therapy. For the remaining three patients, ribavirin therapy was initiated with intraventricular administration. Ribavirin for intravenous use (virazole; ICN Pharmaceuticals, Costa Mesa, Calif.) was diluted to the appropriate concentration with saline solution, and 1 to 2 ml of diluted ribavirin solution was injected into the ventricular cavity through the Ommaya reservoir. Ribavirin at an initial dose of 1.0 mg/kg of body weight was administered intraventricularly, and CSF samples were collected from the Ommaya reservoir at 2, 6, and 12 h after administration and from a lumbar tap 6 h after administration.

Ribavirin concentrations were measured by high-performance liquid chromatography (9). In brief, the sample was diluted with 2 volumes of phosphate-buffered saline, 60% HClO4 was added to a final concentration of 0.5 M, and the sample was kept on ice for 30 min. The treated sample was centrifuged at 1,600 × g for 10 min. The supernatant was collected, neutralized with KH2PO4 and KOH, kept on ice for 5 min, and then used as a sample for a high-performance liquid chromatography assay. The sample (10 μl) was loaded onto a reverse-phase column (TGKgel ODS-12T column; Tosho, Tokyo, Japan) and eluted with the buffer at a flow rate of 1.0 ml/min. Absorbance at 226 nm was measured with a UV detector. The ribavirin solution (1 mg/ml) was diluted to 100, 50, 25, 12.5, 6.25, and 0 μg/ml with CSF taken from patients with leukemia for routine examination, and those diluted solutions were used as the ribavirin standard. The CSF ribavirin concentration was estimated from a standard curve of the optical density versus the ribavirin concentration. The correlation coefficient of optical density to ribavirin concentration was 0.99 within the range of 0 to 500 μg/ml. The lower limit of detection for the assay was 0.1 μg/ml. Data were averaged over two independent measurements.

The expected concentration immediately after administration (C0) and the half-life (t1/2) of ribavirin in the CSF were calculated from a curve of the ribavirin concentration versus time after administration. The target concentration of ribavirin in CSF was 50 to 200 μg/ml, at which point ribavirin completely inhibits SSPE virus replication and shows no toxicity in vitro or in vivo (6, 9). We aimed to adjust the dose and frequency of ribavirin administration to maintain the CSF ribavirin concentration at the target level. The frequency of intraventricular administration each day was set based on the individual's t1/2 as the trough concentration reached the lower limit of the target concentration (50 μg/ml) if the peak concentration was close to the upper limit of the target concentration (200 μg/ml): once a day for patient 4, twice a day for patients 1, 2, and 5, and three times a day for patients 3. We increased the dose of ribavirin from 1 to 2 and then to 3 mg/kg, until the ribavirin concentration in the CSF 2 h after administration was close to 200 μg/ml for patients 3 and 4. We continued ribavirin therapy at the initial dose of 1 mg/kg for patients 1 and 2, because the treatment was judged to be clinically effective. For patient 5, neurologic symptoms had deteriorated rapidly prior to the start of the initial treatment, and we did not increase the dose when the peak ribavirin concentration in the CSF was not high enough. We aimed to continue the administration for 10 days and repeated the 10-day therapy at 20-day intervals (patients 3 and 4). When side effects such as headache and drowsiness were observed, the administration period was reduced to 5 days, and the 5-day therapy was repeated at 10-day intervals to avoid serious side effects (patients 1, 2, and 5). CSF samples were collected from the Ommaya reservoir at 2 and 12 h after each administration for patient 1, at 2 and 12 h after the 1st and 5th administrations for patients 2 and 5, at 2 and 24 h after the 1st administration for patient 4, and at 2 and 8 h after the 1st and 7th administrations for patient 3. We did not administer intravenous ribavirin in addition to intraventricular ribavirin.

To evaluate clinical response, the neurologic disability index (NDI) score was assessed (4). The index consists of four sections: mental-behavioral, involuntary movement or seizures, motor-sensory, and vegetative-systemic. Each section consists of five items, and each item is scored on a five-point scale as follows: 0, no abnormality; 1 through 4, mild, moderate, severe, and profound abnormality, respectively. The NDI score is calculated as total accumulated points. Roughly, an NDI score of 0 to 25 is associated with stage I SSPE, a score of 26 to 50 is associated with stage II, 51 to 75 corresponds to stage III, and 76 to 88 corresponds to stage IV according to Jabbour's classification. A significant improvement was defined as a decrease of more than 10 points in the NDI score and a decrease of more than 1 in the clinical stage according to Jabbour's classification. Slight improvement was defined as a decrease of more than 2 points in the NDI score and no change in the clinical stage. Hemoglobin and reticulocyte examination, renal and liver function tests, electrolyte analysis, and urinalysis were used to assess drug toxicity weekly. Hemagglutination inhibition (HI) antibodies against measles virus in the CSF were examined monthly. A significant decrease in HI antibody levels was defined as a >4-fold decrease.

RESULTS

Ribavirin concentrations were similar in samples collected from the Ommaya reservoir and samples collected from the lumbar tap at 6 h after administration. The difference between the two concentrations was less than 30%. Thus, we used CSF samples collected from the Ommaya reservoir for measurement of ribavirin concentrations.

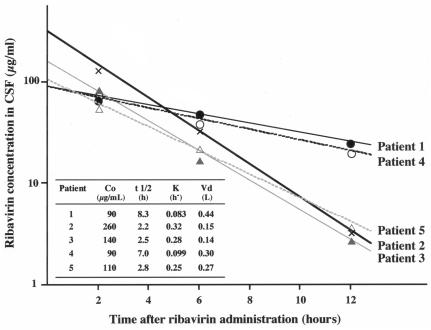

The concentration-time profile of ribavirin in CSF was described by a monoexponential function. Typical curves illustrating the individual CSF ribavirin concentration-time profiles are shown in Fig. 1. There was considerable interindividual variability in C0 and t1/2. C0 was high in patient 2, moderate in patient 3, and low in patients 1, 4, and 5. t1/2 was long in patients 1 and 4 and short in patients 2, 3, and 5.

FIG. 1.

CSF ribavirin concentration-time profiles after intraventricular administration of a single dose at 1 mg/kg. The CSF ribavirin concentration decreased, described by a monoexponential function. C0 and t1/2 differed across individuals. C0 was high in patient 2, moderate in patient 3, and low in patients 1, 4, and 5. t1/2 was long in patients 1 and 4 and short in patients 2, 3, and 5. The data were averaged over two independent measurements. The difference between the two measurements was less than 20%.

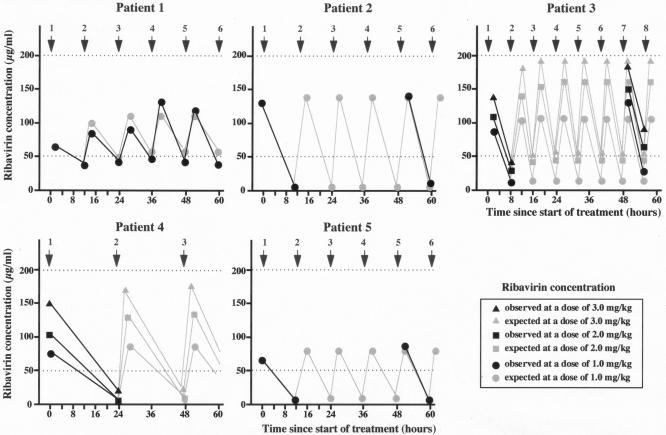

Patient 1 had previously received intravenous ribavirin therapy combined with intraventricular IFN-α therapy (10). The intravenous ribavirin therapy was repeated for more than 6 months. His hypertonicity, neurobladder incontinence, and dysphagia improved, although other neurologic symptoms did not change after combination treatment. The NDI score was 78, and the patient was in stage III to IV SSPE according to Jabbour's classification (Table 1). Intraventricular ribavirin administration at a dose of 1 mg/kg twice a day maintained the concentration of ribavirin in the CSF at 50 to 100 μg/ml (Fig. 2). Although there was no dramatic neurologic improvement, his neurologic state was slightly improved (stage III SSPE). The NDI score decreased to 75 at the end of the therapy, at 12 months. The titer of HI antibodies against measles virus in the CSF decreased markedly, from 1:128 to 1:8 (Table 1). Side effects, such as lip swelling, conjunctival hyperemia, and drowsiness, attributed to intraventricular ribavirin administration were observed 2 to 3 days after the start of therapy and disappeared 4 to 5 days after the cessation of therapy. The toxicities were transient and mild compared with those of high-dose intravenous administration.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of 5 patients with SSPE and their responses to intraventricular ribavirin therapy

| Patient | Age (yr) | Gender | Mo after onset | Dose of ribavirin (mg/kg/day) | Duration of therapy (mo) | Drugs combined with ribavirin | Clinical stage (Jabbour) | Clinical score (NDI)

|

Anti-measles antibody titer

|

General assessment | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before therapy | 3 moa | 12 moa | Before therapy | 3 moa | 12 moa | |||||||||

| 1 | 15 | Male | 12 | 2 | 12 | IFN + isoprinosine | III-IV→III | 78 | 75 | 75 | 1:128 | 1:64 | 1:8 | Improved |

| 2 | 14 | Female | 9 | 2 | 3 | IFN + isoprinosine | II→I | 32 | 22 | 19 | 1:16 | 1:8 | 1:4 | Improved |

| 3 | 6 | Male | 21 | 3-9 | 11 | IFN + isoprinosine | III→III | 75 | 73 | 70 | 1:64 | 1:16 | 1:16 | Improved |

| 4 | 6 | Female | 21 | 1-3 | 12 | IFN + isoprinosine | III-IV→III | 79 | 75 | 74 | 1:16 | 1:16 | 1:4 | Improved |

| 5 | 11 | Male | 3 | 2 | 4 | IFN + isoprinosine | III→III | 68 | 72 | 80 | 1:8 | 1:8 | 1:8 | Progressed |

Time after start of intraventricular ribavirin administration.

FIG. 2.

Expected and observed CSF ribavirin concentrations following repeated intraventricular administration. In patients 1, 2, 3, and 4, CSF ribavirin concentrations were maintained at almost completely inhibitory levels. The data were averaged over two independent measurements. The difference between the two measurements was less than 20%.

Patient 2 demonstrated remarkable clinical improvement after beginning intravenous ribavirin therapy (11). Intravenous ribavirin therapy was repeated for more than 6 months. Her myoclonic seizures disappeared, hearing in her right ear improved, and the NDI score decreased from 34 to 23. The titer of HI antibody against measles virus in the CSF decreased from 1:128 to 1:4, with clinical improvement. She returned to stage I SSPE according to Jabbour's classification. After intravenous ribavirin therapy was stopped, however, her neurologic state deteriorated (stage II SSPE; NDI score, 32) and the titer of HI antibodies against measles virus in the CSF increased to 1:16 (Table 1). Intraventricular ribavirin administration at a dose of 1 mg/kg twice a day maintained the concentration of ribavirin in the CSF at 10 to 150 μg/ml (Fig. 2). Her neurologic state again improved, and the titer of HI antibodies against measles virus in the CSF decreased to 1:4. At the end of 3 months of intraventricular ribavirin therapy, she was free from any convulsions or myoclonus and had an NDI score of 22 (Table 1). Side effects, such as lip swelling, conjunctival hyperemia, headache, and drowsiness, attributed to intraventricular ribavirin therapy were observed 2 to 3 days after the beginning of therapy and disappeared a few days after cessation of the therapy. There was no recurrence 6 months after termination of the therapy, and the NDI score was 19.

Patient 3 had measles at the age of 6 months. At the age of 6, he was diagnosed with stage III SSPE according to Jabbour's classification on the basis of clinical symptoms, electroencephalographic (EEG) abnormalities (periodic and synchronous discharge of high-voltage slow waves and spikes), and an elevated titer of HI antibodies against measles virus in the CSF (1:64). Intraventricular IFN-α therapy (300 × 104 IU twice a week) for 20 months did not improve his neurologic state. His disease was at stage III of Jabbour's classification, and his NDI score was 75, before the start of intraventricular ribavirin therapy (Table 1). Intraventricular ribavirin administration at a dose of 1 mg/kg three times a day maintained the CSF ribavirin concentration at 20 to 100 μg/ml. The dose of ribavirin administered intraventricularly was increased to 2 and then to 3 mg/kg three times a day, and the CSF ribavirin concentration increased to 40 to 150 μg/ml and 50 to 200 μg/ml, respectively (Fig. 2). His neurologic state improved slightly. The myoclonic seizures and periodic synchronous discharge on EEG disappeared 6 months after the start of therapy. Cyclic intraventricular ribavirin therapy was continued for 11 months. Although he remained in stage III SSPE according to Jabbour's classification, his response to stimuli improved, his respiratory state stabilized, and the NDI score decreased to 70. The titer of HI antibody against measles virus in the CSF decreased to 1:16 (Table 1). Lip swelling attributed to intraventricular ribavirin therapy was observed transiently and disappeared a few days after the cessation of therapy. No severe side effects were noted even at the highest dose (9 mg/kg/day) of ribavirin administered.

Patient 4 was diagnosed with stage II to III SSPE according to Jabbour's classification at the age of 4 on the basis of clinical symptoms, EEG abnormalities (periodic and synchronous discharge of high-voltage slow waves and spikes), and an elevated titer of HI antibody against measles virus in the CSF (1:16). Despite intraventricular IFN-α therapy (300 × 104 IU twice a week) for 13 months, her neurologic state gradually deteriorated. Her disease was at stage III to IV of Jabbour's classification, and her NDI score was 79, before the start of intraventricular ribavirin (Table 1). Intraventricular ribavirin administration at doses of 1, 2, and 3 mg/kg once a day maintained the concentration of ribavirin in CSF at 6 to 70, 10 to 100, and 25 to 150 μg/ml, respectively (Fig. 2). Cyclic intraventricular ribavirin therapy was continued for 12 months. Slight neurologic improvement was observed (NDI score, 74), and the titer of HI antibody against measles virus in the CSF decreased to 1:4 (Table 1). No obvious side effects attributed to intraventricular ribavirin therapy were observed.

Patient 5 had measles at the age of 18 months. At the age of 11, a decline in behavior and intellectual function became prominent. Atonic seizures and erratic myoclonus were frequently observed. He was diagnosed with stage II SSPE according Jabbour's classification on the basis of the clinical symptoms, an elevated titer of HI antibody against measles virus in the CSF (1:8), and detection of measles virus RNA in the CSF by reverse transcription-PCR. His clinical symptoms deteriorated rapidly, and his disease progressed to stage III of Jabbour's classification within 2 weeks after admission. When the Ommaya reservoir was implanted and ribavirin therapy was approved by the Ethics Committee, his NDI sore was 68 (Table 1). Intraventricular ribavirin therapy combined with intraventricular IFN therapy (300 × 104 IU twice a week) was started. Intraventricular ribavirin administration at a dose of 1 mg/kg twice a day maintained the concentration of ribavirin in the CSF at 10 to 75 μg/ml (Fig. 2). Cyclic intraventricular ribavirin therapy was continued for 4 months. Neither clinical improvement nor a decrease in the titer of HI antibody against measles virus in the CSF was observed. The NDI score at the end of 4 months of ribavirin therapy was 72 (Table 1). Lip and gingival swelling attributed to intraventricular ribavirin therapy was observed transiently.

DISCUSSION

There were mild and transient side effects, such as lip and gingival swelling, conjunctival hyperemia, headache, and drowsiness. Anemia, which is commonly encountered with systemic ribavirin administration, was not observed. Intraventricular administration of ribavirin was generally safe and well tolerated (12).

Individual CSF ribavirin concentrations immediately after intraventricular administration at a dose of 1 mg/kg were patient dependent. C0 was high in patient 2, moderate in patient 3, and low in patients 1, 4, and 5. This difference might be due to differences in individual CSF volume (3). Although the CSF ribavirin concentration decreased, as described by a monoexponential function, t1/2 also differed among individuals. The half-life of ribavirin in the CSF was long (7 to 9 h) in patients 1 and 4 and short (2 to 3 h) in patients 2, 3, and 5. The difference might be explained by differences in the clearance rate depending on the ability to produce and excrete CSF (1) and the volume of CSF (3). Therefore, intraventricular administration every 8 or 12 h was required for patients with a short ribavirin half-life. For patient 3, the ribavirin concentration was maintained at 50 to 200 μg/ml by intraventricular administration at a dose of 3 mg/kg every 8 h (9 mg/kg/day) and no serious side effects were observed. The CSF ribavirin concentrations were comparable to those at which ribavirin completely inhibited SSPE virus replication without toxicity in vitro and in vivo (50 to 200 μg/ml). Thus, we maintained effective and safe ribavirin concentrations in the CSF by adjusting the dose and frequency of intraventricular administration of ribavirin.

The neurologic condition improved significantly for one patient (patient 2), improved slightly for three (patients 1, 3, and 4), and deteriorated slightly for one (patient 5). The titer of HI antibody against measles virus in the CSF decreased significantly in four patients (patients 1, 2, 3, and 4) and was unchanged at relatively low levels in one (patient 5). Clinical effectiveness (significant neurologic improvement and/or significant decrease in the titer of HI antibody against measles virus in the CSF) was observed for four (patients 1, 2, 3, and 4) of five patients treated with intraventricular ribavirin therapy. In these four patients, CSF ribavirin concentrations were maintained at an almost completely inhibitory concentration (Fig. 2). Because intraventricular IFN plus oral isoprinosine therapy preceded intraventricular ribavirin therapy and did not modify clinical progression, the clinical effectiveness could be attributed to intraventricular ribavirin therapy. Neither neurologic nor laboratory improvement was observed for patient 5, whose CSF ribavirin concentration might not have been high enough to inhibit viral replication (Fig. 2). These results suggest that intraventricular administration of ribavirin is effective if the CSF ribavirin concentration is maintained at a high level. Placebo-controlled trials with a large number of patients at an early stage of SSPE are required. Such trials, however, are difficult because of the rare incidence of SSPE in countries where measles vaccination is widely applied.

Ribavirin was toxic at a concentration close to the effective concentration in vitro and in vivo. Therefore, monitoring of the CSF ribavirin concentration is necessary. We measured the ribavirin concentration in real time and adjusted the dose and frequency of ribavirin administration. This, however, is impossible in many institutions. One course of intraventricular ribavirin therapy consists of 10-day treatments at 20-day intervals or 5-day treatments at 10-day intervals. Ribavirin concentrations in the CSF after the initial treatment at a dose of 1 mg/kg twice a day should be measured, and the results should be used to adjust the dose and frequency of the next treatment.

CSF ribavirin concentrations were maintained at concentrations at which SSPE virus replication was completely inhibited in vitro and in vivo by adjusting the optimum dose and frequency of ribavirin administration. Ribavirin at this concentration might inhibit the replication of other RNA viruses (2, 10) such as paramyxoviruses, orthomyxoviruses, picornaviruses, togaviruses, and human immunodeficiency viruses. Intraventricular ribavirin therapy should be further pursued for its potential use for patients with SSPE and might be applied for the treatment of patients with encephalitis caused by other RNA viruses.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare of Japan.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bradbury, M. W. B. 1993. Anatomy and physiology of cerebrospinal fluid, p. 19-47. In P. H. Schurr, and C. E. Polkey (ed.), Hydrocephalus. Oxford University Press, Oxford, United Kingdom.

- 2.Crotty, S., D. Maag, J. J. Arnold, W. Zhong, J. Y. Lau, Z. Hong, R. Andino, and C. E. Cameron. 2000. The broad-spectrum antiviral ribonucleoside ribavirin is an RNA virus mutagen. Nat. Med. 6:1375-1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cutler, R. W., P. L. Page, J. Galicich, and G. V. Watters. 1968. Formation and absorption of cerebrospinal fluid in man. Brain 91:707-720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dyken, P. R., A. Swift, and R. H. DuRant. 1982. Long-term follow-up of patients with subacute sclerosing panencephalitis treated with inosiplex. Ann. Neurol. 11:359-364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Honda, Y., M. Hosoya, T. Ishii, S. Shigeta, and H. Suzuki. 1994. Effect of ribavirin on subacute sclerosing panencephalitis virus infections in hamsters. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 38:653-655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hosoya, M., S. Shigeta, K. Nakamura, and E. De Clercq. 1989. Inhibitory effects of selected antiviral compounds on measles (SSPE) virus replication in vitro. Antivir. Res. 12:87-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hosoya, M., S. Shigeta, S. Mori, A. Tomoda, S. Shiraishi, T. Miike, and H. Suzuki. 2001. High-dose intravenous ribavirin therapy for subacute sclerosing panencephalitis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:943-945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huffman, J. H., R. W. Sidwell, G. P. Khare, J. T. Witkowski, L. B. Allen, and R. K. Robins. 1973. In vitro effects of 1-β-d-ribofuranosil-1,2,4-triazole-3-carboxamide (virazole, ICN 1229) on deoxyribonucleic acid and ribonucleic acid viruses. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 3:235-241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ishii, T., M. Hosoya, S. Mori, S. Shigeta, and H. Suzuki. 1996. Effective ribavirin concentration in hamster brain for antiviral chemotherapy for subacute sclerosing panencephalitis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40:241-243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sidwell, R. W., J. H. Huffman, G. P. Khare, L. B. Allen, J. T. Witkowski, and R. K. Robins. 1972. Broad-spectrum antiviral activity of Virazole: 1-β-d-ribofuranosyl-1,2,4-triazole-3-carboxamide. Science 177:705-706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tomoda, A., S. Shiraishi, M. Hosoya, A. Hamada, and T. Miike. 2001. Combined treatment with interferon-alpha and ribavirin for subacute sclerosing panencephalitis. Pediatr. Neurol. 24:54-59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tomoda, A., K Nomura, S. Shiraishi, et al. 2003. Trial of intraventricular ribavirin therapy for subacute sclerosing panencephalitis in Japan. Brain Dev. 27:507-513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]