Abstract

OBJECTIVE

The objective of this analysis was to estimate the 3-year continuation rates of long-acting reversible contraceptive (LARC) methods, and compare these rates to non-LARC methods.

STUDY DESIGN

The Contraceptive CHOICE Project (CHOICE) was a prospective cohort study that followed 9,256 participants with telephone surveys at 3 and 6 months, then every 6 months for 2–3 years. We estimated 3-year continuation rates of baseline methods chosen for CHOICE including three LARC methods (52mg levonorgestrel intrauterine device, LNG-IUD; the copper intrauterine device, Cu-IUD; and the subdermal implant) and compared these rates to non-LARC hormonal methods (depot medroxyprogesterone acetate, oral contraceptive pills, contraceptive patch, or vaginal ring). Eligibility criteria for this analysis included participants who started their baseline chosen method by the 3-month survey. Participants who discontinued their method to attempt conception were censored. We used a Cox proportional hazard model to adjust for confounding and to estimate the hazard ratio (HR) for risk of discontinuation.

RESULTS

Our analytic sample consisted of 4,708 CHOICE participants who met inclusion criteria. Three-year continuation rates were 69.8% for users of the LNG-IUD, 69.7% for Cu-IUD users, and 56.2% for implant users. At 3 years, continuation was 67.2% among LARC users and 31.0% among non-LARC users (p <0.001). After adjustment for age, race, education, socioeconomic status, parity, and history of sexually transmitted infection, the hazard ratio for risk of discontinuation was three-fold higher among non-LARC method users than LARC users (HRadj = 3.08, 95% CI 2.80 – 3.39).

CONCLUSION

Three-year continuation of the two IUDs approached 70%. Continuation of LARC methods was significantly higher than non-LARC methods.

Keywords: contraception, continuation, intrauterine device, subdermal implant, long-acting reversible contraception

INTRODUCTION

Long-acting reversible contraceptive (LARC) methods are highly effective and have high user satisfaction [1]. Their use has increased in the United States over the past two decades with approximately 8.5% of contracepting women reporting current use of a LARC method [2]. In fact, a recent report demonstrated a nearly 5-fold increase in LARC methods over the last decade [3]. LARC users are likely to be highly satisfied with their method at 12 and 24 months [4,5]. However, data are lacking regarding continuation of LARC methods at three years in the United States. Some of the prior studies that assessed longer-term continuation randomized women to their contraceptive method and included women from many different countries [6,7]. The largest study was performed by Sivin and colleagues. This multinational study randomized women to the LNG-20 (the predecessor to the current levonorgestrel-containing intrauterine device (LNG-IUD) and the TCu380Ag (the predecessor to the current copper-IUD, Cu-IUD). Cumulative continuation at 3 years was 49% among LNG-20 users and 59% among TCu380Ag users [8]. Other prospective studies found 3-year continuation rates of 67–78% among users of copper IUDs [9,10]. Continuation of LNG-IUD has been reported at 73–80% at 3 years [11,12]. Subdermal implants have international continuation rates of 30–53% [12–15].

This analysis was performed to estimate rates of 36-month continuation of the baseline contraceptive method chosen and compare continuation rates of LARC and non-LARC methods. In addition, we explored baseline characteristics associated with discontinuation of contraceptive methods. We hypothesized that 36-month continuation rates for the LARC methods would exceed 60% and that continuation would be significantly higher for LARC methods than non-LARC methods.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

In 2007, the Contraceptive CHOICE Project (CHOICE) began recruiting women for a prospective observational cohort study. The goal of the study was to reduce the unintended pregnancy rate in the St. Louis area by promoting the most effective methods of contraception and eliminating the cost barrier to all forms of contraception. The methods have been reported in detail [16], but are described briefly below. The Human Research Protection Office at Washington University in St. Louis approved the study protocol prior to study recruitment.

Participants were referred to CHOICE through their health care providers, posted flyers, and by word of mouth. Recruitment sites included local health care centers, two abortion care providers, and a university-associated clinical research center. Inclusion criteria included women : 1) 14–45 years of age; 2) desiring reversible contraception and willing to start a new method; 3) sexually active with a male partner or intending to be within 6 months; 4) living or receiving reproductive care in the St. Louis area; and 5) able to consent in English or Spanish. Women were excluded if they desired pregnancy in the next 12 months or were status-post hysterectomy or permanent sterilization. Recruitment of the 9,256 participants began in 2007 and was completed in 2011. All participants provided written informed consent prior to study enrollment.

All potential participants heard a standardized introduction to LARC methods, and upon enrollment they received additional contraceptive counseling [17]. LARC methods included the LNG-IUD, the Cu-IUD, and the 3-year subdermal implant. The contraceptive counseling reviewed all reversible methods in order of effectiveness from most to least effective. After a baseline interview, participants completed screening for sexually transmitted infections (STIs), received their contraceptive of choice at no cost and were followed for 2 or 3 years, depending on the timing of enrollment. Follow-up telephone interviews were performed at 3 and 6 months, then every 6 months thereafter for the duration of study participation. At the enrollment visit each participant chose her baseline method. When possible, they would start that method immediately. In certain cases (such as when pregnancy could not be reasonably ruled out), the patient received a bridge method until they returned for initiation of their chosen method. Bridge methods included depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA), oral contraceptive pills (OCPs), combined contraceptive patch, vaginal ring, or condoms. Participants were able to switch methods at any time during their follow-up. For the purposes of this analysis, if a participant switched her method, we considered this a discontinuation of the baseline method. Women who received the implant were told it was approved for up to 3 years of use. If a participant had the device removed and reinserted within the same month it was not considered a discontinuation. Follow-up interviews focused on method use, complaints, complications, side effects, method troubleshooting, reasons for method discontinuation and pregnancies. CHOICE Project participants have unrestricted access to device removal even after CHOICE ended.

This analysis included women who chose a LARC or a non-LARC method (DMPA, OCPs, contraceptive patch, or vaginal ring), started using their method by their 3-month survey, and completed their 36-month follow-up survey or had another data source which verified continuation or discontinuation at 3 years. Continuation rates at 3 years were estimated for each method. LARC methods were compared to non-LARC methods, and were stratified by age (14–19 and 20–45 years of age). Descriptive analyses were performed to describe demographic characteristics of participants using chi-square test or t-test, where appropriate. Normality was assessed for continuous variables. The time to event for this survival analysis was calculated from method initiation to the time point when the participant discontinued her contraceptive method. If she was lost to follow-up, she was censored at her last time of contact with CHOICE. Participants were censored if they discontinued a contraceptive method to attempt pregnancy. Kaplan-Meier survival functions were used to estimate continuation rates among different methods. We used Cox proportional hazard models to estimate hazard ratios (HR) for risk of contraceptive method discontinuation for characteristics associated with discontinuation. We defined confounders as variables that changed the estimate of hazard ratio for a contraceptive method by 10% or more when they were included in the model. Confounding variables and significant factors from univariable analysis or variables set a priori were included in the final multivariable model to evaluate their effect size. The alpha level was set at 0.05. Stata software (version 11, StataCorp, College station, Texas) was used for all analyses.

RESULTS

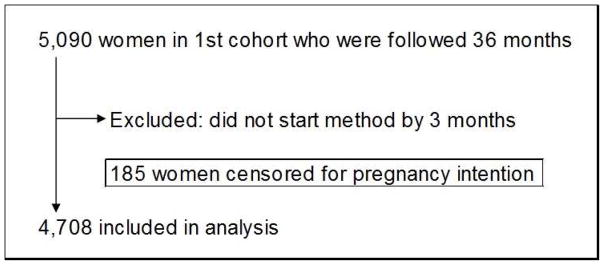

Of 9,256 CHOICE participants, the first 5,090 were followed for 3 years. In this cohort, 382 were excluded because they did not start their chosen baseline method by the 3–month survey. There were a total of 4,708 participants (92%) who were followed for 3 years and included in this analysis. A flow diagram of included participants is shown in Figure 1. There were 185 women (4%) who were censored due to discontinuation for desire to conceive or pregnancy.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of women included in the analysis

Demographic and reproductive characteristics are shown in Table 1. Mean age of participants in this analysis was 25 years; 48% were black; 35% had a high school education or less; 34% received public assistance; 44% had no health insurance; and 12% reported public insurance. Overall, 47% were nulliparous and 66% reported at least 1 unintended pregnancy at baseline. There were 644 adolescents in our cohort, 405 using LARC methods and 239 using non-LARC methods. In our stratified analysis by LARC versus non-LARC methods, we noted that LARC users were older, had higher parity, were more likely to have public insurance, and more likely to have a history of an unintended pregnancy.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of analytic sample stratified by contraceptive method and age

| Overall (n=4708) | non-LARC (n=1505) | LARC (n=3203) | p-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | <0.001 |

| 25.2 | 5.7 | 24.0 | 5.0 | 25.7 | 5.9 | ||

|

| |||||||

| Race | N | % | N | % | N | % | 0.6 68 |

| Black | 2243 | 47.7 | 723 | 48.1 | 1520 | 47.5 | |

| White | 2100 | 44.6 | 659 | 43.8 | 1441 | 45.0 | |

| Others | 364 | 7.7 | 122 | 8.1 | 242 | 7.6 | |

|

| |||||||

| Education | <0.001 | ||||||

| ≤High School | 1661 | 35.3 | 472 | 31.4 | 1189 | 37.1 | |

| Some College | 1987 | 42.2 | 666 | 44.3 | 1321 | 41.3 | |

| College graduate | 1058 | 22.5 | 366 | 24.3 | 692 | 21.6 | |

|

| |||||||

| BMI | <0.001 | ||||||

| Underweight | 144 | 3.1 | 72 | 4.9 | 72 | 2.3 | |

| Normal | 1895 | 41.2 | 718 | 49.2 | 1177 | 37.4 | |

| Overweight | 1206 | 26.2 | 333 | 22.8 | 873 | 27.8 | |

| Obese | 1357 | 29.5 | 336 | 23.0 | 1021 | 32.5 | |

|

| |||||||

| Low socioeconomic status | <0.001 | ||||||

| No | 2088 | 44.4 | 776 | 51.6 | 1312 | 41.0 | |

| Yes | 2618 | 55.6 | 728 | 48.4 | 1890 | 59.0 | |

|

| |||||||

| Insurance | <0.001 | ||||||

| None | 2031 | 43.5 | 683 | 46.0 | 1348 | 42.4 | |

| Private | 2081 | 44.6 | 711 | 47.9 | 1370 | 43.0 | |

| Public | 556 | 11.9 | 91 | 6.1 | 465 | 14.6 | |

|

| |||||||

| Parity | <0.001 | ||||||

| 0 | 2225 | 47.3 | 988 | 65.6 | 1237 | 38.7 | |

| 1 | 1150 | 24.4 | 290 | 19.3 | 860 | 26.8 | |

| 2 | 819 | 17.4 | 149 | 9.9 | 670 | 20.9 | |

| 3+ | 514 | 10.9 | 78 | 5.2 | 436 | 13.6 | |

|

| |||||||

| Unintended Pregnancies | <0.001 | ||||||

| 0 | 1599 | 34.0 | 704 | 46.9 | 895 | 28.0 | |

| 1 | 1292 | 27.5 | 423 | 28.2 | 869 | 27.2 | |

| 2 | 780 | 16.6 | 188 | 12.5 | 592 | 18.5 | |

| 3+ | 1027 | 21.9 | 187 | 12.5 | 840 | 26.3 | |

|

| |||||||

| History of Abortion at Baseline? | <0.001 | ||||||

| No | 2870 | 61.0 | 969 | 64.4 | 1901 | 59.4 | |

| Yes | 1838 | 39.0 | 536 | 35.6 | 1302 | 40.6 | |

|

| |||||||

| History of STI at Baseline | 0.011 | ||||||

| No | 2869 | 61.0 | 957 | 63.6 | 1912 | 59.7 | |

| Yes | 1836 | 39.0 | 547 | 36.4 | 1289 | 40.3 | |

LARC: long acting reversible contraceptive

Standard deviation

Low socioeconomic status includes trouble paying for basic necessities or receiving government subsidies in the form of food stamps or welfare

STI: sexually transmitted infection

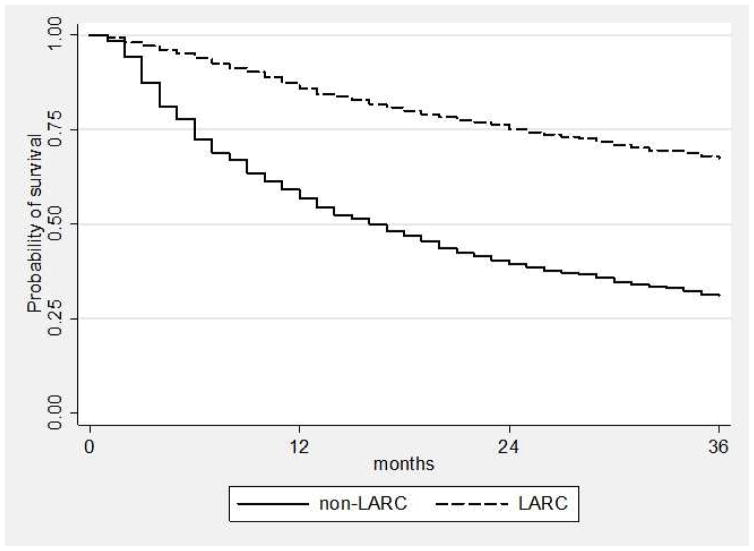

Continuation at 1, 2, and 3 years for each contraceptive method is listed in Table 2. We stratified continuation by LARC and non-LARC methods. At 3 years, continuation was 67.2% among LARC users and 31.0% among non-LARC users (p <0.001). The highest continuation was among IUD users with 69.8% continuation among LNG-IUD users and 69.7% among Cu-IUD users. Non-LARC methods had lower rates of continuation, ranging between 28% – 32% at 3 years. Among adolescents 14–19 years, 3-year continuation was lower for all methods compared to women 20–45 years, and lowest among non-LARC methods (52.6% for adolescents using LARC and 23.1% for non-LARC methods). By 3 years, 54.6% of adolescents continued the LNG-IUD, 49.5% continued the Cu-IUD, and 50.8% continued the subdermal implant.

Table 2.

Kaplan-Meier estimates of 1-, 2-, and 3-year continuation of baseline method chosen

| 1 Year | 2 Year | 3 Year | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | |

| Overall | 76.7 | 75.4 – 77.9 | 64.2 | 62.6 – 65.5 | 56.2 | 54.5 – 57.5 |

| LNG-IUD | 87.3 | 85.8 – 88.6 | 76.7 | 74.8 – 78.5 | 69.8 | 67.6 – 71.7 |

| Cu-IUD | 84.5 | 80.7 – 87.3 | 76.3 | 72.1 – 79.8 | 69.7 | 65.1 – 73.7 |

| Implant | 81.9 | 78.3 – 84.7 | 68.7 | 64.7 – 72.3 | 56.4 | 51.8 – 60.3 |

| DMPA | 57.4 | 51.5 – 62.2 | 40.5 | 33.8 – 44.7 | 33.2 | 26.9 – 37.7 |

| OCP | 58.1 | 56.3 – 64.6 | 40.1 | 37.9 – 46.5 | 29.5 | 27.3 – 35.8 |

| Ring | 53.6 | 49.7 – 58.6 | 36.7 | 33.1 – 41.9 | 29.1 | 25.8 – 34.4 |

| Patch | 46.1 | 38.3 – 57.4 | 35.0 | 25.7 – 44.5 | 28.1 | 19.5 – 37.9 |

| LARC | 85.9 | 84.5 – 87.0 | 75.2 | 73.6 – 76.7 | 67.3 | 65.4 – 68.9 |

| Non-LARC | 55.6 | 54.2 – 59.4 | 38.7 | 36.9 – 42.1 | 30.2 | 28.5 – 33.5 |

| Adolescents 14–19 years | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| LARC | 82.1 | 77.9 – 85.6 | 68 | 63.0 – 72.5 | 52.6 | 47.2 – 57.7 |

| Non-LARC | 46.9 | 42.1 – 54.6 | 32.9 | 28.4 – 40.6 | 21.2 | 17.6 – 29.0 |

| Adults 20–45 years | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| LARC | 86.4 | 85.0 – 87.6 | 76.2 | 74.5 – 77.7 | 69.3 | 67.4 – 71.0 |

| Non-LARC | 57.4 | 55.7 – 61.3 | 39.9 | 37.6 – 43.4 | 31.9 | 29.8 – 35.4 |

LNG, levonorgestrel

IUD, intrauterine device

Cu, copper

DMPA, depomedroxyprogesterone acetate

Oral contraceptive pill

LARC, long-acting reversible contraceptive

CI, confidence Interval

Univariable analysis of risk factors for discontinuation is shown in Table 3. The multivariable model is shown in Table 4. After adjustment for age, race, education, low socioeconomic status (SES), parity, and history of STI, the hazard ratio for discontinuation was more than 3-times higher among non-LARC method users (HRadj = 3.08, 95% CI 2.80 – 3.39) than LARC users. Participants 14–19 years of age at baseline were more likely to discontinue at 3 years compared to women 20 years and older (HRadj = 1.37, 95% CI 1.19 – 1.56). Compared to those with a high school education or less, college graduates reported a lower risk of discontinuation (HRadj = 0.85, 95% CI 0.74 – 0.98).

Table 3.

Univariable analysis of risk factors for discontinuation of baseline contraceptive method at 3 years

| Univariable model | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| HR | 95% CI | ||

| Contraceptive method | |||

| OCP | Reference | ||

| LNG-IUD | 0.30 | 0.27 | 0.35 |

| Cu-IUD | 0.31 | 0.26 | 0.38 |

| Implant | 0.48 | 0.40 | 0.56 |

| DMPA | 1.01 | 0.85 | 1.20 |

| Patch | 1.21 | 0.94 | 1.56 |

| Ring | 1.12 | 0.96 | 1.30 |

|

| |||

| Age | |||

| 14–19 | 1.55 | 1.38 | 1.74 |

| 20+ | Reference | ||

|

| |||

| Race | |||

| Black | 1.20 | 1.09 | 1.32 |

| White | Reference | ||

| Others | 1.30 | 1.10 | 1.54 |

|

| |||

| Education | |||

| ≤High School | Reference | ||

| Some college | 0.93 | 0.84 | 1.03 |

| College grad | 0.82 | 0.73 | 0.93 |

|

| |||

| Body Mass Index | |||

| Underweight | 1.18 | 0.92 | 1.51 |

| Normal | Reference | ||

| Overweight | 0.91 | 0.82 | 1.02 |

| Obese | 0.78 | 0.70 | 0.87 |

|

| |||

| Low Socioeconomic Status | |||

| No | Reference | ||

| Yes | 0.95 | 0.87 | 1.04 |

|

| |||

| Insurance | |||

| None | 1.07 | 0.97 | 1.18 |

| Commercial | Ref | ||

| Public | 1.04 | 0.90 | 1.20 |

|

| |||

| Parity | |||

| 0 | 1.38 | 1.27 | 1.51 |

| 1+ | Reference | ||

|

| |||

| Prior Unintended Pregnancies | |||

| 0 | Reference | ||

| 1+ | 0.79 | 0.72 | 0.87 |

|

| |||

| History of STI | |||

| No | Reference | ||

| Yes | 1.13 | 1.03 | 1.24 |

HR, hazard ratio

CI, confidence interval

OCP, oral contraceptive pill

LNG, levonorgestrel

IUD, intrauterine device

Cu, copper

DMPA, depot medroxyprogesterone acetate

Low socioeconomic status is defined as trouble paying for basic needs (food, housing, medical care, transportation) or receiving government aid (food stamps, welfare)

STI, sexually transmitted infection

Table 4.

Multivariable analysis of risk factors for discontinuation of baseline contraceptive method at 3 years

| Multivariable model | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| HR | 95% CI | ||

| Contraceptive method | |||

| OCPs | Reference | ||

| LNG-IUD | 0.31 | 0.27 | 0.36 |

| Cu-IUD | 0.33 | 0.27 | 0.40 |

| Implant | 0.44 | 0.37 | 0.52 |

| DMPA | 0.93 | 0.78 | 1.11 |

| Patch | 1.17 | 0.91 | 1.52 |

| Ring | 1.16 | 1.00 | 1.35 |

|

| |||

| Contraceptive duration | |||

| LARC | Reference | ||

| Non-LARC | 3.08 | 2.80 | 3.39 |

|

| |||

| Age | |||

| 14–19 | 1.33 | 1.16 | 1.53 |

| 20+ | Reference | ||

|

| |||

| Race | |||

| Black | 1.12 | 1.01 | 1.25 |

| White | Reference | ||

| Others | 1.26 | 1.07 | 1.50 |

|

| |||

| Education | |||

| ≤High School | Reference | ||

| Some College | 0.93 | 0.84 | 1.04 |

| College/Grad | 0.85 | 0.74 | 0.98 |

|

| |||

| Low Socioeconomic Status | |||

| No | Reference | ||

| Yes | 1.05 | 0.95 | 1.17 |

|

| |||

| Parity | |||

| 0 | 1.10 | 0.98 | 1.23 |

| 1+ | Reference | ||

|

| |||

| History of STI | |||

| No | Reference | ||

| Yes | 1.21 | 1.10 | 1.34 |

HR, hazard ratio

CI, confidence interval

OCP, oral contraceptive pill

LNG, levonorgestrel

IUD, intrauterine device

Cu, copper

DMPA, depot medroxyprogesterone acetate

Low socioeconomic status is defined as trouble paying for basic needs (food, housing, medical care, transportation) or

receiving government aid (food stamps, welfare)

STI, sexually transmitted infection

Participants discontinued their baseline methods for a variety of reasons (Table 5). Of LNG-IUD users that discontinued this method, approximately 19% did so due to bleeding changes, while 25% reported “I did not like how it made me feel.” The most common reasons for Cu-IUD users to stop their method was bleeding changes (35%) and cramping (17%). Forty-five percent of implant discontinuers reported bleeding changes, and 28% reported that they did not like how they felt. Among non-LARC methods, 33% of DMPA users that stopped this method reported general “side effects” as the most common reason for discontinuing. Forty-two percent of OCP users that discontinued reported logistical reasons, such as the pill being hard to remember to get or to take. Of patch discontinuers, 41% reported “side effects.” Twenty-seven percent of women discontinuing the ring reported “side effects,” and 24% reported logistical issues.

Table 5.

Reasons for discontinuation of baseline contraceptive method in Contraceptive CHOICE Project

| LARC | Non-LARC | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LNG-IUD | Cu-IUD | Implant | DMPA | OCP | Patch | Ring | ||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Bleeding changes | 136 | 19.1 | 75 | 35.2 | 133 | 45.5 | 58 | 25.6 | 49 | 12.3 | 4 | 4.8 | 39 | 10.4 |

| Pain | 82 | 11.5 | 37 | 17.4 | 8 | 2.7 | 4 | 1.8 | 3 | 0.8 | 2 | 2.4 | 9 | 2.4 |

| Did not like “side effects” | 181 | 25.4 | 20 | 9.4 | 81 | 27.7 | 76 | 33.5 | 62 | 15.6 | 34 | 41.0 | 100 | 26.7 |

| Desired pregnancy | 67 | 9.4 | 22 | 10.3 | 17 | 5.8 | 4 | 1.8 | 8 | 2.0 | 3 | 3.6 | 15 | 4.0 |

| Method failed | 9 | 1.3 | 3 | 1.4 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0.9 | 25 | 6.3 | 4 | 4.8 | 11 | 2.9 |

| Expulsion/came off /fell out | 96 | 13.5 | 26 | 12.2 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | 5 | 6.0 | 14 | 3.7 |

| Difficult to use | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 20 | 5.3 |

| Logistics* | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 22 | 9.7 | 169 | 42.5 | 14 | 16.9 | 89 | 23.7 |

| All others | 142 | 19.8 | 30 | 14.1 | 53 | 18.2 | 61 | 26.7 | 82 | 20.6 | 17 | 20.5 | 78 | 20.8 |

|

| ||||||||||||||

| TOTAL | 713 | 213 | 292 | 227 | 398 | 83 | 375 | |||||||

LARC, long-acting reversible contraception

LNG, levonorgestrel

IUD, intrauterine device

Cu, copper

DMPA, depo medroxyprogesterone acetate

OCP, oral contraceptive pill

Time, hard to get, remember

COMMENT

Continuation rates for LARC methods at 1, 2, and 3 years are significantly higher than non-LARC methods. After adjusting for confounding variables, choice of a shorter-acting method and younger age were associated with increased discontinuation [1,4,18,19]. Teens aged 14–19 in our cohort were more likely to discontinue than women of 20 years of age and older. However, of those adolescents who chose LARC methods, over half were still using their method at 3 years compared to one-fifth of adolescents who were using their non-LARC methods at 3 years. Even among women using short-acting methods, 3-year continuation was relatively high. Those using OCPs, DMPA, patch, and ring had continuation rates between 28 and 33%.

Relatively few prior studies have estimated continuation beyond 1 year among U.S. women who chose their contraceptive method rather than being randomized to a method. Furthermore, this analysis was conducted using the data from the CHOICE cohort with a high follow-up rate where only 19% of participants were lost to follow-up at 3 years. Our cohort had continuation rates consistent with other prospective trials. The 70% continuation of both LNG-and Cu-IUDs was consistent with those reported previously of 67–80% [9–12]. The 56% continuation of implants was higher than previously reported of 30–53% [12–15].

It is very plausible that women who are interested in long-term (> 2 years) protection from pregnancy are more likely to select IUDs and the implant, while women who are less certain about their need or desire for long-term contraception would select non-LARC methods. However, we still believe our estimates of 3-year continuation are important as for contraceptive counseling. High continuation rates reflect high satisfaction with LARC methods [5].

The major limitation of CHOICE is that it is a convenience sample within one geographic region. Participants were required to start or switch to a different contraceptive method at enrollment, which may also limit generalizability. An important consideration in this analysis is our assessment of 3-year continuation of the subdermal implant. This may be an inappropriate cut-off to measure continuation and satisfaction if women undergo implant removal due to the approaching “expiration” of the device at 3 years (the FDA-approved duration of use) [20]. Another limitation is that data on side effects, continuation, and expulsion were self-reported through phone follow-up instead of at clinic visits.

Regardless of age, sociodemographic markers, and education, women using LARC methods report high continuation rates at 3 years. OCPs and condoms continue to be the most commonly-used reversible contraceptive methods used by U.S. women [3]. It is time for a paradigm shift: LARC methods should be considered first-line contraceptives for women of all ages given that satisfaction, continuation, and effectiveness of LARC methods have been shown to be superior to non-LARC methods [1,4,5,21].

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier Survival Curve of contraceptive continuation by long acting reversible contraceptive (LARC) methods and non-LARC methods.

CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS.

Regardless of age, race, and socioeconomic status, women using LARC methods report high continuation at 3 years.

IUDs and the contraceptive implant should be considered first-line contraceptives for all women given their effectiveness and high continuation rates.

Acknowledgments

The Contraceptive CHOICE Project is funded an anonymous foundation. This publication also was supported by the Washington University Institute of Clinical and Translational Sciences grant UL1 TR000448 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences and award number K23HD070979 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development (NICHD). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES: Drs. Diedrich and Secura and Ms. Zhao report no conflict of interest. Dr. Peipert receives research funding/support from Bayer, Teva, and Merck, and serves on advisory boards for Teva Pharmaceuticals and MicroCHIPs. Dr. Madden serves on an advisory board for Bayer Healthcare Pharmaceuticals and a data safety monitoring board for phase 4 safety studies of Bayer contraceptive products.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Winner B, Peipert JF, Zhao Q, Buckel C, Madden T, Allsworth JE, et al. Effectiveness of long-acting reversible contraception. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1998–2007. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1110855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Finer LB, Jerman J, Kavanaugh ML. Changes in use of long-acting contraceptive methods in the United States, 2007–2009. Fertil Steril. 2012;98:893–7. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.06.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Branum A, Jones J. Trends in long-acting reversible contracepiton use among U.S. women aged 15–44. Natl Cent Heal Stat. 2015:188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O'neil-Callahan M, Peipert JF, Zhao Q, Madden T, Secura G. Twenty-four-month continuation of reversible contraception. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122:1083–91. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182a91f45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peipert JF, Zhao Q, Allsworth JE, Petrosky E, Madden T, Eisenberg D, et al. Continuation and satisfaction of reversible contraception. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117:1105–13. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31821188ad. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sivin I, Alvarez F, Diaz J, Diaz S, el Mahgoub S, Coutinho E, et al. Intrauterine contraception with copper and with levonorgestrel: a randomized study of the TCu 380Ag and levonorgestrel 20 mcg/day devices. Contraception. 1984;30:443–56. doi: 10.1016/0010-7824(84)90036-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Andersson K, Odlind V, Rybo G. Levonorgestrel-releasing and copper-releasing (Nova T) IUDs during five years of use: a randomized comparative trial. Contraception. 1994;49:56–72. doi: 10.1016/0010-7824(94)90109-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sivin I, el Mahgoub S, McCarthy T, Mishell DR, Shoupe D, Alvarez F, et al. Long-term contraception with the levonorgestrel 20 mcg/day (LNg 20) and the copper T 380Ag intrauterine devices: a five-year randomized study. Contraception. 1990;42:361–78. doi: 10.1016/0010-7824(90)90046-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.UNDP/UNFPA/WHO/World Bank IRG. A randomized multicentre trial of the Multiload 375 and TCu380A IUDs in parous women: three-year results. UNDP/UNFPA/WHO/World Bank, Special Programme of Research, Development and Research Training in Human Reproduction: IUD Research Group. Contraception. 1994;49:543–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Champion CB, Behlilovic B, Arosemena JM, Randic L, Cole LP, Wilkens LR. A three-year evaluation of TCu 380 Ag and multiload Cu 375 intrauterine devices. Contraception. 1988;38:631–9. doi: 10.1016/0010-7824(88)90046-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baldaszti E, Wimmer-Puchinger B, Löschke K. Acceptability of the long-term contraceptive levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (Mirena): a 3-year follow-up study. Contraception. 2003;67:87–91. doi: 10.1016/s0010-7824(02)00482-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weisberg E, Bateson D, McGeechan K, Mohapatra L. A three-year comparative study of continuation rates, bleeding patterns and satisfaction in Australian women using a subdermal contraceptive implant or progestogen releasing-intrauterine system. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2014;19:5–14. doi: 10.3109/13625187.2013.853034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lakha F, Glasier AF. Continuation rates of Implanon in the UK: data from an observational study in a clinical setting. Contraception. 2006;74:287–9. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2006.05.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rai K, Gupta S, Cotter S. Experience with Implanon® in a north-east London family planning clinic. Eur J Contracept Reprod Heal Care. 2004;9:39–46. doi: 10.1080/13625180410001696223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Agrawal A, Robinson C. An assessment of the first 3 years ’ use of Implanon ® in Luton. 2005;31:310–3. doi: 10.1783/147118905774480581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Secura GM, Allsworth JE, Madden T, Mullersman JL, Peipert JF. The Contraceptive CHOICE Project: reducing barriers to long-acting reversible contraception. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;203:115, e1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Madden T, Mullersman JL, Omvig KJ, Secura GM, Peipert JF. Structured contraceptive counseling provided by the Contraceptive CHOICE Project. Contraception. 2013;88:243–9. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2012.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rosenstock JR, Peipert JF, Madden T, Zhao Q, Secura GM. Continuation of reversible contraception in teenagers and young women. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120:1298–305. doi: 10.1097/aog.0b013e31827499bd. doi: http://10.1097/AOG.0b013e31827499bd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Secura GM, McNicholas C. Long-acting reversible contraceptive use among teens prevents unintended pregnancy: a look at the evidence. Expert Rev Obstet Gynecol. 2013;8:297–9. doi: 10.1586/17474108.2013.811942. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McNicholas C, Maddipati R, Zhao Q, Swor E, Peipert JF. Use of the etonogestrel implant and levonorgestrel intrauterine device beyond the u.s. Food and drug administration-approved duration. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:599–604. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Secura GM, Madden T, McNicholas C, Mullersman J, Buckel CM, Zhao Q, et al. Provision of no-cost, long-acting contraception and teenage pregnancy. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:1316–23. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1400506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]