Abstract

Scope

Histone deacetylases (HDACs) have emerged as epigenetic regulators of risk factors associated with the metabolic syndrome (MetS), and certain botanical extracts have proven to be potent HDAC inhibitors. Understanding the role of dietary procyanidins in HDAC inhibition is important in exploring the therapeutic potential of natural products.

Methods

C57BL/6 mice were gavaged with vehicle (water) or grape seed procyanidin extract (GSPE, 250 mg/kg) and terminated 14 hours later. Liver and serum were harvested to assess the effect of GSPE on HDAC activity, histone acetylation, Pparα activity and target-gene expression, and serum lipid levels.

Results

GSPE increased histone acetylation and decreased Class I HDAC activity in vivo, and dose-dependently inhibited recombinant HDAC2 and 3 activities in vitro. Accordingly, Pparα gene and phosphorylated protein expression were increased, as were target-genes involved in fatty acid catabolism, suggesting increased Pparα activity. Serum fibroblast growth factor 21 (Fgf21) was elevated and triglyceride levels were reduced 28%.

Conclusion

GSPE regulates HDAC and Pparα activities to modulate lipid catabolism and reduce serum triglycerides in vivo.

Keywords: Fgf21, HDAC, Pparα, Procyanidins, Triglycerides

1. Introduction

The metabolic syndrome (MetS), a cluster of biochemical and physiological abnormalities, including central adiposity, hypertension, hyperglycemia, hypertriglyceridemia and low high-density lipoprotein (HDL) levels [1], is associated with the development of cardiovascular disease and other health issues, and currently affects approximately 1 in 3 adults in the US with increasing prevalence worldwide [2]. Epigenetics, heritable alterations in gene expression arising from environmental and other external influences, may play a role in the development of MetS [3]. Epigenetic changes are governed in large part by histone deacetylases (HDACs), which remove acetyl groups from histones as part of a corepressor complex that compacts chromatin and effectively inhibits the transcription of certain genes [3]. Because HDACs play a key role in repressing gene expression, HDAC inhibitors may exert therapeutic effects on diseases associated with metabolic dysregulation and MetS [3–5].

Class I HDACs (HDACs 1, 2 and 3) are targets of many HDAC inhibitors [5]. HDAC2 and 3 have demonstrated important roles in lipid metabolism via regulation of nuclear receptor expression and activity [4, 6–8]. In particular, HDAC3 inhibition via butyrate, trichostatin A or gene knockdown in mice upregulated the activity of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha (Pparα), a primary regulator of hepatic lipid metabolism, and also increased the expression of downstream Pparα target-genes involved in fatty acid catabolism, including fibroblast growth factor 21 (Fgf21) [4]. This suggests that HDAC inhibition may be a potential avenue through which disorders in lipid metabolism can be treated.

Studies with botanical extracts suggest that certain plant flavonoids may act as HDAC inhibitors [9–11]. Grape seed procyanidins were shown to significantly decrease HDAC activity and increase levels of acetylated H3K9 and H3K14, leading to increased gene expression, in vitro in skin cancer cells [12]. Grape seed procyanidin extract (GSPE) is primarily composed of monomeric and dimeric procyanidins and exerts numerous beneficial effects on MetS risk factors [13–18]. We previously showed that GSPE lowers serum triglycerides by 50% in vivo, an important risk factor for MetS, which was accompanied by increased fatty acid catabolism gene expression [16]. However, the ability of GSPE to act as an HDAC inhibitor as an underlying mechanism to decrease triglyceride levels remains unexplored.

This study was designed to test the hypothesis that GSPE inhibits HDAC activity, leading to increased PPARα target-gene expression and therefore fatty acid catabolism as a mechanism to lower serum triglycerides. Identifying mechanisms by which GSPE lowers serum triglyceride levels could facilitate utilization in the treatment of MetS risk factors, including hypertriglyceridemia.

Herein, we show that GSPE treatment in C57BL/6 mice repressed HDAC activity, increased Pparα phosphorylation, activated Pparα target-genes involved in hepatic fatty acid catabolism and increased serum Fgf21 levels, all of which were accompanied by a 28% decrease in serum triglyceride levels. Our results suggest that HDAC inhibition may be a novel mechanism leading to changes in lipid metabolism following GSPE administration.

2. Materials and methods

2.1 Chemicals and antibodies

All chemicals and antibodies were obtained from ThermoFisher Scientific, unless otherwise stated. GSPE was obtained from Les Dérives Résiniques et Terpéniques (Dax, France) [16, 17, 19], and was analyzed in-house, as described in the Supporting Information. GSPE has a total polyphenol content >68%. Results of the analysis are presented in the Supporting Information, Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 1. Antibodies for HDAC1, HDAC2, HDAC3, acetyl-lysine, acetyl-α-tubulin, acetyl-H3K9, and histone H3 were obtained from Cell Signaling, while those for β-actin and α-tubulin were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and Santa Cruz Biotech, respectively.

2.2 Animal studies

All procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Nevada, Reno (Protocol #: 00502). Four-week-old, male C57BL/6 mice (n=4 per group) were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA), housed under standard conditions and provided standard rodent chow (Harlan Teklad 8664) and water ad libitum. At 8-weeks of age the mice were orally gavaged with either vehicle (water) or GSPE (250 mg/kg) at 9pm and again at 9am the next day and terminated at 11am after a 2 hour fast [16, 17, 20, 21]. Blood was collected via retro-orbital bleeding under isoflurane anesthesia and livers were snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C. The GSPE dose utilized is one-fifth of the no-observed-adverse-effect level (NOAEL), as previously described for GSPE in rats [22], and effectively lowers serum triglyceride levels and modulates gene expression [16, 17, 20, 21]. Based on metabolic comparison, the dose of GSPE utilized in this study is equivalent to ~703 mg procyanidins/d in a 60 kg human [23].

2.3 RNA isolation and gene expression

RNA was extracted from frozen liver using TRIzol™ (Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Complementary DNA was synthesized using superscript III reverse transcriptase (Life Technologies). Gene expression was assessed by real-time quantitative PCR using a CFX96 Real-Time System (BioRad). Fold change in gene expression was calculated using the ΔΔCt method, and expression of β-actin and Gapdh were used as endogenous controls. Primer sequences are available in Supplementary Tables 2 and 3.

2.4 HDAC activity assays and Western blot analysis

Frozen mouse liver (untreated control) was homogenized in lysis buffer (300 mM sodium chloride and 0.5% Triton-X 100 in phosphate buffered saline) with Halt™ protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail. Protein concentration was assessed using a Pierce BCA protein assay kit. HDAC activity was assessed as previously reported [24, 25], and is detailed in the Supporting Information. The protein lysate was also used for Western analysis, as detailed in the Supporting Information.

2.5 Serum parameter analyses

Serum triglyceride and total cholesterol levels were determined using commercially available kits. Serum Fgf21 levels were determined using an ELISA kit (R&D Systems) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

2.6 Statistical analyses

One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test (in vitro analyses) or a student’s t-test (in vivo analyses) was used to detect statistical significance (GraphPad Prism v6.05 for Windows). p<0.05 was considered significant. Results are expressed as mean±SEM, n=4, analyzed in triplicate.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1 GSPE inhibits HDAC activity and increases histone acetylation

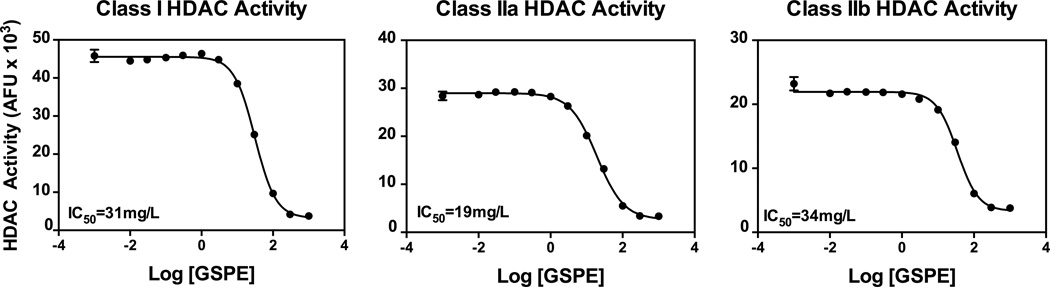

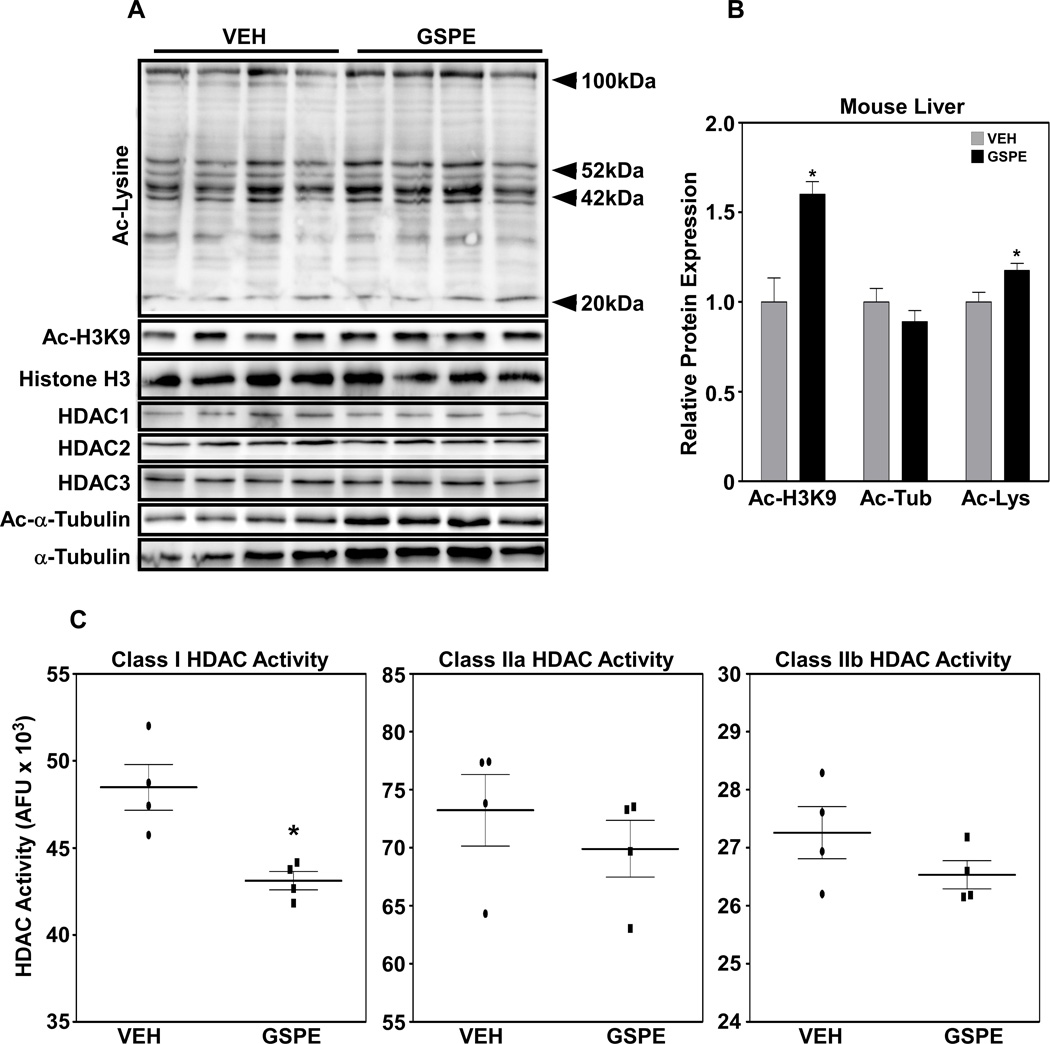

In vitro HDAC activity analyses using mouse liver cell lysate showed that increasing concentrations of GSPE inhibited the activities of Class I, IIa and IIb HDACs (Fig. 1). Further in vivo studies showed that, while there were no changes in Class I HDAC protein expression (Fig. 2A), Class I HDAC activity was significantly repressed (Fig. 2C). It is important to note that inhibition of HDACs can occur not only through changes in protein levels of the enzyme, but also via changes in activity [9]. Increased histone acetylation, evidenced by elevated protein expression of acetyl-H3K9 and acetyl-lysine in GSPE-treated mouse liver, also indicates decreased HDAC activity (Figs. 2A and B) [26]. In contrast to the in vitro assays, Class IIa and IIb activities were not significantly inhibited in vivo (Fig. 2C).

Figure 1. GSPE inhibits HDAC activity in vitro.

Class I, IIa and IIb histone deacetylase (HDAC) activity in the presence of increasing concentrations of GSPE (0.1–100000 mg/L) in mouse liver cell lysate.

Figure 2. GSPE increases histone acetylation and blocks Class I HDAC activity in vivo.

(A) Global profile of protein acetylation and histone deacetylase (HDAC)1, 2 and 3 expression in the mouse liver treated with GSPE (250 mg/kg) or vehicle (water). (B) Relative protein expression of acetylated (Ac)-H3K9, Ac-Lys and Ac-Tub. (C) Class I, IIa and IIb HDAC activities following GSPE treatment. *p<0.05

3.2 GSPE inhibits recombinant HDAC2 and 3 activities

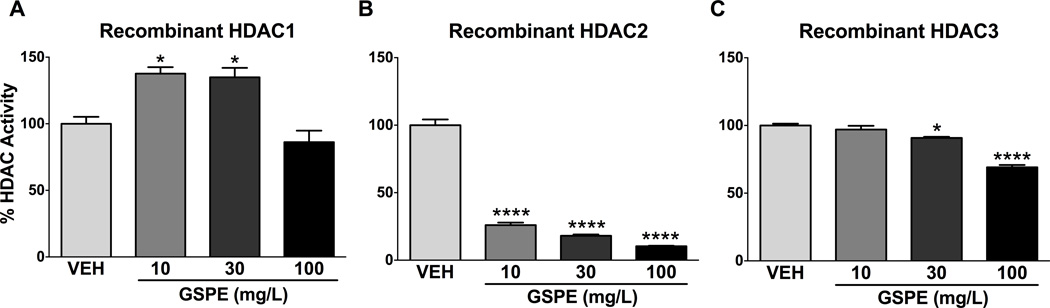

Since GSPE repressed Class I HDAC activity in vivo, we next assessed the effect on recombinant HDAC1, 2, and 3 activities. GSPE strongly and dose-dependently repressed HDAC2 activity at all concentrations (Fig. 3B) and inhibited HDAC3 activity dose-dependently at 30 and 100 mg/L (Fig. 3C). HDAC2 and 3 exert regulatory control on hepatic lipid metabolism, partly due to modulating nuclear receptor expression [4, 6–8], particularly Pparα, the master regulator of hepatic lipid metabolism [4]. Li and colleagues demonstrated that HDAC3 inhibition in mice upregulated Pparα activity [4], and phosphorylation of Pparα is required for its transcriptional activity [27, 28]. Based on these facts, our results suggest that inhibition of HDAC3 by GSPE facilitated increased phosphorylation (Fig. 4) and, therefore, Pparα trans-activity [27], although further research is needed to determine the underlying mechanism. While GSPE strongly suppressed HDAC2 activity (Fig. 3B), additional studies are necessary to determine whether HDAC2 inhibition leads to changes in Pparα expression and activity.

Figure 3. GSPE dose-dependently inhibits HDAC 2 and 3 in vitro.

Recombinant histone deacetylase (HDAC) activity using mouse liver cell lysate treated with GSPE for (A) HDAC1, (B) HDAC2 and (C) HDAC3. *p<0.05, ****p<0.0001.

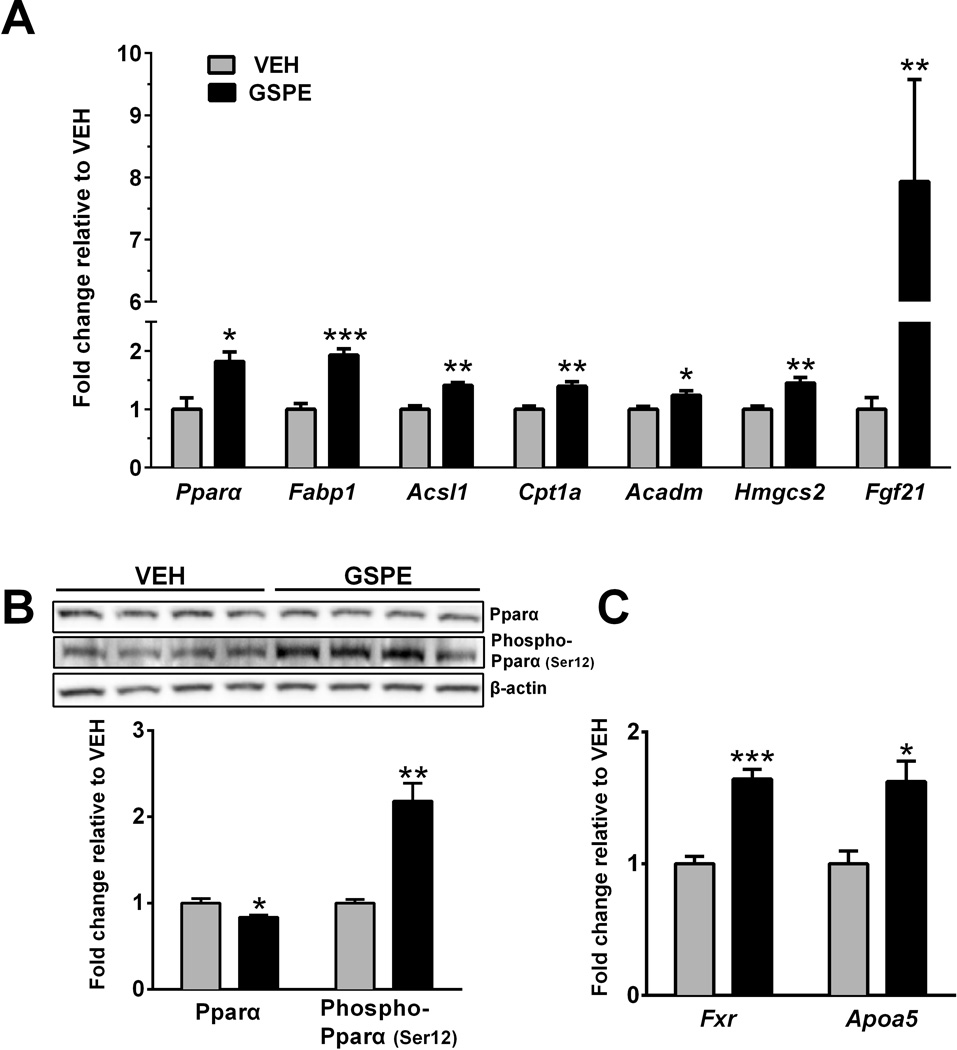

Figure 4. GSPE treatment enhanced Pparα gene and phosphorylated protein expression in vivo.

(A) Relative hepatic gene expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha (Pparα), fatty acid binding protein 1 (Fabp1), acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member 1 (Acls1), carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1a (Cpt1a), acyl-Coenzyme A dehydrogenase, medium chain (Acadm) and 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA synthase 2 (mitochondrial) (Hmgcs2) and fibroblast growth factor 21 (Fgf21). (B) Pparα and phospho-Pparα (Ser12) relative protein expression in mouse liver. (C). Relative hepatic gene expression of farnesoid × receptor (Fxr) and apolipoprotein a5 (Apoa5). *p<0.05, ** p<0.01, ***p<0.001.

The observation that GSPE increases recombinant HDAC1 activity (Fig. 3A) strongly suggests that GSPE is not a global HDAC inhibitor but instead may specifically target HDAC2 and 3. GSPE increases hepatic expression of small heterodimer partner (Shp) in a farnesoid × receptor (Fxr)-dependent manner, which leads to repression of sterol regulatory element binding protein (Srebp1c), the master regulator of lipogenesis, as a mechanism to lower serum triglyceride levels [16, 17]. Shp exerts most of its intrinsic inhibitory action via recruitment of HDACs, and the core repressive domains within Shp strongly interact with HDAC1 [29]. Therefore, it may be speculated that an increase in HDAC1 activity could be linked to downstream repressive effects consequential to Shp induction.

3.3 GSPE treatment enhanced Pparα trans-activity and target-gene expression in vivo

HDAC3 regulates the function of Pparα, the primary regulator of hepatic fatty acid β-oxidation [4]. Mechanistically this occurs via inhibition of HDAC3 activity at a PPARα target-gene promoter to enhance transcriptional activity [4]. For example, HDAC3 was shown to be a component of the corepressor complex and to interact with PPARα at the PPRE in the Fgf21 promoter [4]. Additionally, GSPE upregulates genes involved in fatty acid catabolism, namely, carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1a (Cpt1a) [16]. In the present study, we found that GSPE increased the expression of both Pparα (Fig. 4A) and its key target-genes involved in all stages of fatty acid catabolism, including Cpt1a (Fig. 4A). Although Pparα protein expression was decreased (Fig. 4B), phosphorylated Pparα protein expression was increased (Fig. 4C), therefore suggesting increased Pparα trans-activity at the promoter regions of direct target-genes [27].

Phosphorylation of Pparα can lead to increased transcriptional activity, either in the presence or absence of a ligand [30]. However, in the present study, it would be difficult to discern whether the GSPE-induced increase in fatty acid catabolism, which could elevate the level of endogenous ligands, contributed to increased Pparα trans-activity, or if phosphorylation of Pparα alone increases transcriptional activity, in a ligand-independent manner [30]. While a ligand-independent activation seems unlikely, due to the presence of fatty acids within the cell, further studies are needed to determine whether GSPE treatment leads to ligand-independent or ligand-dependent transcriptional Pparα activation.

3.4 GSPE treatment induced Fgf21 gene expression and serum levels in vivo

As mentioned above, Fgf21 is induced by HDAC3 inhibition, due to increased Pparα activity at its promoter [4]. Herein, we observed an 8-fold increase in Fgf21 gene expression (Fig. 4A) and a concomitant 7-fold increase in serum Fgf21 levels (Table 1). Fgf21 is synthesized exclusively within the liver, and then secreted into the serum to exert diverse physiological effects, possibly via hormonal activity [31], and has demonstrated therapeutic effects on non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, atherosclerosis and obesity [32]. Furthermore, Fgf21 administration in mice reduces plasma triglyceride levels [33] and recent clinical trials have shown that FGF21 agonism reduces serum triglyceride levels in humans [32]. Our results suggest that GSPE is a powerful inducer of Fgf21 and may indirectly increase Fgf21 gene and protein expression via HDAC inhibition and subsequent Pparα activation.

Table 1.

Serum parameters following GSPE administration

| Serum Parameter | VEH | GSPE |

|---|---|---|

| TG (mg/dL) | 62.60 ±1.65 | 45.29 ±1.24*** |

| CHOL (mg/dL) | 107.88 ±10.25 | 100.96 ±6.37 |

| NEFA (mmol/L) | 1.039 ±0.18 | 1.103 ± 0.034 |

| Fgf21 (pg/mL) | 177.30 ±17.88 | 1212.67 ±328.42* |

VEH: vehicle (water); GSPE: grape seed procyanidin extract (250 mg/kg); TG: triglyceride; CHOL: cholesterol; NEFA: non-esterified fatty acids; Fgf21: fibroblast growth factor 21.

p<0.05,

p<0.001.

3.5 GSPE treatment upregulated hepatic Fxr and Apoa5 gene expression and reduced serum triglyceride levels in vivo

In addition to the activation of genes involved in hepatic lipid catabolism, hepatic apolipoprotein a5 (Apoa5) and Fxr gene expression were increased (Fig. 4C), effects that correlate with increased triglyceride catabolism [34, 35] and decreased serum triglyceride levels. While APOA5 is a direct target of PPARα in humans, this has not been shown in rodents [36], although there is evidence that Fxr regulates Apoa5 in mice [37]. Our results suggest that GSPE upregulates Fxr expression, which in turn activates Apoa5 to allow increased triglyceride catabolism, in agreement with the fact that GSPE induces Apoa5 expression in wild-type but not Fxr−/− mice [17].

Consistent with the observed upregulation in Pparα gene expression and its associated targets involved in lipid catabolism, as well as Fxr and Apoa5, a 28% decrease in serum triglyceride levels was observed in GSPE-treated mice, compared to control (Table 1). Despite the hypocholesterolemic effects seen following GSPE treatment in previous studies [20], no significant change in total serum cholesterol was observed in the present study (Table 1). GSPE inhibits intestinal bile acid (BA) absorption via Fxr-dependent down-regulation of BA transporters, thereby reducing enterohepatic recirculation [20]. Decreased BA recirculation leads to increased hepatic BA biosynthesis, initially depleting the cholesterol pool within the liver. Subsequently TG catabolism is induced to facilitate endogenous cholesterol synthesis from acetyl CoA [20]. The diet used in the present study contained 60 µg/g cholesterol, therefore, dietary-derived cholesterol could first be used for BA biosynthesis, resulting in less of an effect on serum cholesterol levels compared to a previous study [20]. In addition, no changes in serum NEFA levels were observed (Table 1). NEFA produced from TG catabolism could be used for endogenous cholesterol biosynthesis, rather than being released into the serum, therefore, no significant differences were seen. These results represent the effects following an acute dose of GSPE, which are rapid and potentially short-lived. Future studies should include assessment regarding the effects of repeated GSPE consumption on HDAC inhibition and pharmacokinetics in human subjects over a longer period of time.

4. Concluding Remarks

In summary, this particular GSPE inhibits HDAC activity and increases histone acetylation, which correlates with increased Pparα activity and target-gene expression, increased lipid catabolism and reduced serum triglyceride levels in vivo. Furthermore, we identify GSPE as a potent dietary inducer of Fgf21, an important regulator of lipid metabolism. These results indicate that GSPE warrants further study as an HDAC inhibitor and a potential therapeutic for risk factors associated with MetS, particularly hypertriglyceridemia.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding was provided by the USDA NIFA (Hatch-NEV0738 and Multistate project W-3122: Beneficial and Adverse Effects of Natural Chemicals on Human Health and Food Safety; and Hatch-NEV0749) to MLR. Research was also supported by the NIGMS, NIH grant number: P20 GM103650. This work is dedicated to the memory of Catherine Ricketts.

Abbreviations

- GSPE

grape seed procyanidin extract

- HDAC

histone deacetylase

- MetS

metabolic syndrome

Footnotes

Author Contributions

MLR conceived and designed the studies; LED, BSF KR and MLR performed the studies and analyzed the data; LED and MLR wrote the manuscript

Conflict of Interest

The authors have declared no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Executive summary of the third report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) expert panel on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) JAMA. 2001;285:2486–2497. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.19.2486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andersen CJ, Fernandez ML. Dietary strategies to reduce metabolic syndrome. Reviews in Endocrine & Metabolic Disorders. 2013;14:241–254. doi: 10.1007/s11154-013-9251-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kirk H, Cefalu WT, Ribnicky D, Liu Z, Eilertsen KJ. Botanicals as epigenetic modulators for mechanisms contributing to development of metabolic syndrome. Metabolism-Clinical and Experimental. 2008;57:S16–S23. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2008.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li HT, Gao ZG, Zhang J, Ye X, et al. Sodium butyrate stimulates expression of fibroblast growth factor 21 in liver by inhibition of Histone Deacetylase 3. Diabetes. 2012;61:797–806. doi: 10.2337/db11-0846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ye JP. Improving insulin sensitivity with HDAC inhibitor. Diabetes. 2013;62:685–687. doi: 10.2337/db12-1354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee YH, Seo D, Choi KJ, Andersen JB, et al. Antitumor effects in hepatocarcinoma of lsoform-selective inhibition of HDAC2. Cancer Research. 2014;74:4752–4761. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-3531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Feng D, Liu T, Sun Z, Bugge A, et al. A circadian rhythm orchestrated by histone deacetylase 3 controls hepatic lipid metabolism. Science. 2011;331:1315–1319. doi: 10.1126/science.1198125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Knutson SK, Chyla BJ, Amann JM, Bhaskara S, et al. Liver-specific deletion of histone deacetylase 3 disrupts metabolic transcriptional networks. Embo Journal. 2008;27:1017–1028. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pandey M, Kaur P, Shukla S, Abbas A, et al. Plant flavone apigenin inhibits HDAC and remodels chromatin to induce growth arrest and apoptosis in human prostate cancer cells: In vitro and in vivo study. Molecular Carcinogenesis. 2012;51:952–962. doi: 10.1002/mc.20866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Attoub S, Hassan AH, Vanhoecke B, Iratni R, et al. Inhibition of cell survival, invasion, tumor growth and histone deacetylase activity by the dietary flavonoid luteolin in human epithelioid cancer cells. European Journal of Pharmacology. 2011;651:18–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2010.10.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Son IH, Chung IM, Lee SI, Yang HD, Moon HI. Pomiferin, histone deacetylase inhibitor isolated from the fruits of Maclura pomifera. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters. 2007;17:4753–4755. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2007.06.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vaid M, Prasad R, Singh T, Jones V, Katiyar SK. Grape seed proanthocyanidins reactivate silenced tumor suppressor genes in human skin cancer cells by targeting epigenetic regulators. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 2012;263:122–130. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2012.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Belcaro G, Ledda A, Hu S, Cesarone MR, et al. Grape seed procyanidins in pre- and mild hypertension: a registry study. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine: eCAM. 2013;2013:313142. doi: 10.1155/2013/313142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sapwarobol S, Adisakwattana S, Changpeng S, Ratanawachirin W, et al. Postprandial blood glucose response to grape seed extract in healthy participants: A pilot study. Pharmacognosy Magazine. 2012;8:192–196. doi: 10.4103/0973-1296.99283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kar P, Laight D, Rooprai HK, Shaw KM, Cummings M. Effects of grape seed extract in Type 2 diabetic subjects at high cardiovascular risk: a double blind randomized placebo controlled trial examining metabolic markers, vascular tone, inflammation, oxidative stress and insulin sensitivity. Diabetic Medicine. 2009;26:526–531. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2009.02727.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Del Bas JM, Ricketts ML, Baiges I, Quesada H, et al. Dietary procyanidins lower triglyceride levels signaling through the nuclear receptor small heterodimer partner. Molecular Nutrition & Food Research. 2008;52:1172–1181. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.200800054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Del Bas JM, Ricketts ML, Vaque M, Sala E, et al. Dietary procyanidins enhance transcriptional activity of bile acid-activated FXR in vitro and reduce triglyceridemia in vivo in a FXR-dependent manner. Molecular Nutrition & Food Research. 2009;53:805–814. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.200800364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Downing LE, Heidker RM, Caiozzi GC, Wong BS, et al. A grape seed procyanidin extract ameliorates fructose-induced hypertriglyceridemia in rats via enhanced fecal bile acid and cholesterol excretion and inhibition of hepatic lipogenesis. PloS One. 2015;10:e0140267. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0140267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Del Bas JM, Fernandez-Larrea J, Blay M, Ardevol A, et al. Grape seed procyanidins improve atherosclerotic risk index and induce liver CYP7A1 and SHP expression in healthy rats. Faseb Journal. 2005;19:479–481. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-3095fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heidker RM, Caiozzi GC, Ricketts ML. Dietary procyanidins selectively modulate intestinal farnesoid X receptor-regulated gene expression to alter enterohepatic bile acid recirculation: elucidation of a novel mechanism to reduce triglyceridemia. Molecular Nutrition & Food Research. 2016;60:727–736. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201500795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heidker RM, Caiozzi GC, Ricketts ML. Grape seed procyanidins and cholestyramine differentially alter bile acid and cholesterol homeostatic gene expression in mouse intestine and liver. PloS One. 2016;11:e0154305. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0154305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yamakoshi J, Saito M, Kataoka S, Kikuchi M. Safety evaluation of proanthocyanidin-rich extract from grape seeds. Food and Chemical Toxicology. 2002;40:599–607. doi: 10.1016/s0278-6915(02)00006-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rucker R, Storms D. Interspecies comparisons of micronutrient requirements: Metabolic vs. absolute body size. Journal of Nutrition. 2002;132:2999–3000. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.10.2999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lemon DD, Horn TR, Cavasin MA, Jeong MY, et al. Cardiac HDAC6 catalytic activity is induced in response to chronic hypertension. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology. 2011;51:41–50. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2011.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Williams SM, Golden-Mason L, Ferguson BS, Schuetze KB, et al. Class I HDACs regulate angiotensin II-dependent cardiac fibrosis via fibroblasts and circulating fibrocytes. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology. 2014;67:112–125. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2013.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Steele N, Finn P, Brown R, Plumb JA. Combined inhibition of DNA methylation and histone acetylation enhances gene re-expression and drug sensitivity in vivo. British Journal of Cancer. 2009;100:758–763. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Compe E, Drane P, Laurent C, Diderich K, et al. Dysregulation of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor target genes by XPD mutations. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 2005;25:6065–6076. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.14.6065-6076.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Juge-Aubry CE, Hammar E, Siegrist-Kaiser C, Pernin A, et al. Regulation of the transcriptional activity of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha by phosphorylation of a dependent trans-activating domain. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1999;274:10505–10510. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.15.10505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gobinet J, Carascossa S, Cavailles V, Vignon F, et al. SHP represses transcriptional activity via recruitment of histone deacetylases. Biochemistry. 2005;44:6312–6320. doi: 10.1021/bi047308d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Burns KA, Heuvel JPV. Modulation of PPAR activity via phosphorylation. Biochimica Et Biophysica Acta. 2007;1771:952–960. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2007.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Markan KR, Naber MC, Ameka MK, Anderegg MD, et al. Circulating FGF21 is liver derived and enhances glucose uptake during refeeding and overfeeding. Diabetes. 2014;63:4057–4063. doi: 10.2337/db14-0595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kharitonenkov A, DiMarchi R. FGF21 Revolutions: Recent advances illuminating FGF21 biology and medicinal properties. Trends in Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2015;26:608–617. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2015.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schlein C, Talukdar S, Heine M, Fischer AW, et al. FGF21 lowers plasma triglycerides by accelerating lipoprotein catabolism in white and brown adipose tissues. Cell metabolism. 2016;23:441–453. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nilsson SK, Heeren J, Olivecrona G, Merkel M. Apolipoprotein A-V; a potent triglyceride reducer. Atherosclerosis. 2011;219:15–21. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2011.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jiao Y, Lu Y, Li XY. Farnesoid X receptor: a master regulator of hepatic triglyceride and glucose homeostasis. Acta Pharmacologica Sinica. 2015;36:44–50. doi: 10.1038/aps.2014.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rakhshandehroo M, Knoch B, Muller M, Kersten S. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha target genes. PPAR research. 2010;2010 doi: 10.1155/2010/612089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stedman C, Liddle C, Coulter S, Sonoda J, et al. Benefit of farnesoid X receptor inhibition in obstructive cholestasis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2006;103:11323–11328. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604772103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.