Abstract

We observed a previously uncharacterized mutation in the protease substrate cleft, L23I, in 31 of 4,303 persons undergoing human immunodeficiency virus type 1 genotypic resistance testing. In combination with V82I, L23I was associated with a sevenfold reduction in nelfinavir susceptibility and a decrease in replication capacity. In combination with other drug resistance mutations, L23I was associated with multidrug resistance and a compensatory increase in replication capacity.

Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) drug resistance mutations have been identified, for the most part, during the preclinical and early clinical development of a new drug. However, the contribution of some mutations to drug resistance, particularly those that are uncommon or that exert their effect only in combination with other mutations, is often not ascertained until a drug has been used in large numbers of individuals.

In a recent study, we reported that mutations at 45 of the 99 amino acid positions in the protease—including 22 not previously associated with drug resistance—were significantly associated with protease inhibitor treatment (14). One of these mutations, L23I, was observed in 18 of 1,240 individuals receiving one or more protease inhibitors compared with 0 of 1,004 untreated individuals (P < 0.001). This mutation was of particular interest because it is highly conserved in untreated individuals and is in the substrate cleft of the protease enzyme.

In the present study, we describe the protease inhibitor treatments that select for L23I, the protease mutations that are associated with L23I, and the effect of L23I on protease inhibitor susceptibility.

Patients and virus isolates

Between 1 July 1997 and 31 December 2003, the Stanford University Hospital Diagnostic Virology Laboratory sequenced 6,425 HIV-1 isolates from 4,303 persons. Forty-three isolates (0.7%) from 31 persons had the protease mutation L23I. L23I was present in pure mutant form in 28 isolates and as part of an electrophoretic mixture with the wild type in 15 isolates. L23I was present in 21 of 26 independent clones (81%) from six isolates that underwent clonal sequencing.

Antiretroviral treatment histories were available for 28 of the 31 patients (Table 1). L23I developed in three persons receiving nelfinavir and in one person receiving saquinavir as their sole protease inhibitor. In patients who had previously been treated with other protease inhibitors, L23I developed during treatment with nelfinavir in one person, ritonavir-boosted saquinavir in five persons, ritonavir-boosted amprenavir in two persons, and nelfinavir followed by ritonavir-boosted saquinavir in one person.

TABLE 1.

Protease inhibitors and concomitant protease mutations in 28 HIV-1 isolates with the substrate cleft mutation L231

| Identi- fication | Protease inhibitors receiveda | Mutation(s) at drug resistance positions | Other mutations |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1809 | NFV*85 | 82I | 13V, 14R, 15V, 20T, 35G, 41K, 64V, 77I, 93L |

| 9429 | NFV*202 | 46I, 82I, 90M | 60E, 62V, 63N, 64V, 72T, 77I, 93L |

| 9752 | NFV*108 | 82I | 35D, 41K, 58EQ, 63P, 77I, 93L |

| 8022 | SQV*325 | 54V, 88D, 90M | 10I, 13V, 37D, 63P, 71V, 72V, 74S |

| 1277 | IDV*8, NFV*64 | 82I | 37T, 63P, 74S, 77I, 93L |

| 2251 | IDV*56, NFV*208 | 46I | 10I, 13V, 35D, 37D, 61N, 62V, 63P, 64V, 76E, 77I |

| 5774 | IDV*112, NFV*203 | 46I, 90M | 13V, 35D, 37P, 63A, 71V, 77I, 93IM |

| 6496 | NFV*20, SQV*112 | 35D, 37S, 41K, 63T | |

| 1800 | RTV*78, rSQV*38 | 46L, 54V, 82A, 84V, 90M | 10I, 41RK, 57K, 63P, 71V |

| 1263 | IDV*59, rSQV*376 | 53L, 73S, 90M | 10I, 62V, 63P, 69HY, 71T, 77I, 85V |

| 5204 | NFV*49, rSQV*82 | 84V, 88D, 90M | 16A, 20R, 36I, 57K, 61H, 63P, 69Q, 71I, 93M |

| 5750 | IDV*74, rSQV*85 | 46I, 53L, 84V, 90M | 10I, 35D, 37D, 60E, 63P, 64V, 71V, 76V, 93L |

| 6497 | NFV*148, rSQV*156 | 46L, 48V, 53L, 54V, 82A, 84V, 90M | 10IV, 36I, 41K, 62V, 63P, 71V, 74S, 93L |

| 14345 | SQV*12, IDV*220, NFV*82 | 88S | 13V, 33F, 37S, 39S, 60E, 71V, 77I |

| 6348 | SQV*38, NFV*143 | 73S, 82I, 88S, 90M | 13V, 33I, 35D, 36IL, 57K, 58E, 62V, 63P, 69Y, 71V, 72T, 75I, 93L |

| 608 | IDV*97, NFV*24, rSQV*91 | 46L, 84V, 88D, 90M | 10I, 13V, 33M, 63P, 71V, 72M, 89LV |

| 2190 | IDV*43, NFV*8, rSQV*108 | 46I, 53Y, 90M | 10I, 63P, 72V, 77I, 89T, 93L |

| 3910 | SQV*119, NFV*30, rSQV*65 | 46L, 54V, 82A, 84V, 90M | 10I, 39A, 63P, 71V, 77I |

| 4485 | RTV*111, NFV*13, rSQV*89 | 46L, 53L, 54V, 84V, 90M | 10I, 20R, 35D, 36I, 60E, 63P, 71V, 93L |

| 1158 | IDV*40, NFV*36, rSQV*21 | 53L, 54V, 82A, 90M | 10I, 35D, 36V, 57K, 60E, 62V, 63P, 71V, 193L |

| 1435 | IDV*30, NFV*30, rSQV*58 | 32I, 46I, 53L, 82A, 90M | 10V, 12S, 19Q, 36L, 37S, 62V, 63P, 71V |

| 1458 | IDV*62, NFV*68, rSQV*70 | 46L, 48VA, 54V, 82A, 84V, 90M | 10I, 41K, 60E, 62V, 63S, 64V, 69R |

| 5540 | NFV*52, IDV*102, rAPV*176 | 54L, 73C, 90M | 10LI, 33F, 62V, 63P, 64V, 66V, 77I, 193L |

| 17599 | RTV*104, IDV*130, rLPV*38 | 46L, 54V, 82A | 10I, 15V, 162V, 63V, 69R, 71V, 72K, 76V, 89M, 93L |

| 2095 | SQV*73, RTV*48, IDV*31, rSQV*57 | 53L, 54V, 82AT | 10I, 20R, 35D, 36I, 37S, 41K, 60E, 61H, 62IV, 63P, 71V, 87G |

| 8355 | IDV, RTV, rSQV*156, SQV/APV*52 | 32I, 46I, 47V, 53L, 54V, 73C, 90M | 10I, 33I, 35D, 36I, 62V, 63P, 64V, 66L, 71AIT, 72MV, 93L |

| 1498 | SQV*86, IDV*42, NFV*42, SQV*102 | 54L, 73S, 90M | 10I, 13V, 62IV, 63P, 71V, 72L, 77I |

| 628 | SQV*43, IDV*47, rSQV*36, rAPV*24 | 46L, 82A, 84V, 90M | 10I, 58E, 60E, 61EK, 63P, 71T, 72T |

Protease inhibitors shown in bold represent courses of treatment for which a pretherapy isolate was wild type at position 23 and a posttherapy isolate had the protease mutation L23I. The numbers following the asterisks indicate the number of weeks that the protease inhibitor was administered. APV, amprenavir; IDV, indinavir; rLPV, lopinavir; NFV, nelfinavir; RTV, ritonavir; SQV, saquinavir; rSQV, low-dose ritonavir in combination with saquinavir; rAPV, low-dose ritonavir in combination with amprenavir.

Concomitant protease mutations

Isolates from five patients—including three who had received nelfinavir as their sole protease inhibitor, one who received nelfinavir following an 8-week course of indinavir, and one who had received nelfinavir following a 38-week course of saquinavir—had the protease mutation V82I. V82I, a polymorphism that occurs in about 1 to 2% of untreated and treated persons with subtype B viruses and that confers minimal if any resistance to the available protease inhibitors (1, 7), was present in sequences from 83 of 4,303 (1.9%) persons in this data set. L23I was significantly more common in persons with V82I than without V82I (5 of 83 [6.0%] versus 23 of 4,220 [0.5%]; P < 0.001). Phylogenetic analysis of the sequences of these five isolates demonstrated a mean 6.8% divergence (range, 4.3 to 8.1%) and confirmed that this pattern developed independently in these persons rather than resulting from epidemiologic spread or laboratory cross-contamination.

Besides V82I, L23I was accompanied by a wide variety of other protease inhibitor-resistance mutations, including L90M in 20 persons, M46I/L in 14 persons, I54V/L in 12 persons, V82A in 9 persons, F53L/Y in 9 persons, and I84V in 8 persons (Table 1). Among the six persons with viruses containing L23I alone (isolate 6496), L23I plus V82I (isolates 1809, 9752, and 1277), or L23I plus a single known drug resistance mutation (isolates 2251 and 14345), the development of L23I was associated with rebounding plasma HIV-1 RNA levels and subsequent virologic suppression with a new regimen containing either a nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor or a boosted protease inhibitor. Among the 22 persons with two or more known drug resistance mutations in addition to L23I, there was no single virologic response pattern.

In vitro drug susceptibility

To study the phenotypic effects of molecular infectious clones with L23I, four pairs of isogenic viruses were created containing either a wild-type or mutant residue at position 23 (Table 2). Two pairs of recombinant molecular infectious clones were created from plasma samples that, by direct PCR sequencing, had an electrophoretic mixture at position 23 indicating the presence of a quasispecies containing a mixture of wild-type and mutant viruses. The third pair of isogenic viruses consisted of the common laboratory strain NL43 and a site-directed mutant, NL43+L23I. The fourth pair of isogenic viruses consisted of a recombinant molecular infectious clone (isolate 1277) and a modified version of that clone in which L23I was removed by site-directed mutagenesis, restoring the wild-type residue at this position (1277_23wt).

TABLE 2.

Drug susceptibility of HIV-1 isolates containing the substrate cleft mutation L23I

| Identifi- cation no. | Descrip- tiona | Coden 23b | Mutation(s) at drug resistance positions | Other protease mutation(s) | Reduction in drug susceptibility (fold)c

|

Replication capicityd (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| APV | IDV | LPV | NFV | RTV | SQV | ||||||

| NL43 | NL43 | WT | None | 37S | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 100 |

| NL43+L23I | NL43+L23I | I | None | 37S | 1.0 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 1.3 | 0.8 | 0.6 | 36 |

| 1277 | 1277_23wt | WT | 82I | 20R, 37T, 63P, 74S, 77I, 93L | 1.0 | 0.8 | 0.6 | 3.2 | 1.2 | 0.8 | 62 |

| 1277 | 1277 | I | 82I | 20R, 37T, 63P, 74S, 77I, 93L | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 6.7 | 1.7 | 1.3 | 10 |

| 4485 | 4485 clone 3 | WT | 46I, 53L, 54V, 84V, 90M | 10I, 20R, 35D, 36I, 60E, 63P, 71V, 93L | 6 | 12 | 24 | 37 | 139 | 132 | 35 |

| 4485 | 4485 clone 6 | I | 46I, 53L, 54V, 84V, 90M | 10I, 20R, 35D, 36I, 60E, 63P, 71V, 93L | 9 | 9 | 28 | 56 | 187 | 306 | 59 |

| 4733 | 4733 clone 3 | WT | 46L, 54V, 82A, 84V, 90M | 10V, 15V, 36I, 62V, 63P, 71V, 93L | 7 | 11 | 35 | 20 | 63 | 25 | 6 |

| 4733 | 4733 clone 1 | I | 46L, 54V, 82A, 84V, 90M | 10V, 36I, 62V, 63P, 71V, 93L | 6 | 6 | 26 | 18 | 63 | 41 | 39 |

| 9752 | SUH Labe | I | 82I | 35D, 41K, 58QE, 63P, 77I, 93L | 1.8 | 0.9 | 1.0 | 7.0 | 2.9 | 1.4 | NA |

| 8622 | SUH Lab | I | 54V, 88D, 90M | 10I, 13V, 36IM, 37DN, 63P, 71V, 72, 74S | 1.3 | 5.0 | NAg | 34 | 22 | 60 | NA |

| 1800 | SUH Lab | I | 53L, 54V, 82A, 90M | 10V, 57K, 63P, 71V | 2.3 | 6.3 | 26 | 15 | 65 | 20 | NA |

| 11637 | Colonnof | I | 46I, 84V, 88S | 10I, 13V, 35D, 37Y, 41K, 71T, 77I, 89M | 0.3 | 12 | NA | 66 | 3.6 | 12 | NA |

| 11644 | Colonno | I | 24F, 46I, 53L, 73T, 84V, 90M | 10I, 13V, 15V, 16A, 35D, 62V, 64V, 77I, 93L | 4.3 | 24 | NA | 56 | 19 | 24 | NA |

| 11643 | Colonno | I | 30N, 88D | 10F, 13V, 37S, 41K, 62V, 63P, 70R, 71T, 93L | 1.4 | 2.3 | NA | 142 | 0.3 | NA | NA |

NL43 is the control used in the PhenoSense assay, and the fold resistance to this isolate for each drug is 1.0.

WT, wild type.

APV, amprenavir; IDV, indinavir; LPV, lopinavir; NFV, nelfinavir; RTV, ritonavir; SQV, saquinavir. Boldface indicates values that represent decreased drug susceptibility.

Because NL43 is the control, the percent replication capacity for this isolate is 100%.

SUH, Stanford University Hospital.

R. J. Colonno, K. Hertogs, B. Larder, K. Limoli, G. Heilik-Snyder, and N. Parkin, 4th Int. Workshop HIV Drug Resist. Treatment Strategies, abstr. 8.

NA, not applicable.

To create recombinant molecular infectious clones, the 3′ part of gag and the complete protease gene amplified from samples were ligated into deleted pNL43 vector with 3′-gag/protease deleted (pNLPFB digested with ApaI and MscI) (5). Competent Escherichia coli cells were transformed with vectors containing infectious HIV-1 recombinants, and colonies were selected for confirmatory sequencing and transfection into CEM cells to create infectious virus stock. Recombinant isolates were tested with the PhenoSense assay (ViroLogic, South San Francisco, Calif.), an assay that has a coefficient of variation for protease inhibitors between 14 and 17% for both wild-type and mutant HIV-1 isolates (9).

Table 2 shows the drug susceptibility results (PhenoSense, ViroLogic) of the four pairs of isolates described above and of one uncloned clinical isolate. By itself, L23I had no effect on drug susceptibility when placed in the wild-type NL43 vector. However, in clone 1277, which also contained V82I, L23I contributed to nelfinavir resistance, raising the level of resistance with V82I alone from 3.2-fold to 6.7-fold—a level similar to that observed in the uncloned clinical isolate that also had L23I and V82I (isolate 9752). In both of these comparisons, L23I was associated with decreased replication capacity (from 100% to 36% in the NL43 backbone and from 62% to 10% in clone 1277).

In combination with other major protease inhibitor resistance mutations, L23I did not have a consistent effect on drug susceptibility. For isolate 4485, L23I was associated with increased levels of resistance to amprenavir, nelfinavir, ritonavir, and saquinavir of about 50 to 100%. For isolate 4733, L23I was associated with decreased resistance to indinavir and lopinavir but increased resistance to saquinavir. In both pairs, L23I was associated with an increase in replication capacity.

NC/p1 and p1/p6 cleavage sites

The NC/p1 and p1/p6 cleavage sites in HIV-1 Gag are preferential sites of mutation in response to the reduction of viral fitness associated with drug resistance mutations in the protease substrate cleft (12). Clones from isolates 4485 and 4733, both of which contained L23I plus multiple drug resistance mutations, had previously described mutations at the NC/p1 or p1/p6 cleavage sites (Table 3). The A-V change at the P2 position of the NC/p1 site, which was observed in the isolate 4733 clones, is one of the most common reported cleavage site mutations (3). The K-R change at the P4′ position of the NC/p1 site is a rare change that is not associated with drug therapy (8, 15). The L-V and S-N changes at the P1′ and P3′ positions of the p1/p6 sites have also been commonly reported (3).

TABLE 3.

Sequences of NC/P1 and P1/P6 protease cleavage sites in clones with and without L23I

| Identification | Description | Position 23a | Drug resistance mutation(s) | Sequence change(s)b

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NC/pl (RQANFLGK) | pl/p6 (PGNFLQSR) | ||||

| 1277 | Clone with L23I | I | 82I | RQANFLGK | PGNFLQSR |

| 4485 | Clone 3 | WT | 46I, 53L, 54V, 84V, 90M | RQANFLGR | PGNFVQNR |

| 4485 | Clone 6 | I | 46I, 53L, 54V, 84V, 90M | RQANFLGR | PGNFVQNR |

| 4733 | Clone 3 | WT | 46L, 54V, 82A, 84V, 90M | RQVNFLGK | PGNFLQNR |

| 4733 | Clone 1 | I | 46L, 54V, 82A, 84V, 90M | RQVNFLGK | PGNFLQNR |

WT, wild type.

Boldface indicates differences from the consensus subtype B sequence.

In the two isolates with multiple drug resistance mutations (4485 and 4733), cleavage site mutations were present in the clones with and without L23I and therefore were most likely related to the presence of the mutations other than L23I. The clone from isolate 1277, which did not have drug resistance mutations other than L23I, did not have mutations at either of these cleavage sites.

Structural modeling

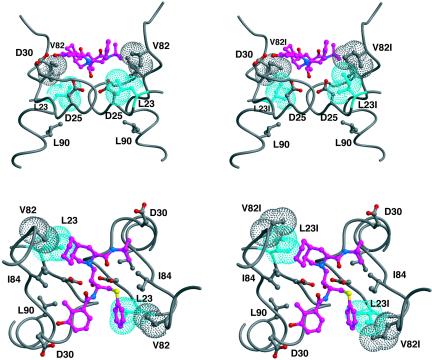

Position 23 is located at the base of the active site at the dimerization interface. In crystal structures with substrates and inhibitors, L23 makes direct van der Waals contacts with the P1/P1′ sites of the ligand (Fig. 1) (6, 10). Within the HIV-1 protease dimer, the side chain of L23 is tightly packed, making van der Waals contacts with the side chains of R8, P9, I10, V82, and V84 and, across the dimer interface, with G27. Although not quite making direct contact with the catalytic D25, the side chain L23 is a closest neighbor. With such a critical position, it is not surprising that L23 rarely is seen to mutate, as most changes at this site could dramatically impact substrate recognition and protease activity.

FIG. 1.

Packing of residue 23 within the crystal structure of HIV-1 protease bound to nelfinavir (1OHR) (6). Shown are two views of the active site separated by 90°. The images on the left are the crystal structure, and those on the right are with side chains of L23 and V82, each replaced with isoleucine within the graphics program MIDAS (4). Residue 23 is colored cyan; the other atoms are colored by atom type, with the carbons in nelfinavir colored magenta. van der Waals surfaces are shown for the side chains of residues 23 and 82.

The association of L23I with V82I is probably due to the closeness of these two residues within the protease three-dimensional structure. When both side chains mutate to isoleucine, they have more freedom to repack the edge of the P1/P1′ pocket. This repacking could easily confer resistance to nelfinavir, which packs against both of these residues, as seen in Fig. 1 (6).

Conclusions

Position 23 is highly conserved in HIV-1 and other primate lentiviruses and has been considered an important residue in the enzyme for drug targeting (13). Mutations at this position are uncommon, occurring in 0.7% of patients in this series, 0.2% of 40,000 isolates in a U.S. reference laboratory (2), 0.2% of 25,000 isolates in a Canadian reference laboratory (P. K. Cheung, B. Wynhoven, and P. R. Harrigan, personal communication), and 0.3% of nearly 3,000 patients in a European clinic database (16). Our results show that in combination with V82I, L23I was associated with a six- to sevenfold reduction in nelfinavir susceptibility and a decrease in replication capacity. In combination with other drug resistance mutations, L23I is associated with multidrug resistance and an increase in replication capacity.

Unlike other mutations at position 82 (such as V82A, V82T, V82F, and V82S), the conservative substitution V82I confers minimal or no resistance to currently available protease inhibitors and is selected rarely during protease inhibitor treatment (11). Indeed, it occurs in about 1 to 2% of treated and untreated subtype B isolates, 3% of untreated subtype C isolates, and 75% of untreated subtype G isolates (11).

In conclusion, L23I is a treatment-selected mutation at a highly conserved residue that often occurs with V82I alone and, in this setting, is associated with nelfinavir resistance. It also occurs in combination with other drug resistance mutations, and in this setting, it is associated with multidrug resistance and a compensatory increase in HIV-1 replication capacity.

Acknowledgments

E.J., M.A.W., and R.W.S. were supported in part by a grant from the National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, AI46148-01. S.R., C.S., and R.W.S. were supported in part by a grant from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, 5P01GM066524-02.

REFERENCES

- 1.Brown, A. J., H. M. Precious, J. Whitcomb, V. Simon, E. S. Daar, R. D'Aquila, P. Keiser, E. Connick, N. Hellmann, C. Petropoulos, M. Markowitz, D. Richman, and S. J. Little. 2001. Reduced susceptibility of HIV-1 to protease inhibitors from patients with primary HIV infection by three distinct routes, abstr. 424. 8th Conf. Retrovir. Opportunistic Infect., Chicago, Ill.

- 2.Chen, L., A. Perlina, and C. J. Lee. 2004. Positive selection detection in 40,000 human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) type 1 sequences automatically identifies drug resistance and positive fitness mutations in HIV protease and reverse transcriptase. J. Virol. 78:3722-3732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Côté, H. C., Z. L. Brumme, and P. R. Harrigan. 2001. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 protease cleavage site mutations associated with protease inhibitor cross-resistance selected by indinavir, ritonavir, and/or saquinavir. J. Virol. 75:589-594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ferrin, T. E., C. C. Huang, L. D. Jarvis, and R. Langridge. 1988. The MIDAS display system. J. Mol. Graphics 6:13-27. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Imamichi, T., S. C. Berg, H. Imamichi, J. C. Lopez, J. A. Metcalf, J. Falloon, and H. C. Lane. 2000. Relative replication fitness of a high-level 3′-azido-3′-deoxythymidine-resistant variant of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 possessing an amino acid deletion at codon 67 and a novel substitution (Thr→Gly) at codon 69. J. Virol. 74:10958-10964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaldor, S. W., V. J. Kalish, J. F. Davies, B. V. Shetty, J. E. Fritz, K. Appelt, J. A. Burgess, K. M. Campanale, N. Y. Chirgadze, D. K. Clawson, B. A. Dressman, S. D. Hatch, D. A. Khalil, M. B. Kosa, P. P. Lubbehusen, M. A. Muesing, A. K. Patick, S. H. Reich, K. S. Su, and J. H. Tatlock. 1997. Viracept (nelfinavir mesylate, AG1343): a potent, orally bioavailable inhibitor of HIV-1 protease. J. Med. Chem. 40:3979-3985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.King, R. W., D. L. Winslow, S. Garber, H. T. Scarnati, L. Bachelor, S. Stack, and M. J. Otto. 1995. Identification of a clinical isolate of HIV-1 with an isoleucine at position 82 of the protease which retains susceptibility to protease inhibitors. Antivir. Res. 28:13-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Op de Coul, E., A. van der Schoot, J. Goudsmit, R. van den Burg, W. Janssens, L. Heyndrickx, G. van der Groen, and M. Cornelissen. 2000. Independent introduction of transmissible F/D recombinant HIV-1 from Africa into Belgium and The Netherlands. Virology 270:267-277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parkin, N. T., N. S. Hellmann, J. M. Whitcomb, L. Kiss, C. Chappey, and C. J. Petropoulos. 2004. Natural variation of drug susceptibility in wild-type human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:437-443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prabu-Jeyabalan, M., E. Nalivaika, and C. A. Schiffer. 2002. Substrate shape determines specificity of recognition for HIV-1 protease: analysis of crystal structures of six substrate complexes. Structure 10:369-381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rhee, S. Y., M. J. Gonzales, R. Kantor, B. J. Betts, J. Ravela, and R. W. Shafer. 2003. Human immunodeficiency virus reverse transcriptase and protease sequence database. Nucleic Acids Res. 31:298-303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Robinson, L. H., R. E. Myers, B. W. Snowden, M. Tisdale, and E. D. Blair. 2000. HIV type 1 protease cleavage site mutations and viral fitness: implications for drug susceptibility phenotyping assays. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 16:1149-1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang, W., and P. A. Kollman. 2001. Computational study of protein specificity: the molecular basis of HIV-1 protease drug resistance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:14937-14942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu, T. D., C. A. Schiffer, M. J. Gonzales, J. Taylor, R. Kantor, S. Chou, D. Israelski, A. R. Zolopa, W. J. Fessel, and R. W. Shafer. 2003. Mutation patterns and structural correlates in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 protease following different protease inhibitor treatments. J. Virol. 77:4836-4847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang, R., X. Xia, S. Kusagawa, C. Zhang, K. Ben, and Y. Takebe. 2002. On-going generation of multiple forms of HIV-1 intersubtype recombinants in the Yunnan Province of China. AIDS 16:1401-1407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zazzi, M., L. Romano, F. Razzolino, I. Vicenti, C. Macchiesi, S. Machetti, A. Marconi, and P. E. Valensin. 2004. Prevalence and time trends of primary and secondary antiretroviral drug resistance in a large sequence database maintained at the University of Siena, Italy, abstr. 4.23. 2nd Eur. HIV Drug Resist. Workshop, Rome, Italy.