Abstract

O-GlcNAcylation is a dynamic form of protein glycosylation which involves the addition of β-D-N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) via an O-linkage to serine or threonine residues of nuclear, cytoplasmic, mitochondrial and transmembrane proteins. The two enzymes responsible for O-GlcNAc cycling are O-GlcNAc transferase (OGT) and O-GlcNAcase (OGA); their expression and activities in brain are age dependent. More than 1000 O-GlcNAc protein targets have been identified which play critical roles in many cellular processes. In mammalian brain, O-GlcNAc modification of Tau decreases its phosphorylation and toxicity, suggesting a neuroprotective role of pharmacological elevation of brain O-GlcNAc for Alzheimer’s disease treatment. Other observations suggest that elevating O-GlcNAc levels may decrease protein clearance or induce apoptosis. This review highlights some of the key findings regarding O-GlcNAcylation in models of neurodegenerative diseases.

Introduction

The discovery of protein O-GlcNAcylation dates back to the 1980s, in which Torres and Hart et al described a novel single carbohydrate N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc)-peptide linkage on monocyte cell surface [1]. Later studies defined it as the addition of GlcNAc via an O-linkage on serine and threonine residues of target proteins [1, 2]. In contrast to classical O- and N-linked glycosylation, which mainly occurs on endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi resident proteins, O-GlcNAcylation has been detected on proteins in all the major compartments of the cell including the membranes, cytoplasm, mitochondria and nucleus [3].

O-GlcNAcylation is often referred to as a nutrient sensitive pathway and this nutrient sensitivity is attributed to the levels of UDP-GlcNAc, which is dependent on flux through the hexosamine biosynthetic pathway (HBP). Approximately 2–5% of all glucose entering into the cell is channeled into the HBP to generate UDP-GlcNAc [4]. However, this estimate is based on cultured adipocytes; consequently, the relative flux of glucose into the HBP in highly metabolic tissues such as the brain is not known. Glutamine–fructose-6-phosphate amido transferase (GFAT), which converts fructose-6-phosphate to glucosamine-6-phosphate, is the rate limiting enzyme of the (HBP). GFAT is feedback inhibited by UDP-GlcNAc, the major end product of the HBP. O-GlcNAcylation of many proteins is consequently affected by the changes in UDP-GlcNAc levels [4].

Mammalian cells subjected to various cellular stresses, including oxidative, osmotic and chemical stress, exhibit increased global O-GlcNAcylation. Thus, O-GlcNAcylation is a unique metabolic signaling mechanism allowing cells to detect and respond to stress and thereby influence cell survival. However, whether changes in this post-translational modification promote cell death or cell survival depends highly on the cellular context. In this review we will summarize mechanisms and regulation of O-GlcNAc cycling, as well as what is known about its involvement in neurodegenerative diseases.

O-GlcNAc Transferase (OGT) and O-GlcNAcase (OGA)

Despite being an abundant post-translational modification, O-GlcNAcylation is regulated by the concerted action of only two enzymes O-GlcNAc transferase (OGT) and O-GlcNAcase (OGA) [5] (Fig.1). OGT catalyzes the addition of N-acetylglucosamine to target proteins [2] and is highly conserved from C. elegans to humans, including plants [6, 7]. Although OGT mRNA is ubiquitously expressed in all tissues, the highest levels of OGT mRNA are found in pancreas followed by brain compared to other organs [6–8]. Cytosolic OGT activity is 10 times higher in brain compared to muscle, adipose, heart, and liver [9]. The Ogt gene is localized at Xq13 and its deletion in mice causes embryonic lethality [8]. Parkinsonian-dystonia (DYT3) has been mapped to the X chromosomal region that includes the Ogt locus [10]. A rare type of glycosylation has been recently reported, which involves the O-GlcNAc modification of extracellular proteins containing folded EGF-like domains such as Notch receptors [11]. This O-GlcNAc modification is catalyzed by a distinct OGT isoform, endoplasmic reticulum-resident O-GlcNAc transferase, EOGT [12].

Fig.1. Nutrient-dependent and enzymatically-catalyzed addition and removal of O-GlcNAc from proteins.

UDP-GlcNAc is synthesized from glucose via the hexose biosynthetic pathway (HBP), which also requires glutamine, acetyl-CoA and uridine from protein, lipid, and nucleotide metabolism respectively. Attachment of O-GlcNAc to proteins is catalyzed by O-GlcNAc transferase (OGT), and the removal catalyzed by O-GlcNAcase (OGA).

OGA, the enzyme that removes O-GlcNAc from proteins, was first isolated from crude cellular extracts and was initially named hexosaminidase C to distinguish it from the lysosomal β-hexosaminidase [13, 14]. Whereas lysosomal hexosaminidases have an acidic pH optimum and can use both O-linked N-acetylgalactosamine (O-GalNAc) and O-GlcNAc as their substrates, OGA has a neutral pH optimum and selectively uses O-GlcNAc as its substrate but not O-GalNAc [15]. OGA is expressed from a single gene, which is annotated as meningioma expressed antigen 5 (MGEA5) and is expressed at the highest levels in pancreas, brain, and thymus, with lesser amounts in other tissues [15], the highest levels of OGA transcripts are also found in brain [15]. OGA is localized to the long arm of chromosome 10(10q24), a region highly associated with late-onset Alzheimer's disease (AD) [16].

O-GlcNAcylated proteins, OGT and OGA are abundant throughout the brain, including the synapses and post-synaptic density preparations [17–22]. In hippocampus, O-GlcNAcylated proteins are present in pyramidal cells, GABAergic interneurons, and astrocytes [20]. In cerebellar cortex, OGT mRNA and protein, as well as O-GlcNAcylated proteins are expressed in neurons, especially in Purkinje cells. Using immuno-gold labeling, it has been found that within Purkinje cells, OGT and O-GlcNAcylated proteins are present in nucleus, cytoplasmic matrix, and around microtubules in dendrites. Presynaptic terminals, especially around synaptic vesicles, have more OGT and O-GlcNAcylated proteins than postsynaptic terminals [23]. In adult rat brains, OGT and OGA immunostaining show similar patterns with higher staining in the dorsal parietal cortex and hippocampus than other brain regions [21]. Regarding age dependent O-GlcNAcylation, in the Wistar rats, various isoforms of OGT and OGA proteins are differentially expressed with age. ncOGT (116 kDa) decreases from Embryonic Day 15 (E15)-Postnatal 15 (P15) to postnatal 3 months and continues to decrease to postnatal 2 years, while sOGT (70 kDa) increases and peaks at postnatal 3–6 months. OGT activity as assayed using nucleoporin p62 as a substrate is increased from E19 to P30. OGA full-length has 2 immunoreactive species with an upper band (~150 kDa) exhibiting increased levels with age and a lower band (~120 kDa) exhibiting decreased levels with age and the sum peaked at P5 and decrease with age and OGA nuclear variant (~80 kDa) only expressed at embryonic stages. Overall OGA activity is lower at P15-postnatal 2 year compared to E15-P5 using p-nitrophenyl-N-acetyl-b-D-glucosaminide as a substrate. O-GlcNAc levels are decreased significantly from E15 to postnatal 5 days to 6 months, and slightly increased from 6 months to 2 years [21]. Conversely studies in Brown-Norway rats found that brain O-GlcNAc levels increased ~30% in 24-month compared to 5-month old rats, without any changes in the OGT or OGA mRNA expression [24]. Collectively, these studies suggest an involvement of O-GlcNAc modification in diverse brain functions throughout the lifespan.

Regulation of OGT and OGA

OGT protein consists of two major domains. The N-terminal domain is comprised of several tetratricopeptide (TPR) repeats and the C-terminal domain exhibits glycosyltransferase activity and binds UDP-GlcNAc. The TPR repeats serve as protein:protein docking sites for substrate targeting proteins [6, 25]. Surprisingly, OGT itself undergoes O-GlcNAc modification, as well as tyrosine phosphorylation; the impact of these modifications on OGT activity is currently unknown [6]. However, S-nitrosation of OGT strongly inhibits its catalytic activity whereas de-nitrosation activates it, leading to protein hyper-O-GlcNAcylation [26]. OGT mRNA undergoes alternative splicing giving rise to transcripts encoding distinct OGT isoforms, which includes nucleocytoplasmic isoform (ncOGT), the mitochondrial isoform (mOGT), and the short isoform (sOGT) [27, 28]. These different OGT isoforms differ in their N-terminal sequence: the ncOGT isoform (116 kDa) contains 12 tetratricopeptide repeats (TPRs), the mOGT (103 kDa) contains 9 TPRs, and a mitochondrial targeting sequence, while the sOGT (75 kDa) contains 2 TPRs [27]. This difference in number of TPRs in each isoform may confer differential substrate specificity [29].

OGA is also a dual function enzyme with both an N-terminal catalytic domain and a C-terminal histone acetyltransferase (HAT) domain. Although it has been shown that O-GlcNAcase has histone acetyltransferase activity in vitro 30], this remains an area of controversy [31]. OGA is a caspase-3 substrate, and during apoptosis, OGA is cleaved by caspace-3 without affecting its glycosidase activity [32]. Similar to OGT, alternative gene splicing produces two OGA isoforms, a long isoform (OGA-L, 110KDa) and a short isoform (OGA-S, 75KDa). These isoforms differ in their localization within the cell, OGA-L is found predominantly in the cytoplasm [33], whereas OGA-S exhibits nuclear [33] and lipid-droplet-associated localization [34]. The OGA-S exhibits six times lower hexosaminidase activity compared to OGA-L [33, 34]. OGA expression is also regulated by micro RNA (miRNA), which are endogenous small RNAs (~22 nucleotides) that play key regulatory roles in modulating gene expression by ultimately inhibiting translation of their target mRNAs [35]. In neonatal rat cardiomyocytes, miR-539 significantly decreases OGA expression and consequently increases O-GlcNAcylation [36]. The role of miRNAs in regulating either OGA or OGT in the brain remains to be determined.

Identification of O-GlcNAcylated proteins

Proteomics studies of mouse and human brains have identified more than 1000 protein O-GlcNAcylation targets, which play critical roles in many cellular processes, including signal transduction, protein degradation, and regulation of gene expression [19, 37, 38]. The identification of O-GlcNAc modified proteins began with classical biochemical assays, which involved the use of tritiated UDP-Galactose [1]. Tritiated-galactose is incorporated into the O-GlcNAc residues on proteins by the action of β1–4-galactosyltransferase (GalT), which allows the detection of modified proteins by autoradiography. Many proteins have been shown to be O-GlcNAcylated, including RNA polymerase II, amyloid precursor protein, c-Myc, nitric oxide synthase, synapsin I, GluA2 AMPA receptor subunits and tau by these traditional biochemical methods [20, 39]. To identify O-GlcNAc modifications on neuronal proteins, Vosseller and co-workers used enrichment of the glycopeptides by lectin weak affinity chromatography (LWAC) and mass spectrometry [19]. Using this approach about 500 unique proteins were identified from post-synaptic density preparation of mouse brain. The identified proteins included proteins involved in vesicle docking and fusion (Bassoon) [40], maintenance of post-synaptic cytoskeletal structure (Ankyrin G) and those involved in signal transduction (Shank 2).

Antibodies including CTD 110.6 [41] and RL2 [42] have also been used for immunoprecipitation to enrich O-GlcNAcylated proteins to aid their identification. Other methods used mild β-elimination followed by Michael addition of dithiothreitol (DTT) or biotin pentylamine (BAP) to tag O-GlcNAc sites. Enrichment via affinity chromatography and site identification by LC-MS/MS can be achieved [43]. Chemo-enzymatic methods have also been employed for the high-throughput analysis of O-GlcNAc protein targets from the mammalian brain [18]. This strategy involves the use of galactosyltransferase enzyme to selectively label O-GlcNAc proteins with a ketone-biotin tag. Low-abundant O-GlcNAc peptides can be enriched by using the tag [18, 44]. With advancements in the mass spectrometry techniques, key proteins involved in neuronal and brain functions have been identified, including synaptic plasticity, synaptic vesicle trafficking, and axonal branching [17, 19, 45, 46]. Transcriptional activity of cyclic-AMP response element binding protein (CREB) is regulated by O-GlcNAcylation through modification of Ser40, which inhibits basal- and activity-induced CREB-mediated transcription by impairing its interaction with its transcriptional coactivator, CRTC2 [17]. In addition, a recent study demonstrated that mitochondrial motor adaptor protein Milton is a target of OGT. By regulating Milton O-GlcNAcylation, OGT modulates the mitochondrial dynamics in neurons based on nutrient availability [47]. According to published reports, about 40% of all neuronal proteins and 19% of synaptosome proteins are O-GlcNAcylated [37]. O-GlcNAc modified proteins also include proteins such as α-synuclein, a component of Lewy bodies involved in the pathogenesis of Parkinson’s disease (PD), tau, a protein involved in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) [48] as well as superoxide dismutase (SOD), a protein involved in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) [49], and the GluA2 subunit of AMPARs which mediates a novel form of long-term depression at hippocampal synapses [20].

O-GlcNAcylation and Alzheimer’s disease

The discovery of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) dates back to 1906, when a German physician, Alois Alzheimer linked clinical symptoms to autopsy results of Auguste D., a patient who had memory loss, language problems, and psychological changes [50]. Since then, AD is described as a progressive neurodegenerative disorder that affects memory and learning. Age is the most important known risk factor for the development of AD [51].

The pathological hallmarks of AD include neurofibrillary tangles (NFT) and amyloid beta (Aβ) plaques, which are accompanied by synaptic loss and dementia [50]. Studies based on Positron emission tomography (PET) using 2-fluoro-2-deoxy-glucopyranose revealed that cerebral glucose metabolism declines progressively with normal aging and is more impaired in AD [52]. Furthermore, the PET data is supported by studies in various transgenic AD mouse models which also show impairment in glucose metabolism within brain [53, 54]. The involvement of glucose metabolism in AD has also been supported by the observation that Type II diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is a risk factor for AD [55], and impaired glucose metabolism correlates with dementia severity in AD [56].

The mechanism by which impaired glucose metabolism drives AD pathologies in brain remains unclear; however, several investigators have attributed it to impaired O-GlcNAc cycling [57–59]. In principle, decreased glucose metabolism would lead to reduced flux through the HBP, lower levels of UDP-GlcNAc leading to lower O-GlcNAcylation. It has been noted that amyloid precursor protein (APP), is O-GlcNAc modified [60]. APP is processed by three different proteases: α, β, and γ secretase complex [61–64] (Fig.2). The processing of APP by α-secretase in the extracellular domain of APP is non-amyloidogenic [65] whereas cleavage in this domain by β-secretase is amyloidogenic [66]. APP cleavage by α-secretase at the extracellular domain generates a soluble fragment sAPPα, and a membrane bound C-terminal fragment, APP-CTFα [61]. APP-CTFα is further cleaved by γ-secretase in the transmembrane region to produce the non-amyloidogenic product, p3, and the APP intracellular domain, AICD [65]. In contrast, APP cleavage by β-secretase at the extracellular domain produces the soluble sAPPβ fragment and the membrane bound APP-CTFβ [62]. Amyloid-β peptide (Aβ40 or Aβ42), together with the AICD are then produced by γ-secretase [66]. It has been demonstrated that pharmacological [67, 68] or genetic [68] interventions that enhance O-GlcNAcylation increase non-amyloidogenic α-secretase processing, resulting in increased levels of the neuroprotective sAPPα fragment and decreased Aβ secretion (Fig.2). Hyper-O-GlcNAcylation induced by an OGA inhibitor, NButGTA, in the 5xFAD amyloid-β mouse model, decreased levels of Aβ40 and Aβ42 peptides in the brain, decreased plaque formation, and improved cognition [69]. These data suggested that O-GlcNAc cycling can be a therapeutic target against AD.

Fig.2. O-GlcNAcylation of APP.

APP can be cleaved by either α-secretase or β-secretase. When APP is cleaved by α-secretase, a soluble N-terminal fragment (sAPPα) and a C-terminal fragment (CTFα) are produced, the membrane bound fragment CTFα is then further cleaved by γ-secretase, producing an N-terminal fragment (p3) and a membrane-bound C-terminal fragment (AICD, or APP intracellular domain). This pathway is non-amyloidogenic. In contrast, when APP is cleaved by β-secretase, a soluble N-terminal fragment (sAPPβ) and a membrane-bound C-terminal fragment (CTFβ) are produced, CTFβ is then further processed by γ-secretase, producing a membrane-bound C-terminal fragment (AICD) and a soluble N-terminal fragment (amyloid-β, or Aβ). Accumulation of Aβ in the extracellular space results in its aggregation to produce amyloid plaques. Amyloid plaques interfere with the normal neuronal and synaptic functions, ultimately leading to neuronal cell death. Increased O-GlcNAcylation has been shown to enhance non-amyloidogenic pathway and inhibit the amyloidogenic pathway, thus providing neuroprotection.

In addition to APP, tau purified from bovine brain has also been found to exhibit multiple terminal O-GlcNAc containing moieties [70]. The possibility of involvement of O-GlcNAcylation in Alzheimer’s disease etiology was speculated based on this study and prior studies that demonstrated APP O-GlcNAcylation [60] and evidence suggesting an increase of overall O-GlcNAcylation in detergent insoluble fractions [71]. It was also suggested that pharmacological means to increase tau O-GlcNAcylation may attenuate the formation of tau paired helical filament by decreasing tau phosphorylation [70]. Supporting tau O-GlcNAcylation can be protective, it has been shown that tau tangles isolated from AD patients are hyper-phosphorylated and hypo-O-GlcNAcylated [72], which is consistent with impaired brain glucose uptake/metabolism. During AD progression, tau becomes hyper-phosphorylated, which leads to its detachment from microtubules thereby increasing the amount of unbound heavily phosphorylated tau which then aggregates to form paired-helical filaments, give rise to the neurofibrillary tangles that are characteristic of AD [73] (Fig.3). Expression of glucose transporters GLUT1 and GLUT3 is significantly decreased in AD brain which correlates positively with decreased O-GlcNAcylation and negatively to tau phosphorylation [74].

Fig.3. O-GlcNAcylation of tau.

Due to hypometabolism of glucose, tau O-GlcNAcylation is decreased with concomitant increase in its phosphorylation. In the hyperphosphorylated state, tau is prone to aggregation leading to microtubule destabilization. This results in neuronal cell death. Hyper-O-GlcNAcylation, by inhibition of OGA using Thiamet-G, decreases Tau phosphorylation, increases its glycosylation, and makes Tau less susceptible to aggregation thereby providing neuroprotection.

Although there are evidence that both APP and tau can be O-GlcNAcylated, however, the issue of whether hypo-O-GlcNAcylation occurs and is causal to AD progression is still uncertain. Besides the early report of increased O-GlcNAcylation in detergent insoluble fractions using ELISA and HGAC85/39 antibodies [71], a recently study with CTD antibody also reported increased O-GlcNAcylation in AD brains, which was accompanied by decreased levels of OGA protein while OGT protein levels remain unaffected [75]. Nonetheless, efforts have been made to target tau O-GlcNAcylation and thereby controlling its aberrant phosphorylation. In PC12 cells overexpressing human tau, OGA inhibitor PUGNAc has been shown to elevate O-GlcNAc levels and decrease levels of phosphorylated tau [72]. OGT shRNA in HEK cells, and an inhibitor of the glutamine:fructose-6-P amidotransferase, DON, in rats, have been shown to decrease tau phosphorylation [76]. The protective effects of PUGNAc in vivo have also been demonstrated in a streptozotocin (STZ) rat model which exhibited abnormal tau phosphorylation [59]. O-GlcNAcase inhibitor, Thiamet-G, increased tau O-GlcNAcylation, decreased tau phosphorylation, inhibited formation of tau aggregates and decreased neuronal cell loss in vivo in JNPL3 mice [67, 77] (Fig.3). It should be noted that a neuroprotective role of O-GlcNAc independent of decreasing tau phosphorylation has also been found. In the Tau.P301L mouse model, chronic Thiamet-G treatment for 2.5 months attenuates breathing defects and behavioral deficits, and also increases animal survival, without changing the O-GlcNAcylated status of tau [68].

O-GlcNAcylation and Parkinson’s disease (PD)

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a neurodegenerative disease that is characterized by dopaminergic neuronal cell death and the presence of Lewy bodies in the substantial nigra pars compacta (SNpc) [78]. α-synuclein aggregation is a major hallmark in the pathogenesis of PD which is the main component of Lewy bodies [79]. Like aggregation prone tau protein, O-GlcNAcylation sites have been identified on α, β and γ-synuclein [22, 48]. α-synuclein is O-GlcNAc modified at threonine 64 and 72 in rat brain, and at serine 87 in humans [48, 80, 81]. α-synuclein can be O-GlcNAcylated in vitro and its O-GlcNAcylation at T72 decreases aggregation propensity and toxicity in cultured cells [82]. Furthermore, O-GlcNAcylation has recently been shown to decrease α-synuclein toxicity when added exogenously to cells in culture [82] (Fig.4). This work suggests that impaired O-GlcNAc cycling, associated with the aging process, might contribute to α-synuclein aggregation in PD. However, whether this impairment in O-GlcNAc cycling occurs in Parkinson’s disease brains has not been investigated.

Fig.4. O-GlcNAcylation of α-synuclein.

O-GlcNAcylation T72 on α-synuclein decreases the aggregation of the protein in vitro and also renders it less toxic to neuronal cells in culture.

O-GlcNAcylation, apoptosis, and autophagy

Hyper-O-GlcNAcylation induces neuronal apoptosis in an in vitro and in vivo model of cerebral ischemia via down regulation of AKT [83]. In a streptozotocin-induced diabetic retinopathy model, increased O-GlcNAcylation of NFκB is responsible for retinal ganglion cell death [84]. Global O-GlcNAcylation was increased, together with an increase in OGT, while there is decreased expression levels of OGA in diabetes model mice compared to control [84]. This may have important implications for the programmed cell death associated with hexosamine metabolism and neurodegeneration.

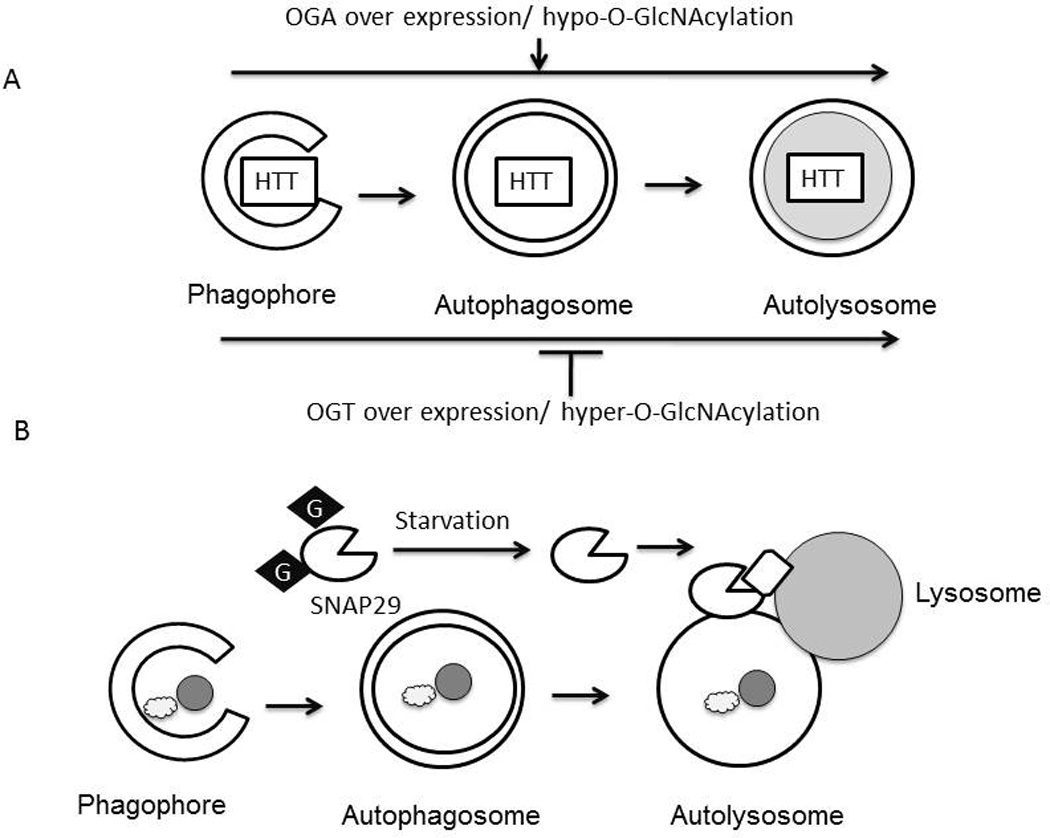

Autophagy is an intracellular degradation process mediated by lysosomes and it plays an important role in quality control of macromolecules and organelles [85]. Surprisingly, despite the fact that both autophagy and O-GlcNAcylation are highly conserved nutrient signaling and stress activated pathways, only limited studies explored the possibility that O-GlcNAcylation may be involved in regulating autophagy. It has been shown that key autophagic proteins BECN1 and BCL2 are targets of O-GlcNAcylation, and O-GlcNAcylation impairs autophagic signaling in the diabetic heart [86]. In C. elegans, mutations in O-GlcNAc cycling enzymes resulted in elevated levels of GFP::LGG-1 (homolog of Atg8 and LC3) upon starvation [87, 88]. In contrast to observations in tauopathy models, O-GlcNAcylation plays a detrimental role against mutant huntingtin toxicity in cells and fly models, as demonstrated by either overexpression of OGT or OGA, or by pharmacological alterations of O-GlcNAc levels using azaserine or glucosamine [89]. Decreasing O-GlcNAcylation enhances the fusion of autophagosomes with lysosomes, thereby elevating autophagic flux. This is associated with decreased mHtt aggregates in flies (Fig.5A) [89]. Autophagy inhibition may be mediated by O-GlcNAcylation of the SNARE protein SNAP29, inhibiting autophagosome-lysosome fusion and autophagic flux [90]. Indeed, OGT knockdown or mutating O-GlcNAc sites in SNAP29 enhances autophagosome-lysosome fusion and hence autophagic flux in C. elegans and HeLa cells (Fig.5B) [90]. In addition, O-GlcNAcylation may also inhibit the autophagic pathway, by decreasing ATG protein levels as well as the number of autophagosomes [91]. These studies suggest that O-GlcNAc cycling can regulate autophagy at multiple levels.

Fig.5. O-GlcNAcylation and autophagy.

A) Hypo-O-GlcNAcylation by overexpression of OGA in Neuro2A cells enhanced autophagic clearance of mutant Huntingtin (HTT), and attenuated toxicity. Hyper-O-GlcNAcylation by overexpression of OGT suppressed autophagic degradation of mutant HTT and enhanced toxicity. B) Autophagosomes form when double membraned vesicles encircle lipids, proteins or organelles. O-GlcNAcylation of SNAP-29 by O-GlcNAc transferase (OGT) inhibits fusion between the autophagosome and lysosome. Under starvation conditions SNAP-29 O-GlcNAcylation is decreased, which can activate autophagosome-lysosome fusion.

Conclusions and future perspectives

While the focus of this review is on the role of O-GlcNAcylation in neurodegenerative diseases, it should be noted that acute changes in O-GlcNAc levels altered learning and memory in both in vitro and in vivo models [20]. This emphasizes the fact that O-GlcNAc cycling plays an important role in normal neuronal function and that it is dysregulation of this pathway that contributes to disease. Future investigations into protein O-GlcNAcylation and neuronal signaling mechanisms need to further identify specific O-GlcNAcylated amino acids in various proteins in physiological and pathological conditions. How specific O-GlcNAcylation impacts protein function will need to be determined. Identifications of the factors involved in regulating OGT and OGA activity, such as epigenetic, transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulation, redox signaling, and protein-protein interactions, are also needed. Understanding of regulation of O-GlcNAcylation and specificity of O-GlcNAcylation will help define their beneficial and harmful effects in the central nervous system and potentially provide novel approaches for targeted interventions and therapies against neurodegeneration.

Highlights.

Protein O-GlcNAcylation is regulated by OGT and OGA

More than 1000 proteins have been identified to be O-GlcNAcylated

OGT, OGA, and O-GlcNAcylated proteins are abundant in the brain

O-GlcNAcylation of Tau, APP, Huntingtin, and α-synuclein regulate their toxicity

O-GlcNAcylation of SNAP-29 regulates autophagy

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by UAB AMC21 reload multi-investigator grant (VDU, JC, JZ); HL101192, HL-110366, (JC), R01NS076312 (JC, LM) and NIHR01-NS064090 (JZ).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Torres CR, Hart GW. Topography and polypeptide distribution of terminal N-acetylglucosamine residues on the surfaces of intact lymphocytes. Evidence for O-linked GlcNAc. J Biol Chem. 1984;259(5):3308–3317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haltiwanger RS, Holt GD, Hart GW. Enzymatic addition of O-GlcNAc to nuclear and cytoplasmic proteins. Identification of a uridine diphospho-N-acetylglucosamine:peptide beta-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase. J Biol Chem. 1990;265(5):2563–2568. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Varki A, Freeze HH, Gagneux P. Evolution of Glycan Diversity. In: Varki A, et al., editors. Essentials of Glycobiology. California.: Cold Spring Harbor (NY): Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2009. The Consortium of Glycobiology Editors, La Jolla. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marshall S, Bacote V, Traxinger RR. Discovery of a metabolic pathway mediating glucose-induced desensitization of the glucose transport system. Role of hexosamine biosynthesis in the induction of insulin resistance. J Biol Chem. 1991;266(8):4706–4712. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kreppel LK, Hart GW. Regulation of a cytosolic and nuclear O-GlcNAc transferase. Role of the tetratricopeptide repeats. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(45):32015–32022. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.45.32015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kreppel LK, Blomberg MA, Hart GW. Dynamic glycosylation of nuclear and cytosolic proteins. Cloning and characterization of a unique O-GlcNAc transferase with multiple tetratricopeptide repeats. J Biol Chem. 1997;272(14):9308–9315. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.14.9308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lubas WA, et al. O-Linked GlcNAc transferase is a conserved nucleocytoplasmic protein containing tetratricopeptide repeats. J Biol Chem. 1997;272(14):9316–9324. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.14.9316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shafi R, et al. The O-GlcNAc transferase gene resides on the X chromosome and is essential for embryonic stem cell viability and mouse ontogeny. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97(11):5735–5739. doi: 10.1073/pnas.100471497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Okuyama R, Marshall S. UDP-N-acetylglucosaminyl transferase (OGT) in brain tissue: temperature sensitivity and subcellular distribution of cytosolic and nuclear enzyme. J Neurochem. 2003;86(5):1271–1280. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01939.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nemeth AH, et al. Refined linkage disequilibrium and physical mapping of the gene locus for X-linked dystonia-parkinsonism (DYT3) Genomics. 1999;60(3):320–329. doi: 10.1006/geno.1999.5929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matsuura A, et al. O-linked N-acetylglucosamine is present on the extracellular domain of notch receptors. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(51):35486–35495. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806202200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sakaidani Y, et al. O-linked-N-acetylglucosamine modification of mammalian Notch receptors by an atypical O-GlcNAc transferase Eogt1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012;419(1):14–19. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.01.098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Braidman I, et al. Characterisation of human N-acetyl-beta-hexosaminidase C. FEBS Lett. 1974;41(2):181–184. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(74)81206-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Overdijk B, et al. Isolation and further characterization of bovine brain hexosaminidase C. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1981;659(2):255–266. doi: 10.1016/0005-2744(81)90052-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gao Y, et al. Dynamic O-glycosylation of nuclear and cytosolic proteins: cloning and characterization of a neutral, cytosolic beta-N-acetylglucosaminidase from human brain. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(13):9838–9845. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010420200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bertram L, et al. Evidence for genetic linkage of Alzheimer's disease to chromosome 10q. Science. 2000;290(5500):2302–2303. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5500.2302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rexach JE, et al. Dynamic O-GlcNAc modification regulates CREB-mediated gene expression and memory formation. Nat Chem Biol. 2012;8(3):253–261. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khidekel N, et al. Exploring the O-GlcNAc proteome: direct identification of O-GlcNAc-modified proteins from the brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(36):13132–13137. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403471101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vosseller K, et al. O-linked N-acetylglucosamine proteomics of postsynaptic density preparations using lectin weak affinity chromatography and mass spectrometry. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2006;5(5):923–934. doi: 10.1074/mcp.T500040-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Taylor EW, et al. O-GlcNAcylation of AMPA receptor GluA2 is associated with a novel form of long-term depression at hippocampal synapses. J Neurosci. 2014;34(1):10–21. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4761-12.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu Y, et al. Developmental regulation of protein O-GlcNAcylation, O-GlcNAc transferase, and O-GlcNAcase in mammalian brain. PLoS One. 2012;7(8):e43724. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cole RN, Hart GW. Cytosolic O-glycosylation is abundant in nerve terminals. J Neurochem. 2001;79(5):1080–1089. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00655.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Akimoto Y, et al. Localization of the O-GlcNAc transferase and O-GlcNAc-modified proteins in rat cerebellar cortex. Brain Res. 2003;966(2):194–205. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)04158-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fülöp N, et al. Aging leads to increased levels of protein O-linked N-acetylglucosamine in heart, aorta, brain and skeletal muscle in Brown-Norway rats. Biogerontology. 2008;9(3):139–151. doi: 10.1007/s10522-007-9123-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Iyer SP, Hart GW. Roles of the tetratricopeptide repeat domain in O-GlcNAc transferase targeting and protein substrate specificity. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(27):24608–24616. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300036200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ryu IH, Do SI. Denitrosylation of S-nitrosylated OGT is triggered in LPS-stimulated innate immune response. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2011;408(1):52–57. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.03.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hanover JA, et al. Mitochondrial and nucleocytoplasmic isoforms of O-linked GlcNAc transferase encoded by a single mammalian gene. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2003;409(2):287–297. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9861(02)00578-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Love DC, et al. Mitochondrial and nucleocytoplasmic targeting of O-linked GlcNAc transferase. J Cell Sci. 2003;116(Pt 4):647–654. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lubas WA, Hanover JA. Functional expression of O-linked GlcNAc transferase. Domain structure and substrate specificity. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(15):10983–10988. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.15.10983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Toleman C, et al. Characterization of the histone acetyltransferase (HAT) domain of a bifunctional protein with activable O-GlcNAcase and HAT activities. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(51):53665–53673. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410406200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.He Y, et al. Three-dimensional structure of a Streptomyces sviceus GNAT acetyltransferase with similarity to the C-terminal domain of the human GH84 O-GlcNAcase. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2014;70(Pt 1):186–195. doi: 10.1107/S1399004713029155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wells L, et al. Dynamic O-glycosylation of nuclear and cytosolic proteins: further characterization of the nucleocytoplasmic beta-N-acetylglucosaminidase, O-GlcNAcase. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(3):1755–1761. doi: 10.1074/jbc.m109656200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Comtesse N, Maldener E, Meese E. Identification of a nuclear variant of MGEA5, a cytoplasmic hyaluronidase and a beta-N-acetylglucosaminidase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;283(3):634–640. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.4815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Keembiyehetty CN, et al. A lipid-droplet-targeted O-GlcNAcase isoform is a key regulator of the proteasome. J Cell Sci. 2011;124(Pt 16):2851–2860. doi: 10.1242/jcs.083287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ambros V. The functions of animal microRNAs. Nature. 2004;431(7006):350–355. doi: 10.1038/nature02871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Muthusamy S, et al. MicroRNA-539 Is Up-regulated in Failing Heart, and Suppresses O-GlcNAcase Expression. J Biol Chem. 2014;289(43):29665–29676. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.578682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Trinidad JC, et al. Global identification and characterization of both O-GlcNAcylation and phosphorylation at the murine synapse. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2012;11(8):215–229. doi: 10.1074/mcp.O112.018366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Skorobogatko YV, et al. Human Alzheimer's disease synaptic O-GlcNAc site mapping and iTRAQ expression proteomics with ion trap mass spectrometry. Amino Acids. 2011;40(3):765–779. doi: 10.1007/s00726-010-0645-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hart GW, et al. Cross talk between O-GlcNAcylation and phosphorylation: roles in signaling, transcription, and chronic disease. Annu Rev Biochem. 2011;80:825–858. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060608-102511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shapira M, et al. Unitary assembly of presynaptic active zones from Piccolo-Bassoon transport vesicles. Neuron. 2003;38(2):237–252. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00207-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Comer FI, et al. Characterization of a mouse monoclonal antibody specific for O-linked Nacetylglucosamine. Anal Biochem. 2001;293(2):169–177. doi: 10.1006/abio.2001.5132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Snow CM, Senior A, Gerace L. Monoclonal antibodies identify a group of nuclear pore complex glycoproteins. J Cell Biol. 1987;104(5):1143–1156. doi: 10.1083/jcb.104.5.1143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wells L, et al. Mapping sites of O-GlcNAc modification using affinity tags for serine and threonine post-translational modifications. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2002;1(10):791–804. doi: 10.1074/mcp.m200048-mcp200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Khidekel N, et al. A chemoenzymatic approach toward the rapid and sensitive detection of O-GlcNAc posttranslational modifications. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125(52):16162–16163. doi: 10.1021/ja038545r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tallent MK, et al. In vivo modulation of O-GlcNAc levels regulates hippocampal synaptic plasticity through interplay with phosphorylation. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(1):174–181. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M807431200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Skorobogatko Y, et al. O-linked beta-N-acetylglucosamine (O-GlcNAc) site thr-87 regulates synapsin I localization to synapses and size of the reserve pool of synaptic vesicles. J Biol Chem. 2014;289(6):3602–3612. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.512814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pekkurnaz G, et al. Glucose regulates mitochondrial motility via Milton modification by OGlcNAc transferase. Cell. 2014;158(1):54–68. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang Z, et al. Enrichment and site mapping of O-linked N-acetylglucosamine by a combination of chemical/enzymatic tagging, photochemical cleavage, and electron transfer dissociation mass spectrometry. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2010;9(1):153–160. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M900268-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sprung R, et al. Tagging-via-substrate strategy for probing O-GlcNAc modified proteins. J Proteome Res. 2005;4(3):950–957. doi: 10.1021/pr050033j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Alzheimer A, et al. An English translation of Alzheimer's 1907 paper, "Uber eine eigenartige Erkankung der Hirnrinde". Clin Anat. 1995;8(6):429–431. doi: 10.1002/ca.980080612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Burns A, Iliffe S. Alzheimer's disease. Bmj. 2009;338:b158. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Drzezga A, et al. Cerebral metabolic changes accompanying conversion of mild cognitive impairment into Alzheimer's disease: a PET follow-up study. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2003;30(8):1104–1113. doi: 10.1007/s00259-003-1194-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sancheti H, et al. Age-dependent modulation of synaptic plasticity and insulin mimetic effect of lipoic acid on a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. PLoS One. 2013;8(7):e69830. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0069830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sancheti H, et al. Reversal of metabolic deficits by lipoic acid in a triple transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer's disease: a 13C NMR study. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2014;34(2):288–296. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2013.196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Peila R, Rodriguez BL, Launer LJ. Type 2 diabetes, APOE gene, and the risk for dementia and related pathologies: The Honolulu-Asia Aging Study. Diabetes. 2002;51(4):1256–1262. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.4.1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Alexander GE, et al. Longitudinal PET Evaluation of Cerebral Metabolic Decline in Dementia: A Potential Outcome Measure in Alzheimer's Disease Treatment Studies. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(5):738–745. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.5.738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gong CX, et al. Impaired brain glucose metabolism leads to Alzheimer neurofibrillary degeneration through a decrease in tau O-GlcNAcylation. J Alzheimers Dis. 2006;9(1):1–12. doi: 10.3233/jad-2006-9101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Liu Y, et al. Brain glucose transporters, O-GlcNAcylation and phosphorylation of tau in diabetes and Alzheimer disease. J Neurochem. 2009;111(1):242–249. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06320.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Deng Y, et al. Dysregulation of insulin signaling, glucose transporters, O-GlcNAcylation, and phosphorylation of tau and neurofilaments in the brain: Implication for Alzheimer's disease. Am J Pathol. 2009;175(5):2089–2098. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.090157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Griffith LS, Mathes M, Schmitz B. Beta-amyloid precursor protein is modified with O-linked N-acetylglucosamine. J Neurosci Res. 1995;41(2):270–278. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490410214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lammich S, et al. Constitutive and regulated alpha-secretase cleavage of Alzheimer's amyloid precursor protein by a disintegrin metalloprotease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96(7):3922–3927. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.7.3922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bennett BD, et al. Expression analysis of BACE2 in brain and peripheral tissues. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(27):20647–20651. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002688200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Evin G, et al. Candidate gamma-secretases in the generation of the carboxyl terminus of the Alzheimer's disease beta A4 amyloid: possible involvement of cathepsin D. Biochemistry. 1995;34(43):14185–14192. doi: 10.1021/bi00043a024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.De Strooper B, et al. Deficiency of presenilin-1 inhibits the normal cleavage of amyloid precursor protein. Nature. 1998;391(6665):387–390. doi: 10.1038/34910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Naslund J, et al. The metabolic pathway generating p3, an A beta-peptide fragment, is probably non-amyloidogenic. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1994;204(2):780–787. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.2527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Estus S, et al. Potentially amyloidogenic, carboxyl-terminal derivatives of the amyloid protein precursor. Science. 1992;255(5045):726–728. doi: 10.1126/science.1738846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yuzwa SA, et al. A potent mechanism-inspired O-GlcNAcase inhibitor that blocks phosphorylation of tau in vivo. Nat Chem Biol. 2008;4(8):483–490. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Borghgraef P, et al. Increasing brain protein O-GlcNAc-ylation mitigates breathing defects and mortality of Tau.P301L mice. PLoS One. 2013;8(12):e84442. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0084442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kim C, et al. O-linked beta-N-acetylglucosaminidase inhibitor attenuates beta-amyloid plaque and rescues memory impairment. Neurobiol Aging. 2013;34(1):275–285. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2012.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Arnold CS, et al. The microtubule-associated protein tau is extensively modified with O-linked N-acetylglucosamine. J Biol Chem. 1996;271(46):28741–28744. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.46.28741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Griffith LS, Schmitz B. O-linked N-acetylglucosamine is upregulated in Alzheimer brains. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1995;213(2):424–431. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.2149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Liu F, et al. O-GlcNAcylation regulates phosphorylation of tau: a mechanism involved in Alzheimer's disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(29):10804–10809. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400348101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ksiezak-Reding H, Liu WK, Yen SH. Phosphate analysis and dephosphorylation of modified tau associated with paired helical filaments. Brain Res. 1992;597(2):209–219. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)91476-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Liu Y, et al. Decreased glucose transporters correlate to abnormal hyperphosphorylation of tau in Alzheimer disease. FEBS Lett. 2008;582(2):359–364. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.12.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Förster S, et al. Increased O-GlcNAc Levels Correlate with Decreased O-GlcNAcase Levels in Alzheimer Disease Brain. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2014;1842(9):1333–1339. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2014.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Liu F, et al. Reduced O-GlcNAcylation links lower brain glucose metabolism and tau pathology in Alzheimer's disease. Brain. 2009;132(Pt 7):1820–1832. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Yuzwa SA, et al. Increasing O-GlcNAc slows neurodegeneration and stabilizes tau against aggregation. Nat Chem Biol. 2012;8(4):393–399. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Schulz JB. Update on the pathogenesis of Parkinson's disease. J Neurol. 2008;255(Suppl 5):3–7. doi: 10.1007/s00415-008-5011-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bendor JT, Logan TP, Edwards RH. The function of alpha-synuclein. Neuron. 2013;79(6):1044–1066. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wang Z, et al. Site-specific GlcNAcylation of human erythrocyte proteins: potential biomarkeRs) for diabetes. Diabetes. 2009;58(2):309–317. doi: 10.2337/db08-0994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Alfaro JF, et al. Tandem mass spectrometry identifies many mouse brain O-GlcNAcylated proteins including EGF domain-specific O-GlcNAc transferase targets. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(19):7280–7285. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1200425109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Marotta NP, et al. O-GlcNAc modification blocks the aggregation and toxicity of the protein alpha-synuclein associated with Parkinson's disease. Nat Chem. 2015;7(11):913–920. doi: 10.1038/nchem.2361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Shi J, et al. O-GlcNAcylation regulates ischemia-induced neuronal apoptosis through AKT signaling. Sci Rep. 2015;5:14500. doi: 10.1038/srep14500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kim SJ, et al. Increased O-GlcNAcylation of NF-kappaB Enhances Retinal Ganglion Cell Death in Streptozotocin-induced Diabetic Retinopathy. Curr Eye Res. 2016;41(2):249–257. doi: 10.3109/02713683.2015.1006372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Wani WY, et al. Regulation of autophagy by protein post-translational modification. Lab Invest. 2015;95(1):14–25. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2014.131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Marsh SA, et al. Cardiac O-GlcNAcylation blunts autophagic signaling in the diabetic heart. Life Sci. 2013;92(11):648–656. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2012.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wang P, Hanover JA. Nutrient-driven O-GlcNAc cycling influences autophagic flux and neurodegenerative proteotoxicity. Autophagy. 2013;9(4):604–606. doi: 10.4161/auto.23459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wang P, et al. O-GlcNAc cycling mutants modulate proteotoxicity in Caenorhabditis elegans models of human neurodegenerative diseases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(43):17669–17674. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1205748109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kumar A, et al. Decreased O-linked GlcNAcylation protects from cytotoxicity mediated by huntingtin exon1 protein fragment. J Biol Chem. 2014;289(19):13543–13553. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.553321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Guo B, et al. O-GlcNAc-modification of SNAP-29 regulates autophagosome maturation. Nat Cell Biol. 2014;16(12):1215–1226. doi: 10.1038/ncb3066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Park S, et al. O-GlcNAc modification is essential for the regulation of autophagy in Drosophila melanogaster. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2015;72(16):3173–3183. doi: 10.1007/s00018-015-1889-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]