Abstract

Ovarian cancer is the most lethal gynecologic cancer. Claudin-3 and-4, the receptors for Clostridium Perfringens Enterotoxin (CPE), are overexpressed in over 70% of these tumors. Here we synthesized and characterized poly(lactic-co-glycolic-acid) (PLGA) nanoparticles (NP) modified with the carboxi-terminal binding domain of CPE (c-CPE-NP) for the delivery of suicide gene therapy to chemotherapy-resistant ovarian cancer cells. As a therapeutic payload we generated a plasmid encoding for the Diphteria Toxin subunit-A (DT-A) under the transcriptional control of the p16 promoter, a gene highly differentially expressed in ovarian cancer cells. Flow cytometry and immunofluorescence demonstrated that c-CPE-NPs encapsulating the CMV GFP plasmid (CMV GFP c-CPE-NP) were significantly more efficient than control NP modified with a scrambled peptide (CMV GFP scr-NP) in transfecting primary chemotherapy-resistant ovarian tumor cell lines in vitro (p=0.03). Importantly, c-CPE-NPs encapsulating the p16 DT-A vector (p16 DT-A c-CPE-NP) were significantly more effective than control p16 DT-A scr-NP in inducing ovarian cancer cell death in vitro (% cytotoxicity: mean ± STDV = 32.9 ± 0.15 and 7.45 ± 7.93, respectively, p=0.03). In vivo bio-distribution studies demonstrated efficient transfection of tumor cells within 12 hours after intraperitoneal (IP) injection of CMV GFP c-CPE-NP in mice harboring chemotherapy-resistant ovarian cancer xenografts. Finally, multiple IP injections of p16 DT-A c-CPE-NP resulted in a significant inhibition of tumor growth compared to control NP in chemotherapy-resistant tumor-bearing mice (p=0.041). p16 DT-A c-CPE-NP may represent a novel dual-targeting therapeutic approach for the selective delivery of gene therapy to chemotherapy-resistant ovarian cancer cells.

Keywords: Ovarian Cancer, Clostridium Perfringens Enterotoxin (CPE), PLGA nanoparticles, Claudin-3 and -4, Chemotherapy resistance, Gene therapy

Introduction

Ovarian cancer remains the most lethal gynecologic malignancy in the USA(1). Despite the initial positive clinical response to surgery and chemotherapy, the majority of ovarian cancer patients eventually becomes resistant to chemotherapy and develop recurrent disease that is lethal in most cases(2, 3). Hence, there is an extreme need to develop more effective therapeutic strategies to target chemotherapy-resistant ovarian cancer.

The use of targeted therapies represents an ideal approach to maximize antitumor efficacy while minimizing treatment-related toxicity(4). With the aim of identifying ovarian cancer-specific targets, our group as well as others have evaluated the genetic alterations found in ovarian tumors(5–7). Data have consistently found that the genes encoding for claudin-3 and claudin-4 are highly differentially expressed in ovarian cancer cells compared to normal ovarian cells. More importantly, we showed higher expression of claudin-4 in chemotherapy-resistant versus matched chemotherapy-naïve tumors and in the sub-population of CD44-positive ovarian cancer stem cells compared to CD44-negative counterparts(8, 9).

Claudin-3/-4 are the high affinity receptors for Clostridium Perfringens Enterotoxin (CPE), a polypeptide of 319 amino acids associated with C. perfringens type-A food poisoning(10). Interestingly, although the full-length CPE is highly toxic when injected intravenously in animals, the carboxi-terminal fragment (i.e., the C-terminal 30aa) of CPE, is devoid of any toxicity while sufficient for binding to its receptors(11). Accordingly, several strategies have been developed that used the c-CPE as a tumor-specific carrier for diagnostic and therapeutic agents(12, 13). Importantly, recent data from our research group showed that c-CPE conjugated to the NearInfraRed-Dye CW800 is highly effective in identifying microscopic/metastatic ovarian tumor in the abdomen of mice harboring ovarian cancer xenografts(12, 14). Taken together theses evidences suggest that therapeutic systems that harness the targeting specificity of c-CPE may potentially be highly effective for the treatment of this disease.

Gene therapy represents an attractive alternative treatment modality in the management of ovarian cancer. Consistent with this view, a recent work by Huang et al. demonstrated that biodegradable poly(β-amino-ester) polymers may efficiently deliver transcriptionally targeted Diphteria Toxin subunit A DNA (i.e., the catalytic domain of the full length Diphteria Toxin: DT-A) to ovarian cancer cells in-vivo, resulting in strong inhibition of tumor growth(15). This study demonstrated that ovarian cancer cells are sensitive to DT-A exposure and that a DT-A-based gene therapy is an approach which should be considered for the treatment of this disease.

Poly-(D.L-lactic-co-glycolic)-acid-(PLGA)-nanoparticles-(NP) are well characterized, non-toxic and effective systems for the delivery of DNA to cancer cells(16). A recent study by our group evaluated the DNA delivery properties of a novel non-viral nanoparticle system containing a blend of PLGA and poly-(beta-amino)-ester (PBAE)(17). Data showed that the addition of PBAE to PLGA generated cationic nanoparticles that were efficient in transfecting tumor cells in-vitro. More importantly, results revealed increased plasmid loading capacity and improved transfection efficiency after conjugation of nanoparticles with cell-penetrating peptides (i.e., mTAT, bPrPp and MPG) via a PEGylated phospholipid linker (DSPE-PEG2000)(17).

Here we synthesized and characterized PLGA/PBAE NPs conjugated to the c-CPE peptide and tested their efficiency in delivering suicide gene therapy to chemotherapy-resistant ovarian cancer cells both in-vitro and in-vivo. As a therapeutic payload we encapsulated a plasmid into the NPs which encodes for the DT-A under the transcriptional control of the p16 promoter.

The cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p16 is encoded by the CDKN2A gene. P16 plays a pivotal role in the regulation of the transit through the G1 phase of the cell cycle by inhibiting the activity of CDK4 and CDK6. The binding of p16 to CDK4/6 prevents their association with cyclin D and the subsequent phosphorylation of substrates that are essential for the G1-S transition(18). Because of its function, p16 is considered a tumor suppressor gene. Deletions and mutations of p16 are commonly detected in many neoplasms, including ovarian cancer(19). Gene expression profiling analysis identified p16 as one of the top differentially expressed genes in ovarian cancer cells compared to normal ovarian cells(6). Moreover, multiple studies showed that p16 is overexpressed in the majority of ovarian tumors (up to 87%) and p16 overexpression correlates with tumor progression and poor prognosis(20–23). The upregulation of p16 mRNA has been suggested to be a consequence of the inactivation of the Retinobastoma (RB) tumor suppressor gene, a frequent genetic alteration seen in many cancer types(18).

This study was designed to exploit the overexpression of claudin-3/-4 as well as the p16 promoter by using c-CPE nanoparticles encapsulating a p16 transcriptionally regulated plasmid encoding DT-A. This approach may constitute an effective dual-targeting approach to safely deliver suicide gene therapy selectively to chemotherapy-resistant ovarian cancer cells. To test this hypothesis, p16 expression was evaluated by real-time PCR on 70 fresh ovarian tumor biopsies available in our laboratory. Next, p16 Luciferase and the p16 DT-A plasmids were generated and activity tested in-vitro against multiple primary ovarian cancer cell lines. PLGA/PBAE NPs conjugated to the c-CPE peptide were synthesized and characterized. They were then evaluated for their in-vitro and in-vivo transfection efficiency. Finally, the therapeutic efficacy of c-CPE NPs encapsulating the p16 DT-A DNA was tested in animals harboring chemotherapy-resistant ovarian cancer xenografts.

Material and Methods

Reagents

Poly(D, L lactic-co-glycolic acid), 50:50 was purchased from DURECT Corporation (Brimingham). Poly(beta amino ester) (PBAE) was synthesized by a Michael addition reaction of 1,4-butanediol diacrylate (Alfa Aesar Organics, Ward Hill) and 4,4′-trimethylenedipiperidine (Sigma, Milwaukee) as previously reported(24). The backbone plasmid pGL4.17[luc2/Neo] was purchased from Promega.

Primary cell lines and specimens

Protocol approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board at Yale University and all patients consented for tissue collection according to the institutional guidelines. The primary cell lines and the normal ovarian epithelial cells used in the current study were collected at the time of primary staging surgery or at the time of relapse after sterile processing of fresh tumor biopsy samples as previously described(25). The primary cell lines OSPC ARK-1 and CC ARK-1 were authenticated by whole exome sequencing (WES) in July 2016 at the Yale Center for Genome Analysis and chosen because of their high expression of claudin-3/-4 and p16 and their resistance to multiple chemotherapeutic agents verified by in vitro Extreme Drug Resistance assays (Oncotech Inc. Irvine; Supplementary table 1)(25). OSPC ARK-1 cell line harbored wild-type TP53 genes while CC ARK-1 demonstrated loss of TP53 function by WES (ie, loss of heterozygosity (LOH) (data not shown).

Quantitative Real-Time PCR (RT-PCR)

Flesh frozen samples as well as primary cell lines were tested by quantitative Real-Time PCR for the expression of p16 at mRNA level. Quantitative PCR was performed using a 7500 Real-time PCR System with the manufacturer’s recommended protocol (Applied Biosystems, Foster City) to evaluate expression of p16. The primers and probe for p16 were obtained from Applied Biosystems (assay ID Hs00233365_m1). The comparative threshold cycle (CT) method was used to determine gene expression in each sample using glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (assay ID Hs99999905_m1) mRNA level as internal control. In our analysis, a deltaCT<4 (calculated as the difference between the CT of the p16 and the CT of the GAPDH) arbitrarily identified high p16 expressors while a deltaCT>6 identified low p16 expressors. Three normal ovarian tissues were analyzed and used as controls to define our cut- offs.

Plasmid Constructions

P16 LUC: a 0.4-kb fragment containing the p16 promoter sequence (from the pGL410-p16-436-E2: a gift by Dr. DiMaio, Yale University) was cloned into the pGL4.17[luc2/Neo] vector following digestion of both plasmids with XhoI and HindIII restriction enzymes.

p16 DTA: a 0.5-kb fragment containing the Diphteria Toxin A (DTA) coding sequence was extracted from the pNHS103_V6 (a gift by Dr. Deans, University of Utah) using the following primers: forward (Hindtaf) 5′cgcaagcttatgggcgctgatgatgtt3′; reverse (xbadtaR) 5′gactctagattatcgcctgacacgatt3′. PCR was conducted on a GeneAmp® PCR system 2700 (Applied Biosystem; protocol: 94°C 5min, 40 cycles at 94°C 30sec/55°C 30sec/72°C 45sec, and final elongation at 72°C for 7min). The HindIII and XbaI restriction enzymes were used to clone this PCR product downstream the p16 promoter in the pGL410-P16-436-E2.

CMV DTA: DTA sequence was released by digestion of p16 DTA and cloned downstream the CMV promoter contained in the acceptor vector pGL4.17-CMV-LUC (available in our laboratory) in placed of the Luciferase sequence.

All plasmids were sequenced by the Keck DNA sequencing lab at Yale using the following primers: pGL4.17FP 5′ gctgtccccagtgcaagtgc 3′; pGL4rew 5′ctgctcgaagcggccggccgcc 3′ and dtaendf 5′ tgggaacaggcgaaagcgtta 3′. pGL4.17[luc2/Neo] vector was used as negative control

pCDNA3 CMV GFP: this plasmid was a kind gift by Dr. Wu (John Hopkins).

Transfection studies

The OSPC ARK-1 and the CC ARK-1 cell line were transfected with the X-tremeGENE 9 DNA Transfection reagent (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The activity of the p16 promoter was evaluated following transfection of tumor cells with the p16 LUC. After incubation (48 hours), protein lysates were quantified using a BCA kit (Thermo Fisher, Rockford) and Luciferase activity was measured following incubation of 20μl of total protein lysates with 100μl of Luciferase substrate for 5 minutes. Absorbance was read using a TD-20/20 Luminometer (Turner Designs). Data are presented as fold increase in Relative Light Units (RLU: Absorbance/μg of protein loaded) normalized to the control (cells transfected with the pGL4.17). The CMV LUC plasmid was used as positive control. Trypan Blue exclusion test was instead used to evaluate the cytotoxic effect of the p16 DTA. The pGL4.17 and the CMV DTA vectors were used as negative and positive control, respectively. Data are presented as % of death cells considering cells transfected with the pGL4.17 as 100% viable.

Synthesis of DSPE-PEG-c-CPE

DSPE-PEG (2000) maleimide (AVANTI Polar Lipids) was covalently linked to a modified version of the c-CPE (we introduced a Cysteine at N-terminal of c-CPE sequence in order to promote the reaction between the thiol group of the Cysteine and the maleimide group attached to the DSPE-PEG). Briefly, 4mgs of c-CPE were resuspended in distilled DMSO (100μl). The solution was vortexed and sonicated to ensure the complete dissolution of the peptide. The same procedure was performed to dissolve 2.5mgs of DSPE-PEG (2000) maleimide. The solutions were then mixed and the reaction was incubated at RT for 2 hours. After incubation, the solution was slowly added into 1ml DI water. The peptide in solution was added to a dyalisis bag (3.500 cut-off) and dyalized against water twice. The same procedure was used to generate the DSPE-PEG-scr using a modified version of the c-CPE found to have lower affinity for the claudin-3/-4 [we introduced two amino acids substitutions in residues critical for the c-CPE binding to the claudins (Y306A, L315A)](26).

c-CPE conjugated nanoparticles formulation

Nanoparticles were formulated using a modified double emulsion solvent evaporation technique as previously described(17). Briefly, a mix of PLGA and 15% PBAE was dissolved in dichloromethane (DCM:oil phase). DNA was dissolved in 1X TE buffer and added dropwise under vortex to the solvent-polymer solution. This blend solution was then sonicated on ice using a probe sonicator (Tekmar Company, Cincinnati) to form the first water-in-oil emulsion. The first emulsion was quickly added into a 5% aqueous solution of poly(vinyl alcohol) (PVA) co-dissolved with DSPE-PEG-c-CPE or the DSPE-PEG-scr under vortex and then sonicated to form the second emulsion. The second emulsion was then added to a stirring 0.3% PVA stabilizer solution and stirred overnight. Nanoparticles were then pelleted down and washed 3 times with diH2O prior to lyophilization. Dried nanoparticles were stored at −20°C until use.

Scanning electron microscopy

Morphology of scr-NP and c-CPE-NP was analyzed using an XL-30 scanning electron microscope (FEI, Hillsboro). The images were analyzed with ImageJ.

DNA release and loading

1mg of scr-NP or c-CPE-NP encapsulating the CMV GFP plasmid was incubated at 37°C in 1 ml of PBS or in culture medium (RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FBS) on a rotating shaker. At different time points (ranging from 1 to 168 hours) nanoparticles were pelleted and 100μl of supernatant were removed and stored for the analysis. An equal volume of fresh PBS was used to replace the collected supernatant. At the end of the 168 hours, DCM was added to the remaining particle pellet and the DNA was extracted. DNA content of each stored sample was analyzed using a Pico Green assay (Invitrogen).

Zeta potential

Zeta potentials of scr-NP and c-CPE-NP were measured using a Zetasizer Nano ZS (Malvern) with diH2O as a dispersant at pH6.

Surface density of the peptides on nanoparticles

The concentration of scr or c-CPE peptides on the nanoparticles surface was measured using a microBCA kit (Thermo Fisher, Rockford).

In-vitro transfection of c-CPE-NP

The primary chemotherapy-resistant ovarian cancer cell line OSPC ARK-1 and the normal epithelial ovarian cells (HOSE) were plated in six well plates at a density of 150,000 cells per well. The day after, 500–1000μg/ml of c-CPE-NP encapsulating different DNA cargo were suspended in culture medium, briefly sonicated and then added to the cells. After 72 hours of additional incubation at 37°C, the delivery properties of the CMV GFP c-CPE-NP were evaluated by flow cytometry and fluorescence microscopy while Trypan Blue exclusion test was used to evaluate the cytotoxic activity of c-CPE-NP encapsulating p16 DTA or CMV DTA plasmids. Treatments of cells with unconjugated NP or scr-NP encapsulating the same plasmids were used as controls.

In-vivo biodistribution of c-CPE-NP and therapeutic studies

C.B-17/SCID female mice 5–7 weeks old were purchased from ENVIGO (Indianapolis) and housed in a pathogen-free environment at Yale. They were given basal diet and water ad libitum. All experimental procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). Xenografts derived from the chemotherapy-resistant primary ovarian cancer cell line OSPC ARK-1 were established as previously described(14). Briefly, mice were injected subcutaneously with 5×106 OSPC ARK-1 cells. After 4–5 weeks, 2.5mg of c-CPE-NP encapsulating CMV GFP DNA labeled to the Cy5 dye (the conjugation was performed using the Label IT® Tracker™ Cy®5 Kit purchased from Mirus according to the manufacturer’s protocol) were injected intraperitoneally. Mice were sacrificed at different time points (ranging from 6 to 24 hours) after particle injection and tumors and healthy organs were excised and visualized with an In-Vivo FX PRO system (Bruker, Billerica; excitation/emission:550/635nm; 10 seconds exposure). In additional time course experiments animals were also injected using c-CPE-NP encapsulating the NearInfraRed Dye NIR790 in place of DNA to evaluate the uptake of NP in vivo. Tumor fluorescence quantification was performed calculating the mean fluorescence intensity of three different regions of interest (ROI) on the tumors surface. Data are presented as mean±STDV for each of the time point considered and are normalized on the mean fluorescence intensity detected on the tumors of mice non injected with the particles. In the therapeutic study, mice harboring sub-cute OSPC ARK-1-derived tumors were treated with 2.5mg of p16 DTA c-CPE-NP starting one week after tumor implantation. Mice received a total of 8 injections. Weight and tumor size were recorded twice a week. Tumor volume was calculated by the formula: V=lengthx(width)2/2 and was plotted as mean±SEM. Mice were euthanized according to the rules and regulations set forth by the IACUC at Yale.

Fluorescence microscopy

The tumors visualized with the In-Vivo FX PRO system for the biodistribution analyses were immediately fixed in cold 4% paraformaldehyde and stored at 4°C for 48 hours. After incubation, specimens were transferred in 30% sucrose in PBS for 72 hours and then embedded in Optimal Cutting Temperature compound (OCT). Cryosection slides of 10μm were cut by the Research Histology Department at Yale. Tissue was stained with Hoechst 33328 for 10min (1:5000 RT). Images were captured using an Axio Observer.Z1 inverted fluorescence microscope and analyzed with velocity software (Improvision, PerkinElmer).

Statistical analyses

Statistical comparisons between groups were done by the unpaired Student’s t test using Microsoft Excel. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

The p16 promoter is highly active in ovarian tumors

The aforementioned dual-targeting therapeutic approach relies on 1) the overexpression of claudin-3/-4 on the surface of ovarian tumor cells and 2) the transcriptionally regulated expression of DT-A by the p16 promoter. The extremely elevated expression of claudin-3/-4 by the majority of ovarian cancers has been widely demonstrated using gene expression profiling analyses by us as well as other groups(5–7, 27). More importantly, recent data showed that overexpression of claudin-4 is consistently detected in the chemotherapy-resistant cells when compared to chemotherapy-naïve matched samples as well as in a subpopulation of CD44+ ovarian cancer cells which are stem cell like and chemotherapy-resistant(8, 9).

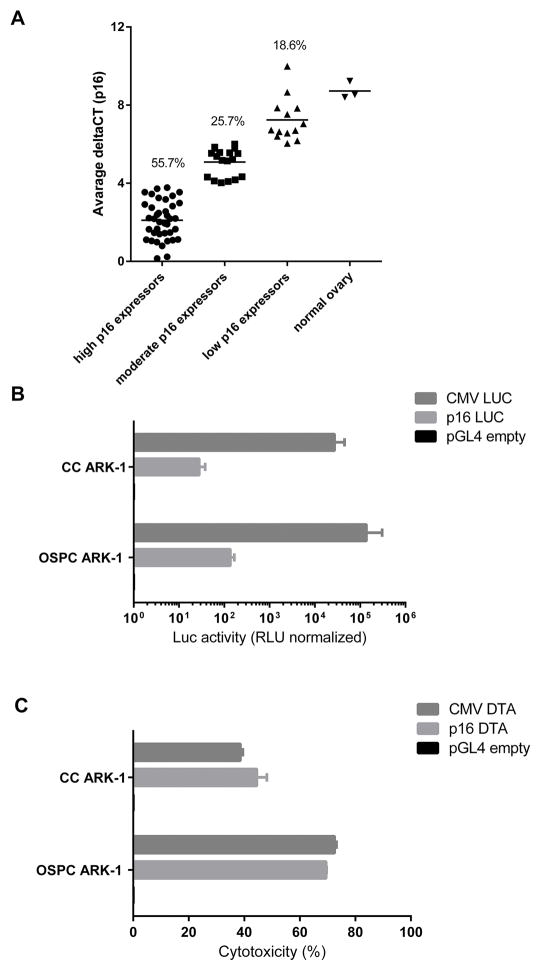

Our previously published genetic analyses also indicated preferential expression of p16 by primary ovarian tumor cells when compared to normal epithelial ovarian cells. To confirm these results in a separate cohort of ovarian cancer patients, the expression levels of p16 were evaluated on RNA samples extracted from 70 fresh ovarian tumor specimens by qRT-PCR (the histology and clinical stage of tumor samples from which RNA was extracted are presented in Supplementary Table 2). As shown in Figure 1A, over 80% of the fresh ovarian cancer samples were found to express moderate to high levels of p16 mRNA. These results confirmed our previous findings and suggest that a majority of ovarian tumors may be sensitive to gene therapies transcriptionally regulated by the p16 promoter. To assess whether the abundance of the p16 mRNA corresponded to an elevated activity of the promoter, the primary chemotherapy-resistant ovarian cancer cell lines OSPC ARK-1 and CC ARK-1 were transfected with the p16 LUC. The Luciferase activity was measured 48 hours later. As shown in Figure 1B, the Luciferase activity was significantly higher in lysates extracted from p16 LUC transfected cells when compared with the empty plasmid (fold increase in Luciferase activity: mean±SEM=136.7±20.8; p=0.023 and 28.155±4.88; p=0.0014 for OSPC ARK-1 and CC ARK-1, respectively). We then tested whether the p16 promoter was able to induce the expression of the DT-A in ovarian tumor cells. As shown in Figure 1C, the transfection of tumor cells with the p16 DT-A but not with the empty plasmid, was highly cytotoxic indicating that p16 was active in promoting the DT-A expression (%cytotoxicity: mean±SEM=68.45±0.15; p<0.001 and 44.55±2.55; p=0.003 for OSPC ARK-1 and CC ARK-1, respectively). Interestingly, both the p16 DT-A and the CMV DT-A (positive control) plasmids had a similar cytotoxic effect suggesting an exquisite sensitivity of ovarian tumor cells to the cytotoxic activity of the DT-A (Figure 1C). In contrast, negligible cytotoxicity was detected in HOSE control cells (ie, P16 mRNA low) when challenged with p16 DT-A (data not shown).

Figure 1. p16 expression and activity in ovarian tumors.

(A) p16 mRNA is expressed at moderate to high levels by Real-Time PCR in over 80% of the fresh ovarian tumor sample tested. (B) Activity of the p16 promoter following transfection of primary chemotherapy-resistant ovarian cancer cells with the p16 LUC plasmid. Luciferase activity was tested 48 hours after transfection as described in Methods. Data are presented as relative light units (RLU) normalized on the activity found in lysates of cells transfected with the empty plasmid chosen as the control. (C) Cytotoxicity assay results following transfection of OSPC ARK-1 and CC ARK-1 primary chemotherapy-resistant ovarian cancer cells with the p16 DT-A plasmid. Data are presented as % of cytotoxicity normalized to controls (ie, cells transfected with the empty plasmid considered 100% viable). CMV DT-A plasmid was used as a positive control.

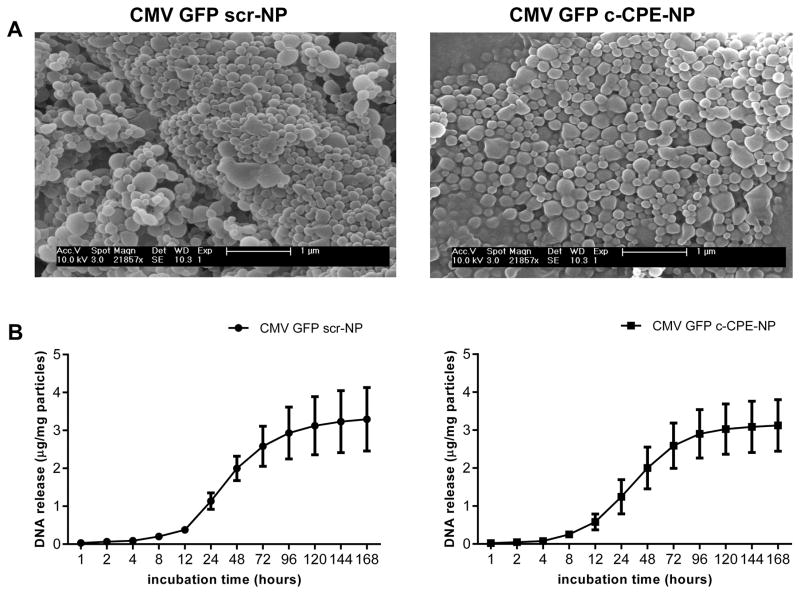

Characterization of the c-CPE NP

The characterization of the CMV GFP c-CPE-NP and scr-NP included the evaluation of the morphology and the size of the particles, the determination of the Zeta potential, the quantification of the amount of scramble or c-CPE peptide conjugated to the particles’ surface and the evaluation of the DNA release profile. SEM micrographs revealed that both particle formulations were spherical in shape with a diameter of approximately 170nm (Figure 2A). Particles were positively charged (Zeta potential: mV±STDV=33.3±0.5 and 34.9±0.6 for the scr-NP and the c-CPE-NP, respectively), had a similar plasmid loading (3.33±1.38μg DNA/mg scr-NP±STDV and 3.37±0.75μg DNA/mg c-CPE-NP±STDV) and comparable peptide coating density (μg scr-peptide/mg scr-NP±STDV=3.13±0.26 and μg c-CPE/mg c-CPE-NP±STDV=3.5±0.21; Supplementary Table 3). When incubated at 37°C in PBS, both c-CPE-NP and scr-NP showed an initial slow release of the DNA followed by a burst between 12 and 72 hours of incubation (Figure 2B). Similar results were obtained when the experiment was performed in culture medium (Supplementary figure 1 and Supplementary table 3). Importantly, the chemical characteristics and the DNA release profile of the particles were comparable to the ones obtained previously during the characterization of similar particle formulations (i.e., PLGA/PBAE NP conjugated to cell-penetrating peptides)(17), suggesting highly reproducibility of the nanoparticle system.

Figure 2. Particles characterization.

(A) Representative SEM micrographs depicting scr-NP (left panel) and c-CPE-NP (right panel) encapsulating the CMV GFP plasmid (CMV GFP scr-NP and CMV GFP c-CPE-NP, respectively). (B) Release of plasmid DNA over a one week period from CMV GFP scr-NP (left panel) and CMV GFP c-CPE-NP (right panel). Both particle formulations showed an initial slow release of the DNA followed by a burst between 12 and 72 hours of incubation in PBS at 37°C.

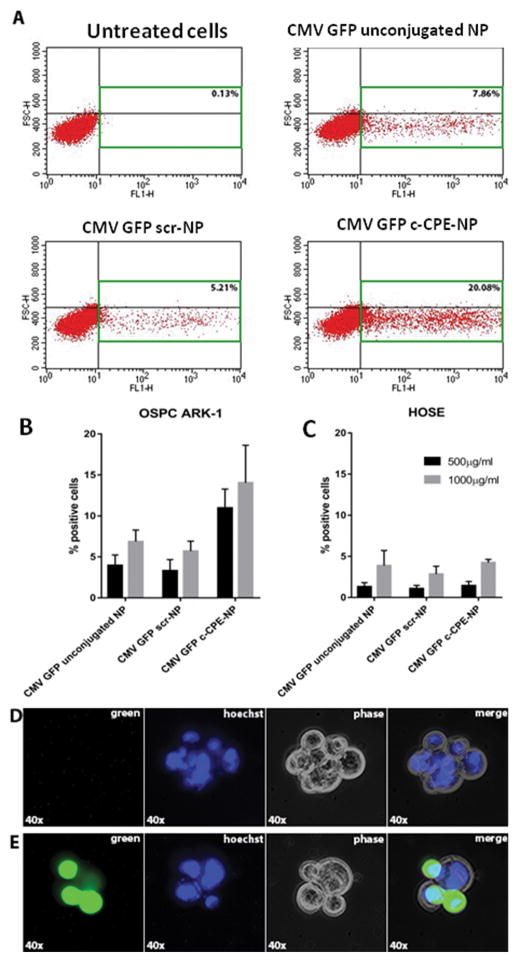

c-CPE-NP specifically delivers DNA to ovarian cancer cells in-vitro

To assess whether c-CPE-NP were able to efficiently transfect ovarian tumor cells in-vitro, OSPC ARK-1 primary ovarian cancer cells were incubated with different doses (i.e., 500 and 1000μg/ml) of c-CPE-NP encapsulating the CMV GFP plasmid for 72 hours in complete medium. After incubation, flow cytometry and fluorescence microscopy were used to evaluate the GFP expression. As representatively shown in Figure 3, c-CPE-NP were significantly more efficient than unconjugated NP or scr-NP in transfecting OSPC ARK-1 tumor cells (Figure 3A–B: % of transfected cells at 1000μg/ml:mean±STDV=5.65±1.65, 5.7±1.22 and 14.05±4.6 for unconjugated NP, scr-NP and c-CPE-NP, respectively; p=0.028 for unconjugated versus c-CPE-NP and p=0.03 for scr-NP versus c-CPE-NP). Importantly, when claudin-3/-4 negative normal human ovarian surface epithelial cells (HOSE) were incubated with the same doses of particles, extremely low transfection was observed, suggesting that the presence of the claudin-3/-4 on the cell membrane is essential to promote c-CPE-NP internalization (Figure 3C). Fluorescence microscopy was used to confirm the expression of the GFP within the tumor cells transfected with the CMV GFP c-CPE-NP (Figure 3D–E).

Figure 3. c-CPE-NP transfection efficiency in vitro.

(A) Representative flow cytometry plots depicting the percentage of positive cells for GFP expression following incubation of OSPC ARK-1 ovarian tumor cells with 1000μg/ml of unconjugated NP, scr-NP or c-CPE-NP encapsulating the CMV GFP plasmid for 72 hours. c-CPE-NP were significantly more efficient in transfecting tumor cells when compared to unconjugated NP and scr-NP. (B–C) Quantification of flow cytometry data following incubation of OSPC ARK-1 ovarian tumor cells and claudin-3 and -4 negative human epithelial surface ovarian cells (HOSE) with 500 or 1000μg/ml of unconjugated NP, scr-NP or c-CPE-NP encapsulating the CMV GFP plasmid for 72 hours. (D–E) Fluorescence microscopy images confirmed the expression of GFP within the OSPC ARK-1 ovarian tumor cells (E). Unstained cells imaged using the same protocol as a control for cell autofluorescence (D).

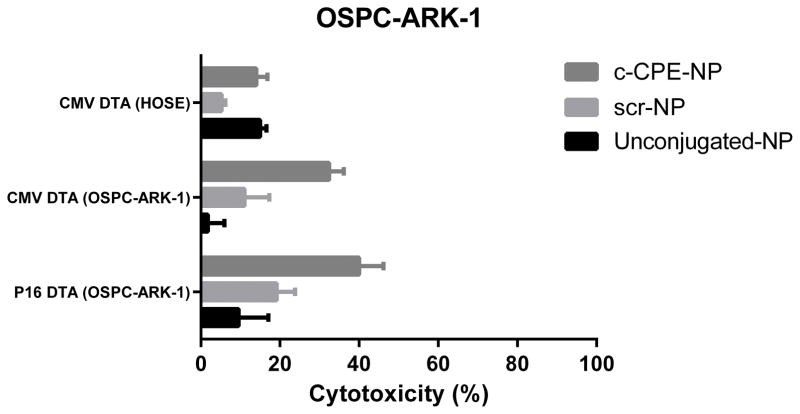

p16 DT-A c-CPE-NP are highly cytotoxic in-vitro

We then evaluated the cytotoxic effect of p16 DT-A c-CPE-NP against chemotherapy-resistant ovarian tumor cells. As shown in figure 4, c-CPE-NP showed higher cytotoxic effect than unconjugated NP and scr-NP when incubated with OSPC ARK-1 ovarian tumor cells for 72 hours (%cytotoxicity:mean±STDV=9.5±15.04, 19.1±9.42 and 40±12.35 for unconjugated NP, scr-NP and c-CPE-NP, respectively; p=0.02 for unconjugated NP versus c-CPE-NP and p=0.04 for scr-NP versus c-CPE-NP). No significant difference in cell toxicity was found between p16 DTA c-CPE-NP and CMV DTA c-CPE-NP. This confirms data obtained after transfection of cells with the nude plasmids and suggests that ovarian tumor cells are extremely sensitive to the cytotoxic effect of the DT-A (Figure 4). Consistent with the results obtained with CMV GFP c-CPE-NP, extremely low toxicity was reported following incubation of HOSE with c-CPE-NP.

Figure 4. Cytotoxic effect of c-CPE-NP encapsulating the p16 DT-A plasmid on ovarian tumor cells in vitro.

OSPC ARK-1 ovarian tumor cells were incubated with 500μg/ml of unconjugated NP, scr-NP or c-CPE-NP encapsulating the p16 DT-A plasmid for 72 hours in complete medium. After incubation cells were counted using the Trypan blue exclusion test as described in Methods. c-CPE-NP induced a significantly higher cytotoxic effect when compared with unconjugated NP and scr-NP. A similar toxic effect was observed following incubation of tumor cells with c-CPE-NP encapsulating the CMV DT-A plasmid (ie, positive control). In contrast, no significant differences in cytotoxicity were detected in HOSE cells (ie, claudin-3 and -4 negative).

c-CPE-NP are highly efficient in transfecting ovarian cancer cells in-vivo

In the current study, intravenous (i.v.) administration of the c-CPE-NP was initially attempted in tumor-bearing SCID mice. However, low concentrations (i.e., 500μg) of c-CPE-NP injected i.v. caused massive thrombosis in the pulmonary vasculature. This high toxicity was not surprising considering the cationic nature of our NPs (Zeta Potential ~30 mV; Supplementary Table 3) which confers a strong tendency to aggregate when resuspended in injectable volumes of solvent(28). A way to potentially avoid this effect would be to perform a continuous and slow infusion of the particles using drug delivery pumps. This approach, although widely utilized in clinical practice for the i.v. delivery of therapeutics in patients(29, 30), is challenging in preclinical models and has been successful only for sub-cutaneous or intraperitoneal delivery of drugs in mice(31, 32). Accordingly, we chose to inject nanoparticles intraperitoneally (IP). This route of administration has been shown to be highly effective for the delivery of chemotherapy in ovarian cancer patients. Moreover, IP delivery of suicide gene therapy by biodegradable poly(β-amino ester) polymers has already been shown to be efficacious in the treatment of ovarian cancer xenografts(15).

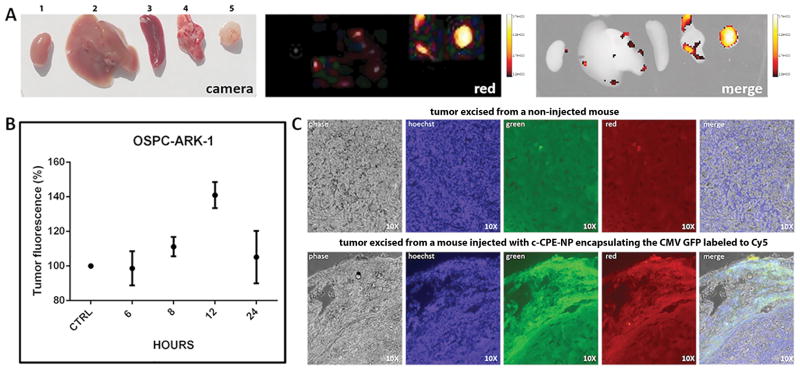

To assess whether the c-CPE-NPs were able to accumulate into ovarian tumors, 1 mg of c-CPE-NP encapsulating the NIR790 dye were injected IP in tumor bearing mice. At different time points (ie, 3 hrs, 12 hrs, 24 hrs, 96 hrs and 144 hrs) animals were imaged using and In-Vivo imaging system (Bruker). As shown in Supplementary figure 2, c-CPE-NP were able to rapidly accumulate into ovarian tumors and to persist at the tumor site for up to 96 hours after NP injection. Next, to evaluate whether c-CPE-NP were also able to transfect ovarian tumor cells in vivo, 2.5mg of c-CPE-NPs encapsulating the CMV GFP plasmid labeled with the Cy5 fluorescent dye (red fluorescent signal) were injected intraperitoneally in xenografts derived from the OSPC ARK-1 primary chemotherapy-resistant cell line. At different time points, mice were sacrificed, organs were excised and red fluorescent signal was visualized ex-vivo on the tumors as well as on control mice organs including kidney, spleen, liver and lungs.

As shown in figure 5A–B, tumor fluorescence peaked 12 hours after injection with nanoparticles and was found to be significantly higher than background fluorescence detected in healthy tissues and in tumors excised from non-injected mice (p=0.007). These results suggest a specific uptake of the c-CPE-NPs by ovarian cancer cells and indicate that c-CPE-NPs are capable of delivering DNA specifically to chemotherapy-resistant ovarian tumor cells in-vivo. These data also suggest that c-CPE-NPs are transported to the bloodstream through the peritoneal lymphatic system and are able to reach tumor sites prior to clearance by the reticulo-endothelial system (RES)(33–35). We believe that the relatively long retention of the c-CPE-NP in-vivo may be due to the presence of the polyethylene glycol (PEG) in the particles coating polymer that has been shown to significantly reduce particles uptake by macrophages(36). Importantly, the time required for the c-CPE-NP to deliver DNA to ovarian tumors (8–12 hours; figure 5A–B) corresponded to the time of the burst release of DNA from the c-CPE-NP which was evaluated in our DNA release profile experiments (12–72 hours; figure 2B, Supplementary figure 1 and Supplementary table 3). These findings suggest that the majority of the therapeutic DNA will be released from the c-CPE-NPs once particles are internalized into the targeted ovarian tumor cells.

Figure 5. c-CPE-NP transfection efficiency in vivo in ovarian tumor cells.

SCID mice harboring subcutaneous OSPC ARK-1 xenografts were injected intraperitoneally with 2.5mg of c-CPE-NP encapsulating the CMV GFP plasmid labeled to the Cy5 dye. Mice were sacrificed at different time points and organs including, kidney, liver, spleen, lungs and tumors (labeled from 1 to 5, respectively) were excised for histological examination and visualization using an In-Vivo FX-PRO imaging system (excitation/emission:550/635nm; exposure time 10 seconds). A and B, Tumors fluorescence peaks at 12 hours after particles’ injection and is significantly higher than fluorescence detected in healthy organs or tumors excised from control (ie, non-injected) mice (panel B; p=0.007). (C) Fluorescence microscopy images on tumor slides excised from mice 12 hours after treatment with c-CPE-NP encapsulating the CMV GFP plasmid labeled with the Cy5 dye. Most of the cells in which the DNA was successfully delivered by the c-CPE-NP (lower panel, red image) also expressed GFP (lower panel, green and merge images). Tumors excised from non-injected control mice were visualized using the same parameters to evaluate tissue autofluorescence (upper panel).

To evaluate whether the successful delivery of DNA also resulted in the transfection of tumor cells in-vivo, immunofluorescence was used to visualize GFP-expressing cells on tumor slides derived from mice treated 12 hours before with the c-CPE-NP encapsulating the CMV GFP labeled with the Cy5 dye. As representatively shown in figure 5C lower panel, the majority of cells in which the DNA was successfully delivered by the c-CPE-NP (figure 5C, lower panel, red image) also expressed GFP (figure 5C, lower panel, green and merge images). Tumors excised from non-injected control mice were visualized using the same parameters to evaluate tissue auto-fluorescence (figure 5C, upper panel). These data confirmed the in-vitro results and suggest that the c-CPE coating confers a high tumor targeting specificity to the delivery system presented here.

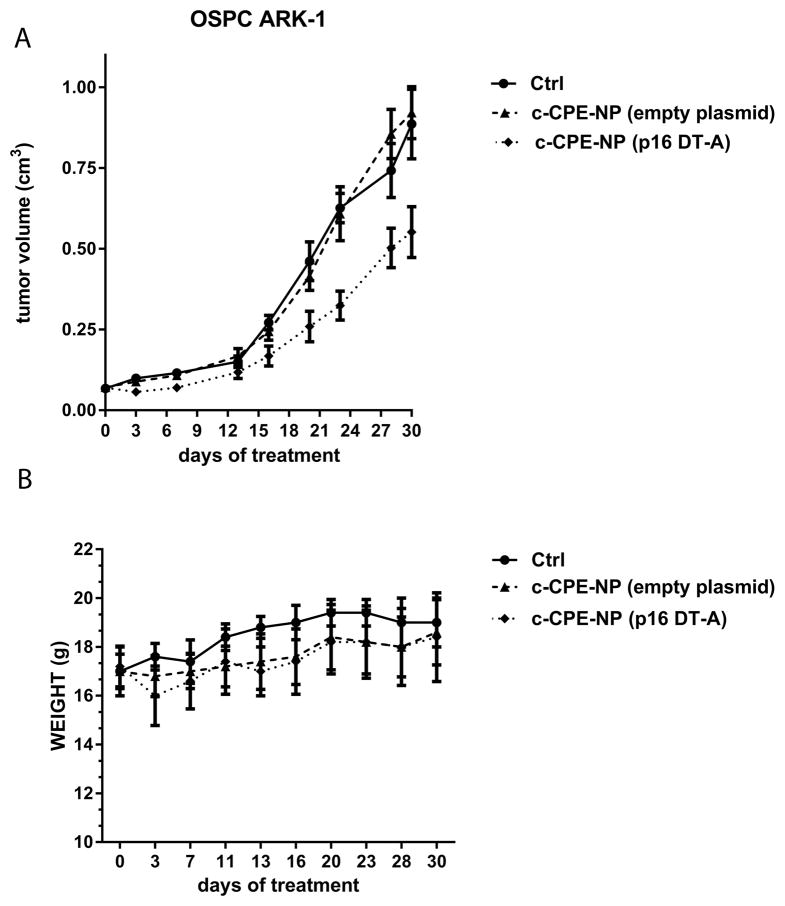

p16 DT-A c-CPE-NPs are effective in inhibiting ovarian tumor growth in-vivo

Finally, the therapeutic potential of p16 DTA c-CPE-NP was tested in xenografts derived from the primary chemotherapy-resistant ovarian cancer cell line OSPC ARK-1. During the therapeutic portion of this study, multiple (n= 8) IP injections of particles were administered due to the relatively low DNA loading into the c-CPE-NP (3.37±0.75μg/mg particles; figure 2B and Supplementary table 3). This strategy allowed for the delivery of a total dose of DNA to the tumor that has been previously described to be in the therapeutic range in gene therapy studies (between 50 and 100μg)(37, 38).

As shown in figure 6A and supplementary Figure 3, the treatment of xenografts with p16 DT-A c-CPE-NP was highly effective in reducing tumor growth and significantly increased overall survival when compared to control groups including mice treated with the vehicle and mice treated with c-CPE-NP encapsulating the empty plasmid (tumor volume at day 20 after first injection: mean±SEM=0.46±0.06, 0.41±0.043 and 0.26±0.047cm3 in the vehicle group, in the c-CPE-NP encapsulating the empty plasmid group and in the p16 DT-A c-CPE-NP group, respectively; p=0.029 for the vehicle versus the experimental group and p=0.041 for the NP control versus the experimental group). Importantly, the treatment of mice with the c-CPE-NP encapsulating the empty plasmid didn’t result in tumor growth inhibition when compared to the vehicle treated mice, suggesting that the therapeutic effect observed in the experimental group was specifically due to the activity of p16 DT-A. Furthermore, no significant weight loss or major organ toxicity at the time of a full, detailed gross necropsy were reported in any of the treated groups, suggesting extremely low- in-vivo intrinsic toxicity of the c-CPE-NP (figure 6B, p>0.05).

Figure 6. c-CPE-NP encapsulating the p16 DT-A plasmid are effective in inhibiting ovarian tumor growth in vivo.

Mice harboring subcutaneous OSPC ARK-1 derived chemotherapy-resistant ovarian cancer were treated IP with multiple doses of c-CPE-NP encapsulating the p16 DT-A plasmid starting one week after tumor implantation. Tumor sizes and mouse weights were monitored over the course of the entire experiment twice a week. (A) Treatment of mice with c-CPE-NP encapsulating the p16 DT-A plasmid significantly reduced tumor growth compared to controls including mice injected with the vehicle (ie, PBS) and mice treated with the same doses of c-CPE-NP encapsulating the empty plasmid. (B) No significant major organ toxicity or weight loss in mice was reported over the entire course of the study.

Discussion

Ovarian cancer remains the most lethal gynecologic malignancy in the USA and Europe(1). In this study we synthesized and characterized a blend of PBAE/PLGA nanoparticles (NP) modified with the carboxi-terminal domain of CPE(c-CPE-NP) and we tested their efficacy in delivering suicide gene therapy selectively to chemotherapy-resistant ovarian cancer cells in vitro as well as in vivo. As therapeutic DNA we encapsulated in the c-CPE-NP a plasmid encoding for the Diphteria Toxin subunit A (DT-A) under the transcriptional control of the p16 promoter.

High transfection capacity is essential for the effectiveness of a DNA delivery system. In a recent study by Mangraviti et al., PBAE-based nanoparticles encapsulating DNA encoding for the herpes simplex virus type I thymidine kinase (HSVtk) were synthesized and used in combination with ganciclovir (a prodrug activated by the HSVtk enzyme) for the treatment of brain tumor. When the immortalized F98 and 9L glioma cells were treated with these particles, 100% of cell killing was achieved, indicating an extremely high transfection efficiency of the delivery system(39). Here we show that the treatment of ovarian tumor cells with p16 DT-A c-CPE-NP induced up to 40% of cell death, suggesting a lower transfection efficiency in our human system. However, several studies reported that primary tumor cells (i.e., OSPC ARK-1 and CC ARK-1) are transfected with much less efficiency than immortalized cell lines, regardless of the transfection technique used (i.e., Lipofectamine 2000, FuGENE HD or electroporation)(40–42). Moreover the high cell mortality found by Mangreviti et al. was also partially influenced by the well described bystander effect that characterizes the inducible HSVtk/GCV system(43). Taken together these data using primary human tumors suggest that p16 DT-A c-CPE-NP are highly efficient in killing chemotherapy-resistant ovarian cancer cells in vitro.

Importantly, we further showed that c-CPE-NP are also able to efficiently transfect tumor cells in vivo within few hours after injection and that treatment of tumor bearing mice with p16 DTA-c-CPE-NP result in a significant inhibition of tumor growth.

Low transfection efficiency and high toxicity are the major obstacles in gene therapy systems. PBAE polymer-blend nanoparticles have already been reported to have a high transfection capability and a strong safety profile when injected locally [i.e., intracranial administration through convection-enhanced delivery (CED)](39). Accordingly, our data demonstrate that IP injection of the c-CPE-NP resulted in the transfection of ovarian tumor cells in vivo without causing any evident signs of toxicity. Consistent with previous reports, once injected intraperitoneally, it is thought that c-CPE-NP can reach the lymphatic vasculature and subsequently be introduced in the bloodstream(33, 34). Because of their small size (~150 nm), the c-CPE-NP can flow through the capillary system and eventually reach the tumor(16). The in vivo data presented here clearly indicate that the amount of DNA successfully delivered to the tumor cells by the c-CPE-NP was sufficient to obtain a therapeutic effect.

Our preclinical results were obtained using a primary clear cell ovarian cancer cell line (ie, CC ARK-1) with a partial loss of TP53 function (ie, loss of heterozygosity) and a primary high grade serous ovarian cancer cell line (ie, OSPC ARK-1) harboring a wild type p53 gene by WES (Methods). While no significant differences in transfection efficiency and plasmid expression were detected in the p53 mutated vs p53 wild type cell lines using c-CPE-NP encapsulating the DT-A plasmid under the transcriptional control of the p16 promoter, since missense or activating p53 mutations are identified in a large number of high grade serous ovarian cancers, our results with OSPC ARK-1 may not be representative of the majority of ovarian serous carcinomas. Additional experiments with serous ovarian cancer cell lines that carry p53 mutations are therefore warranted.

In conclusion, we developed a novel dual-targeting system for the delivery of suicide gene therapy selectively to chemotherapy-resistant ovarian cancer cells in vitro as well as in vivo. The presence of c-CPE peptide on the surface of the PBAE/PLGA particles allowed specific binding to the claudin-3/-4 receptors which are highly differentially expressed in ovarian cancer cells. Importantly, the functionalization of the NP transporting the lethal DT-A plasmid in combination with the transcriptional control of the DT-A expression by the p16 promoter (i.e., a promoter specifically active in ovarian cancer cells) ensured the strong therapeutic efficacy and the high safety profile of this novel treatment modality. To our knowledge, this report represents the first preclinical evidence of a successful c-CPE-based dual-targeting gene therapy approach for the treatment of chemotherapy-resistant ovarian cancer in vitro and in vivo. Importantly, if the CPE-based DNA delivery system described here is proven successful in the treatment of ovarian cancer patients in clinical trials, it may have far-reaching effects for the field of oncology because it may also be considered for the experimental treatment of multiple other solid tumors found to overexpress claudin-3/-4 including pancreatic, breast and prostate cancers(44–47).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by R01 CA154460-01 and U01 CA176067-01A1 grants from NIH, the Deborah Bunn Alley Foundation, the Tina Brozman Foundation, the Women’s Health Research at Yale – The Ethel F. Donaghue Women’s Health Investigator Program at Yale, the Yale Cancer Center, the Discovery to Cure Foundation, the Guido Berlucchi Foundation and The Italian Ministry of Health Grant RF-2010-2313497 to ADS. This investigation was also supported by NIH Research Grant CA-16359 from the NCI to ADS and A Strategic Partnership Grant from the Michigan State University Foundation to EMS.

Footnotes

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:5–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.21254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boring CC, Squires TS, Tong T. Cancer statistics, 1993. CA Cancer J Clin. 1993;43:7–26. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.43.1.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goff BA, Mandel L, Muntz HG, Melancon CH. Ovarian carcinoma diagnosis. Cancer. 2000;89:2068–75. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20001115)89:10<2068::aid-cncr6>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coward JI, Middleton K, Murphy F. New perspectives on targeted therapy in ovarian cancer. Int J Womens Health. 2015;7:189–203. doi: 10.2147/IJWH.S52379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bignotti E, Tassi RA, Calza S, Ravaggi A, Bandiera E, Rossi E, et al. Gene expression profile of ovarian serous papillary carcinomas: identification of metastasis-associated genes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196:245e1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.10.874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Santin AD, Zhan F, Bellone S, Palmieri M, Cane S, Bignotti E, et al. Gene expression profiles in primary ovarian serous papillary tumors and normal ovarian epithelium: identification of candidate molecular markers for ovarian cancer diagnosis and therapy. Int J Cancer. 2004;112:14–25. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stewart JJ, White JT, Yan X, Collins S, Drescher CW, Urban ND, et al. Proteins associated with Cisplatin resistance in ovarian cancer cells identified by quantitative proteomic technology and integrated with mRNA expression levels. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2006;5:433–43. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M500140-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Casagrande F, Cocco E, Bellone S, Richter CE, Bellone M, Todeschini P, et al. Eradication of chemotherapy-resistant CD44+ human ovarian cancer stem cells in mice by intraperitoneal administration of Clostridium perfringens enterotoxin. Cancer. 2011;117:5519–28. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Santin AD, Cane S, Bellone S, Palmieri M, Siegel ER, Thomas M, et al. Treatment of chemotherapy-resistant human ovarian cancer xenografts in C.B-17/SCID mice by intraperitoneal administration of Clostridium perfringens enterotoxin. Cancer Res. 2005;65:4334–42. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McClane BA. An overview of Clostridium perfringens enterotoxin. Toxicon. 1996;34:1335–43. doi: 10.1016/s0041-0101(96)00101-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Katahira J, Inoue N, Horiguchi Y, Matsuda M, Sugimoto N. Molecular cloning and functional characterization of the receptor for Clostridium perfringens enterotoxin. J Cell Biol. 1997;136:1239–47. doi: 10.1083/jcb.136.6.1239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cocco E, Casagrande F, Bellone S, Richter CE, Bellone M, Todeschini P, et al. Clostridium perfringens enterotoxin carboxy-terminal fragment is a novel tumor-homing peptide for human ovarian cancer. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:349. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mosley M, Knight J, Neesse A, Michl P, Iezzi M, Kersemans V, et al. Claudin-4 SPECT Imaging Allows Detection of Aplastic Lesions in a Mouse Model of Breast Cancer. J Nucl Med. 2015;56:745–51. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.114.152496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cocco E, Shapiro EM, Gasparrini S, Lopez S, Schwab CL, Bellone S, et al. Clostridium perfringens enterotoxin C-terminal domain labeled to fluorescent dyes for in vivo visualization of micrometastatic chemotherapy-resistant ovarian cancer. Int J Cancer. 2015;137:2618–29. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang YH, Zugates GT, Peng W, Holtz D, Dunton C, Green JJ, et al. Nanoparticle-delivered suicide gene therapy effectively reduces ovarian tumor burden in mice. Cancer Res. 2009;69:6184–91. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Danhier F, Ansorena E, Silva JM, Coco R, Le Breton A, Preat V. PLGA-based nanoparticles: an overview of biomedical applications. J Control Release. 2012;161:505–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2012.01.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fields RJ, Cheng CJ, Quijano E, Weller C, Kristofik N, Duong N, et al. Surface modified poly(beta amino ester)-containing nanoparticles for plasmid DNA delivery. J Control Release. 2012;164:41–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2012.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Witkiewicz AK, Knudsen KE, Dicker AP, Knudsen ES. The meaning of p16(ink4a) expression in tumors: functional significance, clinical associations and future developments. Cell Cycle. 2011;10:2497–503. doi: 10.4161/cc.10.15.16776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cancer Genome Atlas Research N. Integrated genomic analyses of ovarian carcinoma. Nature. 2011;474:609–15. doi: 10.1038/nature10166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dong Y, Walsh MD, McGuckin MA, Gabrielli BG, Cummings MC, Wright RG, et al. Increased expression of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2 (CDKN2A) gene product P16INK4A in ovarian cancer is associated with progression and unfavourable prognosis. Int J Cancer. 1997;74:57–63. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19970220)74:1<57::aid-ijc10>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liew PL, Hsu CS, Liu WM, Lee YC, Lee YC, Chen CL. Prognostic and predictive values of Nrf2, Keap1, p16 and E-cadherin expression in ovarian epithelial carcinoma. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8:5642–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Milea A, George SH, Matevski D, Jiang H, Madunic M, Berman HK, et al. Retinoblastoma pathway deregulatory mechanisms determine clinical outcome in high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma. Mod Pathol. 2014;27:991–1001. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2013.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nazlioglu HO, Ercan I, Bilgin T, Ozuysal S. Expression of p16 in serous ovarian neoplasms. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2010;31:312–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lynn DM, Anderson DG, Putnam D, Langer R. Accelerated discovery of synthetic transfection vectors: parallel synthesis and screening of a degradable polymer library. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:8155–6. doi: 10.1021/ja016288p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Richter CE, Cocco E, Bellone S, Silasi DA, Ruttinger D, Azodi M, et al. High-grade, chemotherapy-resistant ovarian carcinomas overexpress epithelial cell adhesion molecule (EpCAM) and are highly sensitive to immunotherapy with MT201, a fully human monoclonal anti-EpCAM antibody. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;203:582e1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.07.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Takahashi A, Komiya E, Kakutani H, Yoshida T, Fujii M, Horiguchi Y, et al. Domain mapping of a claudin-4 modulator, the C-terminal region of C-terminal fragment of Clostridium perfringens enterotoxin, by site-directed mutagenesis. Biochem Pharmacol. 2008;75:1639–48. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2007.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rangel LB, Agarwal R, D’Souza T, Pizer ES, Alo PL, Lancaster WD, et al. Tight junction proteins claudin-3 and claudin-4 are frequently overexpressed in ovarian cancer but not in ovarian cystadenomas. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:2567–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Takashima Y, Saito R, Nakajima A, Oda M, Kimura A, Kanazawa T, et al. Spray-drying preparation of microparticles containing cationic PLGA nanospheres as gene carriers for avoiding aggregation of nanospheres. Int J Pharm. 2007;343:262–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2007.05.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kreitman RJ, Hassan R, Fitzgerald DJ, Pastan I. Phase I trial of continuous infusion anti-mesothelin recombinant immunotoxin SS1P. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:5274–9. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stein SM, Tiersten A, Hochster HS, Blank SV, Pothuri B, Curtin J, et al. A phase 2 study of oxaliplatin combined with continuous infusion topotecan for patients with previously treated ovarian cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2013;23:1577–82. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0b013e3182a809e0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Benhar I, Reiter Y, Pai LH, Pastan I. Administration of disulfide-stabilized Fv-immunotoxins B1(dsFv)-PE38 and B3(dsFv)-PE38 by continuous infusion increases their efficacy in curing large tumor xenografts in nude mice. Int J Cancer. 1995;62:351–5. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910620320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Martins YC, Clemmer L, Orjuela-Sanchez P, Zanini GM, Ong PK, Frangos JA, et al. Slow and continuous delivery of a low dose of nimodipine improves survival and electrocardiogram parameters in rescue therapy of mice with experimental cerebral malaria. Malar J. 2013;12:138. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-12-138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moghimi SM, Parhamifar L, Ahmadvand D, Wibroe PP, Andresen TL, Farhangrazi ZS, et al. Particulate Systems for Targeting of Macrophages: Basic and Therapeutic Concepts. Journal of Innate Immunity. 2012;4:509–28. doi: 10.1159/000339153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ordóñez-Gutiérrez L, Re F, Bereczki E, Ioja E, Gregori M, Andersen AJ, et al. Repeated intraperitoneal injections of liposomes containing phosphatidic acid and cardiolipin reduce amyloid-β levels in APP/PS1 transgenic mice. Nanomedicine: Nanotechnology, Biology and Medicine. 2015;11:421–30. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2014.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sadat Tabatabaei Mirakabad F, Nejati-Koshki K, Akbarzadeh A, Yamchi MR, Milani M, Zarghami N, et al. PLGA-based nanoparticles as cancer drug delivery systems. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014;15:517–35. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2014.15.2.517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tang N, Du G, Wang N, Liu C, Hang H, Liang W. Improving penetration in tumors with nanoassemblies of phospholipids and doxorubicin. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99:1004–15. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djm027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Anderson DG, Peng W, Akinc A, Hossain N, Kohn A, Padera R, et al. A polymer library approach to suicide gene therapy for cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:16028–33. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407218101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Castillo-Rodriguez RA, Arango-Rodriguez ML, Escobedo L, Hernandez-Baltazar D, Gompel A, Forgez P, et al. Suicide HSVtk gene delivery by neurotensin-polyplex nanoparticles via the bloodstream and GCV Treatment specifically inhibit the growth of human MDA-MB-231 triple negative breast cancer tumors xenografted in athymic mice. PLoS One. 2014;9:e97151. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0097151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mangraviti A, Tzeng SY, Kozielski KL, Wang Y, Jin Y, Gullotti D, et al. Polymeric nanoparticles for nonviral gene therapy extend brain tumor survival in vivo. ACS Nano. 2015;9:1236–49. doi: 10.1021/nn504905q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hamm A, Krott N, Breibach I, Blindt R, Bosserhoff AK. Efficient transfection method for primary cells. Tissue Eng. 2002;8:235–45. doi: 10.1089/107632702753725003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Han NR, Lee H, Baek S, Yun JI, Park KH, Lee ST. Delivery of episomal vectors into primary cells by means of commercial transfection reagents. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2015;461:348–53. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li F, Yamaguchi K, Okada K, Matsushita K, Enatsu N, Chiba K, et al. Efficient transfection of DNA into primarily cultured rat sertoli cells by electroporation. Biol Reprod. 2013;88:61. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.112.106260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mesnil M, Yamasaki H. Bystander effect in herpes simplex virus-thymidine kinase/ganciclovir cancer gene therapy: role of gap-junctional intercellular communication. Cancer Res. 2000;60:3989–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Facchetti F, Lonardi S, Gentili F, Bercich L, Falchetti M, Tardanico R, et al. Claudin 4 identifies a wide spectrum of epithelial neoplasms and represents a very useful marker for carcinoma versus mesothelioma diagnosis in pleural and peritoneal biopsies and effusions. Virchows Arch. 2007;451:669–80. doi: 10.1007/s00428-007-0448-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kominsky SL, Tyler B, Sosnowski J, Brady K, Doucet M, Nell D, et al. Clostridium perfringens enterotoxin as a novel-targeted therapeutic for brain metastasis. Cancer Res. 2007;67:7977–82. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Long H, Crean CD, Lee WH, Cummings OW, Gabig TG. Expression of Clostridium perfringens enterotoxin receptors claudin-3 and claudin-4 in prostate cancer epithelium. Cancer Res. 2001;61:7878–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Michl P, Buchholz M, Rolke M, Kunsch S, Lohr M, McClane B, et al. Claudin-4: a new target for pancreatic cancer treatment using Clostridium perfringens enterotoxin. Gastroenterology. 2001;121:678–84. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.27124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.